RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

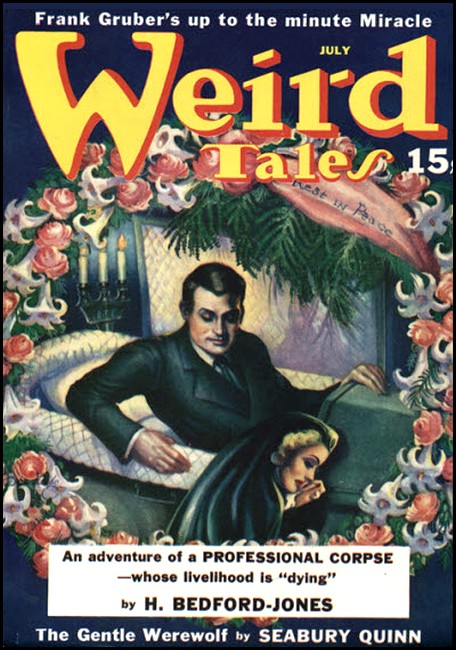

Weird Tales, July 1940, with "The Artificial Honeymoon"

I came upon the gourd bottle and did what only a young fool would do.

FOR twelve years I've earned an honest living in a strange, perhaps a horrible fashion. Nobody in the world has ever before followed my profession.

James F. Bronson is the name. I've played a chief part in the most dramatic situations, the most pitiful and heart-rending situations, which the human brain could conceive; and in each case I've been quite oblivious to all that went on. For, during these twelve years, I've been a professional corpse—a walking dead man.

You may possibly have noticed the advertisement I've run in newspapers from time to time, all over the country. You may have wondered what it meant. It was quite discreetly worded. From the very beginning I've tried to guard against any connection with crooked enterprise. As appears in the instance of the Shuteye Medium, I didn't always succeed; and elsewhere I may have been imposed upon; but to the best of my knowledge I've never been employed toward the harm of anyone, or in contravention of the law.

Here's a sample of my advertisement:

Personal!—It is possible to simulate death, as I can demonstrate to interested parties. Endorsement of medical profession, absolute discretion. All work confidential but must be legal and subject to closest investigation. News Box B543.

Had I been unscrupulous, I could have amassed a fortune through this blind ad. Each time it appeared, I've received tempting offers, some frankly illegal and others with some illegal aspect in the background.

I've never accepted one of these offers. In relating a few of my most remarkable experiences, I must protect my own identity and that of my clients; otherwise, no details will be changed or hidden. For example, in the story of the blind farmer and the strip dancer, the lady concerned is now an internationally known movie star. It would be a dastardly act even to hint at her identity. Nor do I want to do myself out of a job. Despite the thirty-one times I have been pronounced dead, and the seven times I've actually been buried, I am still in pursuit of shoes for the baby.

Before taking up my first case, the curious account of the artificial honeymoon, let me briefly sketch my history and the discovery of my singular ability.

I was born on a farm in western Canada, and had a fair education, with two years of college, before my father died and the family went broke. After drifting around and never noticing anything extraordinary about myself, I came back to the farm at the age of twenty-three, to support the womenfolk. I was broke. We were all broke.

I had an uncle who was also a drifter. He had been in South America, and turned up one fine day with a trunk full of junk, a lot of wild stories, and a cough that killed him two months later.

He had brought from Ecuador two tiny, shrunken human heads, the size of a billiard ball. He sent these off to a museum and the money helped to bury him. Among other things he had a bottle made from a gourd and filled with liquid, which he said was a sacred drink used by the Indians in Ecuador to produce dreams. He expected to make money out of it, but died before he could get anywhere with his schemes.

After his death I was going through his effects, hoping to find something that we might sell, for we had bitter need of money.

I came upon the gourd bottle and did what only a young fool would do: I sampled it. Pouring out some of the stuff I tasted it. As it seemed harmless and I was curious to see what dreams it would produce, I swallowed the whole dose.

It burned like fire. I became rapidly drowsy, and frightfully scared. I stumbled downstairs, told the folks what I had done, yelled that I was poisoned, and then keeled over, dead to the world.

It seemed that I really was dead. Naturally skinny and none too strong, I must have looked terrible. They said that my lips were really blue.

The doctor came the six miles from town in record time. He took one look at me, put his stethoscope to my chest, felt for my pulse, and said I was dead. He stuck a pin in me, and was sure of it. He hauled open my shirt and ran his fingernail over my abdomen, and there was no reflex.

Then he turned up my eyelid, held a mirror to my nose, and changed his mind at once.

"Hello! Something queer about this; he's breathing. And his pupil's not dilated," he exclaimed. "Where's that stuff he took? Where did it come from? What is it?"

NOBODY had the answers, of course. Neither did he, but

he was a shrewd man. He gave me a very careful examination,

and presently slid an injection into me. It was, as he told

me later, a fortieth grain of atropine and caffeine sodium

benzoate. This brought me around. Had it not been for the

eye pupil and the mirror test, he would have buried me.

My only sensation was of having been asleep, and I had no ill effects. Some days later he told me in plain words what a damned young fool I was, and what was amiss with me.

"Ever been examined for life insurance?"

"Never could afford luxuries, doc," I admitted.

"Hm! A queer case, Bronson; I'd better make it clear to you. First, you have bradycardia and atrial fibrillation; in plain English, a slow heart, beating barely forty to the minute, but it flutters instead of beating. Barrel chest; the heart is back from the ribs and the stethoscope doesn't get it. Naturally not," he added grimly, "because your heart is on the right side."

This was before it had become fashionable to have the heart thus misplaced.

As he explained, the slow heart and fluttering circulation killed any pulse, and accounted for my usual pallor and my bluish lips. Also, the liquid I had taken was enough to kill anyone; a little more might have actually killed me.

"I took a sample of that stuff and had it analyzed. Here's what is in the infernal concoction," and he handed me the report of the analysis. "The protopine, of course, killed the sensory nerves; there was no abdominal reflex. You had me fooled for a minute. Luckily I gave you the right hypodermic to bring you around. Don't be such a fool again. The minute you get home throw that cursed liquid of yours away."

I did nothing of the sort. Why not? Simply because, at the time, I thought I might capitalize the local notoriety this experience was bringing me. I thought of writing a story about it, and I might need the liquid as proof. So I kept it. Here is the analysis he gave me:

Anhalonium (Peyotl): 10%

Protopine: 8%

Bhang: 15%

Alcohol (Tequila): 67%

Inorganic salts, minute.

Coloring matter, type undetermined.

The local newspaper told about the young farmer who had been dead and was alive, with his heart in the wrong place. Other newspapers copied the story. A Scotch surgeon came out from Edmonton to investigate me. He thumped me, measured me, examined me minutely, and after grudgingly confirming the opinion of the local doctor, went away. (Not long ago I met him again in Los Angeles, but he failed to recognize me.) Obviously, the theory was entirely correct, for since then it has served in all my contacts with the medical fraternity.

This misadventure caused me great terror; the discovery of my peculiar physical formation preyed upon me and frightened me. And yet, as a direct result of my local notoriety, I received the first lucrative inkling that I need not consider myself doomed to an untimely end. Two men in a car with a United States license showed up at the farm a few days later on, and asked for me.

THE driver was a husky, vigorous man with shrewd

gimlet eyes. His left hand was gloved and dead; it was an

artificial limb, but he could work its mechanical fingers

very cleverly. His name was Earl Carter, and he was an

attorney from the States. The man with him was a physician

whom he had brought out from Edmonton.

Well aware that the family would not approve his errand, Carter got me to go out for a ride with them. Once we were out of sight from the house he drew up alongside the road. The two of them pumped me, and I was ready enough to talk about my experience. Presently Carter looked at the doctor, who nodded.

"I'd chance it, yes."

"All right." Carter handed me a crisp hundred-dollar bill. "Bronson, this is yours if you'll get that gourd bottle, take a dose, and show us you can play dead. The doctor here will take care of you and bring you around. If you can do the trick I'll pay you a thousand more and all expenses. I want you to go home with me and pull off the stunt once again, under certain conditions. I'll need you for perhaps a month. It's good pay."

"What?" I exclaimed, in swift alarm. "Take a chance on killing myself for a hundred dollars?"

"Are you worth that much alive?" Carter asked grimly. "Think it over, young man."

He made no other argument, to his credit, and none was needed. The thought of the money overbalanced my fears; at the moment, we actually had no food in the house. I made him sign an agreement to take care of all funeral expenses if I really died, however.

Then we drove back home. I sneaked out the gourd bottle, and we went to town. In a hotel room I took a dose of the stuff—and went to sleep. First, the doctor had gone over me very carefully. He was taking no chances.

When I woke up again the hundred was mine. Carter admitted, too, that he had been frightened stiff by the result of the experiment. The doctor was more enthusiastic about it. I heard them talking.

"The eyes could be taken care of," the medico was saying. "The only thing he responds to is the mirror test, otherwise. That is, if you exclude a very critical examination."

Carter grunted. "Yeah? What would take care of the eyes, then?"

"Homatropine would dilate the pupils as in death, and a little cocaine with it would obviate any corneal reflex. Except for the breathing, he was to all appearance a dead man. He could stand no fluoroscopic examination, naturally; but he'd fool many medical practitioners, especially if no laboratory facilities were at hand. A most remarkable case!"

Carter knew now that I could do what he wanted. I knew that the stunt produced no very bad effects on me, so my terror was gone.

In a very general way only, Earl Carter told me what he desired. He gave me five hundred dollars advance pay, which I turned over to the family, and we started in his car for the States.

This drive marked the great turning point in my life.

Carter would not detail his plans, but whatever they might be, I could guess that they held nothing petty or unlawful. This man was no piker. He carried a spacious air. His vast energy, his driving power, were phenomenal, and extended in a dozen different directions. He could turn his hand, even his mechanical hand, to anything, and become a master. His air of entire assurance was no mere braggadocio. It held something overwhelming. We became real friends on that trip, and Carter talked to me like a father.

"With this damnable gift of yours, Bronson, you'll have to keep a tight check-rein on yourself. If you fell into the wrong hands, if you became a tool for unscrupulous crooks, you could make a raft of money; watch out! God knows I'm no angel, and I don't believe in much of anything, but this is something that frightens me."

"You should worry," I said with youthful cynicism.

He gave me a hard look. "You don't get it. Bronson, whatever powers there may be in heaven or hell keep an eye on such things. Of this I'm convinced. I can't explain it; you're a farmer, but you can't explain how a blade of corn comes up out of a seed kernel. Still, you know it does. There's a strange and terrible certainty in the law of compensation, young man. If you should turn yourself to illegal uses, look out! I don't know what would happen, but I'd hate to be in your shoes. You can make money, and make it straight. Remember that, always."

Over and over, the lawyer harped on this theme, and drove it heavily into me. He was a fine man, the squarest man I had ever known, even if he was full of legal tricks. Square in a man's sense of the word. Angular, hard, straight as a die—foursquare.

He admitted freely that he did not serve the law, but made it serve him, and at times ran pretty close to the wind. He handed out none of the old blarney about legal ethics, which is something designed merely to help rook the sucker: On that drive he gave me a liberal education in the cold, ugly, hard-rock racket of lawyers; and more, he showed me how definitely a man must live by his own code of ethics if he is to come out on top.

If Earl Carter is still alive and reads this story I want him to realize how deeply his words sank into me, and what fruit they bore. I owe that man a great deal.

Before reaching the city that was our destination, we had a week's drive. In this time I came to learn a lot about Carter's business. He was not a mouthpiece for crooks, as he had little or no criminal practice, and wanted none. He did specialize in helping people who were in a jam—and who could pay heavily for the help.

He drilled into me that the prime business of a lawyer is to get his client's money, and that plenty of big-time legal lights with wealthy clients simply made use of the law to serve the wishes of those clients. This was only a tiny corner of the racket, but Earl Carter had turned it into a mighty big corner, for himself. No matter how respected or innocent a person might be, the law could trap him and squeeze him—unless he happened to have an attorney who could outsmart the law.

"And I'm the outsmarter, you bet," Carter told me quite frankly. We drew pretty close together in those days. "I get the sucker off the hook, and he pays through the nose for it. Thirty per cent of all business in America is run on the principle that the fool and his money might as well be parted now. We've passed the age of simple honesty; it went out with mutton-chop whiskers. Only, I get his money by saving him from his folly."

"Where do I come in?" was my question.

He grinned at me. "You just obey orders. Right now, I've got a whopping big case on hand that should never come into court. That's why I took a long trip by myself; I need to cool off my brain and get ideas. When I found you, I got 'em. From the angle of legal ethics and such bunk, I ought to be shot for what I've got in mind. There's just one thing about it to remember. It's going to get an innocent person clear of a lousy mess. And if you ask me, that's pretty damned good ethics all by itself."

Before crossing the border, we stopped a couple of days in a small town. How Carter managed it, I can only surmise. When we left there, however, I had a legalized birth certificate in the name of Arthur Sullivan. As such, I came into the United States with him, and I continued to be Arthur Sullivan for some little time thereafter.

At a suburban station a few miles outside his home city, Carter let me out.

"Ride into town and go to the Grand Hotel," he said. "Get yourself some clothes and study the stock market; you're a broker from San Francisco and you never heard of me. Let your mustache grow. You'll hear from me in a week."

I obeyed orders. The Grand Hotel deserved its name; I spent money, but did not pad my swindle sheet. The mustache made a great change in my appearance, and I hung around board rooms and learned the jargon of the market, for I was anxious to make good at this job. Meantime, I heard a lot about the Petty case.

It was the biggest, juiciest and hottest scandal that had ever struck town, and when it came to trial promised to be still hotter.

Colonel Petty had died three years before, leaving a sister, a widow and a daughter. He was many times a millionaire, owning about a third of everything in the city, and his estate all went to his daughter, under the guardianship of his widow, who had plenty in her own right. And now the sister, who was one of these thin-lipped women, had chipped in to demand the guardianship, the money and the daughter, alleging that the widow was an improper person to have the child, and so forth. And they had the goods on her, too.

Around the hotel I had met a doctor named Slausson, who knew everybody in town, and I half suspected that Carter had steered him on me. We got pretty well acquainted.

"But what's the scrap about?" I asked Slausson, as we talked over the Petty case. "I understand this daughter is eighteen. Whoever wins would only get to handle the estate for three years or less. And can't she pick her own guardian?"

"Not in this state." Slausson grinned. "Minors are protected in this state, you bet! But you don't get the idea. Nobody gives a damn about the girl; it's the shakedown. This old maid sister, Tabitha Petty, has the biggest law firm in the West handling her charges. And those boys are slick. Mrs. Petty, the widow, is a frivolous, pleasant, harmless woman who likes a good time and spends her money. When they get her into court, they'll just tear her wide open, see? Misconduct, you bet, real or faked. Probably faked, if you ask me. It'll be red hot, too. She faces newspaper notoriety of the worst kind. She's sure to lose the girl, who adores her, and she'll be branded for life—unless she digs into her wad and settles things. Earl Carter won't let her get into court. He'll settle."

I remembered all Carter had said, and from what else I could gather, realized that Mrs. Petty was the sucker in the case. The trial was set over to September, which was three months away. The sucker was sure to lose. Tabitha and her law firm were utterly respectable, aristocratic, and practically saints; so upright they nearly fell over backward. Most lawyers, up against that firm, just hollered for help and paid up rather than risk themselves in court. But not Earl Carter.

"Like to meet Mrs. Petty?" Slausson said to me one afternoon. "She's giving a dinner dance tonight at the country club. We might run out there. I'd be glad to give you a guest card, too, for the length of your stay."

NATURALLY I assented, perceiving the hand of Earl

Carter at work. This became quite certain with evening.

Mrs. Petty not only was most gracious, but invited me to

luncheon two days later. Little as I knew of society,

this intimate invitation could only be explained in one

way—Carter.

Mrs. Petty was pretty and light and useless as a bubble, with not enough brains to be anything but the leader of town society; just the right target for such a lawsuit. Her daughter Patricia—ah, that was different! The girl was something wonderful. There was a flame in her. She volunteered to teach me golf, and in another three days we were running around together like old friends.

I did not flatter myself that she had any personal interest in Arthur Sullivan. It was a hard job not to lose my head, what with her companionship and being invited to the house all the time by her mother, mingling with their friends and so forth. I was pretty much of a farm hand, and had sense enough to realize it, fortunately.

All this time, I had received not a word from Earl Carter, and had not seen him. I sent in my expense account each week to his office and received an envelope of cash, even to pocket money, by messenger, in return.

Then, one morning, Slausson telephoned me to come over to his office. I went. His girl attendant sent me into his private office, and he gave me a grin.

"Strip, Sullivan," he said. "I want to give you the once-over."

"What for?" I demanded, in surprise.

He cocked his head on one side and eyed me.

"Yours not to reason why, feller. Yours but to do and die. Do you get me? No names mentioned, either. I want to check up on you, that's all."

I assented with a shrug. When he applied his stethoscope to my right side instead of to my left, I knew instantly that he was working for Earl Carter; not another soul knew my secret. Evidently he was checking me over to be sure there were no mistakes, and he was thorough about it. When he got through, he gave me a bottle of liquid and a dropper.

"Complete directions on the bottle," he said. "Whenever you feel like committing suicide, Sullivan, be sure and use this hematropine and cocaine first on your eyes. Follow the directions carefully; a drop every minute for five minutes—"

Still no word from Carter, no hint of what I was to do. The suspense began to get on my nerves. So did Patricia.

Why? Well, I must be honest about it; no one could be so intimately associated with that girl, and not react to it. We got on pretty well together. She was very frank and open, a good sport in all the term implies, and pretty as a picture. She had hair like red gold, and looked like Myrna Loy in the face; when she laughed, you could hear little silver bells tinkling in the air.

She was not in love with anyone, as I had discovered. We had not mentioned Carter, nor anything out of the way in our friendship.

I knew that she was devoted to her mother and hated her Aunt Tabitha like poison, as well she might, but we had never discussed the lawsuit, of course.

Then, without warning, everything broke at once. And what a break!

It was the middle of July, and hot weather. I did a round of golf with Patricia in the morning, and came back home for lunch with her and Mrs. Petty. There was one other guest; it was Earl Carter. I was introduced to him, quite formally, and then we had lunch served out in the sunken garden behind the huge house. It was cool there, beneath a big striped awning. Also, no one could overhear what was said.

When the things were cleared away and the servants dismissed, Pat and her mother went to look at the flowers, leaving me alone with Carter. He gave me a hard, straight look.

"Sullivan, this is Tuesday. On Friday afternoon, you ask Pat to marry you."

It hit me like a bombshell. I stared at him for a moment, then got angry.

"Are you joking? No, you're not. Well, I'll do no such thing—"

"Part of the job," he cut in, chewing on a cigar. "Come on, now; straight talk. You and I and Slausson know you're going to die. These women don't. They think you're going to marry Pat, then the marriage will be annulled. You know all about the legal mess, and you've got to do the one thing that can save Mrs. Petty from the whole dirty net these swine have caught 'em in. The marriage, of course, is to be in name only."

"Why not hire somebody else for that?" I said hotly. "And then have the marriage annulled?"

"Nope. Under the state law, the one thing that can clinch our business is for Pat to become a widow—quick. Otherwise, there'd be fraud charges and hell to pay. Pat comes into her money, is free of guardianship, this damned cat of a Tabitha is helpless and so are her lawyers. And there's no shakedown. Get it?"

I grunted in dismay. "But I'll be married, tied up all my life!"

Carter chuckled. "Sure, Arthur Sullivan will. He'll be dead and buried, with a fine monument in the cemetery. You won't. You'll be James Bronson, another man."

"Damn it, I don't like it," I said bluntly. "What about Pat? Wouldn't she actually be tied up to me for life, if the truth of it ever leaked out? Isn't a marriage under a pseudonym still a marriage?"

"How can it be if the husband's dead?" Carter snapped. He reddened a bit; my question had hit him in a tender place. "Never mind all that; I'm running this business, not you. Here they come. Remember, now—it's to be annulled! That's all they know."

We rose, as the ladies returned. Carter explained that he had put the whole thing before me and I had agreed. It would all be very simple. Mrs. Petty would be able to have the marriage annulled and there would be no trouble.

"Oh, it all seems so terrible!" Mrs. Petty's nerves were shaky. "What if anything went wrong?"

Carter gave me a grim look. "Nothing will go wrong. There's not a loophole."

"But there is." Patricia flashed me a quick smile. "If Arthur were crooked, things might go frightfully wrong; but he's not. Your opinion of him, Mr. Carter, is correct, and I know him pretty well. You will help us, Arthur?"

"I suppose so, yes," I said, hesitant. "Only—"

"Only, it's a business proposition," said Pat, with a nod. "Right."

"Well, I suppose I'll have to go through with it," her mother declared resignedly.

"You will," Carter assured her. "And when you're tempted to back out, just think how Aunt Tabitha is going to foam at the mouth! Now, you young folks, get things straight. You propose on Friday afternoon, Sullivan. Pat says yes. The two of you leave for a drive in Pat's car on Saturday morning. Drive on across the state line to Cedarville; you can get a license and be married there on Saturday afternoon, which you can't do in this state. Thus there can be no court interference until Monday, when it's too late. Cedarville is a big place. Take a suite at the Hotel Cedar and stay until Monday. Then drive on clear to St. Louis, and come back here the end of the week. All set?"

It was all set. Before leaving, however, Carter had a last word with me alone.

"Sullivan, you'll pull the death act on the following Monday, at a luncheon here. I'll have just the people I want, for guests, and I'll be here as well. That evening, I'll get you out of town. Go far and stay. Shave off your mustache or grow a beard, either one. I'll give you a ring here—you and Pat will come back to this house—on Sunday evening and make sure everything's jake."

So everything was shaped up, and once I was in for the business, I could admire the ingenuity of Carter's plan.

Just the same, I was frightfully awkward when with Patricia, during the next two days. A thousand problems bothered me.

I did not know what to say or do. At length she got right down to cases with me, while we were dancing at the country club Thursday evening.

"Arthur, for heavens' sake come back to earth and be sensible! Stop flushing every time you look at me. I'm the one who ought to be embarrassed and all in a stew."

"That's the trouble," I said. "You're not. And—and I think a lot of you."

Her face got cold. "You're not jumping the gun, are you?"

"No, confound it," I said. Just then someone cut in, and we did not refer to it again.

Friday afternoon, at the country club, we played around five holes and I could not get up to the point of proposing. Business or not, I evaded it. At the sixth hole, Pat told me to get a move on. I had gone into a bunker, and the caddies were watching.

"Just what we want, Art," she said briskly. "When they see us kiss, those boys will spread the news, and—"

"All right, damn it, will you marry me?" I blurted out desperately.

She laughed. "Yes! In spite of all the world, my hero!"

So I kissed her, and she kissed me; then she drew back, a little red.

"You don't need to show too much enthusiasm," she snapped. "Remember, this is business only. Come on, finish the match and pretend you don't see those caddies snickering."

So I did.

Next morning I met Pat downtown, climbed into her car, and we were off. She said her mother was pretty near hysterical over the affair, but would come out of it all right. Pat was nervous herself, and so was I. Even in a business proposition, people have feelings.

We got to Cedarville, crossed the state line, and at the courthouse got our marriage license. This part of it was all right. We hunted up a justice of the peace and that was all right, too, until he went to work on us. Then I began to feel uneasy. When he slammed his book and pronounced us man and wife, Pat was white and shaky and I was red as a beet.

"Well, get busy and kiss the bride!" cackled the justice.

I did it, and Pat clung to me for a moment. Her kiss was sweet, and it was like fire; it went through every vein of me.

"Two dollars," said the justice. "Business is business, folks."

"A good motto to remember," Pat said to me, and I nodded dumbly.

We went to the hotel and got a suite. Pat went up with the bags, to freshen up a bit, and I got rid of the car. She met me in the lobby, and we went out to a picture show, which is the best sedative for disordered nerves. It was going to be an awkward moment when we got back to the hotel for the night, and I think we both wanted to put it off as long as possible.

However, the movie put us into humor for joking over the marriage state, and we hunted up a good place where we could dine and dance.

"What about wine?" said Pat, after we had ordered. She gave me her bright and flashing smile; there was a sparkle in her eyes. "Don't you ever celebrate your weddings with champagne, Art?"

I thought of her kiss, that afternoon, and knew perfectly well that we were on dangerous ground; I certainly was, and I more than suspected she was. All right, be damned to caution, I thought with a burst of feeling. After all, this is my wife. We are legally married. Champagne, and a big one!

So we dined and danced. Pat loved to dance, and with her flushed cheeks and sparkling eyes, she looked divine. When I held her close to me and brushed my lips against her face, she looked up at me and laughed.

"There's something bewitching about it all, isn't there?" she breathed. "About being alone, in a perfectly strange city, and—and—"

"And being old married folks," I said. "Yes, there is. Did you write your mother?"

She nodded. "This afternoon. And I lied beautifully so she could show the letter. I said we were married, and how happy we were, and how fine you are—"

"Was it all a lie, Pat?"

Her eyes met mine, and her arm tightened about my shoulders.

"Maybe not all, Art," she murmured, just as the dance ended and the crowd streamed back to the tables.

IT was late when our taxi dropped us at the hotel. I

got the room key and we went up; and to be quite honest

about it, I had quite forgotten that motto the justice of

the peace had quoted to us. Pat was a glorious creature,

and I knew that she did like me, and she was my wife. That

was enough to make anyone forget anything else.

We had a suite of two rooms with a bath between. I unlocked one door and we went in, and switched on the lights. The room was empty.

"I had all the bags put in my room," said Pat, leading the way. "Come along and pick yours out. It's been a perfectly scrumptious time, Art; I've never enjoyed champagne so much in my life!"

And now it was ended. She did not say the words, but I could sense them—and I could sense the regret in them.

We went on through to her room. I picked up my bags, and then set them down again. A lump came into my throat when I looked at her, when I met her eyes.

"Pat!" I stammered. "Pat, dear—"

She dropped her cloak on the bed, rumpled up her short hair, and turned to me with a half smile.

"Yes? Not a compliment, surely?"

"You're the loveliest thing I've ever seen," I said awkwardly, and reached out and touched her. Her eyes were radiant, as she came to me.

"Just for that, my dear, you might kiss me good-night," she said.

I held her for a moment, until she pushed me away, but not completely.

"The proper thing, Art, for an old married couple to do, would be to smoke a good-night cigaret together," she said gaily. "Take your bags over, then—"

What I read in her eyes made my heart pound. I kissed her once more, quickly.

"Right," I said.

Picking up my bags, I carried them over into my own room. And when I got there, I stopped dead. Sitting in a chair, calmly regarding me, was a perfectly strange man in a chauffeur's whipcord uniform.

"Who are you?" I snapped. "What the devil are you doing in my room?"

"Jim Brady, of the Gallup Detective Agency, Mr. Sullivan. My job is to drive your car from here on, and to spend every night sleeping right with you."

For an instant I was speechless. Then I burst out hotly. He cut me short.

"Listen, Mister, it's no use talking. I'm here, and my partner's got the room across the hall with the transom open. We stick closer'n burrs until you folks get back home. And if you kick up any fuss, you get slugged and thrown into jail."

Pat, who had heard the voices, came in and stood staring. I was in a blether of rage. I thought Carter must have done this, but I was wrong. Brady was frank.

"Nope. I'm hired by Mrs. Petty, see? Now, folks, I'm mighty sorry to stop the fun, but that's my orders. You got to decide whether you want to raise hell or take it easy. I'll accommodate you either way."

I looked at Pat, and she had gone dead cold.

"Nothing to be said about it, I suppose," she observed. "It would knock everything in the head, Art, if we tried to fight—"

That was true, and I settled into a miserable resignation, and cursed Mrs. Petty with all my heart. We were married, yes, but we were up against two thugs—and publicity would upset the applecart.

And, believe it or not, that man Brady was with me closer than a burr, as he had put it, until we got back home the end of the week.

By that time, the budding dream was gone. My relations with Pat had settled down to a cool business basis. When we were ensconced in her own gorgeous home, I put in a devilish two days—congratulations on all sides, happiness to the newlyweds, gifts and so forth. And it was all a lie, had people but known it.

I gathered that Aunt Tabitha was gritting her teeth and preparing for action.

On Sunday night Carter telephoned me on the last details. Monday noon came, and with it a formal luncheon. The old family doctor was there, among others. I complained of feeling ill, left the party long enough to put the hematropine in my eyes and take a dose of the liquid from the gourd bottle, and rejoined the company. I did not care particularly whether I stayed dead or not. The whole business had rather sickened me; I had not yet become used to such things.

At the luncheon table, I went to sleep. The old family doctor took one look at my eye, felt my pulse, tried for my heart—and the fat was in the fire. Doctor Slausson was hurriedly summoned, but no use. I was dead and no mistake.

Nor did I make a pretty corpse, with my pallor, bluish lips and so forth. Carter told me as much that night, after he had revived me and taken me out of town in his car.

"You looked like the devil," he said. "Good thing I was warned about the mirror test! Watch out for it in future, if you spring this stunt, again. Luckily, Slausson took care of it; held a mirror to your lips and pronounced it blank."

He handed me my money and turned me loose with his blessing.

"Feel all right? Good. Clear out, and don't you ever came back to this town!"

"But how'll you manage the funeral?"

I demanded curiously.

"Never mind. That's all fixed, and no last views of the corpse either." He grinned at me and started up his engine. "Arthur Sullivan is dead, understand?"

It really is a beautiful tomb. I went through the city last year and stopped over just to see it. A lovely shaft of granite raised to the memory of Arthur Sullivan. And I found it had been erected by Pat's "second husband."

I've often wondered what sort of a yarn she told him about her first honeymoon!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.