RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

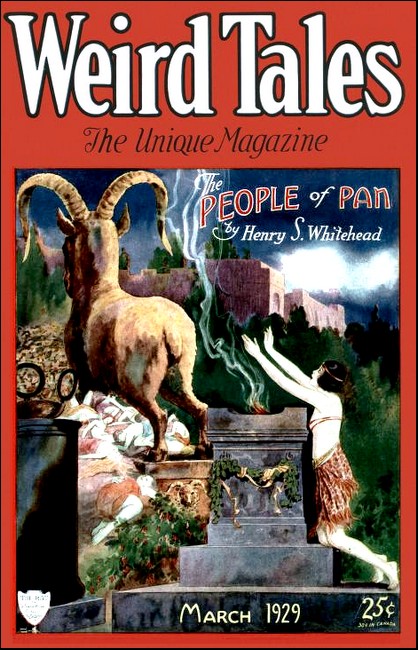

Weird Tales, March 1929, with "The People of Pan"

"She poured out upon the altar a thin stream of golden-colored oil."

Under the surface of a West Indian island Canevin found a

strange people who worshipped Pan—then the catstrophe.

I, GERALD CANEVIN of Santa Cruz, have actually been down the ladder of thirteen hundred and twenty-six steps set into the masonry of the Great Cylinder of Saona; have marveled at the vast cathedral underground on that tropical island; have trembled under the menacing Horns of the Goat.

That this island, comparable in area with my own Santa Cruz, and lying as it does only an overnight's sail from Porto Rico's metropolis, San Juan, quite near the coast of Santo Domingo, and skirted almost daily by the vessels of the vast Caribbean trade—that such an island should have remained unexplored until our own day is, to me, the greatest of its many marvels. Through his discovery, Grosvenor is today the world's richest man.

How, under these conditions, it could have been inhabited by a cultured race for centuries, is not hard, however, to understand. The cylinder—but the reader will see that for himself; I must not anticipate. I would note that the insect life has been completely re-established since Grosvenor's well-nigh incredible adventure there. I can testify! I received my first (and only) centipede bite while on Saona with Grosvenor, from whose lips I obtained the extraordinary tale which follows...

'BUT,' protested Grosvenor, 'how about the lighthouse? Isn't there anybody there? Of course, I'm not questioning your word, Mr. Lopez!'

'Automatic light.' The Insular Line agent spoke crisply. 'Even the birds avoid Saona! Here—ask Hansen. Come here, will you, Captain?'

Captain Hansen of the company's ship Madeleine came to the desk. 'Vot iss it?' he asked, steely blue eyes taking in Charles Grosvenor.

'Tell Mr. Grosvenor about Saona, Captain. You pass it twice a week on your run to Santo Domingo. I won't say a word. You tell him!'

Captain Hansen lowered his bulk carefully into an office chair.

'It iss a funny place, Saona. Me, I'm neffer ashore there. Nothing to go ashore for. Flat, it iss; covered down to de beach with mahogany trees—millions of mahogany trees. Nodding else—only beach. On one end, a liddle peninsula, and de automatic light. Nobody iss dere. De Dominican gofferment sends a boat vunce a month with oil for de light. Dat's all I could tell you—trees, sand, a dead leffel; nobody dere.'

The captain paused to light a long black cigar.

Grosvenor broke a silence. 'I have to go there, Captain. I am agent for a company which has bought a mahogany-cutting concession from the Dominican government. I have to look the place over—make a survey. Mr. Lopez suggests that you put me ashore there on the beach.'

'Goot! Any time you made de arrangement here in de office, I put you on shore dere, and—I'll go ashore with you! In all de Seffen Seas neffer yet did I meet a man had been ashore on Saona. I t'ink dat yoost happens so. Dere iss noddings to go ashore for; so, efferybody sails past Saona.'

The captain rose, saluted the agent and Grosvenor gravely, and moved majestically toward the narrow stairs which led to the blazing sidewalk of San Juan below.

IT required two weeks in mañana-land for Grosvenor to assemble his outfit for the sojourn on Saona. He was fortunate in discovering, out of work and looking for a job, a Barbadian negro who spoke English—the ancient island tongue of the buccaneers—and who labored under the name of Christian Fabio. Christian had been a ship's steward. He could cook, and like most Barbadians had some education and preferred long, polysyllabic words.

The Madeleine sailed out of San Juan promptly at three one blazing afternoon, with Grosvenor and Christian aboard.

Grosvenor had asked to be called at six, and when he came on deck the next morning the land off the Madeleine's starboard side was the shore of Saona. The Madeleine skirted this low-lying shore for several hours, and Grosvenor, on the bridge deck, scanned the island with the captain's Zeiss glass. He saw one dense mass of mahogany trees, dwarfed by perspective, appearing little more impressive than bushes.

At eight bells Captain Hansen rang for half-speed, and brought the Madeleine to anchor off a small bay skirted by a crescent of coconut palms. Greensward indicated the mouth of a fresh-water stream, and for this point in the bay Captain Hansen steered the ship's boat, in which he accompanied Grosvenor and Christian ashore. They were followed by another and larger boat, loaded to the gunwales with their supplies.

The trees, seen now close at hand, were much larger than they had appeared from the ship's deck. A fortune in hardwood stood there, untouched it seemed for centuries, ready for the cutting.

As soon as the stores were unloaded, Captain Hansen shook hands gravely with Grosvenor, was rowed back to his ship, and the Madeleine was immediately got under weigh and proceeded on her voyage. Long before the taint of her smoke had faded into nothingness in the blazing glare of the tropic sun, the two marooned inhabitants of Saona had pitched their tents and were settled into the task of establishing themselves for several weeks' sojourn.

GROSVENOR started his explorations the next morning. His map of the island was somewhat sketchy. It did not show the slight rise toward the island's center which had been perceptible even from shipboard. Grosvenor's kit included an aluminum surveyor's transit, a thermos-flask of potato soup—one of the best of tropical foods—and the inevitable mosquito-net for the noon siesta.

He started along the line of the stream, straight inland. He was soon out of sight and hearing of his camp in a silence unbroken by so much as the hum of an insect. He found the trees farther inland, in the rich soil of centuries of undisturbed leafage, better grown than those nearer the sea. As they increased in size, the sun's heat diminished.

Grosvenor walked along slowly. The stream, as he had expected, narrowed and deepened after a few rods of travel, and even a short distance inland, rinsing out his mouth with an aluminum cupful of the water, he found it surprisingly cool. This indicated shelter for a great distance and that the island must be very heavily forested.

A quarter of a mile inland he set up his transit, laid out a square and counted the trees within it. The density of the wood was seventeen per cent greater than what the company had estimated upon. He whistled to himself with satisfaction. This promised a favorable report. He continued his walk inland.

Four times he laid out a similar square, counted the trees, measured the circumference of their bases a little above the ground, estimated their average height. The wood-area became steadily denser.

At twelve-thirty he stopped for lunch and a couple of hours' rest. It would take him less time to walk back because he would not have to stop to lay out his squares.

He drank his potato soup, ate two small sandwiches of sharp Porto Rico sausage, and boiled a cupful of the stream water over a sterno apparatus for tea.

Then he stretched himself out on the long grass of the stream's bank under his mosquito-netting. He drifted easily into sleep, to the accompaniment of the stream's small rustlings and the sough of the trade wind through the millions of small mahogany leaves.

He awakened, two hours later, a sense of foreboding heavily upon him. It was as though something weird and strange had been going on for some time—something of which he was, somehow, dimly conscious. As he started, uneasily, to throw off the net and get up, he noticed with surprise that there were no mosquitoes on the net's outer surface. Then he remembered Captain Hansen's remarks about the dearth of animal life on the island. There was rarely even a seagull, the captain had said, along the island's shore. Grosvenor recalled that he had not seen so much as an insect during his five hours on the trail. He threw off the net and rose to his feet.

The vague sense of something obscurely amiss with which he had awakened remained. He looked curiously about him. He listened, carefully. All was silent except for the dying breath of the trade wind.

Then, all at once, he realized that he was missing the sound of the little stream. He stepped toward it and saw that the water had sunk to a mere trickle. He sat down near the low bank and looked at it. There were the marks of the water, more than a foot higher than its present level.

He glanced at his watch. It was three-thirteen. He had slept for two hours, exactly as he had intended. He might have slept the clock around! Even so, twenty-six hours would hardly account for a drop like this. He wound his watch—seven and one-half twists. It was the same day! He looked at the water again. It was dropping almost visibly, like watching the hour-hand of a huge clock at close range. He stuck a twig at its present level, and started to roll up his net and gather his belongings into a pack. That finished, he lit a cigarette.

He smoked the cigarette out and went to look at his twig. The water was half an inch below it. The many slight sounds which make up the note of a brook were muted now; the little trickle of water gave off no sound.

Greatly puzzled, Grosvenor shouldered his pack and started back to camp.

The walk occupied an hour and a quarter. The water grew lower as he went downstream. Before he reached the edge of the mahogany forest it had dwindled into a shallow bit of fenland. At the edge of the coral sand it was quite dry. He found Christian getting supper and bubbling over with long words which emerged out of a puzzled countenance.

'Doubtless you have remarked the diminution of the stream,' began Christian. 'I was fortunate enough to observe its cessation two hours ago and I have filled various vessels with water. It will constitute a very serious menace to our comfort, sir, if we are deprived of water. We might signal the Madeleine on her return voyage tomorrow, but I fear that if the lowering of the stream is permanent we shall be obliged to ration ourselves as to ablutions!'

Having delivered this masterpiece, Christian fell silent.

WHEN Grosvenor arose the next morning the stream was at the same level as on the previous morning. It was as though this stream were subject to a twenty-four-hour tide. There was no means of judging now whether this were the case, or whether some cataclysm of nature at the stream's source had affected it in this extraordinary way. Grosvenor's instinct was all for another trip upstream to the source to find out what he could.

He made more of his tree-tests that morning, and after lunch the stream began to fail again. The following morning it was once more at its high level. That day Grosvenor put his wish into execution. He had plenty of time for his surveys. He would go exploring on his own account today. He started after breakfast, taking only the materials for lunch this time. The mosquito-netting had proved to be useless. There were no mosquitoes!

At nine he reached the spot where he had taken the first siesta. He proceeded upstream, and half an hour later the ground began to rise. The stream shallowed and broadened. The trees in this moist area grew larger than any others he had seen on the island.

His pedometer informed him he was getting close to the island's center. The ground now mounted steadily. He came to a kind of clearing, where the trees were sparse and great whitish ricks replaced the soft coral soil. Through these, the stream, now again narrow and deep, ran a tortuous way, winding about the great boulders. On this broken ground, without much shade, the sun poured in intolerable brilliance. He wiped the sweat from his face as he climbed the last rise to the island's summit.

As he topped the rise an abrupt change took place. One moment he had been picking his way through broken ground among rocks. The next he was standing on smooth stone. He paused, and looked about him. He was at the top.

At his feet lay a smooth, round lake, enclosed by a stone parapet. Beyond, a gentle slope, heavily forested, ran down to the distant sea on the island's other side.

He stooped down, rubbed his hand over the level surface of the stone. It was masonry.

All was silent about him; not even a dragon-fly disturbed the calm surface of the circular pool. No insect droned its fervid note in the clear, warm air.

Very quietly now, for he felt that the silence of this place must not be disturbed by any unnecessary sound, he started around the lake's circular rim. In twenty steps he had reached the source of the stream. Here the edge of masonry was cut into a U through which the water flowed silently out. He resumed his walk, and the circuit occupied fifteen minutes. He reached his starting-point, sat down on the warm rock-edge, and looked intently into the pool. It must be fed by deep, subterranean springs, he judged, and these springs, possibly, ebbed and flowed, a rhythm reflected in a rise and fall of the pool's surface; a consequent rise and fall in the water of the stream.

The sun was almost intolerably hot. He walked off to the nearest mahogany grove, pitched his camp in its deep shade, and sat down to wait till noon. Here he prepared lunch, ate it, and returned to the basin's rim.

The reservoir was several feet lower, the water now barely trickling through its outlet. He watched the waters sink, fascinated. He leaned over the edge of masonry and gazed into their still depths. A cloud passed over the sun, throwing the great pool into shade.

No bottom was visible. Down, down, his gaze traveled, and as he looked the rate of the sinking water-level increased and there arose from the pool a dim, hollow sound as some incalculable suction drew the waters down into the cylinder's depths.

An almost irresistible desire came over him to descend with the water. His scrutiny traveled about the inner surface of the great cylinder now revealed by the sinking waters.

What was that? Something, a vertical line, toward the other side, broke the cementlike smoothness of the chiseled surface. He started toward the point, his heart jumping as what he had vaguely suspected, hoped, became an actuality before his eyes. The vertical line was a ladder down the inner surface of the cylinder, of broad, copper-colored metal insets extending far down until he lost it in the unfathomable darkness below.

The ladder's topmost inset step was some three feet below the top. Looking closely from the rim above it, he observed semicircular ridges on the rim itself, handholds, obviously, shaped like the handles of a stone crock, cut deeply into the masonry. A thin, metal handrail of the same material as the steps ran down straight and true beside them.

The impulse to descend became overpowering. He muttered a brief, fragmentary prayer, and stooped down, clutching the stone handholds. He stepped over the rim and down inside, and felt for the topmost step of the ladder with his foot. The step, and the railing, as he closed a firm right hand about it, felt slippery. But steps and rail were rigid, firmly set as though installed the day before. The metal showed no corrosion.

With a deep breath, he took one last look at the tops of the mahogany trees and began to go down the ladder.

At first he felt carefully for each succeeding step, clutched the unyielding handrail grimly, as the dank coolness of the stone cylinder closed in around him. Then, with custom, his first nervous vigilance relaxed. The steps were at precisely regular intervals; the handrail firm. He descended beyond the penetrating light of the first fifty feet into a region of increasing coolness and dimness.

When he reached the two hundredth step, he paused, resting, and looked down. Only a vague, imponderable dimness, a suggestion of infinite depth, was revealed to him. He turned his head about and looked up. A clear blue, exact circle stood out. Within it he saw the stars.

He descended another hundred steps, and now all was black about him. The blue circle above had turned darker. The stars glowed brilliantly.

He felt no fear. He had steady nerves, fortitude, a fatalistic faith in something he named his destiny. If harm were to come to him, it would come, here or anywhere alse. He reasoned that the water would not rise for many hours. In that blackness he resumed his descent. He went down and down, step after interminable step....

It was wholly dark now. The circle above was only the size of a small coin, the stars indistinguishable; only their flickering brightness over the surface of the tiny disk.

He had counted 1,326 steps when something happened to his left foot. He could not lower it from the step on which it rested. The very edge of a shadow of cold fear fell upon him, but resolutely he put it away. He lowered his right foot to the same step, and, resting his body's weight on the left foot attempted to lower the right. He could not!

Then it dawned upon him that he had reached the bottom of the ladder. Holding firmly to the rail with his left hand he reached for his flashlight with the other. By its light he looked about him. His feet were on a metal platform some twelve feet square. Just to his left, leading into the wall of the cylinder, was the outline of a lancet-shaped doorway. A great ring hung on a hinged knob near his hand.

He stepped out upon the platform, his muscles feeling strange after the long and unaccustomed strain of the descent. He took hold of the door-ring, twisted it to the left. It turned in his hand. He pulled, and a beam of light, soft and mellow, came through the vertical crack. He pulled the door half-open, and the soft light flooded the platform. He stepped over to its edge and looked down, leaning on the metal handrail which ran about the edge. Blackness there—sheer, utter blackness.

He turned again to the door. He had not come thus far to yield to misgivings as to what might lie behind it. He slipped through the opening and pulled the door to behind him. It shut, true and exactly flush with its surrounding walls and jambs, solidly.

He stood in a small, square room, of the same smooth masonry as the cylinder, floored with sheets of the coppery metal. The light came through from another doorway, open opposite the side where he stood. Resolutely he crossed the small room and looked through the door.

Vast space—a cathedral—was the first, breath-taking impression. Far above, a vast, vaulted arch of masonry. In the dim distance towered an amazing figure, so incredible that Grosvenor let out his breath in a long sigh and sat down weakly on the smooth floor.

The figure was that of an enormous goat, reared on a pair of colossal legs, the lowered head with sweeping horns pointing forward, some eighty feet in the air. About this astounding image hung such an air of menacing savagery that Grosvenor, weary with his long descent, covered his face with his hands to shut it out. He was aroused out of his momentary let-down by a sound.

He sat up, listened. It was a kind of faint, distant chanting. Suppressing a shudder he looked again toward the overpowering majesty of the colossus. A great concourse of people, dwarfed by the distance, danced rhythmically before the gigantic idol. The chant rose higher in measured cadence. Fascinated, Grosvenor rose and walked toward the distant dancers.

WHEN he had traversed half the space between, the image took on a dignity not apparent from the greater distance. The craggy, bestial face was now benevolent, as it looked down upon its devotees. There was a grotesque air of benediction about the flare of the forehoofs as they seemed to wave in grave encouragement to the worshipers beneath. The attention of the throng was so occupied with their dance that Grosvenor remained unobserved. Clouds of incense rose before the image, making the head appear to nod, the forelegs to wave gravely.

Something more than its cadence seemed now to mingle with the chanting. There was something oddly familiar about it, and Grosvenor knitted his brows in the effort to place it. Then it came to him all at once. It was the words of the ancient Greek Chorus. Nearer and nearer he approached, his feet making no sound on the dull, russet-colored, metal flooring. It was like walking on solid lead. He stooped, at this thought, and with his sheath-knife scratched its surface, dulled with the wear of countless feet. A thin, wirelike splinter curled behind his scratching knife-point. It was bright yellow on the fresh surface. He tore the splinter loose, held it close. It was soft, like lead—virgin gold.

He placed the sliver in his jacket pocket and stood, dumfounded, his heart pounding tumultuously. Gold!...

The chanting ceased. A clear, woman's voice detached itself; was lifted in a paean—a hymn of praise. The words now came to him clear and full. He stopped dead, trying, straining all his faculties, to understand. The woman was singing in classical Greek!

Something of modern Greek he understood from a long professional sojourn in the Mediterranean island of Xante where once he had been employed by the owner of a group of currant-plantations, and where he had learned enough of the Italianized Greek of the island to make himself understood. He hastened forward, stopping quite near the rearmost worshipers. This was no dialect. This was Old Greek, Attic Greek, the tongue of Hellas, of classic days, as used to celebrate the Mysteries about the altars of Zeus and the Nature gods; in the Sacred Groves; at Elis, and Dodona, and before the shrines of Apollo—and in the worship of Pan. Pan!—the Goat. The beginnings of an understanding surged through his mind.

In the ancient tongue of Homer and Aeschylus, this recitative now began to take form in his mind. It was, he soon perceived, a hymn to Pan, to the patron god of woodlands and wild places; of glades and streams and hidden groves; of nymphs and dryads....

The people swayed to the cadences of the hymn, and at intervals the vast throng breathed out a few rhythmical words, a hushed, muted chorus, in which were recited the Attributes of Pan....

Grosvenor found himself swaying with them, the notes of the chorus somehow strangely familiar to him, as though remembered after a great interval, although he knew that he had never before in this life heard anything like this. He approached nearer, without concealment now, mingled with the multitude pouring out its corporate soul to the god of Nature.

The hymn ended. Then, to a thin, piping note—the note of a syrinx—and with no confusion, a dance began. Grosvenor danced naturally with a group of four, and the others, in a kind of gentle ecstasy, danced with him, a dance as old as trees and hills, the worship of the Great Powers which through the dignity and grace of the dance seemed to promise strange and unknown joys....

The dance ended, abruptly, on a note of the pan-pipes. Grosvenor, brought to himself, glanced quickly about him. He was conspicuous. The others were uniformly dressed in blue kirtles, sandals on their graceful feet. The people were very beautiful. Grace and dignity marked their every movement.

Behind the colossal image of the Goat a great recess was set off by an arch which towered aloft out of sight. Here stood an altar, about whose upper edge ran cameo-like figures: youths and girls bearing wreaths; garlanded oxen; children with torches; and, centrally placed, the grotesque figure of Pan with his goat's legs and small, crooked horns upon his forehead—Pan seated, his pipes at his lips.

Suddenly every eye turned to the altar.

There came from a recess a woman, tall and graceful, bearing in her hands a slender vase of white stone. From this, on reaching the altar, she poured out upon it a thin stream of golden-colored oil. An intense, reddish flame arose at once. The vast audience stood motionless.

Then a note on the pipe, and from the throng, quite close to Grosvenor, a young man stepped, and mounted broad, shallow steps to the altar. In his hand he carried a live beetle held delicately by the edge of elevated wings. Straight to the altar he proceeded and dropped the insect in the center of the flame. So silent was the motionless throng that the crackle of the flame devouring this inconsiderable offering was plainly heard. Bowing to the priestess, the young man returned to his place.

A sigh, such as proceeds from a large concourse of people who have been keeping silence, now arose from the throng, which forthwith broke up into conversing groups.

Then the first intimation of fear fell upon Grosvenor like a black mantle. For the first time since his arrival among this incredible company, a quarter of a mile underneath the surface of an 'uninhabited' West Indian island, he took sudden thought for his safety. It was late in the day to think of that! He was surrounded by these people, had intruded into their worship, a worship ancient when the Classics were composed. He was effectually cut off from any chance of escape, should they prove hostile. He saw a thickening group closing in about him—curious, incredulous, utterly taken by surprise at discovering this stranger in their midst....

BY a great effort, and in a voice hardly more than a whisper—for his danger had made itself overwhelmingly apparent to him—he spoke in his best attempt at pure Greek.

'I give you greeting, in the name of Pan!' he said.

'And to you, greeting, O barbarian,' replied a deep and rich voice behind him.

The throng about him stirred—a movement of deference. He turned. The graceful priestess stood close to him. He bowed, prompted by an instinct for 'good manners.'

The priestess made a graceful inclination before him. Instinct prompted him a second time. He addressed her.

'I come to you in love and peace.' It was a phrase he had gathered from the hymn to Pan—that phrase 'love and peace.' He continued: 'I have sojourned in the Land of Hellas, the home of the great Pan, though no Hellene, as my speech declares.'

'Sojourn here, then, with Pan's people in love and peace,' returned the priestess with commanding dignity. She made him a summoning gesture.

'Come,' she said, and, turning, led the way back toward the altar.

He followed, into the blackening gloom of the sanctuary, and straight before him walked his conductress without so much as a glance right or left. They passed at last between two enormous curtains screening an aperture, and Grosvenor found himself in a very beautiful room, square, and unmistakably Greek in its appointments. Two long couches stood at each side, along the walls. In the center a chased, rectangular table held a great vase of the yellow metal, heaped with pomegranates.

The priestess, pausing, motioned him gracefully to one of the seats, and reclined opposite him upon the other.

She clapped her hands, and a beautiful child ran into the room. After a round-eyed glance at the stranger, he stood before the priestess, who spoke rapidly to him. He left the room, and almost immediately returned with a vase and two small goblets of the ruddy gold. The drink proved to be pomegranate-juice mingled with cold water. Grosvenor found it very refreshing.

When they had drunk, the priestess began at once to speak to him.

'From where do you come, O barbarian?'

'From a region of cold climate, in the north, on the mainland.'

'You are not, then, of Hispaniola?'

'No. My countrymen are named "Americans." In my childhood my countrymen made war upon those of Hispaniola, driving them from a great island toward the lowering sun from this place, and which men name "Cuba."'

The priestess appeared impressed. She continued her questioning.

'Why are you here among the People of Pan?'

Grosvenor explained his mission to the island of Saona, and, as well as his limited knowledge of Greek permitted, recounted the course of his adventure to the present time. When he had finished: 'I understand you well,' said the priestess. 'Within man's memory none have been, save us of the People of Pan, upon this island's surface. I understand you are the forerunner of others, those who come to take of the wood of the surface. Are all your fellow-countrymen worshippers of Pan?'

Grosvenor was stuck! But his sense of humor came to his rescue and made an answer possible.

'We have a growing "cultus" of Pan and his worship,' he answered gravely. 'Much in our life comes from the same source as yours, and in spirit many of us follow Pan. This following grows fast. The words for it in our tongue are "nature-study," "camping," "scouting," "golf," and there are many other varieties of the cult of Pan.'

The priestess nodded.

'Again, I understand,' she vouchsafed. She leaned her beautiful head upon her hand and thought deeply.

It was Grosvenor who broke a long silence. 'Am I permitted to to make enquiries of you?' he asked.

'Ask!' commanded the priestess.

Grosvenor enquired about the rise and fall of the water in the great cylinder; the origin of the cylinder itself: was the metal of which the floors and steps and handrail were made common? Where did the People of Pan get the air they breathe; How long had they been here, a quarter of a mile beneath the earth's surface? On what kind of food did they live? How could fruit—he indicated the pomegranates—grow here in the bowels of the earth?

He stopped for sheer lack of breath. Again the priestess smiled, though gravely.

'Your questions are those of a man of knowledge, although you are an outlander. We are Hellenes and here we have lived always. All of us and our fathers and fathers' fathers were born here. But our tradition teaches us that in the years behind the years, in the very ancient past, in an era so remote that the earth's waters were in a different relation to the land, a frightful cataclysm overwhelmed our mother-continent, Antillea. That whole land sank into the sea, save only one Deucalion and his woman, one Pyrrha, and these from Atlantis, the sister continent in the North. These, so the legend relates, floated upon the waters in a vessel prepared for them with much food and drink, and these having reached the Great Land, their seed became the Hellenes.

'Our forebears dwelt in a colony of our mother continent, which men name Yucatan, a peninsula. There came upon our forebears men of warlike habit, men fierce and cruel, from a land adjacent to Hellas, named "Hispaniola." These interlopers drove out our people who had for eons followed the paths of love and peace; of flocks and herds; of song and the dance, and the love of fields and forest and grove, and the worship of Pan. Some of our people they slew and some they enslaved, and these destroyed themselves.

'But among our forebears, during this persecution, was a wise man, one Anaxagoras, and with him fled a colony to the great island in the South which lies near this island. There they settled and there would have carried on our worship and our ways of peace. But here they of Hispaniola likewise came, and would not permit our people to abide in peace and love.

'Then were our people indeed desperate. By night they fled on rafts and reached this low-lying place. Here they discovered the cylinder, and certain ones, greatly daring, cast themselves on the mercy of Pan and descended while the waters were sunken.

'Here, then, we have dwelt since that time, in peace and love.

'We know not why the waters fall and rise, but our philosophers tell us of great reservoirs far beneath the platform where man's foot had not stepped. In these, as the planet revolves, there is oscillation, and thus the waters flow and ebb once in the day and not twice as does the salt sea.

'We believe that in times past, beyond the power of man to measure or compute, the dwellers of these islands, which then were mountaintops, ere the submersion of Antillea and its sister continent Atlantis, caused the waters of the sea to rise upon them, and whose descendants those of Hispaniola did name "Carib" were men of skill and knowledge in mighty works, and that these men, like one Archimedes of the later Hellas, did plan to restore the earth's axis to its center, for this planet revolves not evenly but slantwise, as they who study the stars know well. We believe that it was those mighty men of learning and skill who built the cylinder.

'Vessels and the metal of the floor were here when we came, and this metal, being soft and of no difficulty in the craftsman's trade, we have used to replace the vessels as time destroys them and they wear thin. This metal, in vast quantities, surrounds our halls and vaults here below the surface of the land above.

'Our light is constant. It is of the gases which flow constantly from the bowels of the earth. Spouts confine it, fire placed at the mouths of the spouts ignites it. The spouts, of this metal, are very ancient. Upon their mouths are coverings which are taken away when fire is set there; replaced when the light is needed no more in that place.

'Our air we receive from shaft-ways from the surface of the earth above. Their ground openings are among the white rocks. Our philosophers think the yellow metal was melted by the earth's fires and forced up through certain of the ancient air-openings from below.'

The priestess finished her long recital, Grosvenor listening with all his faculties in order to understand her placid speech.

'I understand it all except the fruit,' said he.

The priestess smiled again, gravely.

'The marvels of nature make no difficulty for your mind, but this simple question of fruit is difficult for you! Come—I will show you our gardens.'

SHE rose; Grosvenor followed. They passed out through various chambers until they arrived at one whose outer wall was only a balustrade of white stone. An extraordinary sight met Grosvenor's eyes.

On a level piece of ground of many acres grew innumerable fruits: pineapples, mango-trees, oranges, pomegranates. Here were row upon row of sapodilla trees, yam-vines, egg-plants, bananas, lemon and grapefruit trees, even trellises of pale green wine-grapes.

At irregular intervals stood metal pipes of varying thickness and height, and from the tops of these, even, whitish flares of burning gas illuminated the 'gardens.' A dozen questions rose in Grosvenor's mind. 'How? Why?'

'What causes your failure to understand?' enquired the priestess, gently. 'Heat, light, moisture, good earth well tended! Here, all these are present. These fruits are planted from long ago, and constantly renewed; originally they grew on the earth's surface.'

They walked back through the rooms to the accompaniment of courteous inclinations from all whom they passed. They resumed their places in the first room. The priestess addressed Grosvenor.

'Many others will follow you; those who come to procure the wood of the forest above. Nothing we have is of any value to these people. Nothing they may bring do we desire. It would be well if they came and took their wood and departed knowing naught of us of the People of Pan here underground.

'We shall, therefore, make it impossible for them to descend should they desire so to do. We shall cut the topmost steps of the ladder away from the stone; replace them when your countrymen who drove the people of Hispaniola from Cuba have departed. I will ask you to swear by Pan that you will reveal nothing of what you have seen. Then remain with us if you so desire, and, when your countrymen have departed, come again in peace and love as behooveth a devotee of Pan.'

'I will swear by Pan, as you desire,' responded Grosvenor, his mind on the incalculable fortune in virgin gold which had here no value beyond that of its utility for vessels, and floors, and steps! Indeed he needed no oath to prevent his saying anything to his 'countrymen!' He might be trusted for that without an oath! A sudden idea struck him.

'The sacrifice,' said he,—'the thurìa, or rather, I should say, the holokautóma—the burnt offering. Why was only an insect sacrificed to Pan?'

The priestess looked down at the burnished metal floor of the room and was silent. And as she spoke, Grosvenor saw tears standing in her eyes.

'The sinking and rise of the waters is not the only rhythm of this place. Four times each year the gases flow from within the earth. Then—every living thing upon this island's surface dies! At such seasons we here below are safe. Thus it happens that we have no beast worthy of an offering to Pan. Thus, at our festivals we may offer only inferior things. We eat no flesh. That is sacred to Pan, as it has been since our ancestors worshipped Him in the groves of Yucatan. That He may have His offering one or more of us journeys to the cylinder's top at full moon. Some form of life has always been found by diligent search. Somewhere some small creature survives. If we should not discover it, He would be angry, and, perhaps, slay us. We know not.'

'When does the gas flow upward again?' enquired Grosvenor. He was thinking of Christian Fabio waiting for him there on the beach.

'At the turning of the season. It seethes upward in three days from now.'

'Let me take my oath, then,' replied Grosvenor, 'and depart forthwith. Then I would speak concerning what I am to do with those others who follow me to this land.'

The priestess clapped her hands, and the little serving-lad entered. To him she gave a brief order, and he took his departure. Then with the priestess Grosvenor made his arrangement about the woodcutting force—a conversation which occupied perhaps a quarter of an hour. The little messenger returned as they were finishing. He bowed, spoke rapidly to the priestess, and retired.

'Rise, and follow me,' she directed Grosvenor.

Before the great idol the people were again gathering when they arrived beside the altar. They stood, and the priestess held out her arms in a sweeping gesture, commanding silence. An imponderable quiet followed.

His hands beneath hers on the altar of Pan, Grosvenor took his oath as she indicated it to him.

'By the great Pan, I swear—by hill and stream, by mountain and valley, by the air of the sky and the water of streams and ponds, by the sea and by fire which consumes all things—by these I swear to hold inviolate within me that which I have known here in this temple and among the People of Pan. And may He pursue me with His vengeance if I break this my oath, in this world and in the world to come, until water ceaseth to flow, earth to support the trees, air to be breathed, and fire to burn—by these and by the Horns and Hooves of Pan I swear, and I will not break my oath.'

Then, conducted by the priestess, Grosvenor walked through the people, who made a path for them, across the great expanse of the temple to the small anteroom beside the cylinder. Here the priestess placed her hands upon Grosvenor's head. 'I bless thee, in Pan's name,' she said, simply. He opened the door, passed through onto the metal platform, and pushed it shut behind him....

HE found the ascent very wearing and his muscles ached severely before he could discern clearly the stars flaming in the disk above his head. At last he grasped the stone handles on the rim. Wearily he drew himself above ground, and stretched himself upon the level rim of the cylinder.

Before starting down the gentle slope for his camp under the shade of the mahogany forest's abundant leafage, he paused beside one of the white rocks, laboriously heaving it to one side. Beneath it was an aperture, running straight down, and lined with a curiously smooth, lavalike stone. He had seen one of the air-pipes which the priestess had described. He knew now that he had not been passing through some incredibly strange dream. He stepped away and was soon within the forest's grateful shade.

He reached camp and Christian Fabio a little before seven-thirty that evening, finding supper ready and the faithful Christian agog for news. This he proffered in Christian's kind of language, ending by the statement that the stream 'originated in a lake of indubitably prehistoric volcanic origin possessing superficial undulatory siphonage germane to seismic disturbance.'

Christian, pop-eyed at this unexpected exhibition of learning on his master's part, remarked only: 'How very extraordinary!' and thereafter maintained an awed silence.

The next day Grosvenor signaled the Madeleine, on her return trip, and taking Christian with him, returned to San Juan 'for certain necessary supplies which had been overlooked.'

From there he sent the company a long letter in which he enlarged on the danger of the periodic gas-escape and gave a favorable report on the island's forestation. He discharged Christian with a recommendation and a liberal bonus. Then he returned to Saona alone and completed his month's survey, doing his own cooking, and sleeping with no attention to non-existent insects. He did not visit the island's center again. He wished to expedite the woodcutting in every possible way, and disliked the loss of even a day.

The survey completed—in three weeks—he went back to San Juan, cabled his full report, and was at once instructed to assemble his gang and begin.

Within another month, despite the wails of 'mañana'—tomorrow—a village, with himself as lawmaker, guide, philosopher, friend, and boss, was established on Saona. Cooks, camp roustabouts, wood-cutters, and the paraphernalia of an American enterprise established themselves as though by magic, and the cutting began. Only trees in excess of a certain girth were to be taken down.

By almost superhuman efforts on Grosvenor's part, the entire job was finished well within the three-month period. Three days before the exact date when the gas was to be expected, every trace of the village except the space it had occupied was gone, and not a person was left on Saona's surface. The great collection of mahogany he had made he took, beginning a week later, by tugboat to San Juan, whence it was reshipped to New York and Boston, to Steinway, and Bristol and other boat-building centers; to Ohio to veneering plants; to Michigan to the enormous shops of the Greene and Postlewaithe Furniture Company.

Grosvenor's job was finished.

In response to his application to the company, he was granted a month's well-earned vacation, accompanied by a substantial bonus for his good work.

This time he did not travel by the Madeleine to Saona. Instead he took ship for Port-au-Prince, Haiti, thence by another vessel to Santo Domingo City; from that point, in a small, coastwise vessel, to San Pedro Macoris.

From Macoris, where he had quietly hired a small sailboat, he slipped away one moonless evening, alone. Thirty hours afterward, he reached Saona, and, making his boat fast in a small, landlocked inlet which he had discovered in the course of his surveys, and with a food-supply for two days, he walked along the beach half a mile to the mouth of the stream.

He followed the well-remembered path until he came to the edge of the woods. He had not brought his gang as far as this. There had been more than enough mahogany boles to satisfy the company without passing inland farther than the level ground.

He walked now, slowly, under the pouring sunlight of morning, across the broken ground to the cylinder's edge, and there, temporarily encamped, he waited until it began to sink. He watched it until it had gone down a dozen feet or more, and then walked around to the point where the ladder began.

The ladder was gone. Not so much as a mark in the smooth masonry indicated that there ever had been a ladder. Once more, with a sinking heart, he asked himself if his strange adventure had been a dream—a touch of sun, perhaps....

This was, dreams and sunstrokes apart, simply inexplicable. Twice, during the course of the woodcutting operations, the People of Pan had communicated with him, at a spot agreed upon between him and the priestess. Both times had been early in the operations. It was nearly three months since he had seen any concrete evidence of the People's existence. But, according to their agreement, the ladder-steps should have been replaced immediately after the last of his gang had left Saona. This, plainly, had not been done. Had the People of Pan, underground there, played him false? He could not bring himself to believe that; yet—there was no ladder; no possible means of communicating with them. He was as effectually cut off from them as though they had been moon-dwellers.

Grosvenor's last man had left the island three days before the season's change—September twenty-first. It was now late in October.

Ingress and egress, as he knew, had been maintained by a clever, simple arrangement. Just below ground-level a small hole had been bored through the rim, near the U-shaped opening. Through this a thin, tough cord had run to a strong, thin, climbing rope long enough to reach the topmost step remaining. He remembered this. Perhaps the people below had left this arrangement.

HE found the hole, pulled lightly on the string. The climbing-rope came to light. An ingenious system of a counter-pull string allowed the replacing of the climbing rope. Obviously the last person above ground from below had returned successfully, leaving everything shipshape here. To get down he would have to descend some thirty feet on this spindling rope to the topmost step. He tested the rope carefully. It was in good condition. There was no help for it. He must start down that way.

Very carefully he lowered himself hand over hand, his feet against the slippery inner surface of the stone cylinder. It was a ticklish job, but his fortitude sustained him. He found the step, and, holding the climbing-rope firmly, descended two more steps and groped for the handrail. He got it in his grasp, pulled the return-string until it was taut, then began the tedious descent, through its remembered stages of gradual darkening, the damp pressure of terrible depth upon the senses, the periodic glances at the lessening disk above, the strange glow of the stars...

At last he reached the platform, groped for the door-ring, drew open the door.

In the anteroom a terrible sense of foreboding shook him. The condition of the ladder might not be a misunderstanding. Something unforeseen, fearful, might have happened!

He pulled himself together, crossed the anteroom, looked in upon the vast temple.

A sense of physical emptiness bore down upon him. The illumination was as usual—that much was reassuring. Across the expanse the great idol reared its menacing bulk, the horned head menacingly lowered.

But before it bowed and swayed no thronged mass of worshippers. The temple was empty and silent.

Shaken, trembling, the sense of foreboding still weighing heavily upon him, he started toward the distant altar.

Soon his usual vigorous optimism came back to him. These had been unworthy fears! He looked about him as he proceeded, at the dun sidewalls rising, tier upon tier of vague masonry, up to the dim vault in the darkness above. Then the sense of evil sprang out again, and struck at his heart. His mouth went dry. He hastened his pace. He began to run.

As he approached the altar, something strange, something different, appeared before him. The line formed by the elevation of the chancel as it rose from the flooring, stone against dull, yellowish metal, a thousand paces ahead, should have been sharp and clear. Instead, it was blurred, uneven.

As he came nearer he saw that the statue's prancing legs were heaped about with piled stuff...

He ran on, waveringly, uncertain now. He did not want to see clearly what he suspected. He stumbled over something bulky. He stopped, turned to see what had lain in his way.

It was the body of a man, mummified—dry, leathery, brown; the blue kirtle grotesquely askew. He paused, reverently, and turned the body on its back. The expression on the face was quite peaceful, as though a natural and quiet death had overtaken the victim.

As he rose from his task, his face being near the floor's level, he saw, along it, innumerable other bodies lying about in varying postures. He stood upright and looked toward the image of the Goat. Bodies lay heaped in great mounds about the curved animal legs; more bodies lay heaped before the sanctuary.

Awestruck, but, now that he knew, something steadied by this wholesale calamity which had overtaken the peaceful People of Pan, he moved quietly forward at an even pace.

Something lay across the altar.

Picking his way carefully among the massed corpses he mounted the sanctuary steps. Across the altar lay the body of the priestess, her dead arms outstretched toward the image of the Goat. She had died in her appointed place, in the very attitude of making supplication for her people who had died about her. Grosvenor, greatly moved, looked closely into the once beautiful face. It was still strangely beautiful and placid, noble in death; and upon it was an expression of profound peace. Pan had taken his priestess and his people to Himself...

He had slightly raised the mummified body, and as he replaced it reverently back across the altar, something fluttered from it to his feet. He picked up a bit of parchment-like material. There was writing on it. Holding it, he passed back through the sanctuary to the room behind, where there would be a clearer light. The rooms were empty. Nothing had been disturbed.

The parchment was addressed to him. He spelled out, carefully, the antique, beautifully-formed characters of the old literary Greek.

Hail to thee, and farewell, O stranger. I, Clytemnestra, priestess of Pan the Merciful, address thee, that thou mayest understand. Thou art freed from thy oath of silence.

At the change of the seasons the sacrifice failed. Our search revealed no living thing to offer to our god. Pan takes His vengeance. My people abandon this life for Acheron, for upon us has Pan loosed the poisonous airs of the underworld. As I write, I faint, and I am the last to go.

Thine, then, O kind barbarian, of the seed of them that drove from Kuba the men of Hispaniola, are the treasures of Pan's People. Of them take freely. I go now to my appointed place, at the altar of the Great Pan who gathers us to Himself. In peace and love, O barbarian of the North Continent, I greet thee. In peace and love, farewell.

Grosvenor placed the parchment in his breast-pocket. He was profoundly affected. He sat for a long time on the white stone couch. At last he rose and passed reflectively out into the underground gardens. The great flares of natural gas burned steadily at the tops of the irregular pipes.

At once he was consumed in wonder. How could these continue to burn without there having occurred a great conflagration? The amount of free gas sufficient to asphyxiate and mummify the entire population of this underground community would have ignited in one heaving cataclysm which would have blown Saona out of the water!

But—perhaps that other gas was not inflammable. Then the true explanation occurred to him abruptly. The destructive gas was heavier than the air. It would lie along the ground, and be gradually dissipated as the fresh air from the pipes leading above diluted its deadly intensity. It would not mount to the tops of these illuminating pipes. The shortest of them, as he gaged it, was sixty feet high. Of course, he would never know, positively...

He looked about him through the lovely gardens, now his paradise. All about were the evidences of long neglect. Unshorn grass waved like standing hay in the light breeze which seemed to come from nowhere. Rotting fruit lay in heaps under the sapodilla trees.

He plucked a handful of drying grass as long as his arm, and began to twist it into the tough string of the Antilles' grass-rope. He made five or six feet of the string. He retraced his steps slowly back to the room where he had read his last message from the priestess of Pan. He passed the string through the handles of a massive golden fruit jar, emptied the liquefying mass of corrupt fruit which lay sodden in its bowl.

He slung the heavy jar on his back, returned through the sanctuary, threaded his way among the heaped bodies, began to walk back through the temple toward the anteroom.

From across that vast room he looked back. Through the dim perspective the monstrous figure of the Goat seemed to exult. With a slight shudder Charles Grosvenor passed out onto the platform. He grasped the handrail, planted his feet on the first round of the ladder, and began his long, weary climb to the top....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.