RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

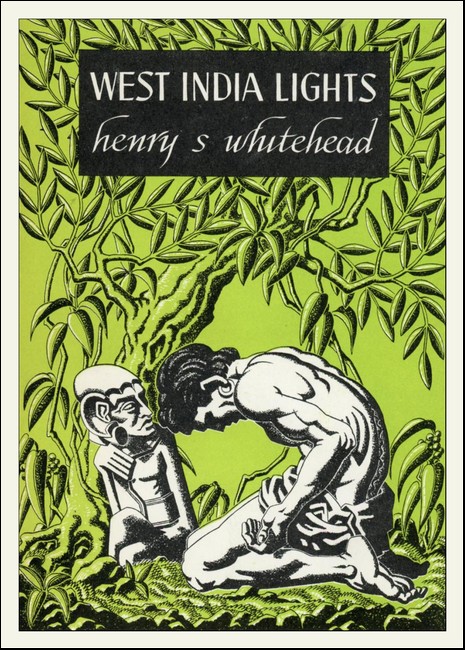

West India Lights, Arkham House, 1946, with "Williamson"

THE death of Mrs. Williamson Morley occurred in the early part of October, in San Francisco, only a couple of weeks before I was due to sail from New York for St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, my usual winter habitat. It was too far to get to the funeral, although, being an old friend and school mate of Morley's, I should have attended under any ordinary circumstances. I do not happen to know what the Morleys were doing in San Francisco. They lived in New York, and had a summer place on Long Island and I never knew Morley to move about very much. I wrote him at once, of course, a long and intimate letter. In it I suggested his coming down to stay with me in St. Thomas. I was there when I received his reply. He accepted, and said that he would be arriving about the middle of November and would cable me accordingly.

When he arrived he made quite a flutter among my negro house-servants; an impression, it seemed to me, that went much deeper, for some strange reason, than his five huge trunks of clothes would cause among such local dandies as my houseman, Stephen Penn. I am anything but "psychic," despite some experience with various out-of-the-way matters among the Caribbean Islands and in various parts of the globe. Indeed, one of my chief aversions is the use of this word by anyone as applying to one's own character. But, "psychic" or not, I could not help but feel that flutter, as I have called it. Mr. Williamson Morley made a very striking impression indeed. I mention it because it recalled to me something I had entirely dropped out of my mind in the year or more since I had seen Sylvia, Morley's late wife. My servants, very obviously, showed an immediate, and inexplicable dread of him. I cannot, honestly, use a less emphatic word. When you notice your cook making the sign of the cross upon herself when she lays rolling, anxious eyes upon your house-guest, observe an unmistakable grayish tinge replacing the shining brown of your houseman's "Zambo" cheeks as he furtively watches that guest at his morning setting-up exercises which Morley performed with vigor and gusto—when you notice things like this, you can hardly help wondering what it is all about, especially when you remember that the late wife of that house-guest was as unmistakably afraid of her genial husband!

I had never known Sylvia very well, but I had known her well enough to realize that during Williamson Morley's courtship there was no such element of fear in her reception of his advances preliminary to a marriage. I tried, when I did notice this thing, beginning not long after the wedding, not so much to explain it—I regarded it as inexplicable that anyone should have such feelings toward Morley whom I had known since we were small boys together in the same form at Berkeley School in New York City—as to classify it. I found that I could give it several names—dread, repulsion, even loathing.

It was too much for me. Williamson Morley inspiring any of these feelings, especially in the wife of his bosom! The thing, you see, was quite utterly ridiculous. There never was, there could not possibly be, a more kindly, normal, open-hearted and reasonable fellow than Morley himself. He was, and always had been, good-natured to the degree of a fault. He was the kind who would let anyone smack him in the face, and laugh at it, without even the thought of hitting back. He had always had a keen sense of humor. He was generous, and rich. He had inherited good-sized fortunes both from his father and mother, and had made a good deal more in his Wall Street office. Williamson Morley was what some people call "a catch," for any woman.

Knowing him as well as I did it seemed rather tough that his wife, whom he plainly loved, should take things the way she did. Morley never said anything about it, even to me. But I could see what certain novelists name "the look of pain in his eyes" more than once.

Morley's good-nature, more like that of a friendly big dog than anything else I could compare it to, was proverbial. His treatment of his wife, in the six or seven years of their married life, a good deal of which I saw with my own eyes, was precisely what anyone who knew him very well would expect of him. Sylvia had been a comparatively poor girl. Married to Morley, she had everything a very rich man's petted darling could possibly desire, Morley indulged her, lavished upon her innumerable possessions, kindnesses, privileges—

And yet, through it all there ran that unmistakable note of a strange unease, of a certain suggestion of dread in his presence on Sylvia's part.

I put it down to perverseness pure and simple after seeing it for the first year or so. I wasn't doing any guessing, you see, about Morley's "inside" treatment of his wife. There was no bluff about the fellow, nothing whatever in the way of deceit or double-mindedness. I have seen him look at her with an expression which almost brought the tears into my eyes—a compound expression mingled out of respect and devotion, and puzzlement and a kind of dogged undertone as though he were saying, mentally, "All right, my dear, I've done all I know how to make things go right and have you happy and contented, and I'm keeping it up indefinitely, hoping you'll see that I love you honestly, and would do anything in the world for you; and that I may find out what's wrong so that I can make it right."

THAT invincible good-nature I have spoken of, that easy-going way of slipping along through life letting people smack you and not smacking them back which was always characteristic of Williamson Morley, was, I should hasten to make clear, not in the slightest degree due to any lack of ability on Morley's part to take care of himself, physically or otherwise. Quite the contrary! Morley had been, by far, our best athlete in school days. He held the interscholastic record for the twelve-pound shot and the twelve-pound hammer, records which, I believe, still stand. He was slow and a trifle awkward on his feet, it is true, but as a boxer and wrestler he was simply invincible. Our school trainer, Ernie Hjertberg, told me that he was the best junior athlete he had ever handled, and Ernie had a long and reputable record.

Morley went on with this in college. In fact, he became a celebrity, what with his succession of record-breaking puts of the sixteen-pound shot, and his tremendous heaves of the hammer of the same weight. Those two events were firsts for Haverford whenever their star heavyweight competed during his four years at that institution. He quit boxing after he had nearly killed the Yale man who was heavyweight champ in Morley's Freshman year, in the first round. He was intercollegiate champion wrestler of all weights for three and one-half years. Watching him handle the best of them was like watching a mother put her baby to bed! Morley simply brushed aside all attempts to hammerlock or half-nelson him, took hold of his opponent, and put him on his back and held him there long enough to record the fall; and then got up with one of those deprecating smiles on his face as much as to say: "I hated to do that to you, old man—hope I didn't hurt you too much"

All through his athletic career at school, for the four years we were together there, he showed only one queer trait. That, under the circumstances, was a very striking one. Morley would never get under the showers. No. A dry-rub for him, every time. He was a hairy fellow, as many very powerfully-built men are, and I have seen him many a time, after some competition event or a strenuous workout at our athletic field or winter days in the gymnasium shining with honest sweat so that he might have been lacquered! Nevertheless, no shower for Morley! Never anything but four or five dry towels, then the usual muscle-kneading and alcohol rub afterwards—invariably with his track or gym shoes on. That, in its way, was another, and the last, of Morley's peculiarities. From first to last, he never, to my knowledge, took off even for muscle-kneadings at the capable hands of Black Joe, our rubber, the shoes he had been wearing, nor, of course, the heavy woolen stockings he always wore under them.

When quizzed about his dry-rubs, Morley always answered with his unfailing good-nature, that it was a principle with him. He believed in the dry-rub. He avoided difficulty and criticism in this strange idea of his, as it seemed to the rest of us, because Ernie Hjertberg, whose word was law and whose opinions were gold and jewels to us boys, backed him up in it. Many of the older athletes, said Ernie, preferred the dry-rub, and a generation ago nobody would have thought of taking a shower after competition or a workout. So it became a settled affair that Williamson Morley should dry-rub himself while the rest of us revelled under our cascades of alternate hot and cold water and were cool and comfortable while Morley at least looked half-cooked, red, and uncomfortable after his plain towellings!

It was, too, entirely clear to the rest of us that Morley's dry-rubs were taken on principle. That he was a bather—at home—was entirely evident. He was, besides being by long odds the best-dressed fellow in a very dressy, rather "fashionable" New York City school, the very pink and perfection of cleanliness. Indeed, if it had not been for Morley's admirable disposition, self-restraint, and magnificent muscular development and his outstanding athletic pre-eminence among us—our football teams with Morley in were simply invincible, and his inordinately long arms made him unbeatable at tennis—the school would very likely have considered him a "dude." A shot-putter, if it had been anybody else than Morley, who, however modestly, displays a fresh manicure twice a week at the group-critical age of fifteen or sixteen is—well, it was Morley, and whatever Morley chose to do among our crowd, or, indeed any group of his age in New York City in those days, was something that called for respectful imitation—not adverse criticism. Morley set the fashion for New York's foremost school for the four or five years that he and Gerald Canevin were buddies togther.

IT was when we were sixteen that the Morley divorce case shrieked from the front pages of the yellow newspapers for the five weeks of its lurid course in the courts.

During that period I, who had been a constant visitor at the house on Madison Avenue where Williamson, an only son, lived with his parents, by some tacit sense of the fitness of things, refrained from dropping in Saturdays or after school hours. Subsequently, Mrs. Morley, who had lost the case, removed to an apartment on Riverside Drive. Williamson accompanied his mother, and Mr. Morley continued to occupy the former home.

IT was a long time afterwards, a year or more, before Williamson talked of his family affairs with me. When he did begin it, it came with a rush, as though he had wanted to speak about it to a close friend for a long time and had been keeping away from the topic for decency's sake. I gathered from what he said that his mother was in no way to blame. This was not merely "chivalry" on Williamson's part. He spoke reticently, but with a strong conviction. His father, it seemed, had always, as long as he could remember, been rather "mean" to the kindest, most generous and whole-souled lady God had ever made. The attitude of Morley senior, as I gathered it, without, of course, hearing that gentleman's side of the affair, had always been distant and somewhat sarcastic, not only to Mrs. Morley but to Williamson as well. It was, Williamson said, as though his father had disliked him from birth, thought of him as a kind of inferior being! This had been shown, uniformly, by a general attitude of contemptuous indifference to both mother and son as far back as Williamson's recollection of his father took him.

It was, according to him, the more offensive and unjust on his father's part, because, not long before his own birth, his mother had undergone a more than ordinarily harrowing experience, which, Williamson and I agreed, should have made any man that called himself a man considerate to half the woman Mrs. Morley was, for the rest of his natural life!

THE couple had, it appeared, been married about five years at the time, were as yet childless, and were living on the Island of Barbados in the Lower Caribbean. Their house was an estate-house, "in the country," but quite close-in to the capital town, Bridgetown. Quite nearby, in the very next estate-house, in fact, was an eccentric old fellow, who was a retired animal collector. Mr. Burgess, the neighbor, had been in the employ for many years before his retirement due to a bad clawing he had received in the wilds of Nepaul, of the Hagenbecks and Wombwells.

Mr. Burgess's outstanding eccentricity was his devotion to "Billy," a full-grown orang-utan which, like the fellow in Kipling's horrible story, Bimi, he treated like a man, had it at the table with him, had taught the creature to smoke—all that sort of thing. The negroes for miles around were in a state of sustained terror, Williamson said.

In fact, the Bimi story was nearly re-enacted there in Barbados, only with a somewhat different slant. We boys at school read Kipling, and Sherlock Holmes, and Alfred Henry Lewis's Wolfville series those days, and Bimi was invoked as familiar to us both when Williamson told me what had happened.

It seems that the orang-utan and Mrs. Morley were great friends. Old Burgess didn't like that very well, and Douglas Morley, Williamson's father, made a terrific to-do about it. He finally absolutely forbade his wife to go within a hundred yards of Burgess's place unless for the purpose of driving past!

Mrs. Morley was a sensible woman. She listened to her husband's warnings about the treachery of the great apes, and the danger she subjected herself to in such matters as handing the orang-utan a cigarette, and willingly enough agreed to keep entirely away from their neighbor's place so long as the beast was maintained there at large and not, as Mr. Morley formally demanded of Burgess, shut up in an adequate cage. Mr. Morley even appealed to the law for the restraint of a dangerous wild beast, but could not, it appeared, secure the permanent caging of Burgess's strange pet.

Then, one night, coming home late from a Gentlemen's Party somewhere on the island, Mr. Morley had walked into his house and discovered his wife unconscious, lying on the floor of the dining-room, most of her clothing torn off her, and great weals and bruises all over her where the orang-utan had attacked her, sitting alone in a small living-room next the dining-room.

Mrs. Morley, hovering between life and death for days on end with a bad case of physiological shock, could give no account of what had occurred, beyond the startling apparition of "Billy" in the open doorway, and his leap towards her. She had mercifully lost consciousness, and it was a couple of weeks before she was able to do so much as speak.

Meanwhile Morley, losing no time, had dug out a couple of his negroes from the estate-village, furnished them with hurricane-lanterns for light on a black and starless night, and, taking down his Martini-Henry elephant gun, and charging the magazine with explosive bullets, had gone out after the orang-utan, and blown the creature, quite justifiably of course, into a mound of bloody pulp. He had, again almost justifiably, it seemed to Williamson and me, been restrained only by his two Blacks disarming him lest he be hung by the neck until dead, from disposing of his neighbor, Burgess, with the last of the explosive cartridges. As it was, although Morley was not a man of any great physical force, being slightly built and always in somewhat precarious health, he had administered a chastising with his two hands to the fatuous ex-wild animal collector, which was long remembered in His Majesty King Edward's loyal colony of Barbados, B.W.I.

IT was, as Williamson's maternal grandmother had confided to him, almost as though this horrible experience had unhinged Mr. Morley's mind. Williamson himself had been born within a year, and Douglas Morley, who had in the meantime sold out the sugar estates in which most of his own and his young wife's money had been invested, had removed to New York where he instituted a Bond Brokerage business. This Williamson had inherited two years after his graduation from college, at the time of his father's death at the rather premature age of forty-seven.

Douglas Morley, according to his grandmother's report and his own experience, had included his son in the strange attitude of dislike and contemptuous indifference which the devastating experience with the orang-utan had seemed to bring into existence.

We were not out of school when Mrs. Douglas Morley died, and Williamson went back to the Madison Avenue house to live with his father.

Mr. Morley had a kind of apartment built in for him, quite separate from his own part of the house. He could not, it seemed, bear to have Williamson under his eye, even though his plain duty and ordinary usage and custom made it incumbent on him to share his home with his son. The two of them saw each other as little as possible. Williamson had inherited his mother's property, and this his father administered for him as I must record to his credit, in an admirably competent and painstaking manner, so that Williamson was already a rich man well before his father's death about doubled his material possessions.

I HAVE gone into this detail largely because I want to accentuate how extremely regrettable, it seemed to me, was Sylvia's unaccountable attitude, which I have described, to one of the best and kindliest fellows on earth, after a childhood and youth such as he had been subjected to because of some obscure psychological slant of a very odd fish of a father for which, of course, he was in no way responsible himself.

Well, now Sylvia was gone, too, and Williamson Morley was once more alone in the world so far as the possession of near relatives went, and free to do about as he pleased.

His one comment, now that he was presumably settled down with me for the winter, about his late wife, I mean, was a very simple one, unconnected with anything that had been said or even alluded to, in answer to my carefully-phrased first personal word of regret for his loss.

"I did everything I knew how, Gerald."

There was a world of meaning, a résumé of quiet suffering, patiently and I am sure bravely, borne in those few and simple words so characteristic of Williamson Morley.

He did, once, refer to his mother during his visit with me, which lasted for several months. It was apropos of his asking my help in classifying and arranging a brief-case full of papers, legal and otherwise, which he had brought along, the documentation connected with a final settlement of his financial affairs. He had disposed of his bond-brokerage business immediately after his wife's death.

There were various family records—wills, and suchlike—among these papers, and I noted among these as I sorted and helped arrange them for Morley, sitting opposite him at the big table on my West gallery, the recurring names of various kinsfolk of his—Parkers, Morleys, Graves, Putneys—but a total absence of the family name Williamson. I had asked him, without any particular purpose, hardly even curiosity over so small a matter, whether there were not some Williamson relatives, that being his own baptismal name.

"That's a curious thing, Gerald," said Morley, reflectively, in his peculiarly deep and mellow voice. "My poor mother always—well, simply abominated the name. I suppose that's how come I got it fastened on me—because she disliked it! You see, when I was born—it was in New York, in Roosevelt Hospital—my mother very nearly died. She was not a very big or strong person, and I was—er—rather a good-sized baby—weighed seventeen pounds or something outrageous at birth! Queer thing too—I nearly passed out during the first few days myself, they say! Undernourished. Sounds ridiculous, doesn't it. Yet, that was the verdict of three of New York's foremost obstetricians who were in on the case in consultation.

"Well, it seems, when I was about ten days old, and out of danger, my father came around in his car—it was a Winton, I believe in those days or perhaps, a Panhard—and carted me off to be baptized. My mother was still in a dangerous condition—they didn't let her up for a couple of weeks or so after that—and chose that name for me himself, so "Williamson" I've been, ever since!"

WE had a really very pleasant time together. Morley was popular with the St. Thomas crowd from the very beginning. He was too sensible to mope, and while he didn't exactly rush after entertainment, we went out a good deal, and there is a good deal to go out to in St. Thomas, or was in those days, two years ago, before President Hoover's Economy Program took our Naval personnel out of St. Thomas.

Morley's geniality, his fund of stories, his generous attitude to life, the outstanding kindliness and fellowship of the man, brought him a host of new friends, most of whom were my old friends. I was delighted that my prescription for poor old Morley—getting him to come down and stay with me that winter—was working so splendidly.

IT was in company with no less than four of these new friends of Morley's, Naval Officers, all four of them, that he and I turned the corner around the Grand Hotel one morning about eleven o'clock and walked smack into trouble! The British sailorman of the Navy kind is, when normal, one of the most respectful and pleasant fellows alive. He is, as I have observed more than once, quite otherwise when drunk. The dozen or so British tars we encountered that moment, ashore from the Sloop-of-War Amphitrite, which lay in St. Thomas's Harbor, were as nasty and truculent a group of human-beings as I have ever had the misfortune to encounter. There is no telling where they had acquired their present condition of semi-drunkenness, but there was no question whatever of their joint mood!

"Ho—plasterin' band o' brass-hat——!" greeted the enormous Cockney who seemed to be their natural leader, eyeing truculently the four white-drill tropical uniforms with their shoulder insignia, and rudely jostling Lieutenant Sankers, to whose house we were en route afoot that morning, "fink ye owns the 'ole brasted universe, ye does. I'll show ye!" and with that, the enormous bully, abetted by the salient jeers of his following which had, somehow, managed to elude their ship's Shore Police down to that moment, barged head first into Morley, seizing him first by both arms and leaving the soil-marks of a pair of very dirty hands on his immaculate white drill jacket. Then, as Morley quietly twisted himself loose without raising a hand against this attack, the big Cockney swung an open hand, and landed a resounding slap across Morley's face.

This whole affair, of course, occupied no more than a few seconds. But I had time, and to spare, to note the red flush of a sudden, and I thought an unprecedented, anger in Morley's face; to observe the quick tightening of his tremendous muscles, the abrupt tensing of his long right arm, the beautifully-kept hand on the end of it hardening before my eyes into a great, menacing fist; the sudden glint in his deep-set dark-brown eyes, and then—then—I could hardly believe the evidence of my own two eyes—Williamson Morley, on his rather broad pair of feet, was trotting away, leaving his antagonist who had struck him in the face; leaving the rest of us together there in a tight little knot and an extremely unpleasant position on that corner. And then—well, the crisp "quarter-deck" tones of Commander Anderson cut through that second's amazed silence which had fallen. Anderson had seized the psychological moment to turn-to these discipline-forgetting tars. He blistered them in a cutting vernacular in no way inferior to their own. He keel-hauled them, warming to his task.

Anderson had them standing at attention, several gaping-mouthed at his extraordinary skill in vituperation, by the time their double Shore Police squad came around the corner with truncheons in hand; and to the tender mercies of that businesslike and strictly sober group we left them.

We walked along in a complete silence, Morley's conduct as plainly dominating everything else in all our minds, as though we were five sandwich-men with his inexcusable cowardice blazoned on our fore-and-aft signboards.

We found him at the foot of the flight of curving steps with its really beautiful metal-wrought railing which leads up to the high entrance of Lieutenant Sankers's house. We went up the steps and into the house together, and when we had taken off our hats and gone into the "hall," or living room, there fell upon us a silence so awkward as to transcend anything else of the kind in my experience. I, for one, could not speak to save my life; could not, it seemed, so much as look at Morley. There was, too, running through my head a half-whispered bit of thick, native, negro, St. Thomian speech, a dialect remark, made to herself, by an aged negress who had been standing, horrified, quite nearby, and who had witnessed our besetting and the fiasco of Morley's ignominious retreat after being struck full in the face. The old woman had muttered: "Him actin' foo save him own soul, de mahn—Gahd keep de mahn stedfas'!"

And, as we stood there, and the piling-up silence was becoming simply unbearable, Morley, who quite certainly had not heard this comment of the pious old woman's, proceeded, calmly, in that mellow, deep baritone voice of his, to make a statement precisely bearing out the old woman's contention.

"You fellows are wondering at me, naturally. I'm not sure that even Canevin understands! You see, I've allowed myself to get really angry three times in my life, and the last time I took a resolution that nothing, nothing whatever, nothing conceivable, would ever do it to me again! I remembered barely in time this morning, gentlemen. The last time, you see, it cost me three weeks of suspense, nearly ruined me, waiting for a roughneck I had struck to die or recover—compound fracture—and I only tapped him, I thought! Look here!" as, looking about him, he saw a certain corporate lack of understanding on the five faces of his audience.

And, reaching up one of those inordinately long arms of his to where hung an old wrought-iron-barrelled musket, obviously an "ornament" in Sankers's house, hired furnished, he took the thing down, and with no apparent effort at all, in his two hands, broke the stock away from the lock and barrel, and then, still merely with his hands, not using a knee for any pressure between them such as would be the obvious and natural method for any such feat attempted, with one sweep bent the heavy barrel into a right-angle.

He stood there, holding the strange-looking thing that resulted for us to look at, and then as we stood, speechless, fascinated, with another motion of his hands, and putting forth some effort this time—a Herculean heave which made the veins of his forehead stand out abruptly and the sweat start up on his face on which the mark of the big Cockney's hand now showed a bright crimson, Williamson Morley bent the gun-barrel back again into an approximate trueness and laid it down on Sankers' hall table.

"It's better the way it is, don't you think?" he remarked, quietly, dusting his hands together, "rather than, probably to have killed that mucker out of Limehouse—maybe two or three of them, if they'd pitched in to help him." Then, in a somewhat altered tone, a faintly perceptible trace of vehemence present in it, he added: "I think you should agree with me, gentlemen!"

I think we were all too stultified at the incredible feat of brute strength we had just witnessed to get our minds very quickly off that. Sankers, our host for the time-being, came-to the quickest.

"Good God!" he cried out, "of course—rather—Oh, very much so, Old Man! Good God!—Mere bones and Cockney meat under those hands!"

And then the rest of them chimed in. It was a complete, almost a painful revulsion on the part of all of them. I, who had known Morley most of my life, had caught his point almost, as it happened, before he had begun to demonstrate it; about the time he had reached up after the old musket on the wall. I merely caught his eye and winked, aligning myself with him as against any possible adverse conclusion of the others.

THIS, of course, in the form of a choice story, was all over St. Thomas, Black, White, and "Coloured" St. Thomas, within twenty-four hours, and people along the streets began to turn their heads to look after him, as the negroes had done since his arrival, whenever Morley passed among them.

I could hardly fail to catch the way in which my own household reacted to this new information about the physical strength of the stranger within its gates so soon as the grapevine route had apprized its dark-skinned members of the fact. Stephen Penn, the houseman, almost never looked at Morley now, except by the method known among West Indian negroes as "cutting his eyes," which means a sidewise glance. Esmerelda, my extremely pious cook, appeared to add to the volume of her crooned hymn-tunes and frequently-muttered prayers with which she accompanied her work. And once when my washer's pick'ny glimpsed him walking across the stone-flagged yard to the side entrance to the West gallery, that coal-black child's single garment lay stiff against the breeze generated by his flight towards the kitchen door and safety!

IT was Esmerelda the cook who really brought about the set of conditions which solved the joint mysteries of Morley's father's attitude to him, his late wife's obvious feeling of dread, and the uniform reaction of every St. Thomas negro whom I had seen in contact with Morley. The dénouement happened not very long after Morley's demonstration in Lieutenant Sankers's house that morning of our encounter with the sailors.

Esmerelda had been trying-out coconut oil, a process, as performed in the West Indies, involving the boiling of a huge kettle of water. This, arranged outdoors, and watchfully presided over by my cook, had been going on for a couple of days at intervals. Into the boiling water Esmerelda would throw several panfuls of copra, the white meat dug out of the matured nuts. After the oil had been boiled out and when it was floating, this crude product would be skimmed off, and more copra put into the pot. The final process was managed indoors, with a much smaller kettle, in which the skimmed oil was "boiled down" in a local refining process.

It was during this final stage in her preparation of the oil for the household that old Esmerelda, in some fashion of which I never, really heard the full account, permitted the oil to get on fire, and, in her endeavors to put out the blaze, got her dress afire. Her loud shrieks which expressed fright rather than pain, for the blazing oil did not actually reach the old soul's skin, brought Morley, who was alone at the moment on the gallery reading, around the house and to the kitchen door on the dead run. He visualized at once what had happened, and, seizing an old rag-work floor mat which Esmerelda kept near the doorway, advanced upon her to put out the fire.

At this she shrieked afresh, but Morley, not having the slightest idea that his abrupt answer to her yells for help had served to frighten the old woman almost into a fit, merely wrapped the floor-mat about her and smothered the flames. He got both hands badly burned in the process and Dr Pelletier dressed them with an immersion in more coconut oil and did them up in a pair of bandages about rubber tissue to keep them moist with the oil dressing inside, so that Morley's hands looked like a prize-fighter's with the gloves on. These pudding-like arrangements Dr Pelletier adjured his patient to leave on for at least forty-eight hours.

We drove home and I declined a dinner engagement for the next evening for Morley on the ground that he could not feed himself! He managed a bowl of soup between his hands at home that evening, and as he had a couple of fingers free outside the bandage on his left hand, assured me that he could manage undressing quite easily. I forgot all about his probable problem that evening, and did not go to his room to give him a hand as I had fully intended doing.

It was not until the next day at lunch that it dawned on me that Morley was fully dressed, although wearing pumps into which he could slip his feet, instead of shoes, and wondering how he had managed it. There were certain details, occurring to me, as quite out of the question for a man with hands muffled up all but the two outside fingers on the left hand as Morley was. Morley's tie was knotted with his usual careful precision; his hair, as always, was brushed with a meticulous exactitude. His belt-buckle was fastened.

I tried to imagine myself attending to all these details of dress with both thumbs and six of my eight fingers out of commission. I could not. It was too much for me.

I said nothing to Morley, but after lunch I asked Stephen Penn if he had assisted Mr. Morley to dress.

Stephen said he had not. He had offered to do so, but Mr. Morley had thanked him and replied it wasn't going to be necessary.

I was mystified.

The thing would not leave my mind all that afternoon while Morley sat out there on the West gallery with the bulk of the house between himself and the sun and read various magazines. I went out at last merely to watch him turn the pages. He managed that very easily, holding the magazine across his right forearm and grasping the upper, right-hand corner of a finished page between the two free fingers and the bandage itself whenever it became necessary to turn it over.

That comparatively simple affair, I saw, was no criterion.

The thing got to "worrying" me. I waited, biding my time.

About ten minutes before dinner, carrying the silver swizzel-tray, with a clinking jug and a pair of tall, thin glasses, I proceeded to the door of Morley's room, tapped, rather awkwardly turned the door's handle, my other hand balancing the tray momentarily, and walked in on him. I had expected, you see, to catch him in the midst of dressing for dinner.

I caught him.

He was fully dressed, except for putting on his dinner jacket. He wore a silk soft shirt and his black tie was knotted beautifully, all his clothes adjusted with his accustomed careful attention to the detail of their precise fit.

I have said he was fully dressed, save for the jacket. Dressed, yes, but not shod. His black silk socks and the shining patent-leather pumps which would go on over them lay on the floor beside him, where he sat, in front of his bureau mirror, at the moment of my entrance brushing his ruddy-brown, rather coarse, but highly decorative hair with a pair of ebony-backed military brushes. Morley's hair had always been perhaps the best item of his general appearance. It was a magnificent crop, and of a sufficiently odd color to make it striking to look at without being grotesque or even especially conspicuous. Morley had managed a fine parting this evening in the usual place, a trifle to the right of the centre of his forehead. He was smoothing it down now, with the big, black-backed brushes with the long bristles, sitting, so to speak, on the small of his back in the chair.

With those pumps and socks not yet put on I saw Morley's feet for the first time in my life.

And seeing them I understood those dry rubs in the gymnasium when we were schoolboys together—that curious peculiarity of Morley's which caused him to take his rubs with his track shoes on! "Curious peculiarity," I have said. The phrase is fairly accurate, descriptive, I should be inclined to think, of those feet—feet with well-developed thumbs, like huge, broad hands—feet which he had left to clothe this evening until the last end of his dressing for dinner, because—well, because he had been using them to fasten his shirt at the neck, and tie that exquisite knot in his evening bow. He was using them now, in fact, as I looked dumbfounded, at him, to hold the big military brushes with which he was arranging that striking hair of his.

He caught me, of course, my entrance with the tray—which I managed not to drop—and at first he looked annoyed, and then, true to his lifelong form, Williamson Morley grinned at me in the looking-glass.

"O—good!" said he. "That's great, Gerald. But, Old Man, I think I'll ask you to hold my glass for me, if you please. Brushing one's hair, you see—er—this way, is one thing. Taking a cocktail is, really, quite another."

And then, quite suddenly, it dawned upon me, and very nearly made me drop that tray after all, why Morley's father had named him "Williamson."

I set the tray down, very carefully, avoiding Morley's embarrassed eyes, feeling abysmally ashamed of myself for what I, his host, had done—nothing, of course, farther from my mind than that I should run into any such oddment as this. I poured out the glasses. I wiped off a few drops I had spilled on the top of the table where I had set the tray. All this occupied some little time, and all through it I did not once glance in Morley's direction.

And when I did, at last, carry his glass over to him, and, looking at him, I am sure, with something like shame in my eyes wished him "Good Health" after our West Indian fashion of taking a drink; Morley needed my hand with his glass in it at his mouth, for the black silk socks and the shining, patent-leather pumps were on his feet now, and the slight flush of his embarrassment had faded entirely from his honest, good-natured face.

And, I thought down inside me, that, whatever his motive in his unique chagrin, Douglas Morley had honored him by naming him "Williamson!" For Williamson Morley, as I had never doubted, and doubted just at that moment rather less than ever before, was a better man than his father—whichever way you care to take it.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.