RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on a vintage pulp magazine cover)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on a vintage pulp magazine cover)

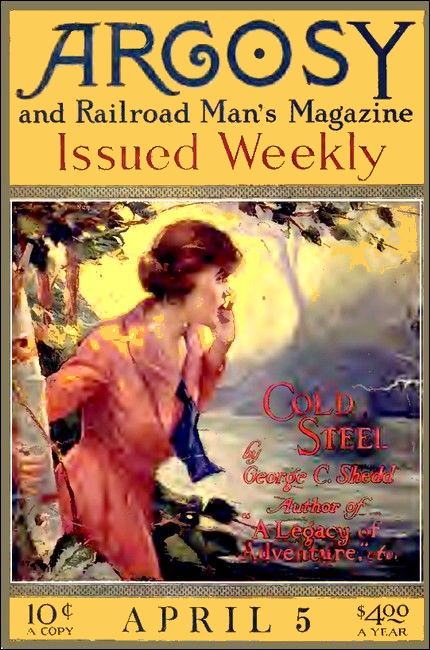

Argosy and Railroad Man's Magazine, April 5, 1919, with "Jehannum Smith"

THE Hotel Oriental was unusually silent—no, not "unusually"; the word is misleading, because the thing happened every so often. Uneasily, perhaps, describes the prevalent air of expectation better.

Lithe, brown Hindu boys dressed in clinging white chupkuns slipped noiselessly about their business on their bare feet. White guests dressed in the coolest ducks or tussar silks lolled with their feet up on long-arm cane-chairs in the far end of the veranda and sipped pale yellow fizzy drinks libelously described as Scotch while they talked in low tones and smiled with understanding tolerance.

The hotel manager, a one-fifth Portuguese from Goa, who bore the proud name of Senhor Dom Roderigo Cardozo, peeped at intervals from one of the many curtained doorways and hoped for the best.

And all this because Jehannum Smith had come back. Not from the war—he had come back from that some little time ago. "Invalided out," though nobody could understand exactly why, for Smith was generally described as being the size of a door, and all his limbs were still where a lavish nature had placed them. There was some talk of shell-shock; but most people refused to believe that that kind of shell could be made.

Not that Smith was abnormally huge; he wasn't more than a decent six feet or so by some two and a half wide. There was something about his face, rather, which had been carved by an unskilled workman out of red granite with an ax, which gave the impression of immensity and strength and domination. That, and his ideas, which on these occasions of his coming back were colossally magnificent.

All the Far East, for instance, remembered with joy the time when he had conceived the splendid notion that he was the Ameer of Afghanistan, and had gone forth to purchase the Y. W. C. A. as a suitable nucleus to his establishment.

This coming-back habit of Smith's needs an explanation. There would come periods into the great man's life when his soul seethed within him at the sameness of things and the taste of the world was as sawdust in his mouth. Then he would become restless as an elephant about to go must, and his fellow men would note the symptoms with uneasiness.

"Gorblimey," Smith would say presently, when the urge within him grew too puissant for mortal soul. "Strike me pink, but I got to go on a exploration or somethin'." And forthwith he would go.

His camp equipment consisted always of the same impedimenta: a half a dozen of whisky and a package of crackers. With these and his native boy he would disappear into the uncharted jungles. After the passage of days he would "come back"—having all the crackers and none of the whisky!

Where he had been or how he had lived nobody ever knew. Sometimes tales would drift in from frightened villages of a portent in the land; but even the district commissioner could never get a word out of Smith.

His demeanor on these occasions was a vast and momentous solemnity, marked by an unblinking stare from wide, gray eyes, which were as devoid of all human expression as those of a long dead fish, and his speech consisted of the passionless consignment of all who addressed him to Jehannum—which is the colorful Oriental conception of the lowest of the hells.

Smith, then, had "come back," and the Hotel Oriental waited in anxious expectancy. Not that Smith was quarrelsome; far from it; but his mind on these prodigal home-comings was like the unaccountable grease on the fly-wheel. Nobody knew at what amazing tangent it might suddenly fly off. And it was always possible that Smith might have somewhere about him artillery suitable to his size.

Everybody remembered the joyous occasion when an offensively overbejeweled Bengali princeling, who had been educated at Eton—and was therefore, of course, quite the equal of the best white men, and better than most—had spoken in a proprietary way of some fluffy member of a pitiful traveling musical comedy show from Australia. The show, of course, was white; and the prince was—a raja!

Now, individual white men can never learn to regard these loose-lipped vaporings with equanimity. Governments somehow seem to think differently; and princes, whether of blue blood or brown, weigh heavily in the scales of those who sit in the high places. The group, therefore, seethed, but said nothing.

It was Smith who had risen with massive dignity, and with the sightless stare of a dead man had reached out a vast, slow hand and clutched the scion of royalty by a bunch of his embroidered vest while he announced his passionless determination.

"I'm goin' to pull all the arms an' legs an' things off'n you, an' then let you go!"

When an army had finally accumulated and subdued the outraged white man before anything could happen which the official utterances could "deplore" as an "unfortunate incident," they had taken from Smith's person five revolvers of various large calibers—all of them unloaded!

It will be readily understood, then, why the Hotel Oriental watched and whispered and waited.

Smith sat now in the open veranda before his room, stiffly straight, with his thick forearms resting on the arms of his chair quite flat, like a sculptured Egyptian god, contemplating the vastness of nothing with the solemn impassiveness of the ages.

His boy slipped from behind the curtain, which was the only door to his room, and salaamed. It was apparent to the men in the far end of the veranda that he was making lengthy orations; but Smith sat like a stone god.

This native boy is worthy of mention. He was a Madrasi from Salapore, whose inherited cunning had shown him at an early age that it was a discreet and profitable maneuver to become a "curry-and-rice" Christian. That is to say, being without a job and devoid of money, he went to the local mission professing a vague unrest of the soul which was beyond his understanding. The good fathers joyfully embraced him, clothed him, fed him, taught him English—a very fearful tongue—and in due course baptized him, exchanging his patronymic of Poonoosawmi, relic of paganism, for the Christian name of Paul.

After which Paul gently faded from the ken of the mission; for he was now a member in good standing of an extensive series of clubhouses. By the simple expedient of going to a tin chapel, of which there are many in the land, he could obtain at any time food, shelter, clothing, if necessary—which was always. Having thus acquired a veneer—a very thin veneer—of the true religion, and adapted it to suit his inherited beliefs about godlings and devils, Poonoosawmi Paul had long ago lost the faculty of distinguishing between right and wrong; with one ineradicable exception—that whatever his master said and did and thought was right.

This exceptional boy, then, stood before his master's chair and delivered himself of a quantity of the English which he had learned at the mission.

"Marshter, I telling true thing. This one verree high class gentleman; rupees he got like bug on damn nigger fellow's coat. From long distance—America—coming and tell only for see marshter."

Smith stared motionless into space for three full minutes. Then at last his lips moved as an oracle might speak.

"Ow jehannum!" he said without passion; which is good Arabic and comes from the same root as Gehenna.

The boy salaamed gratefully and pleaded further.

"But please, marshter, this feller making superior business talk. Plentee rupees you get."

Thus adjured, Smith remained rapt in the contemplation of a hazy infinite. The boy salaamed again and withdrew—but no further than behind the curtain of his master's room.

After a blankness of meditation which lasted an hour, some germ of an impression seemed to have made its way into the giant mind. Smith rose suddenly and made his way with the accuracy of a sleep-walker along certain corridors. Instantly his boy was at his heels, skilfully directing his steps; and presently he darted to the front and drew aside a curtain.

Within the room so unceremoniously invaded sat a gentleman whose first impression was cigar, whose second was fat gold chain, and whose third was keen business. The gentleman showed neither surprise nor annoyance at the invasion; he was used to the queerest-looking people in the world with the most staggering manners bursting into his presence unannounced. In fact, he was looking for such people; for he was a vaudeville manager.

Smith stood in the doorway and gazed at the man with wall-eyed gravity for three long minutes. Then he raised an unwavering finger at him.

"You go to 'ell!" he announced momentously; and he executed an about-face with military precision.

But the vaudeville man was accustomed to dealing with temperaments which were very much more startling than Smith's; artistic temperaments had been one of his daily trials for many years, and he had a long experience in not letting a "find" get away from him.

He made a bound for the door, skilfully twisted his caller's maneuver into a complete turn, deftly piloted him into a chair, and with the grace of a conjurer produced a selection of cigars. Smith's astonishment at the swift efficiency of the gentleman from the other side was such that he stayed where he had been put. The genial one lit a cigar for himself, then another for Smith, and plunged into his business.

"Now, then, Mr. Smith, here's my proposition. I'm here looking for good head-line stuff; an' I've heard a whole lot about this classy dancer who's making such a splash in some back-woods Hindu temple around here. Now back in the States we've had a raft o' phony princesses from the Jersey side who've got nothing except a good press agent; an' I'm ready to gamble that the genuine article properly handled will pull a high number in the three figures a week. How 'bout it?"

"Yuss," said Smith ponderously. "Ho yuss. Five 'undred rupees."

"Oh, sure," the manager agreed. "Only I'd make it dollars; and that's goin' some for a one-girl dance specialty these days. Now the way I dope it out, these temple janes are kinder prisoners, so to speak; their makin's goes to the management, an' all they get is their keep. So I'm figurin' that this queen, will he tickled stiff to come to a free country where her salary is her own—of course, I'm entitled to a fair com mission for my risk, an'—"

Smith interrupted him, solemnly weary of all this unnecessary talk.

"Five 'undred rupees I calls fair."

"Oh, I guess I'm entitled to more than that, Mr. Smith; all expenses, press stuff, railroading an' all that coming out o' my pocket. But she'll get a square deal from me; I'm no cheap John agent, I wanna tell you. Now, see here. If you'll take up this job I'll pay you your own figure an' expenses on the side. Whatever graft any body's got to get is covered by—"

Once again Smith interrupted the voluble agent. The glassy eyes had closed in the extremity of boredom; and with the shutting out of that codfish stare the hard-chiseled face suddenly stood out in all its rugged strength.

"Five 'undred rupees," came the monotonous murmur.

"Aw, say, now. Five hundred rupees is pretty steep for just expense money. But gee here, I'll make a deal with you. All these poor pikers around here say they're scared to tackle the proposition, and they tell me that you know these Hindu ducks like a book, and if there's anybody who'll take on the job, you're the—Say, mister, are you—what th'—well, whadda ya know about that!"

The agent's voice trailed away in disgusted astonishment; for Smith had incontinently gone to sleep. Nor would all the agent's shouting wake him; and to lay hands on that massive figure struck the other as a gamble which was a little too precarious even for his irrepressible spirit.

For half an hour Smith remained like a dead thing, while the vaudeville man raved. Of all the queer characters he had met none had been as impossible as this.

Then suddenly Smith's eyes opened wide. Without a blink, without a suspicion of the daze which marks one who has just slept, without a word, he stood bolt upright on his feet and walked solemnly from the room.

As he reached his own quarters Poonoosawmi appeared from the veranda side of the curtain and busied himself about trivial nothings while his master gazed vacantly from the window. Presently the boy coughed gently in preparation, and his question showed that he had been listening.

Without shame he spoke; for why should there be any; was not his master's business also his?

"Marshter, you going ketchum this nautchni woman?"

His master's answer made up for its trifling inaccuracy by its staggering matter-of-factness.

"Yuss, me son. Five 'undred rupees we gets for the job. Three times the blighter tries to cut me down; but five 'undred I says resolute, an' I'll go yer, he says."

Poonoosawmi knew better than to argue this statement; but he pleaded earnestly against his master's resolve.

"Oah, marshter, please. This bloody awful madness. Temple female is holy thing. All the time this man making steal away talk my liver is turning all into water. I am expert in all kinds of priests, marshter, and I telling you, this Hindus is damn bad fellows. Vengeance in his catechism is not for the Lord's; it is for the priest craftiness; and their forgetfulness is not."

"Poonoosawmi," said Smith. "You shut up an' go to 'ell. Now it's this 'ere Malka Devi who does the hootch in this bloomin' old temple o' Mahadeo out on the Goobari Road that the gent wants, ain't it?"

"Yes, marshter, she is of most expensive beautifulness. But please, marshter, Mahadeo is verree powerful god; if he is angry he can turn all fellow into monkey."

"All right, me boy, I'll remember that," said Smith. "So now you run an' tell the bloke we'll bag the loot an' deliver tomorrow morning; an' he's to 'ave the poisha ready. Five 'undred, he said, an' not a pais less."

The boy knew that argument was futile. He bemoaned his master's madness, in which he had been so cheerfully included; but he sped to the room of the zealous vaudeville agent. To him he paraphrased his master's message.

"Sar, my marshter telling you damn fool for hell. Therefore to-morrow morning time he is putting girl in the bag and deliver loot for five hundred rupees f. o. b. This much my marshter telling. But I telling you for safetyness: you take this female in the arm and run golly for hell in the ship. For priests is verree blood-curdling man; he is stabbing the belly, cutting the throat, he is putting arsenic in the rice; you one time malakathwabi dead."

Having delivered his message and his warning, Poonoosawmi salaamed deeply, and turned to dart from the door.

"Hey, wait a minute there," the astonished manager called. "Let me get this straight. You say your boss is going to grab off this queen? How's he propose to pull the stunt?"

"That knowledge, sar, is for my mysterious wondering. My marshter say ketchum. All right; can do. What I know how can? My marshter is verree great man."

With that the loyal youth ducked out and hastened to be at his master's orders for the preparation and planning of the great coup. Mr. Smith reposed in a cane chair with his feet on the extended arms. His orders were:

"Boy, you hurry up an' bring me a whisky peg!"

That was Smith's last word for the rest of that day. His thoughts, if he had any, were hidden behind the mask of the idiosyncrasies attendant upon shell-shock. The vaudeville manager's high hopes sank with long leaps as each successive inquiry showed that Smith still sat in his chair with his eyes-closed.

"Guess he's a four-flusher," he muttered in angry disgust. "Looks like it's up to me to round up some other attraction."

YET, when the quick tropical night had fallen like a moist blanket over the land, two figures strode swiftly down the Goobari Road. From time to time they shrank aside into the dark teak jungle which fringed the highway, as parties of men, obviously late worshipers, advertised their coming from far ahead by the gleam of lanterns which served the double purpose of disclosing scorpions in the path and frightening away the devils in the tree-tops.

About a quarter of a mile from the temple of Mahadeo, the more massive of the two figures struck boldly into the jungle. The smaller followed; but it was plain that there was reluctance in his steps. He kept casting uneasy glances over his shoulder and upward as they passed under low-hanging boughs. He crossed himself devoutly and fingered a greasy scapular, which he always wore under his thin coat next to his skin.

He set great store by this scapular; for tightly sewn into its folds was a five-sided cylinder of pure iron which had been guaranteed by a yogi of great merit to drive away each of the five different kinds of bhooths which haunted the forest land.

Presently the smaller of the two marauders spoke.

"Marshter, how you grab this nautchni from inside?"

"How should I know?" his master grunted. "When we gets there somethin's bound to turn up."

He plunged on through the darkness till the jungle began to thin a little, and presently a high wall loomed before them. He grunted again and surveyed it for a long time in silence. It looked almost as though he slept standing. The boy broke in on his contemplation.

"Marshter, to-day—afternoon—what time you craftfully plotting I coming this temple for worship, the arranging whereof is thusly: Outside is wall. Middle side is outside court, inside court, holy place, and god's house. Surroundings is garden, priest's house, mango tope, tank, women's house, and what not."

"Well, I knows it," was his master's amazing' comment. "But Poonoosawmi, you're a jewel, says I. Therefore, sit you on the wall-top an' wait whilst I goes on a exploration."

He took the boy by the waist-band and hoisted him to his shoulder without an effort. Then with one hand under the soles of his feet he heaved him up like a weight-lifter, the boy clawing wildly at the wall the while, till presently he lay like a limp sack across its summit. But he quickly straddled the top and reached down a helping hand. Smith, however, drew back a few paces, made a quick rush and a superb leap, and his finger-tips just hooked over the coping.

It was all he needed. In a second he was sitting alongside of his servant and surveying the great enclosed square which was to be the scene of his coming depredation.

In the dim glow of the tropic starlight the various buildings were easy to distinguish through the lacy fretwork of the mango and orange trees. Far out to the front, near the road, lights flared smokily; and every now and then a gong banged and a conch-shell blared as some fanatical shadu assailed the demons which lurked ever with malicious intent about the holy places. Back by the rear wall everything was dim and silent.

"That thing females' quarter," Poonoosawmi indicated. "But marshter, please. Sitting by my alone is a ghostly labor. For bhooth I got sacred amulet; but in presence of this Mahadeo fellow I am verree fearful man. Becoming riled, monkeys he can make."

"Ho, ken he? Well, me boy, there's a time when I has a argument with this 'ere same Mahadeo; an' I sloshes 'im in the belly with a coconut; an' a million o' priests comes yawpin' for to cut out me gizzard; an' I metagrobolizes 'em by battalions. But I ain't no monkey yet."

And with that the amazing man leaped like a vast ape to a perfectly impossible branch and was lost in the heavy shadows of its foliage. What wild adventure of his past lay behind that incident of the coconut, Poonoosawmi never knew; but he sat and waited in contentment, for his faith in his master was infinite. He saw him drop springily from a lower limb and melt into the darkness in the direction of the women's quarters.

The staggering thing about the whole proceeding was the sublime carelessness of the man. On that exalted soul such trivialities as preconceived plans or disguise had never impinged their troublesome presence. There he stood, a white man in a sacrosanct enclosure restricted to a fanatical creed where even governments did not venture to interfere.

But paltry considerations such as these never troubled that soaring spirit. If the thought came to him at all, it was immediately counterbalanced by the supreme conviction that whatever untoward thing might happen, something equally unexpected and astonishing would immediately happen to offset it.

He ambled on therefore in the dark till he came to the women's lines, a long, low barrack, removed quite a way from the rest of the temple buildings, just a series of single rooms, hardly more than cells, with a door in front and a grated window in the back. The doors opened out on a long veranda with a floor of stamped earth in which those unfortunate creatures who had been dedicated to the temple service cooked and ate and lived, and did everything, in fact, except sleep.

From most of the windows the wretched light from open chirag lamps threw flickering shafts which lined the barrack with a series of dim gun-ports.

With amazing directness Smith strolled along the rain-gutter and peeped into each window till he was satisfied that he had found the boudoir of the beauty whose fame had reached all the four corners of the land. None too softly he called her name.

In an instant the woman was alert. Intrigue is the life blood of the women of the Orient; and for most of them, penned up as they are, it is their only relaxation.

Smith spoke a low bazaar Hindustani with the fluency of a coolie. After twenty minutes' conversation with the girl her only anxiety was the hazard of escape.

"All that is necessry, O nautchni, is a thick pole wherewith to pry off the bars of thy prison," said Smith simply; and there upon he shoved his hands comfortably into his pockets and strolled off with the fixed idea of finding a pole somewhere about the grounds in the dark.

There was no slinking, no crouching behind trees. Somewhere against the walls, Smith knew, there would be a lean-to or a shed containing garden tools; and he began a leisurely exploration with the directness of a man going about his legitimate business.

Fortunately the far walls were, of course, deserted. Quite fortunately again the dilapidated outline of a lean-to bulked presently ahead. Smith found himself treading in a sand path, and he strode forward with eagerness.

Then three figures drifted silently out of the dimness in front of him.

They were dressed in a single robe of dingy muslin which encircled the waist with certain prescribed folds and draped the loose-flowing end over the shoulders. It was their only garment. Even in the dark they were instantly recognizable as priests of Mahadeo. They stopped in surprise at the crunching of boots on the sand.

"Kaun hai? Who is there?" one of them called.

Smith stared in their direction. Slowly his head lowered like a bull's, and he swelled with indignation at their interruption.

Then:

"You—you go to 'ell;" he growled.

The priests came forward, wondering at this strange greeting, and peered at the queer figure which wandered in their gardens. For a few minutes the reality of the horrible happening was unable to impress itself on their brains. The thing was too inconceivable.

That a non-Hindu should defile the interior of a temple was unthinkable enough; but a Christian and a white man! So frightful a sacrilege just could not happen, that was all. Yet it stood there and growled at them.

Their eyes began to open wide in fanatical rage. The first instinct of a native when surprised in any way is to yell like a siren horn. The foremost of the priests opened his mouth, and then Smith, with a sudden spring, clutched all three of them in a vast anaconda embrace. For crucial minutes the four shapes merged into a single, swaying bulk in the darkness; the priests struggling to yell for help, and Smith straining all his gigantic muscles to choke them to silence.

His great arms, long as they were, could not surround all three, of course, but their loose robes which offered such a satisfactory grip helped wonderfully. The best that the panting three could accomplish was a choking squawk from time to time which Smith discouraged by a tighter squeeze.

But at last the great fellow got the hold which he had been trying for. He settled himself and tightened his grip. Then, like a hammer-thrower, he grunted with sudden effort and put all the strength of his swelling muscles into a whirling heave. Limbs flew up in the air, billowy robes spun in serpentine curves, and the whole straining mass thudded together to the sand.

Smith possessed a fist of the size and consistency of a paving-stone. Where it fell there followed silence. Three times in lightning-quick succession it dropped; and then Smith sat up and scooped the sand from the back of his neck.

"Gorblimey!" he panted. "Nerve o' the bloomin' 'eathen! But, so 'elp me, I only socked 'em knockouts; I ain't killed a one o' the three—I don't think. They'll come around in about 'arf an hour an' 'owl ruddy murder."

With slow deliberation he felt for a head in the dark, and finding one, dragged it with easy confidence across his lap and gagged it most efficiently with strips of its own garment. The other two he served the same, and grunted his satisfaction.

Then, as he contemplated his handiwork, a quaint conceit came to him. He considered it gravely; and with consideration its allure grew. With sober seriousness he rolled the inert forms out of their robes, laid them carefully side by side like sardines, and then rolled them into a single huge bundle which he folded over and knotted and tied with elaborate care.

"I'll drop 'em down a bloomin' well somewheres," he murmured. So appropriate a disposition was eminently satisfactory. But Smith was never one to spoil the contemplation of a noble idea by haste. Why should time or place be permitted to interfere?

He grunted, therefore, arranged himself comfortably against the bundle, and drew from his pocket a flask of unusual size.

"Cheer-o," he said, and he drank a health to himself in celebration of his victory.

The bundle was softly comfortable. Smith wriggled his great shoulders to dispose of sundry protruding lumps to better advantage, and pondered with earnest importance over the captives of his prowess. Their uncalled for interference with his plans irritated him, and he grumbled petulantly to himself.

"Sanguinary niggers! I'll—bloomin' well shove 'em in a—bloomin' well. S'welp me, I will."

Smith's virtuous indignation grew with reflection. So ungentlemanly a meddling with his vast plans was unendurable, and his racing imagination launched itself into a pleasant contemplation of yet vaster plans for the utter immolation of the obtrusive three. His original quest and the appalling risk of his present situation drifted back into a dim insignificance before the absorbing contemplation of various fantastic forms of retribution.

It was only by the grace of the red gods of Shamgar, whose peculiar province it is to look after all true adventurers, that the whole thing had happened in the' most deserted part of the gardens. Smith's reminder of the stern necessities of life, therefore, was not through the searing agony of a long knife-blade under the ribs. But he was constrained none the less to leap suddenly into wide-eyed vigilance.

A stealthy scuffling in the branches above had disturbed him. He turned just in time to see a dim shape hang for a moment in black silhouette against the sky and then drop full thirty feet from a great limb to the ground and crouch facing him.

He was on his feet in an instant, with legs wide apart, evenly balanced in alert readiness for whatever might happen. The shape rose to its feet and advanced warily toward him.

It was about a foot shorter than Smith; but then again it was about a foot wider. It looked in the darkness like a horribly formidable antagonist. Smith quietly lowered one of his knotty arms and drew it back in preparation for an annihilating drive. Without a sign of fear, the shadowy figure shuffled nearer.

"Krik-krik-krr-ee-eek," it said in a high-pitched voice.

It was Smith who leaped back, five feet out of reach, and landed on the balls of his feet in his exact original defensive position. The burly shape advanced again, swinging a long arm just as Smith did, and chattering inquiringly at him.

Then Smith's tense breath escaped from him in a windy explosion, and his great bunched shoulder-muscles relaxed. He pointed a sudden finger at the huge bulk.

"I know who you are," he muttered accusingly. "You're a bloomin' 'carnation."

The figure reached out with astonishing length to take hold of the finger which pointed at him and krikked again.

"Yuss, you're a bloomin' 'carnation o' Hanuman, that's what you are. An' you're god of all the bloomin' monkeys in the world; and you got a shrine somewheres in 'ere."

The great ape chattered softly and snuggled nearer. It was obviously quite tame and entirely unafraid; since, quite apart from its vast strength, nobody would ever have dared to molest it on account of its extreme sanctity.

For Hanuman had long ago been elevated to the godhead in reward for his services in helping the great god, Rama, to get his wife, Sita, back from the hundred-eyed demon, Ravana, who had kidnaped her.

"Blimey, ain't 'e friendly?" muttered Smith, and as he felt the creature's huge, arms, "Golly, but I'm glad I ain't 'ad to fight 'im."

Then reminiscently, almost regretfully, "I ain't never 'ad a fight with a god—only with a coconut." And after a ruminating pause, with inspiration, "Nor I ain't neither ever 'ad a drink with a god!"

No sooner conceived than acted upon. Smith produced his abnormal flask and took a long draft.

"'Ere's to yer, Hanuman Ji." He wiped the bottle politely to make up for his rudeness in drinking first and handed it to the ape. "'Ave a nip yerself, old sport."

The great brute smelled at the bottle and then tilted it awkwardly to its mouth. It coughed and spat as the fiery stuff burned its throat, but it smacked its lips over the after aroma.

"Crickey, 'e done it!" murmured Smith in awe. "The beggar's human! 'Ere, don't swig the 'ole blarsted lot! 'Ere, gimme it!"

He rescued the flask from the big brute and stood in wondering cogitation of the unusual honor which had come to him in drinking with one of the most revered of the Hindu pantheon. Then a sublime and magnificent conception formed itself in his brain. He pointed a thick finger once more.

"Hanuman," he uttered solemnly, "you're a good sport. An' I'll tell you what: I'm goin' to make a offerin' to you. Yuss, that's what I'm goin' to do; a bloomin' offerin'. Three priests I got what I can't use—an' I'm goin' to give 'em to you. Now you show me your little private shrine 'ere an' I'll bring 'em right along. An' maybe you got a pole or something that I can use for a little job I got on hand."

The noble idea was worthy of Smith in his most exalted moments. He stooped to his great bundle of humans and up-ended it like a great roll of bedding. It wriggled slightly, but Smith only grunted. Then he turned his back to it, reaching behind over his head, squatted for an instant, and with a heave he hoisted the weight on to his wide shoulder and staggered to his feet.

"Come on," he grunted, and he stepped heavily out toward the central group of buildings. The ape shuffled and swung beside him.

In a Hindu temple there are always a number of niches and lesser shrines built into and out from the jutting angles of the outer wall. Smoky chirag lamps burned before most of these; but the danger of light never entered Smith's mind. Priests could be seen further out toward the main entrance, but round to the rear nobody paid any attention to the two dimly lit figures. Smith passed one or two minor shrines with scorn. Then a more pretentious one faced him. Before this was a little court paved with red bricks, and within, through the dimness loomed a grotesque idol. Smith was satisfied.

"Ho, I guess this is it," he grunted. "Any 'ow, it'll do." And he dumped his bundle to the pavement and rolled it in through the doorway. He stood in the entrance and stared emptily at the pot bellied deity.

"Funny lookin' duck. Arms an' legs like a blinkin' centipede. If I 'ad that a many I'd—"

Smith's cogitation was suddenly cut short by a howl of astonished rage. A group of priests in silent bare feet had come round the corner and stood looking at the desecration with fanatical horror.

Smith had long ago absorbed the axiom that the most efficient defense was offense. With an instant's glare to take in the situation he rushed at the crowd and essayed to crush them, all at once. In a second he was the center of a clawing, shouting maelstrom of whirling arms, legs, and robes.

The ape leaped up and down on all fours and whooped with excitement. Smith, with wide-spread legs, stood like a huge bear which the hounds were trying to pull down. Every now and then a mighty buffet of his got home, and there was one less priest to claw at him.

But more came running from around the corner and immediately added their yells and efforts to the original pack. The crowd in their clinging robes hampered one another; but presently a knife flickered in the smoky light, and then another.

Smith seized a lean priest of small stature by the neck and thrust him, choking this way and that as a shield, while he swung a right arm like a derrick-beam. Wherever it fell there fell also a priest. The mob surged against that defense like billows.

Then a man with a copper-bound lathi, or quarter staff, of bamboo forced his way to the center and swung at Smith. The hard-beset giant lifted his shield to the blow and crouched swiftly under it, and the man went down limp. Smith grabbed into the crowd for another shield, while the lathial struck again. This time the blow fell on the shoulder of the leaping ape.

From such as saw it a gasp of horror went up; and from Smith a shout of exhilaration. For in an instant he had an ally who was worth ten men.

With a coughing shriek of rage the great ape leaped out at the crowd, all tearing hands and clutching feet and frightful crushing jaws. Smith whooped with the creature and smashed a knotty bunch of knuckles at the chest of the man with the staff. The blow would have staved in a barrel. The man's knees crumpled and he went down clutching at two of his fellows.

Instantly Smith snatched at the staff and whirled it up with a shout. He held it in the middle in one immense hand, and plied both ends after the good old method of his far back ancestors. In a very few minutes he stood alone in the center of a respected circle, and stepped on groaning bodies as he fought forward.

A little distance off the frenzied ape, at whom none dared to strike back, was a clawing, shrieking demon of venom and fight, a swift-leaping menace to which none of the priests, fanatic though they were, cared to turn their backs.

In this Heaven-sent respite a gleam of sanity came to Smith. As usual he acted on it without a second's consideration. With a final shout he rushed at two priests who still faced him rather than the ape, bowled them over like ninepins, and then, shamelessly leaving the giant monkey to finish the fight into which he had led it, he turned and dashed off into the darkness.

The priests were so occupied with their ferocious god that the few who noted Smith's flight had no stomach for following that crazy Hercules into the darkness under the trees. Many minutes would have to elapse before an armed pursuit with lanterns could be organized. But of minutes Smith needed only a few for the work he had in hand.

Having acquired the pole, the lever which he had set out to get, his mind reverted inflexibly to the job he had come to accomplish.

It was hardly an effort for him to insert the heavy bamboo under the grating of the fair dancer's prison and to apply one of his massive shoulders to the other end. The whole grating tore its way out of the wall, bringing with it an avalanche of soft bricks and cement.

In a few seconds the girl was dragged through the jagged opening, squeaking with terror and pain. Smith bundled her in her voluminous garments, tucked her under one arm, and raced for the wall.

The faithful Poonoosawmi sat where he had been stationed, counting off urgent prayers to a long list of queer gods on his rosary beads and quaking at the sounds of strife which came from the direction of the light glow. He squealed joyously as the crunch of running feet came over the leaves and his master's form loomed in the shadow beneath him.

"'Ere, ketch 'old an' 'ang on!" panted Smith.

He spread his feet wide to get a good purchase, swung his bundle of cloth gently once or twice to get the heft of it, and then heaved it upward with all the strength of his great shoulders and loins.

Poonoosawmi on the coping grabbed and clutched at the billows of cloth and hung on desperately as he was bid; and in another second Smith himself sat astride the wall and lifted the bundle easily to his lap. In a few more moments their footsteps died away in the blessed sheltering darkness of the jungle.

IT was morning, seven o'clock, and the Hotel Oriental was thinking of getting up for breakfast. A closed match-box sort of native carriage rattled up to the door. A white man and a brown man and a heavily wrapped figure slipped out and hurried into the hotel.

The vaudeville man was, as usual, quite unmoved by the hurried entry of the three. Smith stood with feet apart like a colossus, and pointed with a magnificent gesture to the veiled loveliness.

"There's your Malka Devi. An' my tip to you is to grab 'er an' then take a train as fast as you knows 'ow—after 'andin' over five 'undred rupees."

The agent sprang up with an exclamation.

"By golly, you got her! Man, you're a genius! But say, hold on! I got to see her first, ain't I?"

The girl needed no persuading to show her beauty which had allured so many to this man who was going to take her to a land of affluence and freedom. Veils slipped from her like the famous dance of the seven; and presently she stood forth in all her glory—a middle-aged, rather stout, and dusky lady, of form and features which, while they suited the Oriental conception perfectly, could never have measured up to the standard of a Ziegfeld chorus.

The manager's face turned grayish, and he gasped.

"Gosh! Say, mister, did—are you sure you got the right one?"

"Sure? Suttinly! Arsk 'er yourself."

"Holy gee! Say, I'd—I'd expected a sort of a show-baby—broonette, of course; but with a good make-up I figured she'd—gee whillikens! But maybe she's got the fancy steps. Tell her to do a turn."

Smith translated. Nothing loath, she began to weave her arms in and out, and shuffled her feet and beat time with her anklets.

The manager sat down heavily.

"Holy Mike! It's the hootch! A coupla new shakes maybe; but it's the good old Coney Island cootchie dance. Gosh-a-mighty! Say, is that all there is to a temple dance?"

"No, sir," said Smith. "There's more to it—heaps more—if you ain't modest."

"Oh, golly no!" yapped the manager. "Say, mister, I can't handle this for a minute. Why, if I sprung that stuff on an American stage I'd be mobbed first and pinched after. No, sirree; this ain't what I figured on, and I call the deal off. You take her away, mister, I can't do anything with this act."

It was Smith's turn to sit down heavily. "Gawds!" he murmured. "This 'ere is a descent from the sublimey to the gorblimey!"

Poonoosawmi with keen business instinct chimed in:

"Sar, you don't wanting for pay five hundred rupees?"

"Five hundred rupees!" The manager, almost shrieked. "Say, I couldn't stage that for fifteen a week! No, sirree, the deal is off, I tell you. Why, I just hired a troupe of performing goats that's a better drawing-card. No, sir. You take her right away before her owners arrive and commence to carve up the landscape."

So cold-bloodedly irresponsible a repudiation was quite a shock. But then that is the way of vaudeville managers.

Smith was never a man to haggle. He rose majestically and strode from the room. Poonoosawmi followed with the wondering woman. The shock, however, after all the frightful risks he had taken, was sufficient to call for a bracer. Smith was never a man who hesitated over bracers. He took one—in proportion commensurate to the shock. The measure of the bracer showed how powerful the shock had really been.

Then Smith sat back in his long-armed cane chair to consider the problem. After staring into the void for some minutes, he propounded the question to his servant.

"Poonoosawmi, what're you goin' to do with the girl now you've got her?"

Poonoosawmi was quite unmoved by this sudden responsibility thrust upon him.

"I don't knowing, marshter. I think maybe putting in ticca gharry and telling drive like hell for temple."

"Poonoosawmi, you're a fool," said his master, nodding wisely and pointing the accusing finger. "She won't go; she was too bally pleased to get out."

"Then I am at losses," said the servant. "And speeding is needful, for this priest fellows soon coming and making bobbery."

"All right," quoth Smith with awesome seriousness. "You tell 'em to go to 'ell—an' you go, too." Came a long pause with closed eyes, then: "An' take 'er with you." The last was a dreamy murmur, and in the next instant Smith slept with the untroubled peacefulness of a child.

HE woke with his usual wide-eyed alertness. Two hours had passed, but there had been no cataclysm of battle and murder and sudden death. The boy stood exactly where he had been. The only difference was that the girl had gone, and a coarse gunny sack lay on the table.

Smith's eyes always took in everything in a flash—habit born of necessity.

"What's that there?" he demanded,

Poonoosawmi grinned all over.

"This, marshter, is rupees."

"What! 'As the geezer changed 'is blinkin' mind?"

"No, marshter, I taking woman like you tell."

Smith's vague recollection of his last orders was sufficient cause for mystification.

"Where? To—to 'ell?"

"Oah, no, marshter, how can? I take to one Armenian fellow in bazaar; one verree low fellow, marshter; he agent for matrimonial of Nawab of Dacca—that one Mohammedan swine, two-three dozen he got. Five hundred rupees price I sell, and agent is paying with leaps; temple trained female of muscular contortions is verree valuable, marshter."

For the first time in his life Smith was overcome with astonishment. He sat back, eyes closing and opening in spasmodic jerks.

"Strike—me—pink!" he muttered, "An' what'd she say?"

Poonoosawmi's grin went all the way round to the back of his head.

"She plentee tickling, marshter. She give me one ring for bakshish. Look see!"

And he lifted a dusty, horny foot and displayed a half-carat ruby shining from the grime of his middle toe.

"Gorblimey!" murmured Smith, and consciousness drifted softly from him, and he slept the sleep of the just.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.