THE car came leisurely down the road, and a pleasant-faced young man stepped on to the wooden platform and accosted the distinguished antiquarian respectfully.

"Dr. Donald McPhail, I think," he said. "I am Raymond Welton. Sir John Denmark asked me to come and meet you."

"Oh, indeed," the famous traveller and antiquarian said. "I haven't seen my old friend, Sir John, for three years; in fact, I don't believe I wrote to him after I went to Mexico. When you are buried out yonder a hundred miles from a town, amongst those Aztec ruins, it is not an easy matter to transmit letters. I hope that nothing serious is the matter?"

"Well, not as far as Sir John and Miss Denmark are concerned," Welton explained. "But it's a ghastly business. Miss Denmark has not been well the last few days, and her maid, Lydia Wrench, has been sleeping in her mistress's dressing-room, so as to be handy in case anything happened. Yesterday morning the maid was found dead in her bed. A doctor from Plymouth who had been called in to make the autopsy was utterly puzzled as to the cause of death. So Sir John asked me to come and meet you, and he hoped that you would not mind putting up at my cottage till the funeral is over. And besides, I shall be honoured if you will come. You see, I am by way of being a novelist, and Miss Denmark and I—"

"Oh, you are Welton, are you?" McPhail asked. "I know your mystery stories quite well. What's the name of that book of yours in which you introduce an Egyptian scarab? Have you got anything of the kind on hand just now?"

"Well, I have," Welton said. "And I was going to ask you to help me, because it is all about those mysterious Aztecs, and there's no living soul who knows more about those strange people than you do. At the British Museum I stumbled on an old manuscript written something after the Munchausen style by a traveller who professed to have been out in Mexico, in the Aztec country. There was some wild legend about a butterfly called the Black Prince. Of course, it is all fiction, but the idea appealed to me so strongly that I am making it the central idea in my new story."

"So you think the manuscript is all romance, do you?" McPhail asked, quietly. "You are quite right, Welton. There is no man alive who knows so much of the Aztecs as I do. I am very sorry to hear about Denmark's trouble, and it is exceedingly good of you to put me up. As an old traveller I am quite used to roughing it."

Raymond Welton's cottage was no more than the owner claimed for it, but it was neat and clean, and the famous traveller's tiny bedroom looked out over the wide Atlantic that broke on the sands six hundred feet below. After a substantial meal McPhail lay back in a big basket-chair, smoking the coarse tobacco that his soul loved, and chatting confidentially with his young host, to whom he had taken a sincere liking.

"Most people would find it rather lonely down here," the professor said. "Not that I quarrel with that. By the way, who lives in that black old house on the brow yonder?"

"That's called Ravenshoe," Welton explained. "It was inhabited by a famous smuggler, whose dark exploits are still talked of by the fishermen. It was a fine place at one time, but only about half the house remains now. The man who lives there is a nephew of Sir John Denmark, and is, in fact, the only child of Sir John's dead sister. He's a queer and mysterious sort of man, very quiet and reserved, and no one knows much about him, except that he's supposed to be connected with some London finance companies. He bought Ravenshoe two years ago, when his wife left him, and he spends about half his time down here. According to Sir John he is an object of pity. I understand he was passionately attached to his wife, who simply walked out of the house one afternoon and declined to come back. More than that, she refused ever to see him again, or to explain her conduct to anyone. Curiously enough, it was this same Julian Rama—"

"What name did you say?" McPhail asked, suddenly.

"Rama. Queer name, isn't it? Julian Rama's father was a Spaniard from Mexico, and, I understand, claims direct descent from Acamapichtle, who was the second king of the Aztecs. Sir John says that Rama has a number of old Aztec manuscripts proving his claim, but these, I believe, he declines to show to anyone. When he hears who you are perhaps he will change his mind, though I doubt it."

"So do I," McPhail said, dryly. "However, that's neither here nor there. Would you mind, Welton, saying nothing of this, I mean as to who I am, to Mr. Rama for the present? It is just possible he has never heard of me."

"As to that, I can't say," Welton replied; "you'd better ask Sir John. At any rate, all I know is that it was when I heard Mr. Rama's story that I first conceived the idea of writing a novel round a mysterious man descended from the Aztecs, and who knows all the black magic and dark traditions which have been handed down from that mysterious race. To my mind they are quite as fascinating as the ancient Egyptian."

"Good Lord, yes," McPhail burst out, suddenly. "I should say they are. All the wickedness of Tyre and Sidon and Sodom and Gomorrah and Babylon is wrapped up and packed away in the secret history of the Aztecs. The evil spirit called Tlactecolototl, which these people more or less worshipped, had, I firmly believe, at one time a being in flesh. I tell you, I've seen things myself. I have materialized certain essences and incorporate bodies, and have produced from them results which have made me loathe myself. But you mustn't run away with the impression that this Julian Rama knows as much as I do. Unless he has been out there, as I have done, he couldn't. Probably those documents are merely so many letters to him, and I have no doubt that he is proud of his own descent."

McPhail changed the subject abruptly.

"Now tell me, as a matter of curiosity, were there any marks of violence on the body of the unfortunate girl who died so mysteriously?" he asked.

"None whatever. I saw the poor girl as she lay in bed on her right side, and she seemed to have died peacefully in her sleep. There was nothing to be seen, as far as I could judge, beyond two tiny little marks behind the left ear, no bigger than the point of a needle. They were little reddish specks, white at the base, as if a gnat had stung her. You've got two such marks on the back of your own hand at the present moment."

McPhail glanced hurriedly at his hand, and then he smiled a curious twisted smile that showed his teeth.

"You are a curiously observant young man," he said. "And now, shouldn't we walk as far as Porth Place? I should like, at any rate, just to call and see my old friends."

The blinds were drawn in the long windows and the visitors found Sir John Denmark and his daughter pacing up and down the lawn. They welcomed McPhail cordially and insisted upon his coming into the house.

"You'll find us rather subdued at the present moment," the old Anglo-Indian said. "But, of course, Welton has told you all about it?"

"Oh, yes," McPhail explained. "A most mysterious case, from all accounts. I wonder if you'd mind if I had a look at the unfortunate girl who died so mysteriously."

"Well, I—I don't see why you shouldn't," the startled baronet exclaimed. "The poor child is still lying on her bed, and I'll take you up if you like."

McPhail followed bravely into the darkened room and proceeded to pull up the blind. Then he bent over the body and examined the dead features carefully with the aid of a strong glass which he took from his waistcoat pocket. His flint-blue eyes were bent intently on the tiny little specks under the dead girl's ear. But they were tiny specks no longer: they had developed into little red marks, capped with irregular scars, deep red, with a blue ring at the base.

"My God," McPhail whispered. "So that is it! Thank Heaven, I seem to have got here in time."

The door of the little cottage was thrown wide open so that the light from Welton's reading lamp shone out towards the sea. He had just thrown aside his pen with a gesture of disgust when McPhail came quietly in.

"You have been very patient for the last few days," he said. "And now, my dear Welton, if you have any questions to ask, fire away."

"A hundred," Welton said. "It is five evenings now since I accompanied you into the bedroom of that unfortunate girl, Lydia Wrench. And I saw how deeply you were moved, though I don't think anybody else did. At your suggestion I got Sir John out of the room, and you proceeded to remove one of those tiny sores from the girl's face and put it in your pocket-book. Can you wonder, therefore, that I was curious?"

"Go on," McPhail murmured; "go on."

"Then you asked all sorts of questions. You wanted to know if the dressing-room door was open all night, and whether the door leading into Miss Denmark's bedroom was closed or not. You wanted to know if Miss Denmark's windows were open, and she told you they were. And when Miss Denmark told you that she always pinned her window curtains together in the summer time, because she hated nocturnal moths and insects, and because she had got into the habit of doing that sort of thing in India, you were considerably relieved. Also, you suggested to her that she should keep the doors of her bedroom and dressing-room locked."

"Quite so, Welton," McPhail said. "The death of that poor girl was a mere accident; the pestilence that moved by night was not meant for her at all, but for Daphne Denmark. The mere fact that the girl was sleeping in the dressing-room was unknown to the monster that we have to fight. The danger is close at hand now; it will come as soon as the fading moon is well on the horizon. Therefore the enemy has to move, because he can do nothing unless the weather is hot and fine. I told Sir John that I was going out moth-hunting, and asked him if he would leave one of the windows open so that I could get back into the house. So, as soon as the moon is fairly high, you are going back with me to Porth Place, and we are going to watch and wait for the unseen terror of the night. We shall creep quietly into the house and take our places in the corridor where Sir John keeps his pictures. I have got an electric torch, and I can lend you one too. And make no mistake of the danger. I don't wish to frighten you, but there it is. And that's the sort of thing that tries people's nerve."

"All the same I am quite ready," Welton said, quietly. "I am fighting for the woman I love, and for the woman who loves me. I'd do anything for Daphne."

"I know. Now, if anything happened to Sir John, and especially if anything happened to Daphne, where would the bulk of the Denmark money go to?"

"Why, to Rama, of course. But you don't suggest that a man who is already married, and has a wife living—"

"I suggest nothing. I have been making inquiries; in fact, I've kept the telegraph office at St. Enoc busy during the last few days. You may be surprised to hear that Julian Rama is in desperate need of a thousand pounds."

"Oh, indeed," Welton exclaimed. "Is that why Rama has been in town all the week?"

"My dear fellow, he hasn't been in town at all. He's been here all the time. Like you, he lives all alone, at Ravenshoe, so that he can come and go as he likes, and a man who runs a motor-cycle as he does has only to disguise himself in goggles so that he might pass, even in the village, as a wandering tourist. I am going to show you something to-night that you have never seen before. On the face of it it is nothing but a photograph of a fresco on an old Aztec temple. That fresco I destroyed, but I took this photograph first. Isn't it good?"

The photograph displayed the figure of a woman in Aztec robes lying at full length upon a couch with a hard, white face turned upwards. On one temple something seemed to have perched, something that looked like the petals of a fallen flower, till Welton came to examine it more carefully, and then he saw that it was a gigantic butterfly. There was something weird, and yet so repulsive about it, that Welton shuddered as he gazed at it.

"There is a horrible suggestion about the whole thing," he said. "But it conveys nothing to me."

"It will later on," McPhail said, grimly. "My friend, that's the Black Prince. But come on, we are wasting time here. By the way, have you got any more of that honey that you gave me for tea last night? If so, you might bring a section with you."

Like two burglars they crept into the hall of Sir John's house and up into the gallery. Not a sound did they make, not a sign of their presence did they give, except just once, when McPhail flashed a ray from his electric torch in the direction of one of the bedrooms, after which he proceeded to deposit the section of honeycomb upon the mat outside.

"Sit there," he whispered. "On that oak chest. And take this long-handled Oriental fan in your hand. I have got one too—in fact, I've borrowed them off the wall yonder for the purpose. I'll take my place on the chest on the other side of the corridor, and when the time comes I'll give the signal. Only you're not to make the slightest noise. When I say the word, turn on your electric-torch and thrash about in the air with your fan as if your life depended upon it. I may tell you that it probably does. Now, then."

The electric torch was extinguished, and for a time the two men sat there breathing heavily in the violet darkness. And so it went on for an hour or more, till Welton could feel himself tingle in every nerve, until he felt that he must either rise from his seat and walk about or scream aloud.

And then, suddenly, a queer humming sound broke the intense silence. It was as if a gentle steady breeze was blowing against a highly-strung wire, or as if the two were listening to the dying vibrations of a tuning-fork. It was not a great noise, but in the darkness and silence of the place it struck on Welton's ears with a force that set him trembling in every nerve. It seemed to be all round and about, sometimes up in the roof of the gallery, and then again within a foot of Welton's grey, ghastly face. Then to his relief McPhail spoke.

"Now," he said. "For Heaven's sake, now!"

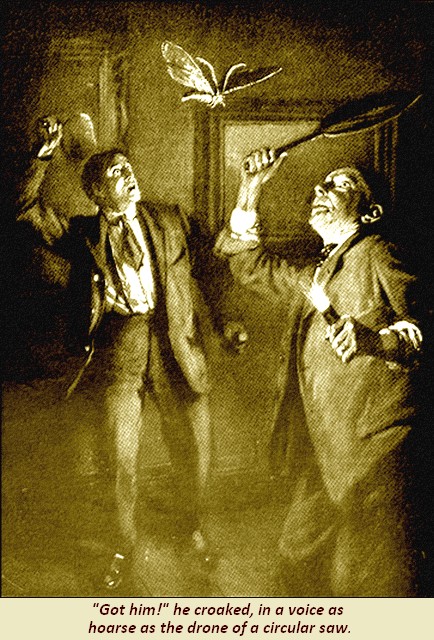

Welton sprang to his feet and thrashed the dark with the long-handled fan till his arm ached and the perspiration rolled down his cheeks. He was dimly conscious that McPhail was doing the same thing, and then suddenly the professor ceased and a long white ray from the electric torch cut into the darkness. Then something seemed to hum and vibrate, something dazzling in purple and red, and a splendour of spangled gold, followed by the dull impact of some flying body as it came suddenly against a downward sweep of McPhail's fan. For the first time McPhail spoke aloud.

"Got him!" he croaked, in a voice as hoarse as the drone of a circular saw. "Got him! He's past all danger now. Come and have a look, Welton; there's nothing to be afraid of."

Down there on the floor was a huddled mass of some fluffy material, a mangled heap of beauty and colour all blended into one shining and sticky mass.

"The Black Prince," McPhail explained, hoarsely. "The most damnably beautiful thing that ever came out of hell."

"But what is it?" Welton whispered.

"I can't explain here; and, anyway, we haven't finished yet. No, for Heaven's sake, don't touch it. There is nothing more exquisitely beautiful or more deadly poisonous on the face of the earth. And now do you understand what has been worrying me?"

"That devil Rama," Welton exclaimed.

"Of course. Now just wait a minute whilst I get a pair of thick gloves and remove all traces of that hideous mess. Then we'll go as far as Ravenshoe and have this matter out. Unless I am greatly mistaken we shall find the scoundrel at home."

As the two men walked through the moonlight, McPhail proceeded to enlighten his companion.

"It's like this," he explained. "In the ordinary circumstances you would never have got anything out of me about the Black Prince, though, of course, I was interested to hear that you had found that old manuscript at the British Museum. But when you told me all about Rama and the tragedy at Porth Place, then, I must confess, I was disturbed. That's why I asked to have a look at the unfortunate woman. And one glance convinced me that she had fallen a victim to perhaps the most insidious and powerful poison in the world."

"What do you call it?" Welton asked.

"Terafine. It is only found in one insect, and that is the Black Prince. I told Professor Skelton about it a year or two ago, and he made certain investigations on specimens supplied by me, and up to now those investigations are a profound secret. I recognized terafine at once, and the professor confirmed my opinion when he placed that little scab I sent him under the microscope. Then I knew beyond doubt how the girl had died, and I began to make further inquiries into the career of Julian Rama. I found that he was absent frequently in South America on mysterious errands which he said were in connection with a mining concession. And here he doubtless came across the Black Prince. And I found it myself; ah, yes!"

McPhail's voice trailed off for a moment into a hoarse whisper, and the old horror crept into his eyes.

"I don't want to dwell upon that time," he said. "Sometimes I dream of it in the night and wake up wet and cold. But yet I cannot wipe out of my mind the recollection of that evening in the old ruined temple, covered with creepers and orchids, where I first met the Black Prince—met it on the fourth night, under the light of the full moon; when I was watching all alone I saw the infernal thing. I saw a dozen of them, disporting themselves round the remains of a hive of honey which we had taken from a decayed tree. And I fought them, as in the old days they fought the wild beasts at Ephesus. I killed them all, and I buried them whilst my natives slept. I did not want my people to find that the legend was true; but from that day on I never entered an Aztec ruin except in the daylight. And now you know why I asked all those questions, and why I asked Sir John not to identify me with McPhail the antiquary. I didn't want Rama to know who I was, and I don't think he guesses. Come, let us get along, because our night's work is not finished yet."

As they pushed up the slope in the direction of Ravenshoe a fisherman came hurrying along the cliff and pulled up as Welton hailed him by name.

"What's the matter, Tyre?" he asked.

"It's a bad thing that's happened," the fisherman said. "I was going along the cliffs just now, in the direction of Marham, when I see a big car coming up the road with three men in it. One of them was Mr. Pascoe, over to Bodmin, who's Chief of Police there. And from what I could gather the other two were from London, and they had a warrant for Mr. Rama's arrest."

"Then he is a prisoner?" Welton asked.

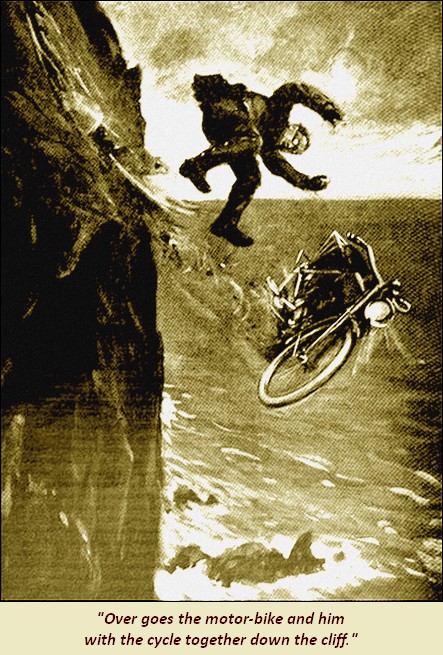

"Well, no, sir; not in a manner of speaking. Mr. Rama, he must have been looking out for them, for when the car was a quarter of a mile away he comes dashing along on his motor-bicycle down the road and the car pushed on to cut him off. Then Mr. Rama, he swerves round over the headland yonder, so as to make a loop and gain the far side of the Marham Road, which takes him over the slippery grass down the side of the slope, and just then he turns quickly, and over goes the motor-bike and him with the cycle together down the cliff into the sea beyond. I was on my way to tell Sir John."

"Oh, we'll do that," Welton said. "You go down to the beach and see if you can be of any assistance."

As the fisherman vanished McPhail pushed on.

"Come along," he said. "We are not likely to be interrupted, and I couldn't sleep to-night till I have been all over that house. I am not fool enough to believe that that monster Rama has exhausted his supply with two of those loathsome insects. They are tropical insects, and could not live for long in a climate like ours, except in torrid weather, and only then when the moon is in the second quarter. But we have had some very hot nights lately, except for three evenings this week; and this afternoon it was so warm that I knew an attempt would be made to-night. And I was right."

"But if those things are so dangerous to handle?"

"Not to a man who is used to knocking about in motor attire. Mackintoshes and masks and thick gloves not only served Rama as a disguise, but acted as a protection as well. He stole down to Porth Place to-night with one of those infernal moths in a box; he had previously, no doubt, smeared the transom over the bedroom floor with honey, and the big window in the gallery was open. And now, come along and let us wipe out all records."

There was no difficulty whatever in getting into Ravenshoe, for the front door stood wide open, giving on the big hall of the deserted house and the dining-room beyond, where a lighted paraffin lamp stood on the table. In one corner of the room was a safe, the door of which was ajar, and this was crammed with old manuscripts covered with quaint inscriptions that McPhail's experienced eye immediately recognized as Aztec.

"There, what did I tell you?" he said. "Clear that safe out and push all the documents into that sack lying in the corner. Then open the windows and throw it out, and we'll come and recover it in the morning. Upstairs, I think."

They made their way up the wide staircase and searched every room there with the aid of their electric torches. McPhail appeared to be dissatisfied until, presently, he came to a door let into the oak panelling, a door with a catch and button on the outside which he proceeded to open. On the other side of the oak barrier was a network of fine steel in the form of a mesh, and from the room itself gushed a warm odour of hot steam which was mingled queerly with a faint sweet odour that seemed to fill the whole atmosphere.

"Ah!" said McPhail. "Here we are!"

He turned the brilliant lane of light from his torch upon the prison house behind the steel mesh, and almost immediately there arose that peculiar sharp humming musical note that Welton had noticed an hour or so before in the corridor of Porth Place. Then a shadow seemed to fall from the roof, and poised motionless with wings whirring so fast that they hardly seemed to move, and in that instant Welton was gazing with fascinated eyes at the most beautiful thing he had ever seen.

It was a great moth, some ten inches across the wings, velvet black as to the body, with a broad band of royal purple exquisitely patterned like fine lace. Towards the base of the wings the blackness shaded away to a pale blue and the long body glowed beneath a mass of vermilion-coloured hair. On the head was an irregular star-shaped mark that might have been a tiny indented crown of pure gold. The great eyes of the moth trembled and scintillated like opals. It was at once beautiful, and yet sinister and repelling. It hovered there just for a minute or two, then fluttered lightly to the floor with wings outspread as if half-conscious of the admiration that it had created. And yet, alluring and beautiful as it was, Welton shuddered from head to foot as he regarded it.

"There," said McPhail. "So far as I know, only three men have ever gazed upon its like before. It is an exquisite thing, and yet deadly poisonous, as you know. Just one touch of that crimson body, and you would be a dead man within five minutes. It seems a pity to make an end of such a beauty, but it must be done."

"What are you going to do?" Welton asked.

"Burn the infernal place down," McPhail shouted. "Destroy it. Wipe it off the face of the earth. Probably if I turn the steam off, those moths will be all dead by morning; the chrysalids and caterpillars would perish, but I am taking no risks so long as this hot weather lasts. If hell opens and looks you in the face, blot it out. Smother it, and destroy it. Now, come with me down to the garage and we'll find a can of petrol and soak the dining-room with it. Don't you think it's the proper thing to do in the circumstances?"

"I'm with you," Welton said, between his teeth. "The whole thing is incredible; the sort of thing that could only happen in the pages of a book."

"And you're the man to write it," McPhail said, as a little later he tossed a blazing match through the dining-room window on to the petrol-soaked floor. "Here's a plot that nobody will believe, though you'll get every credit for your powers of imagination. And after all, it's a sound saying that truth is stranger than fiction."