RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

BETH drew a sobbing breath or two, and dropped casually upon the edge of the kerbstone. The skin was hard and tight upon her cheekbones, there was a flinty gleam in her blue-grey eyes. It was characteristic of the girl and her tribe that no plaint escaped her; the little, red mouth was hard and rigid and defiant, for she was up against the world, and had tasted no food since the previous morning.

She swung her ragged legs backwards and forwards nonchalantly; she was a mass of tatters, a child of the pavement—a gutter-snipe, if you like—with her hand against all men and all men's hands against her. Just one of the waifs and strays of derelict humanity that strew the streets of our worst slums—hard, defiant, Godless, with just education enough to know that the social system was all wrong and that honesty is a shibboleth in the mouths of Scripture-readers and district visitors.

In years Beth admitted to sixteen. Take her away, purge her with hyssop, wash her and dress her, and Beth would have been an undeniably pretty girl. Feed and tame her, wipe that wolfish look and that hard scowl from her eyes, and outwardly at least she would have been as dainty and winsome as an English child can be.

But then, you see, for the last seven years she had literally scavenged her living from the unsavoury streets, and she had only been saved from worse than starvation by that fierce, tigress virginity which is the animal attribute of the female wild animal all the world over. The boys could knock Beth about—indeed, she carried many a scar—but that was all in the natural order of things. The time would come no doubt when this wiry lioness cub would meet her mate, and follow him, much as the woman in the days of the cavemen trotted obediently after the superior animal when he had effectually tamed her with a club.

Beth had a good chum, all the same. She sat there in the harsh, blinding sunshine with the light gleaming on her red-gold hair and strangely perfect teeth. For the moment her philosophy was narrowed down to the point when physical necessity overrides every other consideration. She turned quite fiercely to the boy by her side. He was as ragged and grimy as herself, he had the same wolfish gleam in his eyes, the same taut lips, the same suggestion of the midnight animal prowling for food.

Bill Dockett was thin and brown and wiry, a little small for his eighteen years, and with a suggestion of the Eastern in his dark, intelligent eyes. He would never be a big man, but one could imagine him, when properly nourished, as a pioneer. He unconsciously suggested forced marches through tropical forests and daring dashes across the blinding, sandy deserts. He was a boy who would most infallibly have got there, given his chance. He was waiting for his chance now. He sat there huddled up, his eyes shaded from the glare, watching two men on the other side of the road in close conversation.

"Oh, shut up, carn't yer!" he snarled. "Don't yer see I'm a-listening? Shut yer bloomin' 'ead!"

Beth stopped her lurid complainings obediently. As in the jungle, it was the duty of the male cub to find the food for his mate. Nevertheless, he knew that the female would not remain with him an hour should another he-cub come along with the prey in his mouth, so to speak.

And this was where Beth had all the best of the bargain. She knew, without being told, that the lad loved her with a blind devotion, and that all he had to give he gave, without expectation of fee or reward. He knew that Beth jeered at him, he knew that she would leave him for days at a time when he had come off second-best in a pitched battle with other derelicts, and in some vague, indefinite way he knew that she was merely obeying the female instincts of the jungle. But some day the cub would grow into a lion, some day the day of reckoning would come; and Beth was uneasily conscious of this, too.

"Lor', I ain't 'ungry, not 'arf'" she said.

There was no note of complaint in this; it was merely a cold statement of fact. Bill nodded sympathetically.

"You just stay there," he said. "Strike me perishin' blind if I don't begin to see a chanst of a bloomin' tanner! See that bloke in the grey trahsers? Copper in plain clothes. I seen 'im afore. An don't you move. If Tim Malone comes erlong, tell 'im to go to blazes. Leastwise, if 'e ain't got no posh on 'im."

"If 'e 'as, you can go to blazes," Beth said promptly.

Bill accepted the suggestion philosophically. After all, Beth was sticking strictly to the rules of the game. Bill shuffled across the road and whined before the two men standing there, in the best professional manner. They ordered him away with an oath, and he accepted his dismissal with a sob which would have done credit to Chevalier. But his quick ear had caught all he wanted to know. He drifted lazily across the road again to the pathetic little figure sitting patiently on the kerbstone. His eyes were sparkling now, and the half-snarl had gone from his lips. Beth looked up eagerly.

"Wot cheer, cully?" she asked.

"Righto!" Bill said. "It's right as rain. You come erlong with me, an you'll see some fun. When you're up against it good an 'ard, you 'ave your little bit on Bill Dockett. Blimme, if it ain't easy enough to mike the splosh if you keep your eyes open. Gimme a charnst, an I'd roll it up with the best on 'em. Only gimme a charnst, I say. But we don't never get none down our way. We're nothin' but a loter dogs, we are."

Thus spoke the embryonic Socialist in rags. The lad had never had his chance, and probably never would. It was just the smattering of intermittent Board-school education which stirred these feelings in his breast. But Beth was in no mood for a dissertation on political economy. She wanted to see the prey, so to speak, dripping in the mouth of the he-cub.

"Whatter 'bout them tanners?" she asked practically.

"Almost forgot 'em, I 'ad. Now you just come erlong with me. We're goin' as far as the Bay 'Orse."

"Champaigne or port?" Beth suggested sarcastically.

"It ain't goin' to be neither. It's just a perishin bob. If I'm lucky, perhaps two."

Bill swung back the glass doors of the public-house jauntily and swaggered in. He would have entered Buckingham Palace with the same absolute assurance. Beth followed a little more slowly and suspiciously, as if she scented a trap. A dozen or more men were sitting in the bar drinking, and their conversation snapped off abruptly as the two ragged waifs entered. A surly barman turned, with a blistering oath, and ordered Bill out. He spat contemptuously on the sawdust, and refused to move until he had had speech with the landlord. The barman strode across the floor and dealt him a staggering blow. As Bill rose to his feet, a tiny spurt of blood trickled down his cheek. The savage onslaught might have been no more than a flick, for all the fear he showed.

"You're a fool, my lad!" he said. "I come 'ere to save your ole man a 'undred quid, and you be'ives like this. As if I didn't know what I was torkin' abaht! Dunno a copper's nark when I sees 'im—not 'arf! An', if you arsks me what these blokes are a-doin' 'ere—"

"They're drinkin' of their beer," the barman growled.

"Yus, an' waitin' for Nosey Philips to come erlong an collect the bettin'-slips. Now, young feller-me-lad, trot out the guv'ner quick, before it's too late!"

He stood there, with his hands thrust in the pockets of his ragged trousers, with the air of one who is master of the situation. The thick-witted barman began to comprehend. He dived into a dark den at the back of the bar and produced an obese, hook-nosed man in a preposterously dirty shirt, with a preposterously big diamond in it. He beckoned Bill into a corner of the bar, and asked him what he wanted.

"'Arf a dollar," Bill said huskily. "There's Ginger Palmer outside. An 'e's bloomin' well watchin' your 'ouse. I 'eard wot 'e said to the other cove. I seen 'im givin' evidence in a bettin' caise afore. An' directly Nosey Philips 'ops erlong, they nobbles you. An if this 'ere information ain't worth 'arf-a-dollar, then I don't know what is."

The landlord plunged his hand in his pocket and produced a handful of silver coins. There were half-crowns as well as florins, and after a slight mental struggle the landlord handed over one of the former.

The landlord plunged his hand in his pocket

and produced a handful of silver coins.

"Bit of a temptation, wasn't it?" Bill grinned. "Still, yer gratitood's worth the extry tanner. I've sived you a 'undred quid, if I've sived you a penny."

With this, Bill marched out of the bar, holding the half-crown tightly in his grimy fist. Beth's eyes were gleaming again now; the tight, hard look had come back to her mouth. The lioness cub was wondering what prey her male mate had assimilated.

"Wot 'ave you done?" she whispered, in a voice hoarse with hunger. "What did you mike, Bill? 'Ow much did 'e give yer, an' why should 'e part with it! Solly ain't no school-treat."

"'Arf-a-crown," Bill said proudly. "I give 'im the office. Savvy.' The copper's narks is watchin the Bay 'Orse, 'cos there's bettin' goin' on there, see? That wos wot those two blokes was torkin' abaht acrost the street just nah. I 'eard 'em. An' one on 'em's Ginger Palmer, wot I oncst saw in a police-court givin' evidence in a bettin' caise. When I see's 'im acrost the road, thinks I, 'E ain't up to no good. Keepin' 'is eye on one o' the pubs, sure. Then I 'eard the Bay 'Orse mentioned, and I was fair on to it, ducky. I knowed Solly would be good for 'arf-a-dollar, an 'ere it is."

"You are a clever one," Beth said admiringly. "'Ow do you manage it, Bill? I. could never 'ave done that."

"Course you couldn't," Bill said patronisingly. "It's brines—just brines, my gel. One night on Tower 'Ill, I 'eard one on 'em Socialist blokes siy as knowledge was power. An' that sorter stuck in my mind. I tries never to ferget a fice, an' to remember everything I 'ears, an' many a bob it's put in my wiy. Now come erlong, an' lets 'ave sixpenn'orth an' chips. An' we'll spend the extra tanner as Solly didn't mean ter gimme on a quart o' beer. That ain't extravagance—it's perlitical erconomy."

"Where do you get them words from, Bill?"

Bill replied, with an air of superiority, that he knew a sight more than Beth gave him credit for. And, in sooth, he possessed a wider fund of information than most of his class. He was fond of promiscuous reading, and nothing in the way of print came amiss to him. He could hang over a penny bookstall on a Whitechapel pavement and forget his hunger for hours together.

He had a strange bent for mechanics. He was seldom or ever in the neighbourhood of a motor-car, and yet he had an almost intimate knowledge of the component parts thereof. He could see machinery as most people see a picture or a landscape.

He was saying something of this in the proud exuberance of the moment when a tall, hulking figure loomed from an archway and stood before them. The new-comer had a big frame which indicated strength, allied with the weakness which goes with the want of proper food. Nevertheless, Hopper Hames was a terror in the neighbourhood, and most small capitalists, in moments when funds were high, gave him a wide berth. He had the eager, foxy eye of all of them; he divined with a sort of vulpine instinct that there was food in the air. Those two would not have been hurrying along otherwise.

"What oh!" he said defiantly. "Where goin', cully "

"Dinner!" Beth screamed, with eager eyes. "Bill's nicked 'arf-a-dollar!"

The other lion cub stood in the path now, and the first one, with his instincts aroused, showed his teeth in a snarl. He knew exactly what was coming. Hazily in his mind he had decided to ask Hopper to join the feast. But there was no longer any question of that. The bigger brute opposite had been prowling about the jungle all day in search of food, and no nice ethics of morality troubled him. His thick lips quivered like those of a cat when she is about to pounce upon a bird. Hopper meant to have that half-crown, and he had not the slightest intention of making the transfer according to the strict rules of diplomacy.

It would be quite useless to appeal to the other animals lying hidden in the steaming jungle. If they came out, there would be a free fight for the prey all round. And there was no policeman in sight, either; indeed, if there had been, it would have been little use to appeal to him. His mission in life was to move on the inhabitants of the jungle, and see that the fight did not last too long. Bill stepped back, with a snarling oath.

"No, you don't!" he said. "There's two of us. An Beth can fight like any bloke when 'er blood's up!"

But Beth showed no sign of fight. She looked from one to the other with a certain feline timidity. She was very, very hungry, and she was acting on the instincts of the jungle. It would never do for her to take sides, for as yet there was some uncertainness as to which way the victory would go. In any case, she would get her meal; she would trot obediently behind the victor, as the lioness always does, and always has, since the jungle first began.

"You won't let me dahn, 'Opper?" she pleaded.

"Oh, you shall 'ave yer bit," Hopper said magnanamously. "Nah them, Bill, 'and it over!"

Bill's defiance rang out loud and clear. It was not time to analyse the situation, no time to muse upon the perfidy of the weaker sex. All that would come later, when the fight was over, and the loser lay down to lick his wounds.

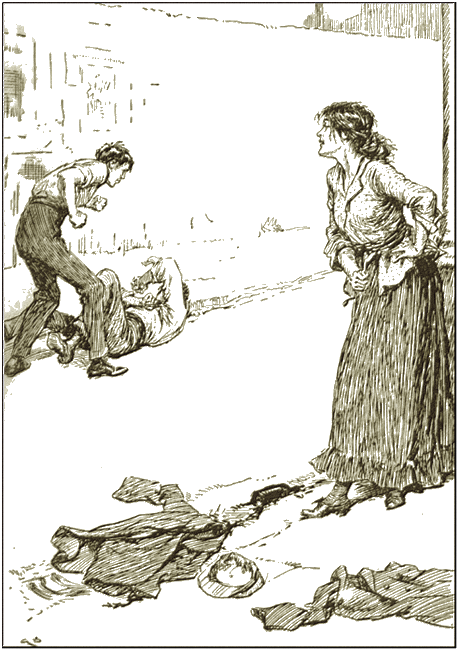

It was a cruel, merciless, and one-sided fight from the first. The forlorn hope did his little best, but presently Bill lay sick and dazed and bleeding on the pavement, with Hopper kneeling on his chest. Other wild beasts had crept out to watch the fray, watch it in tense silence with eager, cruel, hungry eyes. But nobody interfered—the unwritten law of the jungle kept them quiet. With that terrible pressure on his chest, Bill lapsed into a quiet, dreamy unconsciousness, and when the mist cleared away from his eyes Hopper stood over him, with the half-crown in his hand. He grinned in an ugly fashion.

"Want any more?" he gasped.

"'Ad some," Bill said laconically.

Vae victis! The expression would have conveyed nothing to Bill, but it came practically to the same thing. It was his Spartan way of acknowledging defeat. Hopper turned away, at the same time time jerking a contemptuous thumb in Beth's direction.

"Comin' erlong with me?" he asked.

"Wot do you tike me for?" Beth screamed shrilly. "So-long, Bill. See you ter-morrer."

Bill made no reply. He had to go away and lick his wounds. He uttered no complaint; he was as utterly indifferent as any mere spectator of the fray might have been. The Fates had been against him, and there was an end of the matter.

He crept away into one of the foul alleys leading from the street, and lay down in a patch of sunshine absolutely alone in the world. Then, as calmly as if nothing had happened, he took from his pocket a copy of an engineering paper, obtained from goodness knows where, and began to read.

It was late in the afternoon before he strolled as far as the docks, where he managed to pick up a copper or two, and get into conversation with a man there who was driving his own car. He was a brown-faced man, with a sunny outlook, and he had travelled in many lands. The kindly eyes with the gleam of humour in them were turned upon Bill, with a human interest that almost dazed him.

It was perhaps the first time in his life that he had ever been treated as an ordinary organism. He came out of a sort of dream presently, holding a card in his hand, and conscious of the fact that he had promised to call at the address on the card the next morning.

And this is how it was that for the next four years Bill saw no more of Beth or Hopper, or the other wild beasts of the jungle.

He was getting on, was Bill. How far he had got on, the jungle would have been staggered to hear. They had for gotten him as completely as he should have forgotten them; indeed, they would never have recognised him had he taken it into his head to revisit the pale glimpses of the moon. But Bill had not forgotten.

He knew perfectly well that some day the call of the wild would wake in his blood, and draw him back with resistless finger to the unsavoury heart of the jungle. He had learnt many things of late, but he had not learnt to forget Beth. He could see now, of course, how badly she had treated him, but that was no fault of hers. How could you expect the she-cub to rise superior to her environments. It was a big word, but the time had come now when Bill knew exactly what it meant. For he could read Thomas Hardy now, and comprehend him. And gradually in the back of Bill's mind a dream, beautiful yet practical, was shaping itself. For Bill was bound to be practical—to a man with his intricate knowledge of machinery it was necessary. By favour of the gods he had had his chance, and now the time was coming when Beth should have hers.

He knew that he would find her exactly as they had parted; he knew that that fierce, wild, virginal instinct of hers was as a veritable harbour of refuge. She would still be prowling about with the he-cubs, taking her share of the food, and snarling and biting when they showed any signs of primaeval affection.

Beth would be a woman now, earning a precarious living from day to day, and battening on her mate—her unwedded mate—in time of stress and storm. It would be no use going to her as he would have gone to the girls he mixed with now, and offered her a home, and he knew it. Beth would have to be wooed and won according to the rules of the jungle; he would have to sink his fangs in the neck of the male beast and strangle him. Then he could lead her, with a rope about her neck, to the cleanness and sweetness of the open country, and tame her.

That is why, on a certain August Bank Holiday, he donned a neat suit of flannels, with brown boots and a bowler hat, and turned his eager feet in the direction of the jungle. He knew that the advent of a national holiday would leave the jungle cold. He walked through it with an odd sensation that his past life had been merely a dream.

The mean streets depressed him, the reek of them was heavy in his nostrils. It seemed to him impossible that he had ever lived here. Why, no decent man could breathe the atmosphere. He passed scores of familiar faces a little more degraded, a little more scarred by sin and misery, but still familiar. He saw girls that had grown into women, and lads transformed into hulking, greasy loafers, but not one of them recognised him. He had to make his inquiries cautiously, and it was nearly four o'clock before he reached his quarry.

Oh, yes; that was Beth right enough; a little older, perhaps, a little more finely drawn, but still the same beautiful, sinuous animal that Bill had known four years before. The signs and marks were all coming back to him now. He could see the pale face, with the skin drawn tight over the cheekbones, the quick play of the mobile lips, and the fierce yet strangely pathetic look of hunger in the grey eyes. And yet Bill, with his superior knowledge of men and things, could see the dormant beauty underneath the surface, as a dog-fancier can see the black pencillings under the rough coat of a terrier.

It was the same Beth, the same fierce lioness, ready to range alongside the frowsty mate of the moment in search of daily food. She moved along with restless stride, head up, and eyes in fierce revolt, searching in vain for what she could not find. Bill knew the look well enough; he had caught its reflection many a time on his own face from the polished mirror in front of some gaudy public-house.

He saw Beth pause before a girl who came out of an alley-way with a jug in her hand. Beth held out a quivering paw, and into the crooked fingers the woman dropped a copper or two. Then, as she passed along, there emerged from the dark mouth of the alley a big, hulking figure of a man, and Beth instinctively hastened.

But it was too late, for a heavy grasp was tangled with the hair at the base of the girl's neck, and her head was jerked backwards. There were no words said, and no explanation needed, for Bill knew exactly what the man was after. He took a step or two forward, and a holy joy radiated from his heart to the tips of his fingers. For this was Hopper, beyond the shadow of doubt—Hopper, big of frame and large of limb, big enough to eat Bill, as he always had been. But then, things were altered now, and Bill had learnt many things the last four years.

"Drop it!" he said. d'ye hear?"

Hopper relaxed his grasp, and turned a brutal, bloated face in Bill's direction. It was a beautiful face to punch, and Bill was quick to grasp the gifts the gods had given him. He was not champion light-weight of the Polytechnic class for nothing. He crashed his fist on the soft, sodden face, and Hopper subsided into the gutter with a cough.

"Lumme!" Beth screamed. ain't Bill!"

She had recognised him at a glance. She stood there watching in a dazed kind of way, clutching the precious coppers tightly in her hand. The shadow of a smile flickered about her lips. She was safe now, and, besides, she was going to see something worth watching. For Hopper had scrambled to his feet again, and was already advancing upon the foe. He hesitated just a moment as he, too, recognised Bill. This was Bill, whom he had thrashed a score of times—Bill, who had turned his back upon the jungle for the paths of respectability.

"Come on!" he said hoarsely. "I'll push yer fice in! I'll break yer perishin' neck!"

But he didn't. It was a cruelly uneven fight from the first. There was weight and strength on one side, and quickness and agility on the other; and, moreover, it was ten stone odd of perfectly trained bone and muscle against fourteen stone of flabby dissipation.

Beth's eyes gleamed as she glanced at the combatants, for she knew something about fighting. She showed her teeth in an appreciative grin as Bill turned his sleeves back, and she saw the rippling muscles of the forearm. And then Bill proceeded to pick out his points, as a skilled shot picks out his birds from a covey. He hit him just where and when he pleased; he hammered on the bulbous nose, on the jaw, and over the eyes, till Hopper fairly sobbed with pain and impotence. There was no time kept and no rounds, just fierce and merciless in-fighting until the loser should drop in his tracks.

Beth's eyes gleamed as she glanced at the com-

batants, for she knew something about fighting.

Finally, Hopper collapsed on the pavement like an empty sack. He rose to his knees presently, and, with lurid bitterness, proclaimed that he had had enough. Bill took a shilling from his pocket, and handed it to his fallen foe.

"Now, you go and get a drink," Bill said magnanimously. "And, Beth, you just come erlong with me."

"Where to?" Beth asked suspiciously.

Bill reiterated doggedly that she had just got to come. For the time being he was back again in the jungle, and the traditions of the wild must be respected. He knew that Beth would follow him obediently enough, and she did. She asked no questions; she was too dazed and surprised, and too much in awe as yet of her conqueror. She suffered him to take her to a public house, and give her a meal the like of which she had never tasted before. She suffered him to take her inside a second-hand wardrobe shop, and fit her out from top to toe.

"All you want's a bath now," he said. "Do you know what a pretty girl you are, Beth?"

"I was never afraid of soap!" she said sulkily.

But she really was a pretty girl, and the sudden realisation of it filled her with a certain intoxication of delight. It was all like some glorious dream. There might be questions presently, but not yet. She followed her conqueror with the same dogged obedience; she was presently enjoying a tram-ride for the first time in her life. She saw the open country and the fields and trees; and wondered almost fiercely why the tears came into her eyes and her heart grew soft.

"Like a bloomin' kid!" she said to herself, with quivering lip. "Just like a sniv'ling kid!"

She was unconscious of the fact that Bill was watching her keenly, that he was following the changing emotions on her face—a face that was strangely changed and beautified.

They came at length to a cottage lying back in a well-kept garden, an artistic cottage, beautifully furnished, and quite in the best of taste. Almost limply Beth dropped into a chair.

"What does it perishin' well mean?" she gasped.

"It's mine," Bill said simply. "I live here. Pretty little place, ain't it ! And I've two or three taxis and a workshop of my own, and I'm doing well. And all in four years, mind you. I always said that I only wanted the chance, and I got it the very day that Hopper took that half crown from me. You remember?"

Beth nodded. She remembered all right.

"And I turned my back on the jungle. But you don't know what that means. I didn't at the time, but I do now. And I always meant to come back when the time came, because I never loved a girl before, Beth; no, nor since. And l knew I should find you as I left you.

"And I've got no questions to ask. I know that the girl I'm going to marry is all right, for in the jungle you've got to follow the food, my dear, and not be thought a bit the worse of, either. It was Hopper's turn last time, and I didn't complain. I knew my day would come, and it has; and I thrashed him, and I got back the proper mate that God meant me to have. Because you ain't going back to it any more, Beth. Because why? There ain't no reason. This is your proper place, and because there ain't no more necessity to follow the food.

"You just stay here and be happy; and I'll look after the young 'uns when the time comes. You've got lots to learn, Beth, but I'm very patient, and you will understand some of these fine days. Because I'm going to marry you, my dear; and, in the long run, I'll make you a wife to be proud of. There's not a more beautiful lady in the land than you, my dear! A few months here, with good food and fresh air, will make a different creature of you, 'specially when you do your hair in a different way; and we're going to have it all done properly.

"There's an old woman here who is my housekeeper, and you'll remain here till I can fix it up with the parson. Meanwhile, I can sleep at the shop. And—and look here, Beth: give us a kiss, old girl!"

He stood before her, strong, reliant, and assured, with the consciousness of power and strength in every line of him. Beth struggled to her feet, as if she stood in the centre of blazing lightnings that illuminated every cranny of her soul, and in that moment she understood.

She threw herself upon his breast, and held him tightly to her, till he could hear her heart beating against his own.

"My man—my man!" she whispered. "Seems to me, Bill, as if I must 'ave loved you all the time!"