RGL e-Book Cover

Based on a painting by John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-1893)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on a painting by John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-1893)

Beginning in 1938, the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate, Inc. marketed a number of short stories by Marie Belloc Lowndes under the general title "They Met Murder on the Way." Some of the stories in this series were published without an individual title. These they are identified on RGL's Marie Belloc Lowndes page in the RGL story files by the first few words of the stories themselves. —R.G.

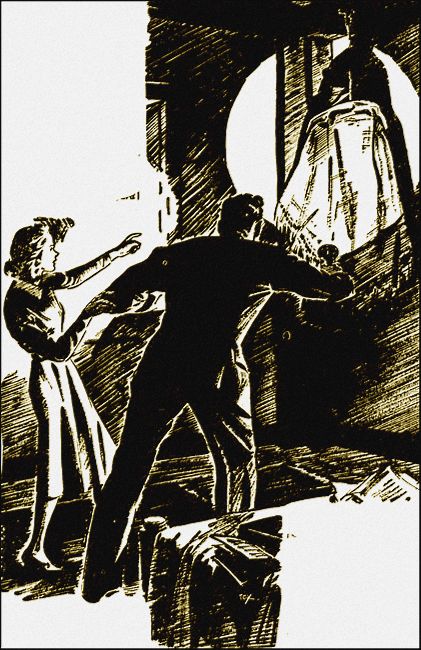

"Oh, how horrible! Mrs. Quicksot has hung herself."

"AND now, my dear little Fräulein, I do believe I have found for you a perfect position!" The homely face of Miss Wentworth was lit up with such a smiling expression of eager pleasure that the girl she had just addressed felt touched to tears.

"And what pleases me so much is the fact that Mr. and Mrs. Quicksot, with whom I have placed you, live in a charming Sussex village where my sister is married to the rector. She will make you welcome I know."

As she spoke she looked across her table at the girl before her. How very, very different was Luise Jansa to most of the refugees! She was fragile, exceedingly pretty in a delicate way; her hair was golden, and her eyes of a clear blue.

Miss Wentworth, who was a simple soul with a kind heart, could not understand why she had found it so difficult to get Fräulein Jansa a nice job. She had had one terribly hard position in a boarding house; in fact, the work there had broken her down.

The truth was that the ladies who came to the Refugee Bureau found this girl too attractive, when they remembered their husbands and sons.

Luise Jansa's heart was now full of gratitude and joy. She had been so terribly unhappy since she left her beloved Vienna and came to England. She had had to share her room with three other refugees at the hostel where she had been placed; they did not like her, and made that plain. For one thing, they were German and she was Austrian.

"I have got your railroad ticket, and you will have to start within an hour, for I have arranged for you to be escorted by Jack Tenby. He is my brother-in-law's nephew and spends a good many of his weekends at Lovesmere."

"Lovesmere?"

"Why, yes, that's the curious name of the village. It is situated on the kind of lake which in England is often called a mere. As to where the Love came in, I cannot say. It used to be called Loversmere. So I believe it is described in the Doomsday Book, for it is one of the oldest villages in England."

She took up a letter from her desk. "The refugee interviewed by Mr. Quicksot last week, fell ill. That is why I can slip you in to this excellent position. He must be an extraordinarily kind man, for this poor Frau Schmitt is deaf, and doesn't even see well, but she was a first-rate cook."

The speaker got up. "And now, my dear, goodbye and good luck! I would like you to take a taxi to the hostel, keep it while you pack, and then go on to the station. I have told Jack Tenby to look out for you on the platform." She did not add that she had put in her note to the young man that he could not mistake Miss Jansa, as she was a very pretty girl with golden hair and blue eyes.

Behold the now happy refugee on the platform of Victoria Station. She had her ticket in her hand, her small cheap suitcase at her feet, and was telling herself that even if this young Englishman did not appear it did not matter, for the name of the place, Harman Junction, where she was to get out, was on the ticket.

Then all at once her hand was grasped and she heard a breathless voice exclaim, "I know you must be Fräulein Jansa! Forgive my being late." Before she knew what happened she was being thrust into a first-class carriage by one of the tallest, darkest young men she had ever seen. He took the ticket she held in her cotton-gloved hands and leaned out of the window. "Hi! guard, I want to pay the difference on this lady's ticket."

He took a ten shilling note out of his pocket, and the guard had scarce time to give him the change before the train glided out of the station, and he sat himself down opposite to her.

"I am so glad you are going to Lovesmere, Fräulein Jansa. It is an exquisite, unspoiled little village, five miles from the nearest railroad station."

Then he paused. "Has Miss Wentworth said anything to you about the Quicksots?" Luise shook her head; it was strange how at ease she felt with this rather peculiar, energetic young man.

"Then let me tell you about them, for they are unlike most people. For one thing Mr. Quicksot is an inventor. He believes that he has found a way of stabilizing the airplane while in the air. Once that is achieved, all aviation will be transformed, and many people who now have an automobile will have a plane instead."

Luise felt thrilled at the thought of living in the home of an inventor.

Jack Tenby went on: "Mrs. Quicksot is a great invalid, and some three months ago she suddenly made up her mind to live entirely in her bedroom and see nobody. That is very hard on her husband, but, according to my aunt, Mrs. Anderson, he is most good and unselfish about it."

"I suppose," said Luise, "that Mrs. Anderson is a friend of Mrs. Quicksot?"

"She would like to be, for she is very kind, but Mrs. Quicksot never made friends with anyone in Lovesmere. She said frankly she hated village life and thought poorly of country people. Yet she has a charming dwelling.

"The Thatched House lies back from the village street and there is a long paved fore-court. But Mrs. Quicksot can't bear any noise, so the fine wrought-iron gate is always kept locked and the side door is the only door used.

"As to the house itself, it is practically divided into two. In the front, the two upstairs rooms are inhabited by Mr. and Mrs. Quicksot. They don't use the drawing room or dining room on the ground floor. The lady housekeeper has the back of the house, of which the windows overlook the mere, to herself."

"It sounds very nice," said Luise tremulously.

"I hope you will find it so, Fräulein Jansa. But I fear you will sometimes be lonely, for Mrs. Quicksot lives entirely alone, and her husband spends all his time in a place he had built in his garden working incessantly on his invention."

Luise will never forget her first afternoon and evening in Lovesmere. Her new employer, who met her at the railroad station, was younger than she expected, and had a thin, hawk-like face. As they motored the five miles he said scarce a word, but as he slowed down in the village street he exclaimed, "There is my wife!"

Sure enough, in a window of the house which Luise at once recognized from the description she had had of it, sat a woman. Her back was toward the light, and she was apparently reading a book.

As they walked in by the side door, Mr. Quicksot observed, "I hope you will be happy and comfortable here, Fräulein. I am sorry that owing to the peculiar condition of my wife's health you will have to sleep on the ground floor; but she cannot bear any noise."

By now they were actually in the house, and Luise noticed that to the left of the passage there was a staircase, while on the right were three doors. He opened them all one after another, and Luise saw a small bedroom, a small living room, and finally a large roomy kitchen. Her feminine eyes told her at once that her predecessor had been a dirty and slatternly woman, and a feeling of pity for the man by her side rose in her heart.

"You will only have to look after the ground floor, and do the little cooking my wife and I require. Mrs. Quicksot cannot bear any one near her but me, so I look after her entirely. I spent my youth in Africa, thus I am quite a handy man."

For the first time he smiled, and it transformed his face making him look quite human and pleasant.

"And now I must leave you for I have work to do. By the way, Mrs. Anderson, the rector's wife, has asked you to supper tonight. You cannot mistake the rectory, it is next door to the church."

A pleasant evening followed, for the rector and Mrs. Anderson were kindly folk, and when Luise got up to leave, her hostess observed, "I'm going away for a fortnight, but I hope we shall see a good deal of you later."

She turned to Jack Tenby. "Please escort Fräulein Jansa back to the Thatched House."

The young man obeyed, and when they were close to Luise's new home, he said in a low' voice, and handing her a visiting card as he did so, "Maybe I ought not to say this, but I do not share Mr. and Mrs. Anderson's liking for Mr. Quicksot. To me there is something curious, strange, and sinister, about that man. You know that I come to Lovesmere most weekends, and you must let me know if at any time I can do anything for you. Please regard me as a friend, Fräulein Jansa."

She murmured a low "Thank you, Mr. Tenby," and then he left her to find her own way along the path to the side door of her new home.

To her surprise that door was locked. She rang the bell, and Mr. Quicksot, with a lighted candle in his hand, admitted her silently. He did not even say "good night" as he turned and went upstairs.

As the days drifted by, more and more did Luise Jansa feel the strangeness of her position. She felt ever increasingly lonely, and longed for Mrs. Anderson's return to Lovesmere, for that first evening that she had spent at the rectory remained in her mind as her only happy hours since she left Vienna.

When not with his invalid wife, the master of the house was in what he called his workshop, and the housekeeper had orders never to disturb him for any reason whatever. The only thing of which he ever talked was his invention. Then the usual expression of strain would leave his lean, striking looking face, and he would tell of the wonderful effect on the world it would make.

"Everyone will fly then! There will be aerial trains, and the automobile will become as obsolete as is now the hansom cab."

Sometimes Luise would follow what he told her with interest. But her mind did not dwell much on Mr. Quicksot; the man to whom she often threw a grateful thought was Jack Tenby. She sensed that he had really meant his parting words, "You know that I come to Lovesmere most weekends, and you must let me know if at any time I can do anything for you. Please regard me as a friend, Fräulein Jansa."

Carefully she kept the card he had handed to her; not that she supposed she would ever need it.

And then the monotony of the strange life she was leading was broken, for Mr. Quicksot came into the kitchen where she spent much of her time, and explained, "I want you to go to London and draw some money, Fräulein! Up to now I have had to go about once a month to do so, but I do not want to leave Mrs. Quicksot for so long. She is less well than usual."

Luise felt overjoyed at the prospect of being away from the Thatched House even for a few hours and, as her face brightened, he went on, "I shall give you a letter for the bank-manager, and you will have to take with you my wife's power of attorney. The money you will draw is her money, not mine."

He was staring through the window on to the wintry, sullen-looking sheet of water. "And now I come to a rather important matter," he observed.

He had been standing and suddenly he sat down. Drawing up his chair close to where she was already seated, he went on.

"It is possible that the gentleman you will interview will ask you certain questions with regard to my wife. I mean as to how she is, and so on. Now you will very much oblige me, Fräulein Jansa, if you will keep to yourself the fact that you have never seen Mrs. Quicksot."

He waited a moment, "I hope you will not be asked any questions of the kind, but if you are, then I earnestly beg you to say that though she leads the life of a complete invalid, she is otherwise quite normal."

The next morning came the cold journey to London, and visit to the bank. To Luise's intense relief she was not asked the kind of questions Mr. Quicksot had warned she might expect, for the manager evidently took it for granted she was in personal attendance on Mrs. Quicksot.

He did, however, say kindly, "I understand from Mr. Quicksot's letter that you are an Austrian refugee, Miss Jansa, and I hope you will accept a word of sympathy. Beautiful Vienna! I can't bear to think of it now." The girl bent her head to hide the tears in her eyes. Never once had her employer alluded to her forlorn condition.

The bank-manager went on, "I fear your position with this far from happy couple can't be a pleasant one."

"Mr. Quicksot has done what he can to make me comfortable," she faltered.

"I have no doubt of that, for it is to his interest to have a kind, refined young lady as companion to his wife. But he thinks only of that peculiar contraption he has invented, and as for Mrs. Quicksot—" and then, as if he felt he had been indiscreet, he stopped suddenly.

The day after Luise returned to Lovesmere, Mr. Quicksot paid the bills in the village. When he came back he said he was sure he had paid an account for which he had been charged again, and would Fräulein Jansa look for the receipt?

Late that afternoon, Mr. Quicksot being out in his motor, she began her search, and at last she found what she had been told to look for in a heap of bills that had been left in a drawer of the big old dresser which filled one side of the low-ceilinged kitchen. Yes, there it was, duly receipted!

And then, all at once, she noticed that in a corner of the drawer was an envelope on which was written in a firm hand:

For the Cook-Housekeeper

A list of her duties

She took it up, and noticed that the ink was slightly faded.

A list of her duties? Mr. Quicksot like all inventors had but one thought in his mind. She sensed that he enjoyed her excellent cooking, but he had not uttered a word of approval after she had spent three days of hard work making what was her side of the house fit to live in.

As she swept, washed and polished, she had frequently thrown a thought to the invalid woman who she felt to be at once so near and yet so far. And as the days had gone on, she had asked herself again and again whether Mr. Quicksot was really the sort of man to keep everything clean and shipshape in his own and his wife's rooms as he had boasted he could, and did so.

She now looked at the envelope consideringly. After all, she was the housekeeper now, so surely she had the right to open that envelope and see what was written there? And it would throw light on Mrs. Quicksot's character. She often speculated on what this invalid woman was really like. The list might even show if her mind was, as a matter of fact, deranged.

It was dark in that corner of the kitchen, and Luise walked across to the diamond-paned window which overlooked the mere. There slowly, she broke the seal, and took out of the envelope the sheet of paper it contained.

Instead of the list of duties she had expected to see was written: "Statement to Those it May Concern."

Then followed some close lines of handwriting. And as she read slowly what was written there it was as if her heart stood still in fear and deep dismay.

"It has been born in upon me for some time that my husband, Ralph Quicksot, has come to hate me. Also he feels me an obstacle in his path to fame and fortune. I should not feel my life worth a moment's purchase, were it not that my income of 500 pounds a year dies with me, and is still very necessary to him in connection with what is, I am convinced, a fool invention. When I was still in love with him, I unfortunately gave him my Power of Attorney, so he is free to draw on my bank account whenever he wants to do so. He once nearly killed me in a fit of rage, and should I disappear I urge whoever reads this statement to immediately inform the police."

Luise read Mrs. Quicksot's sinister statement again and yet again. Could what was written there be true? She remembered how Mrs. Anderson had made it plain she deeply pitied Mr. Quicksot, and thought his care of his disagreeable invalid wife touching and noble. The Austrian girl knew the important part money plays in most human lives. If it became known that Mrs. Quicksot had passed the border line between sanity and insanity, she would surely be put in an asylum and her income sequestered.

Luise hurried into her bedroom and hid the envelope in the cheap suitcase which was the only thing in her possession which had a lock.

Now there began hours and days of wretched uncertainty and despondency for the unfortunate refugee. Her mind was always dwelling on Mrs. Quicksot's statement, and she would have given anything to have felt she had the right to show it to some wise, older person.

Again and again she told herself that everyone agreed that the inventor's wife was disagreeable, and had an unpleasant nature. As to that, one thing was quite plain: Mrs. Quicksot had no belief in her husband's invention. But yet another thing was surely true? This was that Ralph Quicksot, since his wife had taken to her strange solitary way of life, had shown her a care and devotion which very few men would have done to so selfish and peculiar a helpmate. Surely, then, Luise Jansa owed loyalty to him, and not to a woman she had never seen?

Meanwhile, Jack Tenby found himself constantly thinking of the Austrian girl refugee, for though he would have indignantly denied that he had fallen in love at first sight, yet it was true.

And now, for the fourth time, the young man was spending a weekend at the rectory, and, while he was wondering whether he could hope for a chance of seeing Luise without someone else being there, Mrs. Anderson observed: "I had meant to ask Fräulein Jansa to spend the evening with us, but Mr. Quicksot has unexpectedly had to go to London for the night, and I'm sure that girl is far too conscientious to leave that poor sick woman alone in the house. Not that it would make any difference, for Mrs. Quicksot still persistently refuses to see her."

The rector exclaimed: "Poor little fraulein! Why shouldn't we find out if she would come in to supper this evening? She needn't stay long."

Jack chimed in with, "I'll go to the Thatched House now and ask her."

It had turned dark early on that November afternoon and Luise, after having tried to lose herself in a book, just lay back in her chair and listened.

Listen? One of those things that constantly surprised and disturbed her was that she never heard any sound issuing from Mrs. Quicksot's room.

There came the sudden tinkle of the side door bell, and she started violently. Mr. Quicksot had warned her to be careful when she answered the door, for the English countryside is full, even now, of the shell-shocked human remnants of the Great War. When in the passage, she called out, "Who is there?" And, oh, the relief of hearing Jack Tenby's voice, "I have a message for you from my aunt, Fräulein Jansa."

She opened the door and his heart began beating quickly as he saw her slender, rounded figure outlined against the lamplit kitchen. More than ever did he feel the kind of ache and longing he had never yet felt for any girl.

They sat down by the fire which Luise often told herself was the only cheerful spot in the place. But after Jack had conveyed his aunt's invitation, Luise shook her head. "I couldn't possibly leave the house with Mr. Quicksot away!"

"I'm afraid you're right," he said reluctantly, then he asked, "Is it really true that you've never seen Mrs. Quicksot?"

Luise hesitated, remembering her promise to say nothing of her employer's concerns to any inquisitive questioner. But somehow she felt that Jack Tenby was different, and she longed to tell something of the curious state of things existing in the Thatched House. Also, this young man had offered her his friendship.

"Not only have I never met Mrs. Quicksot, but if she were taken ill I couldn't get at her, for Mr. Quicksot always keeps her in her room and his own next to hers locked, and he took away the keys with him today!"

Jack Tenby felt indeed astonished. "But what would happen if the house got on fire?" he exclaimed.

Her voice sank to a whisper. "The poor lady would burn to death."

No doubt because she felt so forlorn, she muttered, "Perhaps it's foolish of me, but ever since Mr. Quicksot motored off this afternoon I've felt afraid, and I don't know why."

He leaned forward and gazed into her beautiful eyes, "Please don't think it's idle curiosity if I ask you if you honestly like Mr. Quicksot? I sometimes wonder if he is really kind to his wife. They used to quarrel a good deal."

There crept over Luise Jansa a fearful temptation, and she yielded to it. Getting up, she left the kitchen, to come back a few moments later with an envelope in her hand.

"I want you to read what is in there, Mr. Tenby. Ever since I found it I have felt so miserable, also so uncertain as to what I ought to do."

Sinking down on a chair, she lay her head down on the kitchen table and began to sob. Yet how great was the relief of sharing her secret with someone she believed she could trust!

Jack Tenby stared down at the envelope on which was written: "For the cook-housekeeper, a list of her duties."

Had Luise given him the wrong envelope? It looked like it. All the same, he drew out the sheet of paper, and approached the table as he read what was there in silence. Then he waited a moment. "I feel we ought to do something about this. I told you the first time we met that I did not like nor trust that man. Of course, it is to his interest to keep his wife alive as long as he holds her power of attorney, and so can draw her money. But I can't help wondering how he treats her."

He looked at his wrist watch. "I can't stay any longer now, but after every one has retired in the rectory, I'll come back and we will go up and see if I can't force open Mrs. Quicksot's door. Of course, if I succeed, it may make her both alarmed and angry, for she has a vile temper, but I feel it's our duty to find out what her condition really is. Also, we can tell her, with truth, that she will have brought it on herself by writing that statement."

He gripped Luise's soft hand and held it in his strong grasp for quite a while. As he let it go he muttered, "I want you to know that I would run any risk to help and protect you."

Luise lost all count of time as she waited for the return of Jack Tenby. She felt, for the first time since she had reached England, absolutely at peace. It was so wonderful to know that there was a human being who had actually declared he would run "any risk" to help her.

She even dozed a while, and awoke to hear midnight striking from the clock tower of the little gray stone village church which dated from the Crusades. Ten minutes went by slowly, slowly, then all at once she heard his footsteps running down the empty village street, and then up the path to the side door of the Thatched House.

He drew her out-of-doors, and murmured, "Now for our plan of campaign. Perhaps you had better go upstairs first, and call out, 'Mrs. Quicksot!' After all she must know you are in the house, with the sudden sight of a man breaking open her door might frighten her."

They went in, and Luise obediently went up the staircase she had ascended only once before. When on the uneven wooden boards of the upper passage, she called out as arranged, "Mrs. Quicksot! Mrs. Quicksot!"

They both listened intently, but it was as if a deathly silence brooded over the old Thatched House.

Turning around, Luise beckoned, and the young man tried the handle of the door. Then he put his weight against it. It was like leaning on a rock. It held fast as she had felt sure it would do, for the door was of strong oak.

As soon as they had gone downstairs, Jack exclaimed, "There is now only one thing to do! The loft in Mr. Quicksot's workshop is reached by a stepladder, isn't it? With your help I can get that ladder over the side wall into the fore-court, and place it so that it will reach to the window where that poor woman spends so much of her time. The top of the window is always open a few inches, and if I can manage to push it down we can get into the room."

Twenty minutes later, Luise, standing at the foot of the stepladder, heard her friend's muffled voice say, "Come right up, I have a flashlight, and if Mrs. Quicksot is asleep we may see all we have to see without disturbing her." A few seconds later they were both standing just within the dark room.

Jack shut the window, and pulled down the blind. Then he turned his flashlight so that it illumined only a patch of carpet, which Luise noticed was thick with dust. Growing bolder as he heard no sound he began turning the torch all around the room.

There was a dressing table to their left, but nothing was on it, and it was an eerie sight to see himself and Luise dimly reflected in its dirty mirror.

Quickly he flashed the light to their right. Yes! There is the bed; but he and Luise each gave a stifled gasp of surprise, for it was unoccupied, and covered with books, papers and maps.

"Do you think she can be sleeping in the next room?" whispered Jack.

As only answer Luise suddenly clutched his arm, "Look over there in the corner," she cried. "You lit it up just now as you flashed the light around." Then as he lit up the corner again, "Oh, how horrible! Mrs. Quicksot has hung herself!"

For a few seconds the young man thought that what Luise had just said was true for, hanging from a high hook, was suspended a woman's form.

Her face was concealed by a large hat, and about her shoulders was draped a shawl. At once he recognized both shawl and hat as having been always worn by Mrs. Quicksot when she sat by the window.

But after a moment of horror-stricken surprise, he said quietly, "It's not a body that is hanging there." He took Luise's hand, and together they went up to the strange, sinister-looking, life sized figure.

Jack put out his hand and pulled the shawl aside.

"Why, it's just a dressmaker's dummy! Look—" and he swung the figure forward.

Then he unhooked it, and set it down on the only chair in the room not covered with thick dust. Moving that chair across to the window he propped the figure up against the wall and drawing up a small table, he took a book from the bed, and opened it there.

"Look!" he cried again, "that's exactly what Quicksot has done with that dummy again and again, in the last three months."

He groped his way to the door which separated the room in which they were from the next, and opened it. Everything there was more or less clean and shipshape, and a comfortable bed was against the wall.

"But what has happened to her? Where can she be?" asked Luise.

"I'm afraid her body isn't far away from here," said Jack quietly. "She wrote, poor soul, 'if I disappear, notify the police.' That is what I am going to do as soon as I have taken you down to the rectory."

It was three in the afternoon when Ralph Quicksot drove up to the Thatched House; and there was a balked expression on his face, for he had not been successful with the emissary of a foreign power to whom he had hoped to sell his invention.

As he stopped his car, a dozen police officers seemed to spring from nowhere, and they formed a cordon across the village street.

He looked this way and that, hoping to escape, and then suddenly he became aware that on the path leading to the side door of his house, there lay something hidden by a tarpaulin. It was the body of his wife; she had been found six feet below the earthen floor of his workshop.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.