RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The English Illustrated Magazine, 1910

with "The Thug's Legacy"

"MY Uncle Seymour dead! Murdered! Strangled in his sleep! Oh, surely, surely it cannot be true, sir. There must be some strange mistake!"

This terrible, incredible news had been brought to me at my rooms in town by Colonel Sterndale, an old friend of the family. He had broken it to me cautiously, even gently; but I felt stunned and scarcely able to grasp the meaning of what he had told me. It seemed too cruel! Impossible! I could only repeat the words over and over again to myself and gaze, helpless and horrified, at the grizzled visage of the hard-looking old warrior seated before me.

Hard-featured he was, yet not unkindly. Just before, as he gave me his sad tidings, his eyes had softened and regarded me compassionately, and there had been almost a choking sob in his voice. But now the lines about his mouth had hardened, and his eyes took a steely glitter as he declared his determination to hunt down the murderer.

"It is only too true, boy," he said. "All that remains to us is the punishment of the black villain who has done this terrible deed. Heaven helping me, I will never rest till he has been discovered and punished as he deserves."

Then he rose, and, crossing the room, laid his hand on my shoulder.

"Come! Be a man! Rouse yourself!" he urged. "I wish you to assist in this matter. I want you to go down at once to Fareborne Hall."

"I?" I exclaimed, feebly. "How can I help. How can I go down there?" I still felt dazed, and unable to collect my thoughts.

"I wish you to go. I cannot possibly leave town yet—for a day or two. I desire you, therefore, to go in my place; to keep an eye on matters till I can come down. I have the power to send whom I please; I have thought it all over, and I propose to send you."

My uncle, General Fareborne, whose untimely death had been thus suddenly announced, had unexpectedly quarrelled with me and turned me out of his house two years before; and I had never seen him, scarcely heard of him, since. Moreover, he had, while sending me away, taken into his special favour another nephew, my cousin, Robert Burton, at the same time declaring his intention of making the latter his heir. Why he had acted thus harshly towards myself he refused to tell me; and I had never been able to discover. But bitterly as I felt and resented his treatment at the time, it had never effaced the remembrance of much kindness received at his hands during preceding years. Now, therefore, that I heard that he had been cruelly murdered, I forgot all but that former kindness; and I felt overcome with grief and distress.

I had had a hard struggle to get a living in London, but was succeeding fairly well; was even becoming resigned to my altered position and prospects, and accustomed to my new surroundings. The old life at Fareborne Hall seemed far off, almost unreal; and with the memory of it had died out—or, rather, perhaps, I should say, I had resolutely tried to crush out—many fond hopes and cherished aspirations. I had no wish to revive the recollection of what I then suffered; moreover, I knew that my cousin, Robert Burton, regarded me with anything but friendly feelings. He would be sure to look upon my presence as an intrusion, and, I felt pretty confident, would not hesitate at any insult in the hope of getting rid of me again. How, then, could I go down now, at such a time, uninvited, unasked, without even reason or excuse?

I pondered all these things in my mind, as well as the troubled state of my thoughts would allow, while still looking silently at my visitor. Then my ideas took a new turn, and I fell to wondering what Colonel Sterndale's object could be in desiring that I should go. For the matter of that, I had been wondering for the last two or three weeks as to why on earth he had sought me out at all in my lonely life at my London lodgings. He had been an old friend and comrade at my uncle's, and I had known him formerly also as a friend of my own father's. But, then, that had all been years ago. He had afterwards gone out to India, and I had seen nothing of him since till the other day, when he most unexpectedly called upon me, saying he had just returned to England, and was going down shortly to stay at Fareborne Hall with my uncle. I explained to him how matters stood between my uncle and myself, anticipating—my own parents being dead, and seeing that he was my uncle's friend—that what I told him would put an end to his sudden interest in myself. Instead, however, he had repeated his visits, had invited me to dine at his club, and had, in other ways, shown a friendliness that was, to me, in every sense a surprise. And I could not help wondering what could be the motives that influenced him in all this.

"Why, sir, do you wish me to go down there at such a time?" I at last asked him. "Everybody knows that my cousin is my uncle's heir. I have no expectation of so much as a small legacy. My cousin has long managed the estate—everything in fact—for my uncle. I have no locus standi in the matter. What possible reason, then, could I give for my presence there? I should only be ordered out of the place by Robert Burton; and," I added, slowly and bitterly, "I suffered enough of insult and humiliation at the time of my leaving there. I have no wish to run any risk of a repetition of such treatment."

"As to insult, I can't say," the Colonel replied. "If your cousin Burton is so unmannerly, or so ill-advised, why, of course, he may say anything. But humiliation—no. You go as my accredited representative; and you can hold your own."

"But—I don't see," I went on. "What, then, is your position?"

"I hold," said Colonel Sterndale, gravely, "a power of attorney to act for my dead friend, your uncle. It may be as you say; that your cousin is the heir, and that, in due course, everything will come into his possession and he will be master there. I say it may be so. But that cannot possibly be till the will is disclosed and proved; and that, again, cannot be for some little time. In the meanwhile my power of attorney overrules everybody and everything. It gives me the very fullest power; I can do as I like. I will furnish you with a copy of the document, and you shall see for yourself, and show it to your cousin. If either you or he entertains any doubt as to its genuineness, or the absolute authority it vests in my hands, you can, either of you, refer the question to General Fareborne's solicitors, Messrs. Fairlake and Carson, Lincoln's Inn Fields, who will very quickly and clearly settle it for you."

"I hold," said Colonel Sterndale, "a power of attorney."

"But why, then, did my uncle do this?" I asked, much bewildered, knowing that for long he had trusted everything implicitly to my cousin.

"That," Sterndale answered quietly, "is my business and his, young gentleman. You will perhaps hear some day. Meantime, do you accept the mission I offer you, or do you decline it? If you are going I wish you to start at once. You can call at the lawyers' on the way to the station, and they will confirm what I have now stated."

Still I hesitated. The errand was certain to prove both difficult and painful; and I could not see any good likely to result from it. Another pause ensued; and then I made up my mind.

"Colonel Sterndale," I said, "this mission, as you term it, is as distasteful to me as it is unexpected. If there were any good I could see likely to come out of it to my poor uncle I should not hesitate for a single instant. But I cannot see how that can possibly be. He is dead, you tell me, and nothing now can help that. I do not press for more of your confidence than you think proper to give me, but, I tell you plainly, frankly, this could not be other than a most painful, distressing experience for me. It is only fair to myself, therefore, that you should, as far as you can, let me understand what good end can be served by it. Could you not just as well send someone else instead? There are Messrs. Fairlake and Carson, for instance—could not one of their firm go, or one of their confidential clerks?"

But Sterndale shook his head, and, leaning forward in the chair in which he had reseated himself, he rested his elbows on the arms and his chin on his two hands, and, regarding me keenly and fixedly said—

"And why, Clement Fareborne, are you afraid to re-visit the place in which you have lived so long? Are you afraid to show your face there—have you done aught to be ashamed of?"

I looked at him in surprise.

"No, sir," I declared, at once. "Of course not."

"Can you tell me, Clement," he went on, with the same searching look, "why your uncle turned against you?"

I shook my head in my turn.

"I never knew, sir. I begged him again and again to tell me; I wrote letter after letter asking at least to be told that much, but never received even a reply. At last I had to give it up in despair."

"Humph! Well—why do you so object to go down now?"

I flushed up at this question, for I could not well answer it. It involved speaking of one I had long held dear—one I had even hoped one day to make my wife. But she, even she, had abandoned me, gone over to those who turned against me, and to-day she was engaged to my cousin. What use to speak of all this to my questioner? Why bring up this dead-and-gone hope to expose it, to exhibit all the depths of my buried misery to others? I could not bring myself to do it; and I remained silent.

But Sterndale would not be put off.

"Is it then," he went on again, "is it Miss Kate Elmore?"

At this I started up, angry and indignant.

"I really do not understand you, Colonel Sterndale," I exclaimed, as I turned away—for I felt a moisture coming to my eyes under a burst of recollections called up by his sudden inquiry. "I thought you came here to see me about my uncle, not to cross-examine me upon things that belong to myself alone, and cannot be of the least interest to anyone else."

At that he once more came over to me, and put his hand on my shoulder.

"Do not be vexed, boy," he returned, kindly enough. "You said just now you would not refuse what I ask if it could be of any use or advantage to your uncle who is dead. Suppose I say that it may be of great service to both Kate Elmore and her mother? They were friends of yours once—as I can see, and as I suspected; will you now refuse an opportunity of serving them?"

"No, sir," I declared, without hesitation. "If that be so—though I cannot see how it can be—painful as it must be to meet them again, I will face it, if, as you say, it can by any possibility serve them."

Colonel Sterndale smiled.

"Ha!" he said, a little grimly as I thought. "I have hit the right nail on the head at last, I see. Now, then, sit down and listen to my instructions."

Two hours later I was in the train, bound for Fareborne Hall, having called at the solicitors' on my way to the station. And the foregoing explains how I came to make the start; but why I was going I knew no more than I did when Colonel Sterndale first proposed to me what he called his "mission."

MY journey down to Fareborne Hall was, as may be supposed, neither cheerful nor pleasant. My mind was full of thoughts that were by turns sad, regretful, and crowded with unpleasant speculations. At times, too, there would creep in dismal forebodings, which, however, while I was clearly cognisant of their unpleasant character, never presented any definite ideas to my brain or assumed any tangible shape.

My destination was the town of G——, in Sussex, from which Fareborne Hall was distant about six miles. Though the spring was well advanced the weather was cold, dull, and cheerless; cutting north-east winds and gloomy skies had been the rule, day after day, and week after week; and these had retarded the spring foliage, which was scarcely more forward than it had been four or five weeks previously. Thus there was nothing to be seen from the carriage windows to interest the passing traveller; only a succession of bare, cheerless landscapes, from which one turned with a shiver to pull one's rug more closely round one's legs.

My thoughts ran much upon the terrible tragedy of my uncle's death; and the more I reflected upon it, the more cruel, the more incredible and incomprehensible did it appear. Before I left him, Colonel Sterndale had given me such particulars of what had happened as he himself had been able to learn. But they were naturally very meagre, being, in fact, all contained in two hasty letters received, one by him, and one by the solicitors. It seemed useless, therefore, to speculate at present as to what the motive or who the murderer might be. One or two things I ascertained, however. One was that my uncle, General Fareborne, had paid a brief and hasty visit to London about a fortnight previously, when he had met Colonel Sterndale at the solicitors' offices. Another was that my uncle had been suffering from what was believed to be an incurable complaint; and he had been laid up by a severe attack of this malady at the very time he was murdered. This last illness, it was believed, would most likely have proved fatal in itself, and therefore, if he had not been thus barbarously murdered, it was most probable he would never have risen from his sick-bed. It was, I gathered, some premonition of this that had led to his sudden visit to town and to his signing the power of attorney which he had entrusted to the colonel. But when I endeavoured to think of a reason for such a step I found myself lost in a maze of conjectures without any clue whatever to guide me; for on this point the colonel had remained quite dumb, and had not in any way enlightened me.

After much consideration, and after rejecting many wild guesses, I at last formed a theory which appeared to me to be the only one that fitted itself to the facts, so far as I knew them. In the first place, it was clear there was some antagonism between the colonel and my cousin, Robert Burton. That must be so (I said to myself), or why should the colonel wish someone to go down, to keep an eye on things? Now, how could this antagonism have arisen? Only, it seemed to me, through some clashing of interests. Let us suppose (I said) that Colonel Sterndale expects to benefit to any considerable extent under the will; or (here a bright idea occurred to me), let us suppose that somehow or other my uncle has been indebted to Sterndale in some large sum which had remained unpaid so long as the colonel was abroad. Finally, he returns to England to claim it. He cannot obtain it at once; finds the general in weak health, and likely to die suddenly; is given the assurance that in the latter case he will receive it under the will; but, dissatisfied with this, asks for a guarantee, and obtains the power of attorney. This would be given to him as a security that Robert Burton should not take precedence in any way (I knew my uncle's estate was not large), or have a chance to dispose of any of the property without Sterndale's consent.

So I reasoned. Certainly it was a theory that did not quite account for everything. But I accepted it as the only one that seemed tenable; and, having done so, I gave up, for the moment, further speculation upon the point, and turned my thoughts to Mrs. Elmore and her daughter, Kate.

Ah! Kate Elmore! Now that I was likely to see her again, what a rush of memories her name aroused! Ghosts—hosts of them—the ghosts of hopes long dead and buried rose up to torment me! Memories, too; what memories! That walk across the moor in the summer sunshine when I first pressed her hand, and she did not withdraw it; that moonlight row on the lake when I stole my first kiss; those dances, wherein, whenever we danced together, or met in "ladies' chain" or the "set to corners," a hidden hand-squeeze or tender pressure would be exchanged, that meant so much to us, while, to those around us we were only dancing as the others danced. Ah, me! And then to be jilted after all! Yet I know that I loved her still; and, traitress as she had proved herself to all that she had allowed me to believe of her as regards her love for me, I could not refuse to see her again so soon as I was told that by so doing I might be rendering her a service!

But how? And how could any benefit to her be mixed up with Sterndale's position as I had settled it in my own mind? Could it be that, after all—but no! Colonel Sterndale was a gentleman; he could not, surely, stoop to so mean a thing as to pretend what was not true, merely to induce me to go down to Fareborne about his own selfish concerns. And so the puzzle still seemed far from clear; and I was uncomfortably conscious that the plausible theory I had invented left, at least, one great gap which I could in no way fill up to my own satisfaction.

And then I went over everything again from the beginning, coming to the same stopping point, and beginning yet again; my thoughts travelling ever in a circle, again, and again, and yet again, till my head ached, my very brain seemed to reel. I felt at last quite sick, and more upset and troubled than I can well describe.

Thus the journey passed, and I arrived at last at G——. And glad I felt then that the moment for action had arrived, and that no further time was now left me for useless speculation. Henceforth all my thoughts, all my wits, would be wanted for the work in hand, for observation and for action. For I was quite as keenly resolved as Colonel Sterndale had stated himself to be, to do all that human energy could effect to hunt down and bring to punishment my uncle's assassin. Having secured a fly—it was an open one, the only one to be had—I directed the driver to take me, not to Fareborne Hall, but to the "Crown inn" at the village of Lowwood, which was about a mile from the hall. Here I proposed to leave my luggage, temporarily, while I looked about, and made a few preliminary inquiries. Among these would be—at the colonel's suggestion—a visit to the local police-station to ascertain whether a detective had been put upon the case, and, if so, to endeavour to have a talk with him. Then I could walk quietly over to the Hall, and see what was going on there.

This plan, however, was upset by a very unexpected meeting with Robert Burton himself upon the road. He was on horseback, and was riding at a walk, with loose rein, and apparently in a brown study. His face was gloomy, and its expression anything but pleasant. I noted, too, that he had changed greatly since I last saw him. He looked many years older, and there were certain lines and other marks on his countenance that told to me a tale of dissipation, mingled with worry and trouble of some kind. Altogether, his appearance was not prepossessing; yet, two or three years before, he had been a good-looking fellow enough, if somewhat surly and bad-tempered at times. He was about my own age—then twenty-seven—was well built, of middle height, and dark. Indeed, his skin might almost be described as swarthy.

I should have passed him had he not looked up, for I should have preferred just then to defer a meeting. Besides, it would have enabled me to have gone on to the Hall, and pay my first visit there in his absence—which might have given me a decided advantage in the game I had come to play. It so happened, however, that he looked up at the moment, and caught sight of me as I was looking steadily and curiously at him.

He pulled up his horse with a jerk that nearly sent them both into the ditch.

He pulled up his horse with a jerk.

"The devil!" was his polite exclamation, by way of salutation.

As I could not very well take the remark as intended for myself, I remained silent, waiting for him to adopt some more civil form of greeting. Meantime, the fly went on, and we passed him.

Thereupon he wheeled his horse round, and, with an oath, shouted to the driver to stop; which he did. Then Burton came up beside me, and, regard me with a scowl, demanded—"What the deuce brought me there?"

That was all. No cousinly greeting; not even a pretence of friendliness. It was an open and, moreover, a very offensive declaration of war. As such I regarded it; and at once took up the implied challenge.

"Since that is all the welcome you have to extend to me, Robert," I said, quietly, "permit me to ask by what right you stop my carriage and question me upon the King's highway? The road is free to all, I imagine?"

At this he stared. I spoke without the least show of heat or annoyance, and the words were without offence in themselves; they were indeed natural enough in the circumstances. But I managed to throw into them the suggestion of assurance, even of a latent meaning, which did not escape him. I could see he was surprised, taken aback. For a space he was silent; then, his temper getting the better of him, he burst out again:

"Don't 'Robert' me," he began, but he looked so amazed that, in spite of myself, a half smile came to my lips. And, as he paused, and once more stared in surprise, I seized the opportunity to put in:

"Very well; since you wish it, I won't again. In future you shall be 'Mr. Burton' to me. And for that, perhaps, later on, you may have reason to be sorry."

This cool answer seemed to take away the remainder—there hadn't been much left—of his self-possession. He lost his head completely, and launched out into a torrent of words.

"How dare you!" he burst out.

"You—you—you—" Here he seemed at a loss for a suitable adjective; so went on: "I say again, what is your object in coming here? If it is to come to the Hall—to see me—you had better at once turn round and go back. For if you venture to show your face there, I'll—I will have you turned out by my servants, and ducked in a horse-pond to boot;" and much of the same kind of thing, mingled with a great deal of personal abuse. I, still smiling, let him run on till he could find no more words. Then I spoke sternly and slowly:

"'Mr. Robert Burton, I am coming to the Hall, and I am coming partly to see you, partly not. What is more, I am coming to stay; and the servants—not yours, they are not yours yet, my Billingsgate-tongued friend—the servants there will not turn me out, but will, for the present, at any rate, do my bidding, and not yours—by virtue of a warrant I bring with me. And just let me add this; you will please to drop this bluster, and make up your mind to see me there and listen quietly to my statement of my business. Otherwise, if I have any more abuse or threats, I shall bring a policeman with me."

At these words, to my utter astonishment, I distinctly saw him turn deadly pale and actually tremble. He seemed dazed, cowed. All the insolent swagger vanished; his head drooped forward, and his riding whip fell from one hand on to the road. He seemed to seek blindly with the other for his handkerchief, to wipe from his face the perspiration that I could see gathering on it. He stared blankly at me, then on the ground, first to right of him, and then to his left, but did not again raise his eyes to meet mine.

I was more than satisfied with the victory I had gained, and turned from him with disgust.

"Drive on," I said to the driver; and he went quickly on at once, leaving Burton still standing, as though dazed, at the side of the road.

"Well," I thought, "that's the first 'round,' as they say, and I've got the best of it, so far, anyway! All the same, though," I added to myself, thoughtfully, "what the deuce could have frightened him so?"

I went over all I had said until I came to the word "warrant," which, on the spur of the moment, I had used where I ought, perhaps, to have said "authority." "H'm," I said, "he winced at that; and so he did at the word 'policeman.' Now, what on earth can Master Robert Burton have been up to that he should be frightened at the threat of a 'warrant' and 'policeman.'" I couldn't guess. Of course, any suggestion that he could be guiltily concerned in any way in the murder of our uncle was absurd on the face of it, and though it crossed my mind for an instant, I dismissed it at once. It seemed only too likely that the poor old gentleman must have died soon in any case; and then, as Burton knew, all was to come to him. It was ridiculous, therefore, to suppose that any sane man so situated would dip his hands in blood and run all the fearful attendant risks, merely to step, a week or two or a month or two sooner, into what was so surely coming to him of its own accord.

"No," I mused, "such a suspicion is too preposterous; but, there's something. Master Robert has been up to some mischief—got into a bad scrape somewhere—and is in mortal terror of its being found out. He thinks I have got an inkling of it, which, of course, is absurd, and he's given himself away. But, my friend, I will get to the bottom of it before long, if patience and perseverance can do it, see if I don't."

Then I heard behind me the sound of horse's hoofs doming along at a swift gallop, and a few minutes later Robert Burton dashed past. He gave no look at me as he went by, but simply tore on, straight ahead, as though riding for dear life, and lashing his horse unmercifully.

"He's got over his fright, and is in the deuce's own temper," I thought to myself, "and, as so many cowards do in like case, he is visiting his ill-humour on a poor dumb creature. Altogether, this 'mission' of Colonel Sterndale's is likely to prove an interesting and exciting piece of business."

WHEN I arrived at the "Crown" at Lowwood, I found the house had changed hands; everyone I had formerly known about the place had gone, even to the boots and ostler. All were strangers; and, perhaps (as I put it to myself), it was as well, since my arrival would give use to all the less immediate gossip. Having engaged a room, and had a wash and a hasty meal, I went over to the police-station, which was nearly opposite the inn, and there chanced to run against the detective who was engaged in investigating the circumstances surrounding the tragedy at Fareborne Hall. He was, he told me, about to return to the Hall again, having only come from there a short time before to send off some telegrams. I suggested we should walk back together, and have a talk by the way, to which he agreed; and a few minutes afterwards we started.

His name, he told me, was David Clitchet, and he had arrived from London the day before. He was a thin, spare man, with a shrewd face, but not otherwise particularly interesting or noticeable. He was clean-shaven, and had fair hair turning to grey. I noticed that much at the time; later on I found his face could exhibit very strong character when he allowed himself to become in any degree animated—which, however, did not often happen. As a precautionary measure, I took him over to the inn and showed him the original power of attorney given by my late uncle to Colonel Sterndale, and the latter's letter of authority to myself, and made him compare them with the copies I was carrying with me to show to Robert Burton.

I had hoped—or, rather, expected—that, during our walk to the Hall, Clitchet would have told me all there was to know concerning what had occurred—and, in particular, what suspicions, if any, he himself entertained. Instead, however, we had nearly reached our destination before it was borne in upon me that he had told me substantially nothing whatever, while, somehow, I—without intending it—had told him nearly everything that concerned me or interested myself. He had, in fact, "drawn me out," as I clearly saw, both skilfully and thoroughly, without my being aware of it; and now, when I turned round and began to question him with directness, I elicited from him nothing but the vaguest information; and what I did obtain was more the repetition of gossip current in the neighbourhood than that exact knowledge or opinion of his own that I industriously sought to extract.

I felt a little piqued, and somewhat annoyed with myself besides. But, since I could not "draw him out," as he had me, I had, perforce, to be content with what he chose to tell me. And, since I wished to gain him over as an ally, in a sense, against Burton, it obviously would not be policy to show irritation. Besides, I could not help feeling a little amused at the evidence the man had given me of his cleverness in his own particular line.

We went up to the main entrance of the old Hall—accounted one of the finest country seats in all that part of the kingdom—and as we drew near I could not help reflecting upon the mutability of all human affairs. He who but yesterday—or two or three days since—had been the unquestioned master of this magnificent English home, of all its servants and horses, carriages, and broad acres, now lay dead—not only that, but with all his wealth, with all his servants, he had been unable to defend himself even against a prowling midnight assassin!

The door was opened to us by Drummond, my late uncle's butler, who first stared at me as if I had been a ghost, and then almost wept tears of joy at seeing me once again. For a few minutes he could scarcely speak coherently; only mumbled out his grief and horror at his master's untimely death. Then, growing more calm, he went on more clearly:

"I've wondered often where you was and what you was a-doing of, Mr. Clement," he said, "and whether I should ever see you again. But now I be main glad you've come back, an', are ye come for good, sir? If ye be, that'd be better news still, to all of us, for—except, perhaps, Sleave, Mr. Robert's own man—there isn't a servant in the place but'd jump out of his shoes with joy to see ye back again in your old proper place here, sir. We all of us liked Mr. Clement best, ye see, sir," he explained to Mr. Clitchet, "an' we've found out lately, more than ever, how right we were—since, that is, we've had Mr. Robert an' no one else, as one may say, over us."

Clitchet gave an appreciative nod, but did not commit himself to the expression of any comment. But then, turning suddenly on the butler, he asked:

"By the way, Mr. Fareborne here wishes particularly to know whether you can tell him if his uncle went up to London on or about the 30th of last month?"

Drummond glanced askance at me and looked doubtful. But I made a gesture of assent—I saw the detective was sharper than I was, and that this was an astute and important move.

"Well, sir," Drummond presently replied, after much hesitation, and almost in a whisper, "yes, he did; but no one knows it but me and John, the head coachman."

Clitchet sagaciously nodded his head, and we walked on. Drummond, leading the way, took us direct to what had been my uncle's study, where he told us Mr. Burton was awaiting us.

Clitchet would now have held back, but I whispered to him to go in with me.

"I have told you nearly everything—in confidence—as you know," I said. "Better, therefore, you should remain with me and see what happens."

"As you please—if he does not object," he said, briefly.

"All the same, if he does," I answered, firmly, "I shall insist."

Robert Burton was standing with his back to the fire as we now entered, and seemed to be engaged in the occupation of biting his nails. His set scowl grew deeper as he saw the company I was in.

"I think," he began, ungraciously, but quietly, "that we can dispense with this person's company."

"Not at all," I returned. "I have found this gentleman very good company indeed, thus far; and I prefer that he should now remain with us. After the display of temper you treated me to to-day, I think it will be best, in case matters get warm again, to have a witness present."

"Oh, very well," he returned, sourly, "if you don't mind his hearing what I have to say. And now I put again the question I asked you to-day, what is it that has brought you here?"

He was in a more cautious mood, evidently, than that which had swayed him when we had met on the road. He felt he had then been too hasty, and that he had come off second-best in consequence. Now, therefore, he was sulky and quiet; but, I could see, watchful and alert. He was only waiting for his opportunity, should it offer.

"I am glad to see, Mr. Robert Burton," I began, deliberately, "that you have taken to heart the advice I gave you when we met to-day. I told you I intended coming here, and advised you to receive me civilly, and to listen to what I had to say."

"Will you go on?" he blurted out, impatiently, as I paused.

"Yes, but again I advise you not to lose your temper. It will be sorely tried directly. For answer to your question, I request you will read these papers." And I handed him the copies of the power of attorney, and of the letter from Colonel Sterndale delegating me to act for him.

As Burton held out his hand to take the documents I saw that it trembled, and his face went pale. No sooner, however, had he glanced at them than he evinced relief. Turning to me with an ugly look, he cried out:

"This is rubbish—a mere impudent forgery! Somebody," darting a threatening glance at me, "will get into trouble over this."

"It is no forgery," I told him, calmly. "It was executed by Uncle Seymour at the offices of his solicitors, and was duly attested by them, as you perceive, on the date named."

"It's a lie, I tell you!" he almost shouted. "An infernal lie! General Fareborne has never been away from here any time in the last six months. That I can swear to."

This was said with such a theatrical air of triumph that I could scarcely refrain from smiling. I now, however, appreciated more than ever the foresight of the detective.

"Drummond can tell you differently," I said, coldly, "if he chooses. So can the coachman, John. Perhaps you would like to question them. But meanwhile, it might be simpler to consider whether you yourself were away at that date."

This idea had come suddenly into my mind; and, as it turned out, it was a happy thought.

He glared at me for an instant, started slightly, and then, going over to a writing-table, took out of a half-open drawer a book that looked like a diary. He turned over the leaves in feverish haste, stopped suddenly, and seemed to compare an entry he found there with the date named in the papers in his hand.

Then, once more, he turned pale—paler than I had as yet seen him; the triumph died out of his eyes, and he glared at me with the hate and rage of a furious tiger.

"You infernal—!" he hissed out, with an oath. "You set of swindling blacklegs—the whole lot of you. This was a little conspiracy, was it? And you thought to take advantage of the old man's dotage; you must have used some unfair influence with him to induce him to sign a paper like this! I daresay you held a pistol to his head or something. You are capable of anything, you, Fareborne, we all know that. Wait till I—ah, we'll see who's cleverest over this! Here's checkmate to that little game."

And springing suddenly up, he rushed to the fire-place and threw the two documents in the fire.

Or, rather, tried to; but Clitchet had been on the watch, and was too quick for him. For, as he threw the papers, the detective pulled him suddenly back from behind, with the result that the sheets fell short and fluttered down into the fender.

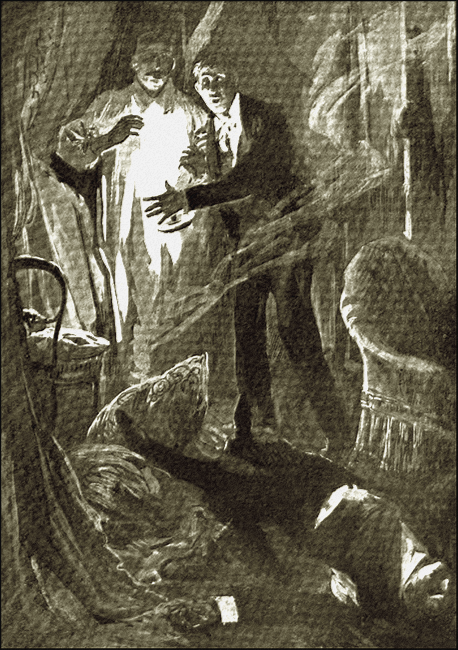

Clitchet was too quick for him

"Steady there, Mr. Burton, steady!" Clitchet observed, coolly, as he went and picked up the documents. "Lucky for you that these are only copies, or you might have got yourself into trouble.

"Copies!" Burton repeated, with a baffled look.

"Yes," I said, "copies; as you might have seen for yourself if you had not been too much interested in calling names to read them properly. Had you done that, Mr. Robert Burton, you might have saved yourself this piece of—well, shall we call it folly?"

He turned away, and went and sat down again in the chair, where he leaned his elbow on the table, and with his head on his hand remained awhile in thought. I looked at the fire, while Clitchet affected to study the pictures on the walls, but keeping, I could see, a sharp eye on Burton all the time. Presently Burton looked up and spoke in a low tone, as one who sulkily acknowledges he is beaten.

"What do you want? What do you want?" he repeated. "Take care what you do. I see your little game; but remember, I shall be in legal possession here shortly, and I'll hold you responsible then for whatever you do now, and make it hot for you; see if I don't!"

Then ensued a good deal of talk and argument, into the details of which it is scarcely necessary to enter. In effect, I informed Burton that my instructions were simply to insist upon all papers, documents, valuables, etc., being put under lock and key and sealed up, or deposited with General Fareborne's local bankers, in his and Colonel Sterndale's joint names, till the executors came to take possession of them.

"If you like," I concluded, "to do this at once, jointly with me, without any more fuss, it shall be effected so quietly that not even the servants shall guess my mission here, or the temporary authority I have been invested with. But if you resist any further—or if I find you trying to play me false in regard to such as one little thing of the value of sixpence, my instructions are to call the servants together, explain the position, show them my authority, and order them to turn you out, neck and crop, then and there, and take sole possession of everything in Colonel Sterndale's name. And, Mr. Robert Burton, I need not remind you, you are not so popular here that any doubt can exist that, when they see my authority, and hear how matters stand, the servants will obey me."

And to this he had, perforce, to submit; and thus, in the end, a sort of truce was agreed to, upon the terms I had indicated.

"Phew!" whistled, or, rather, gasped Mr. Clitchet, as we walked through the hall together. "It was like taming a tiger, wasn't it, sir? And nearly as dangerous, too! More than once I half expected to see him fly at your throat, or bring out a revolver and shoot you down, or something as wild. I watched him like a cat does a mouse."

"I know you did, my friend," I answered. "I could see it; and I felt all the safer for it, and now I thank you. I agree with you that Mr. Burton is dangerous. Yet," I added, reflectively, "he used not to be so. I can't think what has come to him."

"In my opinion," said Mr. Clitchet, "that man is not to be trusted an hour. I believe he is scarcely responsible for his actions. At times there is a gleam in his eye just like a savage tiger. I mean to go on watching him."

And this was the man to whom the girl I loved was engaged to be married!

IN writing out this narrative of the tragical drama in which, by what seemed to me a strange chance, I became an involuntary, almost an unwilling, actor, I have described everything, thus far, fully, because all the details up to this point were strongly impressed upon my mind, and remain, even to-day, as vivid and distinct as ever. But the after events succeeded each other so rapidly, and were of so startling and exciting a character, that my recollection of many minor matters is somewhat confused; and I doubt whether, even if space would allow it, I could, to-day, put down with absolute clearness all that occurred. I mention this by way of explanation in case it should seem that I have devoted more space to the commencement than to the ending of my tale. It is often thus in regard to exciting events generally. Take a battle, for instance. Those engaged in it, or some of them, may be able to give every detail of the movements of the troops they were with, of all the dispositions, the marchings and the counter-marchings, up to the very commencement of the fight itself. But from that point their memories become uncertain and confused. They have vague recollections of fighting, of assaults, of hot, fierce encounters, and of noise, smoke, and bloodshed; and they know the eventual outcome; but that is about all. How the result was arrived at, those who were in the thick of the battle are usually found to know very little indeed.

I know, with regard to myself, it was very much this way with me in the few eventful days that followed my arrival at Fareborne Hall. Yet, I suppose that if I could now clearly recollect it all, and were to write it all down, there would be enough to fill a three-volume novel.

But one thing at least is vividly depicted in my memory; and that is the visit I paid to my uncle lying in the room in which he died. Well would it be for me that it were otherwise; for, to this day, the sight I saw haunts me; aye, and will haunt me to the day of my own death. Dr. Rumford, who had been my uncle's medical attendant for many years, happened to call in about the time I left Burton, after our disagreeable interview, so I went in with him and Clitchet. I have no wish to dwell on horrors; and, therefore, I shall not describe what I saw. It is sufficient to say that I came out of that room faint and sick and trembling, and old Drummond and the others led me into the butler's pantry and forced me to swallow a very strong dose of brandy. There is one remarkable circumstance, however, which occurred during this visit to the dead, that I must not forget to mention, since it has much to do with the final ending of this strange history. Dr. Rumford pointed out the marks on the throat and the unmistakable inference to be drawn from them.

"The strength exerted must have been enormous, extraordinary!" he declared "The murderer must be a man of very great, indeed, of altogether abnormal strength; for our poor friend here was strangled by the grasp of one hand alone. This is, I believe, the only clue the police have as yet to guide them. They have to look for a man of quite uncommon strength; and, therefore, presumably, of large and powerful build. Now, where are they to search for such a man? Obviously, every tramp they come across who is above the usual height and more than ordinarily strongly built, becomes, under the circumstances, an object of suspicion. Is it not so, Mr. Clitchet?"

But that astute gentleman, with his habitual caution, declined to commit himself to any opinion; and nothing further was then said upon that particular point.

As regards my own immediate task, it now turned out easier and less disagreeable than I had anticipated. Burton, it seemed, had already sent for an accountant, a man he knew in the neighbouring town of G——, and had given over to him the work of examining, cataloguing, and locking up, everything of value; why I could not guess. However, there he was; and Burton simply turned me over to him. His name was Mason, and I did not much like him; but he was civil enough, and it was much better to have to do with him than with Burton, whose ungovernable temper would, I knew, have inevitably caused constant wrangling and unpleasantness.

Thus it came about that I saw very little of Burton during the following days. All that day and the next one I was closeted in one room or another with Mason, and Drummond brought us our meals, of which we partook together, Burton preferring, if he was in, to have his alone. The first evening I went over to the inn to have a bit of homely dinner and to sleep. But the next day, at Mason's suggestion, Drummond prepared a bedroom for me at the Hall, and sent for my luggage. We should get on faster, Mason suggested, if we worked in the evenings. I had reason to believe, afterwards, that this was put into his head (or, rather, I should say, perhaps, into his mouth) by Burton.

An inquest had been opened before I came down, and adjourned for a week. The funeral had been fixed for the following Saturday. That would be five days from my own arrival at the scene. This I notified to Colonel Sterndale, who would, I knew, be sure to attend it, even if he were prevented from coming down sooner.

Of particulars of the murder itself, of the investigations of the police and detectives (there were now two on the scene—at least, so it was understood; I did not see the other one) there is singularly little to be told: My uncle had been found strangled in his bed; the window was open and the place in disorder. A safe and various drawers had been opened with keys taken from the victim, and the place ransacked. What had been stolen could not be exactly ascertained as yet. Robbery seemed to have been the object; that was all that could be guessed at. General Fareborne, though undoubtedly very ill, had obstinately refused to have any nurse at night. Had he only engaged one to sit up with him, or even to sleep in the adjoining room, probably he would have been alive still.

As for the rest, the police were making every effort, and believed they had a clue, etc., etc.

Of Mrs. Elmore and her daughter—who lived at a house about a mile and a half from the Hall—I only heard that they had been very much shocked and upset at the news of General Fareborne's tragic death, and had scarcely been seen out of doors since.

I had some thought as to whether I should leave a card there to let them know I was in the neighbourhood; and I was inclined to think it better not to do so. But yet I hesitated; and at last I spoke to Drummond about it.

"Go an' see 'em, sir; go an' see 'em," he said. "I'm sure they'll be glad to see ye, Mr. Clement."

But I felt doubtful; and, in the end, I sent my card by one of the servants, with instructions to leave it, and that was all.

That was my second day there; and that night I was sleeping at the Hall. When I went upstairs to my bedroom Drummond went with me, "to see," as he said, "that I was comfortable."

He appeared, I remember, unusually silent that night; yet he seemed loth to go, and kept fidgeting about for some time. But at last, when he saw me give a very unmistakable yawn, he said, quite suddenly, as though he had been hesitating, and had just made up his mind to it:—

"Mr Clement, sir; ye asked me to-day about Mrs. Elmore and Miss Kate—God bless her! Ah, sir, why did ye ever go away, and leave her?"

Taken by surprise, I scarce knew how to answer him. Then I said—

"Do you suppose it was my fault, Drummond, that I went away? My uncle sent me away; and—you know how she become engaged. I—" But I felt I could not go on. "You don't understand," I managed to get out.

"No, Mr. Clement, I didn't understand then; but I do now. I seem to see everything more clear like to-night. Other people are beginning to see things more clear, too, sir; have seen and understood better for some time past. Well, good-night. Mr. Clement; good-night, sir, and good luck. An' it's comin' too, for ye, sir—the good luck I see it comin' to ye, sir; an' to Miss Kate. Good-night, sir, and God bless ye both!" And he suddenly turned, and went out.

Poor Drummond! I never saw him again alive! These were his last words to me—words full of good wishes, and fraught with kindly meaning—spoken to me freely, with the privilege of an old servant who had known and liked me from my boyhood. I thought of them afterwards with wonder, and almost with awe. But at the time I only smiled indulgently, and sat for some time gazing at the fire in a daydream—dreaming dreams that his words had called up, but which I knew, alas, could never come true for me!

The next morning I was awakened early by a great uproar that seemed to be going on. There were shouts and cries, and the noise of many people running to and fro in the house. I could hear, too, through the window, the sound of horses and vehicles being ridden or driven hastily away. I began to dress hurriedly to go down to see what it was all about, when one of the men-servants rushed hastily into my room, and, with eyes that seemed to be nearly starting from his head, told me that Drummond had been found dead in his bed—dead—murdered, just as General Fareborne had been!

He rushed away again without stopping to say more, and I was half inclined to think he had gone out of his mind, only that the strange noises going on around showed that something unusual was amiss. Scarcely knowing what I was doing, I went on dressing, and had nearly finished, when someone knocked at the door, and going to open it, I found Mr. Clitchet there.

Briefly, he confirmed the incredible news, while I dropped into a chair, and sat staring at him in shuddering horror.

"Do you mean to tell me," I asked, at last, "that the same foul assassin, even while you and the police are hunting for him, east, west, north, and south, can have the audacity to return here, in the middle of the night, and slay another victim, and then again get clear away?"

"It seems to be so," he answered. "At least, either that or he has never been away—has been amongst us all the time—may be amongst us still."

"Good heavens! You make me shiver, man! What are you doing—what are we all doing that such a thing can be possible! But, no! It cannot be; such a thing is absurd."

He looked at me, curiously, I thought, but said little more, and soon afterwards went away, and I finished dressing, and went down.

Well, it was all only too true! Poor Drummond lay dead—strangled—with precisely the same marks as those left by the murderer upon my uncle. In this case, however, there had been no robbery or pretence of it. It appeared to have been the work of a madman, for what sane motive could be imagined for such a crime?

More police and detectives were telegraphed for, and arrived in the course of the day, and went about their investigations and examinations. The whole place was now in their hands, and they seemed to be everywhere in it at once. Meantime, everything appeared to be disorganised. The servants troubled little about their usual duties, but passed the time whispering together with scared faces in corners, or watched the detectives, to and fro, as though trying to read from their faces or their movements the suspicions that they might be nursing in their minds. And not only was there this sense of disorganisation abroad, but there was a feeling of mutual suspicion in the air; everybody distrusted everybody else—even the fellow-servants, who were talking and comparing notes in low tones, in the corners and passages. And it was difficult to induce the maid-servants to go about their work at all; and then they insisted upon going in couples, fearful that, if alone, the "strangling monster," as they termed the unknown murderer, might spring upon them suddenly from the shadow of some remote corner or doorway.

As for myself, I was far too restless and too much upset to think of sitting down again to the work I had been engaged upon the day before. Going once into the library, I found Mr. Mason imperturbably engaged in cataloguing the books; but when he asked me if I were coming to assist him, I turned away with an impatient exclamation, and left him. I spent the day in wandering restlessly about; all the servants, with one or two exceptions, knew me well, and all had something to say or to ask as I went from the house to the garden or stables, and back again to the house. Then I went twice, I remember, to the village and back, and there it was the same. Everywhere I met people who knew me, and showed by their greetings their pleasure in seeing me again; and all these asked questions which I could not answer. Of Robert Burton I saw nothing; I did not run against him in all my restless wanderings to and fro.

Towards evening, Mrs. Cope, the housekeeper, sought me out, and somehow managed to come across me. She was in terrible distress, poor thing, for the loss of Drummond; they had been fellow-servants for many and many a long year, as she reminded me; and his terrible end, coming so closely upon what had happened before, had been a great shock to her. She said she had prepared some dinner for Mr. Mason and myself, and that it would be ready at seven, and she hoped I would excuse it if it seemed a homely meal, since everything was "at sixes and sevens." I told her I quite appreciated the difficult position she was in, and that, so far as I was concerned, she need not have troubled; I could easily go over to the inn. Indeed, I had been seriously thinking of returning there to sleep. But this seemed to quite hurt the old lady; so, in the end, I consented to stay on, and to come in punctually at seven. Then I went out, and walked to the village and back again; not with any definite object, but simply because I could not settle down anywhere, or keep still. I had some dinner with Mr. Mason; it was a short, silent meal, neither of us being inclined to talk; and then I lighted a cigar, and sat down to try and read a book I had taken up. Instead, I fell asleep, and must have slept for some time, for it was after nine when I was awakened by the entrance of Dr. Rumford. By the way he looked at me, I saw at once that he had some fresh news to communicate.

"Why, doctor, what is the matter?" I said confusedly, for I was scarcely yet awake. "Has anything fresh happened?"

"I am sorry to say something fresh has happened, Mr. Clement," he returned gravely. "Miss Elmore—"

"Kate, Kate Elmore?" I asked breathlessly.

"Yes; but now, don't get excited. She is all right—at least—that is—"

"What?" I cried impatiently. "Tell me, doctor, for heaven's sake!"

"Keep calm, Mr. Clement; I want you to do something, and I can't explain if you keep jumping down my throat like that! A dastardly attack has been made on Miss Elmore; but, thank Heaven, it failed, and she is more frightened than hurt. There is, indeed, no danger to her, as things have turned out, unless, you understand, the fright and shock should bring on complications—as, of course, might be the case."

I could not speak for some moments, so tumultuous were the emotions that filled my mind. It took me a space to comprehend what he had said. Then I asked rapidly—

"And what, then, was the attack? Who attacked her? Was he caught?"

The doctor shook his head. "We know nothing," he said. "Some miscreant attacked her suddenly from behind, just at dusk, as she was returning home along the path that runs to Lowwood through the Redfern Copse, as they call it. She screamed out, and, fortunately, a labourer passing near heard her cry, and ran to her assistance, whereupon her assailant made off, and disappeared in the wood before he could be recognised. Joyce—that is the labourer's name—carried her to the stile, where he saw some men coming along the road below, and called to them. They came up, and between them carried the poor girl home, in a dead faint. One of them came across to me, and I went to see her at once. At first she came out of one faint only to fall into another; but she is better now. I have just come from there."

Joyce carried her to the stile.

I began asking more hurried questions, but he cut me short.

"I have come here," he said, "to tell you that Mrs. Elmore wishes to see you. Can you go over there at once?"

"Certainly; and only too pleased if I can be of the least use or assistance to her," I returned.

"Then go now; and tell Mrs. Elmore I shall be sure to call again before I go to bed to-night, however late my visit may be."

I did not tarry, but hurried off then and there. Though it was dark, I took the field path—it was well known to me—as being scarcely more than half the distance of the road route. It branched into the path from Lowwood, and led through the same wood, so that I knew I should pass the place where the attack had been made. I ran nearly the whole way, so full of excitement and impatience did I feel, and once or twice I stumbled and fell over the roots of the trees. And then, in the sudden stillness, as I picked myself up and stood still for a moment, I fancied I heard someone following me. I saw no one, however, and going on at a jog-trot soon arrived at Rosedale, Mrs. Elmore's residence.

She came to me in the drawing-room, to which the servant had conducted me, and greeted me kindly but tearfully. After some preliminary talk concerning Miss Elmore's condition, which, she said, she was thankful to be able to tell me, did not appear to be serious—she came to the reason that had induced her to send for me.

"The truth is, Clement," she said, calling me simply by my Christian name as of old, "we are all in a terrible state of upset and distress here, and I know not whom to trust. I understand that you are in direct communication with Colonel Sterndale—are, in fact, acting for him in a confidential capacity—therefore he must feel he can trust you, and I can do the same. I have long distrusted and disliked Robert Burton, and latterly, Kate has had the same feeling about him."

At this I started, and felt myself flush up.

"Yes," Mrs. Elmore continued, sadly, "it is so; and it has been the cause of great trouble to both of us. To-day, matters came to a climax. He insulted Kate in some way that she does not seem to care to tell to me—and Kate firmly and decisively told him she would have nothing more to do with him; and she broke off the engagement then and there."

Again I felt myself flush up, and my heart beat violently. What might this not mean for me in the chances it held out for me in the future! But it was no time to think of that, and I made no remark.

"So you see," Mrs. Elmore explained, "we are no longer friends with Robert Burton; and since poor General Fareborne is dead, and now poor Drummond too—it is all incredibly sudden and shocking—there is no one at the Hall I care to trust even with a message. That is why I desired Dr. Rumford to beg you to come across to me. I thought it very kind and thoughtful of you to send your card here to let me know you were in the neighbourhood. It seemed as much as to say, 'If you are in trouble, you have one friend close at hand that you can trust.'"

"Indeed, that's just what I did mean, dear Mrs. Elmore," I burst out impulsively; "only, well, I was afraid to say or write it, not knowing how it would be received."

She looked at me steadily for a moment, and then said, almost abruptly—

"Clement, why were you and your uncle bad friends?"

I told her I did not know, and, indeed, that it was just one of those things I wanted to know.

"I fancy Kate has some inkling of it," she went on reflectively. "You yourself never did anything to, to—well, to be ashamed of—to forfeit his confidence?"

"Never!" I declared "How is it you ask me that? Colonel Sterndale did the same!"

"We will talk of it another time," she presently answered, after another pause. "Meantime I want you to give some messages and a letter to Colonel Sterndale as soon as he comes down."

Then we had a quiet talk about old times; and I took my leave, promising to call in in the morning to give her any news I might have, and to inquire after Kate.

Outside the house, in the dark, I ran against a man; and found, to my surprise, that it was Mr. Clitchet.

"You here?" I exclaimed. "Why, I thought you would be in bed and asleep by now."

"I came over to inquire how the young lady is going on," he answered, quietly. "Now I am going back to the Hall. If you do not mind we can walk together, sir."

I had no sort of objection to offer, so we strolled back together, chatting as we went.

I WAS a little relieved the next morning to hear that nothing fresh had occurred during the night. I went early over to the village, and called at the inn for my letters; there was one from Colonel Sterndale saying that he would arrive that evening and put up at the inn. He was, he said, uncertain as to which train he could come down by, but would I come over to the inn about eight o'clock to see him. I wrote a brief note saying that I would be sure to keep the appointment, and I enclosed the letter from Mrs. Elmore, as I knew it would be safe enough lying there till he came. Then I went on to see that lady.

She told me that Miss Elmore was still going on well, but felt too weak and too much upset as yet to see any visitors; and after some further chat I returned to the Hall.

Here I found things going on in much the same way as they had been on the previous day; but, if possible, there was an air of even deeper gloom about the place and everyone in it. The news of the attack upon Miss Elmore had got about, of course; and it had not only caused a deep sensation in itself, but it had affected all the servants with what almost amounted to a panic. Each one, individually, went about with an unexpressed, but acutely felt, dread that he or she might be the next victim singled out for attack; and some, I learned, were openly talking of packing their boxes and leaving without notice.

I went over again in the afternoon to inquire after Miss Elmore, and finally, after a hasty dinner, started off in the evening, through a nasty, cold, drizzling rain, to keep the appointment with Colonel Sterndale.

I found him installed in the best sitting-room of the inn, with a bright fire blazing in the grate. He had just finished his evening meal, and was sitting smoking a cigar when I entered. Looking round the remains of the repast on the table, I ventured to ask him why he had not come over to dinner with me at the Hall.

"Because I prefer to stay here, boy, where I am free to come and go as I please, and where we can be quite private and talk freely," he returned. Then he added with a sort of grim smile, "And where one can sleep in safety in one's bed without fear of being murdered in one's sleep!"

"Ah, yes! You may well say that, sir," I answered. "Then you have heard what further things have happened?"

"I've heard two or three different versions—probably all wrong," he returned. "So now sit down and tell me everything. Begin at the beginning—that is, starting from your journey down. But first, will you have a cigar and a glass of port?"

To the last proposition I readily assented; and then, after first referring to Mrs. Elmore, and delivering the verbal messages she had entrusted to me, I gave him a full narrative of all that had occurred—just as I have set it down here.

He let me go straight through, and scarcely interrupted to ask even a passing question. At the end he drew a long breath and gave a low whistle, and then remained a long time silent, gazing thoughtfully at the fire. And I, having said all that I had to say, remained silent too.

Presently he looked up and spoke.

"It's a terrible business, boy—a terrible business—and a sad one all round. I am truly sorry about poor little Kate Elmore—and poor old Drummond, too. And you say they seem to have no clue yet to the perpetrator of all these outrages?"

"None as far as I can see or hear. And as for my own theories or ideas, I haven't any worth telling; they all seem to be hopelessly mixed up. I cannot see where the motive comes in. 'Surely it must be the work of a cunning madman,' I say at one moment; but a few minutes after, on thinking of certain other points, I have to confess that that theory does not explain everything by a long way."

"No," said the colonel, meditatively; "I've got a theory, however, that does fit the case; but whether ordinary people could be brought to believe in it is doubtful. If, however, I had acted upon it sooner, we might, perhaps, have saved poor Drummond's life—and Miss Elmore from the terrible experience she has gone through."

I stared at this. But I said nothing; and he went on:

"First, let me say I think you have done very well as far you could; and I am quite satisfied at having sent you. What exactly induced me to do so I will explain to you later on. But how to my theory as to the origin of all this business. Do you believe in certain things having a curse upon them?"

This rather started me. "I don't quite understand," I began, and hesitated.

"Well, you must know," he continued, "that I come of a Scotch family, and many of my countrymen believe firmly in 'second sight.' That my mother possessed it I can positively affirm, for by means of that faculty she two or three times warned me of coming dangers, and those warnings enabled me to escape grave perils. So far as to 'second sight,' which, however, has nothing to do with the matter in hand; I only refer to it to show you that I believe there may be strange things in this world that the 'ordinary person' wots not of—and would not credit if he came across them.

"Amongst those things that stand on the borderland of belief so to speak—believed in by some and rejected as idle myth and superstition by others—are the marvellous accounts the traveller in the East frequently hears of the doings and performances of the Indian fakirs. You have doubtless read and heard many such accounts, so I will not stop now to go into further details; I only assert that the observant traveller in those regions, who has eyes to see, and can mix with the people and gain their confidence, can see for himself at times marvels that the stay-at-home Englishmen would simply laugh to scorn. And we know, too—or I, at least, know—that some of our greatest explorers and travellers in Eastern climes, men whom science here has honoured and rewarded, and sober, experienced men of the world to boot, have found themselves compelled to admit a belief—not always, perhaps, openly expressed—in the actual existence of Eastern magic.

"One of many of the various forms in which these occult powers are displayed for good or evil—generally, I fear, it is the latter—is the power of laying a curse or spell upon certain places or things, so that all who come within the influence of those places or things are irresistibly swayed and guided, or urged on to certain acts, even against their own better judgment or inclinations.

"Articles bearing such curse or spell are supposed to be manufactured in the hidden secret chambers of the temples of some of the Hindoo gods—the goddess of Cruelty in particular—with many hideous ceremonies and accompaniments by unscrupulous priests deeply learned in the 'occult' sciences.

"Turning now to another notable institution of the East, you have, no doubt, heard of what is called 'Thuggee.' The Thugs—or 'Stranglers,' as they are sometimes termed—are the most hateful and detestable of all the various sects and castes to be found in India. Though they style themselves a religious fraternity, and have their own separate priests and temples, their whole end and aim in life—their religion, in fact—is murder—murder by strangulation. Their patron saint, so to speak—or goddess, rather—is Devī, or Kalī, the supposed wife of Sīva, the many-armed. The members of this execrable sect roam about the country in bands, frequently mounted on horses richly caparisoned, and attended by retinues of servants—all 'stranglers' like themselves. They ingratiate themselves with passing parties of travellers, and offer to travel with them for mutual protection, then, in some lonely place, they set treacherously upon their pretended friends, in their sleep, and murder every soul—not even the women or children being spared. They always kill their victims by strangulation; it being against their 'religion' to shed blood. Herein they differ from the bands of Dacoits, or ordinary robbers, with which India used to be, and Burma still is, extensively infested. But the Thugs are accounted worse than the Dacoits, on account of the relentless, barefaced treachery that is their almost invariable characteristic.

"Now it once became the duty of your uncle to hunt down, and bring to punishment, a notorious hand of Thugs who had committed innumerable atrocities on innocent travellers. He was successful in capturing them, and every member of the gang was condemned to death, just before their execution, their chief sent for your uncle, and, affecting to be grateful for one or two trifling ameliorations of the rigours of his imprisonment that your uncle had granted him, presented him, as a sort of keepsake, or legacy, with a very curious old ring, set with a cameo stone, whereon a representation of the goddess Devī had been cut with really marvellous skill. How he had contrived to secrete this trinket, when repeatedly searched, did not appear; however, there it was; and your uncle lightly took the ring, packed it up amongst a few other old curios and articles of virtu, and then forgot all about it. The Thug chief and his vile followers were executed in due course. I was there at the time; and I was devoutly thankful to see an end made of the hateful gang.

"Then your uncle left India, while I remained for some years longer. One day, now between two and three years ago, it chanced that I was able to save an old fakir from the jaw's of a tiger; or, rather, I saved him from immediate death, though he died later on from the wounds he received. He, too, professed to be 'grateful,' but he showed it in a different way—viz., by warning me against the ring which the 'grateful' Thug had presented to your uncle. It appeared that he (the fakir) had known the Thug chief, knew of the 'legacy' (as he termed it) of the ring, had been present at the execution, and remembered seeing me there with your uncle.

"'I have nothing to give thee, sahib.' he said, 'but one service perhaps I can render thee—if, that is, thou lovest thy friend, the one who captured Ab Salī, the great Thug chief. If so, I can, perhaps, as I have said, render thee a service. Say, sahib, dost thou love thy friend—wouldst thou serve him?'

"'Certainly, my friend,' I replied.

"Thereupon he proceeded to explain to me that the ring that the Thug had given to your uncle was the great sacred heirloom of the highest Thug chiefs, and had been handed down from father to son through countless generations.

"'To him who knows and observes the "omens,"' the fakir declared to me, 'the sacred ring gives strength, power, success, and protection in all his undertakings. But to him who knows not the "omens," or, knowing them, ignores them, the ring is a snare and a trap: a false friend that, at first, lures its temporary owner on, with seeming success and impunity, only to deliver him the more surely into the hands of his enemies. Be wise, oh, sahib! and warn thy friend, if thou lovest him, and if there be yet time; if the ring hath not already done its work, and accomplished on thy friend the long-delayed vengeance of Ab Salī, the great Thug chief, and shortly after that he died."

The colonel then remained silent a while, and gazed abstractedly at the fire. As for myself, I can scarcely describe the impression the strange narrative made upon me. I never had a grain of superstition in me; and, in ordinary circumstances, I should have laughed at so fantastic a tale. Yet here, under our very eyes, as it were, we had what looked like a wonderful fulfilment of the fakir's words spoken some years before; and of the sinister posthumous revenge planned years again before that by the treacherous Thug chief.

"What did you do about it; did you warn my uncle?" I presently asked of the colonel.

The colonel sighed. "Yes, I wrote to him, and told him all about it. But, of course, he laughed, and took no notice."

"And do you think, then, sir," I inquired, "that these murders are the work of one into whose hands this wonderful ring has accidentally fallen?"

"I do believe it, solemnly," Colonel Sterndale declared, "though I do not wish you to speak of it. I tell it to you in confidence, for your own—for our mutual—guidance. It may serve as a clue to the mystery; at least, it is as likely a one as anything the police seem to have been able to discover, seeing that they appear not to have found one at all."

"But what are the 'omens'?" I asked.

"Before a band of Thugs start upon an expedition," the colonel explained, "they consult the 'omens'—i.e., they, with their priests, go through certain ceremonies. If a jackal passes by, or an owl hoots, or a crow caws, and so on, the 'omen' is a good or bad one, according as it may come from the right or the left; from the east, west, north, or south. These 'omens' are marked and interpreted by the priests; and if they are declared to be bad, the proposed expedition is usually abandoned, or postponed for the time being. The old fakir declared that, in his last expedition, the Thug chief obstinately persisted in starting, in the face of adverse omens: hence his downfall and capture."

"I see; well, of course, we can scarcely expect that the person into whose hands this wonderful ring may have fallen, would understand these 'omens'; therefore, he is pretty sure to go against them before long, and so betray himself. Is that how you read it, colonel?"

"It is."

"One other thing strikes me," I continued. "The fakir, you said, spoke of the ring conferring 'strength.' Does that mean actual, physical strength, do you suppose?"

"So I should understand it."

"Then," I said, almost with a gasp—for the strange idea nearly took my breath away—"that may explain what has puzzled me. Dr. Rumford spoke of the 'enormous strength' that must have been exerted by the man who murdered my uncle. Yet, I myself noticed that, according to the marks I saw, the murderer's hand seemed to have been a small one. And, meantime, the police are looking out for a great powerful ruffian with a big, brawny, muscular hand! Do you see how what you have told me—strange as it may be—seems to explain much that has been inexplicable hitherto?"

"I do; and I believe that we are on the right track, boy."

"Yes! But still, who could the murderer be?"

When I left the colonel, I again ran, just against the inn door, against Mr. Clitchet. According to his account, it was quite accidental; he only "happened to be just going over to the Hall. If I did not mind he would walk with me."

Well, of course, I again had no objection; only, as it was the fifth or sixth time I had "accidentally" run against him in the last day or two, and always in the most unlikely places, it seemed somewhat strange. Was he watching me, I wondered. And then another thought flashed across me—Could he suspect I had any hand in this devil's business?

At the mere suggestion, I grew hot with anger, and felt so indignant that I "sulked" all the way, and scarcely spoke to him or answered any of his remarks the whole distance to the Hall. For this treatment of the astute detective, however, I very soon saw good reason to be sorry.

I WENT to bed that night with a strange medley of thoughts and emotions agitating my mind. For the first time for many a long day "hope" entered once more into my view of the future; hope of something that would have appeared, but a day or two before, to be only a wild dream, a tantalising illusion. But, now—was not Kate Elmore free? Had she not cast Robert Burton off and refused to see him more, notwithstanding the position he would soon be able to offer her? And had not her mother spoken kind words of hope and encouragement to me that seemed intended to impress upon me that I was not to despair of—of—ah! of what? I scarcely dared to put into shape in my own thoughts even the meaning that might be attached to her words; and, still more, to her manner. The truth was that I had so long resolutely repressed all thoughts—certainly all hopes—of this character, and disciplined myself, as it were, into so listless a state of feeling, that hope itself had seemed dead, or sleeping, and it must take time to rouse it into warm life again.

Then I wondered why Mrs. Elmore had asked me the same odd questions that Colonel Sterndale had already put to me—questions about what I had done, or was supposed to have done, to displease my uncle, or to have caused him to cast me off.

Certainly, he had never assigned any reason as far as I knew. But, then, I had no claim on him; no ground for disputing his right to do what he pleased with his own. He had taken me from school when my parents died, and had brought me up; then he had suddenly appeared to alter his mind, and he sent me adrift. It was cruel, especially in view of the expectations his previous kindness had raised—but, as I have said, he had the right to do as he pleased. He had made no promises, and, therefore, was breaking none in acting as he did. Thus I looked at it; and I was constrained to admit to myself that this behaviour, if fitful and changeable, did not leave me any very clear ground of complaint.

Then I went over in my thoughts the strange statement made by Colonel Sterndale concerning the Thug's ring, and its supposed supernatural attributes. What he had said suggested many wild, weird fantastic ideas; and they came crowding into my brain in a whirl, until, at last, they took forms that literally filled me with a kind of cold dread. I wondered if it could possibly be true that someone had become possessed of the sinister ring, and had, as a result, fallen under its malign influence—had become possessed with homicidal mania? And at this, as I pictured to myself the murderer prowling about the house in a state of supernatural frenzy and ferocity, cunning, cruel, pitiless, as must have been the being who had so mercilessly done to death two old men and assailed the life of a young and beautiful girl—at this fancy I grew positively horrified. I then suddenly remembered, with serious concern, that there was no fastening to my bedroom door—and that, in consequence, I had not been able to either lock or bolt it. I had remarked this the first night I slept in the room; and had wondered greatly that, well-appointed as I knew the house to be, as a whole, this particular room should have been left without fastenings. But since I was not in the habit of locking my bedroom door of a night, even when I had a key, the circumstance had not troubled me at the time, or, till now, occasioned me a moment's thought. Now however, I devoutly wished I had requested one of the servants to find me a key. But, at last, thinking thus, first of one thing and then of another, I fell into a restless, troubled sleep.