RGL e-Book Cover 2018©.

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©.

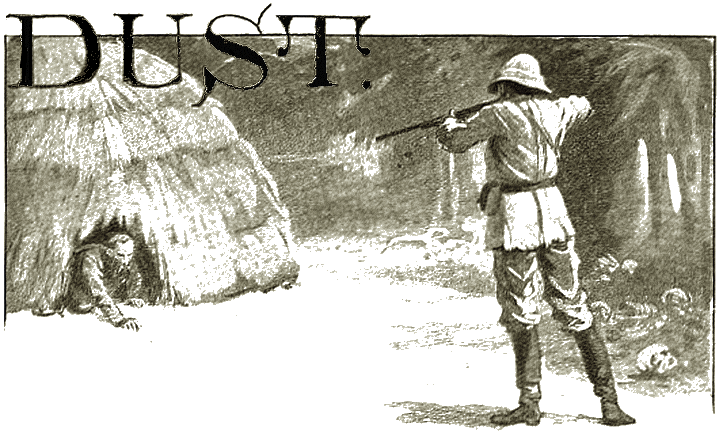

A figure on all fours crept from the hut.

"IN time for the prize distribution," said Denn, "but too late for the fireworks."

He pointed to the ghastly scene that lay before Houseman and himself. The agile newspaper man who had supped horrors with a short spoon during that infernal Cuban business shuddered, as well he might. Houseman collapsed in the shadow of a wattled hut; his big limbs were mere frames now.

"Give me the quinine," he gasped. "Lord, how deadly sick I feel!"

Denn handed out enough dry quinine for a forty-pound head of steam, and Houseman sucked it down with a gasp and a gurgle. The dryness of his throat was painful. The skin of both men was hot and dry, dry as the heat of a Meldrum furnace, and the glass stood at 120 in the shade.

"You're a fine site to build a man on," Denn said with tempered admiration. "That's the worst of you brawny chaps; in a country like this you run to dripping. Now look at me."

"You're an ugly, red-headed beast," Houseman groaned. "If I could boast an ounce of energy, I'd punch your head. If I could only have a drink of water!"

"We didn't come here for water; we came here for ivory."

Houseman waved a limp hand generally towards the village. It was a big affair in its way, with a hundred or two of huts, a couple of comic opera temples, and a headsman's "palace." A stockade ran round the village; every hut had its bristling yellow fringe of piles, gleaming fitfully in a sun born of Gehenna; even the temples and palace were constructed on frames formed of the yellow tapering piles.

"Well, there it is," Houseman grumbled. "Every one of those cursed prongs is a tusk of sound ivory. None of your kagmag, but the real Simon Pure ivory. Tens of thousands of them, five hundred tons at the least, and you can have my share for a mouthful of dirty water."

Houseman chewed more quinine and groaned. For six weeks he and Denn had come creeping along the fringe of the Congo Free State in search of this veritable treasure house. So far as they could gather, no agent of Messrs. King Leopold & Co., telegraphic address, Brussels, had scented out this yellow village where it all lay. The truth about it had been extracted from a bushman, with an eccentric bias towards truth, after two bottles of trade gin and a patent suet chopper. Ramani had agreed to pilot Houseman to the village through the bush tracks unknown to murderous Belgians, and doubtless a bargain could be made.

Denn had jumped at the chance of going along. There was enough wickedness, he said, alive around Boma to give Tophet a record summer season, and enough spice with it to shove up the circulation of his paper, and he had a free hand.

Houseman was not averse from a companion like Denn.

For six weeks they had skirted the big forest of Shaz, keeping the peak of Uni Uni in sight the whole time. The volcano was asleep now, had been for years, and the Shaz forest had crept up to his brisket again. Houseman was for a short cut through this forest, but Ramani shuddered and refused to explain. Obi and fabulous beasts, maybe, Houseman thought.

And now they had come at length to the village of ivory. They had crossed the border with a fine train of mules, a score of packages of Manchester goods and Birmingham jewellery, a dozen bushmen and Ramani.

Of all the glittering pageant nought but two white men and two Winchester rifles and a case of ammunition remained. Still, the village was reached now, the natives, uncontaminated by hot rum, and still hotter religion, were presumably friendly. By specious promises, doubtless the ivory would be gotten to the Congo, and two fortunes, to say nothing of two reputations, made.

This was all very well on paper, but it sadly failed to tally with the ghastly truth. The once smiling village of the plain was deserted. In the streets lay piles of grey bones, horrible grinning skeletons in every grotesque attitude, men, women, and children ruthlessly slaughtered. The rattling bones whitened and calcined under the rays of a pitiless sun. Hundreds of grey vultures hovered in the air and rose from the ground like flies from filth when suddenly disturbed. The village was one gigantic charnel house. There was no smell or reek, for the grey gorged birds had done their work. A few hours, probably, had only elapsed since the awful slaughter had taken place, but the silence of desolation was everywhere. The sun shone down from a sky like green bronze, the heat smote like waving volleys of musketry.

"Too late for the fireworks," Denn remarked again.

But Denn would have jested in any peril. He irritated and at the same time encouraged Houseman. The quinine was getting on with its work. "Look here." he remarked, "there must be some cause for this horrid business."

"A family quarrel," Denn suggested. "A little tribal argument."

"Tribal, no doubt. But why? This looks like something more than an afternoon call. Go and prospect around, and see if you can find anything. I'm never any good in this climate till sunset; then I shall be on hand in full-dress uniform. And if you can find a gourd or skin of water—"

Denn set off on his tour of inspection. Man of courage as he was, he had his nerves set on edge more than once during his investigation. The slaughter of the villagers had been so complete that not a dog remained. With a certain morbid curiosity he examined a grinning skull or two, and as he did so certain facts were borne in upon him.

"Shot, by the living jingo," he cried. "There's more here than meets the eye. This looks like a raid led on by some white man for dark purposes of his own. In this diabolical climate, personal aggrandisement, doubtless. Now this skull—"

Denn was scientifically diagnosing a ragged bullet wound in the skull, when there came a puff, a crack, and the skull went spinning from his hand. Denn grabbed for his Winchester and poured a quick fire into the hut from whence the puff of smoke came. A dozen bullets ripped into the frail cuticle of the hut like rotten cheese, rendering the cover futile. Then somebody in passable English called upon Denn to cease.

"Come out and show yourself," Drenton commanded.

A figure on all fours crept from the hut. Denn saw a face yellow as a spade guinea, a wicked, corrugated, oily face, with a nose like a hatchet, and a ragged beard like the rusty nap of an ancient silk hat.

"Throw up your hands," Denn roared.

The figure did so, and then quietly advanced at Denn's suggestion. The Yankee's quick eye detected the bulge in the stranger's hip pocket. With gentle persuasiveness he asked for the revolver. With less grace and courtesy the weapon was handed over. Denn placed it in his own pocket.

"Now lead the way back to your hut," he said. "You're not my beau ideal of a hospitable host, but needs must when the devil drives."

THE hut was roomy, and by comparison, cool, for it was dug down like a cellar and the hard floor was wet with water. There were skins, and gourds, and earthen vessels on the moist earth, the tiny dewy heads on the outside testifying to the grateful fact that they were full.

With eyes glistening with a holy joy, Denn proceeded to the door of the hut and whistled. A moment later, and Houseman crept into sight. He came languidly, and with the air of a man who makes quite an unnecessary sacrifice in the cause of friendship.

"What is it?" he said hoarsely.

"Water," Denn yelled, "and plenty of it."

Houseman put on a spurt like a forty-nine-second man finishing the quarter. He landed on the floor of the hut with eyes aflame and hands that trembled. Then he took an earthen pitcher and tilted the sparkling blue-white fluid down his throat very much as if it had been a drain. Denn followed suit with his lids closed in ecstacy. It was a moment unrecorded even in the lives of kings. Houseman grabbed another pitcher, and deliberately poured the water over the crown of his head. Denn followed suit. Imagine the chill-stinging bliss of it with a dry shade temperature of 102 degrees.

"Egad," Houseman cried. "Upon my word I'm a man again."

"A man!" Denn responded. "I'm a battery of artillery and a fire brigade all in one. What's your name, you murdering thief?"

The yellow image in the hat nap beard was understood to say that his name was Garcia, also adding as a rider that he was a free-born Belgian, whose enlightened Administration would see into this outrage.

Denn was not the man to waste time in idle words. He caught the jaundiced Garcia by the right hand and twisted his arm behind his back. The operation was painful, and the Belgian tendered a free testimonial to the fact.

"I'm not going to have any of your nonsense," Denn remarked. "But that I hope to hammer some useful information out of you, I should have punctured your tire a spell back. Is there anybody else here?"

Garcia smiled. It was a fawning kind of smile, followed by a nasty drooping of the eyelids. Houseman carelessly touched his Winchester.

"None but a tribesman who is faithful to me," the Belgian explained, "and he has gone on for something from the next village."

"Oh, so you are friendly with the folk in the next village?"

"Yes, yes. My bushman, he come from that tribe."

Denn began to see things with considerable clearness of Vision.

"Thanks for the information," he said drily. "You came prospecting here like ourselves in search of considerable ivory. We've all found it. And what we have found won't be worth much less than hall a million in market overt. You discovered that the natives here were averse from parting with the bones. They didn't know their value, but they had caste prejudices of a short- sighted nature. It wasn't a bad idea of yours, friend Garcia, to go further along with your short Enfields and make friends with the next tribe, because you could stir up strife and arrange for the next tribe to come down here one summer afternoon and rub out these unsophisticated children of Nature considerably. Well, you seem to have been pretty successful."

Garcia protested against the suggestion. Should he be held responsible for the bloodthirsty nature of the savage? Perish the thought! Denn waved him aside.

"We'll let it pass," he said. "Anyhow, you're here and we're here, and what is still more to the point, the ivory is here also. There's a hundred and fifty thousand apiece waiting for us if we pull together. I don't particularly yearn to pull with you, Mr. Garcia, but necessity knows no law. And we've got a Winchester each."

Garcia expectorated with easy fluency. The stuff was his, he was arranging to get it down to the coast, and he would be blessed if he would divide with anybody. Let the Englishmen wait till his faithful bushman returned, and then they would see what they would see. Denn's face grew grim.

"A while back you tried to murder me. I ought to have shot you then. I'm a lasting disgrace and discredit to my mother that I don't drop you now. I've knocked about the world a bit without gathering any moss, but I calculate I'm going to roll in it this time. You grasping yellow tomato, can't you be satisfied with your share, to say nothing of the assistance of two men who are worth a whole continent of niggers?"

Garcia's eves gleamed. They could have spelt nothing but treachery, not even to gain the kingdom of Heaven. Denn looked at the Belgian thoughtfully.

"Do you agree to our terms?" he asked.

"I've got to," was the sullen reply.

"Very well, then; give us something to eat."

Garcia hustled about as far as the heat would allow. There was stewed chicken and rice with curry powder, and a bottle or two of what purported to be beer. The meal was barely despatched when a tall figure darkened the door, and a native with eyes opened widely came into the hut. He was tall and gaunt and thin as an ostrich, yet his spare limbs looked like steel covered with leather. His lace beamed with joviality; his woolly head was covered with a cocked hat and feathers; he wore a ragged mess jacket and a pair of tattered spats. As to the rest, he was Adam before the fall. Denn was fascinated.

"Say, corner man," he asked, "what's your name?"

"My name Johnny Walker," was the response. "Me Belgian gentleman. No black fellow. Speakie English same as other white men."

Johnny Walker proved to be an ally of real merit. In the first place the heat affected him not at all. He could work remarkably well, he knew the ways and manners of the country, he had an unerring nose for water, and he had a wonderful command over his fellow-bushmen. But despite his joviality and his disposition to laugh on every available occasion, there was an occasional look in the corner of his eye that neither Denn nor Houseman liked.

The sun plunged down at length into the sea of darkness beyond the forest of Shaz, and the hoary, dusty head of Uni Uni faded away into the purple gloom. And the night wind was blowing still, hot as the breath of the Pit; but it was a wind, and that was something.

Denn and Houseman sat outside the hut smoking. Garcia was their partner in business, but that was no reason why they should make a friend of him. And, to do him justice, the Belgian offended no nice taste by indecently thrusting himself upon his companions.

Houseman lay upon his back facing the coppery flash of the stars.

"What do you think of him?" he asked.

"Garcia?" said Denn. "I don't think anything of him. A dirtier and more treacherous rascal never breathed. If he gets a chance of doing us down, do us down he will. And Mr. Johnny Walker would cut our throats and roar over the job. If he brings some of his boys down here, we shall have a warm time of it."

Houseman smoked thoughtfully for a time.

"I've been thinking," he said presently. "To all practical purposes Garcia is our partner. If he gives us the slip we can make him disgorge afterwards. And it isn't quite healthy for us here. Why not get down to Shaz and bring our surplus stores and followers here? We can depend upon those men, and the Winchesters will keep Johnny Walker's boys in order. Garcia cannot give us the slip. His friendly tribe yonder would never dare to carry for him beyond Shaz, for fear of being made slaves in Congo State. Now we have once found the way, it will be quite easy for us to bring our resources up here. It was those weeks of blindly groping about yonder that did the mischief."

"That's not at all a bad idea of yours," said Denn. "What you say about Garcia's friendly niggers is quite correct. Whatever happens, Garcia can only go one way, unless he knows of a track through the forest."

"The natives wouldn't go. They are afraid of that Obi nonsense."

"True, but look here. Johnny Walker seems to know the ropes. And as a shining produce of latter-day civilisation, he appears to be devoid of superstition. I'd bet money he knows a way through the forest. Promise him a gun and he'll get us down to our base on the far side of Shaz in no time. If he can do this, we shall save at least a fortnight."

Johnny, duly approached, knew a path through the forest. He was fettered by no clinging prejudices. What did he care for Obi? And Garcia approved of the business with a grim smile that puzzled Denn, and made him feel more or less uncomfortable for a few minutes. Johnny, too, was bubbling over with laughter, which laughter became more and more exuberant every time his glance wandered in the direction of the strangers.

"They are up to some game," Houseman muttered.

"I don't care," responded Denn. "Game or not, if Johnny tries any of his tricks upon me there will be a fine chance for some Central African swell to pick up a gilt-edged wardrobe cheap. Don't you worry, because Johnny will get us down to Shaz all right, the promise of the gun guarantees that. It will be afterwards that the trouble comes."

Houseman turned over sleepily. He was falling into that placid state preceding sleep when troubles dwarf and dwindle. Then he slept. Dunn sat finishing his pipe, and listening to the low rumble of Garcia and Johnny's conversation. They seemed to be amused at something. Every now and then there was a queer jar in the nigger's staccato laughter.

"I don't fancy I'll sleep just yet," Denn muttered. "It might be dangerous. I'd give a trifle to be in the joke."

A few minutes later and silence reigned supreme.

"We're a fine specimen of a happy family," Drenton Denn remarked, as he watched Johnny Walker making his final preparations for the forest journey. "We are partners in a big bonanza, and we ought to love one another, but we don't. I suppose this is what you call an offensive and defensive alliance—get all you can out of the other party and cut his throat after to save him the trouble of cutting yours."

Not that Denn or Houseman had much cause for alarm. There was only one way down to the road below Shaz, so there was no chance of Garcia's giving them the slip. Moreover, they held Johnny Walker as a hostage.

Johnny seemed to be impressed with the importance of his mission. The Christy Minstrel side of his nature was suppressed for the moment; he wore a grave and solemn air; he might have been a Cabinet Minister in the throes of a political crisis.

"We no travel in the daytime," he said. His manner was complete and final. "Much hot in the forest then, no air comes, and sun blaze down between the trees. Travel by night and sleep by day."

"All right, General," Denn responded cheerfully, "it's all the same to me. Get us down to our base quickly, and you'll be honourably mentioned in the dispatches."

They set out the next evening a little before sunset, and by the time darkness came they had plunged into the thick forest. Whatever might have been Johnny's own opinion of his merits, one virtue he certainly possessed, and that was a perfect knowledge of woodcraft.

That he knew the way perfectly was obvious from the first. No bushman unfamiliar with that dense belt of forest would have dared to strike into the heart of it otherwise. And Johnny hesitated not at all. With a careless glance to the left and right he strode on, never once halting till the first strokes of dawn appeared.

Then he called a halt and breakfast was partaken of. One thing struck the two white men as strange. There was practically no undergrowth, no luxuriant ground vegetation, nothing but huge forest trees, and underfoot a grey bare floor, as if the greater trees had sucked up the moisture necessary to plants of smaller growth. It was a floor smooth and hard and undulating, with thousands upon thousands of giant boles, like dim cathedral aisles stretching away, vast, dim, diminishing into gloom.

There was another and equally striking feature. Animal life there appeared to be none. Occasionally an unseen bird gave out one long melancholy note like the sound of a cracked bell—a horribly suggestive note.

Houseman looked around him and shivered.

"Beastly," he said. "I feel like a man who has been asked to a funeral where they have mislaid the corpse. I'd like to wring that infernal bird's neck and stop that passing-bell of his. John, is there much more of this Dead March in Saul business?"

Johnny responded with his best manner. He had become grave and courteous, like a chaplain in the condemned cell, Denn suggested.

"Two hundred miles," he replied, "and all'e same. Cause why, Shaz he sometimes smoke his pipe, and the dust from the mountain he come down and down like dense mist on the river and he chokee everything up 'cept dem big trees."

"He means an eruption from Shaz," Houseman explained. "The dust and ashes settle down and choke everything but the forest trees, and as it rains here but once in forty years or so, everything gets a little thick. Gets worse as we go on, Johnny?"

Johnny smiled, with a curious gleam in his eyes not lost upon Denn. The time was coming when they were to remember this conversation. But for the present, the pressing demands of sleep engaged their attention.

When they awoke again the sun was low, and Johnny had supper ready. Throughout the whole of the second night they struggled on, the silence growing more oppressive and the dust becoming deeper under their feet. It would he impossible to describe the awful gloom of it all, the dead stillness, as of a world hushed in a last long sleep, the cracked passing-bell notes of those ghostly unseen birds, the grey pall of dust lying everywhere.

"God help the man alone here," Denn remarked as he turned from his breakfast. "This is the haunt of the lost, the valley of shadow leading to the gates of hell. No wonder the niggers are afraid of it!"

Houseman made no reply. A heavy melancholy lay upon him. At every breath, at every motion of the body, dust fine as flour rose in clouds. Their clothes were saturated with it, the sifted grey particles covered the skin; hair and moustaches were loaded with the stuff. Nothing but the constant supply of water possessed by the party kept throat and lips moistened. A long- drawn chain of slumber was impossible. The choking dust woke them to drink greedily and then to slumber fitfully again.

Out of a troubled dream Denn woke at length, with a gasp and a start. The broad light of day was gleaming through the trees. By Denn's side, like a corpse under a diaphanous cloth, lay Houseman. The cloud of dust, falling, dripping, feathering from the trees, had covered him completely.

"This business is getting on my nerves," Denn muttered. "Fancy another eight days of this. Get up Houseman, it's breakfast time."

Stimulated by a vigorous kick, Houseman struggled to his feet.

He blew the dust from his lips and nostrils like a cloud. He gasped and gurgled for water, which Denn administered. Two grimy millers stood confronting one another.

"Where's Johnny, and where's breakfast?" Houseman croaked at length.

Denn looked round him swiftly. There was no sign of Johnny to be seen. The provisions lay there, and the water bottles were there, but nothing had been made ready. In a voice that trembled slightly, Houseman yelled for the dusky retainer. No sound came in reply, save the echo of the bell bird's note.

Demi tried to light pipe cheerfully. Smoking in that stagnant, loaded atmosphere was impossible. The Yankee sat down resignedly.

"I confess to being in a mortal funk on a few occasions," he said. "I was in a mortal funk when those firebug chaps had me at their mercy. I felt pretty blue when I had the brush with the Red Speck in Madagascar, but I never felt worse than I do at this present moment.

"Johnny 'Walker has abandoned us?"

"That's about the size of it. We are over forty miles in the thick of the most awful forest ever imagined by the mind of man. We haven't a notion where we are, and our tracks are sifted up almost as soon as they are made. When our provisions give out we shall perish miserably. With the greatest care our water can't last more than another day, and we don't know the spot where dear Johnny intended to fill the bottles again. Fancy the thirst we shall have in this atmosphere before long!"

Houseman bent his head and shuddered.

"Don't," he said, "don't think of it. If Garcia had not been a coward he would have murdered us, and there would have been an end of it. I suppose a death like this suited his purpose better. If ever we get out of this!"

Denn laughed bitterly. The fearful gloomy silence depressed even him.

"My boy," he said solemnly, "if ever there was a case of 'Rock me to sleep, mother,' this is one."

THEY were struggling on and on together, fiercely, desperately, with haggard eyes and gritted teeth, as the Anglo-Saxon has ever fought in the face of death and danger. A day and a half had elapsed, and the adventurers were at the last gasp.

Provisions they had in plenty, but the lack of water was dreadful. They were doling it out a spoonful at a time, and even only then when it became absolutely necessary. No words were spoken, for speech was precious, and saliva was as a black pearl. Ever and anon one of them would fall hack gasping, with distended lips and a tongue black as charcoal, and then the other would pour a dozen drops of the precious liquid between the teeth. They were spent and faint with hunger, too, for under the black circumstances eating was almost impossible.

And the further they penetrated into the grey despair of that maddening gloom, the worse case was theirs. It was a grim world of silence and dimness under the cloak of trees white with dust; the same dust was ankle-deep under feet, a thin wiry undergrowth gave up clouds of it. To the left of the path was a shallow precipice some five yards down, which gave upon a floor level as a billiard table, on which nothing, not even a blade of grass, was growing. On the opposite side of this plain, which might have been a quarter of a mile wide, the strange bank rose again and the trees, as if cut out of stone, stood statuesque. It was hard to believe that these were real trees and that their foliage lived and breathed. It was more like a stone forest, with a petrified river running between its cast iron banks.

Houseman dropped his burden at length and sat upon it. There was a queer flickering gleam on his face that startled Denn. He had seen that look before once or twice, and he knew what it meant.

"Come into the garden, Maud," he said, with a quivering laugh.

"Come into the forest and lie on the emerald grass and pick

violets. Nice and bosky, isn't it! Denn, you dog, give me water,

water, lots of it, or I'll strangle you."

"Give me water, water, lots of it!"

Denn deemed it wise to obey. To have a madman there on his hands in that awful place would be the last drop in the rank cup of despair. He poured out a liberal measure and Houseman drank it greedily. Afterwards his eyes grew more sombre and moody, and he turned his head away as if ashamed.

"Better if you had shot me," he muttered.

"I know the feeling," Denn replied soothingly. "I had it once in Cuba. I'll tell you the story some time. But the next time you want a good old carouse like the last, I shall have to shoot you as the least cruel way of saying no."

"Well, it doesn't matter. It's only drawing one's cheque in advance. When I look at those infernal grey trees stretching away to eternity my mind seems to turn to flame. Let us sit down and rest a spell."

Houseman suited the action to the word. Denn moved on till he came to the brink of the bank of the petrified river. He wanted to think a bit. But, before he had proceeded a rifle shot from his companion, he saw something that drove the gloom from his mind and set his heart beating with the fife and drum of hope. At his feet lay the fresh prints of human feet, a foot from which the right toe was missing. With the constant dropping and silting of the dust, that print was the matter of a recent moment.

"Man Friday with a vengeance," said Denn. "Johnny Walker has followed us. Johnny Walker is not far away. Doubtless he had instructions not to return until he had seen us across the bar. IF I can only lay my hands upon Johnny, it seems to me that we shall be able to receipt the account, after all."

Houseman thrilled at the good news. For the rest of the day all his vigorous manhood had returned to him. But as evening fell and no sign of the treacherous guide was discovered, gloom again claimed him for his own. And as the two flung themselves into a sleep that gripped them like a plague, they dropped with the consciousness, that their water was exhausted.

Denn woke with the red flush of the dawn in his eyes and a misery in his heart, such as he had never known before. The intense dry heat seemed to burn up the marrow of his bones, the grey forest trees as they showered their dust down covered him with a thick, hot, stinging film. He stretched out his hand for the water bottle, mechanically, and dropped it with a groan. It was his last day on earth, but what a hell was bound up in the leaden chain of hours!

Denn was aroused from his meditations by a cry from Houseman. The latter had stripped himself to the buff, and was dancing wildly on the shallow cliff overhanging the petrified river. He was a boy again in lush English meadows standing by the old millstream, his body bent for a plunge.

"For heaven's sake come back," Denn yelled. "You'll break your neck."

"Come and bathe," Houseman responded. "Lovely, cold as ice."

Denn ran forward, he made a grab for Houseman, but the madman eluded him. He raised his hands above his head, bent his body back, and shot off the cliff on to the grey stone below like an arrow from a bow. Denn stood waiting for his ill-fated friend to be dashed to pieces.

"Broken neck for a certainty," he said. "If only I had—"

Then Denn paused and gasped with an amazement that nearly suffocated him. For he saw, not a mangled, bleeding corpse below him, he saw nothing but a movement of the level floor of dust and the flash of Houseman's vanishing heels. The latter had broken through a volcanic crust and was plunging down to the bottomless pit.

Before Denn could formulate this theory, the thin crust wavered again and Houseman's head shot up again. It was a grimy, dirty, sooty-looking head, but it was wet, wet, and streaming with water.

"What on earth does it all mean?" Denn gasped.

Houseman responded with the light of reason in his eyes.

"I've solved the problem," he said. "I went off my head again, you know. I thought this was a stream of water and I dived for it. And it is water. We have been walking along this ice cold river for two days, and have never known it, so thick was the dust lying on the surface. Man alive, this is snow water from the hills beyond Shaz. And we took it fora petrified river, asses that we were."

Houseman dived deep again and ere he came to the surface Denn had plunged in by his side. Down, down he went in water clean as crystal and cold as ice. He came to the surface again, he knocked the black dust from the surface and then he drank deep of the stream which, indeed, was the stream of life. They were saved. They had only to follow the course of that silent river and they must emerge from the forest at length.

"What fools we are," Denn said, as he gazed at the stream now smooth as a grey floor again. "We might have guessed. Why, when I come to look at the river again I can see it gently moving."

Houseman pointed to an object far up the stream. It was a black round object bubbling up and down in the grey scum.

"That's the cause of it," he said excitedly. "And I'll bet my share of the ivory that that is Johnny Walker having a bathe."

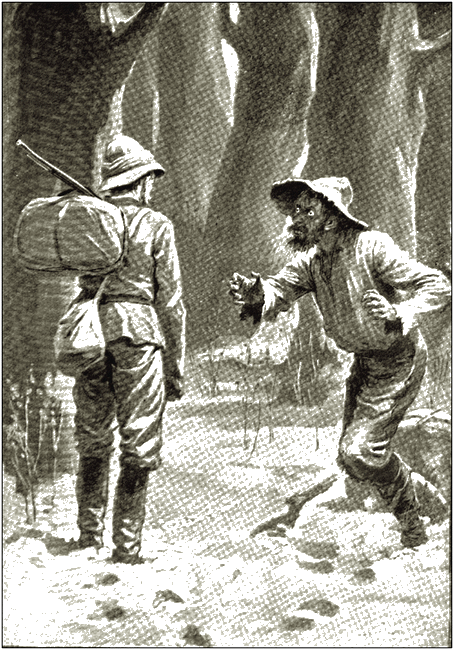

Without waiting tor the rest of his clothing, Denn reached for his Winchester and set off up stream like a deer. New life thrilled in every limb now. He ran wide of the stream, making a detour. Then he crawled to the edge of the cliff and poked the ugly muzzle of his rifle over. As he did so his eyes met those of another round frightened pair in a black head, reaching out of the stream.

"You had better not dive, Johnny," said Denn drily. "If you do

I shall plug you directly you throw up your arms. Please to swim

gently up here, and if you try any of your tricks I shall be

compelled to put an end to your interesting career, because we

can do without you now, Johnny. It means a little more delay, but

the fact remains."

"You had better not dive, Johnny."

Johnny came obediently. He was sullen and downcast, as he stood in considerable awe of the Winchester. For once, the glory of his wardrobe failed to show off the virile beauty of its wearer.

"What you do with me?" he asked.

"I don't know yet," Denn responded. "For the present I am going to chain you to the big baggage, the one you generally carry, you know. Meanwhile, you are going to get us out of this infernal region without delay and to Shaz as soon as possible. Come along, Johnny."

Two hours later the two travellers were beyond the region of the volcanic dust, and in a part of the forest where the trees were green and the great fresh-water lake sparkled in the lances of sunshine. To those accustomed so long to the terrors of the dust and gloom the change was delightful. A gaiety, unshared by Johnny, came over the party.

"What you do with me?" Johnny asked anxiously.

Denn smiled grimly.

"Your account comes for second," he said. "Garcia has the prior claim. When we have settled him, your case will be considered. As to Garcia, he will never see his happy home any more."