APART from numerous novels, most of which are accessible on-line at Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan's Library, Fred M. White published some 300 short stories. Many of these were written in the form of series about the same character or group of characters. PGA/RGL has already published e-book editions of those series currently available in digital form.

The present 17-volume edition of e-books is the first attempt to offer the reader a more-or-less comprehensive collection of Fred M. White's other short stories. These were harvested from a wide range of Internet resources and have already been published individually at Project Gutenberg Australia, in many cases with digitally-enhanced illustrations from the original medium of publication.

From the bibliographic information preceding each story, the reader will notice that many of them were extracted from newspapers published in Australia and New Zealand. Credit for preparing e-texts of these and numerous other stories included in this collection goes to Lyn and Maurie Mulcahy, who contributed them to PGA in the course of a long and on-going collaboration.

The stories included in the present collection are presented chronologically according to the publication date of the medium from which they were extracted. Since the stories from Australia and New Zealand presumably made their first appearance in British or American periodicals, the order in which they are given here does not correspond to the actual order of first publication.

This collection contains some 170 stories, but a lot more of Fred M. White's short fiction was still unobtainable at the time of compilation (March 2013). Information about the "missing stories" is given in a bibliographic note at the end of this volume. Perhaps they can be included in supplemental volumes at a later date.

Good reading!

FROM Paradine's point of view—and that, after all, was the outlook that most concerned him—the tiny block of flats on Campden Hill was the breeziest and most picturesque prospect in London. For Capel Hill Court had at one time been what the auctioneers call a "desirable family residence standing in its own grounds," before the inside had been torn out and subsequently refitted with an electric lift and a commissionaire in scarlet uniform, a telephone switchboard, and what is known as "every modern convenience." The garden still remained intact, and Paradine occupied one of the pair of flats on the top floor, from the roof of which he could look down into the gardens and away over the high ground to the distant Surrey Hills. And it had been his whim to erect a tent on the flat roof, and surround himself with flowers and shrubs in imitation of the hanging gardens of Babylon. On summer evenings, when he was in the mood, he was wont to sit out there in ruminating solitude, and work out those brilliant problems of his for the benefit of suffering mankind. For Paradine was one of those fortunate individuals well endowed with this world's goods, who could afford to pick and choose in the field of surgical science—in other words, he was a brain specialist, attracted only by certain phases of cerebral disorders and diseases, or the troubles brought about by accident or catastrophe. Unless a case appealed to him, he declined to take it. He would have nothing whatever to do with the ordinary "mental" case, and turned his back resolutely upon fashionable "nerve" patients, brought about by luxurious living or that selfish introspection which is often the result of too ample means and too little healthy occupation.

It was rarely, indeed, that anybody shared Paradine's solitude on what he called his lonely mountain height. And his next-door neighbour was probably unaware of the fact that he also had an exit on the garden roof. For the next-door neighbour was no less a person than Professor Ionedes, the famous Egyptologist and recognised authority on prehistoric coinage. As a matter of fact, Paradine had hardly ever seen his neighbour, who was an elderly man of pure Greek descent, and a master of many languages. Paradine knew by repute, of course, that the flat adjacent to his contained the finest collection of gold coins in the world; he knew, too, that his neighbour was a somewhat eccentric recluse, and that he was frequently absent from London on one of his many excavating expeditions. And when Ionedes was in the metropolis, he rarely showed himself in society, he had practically no visitors, and was looked after in a perfunctory sort of way by a charwoman, who came over in the mornings to do the necessary cleaning and get the Professor's breakfast. The rest of his modest meals the great numismatist took in an obscure little restaurant in Kensington High Street. All this Paradine knew in the way of vague gossip which filtered to him from time to time through the medium of his own servants. He was aware, too, that some year or two before an attempt at burglary, doubtless with a view to the gold coins, had been made on the Professor's flat, and that since then the front door thereof had been fitted with a steel lining, beyond which it was impossible to penetrate without the possession of the master-key. All this interested Paradine quite in a languid way.

Certainly he was not thinking about it that perfect June evening, as he sat there under the shadow of his palms in a comfortable arm-chair, looking out dreamily across the gardens to the blue hills in the distance. As a matter of fact, he was working out the details of a case, the fine definite points of an operation which he had decided to make on a patient at that moment lying unconscious in a hospital off the Brompton Road. The train of thought was nearly complete, when it was rudely derailed by the sound of a noise and the heavy thud of a falling body, apparently just underneath.

Paradine jumped to his feet and looked eagerly about him. So far he could see nothing, for the well and sufficient reason that there was nothing to see. He peered down the wooden stairway which led through the water-tank in the roof of his own flat on to the ledge beyond, but he could see nothing there. He was about to return to his chair again, when he heard the heavy thud once more, coming unmistakably, or so it seemed, from the direction of the flat next door. Paradine crossed the leads and squinted through the gloomy skylight that was situated immediately over Professor Ionedes' flat. From all appearance, the glass skylight had not been touched for years, for the panes were dusty and grimy, and the woodwork fitted into the roof almost as if it had been fixed there. Paradine told himself that it was no business of his, before he recollected that the Professor was quite alone, that he was elderly, and that something might have happened to him. If this was the case, and the front door was closed, then it would be impossible for anyone to enter from the outside in the ordinary way. Reflecting on this, and the necessity for something to be done at once, Paradine bent down and devoted all his energies to raising the skylight. It gave way presently with a sudden jerk, and Paradine found himself looking down through the water-tank into a small sort of store-room below, which appeared to be empty, save for a few packing-cases and something that looked like a human form sprawling on the floor. There was no ladder leading from the roof into the room below. If there had been one, the Professor would probably have had it removed. As Paradine's eyes became accustomed to the same gloom, he saw the figure down there gradually raise itself, and a white, pleasant-looking face was turned eagerly upwards.

"What are you doing there?" Paradine asked.

"Well, I hardly know," the stranger replied. "Who do you happen to be, anyway?"

"Isn't it for me to ask questions?" Paradine said dryly. "I happen to be the occupant of one of these top flats. My name is Paradine, at your service."

"Very pleased to hear it," the man at the bottom of the shaft said thankfully. "If you wouldn't mind reaching down and giving me a hand, I'll come up and explain."

"Well, I think not. Not just at present, anyway. You see, I happen to be top dog for the moment, and, until you can convince me that my policy is wrong, I propose to remain so. You see, I know something of Professor Ionedes, on whose premises you are at the present moment, and, frankly, my dear friend, appearances are decidedly against you. Now, Professor Ionedes lives entirely alone; he is an old man, with a rooted aversion to visitors, which is, perhaps, inspired by the fact that his flat is full of gold coins, which take up little space, and are always worth their face value in the precious metal. Moreover, I know that no one could leave that flat without the Professor's sanction when once the steel-lined front door is closed. Therefore, when I find a stranger—even a well-dressed stranger with a charming manner like yours— attempting to leave the flat by such a dubious method as the skylight, my suspicions are naturally aroused. For all I know to the contrary, you may have murdered that picturesque old numismatist for the sake of his coins, and found yourself in a trap afterwards. Such being the case, I must decline."

"For Heaven's sake, listen to me!" the other man burst out. "I am not going to deny that part of what you say is true. I am not going to deny that I am cut off here, and that I am trying to escape by means of the skylight. I piled up some of these cases on the floor, and, when I was balancing myself on the top of them, the whole contraption collapsed and let me down badly. That was the noise that you heard. But when you accuse me of murdering the Professor, then you are talking absolute nonsense. As a matter of fact, he's not in the flat at all. I came here this evening to see him by appointment, and, after ringing the bell two or three times, a man came to the door."

"What sort of a man?" Paradine asked.

"A tall, dark chap getting on in life, with black hair and beard. When I explained my business to him, he asked me into the dining-room, and told me that the Professor would see me in a few minutes. Then he put some fez arrangement on his head and walked out of the flat, banging the front door behind him. I waited a quarter of an hour, and, after ringing the bell two or three times, it dawned upon me that something was wrong. So I started to explore the flat, and found that the place was absolutely empty. There wasn't a soul on the premises, either in the bed- or living-rooms. And when I tried to get out, and spotted that steel-lined door, with its spring lock, I knew that I had been trapped by some thief whom I had probably interrupted when I rang the front-door bell. I knew then that I was in a tight place, and when I found that one of the Professor's most valuable coin cabinets had been broken open, I was aware of my danger. When I recovered myself, I cast about for some means of escape. I knew I shouldn't be believed, I knew that I should be accused of taking what was missing from the cabinet, and that's why I hit upon the desperate expedient of getting away by the medium of the roof, and trusting myself to reach the street through the help of another flat, without being discovered. And that's the Gospel truth. Perhaps, if you weren't wearing a Bullingdon Club tie I shouldn't have the courage to tell you this."

"Oh, you were at Oxford, too?" Paradine asked.

"I was. Name of Felton."

"Not the Jimmy Felton?"

"The same, worst 1uck to it. And, now I come to look at you, I see a strong likeness to the chap that we used to call Tomahawk Paradine. Am I right?"

"I've heard worse guesses," Paradine said. "But look here, I can't take your word for all this, you know. You may have gone to pot, for all I know to the contrary. You might have taken to burglary as a profession."

"Oh, yes, I can see all that, of course. But I'm telling you the truth, Paradine. If you don't believe me, come down and see for yourself. Bring a revolver with you, if you like. Anyway, you won't find the Professor here."

Paradine weakened suddenly.

"All right," he said. "I'll take your word for it. Now, hold out your hand, and I'll give you a leg up."

The man called Felton scrambled to the roof with a sigh of relief, and sank breathlessly into an arm-chair. He availed himself generously of Paradine's invitation to sample the contents of the tantalus, and lighted a cigarette.

"Don't you want to go over the flat," he asked, "and satisfy yourself that the aged Professor is not weltering in his own gore? In other words, are you satisfied?"

"Well, partly," Paradine said. "If there had been any violence, you would not be sitting in that chair talking to me in this collected way. If there is anything wrong, you would be only too anxious to get away."

A deep groan burst from Felton's lips.

"As a matter of fact, I am in no end of a hole," he said, " and I want you to help me out, if you can. In fact, no one else can save me; and, upon my word, I don't believe even you can when the truth comes to be told."

"Let's have it," Paradine said encouragingly.

"Well, it's like this. I also am a collector of coins in a modest sort of way, and, without flattery, there are only two men in the world who know more of what I might call pre-numismatism than I do. Professor Ionedes is one, and a queer sort of semi-Arab Johnny called Ali Khan is the other. I have never met Ali Khan, but, in the light of events during the past hour or two, if he isn't the chap who let me into old Ionedes' flat, then I'll eat him, fez and all! But I'm getting on a bit too fast. Do you know anything about coins, Paradine?"

"Nothing whatever, I am sorry to say."

"Then I'd better explain. Now, I suppose Professor Ionedes' collection is absolutely complete as regards the gold coins extant before the beginning of the Christian Era. Ionedes has every one of the coins. There is only one gold piece that he lacked up to a year ago, and this he found in a mummy case whilst exploring in Egypt a few months back. He was exploring the same pyramid that Ali Khan was working on—in fact, they were both looking for that particular medallion that has been a tradition amongst numismatists for generations. And the Professor found it. Ali Khan said that the Greek found it before it was lost— in other words, they were both on the same track, and the Arab was beaten by a short head—a matter of seconds, I believe it was. Anyway, there was a fierce quarrel that nearly ended in physical violence. You will see why I tell you all this presently."

"Go on," Paradine said encouragingly.

"Well, the coin in question is called a Di-Drachma. It is a small gold disc with the figure of a turtle on the obverse side, and on the reverse a design that is not unlike the fifth proposition of the first book of Euclid. It is a Lydian coin, and, experts say, the first token in gold ever struck in the world. When I tell you that there is no mention of coinage throughout the whole of the poems of Homer, you will be able to get some idea of the age of the coin. It was probably struck by Pheilon of Argos in B.C. 895. I don't know what the turtle means, but it is a symbol of some kind, of course. And this is the coin that numismatists have been trying to find for ages. And Ionedes has it, beyond the shadow of a doubt. When I say has it, I ought to have said had it, because it is no longer in his collection."

"How do you know that?" Paradine asked.

"Because it's gone, my boy, vanished— stolen from its place in the drawer by that blackguard Ali Khan, who opened the flat door for me, and subsequently shut me in. I told you that, when I found out how I had been trapped, I went all over the flat and found, amongst other things, that one of the Professor's cabinets had been forced open. In the space amongst the Lydian coins which was obviously reserved for the precious Di-Drachma in the cabinet was nothing but a pad of cotton-wool, and therefore I came to the conclusion that I had interrupted Ali Khan just at the moment when he had laid his hand upon the coveted coin. The old rascal was cunning enough, when he saw how the land lay, to make a clever exit, and leave me to face the infuriated Professor when he came back. Of course, he would swear point-blank that he had never seen me before, that he had never been in Ionedes' flat, and that my story is an absolute fraud. Now you see the position Fate has placed me in, and why I was so anxious to crawl out of the flat at any risk. But, of course, things can't stay as they are, and, at the same time, nobody would accept my explanation. Nothing would convince the Professor that I haven't stolen his Di-Drachma and cunningly hidden it till it was safe for me to go and pick up the beastly thing again."

"In fact, couldn't be worse," Paradine suggested.

"Oh, couldn't it? That's all you know about it. It can be a jolly lot worse. Look here!"

With which Felton produced from his pocket a roughly-cast gold coin of small size, bearing on one side the imprint of a turtle and on the other that of an irregular parallelogram. This he handed over for Paradine's inspection.

"This is the genuine Di-Drachma he said. "There can be no shadow of a doubt as to its authenticity."

"Then you did steal it, after all," Paradine exclaimed. "In that case, why did you tell me "

"Here, half a minute, old man. I am only proving to you how it can be ever so much worse than you thought, because that coin belongs to me, and I had it in my pocket when I called on the Professor this evening. What do you think of that?"

"Well, frankly, I don't, believe you," Paradine said bluntly. "Dash it, man, you can't expect me to swallow a story like that. You tell me that there is only one Di-Drachma in the world, and then you calmly produce another from your pocket, like a conjuror juggling with a couple of rabbits. And, moreover, you tell me that the original gold token has recently been stolen from the Professor's flat. My dear fellow, what particular brand of ass do you take me for?"

"I knew you'd talk like that," Felton said resignedly. "But don't forget that I voluntarily produced the coin which is in your hand. I wasn't bound to do it, you know. I could have gone away without your being any the wiser on the subject. But, because you have trusted me, I have put all the cards in this exceedingly complicated game on the table."

"That's true enough," Paradine admitted.

"Very well, then. Now, perhaps, you will let me go on. I bought that coin, strange as it may seem, from a little general shop in a back street leading off Theobald's Road. I bought it about a week ago. It is a tiny shop, where they sell dilapidated second-hand furniture and cast-off wardrobes and things of that sort—a dirty, dingy little place, where obviously the proprietor was struggling hard for a bare living. In fact, there was a sale going on at the time, under distress for rent. I happened to be passing by, and I looked in, and in a box of rubbish, tokens and cast-off medals, I lighted on that coin. To make a long story short, I bought the whole lot for half-a-crown. Oh, it's a genuine Di-Drachma, right enough, and you can imagine my delight when I discovered the value of my treasure. As soon as I had satisfied myself that it was genuine, I wrote to Professor Ionedes, and asked him if I might be allowed to have a sight of his famous Lydian token. Of course, I didn't mention what I had got, and in the course of a day or two I had a post-card from him, asking me to call upon him this evening at six o'clock. In the light of what I told you, it is quite evident that he forgot all about the appointment, or, what is much more probable, he was lured away from his flat by that scoundrel Ali Khan, who had all his preparations made for the robbery, which' he successfully accomplished. The rest you know. And now you can believe me or not, as you please. I admit everything is against me, I don't suppose that I shall be able to produce the man from whom I purchased that disc—he is probably lost sight of by this time—but I have told you my story, and I am going to ask you to help me all you can. What do you suggest I'd better do?"

"Oh, I don't know," Paradine said. "Are you prepared to leave this token in my hands?"

"Certainly, if you like. But what do you gain by that?"

"Well, it's a guarantee of your bona fides, for one thing. This matter will take some thinking over. You'd better give me your address where I can write to you, and I'll see the Professor for you in the morning. If we do anything in a hurry, the worst construction will be put upon it, and you may find yourself answering a charge at Bow Street. You leave it to me. I dare say I shall think of something."

But morning found Paradine still in two moods, and it was nearly lunch-time before his housekeeper came to him with an intimation that a gentleman wished to see him. In his dining-room he found a little man with nice manners and much politeness, who introduced himself as Inspector Close, from Scotland Yard, coupled with the information, pleasantly conveyed, that he was armed with a search warrant, and that he proposed to go over the flat, with a view to finding a gold coin which was missing from the residence of Professor Ionedes next door.

"I must tell you, Mr. Paradine," he said, "that this is a most unpleasant business, and I am bound to tell you, moreover, that, unless I am satisfied, I have a further warrant for your own arrest. But no doubt—"

"It can't be done," Paradine exclaimed. "I've got a most important consultation at five o'clock this afternoon, in connection with a patient who is lying dangerously hurt in a private hospital off the Brompton Road. I am a brain specialist, as you know, and the whole thing was fixed up on the telephone only half an hour ago."

Inspector Close smiled as the god in the car might have done. It was not a pleasant smile.

"It might be done," he said thoughtfully, "but it rests entirely with yourself. The Professor doesn't want to prosecute, if he can help it, and he is prepared to listen to any story, however improbable, if he gets his missing disc back. You see, it's like this, sir. Nobody can get into the Professor's flat without his own key, which is never out of his possession. He went out yesterday afternoon, intending to return at six o'clock, and when he came back, after being detained, he let himself into the empty flat, the door of which was properly closed, and evidently had been untampered with. Despite this fact, a cabinet had been forced open, and a unique coin extracted—in fact, the only specimen of that coin in the world. The Professor promptly telephoned to Scotland Yard, and I was sent round to investigate. It did not take me many minutes to discover that the flat had been entered through the skylight by someone who obviously had access to the roof. Now, your flat alone gives access to the roof, and the thief must have used your flat for the purpose of the robbery—in fact, it could have taken place in no other way. But, of course, if you can prove your innocence "

The detective shrugged his shoulders and paused eloquently. Paradine stood there, trying to grasp the points of this new and unexpected situation. It was all the more complicated by the fact that at that very moment he had the Di-Drachma in his waistcoat pocket. Nothing would be gained by the detective searching the flat, he knew, but if the officer of the law insisted upon taking him round to Bow Street, then the murder would be out, and nothing could prevent him standing his trial on a charge of stealing the coin. Just at that moment he was regretting at the bottom of his heart that the goddess of Chance had brought him in contact with Felton. For the next minute or two he did some pretty quick thinking, then he plunged his hand into his pocket and produced the gold coin.

"Is this what you are looking for?" he asked. "Because, if you're in search of a gold Di-Drachma, then this is one, beyond the shadow of a doubt. I don't know whether you would like to listen to my explanation or not—probably you would not believe it in any case—so, if you want me to accompany you as far as Bow Street, I am quite prepared to do so. But I must say that I have never been inside Professor Ionedes' flat, and that I decline for the moment to say how that coin came into my possession. Perhaps, on the whole, for the moment I had better say nothing. I am thinking at the present moment more about that case of mine. Now, if I am charged with that robbery, is it possible for me to get bail? I only mean till to-morrow morning, because I must go down to Brompton Road, as a human life probably hangs on my attendance."

"I think that will be all right, sir," Close said. "There could be no possible objection on the part of the police to accept bail for the appearance of so well-known a gentleman as yourself. I suggest that you write a note to a friend or two, asking them to come round to Bow Street this afternoon, and I will see that the notes are delivered. Probably, when Professor Ionedes gets his coin back, he will not be disposed to prosecute, in which case you will hear no more of the matter."

It was four o'clock in the afternoon before Paradine emerged from the seclusion of a whitewashed cell into the open air, accompanied by two indignant scientists of his acquaintance and an apologetic groveller in the person of Felton, who offered to do anything up to suicide, if by so sacrificing himself he could put matters straight. So far, nothing had been seen or heard of the Professor, and it was quite uncertain as to whether he would turn up in the morning to substantiate his charge or not, though Inspector Close was of the opinion that, as he had got his coin back, nothing further would be heard of the matter. Paradine listened calmly enough.

"Oh, don't worry me," he said to the distracted Felton. "If I hadn't been a good-natured fool, I should never have found myself in this mess. And, besides, I've got other things to think about. I must be off to Brompton Road now, in any case. If you want to help, the best thing you can do is to go plunging around and see if you can hit upon the track of that picturesque Arab who has been the cause of all the mischief."

With which, Paradine dismissed the whole thing from his mind, and made his way as promptly as possible in the direction of the Brompton Road and the private hospital there. For the moment, at any rate, he had put the whole of the trouble out of his mind, and was thinking of nothing else besides the interesting case which was waiting his attention. A flippant-minded surgeon, with a watch in his hand, met Paradine on the doorstep.

"You're a nice chap," he said. "I've been waiting for you for a couple of hours, with my own patients performing solos on the telephone every two minutes. Been lunching at the Carlo, I suppose, or something equally important.'*

"Weil, not precisely," Paradine said grimly. "Here, sit down and tell me all about it."

"He's a foreigner," the other man said. "Picturesque, middle-aged ruffian with a black beard. He was knocked down last night, somewhere in Kensington, by a motor lorry, and taken to St. Jacob's. The house-surgeon there saw that it was a case for you, and telephoned to know if he should send the chap round here. So they brought him on a motor ambulance, and he is upstairs at the present moment. I've been all over him myself, but for the life of me I can't find anything wrong anywhere. There are no bones broken and no signs of a fracture, but the man's unconscious and absolutely paralysed. The funny thing is that his colour is quite good, and his pulse and heart quite normal. And now I must be off."

It was quite a couple of hours later before Paradine had completed his diagnosis of the unfortunate patient. He was an elderly man, with clean-cut features and square, fighting jaw, an Eastern beyond question, as his swarthy complexion and black eyes testified. Paradine was not easily puzzled, but for a long time the source of the trouble baffled him. Then he went over all the ground again, and presently the frown lifted from his forehead, and he smiled.

"Ah, here it is," he said, turning to one of the nurses who was holding his instruments. "A small matter enough, but quite sufficient. There has been an injury to the spine right at the base of the brain, a minute displacement of the vertebrae. There's a hole there you can put your finger into. The brain itself is untouched."

"Are you going to operate?" the nurse asked.

"Perfectly useless," Paradine replied. "If that poor fellow moves half an inch, he will be dead. I can remove things, but no surgeon ever yet could replace an injured bit of spine. He is literally hanging on a thread. As I said just now, as soon as he moves he's done for. You'd better go through his belongings and communicate with his friends. Were there any letters or anything of that kind on him?"

"They are on the table there," the nurse explained—"one or two letters, evidently from some scientific society in the East, together with a watch and chain and a purse and a little case with a gold coin in it."

Paradine reached over eagerly and grabbed the shabby little leather case that lay on the table. He threw back the lid with trembling fingers, and there before his astonished and delighted eyes he saw a Di-Drachma. There was no doubt about it; the thing had been burnt too deeply in his memory for him to make a mistake. There it lay, with the imprint of a turtle on the one side and the crude mathejnatical design on the other. Beyond the shadow of a doubt, by sheer good luck Paradine had found the stolen medallion, and was looking down into the unconscious eyes of the thief himself. For beyond question Ali Khan was lying on the bed there, stricken down with mortal illness, no doubt inflicted upon him at the very moment when he was hurrying off from the Professor's flat with his ill-gotten gain.

Five minutes later Paradine had called up Felton on the telephone, and was hurrying back homewards as fast as a taxi could carry him. He had hardly rid himself of his glossy hat and immaculate morning coat before a pale and dishevelled Felton fell headlong into the dining-room.

"Mean to say you've found him?" he gasped.

"I have," Paradine said, " and only just in time, too. It was a bit of sheer good luck. And upon my word, after all that has happened, I think we deserve it. As I told you this afternoon, when we were leaving Bow Street, I had a most important appointment at a private hospital in Brompton Road—a foreigner knocked down in Kensington High Street and seriously injured by a motor lorry. I went to see if an operation would be any good; but the patient was past all that kind of thing, and it's any odds he's dead by this time. I told the nurse in charge that I could do no good, and advised her to communicate with the man's friends. She showed me his letters and belongings, and also told me that he had been possessed of an old gold coin that he carried in a leather case. As I am particularly interested just now in old gold coins, I asked to see it. Here it is. I took the liberty of bringing it away with me, and if it isn't the Professor's missing Di-Drachma, then I am cruelly mistaken. What do you say?"

"Beyond the shadow of a doubt," Felton cried. "What blind good fortune that you should have been called in to attend the actual thief! Oh, that's the coin all right. Then I suppose the next thing is to go and see the Professor, and convince him that he has got my coin, and that this is his. He won't believe it unless we produce the actual token. So let's get along and finish it without delay."

It was some little time before the suspicious Professor, doubtless with the fear of violence before his eyes, consented to open his front door wide enough to admit the two intruders, and, indeed, he would probably have refused then had not Paradine produced the second coin and dangled it before his astonished and crestfallen gaze.

"Yes," he said, "that is a genuine Di-Drachma all right. And I thought that there was only one of them in the world—I mean the stolen one, which is now safe in my cabinet again. But please come inside, gentlemen, and let us talk this matter over."

At the end of half an hour the Professor expressed himself satisfied, though he still looked uncomfortable and ill at ease as he made the necessary exchange of coins, and, with a reluctance which he made no effort to conceal, handed Felton's property over to him.

"I suppose that that rascally Arab must in some way have obtained an impression of the key of my front door," he said, "otherwise I cannot account for the way in which he got into my flat. It is an extraordinary story altogether, and, but for the evidence in Mr. Felton's hands, I would never have believed it. To think that two of those coins were in existence! And the worst of it is that the value of mine is depreciated at least one half by the fact that there is a counterpart. Only a numismatist like Mr. Felton can understand my feelings. Now, Mr. Felton, I'm a rich man, and able to gratify my whims. Shall we say five thousand pounds for your Di-Drachma?"

"Done!" Felton said promptly. "It's yours."

It was a highly delighted Felton who followed Paradine into his flat a few minutes later.

"Funny story, isn't it?" he said. "Pity it can't be written, isn't it?"

"Nobody'd believe it if you did," Paradine replied, "and, if you ask me, you are jolly well out of it."

The door opening into Oldaker's sitting room opened and a figure crept in. Then the door closed, and a woman stood with her back to it, swaying slightly with her hand to her side as if she were short of breath. Visions of Charlotte Corday crossed Oldaker's mind. He looked for the quick gleam of a revolver, but none came. The woman moved a step forward with a quick movement, and threw off her long wrap. There was something dramatic about it.

"Princess," Oldaker exclaimed, "Princess Elizabeth of— What in the name—?"

"Betty," the Princess corrected eagerly. "Know that I am in the deepest trouble, my dear—Dick."

Something warm and rapturous played about Oldaker's heart. He was young and romantic; he was an Oldaker of Barons court, and the princess was beautiful. She must have known that herself, for Dick had told her so several times lately. They had seen a good deal of each other at Monte Carlo, and Dick had begun to dream dreams. And when one of the most daring and successful of aviators begins to dream dreams, he is in a bad way.

He knew he had no business to be in the Asturian capital at all. To suggest that the aviation ground there was better than a score of others was ridiculous. Besides, there was trouble brewing in Marenna. The Progressives looked like getting the upper hand, and King George had gone to Merum at a most critical time. Even his own followers were muttering of cowardice under their breath. There were many more delectable spots in Europe than Marenna just now. Still, Princess Elizabeth was there.

She came close to him, and laid her hands on his shoulders. It was a sweet, dainty pleading face, and there was something in the expression of it that set Dick's heart beating madly. And the glint in that golden hair!

"Dick," she said softly. "You love me, don't you?"

Princess or no princess, there was only one thing to do after that. Dick had the slender, palpitating figure cuddled up in his arms, his lips were pressed to hers. There was something intoxicating in the fragrance of the spungold hair.

"I've done it!" Dick smiled presently. "Good Lord! my cheek! I shall have to go away, Betty. King George—"

"I knew I should have to ask you," Betty smiled demurely. "My dear boy, the situation is not quite so original as you suppose. Besides, there were Oldakers in Baronscourt long before the Asoffs came to Asturia. And on your mother's side you are related to the wealthiest financiers in Europe. Even if only on that score—"

"Yes," said Dick, thoughtfully. "I've got a tidy chunk of bullion. And ever since we first met—"

"Yes, I know, dear; you loved me. And I loved you, Dicky. And I always get my own way—always."

"And so you came here this afternoon—"

"I came because my sister, the queen, is in great distress. They say that George has fled to Merum. He had to go there."

"Never heard that King George had been accused of want of pluck before, Betty."'

"My dear, the poor man is as brave as you are. They are an artful lot, those conspirators. They have stirred up a nest of trouble both here and at Merum. When George is at Merum Marenna thinks he has gone away into hiding, and when he is here, Merum thinks he has deserted her."

"But no man can be in two places at the same time, Betty."

"There, my dear Dick," she said demurely, "is where I fail to agree with you. If the king could be here at midnight the situation would be saved. He wants to come here secretly and quietly at a moment when the conspirators are absolutely certain that he is at Merum. Then news must come from Merum that George is on his way here. In the ordinary way it would be a matter of hours. And then within an hour or two of striking hard here he must be at Merum again. Consider the paralysing effect of the whole thing; look at the dramatic possibilities of the situation."

"But, my dear Betty, it is a physical impossibility. It can't be done!"

"Really, Dick? Can't you see the way? I have sent a message to the king. He will expect you. And you will get him here before midnight, and back to Merum before daybreak. And you, above all men, tell me it can't be done."

"It is fearfully risky," he said. "In the daytime I should think nothing of it. But as you point out, daylight for our purpose is useless. It's the striking moral effect you're after. You deal a staggering blow in two places at once. And to leave the foe marvelling how it is done is the way to final victory. But it's dangerous, Betty."

The Princess looked grave and troubled. There was a suggestion of tears in her eyes.

"I know it," she said. "Ever since the idea came to me I have struggled against my own feelings. I am pulled this way and that. If—if anything happened to you, Dick—"

"Don't think of that for the moment, dear," Dick said tenderly. "Go on."

"Well, I felt bound to ask. And you are ready to go. I hoped you'd say no and yet I'm awfully proud and glad to find you so willing. George's whole heart is in his work and my sister, the Queen, loves her people. It would break her heart if anything happened. George must be here tonight. I don't say he is being actually kept a prisoner at Merum, but there are obstacles placed in his way—trouble on the line, a sudden breakdown in the garage. You understand."

"You can communicate with the King?"

"My dear, I have already done so. By secret code. George knows exactly what I am proposing to you. He will be all ready. The great light in the castle at Merum will be your guide. Between the Tower and St. Simon's church, where there is an illuminated clock, are gardens, great gardens laid out in the Italian fashion ages ago. If you make no noise—"

"Oh, I shall make no noise. You should see my new engines. I suppose King George has a few people he can rely upon to keep silence."

"Oh, there are plenty of them, Dick. Then you'll do it?"

"Of course I'll do it, darling."

The Princess kissed him tenderly.

"You're a hero," she whispered. "My hero, and I'll marry you though all the armies in Europe try to stop me. There never was any man but you, Dick, from the day we met. And you are going to save Asturia. If you can do this thing there will be no more trouble here. And you will come back to the castle with him. He may need your services. And I would like to know that you are safe."

She slipped her wrap over her head again and vanished. The happiest man in Europe lighted a cigarette. He had promised to enter upon a mad enterprise. And he was not in the least afraid. When the gods throw a beautiful Princess into the arms of a mere mortal man it is clearly up to them to see the business through.

* * * * *

It was pitch dark and the hour near ten when Dick Oldaker picked his way through the Italian garden on the west front of the castle at Merum and fumbled in the direction of a lighted window on the ground floor. The window was open and Oldaker slipped through without hesitation. He dropped the blind back in its place and looked around him. From an American desk a man in uniform arose and approached the intruder with outstretched hand.

"You are the bravest man I ever met, Mr. Oldaker," the King said. "I congratulate you and I congratulate—the Princess Elizabeth. Oh, yes, she has told me everything. I shall not interfere. An Oldaker of Baronscourt is a fit mate for an Azoff any day. You had a safe journey?"

"Absolutely, your majesty," Dick replied, "My monoplane got here in an hour. There was no mishap at all. Your men appear to be discreet and silent. They did exactly as I told them."

The King, paced thoughtfully up and down the room.

"It is wonderful," he said. "Wonderful! With ordinary good fortune I shall strike two blows before daybreak that will end the trouble once and for all. When can we start back?"

"I am ready to start at this moment, your Majesty," Dick replied. "I have brought with me everything that is necessary for you in the way of clothing. The sooner we start the better."

"Then I will join you in the garden in ten minutes," the King replied. "I am supposed to be leaving for my capital at once by coach. The trains are broken down, there is no motor to be had. I shall merely go in my coach as far as the gates and then slip out, leaving the vehicle to proceed. I have a few faithful followers in the secret. Directly I am on my way the traitors in Marenna will be advised that I shall reach my capital some time tomorrow. Long before daybreak I shall be back here to deliver the second blow. I shall have the rascals yet."

Dick murmured his approval of these suggestions. Ten minutes later the King joined him in the garden. As the clocks at Marenna were on the stroke of midnight an astonished lackey staggered backwards as he saw the King come softly along the corridor of the Palace. The miracle had happened.

"Not a word," the King commanded. "Not a word to a soul as you value your liberty. Where is Nikolof and the rest of them. Tell me?"

The menial stammered something about the council Chamber, and the King strode on. A door at the end of the corridor opened, and a white face looked out. The face smiled dazzlingly and the blue eyes filled with happy tears as they fell on Dick.

There was a wave of the hand and the door closed again. Dick staggered along with his head erect and his heart swelling.

"Where shall I wait for your Majesty?" he asked.

"You shall come with me," the King said. "You shall see what you shall see. At any rate you'll see that your part has not been in vain."

The stream of the adventure was running bankful. Oldaker plunged into it with wholehearted joy. There was the uplifting sense that he was helping to make history. A little knot of men for the most part in uniform were gathered round a table illuminated by one shaded bunch of electrics.

The rest of the big gloomy apartment was in darkness. The King strode forward and grasped the neck of the man who sat with his back to the door, and dragged him from his seat.

"Who sits in my chair?" he cried. "Who but the twice-pardoned Lipski? So this is how my faithful ministers labour in my absence? What is the document you are considering? Oh, coquetting with Teutonia, are we? Rise, all of you. Mr. Oldaker, would you be so good as to pull back those curtains and open the window?"

A clock ticked heavily in the painful silence, the metallic jingle of the curtain rings as they clicked back sounded like pistol shots. A ring of pale-faced men stood round the table, silent, disconcerted, incredulity in their downcast eyes. Oldaker turned to the great quadrangle below the open window. In the velvet violet night electric lights gleamed everywhere, the streets were full of people, the theatres and halls were emptying. Suddenly the council chamber blazed with light, the brilliant uniforms were picked out from the street like striking stage pictures. The King, with his hand still on Lipski's neck, impelled him towards the window.

"You traitor," he cried. "Traitors every one of you. And so you tell my people I am deserting them while all the time I am at Merum fighting the rest of your gang. You thought that I was there still, that I could not possibly get away. But there are ways, there are ways."

The King's voice was pitched high, every word he said was carried to the street below. The roadway was blocked now by a breathless, hustling crowd. King George pushed the flaccid Lipski into the window recess and held him there. A ripple of cheers broke from the crowd below, it swelled into a deafening roar, it stopped as suddenly as if it had been cut with a knife. The star was on the stage and the audience eager to hear him.

"Behold a traitor," the King cried. "Lipski, whose life I saved. Behold the other liars cringing in the background. And these are the men by whom you were asked to choose someone to take my place. I hope you are proud of them. But I am back, and I am back just in time."

As the King paused, a vast sigh went up from the street, a sigh, and no more.

"They called me pleasure-loving and easy-going. It is a lie. Was I easy and pleasure-seeking for ten whole years when I lived in a tent defending my frontier and never during that time slept in a bed? For the Queen's sake I slacked the bow and took the month of holiday that I was conceited enough to feel I had earned. I was wrong."

A storm of protest broke from the street. The King smiled, and in that moment Oldaker knew that the battle was won. George whispered a word in his ear. Oldaker came back from the table a moment later with the secret treaty in his hand. The King crashed it down on Lipski's head so that the paper broke and hung round the traitor's neck like a ham frill. The crowd below rocked with mirth.

"Take him," the King cried, "and treat him as he deserves. We have done with him here."

He raised Lipski in his arms as if he had been a child and tossed him through the window. He fell into a thicket of laurels below. There was a wild rush in his direction as King George slammed the window down and pulled the curtain across.

"They will be making jest of this in the music halls to-morrow. Lipski's power has gone. Nothing kills a political reputation more than ridicule."

"And what shall I say to the rest of you?" he demanded. "Is there not one honest man among you? You thought I was no more than a blunt soldier unskilled in the ways of diplomacy. I was the Mars who had forsaken his arms at the call of Venus. I was warned against Lipski, but I trusted him. And when I came to my senses it was nearly too late. But for this brave and gallant gentleman here I should have been too late. It was he who solved the problem whereby I could be in two places at the same lime. Before daybreak I shall be back at Merum and Staffanoff will come with me to bear testimony to the truth of what I say—"

An old faded grey man in the background shuffled uneasily. A gentle bead of perspiration glistened on Staffanoff's great bald head. His dark eyes moved shiftily.

"Sire," he stammered. "If you will allow me to explain."

"No explanations," the King thundered. "These are your marionettes, but your's the cunning hand that pulls the strings. Come with me to Merum."

Staffanoff cringed and fawned. The King crossed the room and rang the bell. A moment later the room was filled with armed men. With a contemptuous gesture the King indicated his unhappy councillors.

"Take them all save Staffanoff," he commanded. "They are prisoners, and shall be treated as such. They are not to see anyone except the gaolers. Now go."

The room was empty presently save for the King and Oldaker and Staffanoff. The latter stood there with bent shoulders and a frame shaking like a leaf.

"I am an old man, sire," he groaned. "A very old man, your Majesty—"

"As if that is any excuse," the King cried. "You are coming with me to Merum, and in my presence you shall tell your fellow conspirators the story of this fiasco. You have room for another passenger, Mr. Oldaker?"

"More if necessary, sir," Oldaker said, "But one of the sort is enough."

"Good. Then follow me in the grounds, Staffanoff. Wrap yourself up well for the journey that is by no means a warm one. Here, my friend. You are no longer puzzled. Get in."

Staffanoff stood there in the darkness shaking with terror.

"But it is madness, your Majesty," he protested. "I am an old man—"

"And therefore you should not mind, Staffanoff. It is madness like this that has saved Asturia to-night. Come, get in, unless you would he gagged and bound first. Get in, I say."

It was nearly two hours later, and the scene had shifted to Merum again. There was the council chamber, another little knot of conspirators gathered round the table. The King took the hoary old traitor by the shoulders and sent him spinning into the room. A hoarse cry came from the table.

"Staffanoff," the leader muttered. "How did you get here? The King is on his way to Marenna. It is impossible for him to reach there before, well, before it is too late. Is there anything wrong?"

"Everything is wrong," Staffanoff stammered. "The King has been to Marenna—"

"Oh, the man is mad," another cried. "Three hours ago the King was here. He—"

"I tell you I am speaking the truth," Staffanoff shrieked. "Gentlemen, we have failed."

"Failed, then in that case the treaty with Teutonia—" The speaker broke off abruptly, his jaw dropped. For the King was in the room with eyes turned with contempt and yet full of cynical mirth upon him.

"Tell him where the treaty with Teutonia is, Staffanoff," he mocked.

"Hanging in tatters round Lipski's neck," Staffanoff whined. "And Lipski is in the hands of the mob in the street who mocked and jeered him. All Europe will be laughing at us to-morrow. They will make us into a vaudeville for the comedy stage. Lipski as the chief clown of the piece and the rest of us will be low comedians. The King was there. The King threw him out of the window to the mob below. And, heavens, how they laughed! And the rest of them are all under lock and key."

A quivering silence followed. There was that in Staffanoff's face, and the palsy of his voice that carried conviction to the most cynical spirit there. Not so long ago they had seen the King on his way to Marenna; at the earliest possible time he could not reach the capital before daylight. And yet he had been there and back again. What unknown force had he called to his aid. Oldaker could have told them, but there was no one there who associated the silent Englishman with this miracle.

The faint grey dawn was breaking in the east as Oldaker stood alone with the King. Something in the way of a belated supper was waiting for him in a private room. The King raised his glass.

"Here's to our friend. Oldaker, the saviour of Asturia," he said.

"I am afraid I cannot make that claim your Majesty," Oldaker said modestly.

"Oh, yes, you can. Without you and your Grey Bat I should have been powerless. Here's to the Grey Bat, the most wonderful aeroplane that was ever made by man—the Grey Bat that flew in the dark and never made the semblance of a mistake. The gallant little craft is safely housed again? And we can trust our faithful allies to keep the secret. Good again. A fine night's work, Oldaker, and an adventure after my own heart—and yours. And here's to dear little Elizabeth who suggested the whole scheme. And may you be as happy with her as you desire. Did I hear the telephone?"

A servant came in with a message for Oldaker. He was wanted by Marenna. The sun was shining brightly and the birds were singing as Oldaker crossed the hall.

"Is that you, Dick?" a sweet voice asked.

"Elizabeth," Oldaker responded. "Well, then Betty. My Betty! You are well and safe?"

"I am well and safe," the sweet voice said. "I want to tell you that I shall be waiting in the Palace Gardens this afternoon to see you, and—and, oh, my dear, my dear—"

WILFRED BARNES, eke of London University,M.D., looked despairingly out to sea. He was seated on the edge of a rotten verandah of a tumble-down bungalow on the margin of the Coral Sea down there, in the South Pacific, on the outer fringe of civilisation. In front of him was a stretch of white sand, with the whiter surf beyond, creamy and mantling in the sunshine, and behind him the swaying plumes of the palms, or, at least, they would have been the swaying plumes of the palms but for the fact that the little islet of Omolo lay in the centre of the anti-cyclone, and not a breath of air came to Barnes's almost atrophied lungs. He could feel the perspiration trickling down his forehead as he sat there cursing his fate and the imps of chance that had brought him all the way from London and Janet Blyth.

It was not his fault entirely. He had put his little capital into a practice largely built on bogus ledgers and apocryphal patients, so that, at the end of a year, instead of a comfortable living, with Janet by his side, he had found himself on the verge of bankruptcy.

When everything was disposed of, he found himself facing the world with a five-pound note, and looking a black future squarely into its forbidding eyes. Then, in a fit of despair, he had sold himself to Mark Gride, the eminent pathologist, for three thousand pounds. With the money went Barnes into practically three years' penal servitude, though he had not grasped it at the time. He had talked the matter over with Janet, and it had seemed to her that the opening was a good one. It meant, of course, three years' separation, with fifteen thousand miles of sea between them; but then Wilfred would be able to save every penny of the money, and, when he came back, be in a position to buy another practice more promising than the first one. And so Barnes had set his teeth grimly and come all that way to a little island on the edge of the Solomon Group, with the firm determination to make the best of things; and here he was, at the end of the first year, cursing his bonds and wishing, from the bottom of his heart, that Fate had never brought him in contact with the cold-blooded brute and unfeeling savage who was known to men as Mark Gride. Far better had he stayed in England and accepted a job as locum to some sixpenny doctor in the East End of London. And he had known something of Gride's reputation, too. The man in question had had a brilliant career at Cambridge and University College, where he had towered over his fellows like the intellectual giant that he undoubtedly was. But then he was ill-disciplined, intolerant, and brutal in his manner, and so callous in his methods as to bring him, in the course of time, before the Council of the College of Surgeons. There had been a pretty big scandal over some vivisection atrocities, and it was only Gride's amazing record that had saved him from professional disgrace. Fortunately for him, he was the possessor of ample private means, a mad enthusiast as far as his profession was concerned, a daring experimentalist and pioneer, and so it came about that he shook the dust of London from his feet and migrated to a region where he would be able to pursue his investigations in an atmosphere of greater freedom and less responsibility. And when he had offered the post of assistant to Barnes, the latter had jumped at the offer immediately.

The conditions were pretty stringent, too, though the pay was good enough. Barnes was to have three thousand pounds for three years' services, the money to be paid in one sum at the termination of the contract. If in the meantime Barnes decided to cancel the agreement, then he was to get nothing except his passage home. And if in the meantime anything happened to Gride, then the whole of the money was to be payable at once through the latter's solicitors in London, who had the necessary authority to deal with the case.

And then there followed for Barnes a year of hideous nightmare that racked his soul and filled him with the lust for slaughter a dozen times a day. For out there, in Omolo, Gride could do as he liked. He had his menagerie of beasts and reptiles, monkeys and the like, upon which he experimented with a cold-blooded malignity that amounted almost to mania. Indeed, in a fashion, the man was mad. He had no fear of the College of Surgeons before his eyes out there, and he seemed to revel in a refined cruelty which might possibly have been accounted for by the fact that between his spells of scientific research he had heavy bouts of drinking that brought him frequently to the verge of delirium tremens. The year was passing in a review before Barnes's eyes as he sat there, wondering if it was possible for flesh and blood to stand it any longer. A score of times he had made up his mind to quit the whole thing and return home without being a penny the better for all he had done. And then the vision of Janet would rise before his eyes, and he would grip his teeth and string himself to go on to the bitter end. Even then he probably might not have done so, had it not been for Denton.

This Denton was a cheery American naturalist attached to Columbia University, who was out there, in Omolo, studying the local butterflies. Perhaps he hated Gride as much as did Barnes, but his philosophy was a little wider than that of the Englishman; and, besides, the American was not called upon to take any part in those mumbo-jumbo rights and sacrifices of blood that Gride's seared and blackened soul revelled in. Still, he was a tonic to Barnes, and a sympathetic companion who kept him going from day to day.

He came on to the balcony now with a glorious puple-and-gold butterfly on the palm of his hand. It was a new and rare specimen, and his shrewd grey eyes twinkled as he contemplated it.

"Well, how are we getting on?" he asked cheerfully. "How's old Moloch this morning?"

"Infernally bad," Barnes said moodily. "He hasn't been sober for the last three days, though signs are not wanting that he is coming round. I've had a ghastly week, old chap—perfectly ghastly—an orgy of blood and cruelty that has made my very soul retch. And not a pennyworth of ansesthetic on the island, except the morphia that Gride uses to soothe his nerves after one of his outbreaks. I wouldn't mind if there were, but when I see those poor brutes—I tell you, Denton, I'm an infernal scoundrel to go on with it! And yet what can I do? I have sold myself for a price, and. Heaven knows, I am earning every penny of the money!"

As Barnes spoke, Denton jerked his thumb significantly over his shoulder, and a moment later Gride appeared. He was shivering from head to foot in spite of the heat, his strong, intellectual face was green and ghastly, his chin was dingy with a five days' beard. And yet, though he was racked and broken by the brandy he had been drinking, the man's mind was clear and vigorous enough, and his great, strong will was dominating his tortured body.

"You were talking about me," he said suspiciously. "Oh, I can guess what Barnes has been saying. Let him grumble as much as he likes, I've got him all right. He is a sort of Jacob serving for Rachel. Ha! Ha! Go in the house and mix me a 30 injection of morphia. We are going to be busy to-night, Barnes. You had better clear out, Denton, and don't come here again till I send for you."

"It's a cordial invitation," Denton drawled, "and I shall have much pleasure in availing myself of it."

The American sauntered off with the butterfly in his hand, and the ghastly wreck with a five days' beard turned angrily upon his unhappy assistant.

"You just drop that," he said. "I'm sick of your whining. You are my servant."

"Your slave," Barnes said bitterly.

"Well, perhaps that's a better word. My slave for the next two years to come, and don't you forget it. Not that I am complaining about the way you do your work. Why, good Heavens, man, there are scores of young doctors who would give their heads for a chance like yours! Look what I've taught you! Look what you will be able to teach the snivelling sentimentalists in England when you get back! And yet you whine and whimper because I put a knife into a strapped monkey, without an anaesthetic, as if he were a human being. Look at Crim yonder! Is he any the worse for what he has gone through?"

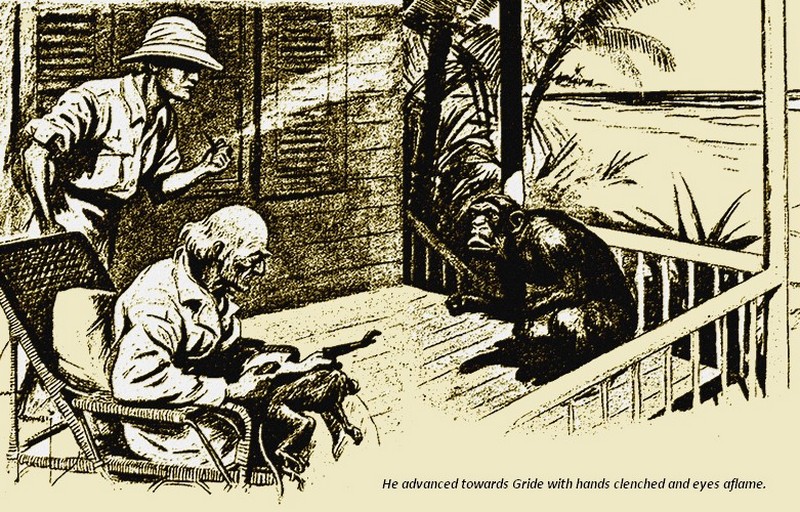

As Gride spoke, he pointed a trembling forefinger to a chimpanzee perched on the edge of the balcony. The monkey seemed to know by some instinct that he was under discussion, for he chattered and gibbered and scolded in Gride's direction. As a rule. Grim was mild-mannered enough, and for Barnes the intelligent beast had quite an affection. But Gride he hated at the bottom of his simian soul. He had known what it was to come under the Professor's knife, and even at that moment, as he turned, Barnes could see the recent stitches of a comparatively new wound between the ape's shoulders.

"I wouldn't drive Crim too far, if I were you," he said. "Some of these days he'll do you a mischief. And he's powerful enough to do so, despite his gentleness."

Gride laughed harshly.

"I've flayed him a score of times," he said. "He'll never do any mischief—he hasn't got pluck enough. And I am not going seriously to hurt the best subject I've got. Now go and get me that morphia, and I'll show you something presently that no pathologist has ever dreamt of before. I'm going to show you a new serum; I am going to show you an absolute certain cure for cancer. You know" what I've been doing with that little banana monkey Mini. She's full of it. I'm going to cut her throat —it's the only way of doing it—and then you will be part-discoverer of the greatest healing power in the world. And yet people whine and snivel over vivisection, and pretend that the whole of humanity had better suffer than some furry little beast should be tortured. Then I'll have a shave and a bath, and we'll open a case of champagne for dinner. Now, get a move on."

Barnes came out presently with a hypodermic syringe, and injected the morphia into the arm of his chief. In less than a minute Gride was a new man. The green tinge left his cheek, the haggard look faded from his eyes, he paced up and down the verandah with the air of a man to whom the secrets of continents are revealed. Then he went into his own operating-room, and came back presently with a tiny monkey in a cage. He had under his arm a small leather dressing-case containing a set of razors and the necessary implements of shaving. Then, without a word, he took the tiny simian from its cage and laid it face upwards on bis knees. With a hand as steady as a rock, he drew the edge of the shining blade across the monkey's throat. There was just a little gasping cry, with a creepy suggestion of humanity in it, and the tiny creature lay dead.

"Behold, you see there is practically no flow of blood," Gride said, in the tones of a man who is demonstrating some everyday problem. "Not more than a tablespoonful altogether. But the precious serum is there on the fur, and we can easily cultivate from that. Simple, isn't it?"

"Horrible, ghastly!" Barnes shuddered. "But look at Crim! Take care of yourself!"

All this time the chimpanzee had been watching the proceedings with an intelligence almost weirdly human. He hopped down from his perch and advanced towards Gride with hands clenched and eyes aflame with anger. Then his mood seemed to change, for be stooped and picked up the razor and ran his paw along the edge much as a man might have done who is in the act of shaving. He dropped the weapon again, and, with a quick, strangled cry, disappeared in the hanging foliage of a palm. Something seemed to grip Barnes by the throat.

He stood there, holding himself in hard and sweating from head to foot with the nausea and horror of it. Not that it was anything fresh, but there were moments of high nervous tension, one little episode piled upon another, till it seemed to him that he could stand it no longer. He saw Gride stoop, and with a surgical knife cut the little blood-stained patch of hair from the dead monkey's throat, and place it carefully in a tin specimen case, which he dropped into the pocket of his filthy dirty linen jacket, together with the razor with which the thing had been done.

To Gride it was nothing, merely a trivial incident in the day's work. He lay back in the big basket-chair and half closed his eyes, for the morphia had him in its grip now, and the man was worn fine by the need of sleep. He could see nothing of the contempt and anger in Barnes's eyes. And yet, had Gride been possessed of one touch of humanity, one shred of human feeling, then a greater man he might have been. As it was, he was a kind of scientific Bismarck, with all that individual's brutal contempt for anything or anybody that came between him and the goal of his desire. He had all the massive intellectuality, too,, with the spiteful cruelty of a Marat, a highly organised machine with as much sensibility and feeling.

He closed his eyes, and muttered something to the effect that he needed sleep, and that on no account was he to be disturbed.

"All right," Barnes said. "And if you die in your sleep, I shall thank God for it."

"Yes, it would be a good get out for you," Gride chuckled. "In the meantime, go on with your dinner, and don't worry about me. And tell Cosmos I want him."

The middle-aged Kanaka boy who cooked and cleaned and did for the two Englishmen emerged from his black hole at the back of the bungalow and stood to attention.

"I am going to sleep for an hour, Cosmos," Gride said. "Don't disturb me anyhow. Bring out my shaving glass and the soap and some warm water, and put it on the table there, so that I can shave when I wake."

The Kanaka complied obediently. He placed the tackle by the side of his master. He stropped the razor and laid it on the table convenient to Gride's hand. The latter might wake up in an hour, or he might sleep there all night, as he frequently did after one of his drinking bouts. For the moment he was worn out, body and soul. When the fiery spirit reached him, he would drink for two or three days at a time, eating nothing and working night and day, forced on by driving pressure that he could not resist. In these abnormal conditions his brain was at its best and brightest. Then Nature would call a halt, and after a dose of the blessed nepenthe he would frequently sleep the clock round.

And these were times that Barnes looked forward to, hours that he had entirely to himself to think and dream and plan for the future. He was turning matters over in his mind now as he pushed his chair back from the dining-room table and lit his pipe. How much longer could he go on like this? he wondered. Would it be possible to continue to the end of his servitude? Or should he throw up the whole thing and go back to Janet, and tell her that he had failed? An hour or so passed; the great full tropical moon crept np over the edge of the lagoon and flooded the sweating palm beach with a light as bright as day. There was silence everywhere, and not a sound to break it save the murmur of the tide on the sand and the hum of insects in the air. Then presently Cosmos, in the black hole that he called his kitchen, began to sing some weird Kanaka song, and Barnes was glad, for there was something near and companionable even in the nigger's voice. Then his own storm of black thoughts began to drift away, and he stepped out through the open window into the flooded glory of the perfect night. How far away from strife and trouble it all seemed, how peaceful and attractive!

Gride still lay there, with his long legs outstretched and his big, massive head thrown back against the cushions of his chair. He was in for a night's sleep, evidently. Probably he would not wake again till far into the next day. He was as still and rigid as the fringe of palms behind the golden beach—almost ominously still, Barnes thought. Some night he would die like this, for the man had an aneurism of the heart, and he had always declared that, if the trouble gripped him at the same time as he was in the midst of one of his drinking bouts, he would go out like the snuff of a candle. Almost in a spirit of hopefulness—an emotion of which he was slightly ashamed—Barnes approached the man who held him in bondage. Then he staggered back with a choking cry in his throat.

It was practically daylight, and every little detail stood out clear-cut as a cameo. Gride lay there. Barnes could see his head thrown back, and his throat cut from ear to ear. The keen blade had swept through the carotid artery and had penetrated almost to the spinal column. The dingy linen jacket and the discoloured shirt were stained with blood, already beginning to congeal, and from this Barnes judged that his brutal taskmaster had been dead an hour or two. A few yards away, on the edge of the verandah, lay a bloodstained razor, as if it had been hurriedly thrown down there by the assassin in his flight. But for this evidence, Barnes might have concluded that Gride had taken his own life; but no man could have inflicted such a mortal injury upon himself and at the same time flung the lethal weapon so far away. No, beyond a doubt. Gride had been murdered, and Barnes's first fierce emotion was one of gladness.

Then he took a pull at himself, and his reasoning faculties began to assert themselves. Who could have done this thing? There were only six people on the island altogether—two inoffensive Kanaka boys besides Cosmos and the three Europeans— and from the moment that dinner had been served, Cosmos had not moved a yard from the kitchen. A wild desire for human companionship gripped Barnes like a plague. He stepped down from the verandah and fled like a hunted thing in the direction of the hut where Denton had made his headquarters, and where he gave employment to the other Kanaka boys. The American was seated outside his shanty, smoking a green cigar and drinking some cool, seductive-looking mixture from a long tumbler by his side.

"What's the matter?" he asked. "You look a heap troubled. Sit down and have a drink."

"Gride has been murdered," Barnes said hoarsely. "He went to sleep on the verandah instead of coming to dinner—you know his way—and when I went out just now, I found him with his head almost severed from his body."

"Not much loss, anyway," Denton drawled.

"Very likely, but that isn't the point. Who could have done it? Not Cosmos, I swear."

"And not my boys, either, for they haven't been outside the hut ever since I came back. It seems to lie between you and me, Barnes. I suppose you haven't seen red yourself—"

"I see red every day," Barnes said bitterly; "but my hands are clean, thank God. I can't think. I am wearied and worn out, and my brain is numb. Come over to the bungalow with me, like a good chap, and see what you can make of it."

But it was very little that the American had to suggest. They carried the dead man into his room and covered him over with a sheet, and then Denton began to ask questions.

"Tell me everything," he said, "and don't omit any detail, however small. There aren't many details in a case like this, and, if you don't mind, I'll take this razor home with me. I should like to put it under my microscope, and don't you forget that I am some naturalist as well as a collector of butterflies, and I know as much about this amazing household of yours as you do yourself. Now, there's only one thing for it. You go quietly off to bed and sleep, if you can, and I'll come and talk it over with you in the morning, and if you take my advice, you'll have a few grains of morphia yourself. If ever I saw anybody who needs a drug, you are the hairpin in question."

It was about eleven the following morning when Denton lounged up to the bungalow, cool and collected as usual, with a smile on his face and a general suggestion of being master of the situation.

"Well," Barnes said wearily—"well?"

"I think I've got it," Denton said. "I worried it all out last night, and I found something on the handle of that razor that confirms my suspicions. Where's Crim?"

"Oh, how do I know? And what on earth has the chimpanzee got to do with it? As a matter of fact, I haven't seen him this morning."

"Now, you just come with me and bring a gun. When we have found Crim, I'll go on with the story."

Since the previous evening the chimpanzee had not been seen. He had not even come in for his breakfast. They found him presently high up in the centre of a clump of cocoa-nut palms, from which he nodded and chattered and showed his teeth in defiance. He seemed to be filled with a rage and terror that was quite foreign to his usual friendly and peaceful demeanour. Without a word, Denton raised his gun and shot the simian clean through the heart.

"That's as good as murder!" Barnes cried, aghast. "What did you do that cold-blooded thing for?"

"Waal, I guess we couldn't haul Crim up before a court of justice," Denton said. "We couldn't bring him before a jury and the rest of the fixings. In these parts, when you meet a murderer, you just shoot him. It's rough-and-ready justice, but it's just as effective. And I shot your chimpanzee, because he it was who murdered Gride. Not that I care anything about Gride, but when an animal takes to that kind of thing, he never stops. Now, look here, sonny, it's like this. When you told me all those details last night, I began to see my way. To a certain extent I was rather fond of Crim—he was as near a human as makes no matter, and he hated Gride almost as much as you did. Look how the poor brute had suffered at the hands of that cold-blooded piece of human machinery. Look at the times he has been operated upon without an anassthetic, and him big and strong enough to strangle Gride as easy as I can stick a pin through a butterfly. I tell you, Crim was waiting his chance. Didn't he see the little banana monkey have its throat cut? And wasn't everything ready to his hand when Gride went to sleep on the balcony last night? Why, it was as if that chap had been giving Crim an object-lesson. And Crim took advantage of it. He watched Gride till he went to sleep, and then he took the razor and cut the throat of the man that he had hated and feared and loathed more than anything that crawled on earth. And he had his revenge all right."

"Seems almost incredible," Barnes said. "But how are you going to prove it?"

Denton took an envelope from his pocket.

"I told you I was a naturalist," he said. "Anyway, I've studied the habits of the simian, and I know what he's capable of. Besides, I took that razor home last night for a purpose, and in the haft I found what I expected to find—a few hairs, which I have examined under the microscope. And those hairs came from Crim, beyond the shadow of a doubt. And I think that ought to satisfy you, as well as it satisfies me. At any rate, you are free now, and if any man ever earned his money, that man's name is Wilfred Barnes."

IT was a beautiful prison in which Angela Patton lived, but it was a prison, all the same. Not that she had done anything wrong, from the point of view of the Draconian creed, but, to begin with, she was alone and friendless in the world, a slim, little, somewhat fragile creature, with the heart of a poet and the mind of a child who has yet learnt something in the hard school of adversity. She knew the bitterness of the bread of charity, and though the bread that she ate now was thin and white and exquisitely buttered, it was as if it had been dipped in the waters of Marah and flavoured with servitude.

She was fair enough, and sweet in her own dainty way, with a pleasant smile and a wistful glance in those grey eyes of hers, so that the young man who came from the library occasionally to change Sir John Osborne's books, and who had an artistic mind of his own, compared her to the Huguenot maiden in Millais' famous picture—in which the young man from the bookshop was entirely right, and wiser than he knew. For the rest, she was discreet and sane in her maidenly way, and those deep grey eyes of hers were pensive and thoughtful and full of a quiet intellectuality, that touch of soul which was one of her greatest charms. In happier circumstances she would have been beloved and popular, and, perhaps, when the good fairy came along, she was marked out to be the happy mother of children and the helpmeet of some good man, who would have loved her, and never been conscious of the fact that she was growing old.