RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

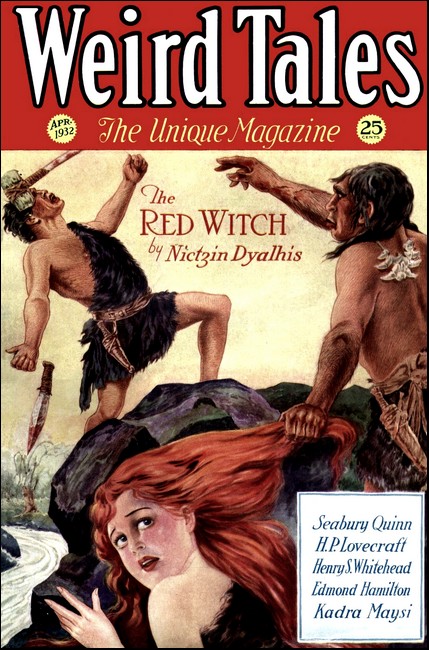

Weird Tales, April 1932, with "Mrs. Lorriquer"

A West Indian story of possession and dual per-

sonality by the author of the "Jumbee" tales.

"I advanced straight upon him."

THE late Ronald Firbank, British author, apostle of the light touch in literary treatment, put grass skirts upon the three lady heroines of his West Indian book, Prancing Nigger, as all persons who have perused that delicate romance of an unnamed West Indian island will doubtless remember. In so dressing Mrs. Mouth, and her two attractive daughters, Mr. Firbank was only twelve thousand miles out of the way, although that is not bad for anybody who writes about the West Indies—almost conservative, in fact. I, Gerald Canevin, have more than once reassured timid female inquirers, who had heard of our climate, but who were apprehensive of living among 'those savages and cannibals!'

I have always suspected that Mr. Firbank, to go back for a moment to that gentleman before dismissing him and his book, got his light-touch information about the West Indies from a winter tour aboard one of the great trans-Atlantic liners which, winters, are used for such purposes in the Mediterranean and Caribbean, and which, in St. Thomas, discharge their hundreds of 'personally conducted' tourists in swarms upon our innocent, narrow sidewalks, transforming the quiet, Old World town into a seething, hectic marketplace for several hours every two weeks or so during a winter's season there.

For, truth being stranger by far than any fiction, there are grass skirts—on such occasions—on St. Thomas's streets; piles and stacks of them, for sale to tourists who buy them avidly. I know of no more engaging sight in this world than a two hundred and fifty pound tourist-lady, her husband in the offing, his hand in his money-pocket, chaffering with one of our Cha-Cha women with her drab, flat face and tight-pulled, straight hair knotted at the back, for a grass skirt!

It appears that, some years back, a certain iron-visaged spinster, in the employ of a social service agency, 'took up' the Cha-Cha women, seeking to brighten their lot, and, realizing that a certain native raffia grass had commercial possibilities, taught them to make Polynesian grass skirts of it. Thereafter and ever since there has been a vast plague of these things about the streets of St. Thomas whenever a tourist vessel comes into our harbor under the skilled pilotage of Captain Simmons or Captain Caroc, our pilots.

I open this strange tale of Mrs. Lorriquer in this offhand fashion because my first sight of that compact, gray-haired little American gentlewoman was when I passed her, in the very heart and midst of one of these tourist invasions, rather indignantly trying to get rid of an insistent vendor who seemed possessed to drape her five feet two, and one hundred and sixty pounds, in a five-colored grass skirt, and who would not be appeased and desist. As I was about to pass I overheard Mrs. Lorriquer say, with both indignation and finality: 'But, I'm not a tourist—I live here!'

That effectually settled the grass-skirt seller, who turned her attention to the tourists forthwith.

I had paused, almost unconsciously, and found myself face to face with Mrs. Lorriquer, whom I had not seen before. She smiled at me and I smiled back.

'Will you allow another permanent resident to rescue you from this mêlée?' I inquired, removing my hat.

'It is rather like a Continental mardi gras, isn't it?' said Mrs. Lorriquer, taking my arm.

'Where are you staying?' I inquired. 'Are you at the Grand Hotel?'

'No,' said Mrs. Lorriquer. 'We have a house, the Criqué place, halfway up Denmark Hill. We came down the day before yesterday, on the Nova Scotia, and we expect to be here all winter.'

'I am Gerald Canevin,' said I, 'and I happen to be your very near neighbor. Probably we shall see a good deal of each other. If I can be of any assistance—'

'You have, already, Mr. Canevin,' said Mrs. Lorriquer, whimsically.

I supposed at once she referred to my 'rescue' of her from the tourist mob, but, it seemed, she had something quite different in her mind.

'It was because of some things of yours we had read,' she went on, 'that Colonel Lorriquer and I—and my widowed daughter, Mrs. Preston—decided to spend the winter here,' she finished.

'Indeed!' said I. 'Then, perhaps you will allow me to continue the responsibility. When would it meet your convenience for me to call and meet the Colonel and Mrs. Preston?'

'Come any time,' said Mrs. Lorriquer, 'come to dinner, of course. We are living very informally.'

We had reached the post-office, opposite the Grand Hotel, and here, doubtless according to instructions, stood Mrs. Lorriquer's car. I handed her in, and the kindly-faced, short, stout, little sixty-year-old lady was whirled away around the corner of the hotel toward one of the side roads which mount the precipitous sides of St. Thomas's best residential district.

I CALLED the following afternoon, and thus inaugurated what proved to be a very pleasant aquaintanceship.

Colonel Lorriquer, a retired army engineer, was a man of seventy, extraordinarily well preserved, genial, a ripened citizen of the world. He had, it transpired on acquaintance, had a hand in many pieces of engineering, in various parts of the known world, and had spent several years on that vast American enterprise, the construction of the Panama Canal. Mrs. Preston, whose aviator husband had met his death a few months previously in the exercise of his hazardous profession, turned out to be a very charming person, still stunned and over-burdened with the grief of her bereavement, and with two tiny children. I gathered that it was largely upon her account that the Colonel and Mrs. Lorriquer had come to St. Thomas that winter. Being a West Indian enthusiast, it seemed to me that the family had used excellent judgment. There could be no better place for them under those circumstances. There is that in the charm and perfect climate of the Northern Lesser Antilles which heals the wounds of the heart, even though, as they say, when one stays too long there is Lethe.

We settled down in short order to a more or less intimate acquaintanceship. The Lorriquers, and Mrs. Preston, were so to speak, 'my sort of people.' Many mutual acquaintances developed as we became better acquainted. We found much in common.

I have set down all this preliminary portion of this story thus in detail, because I have wished to emphasize, if possible, the fact that never, in all my experience with the bizarre which this human scene offers to the openminded observer, has it occurred to me to find any greater contrast than that which existed between Mrs. Lorriquer, short, stout, matter-of-fact, kindly little lady that she was, and the quite utterly incredible thing which—but I must not, I simply must not, in this case, allow myself to get ahead of my story. God knows it is strange enough not to need any 'literary devices' to make it seem stranger.

The Lorriquers spent a good deal of the time which, under the circumstances, hung upon their hands, in card-playing. All three members of the family were expert Auction and Contract players. Naturally, being quite close at hand, I became a fourth and many evenings not otherwise occupied were spent, sometimes at my house, sometimes at theirs, about the cardtable.

The Colonel and I played together, against the two ladies, and this arrangement was very rarely varied. Occasionally Mrs. Squire, a middle-aged woman who had known the Lorriquers at home in the States, and who had an apartment at the Grand Hotel for the winter, joined us, and then, usually, Mrs. Preston gave up her place and Mrs. Squire and I paired against the Colonel and his wife.

EVEN after the lapse of several years, I confess that I find myself, as I write, hesitant, reluctant somehow, to set down the beginning of the strange discrepancy which first indicated what was to come to light in our innocent social relationship that winter. I think I can best open up this incredible thing, by recording a conversation between me and Mrs. Squire as we walked, one moonlit midnight, slowly down the hill toward the Grand Hotel.

We had finished an evening at the Lorriquers,' and Mrs. Lorriquer had been especially, a little more than ordinarily, rude over the cards. Somehow, I can not say how it occurred, we discussed this strange anomaly in our hostess, usually the most kindly, simple, hospitable soul imaginable.

'She only does it when she plays cards,' remarked Mrs. Squire. 'Otherwise, as you have said, Mr. Canevin, she is the very soul of kindliness, of generosity. I have never been able to understand, and I have known the Lorriquers for more than ten years—how a woman of her character and knowledge of the world can act as she does over the cardtable. It would be quite unbearable, quite utterly absurd—would it not—if one didn't know how very sweet and dear she really is.'

It was, truly, a puzzle. It had developed very soon after we had started in at our Bridge games together. The plain fact, to set it down straight, was that Mrs. Lorriquer, at the cardtable, was a most pernicious old termagant! A more complete diversity between her as she sat, frowning over her cards; exacting every last penalty; enforcing abstruse rules against her opponents while taking advantage of breaking them all herself ad libitum; arguing, most inanely and even offensively, over scores and value of points and penalties—all her actions and conduct at the cardtable; with her general placidity, kindliness, and effusive good-nature under all other circumstances—a more complete diversity, I say, could never be imagined.

It has always been one of my negative principles that annoyance over the details or over the outcome of any game of chance or skill should never be expressed. That sort of thing has always seemed to me absurd; indeed, inexcusable. Yet, I testify, I have, and increasingly as our acquaintance progressed, been so worked up over the cards when playing with the Lorriquer family, as to have to put the brakes down tight upon some expression of annoyance which I should later have regretted. Indeed, I will go farther, and own up to the fact that I have been badgered into entering into arguments with Mrs. Lorriquer at the table, when she would make some utterly outrageous claim, and then argue—the only word for it is offensively—against the massed testimony of her opponents and her partner for the evening. More than once, Mrs. Preston, under the stress of such an exhibition of temper and unreasonableness on her mother's part, has risen from the table, making some excuse, only to return a few minutes later. I believe that on all such occasions, Mrs. Preston took this means of allowing her annoyance to evaporate rather than express herself to her mother in the presence of a guest.

To say that it was annoyance is to put it very mildly indeed. It was embarrassing, too, to the very last degree. The subjects upon which Mrs. Lorriquer would 'go up in the air,' as Mrs. Squire once modernly expressed it, were always trivial; always unreasonable. Mrs. Lorriquer, although a finished player in all respects, was, I think, always, as a matter of fact, in the wrong. She would question the amount of a score, for example, and, upon being shown the printed penalties for such score on the cover-page of the score pad, or from one of the standard books on the game, would shift over to a questioning of the score itself. The tricks, left on the table, would be counted out to her, before her eyes, by Colonel Lorriquer. Halfway through such an ocular demonstration, Mrs. Lorriquer would interrupt her husband with some kind of diatribe, worthy of the mind of a person quite utterly ignorant of the game of Contract and of decent manners. She insisted upon keeping all scores herself, but unless this process were very carefully watched and checked, she would, perhaps half the time, cheat in favor of her own side.

It was, really, outrageous. Time and time again, I have gone home from the Lorriquers,' after such an evening as I have indicated, utterly resolved never to play there again, or to refuse, as courteously as might be possible, to meet Mrs. Lorriquer over a cardtable. Then, the next day, perhaps, the other Mrs. Lorriquer, charming, kindly, sweet-natured, gentle and hospitable, would be in such overwhelming, disarming evidence, that my overnight resolution would be dissipated into thin air, and I would accuse myself of becoming middle-aged, querulous!

But this unaccountable diversity between the Mrs. Lorriquer of ordinary affairs and the Mrs. Lorriquer of the cardtable, outstanding, conspicuous, absurd indeed, as it was, was really as nothing when compared to Mrs. Lorriquer's luck at the cards.

I have never seen anything like it; never heard, save in old-fashioned fictional tales of the person who sold his soul to Satan for invincibility at cards, of anything which could compare to it. It is true that Mrs. Lorriquer sometimes lost—a single game, or perhaps even a rubber. But in the long run, Mrs. Lorriquer, even on the lowest possible basis for expressing what I mean, did not need to cheat, still less to argue over points or scores. She won, steadily, inevitably, monotonously, like the steady propulsive motions of some soulless machine at its mechanical work. It was virtually impossible to beat her.

We did not play for stakes. If we had, a goodly portion of my income would have diverted that winter to the Lorriquer coffers. Save for the fact that as it was the Colonel who played partners with me, it would have been Mrs. Lorriquer, rather than the Lorriquer family, who would have netted all the proceeds!

In bidding, and, indeed, in the actual playing of a hand, she seemed to follow no system beyond abject reliance on her 'luck.' I have, not once, but many, many times, known her, for example, to bid two no-trump originally, on a hand perhaps containing two 'singletons,' only to have her partner 'go to three' with a hand containing every card which she needed for the dummy. I will not specify, beyond this, any technical illustrations of how her extraordinary 'luck' manifested itself. Suffice it to say that Bridge is, largely, a mathematical matter, varied, in the case of four thoroughly trained players, by what is known as the 'distribution' of the cards. It is this unknown element of 'distribution' which keeps the game, in the hands of a table of experts, a 'game of chance' and not merely a mathematical certainty gaged by skillful, back-and-forth, informative bidding. To put the whole matter of Mrs. Lorriquer's 'luck' into a nutshell, it was this element of 'distribution' of the cards which favored her, in and out of season; caused her to win with a continuous regularity; never seeming to cause her to be pleased at her success and so lend to an evening at cards with her at the table that rather unsatisfactory geniality which even a child shows when it 'gets the breaks' at a game.

No; Mrs. Lorriquer was, while engaged in playing Bridge, a harridan, a disagreeable old vixen; a 'pill' as, I believe, I once heard the outraged Mrs. Squire mutter desperately, under her breath!

Perhaps it would be an exaggeration to allege that as against the Colonel and me, playing as partners for many evenings, the 'distribution' of the cards was adverse with absolute uniformity. I should hesitate to say that, positively, although my recollection is that such was the case. But, in the ordinary run of affairs, once in a while one of us would get a commanding hand, and, immune from the possibility of the 'distribution' affecting success, would play it out to a winning score for the time being. It was after one such hand—I played it, the Colonel's hand as dummy—that I succeeded in making my bid: four hearts, to a game. I remember that I had nine hearts in my hand, together with the ace, king of clubs, and the 'stoppers' on one other suit, and finishing with something 'above the line' besides 'making game' in one hand, that my first intimation of a strange element in Mrs. Lorriquer's attitude to the game made itself apparent. Hitherto—it was, perhaps, a matter of a month or six weeks of the acquaintance between us—it had been a combination of luck and what I can only call bad manners; the variety of luck which I have attempted to indicate and the 'bad manners' strictly limited to such times as we sat around the square table in the center of the Lorriquers' breezy hall.

The indication to which I have referred was merely an exclamation from my right, where Mrs. Lorriquer sat, as usual, in her accustomed place.

'Sapristi!' boomed Mrs. Lorriquer, in a deep, resonant, manlike voice.

I looked up from my successful hand and smiled at her. I had, of course, imagined that she was joking—to use an antique, rather meaningless, old-French oath, in that voice. Her own voice, even when scolding over the cardtable, was a light, essentially feminine voice. If she had been a singer, she would have been a thin, high soprano.

To my surprise, Mrs. Lorriquer was not wearing her whimsical expression. At once, too, she entered into an acrimonious dispute with the Colonel over the scoring of our game-going hand, as usual, insisting on something quite ridiculous, the old Colonel arguing with her patiently.

I glanced at Mrs. Preston to see what she might have made of her mother's exclamation in that strange, unaccustomed, incongruous voice. She was looking down at the table, on which her hands rested, a pensive and somewhat puzzled expression puckering her white forehead. So far as I could guess from her expression she, too, had been surprised at what she had heard. Apparently, I imagined, such a peculiar manifestation of annoyance on Mrs. Lorriquer's part was as new to her daughter as it was to me, still a comparative stranger in that family's acquaintance.

We resumed play, and, perhaps an hour or more later, it happened that we won another rather notable hand, a little slam, carefully bid up, in no-trump, the Colonel playing the hand. About halfway through, when it was apparent that we were practically sure of our six over-tricks, I noticed, being, of course, unoccupied, that Mrs. Lorriquer, at my right, was muttering to herself, in a peculiarly ill-natured, querulous way she had under such circumstances, and, my mind stimulated by the remembrance of her use of the old-French oath, I listened very carefully and discovered that she was muttering in French. The most of it I lost, but the gist of it was, directed toward her husband, a running diatribe of the most personal and even venomous kind imaginable.

Spanish, as I was aware, Mrs. Lorriquer knew. She had lived in the Canal Zone for a number of years, and elsewhere where the Colonel's professional engagements as an engineer had taken them, but, to my knowledge, my hostess was unacquainted with colloquial French. The mutterings were distinctively colloquial. She had, among other things, called her husband in those mutterings 'the accursed child of a misbegotten frog,' which is, however inelegant on the lips of a cultivated elderly gentlewoman, at least indicative of an intimate knowledge of the language of the Frankish peoples! No one else sensed it—the foreign tongue, I mean—doubtless because both other players were fully occupied, the Colonel in making our little slam, Mrs. Preston in doing what she could to prevent him, and besides, such mutterings were common on Mrs. Lorriquer's part; were usual, indeed, on rare occasions when a hand at Bridge was going against her and her partner. It was the use of the French that intrigued me.

A FEW days later, meeting her coming down the hill, a sunny smile on her kindly, good-humored face, I addressed her, whimsically, in French. Smilingly, she disclaimed all knowledge of what I was talking about.

'I supposed you were a French scholar, somehow,' said I.

'I really don't know a word of it,' replied Mrs. Lorriquer, 'unless, perhaps, what "R.S.V.P." means, and—oh, yes!—"honi soit qui mal y pense!" That's on the great seal of England, isn't it, Mr. Canevin?'

It set me to wondering, as, I imagine, it would have set anyone under just those circumstances, and I had something to puzzle over. I could not, you see, readily reconcile Mrs. Lorriquer's direct statement that she knew no French, a statement made with the utmost frankness, and to no possible end if it were untrue, with the fact that she had objurgated the Colonel under her breath and with a surprising degree of fluency, as 'the accursed child of a misbegotten frog!'

It seemed, this little puzzle, insoluble! There could, it seemed to me, be no possible question as to Mrs. Lorriquer's veracity. If she said she knew no French besides the trite phrases which everybody knows, then the conclusion was inevitable; she knew no French! But—beyond question she had spoken, under her breath to be sure, but in my plain hearing, in that language and in the most familiar and colloquial manner imaginable.

There was, logically, only one possible explanation. Mrs. Lorriquer had been speaking French without her own knowledge!

I had to let it go at that, absurd as such a conclusion seemed to me.

But, pondering over this apparent absurdity, another point, which might have been illuminating if foresight were as satisfactory as 'hindsight,' emerged in my mind. I recalled that what I have called 'the other Mrs. Lorriquer' was an especially gentle, kindly person, greatly averse to the spoiling of anybody's good time! The normal Mrs. Lorriquer was, really, almost softly apologetic. The least little matter wherein anything which could possibly be attributed to her had gone wrong would always be the subject of an explanation, an apology. If the palm salad at one of her luncheons or dinners did not seem to her to be quite perfect, there would be deprecatory remarks. If the limes from which a little juice was to be squeezed out upon the halved papayas at her table happened not to be of the highest quality, the very greenest of green limes that is, Mrs. Lorriquer would lament the absence of absolutely perfect limes that morning when she had gone in person to procure them from the marketplace. In other words, Mrs. Lorriquer carried almost to the last extreme her veritable passion for making her guests enjoy themselves, for seeing to it that everybody about her was happy and comfortable and provided with the best of everything.

But—it occurred to me that she never apologized afterward for any of her exhibitions at the cardtable.

By an easy analogy, the conclusion—if correct—was inevitable. Mrs. Lorriquer, apparently, did not at all realize that she was a virtually different person when she played cards.

I pondered this, too. I came to the conclusion that, queer as it seemed, this was the correct explanation of her extraordinary conduct.

But—such an 'explanation' did not carry one very far, that was certain. For at once it occurred to me as it would have occurred to anybody else, her husband and daughter for choice, that there must be something behind this 'explanation.' If Mrs. Lorriquer 'was not herself' at such times as she was engaged in playing cards, what made her that way? I recalled, whimsically, the remark of a small child of my acquaintance whose mother had been suffering from a devastating sick-headache. Lillian's father had remarked: 'Don't trouble Mother, my dear. Mother's not herself this afternoon, you see.'

'Well,' countered the puzzled Lillian, 'who is she, then, Daddy?'

It was, indeed, in this present case, quite as though Mrs. Lorriquer were somebody else, somebody quite different from 'herself' whenever she sat at the cardtable. That was as far as I could get with my attempt at any 'explanation.'

The 'somebody else,' as I thought the matter through, had three known characteristics. First, an incredibly ugly disposition. Second, the ability to speak fluently a language unknown to Mrs. Lorriquer. Third, at least as manifested on one occasion, and evidenced by no more than the booming utterance of a single word, a deep, manlike, bass voice!

I stopped there in my process of reasoning. The whole thing was too absurdly bizarre for me to waste any more time over it along that line of reasoning. As to the obvious process of consulting Colonel Lorriquer or Mrs. Preston, their daughter, on such a subject, that was, sheerly, out of the question. Interesting as the problem was to me, one simply does not do such things.

THEN, quite without any warning, there came another piece of evidence. I have mentioned our St. Thomas Cha-Chas, and also that Mrs. Lorriquer was accustomed to visit the marketplace in person in the interest of her table. The St. Thomas Cha-Chas form a self-sustaining, self-contained community as distinct from the rest of the life which surrounds them in their own 'village' set on the seashore to the west of the main portion of the town as oil from water. They have been there from time immemorial, the local 'poor whites,' hardy fishermen, faithful workers, the women great sellers of small hand-made articles (like the famous grass skirts) and garden produce. They are inbred, from a long living in a very small community of their own, look mostly all alike, and, coming as they did many years ago from the French island of St. Bartholomew, most of them when together speak a kind of modified Norman French, a peasant dialect of their own, although all of them know and use a simplified variety of our English tongue for general purposes.

Along the streets, as well as in the public marketplace, the Cha-Cha women may be seen, always separate from the Negress market-vendors, offering their needlework, their woven grass baskets and similar articles, and the varying seasonal fruits and vegetables which they cultivate in their tiny garden patches or gather from the more inaccessible distant groves and ravines of the island—mangoes, palmets, sugar-apples, the strange-appearing cashew fruits, every variety of local eatable including trays of the most villainous-appearing peppermint candy, which, upon trial, is a truly delicious confection.

Passing the market one morning I saw Mrs. Lorriquer standing in a group of five or six Cha-Cha market women who were outvying one another in presenting the respective claims of various trays loaded with the small, red, round tomatoes in which certain Cha-Cha families specialize. One of the women, in her eagerness to attract the attention of the customer, jostled another, who retaliated upon her in her own familiar tongue. An argument among the women broke out at this, several taking sides, and in an instant Mrs. Lorriquer was the center of a tornado of vocables in Cha-Cha French.

Fearing that this would be annoying to her, I hastened across the street to the marketplace, toward the group, but my interference proved not to be required. I was, perhaps, halfway across when Mrs. Lorriquer took charge of the situation herself and with an effectiveness which no one could have anticipated. In that same booming voice with which she had ejaculated 'Sapristi!' and in fluent, positively Apache French, Mrs. Lorriquer suddenly put a benumbing silence upon the bickering market women, who fell back from her in an astounded silence, so sudden a silence that clear and shrill came the comment from a near-by Black woman balancing a tray loaded to the brim with avocado pears upon her kerchiefed head, listening, pop-eyed, to the altercation: 'Ooh, me Gahd!' remarked the Negress to the air about her. 'Whoite missy tahlk to they in Cha-Cha!'

It was only a matter of seconds before I was at Mrs. Lorriquer's side.

'Can I be of any assistance?' I inquired.

Mrs. Lorriquer glared at me, looking precisely as she did when engaged in one of her querulous, acrimonious arguments at the cardtable. Then her countenance changed with a startling abruptness, and she looked quite as usual.

'I was just buying some of these lovely little tomatoes,' she said.

The Cha-Cha women, stultified, huddled into a cowering knot, looked at her speechlessly, their red faces several shades paler than their accustomed brick-color. The one whose tray Mrs. Lorriquer now approached shrank back from her. I do not wonder, after the blast which this gentle-looking little American lady had but now let loose upon them all. The market seemed unusually quiet. I glanced about. Every eye was upon us. Fortunately, the marketplace was almost empty of customers.

'I'll take two dozen of these,' said Mrs. Lorriquer. 'How much are they, please?'

The woman counted out the tomatoes with hands trembling, placed them carefully in a paper bag, handed them to Mrs. Lorriquer, who paid her. We stepped down to the ground from the elevated concrete floor of the market.

'They seem so subdued—the poor souls!' remarked Mrs. Lorriquer, whose goggle-eyed chauffeur, a boy as black as ebony, glanced at her out of the corner of a fearfully rolled eye as he opened the door of her car.

'Come to luncheon,' said Mrs. Lorriquer, sweetly, beaming at me, 'and help us eat these nice little tomatoes. They are delicious with mayonnaise after they are blanched and chilled.' It seemed rather an abrupt contrast, these homely words of invitation, after what I had heard her call those Cha-Cha women.

'I'll come, with pleasure,' I replied.

'One o'clock, then,' said Mrs. Lorriquer, nodding and smiling, as her Black Hans turned the car skillfully and started along the Queen's Road toward the center of town.

WE did not play cards that afternoon after luncheon, because Mrs. Lorriquer and Mrs. Preston were going to an afternoon party at the residence of the Government Secretary's wife, and Colonel Lorriquer and I sat, over our coffee, on the west gallery of the house out of reach of the blazing early-afternoon sun, and chatted.

We got upon the subject of the possibility of another isthmian canal, the one tentatively proposed across Nicaragua.

'That, as you know, Mr. Canevin, was one of the old French Company's proposals, before they settled down to approximately the present site—the one we followed out—back in the late Seventies.'

'De Lesseps,' I murmured.

'Yes,' said the Colonel, musingly, 'yes—a very complex matter it was, that French proposal. They never could, it seems, have gone through with it, as a matter of fact—the opposition at home in France, the underestimate of the gross cost of excavation, the suspicion of "crookedness" which arose—they impeached the Count de Lesseps finally, you know, degraded him, ruined the poor fellow. And then, the sanitation question, you know. If it had not been for our Gorgas and his marvelous work in that direction—'

'Tell me,' I interrupted, 'just how long were the French at work on their canal, Colonel?'

'Approximately from 1881 to 1889,' replied the Colonel, 'although the actual work of excavation, the bulk of the work, was between '85 and '89. By the way, Canevin, we lived in a rather unusual house there. Have I ever mentioned that to you?'

'Never,' said I. 'What was the unusual element about your house?'

'Only that it was believed to be haunted,' replied the Colonel; 'although, I must admit, I never—we never—met with the least evidence outside the superstitions of the people. Our neighbors all believed it to be haunted in some way. We got it for a song for that reason and it was a very pleasant place. You see, it had been fitted up, quite regardless of the cost, as a kind of public casino or gambling-house, about 1885, and it had been a resort for de Lesseps's crowd for the four years before the French Company abandoned their work. It was a huge place, with delightful galleries. The furniture, too, was excellent. We took it as it stood, you see, and, beyond a terrific job to get it clean and habitable, it was a very excellent investment. We were there for more than three years altogether.'

An idea, vague, tenuous, grotesque enough in all truth, and, indeed, somewhat less than half formed, had leaped into my mind at the combination of a 'haunted' residence and the French work on the ill-fated de Lesseps canal project.

'Indeed!' said I. 'It certainly sounds interesting. And do you know, Colonel, who ran the old casino; who, so to speak, was the proprietor—unless it was a part of the Company's scheme for keeping their men interested?'

'It was privately managed,' returned the Colonel, 'and, queerly enough, as it happens, I can show you a photograph of the former proprietor. He was a picturesque villain!' The Colonel rose and started to go inside the house from where we sat on the cool gallery. He paused at the wide doorway, his hand on the jamb.

'It was the proprietor who was supposed to haunt the house,' said he, and went inside.

My mind reeled under the stress of these clues and the attempts, almost subconscious—for, indeed, I had thought much of the possible problem presented by Mrs. Lorriquer's case; a 'case' only in my own imagination, so far; and I had constructed tentatively three or four connected theories by the time the Colonel returned, a large, stiff, cabinet photograph in his hand. He laid this on the table between us and resumed his Chinese rattan lounge-chair. I picked up the photograph.

It was the portrait, stiffly posed, the hand, senatorially, in the fold of the long, black surtout coat, of the sort anciently known as a Prince Albert, of a rather small, emaciated man, whose face was disfigured by the pittings of smallpox; a man with a heavy head of jet-black hair, carefully combed after a fashion named, in our United States, for General McClellan of Civil War fame, the locks brushed forward over the tops of the ears, and the parting, although this could not be seen in the front-face photograph, extending all the way down the back to the neck. A 'croupier's' mustache, curled and waxed ferociously, ornamented the sallow, sinister features of a face notable only for its one outstanding feature, a jaw as solid and square as that of Julius Caesar. Otherwise, as far as character was concerned, the photograph showed a very unattractive person, the type of man, quite obviously, who in these modern times would inevitably have followed one of our numerous and varied 'rackets' and probably, one imagined, with that jaw to help, successfully!

'And how, if one may ask,' said I, laying the photograph down on the table again, 'did you manage to get hold of this jewel, Colonel Lorriquer?'

The old gentleman laughed. 'We found it in the back end of a bureau drawer,' said he. 'I have mentioned that we took the house over just as it was. Did you notice the cameo?'

'Yes,' I replied, picking the photograph up once more to look at the huge breast-pin which seemed too large in the picture even for the enormous 'de Joinville' scarf which wholly obliterated the shirt-front underneath.

'It is certainly a whopper!' I commented. 'It reminds me of that delightful moving picture Cameo Kirby, if you happened to see it some time ago, on the silent screen.'

'Quite,' agreed Colonel Lorriquer. 'That, too, turned up, and in the same ancient bureau, when we were cleaning it. It was wedged in behind the edge of the bottom-board of the middle drawer. Of course you have observed that Mrs. Lorriquer wears it?'

I had, and said so. The enormous breast-pin was the same which I had many times observed upon Mrs. Lorriquer. It seemed a favorite ornament of hers. I picked up the photograph once more.

Down in the lower right-hand corner, in now faded gilt letters of ornamental scrollwork, appeared the name of the photographer. I read: 'La Palma, Quezaltenango.'

'"Quezaltenango,"' I read aloud. 'That is in Guatemala. Was the "Gentleman of the house", perhaps, a Central American? It would be hard to guess at his nationality from this. He looks a citizen of the world!'

'No,' replied the Colonel, 'he was a Frenchman, and he had been, as it appears, living by his wits all over Central America. When the work of construction actually began under the French Company—that was in 1885—there was a rush of persons like him toward the pickings from so large a group of men who would be looking for amusement, and this fellow came early and stayed almost throughout the four years. His name was Simon Legrand, and, from what I gathered about him, he was a very ugly customer.'

'You remarked that he was connected with the alleged haunting,' I ventured. 'Is there, perhaps, a story in that?'

'Hardly a story, Mr. Canevin. No. It was merely that toward the end of the French Company's activities, in 1889, Legrand, who had apparently antagonized all his patrons at his casino, got into a dispute with one of them, over a game of piquet or écarté—one of those French games of some kind, perhaps even vingt-et-un, for all I know, or even chemin-de-fer—and Simon went up to his bedroom, according to the story, to secure a pistol, being, for the time, rather carelessly in that company, unarmed. His "guest" followed him upstairs and shot him as he stood in front of the bureau where he kept his weapon, from the bedroom doorway, thus ending the career of what must have been a very precious rascal. Thereafter, the French Company's affairs and that of the casino being abruptly dissolved at about the same time, the rumor arose that Legrand was haunting his old quarters. Beyond the rumor, there never seemed anything to suggest its basis in anything but the imagination of the native Panamanians. As I have mentioned, we lived in the house three years, and it was precisely like any other house, only rather cheap, which satisfied us very well!'

THAT, as a few cautious questions, put diplomatically, clearly showed, was all the Colonel knew about Simon Legrand and his casino. I used up all the questions I had in mind, one after another, and, it being past three in the afternoon, and over time for the day's siesta, I was about to take my leave in search of forty winks and the afternoon's shower-bath, when the Colonel volunteered a singular piece of information. He had been sitting rather quietly, as though brooding, and it was this, which I attributed to the after-luncheon drowsiness germane to these latitudes, which had prompted me to go. I was, indeed, rising from my chair at the moment, when the Colonel remarked: 'One element of the old casino seemed to remain—perhaps that was the haunting!' He stopped, and I hung, poised, as it were, to catch what he might be about to say. He paused, however, and I prompted him.

'And what might that be, sir?' I asked, very quietly. The Colonel seemed to come out of his revery.

'Eh?' he said, 'eh, what?' He looked at me rather blankly.

'You were remarking that one element of the old casino's influence seemed to remain in your Canal Zone residence,' said I.

'Ah—yes. Why, it was strange, Mr. Canevin, distinctly strange. I have often thought about it; although, of course, it was the merest coincidence, unless—perhaps—well, the idea of suggestion might come into play. Er—ah—er, what I had in mind was that—er—Mrs. Lorriquer you know—she began to take up card-playing there. She had never, to my knowledge, played before; had never cared for cards in the least; been brought up, in early life, to regard them as not quite the thing for a lady and all that, you see. Her mother, by the way, was Sarah Langhorne—perhaps you had not heard this, Mr. Canevin—the very well-known medium of Bellows Falls, Vermont. The old lady had quite a reputation in her day. Strictly honest, of course! Old New England stock—of the very best, sir. Strait-laced! Lord—a card in the house would have been impossible! Cards, in that family! "The Devil's Bible," Mr. Canevin. That was the moral atmosphere which surrounded my wife's formative days. But—no sooner had we begun to live in that house down there, than she developed "card sense", somehow, and she has found it—er—her chief interest, I should say, ever since.' The old Colonel heaved a kind of mild sigh, and that was as near as I had heard to any comment on his wife's outrageous conduct at cards, which must, of course, have been a major annoyance in the old gentleman's otherwise placid existence.

I WENT home with much material to ponder. I had enough to work out a more or less complete 'case' now, if, indeed, there was an occult background for Mrs. Lorriquer's diverse conduct, her apparently subconscious use of colloquial French, and—that amazing deep bass voice!

Yes, all the elements seemed to be present now. The haunted house, with that scar-faced croupier as the haunter; the sudden predilection for cards emanating there; the initial probability of Mrs. Lorriquer's susceptibility to discarnate influences, to a 'control,' as the spiritualists name this phenomenon—the cameo—all the rest of it; it all pointed straight to one conclusion, which, to put it conservatively, might be described as the 'influence' of the late Simon Legrand's personality upon kindly Mrs. Lorriquer who had 'absorbed' it in three years' residence in a house thoroughly impregnated by his ugly and unpleasant personality.

I let it go at that, and—it must be understood—I was only halfway in earnest at the time, in even attempting to attribute to this 'case' anything like an occult background. One gets to look for such explanations when one lives in the West Indies where the very atmosphere is charged with Magic!

But—my inferences, and whereunto these led, were, at their most extreme, mild, compared with what was, within two days, to be revealed to us all. However, I have resolved to set this tale down in order, as it happened, and again I remind myself that I must not allow myself to run ahead of the normal sequence of events. The dénouement, however, did not take very long to occur.

It was, indeed, no more than two days later, at the unpropitious hour of two-fifteen in the morning—I looked at my watch on my bureau as I was throwing on a few necessary clothes—that I was aroused by a confused kind of tumult outside, and, coming into complete wakefulness, observed an ominous glow through my windows and realized that a house, quite near by, was on fire.

I leaped at once out of bed, and took a better look, with my head out the window. Yes, it was a fire, and, from appearances, the makings of a fine—and very dangerous—blaze here in the heart of the residence district where the houses, on the sharp side-hill, are built very close together.

It was a matter of moments before I was dressed, after a fashion, and outside, and running down the path to my gateway and thence around the corner to the left. The fire itself, as I now saw at a glance, was in a wooden building now used as a garage, directly on the roadway before one of the Denmark Hill's ancient and stately mansions. Already a thin crowd, of Negroes entirely, had gathered, and I saw that I was 'elected' to take charge in the absence of any other white man, when I heard, with relief, the engine approaching. Our Fire Department, while not hampered with obsolete apparatus, is somewhat primitive. The engine rounded the corner, and just behind it, a Government Ford, the 'transportation' apportioned to Lieutenant Farnum of Uncle Sam's efficient Marines. The Lieutenant, serving as the Governor's Legal Aide, had, among his fixed duties, the charge of the Fire Department. This highly efficient young gentleman, whom I knew very well, was at once in the very heart of the situation, had the crowd back away to a reasonable distance, the fire engine strategically placed, and a double stream of chemicals playing directly upon the blazing shack.

The fire, however, had had a long start, and the little building was in a full blaze. It seemed, just then, doubtful whether or not the two streams would prove adequate to put it out. The real danger, however, under the night trade wind, which was blowing lustily, was in the spread of the fire, through flying sparks, of which there were many, and I approached Lieutenant Farnum offering cooperation.

'I'd suggest waking up the people—in that house, and that, and that one,' directed Lieutenant Farnum, denoting which houses he had in mind.

'Right!' said I, 'I'm shoving right off!' And I started down the hill to the first of the houses. On the way I was fortunate enough to meet my houseboy, Stephen Penn, an intelligent young Negro, and him I dispatched to two of the houses which stood together, to awaken the inmates if, indeed, the noise of the conflagration had not already performed that office. Then I hastened at a run to the Criqué place, occupied by the Lorriquer family, the house farthest from the blaze, yet in the direct line of the sparks and blazing silvers which the trade wind carried in a thin aerial stream straight toward it.

Our servants in West Indian communities never remain for the night on the premises. The Lorriquers would be, like all other Caucasians, alone in their house. I had, as it happened, never been upstairs in the house; did not, therefore, have any idea of its layout, nor knew which of the bedrooms were occupied by the several members of the family.

Without stopping to knock at the front entrance door, I slipped the latch of a pair of jalousies leading into the 'hall' or drawing room, an easy matter to negotiate, stepped inside across the window-sill, and, switching on the electric light in the lower entranceway, ran up the broad stone staircase to the floor above. I hoped that chance would favor me in finding the Colonel's room first, but as there was no way of telling, I rapped on the first door I came to, and, turning the handle—this was an emergency—stepped inside, leaving the door open behind me to secure such light as came from the single bulb burning in the upper hallway.

I stepped inside.

AGAIN, pausing for an instant to record my own sensations as an integral portion of this narrative, I hesitate, but this time only because of the choices which lie before me in telling, now long afterward, with the full knowledge of what was involved in this strange case, precisely what I saw; precisely what seemed to blast my eyesight for its very incredibleness—its 'impossibility.'

I had, it transpired, hit upon Mrs. Lorriquer's bedroom, and there plain before me—it was a light, clear night, and all the eight windows stood open to the starlight and what was left of a waning moon—lay Mrs. Lorriquer on the stub-posted mahogany four-poster with its tester and valance. The mosquito-net was not let down, and Mrs. Lorriquer, like most people in our climate, was covered, as she lay in her bed, only with a sheet. I could, therefore, see her quite plainly, in an excellent light.

But—that was not all that I saw.

For, beside the bed, quite close in fact, stood—Simon Legrand—facing me, the clothes, the closely buttoned surtout, the spreading, flaring de Joinville scarf, fastened with the amazing brooch, the pock-marked, ill-natured face, the thick, black hair, the typical croupier mustache, the truculent expression, Simon Legrand, to the last detail, precisely as he appeared in the cabinet photograph of La Palma of Quezaltenango—Simon Legrand to the life.

And, between him as he stood there, glaring truculently at me, intruding upon his abominable manifestation, and the body of Mrs. Lorriquer, as I glared back at this incredible configuration, there stretched, and wavered, and seemed to flow, toward him and from the body of Mrs. Lorriquer, a whitish, tenuous stream of some milky-looking material—like a waved sheet, like a great mass of opaque soap-bubbles, like those pouring grains of attenuated plasma described in Dracula, when in the dreadful castle in Transylvania, John Harker stood confronted with the materialization of that arch-fiend's myrmidons.

All these comparisons rushed through my mind, and, finally, the well-remembered descriptions of what takes place in the 'materialization' of a 'control' at a mediumistic séance when material from the medium floats toward and into the growing incorporation of the manifestation, building up the non-fictitious body through which the control expresses itself.

All this, I say, rushed through my mind with the speed of thought, and recorded itself so that I can easily remember the sequence of these ideas. But, confronted with this utterly unexpected affair, what I did, in actuality, was to pause, transfixed with the strangeness, and to mutter, 'My God!'

Then, shaking internally, pulling myself together by a mighty effort while the shade or manifestation or whatever it might prove to be, of the French gambler glowered at me murderously, in silence, I made a great effort, one of those efforts which a man makes under the stress of utter necessity. I addressed the figure—in French!

'Good-morning, Monsieur Legrand,' said I, trying to keep the quaver out of my voice. 'Is it too early, think you, for a little game of écarté?'

Just how, or why, this sentence formed itself in my mind, or, indeed, managed to get itself uttered, is to this day, a puzzle to me. It seemed just then the one appropriate, the inevitable way, to deal with the situation. Then—

In the same booming bass which had voiced Mrs. Lorriquer's 'Sapristi,' a voice startlingly in contrast with his rather diminutive figure, Simon Legrand replied: 'Oui, Monsieur, at your service on all occasions, day or night—you to select the game!'

'Eh bien, donc—' I began when there came an interruption in the form of a determined masculine voice just behind me.

'Put your hands straight up and keep them there!'

I turned, and looked straight into the mouth of Colonel Lorriquer's service revolver; behind it the old Colonel, his face stern, his steady grip on the pistol professional, uncompromising.

At once he lowered the weapon.

'What—Mr. Canevin!' he cried. 'What—'

'Look!' I cried back at him, 'look, while it lasts, Colonel!' and, grasping the old man's arm, I directed his attention to the now rapidly fading form or simulacrum of Simon Legrand. The Colonel stared fixedly at this amazing sight.

'My God!' He repeated my own exclamation. Then—'It's Legrand, Simon Legrand, the gambler!'

I explained, hastily, disjointedly, about the fire. I wanted the Colonel to understand, first, what I was doing in his house at half-past two in the morning. That, at the moment, seemed pressingly important to me. I had hardly begun upon this fragmentary explanation when Mrs. Preston appeared at the doorway of her mother's room.

'Why, it's Mr. Canevin!' she exclaimed. Then, proceeding, 'There's a house on fire quite near by, Father—I thought I'd best awaken you and Mother.' Then, seeing that, apart from my mumbling of explanations about the fire, both her father and I were standing, our eyes riveted to a point near her mother's bed, she fell silent, and not unnaturally, looked in the same direction. We heard her, behind us, her voice now infiltrated with a sudden alarm: 'What is it?—what is it? Oh, Father, I thought I saw—'

The voice trailed out into a whisper. We turned, simultaneously, thus missing the very last thin waning appearance of Simon Legrand as the stream of tenuous, wavering substance poured back from him to the silent, immobile body of Mrs. Lorriquer motionless on its great bed, and the Colonel was just in time to support his daughter as she collapsed in a dead faint.

All this happened so rapidly that it is out of the question to set it down so as to give a mental picture of the swift sequence of events.

The Colonel, despite his character and firmness, was an old man, and not physically strong. I therefore lifted Mrs. Preston and carried her to a day-bed which stood along the wall of the room and there laid her down. The Colonel rubbed her hands. I fetched water from the mahogany washstand such as is part of the furnishing of all these old West Indian residence bedrooms, and sprinkled a little of the cool water on her face. Within a minute or two her eyelids fluttered, and she awakened. This secondary emergency had naturally diverted our attention from what was toward at Mrs. Lorriquer's beside. But now, leaving Mrs. Preston who was nearly herself again, we hastened over to the bed.

Mrs. Lorriquer, apparently in a very deep sleep, and breathing heavily, lay there, inert. The Colonel shook her by the shoulder; shook her again. Her head moved to one side, her eyes opened, a baleful glare in her eyes.

'Va t'en, sâle bête!' said a deep manlike voice from between her clenched teeth. Then, a look of recognition replacing the glare, she sat up abruptly, and, in her natural voice, addressing the Colonel whom she had but now objurgated as a 'foul beast,' she asked anxiously: 'Is anything the matter, dearest? Why—Mr. Canevin—I hope nothing's wrong!'

I told her about the fire.

In the meantime Mrs. Preston, somewhat shaky, but brave though puzzled over the strange happenings which she had witnessed, came to her mother's bedside. The Colonel placed an arm about his daughter, steadying her.

'Then we'd better all get dressed,' said Mrs. Lorriquer, when I had finished my brief account of the fire, and the Colonel and I and Mrs. Preston walked out of the bedroom. Mrs. Preston slipped into her own room and closed the door behind her.

'Get yourself dressed, sir,' I suggested to the old Colonel, 'and I will wait for you on the front gallery below.' He nodded, retired to his room, and I slipped downstairs and out to the gallery, where I sank into a cane chair and lit a cigarette with shaking fingers.

THE Colonel joined me before the cigarette was smoked through. He went straight to the point.

'For God's sake, what is it, Canevin?' he inquired, helplessly.

I had had time to think during the consumption of that cigarette on the gallery. I had expected some such direct inquiry as this, and had my answer ready.

'There is no danger—nothing whatever to worry yourself about just now, at any rate,' said I, with a positive finality which I was far from feeling internally. I was still shaken by what I had seen in that airy bedroom. 'The ladies will be down shortly. We can not talk before them. Besides, the fire may, possibly, be dangerous. I will tell you everything I know tomorrow morning. Come to my house at nine, if you please, sir.'

The old Colonel showed his army training at this.

'Very well, Mr. Canevin,' said he, 'at nine tomorrow, at your house.'

Lieutenant Farnum and his efficient direction proved too much for the fire. Within a half-hour or so, as we sat on the gallery, the ladies wearing shawls because of the cool breeze, my houseboy, Stephen, came to report to me that the fire was totally extinguished. We had seen none of its original glare for the past quarter of an hour. I said goodnight, and the Lorriquer family retired to make up its interrupted sleep, while I walked up the hill and around the corner to my own house and turned in. The only persons among us all who had not been disturbed that eventful night were Mrs. Preston's two small children. As it would be a simple matter to take them to safety in case the fire menaced the house, we had agreed to leave them as they were, and they had slept quietly throughout all our alarms and excursions!

THE old Colonel looked his full seventy years the next morning when he arrived at my house and was shown out upon the gallery by Stephen, where I awaited him. His face was strained, lined, and ghastly.

'I did not sleep at all the rest of the night, Mr. Canevin,' he confessed, 'and four or five times I went to my wife's room and looked in, but every time she was sleeping naturally. What do you make of this dreadful happening, sir? I really do not know which way to turn, I admit to you, sir.' The poor old man was in a truly pathetic state. I did what I could to reassure him.

I set out before him the whole case, as I have already set it out, as the details came before me, throughout the course of this narrative. I went into all the details, sparing nothing, even the delicate matter of Mrs. Lorriquer's conduct over the cardtable. Summing up the matter I said: 'It seems plain, from all this testimony, that Simon Legrand's haunting of his old house which you occupied for three years was more of an actuality than your residence there indicated to you. His sudden death at the hands of one of his "guests" may very well have left his personality, perhaps fortified by some unfulfilled wish, about the premises which had been his for a number of years previously. There are many recorded cases of similar nature in the annals of scientific occult investigation. Such a "shade", animated by some compelling motive to persist in its earthly existence, would "pervade" such premises already en rapport with his ways and customs.

'Then, for the first time, the old house was refurbished and occupied when you moved into it. Mrs. Lorriquer may be, doubtless is, I should suppose from the evidence we already have, one of those persons who is open to what seems to have happened to her. You mentioned her mother, a well-known medium of years ago. Such qualifications may well be more or less hereditary you see.

'That Legrand laid hold upon the opportunity to manifest himself through her, we already know. Both of us have seen him "manifested", and in a manner typical of mediumistic productions, in material form, of their "controls". In this case, the degree of "control" must be very strong, and, besides that, it has, plainly, been growing. The use of French, unconsciously, the very tone of his deep bass voice, also unconscious on her part, and—I will go farther, Colonel; there is another, and a very salient clue for us to use. You spoke of the fact that previous to your occupancy of the Legrand house in the "zone" Mrs. Lorriquer never played cards. Obviously, if the rest of my inferences are correct, this desire to play cards came direct from Legrand, who was using her for his own self-expression, having, in some way, got himself en rapport with her as her "control". I would go on, then, and hazard the guess that just as her use of French is plainly subconscious, as is the use of Legrand's voice, on occasion—you will remember, I spoke to him before you came into the room last night, and he answered me in that same deep voice—so her actual playing of cards is an act totally unconscious on her part, or nearly so. It is a wide sweep of the imagination, but, I think, it will be substantiated after we have released her from this obsession, occupation by another personality, or whatever it proves to be.'

The word 'release' seemed to electrify the old gentleman. He jumped out of his chair, came toward me, his lined face alight with hope.

'Is there any remedy, Mr. Canevin? Can it be possible? Tell me, for God's sake, you can not understand how I am suffering—my poor wife! You have had much experience with this sort of thing; I, none whatever. It has always seemed—well, to put it bluntly, a lot of "fake" to me.'

'Yes,' said I, slowly, 'there is a remedy, Colonel—two remedies, in fact. The phenomenon with which we are confronted seems a kind of combination of mediumistic projection of the "control", and plain, old-fashioned "possession." The Bible, as you will recall, is full of such cases—the Gadarene Demoniac, for example. So, indeed, is the ecclesiastical history through the Middle Ages. Indeed, as you may be aware, the "order" of exorcist still persists in at least one of the great historic churches. One remedy, then, is exorcism. It is unusual, these days, but I am myself familiar with two cases where it has been successfully performed, in Boston, Massachusetts, within the last decade. A salient point, if we should resort to that, however, is Mrs. Lorriquer's own religion. Exorcism can not, according to the rules, be accorded to everybody. The bare minimum is that the subject should be validly baptized. Otherwise exorcism is inoperative; it does not work as we understand its mystical or spiritual processes.'

'Mrs. Lorriquer's family were all Friends—Quakers,' said the Colonel. 'She is not, to my knowledge, baptized. Her kind of Quakers do not, I believe, practise baptism.'

'Well, then,' said I, 'there is another way, and that, with your permission, Colonel, I will outline to you.'

'I am prepared to do anything, anything whatever, Mr. Canevin, to cure this horrible thing for my poor wife. The matter I leave entirely in your hands, and I will cooperate in every way, precisely as you say.'

'Well said sir!' I exclaimed, and forthwith proceeded to outline my plan to the Colonel...

PERHAPS there are some who would accuse me of being superstitious. As to that I do not know, and, quite frankly, I care little. However, I record that that afternoon I called on the rector of my own church in St. Thomas, the English Church, as the native people still call it, although it is no longer, now that St. Thomas is American territory, under the control of the Archbishop of the British West Indies as it was before our purchase from Denmark in 1917. I found the rector at home and proffered my request. It was for a vial of holy water. The rector and I walked across the street to the church and there in the sacristy, without comment, the good gentleman, an other-worldly soul much beloved by his congregation, provided my need. I handed him a twenty-franc note, for his poor, and took my departure, the bottle in the pocket of my white drill coat.

That evening, by arrangement with the Colonel, we gathered for an evening of cards at the Lorriquers.' I have never seen Mrs. Lorriquer more typically the termagant. She performed all her bag of tricks, such as I have recorded, and, shortly after eleven, when we had finished, Mrs. Preston's face wore a dull flush of annoyance and, when she retired, which she did immediately after we had calculated the final score, she hardly bade the rest of us goodnight.

Toward the end of the play, once more I happened to hold a commanding hand, and played it out to a successful five no-trump, bid and made. All through the process of playing that hand, adverse to Mrs. Lorriquer and her partner, I listened carefully to a monotonous, ill-natured kind of undertone chant with which she punctuated her obvious annoyance. What she was saying was: 'Nom de nom, de nom, de nom, de nom—' precisely as a testy, old-fashioned, grumbling Frenchman will repeat those nearly meaningless syllables.

Mrs. Lorriquer retired not long after her daughter's departure upstairs, leaving the Colonel and me over a pair of Havana cigars.

WE waited, according to our prearranged plan, downstairs there, until one o'clock in the morning.

Then the Colonel, at my request, brought from the small room which he used as an office or den, the longer of a very beautiful pair of Samurai swords, a magnificent weapon, with a blade as keen and smooth as any razor. Upon this, with a clean handkerchief, I rubbed half the contents of my holy water, not only upon the shimmering, inlaid, beautiful blade, but over the hand-grip as well.

Shortly after one, we proceeded, very softly, upstairs, and straight to the door of Mrs. Lorriquer's room, where we took up our stand outside. We listened, and within there was no sound of any kind whatever.

From time to time the Colonel, stooping, would peer in through the large keyhole, designed for an enormous, old-fashioned, complicated key. After quite a long wait, at precisely twenty minutes before two a.m. the Colonel, straightening up again after such an inspection, nodded to me. His face, which had regained some of its wonted color during the day, was a ghastly white, quite suddenly, and his hands shook as he softly turned the handle of the door, opened it, and stood aside for me to enter, which I did, he following me, and closing the door behind him. Behind us, in the upper hallway, and just beside the door-jamb, we had left a large, strong wicker basket, the kind designed to hold a family washing.

Precisely as she had lain the night before, was Mrs. Lorriquer, on the huge four-poster. And, beside her, the stream of plasma flowing from her to him, stood Simon Legrand, glowering at us evilly.

I advanced straight upon him, the beautiful knightly sword of Old Japan firmly held in my right hand, and as he shrank back, stretching the plasma stream to an extreme tenuity—like pulled dough it seemed—I abruptly cut though this softly-flowing material directly above the body of Mrs. Lorriquer with a transverse stroke. The sword met no apparent resistance as I did so, and then, without any delay, I turned directly upon Legrand, now muttering in a deep bass snarl, and with an accurately timed swing of the weapon, sheared off his head. At this stroke, the sword met resistance, comparable, perhaps, as nearly as I can express it, to the resistance which might be offered by the neck of a snowman built by children.

The head, bloodlessly, as I had anticipated, fell to the floor, landing with only a slight, soft sound, rolled a few feet, and came to a pause against the baseboard of the room. The decapitated body swayed and buckled toward my right, and before it gave way completely and fell prone upon the bedroom floor, I had managed two more strokes, the first through the middle of the body, and the second a little above the knees.

Then, as these large fragments lay upon the floor, I chopped them, lightly, into smaller sections.

As I made the first stroke, that just above Mrs. Lorriquer, severing the plasma stream, I heard from her a long, deep sound, like a sigh. Thereafter she lay quiet. There was no motion whatever from the sundered sections of 'Simon Legrand' as these lay, quite inert, upon the floor, and, as I have indicated, no flow of blood from them. I turned to the Colonel, who stood just at my shoulder witnessing this extraordinary spectacle.

'It worked out precisely as we anticipated,' I said. 'The horrible thing is over and done with, now. It is time for the next step.'

The old Colonel nodded, and went to the door, which he opened, and through which he peered before stepping out into the hallway. Plainly we had made no noise. Mrs. Preston and her babies were asleep. The Colonel brought the clothes-basket into the room, and rather gingerly at first, we picked up the sections of what had been 'Simon Legrand.' They were surprisingly light, and, to the touch, felt somewhat like soft and pliant dough. Into the basket they went, all of them, and, carrying it between us—it seemed to weigh altogether no more than perhaps twenty pounds at the outside—we stepped softly out of the room, closing the door behind us, down the stairs, and out, through the dining room and kitchen into the walled backyard.

Here, in the corner, stood the wire apparatus wherein papers and light trash were burned daily. Into this, already half filled with various papers, the Colonel poured several quarts of kerosene from a large five-gallon container fetched from the kitchen, and upon this kindling we placed carefully the strange fragments from our clothes-basket. Then I set a match to it, and within ten minutes there remained nothing except small particles of unidentifiable trash, of the simulacrum of Simon Legrand.

We returned, softly, after putting back the kerosene and the clothes-basket where they belonged, into the house, closing the kitchen door after us. Again we mounted the stairs, and went into Mrs. Lorriquer's room. We walked over to the bed and looked at her. She seemed, somehow, shrunken, thinner than usual, less bulky, but, although there were deep unaccustomed lines showing in her relaxed face, there was, too, upon that face, the very ghost of a kindly smile.

'It is just as you said it would be, Mr. Canevin,' whispered the Colonel as we tiptoed down the stone stairway. I nodded.

'We will need an oiled rag for the sword,' said I. 'I wet it very thoroughly, you know.'

'I will attend to that,' said the Colonel, as he gripped my hand in a grasp of surprising vigor.

'Goodnight, sir,' said I, and he accompanied me to the door.

THE Colonel came in to see me about ten the next morning. I had only just finished a late 'tea,' as the early morning meal, after the Continental fashion, is still named in the Virgin Islands. The Colonel joined me at the table and took a late cup of coffee.

'I was sitting beside her when she awakened, a little before nine,' he said, 'and as she complained of an "all-gone" feeling, I persuaded her to remain in bed, "for a couple of days". She was sleeping just now, very quietly and naturally, when I ran over to report.'

I called the following morning to inquire for Mrs. Lorriquer. She was still in bed, and I left a polite message of goodwill.

It was a full week before she felt well enough to get up, and it was two days after that that the Lorriquers invited me to dinner once more. The bulletins, surreptitiously reported to me by the Colonel, indicated that, as we had anticipated, she was slowly gaining strength. One of the Navy physicians, called in, had prescribed a mild tonic, which she had been taking.

The shrunken appearance persisted, I observed, but this, considering Mrs. Lorriquer's characteristic stoutness, was, actually, an improvement at least in her general appearance. The lines of her face appeared somewhat accentuated as compared to how she had looked before the last 'manifestation' of the 'control.' Mrs. Preston seemed worried about her mother, but said little. She was rather unusually silent during dinner, I noticed.

I had one final test which I was anxious to apply. I waited for a complete pause in our conversation toward the end of a delightful dinner, served in Mrs. Lorriquer's best manner.

'And shall we have some Contract after dinner this evening?' I inquired, addressing Mrs. Lorriquer.

She almost blushed, looked at me deprecatingly.

'But, Mr. Canevin, you know—I know nothing of cards,' she replied.

'Why, Mother!' exclaimed Mrs. Preston from across the table, and Mrs. Lorriquer looked at her in what seemed to be evident puzzlement. Mrs. Preston did not proceed, I suspect because her father touched her foot for silence under the table. Indeed, questioned, he admitted as much to me later that evening.

The old gentleman walked out with me, and halfway up the hall when I took my departure a little before eleven, after an evening of conversation punctuated by one statement of Mrs. Lorriquer's, made with a pleasant smile through a somewhat rueful face.

'Do you know, I've actually lost eighteen pounds, Mr. Canevin, and that being laid up in bed only eight or nine days. It seems incredible, does it not? The climate, perhaps—'

'Those scales must have been quite off,' vouchsafed Mrs. Preston.

Going up the hill with the Colonel, I remarked: 'You still have one job on your hands, Colonel.'

'Wh—what is that, Mr. Canevin?' inquired the old gentleman, apprehensively.

'Explaining the whole thing to your daughter,' said I.

'I dare say it can be managed,' returned Colonel Lorriquer. 'I'll have a hack at that later!'

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.