RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

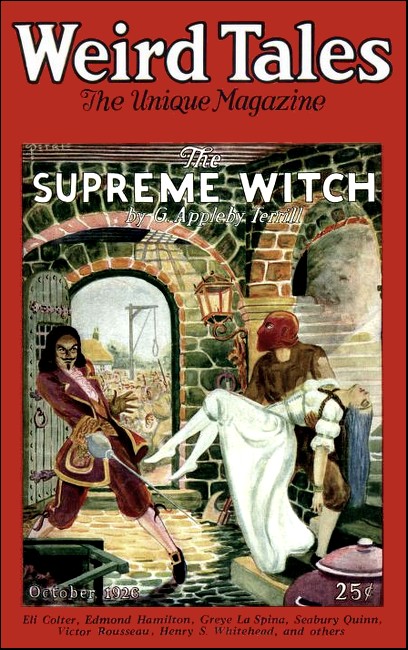

Weird Tales, October 1926, with "The Projection Of Armand Dubois"

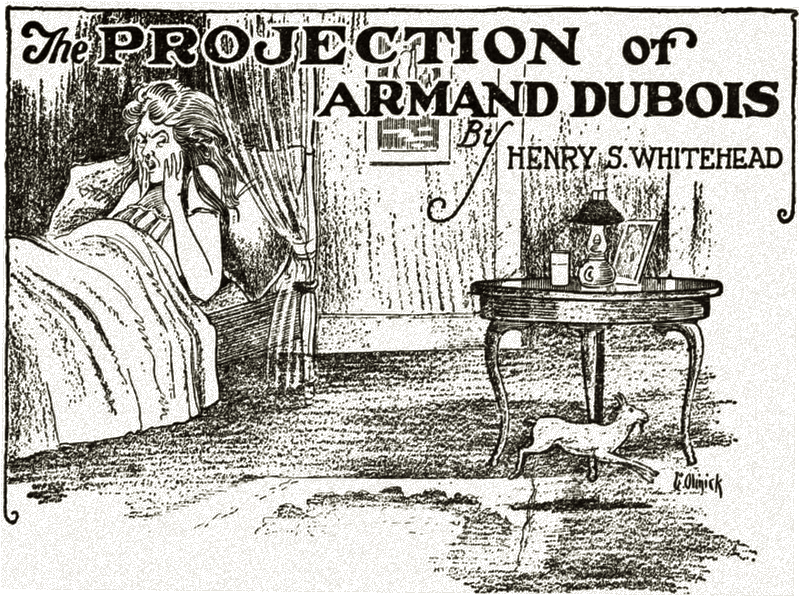

"She could hear the clatter of its tiny hard hooves on the pitch-

pine floor, occasionally muffled in the queeresr eeriest way."

A tale of voodoo in the Virgin Islands—a specter that threw

vitriol—and a little goat that frightened Madame Du Chaillu.

SOME time before my marriage, when I was living in Marlborough House, the old mansion on the hill back of the town of Frederiksted, on the West Indian island of St. Croix—that is to say, before I became a landed-proprietor, as I did later, and was still making a veritable living by the production and sale of my tales—I had a next-door neighbor by the name of Mrs. Minerva Du Chaillu. I do not know whether the late Monsieur Du Chaillu, of whom this good lady was the relict, was related or not to the famous Paul of that name, that slaughterer of wild animals in the far corners of the earth, who was, and may still be, for all I know, the greatest figure of all the big game hunters, but her husband, Monsieur Placide Du Chaillu, had been for many years a clergyman of the English Church on that strange island of St. Martin, with its two flat towns, Phillipsbourg, capital of the Dutch Side, and Maragot, capital of the French Side.

The English Church was, and still is, existent only among the Dutch residents, Maragot being without an English Church. Therefore, Mrs. Du Chaillu's acquaintance, even after many years' residence on St. Martin, was almost entirely confined to the Dutch Side, where, curiously enough, English and French, rather than Dutch, are spoken, and which, although only eight miles from the French capital, has only slight communication therewith, because of the execrable quality of the connecting roads.

This old lady, well past seventy at the time, used to sit on her gallery late afternoons, when the fervor of the afternoon sun had somewhat abated, and rock herself steadily to and fro, and fan in the same indefatigable fashion as ancient Mistress Desmond, my landlady. Occasionally I would step across and exchange the time of day with her. I had known her for several years before she got her courage up to the point of asking me if some day I would not allow her to see some things I had written.

Such a request is always a compliment, and this I told her, to relieve her obvious embarrassment. A day or so later I took over to Mrs. Du Chaillu a selection of three or four manuscript-carbons, and a couple of magazines containing my stories, and I could see her from time to time, afternoons, reading them. I could even guess which ones she had finished and which she was currently engaged in perusing, by the expression of her kindly face as she read.

Four or five days later she sent for me, and when I had gone across to her gallery, she thanked me, very formally as a finely-bred gentlewoman of several generations of West Indian background might be expected to do, handed back the stories, and, with much hesitation, and almost blushingly, intimated that she could tell me a story herself, if I cared to use it!

'Of course,' added Mrs. Du Chaillu, 'you'd have to change it about and embellish it a great deal, Mr. Canevin.'

To this I said nothing, except to urge my old friend to proceed, and this she did forthwith, hesitating at first, then, becoming intrigued by the memories of the tale, with the flair of a quite unexpected narrative gift. During the first few minutes of the then halting recital, I interrupted occasionally, for the purpose of getting this or that point clear, but as the story progressed I quieted down, and before it was finished, I was sitting, listening as though to catch pearls, for here was my simon-pure West Indian 'Jumbee' story, a gem, a perfect example, and told—you may believe me or not, sir or madam—with every possible indication of authenticity. Unless there is something hitherto unsuspected (even by his best friends, those keenest of critics) with the understanding apparatus of Gerald Canevin, that story as Mrs. Du Chaillu told it to him, had happened, just as she said it had—to her.

I will add only that I have not, to my knowledge, changed a word of it. It is not only not embellished (or 'glorified,' as the Black People would say) but it is as nearly verbatim as I can manage it; and I believe it implicitly. It fits in with much that is known scientifically and verified by occult investigators and suchlike personages; it is typically, utterly, West Indian; and Mrs. Du Chaillu would as soon vary one jot or tittle from the strict truth in this or any other matter, as to attempt to stand on her head—and that, if you knew the dear old soul as I do, with her rheumatism, and her seventy-six years, and her impeccable, lifelong respectability, is as much as to say, impossible! For the convenience of any possible readers, I will tell her story for her, as nearly as possible in her own words, without quotation marks...

I HAD been living in Phillipsbourg about two years; perhaps slightly longer (said Mrs. Du Chaillu) when one morning I had occasion to go into my husband's study, or office. Monsieur Du Chaillu—as he was generally called, of course, even though he was a clergyman of the Church of England—was, at the moment of my arrival, opening one of the two 'strong-boxes,' or old-fashioned iron safes which he had standing side by side, and in which he kept his own money and the various parish funds of which he had charge.

The occasion of my going into his office, where he received the parishioners—you know in these West Indian parishes the Black People come in streams to consult 'Gahd's An'inted' about every conceivable matter from a family row to a stolen papaya—was on account of Julie. Julie was a very good and reliable servant, a young woman whose health was not very good, and whom I was keeping in one of the spare-rooms of our house. The rectory was a large residence, just next-door to the Government House, and poor Julie did better, we thought, inside than in one of the servants' rooms in the yard. Every day I would give Julie a little brandy. She had come for her brandy a few minutes before—it was about four-thirty in the afternoon—and I discovered that I would have to get a fresh bottle. Monsieur Du Chaillu was in the office and had the key of the big sideboard, and I had stepped in to get the key from him.

As I say, he was just opening one of the safes.

I said: 'Placide, what are you doing?' It was one of those meaningless questions. I could see clearly what he was doing. He was opening his safe, the one in which he kept his own private belongings, and I need not have asked so obvious a question.

My husband straightened up, however, not annoyed, you understand, but somewhat surprised, because I never entered his office as a rule, and remarked that he was getting some money out because he had a bill to pay that afternoon.

I asked him for the key to the sideboard and came and stood beside him as he reached down into the safe, which was the kind that opened with a great heavy lid on the top, like a cigar-box, or the cover for a cistern. He reached into his pocket with his left hand after the sideboard key, his right hand full of currency, and I looked into the safe. There on top lay a paper which I took to be a kind of promissory note. I read it, hastily. I was his wife. There was, I conceived, nothing secret about it.

'What is this, Placide?' I inquired.

My husband handed me the key to the sideboard.

'What is what, my dear Minerva?' he asked.

'This note, or whatever it is. It seems as though you had loaned three hundred dollars a good while ago, and never got it back.'

'That is correct,' said my husband. 'I have never felt that I wished to push the matter.' He picked up the note with his now free left hand, in a ruminating kind of manner, and I saw there was another note underneath. I picked that one up myself, my husband making no objection to my doing so, and glanced through it. That, too, was for three hundred dollars. Both were dated between seventeen and eighteen years previously, that is, in the year 1863, although they were of different months and days, and both were signed by men at that time living in Phillipsbourg, both prosperous men; one a white gentleman-planter in a small way; the other a colored man with a not very good reputation, but one who had prospered and was accounted well-to-do.

Well, my husband stood there with one note in his hand, and I stood beside him, holding the other. I did a rough sum in mental arithmetic. The notes were 'demand' notes, at eight per cent, simple interest, representing, the two together, six hundred dollars. Eighteen years of interest, at eight per cent added on, it seemed to me, would cause these notes to amount to a great deal more than twice six hundred dollars, something around fifteen hundred, in fact. We were far from rich!

'But, my dear Placide, you should collect these,' I cried.

'I have never wished to press them,' replied my husband.

'Allow me, if you please, to take them,' I begged him.

'Do as you wish, Minerva my dear,' replied Monsieur Du Chaillu. 'But, I beg of you, no lawsuits!'

'Very well,' said I, and, carrying the two notes, walked out of the office to get Julie her brandy, out of the sideboard in the dining room.

I will admit to you, Mr. Canevin, that I was a little put out about my dear husband's carelessness in connection with those notes. At the same time, I could not avoid seeing very clearly that the notes, if still collectible, constituted a kind of windfall, as you say in the United States—it has to do with a variety of apple, does it not?—and I decided at once to set about a kind of investigation.

As soon as I had supplied Julie with a brandy which Dr. Duchesne had prescribed for her, I sent our houseboy after Monsieur Henkes, the notary of our town of Phillipsbourg. Monsieur Henkes came within the hour—he stayed for tea, I remember—and he assured me that the notes, not yet being twenty years old, were still collectible. I placed them in his hands, and paid him, in advance, as the custom is on St. Martin, and, I dare say, in Curaçao, and the other Dutch possessions, his fee of fifty dollars for collection, instructing him that it was my husband's desire that there should be no actual lawsuit.

I will shorten my story as much as possible, by telling you that the note which had been given by the gentleman-planter was paid, in six months, in two equal installments, and, with my husband's permission, I invested the money in some shares in one of our St. Martin Salt-Ponds—salt, you know, is the chief export from St. Martin.

The other note, the one which had been given by the colored man, Armand Dubois, did not go through so easily. Here in the West Indies, as you have surely observed, our 'colored' people, as distinct from the Black laboring class, are, commonly, estimable persons, who conduct themselves like us Caucasians. Dubois, however, was exceptional. He was only about one-quarter African—a quadroon, or thereabouts. But his leanings, as sometimes happens, were to the Black side of his heredity. Many persons in Phillipsbourg regarded him as a rascal, a person of no character at all. It seems he had heard, far back, in the days when my husband accommodated his friend, the planter, of that transaction, and had come almost at once to ask for a similar accommodation. That is why the two notes were so nearly of the same date, and perhaps it accounts for the fact that the two notes were both for three hundred dollars. Negroes, and those persons of mixed blood whose Black side predominates, are not very inventive. It would be quite characteristic for such a person to ask for the same sum as had been given to the former applicant.

Dubois made a great pother about paying. Of this I heard only rumors, of course. Monsieur Henkes did not trouble us in the matter, once the collection of the notes had been placed in his hands. It was, of course, a perfectly clear case. The note had been signed by Dubois, and it had more than two years to run before it would be outlawed—'limited' is, I believe, the legal term. So Armand Dubois paid, as he was well able to do, but, as I say, with a very bad grace. Presumably he expected never to pay. The impudence of the man!

SHORTLY after I had placed the notes in the hands of Monsieur Henkes for collection, Julie came to me one afternoon, quite gray in the face, as Negroes look when they are badly frightened. On St. Martin, perhaps you know, Mr. Canevin, servants have a custom similar to what I have read about in your South. That is to say, they invariably address their mistresses as 'Miss,' with the Christian name. Why, I can not say. It is their custom. Julie came to me, as I say, very frightened, very much upset—quite terrified, in fact.

She said to me: 'Miss Minerva, on no account, ma'am, mus' yo' go to de door, if yo' please, ma'am. One Armand Dubois come, ma'am, an' is even now cloimbing de step of de gol'ry. Hoide yo'self, ma'am, I beg of yo,' in de name of Gahd!'

Julie's distress and state of fright, which the girl could not conceal, impressed me more than her words. I said: 'Julie, go to the door yourself. Say, please, to this Dubois, that I have nothing to say to him. For anything whatever, he must address himself to Monsieur Henkes.'

'Yes, ma'am,' replied Julie, and almost pushed me into my bedroom and shut the door smartly behind me. I stood there, and listened, as Dubois, who had now mounted the gallery steps, knocked, very truculently, it seemed to me—the creature had no manners—on the door. I could hear him ask for me, and the murmur of Julie's voice as she delivered my message. Dubois was reluctant to leave, it seemed. He stood and parleyed, but forcing his way into a house like the rectory of the English Church was beyond him, and at last he went. Several other persons, black fellows, Julie told me, had accompanied him, for what purpose I can not imagine—it was most unusual that he should come to trouble me at all—and these all walked down the street, as I could see through the slanted jalousies of my bedroom window, Dubois gesticulating and orating to his followers.

Julie told me something else, too—something which quite made my blood run cold. Armand Dubois, said Julie, had, half-concealed in his hand, as he stood talking to her, a small vial. Julie was sure it contained vitriol. I was almost afraid to venture out to the street after that, and it was a long time before I recovered from the shock of it. Vitriol—think of it, Mr. Canevin!—if indeed that were what he had in the vial; and what else could he have had?

Of course, I did not dare tell my husband. It would have distressed that dear, kind man most atrociously; and besides, the collection of the notes was, so to speak, a venture of mine, carried out, if not exactly against his will, at least without any enthusiasm on his part. So I kept quiet, and commanded Julie to say nothing whatever about it. I was sure, too, that even a person like Armand Dubois would, in a short time, get over the condition of rage in which Monsieur Henkes's visit to him must have left him to induce him to come to me at all. That, or something similar, actually proved to be the case. I had no further annoyance from Dubois, and in the course of a few weeks, probably pressed by Monsieur Henkes, he settled the note, paying seven hundred and twenty-four dollars, to be exact, with seventeen years and eight months' interest at eight per cent.

Of course, Mr. Canevin, all that portion of the story, except, perhaps, for Armand Dubois's unpleasant visit, is merely commonplace—the mere narrative of the collection of two demand-notes. Note, though, what followed!

IT was, perhaps, two months after the day when I had gone into my husband's office and discovered those notes, and about a month after Dubois had paid what he owed Monsieur Du Chaillu, that I had gone to bed, a trifle earlier, perhaps, than usual—about half-past nine, to be exact. My aunt was staying with us in the rectory at the time, and she was far from well, and I had been reading to her and fanning her, and I was somewhat tired. I fell asleep, I suppose, immediately after retiring.

I awakened, and found myself sitting bolt-upright in my bed, and the clock in the town was striking twelve. I counted the strokes. As I finished, and the bell ceased its striking, I felt, rather than saw—for I was looking, in an abstracted kind of fashion, straight before me, my elbows on my knees, in a sitting posture, as I have said—something at the left, just outside the mosquito-netting. There was a dim night-light, such as I always kept, in the far corner of the room, on the edge of my bureau, and by its light the objects in the room were faintly visible through the white net.

I turned, suddenly, under the impulse of that feeling, and there, Mr. Canevin, just beside the bed, and almost pressing against the net though not quite touching it, was a face. The face was that of a mulatto, and as I looked at it, frozen, speechless, I observed that it was Armand Dubois, and that he was glaring at me, with an expression of the most horrible malignancy that could be imagined. The lips were drawn back—like an animal's, Mr. Canevin—but the most curious, and perhaps the most terrifying, aspect of the situation, was the fact that the face was on a level with the bed, that is, the chin seemed to rest against the edge of the mattress, so that, as it occurred to me, the man must be sitting on the floor, his legs placed under the bed, so as to bring his horrible leering face in that position I have described.

I tried to scream, and my voice was utterly dried up. Then, moved by what impulse I can not describe, I plunged toward the face, tore loose the netting on that side, and looked directly at it.

Mr. Canevin, there was nothing there, but, as I moved abruptly toward it, I saw a vague, dim hand and arm swing up from below, and there was the strangest sensation! It was as though, over my face and shoulders and breast, hot and stinging drops had been cast. There was, for just a passing instant, the most dreadful burning, searing sensation, and then it was gone. I half sat, half lay, a handful of the netting in my hands, where I had torn it loose from where it had been tucked under the edge of the mattress, and there was nothing there—nothing whatever; I passed my hand over my face and neck, but there was nothing; no burns—nothing.

I do not know how I managed to do it, but I climbed out of bed, and looked underneath. Mr. Canevin, there was nothing, no man, nor anything, there. I walked over and turned up the night-light, and looked all about the room. Nothing. The jalousies were all fastened, as usual. The door was locked. There were no other means of ingress or egress.

I went back to bed, convinced that I must have been dreaming or sleepwalking, or something of the sort, although I had never walked in my sleep, and almost never dreamed or remembered any dream. I could not sleep, and it occurred to me that I would do well to get up again, put on my bathrobe, and go out to the dining room for a drink of water. The water stood, in earthenware 'gugglets,' just beside a doorway that led out to a small gallery at the side of the house—which stood on the corner—in the wind, so as to keep cool. You've seen that, a good many times, even here, of course. On St. Martin we had no ice-plant in those days, nor yet, so far as I know, and everybody kept the drinking-water in gugglets and set the gugglets where the wind would blow on them and cool the water.

I took a glass from the sideboard, filled it, and drank the water. Then I opened the door just beside me, and stood looking out for a few minutes. The town was absolutely silent at that hour. There was no moon, and the streets were lighted just as they were here in Frederiksted before we had electricity, with occasional hurricane lanterns at the corners. The one on our corner was burning steadily, and except for the howling of a dog somewhere in the town, everything was absolutely quiet and peaceful, Mr. Canevin.

I went back to bed, and fell asleep immediately. At any rate I have no recollection of lying there hoping for sleep.

Then, immediately afterward, it seemed, I was awakened a second time. This time I was not sitting up when I came to my waking senses, but it did not take me very long to sit up, I can assure you! For the most extraordinary thing was happening in my bedroom.

In the exact center of the room there stood a round, mahogany table. Around and around that table, a small goat was running, from right to left—that is, as I looked toward the table, the goat was running away from me around to the right, and coming back at the left. I could hear the clatter of its little, hard hoofs on the pitch-pine floor, occasionally muffled in the queerest way—it sounds like nothing in the telling, of course—when the goat would step on the small rug on which the table stood. I could see its great, shining eyes, like green moons, every time it came around to the left.

I watched the thing, fascinated, and a slow horror began to grow upon me. I think I swooned, for the last thing I remember is my senses leaving me, but it must have been a very light fainting fit, Mr. Canevin, for I aroused myself, and the room was absolutely silent.

I was shaking all over as though I had been having an attack of the quartan ague, but I managed once more to slip under the netting, reach for my bathrobe, and go over and turn up the night-light. I observed that the door of my bedroom was standing open, and I went through it and back to the dining room, as I had done the first time. I felt very uncomfortable, shaken and nervous, as you may well imagine, but there in the next room I knew my husband was sleeping, and my poor old aunt on the other side of the hall, and I plucked up my courage. I knew that he would never be afraid, of anything, man or—anything else, Mr. Canevin!

I FOUND that I must have been more upset than I had supposed, for the door out onto the small gallery from the dining room, where I had stood the other time, was unfastened, and half open, and I realized that I had left it in that condition, and I saw clearly that the young goat had simply wandered in. Goats and dogs and other animals roamed the streets there, even pigs, much as they do here, although all the islands have police regulations, and on St. Martin these were not enforced nearly as well as they are here on St. Croix. So I laughed at myself and my fears, although I think I had a right at least to be startled by that goat dancing about my bedroom table, and I fastened the door leading outside, and came back into my bedroom, and fastened that door too, and went back to bed once more. My last waking sensation was of that dog, or some other, howling, somewhere in the town.

Well, that was destined to be a bad night, Mr. Canevin. I remember one of my husband's sermons, Mr. Canevin, on the text: 'A Good Day.' I do not remember what portion of the Scriptures it comes from, but I remember the text, and the sermon too. Afterward, it occurred to me that that night, that 'bad night,' was the direct opposite; a mere whimsy of mine, but I always think of that night as 'the bad night,' somehow.

For, Mr. Canevin, that was not all. No. I had noticed the time before I returned to bed on that occasion, and it was a little past one o'clock. I had slept for an hour, you see, after the first interruption.

When I was awakened again it was five o'clock in the morning. Remember, I had, deliberately, and in a state of full wakefulness, closed and fastened both the door from that side gallery into the dining room, and the bedroom door. The jalousies had not been touched at any time, and all of them were fastened.

I awoke with the most terrible impression of evil and horror: it was as though I stood alone in the midst of a hostile world, bent upon my destruction. It was the most dreadful feeling—a feeling of complete, of unrecoverable, depression.

And there, coming through my bedroom door—through the door, Mr. Canevin, which remained shut and locked—was Armand Dubois. He was a tall, slim man, and he stalked in, looking taller and slimmer than ever, because he was wearing one of those old-fashioned, long, white night-shirts, which fell to his ankles. He walked, as I say, through the closed door, and straight toward me, and, Mr. Canevin, the expression on his face was the expression of one of the demons from hell.

I half sat up, utterly horrified, incapable of speech, or even of thought beyond that numbing horror, and as I sat up, Armand Dubois seemed to pause. His advance slowed abruptly, the expression of malignant hatred seemed to become intensified, and then he slowly turned to his left, and, keeping his face turned toward me, walked, very slowly now straight through the side wall of my bedroom, and was gone, Mr. Canevin.

Then I screamed, again and again, and Placide, my husband, bursting the door, rushed in, and over his shoulder and through the broken door I could see Julie's terrified face, and my poor old aunt, a Shetland shawl huddled about her poor shoulders, coming gropingly out of her bedroom.

THAT was the last I remembered then. When I came to, it was broad daylight and past seven, and Dr. Duchesne was there, holding his fingers against my wrist, counting the pulse, I suppose, and there was a strong taste of brandy in my mouth.

They made me stay in bed all through the morning, and Dr. Duchesne would not allow me to talk. I had wanted to tell Placide and him all that had happened to me through the night, but at two o'clock in the afternoon, when I was allowed to get up at last, after having eaten some broth, I had had time to think, and I never mentioned what I had heard and seen that night.

No, Mr. Canevin, my dear husband never heard it, never knew what had cast me into that condition of 'nerves.' After he died I told Dr. Duchesne, and Dr. Duchesne made no particular comment. Like all doctors, and the clergy here in the West Indies, such matters were an old story to him!

It was fortunate for us that he happened to be passing the house and came in because he saw the lights, and could hear Julie weeping hysterically. He realized that something extraordinary had happened, or was happening, in the rectory, and that he might be needed.

He was on his way home from the residence of Armand Dubois, there in the town. Dubois had been attacked by some obscure tropical fever, just before midnight, and had died at five o'clock that morning, Mr. Canevin.

Dr. Duchesne told me, later, about Dubois's case, which interested him very much from his professional viewpoint. Dr. Duchesne said that there were still strange fevers, not only in obscure places in the world, but right here in our civilized islands—think of it! He said that he could not tell so much as the name of the fever that had taken Dubois away. But he said the most puzzling of the symptoms was, that just at midnight Dubois had fallen into a state of coma—unconsciousness, you know—which had lasted only a minute or two; quite extraordinary, the doctor said, and that a little later, soon after one o'clock, he had shut his eyes, and quieted down—he had been raving, muttering and tossing about, as fever patients do, you know, and that there had come over his face the most wicked and dreadful grimace, and that he had drummed with his fingers against his own forehead, an irregular kind of drumming, a beat, the doctor said, not unlike the scampering footfalls of some small, four-footed animal...

He died, as I told you, at five, quite suddenly, and Dr. Duchesne said that just as he was going there came over his face the most horrible, the most malignant expression that he had ever seen. He said it caused him to shudder, although he knew, of course, that it was only the muscles of the man's face contracting—rigor mortis, it is called, I think, Mr. Canevin.

Dr. Duchesne said, too, that there was a scientific word which described the situation—that is, the possible connection between Dubois as he lay dying with that queer fever, and the appearances to me. It was not 'telepathy,' Mr. Canevin, of that I am certain. I wish I could remember the word, but I fear it has escaped my poor old memory!

'Was it "projection"?' I asked Mrs. Du Chaillu.

'I think that was it, Mr. Canevin,' said Mrs. Du Chaillu, and nodded her head at me, wisely.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.