RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

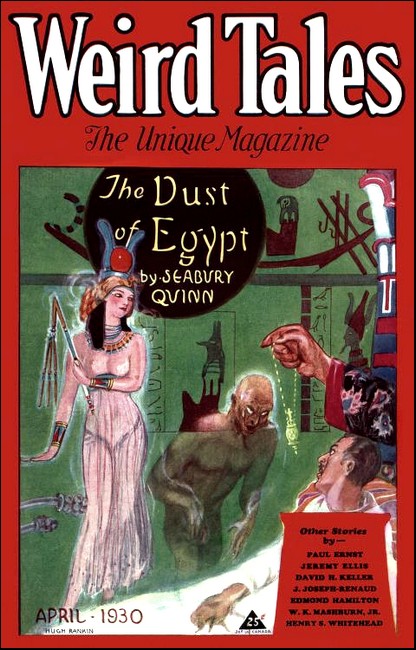

Weird Tales, April 1930, with "The Shut Room"

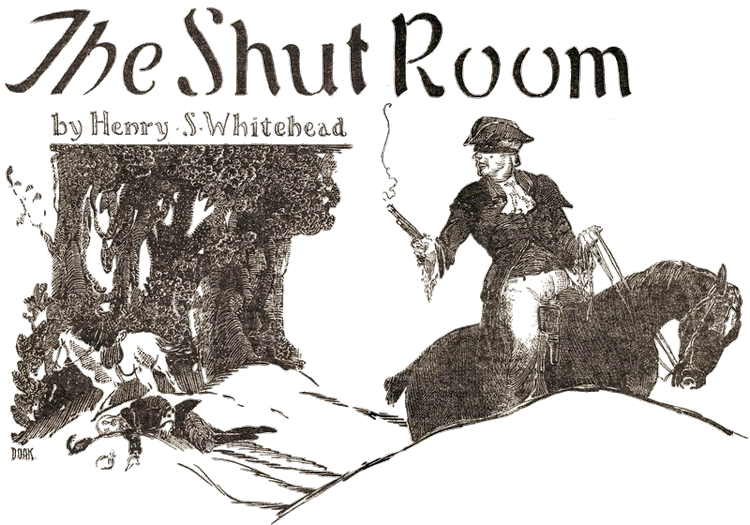

"The dead body of Sir William Greaves lay beside

the highroad, an ounce ball through hist heart."

Every manifestation took place in "The Coach and Horses" inn

where the English highwayman had been caught red-handed.

IT was Sunday morning and I was coming out of All Saints' Church, Margaret Street, along with the other members of the hushed and reverent congregation, when, near the entrance doors, a hand fell lightly on my shoulder. Turning, I perceived that it was the Earl of Carruth. I nodded, without speaking, for there is that in the atmosphere of this great church, especially after one of its magnificent services and heart-searching sermons, which precludes anything like the hum of conversation which one meets with in many places of worship.

In these worldly and 'scientific' days it is unusual to meet with a person of Lord Carruth's intellectual and scientific attainments who troubles very much about religion. As for me, Gerald Canevin, I have always been a church-going fellow.

Carruth accompanied me in silence through the entrance doors and out into Margaret Street. Then, linking his arm in mine, he guided me, still in silence, to where his Rolls-Royce car stood at the curbstone.

'Have you any luncheon engagement, Mr. Canevin?' he inquired, when we were just beside the car, the footman holding the door open.

'None whatever,' I replied.

'Then do me the pleasure of lunching with me,' invited Carruth.

'I was planning on driving from church to your rooms,' he explained, as soon as we were seated and the car whirling us noiselessly toward his town house in Mayfair. 'A rather extraordinary matter has come up, and Sir John has asked me to look into it. Should you care to hear about it?'

'Delighted,' I acquiesced, and settled myself to listen.

To my surprise, Lord Carruth began reciting a portion of the Nicene Creed, to which, sung very beautifully by All Saints' choir, we had recently been listening.

'Maker of Heaven and earth,' quoted Carruth, musingly, 'and of all things—visible and invisible.' I started forward in my seat. He had given a peculiar emphasis to the last word, 'invisible.'

'A fact,' I ejaculated, 'constantly forgotten by the critics of religion! The Church has always recognized the existence of the invisible creation.'

'Right, Mr. Canevin. And—this invisible creation; it doesn't mean merely angels!'

'No one who has lived in the West Indies can doubt that,' I replied.

'Nor in India,' countered Carruth. 'The fact—that the Creed attributes to God the authorship of an invisible creation—is an interesting commentary on the much-quoted remark of Hamlet to Horatio: "There are more things in Heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy." Apparently, Horatio's philosophy, like that of the present day, took little account of the spiritual side of affairs; left out God and what He had made. Perhaps Horatio had recited the creed a thousand times, and never realized what that clause implies!'

'I have thought of it often, myself,' said I. 'And now—I am all curiosity—what, please, is the application?'

'It is an ocurrence in one of the old coaching inns,' began Carruth, 'on the Brighton Road; a very curious matter. It appears that the proprietor—a gentleman, by the way, Mr. William Snow, purchased the inn for an investment just after the Armistice—has been having a rather unpleasant time of it. It has to do with shoes!'

'Shoes?' I inquired; 'shoes!' It seemed an abrupt transition from the Nicene Creed to shoes!

'Yes,' replied Carruth, 'and not only shoes but all sorts of leather affairs. In fact, the last and chief difficulty was about the disappearance of a commercial traveler's leather sample-case. But I perceive we are arriving home. We can continue the account at luncheon.'

During lunch he gave me a rather full account, with details, of what had happened at 'The Coach and Horses' Inn on the Brighton Road, an account which I will briefly summarize as follows.

SNOW, the proprietor, had bought the old inn partly for business reasons, partly for sentimental. It had been a portion, up to about a century before, of his family's landed property. He had repaired and enlarged it, modernized it in some ways, and in general restored a much rundown institution, making 'The Coach and Horses' into a paying investment. He had retained, so far as possible, the antique architectural features of the old coaching inn, and before very long had built up a motor clientèle of large proportions by sound and careful management.

Everything, in fact, had prospered with the gentleman-innkeeper's affairs until there began, some four months back, a series of unaccountable disappearances. The objects which had, as it were, vanished into thin air, were all—and this seemed to me the most curious and bizarre feature of Carruth's recital—leather articles. Pair after pair of shoes or boots, left outside bedroom doors at night, would be gone the next morning. Naturally the 'boots' was suspected of theft. But the 'boots' had been able to prove his innocence easily enough. He was, it seemed, a rather intelligent broken-down jockey, of a keen wit. He had assured Mr. Snow of his surprise as well as of his innocence, and suggested that he take a week's holiday to visit his aged mother in Kent and that a substitute 'boots,' chosen by the proprietor, should take his place. Snow had acquiesced, and the disappearance of guests' footwear had continued, to the consternation of the substitute, a total stranger, obtained from a London agency.

That exonerated Billings, the jockey, who came back to his duties at the end of his holiday with his character as an honest servant intact. Moreover, the disappearances had not been confined to boots and shoes. Pocketbooks, leather luggage, bags, cigarette cases—all sorts of leather articles went the way of the earlier boots and shoes, and besides the expense and annoyance of replacing these, Mr. Snow began to be seriously concerned about the reputation of his house. An inn in which one's leather belongings are known to be unsafe would not be a very strong financial asset. The matter had come to a head through the disappearance of the commercial traveler's sample-case, as noted by Carruth in his first brief account of this mystery. The main difficulty in this affair was that the traveler had been a salesman of jewelry, and Snow had been confronted with a bill for several hundred pounds, which he had felt constrained to pay. After that he had laid the mysterious matter before Sir John Scott, head of Scotland Yard, and Scott had called in Carruth because he recognized in Snow's story certain elements which caused him to believe this was no case for mere criminal investigation.

After lunch Carruth ordered the car again, and, after stopping at my rooms for some additional clothing and the other necessities for an overnight visit, we started along the Brighton Road for the scene of the difficulty.

WE arrived about four that Sunday afternoon, and immediately went into conference with the proprietor.

Mr. William Snow was a youngish middle-aged gentleman, very well dressed, and obviously a person of intelligence and natural attainments. He gave us all the information possible, repeating, with many details, the matters which I have already summarized, while we listened in silence. When he had finished: 'I should like to ask some questions,' said Carruth.

'I am prepared to answer anything you wish to enquire about,' Mr. Snow assured us.

'Well, then, about the sentimental element in your purchase of the inn, Mr. Snow—tell us, if you please, what you may know of the more ancient history of this old hostelry. I have no doubt there is history connected with it, situated where it is. Undoubtedly, in the coaching days of the Four Georges, it must have been the scene of many notable gatherings.'

'You are right, Lord Carruth. As you know, it was a portion of the property of my family. All the old registers are intact, and are at your disposal. It is an inn of very ancient foundation. It was, indeed, old in those days of the Four Georges, to whom you refer. The records go back well into the Sixteenth Century, in fact; and there was an inn here even before registers were kept. They are of comparatively modern origin, you know. Your ancient landlord kept, I imagine, only his "reckoning;" he was not concerned with records; even licenses are comparatively modern, you know.'

The registers were produced, a set of bulky, dry-smelling, calf-bound volumes. There were eight of them. Carruth and I looked at each other with a mutual shrug.

'I suggest,' said I, after a slight pause, 'that perhaps you, Mr. Snow, may already be familiar with the contents of these. I should imagine it might require a week or two of pretty steady application even to go through them cursorily.'

Mr. William Snow smiled. 'I was about to offer to mention the high points,' said he. 'I have made a careful study of these old volumes, and I can undoubtedly save you both a great deal of reading. The difficulty is—what shall I tell you? If only I knew what to put my finger upon—but I do not, you see!'

'Perhaps we can manage that,' threw in Carruth, 'but first, may we not have Billings in and question him?'

The former jockey, now the boots at 'The Coach and Horses,' was summoned and proved to be a wizened, copper-faced individual, with a keen eye and a deferential manner. Carruth invited him to a seat and he sat, gingerly, on the very edge of a chair while we talked with him. I will make so attempt to reproduce his accent, which is quite beyond me. His account was somewhat as follows, omitting the questions asked him both by Carruth and myself.

'At first it was only boots and shoes. Then other things began to go. The things always disappeared at night. Nothing ever disappeared before midnight, because I've sat up and watched many's the time. Yes, we tried everything: watching, even tying up leather things, traps! Yes, sir—steel traps, baited with a boot! Twice we did that. Both times the boot was gone in the morning, the trap not even sprung. No, sir—no one possibly among the servants. Yet, an "inside" job; it couldn't have been otherwise. From all over the house, yes. My old riding-boots—two pairs—gone completely; not a trace; right out of my room. That was when I was down in Kent as Mr. Snow's told you, gentlemen. The man who took my place slept in my room, left the door open one night—boots gone in the morning, right under his nose.

'Seen anything? Well, sir, in a manner, yes—in a manner, no! To be precise, no. I can't say that I ever saw anything, that is, anybody; no, nor any apparatus as you might say, in a manner of speaking—no hooks no strings, nothing used to take hold of the things—but—' Here Billings hesitated, glanced at his employer, looked down at his feet, and his coppery face turned a shade redder.

'Gentlemen,' said he, as though coming to a resolution, 'I can only tell you the God's truth about it. You may think me barmy—shouldn't blame you if you did! But—I'm as much interested in this 'ere thing as Mr. Snow 'imself, barrin' that I 'aven't had to pay the score—make up the value of the things, I mean, as 'e 'as. I'll tell you—so 'elp me Gawd, gentlemen, it's a fact—I 'ave seen something, absurd as it'll seem to you. I've seen—'

Billings hesitated once more, dropped his eyes, looked distressed, glanced at all of us in the most shamefaced, deprecating manner imaginable, twiddled his hands together, looked, in short, as though he were about to own up to it that he was, after all, responsible for the mysterious disappearances; then finally said: 'I've seen things disappear—through the air! Now—it's hout! But it's a fact, gentlemen all—so 'elp me, it's the truth. Through the air, just as if someone were carrying them away—someone invisible I mean, in a manner of speaking—bloomin' pair of boots, swingin' along through the bloomin' air—enough to make a man say 'is prayers, for a fact!'

It took considerable assuring on the part of Carruth and myself to convince the man Billings that neither of us regarded him as demented, or, as he pithily expressed it, 'barmy.' We assured him, while our host sat looking at his servant with a slightly puzzled frown, that, on the contrary, we believed him implicitly, and furthermore that we regarded his statement as distinctly helpful. Mr. Snow, obviously convinced that something in his diminutive servitor's mental works was unhinged, almost demurred to our request that we go, forthwith, and examine the place in the hotel where Billings alleged his marvel to have occurred.

WE were conducted up two flights of winding steps to the story which had, in the inn's older days, plainly been an attic. There, Billings indicated, was the scene of the disappearance of the 'bloomin' boot, swingin' along—unaccompanied—through the bloomin' air.'

It was a sunny corridor, lighted by the spring sunlight through several quaint, old-fashioned, mullioned windows. Billings showed us where he had sat, on a stool in the corridor, watching; indicated the location of the boots, outside a doorway of one of the less expensive guest-rooms; traced for us the route taken by the disappearing boots.

This route led us around a corner of the corridor, a corner which, the honest 'boots' assured us, he had been 'too frightened' to negotiate on the dark night of the alleged marvel.

But we went around it, and there, in a small, right-angled hallway, it became at once apparent to us that the boots on that occasion must have gone through one of two doorways, opposite each other at either side, or else vanished into thin air.

Mr. Snow, in answer to our remarks on this subject, threw open the door at the right. It led into a small but sunny and very comfortable-looking bedchamber, shining with honest cleanliness and decorated tastefully with chintz curtains with valances, and containing several articles of pleasant, antique furniture. This room, as the repository of air-traveling boots, seemed unpromising. We looked in in silence.

'And what is on the other side of this short corridor?' I enquired.

'The "shut room,"' replied Mr. William Snow.

Carruth and I looked at each other.

'Explain, please,' said Carruth.

'It is merely a room which has been kept shut, except for an occasional cleaning,' replied our host, readily, 'for more than a century. There was, as a matter of fact, a murder committed in it in the year 1818, and it was, thereafter, disused. When I purchased the inn, I kept it shut, partly, I dare say, for sentimental reasons; partly, perhaps, because it seemed to me a kind of asset for an ancient hostelry. It has been known as "the shut room" for more than a hundred years. There was, otherwise, no reason why I should not have put the room in use. I am not in the least superstitious.'

'When was the room last opened?' I enquired.

'It was cleaned about ten days ago, I believe,' answered Mr. Snow.

'May we examine it?' asked Carruth.

'Certainly,' agreed Snow, and forthwith sent Billings after the key.

'And may we hear the story—if you know the details—of the murder to which you referred?' Carruth asked.

'Certainly,' said Snow, again. 'But it is a long and rather complicated story. Perhaps it would do better during dinner.'

In this decision we acquiesced, and, Billings returning with the key, Snow unlocked the door and we looked into 'the shut room.' It was quite empty, and the blinds were drawn down over the two windows. Carruth raised these, letting in a flood of sunlight. The room was utterly characterless to all appearance, but—I confess to a certain 'sensitivity' in such matters—I 'felt' something like a faint, ominous chill. It was not, as the word I have used suggests, anything like physical cold. It was, so to express it, mentally cold. I despair of expressing what I mean more clearly. We looked over the entire room, an easy task as there was absolutely nothing to attract the eye. Both windows were in the wall at our right hand as we entered, and, save for the entrance door through which we had just come, the other three walls were quite blank.

Carruth stepped halfway out through the doorway and looked at the width of the wall in which the door was set. It was, perhaps, ten inches thick. He came back into the room, measured with his glance the distance from window-wall to the blank wall opposite the windows, again stepped outside, into the passageway this time, and along it until he came to the place where the short passage turned into the longer corridor from which we had entered it. He turned to his right this time, I following him curiously, that is, in the direction opposite that from which we had walked along the corridor, and tapped lightly on the wall there.

'About the same thickness, what?' he enquired of Snow.

'I believe so,' came the answer. 'We can easily measure it.'

'No, it will not be necessary, I think. We know that it is approximately the same.' Carruth ceased speaking and we followed him back into the room once more. He walked straight across it, rapped on the wall opposite the doorway.

'And how thick is this wall?' he enquired.

'It is impossible to say,' replied Snow, looking slightly mystified. 'You see, there are no rooms on that side, only the outer wall, and no window through which we could easily estimate the thickness. I suppose it is the same as the others, about ten inches I'd imagine.'

Carruth nodded, and led the way out into the hallway once more. Snow looked enquiringly at Carruth, then at me.

'It may as well be locked again,' offered Carruth, 'but—I'd be grateful if you'd allow me to keep the key until tomorrow.'

Snow handed him the key without comment, but a slight look of puzzlement was on his face as he did so. Carruth offered no comment, and I thought it wise to defer the question which was on my lips until later when we were alone. We started down the long corridor toward the staircase, Billings touching his forehead and stepping on ahead of us and disappearing rapidly down the stairs, doubtless to his interrupted duties in the scullery.

'It is time to think of which rooms you would prefer,' suggested our pleasant-voiced host as we neared the stairs. 'Suppose I show you some which are not occupied, and you may, of course, choose what suit you best.'

'On this floor, if you please,' said Carruth, positively.

'As you wish, of course,' agreed Snow, 'but, the better rooms are on the floor below. Would you not, perhaps, prefer—'

'Thank you no,' answered Carruth. 'We shall prefer to be up here if we may, and—if convenient—a large room with two beds.'

'That can be managed very easily,' agreed Snow. He stepped back a few paces along the corridor, and opened a door. A handsome, large room, very comfortably and well furnished, came to our view. Its excellence spoke well for the management of The Coach and Horses. The 'better' rooms must indeed be palatial if this were a fair sample of those somewhat less desirable.

'This will answer admirably,' said Carruth, directing an eyebrow at me. I nodded hastily. I was eager to acquiesce in anything he might have in mind.

'Then we shall call it settled,' remarked Snow. 'I shall have your things brought up at once. Perhaps you would like to remain here now?'

'Thank you,' said Carruth. 'What time do we dine?'

'At seven, if you please, or later if you prefer. I am having a private room for the three of us.'

'That will answer splendidly,' agreed Carruth, and I added a word of agreement. Mr. Snow hurried off to attend to the sending up of our small luggage, and Carruth drew me at once into the room.

'I am a little more than anxious,' he began, 'to hear that tale of the murder. It is an extraordinary step forward—do you not agree with me?—that Billings's account of the disappearing boots—"through the air"—should fit so neatly and unexpectedly into their going around that corner of the corridor where "the shut room" is. It sets us forward, I imagine. What is your impression, Mr. Canevin?'

'I agree with you heartily,' said I. 'The only point on which I am not clear is the matter of the thickness of the walls. Is there anything in that?'

'If you will allow me, I'll defer that explanation until we have had the account of the murder at dinner,' said Carruth, and, our things arriving at that moment, we set about preparing for dinner.

DINNER, in a small and beautifully furnished private room, did more, if anything more were needed, to convince me that Mr. William Snow's reputation as a successful modern innkeeper had been well earned. It was a thoroughly delightful meal in all respects, but that, in a general way, is really all that I remember about it because my attention was wholly occupied in taking in every detail of the strange story which our host unfolded to us beginning with the fish course—I think it was a fried sole—and which ended only when we were sipping the best coffee I had tasted since my arrival in England from our United States.

'In the year 1818,' said Mr. Snow, 'near the end of the long reign of King George III—the king, you will remember, Mr. Canevin, who gave you Americans your Fourth of July—this house was kept by one James Titmarsh. Titmarsh was a very old man. It was his boast that he had taken over the landlordship in the year that His Most Gracious Majesty, George III, had come to the throne, and that he would last as long as the king reigned! That was in the year 1760, and George III had been reigning for fifty-eight years. Old Titmarsh, you see, must have been somewhere in the neighborhood of eighty, himself.

'Titmarsh was something of a "character." For some years the actual management of the inn had devolved upon his nephew, Oliver Titmarsh, who was middle-aged, and none too respectable, though, apparently, an able taverner. Old Titmarsh if tradition is to be believed, had many a row with his deputy, but, being himself childless, he was more or less dependent upon Oliver, who consorted with low company for choice, and did not bear the best of reputations in the community. Old Titmarsh's chief bugbear, in connection with Oliver, was the latter's friendship with Simon Forrester. Forrester lacked only a bard to be immortal. But—there was no Cowper to his John Gilpin, so to speak. No writer of the period, nor indeed since, has chosen to set forth Forrester's exploits. Nevertheless, these were highly notable. Forrester was the very king-pin of the highwaymen, operating with extraordinary success and daring along the much-traveled Brighton Road.

'Probably Old Titmarsh was philosopher enough to ignore his nephew's associations and acts so long as he attended to the business of the inn. The difficulty, in connection with Forrester, was that Forrester, an extraordinarily bold fellow, whose long immunity from the gallows had caused him to believe himself possessed of a kind of charmed life, constantly resorted to The Coach and Horses, which, partly because of its convenient location, and partly because of its good cheer, he made his house-of-call.

'During the evening of the first of June, in the year 1818, a Royal Courier paused at The Coach and Horses for some refreshment and a fresh mount. This gentleman carried one of the old king's peremptory messages to the Prince of Wales, then sojourning at Brighton, and who, under his sobriquet of "First Gentleman of Europe," was addicted to a life which sadly irked his royal parent at Whitehall. It was an open secret that only Prince George's importance to the realm as heir apparent to the throne prevented some very drastic action being taken against him for his innumerable follies and extravagances, on the part of king and parliament. This you will recall, was two years before the old king died and "The First Gentleman" came to the throne as George IV.

'The Royal Messenger, Sir William Greaves, arriving about nine in the evening after a hard ride, went into the coffee-room, to save the time which the engagement and preparation of a private room would involve, and when he paid his score, he showed a purse full of broad gold pieces. He did not know that Simon Forrester, sitting behind him over a great mug of mulled port, took careful note of this unconscious display of wealth in ready money. Sir William delayed no longer than necessary to eat a chop and drink a pot of "Six Ale." Then, his spurs clanking, he took his departure.

'He was barely out of the room before Forrester, his wits, perhaps, affected by the potations which he had been imbibing, called for his own mount, Black Bess, and rose, slightly stumbling to his feet, to speed the pot-boy on his way to the stables.

'"Ye'll not be harrying a Royal Messenger a-Gad's sake, Simon," protested his companion, who was no less a person than Oliver Titmarsh, seizing his crony by his ruffled sleeve of laced satin.

'"Unhand me!" thundered Forrester; then, boastfully, "There's no power in England'll stay Sim Forrester when he chooses to take the road!"

'Somewhat unsteadily he strode to the door, and roared his commands to the stable-boy, who was not leading Black Bess rapidly enough to suit his drunken humor. Once in the saddle, the fumes of the wine he had drunk seemed to evaporate. Without a word Simon Forrester set out, sitting his good mare like a statue, in the wake of Sir William Greaves toward Brighton.

'The coffee-room—as Oliver Titmarsh turned back into it from the doorway whither he had accompanied Forrester—seethed into an uproar. Freed from the dominating presence of the truculent ruffian who would as soon slit a man's throat as look him in the eye along the sights of his horse-pistol from behind the black mask, the numerous guests, silent before, had found their tongues. Oliver Titmarsh sought to drown out their clamor of protest, but before he could succeed, Old Titmarsh, attracted by the unwonted noise, had hobbled down the short flight of steps from his private cubbyhole and entered the room.

'It required only a moment despite Oliver's now frantic efforts to stem the tide of comment, before the old man had grasped the purport of what was toward. Oliver secured comparative silence, then urged his aged uncle to retire. The old man did so, muttering helplessly, internally cursing his age and feebleness which made it out of the question for him to regulate this scandal which had originated in his inn. A King's Messenger, then as now, was sacred in the eyes of all decent citizens. A King's Messenger—to be called on to "stand and deliver" by the villainous Forrester! It was too much. Muttering and grumbling, the old man left the room, but, instead of going back to his easy-chair and his pipe and glass, he stepped out through the kitchens, and, without so much as a lantern to light his path, groped his way to the stables.

'A few minutes later the sound of horse's hoofs in the cobbled stable-yard brought a pause in the clamor which had once more broken out and now raged in the coffee-room. Listening, those in the coffee-room heard the animal trot out through the gate, and the diminishing sound of its galloping as it took the road toward Brighton. Oliver Titmarsh rushed to the door, but the horse and its rider were already out of sight. Then he ran up to his ancient uncle's room, only to find the crafty old man apparently dozing in his chair. He hastened to the stables. One of the grooms was gone, and the best saddle-horse. From the others, duly warned by Old Titmarsh, he could elicit nothing. He returned to the coffee-room in a towering rage and forthwith cleared it, driving his guests out before him in a protesting herd.

'Then he sat down, alone, a fresh bottle before him, to await developments.

'It was more than an hour later when he heard the distant beat of a galloping horse's hoofs through the quiet June night, and a few minutes later Simon Forrester rode into the stable-yard and cried out for an hostler for his Bess.

'He strode into the coffee-room a minute later, a smirk of satisfaction on his ugly, scarred face. Seeing his crony, Oliver, alone, he drew up a chair opposite him, removed his coat, hung it over the back of his chair, and placed over its back where the coat hung, the elaborate leather harness consisting of crossed straps and holsters which he always wore. From the holsters protruded the grips of "Jem and Jack," as Forrester had humorously named his twin horse-pistols, huge weapons, splendidly kept, each of which threw an ounce ball. Then, drawing back the chair, he sprawled in it at his ease, fixing on Oliver Titmarsh an evil grin and bellowing loudly for wine.

'"For," he protested, "my throat is full of the dust of the road, Oliver, and, lad, there's enough to settle the score, never doubt me!" and out upon the table he cast the bulging purse which Sir William Greaves had momentarily displayed when he paid his score an hour and half back.

'Oliver Titmarsh, horrified at this evidence that his crony had actually dared to molest a King's Messenger, glanced hastily and fearfully about him, but the room, empty and silent save for their own presence, held no prying inimical informer. He began to urge upon Forrester the desirability of retiring. It was approaching eleven o'clock, and while the coffee-room was, fortunately, empty, no one knew who might enter from the road or come down from one of the guest-rooms at any moment. He shoved the bulging purse, heavy with its broad gold-pieces, across the table to his crony, beseeching him to pocket it, but Forrester, drunk with the pride of his exploit, which was unique among the depredations of the road's gentry, boasted loudly and tossed off glass after glass of the heavy port wine a trembling pot-boy had fetched him.

'Then Oliver's entreaties were supplemented from an unexpected source. Old Titmarsh, entering through a door in the rear wall of the coffee-room, came silently and leaned over the back of the ruffian's chair, and added a persuasive voice to his nephew's entreaties.

'"Best go up to bed, now, Simon, my lad," croaked the old man, wheedlingly, patting the bulky shoulders of the hulking ruffian with his palsied old hands.

'Forrester, surprised, turned his head and goggled at the graybeard. Then, with a great laugh, and tossing off a final bumper, he rose unsteadily to his feet, and thrust his arms into the sleeves of the fine coat which old Titmarsh, having detached from the back of the chair, held out to him.

'"I'll go, I'll go, old Gaffer," he kept repeating as he struggled into his coat, with mock jocularity, "seeing you're so careful of me! Gad's hooks! I might as well! There be no more purses to rook this night, it seems!"

'And with this, pocketing the purse and taking over his arm the pistol-harness which the old man thrust at him, the villain lumbered up the stairs to his accustomed room.

'"Do thou go after him, Oliver," urged the old man. "I'll bide here and lock the doors. There'll likely be no further custom this night."

'Oliver Titmarsh, sobered, perhaps, by his fears, followed Forrester up the stairs, and the old man, crouched in one of the chairs, waited and listened, his ancient ears cocked against a certain sound he was expecting to hear.

'It came within a quarter of an hour—the distant beat of the hoofs of horses, many horses. It was, indeed, as though a considerable company approached The Coach and Horses along the Brighton Road. Old Titmarsh smiled to himself and crept toward the inn doorway. He laboriously opened the great oaken door and peered into the night. The sound of many hoofbeats was now clearer, plainer.

'Then, abruptly, the hoofbeats died on the calm June air. Old Titmarsh, somewhat puzzled, listened, tremblingly. Then he smiled in his beard once more. Strategy, this! Someone with a head on his shoulders was in command of that troop! They had stopped, at some distance, lest the hoofbeats should alarm their quarry.

'A few minutes later the old man heard the muffled sound of careful footfalls, and, within another minute, a King's Officer in his red coat had crept up beside him.

'"He's within," whispered Old Titmarsh, "and well gone by now in his damned drunkard's slumber. Summon the troopers, sir. I'll lead ye to where the villain sleeps. He hath the purse of His Majesty's Messenger upon him. What need ye of better evidence?"

'"Nay," replied the train-band captain in a similar whisper, "that evidence, even, is not required. We have but now taken up the dead body of Sir William Greaves beside the highroad, an ounce ball through his honest heart. 'Tis a case, this, of drawing and quartering, Titmarsh; thanks to your good offices in sending your boy for me."

'The troopers gradually assembled. When eight had arrived, the captain, preceded by Old Titmarsh and followed in turn by his trusty eight, mounted the steps to where Forrester slept. It was, as you have guessed, the empty room you examined this afternoon, "the shut room" of this house.

'At the foot of the upper stairs the captain addressed his men in a whisper: "A desperate man, this, lads. 'Ware bullets! Yet—he must needs be taken alive, for the assizes, and much credit to them that take him. He hath been a pest of the road as well ye know these many years agone. Upon him, then, ere he rises from his drunken sleep! He hath partaken heavily. Pounce upon him ere he rises."

'A mutter of acquiescence came from the troopers. They tightened their belts, and stepped alertly, silently, after their leader, preceded by their ancient guide carrying a pair of candles.

'Arrived at the door of the room the captain disposed his men and crying out "in the King's name!" four of these stout fellows threw themselves against the door. It gave at once under that massed impact, and the men rushed into the room, dimly lighted by Old Titmarsh's candles.

'Forrester, his eyes blinking evilly in the candle-light, was halfway out of bed when they got into the room. He slept, he was accustomed to boast, "with one eye open, drunk or sober!" Throwing off the coverlid, the highwayman leaped for the chair over the back of which hung his fine laced coat, the holsters uppermost. He plunged his hands into the holsters, and stood, for an instant, the very picture of baffled amazement.

'The holsters were empty!

'Then, as four stalwart troopers flung themselves upon him to bear him to the floor, there was heard Old Titmarsh's harsh, senile cackle.

'"'Twas I that robbed ye, ye villain—took your pretty boys, your 'Jem' and your 'Jack' out the holsters whiles ye were strugglin' into your fine coat! Ye'll not abide in a decent house beyond this night, I'm thinking; and 'twas the old man who did for ye, murdering wretch that ye are!"

'A terrific struggle ensued. With or without his "Pretty Boys" Simon Forrester was a thoroughly tough customer, versed in every sleight of hand-to-hand fighting. He bit and kicked; he elbowed and gouged. He succeeded in hurling one of the troopers bodily against the blank wall, and the man sank there and lay still, a motionless heap. After a terrific struggle with the other three who had cast themselves upon him, the remaining troopers and their captain standing aside because there was not room to get at him in the mêlée, he succeeded in getting the forefinger of one of the troopers, who had reached for a face-hold upon him, between his teeth, and bit through it at the joint.

'Frantic with rage and pain this trooper, disengaging himself, and before he could be stopped, seized a heavy oaken bench and, swinging it through the air, brought it down on Simon Forrester's skull. No human bones, even Forrester's, could sustain that murderous assault. The tough wood crunched through his skull, and thereafter he lay quiet. Simon Forrester would never be drawn and quartered, nor even hanged. Simon Forrester, ignobly, as he had lived, was dead; and it remained for the troopers only to carry out the body and for their captain to indite his report.

'Thereafter, the room was stripped and closed by Old Titmarsh himself, who lived on for two more years, making good his frequent boast that his reign over The Coach and Horses would equal that of King George III over his realm. The old king died in 1820, and Old Titmarsh did not long survive him. Oliver, now a changed man, because of this occurrence, succeeded to the lease of the inn, and during his landlordship the room remained closed. It has been closed, out of use, ever since.'

Mr. Snow brought his story, and his truly excellent dinner, to a close simultaneously. It was I who broke the little silence which followed his concluding words.

'I congratulate you, sir, upon the excellence of your narrative-gift. I hope that if I come to record this affair, as I have already done with respect to certain odd happenings which have come under my view, I shall be able, as nearly as possible, to reproduce your words.' I bowed to our host over my coffee cup.

'Excellent, excellent, indeed!' added Carruth, nodding and smiling pleasantly in Mr. Snow's direction. 'And now—for the questions, if you don't mind. There are several which have occurred to me; doubtless also to Mr. Canevin.'

Snow acquiesced affably. 'Anything you care to ask, of course.'

'Well, then,' it was Carruth, to whom I had indicated precedence in the questioning, 'tell us, if you please, Mr. Snow—you seem to have every particular at your very fingers' ends—the purse with the gold? That, I suppose, was confiscated by the train-band captain and eventually found its way back to Sir William Greaves's heirs. That is the high probability, but—do you happen to know as a matter of fact?'

'The purse went back to Lady Greaves.'

'Ah! and Forrester's effects—I understand he used the room from time to time. Did he have anything, any personal property in it? If so, what became of it?'

'It was destroyed, burned. No one claimed his effects. Perhaps he had no relatives. Possibly no one dared to come forward. Everything in his possession was stolen, or, what is the same, the fruit of his thefts.'

'And—the pistols, "Jem and Jack?" Those names rather intrigued me! What disposition was made of them, if you happen to know? Old Titmarsh had them, of course, concealed somewhere; probably in that "cubbyhole" of his which you mentioned.'

'Ah,' said Mr. Snow, rising, 'there I can really give you some evidence. The pistols are in my office—in the Chubbs' safe, along with the holster-apparatus, the harness which Forrester wore under his laced coat. I will bring them in.'

'Have you the connection, Mr. Canevin?' Lord Carruth enquired of me as soon as Snow had left the dining-room.

'Yes,' said I, 'the connection is clear enough; clear as a pikestaff, to use one of your time-honored British expressions, although I confess never to have seen a pikestaff in my life! But—apart from the fact that the holsters are made of leather; the well-known background of the unfulfilled desire persisting after death; and the obvious connection between the point of disappearance of those "walking-boots" of Billings, with "the shut room," I must confess myself at a loss. The veriest tyro at this sort of thing would connect those points, I imagine. There it is, laid out for us, directly before our mental eyes, so to speak. But—what I fail to understand is not so much who takes them—that by a long stretch of the imagination might very well be the persistent "shade," "Ka," "projected embodiment" of Simon Forrester. No—what gets me is —where does the carrier of boots and satchels and jewelers' sample-cases put them? That room is utterly, absolutely, physically empty, and boots and shoes are material affairs, Lord Carruth.'

Carruth nodded gravely. 'You have put your finger on the main difficulty, Mr. Canevin. I am not at all sure that I can explain it, or even that we shall be able to solve the mystery after all. My experience in India does not help. But—there is one very vague case, right here in England, which may be a parallel one. I suspect, not to put too fine a point upon the matter, that the abstracted things may very well be behind that rearmost wall, the wall opposite the doorway in "the shut room."'

'But,' I interjected, 'that is impossible, is it not? The wall is material—brick and stone and plaster. It is not subject to the strange laws of personality. How—?'

THE return of the gentleman-landlord of The Coach and Horses at this moment put an end to our conversation, but not to my wonder. I imagined that the 'case' alluded to by my companion would be that of the tortured 'ghost' of the jester which, with a revenge-motive, haunted a room in an ancient house and even managed to equip the room itself with some of its revengeful properties or motives. The case had been recorded by Mr. Hodgson, and later Carruth told me that this was the one he had in mind. This, it seemed to me, was a very different matter. However—

Mr. Snow laid the elaborate and beautifully made 'harness' of leather straps out on the table beside the after-dinner coffee service. The grips of 'Jem' and 'Jack' peeped out of their holsters. The device was not unlike those used by our own American desperadoes, men like the famous Earp brothers and 'Doc' Holliday whose 'six-guns' were carried handily in slung holsters in front of the body. We examined these antique weapons, murderous-looking pistols of the 'bulldog' type, built for business, and Carruth ascertained that neither 'Jem' nor 'Jack' was loaded.

'Is there anyone on that top floor?' enquired Carruth.

'No one save yourselves, excepting some of the servants, who are in the other end of the house,' returned Snow.

'I am going to request you to let us take these pistols and the "harness" with us upstairs when we retire,' said Carruth, and again the obliging Snow agreed. 'Everything I have is at your disposal, gentlemen,' said he, 'in the hope that you will be able to end this annoyance for me. It is too early in the season at present for the inn to have many guests. Do precisely as you wish, in all ways.'

SHORTLY after nine o'clock, we took leave of our pleasant host, and, carrying the 'harness' and pistols divided between us, we mounted to our commodious bedchamber. A second bed had been moved into it, and the fire in the grate took off the slight chill of the spring evening. We began our preparations by carrying the high-powered electric torches we had obtained from Snow along the corridor and around the corner to 'the shut room.' We unlocked the door and ascertained that the two torches would be quite sufficient to work by. Then we closed but did not lock the door, and returned to our room.

Between us, we moved a solidly built oak table to a point diagonally across the corridor from our open bedroom door, and on this we placed the 'harness' and pistols. Then, well provided with smoke-materials, we sat down to wait, seated in such positions that both of us could command the view of our trap. It was during the conversation which followed that Carruth informed me that the case to which he had alluded was the one recorded by the occult writer, Hodgson. It was familiar to both of us. I will not cite it. It may be read by anybody who has the curiosity to examine it in the collection entitled Carnacki the Ghost-Finder by William Hope Hodgson. In that account it is the floor of the 'haunted' room which became adapted to the revenge-motive of the persistent 'shade' of the malignant court jester, tortured to death many years before his 'manifestation' by his fiendish lord and master.

We realized that, according to the man Billings's testimony, we need not be on the alert before midnight. Carruth therefore read from a small book which he had brought with him, and I busied my-self in making the careful notes which I have consulted in recording Mr. Snow's narrative of Simon Forrester, while that narrative was fresh in my memory. It was a quarter before midnight when I had finished. I took a turn about the room to refresh my somewhat cramped muscles, and returned to my comfortable chair.

MIDNIGHT struck from the French clock on our mantelpiece, and Carruth and I both, at that signal, began to give our entire attention to the articles on the table in the hallway out there.

It occurred to me that this joint watching, as intently as the circumstances seemed to warrant to both of us, might prove very wearing, and I suggested that we watch alternately, for about fifteen minutes each. We did so, I taking the first turn. Nothing occurred—not a sound, not the smallest indication that there might be anything untoward going on out there in the corridor.

At twelve-fifteen, Carruth began to watch the table, and it was, I should imagine, about five minutes later that his hand fell lightly on my arm, pressing it and arousing me to the keenest attention. I looked intently at the things on the table. The 'harness' was moving toward the lefthand edge of the table. We could both hear, now, the slight scraping sound made by the leather weighted by the twin pistols, and, even as we looked, the whole apparatus lifted itself—or so it appeared to us—from the supporting table, and began, as it were, to float through the air a distance of about four feet from the ground toward the turn which led to 'the shut room.'

We rose, simultaneously, for we had planned carefully on what we were to do, and followed. We were in time to see the articles 'float' around the corner, and, increasing our pace—for we had been puzzled about how anything material, like the boots, could get through the locked door—watched, in the rather dim light of that short hallway, what would happen.

What happened was that the 'harness' and pistols reached the door, and then the door opened. They went through, and the door shut behind them precisely as though someone, invisible to us, were carrying them. We heard distinctly the slight sound which a gently closed door makes as it came to, and there we were, standing outside in the hallway looking at each other. It is one thing to figure out, beforehand, the science of occult occurrences, even upon the basis of such experience as Carruth and I both possessed. It is, distinctly, another, to face the direct operation of something motivated by the Powers beyond the ordinary ken of humanity. I confess to certain 'cold chills,' and Carruth's face was very pale.

We switched on our electric torches as we had arranged to do, and Carruth, with a firm hand which I admired if I did not, precisely, envy, reached out and turned the knob of the door. We walked into 'the shut room'....

Not all our joint experience had prepared us for what we saw. I could not forbear clutching Carruth's free arm, the one not engaged with the torch, as he stood beside me. And I testify that his arm was as still and firm as a rock. It steadied me to realize such fortitude, for the sight which was before us was enough to unnerve the most hardened investigator of the unearthly.

Directly in front of us, but facing the blank wall at the far end of the room, stood a half-materialized man. The gleam of my torch threw a faint shadow on the wall in front of him, the rays passing through him as though he were not there, and yet with a certain dimming. The shadow visibly increased in the few brief instants of our utter silence, and then we observed that the figure was struggling with something. Mechanically we concentrated both electric rays on the figure and then we saw clearly. A bulky man, with a bull-neck and close-cropped, iron-gray hair, wearing a fine satin coat and what were called, in their day, 'small cloths,' or tight-fitting knee-trousers with silk stockings and heavy, buckled shoes, was raising and fitting about his waist, over the coat, the 'harness' with the pistols.

Abruptly, the materialization appearing to be now complete, he turned upon us, with an audible snarl and baleful, glaring little eyes like a pig's, deep set in a hideous, scarred face, and then he spoke—he spoke, and he had been dead for more than a century!

'Ah-h-h-h!' he snarled, evilly, 'ye would come in upon me, eh, my fine gents—into this my chamber, eh! I'll teach ye manners....' and he ended this diatribe with a flood of the foulest language imaginable, stepping, with little, almost mincing, downtoed steps toward us all the time he poured out his filthy curses and revilings. I was completely at a loss what to do. I realized—these ideas went through my mind with the rapidity of thought—that the pistols were unloaded! I told myself that this was some weird hallucination—that the shade of no dead-and-gone desperado could harm us. Yet—it was a truly terrifying experience, be the man shade or true flesh and blood.

Then Carruth spoke to him, in quiet, persuasive tones.

'But—you have your pistols now, Simon Forrester. It was we who put them where you could find them, your pretty boys, "Jem" and "Jack." That was what you were trying to find, was it not? And now—you have them. There is nothing further for you to do—you have them, they are just under your hands where you can get at them whenever you wish.'

At this the specter, or materialization of Simon Forrester, blinked at us, a cunning light in his evil little eyes, and dropped his hands with which he had but now been gesticulating violently on the grips of the pistols. He grinned, evilly, and spat in a strange fashion, over his shoulder.

'Ay,' said he, more moderately now, 'ay—I have 'em—Jemmy and Jack, my trusties, my pretty boys.' He fondled the butts with his huge hands, hands that could have strangled an ox, and spat over his shoulder.

'There is no necessity for you to remain, then, is there?' said Carruth softly, persuasively.

The simulacrum of Simon Forrester frowned, looked a bit puzzled, then nodded its head several times.

'You can rest now—now that you have Jem and Jack,' suggested Carruth, almost in a whisper, and as he spoke, Forrester turned away and stepped over to the blank wall at the far side of the room, opposite the doorway, and I could hear Carruth draw in his breath softly and feel the iron grip of his fingers on my arm. 'Watch!' he whispered in my ear; 'watch now.'

The solid wall seemed to wave and buckle before Forrester, almost as though it were not a wall but a sheet of white cloth, held and waved by hands as cloth is waved in a theater to simulate waves. More and more cloth-like the wall became, and, as we gazed at this strange sight, the simulacrum of Simon Forrester seemed to become less opaque, to melt and blend in with the wavering wall, which gradually ceased to move, and then he was gone and the wall was as it had been before...

ON Monday morning, at Carruth's urgent solicitation, Snow assembled a force of laborers, and we watched while they broke down the wall of 'the shut room' opposite the doorway. At last, as Carruth had expected, a pick went through, and, the interested workmen, laboring with a will, broke through into a small, narrow, cell-like room the plaster of which indicated that it had been walled up perhaps two centuries before, or even earlier—a 'priest's hole' in all probability, of the early post-reformation period near the end of the Sixteenth Century.

Carruth stopped the work as soon as it was plain what was here, and turned out the workmen, who went protestingly. Then, with only our host working beside us, and the door of the room locked on the inside, we continued the job. At last the aperture was large enough, and Carruth went through. We heard an exclamation from him, and then he began to hand out articles through the rough hole in the masonry—leather articles—boots innumerable, ladies' reticules, hand-luggage, the missing jeweler's sample case with its contents intact—innumerable other articles, and, last of all, the 'harness' with the pistols in the holsters.

Carruth explained the 'jester case' to Snow, who shook his head over it. 'It's quite beyond me, Lord Carruth,' said he, 'but, as you say this annoyance is at an end, I am quite satisfied; and—I'll take your advice and make sure by pulling down the whole room, breaking out the corridor walls, and joining it to the room across the way. I confess I can not make head or tail of your explanation—the unfulfilled wish, the "sympathetic pervasion" of the room as you call it, the "materialization," and the strange fact that this business began only a short time ago. But—I'll do exactly what you have recommended, about the room, that is. The restoration of the jeweler's case will undoubtedly make it possible for me to get back the sum I paid Messrs Hopkins and Barth of Liverpool when it disappeared in my house. Can you give any explanation of why the "shade" of Forrester remained quiet for a century and more and only started up the other day, so to speak?'

'It is because the power to materialize came very slowly,' answered Carruth, 'coupled as it undoubtedly was with the gradual breaking down of the room's material resistance. It is very difficult to realize the extraordinary force of an unfulfilled wish, on the part of a forceful, brutal, wholly selfish personality like Forrester's. It is, really, what we must call spiritual power, even though the "spirituality" was the reverse of what we commonly understand by that term. The wish and the force of Forrester's persistent desire, through the century, have been working steadily, and, as you have told us, the room has been out of use for more than a century. There were no common, everyday affairs to counteract that malign influence—no "interruptions," if I make myself clear.'

'Thank you,' said Mr. Snow. 'I do not clearly understand. These matters are outside my province. But—I am exceedingly grateful—to you both.' Our host bowed courteously. 'Anything that I can possibly do, in return—'

'There is nothing—nothing whatever,' said Carruth quietly; 'but, Mr. Snow, there is another problem on your hands which perhaps you will have some difficulty in solving, and concerning which, to our regret'—he looked gravely at me—'I fear neither Mr. Canevin with his experience, nor I with mine, will be able to assist you.'

'And what, pray, is that?' asked Mr. Snow, turning slightly pale. He would, I perceive, be very well satisfied to have his problems behind him.

'The problem is,' said Carruth, even more gravely I imagined, 'it is—what disposal are you to make of fifty-eight pairs of assorted boots and shoes!'

And Snow's relieved laughter was the last of the impressions which I took with me as we rode back to London in Carruth's car, of The Coach and Horses inn on the Brighton Road.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.