THE pines bent and tossed—a broken square before the cruel onrush of the white battalions— the black boughs nodded and danced like plumes on a hearse, and down below, sagging behind the spent huskies, was—the coffin. At least, that was what Joe Pardon called it in his mind. To the crude, unimaginative eye it was a sledge. Still, a sledge can easily be a coffin when your provisions are all gone and your dogs are foundered, and you're off the map in bitter Ascaraland, with three feet of snow on the Divide and more to follow. It might be all very well to argue that you were only six leagues north of Fort Wolverine, which is by way of touching the skirts of civilisation, but the snow was as a white Atlantic lashed to fury, and—well, the coffin simile held good, and Joe and his partner, Happy Jack Hunston, knew it.

But for this bad luck, it would have been all right. They had not been blind to the risk, either, but they had to take it, as they had annexed the dogs and the sledge and the whole fit-out without the formality of asking the owner's permission. Wildcat Peter had wanted them badly up on the Lone Tree Bluffs, and Peter was notoriously impatient. Moreover, there was money in it, and they had none.

Thus! And now the snow was on them, and the game was up. It was horribly, bitterly cold—forty below zero despite the dampness of the snow—and bleak night was beginning to scowl over the edge of the pines. The big dog with the missing fang and one ear dropped and panted. He showed his yellow teeth in a snarl, and a throat hard and sanguine and black as death as Joe raised his whip. And Joe laughed bitterly.

The snow stung him like the thong in his mittened hand, the howl of the gale and the scream of the tossing pines roared in his ears like the thunder of some white, tortured Niagara. The other dogs had dropped as their leader had done; their fangs gleamed behind tongues that quivered and pulsated like strips uf red elastic.

"Well, they've done their bit," Joe muttered. "No use, old par'ner."

"No more use'n side-pockets to a toad," Hunston supplemented.

The end had come, and both of them knew it. In that stark programme there was the sporting chance of Death figuring as an extra turn. They might linger on for a day or two, but, if the grey, grim promise of the gale held good, it was merely a prolongation of the agony. There was only one world just then—a white one swept bare of food and fire, and they two were alone on the solar system.

"Sop me up with a bit of blotting-paper," Hunston said. "Wipe me out with a handful of waste. Noble redskin, we've torn it."

"Rock me to sleep, mother. Massa's in the cold, cold grave this time. Here, unhitch them dogs—we're a happy family now,"

All this without the semblance of a smile or the semblance of a fear. It was all in the game. Hunston cast off the dogs, and he and Pardon backed the sledge under a bank at the foot of a belt of pines. There were tools of sorts on the sledge—a pick or two and a couple of spades. It was good to be doing something in the way of action. The snow was piled high to windward; down there, in the deep trench, the keen edge of the wind was dulled, the white sharpshooters seemed to sting and burn and harry. A dead, dry pine gave all the wood the adventurers needed. A great fire blazed clear and dry. The dogs gathered round, the warmth from their steaming bodies was grateful— and unsavoury. They lay muzzle to the ground, their eyes alert and gleaming in amber flames as Happy Jack busied himself getting the evening meal. A haze hung over the cache, and mist sweated from dog and human.

It was hot and glowing waist-high there in the snowy pit, and freezing cold from the hips downwards. The gale screamed high overhead, handfuls of snow, like drift from a wind-lashed breaker, hissed and sizzled in the fire.

"They know all about it," Pardon growled. "Look at old Bully Bob! Mean to say he can't smell as we're in a tight place? And we don't want them forming a syndicate to corner the grub. We've got to bury them eatables—make a tunnel in the snow and bury 'em. Ain't goin' to be eaten by our own dogs, Jack."

"All the same, in the long run," Hunston said indifferently.

He tossed a fish each to the dogs. There was no fighting and snarling for them—each huskie took his own sedately. They knew. Pardon cursed them with a certain irritable affection as he filled the kettle with snow. He baked dampers, and made coffee, and fried the cast-iron bacon. There was just sufficient food left for thirty hours. Tobacco in plenty, but there was no jubilation in the knowledge. They were not unduly depressed, either. The fire glowed and crackled in amber and crocus-blue flames, the light rose and fell upon the stern faces of the two men. They were brown, hairy faces, with steadfast eyes and obstinate jaws. There was no money between them, and food for perhaps five more meals. Hunston sat with his face in his hands, sucking fiercely at his pipe.

"Jack, I've been thinking," Pardon said suddenly.

"Always gives me a headache," Hunston responded. "Never could do anything except with my hands. An' what's the good?"

"Oh, I dunno! I feels like that occasionally. I did a goodish bit of thinking when I quit the Old Country eight years ago, and turned the farm over to Mary. She was happy enough, but I couldn't settle down to it. Something in my blood, I suppose. Used to do a bit of poachin' to save taking to drink. Couldn't even stop when the kid was born. Wish I had now."

"Same here," Hunston said quite biographically, "only mine was market gardening. Fightin' bankruptcy all the time, with my heart in my mouth. Used to make me sweat and tremble—me as don't know what physical fear is. That's why I came out here to make a fortune for me and Lizzie."

Pardon spat savagely into the red heart of the fire.

"And you've done it," he cried—"you and me done it together! Over two hundred thousand dollars apiece. We was cheated out of the Simple Anne Mine by them cursed lawyers of Jim Clint's—though we didn't know as they were working for Clint at the time—and we was properly sold over those claims at Grey Reef. And all them hard-earned dollars found their way back into Clint's pocket, confound him!"

"What's it all matter now?" Hunston asked philosophically. "You'll never see Mary nor the kid, and Lizzie will have to find somebody else. Our number's up, Joe! That old vixen, Dame Nature, has caught us short, and we've got to pay. 'Bout two days more, and we'll toss for it who does the shootin' of the other when the grub's petered out. Only two shots are necessary, old pard, and I hope to Heaven as the man behind the gun won't be me!"

His big, strong voice shook as he spoke, though the twinkle in his flint-blue eye was still there. Pardon nodded solemnly. It was maddening to think that they were only fifteen miles from life and safety. Why, from the bluff behind the camp, they could see the lights of Fort Wolverine!

"And there he sits and fills his pockets!" Pardon cried with a sudden fury. "If he'd played the game by us, we shouldn't be here. We should be snug by the fireside in the Old Country, and you'd have your lass and I should have mine. Ever been inside Jim Clint's house? No? Well, I have. It's like what you read of in them penny novelettes— wallowin' in luxury. With a private telephone wire—seventy miles of it—to Weston City, and an operator at the far end to connect him with the long-distance lines as far as New York, he knows what the world's doing every morning before breakfast. That's how he's got the whole of the State in the hollow of his hand. That's how he diddled us and scores of honest men besides. A private line underground. Cost him a couple of hundred thousand dollars. To think of him sitting in that big house "

"Then don't think of him sitting in that big house." Hunston smiled. "Who told you all about the 'phone?"

"Found it out for myself. I'm up to all that. I learnt all about field telephones the year I was in Orange River Colony along of the Imperial Horse. I laid miles of it, and sent hundreds of messages. It isn't a bad game, take it one way and another. But that's all done with. Here, come and give us a hand with the grub before I'm too sleepy to handle it. We've got to make a tunnel in the snow, or the dogs will have the lot."

The ground was soft enough; the picks bit in it, and the shovels cleared the loose earth away. Hunston's pick struck something hard a glancing blow, and jarred him to the shoulder. He stooped down curiously.

"Didn't know as there was ironstone in these parts," he said. "Anyway, it's metal, all right. Looks like something buried here, Joe. Come and have a squint at what I have found."

Pardon complied indifferently enough. He was working mechanically, his eyes half closed. With the aid of a match, he could see in the bottom of the pit a shining spark of metal where the glancing pick had taken the rind off it. He bared his hand and touched the gleaming wound tenderly. His fingers slid around it. Then the sleep was wiped from his eyes as if a sponge had been passed over them. He was trembling from head to foot, under the brown varnish of tan the skin grey—ashy grey. For a moment the colour faded from his lips.

"I don't like—I don't like," he gasped, "to—to Besides, I ain't sure. Dump in the grub and fill up the mouth of the cave again. I ain't feeling none too well, pard. So we'll have a look at this yer thing in the mornin'. Not as any metal's much use to us. Jack. If it was a barrel of flour now, one might drop a grateful tear over it."

Hunston yawned sleepily. Pardon's agitation had entirely escaped him. He was dead tired—the roar of the gale was like drowsy music in his ears. He dropped down by the side of the fire and knocked out his pipe.

"Good night, old pardy," he droned. "When a man's asleep, he's as good as any other man, even if his blessed life isn't worth—"

A snore cut the philosophy short. But there was no sleep in Pardon's eyes. He was numb with fatigue, soaked through and through with the conflict of the day, but his brain was working at fever heat. From an inside pocket he took a section map and laid it by the side of the fire. For a long time he studied the chart with eager, burning eyes. From the same pocket he fished out a stump of pencil, and made laborious calculations on the margin of the map. He proved them again and again until he was satisfied that he had made no mistake. His pipe had long since gone out, but he sucked at it mechanically. He did not hear the roaring of the wind or the hiss of the snow on the fire, the whimper of the dogs in their dreams, or the scream of the tossing pine branches. He cared nothing for these things, because it seemed to him, in his simple wisdom, that he had found a way out.

He came to himself presently, after an uneasy sleep of an hour or two—came back to grey, dim daylight, with a sky of lead overhead and the black pines volleying in the gale. For the moment the snow had ceased, as if Nature had spent herself in one furious white orgy, but the menace was in the sky still, and there was more to come.

"Breakfast all ready," Jack said cheerfully. "Didn't want to disturb you. Just take that bacon off the fire, pard."

But never a word spoke Pardon. All through the meal he sat with a certain brooding sullenness, his eyes fixed on the fire. Before the provisions were hidden away again, he spent ten minutes and half a box of matches in an examination of the shining metal disc that Hunston had accidentally discovered. His lips muttered something, his eyes grew bright.

"Just you put the provender away," he said, in the same moody fashion. "I'm going to make a bit of an experiment. No, I ain't gone dotty, and I ain't goin' to say anything till I know. Give me a pick."

Hunston handed over the pick wonderingly. He had seen Pardon in this mood once or twice before, and generally on the eve of some great discovery. Therefore Pardon should have his own way and no questions asked. He would say what he had to say all in his own good time.

Pardon climbed over the ridge with the pick in his hand. The fierce rush of the gale brought him up all standing. He stood there repeating a formula which he had got by heart. Along the hollow gut the wind had swept the ground clear, piling it up in great white walls on either side. From Pardon's point of view, a vast amount of trouble was going to be saved. But he was not taking any risks on that account. He passed backwards and forwards over the narrow valley, tapping the ground with his pick at every stride. With grim tenacity and doggedness of purpose, the strange pastime went on for a good hour or more. Then the pick rang on something hard and brittle, and Pardon's lips parted with a smile.

"Got it," he muttered—"got it for a million, sure!"

He stooped down and proceeded to clear earth and refuse away. There stood disclosed presently a square iron grating fitted into a trap of the same metal. It looked strangely modern and civilised and out of place in the desolate white desert. With the point of his pick Pardon raised the grating and peered inside. The grim expression of his face expanded into an all-absorbing grin.

"No mistake about it," he said. "I knew I was right. It's a darned lucky thing as the wind skimmed the snow off here so nicely, and it's a darned lucky thing as I struck what I wanted within half a mile. Half a mile! As if a half mile here isn't equal to half a dozen leagues down below on the plains! Question is, can I do it?"

Hunston lounged over the fire, smoking placidly.

"Caught any fish with that there rod of yours?" he asked.

"Got the biggest fish this side of the Divide," Pardon explained curtly. "He's on the line, and he can't get off. But it's a long line as he's got out; I should say as there's quite five miles of it. But he's fixed there and he can't get away, and all we need is a landing-net."

"Oh, ask me an easy one," Hunston said impatiently. "Give it me with the bark on."

"I am," Pardon responded. "The landing-net's at Four Forks, and that's a good five miles away. I figured it out on the map when you was asleep last night. Worked it all out, I did, till I could hardly see the figures. If we can get the landing-net, we've got the fish sure, and he's big enough to keep us all our lives, old pard. But the question is, how can we get to Four Forks and back? That's the big trouble. It's a hundred to one against getting there, and a million to one against getting back. But the million to one shot comes off sometimes, or there's no basis for the theory of chances. (That ain't my own—I read it in a book.) At any rate, I'm going to try."

"You can count me in, of course, pardy."

"No, I ain't counting you in," Pardon said doggedly. "You've got to stay right here and wait. What's the good of two of us going? Besides, if I don't come back, you'll have food for another day or two, and Heaven knows what may happen in that time—rescue parties and all manner of games."

"Where you go, pardy, I go, and that takes it."

"Then I stay where I am, old son. I tell you it's a chance. But I ain't going to talk about it, for fear of disappointment. And I can't see no point in the two of us going to Four Forks. Is it a deal?"

Very reluctantly on Hunston's part it was. What Pardon needed from the locality in question he did not say, neither did Hunston press for information. If this desperate thing had to be done, then it had to be done quickly. Pardon might get there, and, on the other hand, he might have to turn back. He might find himself up to his neck in a snowdrift, and then—why, then neither man cared to think of it. There was no occasion to dwell upon the danger and the outrageous folly of it. But there was no way out but this. It was infinitely better than the certainty of slow starvation.

So Hunston helped to harness the dogs and pack a sufficiency of food for them and Pardon to last for a day at least. If Pardon was not back by nightfall, then it was inevitable that he would not return at all. It was characteristic of those two bosom friends that they did not even shake hands at parting. Hunston stood on the edge of the ridge and raised a cheer as the dogs pulled westward. They vanished presently behind a belt of pines, for so far the track was good. And Pardon knew the way blindfold. The white battalions were the foe. If they proved kind, then this mad thing might be done.

With set teeth and bent head, Pardon pushed on doggedly. The snow lay deep and thick in places; here and there it had to be skirted, so that each mile was more like five. Pardon was grateful now and then for the sun peeping out of the racing, reeling cloud-wrack, for it gave him his line when more than once he might have wandered away from the track. And the sun had already begun to slide down before he reached Broke Hill Point, that only represented half the journey. He was fiercely, ravenously hungry now—so hungry that the pain of it forced the tears to his eyes—but he dared not stop. A grey shadow slid along, from time to time, under the cover of the pines, and the dogs grew restive. Pardon repressed a shudder. The wolves were stalking him—they were backing their instinct against his adventure.

It was long after dark before he staggered against the huge boulders of rock and precipice that formed the front of Four Forks. The dogs dropped down panting and spent, snarling and worrying at one another's quarters. They were quite out of hand now. The leader turned his glittering fangs on Pardon as he stumbled arud lay exhausted across the sledge. With an effort, he struggled to his feet and laid about him with his whip. He was fighting, with the grim tenacity of despair, for his life, and he knew it. By a kind of instinct, as a man in a dream, he threw food to the dogs. He lay in the snow, face down at their feet, lost to the world; but not for long. Here was the door of a hut built into the solid cliff—a door that yielded to a few blows of Pardon's pick. There was nothing but stores here, and neat boxes of tools, one of which Pardon regarded with sparkling eyes. On the floor, too, there was a half-filled jar of whisky. He was a temperate man, was Pardon, but his fingers crooked convulsively round the handle of the demijohn as if they had been palsied by drink. Here was the stuff he needed, and the occasion that Providence made it for. The fiery stuff put fresh life and vigour in his veins, a certain recklessness gripped him. He fed the dogs generously on the floor of the hut; he grudged them the fish as he tossed it to the snarling brutes. His own meal was frugal enough, but the huskies must have their fill.

There was wood in the stove, and soon the fire roared loudly. There was a warmth presently that Pardon had not known for days. Outside, the gale howled and raged, but no more noisily than the red-hot stove. And Pardon's fresh courage spurred him to nervous things. He would lie down and rest for an hour or two, and then press back. There would be a moon presently; to get back along his own trail would be less difficult. He lay with his back to the blaze and slept like a log. He woke with a start and dragged himself to his feet. The sooner this thing was begun, the sooner it would be ended. He fought his way into the bitter cold; he drove the tired, sullen dogs before him. All he had to do now was to pack the whisky and precious case of mahogany, and he was ready. He began to realise how spent and weary he was. Better have stayed the night in the hut. He woke from a walking dream to find the dogs restless and uneasy. He saw the grey shadows skulking in the fringe of the woods; under the pines were a score or two of fierce, rolling amber eyes. The big flea-bitten wolf in the van of the pack put up his head and howled. Pardon was conscious of a curious tightening of the muscles of his throat. Then one of the dogs rolled over, done to the world, and the amber circle of eyes grew narrower.

"Sorry, old man," Pardon gritted between his teeth. "This is what them philosophy chaps call the survival of the fittest. Greatest good of the greatest number, my boy. Still, I'm darned sorry, old dog."

He cut the spent huskie clear of the traces. The dog whined pitifully, and Pardon shut his ears. He did not dare to look back; he tried not to hear the snarls and yells, the worry of the teeth in flesh, the last snarling agony. He badly wanted to have Jim Clint by the throat at that moment. Still, the circle of shifting amber eyes was gone for the moment.

They would be back again presently, of course, and they were. Pardon could see the leaders with the red foam on their jaws. He could not spare another dog so long as there was an ounce of pull left in him. Each dog wasted was a step nearer to the grave. Better a couple of revolver shots. They were good shots and true. Out of nowhere a great mass of fur and fangs and yapping jaws came. Pardon glanced back at the howling mass with, grim pleasure, and the rest was a dream. The camp was in sight with the dawn. There was one dog left of the team, and the sledge was lying on its side. A few yards more, and the situation was saved. Yet Pardon could not move another yard. It seemed to him that he was fast asleep, bound by thongs to the ground. If he could only burst the frozen bonds of speech and make Jack hear! The world was full of grateful warmth, something hot and stimulating was trickling down his throat. He sat up presently, sniffing hungrily at the hot coffee and bacon that Hunston had prepared for him.

"Had your breakfast, too?" he asked.

"Had it more than an hour ago," Hunston lied cheerfully.

"You're the biggest liar this side of the Pacific!" Pardon retorted courteously. "I'm having your breakfast."

"Well, what's it matter, pardy? You're back here, anyway, and, as the chap said in the story, your need is greater than mine. And you're safe back, old man, and that's worth a score of breakfasts. Guess you found what you wanted, too, or you wouldn't have annexed that whisky. Anyway, the grub's all gone, and it's up to you now to see us through."

"We'll have all the forage we need before night," Pardon said grimly. "Here, hand me over that case and follow me. It isn't far, and there's no time to be lost. There's safety and fortune in that little box."

Hunston followed wonderingly. Outside, in the snow-swept gully. Pardon paused and pulled up the square iron trap. He hauled at what looked like an indiarubber snake. With a pair of pliers from the mahogany box, he cut the rope and proceeded to attach some quaint-looking instrument also from the case.

"What the tarnation snakes is all that?" Hunston demanded. "And how did it get there? Didn't know as they'd got gas and water in these parts."

"You'll understand presently," Pardon muttered. "Hullo! Hullo! Is that 1, Fort Wolverine? Good! Oh, yes! We're Wood and Garton, of the Second Section Telephone Survey. Out looking for faults. I'm calling from Inspection Box 13, on Mr. Clint's private line. Eh? No, the line is all right. It's us chaps who are all wrong. We got caught short in the blizzard. Lost all our dogs and provisions. Held up near Four Forks. If you'll listen carefully, I'll locate our position exactly... Got all that? Good! Bring a coil of wire with you and a magneto from Saxeby's, as there's a leak just here, and if it isn't put right, old man Clint will find Wall Street a little bit deaf next time he calls up. And, say, bring blankets and some brandy for a poor chap here who is fair off his rocker. Johnny called Carston. Picked him up half dead, with his pockets full of quartz, good forty ounces to the ton stuff. What? That's it—he's found the broken lead of the old Grey Goose Mine. If we can save him, there's millions in it. Only don't tell old man Clint, or he'll do us for sure. Oh, yes, you'll find our trail. We lit out of Wolverine three days ago by Poplar Greek. And we're clean out of food. You ought to get us by nightfall easy."

Hunston stood listening wonderingly. He was slowly getting the hang of it. The gash in the snake was repaired presently and the iron cover replaced. Back by the fireside. Pardon began to explain.

"You struck it first," he said. "That metal disc you hit with your pick was Glint's private telephone wire. Right here in the forest, with snow piled up around us and death staring us in the face, you hit it. And then I knew that we were saved—if I could get to Four Forks, where the Telephone Company keep spare stores. I thought it all out as you. lay asleep. And I got to Four Forks, and I got the spare battery, and I got back. Sounds like a dream, don't it? Here are we starved and hungry and nigh to death, and yet, if I like, I can sit down and talk stocks and shares to Wall Street—can hear the clocks striking on Broadway and the wolves howling for our blood at the same time. And we're saved, old pard, and the knowledge what I gained in South Africa has been our salvation. They'll be here to-night with dogs and sledges and food for a regiment."

"I'll get it all presently," Hunston gasped. "You're a wily bird, Joe. Pretty little touch of yours 'bout the chap with his pocket full of rocks. Thought that would fetch 'em all the quicker, maybe?"

Pardon chuckled as he filled his pipe.

"It's deeper than that, as you'll see presently," he grinned. "Didn't I say as there was safety and fortune in this for us? And so there will be. Wake me when the relief comes. I'd like to sleep till then."

It was far into the night before the relief came. Pardon sat up and pricked his ears. He looked out across the snow to the long sledge, with the double team of dogs and the giant of a man who was urging them on.

He chuckled and bared his teeth in a hard, savage grin.

"Chuck some wood on the fire," he whispered. "Get a blaze. It's all panned out exactly as I had expected. He's come alone!"

"Who's come alone?"

"Why, Clint! I knew he would. Probably got another sledge a mile or two away, with instructions to await orders. It was the story of the gold find that fetched him. You see, it was Clint I was talking to on the telephone this morning. I recognised his voice, though he wouldn't, of course, remember mine. And he had no suspicions— how could he? The suggestion not to say anything to old man Clint fixed it. He wouldn't care a curse off a common for us, and that's why I hinted at a fault in the line. It's 'Carston' he's after. Now, then, get out your gun."

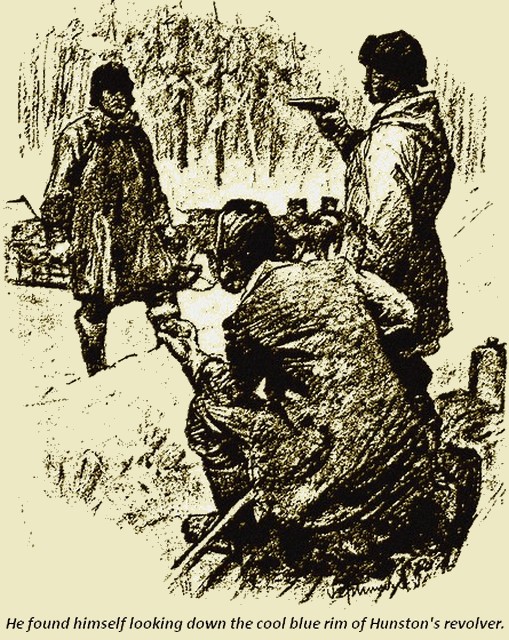

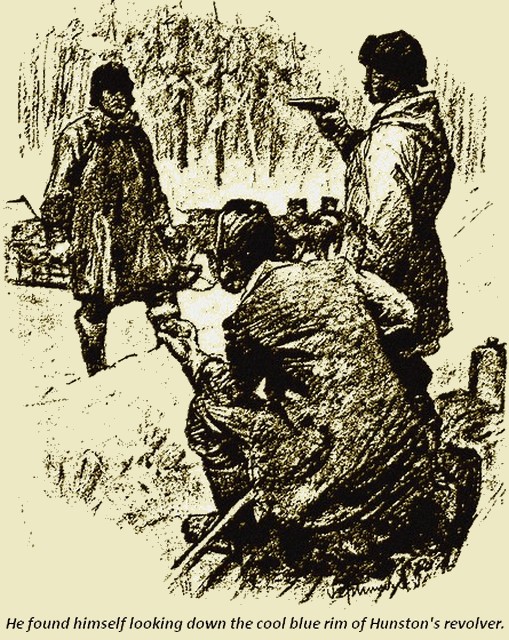

Clint strode into the camp, big and strong, hard as iron and merciless as ice. He found himself looking down the cool blue rim of Hunston's revolver.

"Evening, Clint," Pardon said cheerfully. "Pretty good of you to come like this."

"Pardon and Hunston," Clint stammered. "Why the—"

"Don't swear," Pardon grinned. "No use, James. I found your wire and I tapped it. Learnt that game in the Boer War. And if you've come to see 'Carston'—why, I might as well tell you as there ain't no Carston. I knew that I was talking to you this morning, and I put it up to you. We'll take all those provisions and those dogs, and we'll stay here till the frost comes, and then make our way to Milton City."

Clint foiced a laugh from his great chest.

"The joke is on me, boys," he said.

"There's more of it to come," Pardon went on gravely. "You're a great man, James, and you've got imagination as well as grit; and you've got all this part in the hollow of your hand. And you've got a pile of dollars that rightly belong to us. There are others, too, who've suffered. If we were to shoot and bury you, the State wouldn't shed a tear. We're going to have those dollars back, James—two hundred thousand of 'em. Guess you told your cashier man, before you came, that you were gunning 'Carston.' But for 'Carston,' you wouldn't have come yourself. So consider yourself our prisoner, James, unless you like to do the fair thing. Back on the track are others waiting for you. Now, you're going to write a note to your cashier, asking him to put in a cheque and send you two hundred thousand dollars in gold. I'll take that letter to those waiting for you on the last stage, and bring back the money. And if you play any game on us, we'll drill you full of lead, James."

Clint's face darkened as he produced his note-book.

"I'll do it," he said. "I guess I must. But it'll do you no good. I'll hunt you down; I'll put the State on you. The money is only borrowed. Here, will that satisfy vou?"

Pardon smiled as he read the order.

"Guess so," he said. "And pard and self ain't afraid, because you'll do nothing, James. You'd be the laughing-stock of the State, and you wouldn't like that. You'd find silence cheap at the price. Oh, yes, I am going to bind your hands and feet—I'm taking no risks. I'll just pop along to the other sledge and set the letter going. Then I'll come back, and we'll have a nice sociable meal together. So take it smiling, James, for you have been bested for once in your life, and don't you forget it."