Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

Cosmopolitan, January 1937, with "Christmas Armistice

A new and magnificent story of the Christmas season by

the famous author of "Green Light" and "White Banners."

KEATING had lost his fountain pen. It wasn't a showy pen but a very good one, and he was hopeful of finding it.

All of Jim Keating's personal gadgets were purposely simple and inconspicuous. The watch he carried looked as if it might have cost about a dollar. The other internes teased him about his cheap watch, though they had to concede that it kept better time than the hospital clocks.

Jim had never bothered to tell them that inside the tinny-looking case there was an expensive twenty-three-jewel movement. He liked, and could easily afford, good things; but he abhorred display.

The missing pen had no sentimental value for the tall, sandy-haired, blue-eyed Keating, for he was not a sentimental person—a fact to which at least half a dozen well-favored young nurses could have testified. He had bought the pen on the first day of his freshman year. It had accompanied him through college and medical school and these three arduous years of his interneship at the General Hospital. It suited him, and he wanted it back.

There was but little likelihood that the fugitive pen had secreted itself in his snug study-and-bedroom suite on the fourth floor of the annex where the internes lodged, but Jim had sedulously inspected his diggings, item by item. A zealous group of his white-clad neighbors had cheerfully assisted in this search, one detachment turning his study upside down and inside out, while the rest of them were taking his bed apart, after which they all left to pursue their pressing duties.

Next morning a notice appeared on the bulletin boards reporting Doctor Keating's loss. It caused no end of amusement, for it was common knowledge at the hospital that the affluent young man didn't have to agonize much over a misfortune of this nature.

But nobody had ever seriously begrudged Jim Keating his money. Certainly he had made no show of it. You wouldn't have suspected from his manner or his habits that he had come into a large inheritance. A few of his fellow internes knew how wealthy he was, judging by the promptness with which he offered them unsecured loans; but they weren't telling.

Occasionally wisps of gossip floated about to the effect that Keating often kept track of convalescents who left the hospital ill-prepared to paddle their own canoes. But these stories were difficult to verify, the alleged beneficiaries shying off at questions.

Outwardly, Jim Keating was on an equal economic footing with the rest of his industrious tribe, most of whom were notoriously hard up. He had even listed himself as a donor on the transfusion registry, and periodically sold his blood at the current rates. It wasn't a pleasant experience, but the other internes had to endure this discomfort to help pay their expenses, and Jim was willing to share it with them. Naturally, underneath all their bantering, they admired him inexpressibly.

Everybody at the General read the notice about Keating's lost pen, and laughed. It hadn't struck Jim that there was anything funny about it. At three o'clock, when the afternoon shift of floor nurses came on, he paused at the fringe of a starched huddle about the desk in the women's surgical.

"I don't suppose," he ventured, "that any of you happened to find—"

"Your pen!" they laughed, almost in concert. And then the Atkinson maiden, who had charge of the ward, remarked, "Everybody has been searched. Nobody has it. We were just making up a purse."

There was tense silence for a minute, the girls studying Jim's face with interest, for no one of them had ever heard him openly confronted with the implication that he was well-to-do.

He drew a tilted grin and drawled, "Thanks—but don't sprain yourselves. It didn't cost very much." They laughed again, relieved that he had taken their teasing pleasantly. As he moved away, it occurred to him that his zeal for the recovery of his pen was making him look silly. He resolved to stop hunting for it, and buy a new one.

THE suave section manager of the big store had instructed

Keating to take the third aisle and proceed halfway down. It was

late afternoon. A chilly mid-September rain had crowded the place

to suffocation, but not with people who needed writing

materials.

As Keating neared the tall glass case, stocked with every conceivable type of fountain pen, his attention was instantly drawn to the young woman in charge of it, an attractive brunette, probably twenty-four or -five years of age.

Facial characteristics had a scientific interest for Keating. Ever since old Toothy Becket had made him do a paper on noses, when he was a junior medic, Jim had given much time to an amateur investigation of physiognomy. He knew it was not an exact science. All manner of quacks had tinkered with it. But, say what you might, it was startling how much you could learn about a patient's character merely by glancing at him.

Take noses, for example. You couldn't go back on your nose. If it was sharp-tipped, you were likely to be irascible, suspicious, hypersensitive. You might deal severely with these unlovely tendencies, but in the process of building up a defense apparatus you were apt to develop smugness and taciturnity, with a martyr complex waiting for you just around the corner.

The physician could be safe teasing a round nose into something like conciliation and amiability in a moment of stress, but he must not attempt facetiousness, on a similar occasion, with a thin nose. The thin nose would sniff and sulk over playful comments.

The eagle nose was capable of high courage. It was haughty, too, but you could generally count on its bravery, an important thing to know when forced to do a tedious and painful drainage.

Wide-open nostrils were high-strung, erratic, impatient and had to be indulged. You also had to be on guard when extending opiatic relief to persons with high, wide nostrils, for they took to addictions like a duck to water.

Keating knew a lot about noses—and eyes, too.

For instance, if you had an oval, adorable, madonna face, blue-black hair that curled naturally at your temples, a patrician frontal arch, classically sculptured brows and an intriguingly pensive mouth, it was inevitable that your dark eyes should be deep-set and shadowed. Otherwise, something was the matter with you.

This girl's eyes were just a little wider open than her type permitted, but only an experienced student in this unfamiliar field would have noticed it. In fact, anyone else might have thought that these brilliantly alert eyes were a pleasing bonus offered to a young woman with whom Nature had already dealt in a spirit of generosity.

Keating was at once fascinated and dismayed. He was not easily susceptible to feminine charms. It was a literal truth that he had "no time for women." The hospital worked him like a mule in a mine. He had almost no social life. All the young women he saw, at close range, were more or less out of repair. It struck him that this was one of the most beautiful girls he had ever seen.

"You would like to see a pen?" she asked. Her tone was a deep, throaty contralto, as was to be expected, but it had a slightly strained timbre, hinting at neural tension. She tried to discipline it, but it was easy to see that her whole nervous system was taut as an E-string. There was a flush high on her cheeks. It was not rouge. The shapely lips had been touched up, but not the cheeks.

Keating sketchily described the pen he desired—"something serviceable, plain, not too blunt, with no tricky novelties in the filling device"—meanwhile inquisitively searching her eyes with an appraisal that she found slightly disconcerting. He noted this and deplored it, for it was obvious that she thought he was sparring for a quick acquaintance.

She reached down into the case, brought up a modest black pen; and, poising it over the row of open bottles, inquired without looking up, "What color do you use, please?"

"Well," he replied uncertainly, "I prefer whatever color happens to be in the most convenient bottle when I find myself out of ink."

The girl smiled faintly, dipped the pen into the green bottle, gave it into her customer's hand, and pushed a little block of paper toward him. As she did so, Keating observed a barely perceptible tremor in her slim, white fingers. It wasn't that she was shaky. Not another person in the big store would have noticed it. But Keating was looking for it. He made a few tentative strokes and remarked that the point was too fine.

The blue-black head bent toward the depths of the case again, Keating casually offering the comment that it was quite a snappy day for September.

"Is it?" she said indifferently. "I hadn't noticed."

"No," drawled Keating, "you wouldn't; that's so. You're never cold—any more... Are you?" he insisted, when she did not reply.

She flushed with annoyance, but made a resolute effort to keep her temper. After some hesitation, she trusted herself to say, with dignity, "I can't think why you should want to know, sir, but it's true... Try this one, please. It's a little broader."

Keating made some scratches with the pen, glanced up, surveyed her again, kindly but critically, and said, "You're never cold, but you're always hungry, aren't you?"

The girl bit her lip with exceptionally pretty teeth, and nodded a begrudged affirmative.

Then Jim Keating knew that his diagnosis was correct and complete. He drew the pad closer under his hand and wrote, "An exophthalmic goiter, in its primary phase, is not easily identified." Returning the pen, he commented quietly, "It's a bit too stiff."

She studiously read what he had written, shrugged slightly, and produced another pen with which she wrote, under his message, "Meaning me, I suppose."

"I think you will find this one a little softer," she said.

The color was creeping up her throat. Keating was sorry and wondered whether he should have intruded upon her anxiety, for he could easily picture her inquiring of herself why she was nervous and wishing she had the courage to ask somebody who might know. Probably couldn't afford to stop working. Of course it wasn't any of his business, but—she really was such a dear!

He took up the pen, and she watched him closely while he wrote, "Yes—and you'd better do something about it before it hurts your heart."

"I'm afraid," he said, "that this one is rather too generous."

She nodded, explored for another pen, remarked that she hoped this one would be about right, and wrote, "I suppose you are a doctor, but you probably aren't a very good one, or you wouldn't have to be drumming up business by diagn—" The pen faltered in the middle of this word that she hadn't had occasion to use very often. Keating, gently taking the pen from her trembling fingers, finished "diagnosing" for her, and restored the pen.

She glanced up anxiously to see if he was amused, but found his eyes sober, compassionate. He waited for her to finish the sentence. She shook her head and put down the pen.

"Go on," said Keating softly. "Get it off your mind."

She shook her head again but, after a momentary indecision, wrote, "We're paid to be polite."

"But you're not polite," wrote Keating. "It's part of your disease. I'll bet that two months ago there wasn't a sweeter girl to be found in—"

Apparently that was all she could take, and she broke in upon his correspondence to inquire testily, "Do you think of taking this pen, sir, or shall I keep on trying?"

"I'll take it," he said, drawing out his wallet.

"If you find it doesn't suit," remarked the girl dutifully, "we will gladly exchange it... Thank you, sir. Four-fifty out of ten."

When she returned with the change, Keating had written on the pad, "Sorry I offended you. I wouldn't have hurt your feelings for the price of everything in this store. Don't put off doing something about your trouble. It's important and it must be attended to without delay."

Her eyes were misty as he smiled into them. There was a great deal more tenderness in the look he gave her than he had any right to disclose. For a brief instant she seemed to respond appreciatively. Then, flushing hotly, she began gathering up the scattered pens.

Sincerely distressed over the unhappy outcome of their strange encounter, he ventured a final message: "Come to the General Hospital—east wing—outpatient department—any evening but Sunday, seven to nine. If Wednesday or Saturday, inquire for Keating."

She continued replacing the pens. It was clear that the interview was over. He had made himself too officious. Her manner indicated that she desired nothing further of him but his departure. Keating tore off the page he had written, as if to say that he realized it was of no interest to her, crumpled it into a tight little ball, and tossed it carelessly onto the counter. "Good-by," he said kindly. The girl did not reply.

She watched his tall figure wistfully until it disappeared in the crowd. Then she picked up the paper he had thrown aside, and tucked it into her pocket.

Patricia picked up the piece of paper Doctor Keating had thrown aside.

JIM KEATING tried to give himself with full devotion to his

hospital duties, next day, but found his mind distracted. As he

reviewed yesterday afternoon's odd experience, he became

increasingly distressed over the whole affair. It was obvious

that the girl was worried about herself. He had had a chance to

render her a valuable service, but had bungled it by a na´ve

display of personal interest. She had interpreted his honest

concern for her welfare as an attempted flirtation. And if she

thought he was making capital of her illness, it wasn't much

wonder she was offended.

Analyzing his motives, Keating made an effort to persuade himself that his interest in the girl was purely humanitarian, but in all honesty he knew that she meant much more to him than a needy case. It seemed rather silly to be wondering whether he was falling in love. In his opinion, love was based on mutual attraction; and surely there hadn't been any indication that this girl liked him. So he knew it wasn't love that had upset his normal processes of thinking. It was sheer pity; that was all. He would have been just as solicitous, he reflected, if the girl had been fat and frumpy; after which he told himself he was a liar, and resumed his self-reproaches over the way he had dealt with her.

It was his night to have charge of the outpatient department, and as seven o'clock neared he found his hope mounting. She would have had time to think it over, and would have forgiven him; or, if she hadn't, she would have become sufficiently worried about herself to take his advice and seek the clinic. He spent a restless evening. Every time he had finished with a patient, he came out into the reception room, hoping to find her waiting. But she did not come.

Sunday was a long day. Late Monday afternoon, Keating decided he couldn't bear the suspense any longer and went downtown to exchange the pen. His girl was not there. Another saleswoman was behind the counter. She was obliging. He disinterestedly pocketed another pen and asked, "Would you mind telling me what has become of the young lady who was at this counter last week?"

"She has left, sir," replied the clerk.

"Could you tell me her name?"

"We aren't supposed to do that."

"Wise rule, I should say," agreed Keating, "though there might be exceptions made to it, if... See here, I'm in a position to do this young woman a favor. It's important."

The clerk looked him squarely in the eyes for a moment, and replied quietly, "I presume that your reasons for wanting to find Miss Weston are all right, but I'm not permitted to tell you her name."

"Thanks," said Keating gratefully. "I don't suppose you would dare tell me Miss Weston's address, either."

"I really don't know Patricia's address, sir. It might be in the city directory." They exchanged a grin, and Keating sought the directory. Patricia Weston wasn't in it.

After that, every spare hour was spent in the quest of Patricia. Nothing else mattered. Keating lost his appetite; became absent-minded, fidgety, detached. On the evenings when he was in charge of the outpatient department, he kept his eye on the door—what time he wasn't otherwise engaged—with the diligence of a cat at a rathole.

He visited every good store in town where pens were sold. He searched the faces of all the young brunettes he passed on the street. Everybody at the hospital knew there was something the matter with Jim Keating. The internes advised him to snap out of it, whatever it was, and invented diversions for him. But it was no good. Keating had lost The Girl.

NEXT Wednesday would be Christmas. The flavor of it had been

in the air for nearly a month. Downtown, the streets were packed

with people and the people were packed with parcels.

Discipline had loosened up a bit at the hospital, nurses begging time off to make shopping expeditions and relieving one another for the purpose. Several internes had secured leaves. They could be spared. For a little while new patients would be emergency cases. Nobody who could put off an operation would consent to be hospitalized at this season.

Keating, to whom Christmas was going to be just another day, took over all manner of jobs on behalf of colleagues fortunate enough to have social engagements. He was glad to do it. The busier he was, the less time he had to think.

On Sunday, Ted Lovejoy came breezing up to say that his mother and sister Jane were in town to spend Christmas. Would Jim have dinner with them to-night? Please! And so—because there was no particular reason why he shouldn't—Keating accepted.

At six-thirty, while he was dressing, the telephone rang.

"Jim? This is Orloff. How about a little transfusion?"

Keating liked Fatty Orloff, but there was no reason why the west wing shouldn't dig up its own donors.

"Can't you find anyone else?" he protested. "I'm just putting on my boiled shirt to go to the first party I've been to since I was in the eighth grade."

"That's tough, old man, but this case is a Four, and we haven't any. If you were silly enough to have blood like that, you've got to take the consequences."

"Well," drawled Jim reluctantly, "I suppose I'll have to come. What is it? Some fool trying to show off how cute he was in his papa's flivver?"

"No, it's a hyperplastic."

"Must have been a rotten job if you have to transfuse it."

"NO—it's just one of those things. Spellman operated. We

put her to bed and the lesion kept on oozing. Brought her back

and looked for bad ties, but that wasn't it. She won't stop

it."

"Very well, I'll be there pronto." Keating was about to hang up. Then he added, "Happen to know her name?"

"Weston. Patricia Weston. And if you don't say she's the—"

Jim banged the receiver back on the hook, tugged off his dress shirt and made haste to get into his white duck. His heart was pounding. He was going to support Patricia with his blood...

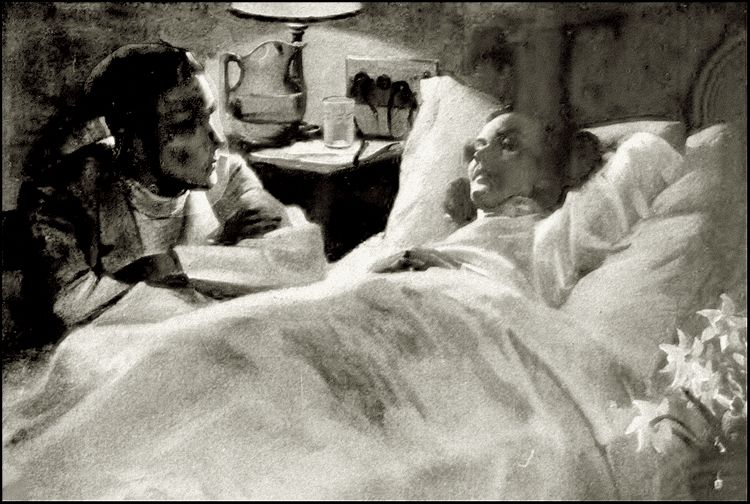

She was weak but conscious, for they had operated with a local. The experience had quite unnerved her, and it was evident at a glance that Patricia had had about all the punishment she could take.

By custom, Keating would have stretched out on the adjoining table with no more than an interested glance at the recipient. But now he threw all precedent to the wind and amazed the little group by walking directly to Patricia's side. She looked up slowly, dully.

Gradually her eyes lighted; she smiled faintly, and whispered, "Oh, so it's you."

Jim's eyes were hot and misty. "Don't worry, Patricia," he said softly. "Everything will be all right now."

She closed her eyes, drew a shuddering little sob that tore at his heart, looked up again—and smiled.

The Bentley girl, famed for being one of the hardest-boiled and most competent surgical nurses in the west wing, dabbed at Patricia's tears with a wad of gauze, dabbed at her own, sniffed audibly, and handed Doctor Spellman a scalpel. Keating took to his table, outstretched.

"Well," muttered Doctor Spellman, deep in his larynx, "I'll be damned!"

"Make mine the same, please," remarked Orloff, who, being so fat, could say anything he liked to his betters.

They scrubbed Keating's arm with antiseptics. He felt the familiar sting of the lance and sensed the accelerated heart action, informing him that the good work was now going on. His throat was thick and his eyes were wet. He had found Patricia!

UNDER ordinary circumstances, Jim would have been relieved of

his duties for a day. The hospital was particular about

safeguarding the health of donors. But early the next morning,

the senior interne of the east wing was making an excursion to

inquire about Patricia.

Immediately after the transfusion he had said to Doctor Spellman who, with Orloff, was washing up, "Is Miss Weston in the open ward?"

"Well, it's a ward case, but I've had her put in a private room. She'll be better off, out of the racket. And by the way, Keating, I'm leaving tomorrow for a week. Orloff will have charge of Miss Weston. I think he'll be glad to have you look in on her occasionally. Is that agreeable, Orloff?"

"Quite so, sir," consented Orloff, grinning. "He would, anyhow, and he may as well have some authority for it."

Jim was embarrassed. "I hope," he said, "that too much may not be taken for granted concerning my friendship for Miss Weston. She would be offended if anybody implied that we were more than mere acquaintances. I never saw her but once before tonight."

"Well," sighed Orloff, "some people do accomplish a lot in a short time. Take me, for example—"

"Nobody'll ever take you, Fatty," growled Keating, "certainly not as an example."

"Nice work," approved Spellman, "and jolly well deserved... Now, you two little playmates are to see that Miss Weston has enough attention but no excitement. I want her kept quiet."

Jim was resolved to obey this injunction to the letter; and when the nurse met him at the door the next morning and whispered, "She's drowsy," he decided not to make his presence known.

"Doctor Orloff has been in?" he asked. When the nurse replied affirmatively, he said, "Then I'll not disturb Miss Weston.

"Who is that?" inquired Patricia, rousing from her apathy.

"One of the doctors from the other wing. Doctor Keating."

Jim crossed the room and took Patricia's hand, She seemed puzzled; then drew a slow smile.

"It's funny," she said unsteadily. "So much happened yesterday, and last night I dreamed such a lot of things. They're all jumbled—the things that happened and the ones I dreamed. You were mixed up in it, somehow—now you're here."

"I was happy to find you, Patricia. I've hunted for you everywhere."

"How is the pen?"

Jim grinned boyishly and confessed,

"I had to exchange it. Now, you mustn't talk any more."

"Ever?" The lips smiled faintly.

"You're improving rapidly, Patricia."

She sighed deeply. Jim's pressure tightened on her hand.

"Why are you calling me Patricia?" she asked, as from a dream.

"Shouldn't I?" he queried gently.

There was no audible reply, but the slim white fingers responded slightly to the warm clasp of his hand. Keating's heart speeded. But Patricia had drifted off to sleep.

IT was Christmas Eve. Everybody who could wangle it had gone.

Even the most exacting patients were requiring little attention,

for their families were visiting them, and their minds were

occupied.

Keating had made his rounds late in the afternoon; and at seven, having left word how he could be reached if necessary, he proceeded to Patricia's room.

The three days had wrought wonders for her. The fantastic dreams that had wearied her during the first forty-eight hours were no longer distressing her. And with the return to normal thinking, her emotional equipment had resumed its orderly processes. Patricia was still appreciative, still companionable, but thoroughly poised—and a bit reticent.

She had confided a little of her life story, not making a long saga of it, but telling Doctor Keating just enough to explain why she had no friends at this time of her serious need of them.

The brief chronicle had been offered, in response to Keating's encouragement, without the slightest trace of self-pity. Her father, Cyril Weston—Keating had recognized the name, though he knew very little about Gothic architecture or the contemporaries working in that field—had spent nine months out of twelve in Europe, returning annually to consult with members of his firm. Patricia and her mother rarely accompanied him on these trips, remaining in Switzerland, where Patricia was in school.

Then her mother had died; and Patricia, at seventeen, realizing the loneliness and restlessness of her artist-architect father, gave all her time to him.

"In many ways," she had explained, "Daddy was like a child. He had no talent for business. When we had money, we spent it. Between times, we tried to economize. One does not censure him for leaving nothing when he died. He was too good a poet to become a man of property."

And so—last June—returning to her native land in the hope of finding something to do, Patricia had been startled by the discovery that she was singularly unprepared to deal with the problem of work, She had had a liberal education, but she didn't know enough about any one thing to be qualified to teach. She had been away so long that nobody was interested in giving her a helping hand.

"I would have gone back to Europe," she said, "but there was probably even less chance than here."

That was all. She had found work in the department store. That had completed the story. She had told it simply, without seeming to realize that it was pathetic. Keating had been stirred to compassion, but he had tried to keep his pity out of his friendly queries. Pity wasn't good for people, he knew. An ounce of encouragement was worth a bucketful of pity. Nevertheless, he did pity her, and his wish to assume protection of her was almost too strong for further concealment.

It was seven o'clock now, and Patricia was expecting him, for he had told her what time he would be free. She was alone, for there was no longer need for special nurses on her case.

"Well," said Jim, exercising his professional right to lay his fingers on her wrist, "it's Christmas Eve."

"My first one without my father," she murmured.

He drew up a chair and sat down, close by her bedside.

"I've been thinking quite a little about Christmas, today," continued Patricia. "It's a sweet idea, of course, but I wonder if it's worth the bother and humiliation it brings to people who can't meet the obligations it imposes on them."

"You're right, I think," agreed Jim, "about the humiliations. They wouldn't have them, though, if they had all been dealing sincerely with their friends and families. It always seemed to me that if parents who were obliged to be frugal would let their children share in their problems—"

Patricia raised on one elbow, her eyes alight with a new idea. "Fine!" she exclaimed. "There ought to be an addition made to the commandment about honoring thy father and thy mother. The parents should also honor their children by confiding."

"Right—and letting the children help to bear family burdens in a sportsmanly manner. Perhaps a thoroughly honest Christmas, in which the children came forward to be loyal comrades, rather than self-piteous dependents, would make the old festival a red-letter day in their experience." Jim paused reflectively.

"Well," encouraged Patricia, "proceed, professor. You're doing well. And I can see you're not finished."

"I think that's about all I wanted to say," drawled Keating. "Besides, I haven't thought about it much. Christmas hasn't meant anything in particular to me—except a general upsetting of the usual program. But now that we're talking about it seriously, it occurs to me that the world couldn't possibly survive without Christmas."

HE sat for a long moment, trying to organize his thoughts. "I

mean it," he went on. "I'm not jesting. I doubt whether our

civilization could endure if it weren't for the general armistice

observed on Christmas."

"I'm afraid I don't understand," confessed Patricia. "Christmas 'armistice'?"

Jim folded his rangy arms on the edge of the bed and continued with his made-while-you-wait theory. "For at least a whole month, every year, all civilization has its attention captured by the coming of Christmas. Professional swashbucklers haven't the crust to yell for war while every decent person in the world is mellowed with the appeal to good will. Rumors of international jangles are pushed off the front page to make way for local stories of philanthropies. The poor have their innings. The rich abandon their arrogance.

"Patricia, if Christmas were uncelebrated for five years, the whole structure of human society would collapse! It takes just that much easement of the strain of greed and the tension of animosity to keep the old ship seaworthy."

"And all the presents—and Christmas cards," assisted Patricia. "I suppose they help, too."

"Unquestionably! Millions of people examine the lists of their old friends, and remember them, and prepare affectionate greetings for them. I dare say the bulk of these valuable friendships would be utterly lost if Christmas were omitted for a few years. For about a month most people are thinking more of their friends than of themselves. It takes their minds off their own troubles; makes them—at least temporarily—a little better than they are. It steadies 'em. We've thought about Christmas as a day—the twenty-fifth day of December. The fact is, Christmas is at least one-twelfth of the calendar year! We'd better hang on to it, if we know what's good for us."

Patricia regarded him teasingly. "You're funny," she said softly. "Fancy your making a speech in defense of Christmas. I always thought doctors were cynics."

"Doctors," said Keating slowly, "are constantly dealing with serious hurts. If they allowed themselves to be sentimental, they'd soon be a flock of lunatics. They have to brace themselves against tears and groans, and it makes them seem cold-blooded. But a man might really be as unemotional as an alligator and still understand the social value of an institution that humanizes the race."

Patricia nodded comprehendingly. "Thanks," she said quietly. "I wondered why you were saying all this about Christmas. I know now. You knew Christmas would be a hard day for me. And it would have been. I almost hated it. But tomorrow morning, when I wake up, I'll say, 'This is the most important day of the year. The world couldn't live without it.' That will help—a lot."

"Perhaps you'd better ask the nurse to hang up your stocking," suggested Jim.

"It wasn't like you to say that," she replied. "You know I haven't anybody."

"Perhaps you'd better ask the nurse to hang up your stocking,"

Doctor

Keating suggested. "But I haven't anyone to fill it," Patricia replied.

"I'll have a little gift for you, Patricia."

"Very well, then." She smiled, and added childishly, "We'll hang up the baby's stocking."

"It's time for you to go to sleep, now. I'll see you in the morning."

"Good night, Doctor Keating." She winked back the tears. "I've been selfish, thinking only about my own loneliness. It won't be a very pleasant day for you, either, looking after damaged people."

"Very appropriate way to spend the day, Patricia. I'm fortunate to have the opportunity, don't you think? I'll bet there are thousands of people who would envy me the chance I have to celebrate Christmas... I'll go now." He took her hand. "Don't forget about the stocking."

"Thank you, Doctor Keating. I'll remember."

He lingered, still holding her hand. She looked up inquiringly into his eyes. "I've been calling you 'Patricia,'" he said gently.

"I know. That was because I needed friendship—on Christmas. I'm glad you did."

"How about me? Think I could stand a little friendship, too—on Christmas?"

"You deserve it," she murmured. "I hope you have a Merry Christmas, Jim."

HOSPITAL nights are long. The first gray streak of dawn is

welcome. Patricia stirred, bewilderingly oriented herself to her

surroundings, remembered that the day would be Christmas, touched

the corners of her eyes with the rough fabric of her gown; then

brightened and smiled.

She reached out a hand to make sure she had not dreamed of telling the nurse to pin a stocking to the edge of her mattress. It was there, but it would be too soon to investigate. Jim would not have been here so early. Nevertheless, she slowly drew the silk through her fingers. There was a note in the toe. Turning on the table-lamp, Patricia read:

"Dearest, I have had no chance to buy you an appropriate souvenir of this Christmas Day—my happiest Christmas Day because I am under the same roof with you. The only gift I have to offer you—and this I do with all my love—is Jim Keating."

Patricia's eyes widened and a long intake of breath was articulated into an ecstatic "Oh-h-h-h!" She closed her eyes and touched the note tenderly with her lips. Her heart was racing. For a long time she lay quietly, trying to persuade herself that this was a reality. Her dreams for the past few days had been so vivid. Perhaps this, too, was a dream. She raised up on her elbow and reread the note. There was no mistake. It was Jim's penmanship. And how like him to have said it in a note. That was the way their friendship had begun—writing notes to each other.

PATRICIA reached to the bedside table for her pen, smoothed

out the note, and under Jim's message she wrote: "Ever

yours—Patricia."

Then she slipped the note into the open throat of her gown and laid it against her heart. How dear of Jim to have come to her room while she slept. He must have done it very quietly. Patricia's brows contracted. How little Jim knew of her. Did he really love her—or was it just a feeling of pity and a wish to protect her? He knew she was desperately lonely. And it was Christmas—and he thought something splendid should be done about it. He would offer her all he had—himself! Perhaps, under normal conditions, he might have deliberated the matter.

Presently the hospital began to come alive. It was broad daylight now. Somewhere in the building they were playing Christmas carols on a phonograph. The familiar melodies, so intimately associated with the happiest days of her girlhood, would have been almost unbearable but for the new comradeship that had driven Patricia's loneliness into eclipse.

The nurse breezed in, happily surprised to find her patient so alert. "Merry Christmas, Miss Weston!"

"Yes," replied Patricia radiantly, "it is! I hope you're finding it so, too."

"I believe Santa Claus must have put something in your stocking," teased the nurse. Her eyes roamed over the table, Patricia regarding her with quiet amusement. "I'll get you ready for your breakfast now," she said. "Doctor Orloff has left for the day. Doctor Keating will be looking after you. He has just phoned that he expects to be here early."

And so he was. Within a minute after the nurse had left the room, Patricia's door quietly opened and Keating entered. The ends of his stethoscope dangled from a bulging pocket. His hair was rumpled and he reeked of ether. Apparently his Christmas Day was already far advanced. Perhaps he hadn't been to bed at all, thought Patricia, with a poignant wave of sympathy.

She smiled up into his eyes as he took her hand, sobering gradually as he searched her face. He was wanting to know where he stood with her. His eyes were asking. She owed it to him, she felt, to caution him against the mistake of an act done on impulse. Now he was reading this caution in her brooding eyes and interpreting it as a refusal. A bit confused, Jim drew out his watch and automatically began a pulse count.

"Thanks, Jim, for the gift," said Patricia gently, "but—"

He silenced her, and continued counting. Then he returned the watch to his pocket and sighed.

"It's all right, Patricia. Doubtless there is somebody else. Maybe you couldn't have cared for me—that much—anyway. You needn't explain, dear. But I'm your doctor, today. Did you sleep well?"

Patricia nodded, regarding him with sober eyes. He touched her throat delicately with sensitive fingers.

"Tender?" he asked.

"Very," she replied—and drew a tremulous smile.

"You mean it hurts when I touch it?"

"No."

Jim thrust his hands into his coat pockets and stood for a minute considering the situation. Presently he gave up trying to solve the enigma and resumed his professional duties.

"Now I must listen to the heart, please," he announced, resolutely steadying his voice. The color slowly crept up Patricia's cheeks as he adjusted the stethoscope. Her eyes were closed, and her respirations came fast. Jim's eyes narrowed and were troubled.

"Something wrong?" asked Patricia. Jim straightened and removed the tubes from his ears. "You don't feel tight in there, do you?" he inquired anxiously, laying his hand on her chest. "It crackles like a rhonchus. You haven't been coughing, have you?"

"No," said Patricia, "I haven't, and I never heard of a rhonchus. Is this one?" she asked, bringing up his note.

His smile was that of the unexpectedly reprieved. He put his arms tenderly around her. "But Patricia—darling—I thought you said—"

"You didn't give me a chance to say anything! I wanted to be sure you weren't offering yourself to me because I was lonely—because you wanted to do something lovely for me on Christmas."

"You thought it—lovely?" he asked.

Patricia ventured to smooth his untidy hair with gentle fingers. "It was a sweet note, Jim," she murmured. "We always seem to be writing, don't we?" She laid the note against his cheek.

There was a silent moment. Then Jim took the note and read her message. His face was close to hers now. For a long moment they clung together.

Patricia's heart was pounding hard. "Jim, dear, they wanted me to avoid all excitement," she whispered.

"I know." He slowly released her.

For a moment they regarded each other with a tender smile. Jim toyed with the blue-black curls on her forehead.

"We belong to each other now. Don't we?" said Jim softly.

"Yes, dear."

There was another long silence.

"I don't believe it would hurt you," said Jim judicially, "if I kissed you—very, very gently."

Patricia smiled. "You ought to know," she murmured. "You're my doctor."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.