RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

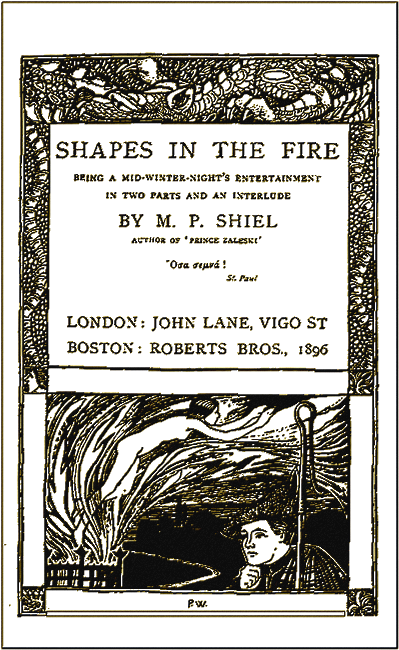

Shapes in the Fire, Cover of First Edition

Shapes in the Fire, Title Page of First Edition

To Mistress Beatrice Laws

Dear Beatrice,—The pieces of this inkling of a Book, which, with much longing, I dedicate to you, were not all written in the same night, but separated in their execution by intervals for eating and sleeping; and as you know me to be of at least not less nervous vigour than your sweet self (for in Thee is not vigour gobbled up in sweetness?), so you, too, red ruddes, should read them (in spite of the sub-title), with like intervals, one by one, not gulp them like porridge or a novel,—which, you know, are homogeneous, these being designedly heterogeneous—or you will hardly, I think, get at what one meant to imply (Easily, you know, in the crash of the orchestra, do the light flute-notes lose themselves on the tired ear: a fact which seems to indicate that works of art, especially such as pretend to be more or less musical should be not only pretty short, but separately imbibed; so that the Concert, for one thing, is wrong; and with it, the book, such as this, of short detached pieces, which is a literary Concert; only that here, you have it in your option to extend your concert into as many nights as there are pieces; and your concert-giver, too, hath it more in his dominion what piece shall company with what, and what shall be the precise complexity and information of the whole.) Well, but to maintain the dear fiction of the Winter's Night, I will say this (epistolary—and not as they write big in the volume of the Books, lest you pout): that the curtain having risen, I will present you first a diary-extract of a poor friend now dead; then a little morne drama which I have encountered in the chronicle of one Aventin von Tottenweis; and next a rather dark experience of my own in the dim Northern seas, which, in dream, yet revisits me. Then will be a short interlude for cigarettes, ices, and whispy-lispy, during which will be rendered a piece just splashed down anyway, for a male reader or two, and in some places dull (to you I mean) and in others pretty cheap,—this, however, being a day of cheap things, sweetmeat; you yourself, perhaps, not so over-dear, and only over-dear to the beglamoured eyes of male-made me. This, then, you should skip (recalcitrant roe that thou art on the Mountains of Endeavour!) Go out on the verandah, pig's-eye, and there heave, the open secret of that torse my soul remembers to the chaste down-look of Dian's astonished eye-glass, and the schwärmerei of the winking Stars. But soon, at about midnight, return; for now, to the tinkle of a silver bell, will unfold itself the life-history, very well translated by me from the original, of a poor man of Hindustan, not, I verily believe, unloved of the gods, but loved, you perceive, in their peculiar fashion: those people (as the late Mr. Froude uncommonly said to the dying Carlyle) probably having reasons for their carryings-on, of which we cannot even dream. And truly, dear, this is marvellous in our eyes, or at least in mine. Well, but now, just as that dark Daphne with the gems entangled in her hair turns paling in flight from the red rape of day, I shall (spiritualest wine coming last, you know, as at that Marriage) once more introduce myself in character this time of lover, and tell how I wooed one of the ladies of my heart at world-illustrious Phorfor. Immediately whereupon, Beloved, shall the Day break, and the Shadows flee away.—Yours, pour toujours et une Nuit d'Hiver!

The Author

"He goeth after her... and knoweth not..." (From a diary)

Three days ago! by heaven, it seems an age. But I am shaken—my reason is debauched. A while since, I fell into a momentary coma precisely resembling an attack of petit mal. "Tombs, and worms, and epitaphs"—that is my dream. At my age, with my physique, to walk staggery, like a man stricken! But all that will pass: I must collect myself—my reason is debauched. Three days ago! it seems an age! I sat on the floor before an old cista full of letters. I lighted upon a packet of Cosmo's. Why, I had forgotten them! they are turning sere! Truly, I can no more call myself a young man. I sat reading, listlessly, rapt back by memory. To muse is to be lost! of that evil habit I must wring the neck, or look to perish. Once more I threaded the mazy sphere-harmony of the minuet, reeled in the waltz, long pomps of candelabra, the noonday of the bacchanal, about me.

Cosmo was the very tsar and maharajah of the Sybarites! the Priap of the détraqués! In every unexpected alcove of the Roman Villa was a couch, raised high, with necessary foot-stool, flanked and canopied with mirrors of clarified gold. Consumption fastened upon him; reclining at last at table, he could, till warmed, scarce lift the wine! his eyes were like two fat glow-worms, coiled together! they seemed haloed with vaporous emanations of phosphorus! Desperate, one could see, was the secret struggle with the Devourer. But to the end the princely smile persisted calm; to the end—to the last day—he continued among that comic crew unchallenged choragus of all the rites, I will not say of Paphos, but of Chemos! and Baal-Peor! Warmed, he did not refuse the revel, the dance, the darkened chamber. It was utterly black, rayless; approached by a secret passage; in shape circular; the air hot, haunted always by odours of balms, bdellium, hints of dulcimer and flute; and radiated round with a hundred thick-strewn ottomans of Morocco.

Here Lucy Hill stabbed to the heart Caccofogo, mistaking the scar of his back for the scar of Soriac. In a bath of malachite the Princess Egla, waking late one morning, found Cosmo lying stiffly dead, the water covering him wholly.

"But in God's name, Mérimée!" (so he wrote), ''to think of Xélucha dead! Xélucha! Can a moon-beam, then, perish of suppurations? Can the rainbow be eaten by worms? Ha! ha! ha! laugh with me, my friend: 'elle dérangera l'Enfer'! She will introduce the pas de tarantule into Tophet! Xélucha, the feminine Xélucha recalling the splendid harlots of history! Weep with me—manat rara meas lacrima per genas! expert as Thargelia; cultured as Aspatia; purple as Semiramis. She comprehended the human tabernacle, my friend, its secret springs and tempers, more intimately than any savant of Salamanca who breathes. Tarare—but Xélucha is not dead!

Vitality is not mortal; you cannot wrap flame in a shroud. Xélucha! where then is she? Translated, perhaps—rapt to a constellation like the daughter of Leda. She journeyed to Hindostan, accompanied by the train and appurtenance of a Begum, threatening descent upon the Emperor of Tartary. I spoke of the desolation of the West; she kissed me, and promised return.

Mentioned you, too, Mérimée—'her Conqueror'—'Mérimée, Destroyer of Woman.' A breath from the conservatory rioted among the ambery whiffs of her forelocks, sending it singly a-wave over that thulite tint you know. Costumed cap-à-pie, she had, my friend, the dainty little completeness of a daisy mirrored bright in the eye of the browsing ox. A simile of Milton had for years, she said, inflamed the lust of her Eye: 'The barren plains of Sericana, where Chineses drive with sails and wind their cany wagons light.' I, and the Sabaeans, she assured me, wrongly considered Flame the whole of being; the other half of things being Aristotle's quintessential light. In the Ourania Hierarchia and the Faust-book you meet a completeness: burning Seraph, Cherûb full of eyes. Xélucha combined them. She would reconquer the Orient for Dionysius, and return. I heard of her blazing at Delhi; drawn in a chariot by lions. Then this rumour—probably false. Indeed, it comes from a source somewhat turgid. Like Odin, Arthur, and the rest, Xélucha—will reappear."

Soon subsequently, Cosmo lay down in his balneum of malechite, and slept, having drawn over him the water as a coverlet. I, in England, heard little of Xélucha: first that she was alive, then dead, then alighted at old Tadmor in the Wilderness, Palmyra now. Nor did I greatly care, Xélucha having long since turned to apples of Sodom in my mouth. Till I sat by the cista of letters and re-read Cosmo, she had for some years passed from my active memories.

The habit is now confirmed in me of spending the greater part of the day in sleep, while by night I wander far and wide through the city under the sedative influence of a tincture which has become necessary to my life. Such an existence of shadow is not without charm; nor, I think, could many minds be steadily subjected to its conditions without elevation, deepened awe. To travel alone with the Primordial cannot but be solemn. The moon is of the hue of the glow-worm; and Night of the sepulchre. Nux bore not less Thanatos than Hupuos, and the bitter tears of Isis redundulate to a flood. At three, if a cab rolls by, the sound has the augustncss of thunder. Once, at two, near a corner, I came upon a priest, seated, dead, leering, his legs bent. One arm, supported on a knee, pointed with rigid accusing forefinger obliquely upward. By exact observation, I found that he indicated Betelgeux, the star "a" which shoulders the wet sword of Orion. He was hideously swollen, having perished of dropsy. Thus in all Supremes is a grotesquerie; and one of the sons of Night is—Buffo.

In a London square deserted, I should imagine, even in the day, I was aware of the metallic, silvery-clinking approach of little shoes. It was three in a heavy morning of winter, a day after my rediscovery of Cosmo. I had stood by the railing, regarding the clouds sail as under the sea-legged pilotage of a moon wrapped in cloaks of inclemency. Turning, I saw a little lady, very gloriously dressed. She had walked straight to me. Her head was bare, and crisped with the amber stream which rolled lax to a globe, kneaded thick with jewels, at her nape. In the redundance of her décolleté development, she resembled Parvati, mound-hipped love-goddess of the luscious fancy of the Brahmin.

She addressed to me the question:

"What are you doing there, darling?"

Her loveliness stirred me, and Night is bon camarade. I replied:

"Sunning myself by means of the moon."

"All that is borrowed lustre," she returned, "you have got it from old

Drummond's Flowers of Sion."

Looking back, I cannot remember that this reply astonished me, though it should—of course— have done so. I said:

"On my soul, no; but you?"

"You might guess whence I come!"

"You are dazzling. You come from Paz."

"Oh, farther than that, my son! Say a subscription ball in Soho."

"Yes?... and alone? in the cold? on foot...?"

"Why, I am old, and a philosopher. I can pick you out riding Andromeda yonder from the ridden Ram. They are in error, M'sieur, who suppose an atmosphere on the broad side of the moon. I have reason to believe that on Mars dwells a race whose lids are transparent like glass; so that the eyes are visible during sleep; and every varying dream moves imaged forth to the beholder in tiny panorama on the limpid iris. You cannot imagine me a mere fille! To be escortcd is to admit yourself a woman, and that is improper in Nowhere. Young Eos drives an équipage à quatre, but Artemis 'walks' alone. Get out of my borrowed light in the name of Diogenes! I am going home."

"Near Piccadilly."

"But a cab?"

"No cabs for me, thank you. The distance is a mere nothing. Come."

We walked forward. My companion at once put an interval between us, quoting from the Spanish Curate that the open is an enemy to love. The Talmudists, she twice insisted, rightly held the hand the sacredest part of the person, and at that point also contact was for the moment interdict. Her walk was extremely rapid. I followed. Not a cat was anywhere visible. We reached at length the door of a mansion in St. James's. There was no light. It seemed tenantless, the windows all uncurtained, pasted across, some of them, with the words, To Let. My companion, however, flitted up the steps, and, beckoning, passed inward. I, following, slammed the door, and was in darkness. I heard her ascend, and presently a region of glimmer above revealed a stairway of marble, curving broadly up. On the floor where I stood was no carpet, nor furniture: the dust was very thick. I had begun to mount when, to my surprise, she stood by my side, returned; and whispered:

"To the very top, darling."

She soared nimbly up, anticipating me. Higher, I could no longer doubt that the house was empty but for us. All was a vacuum full of dust and echoes. But at the top, light streamed from a door, and I entered a good-sized oval saloon, at about the centre of the house. I was completely dazzled by the sudden resplendence of the apartment. In the midst was a spread table, square, opulent with gold plate, fruit dishes; three ponderous chandeliers of electric light above; and I noticed also (what was very bizarre) one little candlestick of common tin containing an old soiled curve of tallow, on the table. The impression of the whole chamber was one of gorgeousness not less than Assyrian. An ivory couch at the far end was made sun-like by a head- piece of chalcedony forming a sea for the sport of emerald ichthyotauri. Copper hangings, parnlled with mirrors in iasperated crystal, corresponded with a dome of flame and copper; yet this latter, I now remember, produced upon my glance an impression of actual grime. My companion reclined on a small Sigma couch, raised high to the table-level in the Semitic manner, visible to her saffron slippers of satin. She pointed me a seat opposite. The incongruity of its presence in the middle of this arrogance of pomp so tickled me, that no power could have kept me from a smile: it was a grimy chair, mean, all wood, nor was I long in discovering one leg somewhat shorter than its fellows.

She indicated wine in a black glass bottle, and a tumbler, but herself made no pretence of drinking or eating. She lay on hip and elbow, petite, resplendent, and looked gravely upward. I, however, drank.

"You are tired," I said, "one sees that."

"It is precious little than you see!" she returned, dreamy, hardly glancing.

"How! your mood is changed, then? You are morose."

"You never, I think, saw a Norse passage-grave?"

"And abrupt."

"Never?"

"A passage-grave? No."

"It is worth a journey! They are circular or oblong chambers of stone, covered by great earthmounds, with a 'passage' of slabs connecting them with the outer air. All round the chamber the dead sit with head resting upon the bent knees, and consult together in silence."

"Drink wine with me, and be less Tartarean."

''You certainly seem to be a fool,'' she replied with perfect sardonic iciness. "Is it not, then, highly romantic? They belong, you know, to the Neolithic age. As the teeth fall, one by one, from the lipless mouths—they are caught by the lap. When the lap thins—they roll to the floor of stone. Thereafter, every tooth that drops all round the chamber sharply breaks the silence."

"Ha! ha! ha!"

"Yes. It is like a century-slow, circularly-successive dripping of slime in some cavern of the far subterrene."

"Ha! ha! This wine seems heady! They express themselves in a dialect largely dental."

"The Ape, on the other hand, in a language wholly guttural."

A town-clock tolled four. Our talk was holed with silences, and heavy-paced. The wine's yeasty exhalation reached my brain. I saw her through mist, dilating large, uncertain, shrinking again to dainty compactness. But amorousness had died within me.

"Do you know," she asked, "what has been discovered in one of the Danish Kjökkenmöddings by a little boy? It was ghastly. The skeleton of a huge fish with human—"

"You are most unhappy."

"Be silent."

"You are full of care."

"I think you a great fool."

"You are racked with misery."

"You are a child. You have not even an instinct of the meaning of the word."

"How! Am I not a man? I, too, miserable, careful?"

"You are not, really, anything—until you can create."

"Create what?"

"Matter."

"That is foppish. Matter cannot he created, nor destroyed."

"Truly, then, you must be a creature of unusually weak intellect. I see that now. Matter does not exist, then, there is no such thing, really—it is an appearance, a spectrum—every writer not imbecile from Plato to Fichte has, voluntary or involuntary, proved that for good. To create it is to produce an impression of its reality upon the senses of others; to destroy it is to wipe a wet rag across a scribbled slate."

"Perhaps. I do not care. Since no one can do it"

"No one? You are mere embryo—"

"Who then?"

"Anyone, whose power of Will is equivalent to the gravitating force of a star of the First Magnitude."

"Ha! ha! ha! By heaven, you choose to be facetious. Are there then wills of such equivalence?"

"There have been three, the founders of religions. There was a fourth: a

cobbler of Herculaneum, whosc mere volition induced the cataclysm of Vesuvius

in '79' in direct opposition to the gravity of Sirius. There are more fames

than you have ever sung, you know. The greater number of disembodied spirits,

too, I feel certain—"

"By heaven, I cannot but think you full of sorrow! Poor wight! come, drink with me. The wine is thick and boon. Is it not Setian? It makes you sway and swell before me, I swear, like a purple cloud of evening—"

"But you are mere clayey ponderance!—I did not know that!—you are no companion! your little interest revolves round the lowest centres."

"Come—forget your agonies—"

"What, think you, is the portion of the buried body first sought by the worm?"

"The eyes! the eyes!"

"You are hideously wrong—you are so utterly at sea——"

"My God!"

She had bent forward with such rage of contradiction as to approach me closely. A loose gown of amber silk, wide-sleeved, had replaced her ball attire, though at what opportunity I could not guess; wondering, I noticed it as she now placed her palms far forth upon the table. A sudden wafture as of spice and orange-flowers, mingled with the abhorrent faint odour of mortality over-ready for the tomb, greeted my sense. A chill crept upon my flesh.

"You are so hopelessly at fault—"

"For God's sake—"

"You are so miserably deluded! Not the eyes at all!"

"Then, in heaven's name, what?"

Fivc tollcd from a clock.

"The Uvula! the soft drop of mucous flesh, you know, suspended from the palate above the glottis. They eat through the face-cloth and cheek, or crawl by the 1ips through a broken tooth, filling the mouth. They make straight for it. It is the deliciae of the vault."

At her horror of interest I grew sick, at her odour, and her words. Some unspeakable sense of insignificance, of debility, held me dumb.

"You say I am full of sorrows. You say I am racked with woe; that I gnash with anguish. Well, you are a mere child in intellect. You use words without realization of meaning like those minds in what Leibnitz calls 'symbolical consciousness.' But suppose it were so—"

"It is so."

"You know nothing."

"I see you twist and grind. Your eyes are very pale. I thought they were hazel. They are of the faint bluishness of phosphorus shimmerings seen in darkness."

"That proves nothing."

"But the 'white' of the sclerotic is dyed to yellow. And you look inward. Why do you look so palely inward, so woe-worn, upon your soul? Why can you speak of nothing but the sepulchre, and its rottenness? Your eyes seem to me wan with centuries of vigil, with mysteries and millenniums of pain."

"Pain! but you know so little of it! you are wind and words! of its philosophy and rationale nothing!"

"Who knows?"

"I will give you a hint. It is the sub-consciousness in conscious creatures of Eternity, and of eternal loss. The least prick of a pin not Paean and Aesculapius and the powers of heaven and hell can utterly heal. Of an everlasting loss of pristine wholeness the conscious body is sub-conscious, and 'pain' is its sigh at the tragedy. So with all pain—greater, the greater the loss. The hugest of losses is, of course, the loss of Time. If you lose that, any of it, you plunge at once into the transcendentalisms, the infinitudes, of Loss; if you lose all of it—"

"But you so wildly exaggerate! Ha! ha! You rant, I tell you, of commonplaces with the woe—"

"Hell is where a clear, untrammelled Spirit is sub-conscious of lost Time; where it boils and writhes with envy of the living world; hating it for ever, and all the sons of Life!"

"But curb yourself! Drink—I implore—I implore—for God's sake—but once—"

"To hasten to the snare—that is woe! to drive your ship upon the light/mouse rock—that is Marah! To wake, and feel it irrevocably true that you went after her—and the dead were there— and her guests were in the depths of hell—and you did not know it!— though you might have.

Look out upon the houses of the city this dawning day: not one, I tell you, but in it haunts some soul— walking up and down the old theatre of its little Day—goading imagination by a thousand childish tricks, vraisemblances— elaborately duping itself into the momentary fantasy that it still lives, that the chance of life is not for ever and for ever lost—yet riving all the time with under-memories of the wasted Summer, the lapsed brief light between the two eternal glooms—riving I say and shriek to you! —riving, Mérimée, you destroying fiend—She had sprung—tall now, she seemed to me—between couch and table.

"Mérimée!" I screamed, "—my name, harlot, in your maniac mouth! By God, woman, you terrify me to death!"

I too sprang, the hairs of my head catching stiff horror from my fancies.

"Your name? Can you imagine me ignorant of your name, or anything concerning you? Mérimée! Why, did you not sit yesterday and read of me in a letter of Cosmo's?"

"Ah-h... ," hysteria bursting high in sob and laughter from my arid lips—"Ah! ha! ha!

Xélucha! My memory grows palsied and grey, Xélucha! pity me—my walk is in the very valley of shadow!— senile and sere!—observe my hair, Xélucha, its grizzled growth—trepidant, Xélucha, clouded—I am not the man you knew, Xélucha, in the palaces—of Cosmo! You are Xélucha!"

"You rave, poor worm!" she cried, her face contorted by a species of malicious contempt.

"Xélucha died of cholera ten years ago at Antioch. I wiped the froth from her lips. Her nose underwent a green decay beforc burial. So far sunken into the brain was the left eye—"

"You are—you are Xélucha!" I shrieked; "voices now of thunder howl it within my consciousness—and by the holy God, Xélucha, though you blight me with the breath of the hell you are, I shall clasp you, living or damned—"

I rushed toward her. The word "Madman!" hissed as by the tongues of ten thousand serpents through the chamber, I heard; a belch of pestilent corruption puffed poisonous upon the putrid air; for a moment to my wildered eyes there seemed to rear itself, swelling high to the roof, a formless tower of ragged cloud, and before my projected arms had closed upon the very emptiness of insanity, I was tossed by the operation of some Behemoth potency far-circling backward to the utmost circumference of the oval, where, my head colliding, I fell, shocked, into insensibility.

When the sun was low toward night, I lay awake, and listlessly observed the grimy roof, and the sordid chair, and the candlestick of tin, and the bottle of which I had drunk. The table was small, filthy, of common deal, uncovered. All bore the appearance of having stood there for years. But for them, the room was void, the vision of luxury thinned to air. Sudden memory flashed upon me. I scrambled to my feet, and plunged and tottered, bawling, through the twilight into the street.

Dreadfully like an immortal goddess i' the face! —Homer

Albrecht Dürer—artium lumen, sol artificum-pictor-calcographus-sculptor-sine exemplo—one day sent, as we know, a black-and-white wash of his face, untouched by pencil, to his friend, a certain Raphaelo Santi at Rome: a piece of work said to have been much admired of the Master. Two years later, Dürer despatched just such another to the morganatic Gräfin von Hohenschwangau—a great lover of Art, herself an artist—and it was the burning of this portrait that was the undoing of the Lord of Schwangau himself and so of all that branch of the race of the Herzogs of Swabia, till now.

The history is in part archived in the Bertha room of the little yellow-stone Schloss which now occupies the heights of the Schwanstein—a spot strange 'picturesqueness,' wondered at within the last decade by some of those British pilgrims who have taken the Constance route to see at Oberammergau. One stops at drowsy Füssen on the torrent Lech, and mounting an Einspanner, penetrates five miles into the richly-forested mountains. The new castle, like the one which preceded it, occupies the loneliness of a sharply-defined ridge-summit, and looks down upon the grey old lazy race of swans which haunts the Schwansee below, and upon the vague blue dream of yet three lakes visible from the height; but the oldest castle of all was lower down, near the plain, on the borders almost of the See. The top of Schwanstein could not, in fact, have contained its massive spread. For gaunt background, the bare breasts of the cleft Säuling.

The incident is, moreover, sketched in a rare old folio of one Aventin von Tottenweis, called: Beiträge zur Kentniss der mittelalterlischen Malerschulen, mit verschiedenen damaligen Familien-Geschichten.

Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, having the lust to harry Turks south of Danube, had drawn in his wake many a thirsty sword of Southern Wehrfähige from Franconia to utmost Rheinpfalz; and even when only the fame of the Ungarn king still lived, Caspar of Schwangau, observing with disquiet a fleck of rust on his two-handed sword, and a white wire in his long beard, enticed after him a small body, Freiherren, barons, holding, some of them, in feof of his house, and set out on the well-worn route: by no means with injurious intent to any person, but merely in order that that might happen which our Lady of Zugspitze, in her gracious pleasure, might will to happen.

And now, scarce any rough work presenting, the band meeting only with cullions and caitiff curs, and so dispersing by mere centrifugal perversity and dissent,—what more simple than that Caspar, headlong man, should find himself alone with sword and jazeran at Stamboul; cross over into the Troad; thence by the Aegean to the legs of Piraeus; and in the neighbourhood of Colonus, near the very grove, sacrosanct, solemn, where the Semnai gave everlasting rest to way-weary Oedipus, there finally be meshed?

In precipitate fashion, he wooed, and partly won. She was of ancient priestly family, a genuine Hellen of antique descent, unmixed, chaste, and over-tall in the half-revealing draperies of the old daughters of the gods.

Over the Knie-pass, west of Wetterstein, a train of sumpter-mules, following behind them, laboured out of the Tyrol toward the flat table-land of Ober-Bayern, under a burden of precious things, a Hera by Praxiteles, immortal amphorae, MSS, paintings older than the Lyceum. This was the Countess's dot.

The grandeur of the alp must have been novel after sylvan Colonus, and even Caspar's eye was not callous: but Deianira saw here nothing but rudeness. Only, let once a lonely Sennhaus appear, the overhanging roof of thatch weighted with boulders, the variegated Sennerinn herself in thick-waisted shin-frock at the door, and instantly the Greek interest would flutter up at the hint of fitness, the making hand of man, and the artist reined to look with sidling head.

And so they came to the Schloss by the Schwansee; drawbridge and portcullis felt a throe, and through a double hedge of pikes and arquebuses they passed by the base-court to the great black round Keep, tower-flanked; and here in the gloom of the old Ritter-saal, before castle-chaplain, and God, and every saint, Caspar tendered the left hand of a true knight, and his whole passionate and subservient heart.

Said old Wilhelm of the Horneck, garrulous as a rattle, inveterate tri-ped, having shot out an oaken limb ever since the reign of Caspar's father: 'But, Gräfin, you must e'en know that these are not the days that have been. Hey for the fair, gallant times when Wilhelm was tall as the rest; and land and laws were supple to the will of the grand reckless old Adels; and a free imperial knight might e'en marry a scullion, and forthwith have her 'nobled without ado. But Wilhelm is old now, Gräfin, and things do flow to change. There was Lippe-Detwold wedded a wench from the market-place at Strassburg; and there was Heinrich von Anhalt-Dessau married a hind's pullet in Schwarzwald, as indeed nearly every Anhalt-Dessau has stooped to the unebenbürtig since the time of Conrad le Salique. Ennobled! the whole company of them, and nothing said. But now! by the Three Kings, the Empire melts, with your upstart free cities, and the rest. Why, can you credit it, dear lady, that the Elector Frederick himself, a Reichsunmittelbarer-Fürst, who married a ballad-singer from the Court at Munich when I was a lad, can't yet obtain a dispensation, and the children remain what you guess? And here now is our own Herr Graf gone to the diet at Ratisbon to talk with Maximilian, if something cannot be done for you; and there's Maximilian, stubborn as a Lombard mule, or a bürger of Augsburg—'

A luminous narrow lake of grape-purple, clear hyaline, showed gaudily beneath her half- opened lids.

'Is that, then, the reason of the Count's absence?'

'What! did he not tell you? I thought I heard him—'

'Possibly. It can be of no moment.'

'Of no moment! hear her! by the gebenedeite Jungfrau Maria of Eichstadt! and the children then are nothing—'

'What children?'

'The children that are coming, though late—that are e'en now coming, I think——' Her face was as when a drop of blackest dragon's blood falls and melts into a silver bowl of cream.

'Twittering sparrow that thou art, Wilhelm!'

'Ay, ay, Gräfin, Wilhelm's no eyas—an old fowl. I was burg-vogt of this castle half a score of years before our good lord was born: and right proud of it: and you think me an eyas, a stripling! people have me for an unfledged eyas! I who remember when, near seventy years ago, the grandfather of the wild Wolf of Rolandspitze broke loose over the land, stormed the old palace of the Emperor Arnulf at Regensburg, and carried off gold plate, pictures—'

'Yes? tell me....'

'Ah, you like to hear about pictures: too much, I think: and the Graf grows jealous—deadly jealous—of all your fine Kram and Putz, and the love you pay them! Say little, see much: that's my motto: I follow a point with my eye, as the needle said to the tailor. And let old Wilhelm, who has heard more marriage-bells mayhap, ay, and funeral-knells, than you, give you this hint—'

'But the Wolf! you mean the robber-baron of this region?'

'The same; he of the Felsenburg on the yon side of Lech; his grandfather sacked Regensburg Palace, seizing much treasure, all which his vile Lanzknechte trundled home—'

'Do you remember anything in particular?'

'Remember, ay; old Wilhelm's memory is as clear to-day.... The varlets took everything: the Blessed Sacrament chalices from the altar of the Doppel-kapelle, and, if you must know, there was one famous picture, spoken of at the time, called the Madonna in der Rosenlaube—'

A luted note escaped her. 'And has he it now, the Wolf?'

'They do say it was hung up in the shrine of his chapel of St. Gereon.'

'Wilhelm! it was a work of your own Meister Stephan, a disciple of Wilhelm von Cöln! Dürer has written me concerning him. But to recover it?'

'Recover—what? you judge ill of the fangs of Roland of Roland spitze, if you think—'

'Leave me now. Return later in your Nestor dress—the picture, you see, grows. And prepare me instantly a messenger for Ratisbon to call back the Count.'

The apartment, circular in shape, terminated a long series of darksome corridors from the central Ritter-saal. High up, two Gothic slits in the Cyclopean walls let in a parti-coloured gloom. Within, lychnoi and cressets perpetuated a dim Feast of Lanterns; making vague the majesty of a Zeus Herkeios in the centre; painted French watches; an Isis of Egypt; an open letter, and a drawing in red chalk, from Raphael, on a table of ebony arabesqued with walrus tusk; chryselephantine panels of Byzantium; a deep-blue mackaw from the South Seas, and two small golden serpents, deadly, black-freckled, of Hindostan, in a glazed Doric temple, love- offerings of Venice, the great merchantman, sent in adoration of the exotic beauty-queen of the Schwangau; enamelled pyxes of Limoges, pietas in wax, enoptra (mirrors), tapestries—a whole incrustation, dubious, sheeny, of all that fine Kram and Putz of which old Wilhelm had spoken.

That very night, while the messenger was still on the road to Ratisbon, Caspar broke through the hangings of the doorway, rosy with ardour.

'Ah, Herzchen, Herzchen—to see you again!'

By the deep low couch where she lay in a peplos of Genoa velvet he fell upon a knee, full of the consciousness of her sex, all-gone anew at the vaguely-lit contrast between the china whiteness of skin, and the thick convolving lips, fierce scarlet, of Rossetti's apocalypses. He bent to kiss her with a reverent, chivalric slowness, she motionless.

'And I have lorded it over the best Ortenburg, and Agalolfinger, and Hapsburg of them all— and you are to be Countess of Halsenheim!'

'Did you not meet my messenger?'

'Not I: is aught amiss?'

'Nothing; only I sent to you—'

'Tell me, tell me, Schätzchen—ah, the boy—when he comes'— laying close siege to her ear—'shall be Graf von Halsenheim, with a ninepearled coronet to his head!'

'The wolf of Roland-spitze, is he strong?'

'Strong, ay, with a pack of three hundred faitour jackals of Schwartz-reiters in his black hold. But why?'

'Does he not fear you?'

'Not he! not yet! though, by the bones of the Eleven Virgins, the wolf may yet know the meeting of the hound's teeth on his quarters—'

'But he loves gold?'

'Loves it, and takes it on the Duke's high-road. But why, Liebling, why—'

'Did you know that he has Stephan's Madonna in his chapel?'

He let slip from him like cold snow the naked thick arm which he had been kneading with caresses. He stood erect.

'Pictures again—and already!'

'Hence I sent for you,' she answered, with eyes opening slowly wide, 'it is, or should be, a great work: Albrecht Dürer writes me—'

'Tell me not of this Dürer — a low-born Bürger Schelm, drubbed, they say, by his own wife—'

'Base woman. No law of man could make such union good.'

'Pah! do you not know that the dauber is son to a goldsmith of Ungarn!'

'He is a son of the gods.'

'There is but one God, Deianira, and'—crossing with low head—'Jesu Christ whom He hath sent.'

Her eyes smiled and closed. 'This hunting after beauty, beauty,' he continued, calming, 'is not good, Liebling. Best make sure that God and his blessed saints look not upon it as sinful with holy eye askance. What then is this divine 'beauty' that you speak so of? By'r Lady, I see it in none of these gimcracks of yours! Give it up, Zuckerkorn! God's creatures for beauty, say I; look, if you want to see it, all lustrous, grand, in yonder mirror—'

'But I was not made by man for man's eyes.'

'You were made, I swear it, by God for my eyes.'

'And if you find me perfect, it is,—perhaps,—your eyes that are imperfect. The chance toppling of stones may form a hut, you know; but chance never built a temple to the Endless. The Greek women placed a statue of Hyacinthus in their sleeping-rooms, that their offspring might catch something of its wonder. Nature, you see, is nearly everywhere rude, crude, and waits for the rearranging touch of our hand. Glance only at that'—she pointed to the Zeus—no man of flesh ever looked so; you certainly never saw one such. Not by the imitation of nature was that shape born to life; but by four-winged imagination, yoked to the divine instinct of loveliness, and riding in paean triumph, scornful almost of nature. The Assyrians copied nature, and you know—'

'Nay, nay, I am no schoolman in these matters. You want, it seems, this Wolf of the Spitze hunted, and the smudge torn from his claws; well, by St. Hubert, hunted he shall be, and torn it shall be—by power of gold—or secret nightfall—or open storm——'

He had succumbed again to her side. She, inclining to him, bore a dead kiss to red pyre in his beard.

A page entered with a packet. An adventurer Italian, Count della Torre de Tasso (now great Thurn und Taxis) had lately set up a riding-post throughout the Empire. His courier had reached thus far from Nürnberg.

The packet flew open. First there was Brunehild, princess of the Visigoths, mortal bane of ten princes of the Merovingians, carved in hone-stone, and initialed 'A.D.'; the furrows of eighty years of crime; the blood-dabbled grey hairs tied to a horse's tail; the indignant hoofs spurning to broken death their guilty incubus; the triumph-smile of young Clothair near. Next, a letter in Latin, flourished at the end with a couplet from Ovid; and next, a curling folio of canvas, washed with a head. She held it open with her two extended arms.

'This then is he!'

Caspar had leant over to look. 'The burger-son of Nürnberg?'

'Dürer.'

'Well, he has a goodly, pleasant face enough. But methinks the fellow presumes, Herzchen. A bonfire of these child's toys, if you wish to pleasure me! And a letter interdicting—'

'Nay, the next letter,' she said, smiling an arch câlinerie, 'will be a boast that I have the Stephan Madonna of the Rose-bower—safe!'

The Dürer-head, stretched on a framing, took rank by the couch. The light of a fierce, fond criticism beat upon it, and Caspar, entering unawares, was witness how, sitting on the edge, she searched the pale azure eyes with intent forgetfulness, so that he touched her before she knew. And he frowned to see the swell of sudden pink which leapt to her throat.

And the next day when, fulminant with rage, he broke into the room, Dürer had vanished, and he noticed it: but his mind was of such sort as to bear the stress of only one disquiet at a time, and he said nothing of the daub. In his hand he flourished a document; a torrent of invective came from him.

'The blasphemous Frevler! His weasand for it, as I am true knight and Christian gentleman! See, Herzchen, see, this he has sent me—he—he— the meanest Mittel-frei, self-styled Graf and Wolf! His great-grandfather'—stamping to and fro—'digged the trench round his five-acre farm with his own hands. And this to me! His life for it—I will worry, worry, worry the poisonous rat from his stench-hole, by the Holy Mother of God! Self-styled Count! Slitting throats at noontide! claiming right to coin money in his own vile lair, like an Adeliger! taking of tolls! tribute from the villages! Walpurgis-tax— Michaelmas-tax— hearth-shilling— Frohn-arbeit— levied all upon other men's bauers— and his own grandfather a lubber-lipped Landsasse! Deems himself rechtsfähig, by—! Ha, Sir Count!'—with robust emphasis of foot—'thy weasand for it, then! I did but write, Herzchen, making stipulation for the stolen Madonna you wot of in return for honest Schwangau money rendered. He replies by a threat to harry me—harry me—'

Her eyes were wide. 'But you will obtain the Madonna?'

'Ah, that will I, and within the sennight!'

'By strategy and surprise, then—not by open assault.'

'How so?'

'For the sake of your own safety; and partly lest the man, having warning, destroy the work.' She made her arms a lulling charm, and slowly cooled his judgment to the temper of hers. Long after a windy night-fall, a picked body of cavaliers crept through the dripping woods of the heights above Füssen, taking their secret way to the Felsenburg.

The enterprise was as hardy as could be. Caspar only realised the steepness of the danger he had dared when he stood once more within his own good castle-gate. It was then breaking day. Helmeted still, visor down, glistening in wetted armour-plates, he winged his feet with the good news towards the bed-chamber of Deianira. As often, she had passed a sleepless night; her bed was unruffled. Thence with eager outlook he hurried to the apartment where the lychnoi, in a sleepy twilight inviolate as yet of the crude day, laved the empty couch of the Greek. An angry 'wetter!' broke from him. In a corridor he came upon Wilhelm of the Horneck, always a shaker before the cock, a heap of age, built upon his staff.

'How, now, Wilhelm? The Gräfin!'

'Not in her chamber, and not in her Kunst-kammer?'

'In neither, man, by my faith.'

The old fellow, sudden and quick in jealousy for his over-lord's dignity, looked bilious, suspecting truth.

'Follow me,' he said, 'old Wilhelm's eyes—old Wilhelm's wits—'twas always so—the dagger to cut every knot—from the time when your grandfather, Otto, took to too fluent rouses of Hochheimer grape—'

'Come, come, old man, less of lip and more of limb!'

Wilhelm led the way up the steep, unequal steps of a turret, along a dark passage, and pointed. Caspar stood before the open door of an extremely small room cut from the wall. Within, on a low table—almost an altar—of pierced bone, burned a right flank of three long vestas, stuck on pricket-candlesticks; a left flank of three; and, somewhat retired from them, a centre of three; and beyond them, hanging to the wall, a washed head; and before them, priestess of this shrine, the breast-banded back-view of Deianira, the gorgeous grace of her samite peplos, she erect, with perked head, searching, searching the pale azure eyes. She had not heard the clinking approach of Caspar's armour.

A harsh 'Ha!' broke from him.

She started into pink confusion, and then, instantly calm again, 'Ah, you have brought it then, the Madonna!'

The rattle of his metal broke an awful silence as he turned and marched to her apartment, she clinging expectant to his side. A not very large parcel, placed by a halberdier, lay in wrappings on the floor.

'Help, help me!' she cried, eagerness trembling in her fingers as she undid it; and then, 'but, oh! see there! fie! you have defaced it,' and now, after a moment's breathless inquisition, 'but— it is not—beautiful—not supremely; it lacks—not scrupulousness—certainly not that—but the— This is not Art, thought,—it is Nature, impulse! I am sorry I gave you the pains.'

Caspar stood tapping the frown of his resentment to ultimate smoothness beneath the tip of his steel boot, till she, remembering that he needed reconquest, set herself leisurely to the work. His bonderie lasted till mid-day, and then he was hers again.

Falconry, and the dear delights of woodcraft in the forest near, filled his mornings; and once, when the Madonna had been relegated to forgotten obscurity, she rose to meet him as he entered the door of the art-room, plumed, horn by horn, holding still the spear and straight short sticker, faintly streaked with dry blood of the boar.

'Tell me, have you had good venery this morning?'

She lavished on him the whole Aegean incantation of her loveliness, languishment of kisses, listening with quite disproportionate interest to details of the chase, the halloo, conduct of pack and prickers, the bringing to bay, the dimensions of the quarry. Then suddenly:

'Tell me, where is—Arras?'

'Arras? In Frankland, surely. But what now?'

'They make tapestry there?'

'Ay.'

'And you have heard of Raphael? You must, I think,—in Welschland?'

'Well, well, Herzchen.'

'Raphael, you know, highest of all—he has lately executed, so Pietro Perugino writes me, ten great works, altogether immortal, on cartone, at the invitation of your Pope, and these have been sent to Arras and the factory there to be woven into fabric. You see now the full connection? You see? And I hear that now their purpose is served, little account is made of them, and they lie dust-grown, neglected; to be purchased, therefore—think of it!—perhaps for little, by a wily bargainer, crafty to hide his eagerness of acquisition. Ah, and you will go! You will go!'

'Now, by St.—'

The name of the saint fainted on his lips, as a wind at the caress of a pearl-shelled grotto of roses, and down a steep incline, topped by angry impatience, and based by growling complaisance, slid Caspar; so that after not many days, accompanied by a very few pikes, he rode his moody way over the plain of the Schwangau. The sentinels on the turrets saw the little band swallowed by a glade of the forest, as they wound slowly forward on their long journey to Frankreich.

It was shortly after this that Albrecht Dürer—most dreamy-wandering of bürger-sons—his whole life a pious Wanderjahr—arrived.

Passing near on foot, he hoped for the minute-measured privilege of some talk with the exalted lady who had been pleased to approve him. Old Wilhelm of the Horneck himself, with no overflow of courtesy—eyeing yellowly, with rheumy eye, the dusty hose, and belted wamms, and short cloak, all of rather worn brown stuff—led him from the base-court, up to the Saal, and so along the corridors. A satchel, hanging diagonally, contained butter-brod, and two pieces of chalk. Deianira, just emerging from the hangings of her sanctuary, saw, and knew; and uttered a bated cry.

Dürer, too, knew, and his heart, failing, sank; regretting his rashness. More blushes than a girl's covered him. A sudden noon-day sun could not have dazzled and winded him more.

Some little time before this, while on his Italian trip he had written to a friend: 'In Italy I am a gentleman; in Germany a parasite.' Add to this that the genius was, by nature, shyer than a kid.

She greeted and led him to the chamber with a heart-simple old majesty, beyond anything he saw in the high dames who sailed athwart his eyesight in his humble Hofmaler attendance at the court of Maximilian and (afterwards) of Charles. Climaxes of crimson rushed every moment across his face. She sitting over against him. Andromache in his eyes, Helen, Artemis' self; and she said unexpectedly this:

'Well! you have come in lucky time: within—shall I say three weeks?—Raphael's Sistine cartoons will be here! Ten of them—a banquet of wine. And I know you will not think of going without seeing them!'

He could evoke nothing but a murmur of thanks.

Airy German magi, Novalises, idealists, will not hear of Time; for if the condamné actually finds a night eternity, and the Monk Felix one hundred years a second—whose shot brings down the volatile truth? Both, or rather neither, they say; for the thing computed is in each case reflexive of the computer merely, externally inane. Albrecht and Deianira, with their quick brains, might well have realised some such thought, had they compared the pace of these weeks of waiting with others past and to come. But crowded speculations of a different sort were insistent upon their attention.

At first, it was all decked words, picked turns of phrase, some of the open bashfulness remaining on the one side, the secret diffidence on the other; a continuous torrent of mere opinions; the world-old dogmatism of the artist, self-sure, but with claws now tucked-in;

Deianira's theories quite different from his, yet seeming almost to coincide, by means of trimmed, only half-expressed convictions, on this hand and that.

Everything was gazed into; Stephan produced. 'What curious work! so minute; but—' and she stopped.

'He is my favourite of the Cöln school,' said Durer; 'his limpid piety seems so to illumine all he did. Wynrich I place on a much lower grade: you never saw his Sancta Veronica in the Munich Pinacothek? No? Rather an inanity. And yet the old Cöln tempera was so excellent that he ought—'

'You place a very high value on medium, do you not?'

'Well, as a workman, a fairly high value, perhaps. You, I daresay, do not——'

'Not so high, maybe.'

'But this of Stephen is fine—ah, delicate, virgin. He painted the Dombild, too, in the Cathedral, but that, you would see, is much immaturer; here he is at his perfectest—the chastity of detail—of the crown, of the cherubs in the medallion—but you, doubtless, do not—'

'The Greek writers, painters, sculptors'—evading direct reply—'placed, I think, little value in details by themselves, except in so far as they conduced to the intended effect of the whole as a whole.'

This was a point of view new to Dürer. He blushed. And timidly: 'You think they were right?'

'They may have been wrong,' she said, and smiled.

Thus to begin. But the rapid days brought rapid realisation of the equality of all infinite things, and so a full resumption of self-reverence, and so greater freedom of thought and speech; the words falling out now less knit, foreknown—and more, ever more, of them, torrents laughing with light and feeling. No more careful retraction of claws, but roughish play, the free fraternity of two natural, high-strung people, conscious of themselves and of each other. Dürer had been everywhere, looking at things through the crystal simplicity of a devout, open intellect; lowliest pilgrim to Venice, to the Flemish cities: a lynx in the castle of Barbarossa at Gelnhausen, and among the ruins of the great old Charlemagne palaces at Aachen and Engelheim. The quattrocentisti had hewn their work, and ended; and out of that strength was coming, had come, sweetness as of ambrosia; Botticelli, the Holbeins, Buonarroti, all breathed the same new air; the Van Eycks had been painting in their wonderful new oil-varnish medium at Binges. All this movement, art-life, the delicate young monk-mind had felt, cutting clean the rein of aspiration, dreaming dreams, high but pure. Raphael had sent him two life-studies in chalk. He poured into the ear of Deianira fairy tales of art-history, gleams, hints, half cabalistic in their effect; secret treasures stored in monasteries grey as the dawn of German things; suspected gems in the vaults of the church of the Augustines at Nürnberg, and in the cloisters of St. Catherine at Augsburg; old Abbots—Alfred and Arinam of Bayern; Gosbert and Absolom of Triers—mixing in their tempera occult substances, dying with their selfish arcana; the splendid art of the Hohenstaufens; the rich gold-ground honey-medium work of the thirteenth century; the perfect impasto of John van Eyck; protégés of the old Emperors at Prague; the Maastricht school; subtle distinctions between Rhine-men and Westphalia-men, Dutch and Flemish; Israel von Meckenen; and the beauties of Wurmsur and Veit Stoss, and the only three-quarter beauties of Martin Schoen; a whole snow-flake cataclysm of wanton words.

'Do you know,' he asked, 'what di Cosimo mixed in his colours for the Death of Procris? Only guess!'

'And what does it matter what he mixed?' she answered, freely pouting now, a long-legged Aphrodite playing angry at baby-tricks of little Eros.

They parted lingeringly late in the night, and lay dreamlessly dreaming of the next day's bacchanal of reason, the word-orgy, and dancing rivulet of fancies.

For him she threw off something of the anchorite quiescence, and there were days when they took long walks together over the plain, and so into the shade of the forest; Albrecht's temper, naked to all influences of nature, softening at the great old trees, and deep glens, and dank, religious gloom; she maintaining the Greek coldness, feeling nothing. And long-drawn floats on the lake filled the halt twilight. A steep flight of stone steps at the back of the castle, mossy underfoot, over-arched every-way with a wide wilderness of bindweeds, led at this point down the hillside, and so plumped into the See. By this way they reached the high-prowed little shallop, itself a swan, moored to the platform.

Albrecht sometimes flung from a zither an old psalm-air or dainty-tripping Minne-lied to the drugged breezes and wavelets of the See. Not yet had Jacob Stainer gone through the forest with little tapping steel-hammer, and found that ever the oldest tree had in it the mellowest Memnon- music: Mittenwald and the violins were therefore future; but every peasant of Bavaria, even then, was a maker and twanger of the zithers whose universal twitter filled the land with sounds.

'Look!' cried Deianira, 'see—see how the presence of a man's hand reforms the callous landscape!

It was the 23rd of June. Here and there, on the heights round Schwangau, cones of flame, smoke-plumed, burned upward to the deepening sky.

'Sonnenwandfeuer,' said Albrecht, 'lit by the bauers. It is the Eve of St. John.' 'St. John!—why, it is the celebration of a solar myth—this, you know, is the summer solstice—the myth which underlies the story of Oedipus.'

'Hardly, I think. We light the fires because St. John—'

'And yet—they lack—arrangement. A supreme artist might so place them in reference to each other as actually to lift the scene into ideality. Chance does nothing.'

This banne camaraderie fructified into intimacy. Albrecht put a modest hand into the wallet of his brown cloak, and drew out the MS. of his little book, not yet completed, De Symmetriâ Partium; she envisaging him, sitting on the couch-edge, elbows meeting draped knees, chin joisted on fisted hands. And he read—Monk-Latin, with acolyte intonation—and she, with sure scalpel of inward criticism, listened, searching, searching his face. Now, the figures of Dürer in the 'Trinity with Heavenly Host' and the 'Christian Martyrs,' painted by himself, as well as his still surviving two heads, are beautiful indeed, but probably not true of his face, for his gift was never the presentation of a superlative degree of human 'prettiness.' The painter had, in fact, the spiritual face of a stripling seraph; such a face, that, had he been Italian, had his life passed in Florence and not Nürnberg, he must have been Raphael and not Dürer. A crinkled head of long, gossamer, auburn hair was the pensive playmate of every breath; and blushing maidenhood, and the innocent eyes of old recluses, and the kiss-compelling lips of Byron, transfigured him to the meek beauty of Leonardo da Vinci's John at the Last Supper.

And in fond repayment of the Symmetriâ Partium, Deianira produced from an alcove her own work of the last three years: a triptych with the rape of Persephone; old Wilhelm as Nestor; and, large on chestnut panel, a return of a sennerinn on Rosenkranz Sunday from Almen-leben on the heights; the bell-cow decked with edelweiss and rhododendron; the crowned sennerinn on its back; the train of meek kine, calved; the gratulatory length of village-street full of the laughter poured from every gossiping doorway; the bashful lover, broad-faced, in felt steeple-hat, presenting to Gretel the necessary nosegay—reward of all her lonesome ward of love. And she had only seen it once, crossing the Alp to Schwangau, years before. Albrecht, without a word, self-abased, looked at it, she smiling at his blank face. What spurred his wonderment was the lifefulness—he well knew the scene—and then, far above all, the unlikeness to any life anywhere. Never Bavarian peasant, or peasant or man in the world, owned such meaning traits, look so strange and high. Here, then was contact with a new school, perpetuated by one disciple, grandest of all, the school of Apelles, and old Rhodian masters of the Doric Hexapolis. It was shortly after this revelation that Dürer wrote to his friend Melanchthon that sentence so full of pathetic meekness: 'admirator sum minime meorum, ut olim; et saepe gemo meas tabulas intuens, et de infirmitate meâ cogitans.'

And now change was manifest in the spirit of their intercourse; a third distinct phase, like the evolved presentments of a planet's face—so natural, self-unconscious. The penumbra of a profound melancholy fell upon these souls—penumbra, because though poignant, it was not painful, but, on the contrary, full of luxury. Without shadow of apparent cause, they walked continually on the borders of the misty-dripping lake of tears, by the twilight banks of a spectral river of sighs. The art-talk dropped utterly; and, in its place, talk of life; and especially of death; and all mournful things. Albrecht had secretly wondered whither had vanished the present of his washed head: but exploring alone one day, he saw the square of deeper darkness on the wall of the little cell; entered, knew, looked at the nine extinguished tapers on the low altar-table; and frowned down a tingling tumult of ecstasy and pang which rushed through all his frame. Soon subsequent to this the doleful mood grew on.

'Pirene,' said Deianira, 'wept and wept, so bitterly wept, that she melted into a fountain.'

'And Kriemhild,' said Albrecht, 'when she heard of the death of Siegfried, so bitterly laughed, that the ringing rafters made the house to tremble.'

Here was intensity for intensity; deep calling to deep. Deianira had been no dyspeptic worm in painted Hoch-deutsche MSS., new-printed books. They droned of old German women; Thusnelda, the magnificent; Rumetrude, misty-weird; Carolus and his paladins in the romaunts; tragic bignesses of Niebelungen-lied; the true heart of Bertha; lily-chastity of Theodelinda; all the ah and pain of woe-worn Tannhäuser of the Hörselloch. They fell into comparisons between Ajax and Amadis; asked which was the pitifulest, Hercules Furens or Orlando, not yet 'Furioso.'

'Read to me,' he said. 'What?'

'Something sad.'

She filled the night with a reading-from-the-scroll of the long lamentation and wringing of hands of Euripides' Trojan Women.

At home with Plato and Aristotle, less familiar with the Tragedies, he caught perhaps not half; but the half filmed his eyes with a constant moisture. As the slow, variegated words, each a perfect round messenger from her, wafted clean and light like bubbles from a pipe, floated about him—rhythmic chorus, and pomp of sententious rhesis—he then first realised the Greek language, and all the fresh joy and wonder it is. And as all modes of beauty are akin—beauty of form to beauty of sound to beauty of odour—these need but approximation under right conditions to blend into harmonies, and so produce the ultimate delight. Albrecht, listening, drank an exhalation from her of mingled frangipane and ambergris, and roamed from the Paphian face of sea-foam white, to the braided bosom, to the fine linen zonè, to the broken billow of draperies at her feet, to the dainty arrangement of sandal-straps; and again back to the dead-white face. A rare exaltation—verging on tears—like the rarest flame of interstellar ethers— ached through his physic man.

The invitation had been that he should stay to see the Raphael cartoons. Looking now, each saw in the other's eyes that this must not be.

He slung his satchel, containing the chalk-sticks and the butter-brod crusted now to stone, upon his back.

The setting sun was the very genius of gold on the waters of the Schwansee. Languid undulations curved into purple and saffron and crimson before the breasts of the swans, and the beaked prore of the shallop. From the terraced garden which sloped to the edge of the See on the castle side, an oppression of violet-beds and roses pervaded the whole spirit of nature. Yet not a breath ran upon the water. All was a conflagration; the bordering tree-tops burned unconsumed; yellow streaks stretched quite up to the zenith; the sun and his immediate train stepped down incarnadine to couchée and purple bed, pomped and appanaged like dormiturient old queens of Assyria, drunk with blood and wine.

Their most commonplace words were uttered in a tone of profoundest sadness.

'Helen,' said Dürer, splashing one of the birds, 'had for father—a swan. Her mother Eurotian Leda. I seem to see a perfect fitness in the myth.'

'The poets,' she answered, looking never at him, 'would have pawned their hope of Elysium for power to give a higher impression of her beauty; and as of her beauty, so of the pain, the tragedy of her.'

'The pain, the tragedy! So it is, then, and must be, with beauty! Calvary is witness.'

'Cursed be it, I say; and the hunger of it!'

She hid from him the sudden passion of her face.

The sun set; the mist and melancholy of a morne twilight grew deepening down upon the lake. A flight of crows, the sad fate of a nightingale in a grove near, the flap of a swan, were evidence of the silence. They heard distinctly a change of sentries at the turret-portal next the see.

'You return to Nürnberg?'

'Not yet. I am a wanderer, you know, a confirmed wanderer.'

'Rest is best.'

'For myself I look for one rest henceforth—the rest that remaineth to the people of God.'

'I meant what you mean.'

'A roam among the alp-heights, perhaps—some sketching—'

'You will be still near me then.'

'Near you? Ah yes! still near you.'

The mournful mood of Gethsemane was in them; the old torrent of words ran low. Moving red lights gleamed through the barred window-slits of the donjon. It was night. A faint breeze arose, and wooed to truancy hairs of Deianira's filleted, uncovered head, and was heavy at a perfume it met around her, and died at the sweet tumult it won from the old gilt Aeolian phorminx, seven-stringed, which lay since the previous night in the shallop. She took it, and the insistence of the plectrum won from her a softly-sung hymn of Andromache.

Hector, the harmer

Moan'd at the night of thee; Myrmidon armour

Paled at the light of thee.

(Your lutes of lotus wood

Libyan wail for him!

Your lutes with wax conglued

Sweetness exhale for him!)

Ploughman of blessings!

Whelp-son his lingering,

Tears his expressings,

Harps knew his fingering!

Zeu! who through Ancient Night

Urgest thy travelling,

Yet metest ever right

Doom of thy ravelling;

Red has the flame of noon,

Rushed to obscurity— Rash let the crapèd moon

Rend up her durity!

'Ah! that was a chillier wind.'

The moon, which had uttered a scared face, drew quickly the grey curtains of the night and disappeared.

'It grows cold for you; you must go now within the Schloss.'

'It is lonely there.'

'Is it lonely?'

'And I am not cold. Touch my hand.' At his touch she shivered. A single drizzle-spray fell upon each of them.

'Still I must go,' he said.

A sob!

'We may meet again.'

'You will never come again.'

'Time and tide happeneth to us all, you know.'

'But—you will never come again.'

They had reached the platform of the bowered stair. He stepped from the shallop and stood with her. The mizzle had become clearly sensible. The moon had utterly vanished.

Her hand was in his. He stooped and kissed it—on back, in palm—ready to be mad as she. Luckily, her face was quite turned from him.

'God—' he said.

From her working lips came no sound. Her bosom rowed like two oarsmen struggling for life from the suck of the whirlpool.

He was gone. She stood and watched him to the other side of the lake, and the embankment there. He made fast the boat. A curtain of masonry ran here parallel to the See to defend the castle-back. Before he reached it the mist had swallowed him. As he finally disappeared from her, she buried her face in the voluming folds of her left arm, and the thin, low wail of a little child welled from her. Slowly she ascended the stairs.

The end would have been different, had Dürer, like Deianira, been all artist; but the Nürnberg painter was first of all saint, and artist after.

But there was evil news at the Schloss of Schwangau in those very days. The old nose of Wilhelm perked high, sniffing danger on the wind. Bauers and yeomen from round Füssen and Eschach, leaving their farms, came crying to the Burg-vogt for protection. Sathan himself was loose. At Hopfen a whole street had burned, the church of St. Magnus been pillaged. Two villages flamed together. Roland of Rolandspitze, biding his time, collecting his forces, had not forgotten his Madonna.

He was a species of Swabian Eppelein von Gailingen, a Sud-deutscher Wild Boar of Ardennes.

On the third day Caspar arrived—almost by stealth—with his little band of men-at-arms. He had heard tidings of trouble on the way. His blood was up.

Flushed with enthusiasms, high passions, he came to where the wool stood bundled before heron the distaff. 'Ah... ah... ah!' was all he could say, as he did, and did again, perfervid violence to her lips; she enduring with pensive patience. 'But you look not so well, täubchen— not so well—a look of care—to be expected now, perhaps—and I have brought the smudges— aha! that pleases it then? Ah... ah... sugary ecstasy that thou art!—three of them—yes, only three—the other seven lay buried in some hole—the factory is a monstrous place, you must know—and they showed me there scant courtesy, by'r Lady; but three, by much entreaty, and a threat or two thrown in, I did get—these being easily unearthed—for a few gulden. Ha! and here they come.'

Two waiting-men bore-in a long narrow box, opened; the cartoons had been cut into strips. Deianira rose, and adjusted them on the floor: Stephen stoned; Paul in prison at Philippi; the light at noon-day 'above the brightness of the sun.' For a minute, over each, the impeccable energy of her scrutiny worked intensely; then, without fail, she knew the truth of form, composition, drapery, effect. Coming to him, she rewarded him with a cold kiss. And coldly she said:

'Thank you—they are very lovely.'

Even he could see it, and went away wondering at her inertness, the death of her enthusiasm. But action, action was the word—no dallying over daubs! 'Come, man, news, news!' he cried to Wilhelm, towing the three-goer into a small room. Wilhelm, who was directness itself where the talk touched upon the old trade of war, was minute on the defences of the castle, ammunition, provisions, his own share in everything, the ravages of the Wolf. Only a few hours before a Wappen-herald had arrived at the gate, demanding the return of the Maria, loud with threats of siege.

'His strength, man?'

'Over three hundred, they say.'

'And ours?'

'A hundred and twenty, beside a flock of bauers.'

'And gold in our coffers?'

'Scarcity of that till harvest.'

'Ha! and where is now my cousin of Swabia?'

'At Augsburg they say.'

'Good! a despatch to him instantly, requisitioning succours, and the same to every friendly burggraf of the region. The ripped bowels of this Verräther, Wilhelm! And other news?'

'Nothing—only—' the old man halted, half loving his suzerain's quiet mind, and half the solace of the oily tongue.

'Well, Wilhelm, well—'

'Nothing—a visitor to the castle—the painter of Nürn—'

'Now, by—'

'For more than two weeks—'

'Ha!'

'Two weeks,' the conciseness melting before a fervour of doddering communicativeness, 'and never by my goodwill, either—'tis not till now that Wilhelm of Horneck has waited to see the back of a noble house broken by some strolling troubadour or runaway bauer's pup with fair face. You may have heard of Trautmandorfs wife and the mummer nigh a century gone. And did ye ever know old Wilhelm to predict you false? With right jealous eye, I tell you, I looked upon the long intimacies of speech—and wantonness of glides on the lake—by night—with worrying of—harps and zithers—'

'Enough, Herr of Horneck, enough—' Caspar had drawn back a foot, and was frowning into the old man's soul.

'Worrying of harps—and confluence of bent heads over Kram and Putz—and now that he is gone, the rekindling of the tapers before the painter-head—put your trust in old Wilhelm's eyes for seeing!—nine of them—burning continually, like the fires which they used to say the prince- bishop of Bruchsal plenished near the tombs of the Emperors in the crypts of Spires Cathedral— and the door of the cell kept locked, and a daily double-visit paid to the head—'

'Enough, man, I say—'

'But, for that matter, 'tis a left-handed wedlock—you are not bound. Well I remember the case—'

'Traitor! Silence!' His roar was the lion's; the old man cowered, silent; Caspar walked away. It was then late in the day. That very night a fresh troop of bauers fled into the castle, with tidings of added woes. At dawn the plain before Hohenschwangau was dotted grey, well beyond artillery range, with the leaguering tents of Roland.

And there was brisk work before long. The Burgh-wache, though insufficient to make even the proper show of strength, had no lack of fire, through hope of speedy help, and confidence in Caspar's generalship. He was in every place, a strong, ubiquitous spirit of disposition, inspiration. Two parallel bastioned curtains defended the front and sides of the donjon; before each of these a fosse and drawbridge; and before the outermost drawbridge an out-work barbican. Upon this last the chief besieging party, under Roland himself and his brother Fritz, concentred their efforts with scaling-ladders, petards and grenadoes, potent enginery; and upon this detachment Caspar in person, from a bastion of the first curtain, directed a saker and culverin hail-rain. But before nightfall the out-work had fallen to the reverberating hochs!' of the brigands.

Early the next day the storm reopened. The enemy, with manifold advance and retreat, now attempted the bastions of the first escarpment. Still no sign of Swabian support. A sigh for sleep, only for sleep, arose among Caspar's men. During the night a strain in the relief of sentinels had made itself felt, so meagre the garrison. Caspar himself had mounted guard.

In the afternoon, passing by Deianira's room, tired, he entered, pining for her. Hardly since his coming back had he seen her. Freely now, from his heart, he forgave her the entertainment of the bürger-son, knowing well her child's love for pictures and suchlike. Here in these recesses the volleying of howitzer and mortar, saker and falconet, whizz of arrows, smiting of pikes, was only buzzingly audible. She lay on the couch at full length, beautifully asleep, or only on the borderland of wakefulness. In this dim state, hearing the ghost of his footstep, she stretched out her arms, both of them, at full length before her, inviting to the luxury of her embrace; and he, smiling ineffably, trusting, gentle, came to her, bending himself down, happy at the sweet, voluntary friendship of her arms about his neck. She, in her half-sleep, murmured:

'Albrecht, Albrecht, thou art come...'

Caspar stumbled backward with that pale, distorted rigidity of face seen in the agonised brave fellows on the bastions when a sudden arrow entered their hearts. He reeled like a dying man from the chamber.

Deianira, vaguely conscious of disturbance, slowly opened her eyes, and was alone.

But in little time Wilhelm of Horneck came dashing into the room, youth in every third projected leg, and before her fell prone to his old knees, with outstretched clasped hands, a world of prayer in his eyes.

'O Gräfin—save the Count—you only can—for the love of God! Gräfin! There may be yet time—he thinks to make a sally—stark mad, raving! And the men, seeing certain death, refuse to follow him. Some devil, some furious devil, rides him. Save him! Only some fifty against three hundred! Gräfin! his eyes are two rolling suns of flame; and help must come to-night—tomorrow—for very certain, if he would only wait—'

She, surprised, rose. Outside they met men rushing hither and thither with wild looks. One said:

'They are gone—just passed the inner Fallbrücke. God help them!'

The desire to see overcame her, and, mounting the steps of a turret, she took a seat on a planchette within the boldly-projecting machicolation near the battlements, looking through an aperture. Here she was alone, the donjon being as yet safe from shot. The small band— multifariously armed, hellebardiers, brigandined archers, carabiniers, Caspar at their head—were then issuing from the outer bridge. Just now there had come a lull to the storm; the enemy were in lager. The sun was low, hidden behind a crag of Säuling. The castle party moved down a gentle slope.

A flourish of trumpets, a shout, arose—two— triumphant on one side, death-challenging on the other. Quickly before the lager-tents sprang a crop of dragon's teeth; midway they met.

Deianira's eyes rested only upon Caspar. A certain unusual tingling feeling, vaguely working, was struggling into form within her—akin to admiration. To the minute when the fight began her face was calm. Then she saw him in the thick of things, firm, Actè-bluff when thunder-bolts are abroad, and breakers break upon its rock. The first dawn of a smile rose orient upon her lips. A small body of men—the very pick of the castle—surrounded now every-way by the enemy— formed his immediate entourage; the rest, blocked, sustained the shock of the brigands. Every minute a life ended—two to one on the side of the besiegers, who did double-battle with the dogged despair of Caspar's men. He, it was clear, was bent upon some object away from him; his sword the very tooth of pestilence in his hand, his helmet-plume floating above all heads, certain token of coming death. The dawn spread to Deianira's eyes; an eager lustre grew gradually radiant in them. And soon the end of Caspar's quest was evident—the Wolf himself, distinguished by his raucous shouts of cheer, huge battle-axe, suit of fluted armour. The brool of Caspar's roar rang challenging out; they were near now. Roland, a towering bulk, nothing loth, rabid with the taste of blood, struck spur to charger; casting axe, drawing sword. They dashed together. The warring Lanzknechte made way, and left large field: it was a recoil of the wave from the basalt, like the scampering of chaff from flails. The two men fought alone. Deianira drew a deeper breath.

It was at this precise moment that the sun, sinking hitherto behind a fork of the Säuling, burned forth a perfect red circle in the inter-space between the riven rock. Its beams, falling upon Caspar panoplied in plated steel mail, made him rich, splendid; a luminous molten glory of cuirass and gorget, arm-piece and helmet and greaves; it welded him to his bossed and prancing war-horse, and turned them, him and it, into a homogeneous Centaur of fluent and refulgent gold.

'O!—but it is beautiful!' The effect was so sudden. It took her breath away. Her hands clasped, rigidly. A swelling wave of feeling flowed in her. Beautiful! And why? This, as usual, was the first question of her analytical mind. As she faintly heard the ringing outcries raised from the clattered metal of the warriors, saw the swift avenging flash of Caspar's blade, she knew quickly why. It was in the nature of a revelation to her. The doer, then, was great as the maker? Conduct as art? Marathon lovely as the Parthenon? The Crusades as Aphrodite? Caspar as Raphael? Was it so, then? And if not, how came this sight so to lift her bosom with the beauty-sense—with love perhaps? It was more than a revelation—it was a regenesis, the birth of a little child, as natural, as definite, as the conversion of Lydia. Not since their meeting-day to this hour had Caspar appealed unconquerably to the predominant in her—her abandonment to beauty. Now he loomed in quite another light: he was immense—he was thrilling! With an aesthetic inquisitiveness, she peered at the illumined interchange of tierce and quart, shrewd thrust, ponderous hew: the two men were nicely parallel in skill, virulence; Caspar not quite so tall, his war-horse larger. Only to look at him, facing so great danger, at so great odds, with so great manfulness, was joy! And now the thought rose bitingly within her that this all was for her sake; of all the pillaged Madonna of Stephan was the inception; and his boy-like sincerity of affection, his minute love for her, races on her errands over Europe, all seemed precious and different, now. She would design, in the fulness of her gratitude, a highly-finished pattern, and send it to Milan to be gold-embossed in arabesque on a suit of plated armour for him, great son of Peleus that he was! She would make her arms a constant ensorcelment about him! But now, sudden fears took hold upon her:—if he never returned? Of this she had not thought. She turned a bitter face from the sight of his cleft helm. But immediately afterwards Caspar, executing a demi-volte on his charger, hewed with his whole momentum, and Roland the Wolf toppled with centrifugal brains from his saddle.

Deianira stood up, most tall, laughing, with clapping hands.

Seeing the fall of his brother, Fritz with a body of cavaliers galloped towards the Count. But the restes of Caspar's band, some twenty men, closed round him. They effected, still fighting, a slow retreat, till the ordnance of the bastions covered them. They reached in safety the castle- gate.

Deianira with haughty, crimson face—proud of him—of herself, that she was his, he hers—had descended the steps of the turret. As she passed along the corridor, she came to the shrine of the Dürer-head; stopped, thinking; then took from her bosom a key, unlocked the door, and entered. For a long time she stood, searching the painter's face; his innocent, azure eyes. Then, slowly, she extinguished the tapers,—all except one; which she held uplifted in her hand.

She waited presently for him on the couch of her own sanctum, devising garlands of gratulation with which to crown him. He came, striding rapidly, his face bloody, passing through to another part, almost forgetful of her in the flush and heat of the moment. And she held out wide arms to him. He started into fury:—just so—just so—she had looked before! The action goaded him to a memory so bitter, that he stamped, with the one roar:

'Woman!'