RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Henri Rousseau (1844-1910)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Henri Rousseau (1844-1910)

The English Illustrated Magazine, 1899

with "The Spell of the Bird"

The English Illustrated Magazine, 1899

with "The Spell of the Bird"

"FASCINATION? Does anyone believe in fascination? Yes, I do, and I don't mind who hears me say it or who laughs at it. If you had had the experience I once went through, you would believe in it too!"

The speaker was one of a group at the Kaieteur Hotel, Georgetown, British Guiana. He was a tall, powerful-looking man, with a shrewd, intellectual face and a grave, reserved manner. He had been sitting silent and almost unnoticed in a corner while a long and, at times, animated discussion had been going on around him concerning forest life in the interior of our South American colony. His name was Creldon—George Creldon—and he was, as I afterwards heard, one of the best known and most respected of the planters in Demerara. He was looked upon, too, as an authority upon wild sports and forest travel, having formerly spent much of his time in hunting or prospecting trips in the interior.

To those who know Georgetown, it will be unnecessary to say that we were all indulging in the drink par excellence of the country, commonly called a "swizzle."

When the first feelings of surprise caused by Creldon's unexpected declaration had passed away, and the pronounced comments to which it gave rise had quieted down, we soon found ourselves ordering a further "swizzle" each as a fit and becoming preparation to listening to his story. It was as follows—

"When certain persons," Creldon began, looking round at some of us with a severe air of correction, "declare so confidently that this or that 'cannot' be true, they would do well to remember that our knowledge of the great forests of Guiana and Brazil is in reality very limited indeed. There are vast tracts which are absolutely unexplored; have never, so far as we know, been traversed by either Indians or white men. And since the more shy of the animal creation ever shun or forsake those parts where man is to be met with, however seldom, therefore it is fair to assume that we do not yet know all the creatures that may exist in those impenetrable recesses.

"Mr. W. H. Hudson, a naturalist, who has lived for many years in South America, has lately in his book, 'The Naturalist in La Plata,' startled and indeed astonished the zoological world by making known many strange things that were before altogether unknown and unsuspected. He declares, among other matters, that he has just once seen, and then lost, creatures entirely new to naturalists; and this alone should teach us that the Indians may not always be wrong in their beliefs, or in the tales they tell of strange and wonderful animals or reptiles that still lurk in the forest depths. I am not, of course, maintaining that all their wild tales and fantastic beliefs are true; I only suggest that here and there, there may be a better foundation for them than many, perhaps, would think. I have myself seen strange creatures that are entirely unknown to zoologists, but they got away before I could shoot or catch them. What, however, I am about to relate is by far the strangest, the most extraordinary adventure that ever occurred to me. I can only tell it as it happened; and I do not suggest any explanation beyond reminding you that there are in nature already many known instances of creatures—the very ones most likely, one would think, to keep apart—combining or working together for mutual profit or protection. There are the birds that hop in and out of the open mouths of the crocodiles and pick their teeth and jaws clean for them, the great reptiles never taking advantage of the trustfulness of their feathered friends. Then there are the 'pilot-fish' that accompany the shark; and in Guiana we have several very curious, almost incredible, examples. Thus we know that, as a rule, birds feed freely on ants and wasps among other insects; yet in Guiana are frequently to be found settlements or colonies in which mocking-birds, ants, and wasps and wild bees are banded together for mutual protection. The birds leave the insects alone, and, in return, the latter protect the nests of the birds during their absence; and woe betide any unlucky tiger-cat or monkey that ventures near the nests after the young ones or the eggs. The wasps and bees will attack it as ferociously as if it had tried to rob their own nests; and the ants will attack snakes in the same way. Even plants and ants form protective alliances, as in the case of some of the 'vetches,' which encourage ants of one kind to live on them in order that they may fight off the 'leaf-cutting' ants, which destroy so many other plants and trees in the forests of South America. These are facts that have been noted and vouched for by such well-known authorities as Sir Robert Schomburgk, Mr. Bates, Mr. Barrington Brown, Mr. W. H. Hudson and others.

"Now, amongst the Indians, in some places, is a deep-seated belief in the existence of a monstrous serpent of unusually terrifying aspect but of a sluggish nature, which is always accompanied by one or a pair of birds equally rare but of strikingly beautiful plumage. This serpent is called in some parts 'Kragi,' in others 'Krao'; and in others, again, there is no particular name for it, and it is ranked as a kind of 'Camoodi,' which is the Indian term for the great boa-constrictor of Guiana. The bird is called the Kalon, or sometimes the Krao-Kalon, and is declared to entice victims into the neighbourhood of the serpent, so that the latter may seize them with very little trouble or exertion; the bird being afterwards rewarded by being allowed to pick out the strangled creature's eyes and other tit-bits before the dead body is swallowed by the reptile.

"So much by way of preliminary explanation. Now to my story—

"While at Rio one time—it was in my 'restless' days, when I wandered about pretty well all over South America—I became acquainted with a young fellow to whom I took a great fancy; we quickly, in fact, became firm friends. He was an Englishman named Geoffrey Bingham, a fine, handsome, courageous chap as you need wish to meet with. He had hunted big game in Africa and India, and knew his way about a bit, I can tell you, for all he was not then twenty-five years of age. He had well-to-do parents in England, who allowed him enough to either live at home comfortably or wander about as pleased his fancy. He told me he was going up-country to join a man he knew who had discovered an ancient gold-mine, from which he was taking out a fair amount of dust, though he was only working it in a quiet way with a few friendly Indians; and after some talk and some persuasion on his part I agreed to accompany him. There were no grand expectations of great wealth held out as likely to be our reward; nor, on the other hand, was any premium asked for the privilege of joining in.

"'It's just this way,' Bingham said. 'Old Soltram—that's the old boy who found the mine—doesn't want the thing talked about, and a lot of tag-rag and bobtail brought about his ears; at the same time it's pretty lonely out there, and he is not at all averse to one or two fellows of the right sort coming to help on the give-and-take principle. That is, if you work for the dust yourself, you must pay your own Indians and hand over to Soltram a percentage on what you find; or, if you don't care to bother about that sort of work, you can go out hunting for us and keep the larder supplied, and we will pay you a percentage on what we get.'

"He further told me that Soltram hadn't much faith in the mine proving a good one for long. He believed it had been about worked out when he found it, and that he had only pitched by chance on a drift that had been missed by the ancient workers; and this might come to an end at any moment. So I agreed to go, rather for the mere sake of the hunting and adventure than with any idea of making money.

"When all our arrangements were completed we started in canoes up the river routes, then across pampas and forest till we got into the corner, as it were, where Venezuela, Brazil, and British Guiana all meet. And we came to a halt in that wild and little-known region of mountain and primaeval forest which forms part of the borderland that has been in dispute for a hundred years past between Great Britain and Venezuela. A terribly wild district it is, full, however, of savage grandeur, being situated only a few degrees from the equator, where nature is to be seen both at her best and her worst. Here are to be found the highest waterfalls, and, in some respects, the most wonderful mountains and table-lands in the world, and all sorts of climates, from that of the temperate zone on the table-lands to the seething swamps of equatorial South America in the valleys. And here, too, is to be seen the most wonderful vegetation of the whole continent: some tracts being absolutely carpeted with begonias, orchids, gloxinias, and other plants and flowers so rare and—in England—so costly, that to secure them would be enough to turn the head—and make the fortune—of any collector who should be the first to come among them.

"Here, in this strange, little-known region, we found Soltram established, with his primitive gold-extracting plant, his Indians, his dogs, and—his daughter! Yes, extraordinary as it seemed, he had actually a daughter living with him, and a very charming young girl I found her too. At first I thought that this must have been the real attraction that had brought Bingham so far afield; but I soon found it was not so. He and Ledra Soltram, as presently became apparent, were good friends, and nothing more. Indeed, he made a confidant of me about this time, and confessed that he had a sweetheart awaiting him in England, to whom he intended to return when this adventure—which was to be the last of his wanderings—came to an end.

"Thus the field was left entirely open for me, and I fell over head and ears in love before I had been there a week. Nor was I without encouragement from the young lady herself, and ere long I began to bless my luck that had thus led me to her side. At first I elected to do the hunting and keep the larder supplied, since this gave me many opportunities of being alone with Ledra, while the others were away at the mine.

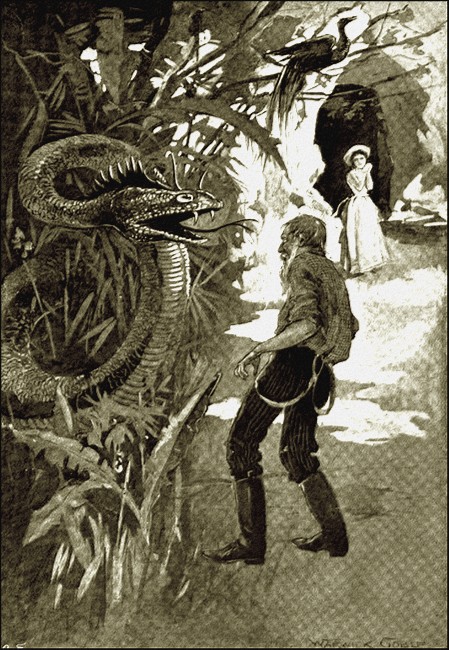

At first I elected to do the hunting and keep the larder supplied,

since this gave me many opportunities of being alone with Ledra.

Soltram had built a very substantial log hut about a quarter of a mile from his mine, in a clearing at the edge of a thick, almost impenetrable belt of forest. Round about was quite a small settlement, his Indians having erected huts for themselves and begun to cultivate patches of open ground. From the huts a pathway had been cut through the dense wood to the base of a cliff, where was a cavern with a small stream of water flowing out of it, and this was the mouth of the old mine. Inside were many galleries running this way and that, some, one above the other, with steps or wooden ladders to connect them. Soltram himself was a rather fine-looking old boy with white hair and beard, not a bad sort, but, as I soon discovered, of a greedy, avaricious disposition. Notwithstanding his name, I judged him to be of Scotch descent, and this I afterwards found to be a correct guess. Who he was and how he came to be there does not matter here: it would make my story too long were I to go into all such details. Suffice it that he had somehow found his way there, dragging his daughter about with him, and had happened on an old mine, from which he was now getting out a few pounds' worth of gold a week clear of expenses. But the yield was not so good as it had been, and it seemed quite on the cards that at any moment it might come to a dead stop.

"At first, I say, I elected to do the hunting and fresh-meat-providing for the establishment; but after a time the gold-seeking fever seized upon me as well as the others. Honestly, I do not think this would have been the case if I had not been so madly in love with Ledra. I saw enough, however, of Soltram's temperament to understand that he had high ideas concerning his daughter—especially if he himself should become rich—and to feel certain he would never, in such a case, give his consent to her marrying one so moderately well off as myself. Hence, if I wished to find favour in his eyes, it behoved me to hie me each day to the mine, there to work hard for my share of whatever was going. Then, if the venture should turn out well, and Soltram become wealthy, I also might be not far behind. Besides, there was always the chance that I might, individually, stumble upon some very rich find that might cause Soltram to regard me as a desirable son-in-law straight away. So I came to an arrangement, engaged a gang of Indians on my own account, and set to work, other Indians being told off to form daily hunting parties to supply the necessary fresh meat. Only once or so a week, Bingham and I would accompany these hunting parties, partly for a change, and partly to keep our hands in. Thus some months passed, during which we got a good deal of gold from the old mine, and I had grown quite used to the life. I had, indeed, every reason to be well satisfied, for I was making money and making love at the same time. Then, however, came a sudden and tragical end to our enterprise.

"One day, about noon, we—i.e., Soltram, Bingham, and myself—had come to the mouth of the mine from the distant workings to have our midday meal, as was our custom. This was brought for us from the huts by Indians, and Ledra would often come with them and chat with us while we ate, going back with the Indians—who on such occasions were chiefly women, girls, and boys—so soon as we had finished and returned to our work. On this particular morning, when we got out in the open air, we found Ledra there, but not her attendants. She had, in fact, run on in front and outstripped them. For this she was reproved by her father; but while he was scolding her she uttered an exclamation and darted from his side. A clearing of considerable extent had been made round the mouth of the mine, and this was littered about with heaps of debris, logs of timber, and so on. I then saw that Ledra was chasing a bird of wonderfully beautiful plumage. It was, in some respects, like the Bird of Paradise, but in brilliancy of colouring it surpassed any bird I had ever seen. It seemed quite tame, and frequently almost allowed its pursuer to come up to it; when, however, with a coquettish little flutter, it would evade capture with remarkable agility, and affect to hide among the logs or behind some heap of rubbish.

"Thinking that Ledra would like me to shoot it in order to secure the skin if she were unable to catch the bird, I turned back into the mine for my gun. I had left a double-barrelled piece loaded with shot in one barrel and ball in the other in the first gallery over the entrance. The end of this gallery was open, but fenced round with a sort of barred bay window on the outside, and shut off by a partition and door on the inside, forming an apartment where we could lock up our spare tools and other stores. The object of barring the window was, of course, that no one should be able to get in by climbing up the rock when the gates which protected the main entrance were closed and padlocked.

"Just as I had taken up the gun I heard an outcry, and paused for a moment to look out through the bars to see what was going on below. The Indians had arrived with our meal, but had evidently taken alarm at something and were fleeing in terror, each one having incontinently thrown down whatever he or she was carrying. Much surprised, I looked anxiously for Ledra, and saw that she was standing still in the middle of the open space, while her father had gone after the bird, which had now perched itself on one of the lower boughs of a tree at the edge of the clearing. Meantime, the Indians had every one disappeared, with shouts which I could not then distinguish, but which I afterwards knew to be 'Krao-Kalon' and 'Kragi.' Suddenly the bird began to sing, and it had the most charming, thrilling note I ever heard in my life. Indeed, it was not like the song of a bird at all; it resembled nothing so much as the music given out by an Ĉolian harp when the wind sweeps across its strings. The effect was inexpressibly sweet; yet mingled with it was a weird, wild note that somehow repelled while it charmed. And as the notes swelled out fuller and louder, I could not but stand still and listen in a very ecstasy of pleasure and delight; which, however, began soon to change to a cold horror, as I realised, all at once, that I could not move!"

Here the narrator paused, and passed his hand across his eyes as though to shut out some horrible sight. His manner was so earliest that it visibly impressed us all; and no one spoke. After a brief space he resumed—

"I cannot describe to you the astonishment, the alarm, with which I realised what I have just told you—namely, that I was unable to move. I was overrun by a mixture of feelings in which surprise, perplexity, horror, incredulity, and wonder were all jumbled up together. Yet were my senses almost abnormally acute; I remember, as I looked helplessly out, how I saw the brilliant sunshine pouring down and lighting up portions of the scene, in glaring contrast to the deep, gloomy shadows that lay among the trees of the forest beyond. I remember Soltram, as he stood with his back to me, just under the bough on which the bird had perched. So near was he to the creature that, with a long stick, he could have knocked it over. Yet he stood still and never moved even his head. I saw Ledra out in the sunlight, her broad hat swaying slightly, her hands clasped together, standing like one turned to stone; and just below me I saw Bingham, who had stepped out and then stopped; and he, too, was as motionless as the others.

"And still that infernal bird sang on, flapping his wings, his silver-and-gold plumage sparkling and flashing in the sun. And slowly there rose up in my mind a presentiment, a foreboding of some horror yet to come, and I watched and waited for—I knew not what.

"All the time there was in my mind a feeling as of resentment against these other three that they stood thus and did nothing. Why did not Bingham or Soltram move, or do or say something? I wondered to myself, thinking that I was the only one who felt the spell, and vaguely angry that these others did not move or offer to come to my assistance. I tell you it is an awful thing to have all your physical faculties numbed like that, and yet to be able to see and hear all that goes on before you!"

Again the speaker paused and wetted his lips from the glass before him. No one spoke, and he resumed—

"I know it must sound strange—incredible—to you who have never passed through such an experience, yet to me, at the time, it was actual enough. Even now I cannot bear to recall what I went through, but, having begun it, I must go on with it, I suppose.

"The bird sang on, and the unnatural quiet that seemed to have fallen upon all the world beside continued until I heard a slight rustling. It came from near Soltram, and looking across, I saw, slowly rising through the bushes, the most hideous head it has ever been my lot to look upon. That it belonged to some member of the serpent tribe was soon evident; but in grisly repulsiveness it exceeded even what a magnified rattlesnake might be supposed to be like; and there are not many things in the world more horrible, I imagine, than the expression, if one may so term it, that lurks in the head and jaws of a rattlesnake. The creature that now slowly came into view, however, exceeded in gruesome hideousness anything that I ever imagined. Like the rattlesnake, its mouth seemed to be formed in the likeness of a set sneer of the most sinister malignancy; but the eyes were much larger in proportion and had a baleful glare in their yellowish-green depths that sent cold shivers through you as you met and endured their fixed, cold gaze. A hood, somewhat after the shape of that of the cobra, two horns, and a kind of crest on the neck at the back of the head completed the terrible picture. And still, while it rose slowly, menacingly beside him, Soltram, who seemed to be looking straight at it, never moved; and still that bird-fiend sang on and flapped its wings, and appeared to be revelling in the very height of enjoyment."

Again the speaker paused, but still there was silence in the group around him, and he once more resumed—

"Slowly, and with a sickening deliberation, which told only too clearly how absolutely certain he felt of his prey, that terrible beast drew nearer and nearer to Soltram, swaying slightly to and fro, and protruding its forked tongue, which darted in and out of its now open jaws. I remember wondering vaguely why Soltram did not run away, not comprehending that he was in the same condition as myself. At last the monster gave a quick leap, and fixed its fangs in the throat of its victim, and immediately coil after coil wound round Soltram's body, till I could hear, even where I was, the fearful sound of cracking bones. . . .

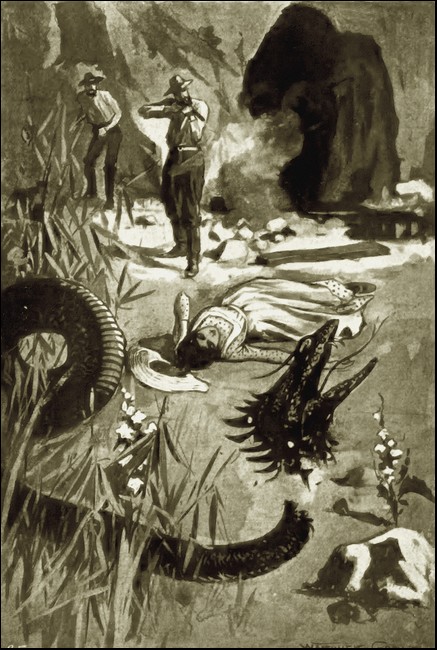

The terrible beast drew nearer and nearer

to Soltram, swaying slightly to and fro.

"Presently the creature slowly relaxed its folds, and, after lying inert for a short space, fixed its leering eyes upon Ledra, and began to creep towards her. I madly strove to burst the bonds that seemed to hold me as if in a vice, but still I could neither move nor cry out. The sweat poured off my face; I am sure my eyes must have appeared, could anyone have seen them, to be bursting out of my head with horror. Yet still I could not move, could not even cry out; still Bingham was motionless, too; and still the bird sang on, and still the monster—which I could now see was a serpent of gigantic size, with a frightful, scaly shape—crept slowly nearer, ever nearer, towards the one I loved beyond all else in the world.

"Then poor Ledra gave one long, agonised shriek, and fell fainting on the ground; and at that the fiendish bird stopped singing. Whether the cry startled it, or whether it thought it now time to claim its own perquisites, I cannot say. But it flew down, and going up to the dead man—who was lying on his back—hopped on to his face. But the awful spell was broken; the blood was again rushing through my veins, and I felt myself nerved with a savage, desperate revenge. I raised the piece I held in my hand, cocked it, and aiming carefully, sent a bullet crashing through the head of the great snake, which at once began to writhe and twist about in horrid contortions. Then I turned the barrel loaded with shot on the bird—or, rather, tried to; but the hateful creature had already disappeared, frightened, I suppose, by the sound of the shot; and, in fact, I never saw it again. I then rushed down and out into the clearing, and there with the undischarged barrel blew the head off the still struggling monster; and Bingham now coming to my assistance, we carried the unconscious girl inside, and we laved her face with water from the cool stream that ran through the cavern."

I blew the head off the still struggling monster.

"I won't tell you of the anxious time we had of it with the stricken daughter; but she was well nursed and tended by the Indian women, and slowly came back to the world and to health if not to good spirits. Then she begged so piteously to be taken away from the place that had for her such unendurable associations that I gave up all thought of anything except how best and quickest to get her down to the coast. And as Bingham did not care to stay by himself, we gave up the mine to the Indians and soon started off together to get back through Venezuela. Eventually we arrived without mishap at Georgetown, where I placed my charge for awhile in the care of my mother. A few months later we were married and settled down on my fathers estate here, where we have lived ever since. But though it is now many years since it happened, neither I nor my wife will ever forget the 'bad quarter of an hour' we passed through while looking on at the grim tragedy enacted before our eyes, chained down as we were and rendered physically helpless by that diabolical bird and the weird spell of its strange song."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.