RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Quests of Paul Beck,"

with "The Unseen Hand"

M. McDonnell Bodkin

Irish barrister and author of detective and mystery stories Bodkin was appointed a judge in County Clare and also served as a Nationalist member of Parliament. His native country and years in the courtroom are recalled in the autobiographical Recollections of an Irish Judge (1914).

Bodkin's witty stories, collected in Dora Myrl, the Lady Detective (1900) and Paul Beck, the Rule of Thumb Detective (1898), have been unjustly neglected.

Beck, his first detective (when he first appeared in print in Pearson's Magazine in 1897, he was named "Alfred Juggins"), claims to be not very bright, saying, "I just go by the rule of thumb, and muddle and puzzle out my cases as best I can."

...In The Capture of Paul Beck (1909) he and Dora begin on opposite sides in a case, but in the end they are married. They have a son who solves a crime at his university in Young Beck, a Chip Off the Old Block (1911).

Other Bodkin books are The Quests of Paul Beck (1908), Pigeon Blood Rubies (1915), and Guilty or Not Guilty? (1929).

— Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection, Steinbrunner & Penzler, 1976.

THE train checked its speed and rumbled slowly into Suberton Junction.

"Tickets, please, all tickets ready, please!" Brisk men in uniform bustled up and down the platform, and carriages were opened and banged.

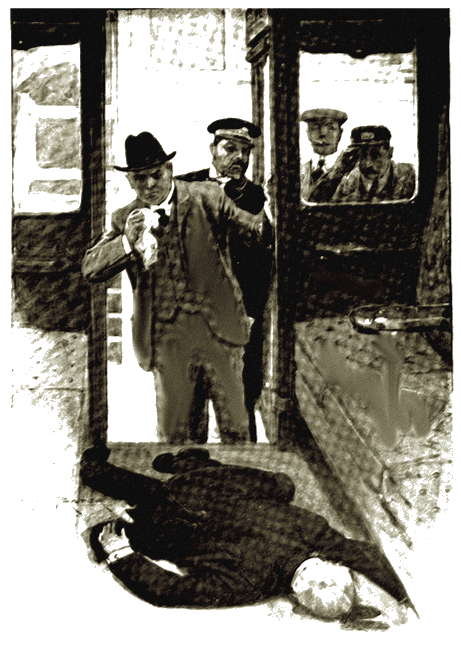

"Tickets, please! Oh! my God! What's this?"

The formal voice broke into a cry as the ticket collector pulled the carriage door open. For there, stretched on the floor in a crumpled heap, a man lay dead.

Unmistakably dead. No living body ever lay huddled up like that. There were great blotches and streaks of blood on the whitey-grey face, and, stooping a little, the ticket collector found that a portion of the skull had been battered in. A foul, sickening odour filled the carriage.

The sight and smell made him faint and dizzy, but he was a man of coolness and resource. He locked the carriage door and raced for the stationmaster—only just in time. The train was trembling into motion when at a word from the collector the station-master rushed on the platform and stopped it.

An instant tumult broke out amongst the passengers. There had been an accident on the line a short time before, and the public nerves were still unstrung.

By magic the word got about—a man found dead in one of the carriages—and the curious crowd poured from many openings on to the platform. But the station-master, with his back to the door, drove them away.

"Take your seats," he shouted, "take your seats, or you will be left behind. We will side-track this carriage and send the train on."

Still the crowd pressed and fought for a peep into this chamber of horrors, fought as for some rich treat, the women worse than the men. In spite of the station-master noses were flattened against the carriage window, and there were guttural mutterings of horror, tainted with a repulsive enjoyment of the tragedy.

A tall young man, well built but languid, came out of a smoking carriage immediately in front—a good-looking young fellow, with straw-coloured moustache and light blue eyes, a cool, imperturbable dandy. He did not press and shoulder with the rest of the crowd, but with glass in his eye sauntered leisurely up to the station-master.

"Excuse me," said he politely, "my name is Albert Malwood. I think it possible it is my uncle. May I look?"

At a word from the station-master one of the porters made way for him to the window. One look was sufficient. The eye-glass dropped from his eye, and his face was paler than before as he turned from the window, but his drawl expressionless as ever.

"It was a good guess of mine, station-master; it is my uncle. I will stay and see this thing out."

He coolly took a seat on one of the wooden benches on the platform, and with fingers that trembled a little picked out a cigarette from a gold case and lit it.

The carriage in which the dead man lay was quickly side-tracked. But it was nearly half an hour before the train, with its load of excited, impatient occupants, again began to draw out of the station.

THERE had gone before them to the London terminus a note of

their numbers, and a brief description of each. Two of Scotland

Yard's sharpest men met the train on its arrival, and all the

passengers were interrogated and closely examined—all

except one.

A tall, graceful woman, who had been foremost in pressing to the window at the Suberton Junction, managed, by accident or design, to slip unobserved through the vigilant cordon of the police at London.

Before the train left the platform at Suberton Junction the station-master wired for instructions to headquarters, and in less than a quarter of an hour had his answer:

MR PAUL BECK GOES DOWN BY NEXT TRAIN TO TAKE COMPLETE CONTROL.

The station-master had never heard of Mr Beck, but Albert Malwood had.

"Met him once," he drawled, "queer-looking cove in baggy trousers. Wouldn't take my fancy as a detective, but they say he's too awfully clever for anything."

WHEN Mr Beck arrived from town an hour later he surprised Mr

Albert Malwood by recognising him at once.

"Sad business about your uncle, Mr Malwood, very sad." His voice was as impersonal as an undertaker's.

"Of course it is very sad, and all that kind of thing," said Albert, and his light blue eyes blinked rapidly, "and I'm very sorry for the old chap, who was always very decent. But I don't deny I have my consolations. I believe he has left everything in the world to me."

It sounded heartless, and the honest station-master stared at him aghast. But it did not need eyes as sharp as Mr Beck's to see that this was a pose, and that the young fellow felt his uncle's death deeply.

"Have a care, Mr Malwood," said Mr Beck, "that you are not suspected of murdering your uncle. You have most to gain by his death, you know."

"I'm sure I don't care," replied Mr Malwood, indifferently; "if it pleases the public to suspect they are quite welcome."

Together the three had come to the door of the carriage that held the ghastly murder mystery. Mr Beck sniffed inquisitively as he unlocked and opened it.

Together the three had come to the door... Mr Beck

sniffed inquisitively as he unlocked and opened it.

A wave of foul air met him full in the face. "Asafoetida," he said. "Why on earth was he drinking asafoetida?"

"He often took it," volunteered the nephew, "as a stimulant for weak heart. Rather liked the beastly smell of the stuff. Hated smoking, though; that's why I travelled in the smoker by myself."

But Mr Beck seemed not to hear. He was busy examining the glass and woodwork of the door. If he found anything he made no sign, but stepped softly into the carriage.

The dead man lay in a crumpled heap on the floor. There was that horrible wound on his head, plainly a blow from some dull weapon struck with superhuman force. The skull was beaten in as an eggshell is beaten in with a spoon.

"He was alone, you say, in the carriage?" queried Mr Beck.

"Quite alone, sir," answered the station-master. "Here is the collector who found him."

The man came forward awkwardly, yet eagerly withal. Plainly he was a little afraid of Mr Beck and his clues. One could not tell where they might lead.

"You looked under the seats, my man?"

"Yes, sir; there wasn't a mouse in the carriage."

"Don't suppose there was."

"The far door was locked," the station-master chimed in, "but both windows were down. I have had this man stationed at the door since the carriage came in. Nothing has been stirred."

Mr Beck nodded approvingly. Braving the abominable stench, he closely searched the carriage—a handkerchief pressed tight to his nostrils. A Gladstone bag was in the rack, and a book lay face downwards, marking the place, on one of the seats. There was nothing else in the carriage but the corpse, which lay huddled on the floor.

With a curious tenderness Mr Beck examined the dead man, having first very gently closed the staring eyes.

The station-master—a puffy, self-important man—grew impatient at the prolonged silence.

"Must have struck his head as he fell—a fit, or something of that sort," he ventured.

He spoke in a whisper to the nephew, but Mr Beck heard, and pointed to the ghastly wound.

"No fall did that," he said; "no ordinary man could do it. There was two men's strength behind that blow, whoever struck it."

"But how?" the nephew asked. "The carriage was empty; there was no one to strike it."

"That's just what I have got to find out," said Mr Beck.

"A troublesome riddle," replied the other. "I wish you luck in solving it."

"Thank you, sir," said Mr Beck, gravely.

The young man spoke lightly, but Mr Beck could detect a note of deeper feeling in his voice.

"He and I were very good friends always," he added after a moment, as if excusing himself for his levity. The languid look had passed from his face. He was plainly much affected, as he turned aside from the carriage window and walked back alone along the platform.

Robbery was not the motive of the crime. The old man's money was in his pockets, his rings on his fingers, his heavy gold lever watch in his fob.

On the watch Mr Beck concentrated his attention. The pocket that held it lay under the corpse, and Mr Beck had to shift the body gently round to get at it. The watch must have struck the floor hard, for the balance staff had snapped with the shock, and the watch stopped. But Mr Beck was not satisfied to take things for granted. It was only after a minute examination that he convinced himself that the evidence was not faked, that the fall had really broken the balance staff and stopped the watch.

"My luck again," he said to the station-master.

"Got a clue already?" asked the younger man, who had strolled back.

"A brace of them," answered the detective, cheerfully. "I've found all I'm likely to find here," he added after a moment.

"There must be an inquest, I suppose?" Albert Malwood said tentatively. "You see, I'm a child in these matters; never had a murder in the family before."

Mr Beck looked at him steadily for a moment. The genuine feeling in his face belied the silly affectation of his words.

"Of course there must be an inquest. Where would you wish it held, sir—in London?"

"Oh! no, not in London if it can possibly be avoided. Why not at his own place, Oakdale? It would be more convenient for the funeral arrangements; the family burying-place is close by. Besides, I'm anxious, I must confess, to keep the beastly business out of the newspapers as much as possible."

"I see no objection," said Mr Beck, after a moment's pause. Then to the station-master: "You can send the body back by a special train?"

The station-master nodded. "Certainly. I suppose I will be wanted over to give evidence. I can arrange that, too."

"Certainly, certainly," said Mr Beck. He knew the man could give no evidence to the point, but his ready assent made a fast friend of the stationmaster.

"To-morrow, then, at two," said Mr Albert Malwood. "That suit?"

"I'm afraid not. There are formalities to be observed. We must communicate with the county coroner and all that. We might manage the day after to-morrow."

"All right then. The day after to-morrow. I am anxious to have the business over and done with."

"The business won't be over and done with," Mr Beck objected gently, "until I catch the murderer or murderess as the case may be."

"If you ever do?"

"I have a notion I will."

"That's all right. Meanwhile we might be making a move."

IN half an hour Mr Beck and Mr Albert Malwood were in the

first-class carriage of a special train on their way to Oakdale.

The body of old Squire Malwood returned in a van to his ancestral

home.

Mr Albert Malwood smoked cigarettes incessantly, and talked of the murder with languid wonder.

"Couldn't be suicide, of course?" he ventured.

Mr Beck answered an emphatic "no" to that.

"There was no weapon of any kind in the carriage," he explained, "the blow killed instantly. It was a blow that the old man could not have struck even with the full sweep of his arms and a heavy weapon in his hands. A blacksmith's hammer struck with a blacksmith's arm might have given such a blow. Count suicide out of the case, Mr Malwood."

"But how——?" began Mr Malwood again, when he was interrupted by the train's coming to a standstill at the station, and a porter's voice shouting "Oakdale."

"Our station," he said to Mr Beck, pleasantly enough. "I have telegraphed for a trap to meet us."

The trap—a light, high dog-cart—was in waiting, drawn by an American trotter, and the two men drove together to Oakdale. The languid Mr Malwood proved himself a superb whip. With wrists of steel he held the fresh, hard-mouthed trotter steadily to his work, while they flew at motor speed along a switchback country road bordered with great elms.

It was a still, calm, sunshiny afternoon, but the swish of the cool air was pleasant in their faces with a breeze born of their own speed. The rise and fall of the road gave momentary glimpses of a country fair and rich with many handsome houses showing through the trees. Mr Beck, who was a keen lover of Nature, was seemingly absorbed in the calm beauty of the landscape, while Mr Malwood impassively smoked cigarette after cigarette, seemingly oblivious alike of the great beast that tugged at the reins, of the detective who sat by his side, of the pleasant country through which they sped, and of the ghastly mystery in which he was so nearly concerned.

They had gone nearly a quarter of an hour in silence, and were a good four miles on their way, when Mr Beck spoke.

"I want to get to London to-morrow," he said; "important business. I can be back for the inquest next day."

Mr Malwood nodded.

"How are the trains?" asked Mr Beck.

"You can catch the morning train after an early breakfast, the one my poor uncle and myself caught to-day. There is a fast train that brings you here from London about twelve next day. Suppose we say one o'clock for the inquest?"

"That will do nicely," assented Mr Beck, genially, as if they were fixing the day and hour for a picnic.

Presently the road widened a little, and a great gate of wrought ironwork showed on the left. The pulling horse was brought to a stand as sharply as a motor by the brake.

"Gate!" cried Mr Malwood, and an old woman, apple-faced and comely, came out of a red-tiled Gothic gate-lodge smothered in roses, and with an old-fashioned curtsey turned the big key and swung the heavy gate wide.

Mr Beck was astonished at the extent and splendour of the grounds. The oaks which gave its name to the place fenced the avenue in stately double row, standing well back in the grass. Clumps of oak dotted the lawn, and in the middle distance merged into a wood. Rabbits tumbled over the grass under the trees. Now the graceful form of deer showed through the windows of the wood, and now and again a pheasant hurtled up clumsily from the underbrush, as if he would tear the thick shrubs up by the roots.

The horse went with a rush through the long avenue, and was brought up almost on his haunches on the wide gravel sweep opposite the stone steps, broad and high, that led to the massive door which opened of itself at their approach.

THE news of the tragedy had come before them. It was writ

plain on the faces of the footmen who stood at the open door

under the portico at the top of the high steps beside the tall,

Ionic pillars of grey limestone, their gay liveries strangely out

of keeping with the sombre background. Plainer still the tragedy

was written on the face of the stout, middle-aged man who stood

behind the footmen in the great square hall.

That face startled Mr Beck with a sudden twinge of recollection. He knew it and he didn't know it. He found the key to the puzzle in a second. It resembled closely the face of the man murdered in the railway carriage. The resemblance was not so much in shape or feature, but in curious identity in expression that grows between people—husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, servants and masters, who have lived long together in close association.

"Jennings the butler," said Mr Malwood, following the questioning look in the detective's eyes. "Lived with the squire, man and boy, for over fifty years. Surly old cock—never liked him myself."

Mr Beck caught the momentary look that Jennings gave his new master from under lowering brows, and decided there was no love lost between them.

"I would like to have a word or two with the butler," he said, "if there is time."

"Lots of time," the young man answered lightly, "we dine in an hour."

Mr Beck found Jennings cautious, almost sullen at first. To the detective's discerning eyes it was plain that the man laboured under some deep emotion in which grief and anger struggled for mastery. But he was one of those men whose feelings are not articulate. If he were sorry for his master with whom he had lived so long and so intimately, he at least gave no sign of sorrow. But there were few men—or women for that matter—who could resist Mr Beck's genial persuasiveness.

"Sit down, Mr Jennings," he said. They were alone in a small study to the right of the hall. "You know I have been engaged to find out who murdered your master?"

Mr Jennings sat down, but for a long minute he spoke no word. Mr Beck waited patiently.

"You will have your work cut out for you, sir," said the butler at last. "The man that did that deed don't mean to get caught."

"I want your help," Mr Beck went on smoothly. "You need not tell me you were fond of the squire; I know it, and I know, too, you will help if you can."

The butler merely nodded with face wholly expressionless.

"Did the squire intend yesterday to go to London to-day?" queried Mr Beck.

"No, sir, I'm nearly sure not. He would have told me."

"What made him go?"

"A letter he got at breakfast. It was in a woman's handwriting, and the squire opened it carelessly, as if he did not know the writing. But it caught hold of him the very first line. His face turned red and white as he read, and the tears were in his eyes. He sat for a minute with the letter open on the table under his hand, thinking. Then he seemed to make up his mind. 'Read that, Albert,' he says, and passes it over across the small, round table to his nephew.

"Master Albert read it slowly in that quiet, easy way of his. It might have been a paragraph in the newspaper for any sign he gave.

"'You must go up to London at once, sir,' he said immediately, 'it's your plain duty.'

"I never in my life saw a man so pleased as what the squire was at that. He bounced up from his seat and stretched a hand across the table to Mr Albert. 'You're the best chap in the world, Albert,' he cried, 'and the most generous. I always thought it, now I am sure of it. I'll take care you don't lose by this, my boy. You're right, you're right; I'll go at once. You've made it very easy for me. Jennings, tell them to have the brougham to meet the morning train.'"

"Who kept the letter?" asked Mr Beck.

"Mr Albert, sir. I saw him ram it into his pocket as I left the room."

More and more it was made plain that Jennings hated the young man and would fix suspicion on him if he could.

"When I came back to the breakfast parlour," he went on, "through the room we're in now, I saw Mr Albert standing at the desk there in the corner. He crossed from that over to the big medicine chest yonder. The squire always kept a medicine chest. You see, he was at the medical profession before he came in for the estate, and liked to physic the tenants. Mr Albert was standing opposite the medicine chest with his back to me when I went in to the squire.

"'Look alive, Jennings,' the master cried, 'or we'll miss the train. I have been an old fool, my man, but things have come right in spite of me.'

"I never saw the squire looking better or happier in my life. Five minutes later I saw him step into the brougham. Mr Albert followed him. That was the last I saw of my old master—the last I ever shall see of him." The old man's voice shook.

Mr Beck was examining the writing-table; he turned to the butler with that look of genuine sympathy with which he so often captured confidence.

"It was a cruel murder, Mr Jennings," he said. "You would like to catch the man that did it?"

"And hang him," cried Jennings, with a sudden burst of savagery. His voice implied that he suspected someone. Perhaps he meant Mr Beck to press him for his suspicion, but Mr Beck went on quietly examining the little table.

It was in perfect order. Letters neatly arranged in piles under paper-weights. One bundle of letters, however, took his attention. It had fallen sideways on the desk. He took a paper or two, and glanced through them. Then he beckoned to Mr Jennings.

"Had your master more paper-weights than those two?" he asked.

Mr Jennings seemed startled.

"I didn't notice it before, sir," he said; "but there was another weight, the biggest of the three—a square of black marble with a bronze Cupid on top."

"Ah! indeed," observed Mr Beck, and moved to the medicine chest. Everything there also was in perfect order. The squire was plainly a man of method. The cork of the bottle of asafoetida had been drawn and replaced. A third of the contents was gone.

Mr Beck drew the cork again, and held the bottle to the nose of the butler, who sniffed in violent disgust.

"Ever know the squire to smell of this stuff?"

"Never, sir, never," he spluttered emphatically.

"Thank you, Mr Jennings, that will do. I won't trouble you any more."

"Dinner will be ready, sir, in half an hour," said Jennings, at once relapsing into the formal butler, as he glanced at a solid gold watch. "Shall I show you to your room, sir?"

There was no allusion to the murder at dinner by host or guest. Young Mr Malwood was plainly a man of deeper feeling than his lackadaisical appearance and manner would suggest. He seemed to shrink from the very thought of the tragedy, and Mr Beck respected his feelings by silence.

THE detective was up betimes next morning, before Mr Malwood was out of bed. He had a solid breakfast by himself, and through Jennings' intervention got the fast trotter harnessed, and was at the railway station an hour and a half too soon for his train.

Nor did he waste his spare time. First he had a friendly chat with the station-master, who in his turn had a word with the guard.

Then with a permit from the station-master in his pocket, Mr Beck set out for a walk along the line which ran from just outside the town between two high and smooth embankments.

Mr Beck walked slowly, with his eyes searching the ground. He walked about a mile on one side of the line and found nothing.

Then he crossed over and walked back on the other. He was half-way back when he came upon a few scraps of white paper lying beside the rails. Plainly it had been raining when they were thrown from the window of the carriage, for instead of drifting away with the wind, they lay fairly close together.

Kneeling down Mr Beck gathered the fragments tenderly into his big hand. With fingers and eyes dexterous from much use, he set a few of the pieces together like a puzzle map, and read. Not a dozen words he read, but it was enough. Plainly he read what he expected to read, for he dried and smoothed the bits of paper tenderly with a silk handkerchief, and put them gently away in his capacious pocket-case.

"My luck," he said softly. "The rest ought to be easy to find."

The rest was easy to find. Two hundred yards farther on he found, half hidden in the grass, a small squirt, such as druggists sell and children love to play with, the body an india-rubber ball, the nozzle of black bone.

Mr Beck smelt the nozzle. It had the smell of asafoetida.

Plainly this part of Mr Beck's work was over, for he walked back at once to the station, filled his pipe, got a morning paper, smoked and read complacently, especially the political news, for a good half hour, until his train puffed impatiently into the station.

He found a first-class carriage reserved to himself.

With a cheery "Good-morning, sir, the guard knows. It will be all right," his new-found friend, the station-master, walked by the carriage door, quickening his steps to keep up with it until the train outpaced him.

Mr Beck took out his watch as they cleared the station. "Twenty-five minutes," he said, put the watch back, and resumed his paper. Twenty minutes later, however, the paper was put aside in its turn for the watch.

His eyes were glued on the dial as the minutes went slowly by, one to each mile.

"One! Two! Three! Four!" At four, Mr Beck jumped from his seat and jerked the communication-cord. The brakes suddenly gripped the wheels, and straining and jarring, the train pulled suddenly to a standstill.

Every head was out of the windows as Mr Beck, stepping briskly from his carriage, got down beside the train, and waved a signal with his handkerchief to the guard.

Almost instantly the train again stole into motion, and the long row of carriages, with staring eyes at every window, swept past the imperturbable Mr Beck.

The train had vanished round a distant curve before he made a move. "Should be on the same side," he said, as he paced slowly along the line with head bent close to the ground.

This time the search was short. He had timed the place to a nicety. Not fifty yards from where he alighted he found a heavy paper-weight—a square of polished black marble with a small bronze Cupid at the top.

"That ends it," said Mr Beck; "now to find the woman and bring her back with me."

Another set of passengers were astonished a little later to see the next fast train for London stop short in mid career to pick up a solitary passenger who sat waiting for it on a bank beside the line as a countryman might wait for a cart at a cross road.

WHEN Mr Beck drove over to Oakdale next day at about noon for

the inquest he brought with him a handsome, dark young woman,

tall and well formed, though a little thin and worn as from

mental strain or watching.

Her pale face was pleasant to look at until she came in sight of Mr Malwood; then for a moment it darkened with a sudden spasm of anger or fear, or both.

"An important witness," said Mr Beck, pleasantly, but made no further effort to introduce them to each other.

Mr Malwood, for his part, seemed as easy and unconcerned as ever. No casual onlooker would imagine that an inquest was about to be held on the murdered body of the uncle who had been a father to him.

But Mr Beck's keen eyes looked through the pose and saw the man was deeply moved.

With all his easy ways, Mr Malwood had been indefatigable in making ready, as quickly and quietly as possible, for the inquest. Not so quietly, however, as he could have wished. One London newspaper had somehow got hold of the news and sent down its representative.

The business was promptly got under way. Half an hour after Mr Beck's arrival the jury was sworn and evidence begun. The collector told of the finding of the body. Dr Hudson described the nature of the wound. There was no formality. Everyone asked what questions they chose, and swore what they chose, regardless of the laws of evidence.

Dr Hudson believed that death was from fracture of the skull, with several hard medical names superadded. The wound, he swore, was caused by a powerful blow from some heavy object. He laid particular stress on the violence of the blow which had cracked the skull like an egg-shell. Death must have been absolutely instantaneous.

Jennings the butler told again the story he had told Mr Beck of the letter and the hastily-determined journey to London.

No one paid much attention. They were waiting for the London detective, who, so the rumour went about, had "got a clue."

As Mr Beck stepped into the witness chair, the two policemen at the door straightened themselves up as for a superior officer. Mr Malwood at the far side of the room, and the girl close beside, both turned their faces in his direction. The reporter from London sharpened a pencil at both ends.

THE beginning of Mr Beck's evidence was merely formal.

Curiosity grew sharper as he recounted his search on the railway

line. He told how he had found the scraps of torn paper. The

squirt and the paperweight were produced in turn.

"The dead man's watch," he explained, "told me, not merely the time the murder had been committed, but the place. As the train passed the same place at the same second next day I got out and found—well, what I expected to find."

"Those scraps of paper, Mr Beck?" said the coroner, curiously. "I suppose you kept them—had they any special bearing on the case?"

"Certainly, sir," said Mr Beck. "They were the torn pieces of the very letter which brought the squire on his fatal journey. I have brought the writer of the letter with me from London."

Instantly all eyes were turned, with a half-frightened curiosity on the girl's face. Was this the clue? Was she the murderess?

"Shall I read the letter, sir?" asked Mr Beck.

"If you can."

"Oh! I have put the pieces together as good as new. I will hand it up to the jury when I have read it. The letter is in a lady's writing, very clear and not long.

"'Sir'—it begins—'You must forgive me for writing. Your son does not know. He is very ill; I fear, dying. For a while he got odd work to do for the papers, and we lived somehow. Three weeks ago he fell sick, and since then we have begun to starve. What little we saved has gone for his food and medicine. My son and myself have no food. If you have a heart at all come up at once and save your only son. You cast him off because he married me in spite of you. We were fools enough to think we could live our own lives. Well, I confess I'm beaten. I give him back to you. You have conquered; you can afford to have pity. I will go away for ever. I can earn my own living as a governess as I did before I met and loved your son. I will swear never to see my husband or boy again if you will only save them. You need not fear to meet me. I will leave the house as you enter it. Only for God's sake come at once, or it will be too late.—Yours faithfully, Annie Malwood.'

"I called at the address, sir," Mr Beck went on in an even voice, while the jury examined the letter, "and I made arrangements for the comfort of young Mr Malwood, who is so much better that I was able to induce his wife to accompany me here.

"I also called on the family solicitor while in London and learnt that the squire had disinherited his son by a will made shortly after his son's marriage. The squire left everything he died possessed of to his nephew, Mr Malwood."

"All this is very interesting, Mr Beck," said the coroner a little pompously, "but it hardly bears on the purport of our inquiry."

"You will forgive me, sir, but I think it does," rejoined Mr Beck, meekly.

"Oh, I beg your pardon; then you have formed some theory of the manner of this most mysterious murder?"

"Certainly, sir. It is exceedingly simple. The murderer squirted asafoetida into the carriage where the squire was seated. The stench compelled the old man to keep his head out of the window. The murderer from the next carriage struck him with this heavy paper-weight—a terrible missile. With the rush of the air, over sixty miles an hour, added to the force of the throw, it crushed the skull like a hazel nut. The old man tumbled back into the carriage where the porter found him. The weight fell beside the line where I found it."

The coroner and jury gazed at Mr Beck—in open-eyed, open-mouthed amazement. The sudden and simple explanation of the mystery took their breath away.

Even the impassive Mr Malwood was affected. He uttered a sharp cry of surprise, and half rose from his seat. Then he dropped back heavily into his chair, which in the dead silence creaked uneasily under his weight. All felt there was something more coming. The hot air of the crowded room seemed to quiver with excitement. A big bumble-bee blundered in through the open window, droned in great circles round the room, and blundered out before the coroner spoke again.

Mr Beck waited, as placid as ever. But the coroner stammered and gasped, and his voice was dry and husky with excitement. His question was wholly illegal.

"Have you formed any idea, Mr Beck, who the murderer is?"

"There is no room for doubt," said the detective, speaking very slowly, his eyes fixed on Mr Albert Malwood, who sat with his head bowed between his shoulders.

"The murderer is the man whose interest it was to stop at any cost the squire's reconciliation with his only son; the man who took the letter, the squirt and the paper-weight from here; who travelled in front of the squire's carriage, who——"

Crash!!!

Albert Malwood suddenly faced round on his accuser, a revolver in his hand. Before the flash left the barrel Mr Beck dropped from his chair, and the bullet smashed into a mirror behind him.

The murderer fired no second shot. With pistol levelled, the smoke oozing softly from the barrel, he made for the door. The crowd gave way before him; the police, cowed by that pale, fierce face and levelled weapon, moved aside.

With pistol levelled, the smoke oozing softly

from the barrel, he made for the door.

In a moment he was through; then they jumped after in pursuit. But Mr Beck was before them. He was at the murderer's heel, through the corridor, and across the broad hall. The front door stood open. But Malwood tripped as he crossed the threshold, and, with the momentum of his great speed, shot out head foremost. With a crash his skull struck the sharp angle of the lowest step. He rolled over on the gravel like a shot rabbit; a quiver shook him from head to foot, and he lay, his face to the sky, quite still. His skull when it had struck the stone was beaten in as you would beat in an egg-shell with a spoon.

Mr Beck was beside him in an instant.

"It's all over," the detective said to the two constables who came up panting, "Sergeant Death has arrested him."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.