CYRUS T. COWMEADOW lay back puffing thoughtfully at his green cigar. Perhaps he was in rapt contemplation of the beauty of the night. Overhead was a powder of stars; in front of the restaurant kept by the polite Pietro Antelli the city lay in the fragrance of the April evening. Cyrus had dined both wisely and well, so also had little Antonio Broganza, the artist.

"Antonio, my brave," Cowmeadow said presently, "I begin to see my way."

Antonio smiled. When Cyrus T. began to see his way, the money began to flow; and, like all his clan, Antonio had not the gift for saving.

"Tell me the story again, Antonio," the American went on. "Who was the artist who painted the missing picture? Not that it much matters so long us he was ancient and famous. And be quite certain, my dark-eyed boy, that the facts are cold-drawn and planed at the edges."

"The great masterpiece of Guido, from the altar at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament here, you mean, signor," Antonio murmured. "Oh, yes! It was the glory of the chancel. It hung there for three centuries, till there was trouble with the French in 1740. Then the Guido he vanished and never more seen again. The French forces they included several soldiers of fortune, and one of them was a Lord Loring, sent away from England over some family trouble. Ancestor of Lord Loring who was ambassador at Rome odder day. 'E dead now, They say Guido at Loring Castle, in Scotland. But all that legend."

"What ho!" Cyrus quoted softly. "Proceed, sunny child of the South. And since that time the space over the altar has been blank. Suppose I could produce the picture? What would it fetch?"

"Hundred thousand pound," Antonio said promptly. "In America perhaps more. On the back of the picture one of the monks of San Bommo had written its story. Illuminated on vellum was the story, and attached to the back of the canvas. Also the story of what you calls pilgrimage to England to try and get the picture back. All in the museum here."

"You could make a faithful copy of all that, Antonio?"

Antonio modestly thought that he could. His white teeth showed in a flashing smile.

"I am an artist," he said, "also a restorer. We have been restorers for three generations. I patch and darn, or I copy same as the original—makes no difference. And no expert he can say where or which. I copy you that picture if we could only find him."

"You mean that you have all the materials at hand, Antonio?"

"Right. O, signor. Old parchments, old vellums, old paper, and old pigments—pigments such as are not to he found anywhere else. When Garibaldi made trouble, they came from a monastery. My father wept tears of joy when he got them. I can clean paint and gilt and lettering off old vellum, and write them and paint them as I do please. And then comes the expert from Bond Street, and he say: 'Behold, illuminated page of fifteenth-century work.' And I smile."

"There are no flies on you, unsophisticated child of the sunny South," Cyrus said. "If ever there were, they have yielded to treatment. What was the famous Guido supposed to be like?"

"Sorta copy in the museum here," Antonio explained. "Dauba."

"So much the better. You could make up a copy of it?"

"To deceive the universe," Antonio said proudly. "I have the old canvas, the old pigments, and the old varnish, the secret of which is lost. In three months the blooming fools from Bonda Street would come and say: 'Behold the lost Guido!' But there is a flaw, signor."

"There is the very devil of a flaw, Antonio," Cyrus agreed.

"Yes, I thought you would spota him, signor. They say whence comes the Guido?

Tell um the story of him being found. And there I fail—I have not the imagination, not the blooming nerve. And I am not what you call taking confederates. If it all fell easily and naturally, you understand—"

"0h, I understand right enough," Cyrus said. "This is where Cyrus T. comes in. This is his department on the first floor. You make the picture, and I'll do the rest. Got an old frame?"

"Make an old frame," Antonio suggested, "A moulding from one and as beda from another, and clamps from a third. All genuine old material with the ancient gold on it."

"Right O, dear boy! Then break it in two and cover it with dust and cobwebs. Manage that?"

"Manage anything," Antonio said promptly. "All in your hands. And you say what price, Antonio?"

"Well, say two thousand pounds. If the whole of the Session's legislation passes, I'll call it five. More money than you ever made in your life, Antonio. No chance of the real picture turning up?"

"E never turn up," Antonio responded. "Lost or destroyed long ago. No fear!"

"Well, there certainly isn't much,"Cyrus admitted. "When can you get to work, Antonio?"

The clever little Italian could get to work at once. He would have to put other tasks aside, and he needed money. For the next three months he would have to think of nothing else. He could get along in the meantime with a thousand dollars. Cyrus T. promptly counted out the notes.

"Now, you set to work without any further delay," he said. "I'm going as far as Paris for a month, Funny thing if I happened to run up against Lord Loring there. Spends most of his time in Paris, he does. He flings it about, Antonio; it's a family weakness. He was in New York last fall, looking for beauty and intelligence embedded in a ton or two of dollars, but nothing materialized. Guess I'm going to be as good as a father to Lord Loring. I'll come back later and report progress."

IL was well towards the end of July before Cyrus T. returned to Florence. Antonio welcomed him with open arms. The great work progressed famously. Would the Signor Cowmeadow come round to the studio and look for himself? Cyrus replied dryly that he would.

"As the bridegroom said to the parson who asked if he would take the woman for his wife, I've come on purpose," he said drily. "I guess I'm going to be satisfied."

He was. As a matter of fact, he was never more satisfied. Never had he fully appreciated the craft and skill of the little man before. The picture was practically finished. It stood there in a wonderful frame of black and gold; the subdued tint of the ages clung to it like a fragrance. There was the sooty grime on the canvas, and there was the discoloured story of the great work in gold and black and blue, a little faded and stained, as it had come from the cunning hand of the monk centuries before. Bond Street would have passed it as genuine at a glance.

"It's great," Cyrus cried—"immense! If only the story was as good as the picture, we should just sit down and divide one hundred thousand pounds between us. But it ain't, Antonio—it ain't."

"Whata yer mean to say—there is the chance of being found out?"

"No, I don't, Antonio. The story's all right if we are content with a few thousands each. The trouble is, I can't think of a story whereby we can get the lot. To try the game on here means confederates, and you don't like confederates, Antonio."

Antonio was quite emphatic on that point.

"Very well, then; our game is to play for safety. If we 'discover' the picture here, there will be all kinds of inquiries and cross-examinations, and perhaps a battle between experts that'll keep the game going for years. I can put everything right if we are only modest. But the main part of the plunder is going to a blue-eyed boy, the head of a northern clan, who will never know his luck, and never know he did a bloated Chicago millionaire in the eye. By Jove, Antonio, I've got it! We s make ten thousand pounds apiece yet. Then you can return to your vineyard and die respectable."

A week or two later Cyrus T. departed en route for London. From Paris he had despatched a large case to a certain address in the fair town of Perth, where it was to remain till called for. At the Gare du Nord, Cyrus, quite by accident, he encountered Lord Loring. But then these "accidents" always do happen to the shrewd and far-seeing who never neglect the opportunities. The clean, well-set-up Englishman greeted Cyrus in the most friendly fashion. He rather liked the company of American millionaires. In the late autumn he was going out to America again. In common honesty to his long-enduring mortgagees, it was only fair that he should do something. He gladly fell in with the suggestion that he should share a coupé with Cowmeadow. Was Cyrus going over for the grouse?

"Well, I'm looking forward to a go at the birds," Cyrus explained. "I meant to take a shoot myself, but I got tangled up with a little gamble in Paris, and that kept me. Don't know that the two hundred thousand dollars I made on the deal was worth all the trouble. No chance of picking up a really good moor as late as this I suppose? I'd share one up to one thousand pounds."

Here was a chance direct from the hands of the gods, and Loring promptly and gratefully accepted it.

"I'm short-handed this year," he explained; "one or two good guns have failed me. The man who was going to have the shoot died suddenly. If you like to come in—"

"I'll certainly come and look at it," Cyrus said indifferently. "When are you going up?"

Loring replied that he was going up on the first of August. Would Cowmeadow come along and take pot luck at the Castle for a few days, and look round? There would be plenty of time to decide. With a frown on his face, Cyrus went through his engagement book.

"Sorry I can't manage it," he said. "But I can get away for a few days on the third. That do you?"

As a matter of fact, it did Lord Loring very well. He was going to make one thousand pounds that he had not in the least expected, and he was going to shoot his birds as well.

Cyrus turned up at Loring Castle on the day arranged, bringing no more than a couple of suitcases and a square deal package that he seemed to regard with considerable anxiety. He praised the grand old place, the rooms and the grounds; he was not satisfied until he had examined everything from parapet to basement. There was nothing suspicious about this; Loring had entertained Americans before now, and recognised the symptoms. For the next two days Cyrus ask nothing better than to prowl about the house, looking into any dark corner and finding interest everywhere. On the third evening be asked for a fire in his dressing-room, as the night was chilly. After this boon was granted, he locked the door and proceeded to open the deal cane. The covering was promptly consumed in the fire, and the contents of the box disposed of presently to Cyrus T.'s satisfaction. There was only one thing that marred his content—he was not quite sure, after all, whether or not he could stay for the shooting. His partner in New York was ill, and his old enemy, Gilead J. Broff, was taking advantage of the situation. At any moment he might be called to return home again.

"At any rate, I'll just chance it till the end of the week," he said. "Let's go and sit in that jolly old gun-room of yours and have a final cigar. Ever get any burglars here?"

"Never heard of such a thing," Lord Loring laughed.

"Well, the place is worth a visit," Cyrus responded. "Still, I suppose that old silver would not sell except or its face value. All the same, I like to sleep with a revolver under my pillow. I've got one in my dressing-room now."

Lord Loring smiled at the suggestion as he made his way up to bed. An hour later he was aroused by the whiplike crack of a revolver. The unexpected had happened. Then came a shout and a hoarse cry, and once more that spitting of the revolver. Loring staggered into the corridor and looked about him.

At the far end of the corridor there appeared Cyrus in a blaze of glory not entirely unconnected with the violent hues of his pyjamas, He staggered with his hand to his side; he suggested strife not wholly devoid of personal triumph.

"What on earth is the matter?" Loring demanded.

"Guess I've left my mark on them," Cyrus responded. "I winged one of the chaps—broke his arm. He managed to get out of the big window at the end of the corridor. What I want to know is what those chaps were after? What were they doing in the ruined west wing? "

"What chaps are you talking about?" Loring asked irritably.

"Why, the burglars, of course! I heard them go past my door. Always sleep with one eye open; you had to, out West, when I was a young man. Ought to have called you up, of course, but wasn't quite sure which your room is. So I followed them along the corridor to the deserted wing. Three of 'em altogether. They were pulling a whole lot of lumber about, as if looking for something. By sheer had luck I happened to sneeze. They were on to me like a flash. Pretty hot whilst it lasted, sonny, only was quicker with my gun than they were."

"What—you don't mean to say that they actually—"

"That's what I'm getting at," Cyrus said coolly. "I'll show you the bullet marks. I got one under the jaw with my fist, and winged another with a shot. Then they concluded to leave by a large majority. Only wish you had been there, my boy."

"Only wish I had," Loring said fervently. "But what on earth were those fellows doing there? It's not exaggerating to say that nothing in the whole wing has been touched for a century. The rooms are packed with lumber of all kinds. Everything superannuated is shoved in there"

"Well, I guess the best thing we can do is to go and see," Cyrus suggested. "Get your candlestick, and I'll fetch mine. Not that we shall find anything."

The big room bore signs of a struggle. A long splinter, obviously the work of a bullet, been torn from an angle of the panelled wall. A heap of rotting canvases in tarnished frames were scattered all over the floor. On one of these lay a sheet of paper, which Loring picked up. He saw at a lance that here was a rough sketch-plan of the old wing and some notes in pencil, evidently scratched there for the guidance of the burglars.

"Very odd!" he muttered. "Anybody would imagine that some treasure was buried here. Sort of Robert Louis Stevenson business. Left-hand corner under the pile, two from the bottom. What does that mean? Angle next to the dormer window. Dash it, there must be something here, Cowmeadow! Black and gold frame, illuminated description on the back of the canvas. Jove, it's a picture they're after!"

"Shouldn't wonder,"Cyrus responded: "Some forgotten picture they've got on the track of. Old family servant left a diary or something of that sort. They tell me these old stories are often handed down in the servants' hall from one generation to another. Silly game, for the most part, but they have been true sometimes. More than one masterpiece has been unearthed that way. There isn't one of those missing in your family, I suppose?"

"0h, well, we have plenty of legends," Loring said indifferently. "There's the story of the Guido, for instance—the big picture from the Church of the Blessed Sacrament at Florence. An ancestor of mine had it beyond doubt, but I'll take my oath he never brought it here. The old boy died suddenly, and they say his body-servant could have told a story. All bosh, of course!"

"Well, I guess I'm not so sure of that." Cyrus protested. "These old facts have a curious way of turning up again. I'll just see if there's anything in that paper, anyway."

Loring nodded as be proceeded to light a cigarette. He watched Cyrus pulling a heap of dusty frames about for the next half hour. Then the American gave a dramatic start.

"By the Great Jerusalem, I've found it!" he cried. "It was lying at my feet all the time. Those chaps had actually got on the scent before I intruded on them. Look at this!"

Loring came forward a little more eagerly. On the floor was a fine carved black-and-gold frame, and in it a picture partly cut away from the stretcher. The cut was clean and fresh, as the even edges of the canvas showed.

"This is what they were after," Cyrus said in a voice trembling with excitement. "They must have been actually cutting the picture away as I came in. What a find! Guess I know something about pictures. I've made money out of 'em. Help me to turn the frame ever. If there's a neat little illuminated panel of vellum on the back, I guess we've found the Florentine Guido."

Surely enough, the panel in question was on the back of the canvas. Cyrus reverently picked up the frame and carried it along the corridor to his room. He poked up the fire and helped himself to a cigarette—to steady his nerves, he said.

"Well, I guess you are up against the luck," he exclaimed. "Everything is going your way, sonny. You've got a little picture card there worth one hundred thousand pounds. You'd get that price for it in America in a week, and I'll guarantee to find you a customer."

"If you will, you shall have my grateful thanks," Loring said.

"And ten thousand pounds," Cyrus said coolly. "Guess we'll make a business deal of this. Never lose a chance of piling the dollars in what's pasted in my hat. Lots of men would have kept their necks shut and bought that picture or a few cents."

"Oh, well," Loring laughed, "I'm sure I'm quite agreeable! Only we shall have to hear first what experts have to say on the subject. It may only be a copy."

"Well, I'll give you e cheque for a hundred thousand dollars on the off-chance," Cyrus drawled. "Just you make out a little story on the subject and send it to The Times, and let the experts know that they are welcome here; and I'll stay and see the fun through?

Bond Street rose at the bait like one man. This letter in The Times had stirred the critics to the deepest depths. There was something in the direct simplicity of the story that appealed to them. And the local police were equally impressed. They noted the splintered panelling; they found an old type of revolver bullet that fitted a weapon they had discovered in the castle grounds. Four chambers in the revolver had been discharged. There were blood spots on the corridor window and the marks of feet on the flower-bed below. The authorities had an important clue, and an arrest might be expected at any moment. Most of the papers took up the story with alacrity, and the main-line expresses were packed with critics.

A score of the big dealers reached the castle during the next few days. There was only one opinion, and that unanimously in favour of the Guido. Beyond all question, it was the missing masterpiece from the altar of the old church at Florence. Everything tallied exactly; there was not a flaw to be detected anywhere; every detail of the legend dovetailed beautifully. At the very least the picture was worth ten thousand pounds. It might have to remain in the possession of the purchaser for some time—Americans were not buying just now—but Mr.Preset, of the famous firm of Preset & Co., was prepared to pay ten thousand pounds for the picture now.

Lord Loring politely declined; also he politely declined an offer of double the money from Sir George Doubleday, of Doubledays Limited, a few minutes later.

"My price is one hundred thousand pounds?" he said, "and I shall take nothing less. After to-day the picture will not be on view; I'm sending it to London."

Sir George sighed and shook his head. In the present state of the market—The market must have taken a surprising and gratifying turn for the better, for next day Sir George, on behalf of a distinguished client, made an offer of seventy thousand pounds. Loring tossed the telegram in the fire. Two days later came an urgent telephone message from Sir George, to the effect that he was brining his client down to see the picture, and that no doubt Lord Loring's desire would be accomplished. Two days later still The Times came out with the announcement that the famous Guido had changed hands for one hundred and ten thousand pounds, and that the fortunate possessor was Mr. Emanuel S. Blickstein, of Pittsburg, Pa. It was some hours later that Cyrus T. Cowmeadow left Loring Castle, plus ten thousand pounds and a promise to return in a day or two unless urgent business did not call him to Chicago. Probably it did, for Loring Castle has not seen the ingenious Cyrus from that day to this.

Cyrus T. reviewed the situation as he travelled back to London. He had done very well, inasmuch as the thing was safe, and anything like greed might have ruined the whole situation. The real lucky one was Lord Loring, who would never know what a friendly joke Fate had played on him. On the whole, Cyrus was proud of his artistic effect. Still, there was more money to be made, and Cyrus was going to lose no time in liquidating his stock whilst the market was still in his favour. The Guido had been removed to Mr. Blickstein's suite of rooms at the Imperial Hotel, and many receptions had been given in its favour. The rest of the time the Guido reposed in the hotel strong-room.

Cyrus called at the end of one of these receptions, and contrived to find his way into the private sitting-room of the great steel magnate. The Guido reposed in state upon an easel. Mr. Blickstein did not receive his visitor with fervour amounting to enthusiasm.

"What do you want?" he asked. "I told you not to come here again. The past is past, Cyrus."

"O.K.!" Cyrus said cheerfully. "I came here, my boy, to save you one hundred and ten thousand pounds."

"Oh, really! In what way? And what do you want for doing it?"

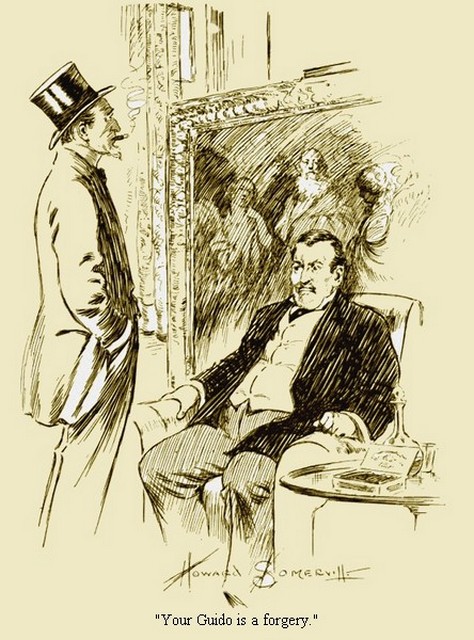

"Ten thousand pounds, my noble Semite," Cyrus went on. "Shut the door. Anybody near us? No? Then, my good Croesus— your Guido is a forgery! Never mind how I know—I do know! And I'm the only man in the world, bar one, who is acquainted with the fact."

"Oh, oh! Then Lord Loring—"

"Loring is as innocent as a child. Here, turn the picture over on its hook. Now look at that panel there. Genuine, you say? Very well, then; take off the bead round it and look on the other side of the vellum. You'll find some illuminated lettering on the reverse. In fact, the vellum was taken from a missal done ten years after Guido was dead or before he was born—I forget which. Then ask one cf those Bond Street prophets."

"I've been had!" Blickstein cried. "I'll have the law on everybody! I'll punish everybody, and—"

"My dear chap,"Cyrus said soothingly, "you'll do nothing of the kind. You'll keep your mouth shut, my friend. The picture has been passed by the leading experts of Europe as the real and genuine terrapin. It'll go down to generations yet to be born as the Guido, and, as time goes on, it will get more valuable. And if you're ever hard up for one hundred and twenty thousand pounds, you can raise the boodle on that postcard. Why tell anybody? Why make a fuss? Why let your enemies know that Emanuel S. has been had? It's good advice I'm giving yon, Emanuel, and I guess that it's cheap at ten thousand pounds. See?"

Blickstein controlled himself creditably. He also reached for his cheque book; he saw the soundness of Cowmeadow's reasoning.

"This is to be a secret between us?" he asked.

"Obviously," Cyrus said, "I'll take an open cheque, sonny."

"All right!" Blickstein snapped. "In that case, I'll make it payable to bearer."