SALTBURN scooped the beaded sweat from his forehead and flicked it from his fingers as it had been something noisome.

"I'd give," he muttered—"Heavens, what would I not give for a tub of sweet, wholesome, hot water and a piece of yellow soap? Ralph, I stink—we both of us stink! The effluvia has got into the pores of my skin. I am loathsome and repulsive to myself, and my mind's getting as vile as my body!"

Ralph Scarsdale sat up like a startled rabbit in a field of corn.

"Now, that's dashed odd!" he gurgled. "I've been sitting here for the last hour, sweltering in my own juice, and thinking exactly the same thing. It's queer, Ted, my boy, very queer. I suppose this infernal country is getting on our nerves. Were we not the best of friends?"

"Pals for years," Saltburn said, as if making a confession he was ashamed of—"school and college. Made fools of ourselves together, lost our money together, and came out here together. Three years ago? Three centuries!"

"Ever feel at times as if you hated me?"

"Yes, you and myself and all creatures, black and white. It's the fever of the place, my son. It's in the air that rises from this dismal swamp. You can produce the same effect by drink, if you take enough of it. You hardly call a man a murderer who kills his best friend during an attack of delirium tremens. Yet, if I put your light out here, and a slaver-hunting gunboat happened along at the time, I should swing for it. And yet it's just the same thing. Hartley warned me of it before we came out. He said it was a disease you catch, the same as Yellow Jack. Boil it down to the formula of the medical dictionary, and it's homicidal mania."

Now, this was a strange conversation for two bosom friends to be having in the dead of night on the beach at the mouth of the Paragatta River. It was the first time for months that either of them had given to the other an insight into his mind. For months they had been growing more moody and silent. They had little tiffs—whole days when neither spoke. And Saltburn was drinking too much whisky, Scarsdale thought. And Saltburn knew that Scarsdale was overdoing it, otherwise why was it necessary to open one of the case bottles so frequently?

They had drifted here, broke to the world, glad to look after copra for old Hans Breitelmann, the fat and prosperous old Dutchman down at Dagos. And they had stayed because they had heard the story of the Redpath Pearls. The Redpath Pearls were there hidden in the swamp, all right. It was no fairy tale; Joshua, the Papuan servant, had seen them once. It was Josh who kept them going, who stimulated curiosity and, be it said, greed. For the sake of their bodies, to say nothing of their souls, they should have turned their backs upon this hideous swamp, and they knew it. But, if they could find the pearls, they were made men. The pearls were in little wicker baskets attached to a float in the middle of the swamp. These Redpath had hidden there before the Papuans murdered him, and they were there till this day. But it was impossible to fish or boat or work an oar in that oily blue-and-gold scum, which the tide hardly touched. Josh had a legend to the effect that, at certain spring-tides, the swamp was passably dry, and, given a north-east gale of sorts, the tide was held back, sometimes for a day or two, and then under the sun the mud caked hard, and one could cross the lagoon dry-shod. He had seen this more than once himself, but not since Redpath had hidden the pearls there. If the excellent gentlemen would only wait—

And they had waited, but they were looking into the bloodshot eyes of stark tragedy. The heat, the loneliness, the desolation of it, had long since frayed their nerves. They had come to the point now when they no longer talked, but merely muttered. It was weeks since eye had looked into eye, and times when a smile might have suggested insanity. There was a mark on the side of Scarsdale's neck—a red mark—and Saltburn wondered how it would look with a razor-slash across it. And Scarsdale's sister's letter was in his pocket, and her photo in a case next his heart.

Josh, the Papuan, was squatting somewhere near in the reeking darkness, watching. Nothing disturbed his serenity; he was troubled by no scruples or frayed nerves. He was just eleven stone ten of original sin—as all Papuans are—without heart or conscience or bowels of compassion. He was a loathsome thing, born of the meanness and rottenness of corruption, a human upas tree, a hawk to be shot at sight. He would have murdered his employers long ago had it been worth his while to do so. He had argued the matter out philosophically a good many times. But they had no money or articles of value, and their premature demise would have meant the cutting off of Josh's whisky. He was prepared to crucify creation for a bottle of "square-face," Still, this taking off of the white men would only have meant one colossal spree, followed by a total abstinence, perhaps, for years. It was far better to get just comfortably drunk every night, and this inevitably was the reason why Scarsdale and Saltburn suspected each other of overdoing it.

And now there had come along a temptation that shook the philosophy of the Papuan to its foundations. Eight, nine, ten cases of whisky had arrived by the last copra boat from Dagos, awaiting Breitelmann's orders. And Josh's strong point was not arithmetic. He figured out that here was enough whisky to carry on a fine, interminable, whole-souled jamboree to the confines of time. He pictured himself alone with these cases. They would have to be smuggled away and safely hidden, of course. One by one the bottles would have to be stolen, and their places taken by empty bottles filled with water. If he was caught at the game, he would be shot on sight, but the prize was worth all the risks. Therefore it resolved itself purely into a matter of time.

If the Englishmen stayed, it was all right. If they resolved to chuck the whole thing, then it would be wrong. If they went, they would send up to Paterson's station for help to clear the stores, and then the glorious opportunity would be lost for ever. And they were talking about going at that very minute. Scarsdale and Saltburn had seen the red light—they had not been in this accursed country three years for nothing. They had seen a new-comer shot and nearly killed merely for telling a funny story and laughing at it afterwards. Some spring had been touched, and the two friends were nearer together than they had been for months. And Josh's sharp ears took in every word of it.

He came towards the crazy hut and kicked the fire together with a heel as hard as ebony. The fire was a mascot, and kept some of the mosquitoes off. In an attitude of fine humility Josh waited for orders.

"Ain't any," Scarsdale said curtly. "Be off, ye scoundrel!"

"Big spring-tide, morning," Josh grinned amusedly. "Un biggest spring-tide since three more years. Wind am gone north-east."

Surely enough, the hot north-east wind was reeking with rottenness and corruption, and blasting like a furnace at the door of the hut. The man who takes the future in his hands, and is prepared to back it against the forces of a continent, is ever a gambler, and Scarsdale's nostrils twitched. A red spark gleamed in Saltburn's eyes. If what Josh told them was true—

Half an hour ago they had practically made up their minds to leave the place. The resolution was wiped off their mental tablets as by a sponge. Simultaneously the same thought leapt to each mind. They had been here three years, hungering, thirsting for these pearls. They had been pushed to the verge of insanity for the sake of them. And if success came now, it meant everything. It meant fortune, and comfort, and clothes, and hot baths, golf, shooting, hunting, fishing, and, for one of them—Saltburn—the kisses of Mary Scarsdale on his lips. And, curiously enough, he could not at the moment think of her as Scarsdale's sister. There was no cohesion in the world just then; everything was resolving itself into original atoms.

Who was that chap sitting on the other side of the fire? For the life of him, Saltburn could not put a name to the other. It was merely a man—a superfluous, unnecessary man, who was probably after the pearls also. In other words, an enemy to be watched. If the pearls were to be found, Saltburn was going to have them. Why should he trouble about the other fellow? Oh, the poison was rank and strident in the air to-night!

And Scarsdale was following Josh with a hard, vulpine curiosity.

"Very big ebb," the rascal went on cheerfully, "an' much sun to-morrow. Lagoon be dry by nightfall. Perhaps dry for three—four days, if wind can hold on. An' pearls—dem hidden in lagoon."

Josh passed on to his own quarters, his teeth showing in an evil grin. He knew exactly what the two men were suffering from—he had seen the disease often before. He had seen battle and murder and sudden death spring from it. Generally it took the more prosaic form of drink, followed by the purple patches of delirium tremens; but Scarsdale and Saltburn had successfully avoided that, though they suspected one another—to Josh's material advantage. He had been racking his brains for a way of keeping the two on the soil a little longer, and, just as mental resource had failed him, the wind had changed. He had always prophesied that, sooner or later, the wind and tide would conspire, and the sea would give up its dead, so to speak. But he had never really counted on it. He would not have dared to touch the pearls himself, for they were haunted. With his dying breath Redpath had laid a spell on them. The hand of the Papuan that touched the shining discs would wither at the wrist and rot, because Redpath had said so, and he was a man of his word. Josh did not care a red cent for the pearls, but he was very keen and very desperately in earnest so far as concerned the cases of whisky. Therefore the change in the wind had come just in the nick of time. He would have three or four days more, at any rate, for he had seen at a glance that the men did not mean to go before they had had a shot at the pearls. In the ordinary course of things, they would have discussed Josh's news. A few months ago they would have caught at it eagerly.

As a matter of fact, they turned into their respective bunks with never a word passing between them. The hut simmered in the heat. There was a deadly silence save for the sharp ping of the mosquitoes. It might have been taken for granted that the two men were fast asleep. As a matter of fact, each lay in his bunk looking into the darkness with hard, restless eyes.

"I shall never sleep again," Scarsdale was telling himself. "And yet there was a time when— How many centuries ago was that? No such thing as sleep in this accursed continent. If I could get away from it! Only let me finger the pearls! They are as much my property as anybody else's, and I do not see why I should share them with anybody. Heavens, if I could only sleep!"

He dropped into a kind of soddened doze presently, yet half conscious of himself all the time. He tossed and muttered uneasily.

"I'll get 'em," Saltburn was telling the darkness. "See if I don't! Why should I share them with anybody? I spoke to Josh first. Funny thing! I'd a queer notion in my head that I'd got a partner in the business. But the other man who was here to-night is no partner of mine. Bound to be civil to the chap. But when he comes talking of shares And Scarsdale's drinking too much whisky! Why should I worry about that? And who is Scarsdale? And where have I heard the name before? Sleep, you fool, sleep!"

He grabbed at himself with a certain despairing rage. But he, too, dropped off presently into the same strange, half-alert semi-unconsciousness till the dawn came and the sickly, languid day rose from the sea of oil and ooze. Scarsdale had disappeared, but Saltburn thought nothing of that; he had actually forgotten the very existence of his friend. There was a little more sign of dampness in the wind to-day; then came the blessed consciousness of something to be done. If the wind held good, he would have the pearls or perish in the attempt. And the wind did hold good. The orange-yellow mist faded away, and the sun beat fiercely over the mud of the lagoon, while the reek of a thousand acrid poisons filled the air. The sluggard tide was creeping in from the sea again, but it did not reach the lagoon, for the fierce level beat of the north-east wind kept it back. Saltburn grinned as he saw the hard, dry mud caking on the surface. He asked himself no questions as to Scarsdale. It never seemed to occur to him to wonder where the lake had gone to. When the fiery orange sun began to dip, he would go out to search. And when these pearls were his, ah, then—

The great copper sun was beginning to slide over the shoulder of the mango groves before Saltburn set out on his journey. He had the air and manner of a man who walks in his sleep. His red-rimmed eyes were hard and vacant; his lips twitched oddly, as if they had been made of elastic. It was all one to Saltburn, as he had not tasted food since he had dragged himself from his bunk. He had touched the ground in accordance with the laws of gravity, but to him it was as if he were plunging along knee-deep in cotton-wool.

He came to the edge of the lagoon presently—came to the edge of the liquid ooze of amber and gold and crimson, where the tide had ebbed; but the brilliant dyes were there no longer, and the flow of the lagoon was baked to grey concrete. He crept across it like an old man. Now and then a foot would go through the crust and bring him up all standing. He knew his way by heart. Away to the left was the remains of a wreck, cast up there ages ago by some great storm or intense volcanic disturbance, and there Redpath, flying headlong from his foes, had cast the pearls before he had been sucked down by the mud and suffocated by the slime and ooze and filthy corruption of it. How Redpath had contrived to get so far was a mystery.

He had found some sort of a footing, some sort of a trail on the lagoon by accident. Another fifty yards, and he might have reached safety and the river. For the river was there, as more than one rascally slaver knew. They found salvation there sometimes, when His Majesty's gunboat Snapper was more than usually active. Saltburn was on the spot at last. Down here, under the sand somewhere, the wicker baskets containing the pearls lay. And Saltburn was groping for them like a man in a dream. He broke his way through the crust on the mud and plunged in his arms. He was black to the shoulders, as if he had been working in ink. He fought on with a sudden strength and fury; new life seemed to be tingling in his veins. Presently his right hand touched something, and he drew it to the light. It was one of the small wicker baskets, dripping and slimy. Inside was a handful of round, discoloured seeds— the pearls beyond a doubt.

Saltburn burst out into a drunken, staggering, hysterical yell. Fortune and happiness, comfort, prosperity, all lay in the hollow of his trembling hands. He grasped blindly and hurriedly, and again and again with the same pure luck. One, two, three, four of the little baskets! Hadn't somebody told him that there had only been four of the baskets altogether?

Now, who the deuce had he got the information from? Why, Josh, of course! And where was Josh? Confound him!

Josh was not far off. He was standing on the edge of the lagoon, showing his great white teeth in an expansive smile. He was waiting for Scarsdale to put in an appearance. Josh was a bit of an artist in his way, with a fine eye to an effective curtain. And the air was heavy with impending tragedy. There would be murder done here, or Josh was greatly mistaken. And when these two bosom friends had choked the life out of each other. Josh would collect the whisky and report the matter, and that would be bhe end of it.

Scarsdale was coming now, approaching Saltburn from below the wreck. He stood for a moment contemplating Saltburn in a dull, uncomprehending way. He, too, was like a man who walks in his sleep; he had the same hard, red-rimmed eyes, the same elastic twitching of the lips. Who was this mud-lark, and what was he doing with another man's pearls? It was that blackguard Saltburn, of course. Curse Saltburn! The fellow had followed him everywhere—had been the bane of his existence. He had always hated Saltburn from the bottom of his heart—could never get rid of him. And here was the scoundrel robbing him of his fortune before his very eyes!

With a roar of rage, he dashed forward.

"Get out of it!" he croaked. "Go back to your kennel, you hound! What do you mean by coming here and robbing me of my hard-earned money? You were a sneak and a thief even in your school-days!"

Saltburn showed his teeth in an evil grin. "Come near me, and I'll kill you!" he said hoarsely. "Come near me, and I'll take you by the throat and choke the life out of you! Call me a thief, eh? What do you call yourself, then? You'd take the coppers from a blind man's tin! Keep away, or I shall do you a mischief!"

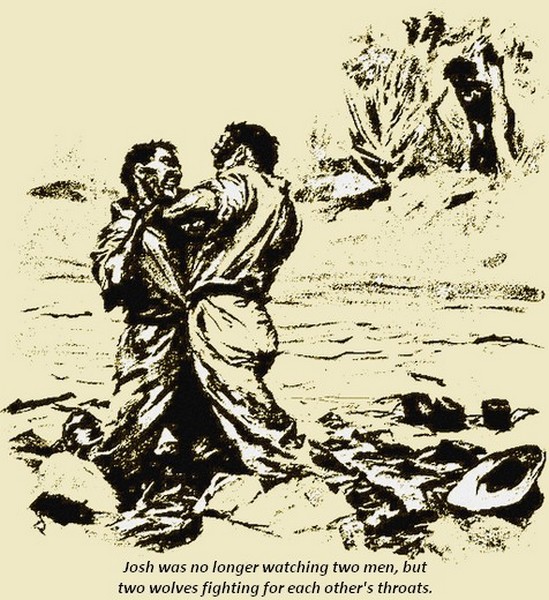

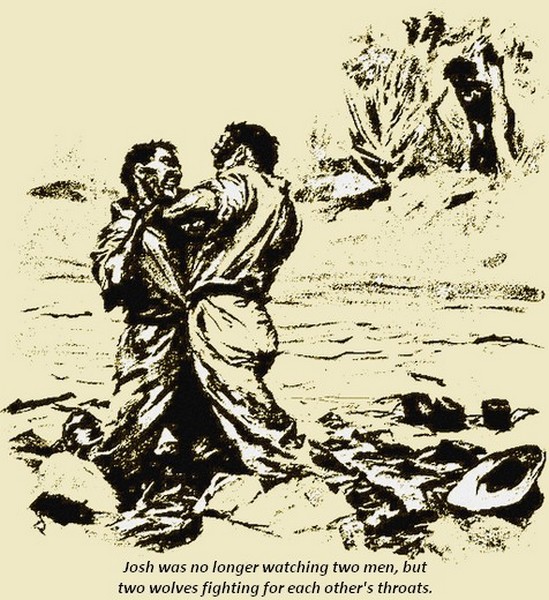

Scarsdale came on, gibbering and muttering. They were at grips, to the great delight of Josh, standing like a black sentinel on the edge of the lagoon. Ah, this he had engineered carefully and cleverly! Why should he take the trouble to kill those two white men when they were so ready to destroy each other? They had never done him any harm, either; on the contrary, he had enjoyed a great many splitting headaches at their expense.

He saw the white men grip and reel and stumble; he could hear their cries and curses, as the bark of civilisation peeled off and the raw primeval man underneath stood out in his hideousness. Josh was no longer watching two men, but two wolves fighting for each other's throats. He saw how the mud was being churned up in the struggle, he saw flakes of the crust break away like ice on a lake in the springtime. It was all very well for one man to walk circumspectly on the thin rind of dry mud, it was possible to make holes in it and be safe, but here was a different matter. The ice had given way, so to speak, and these men were in a sea of mud, with the certainty of a horrible suffocation before them. They were sinking deeper and deeper in the pernicious slime without being in the least aware of it. All this Josh saw, and a great deal more from his seat in the stalls.

But there was one thing he did not see, for it was concealed under the edge of the bank that formed the margin of the sluggish river. He did not see a boat belonging to H.M.S. Snapper, full of blue-jackets and armed marines, creeping cautiously along in search of the slave dhow that lay concealed, as the commander of the Snapper very well knew, in a creek hard by. The look-out in the stern had a keen eye and ear for sign and sound, and at the hideous din going on just over his head he stopped. It was no difficult matter to climb up the sun-dried bank and investigate. And Lieutenant Seaton understood. He had heard of this form of malarial madness before. He swept his eye round the lagoon and took in the nigger in the stalls like a flash. And Josh realised the delicacy of the situation all too late. A couple of bullets whizzed by his ear, and he stopped. A sergeant of marines beckoned to him and he went.

"Rise up, William Riley, and come along with me," the sergeant quoted. "Now, sir, what are we going to do about this?"

"Get back to the ship," Seaton directed, "and hand these two poor devils over to the doctor. Take the nigger with us as well. One of these madmen thinks that those baskets are full of pearls. Better humour them and take the baskets along. The black rascals of the creek will keep for an hour."

Scarsdale and Saltburn lay in the bottom of the boat, half suffocated, wholly exhausted, and quite oblivious to their surroundings. They were both in the heart of some hideous nightmare. Whether they came out of it or not was very largely a matter of indifference. The commander of the Snapper looked at his deck, then looked at the doctor, who seemed to have grasped the situation.

"Mad as hatters," the doctor muttered. "These chaps have got malarial mania, which precedes chronic insomnia and madness. Good food and sea air is the cure. Well get these chaps bathed, and I'll put a few grains of morphia into each, and they'll sleep the clock round. When they come to themselves, they ought to be as right as rain."

"Um! Morton says that it was no delusion as to the pearls. He says they are real pearls and worth a huge fortune. I'll bet that nigger can tell a story. Seaton, send the Papuan to my cabin."

Josh made the best of it. He told the story of the Redpath pearls and how they had been found. He had a good deal to say also on the score of the slave dhows and their artful ways, all of which pleased the commander of the Snapper very much. But he quite forgot to say anything about the whisky, and that must remain a secret.

"I've got those chaps cleaned and in bed," the doctor explained, as the armed boat dropped away again, with Josh in the bows to act as guide. "When I soaked them out of the mud, I found an old chum of mine called Scarsdale. Oh, yes, I pumped some considerable morphia into them, and they dropped off peacefully as kids. Shouldn't be at all surprised if they slept for the next four-and-twenty hours. Anyway, we found 'em in the nick of time."

It was, as a matter of fact, the morning of the second day before Scarsdale stirred and opened his eyes. A brace of slave dhows had been destroyed and their crews shot, and the Snapper was in blue water again. The fine crisp breeze blowing in through the port-hole swept Scarsdale 's cheek, and a pure hunger gripped him.

"Where the deuce am I?" he muttered, "And what a head I've got on me! If this is a dream, Heaven send I may go on with it!"

"Then we're dreaming together," Saltburn said from the next bunk. "We're on a gunboat, my son. Here, let's try to think it out. Where were we? And what the dickens were you and I quarrelling about?"

"The pearls!" Scarsdale cried. "We were both after the pearls. The wind had gone round to the nor'-east. Don't you remember? We must have been fighting like cats until these good chaps picked us up. I'd bet a dollar they were creeping along after slavers and spotted us. And we were trying to murder one another, old boy! By Jove, it is coming back to me a bit at a time!"

They lay there thinking it out in silence, a strained, shamed silence, for each was holding himself as actually to blame. They were still deep in retrospect when the doctor looked into the cabin.

"Well, you chaps?" he said breezily. "Hallo, friend Scarsdale! Haven't forgotten Monroe, eh? Because that's me. And this is the Snapper, and I'm her doctor. Small place the world, after all, isn't it? Oh, yes, we took you off the mud all right. We got it all out of a picturesque rascal who said his name was Josh. Friend Josh gave us the slip during a little scrap we had up the river yesterday, so he's done with. Now, don't you fellows say anything and get blaming yourselves. I have heard of your particular trouble many a time before. And, however, luck came to you just at the right time. We saved your lives and your pearls, too. One of our men, a judge of stones, says they are worth a couple of hundred thousand quid easy. A few good meals and a day in bed and the air will put you as right as right can be. We fetched your kits away, and your clothes are here. Now get up and come to breakfast."

"What's the next move?" Scarsdale asked unsteadily.

"Back home," Saltburn said, with lips that trembled. "England, home, and beauty. And jolly well stay there, as far as I'm concerned. Old boy, as far as that goes, I don't care if the last two years be never mentioned again."

"It's a bet," Scarsdale said fervently.