RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

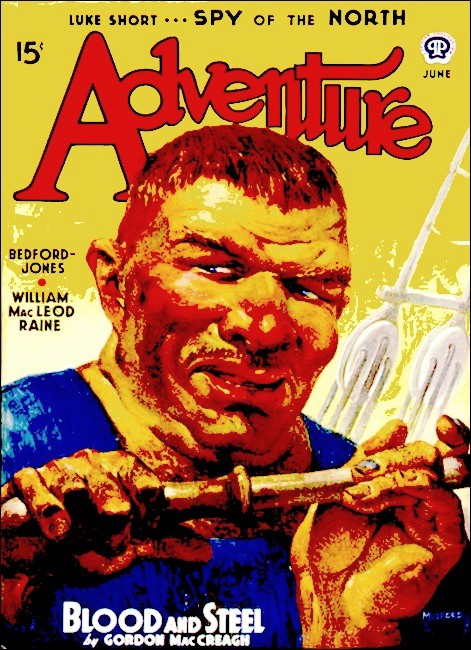

Adventure, June 1940, with "Blood and Steel"

KING, trader, white hunter, and thorn in the side of many foolish people, pushed his tawny head up over the steep lip of the donga and paused with instinctive and quite unconscious caution to let his narrowed eyes first take a survey of every thing that moved on the plain.

"Anything—" It was an unshakable slogan of his—"can happen in Africa." And Kingi Bwana of the wide experience was just now being careful.

The thing that was happening a scant mile away was a startling verification of even so all embracing a slogan. What moved on the plain, a black dot in the distance still, was the most vicious live thing in Africa, and its quarry was a white man.

King heaved the rest of his sinewy length over the donga's edge and stood up, the better to see, while he sibilated the bitter Swahili proverb with his sharply drawn breath.

"The broken spear is needed a hundred times daily."

That was why King had been traveling along the bottom of the donga instead of wide open and don't-give-a-damn on the plain—because his weapon, his rifle, was broken.

He was climbing out of the donga because its precipitous sides were pinching in on him and he could see, only a hundred yards ahead, where a cascade of shale rubble marked the sudden narrow beginning of the erosion gully.

King turned his head for a moment from the desperate race that thudded over the plain to call down the donga's depth: "Up, there! Quick and look!"

A Masai ostrich plume bobbed up; brawny limbs sprawled over the edge. The man reached a hand down and with a single long swing slung out of the depths a wizened little Hottentot who landed with simian agility on his feet and immediately hopped high again in excitement and shrilled a call, for all the world like a grass monkey.

The Masai stood to his height and looked. He exclaimed, "Whau!" Immediately then his iron calm asserted itself and he viewed the racing drama of life and death with impartial criticism.

"Kifaru pursues furiously, for, see his tail, he is much enraged; and I think indeed he will catch that motor car, for the driver is inexpert over this grass land."

King pulled his pith helmet low over his eyes to cut the upper glare and frowned narrowly at the advancing spectacle. For the moment the car was holding its own; a none too new model, it clangored and roared its laboring best. Behind it pounded the rhinoceros, nearly as big and quite as heavy and virulently more destructive than a car at its worst, snorting and blowing almost as loud.

AT that, steel and machinery ought to have outrun flesh and bone; only that

the driver was woefully inexperienced over that kind of terrain. The car

lurched over high tussocks of the stiff bunch grass, swayed drunkenly into

the in-between depressions, jarred into clumps that visibly checked it before

it could roar again to its pick-up. The thundering brute behind, born to that

ground, was gaining.

"Tch-sha-a-ah!" King exhaled his impotent aggravation. Hard-boiled he was and attuned to African grimness, but his white man sensibilities had never learned to equal the Masai's African impersonality. "Why can't he pick the soft spots? Crack an axle or dish a wheel—any least thing happen, he'll be mush. That brute will knock his machine apart like a bomb and trample him out all sticky."

His hands with automatic habit inched up to the ready position for snapping gun to shoulder. Then he swore helplessly and let them drop. "And not a gun within a hundred miles!"

The driver saw the three human figures outlined against the farther heat haze. Humans, therefore human aid! The impulse was instinctive. He wrenched desperately at his wheel and headed directly for them.

And King—perhaps the man in all Africa most sure of stopping a charging rhino—weaponless! That was the grim humor of Africa.

"Wo-we!" The big Masai spat calmly. "The fool's fate reaches its appointed end. He will never see this donga in time and will plunge to the depth."

"Having first lured destruction upon all of us." The Hottentot danced and chattered abuse. "From a fool can his foolishness not be beaten with sticks." The proverb was amazingly like one recorded into Holy Writ by a man much wiser than he.

King jumped high, waved his arms and pointed wide sweeping gestures over to his right, beyond where the donga began its abrupt course.

The driver, fool though they all named him, retained sense enough in his extremity to understand the obvious signal. He wrenched his wheel over again and the car shuddered on in its altered career.

"Yet Kifaru will surely catch him," the Masai said, as callously as a white man watching greyhounds course a hare. The course paralleled them now—the car careened some two hundred yards away; the remorseless rhino pounded seventy yards behind.

"He avoids the new danger," said the Masai, "only to be overtaken by the old."

Much of the grief that came to King in Africa was because he was just not hard-boiled enough to stay out of trouble that was not strictly his own.

"Not so," he said quickly to the Masai. "For you can still divert Kifaru and haply snatch that man's life from his fate."

"Wah, Bwana!" The Masai's exclamation was one that could indicate surprise, or with almost the same intonation, indignation. His long oblique eyes judged distances as critically as they counted the chances of the grim race. "It might indeed be done, Bwana. But the life of a fool, is it worthy of the risk?"

It was quite impossible to drag eyes away from that race. King grated words only out of the corner of his mouth to his henchman.

"It is not an order, for death rides close on that play. Yet I would count it a favor."

"Veme!" The Masai shrugged further argument from his great shoulders. "Death and I have played many times together. I go."

"To this side of the donga," King called after him. "That the car may escape beyond."

THE Masai ran with the swallow-like gliding motion of long limbed men whose

legs are well muscled under their weight; his black ostrich plumes flattened

back in the wind, the colobus monkey tail garters at his elbows and knees

flickering like whips; his spear extended, he shouted as he ran the hoarse

"Ss-sghee" of the Masai charge. A superb figure of savage daring.

"Ow-woo!" the Hottentot moaned. "All for a man who is a fool."

King knew to exactness what the Masai dared. He stood on wide-spread legs, his thumbs in his belt, twisting till the stout leather creaked.

The Masai raced on a diagonal slant to get between car and pursuing beast. The grass was as high as his knees, yet his feet seemed to skim the flattened tops.

"Ha!" It crackled from King. "He's cut the brute off!" An astounding term to apply to two hundred pounds of man opposed to two tons of furious beast. Yet there was the Masai leaping high and yelling full and fair in its path.

The death that he so familiarly scouted rode now on the chances of how soon the short-sighted brute might see him.

"The wind at least blows from him to it," the Hottentot moaned.

And it was scent, probably, rather than sight that checked the beast's charge. It lurched suddenly to a stop. Its lowered head, long aimed at the car, flung up; its hair-fringed ears twitched; its little red-brown eyes peered to follow its nose. The horn of it stood up against the sky like a dark yard of threatening sword.

The Masai flung arms and legs wide to the air and leaped before it, yelling. A bare thirty paces before it, but enough.

"Ha!" It came dry and harsh from King again. "He's done it! Good man! Get ready, Apeling, to scramble down faster than ever you came up."

The rhino's insensate rage was immediately diverted to this new annoyance that pranced before it. It snorted a staccato succession of small explosions, down-horned again and lumbered forward to obliterate the annoyance.

A cool man with steel nerves, armed with a rifle, could then have fired over the tip of the horn into the brute's brain. A desperate man with steel spring sinews, armed with only a spear and having no other recourse, might possibly have dodged aside and driven his blade into the comparatively soft skin under the beast's foreleg. A skilled and very powerful spearman might—just barely possibly—have so killed it. The thing had been done in Africa.

The Masai, haply, was not that desperate. The donga was his better recourse. He yelled once again and turned and sped back, winging over the grass tops like a dark swooping bird, the darker mass of snorting hate behind him.

"Ha!" said King. "He's safe!" He was all unconscious of the enormity of applying the term to the appalling circumstance. "Down you go, little ape, and up the other side fast, lest the beast sees the donga no better than the car and crashes down on us."

The Hottentot was already scuttling down. King swung his legs over, felt for toe holds, found root grips, reached the bottom with an avalanche of red clay dirt. He sprang across and was nearly to the top on the other side when he heard the hard pad-pad of the Masai's feet. Then he saw him.

Like a great dark bird again. Arms wide, garter fringes flapping, legs drawn high to his belly, sailing over. All of an eighteen foot leap. Nothing for an athlete taking off from a hard packed surface with a white line to mark the spot; but from the uneven lip of a ravine a very nice little job of jumping.

Then he saw the rhino, appallingly close and monstrous, looming black like a locomotive. Saw it suddenly stiffen its squat forelegs; saw the horny great pads of its feet plow twin deep furrows in the soil that immediately hid it in red dust as thick as the swirling haze of his own hurried passage across the donga.

He listened, rather than looked, for the shuddering impact of four thousand pounds on the donga's bottom. The moment passed. No impact came. Then he looked to see that his Hottentot was safe.

Safe enough and vociferous. The little man danced on the ravine lip in vituperative derision, waiting only for the dust to float clear enough for his triumph of safety. He prepared himself by tearing clods of earthy sod from the ground and chattering curses that there were no stones.

The dust thinned. The great brute looked at the chasm before it and blew vast breaths of steam. It tossed its head in perplexity, suddenly very much like a horse in its reactions.

The Hottentot spat on a clod of turf.

"This, Black One, is my blessing," he shouted and flung it to powder off the beast's armor plated side.

The beast muttered explosively and kicked forward with its great toes.

"This, O offal of cave spirits," the Hottentot yelled again, "is the blessing of my father and of all his forty-three children."

The clod shattered over the beast's face. It drove its great horn deep into the ground and plowed barrow loads of turf at a time; it stamped upon them, squealing.

The Hottentot, spat upon each succeeding clod in the copied Masai custom of imparting blessing. "This, pig with a diseased nose, is the well wishing of my whole tribe."

The Masai stood in immense dignity. He said. "Look, Bwana. It is no wonder that the beast is enraged."

King looked at it with a thin frown. "Poor devil."

From its left shoulder protruded the broken haft of a spear, fixed there because the blade must have turned on itself like an iron claw.

"The man," said the Masai impassively, "was a brave one and the stroke almost in the exact spot; though were it I, I would have aimed a shade forward. A pity that the steel was not worthy of the man."

King shook his head. "A pity it is that so much shoddy material gets traded around to naked men who have a man's courage but the sense of children. That man's village will be one for the trader to keep away from, if he wants to keep on living."

And then at last he had time to remember the Masai's superb stunt.

"It was well done, Barounggo. A man's deed. It will be remembered. That man's life you surely saved to be counted against the many you have taken."

"Whau, Bwana!" The Masai's viewpoint was extraordinarily practical. "It remains yet to be seen whether the saving was worth the man."

ABOVE the snorting and raging of the rhinoceros before them came the snorting

and clanking of the car from behind. All three men turned appraising eyes

upon the occupant, whom they knew so far only as a man lamentably unfamiliar

with that country.

"At least," the Masai said, "his limbs are not stiffened with fear of the death that followed."

The car clattered to a stand. The man in it leaned out to show a square face young and ruddy with the frost chapping of England's winter. Whether he grinned out of one side of his mouth or whether the distortion was caused by a monocle that lifted that half of his face was not clear. He said:

"The brute's pretty demmed shirty, what?"

King looked him over with a face as expressionless as though it was hewn out of hard-grained wood. He was never one to expand to a meaningless smile upon the mere approach of another white man, and anger he never let an enemy see. He said:

"Shirty, as you say, and then some."

"Come jolly near to getting me, too." The young man shivered a little.

"And still might," King said. "Come along—keep moving down donga. It'll be twenty miles before it'll flatten out enough for any rhino to get across, and with any luck it'll be too dumb to go around the upper end. Keep slinging mud at Kifaru, Kaffa, and lure him along a ways."

"By Jove!" The young man showed alarm. "D'you really think, old man, it might get it into its head to come round?"

"It could. Anything can happen if the gods of Africa decide they don't want somebody on their landscape. Keep moving."

The car lurched along. On the other side of the donga, so close that you could see the hate in its little pig eyes, the rhino paralleled it, kicking huge divots of sod at intervals, slashing its horn through the earth with a grunt and a vast heave.

The destructive potentiality of the thing was appalling.

"By Jove!" The man showed anxiety. "What that would do to a car!"

"Don't worry," King reassured him. "If it decided to come around the short end we'd just climb down and up the other side again. But you'd sure see a nice fast job of car wrecking."

The man positively shuddered alarm. "But that's just it. I dashed well can't afford to have him wreck my car."

"Oh," said King. "The car?" King's face indicated that whatever the fellow's other shortcomings, he was not to be condemned for cold feet. "Well, keep it moving," he said. "We'll be edging away in a while and let the brute forget us."

The maneuver was simple enough. Lured along beyond all chance of remembering that the car of its original hate must have found a way available to itself, the brute still tossed dust in the distance and nursed an abiding rage that forgot all immediate cause but remained ready to destroy immediately anything else that it might see.

"By the way," the young man shouted, "my name's Ponsonby."

King flicked a hand in acknowledgment.

"King," he shouted back.

The name meant nothing to Ponsonby. The fact was an indication that he knew nothing at all about British East Africa. Out of which the mystery remained—what in the name of all that was harebrained was he doing there alone in his ignorance? King stalked on; he was not interested enough in any Ponsonby to ask.

Ponsonby broke another clanking silence. "I say, old man. That was awf'ly sporting, what?"

"What?" King shouted back.

"I mean this big Johnny of yours with the spear. Most sporting thing a fellow ever saw—I kept looking back, you know. I've an idea the fellow saved my life."

"He did." King smiled briefly. "The two of them behind us are debating now whether the saving was worth while."

"Oh, I say! Come now!" Ponsonby's wide eyes let go of his monocle. It was only after a long rattling period that he was able to shout, "Rum beggars, these Africans."

KING stalked on, uncompromising, his eyes searching the uneven plain for a

place to camp. He picked the most uncomfortable spot in a radius of three

miles, a low kloof, a rocky outcrop of tumbled great boulders. "Where

rhino's don't come charging along," was his laconic explanation. But he

added, "Your car, not moving, will be safe.

"Dry camp and tight belts," he said casually. "Unless, that is, you're heeled."

"You mean, tucker, old man? Why certainly. I'm er—equipped, if that's what you mean. But—" Ponsonby had a more urgent matter on his mind—"this chappie of yours. I'm obliged to him no end. I don't suppose I could offer to pay him, could I? What I mean, looks like a sort of a gentleman, if you know what I mean."

King's appraisal of Ponsonby's shortcomings allowed his lips to crack to a visible grin. "I give you credit for perception," he said, but Ponsonby didn't know what he meant. "But you might say 'thank you'. And they're practical folks. Africans; a small gift would show you meant it."

"Certainly. Least I could do." Ponsonby ran to his car and came back with a shiny new panga, a machete sort of knife that East Africans use for just about every purpose from whittling toothpicks to building a house.

Barounggo accepted it gravely.

"Tell the white man it is a great gift for a small service," he said formally, but while he said it he was holding it suspended below the wooden grip. He applied his thumb nail to the edge and snapped away to test its ring. The blade gave out a dull pung instead of the clear, vibrating ping-g-g, that is prized. "But tell him," the Masai said with uncompromising African practicality, "that the steel is worthless."

King spared Ponsonby a literal translation of that. But he credited him with the appreciative thought behind the gift. He was interested enough at last in Ponsonby to ask:

"How come you tangled with that rhino?"

"How did I—" Ponsonby was all injured innocence. "I wasn't doing a thing. 'Pon my word, I was just chugging peacefully along when suddenly the thing exploded out of the ground like a bally mine and came for me."

King nodded understanding.

"Yes, they look just like ant hills when they're lying down; takes an experienced eye to spot 'em. And they'll charge anything that moves when they're mad, and this one's carrying plenty of mad cause with him. I'd just about bet it was the same one that winded my camp last night and hit it like a hurricane. Among most everything else it stepped on my rifle." King's wide mouth twisted. "Which is why you see me as helpless as a toad."

"But if you need a rifle, I've got one in my car!"

"You got a—" King's whole expression altered, lifted out of its dour dissatisfaction to the hope of a straitened swimmer who sees the straw.

"Why, certainly, old fellow." Ponsonby's generous impulses seemed to be without limit. "If you can use a rifle—Wait a sec. I'll go get it."

Ponsonby returned from his car, beaming. He handed King a shiny new weapon, the oil of its first packing not wiped from it. "If you know how to use it, it's yours."

"Aa-ah!" King reached for it like a missionary for his bible. He turned it over in his hands and drew the bolt. He end-for-ended it and squinted through the barrel and—"Yes," he said. "It is a rifle. But—" His white man inhibitions deterred him from putting into words the Masai's outspoken comment about the panga knife. He turned the sentence. "But, having even this, when the rhino came for you, why the hell didn't you haul off and stop it? The thing's one of your heavy British five-o-seven's. You could at least have discouraged the brute."

"You mean—" Ponsonby stared at him, "You mean I should have stopped my car and—" the thought was too bizarre for words.

KING laid the gun down. And Africa picked that moment for another display of

humor. The sun dipped to throw long spiky shadows of the rocky outcrops that

broke the plain; and, as it might have been some intercepted ray device that

actuated machinery, a rumbling grumble reverberated in the air. It had a

peculiar quality of not loudness so much as an all pervading volume that

drummed in the ears. As it swelled, other rumbles took tip the signal from

other rocky kloofs till the whole atmosphere vibrated to grumbling

summer thunder out of which boomed the punctuations of coughing belly

roars.

King was watching Ponsonby from under his lowered hat brim. He had watched all kinds of reactions to the first hearing of that African choir in an open auditorium. Ponsonby was watching King, absurdly quizzical with the monocular distortion of half his face. He said only.

"What do we do now?"

"What would you have done if you'd been in your car alone?"

"I'd have turned up the windows and sat tight." Ponsonby repeated it as a lesson. "They told me that lions didn't know enough to break in."

"There's a Hottentot proverb," said King. "The gods give either guts or sense."

"Meaning what?" Ponsonby was not attuned to native turns of thought.

"Meaning Englishmen." But King's interest in Ponsonby was now sufficient to ask: "Will you tell me what you're doing in this far end of nowhere without a keeper?"

Ponsonby was not offended. His indignation was directed, rather, at another cause. "Damn it, I tried to. I wanted to get a white hunter to guide me out, but d'you know what those brigands charge?"

King nodded. "A hundred pounds a month and expenses."

"Why, it's sheer banditry!"

King was not offended either. "Um-hm. But a white hunter often enough brings his babe out of the woods alive, and that's a chore that I know the worth of as well as anybody."

"You mean you're a white hunter?" Ponsonby was all eager excitement.

"Um-hm. There's been times when I've taken folks out—and brought 'em back."

"Why, then you could guide me to—" Ponsonby's eagerness chilled away to a blankness that dropped his monocle again.

"I say, old chap! No offense, you know. I mean, about fees and all that."

"No, no offense," said King. "I'm not hiring out anyway. I'm on my way into Entoto, nearest point where I can buy me a decent gun and be a man again, and nothing is stopping me. Only I'm more amazed about you than anything that's happened in a long while. It's none of my business, except that it's my business to understand the why of things in Africa. So will you tell me why? You're not hunting; you're not photographing. Is it maybe that you—but no; you're not writing. Will you tell me then why you want to be guided by the hand through the back reaches of Africa?"

Ponsonby's candor was quite un-British and engaging, but his explanation still made no better sense than any of the rest of him. "Well, you see, I was about to be dismissed from my job; so, since the emoluments were considerable, I had to put the old bean to work to find out why, and here I am."

"Just as simple as that." King remained patient. "You were going to get fired, judging by your complexion, out of a good job in England, so you came to Africa and got lost."

Ponsonby drew in a long breath of patience. "It's really all quite simple. I was—I still am, I suppose—export manager for a firm of steel manufacturers and our business has been falling off no end."

"So you came to the middle of Africa?"

"Yes, of course. To find out why these dashed trader blighters wouldn't carry our line of produce."

A wary, alert look like a leopard's came into King's eyes, but he grinned at the discomfiture he was about to produce.

"There's times, in between of guiding greenhorns, that I've been called all kinds of a Yankee trader myself."

"You are?" Ponsonby's eager enthusiasm suffused him again. "Why, then you're the very man I want to meet. You can—" Surging realization loosened his monocle again to drop with his jaw. "I say, old man! Seems I put my foot into it every time."

King still grinned. "I'm not even trading. I'm on my way shortest cut to Entoto."

THE Hottentot came and arranged sticks for the beginning of a fire. A short distance off the Masai was hacking at dry thorn scrub with the new panga and pausing at every few strokes to see whether its edge held. King gave the Hottentot camp instructions.

"A couple of fires will be enough for tonight. If Simba should come, I suppose this thing—" He pointed distastefully at the new rifle—"will suffice for close range." He added an explanation to Ponsonby. "No need for a thorn boma tonight, though this kind of rock outcrop country is a wasps' nest of 'em. But zebra and wildebeeste are plentiful and lions prefer them to us. Anything comes around tonight will be sheer damn cat curiosity, unless there's one of 'em mad about something."

"My word!" Ponsonby stared at him. "You fellows take them pretty casual."

King laughed at the incongruity. "Listen who's talking. You sell trade hardware, so you came out with a car, just like you'd take a turn of your midland towns in little old Blighty, to look over your territory in Africa?"

"Dash it all, man, I had to find out. The job's too good to lose."

"Whom d'you sell for?"

"Braun and Wendel. And all my samples and literature are in my car. So don't you see—" Ponsonby broke off at the sudden change in King's face. His jaw sagged as though the name had in some manner offered offense.

King's grin was taking its long time in contracting out of his lips, as a man who has been shot vitally may die with a death grin on his face. But King's eyes had already gone hard and had stared through Ponsonby and out into vistas that lay beyond the horizon of view. Ponsonby felt for his monocle, polished it without ever removing his transfixed gaze from King's, tried mechanically to twist it into his eye, from which, unsupported, it fell. He kept repeating the process while King still stared through him.

King's voice came at last; there was accusation in it.

"D'you know anything about steel?"

"Er, no," Ponsonby said. His voice had lost its buoyant enthusiasm. "No, I'm not a technician, just on the sales promotion end."

King grunted. "Well, then, let me tell you something about steel. I'm no technician either; I'm just a trader. But I'll tell you this—"

King, squatting there on a low rock, earth-stained, a little ragged, with the African dusk falling about him, loomed like some earnest exponent of a great religion delivering a world truth.

"Steel means life!"

The dictum delivered, he brooded over it, scowling into the gloom. Kaffa the Hottentot came and lit the camp-fire. Immediately the outer dusk that had merged tawny forms invisible into their background of tumbled boulders was punctuated by the reflections of great twin orbs that blinked and went out and opened to stare glassy green again. Kaffa shouted and threw burning sticks. The eyes blinked away and were silently gone.

King brooded on.

"In Africa, a man lives or dies by the quality of his steel."

King squatted silhouetted against the last copper glow of the dusk. Ponsonby sensed, rather than saw, that his eyes were now boring into his own.

"That panga knife that you gave Barounggo. It was one of your samples?"

Ponsonby felt a certain guilt in admitting it.

King relapsed into his brooding, dark and pregnant of the things beyond Ponsonby's understanding. "Maybe," King rumbled, "I am just the man you need to meet. Maybe the gods of Africa have been manipulating the strings of fate." Suddenly he fired a lean, strong finger at Ponsonby like a gun. "Piet Vreeden carried your line, didn't he?"

Ponsonby had already been uneasy about a something not entirely satisfactory about Piet Vreeden. "Yes, he used to be one of my steadiest customers. They told me, as I came through, that he had been ripped up by a leopard."

"That was the report that came through to the district officials," King said grimly. "But I'll tell you this: Piet Vreeden was ripped open and his bowels festooned along a village fence by three men of the Mathehebu wa Chui, the leopard society!"

"Good Lord!" Ponsonby's stout British subservience to constituted law was outraged. "Didn't you inform the police?"'

"No." King said it with staggering simplicity. "Because two of those men had lost a brother and one a son who died because the steel spear blades that Vreeden had traded them failed them when their need came."

"Good Lord!"

KING twisted on his rock to point into the sky glow that smoldered its last

dull anger. "Right there. Right back in that country from where I was coming

and you were heading when we met." He relapsed to his rumination again; out

of which came the growling conviction growling: "Yeah. Maybe I'm the white

hunter you need to guide you by the hand and show you things that a lot of

smug money-makers in England ought to know."

His voice was hard and practical. "I was headed for Entoto and I bragged that nothing would stop me. But I don't buck the gods of Africa. If they sent you I'll take you. To your own territory, that you wanted to look over and learn why." He called to the dark shapes of his two henchmen who huddled over the very smoke of their fire as only Africans can. "Tomorrow we trek back and go into the country of the Watanga tribes."

"Ow, Bwana!" The querulous complaint came from Kaffa the Hottentot. "An evil people and hostile to white man. Moreover it is a country unknown to us and the report was that trade amongst them was difficult."

King grinned at Ponsonby. "Difficult. But I'll take you in and show you your territory, by golly. Even with no better a gun than this one to make a man of me."

Ponsonby fidgeted on his rock seat, Britishly abashed over the necessary intrusion of finance. "Awf'ly good of you and all that. But, er—I'm afraid I can't quite afford to pay that frightful white hunter fee, you know."

"You aren't hiring me." King's voice was as hot as the glow in his eyes. "This is a call, a mission put on me by the gods of Africa."

It was only his laugh, a little ribald, that saved him from melodrama. "Anyway, I was figuring to edge in on that Wa-tanga country some day and get acquainted, maybe scoop some of the business that Vreeden lost. I got a wagon load of trade at my friend Chief Muthengi's boma, waiting only till the Wa-tanga might have forgotten some of their lousy deal."

A sudden thought came to cloud King's decisions. He fired his finger at Ponsonby again. "If, that is to say, you've got the guts to go through a piece of territory spoiled by your man."

Ponsonby's monocle dropped while he stared. He said querulously: "Well, dash it all, I came to find out, didn't I?"

King's appraisal of Ponsonby showed itself in a sour scrutiny that slowly broke into a grin.

"The rest of the Hottentot proverb," he said, "is that sense, if the little gods have withheld it, can be added to guts by the great god of Experience. I'll maybe even bring you out of the woods alive. Which, if I do, you'll be useful."

"I rather think, old chap," Ponsonby said, "you're trying to spoof me. You don't look at all nervous about it yourself."

King's sardonic grin slowly hardened.

"In Africa—" He told Ponsonby the priceless rule—"a back country trader keeps alive by not letting the native know that he's nervous. Only he's got to be careful. A white man, armed, can get through a lot of Africa these days, if he doesn't let himself get caught napping, like Vreeden. He relied on his native woman to tip him off to anything cooking up against him; his trouble was she happened to be related to one of the men who died. No, sir—there's a lot of people in this land have said I'm no good, but they'll all admit I'm damned careful."

THE wagon lurched in vast drunken progress over the uneven plain;

square-hooded like a truck, its wheels as high as a man's shoulder, they

heaved slowly up over grass tussocks and ant bear mounds that the most

skilled guiding could not avoid, and they came down on the other side with a

crash that wrenched at every joint. It took eight span of cattle to haul the

ponderous thing—sixteen oxen and two black boys who cracked twenty-foot

whips about their ears and yelled with vast African exuberance.

There was never any secret about a trade wagon coming into a country. This one's progress served hardy notice that King came not as an official, not as a missionary, nor as a hunter, but out and out as a trader and nothing else.

It was a country of umbrella-topped acacias and great brown termite hills that looked like clustered roofs of huts.

"Poor agricultural country," King commented.

Ponsonby trudged beside him, interested but not impressed.

King expounded, "If you're interested in ethnology—which a trader should be and Piet Vreeden was not—this crowd hasn't evolved to an agricultural civilization; they're cattle raisers, therefore nomads who follow the grass, therefore a tougher crowd than the farmers we left in Muthengi's country."

"Do you mean, difficult to trade with?"

"To get along with."

"Why?"

"For one reason, they've got little to lose in a fight. Their property is on the hoof: they can run it into the brush. For another thing, being loose on the hoof, they've got to be ready to defend it against man or beast, and where there's fat cattle there's fatter lions and leopards and things. Hell, it's history. Masai, Gauchos, cow punchers, they've all got to be fighting men."

Ponsonby digested that over a plodding half mile. Then, "Would you tell me, old chap, why you're doing this?"

King laughed harshly. "Because I'm a trader. Because I want to crash this territory before some one else gets ahead of me."

Then Ponsonby said. "I rather fancy, old man, you're spoofing me again."

"Yeah?"

"Yes, I have an idea, don't you know, that you're a sort of a Quixote chappie who believes that good fighting men, whatever their color, ought to have good weapons to fight with."

"Boloney!" King said.

Ponsonby laughed at him.

"You gave me credit once for perception," he said.

The wagon creaked and crashed for three days through that country before the brown ant hills in the distance turned out at last to be a village.

"We'll have to trade for meat," King said. "Where cattle eat off the grazing there's been no game. Watch now; you'll learn something."

The village was a filth-littered alley between flimsy huts of bare poles that could be left without loss when the middens became too pestilential for even African nostrils and the populace moved away to better pastures.

King stopped before the fence that surrounded the largest hut. He refrained from the white man blunder of barging in. Through the interlaced branches of the fence could be seen women and goats and lounging men. None came forward with the big toothed grin and the "Jambo, Bwana," of greeting that had met them at Muthengi's boma. King nodded to Barounggo.

The Masai planted the steel spike of his spear butt in the ground between the gate poles; the slender, three-foot blade of it quivered its tempered steel in the sun. As a Masai he knew how to speak to lesser peoples, as he knew that they knew a Masai's worth.

"Out!" he shouted. "Out, little head man and be humble when the Bwana, master of an Elmoran, waits."

There was some scuffling and much muttering within the hut and through its interstices it could be seen that a man was dressing himself; that is to say, he was draping a sheet, rendered impervious to rain by boiling in rancid butter, about his shoulders. Respectfully dressed but sullen, he came to his gateway and stood on one leg, the heel of the other cupped in the hollow of his knee, leaning against a spear for balance.

"Jambo, Masai," he said. He kept his eyes averted from the necessity of greeting the white men.

"We require," Barounggo ordered him, "six fat goats, or a young calf. We give one spear in exchange."

Other men came to balance themselves at their gates; tall naked fellows, they said nothing but looked on in lowering silence, while the head man was telling the Masai with bare-faced effrontery, "We have no fat goats."

"A spear head," King told Ponsonby, "is damned good payment for half a dozen goats."

"Lie not!" The Masai growled at the head man. "Do I not see a good fat goat there?"

An obvious lie in Africa is only a form of expression. The man laughed insolently. "Let me then see your good spear head."

THE Masai folded his great arms. Bargaining was no thing for an Elmoran. It

was the little Hottentot, keen as an ape to prove his wits in a trade, who

hopped forward with a blade.

The head man fingered it, turned it around in his hands. Others of the men unhinged their legs and came forward. A spear trade was as important as a deal in a new automobile.

King nudged Ponsonby. "Look at the big buck with the scars."

The man he indicated was gashed with four parallel scars that spanned forehead, cheek, and chin from nose to ear.

"Leopard society mark. Tell you about it later. Watch the trade now for your soul's good. I don't like the looks of this set-up."

The men handled the blade, smelled at it, whittled a stick with it. Their faces remained dubious.

"There's a slogan you birds have," King told Ponsonby grimly: "British steel. There's places around the world where its a proud slogan. This is not one of them. And the hell of it is there's more places than this in Africa where it isn't, like some of your sleek business barons will be learning some day."

Ponsonby said nothing. But his face was flushed.

"Look at 'em," King told him. "Look at 'em well. There's one sample of why your gang's business is falling off. These dumb oxen can't read brand marks stamped into the article; they won't know whether a spear blade is any good till they've had to use it—and then it's maybe too late for anything but collecting the blood price off the trader. There's times the price can be settled with gifts to the family; but blood debts can stack up till there's no price but blood. These surly fellows haven't forgotten your Vreeden—All right, Kaffa, take the five goats that they offer and let's get going."

The wagon creaked and crashed on its way. There were no shouts of, "Kua heri", or "Ya-kuonana," meaning "May we meet again;" no women jostling to wheedle a safety pin or a key ring to hang into their ear lobes.

"An insolent village." The Masai growled as he stalked.

"An ill village to trade and hostile, as I warned Bwana before ever we came," the Hottentot complained.

"A leopard village," King told Ponsonby. "That fellow thought he was big and tough enough not to take orders, so the Mahethebu wa Chui marked him."

For all of King's studied casualness, Ponsonby felt the chill tingle of one of Africa's darker aspects.

"What about these leopards, old man? Doesn't the Colonial government do anything about them?"

King shrugged. "They keep trying. But it's a big job and it covers a lot of territory. The Mahethebu is as secret as the Mafia. They meet masked, a sort of vigilante society or a Ku-Klux with African trimmings. Anybody doesn't do what he's told, they jump him some night and put the four gash marks on him with steel claws on their fingers. Anybody they've really got it in for, they pin him spread-eagled up against the village fence with a big wooden skewer through each upper arm and disembowel him with one swipe. Colonial police can never find out anything 'cause nobody dares to squeal."

Like all nomadic people, the Watanga lived in patriarchal, or clan, groups; each clan claimed grazing rights over certain territory and each carried its own distinguishing marks.

It was in the next clan territory that the distinguishing mark obtruded itself with an unpleasant jolt. The business of trading for food was accomplished by the same sulks that left King hardily unperturbed, but it was while a tall warrior was showing his sullen suspicion of the hardware offered that King felt the back of his head being positively bored into by Kaffa's eyes.

"Keep an eye peeled," he told Ponsonby. "The Hottentot has something." He knew that the little man's eyes missed less than would any monkey and he turned with casual assurance of ease.

"Aa-ah!" King's exhalation drew Ponsonby's head around in a flash. "Look at that guy's spear. Notice anything?"

"No—oh yes, these fellows spear heads are little short ones, not like your big chap's young sword."

"I mean, about their ornamentation around the haft?"

"No."

"Well." A brittleness was in King's voice. "It's the same as the broken end that stuck in your rhino."

"Was there a broken—I never noticed a—" Ponsonby's monocle fell to dangle on its string. "Good Lord, d'you mean to say that—"

His stare had the taut strain of a dawning nausea.

KING'S attitude of calm assurance had slipped from him like an unwanted

cloak. His whole body tightened up to wary expectation of the anything that

could happen in Africa. His eyes, pinched narrow, were flitting to light

momentarily on every detail of the scene—the groupings of tall sullen

men, their attitudes, the expressions on their individual faces, he noted

each and flashed to the next. He spoke without looking at Ponsonby.

"Means nothing—yet. Could be no more than just cussed coincidence. A spear could be traded from hand to hand across the continent. Or a nomadic hunter might travel a hundred miles. Or, at its worst, it could have happened right here, and a molested animal will then often travel a hundred miles, and a hundred is just about what we've come—Come along, Kaffa. Close the deal and let's move on into the open."

He said it in English. The little Hottentot would never admit that he could understand a word. But the deal was closed; the whip boys yelled and crackled little puffs of dust about their catties' ears; the wagon lurched and creaked on its protesting way.

King let it pass and fell in behind its dust, a rear guard against he didn't know what, stiff and erect, his back broad to whatever might be behind.

"Don't look back," he told Ponsonby. "Never let man or meat-eating beast smell a sign of nervousness." Out of the side of one eye he watched Ponsonby square his shoulders and adjust his monocle with a flourish. A laugh was always a good offset to any taint of nervousness. So King contrived one for the scowling populace.

"If your back crawls like mine, Britisher," he crackled his parting laugh, "we'll need a drink when we get out of this."

At the end of the village the drivers' sudden onslaught on their beasts swerved the wagon to scrape the very wall of the last hut. The Hottentot, too, stood to let it pass and fell in behind King to mutter:

"The middle of the road, Bwana! The wheels have not touched it."

King saw and stepped over it without changing his stride. It was a design marked on the ground so recently that tiny scrapings of earth still fell into the depressions; a rough oblong, each side of it consisted of four parallel lines scored deep in the hard packed dirt. Twigs and beans, prettily spotted, marked a design within the design.

"Bad medicine," King muttered, and he swore emphasis to it. "Damned bad medicine."

Well away from the village and out of sight behind mimosa scrub he called a halt.

"Council of war."

Ponsonby's innate sense of the proprieties were still unattuned to outlandish ideas.

"With your African servants?"

King grinned a rebuke. "Never having been a big shot office executive or an officer in an army, I got a crazy theory it's a square deal to the rank and file to let 'em talk their way out of the hole we're all of us in."

KAFFA the Hottentot did most of the talking. Not an item had his eyes missed. "It was undoubtedly a thahu, Bwana, a curse laid in our path by a mudu-mugu of the leopards."

"The leopards, certainly," King agreed. "For the lines are the four claws, raked into the earth with steel. But we were not there very long; how do we know that a curse was built so swiftly for us? Could it not be just a sign that the village is one controlled by the Wa-Chui?"

The Hottentot's wizened face contorted into myriad wrinkles of astute delight in interpreting even bad luck. "But it is simple, Bwana. The long figure of four sides is no man's house, for houses are round. It is the wagon. The twigs were the murumbiru shrub of sorcery and they were six, as we are six. The spotted beans of the castor oil were sixteen, as our cattle are sixteen and spotted."

"Damn if I don't believe you're right." King's frown studied the picture. "I don't suppose you could read just what the curse said?"

"Nay, Bwana, that is known only to the sorcerer who built the curse. We know only that the leopards are here and that they are hostile."

"And if they've got the gall to put the mark on a white man caravan, it means they're mad enough for mischief." King scowled into the distance from where they had come; then his brows lifted to shrug a dour optimism. "Maybe it's no more than a Ku Klux warning to stay the hell out of there. But all the same it'll be wise to be careful—and the best way to be careful, Little Wise Ape, is to up and run like devils other than the Wa-Chui were after us. Is it not so?"

The Masai growled his characteristic objection. "How many are we? Five good men; and even the white man with one good eye has courage and might be taught some small use. How many of the leopards can there be in one small village? Ten, perchance, or twenty? Kefule! Let us go back and demand an apology for this insolent witch writing."

The two whip boys only stared like their own oxen, round-eyed, willing to be led. The Hottentot chittered rage at the Masai. "So snorts kifaru, who has bulk but no wit. Children at monkey height know that where the leopards are strong they can order a whole tribe to sharpen their spears and blow the war horns. We know that they have been strong enough to tear the bowels from one trader because of his faithless metal. How will they know what trader's metal it was that betrayed their hunter to kifaru? Bwana, it is wiser that we go swiftly."

King nodded slowly, frowning down at his boot toe, and then more decidedly.

"Particularly, Bwana," the Hottentot added a grim observation to clinch the argument, "since two of those murumbiru twigs, the two largest, were peeled with a knife, white around the middle."

"The hell you say!" King relieved Ponsonby's impatience with a translation of the discussion. "And two of the sticks represent particularly us with our bellies laid bare to the ill wind that blows. So we're going to shove our pride in our pockets and run like hell."

Ponsonby's eyes, as the full significance of it soaked in, began to widen. King watched for the monocle to drop. "D'you mean to say, old man—" It dropped. "Excuse the personality, my dear fellow, but if you propose to run, the situation must be pretty dashed serious, eh? You mean you're going to abandon the wagon and all that and leg it?"

"Damned if I will." King bit on the obstinate refusal. "Let 'em know they've got us scared, and the whole district will be up and whooping on our trail. We're still armed white men—or at any rate one of us. We can hold 'em off in open country. But it's wiser to get out of this district instead of bulling on through. These people are more on the prod than I figured, what with this rhino trouble and all. We'll just head out southeast for the M'tusi country. That's traded by a fellow I know, and he carried a decent line of goods."

So southeast the wagon lumbered its labored course, steering wide of distant clustered ant hills that might turn out to be villages.

But dim drums throbbed in the hot air behind them and other drums whispered gutturally back from in front of them.

"I don't like it," King growled. "Drums could be no more than native jamboree, but they could be anything else, and these rhythms are new even to Kaffa." Savagely he rubbed in the lesson. "Here's one example of what lousy trade goods can do."

Ponsonby produced the standard defense.

"But it's an accepted business principle, my dear fellow. Export goods, so long as they're better than the local supply, always find a market. For African savages, then—what I mean, people practically in the stone age, any sort of a—"

King wouldn't let him finish. "That's a matter that'll boomerang back on your fat manufacturers one of these fine days. Nor I don't give a hoot if its cheap perfumery or shoddy cotton goods and tin pots. Any smart white man can come back and argue himself a repeat order on a worn out gee string. But weapons—steel—that's something else again."

"I'm beginning to see—"

"Damned right you are. Savages are practical people; their reasoning goes no farther than cause and direct effect. Lousy weapons, death, blood price. That's one cash consideration for your businessmen to look at, even if they don't give a hoot about somebody else's life."

His growl coughed harshly from him like a charging lion's.

"So here's us; two white men getting chased out of a district that's in a British colony—If we get out. I can't read those drums but, by golly, I know a war horn when I hear one. Eweh, there! You cattle drivers! Head for that rock kloof. We'll hole up till we see what's what."

BY the time they gained the rock outcrop and King, ferociously swearing, had

found defensive shelter between boulders that suited him, the drumming that

had been pervading the horizon had come to a focus. It was hidden, still,

behind mimosa scrub, but every now and then a wave of yells rose out of the

muttering roll.

"Talking up their courage," King grunted. "A mob is a mob wherever you find it. My guess is that our friends the leopards are whooping up the populace for a lynching." He slammed open the bolt of Ponsonby's new rifle, scowled disgustedly into the mechanism; then he broke open several packets of cartridges and laid them in fives, ready to hand.

Ponsonby watched him with the fascination of unbelief in what he saw.

"But, my dear fellow, this is a British colony! Pacified years ago and policed by rural constabulary, so they told me. There can't be a bally open war like this."

"Sure a British colony." King kicked rubble from under his shooting position. "A district official comes on tour every six months and collects hut tax and a white policeman rides through it every now and then and the local headmen come to his tent and report all quiet on the Western front. Sure it's pacified. And when this is all over, whichever way it goes, it'll still be all quiet. Because the officials will never hear a peep about any of it, unless it'll be that two more white men had an unfortunate accident with a leopard, or got bit by a snake or something. A lot of things can happen to a man in Africa. The Wa-Chui, I'm telling you, are more secret than the Mafia. It's black men keeping a secret against white. Certainly this country is pacified."

By this time the mob had come into sight. Dark shapes detached themselves from the farther tree boles and massed in a hesitant horde on the plain below.

"Humh! A good hundred of 'em. Well, a good white man with white man weapons has held off more than that of savages before now. Barounggo, go on down and tell 'em to get the hell back to their homes before widows will be tearing the spirit hole in the thatch."

"My sacred word!" King was becoming more unbelievable to Ponsonby by the minute. "You take it jolly cool."

King was able to grin at him under his frown of preoccupation. "Excitement neither thinks nor shoots straight. What's more, it takes disciplined men and leadership to rush a position against accurate rifle fire, and your Pax Britannica has taught the colored brother all about white man superiority. Taught 'em a long range rifle is better than a whole lot of spears."

Barounggo was striking his arrogant posture before the crowd. Naked except for a serval cat skin girdle, the wind ruffled his black ostrich plumes and monkey tail garters, the sun threw his great muscles up in high lights of yellow brown, glinted a long sharp line from his spear. A menacing figure, he swaggered before the mob. Imperious, belligerent, he shouted commands at them. They lowered before him like oxen. But here and there out of the crowd voices shouted back. The distance was a good three hundred yards, to far to distinguish what was being said.

King grunted. "See those conical hoods of straw bobbing about amongst them? And you'll note they keep well in the rear. Leopard men, masked, whooping 'em on."

"I thought there'd be more." King's coolness was vastly reassuring to Ponsonby. "I only see about ten."

"It's enough." King barked a sardonic laugh. "It's the same in any color; the lads smart enough to organize an ogpu talk the dumb clucks into doing the storm troop stuff. Damn, with a gun of my own I could pick some of those coyotes off from right here. But—" His mouth twisted down at the rifle.

Barounggo was stalking back. Before reporting to King he stood on a rock and waved his spear above his head in a wide threatening circle. Then he stood before his white master.

"They are insolent cattle, Bwana, and their talk has the cunning of leopards but the honor of hyaenas that eat corpses. They say, Bwana, that they have no war with black men, who are all dupes together. But the two white traders, they say, must pay the price of blood with blood. Therefore, if we black men agree, we may leave you here and walk away in peace. But if we do not agree, then I must wave my spear around as a signal and who falls in the fight, it is his fate."

"I take it," King said dryly, "that you decided for all of you."

"Nay, Bwana." The great fellow laughed his arrogant assurance. "What choice was there in such a decision? Can a man bargain with hyaenas?"

King stood up from his crouched position and reached a hand to grip the Masai's muscled shoulder. The rough tremor that went through his arm was all that he said. But his short laugh joined Barounggo's and his surge of pride was not above telling the thing to Ponsonby.

"Dashed sporting, I call it," said Ponsonby. "I jolly well knew he was a gentleman."

The creases of King's short humor about his mouth merged into other creases, deep set, very hard. His eyes pinched down to far sighting narrowness.

"So now they'll be coming." He crouched down to shooting position again. "I hate to do this," he growled. "These bullets will knock a hole in a man as big as a plate. And you can bet those masked Chui coyotes will see to it that it won't be their fate to get hit."

"Ngalio, Bwana!" The Hottentot shrilled warning. "Watch out! Now is the time to show them! That tall fellow, Bwana, who leaps high there towards the left. See, he leads a group of his household."

"Ye-eh! Poor dumb devil! He's got to be stopped." The heavy rifle roared out. The wretched man spun as though he had been hit with a sledge hammer and sprawled to be hidden in the grass. His yelling, eager troop shrank back into the mob.

THE mob milled and howled. The sun on brandished spear heads twinkled like

stars over a black night. Voices shrilled above the mob's hoarse hubbub; they

were the standard tones of the Wa-Chui designed to copy the snarl of a

leopard and to disguise their voices.

"Lousy balance," King grated. "The thing kicks like an old eight gauge, and throws high to left. That man should have dropped flat."

"Another one, Bwana! To the right of middle there! He with the ochred hair eggs on his troop."

The Masai stood impassively aloof and watched lesser men die. He took a little horn from his ear lobe, tapped snuff from it onto his great blade and sniffed it up with a windy inhalation.

The oxen drivers squatted and stared with white rolling eyes.

Ponsonby took out his monocle, polished it, put it back, took it out, polished it.

"Good Lord!" he kept repeating, and, "My sacred aunt!"

"To the left again, Bwana!" The Hottentot shrilled.

That overzealous leader paid his price.

"I say, old man!" Ponsonby was awed, his ruddy face white. "This is a pretty ghastly lesson, what?"

"To them?" King flared again as he spoke.

"To me. I mean about—well, trade goods and Africans and all that sort of thing."

"Told you you'd"—King fired again—"you'd learn. Experience is—Hell, they're coming fast!"

He snatched a five of cartridges, juggled them into the breech, fired, slammed out the bolt, fired. "Got to stop that rush, by—God!" The cry tore from King's throat as might a man's last strong cry in life.

"The blasted thing's jammed!"

He wrenched out his hunting knife and pried at the bolt in a frenzy. Then his breath fought strangled from him like a death rattle.

"No it isn't. It's broken!"

His hands on the gun gripped it as though they would in sheer agony of frustration twist the useless thing to further fragment. His throat gulped at its constriction and let his voice through, dry and flat, like somebody else quoting a platitude.

"Steel!" it said. "Cheap steel!"

The Masai bounded out of his impassivity. The Hottentot was already pawing at the weapon in King's hands.

"What goes wrong, Bwana? What so great evil is in Bwana's voice?"

It was not by any stretch of reflection Ponsonby's direct fault. But King looked only at him. He answered the question to him.

"White men," he said. "Weaponless!"

The mob below had been stopped by the grisly effect of those deadly smashing bullets. But only a few seconds of hesitant milling showed them that no more came. Their half-cowed shouting swelled to encouraging yells, surged to a roar of howling. Shrill leopard voices squealed high behind them. Their rush came in a dark stampede of straining bodies and twinkling spears.

Barounggo bounded to the front and stood on wide planted feet, his spear couched in both hands. His deep laugh rolled from him in a continuous growl.

King screamed at him. "No use, Barounggo! Drop it! Drop it, you damned fool!"

Barounggo never looked back.

"Some will yet eat spear. Ss-ssghee!" he shouted. "Come, cattle herders. An Elmoran of the Masai waits."

THERE was never any impractical heroism about King. His belief that anything

could happen in Africa was supported by a sturdy conviction that, according

to all the laws of chance, the happening could just as well be good, and if

it was not, then an alert opportunist might yet turn bad to good.

He rushed at the superb Masai maniac, took him unexpectedly. He snatched the great spear from him and flung it far behind. He screamed at him, "Six against a hundred! We give in. And if we white men survive the first spears there may yet be a chance."

He leaped back and scrambled to a high rock.

"Up!" he yelled to Ponsonby. "Up out of the first rush and let the leopards talk! They're not blood mad—not yet!"

High above the wave that surged up the incline, he held the rifle where everybody could see it and threw it away from him. The wave broke around the base of the rock, roaring. Spears thrust up at them. Screaming men jumped high to reach at them.

Leopard voices squealed high in command. The straw masks, like little steeples, fought to shove through to the now harmless front. Till presently there was a ring of them round the base of the rock, squealing and snarling for order.

Reluctantly the madness passed from the mob. Masks turned to stare at the most rebellious voices. The men cowered away from them.

A voice squeaked, "It is the white men. The white traders we take with us. Against black brothers we have no blood debt."

King looked down on it all. As ill a situation as the grim gods of Africa had ever shown him. He shrugged acceptance of he did not know what in store. His voice was flat and as grim as the turn that the gods had played on him.

He looked down at the Mahethebu-Wa-Chui. "The white men come. But our black servants go free."

A voice squeaked a shrill laugh from within a mask.

"The black men go free," it said.

"Come along," King told Ponsonby, "and hold a tight check on any superior ideas you may have about being manhandled by black men. Stand for anything, or the only argument you'll get will be a spear."

He slid down from the rock. Only two little pulsating ridges that swelled over his jaw muscles showed that he bit his teeth tight over whatever was to come. In silence as impassive as the Masai's he suffered the indignity of having his hunting knife wrenched from his belt, having himself pawed around, his hands tied behind him with grass rope.

It was the Masai who shouted, raved from beyond a barrier of a score of men who held spears to his chest. They laid insult on the Bwana Kingi, he roared. Kingi, mwinda na simba, the hunter of lions, na pigana n'gagi na mikonake, who fights gorillas with his hands. Kingi, whom an Elmoran is proud to serve. He shouted threats. He would make a war, he promised; he would raise twenty men and bring desolation to this insolent tribe.

He even demeaned himself to threaten that he would so far let vengeance out of his own hands as to bring the Serkali, the white man's government, down on this district.

Some of the spearmen turned away their faces so that they might not later be recognized. Some dropped their eyes and muttered half apologetically that they had no quarrel with the Masai people; it was only white traders that they had been ordered to attack.

But a derisive voice squeaked out of a mask: "One white trader has paid a little of the overdue price for our many young men who have died. What difference is there in these two?"

"What difference?" King barked a bitter little laugh. "How can these people know the difference till they've tested the goods? All right, Barounggo. It's no use. Take charge of the wagon and take it out by way of the Ndolia mission. It is an order. I will meet you there. It is a promise."

Round holes turned to stare at the effrontery of it. No derisive comment came from any mask. Dully suspicious, the very attitudes of the grotesque little steeples of plaited straw, some thrust forward, some perked sideways, indicated that they wondered what unknown power this white man might still have up his sleeve that let him be so calm. But since no further portent emerged, no sudden modern magic of destruction, they gathered up their resolution and herded their prisoners before them. The rabble streamed down the hill to the open plain.

King growled a certain satisfaction. "That'll keep Barounggo out of anything rash for a time, anyhow." He nudged Ponsonby with his elbow. "Go on, talk. Laugh. Make a show of it. The tougher we brag to these fellows, the more they'll think before doing anything."

Ponsonby's stiff British upper lip was able to respond. His tone remained as naturally casual as ever, even hopeful.

"Did you mean that, old man? About meeting your wagon at some mission? It wasn't just a—a Yankee bluff?"

King produced his hardy laugh. "Hell, the wagon's safer'n we are. Men can have an unfortunate accident and a village headman can offer the next constable patrol the evidence of bones that tell no tales. But goods talk. If any native village would suddenly be unduly rich in hardware, some bright policeman would start putting things together."

"Awf'y consoling and all that, my dear fellow, to know that your wagon load of goods has a chance of getting out. Quite jolly. Ha-ha-ha—Haa-aah— Oh! Dammitall, there goes my bally eyeglass!"

It seemed so ludicrous that the monocle dangling on its string was the major tragedy that King cackled a response. The natives stared owl-eyed and muttered to one another over these white men who in their circumstances could still laugh.

THE cortège reached the fringe of brush out of which it had come. The straw

masks squeaked commands. The rank and file obediently drifted away in their

various directions to their respective villages.

Only masks remained to prod their prisoners with spears into a path that none of the others followed.

King grunted. "So the Leopard Society stages a private performance before it gets to the dirty work along the village thorn fence. That's something I didn't know about them."

Ponsonby stared at him with eyes as blank as holes in a mask. "Seems to me these chappies—nine or ten of them, aren't there?—would be enough to do something pretty ghastly to just two of us with our hands tied."

King grated a harsh chuckle. "That order about taking care of the wagon wasn't all of it a bluff. It kept the boys out of any foolhardy trouble when blood ran hot and it leaves us now with four men free and wide open to help us. Four good men to ten or eleven is a heap better odds than to a hundred."

Ponsonby remained pessimistic. And reasonably so. Hands tied, hustled by spear points that callously drew blood with every prod, driven like a sacrificial goat along a faint trail that twisted through thick thorn scrub, he was hardly to be blamed.

"Four African servants." He stated his near despair, and his smile was only a set grimace now.

"Not servants," King snapped. "Two of them, perhaps, the two drivers. But the other two are men who've been through enough tough spots with me to stand by in this one."

"Your Masai, yes," Ponsonby conceded gloomily. "But how long will it take him to round up any help? How long have we got before—" He wet his lips to continue the grisly thought that was in his mind, and then shut them down tight on it.

"Not the Masai. Kaffa."

"The little Hottentot? Why, he's the timid one!"

King scowled his troubled introspection as he plodded along. At times his lips tightened over his memories; at times they let go again to break in the beginnings of a pale smile. "Timid—like an ape. He can't offer to fight the world single-handed, yet I've seen a hamadryas baboon jump a leopard when his superior intelligence told him his chance was good. It's wits we'll need to get us out of this hole, if at all. And wits is what the little Hottentot fights with."

"I hope you're jolly well right, old man. The nearer that sun gets toward night, the less I can keep from thinking of Piet Vreeden. And listen to these fellows. They're talking in their normal voices now. Seem pretty cold sure that nobody will be in a position to give evidence against them. D'you want me to laugh just to show my bally nerve?"

King did not ask him to laugh. He did not laugh himself. He said only: "This much at least we're sure of: they're not warriors and they're a secret organization, just smart enough to get braver men to do the front line fighting for them—and there's folks who hold that a gang that operates under masks isn't so long on guts."

It was little enough comfort.

It was still daylight when the twisty path suddenly turned another corner and came out on a clearing in the thorn scrub. Not a village, just a space that stank of human usage and had a fringe of huts around a third or so of its arc. A little apart was a single, much larger hut. That was all. That and the close, thorn jungle.

The white men were shoved into a hut, darkly odorous. Nobody said anything to them. But two broad spear heads that moved in silhouette before the open oblong of the doorway showed that escape would be a futile thought. Not a sound came from outside; there was only the blank silence of the jungle in that period before the dusk when the day creatures are thinking of sleep and the night creatures are thinking of waking up.

Through the doorway the prisoners could see the solitary larger hut, over its doorway the ominous fraternity insignia. A white leopard skull.

"Pretty slick," King grunted. "If any copper should ever chance on this, all they'd have to do would be to hide away that skull and the place would be an innocent thiringa, a community club house for the unmarried men who get troublesome around the village women and so get chased out by the elders."

"Really, old fellow," Ponsonby snapped at him. "I can't get interested in African ethnology just now. How are your wrists? Any chance of wriggling free?" His own dry panting showed that he strained at his own ropes.

He fell silent. There was nothing cheerful to talk about.

DARKNESS came. The night woke up and talked the dark secrets of the jungle in its varied tongues—trills, squeals, snarls. No honest, full throated lion voices, for the jungle holds none. All the voices were furtive, all engaged in the merciless necessity of killing some smaller thing to eat. The moon came up to let shadows crawl over the yellow ground. The broad spear heads moved restlessly before the doorway.

It was Ponsonby who suddenly uttered a gasping, "Good God!"

"Huh?" King had been brooding over his slender hopes, his eyes focussed on nothing.

"An—er, a large animal just ran out of the jungle. Right into the door of the big hut. It—I thought it looked like a leopard!"

"Aa-ah!" King's throat made the form of his characteristic exclamation, but the sound of it was nearer to a moan than he cared to let himself hear. He swallowed hard before he was able to say, "I've heard of this. M'cheso mya Chui, the leopard dance."

"What does it mean—for us?"

"Not so good." King held his voice hard between his teeth. "A sort of cat and mouse game with their victims. Keeps the mice just alive till the cats get tired and take 'em over to the village thorn fence to let the public see what happens."

Ponsonby said nothing. King heard him swallow dryly in the dark. The "animal" came out of the big hut. First a flat head with wide gaping teeth, white in the moonlight; it peered with feline caution round the doorway. Then the spotted body followed, sinuously hugging the door post. It crouched. Then it emitted a throaty, mm'mr-r-r-row, like a magnified cat calling to its family and it rolled in a moon patch to bat at the air.

Then Ponsonby could see the spotted legs flat and tied over the man's chest and flanks. Another leopard ambled towards it, out of one of the smaller huts. The first one, with marvelous agility, leaped high and away and poised with arched back.

Others came to join in the dance—the play, rather, as each of them had watched leopards play in the jungle and now copied their gambols. The human rendition of it forcefully emphasized that the whole play of the great cats is designed by Nature for practise for the two sole purposes of their lives; either for the capture and cruel wearing down of their prey, or for fighting amongst the males, the tactics of which is to grapple and disembowel the antagonist.

King whispered, "When they get tired of that, they'll pull us out. Leaving our legs free so we can run like rats and make sport."

Ponsonby was able to keep a steady voice. "Looks like a sticky end, old man, D'you suppose, if we could kick one of them good and hard in the right places, he'd get savage enough to make it quick?"

But the leopard men were not tiring of their play yet. They seemed to possess all the vitality of the cats they copied. The moon was coming up behind the prison hut. As though by calculated refinement of cruel design, the black door framed the shapes of the broad guarding spears and the moon-flecked jungle amphitheater with its back drop of the leopard house.

It was a consummate imitation that the fraternity brothers, with all their savage faculty for mimicry, gave of feline play. Purring against the door posts like homing cats, sniffing the air for danger; madly across the clearing, frisking in the jungle fringe.

Something he had never noticed before was forced on Ponsonby's half hypnotized fascination—that the cats are noisy only in actual fight.

In the broken light it was startlingly easy to take them for the beasts they copied, but the moon glinted silver every now and then from great steel claws.

Only the muted pad of feet and the furry chafe of colliding bodies came. The surrounding jungle shuffled and squeaked and furtively crouched to watch man, the master beast, prance.

It was King whose sudden shout showed how tautly the spectacle had been stretching his nerves.

Immediately a leopard-capped head peered inside. The rest of the body followed and the rank stench of ill cured hide filled the hut as the wearer groped to assure himself that the prisoners remained tied.

The man grunted assurance to his companion and went out.

King's whisper to Ponsonby was fierce in its exultation. "By God, I knew he'd figure out something! Watch that leopard by the jungle's edge! Just around that big tree trunk! That littlest leopard of the lot!"

The smallest leopard emerged to prance with the others.

"D'you mean—?" The question was hoarse in Ponsonby's throat.

"Cripes a'mighty, I told you he was smart. Watch him imitate the others. Timid, huh? Like an ape."

The little leopard's mimicry was exquisite. He cat-footed with the others. He rolled on his back and batted at moon shadows; he let himself be chased and sprang away sideways on stiff legs. He chased others. He hid as they hid—

And carefully he pranced always in the most shadowy spots.

The clearing would be empty for long pauses at a time, filled only with a sense of intent watching from behind obstacles; the emptiness broken by a rush of bodies that would almost meet headlong, would leap high and would race away to be chased into hiding again.

The smallest leopard leaped with them, raced from them, sat on his haunches in affected cat indifference and licked at his flanks in grotesque postures, sprang high, scuttled away as others prowled near.

King's hardy confidence that had sunk closer to despair than he cared to admit needed no more than that small mushroom of hope to swell to its normal alert preparedness.

"Three to eleven. We unarmed. That's odds a little stiffer than I had hoped. But I don't see how it could be any different here. Watch that beautiful little devil. Watch the craft of him. By golly, I'll buy him six wives for this."

THE little leopard's craft was apparent in his gamboling ever closer to the

prison cage. He would stop in the moonlight and peer into the darkness of the

door; he would sniff as though scenting mice. Once, when the clearing emptied

of dancers, he slipped close and was instantly swallowed into the black

shadow of the hut.

"Aa-ah!" King tightened all over. But a leopard man raced out of his hiding to meet another in mid clearing. Others pranced into the mêlée. The smallest leopard skipped away to gambol around them.

Twice again it happened. Twice within the next twenty crawling minutes the clearing emptied of cats and twice the mice held their breath. But each time the little one was prowling just too far to make use of his chance.

Those were the most excruciating minutes of the whole imprisonment to King. It was the warm stickiness of his hands that let him know that he must have been straining at his bonds until the coarse grass rope had rasped his wrists to bleeding. An awful thought assailed him that the thing was by design: that the cats cunningly knew and that, sure of their mice, this was exquisite refinement of their play. The wetness that oozed down his face from his forehead was salty on his dry lips.

When it came, it was without any preparation of tightening nerves, with the sudden silent ferocity of a leopard's pounce.

King did not even know that the clearing was empty. All he knew was that one of the guards in the outer dark grunted a startled question to which the answer was the soft hiss of metal piercing flesh, followed instantly by a muted gasp, and then the sound of limbs subsiding on hard packed earth.

Then out of the darkness on the other side of the doorway came an astonished challenge. "Mtu yupi? Kunani? Who's that? What's happening?" Followed quickly a repetition of the swift blade to flesh.

The doorway darkened to a quickly ducking shape and the Hottentot's voice came, vibrant with a fierce satisfaction.

"This time I was hiding in the shadow of the hut." And a wailing little cry. "It is well, Bwana? Are you in condition to fight, Bwana?"

Before King could reply the Hottentot had nosed him out like a dog and was whimpering as he felt for lashings to be cut.

King was laughing softly, the low crackling laughter of relief, of action after near despair.

"It is well done, little Apeling. Now loose the other one." He was flexing his fingers and stretching his shoulders. "Where is now Barounggo?"

The moon-speckled clearing was alive again with posturing, leaping, cat shapes, too preoccupied with their play to discern in the black shadow of their mouse trap that guards slumped on the ground rather than stood upright.

"Barounggo," the Hottentot said, as pleased as a small child, reporting obedience, "is already on his way with the wagon to the Ndolia country, as Bwana ordered."

Ponsonby's whisper was tensely urgent over his shoulder. "D'you think, old man, we'll have a chance to sneak out the next time they go into hiding?"

"Not one in a million," King said with a cheerful finality that was surging to high tide after its depression.

Kaffa's dark form ducked out of the doorway, ducked immediately back. "Their two spears, Bwana. The sowing of Barounggo's many lessons to Bwana will now bear red fruit, and my knife has already learned the road to silence. It is enough. And the glass eye might also be of some small help. Let us go swiftly before ill fate leads one to look close."