RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Strange Tales, January 1933, with "The Napier Limousine"

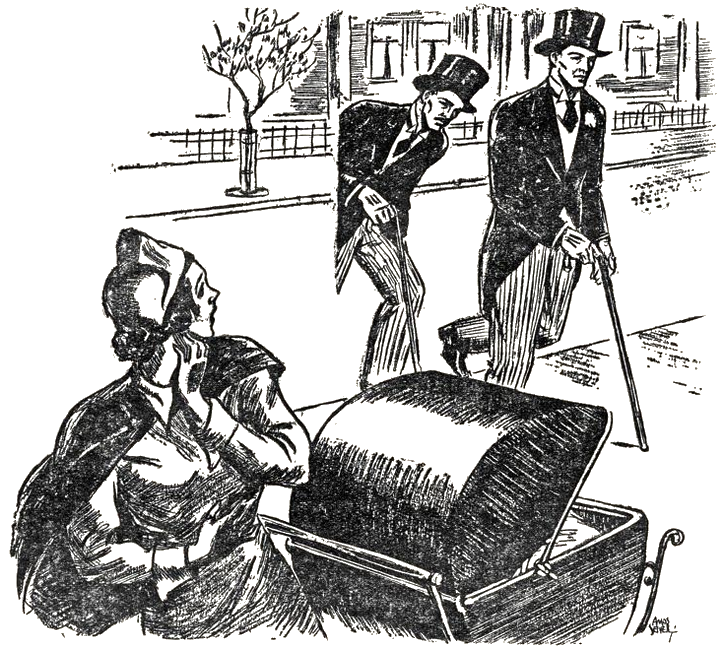

Out of the light comes the hand of Sir Harry's deliverance.

Two gentlemen, out of nowhere, suddenly stepped on the curb in front of her.

THE nursemaid let go the handle of her perambulator, froze into an appearance of devastated horror and screamed.

Just what there might be about the sight of two gentlemen, dressed formally for the morning, stepping out of an impeccable town-car upon the curbstone in front of No. 12, Portman Terrace—one of an ultraconservative long row of solid family mansions in London's residential West End—to throw their only beholder into such a state of sudden, horrified terror, was a mystery. What drove home the startling implication that there was something rather dreadfully wrong, made a benumbing little chill course devastatingly up and down my spine, was the fact that I was one of them. My companion was James Rand, Earl of Carruth, back in London now after twenty years' continuous service in India as Chief of the British Government's Secret Service and armed with an experience which might well have filled the measure of life for a dozen ordinary men.

The beautifully-kept limousine had stopped with a jarless pause like the alighting of a poised hawk. Portman Terrace was empty of pedestrians with the exception of the liveried, middle-aged, sensible-looking servant with her glistening custom-built perambulator.

For my own part, if I had been alone, I suppose I should have followed my instinct, stopped, and made some attempt to restore to a normal condition this stricken fellow human being, inexplicably seized in the ruthless grasp of cold fear. But it took more than the eccentricity of a casual nursemaid to upset Lord Carruth's iron self-control. My companion glanced appraisingly at this strange disturbance of the King's Peace and led the way up the high flight of marble steps to the front doorway of No. 12, his normal expression of facial placidity altered by no more than a raised eyebrow. Still under the compulsion of our determination to meet the emergency with which we had hastened here to cope, I followed him across the broad sidewalk and ran up the steps just behind him.

CARRUTH'S finger was already on the silver doorbell-button when I came up beside him, and this circumstance gave me my first occasion to turn and look behind me. I did so, at once, because it occurred to me that the very smart, gray-haired footman whom the car's owner had addressed as 'Baines', should have been there, pressing that button with an efficient black-gloved finger.

Below on the sidewalk the nursemaid was retreating as rapidly as she could walk, and, as she looked back over her shoulder, I saw that her apple cheeks had gone to a kind of oyster-gray, and that her terrified mouth hung open like a Greek tragic mask.

But the nursemaid, strange sight that she presented, got only a passing glance from me, for I brought my eyes around to the curb where we had alighted, a matter of seconds before, to see what had happened to the footman, Baines, who like any proper footman, should have been up the steps before us. It seemed inconceivable that such a man should be remiss in his duties and yet—

I brought my eyes around, I say, and looked down there, and—there was no Baines. Neither was there any driver beside the footman in the chauffeur's seat. There was no seat. There was no car! The limousine, an old-model Napier, was clean gone. The street in front of No. 12, Portman Terrace was entirely empty and deserted....

It is hard to set down in words how very serious a jar this discovery was. I knew that the car was still there before I turned around to look for Baines.

I knew that because I had not heard the inevitable slight sounds made in starting even by the most soundless of cars, under the ministrations of the most perfectly trained chauffeur such as ours had shown himself to be on our ride from in front of St. Paul's Cathedral to Portman Terrace.

There it was, that empty street; the agitated back of the rapidly retreating nursemaid receding into the distance; the car gone, chauffeur, footman and all! My first sense of surprise rapidly mounted to the status of a slow shock. That car must be there! I could take my oath it had not started. It could not move off without some sound. It was unthinkable that I should not have heard it. Yet—it was not there. No. 12, Portman Terrace stands in its own grounds in the middle of a long block of solid houses. Starting with absolute noiselessness, even a racing car could not have reached the corner—either corner. And, to get to the nearer of the two corners, the car would have had to turn around. I looked up and down the broad, empty street in both directions. The Napier limousine, unmistakable in its custom-built lines, somewhat old-fashioned, conspicuous, was, simply, not there. I started to speak to Rand, but was interrupted by the opening of the door. A stout, florid, family-retainer of a butler stood there, bowing.

'The Earl of Carruth, and Mr. Gerald Canevin,' said Rand, reaching for his card case, 'and it is imperative that we see Sir Harry Dacre immediately, in spite, even, of his possible orders that he is engaged.'

I followed Rand's motion for my card case mechanically and produced a card. The butler benignly ushered us within. He took our coats and hats and sticks. He showed us into a small drawingroom overlooking the square, just to the left of the entrance hall with its black marble paving.

'I will take your names to Sir Harry at once, m'Lord,' announced the butler urbanely, and disappeared up a wide flight of stairs.

THIS errand to Sir Henry Dacre, whom neither had ever seen, but who had been of late a familiar name to the newspaper-reading public, had been thrust upon Rand and myself in a somewhat remarkable manner. I had been, as it happened that morning, to my London tailor's, whose shop is in Jermyn Street, for a fitting. Finishing this minor ordeal and emerging upon Jermyn Street, the very first person I encountered was Rand. We had been together two nights previously, at a small men's dinner at Sir John Scott's. It was at Sir John's house that I had met him several months before. Anyone met there would be apt to be worth while. Sir John Scott presides over no less an institution than Scotland Yard. I had been immediately fascinated by Rand's grasp of the subject which has always more intrigued me—that of magical beliefs and occult practices among native peoples.

We had talked eagerly together, absorbingly, that first evening of our acquaintance. We talked, in fact, almost too late and too continuously for courtesy to one's host, even at a men's dinner. We outstayed our three other fellow guests. A brief note, received the next day from Sir John, had expressed—to my relief—his gratification that we had found so much to say to each other, had proved to be congenial. Rand, he explained briefly—as I, an Amercian, might not be aware—was the world's first authority on the subject I have named. He had been almost continuously away from England now for more than a score of years, serving the Empire in innumerable strange corners of its far-flung extent, but chiefly in India. A significant phrase of the note read: 'It is unquestionably due to Lord Carruth's remarkable abilities that the Indian Empire is now intact.' I considered that a very open admission for an Englishman, particularly one in Sir John Scott's position.

MEETING on the sidewalk that way, unexpectedly, we had stopped to chat for a moment, and, as it turned out that we were going in the same direction, we began to walk along together, arm in arm. As we came abreast of St. Paul's Cathedral, an elderly lady, very well dressed in plain black, came diagonally down the steps directly towards us, meeting us precisely as she reached the bottom. She addressed Rand directly.

'Will you be good enough to spare me a minute of your time, Lord Carruth?' she inquired.

'Assuredly,' replied Rand, bowing. We paused, removing our hats.

'It is a very pressing matter, or I should not have put you to this trouble,' said the lady, in a very beautiful, softly modulated voice, in which was to be clearly discerned that unmistakable tone of a class born to rule through many generations: a tone of the utmost graciousness, but nevertheless attuned to command. She continued: 'I beg that you will go at once to Sir Harry Dacre. It is number 12, Portman Terrace. My car is here at your disposal, gentlemen.' She included me with a gracious glance. 'It is an emergency, a very pressing affair. If you will start at once, you will perhaps be in time to save him.'

As she spoke, the lady, without seeming to do so consciously, was approaching the curbstone, edging, and we with her, diagonally across the wide pavement. At the curb, as I now observed, stood a very beautifully kept and well appointed town car, a Napier of a dozen-years-ago model. The chauffeur, in a black livery, sat motionless at the wheel. A very smart-looking, alert though elderly footman—his close-cropped hair was quite white, I observed—stood at rigid attention beside the tonneau door, a carriage-rug, impeccably folded into a perfect rectangle, across his angular arm.

The footman saluted, snapped open the door of the car, and we were inside and the lady speaking to us through the open door almost before we realized what we were doing. Her last words were significant, and spoken with the utmost earnestness and conviction.

'I pray God,' said she, 'that you may be in time, Lord Carruth. Sir Harry Dacre's, Baines.' This last she spoke very crisply, her words carrying an unmistakable undernote of urgency. The footman saluted again, very smartly; he draped the rug with practised skill across our four knees; the door was snicked to; and the old but beautifully appointed car, glistening with polish and good care, started almost simultaneously, the elderly footman snapping into his seat beside the chauffeur with an altogether surprising agility, and coming into position there like a ramrod, his arms folded before him with stiff precision.

THROUGH London's traffic now sped the Napier, as smoothly as a new car, the driving a very model of accuracy and sound form. It was plain that the unknown elderly lady was very well and promptly served. Not a single instant was lost, although there was no slightest feeling of being hurried such as ordinarily communicates itself to a person riding in an automobile when the driver is urged for time.

I glanced at Rand beside me. His ordinarily inscrutable, lean face was slightly puckered as though his mind were working hard.

'Who was the lady?' I ventured to inquire.

'That is what is puzzling me just now,' returned Rand. 'Frankly, I do not remember! And yet, at the same time, I'm quite sure I do know her, or know who she is. I simply cannot place her, although her face is familiar. She knew me, clearly enough. It is very unusual for me to forget like that.'

In a surprisingly short time after our start on this strange drive we had turned into Portman Terrace, stopped, had the door snapped open for us by the agile old footman and were out on the sidewalk. My last glimpse of the equipage as a whole was the salute with which the footman dismissed us. Then the strange conduct of an otherwise commonplace nursemaid, to which I have alluded, took all my attention. The nursemaid acted in her crude manner, as nearly as I can manage to describe her motivation, precisely as though we had landed—the thought struck me even at that time—in front of her from nowhere, instead of having merely, as I have said, stepped to the curbstone beside her out of a very well appointed town-car.

I COULD see that nursemaid now on the far side of the street and at some distance, as we sat in Sir Harry Dacre's small drawingroom, through the large window which looked out upon Portman Terrace. I even got up and walked to the window for the purpose. She was now talking with animation to a policeman, a big fellow. I watched with very great interest. I could not, of course, because of the distance and through a closed window, hear what she was saying, but I could follow it almost as well as though I could, from her gestures and the expressions on both their faces.

The woman pantomimed the entire occurrence for the policeman, and I got it now from her point of view, very clearly and plainly. My first impression of her possible reason for having behaved so insanely was amply corroborated. She had been placidly wheeling her charge along the walk when plop! two gentlemen, out of nowhere, had suddenly stepped on the curb in front of her! She had, of course, screamed. The gentlemen had looked at her as though surprised. They had then gone up the steps of Number 12, had rung and been admitted. These two visitors from Mars, or whatever they were, were now in Sir Harry Dacre's house. Hadn't the policeman better go and ring the area bell and make sure the silver was safe?

The policeman, a respectable-looking middle-aged man, probably accustomed to the vagaries of nursemaids, and doubtless with womenfolk of his own, sought to reassure her. Finally, not succeeding very well, he shrugged, left her expostulating and continued his dignified beat.

Learning in this way what had come over the nursemaid failed to make the mystery any clearer, however, than it had for the policeman, who had had the advantage of hearing her words. I was intensely puzzled. I turned away from the window and addressed Rand, who had been sitting there waiting in complete silence.

'HAVE you any idea what's wrong here?' said I. 'Here in this house, I mean.'

'You've read the papers, of course?' said Rand after a moment's consideration of my question.

'I know young Dacre's got himself rather heavily involved,' I replied. 'It's one of those infatuation affairs, is it not? A woman. She turns out to be mixed up, somehow, with Goddard, the impresario, or whatever he is. Isn't that about the case?'

Rand nodded. 'Yes. Apparently Goddard has him on toast. Rather a beast, that Goddard person. Goddard is not his name, by the way. A very clever person in the heavy-blackmail line. The Yard has never been able to "get anything on him", as you Americans put it. He has his various theatrical connections largely for a cover; but his real game is deeper, and blacker. It is rumored in certain circles that Goddard has ground poor Dacre here down to the very last straw in his garret; made him sign over all his holdings to avoid a show-up. Just how far he is committed with "The Princess Lillia" of the Gaieties, nobody seems to know. But that she is Goddard's wife, or at least that they are working together in close collusion, seems beyond question. That has not come out, of course. It is inside information.'

'But,' said I, 'just how, if I may ask, does that give them so complete a hold on Dacre? Why doesn't he simply repudiate them, now that he must know they set a trap for him? As nearly as I can figure it out from what I've seen in the papers and what you have just now told me, it's nothing more or less than an old-fashioned attempt at blackmail. And besides, it's had a certain amount of publicity already, hasn't it? Just what does Dacre stand to lose if Goddard does go to a show-down with him?'

'The point is,' explained Rand, 'that Dacre is engaged to be married to one of the loveliest girls in England. If it should really come out that "The Princess Lillia" is Goddard's wife, that would be off entirely. Lord Roxton would make that distinction very emphatically.

'To a man of his known views, a fine young fellow like Dacre would be more or less entitled to what Roxton would call "his fling." That would be typical, of course—British—to be expected. A well-to-do, unattached young man about town—and a lady from the Follies. Then the young blood really falls in love, drops his light-o'-love, is very devoted, marries, "settles down." But—if the lady from the Follies turns out to be the wife of somebody, somebody as much in the public eye as Leighton Goddard, and the matter of merely discontinuing that sort of thing is complicated by a lawsuit brought by the outraged husband—you can see how ruinous it would be, can you not, Canevin? The more especially when one is dealing with one of those rather narrow, puritanical old hoddy-doddies like Lord Roxton, who is so consciously upright that he positively creaks with piety when he gets up or sits down. He would never allow his daughter to marry Dacre under those circumstances. He's the President of the Evangelican League, a reformer. Incidentally, he is one of the richest men in England; has tremendously strong views on how people should behave, you know. And Dacre's financial affairs, his investments, are to a considerable extent tied up with Lord Roxton's promotions and companies.'

THIS much of the background—though nothing whatever of the immediate urgency of the case which confronted us—we knew when the dignified butler returned with the announcement that Sir Harry Dacre would receive us at once. We followed the butler up a magnificent flight of stairs to the story above, and were shown into a kind of library-office, from behind whose enormous mahogany desk a handsome young fellow of about twenty-five rose to receive us. Sir Harry Dacre said nothing whatever, and I observed that his drawn face was lined and ghastly, plainly enough from the effects of lack of sleep. It was obvious to me that Lord Carruth's name alone had secured us admittance. The man whose abilities had served to keep the Indian Empire intact could hardly be gainsaid by anyone of Sir Harry Dacre's sort.

Rand went straight to the desk, and without any ceremony picked up and pocketed a .38 calibre American automatic pistol which lay directly in front of Sir Harry Dacre's chair.

'Perhaps you know I am accustomed to meeting emergencies halfway, sir,' said Rand, bluntly but not unkindly. 'I'll not ask you to forgive an intrusion, Sir Harry. I am Carruth; this is Mr. Canevin, an American gentleman visiting in London.'

'Thanks,' said young Dacre, dully. 'I know you mean very well, Lord Carruth, and I appreciate your kindness in coming here. I have had the pleasure of reading Mr. Canevin's remarkable tales,' he added, turning and bowing in my direction. We stood there, after that, in a momentarily tense, and indeed slightly strained silence.

'SUPPOSE we all sit down, now that we are all together,' said our host. We followed the suggestion, making, as we sat, a triangle; Dacre behind his great desk; I facing him, with my back to the door through which we had entered the room; Rand at my right and facing a point between Dacre and me, and so commanding a view of him and also of the door.

'We are here to serve you, Sir Henry Dacre,' began Rand, without any preamble, 'and, judging by this,'—he indicated the automatic pistol—'it appears that you need assistance and countenance. In a case like this it is rather futile to waste time on preliminaries or in beating about the bush. Tell us, if you will, precisely what we can do, and I assure you you may count upon us.'

'It is indeed very good of you,' returned Dacre, nodding his head. Then, with a wry and rueful smile: 'I do not see that there is anything that anybody can do! I suppose you know something of the situation. I am to marry the Lady Evelyn Haversham in a month's time. I have, I suppose, made a complete fool of myself, at least for practical purposes. As a matter of plain fact, there has been, really, nothing—nothing, that is, seriously to trouble one's conscience. But then, I'll not trouble to excuse myself. I am merely stating the facts. To put the matter plainly, this Goddard has me where he wants me—a very clever bit of work on his part. Here are the freeholds of every bit of property I own, piled up in front of me on this desk. He's coming for them this morning—eleven—should be here now. That's the price of his silence about the apparent situation, you see. "The Princess Lillia" is his wife, it appears.'

'But,' Rand put in, briskly, 'how about this?' Once more he indicated the pistol. The young man's face flushed a dull red.

'That was for him,' he said quietly, 'and afterwards'—he spread his hands in a hopeless gesture—'for me.'

'But, why, why?' urged Rand, leaning forward in his chair, his lean, ascetic face eager, his eyes burning with intensity. 'Tell me—why resort to such a means?'

'Because,' returned Sir Harry Dacre, 'there would be nothing left. On the one hand, if I were to refuse Goddard's terms, he would bring out the whole ugly business. Oh, they're clever: a case in court, one of those ruinous things, and an action for alienation of his wife's affections; a divorce case, with me as the villain-person. On the other hand—don't you see?—I'm flatly ruined. These papers convey everything I own to him in return for the release which lies here ready for him to sign. Even with the release signed and in my possession I could not go on with the marriage. I'd be, literally, a pauper. It is, well, one of those things that one does not, cannot do.'

'Let me see the release,' said Rand, and rose, his hand outstretched. He glanced through it, rapidly, nodding his head, and returned it to its place on the desk. 'There is little time,' he continued. 'Will you do precisely as I say?'

'Yes,' said Sir Harry Dacre laconically, but I could see no appearance of hope on his face.

'Go through with it precisely as arranged,' said Rand.

A rap fell on the door, and it was opened slightly.

'Mr. Leighton Goddard,' announced the butler, and I saw Rand stiffen in his chair. The look of hopeless despair deepened in the lined face of the young man behind the desk. He had, I surmised, as he had reasoned out this sordid affair, come to the last act. The curtain was about to fall....

THE man who now entered radiated personality. He was tall, within half an inch or so of Rand's height, and Rand is two inches over six feet. There was a suggestion of richness about him, sartorial richness, an aura of something oriental which came into that Anglo-Saxon room with him. One could not put a finger on anything wrong in his really impeccable appearance. Bond Street was written upon his perfect morning coat; but I would have guessed, I think, almost instinctively, that his name was not really Goddard, even if no one had suggested that to me. He glanced about the room, very much self-possessed, and with an air almost proprietary, out of shining, sloe-black eyes set in a face of vaguely Asiatic cast: a suggestion of olive under the pale skin of the night-club habitué; a certain undue height of the cheekbones.

'Now, this isn't according to agreement, Dacre!' He addressed his host in a slightly bantering tone, almost genially, indeed; a tone underneath which I could feel depths of annoyance; of a poisonous, threatening malice. He had stopped between Rand and me.

'We merely dropped in,' said Rand, in a flat voice, and Goddard glanced around at him out of the corner of his eye. Dacre picked up the hint. 'This is Mr. Gerald Canevin, the writer,' said he, and I rose and nodded to Goddard. As I did so, I caught Rand's eye, with warning in it. I thought I grasped his meaning. If he had formulated any definite plan for dealing with this ugly situation there had been no time to warn me of it before Goddard's rather abrupt arrival, several minutes late for his appointment. I did some very rapid thinking, came to a conclusion, and spoke quietly to Goddard in a tone of voice that was intentionally somewhat slow and deliberate.

'This is Mr. Rand,' said I; and Rand flashed me a quick, commending look of relief. He did not want Goddard to know his true identity. That had been my conclusion from his warning look. Fortunately, I had struck the nail on the head that time. The two men nodded coolly to each other, and it seemed to me that suspicion loomed and smouldered in those oriental eyes.

Dacre came to the front.

'We can get our business over very easily,' said Dacre at this point. 'Here are the things you want, and here is the place to sign.' He stood up behind the desk, holding a sheaf of legal looking documents.

Goddard walked firmly over to the desk, took across it the papers out of Dacre's hand, glanced through them rapidly, nodded as he checked each mentally, and at last relaxing his tensely held body thrust them, all together, into the inside pocket of his morning coat. He smiled quickly, as though satisfied, took a step nearer the desk, stooped over, and, still standing, reached for a pen and scrawled his name on the paper Dacre indicated.

This done, he straightened up, though still retaining his slightly stooping position, and turned away from the desk. I was watching him narrowly and so, too, I knew, was Rand. Triumphant satisfaction was writ large on his unpleasant face. But that look was quickly dissipated. He turned away from the desk at last, and met Rand facing him, Dacre's pistol pointed straight at his heart. I, standing now behind Goddard, could look straight into Rand's face, and I do not care ever to have to look into such an expression of rigid determination and complete, utter self-confidence behind any weapon pointed in my direction.

'YOU will take those deeds out of your pocket, Wertheimer,' said Rand, in a deadly, cold, quiet voice, 'and drop them on the floor. Then you will go out of here without any further parley. Otherwise I shall take them from you; if necessary, kill you as you stand there; arrange the matter with Downing Street this afternoon, and so rid the world of a very annoying scoundrel. I am the Earl of Carruth. I came here without Dacre's knowledge, to deal with this situation. What you have to decide, rather quickly, is whether you will go on living on what you have already stolen, without this of Dacre's, or whether you will put me to the inconvenience of—removing you.'

From my position I could not, of course, see Goddard's—or Wertheimer's—face. But I did observe the telltale hunching of a shoulder, and cried out in time to warn Rand. But Rand needed no warning, as it happened. He met the rush of the big man with his disengaged hand, now a fist, and Wertheimer, catching that iron fist on the precise point of the chin, slithered to the floor, entirely harmless for the time being.

Rand looked down at the sprawled body, then walked over to the desk and laid the automatic pistol down on the place from which he had picked it up. Then, returning to the prostrate Wertheimer, he knelt beside him and removed the packet of deeds from the man's pocket. He rose, returned to the desk, and handed them to young Dacre, who, during the few seconds occupied by all these occurrences, had remained standing, silent and collected, behind his desk.

'THE transaction, of course, was illegal,' remarked Rand, looking down at the crumpled torso of Wertheimer. 'You need have no compunction whatever, Dacre, my dear fellow, in retaining the release which he signed. "Goddard" is not his name, of course. But I imagine that fact would have no bearing upon the efficacy of the release. He has gone under that name and is thoroughly identified with it here in London, Sir John Scott informs me, for the past four or five years. You heard me call him "Wertheimer", but even that is not his real name. He is a Turk, and his right name is Abdulla Khan ben Majpat. However, he was a German spy during the War, and in Berlin he is very well known as "Wertheimer." I think I may say that you are now quite free from the complication which was distressing you.'

It was a very subdued Goddard-Wertheimer-ben Majpat who left the house a quarter of an hour later, after a few crisply spoken words of warning from Rand. And it was a correspondingly jubilant young man who besieged Rand with his reiterated thanks. Sir Harry Dacre was, indeed, almost beside himself. In the stimulating grip of a tremendous reaction such as he had just experienced, a man's everyday composure is apt to go to the winds. This unexpected release from his overpowering difficulties which Rand's intervention had brought about had, for the time being, caused Sir Harry Dacre to seem like a different person. There had not been any statements in the newspapers of sufficiently definite nature to injure his cause with his future wife or with his future father-in-law, the austere Lord Roxton, and now, as Rand took care to assure him, there would be no further press comment. The situation seemed entirely cleared up.

Young Dacre, looking years younger, with the lines of harassment and care almost visibly fading out of his face under the stimulation of his new freedom and the natural resiliency of his youth, would be quite all right again after a proper night's rest. He confessed to us that it was the best part of a week since he had so much as slept. His gratitude knew no bounds. It was almost effusive and really very touching. He pressed us to remain for luncheon. This we declined, but we could not very well refuse his request that we should have a Scotch and soda with him. While this refreshment was being brought by the butler, Rand stepped around to the other side of the desk and picked up a framed photograph which stood upon it.

'AND who, if I may venture to ask, is this?' he inquired.

'It was my mother's sister, the Lady Mary Grosvenor,' said young Dacre. 'You may remember her, perhaps. It was she, you know, who organized the Red Cross at the beginning of the War. I was only a little chap of seven or eight then.' He took the photograph from Rand and stood looking at it with an expression of the deepest affection.

'A wonderful woman!' he added, 'and the best friend I ever had, Lord Carruth. She took me into her house here when I was a tiny little youngster. My own mother died when I was four. The house came to me in her will, eight years later. Dear Aunt Mary—her kindness and goodness never failed. She took me, a rather forlorn little creature, I dare say, into her care. She found time to do everything for me. She was a woman of manifold interests and activities, as you may remember, Lord Carruth, and even high in the counsels of the great, the affairs of the Empire. Cabinet members, even the Prime Minister himself, sought her advice, kept her occupied with all kinds of difficult tasks. In spite of all these engagements, she was, as I have said, and in all ways, a mother to me—yes, more than a mother. I naturally revered her.'

Young Sir Harry Dacre paused, sitting there in his office-library, with his guests to whom he was thus opening his heart with sudden, wistful seriousness. When he spoke again it was in a much quieter tone than that of the little panegyric he had just ended.

'Do you know,' said he, 'I—I thank God that the dear soul was at least spared any knowledge of this—this dreadful affair which is—I can hardly realize, gentlemen, that it is over, done, a thing of the past.'

Again he paused, sat for a moment very quietly in a natural silence which neither Rand nor I desired to break.

Then, in a hushed tone, his words coming slowly and very reverently, he spoke again.

'And if,' he began, as though concluding a thought already partly uttered, '—and if she has been enabled to see it all—from her place in Paradise, as one might say—she is rejoicing now, and thanking you. She would have moved Heaven and earth to help me.'

Then, as I looked into the face of Sir Harry Dacre, I saw a slow flush mounting upon it. That curious sense of shame which seems common to every Englishman who allows himself to show others something of his inmost feeling, had overtaken the young man. He resumed his discourse in an entirely different and rather restrained tone.

'But that, of course, is impossible,' said he. 'I hope that I have not made myself ridiculous. Naturally I should know better than to bore you in this way. Reasonable people should not allow themselves to be moved by such old sentimentality. And, I—I was educated Modern Side.'

'I do not think we are bored by what you have said,' remarked Rand, quietly, and added nothing to that.

Dacre paused, rose, and replaced on the desk the framed photograph which he had been holding and looking at while he spoke. As yet, except from the back, I had not had a view of it. Returning to where we were seated, Dacre took a chair between Carruth and me.

'CURIOUS!' exclaimed our host, breaking a brief silence. 'I mean to say, my aunt, there, was very active in the War, you know. As a matter of fact, she visited every front, and never received as much as a scratch! People used to say that she seemed to bear a charmed life. Then back home here in England, driving one afternoon through Wolverhampton in her old town-car—it was just two days before the Armistice, in 1918—I was just twelve at the time—a bomb from a raiding German airplane took her, poor lady; and along with her old Baines, her footman—been with her thirty-four years—and the chauffeur. Killed all three, snuffed 'em right out, and there wasn't enough of the old Napier town-car left to identify it! The way things happen....'

Carruth nodded, sympathetically. It was plain that young Dacre had been much moved by his recital. He must have had an extraordinarily high regard for the splendid woman who had mothered him. At this moment Dacre's butler appeared with a tray and bottles, ice, tall glasses and siphons of carbonated water.

While he was arranging these on a table, I walked over to the desk and took up the large framed photograph.

There, in the uniform of the British Red Cross, looked out at me the splendid face of a middle-aged lady, the face of a true aristocrat, of one born to command. It was kindly, though possessing a firm, almost a stern expression, the look of one who would never give up!

I replaced the photograph, my hands shaking. I turned about quickly and walked across the room. I wanted rather urgently to be quite close to living, breathing human beings like Carruth and our host—fellow-men, creatures of common, everyday flesh and blood. I stood there among them, between Rand and Dacre, and almost touching the urbane butler as he prepared our Scotch and soda with admirable professional deftness. I confess that I wanted something else, besides that sense of human companionship which had come upon me so compellingly that I had found my hands shaking as I set the framed photograph back into its original place on Sir Harry Dacre's desk.

Yes—I wanted that high cool, iced tumbler of Scotch whiskey and soda the butler was handing me. I barely waited, indeed, until the others had been served to raise it to my lips, to take a great, hasty drink which emptied the glass halfway to its bottom.

For—I had seen that photograph of Dacre's aunt, the Lady Mary Grosvenor, that firm gentlewoman who had, in the goodness of her noble heart, stolen precious time from the counsels of a great Empire to comfort a pathetic little motherless child; who would have moved Heaven and earth; a woman who would never give up...

'... old Baines, her footman—been with her thirty-four years... '

'... killed all three, snuffed 'em right out... '

'... not enough of the old Napier town-car left to identify it... '

And I had looked at that photograph.

I FINISHED my Scotch and soda and set my glass down on the butler's silver tray. I drew in a deep breath. I was coming back satisfactorily to something like normal.

I raised my eyes and looked over at Rand. It had just occurred to me that he, too, was now aware of the identity of the lady who had sent us here in that old Napier with the two perfectly trained servants in its driving seat, to save Sir Harry Dacre. Rand had seen the photograph, too, well before I had picked it up and looked at it.

I found quite as usual the facial expression of the man who had held the Indian Empire together resolutely for twenty years—the man who had learned that iron composure facing courageously all forms of death and worse-than-death in the far, primitive places of the earth, places where transcendent evil goes hand in hand with ancient civilizations.

Even as I looked, James Rand, Lord Carruth, was turning to our host and addressed him in his firm, courteous, even voice.

'I take it that—with Mr. Canevin to corroborate what I would say, speaking as an eyewitness—you would accept my word of honor—would you not, Dacre?'

Young Dacre stared at him, almost gulped with surprise when he replied to so unusual a question: 'Of course, Lord Carruth; certainly, sir. Your word of honor—Mr. Canevin to corroborate! Of course such a thing would not be necessary, sir. Good Heavens! Of course, I'd believe anything you chose to say, sir, like the Gospel itself.'

'Well, then,' said Rand, smiling gravely, 'if it is agreeable to Mr. Canevin, I think we shall change our minds and remain to luncheon with you. There is something I think you should know, and the period of luncheon will just give us time to tell you the circumstances behind our arrival here at about the right time for our business this morning.'

RAND looked over at me, and I nodded, eagerly.

'Splendid!' said Sir Harry Dacre, rising alertly and ringing the bell for the butler. 'I had, of course, been awfully keen to know about that. Hardly cared to ask, you know.'

'My reason for suggesting that we tell you,' said Rand gravely, 'goes rather deeper than merely satisfying a very reasonable curiosity. If by doing so we can accomplish what I have in mind, it will be, my dear fellow, a more important service in your behalf than ridding you of that Wertheimer.'

The butler came in and our host ordered the places set. Then, very soberly, he inquired: 'What, sir, if I may venture to ask, is the nature of that service?'

Rand answered only after a long and thoughtful interval.

'It may seem to you a rather odd answer, Dacre. I want to clear up in your mind, forever, the truth of what the religion we hold in common—the religion of our ancient Anglican Church here in England—teaches us about the souls in Paradise... '

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.