RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

The English Illustrated Magazine, 1907

with "The Mystery at Milton-on-the-Moor"

A WILD winter night on a bleak Northumbrian moor. The hard, frozen road is here and there covered with the snow that has been falling thick and fast for the past hour. But in other places it is kept clear by the wind, which sweeps over it in swirling gusts, rushing on across the moor as though in frantic haste to reach the mountains that lie beyond. There, upon the steep hillsides, and in the rocky ravines, are woods in which—as it seems to know—it can have fine sport: howling and whistling between the trunks, tossing and beating the leafless branches to and fro, and hurling against the defenceless trees the accumulated snow that it is driving before it across the fells.

At one place the roadway widens out as it passes a little hamlet, where, amongst a few small cottages, stands a roadside inn. From its windows and doorway a cheerful radiance falls upon the road, lighting it up on one side, and meeting near the centre a ruddy glow that proceeds from a blacksmith's forge upon the other. This glow and the regular rhythm of beating hammers tell that the busy smith has not yet finished the labours of the day; but no children are to be seen to-night around his door, nor is there sign of customer or wayfarer. The road on either side of the lighted space fades away into shadow so suddenly that even the patches of white snow that lie but a few yards away can scarcely be discerned in the darkness.

As to the inn, it is called the "Halfway Tavern"; but where it is half-way to or from no one knows. This is, indeed, one of the standing jests of the countryside, and forms a perennial source of harmless amusement to the travellers who make it their house of call. It certainly is not half-way between the nearest town—Milton-on-the-Moor—and the railway station; for the latter is but a quarter of a mile distant, while the former lies nearly five miles away. Nor are there any other places between which it could be supposed to stand half-way—at least, within a reasonable distance—though some imaginative persons have been known who calculated that in the old posting days it was just half-way from London to some town or other in Scotland. But this is only one amongst dozens of more or less far-fetched explanations that are constantly being hazarded by the clever thinkers of the district; and for the sake of these good folks it may be charitably hoped that the mystery, such as it is, will never be cleared up, for they would then lose their never-failing and very innocent incentive to mild jokes whenever they visited the hostelry. Indeed, such a thing would probably have disastrous effects upon the fortunes of the establishment—and these are none too flourishing as it is—since many might then pass it by who are now tempted to enter it on their way to and from the station, on purpose to fire off the very latest observation upon the subject that has occurred to them.

At the railway station—where a board, with the legend "Milton-on-the-Moor," deludes many a stranger who alights there into the mistaken idea that the town is not far away—there is only the station-master's cottage and a few coal and goods sheds. The station-master's assistant—the one who acts as porter when he is not following his trade of boot and shoe mender, or working in his garden—lives at one of the cottages near the inn. A few other cottages and a farm-house make up, with the smithy, the whole of the hamlet, and no other dwellings, save the station-master's habitation, are to be met with for miles in any direction.

Such is the scene—or, to turn from the present tense to the past—such was the scene on the night on which this story begins: a bitter night in December, when there had suddenly come on what was the first really severe snowstorm of the season. It was but seven o'clock, and the smith, as has been stated, was still at the forge, though probably he had little expectation of seeing any fresh customers that evening.

Yet, just as the sound of the hammers and of the blowing and roaring of the fire had ceased, and he and his apprentice were preparing to close the place for the night, there came along the road the sound of a fast-trotting horse. It was only audible at intervals; being muffled here and there where the snow lay; but still, every now and again—and each time more distinctly—the hoof-beats rang out, and plainly there could be heard amongst them the "click-clack" of a loose shoe.

Timms, the smith, pricked up his ears.

"Something yet for us to do to-night, I think, lad," he said to his apprentice. "Better blow up t'fire." And as the other obeyed, Timms looked out in the direction from which the sound had come; and now he could see two lamps on a dog-cart throwing out beams of light on all sides, and growing every moment brighter as the vehicle rapidly approached.

"Why," said Timms, "it be Dr. Venner! I wish it wer' a'most any other body, for that mare of his is a ticklish beast at the forge—'specially when she's in a tearin' hurry t'get whoam; an' she's sure t'be that to-night."

The dog-cart drew up at the blacksmith's door, and the groom, clad in a great-coat which was white with snow, got down and went to hold the mare's head.

The one who had been driving, and whose waterproof cape was also thickly covered with white flakes, called out in a cheery tone—

"Timms, can you fasten a shoe for me?"

"Ay, ay, doctor. I'll see to it."

"Good," said the other, getting down. "I'll go into the house while you do it."

In the passage leading from the door of the inn to the bar, the doctor met the landlady, who had heard the dog-cart drive up, and was coming out to see who the travellers were.

"Good evening, Mrs. Brown—if one may use that expression on a night like this."

"Why, it be Dr. Venner! Good evening, sir. Well, this be queer, for we was only jes' now a-talkin' about you!"

"Indeed! How was that?"

"Why, sir, a strange gentleman has bin 'ere a-askin' for you—not half-an-hour agone. But come in, sir, come in. There be a good fire inside. Stephen, here be Dr. Venner. Move out o' that chair."

"No, no," said the new-comer, as he entered the bar-parlour, where a great fire was blazing; "keep your seat, Mr. Brown. I shall sit over here. I shan't come near the fire."

Stephen Brown, the individual sitting in an arm-chair before the fire, with a long clay pipe in his hand, rose up and offered his seat to the visitor; but finding he would not take it, sat down again. He was a thin, elderly man, with grizzled hair and whiskers, sallow complexion, and a stolid, taciturn manner. His wife, on the other hand, was usually spoken of as "buxom"—whatever that may actually mean. She was a plump, rosy-faced, bustling little woman, who always had plenty to say.

"I'll have some of your mulled elderberry wine, Mrs. Brown; and put half a teaspoonful of powdered ginger into it. Don't spare the ginger. That's the thing to warm you on a night like this."

The landlady went out of the bar, and the doctor, throwing open his Inverness cape, seated himself at the table on the opposite side from the fireplace. He pulled out a cigar-case, and, in leisurely fashion, proceeded to light a cigar.

Dr. Venner was a man of not more than thirty-two or thirty-three. His hair and eyes were dark, his face clean-shaven, with a mouth that denoted firmness, and a forehead indicative of a high intellect. The features were clear-cut and handsome, and his expression prepossessing. But the pale complexion and grave, contemplative eyes, gave the impression that he was of a quiet, studious turn of mind—the characteristics one usually looks for in the laboratory student, rather than in the conventional country doctor. And such was indeed the fact. He had enough to live on, and was able, therefore, to pursue his favourite ideas and theories in the way of chemical research without troubling himself to work up a practice.

"Well," he presently said, addressing the landlord, who had resumed his occupation of smoking and staring into the fire, "and how are things going with you? Has the place got any nearer being 'half-way' to anywhere in particular yet?"

Everybody who visited the inn made some remark of this kind. No one was ever known to omit it. It seemed to be regarded as a point of honour, so even Dr. Venner fell in with the general custom.

Stephen Brown gave a grunt.

"Aye," he said, "it be gettin' half-way to bankruptcy—that's where it be gettin' to, I'm afeard."

"Well, well; so long as it doesn't go further—stops half-way, you know—that won't be so bad. But I'm thinking we shall all feel as if we'd been through the Bankruptcy Court to-morrow."

"How be that, doctor?"

"Why, I think, when we get up in the morning, we shall find the whole country round has started with a clean sheet."

Old Brown chuckled at the pleasantry—he always chuckled at his customers' jokes, as in duty bound, however mild or weak they might be. Perhaps he understood the mild ones better, and therefore appreciated them more.

Mrs. Brown came in, busying herself amongst the bottles in the bar.

"I didn't know you was out this way to-day, sir. Been over to Felton Towers to see Sir Martin Brenwell, I suppose, sir?" she said.

"Yes, Mrs. Brown; you've guessed it. Been to see my patient there—my one only patient, I may almost say."

"And how be he goin' on, sir?"

"Oh, very well; so well that I shall not need to go again unless he sends for me. And so there is an end, for the present, of 'my only patient,'" the doctor replied, laughingly.

"Ah, well, doctor, you know that be your own fault. You could have plenty of patients if you liked. But you prefers to shut yourself up in that place of yourn, and work at scientific things like."

"It is a fine thing to be a larned scientific man," put in old Brown, with conviction. "Better'n bein' a poor country doctor, after all."

"Yes," said Mrs. Brown, "if you don't go and blow yourself up over it, as your grandfather did, sir."

"Well, he wasn't much hurt, Mrs. Brown. And, after all, a little blowing up isn't such a great matter. You can get used to it. I know some men who are 'blown up' at least two or three times a week—eh, Mr. Brown?"

Old Brown turned his glance towards the doctor and gave a sly wink.

Mrs. Brown saw it, as well as the twinkle in the doctor's eyes, and bridled up at once. She knew the remark was a reference to the "curtain lectures" to which, now and again, she was known to treat her husband.

"Well," she answered, with asperity, "if people gets scolded a bit at times there's some as deserves it. Wait till you're married yourself, sir, which won't be long first, from all I hear."

It was a matter of common knowledge in the district that Dr. Venner was supposed to be engaged to be married to the beautiful Lilian Darefield, the heiress of Ferndale Hall; and the doctor knew at once, therefore, what she alluded to. But his reply was of the non-committal order.

"I hope to be very good, and not deserve it, Mrs. Brown," he said meekly.

"We shall see," returned Mrs. Brown darkly. "But, anyway, my man there, he do deserve it. The way he—"

The doctor saw a scene impending, so, to draw the talk off from domestic rocks and shoals into a quieter channel, he interrupted the hostess—

"By the way, what about this stranger? You have not told me who he was."

Mrs. Brown went off at once to this fresh topic.

"Yes, beggin' your pardon, sir, of course. I forgot. Well, he was a very old gentleman, sir."

"Very old?" said the doctor.

"Oh, yes. As old—as—as—" Mrs. Brown hesitated for a simile.

"As the Wandering Jew," put in the host.

"Ah, yes, sir! It's true what Stephen said. The old gentleman looked just like pictures of him I used to see in an old book at home. And they do say, sir, as a visit from that party brings terrible bad luck wi' it."

"This is very interesting," returned Venner with a smile. "And what did he say, this wonderful stranger?"

"He asked about your grandfather, Dr. Malcolm Venner; then, when we said he was dead, he inquired about your father; and at last, when he found he was dead, too, he said he must see you. But he didn't seem to know you—had never so much as heard your name, sir."

"Has he gone into Milton?"

"Yes, he be gone on foot. Our fly was wanted by the station-master for somebody what telegraphed to him for it. So this strange gentleman, he wouldn't wait till it come back, but said he must go on, as he wanted to see you at once. It was very pressin', he said. But, indeed, he looked scarce able to do the walk. He seemed uncommon weak and feeble-like. He nearly fainted when he come in, and we had to give him some brandy."

"He seemed to have plenty of money, though," Brown remarked, "and he's left some behind him."

"Yes, sir; he took out a purse, and there was a lot of gold pieces in it, an' one big one fell out, and it rolled down into yon crack in the boards. He said it was a furrin coin, an' was worth three or four pounds in English money. My man was goin' to get the board up for to find it, but he said he wouldn't wait, but he'd call fur it when he come back this way. So my man's goin' to get the board up in t'morning to look for it."

"H'm! He would have done better to have stayed here, as it happened, wouldn't he?" the doctor observed.

"Yes, sir; but then we didn't know as you was over this way, you see."

"No; and I should not have been here now but for a loose shoe; else I should have returned by the other road. I went that way this morning. My man has been on the drink again, and neglected to take the mare to have the shoe fastened, though he acknowledges now that he knew it was getting a bit loose. I am going to discharge him; I really mean it this time. This is the fourth time he has broken out in the last month. I forgave him before, but I can't put up with it any longer. He doesn't look after the mare properly when he gets like that, and he'll ruin her if I don't start him. She might have been lamed to-night if there had been no blacksmith on the road."

"Ah! And she be a beauty, too! Everybody says that."

Just then Timms came in to say the mare was ready to start.

"I had to put a new shoe on, doctor," he said. "Old one wur broke. She'd a-bin lamed if ye'd taken her much furder."

Dr. Venner uttered an exclamation of anger.

"That's just what I was saying, Timms," he answered. "I'll give him the sack over this!"

He paid the smith, adding a shilling besides to drink his health with, settled with the landlady, and went out with a cheery "good-night."

Timms followed him to the door, and went to hold the mare's head, while the doctor and his man seated themselves and arranged the rugs. He had much to do to hold on to her, for she was fretting at the delay. When the doctor called out, "All right," and he let her go, the animal seemed to gather herself up for a leap, as might a hare; then she shot away through the falling snow with a spring that jerked the riders in the dog-cart back in their seats and that put a heavy strain upon every strap and buckle of the harness.

"Humph!" Timms muttered, as he stood gazing after the retreating vehicle; "Lucky t'doctor's got good harness. I'd rayther 'im have to drive that beast t'night than me." And he went into the tavern to have a glass of "somethin' 'ot."

Meanwhile the mare tore along the road like a locomotive. After a few jerks and jumps she settled down to a long trot, her head in the air, and her ears pricked well forward. But though, with her long stride, she got over the ground at the rate of some fifteen miles an hour, yet every now and then it seemed as though a thought crossed her mind that urged her to try to go one better, whereupon she would put on a spurt with a jerk that jolted the two behind her and caused their heads to nod involuntarily.

James Barnes, the doctor's man, was in a sleepy condition, and these occasional jerks just sufficed to keep him from going off altogether into the land of dreams. He had been talking matters horsey with the smith, who was accustomed to get racing tips from one of the guards of the trains that stopped at the station. Timms had told him the names of two likely winners in a race that was coming off the following week.

Of these horses, one was at 16 to 1 and the other at 20 to 1; and Jim was repeating these numbers to himself in a sleepy way, trying to decide which he would back, or whether he would back the two.

Dr. Venner, sitting firm, with a rein in each hand, found it about as much as he could do to hold the pulling mare, and prevent her from bolting. His arms ached, and his hands were stiff with the cold and the strain upon them. All the while he kept a sharp look-out on the road ahead, and, as the snow was coming down less thickly, he was now able to get a somewhat better view of the track in front of them than before the visit to the smithy.

"Tell you what it is, Barnes," the doctor presently said, "you've been giving the mare too much corn. You know she's had little work lately; yet I expect you've fed her just the same as if she went over to Felton Towers and back every day. Now, how many feeds a day have you been giving her?"

Jim, whose drowsy thoughts were running on the odds he could get, on hearing the words, "how many," answered—

"Sixteen."

"Sixteen! Barnes, you rascal, wake up. I asked you how many—"

"Beg pardon, sir," said the man, rousing himself with a sudden movement. "I should have said twenty—"

"You're drunk now!" Dr. Venner exclaimed in disgust. "I'll discharge you for this! I'll have no more—Halloo! What's that?"

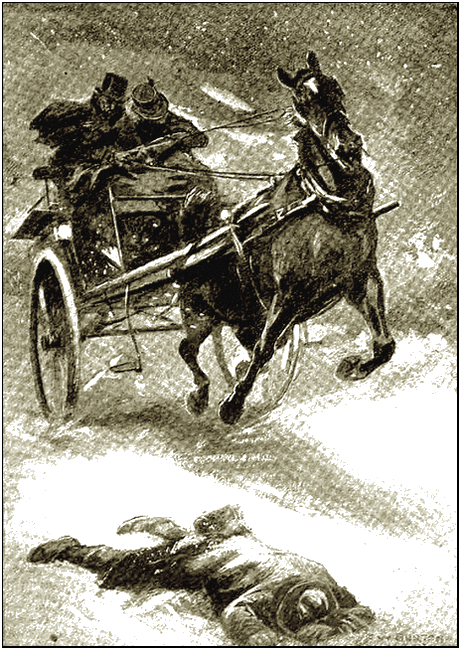

The mare had suddenly shied and swerved; then she stood still, and next began to back. In the road a dark mass that looked like a bundle was visible in the light of one of the lamps. But for the animal's quick sight they would have driven over it—probably have been upset.

The mare suddenly shied and swerved.

"Get down and hold her head," said the doctor, and the man bundled out, his master following and going to the object lying in the road.

He soon discovered that the bundle was an old man who had fallen down exhausted; and the snow had already begun to whiten his dark clothes.

Dr. Venner drew from his pocket a flask and held it to the stranger's lips. It had a good effect, for the man sat up and looked vacantly about him. Presently he moaned feebly—

"Dr. Venner, Dr. Venner! I want Dr. Venner!"

"I am Dr. Venner," was the reply. "What do you want with me?"

The stranger stared, then struggled to his feet.

"Are you the boy, then—the son—grandson, I mean, of my old friend!"

"Yes, yes. What do you want with me?"

The light from one of the lamps fell upon the two as they stood thus in the road; the impatient mare fretting and pawing the ground, while the man held her head. Dr. Venner thought, as his keen glance fell upon the stranger's face and figure, that old Brown's idea of him as "like the Wandering Jew" was no inapt description.

The old man gripped the doctor's arm and gazed eagerly into his face, scanning his features with a fixed and searching look.

"Boy!" he said, with trembling eagerness, "have you the old cabinet filled with strange chemicals and compounds that your grandfather used to have?"

"Yes—it is in my laboratory."

"Ah! And you have still a sealed jar marked, 'Amphil Saturn'?"

The strained anxiety of the speaker, as he asked this question, was almost painful.

"Yes. It is still there; but I know nothing about the use or value of the contents."

The old man's grasp relaxed, and his face expressed unspeakable relief as he exclaimed—

"Heaven be thanked! Now I am saved!" Then he turned, and again seized Venner's arm in a vice-like grip.

"Listen, boy! I will show you how to make use of that drug! I have that which will make it, when compounded, worth more than diamonds! Do you seek riches? I can make you rich!"

He paused and gazed at the doctor in anxious inquiry, but the latter shook his head.

"Ah, ha! Then you have ambition? I can make you famous!"

Venner looked for a moment into the old man's face; then said, with a shrug of impatience—

"It is cold standing here. Let me help you into my trap. Come to my house, and we can talk this matter over."

He went to the dog-cart and made the necessary alterations in the seat, then helped the stranger up and took his own place. The groom let go of the mare's head and climbed hastily into the seat behind. Just as he mounted, the animal made one of her plunges and then started off for home through the whirling snow, her hoof-beats ringing out on the hard, wind-swept portions of the road as though she had been made of iron and steel instead of ordinary flesh and blood.

"WHAT is the matter this morning, mamma, dear?" asked pretty Lilian Darefield of her mother. "You seem strangely out of sorts."

"'Strangely' is exactly the word, my dear," Mrs. Darefield answered, with a sigh. "I do not feel in any way unwell, only in low spirits. I feel as though some great trouble were impending. Heaven grant it may be a mistaken feeling this time."

Lilian looked up quickly at her mother from the letter she was reading, and her glance denoted both surprise and some little alarm. She was silent for a while, during which she returned to her letter; then she said, with a rosy flush—

"As long as you are quite sure you are not unwell, mamma, dear, I don't so much mind. I know it is true that your 'presentiments' have, more than once, proved only too truly prophetic; but, somehow, I think you must surely be wrong this time, for I have good news here!"

Very charming she looked as she said this, the rosy colour coming and going on her face, even as an arch little smile played about her mouth, dimpling the cheeks and puckering the dainty little lips in a manner that was altogether captivating. The mother's glance noted all this, and dwelt lovingly on her daughter while, listening to her light talk; but she made no reply, only allowed a half sigh, that would not be repressed, to escape her.

"This note is from Arthur," Lilian went on, "and he says he has some very wonderful news to tell me. He does not tell me what it is, but I am sure, from the way he writes, that it is something good. And, anyway, he is coming over presently, so we shan't have long to wait to know all about it."

And then the flush upon her cheek grew deeper still, and, to hide it, she rose and went over to the fireplace, where a large cheerful fire was blazing merrily away, two or three hissing logs adding their bright gleams to the little tongues of flame that played in and out among the coals.

The scene was the morning-room at Ferndale Hall; the date the second morning after the opening of this story; and the "Arthur" referred to by Lilian Darefield was Dr. Venner himself. The snow lay thick upon the ground, and Ferndale Park and the surrounding fields and open country, stretching for many miles on every side, were enveloped in a white covering. There was a hard frost, but the sun shone brightly, and, in places, a few people—mostly boys—were out sliding or skating on ponds, or on the shallow ice that had formed in some low-lying, inundated meadows. Much of all this could be seen from the windows of the room in which Lilian and her mother were sitting, and the former turned from the fire to look out.

"It looks so bright and nice outside," she presently observed, "that I think I will go for a walk into the town. Perhaps"—here there came another blush—"I may meet Arthur. But more likely I shall be back before he comes. In any case, I shall not be long away."

She gave her mother a kiss, and ran off to put on her walking-dress and hat.

Lilian Darefield was about twenty-two; she was an heiress in her own right, and was somewhat peculiarly situated. Her father was dead, and her only living relatives were her mother and her elder brother, Mr. John Esmond Darefield, commonly called the "Squire" amongst the country people, but by those familiar with him, Jack Darefield. Between this brother and herself there was a large gap as regards age, for he was over forty. There had been other children, but they had all died. And now Mr. Jack showed no signs of ever taking unto himself a wife, and if he did not, and should die first, then Lilian would become the mistress of Ferndale Hall and of all the estates and property appertaining thereto—for they were not entailed—in addition to her own separate fortune. But thoughts of all this did not trouble the little family of three who lived at the stately old Hall. They were all fond of one another—the brother, the sister, and their mother, the widowed Mrs. Darefield—and they were liked and respected all round the country, not only by their neighbours, but by their servants and dependents.

As regards the neighbours, however, there was one notable and unfortunate exception. The adjoining property on one side, called Milton Park, belonged to a Mr. Josiah Kershaw, who, for some reason or other, seemed to have conceived a deep dislike to everyone at Ferndale Hall. It had been hinted among the village gossips that Mr. Kershaw had proposed to Miss Darefield, and had been scornfully refused; hence the ill-feeling he bore them. But, be this as it may, it is certain that between him and Mr. Jack Darefield there were constant disputes and bickerings, which, at the present time, had settled down chiefly into a dispute about a belt or zone of ground and a small covert that lay on the borders of the two estates, and as to the proprietorship of which each asserted exclusive rights. This cause of quarrel naturally became most acute during the shooting season, when one or the other followed game on to the disputed territory.

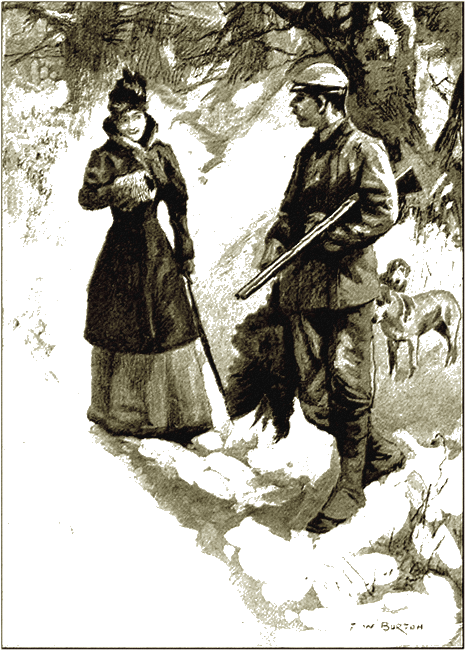

Presently Lilian appeared, neatly dressed in a small hat and long sealskin jacket, and started off across the park towards the little town or village of Milton-on-the-Moor. The chill wind brought the rich, glowing colour into her cheeks, and blew stray wisps of her fair hair about as she walked; and, with her sparkling, clear grey eyes, and her pretty face, she made a fascinating figure as she stepped lightly along the path that had already been trodden down by other pedestrians. On her way she met her brother Jack, who laughingly demanded if she were going off to meet Dr. Venner.

On the way she met her brother Jack

Mr. Jack, who had his gun and a couple of dogs with him, had already been out for an hour or two, and was now returning laden with a brace of birds. He was a tall, good looking, and good-humoured fellow, rather inclined to stoutness, and with hair turning grey. Otherwise he was dark—a strong contrast to his fair young sister.

"I see you've got something this morning," Lilian observed, by way of turning the conversation and escaping her brother's banter.

Mr. Jack's face clouded. "I should have got more," he grumbled, "if that beggar Kershaw hadn't been there yesterday. and driven nearly everything out of the copse on his own side and mine, too. It's like his cheek, you know; really, I shall have to take some serious steps. I can't put up with his impudent trespassing much longer. That ground is ours, and he knows it well; and I mean to put a stop to it."

Lilian sighed; the bright smile vanished, and she looked grave.

"I do so wish you could get that matter settled," she said. "Can't you offer to divide, or something? I sadly fear, somehow, that trouble will come out of it one day."

"I have offered to divide," Jack answered testily, "and the cad won't agree. What more can I do? I've even put landmarks here and there right across, and promised I won't go on his side of them if he won't come on mine. But he won't make any promise—he'll agree to nothing that's reasonable. So what am I to do? The 'give-and-take' business is all very well, but it shouldn't be all 'give' on my side and all 'take' on his, you know. But there, don't let us bother about it just now. If you see Venner, tell him I shall expect him over to lunch."

And with that he called to his dogs and went on, and Lilian continued her way across the park.

Now, when she reached the gates and turned into the road, whom should she see coming towards her but Dr. Venner! It was very surprising, of course; at least, she so declared it to be; but her air of astonishment did not prevent her from extending a very warm greeting to him.

"This is very unexpected," she said, demurely; "I was going to make a call in the town, and thought I should be back by the time you arrived. We did not expect you before lunch."

"Well," Venner returned, "the fact is I am like the Irishman in the story who 'had just stepped over to say he couldn't come.' I have some business in hand which I cannot well put off; so will you make my excuses to your mother and brother, and explain?"

Miss Lilian looked anything but pleased at this information. She tossed her head and wanted to know what the urgent business could be. But he evaded the question, and laughed it off. Then she asked him what the good news was that he had promised to tell her. At this he suddenly became grave.

"Ah! Well, as to that, I scarcely know how to tell you, just now," he declared. "It would take rather long. Shall I leave it till to-morrow? I will, if you like, come over to-morrow instead? Won't that do?"

No; that wouldn't do at all. She and her mother were going away on a short visit to-morrow, and might be away as long as the following day or two as well. And he had promised to tell her; he had roused her curiosity, and she was not going to have it all put off. He could tell her as they strolled together towards the town.

"Very well, then," he began, in a tone of resignation "You know, of course, what I am always working at in my laboratory; always experimenting about, thinking of, trying for, scheming, calculating, studying, working, slaving for?"

A shade passed over his listener's fair face as he asked this question. She nodded, and said, gravely—

"Yes, I know; and you know, too, that I do not agree with you. I wish you would give it up. It is but the wildest dream I feel, somehow, assured. Give it up, Arthur, and devote the talent God has given you to some line of legitimate scientific research. I am sure you will then have your reward and make a name. Whereas, this chimera that you are pursuing—that your father and grandfather pursued before you—will lead to no result, in your case, any more than it did in theirs."

She spoke earnestly, and with great feeling; and it was evident that she had thought much upon the subject, and had made up her mind to use all her influence to gain him over to her own views. And he gave her a tender glance of admiration and of appreciation of the loving interest that her words and manner expressed. But then he smiled—a curious smile.

"But what will you say, then," he went on slowly, and with emphasis, "if I tell you that I believe the end is gained? That it is found?"

"What!" she exclaimed, "the Elixir?"

"Hush!" he returned, looking round. "I don't want it talked about. I do not wish anyone to know until I am more certain about it. Anyone; do you understand? Can I trust to you not to tell even your brother, until I give you leave?"

"Certainly, Arthur. I will not speak a word of it to anyone till you say I may. But—oh, no! It can't be; the thing is absurd!"

"Strange—extraordinary—almost incredible, I know it is—or seems," he told her, quietly, "but absurd—no! for I have seen it proved under my own eyes, in my own laboratory, within the past forty-eight hours. At least," he added, thoughtfully, "partially proved—proved so far that I do not see how there can be much doubt about it."

"What have you discovered, then?" Lilian asked, almost with a gasp. "You take my breath away, Arthur. You almost make me fear—"

"That I am a little bit crazy, I suppose, Lilian," he responded, laughingly; and his open laugh and clear keen look were reassuring. "You think my researches have turned my head? No, it is not so, Lilian. You may rest quite free from any anxiety, upon that score. Indeed, this is no discovery of mine at all; it has come about accidentally, as far as I am concerned. It is, in fact, another man's, not mine. But he has given the secret into my hands, in return for something he wanted that I happened to have—"

"Money?" asked Lilian.

"No; not money—something else, left me by my grandfather. In return for this he has given me the secret to make use of at my discretion. He has no wish for fame, he says; but it is a thing that will make famous the man who demonstrates it to the world, and that man will now be myself, Lilian."

But instead of showing any pleasure at this, his hearer shivered, and looked troubled.

"I don't like these bargains," she declared. "We have heard of such things before. It sounds like those compacts with the Evil One told of in the old-time legends."

At this Dr. Venner could not help another hearty laugh.

"No; this is only a little friendly arrangement with one who was a friend of my grandfather," he said. "However, I see I must tell you all about it, then I think you will have a better opinion of the matter. I admit the thing sounds strange, as I have put it, thus crudely, to you. But the explanation, though curious, is so simple and straightforward—as it seems to me—that I do not think you will feel any more uneasiness when you have heard all there is to tell."

And with that be launched out into an account of his visit to the "Halfway" Inn, of what they told him then of a very feeble, very old man, who had been inquiring for him; of his subsequently coming across the old man himself, lying in the roadway in the snow, and of what the old man had said.

"When I got him indoors—in the laboratory," Dr. Venner went on, "he seemed to wake up considerably. His name, he told me, was Marenza; he said he had known my grandfather intimately in the East, where they had for many years been companions, fellow-workers, and fellow-travellers. 'And your grandfather,' he said to me, 'brought back a certain drug of which we had great hopes at the time; but he never found out the secret of how to employ it. I, however, did, after he left me; and I have proved, many times since, its wonderful virtues when compounded in proper proportions with certain other substances. These latter I have with me here, but the other I have not. I lost all my store in a fire some years ago. Since then I have tried in vain to obtain some more; I have travelled far in search of it, but vainly. I do not say more cannot be had—but not at present—it takes years to prepare and mature. Then a sudden idea came to me; your grandfather might have preserved the portion I knew he had—have done nothing with it. So it has come about, boy, that I have dragged myself here, after many, many years of vain walking and seeking; and—if you have the drug, I am saved—and then, if you will give me half, I will divide with you the half of all I have of what you need to compound with it, and I will teach you the secret of preparing the wonderful Elixir—the Elixir that can make the old young, and take ten, twenty years off an old man's life at every dose!'"

Venner paused musingly. Lilian looked grave, but interested.

"Well?" she presently said, "what more is there?"

"It is all so curious—so incredible," Venner replied. "I really ask myself, even now, did I dream it all? However, to go on—

"I showed this man, Marenza, as he called himself, the old-fashioned cabinet in which my grandfather had kept locked away a few of what he had deemed his most precious drugs and chemicals. The old man found and picked out what he wanted without any difficulty, and at once set to work to compound his 'Elixir.' And a very extraordinary liquid it was when made, I assure you. It foamed, and sparkled, and displayed all sorts of opalescent gleams and prismatic hues, in a manner so surprising that I was lost in wonder and admiration. He made enough to fill two bottles of equal size, one for himself, and one for me to retain.

"'This will last me for many years to come, boy,' he said. 'And the other bottle will last you still longer, for you will not need to take any yourself for many years yet; and as to selling or giving any away, why, no one but a madman would dream of doing anything so absurd with a thing so precious.' He told me that he wished to rest all night and all next day. I said he was welcome to do so; and he could have my little camp-bedstead in the anteroom to the laboratory, and I would rest on the couch in the room below. He particularly wished to avoid going to an inn, or being seen by strangers," he said.

"Then he divided the strange drugs which he had with him, and which he had used in the preparation of his 'Elixir,' and I gave him half of what was left of the other, as we had agreed. Finally, he went to lie down, and fell into a deep sleep, from which he only woke up this morning."

Dr. Venner again paused, looked at Lilian, and hesitated.

"That was a long sleep," she said.

Venner drew a deep breath, and regarded her with wide-open eyes.

"Yes," he assented—still with hesitation. "But it isn't that. The surprising—the astonishing—the almost incredible thing is that—"

"What?" she asked, eagerly now; for his manner impressed her.

"It is," he went on, "that—oh dear! you will never believe it—but, Lilian, I declare solemnly to you, he does not look like the same man! He is—ah! full twenty years younger to-day than he appeared when he lay down to sleep the night before last!"

"Arthur! You—surely you are dreaming! You have been deceived! There is some trick!"

He shook his head.

"No," he declared. "No; there is no trick. But now I go back to him, to be exactly instructed in the compounding of the draught that has accomplished such a marvellous result, for he desires to leave me shortly, having, he says, urgent business elsewhere. Well, when you return from your short visit I shall know more about it, and shall be able to give you fuller details—be able to tell you, too, how I propose to utilise this great secret in the future."

"It sounds an extraordinary adventure, anyhow," was Lilian's final comment.

They were now drawing near the outskirts of the town, and they therefore soon afterwards parted, Dr. Venner to go back to his mysterious visitor, and to what the latter had promised to teach him; Lilian to finish her errand in the town. But she left him with reluctance; for though the story had interested, and even excited her, she somehow felt many misgivings about it. She did not experience the satisfaction and pleasure which Dr. Venner had thought to convey; and thus they parted differently to what he had pictured to himself—he going away eager and with delighted anticipation, she filled with a sort of undefined dread and foreboding.

IN a room in his private cottage adjoining the police-station at Milton-on-the-Moor, Police-Inspector William Huntly sat in deep consultation with Mr. David Stone, the well-known London detective. Mr. Stone had been in the neighbourhood on other business when an urgent telegram from the inspector had reached him, begging him to hasten to Milton to assist him in the investigation of a mysterious case of disappearance that had suddenly become the talk and wonder of the countryside And now, therefore, they were putting their heads together in the hope that from their combined wisdom an elucidation of the mystery might, somehow, be evolved.

The facts of the case, so far as they were known, were briefly these:—

The 'Squire'—in other words, Mr. Jack Darefield—had gone out late in the evening, after dinner, to call upon his neighbour, Mr. Josiah Kershaw, to remonstrate with him about his trespassing upon the former's ground. Earlier in the day the Squire had been shooting upon what he considered indubitably his own part of the area in dispute, and had been annoyed to find that Mr. Kershaw had again been before him that morning, shooting and driving all the game towards his (Kershaw's) own estate. But though he was especially annoyed at the fact that this was the second or third time the same thing had lately occurred, he swallowed down his anger then, and determined to confine the expression of his opinion on the matter to a polite note, which he wrote and committed to the post-bag. But, while seated at dinner, his gamekeeper came to him with the information that Mr. Kershaw had not only been shooting and driving again that afternoon on the disputed territory, but had actually had the unheard-of audacity to follow up wounded birds some distance on to Mr. Darefield's estate—to a portion of it, that is, as to which there had never been any kind of question or doubt whatever. Then Mr. Jack Darefield, having finished his dinner, rose up, wrathful and indignant, and declared his intention of "going to have it out" with Mr. Kershaw then and there, in a personal interview; and he accordingly started out, in spite of the advice offered by his keeper to leave it till the morning.

So Mr Jack Darefield strode off in high dudgeon, and it is certain that he called on and saw Mr. Kershaw, with whom he had a stormy interview in the latter's study. What was there said or done, however, no one knew, the two being quite alone; but high words and much angry talking, or rather what was almost shouting, were heard—and that was all that was known.

Mr. Jack Darefield had not been seen since. However he had left Mr. Kershaw's residence, no one had seen him go, not even the servants. Mr. Kershaw's account was that Mr. Darefield had gone out through the window, in a state of great anger, and full of threats of the action he intended to take; the window happening to be open because he (Mr. Kershaw) had turned out a couple of dogs he had had in the room in order to let them have a few minutes' run. That, Mr. Kershaw declared, was all he could tell; and that was all that Inspector Huntly could tell Mr. David Stone. There was absolutely no clue whatever to go upon.

"Mind you," observed the inspector, "we can scarcely suppose that Mr. Kershaw killed Mr. Darefield and has hidden his body; no, no; we cannot suppose that, of course. Yet, from the time he is shown by Mr. Kershaw's servants into that gentleman's study, he is never seen again. And there was undoubtedly a quarrel—a bitter, stormy quarrel, between the two. Now what can you make of that, David Stone?"

Mr. Stone didn't know what to make of it, and said so, albeit he tried to look "wondrous wise." After a further short talk, he rose to go out for a stroll round the neighbourhood—which was well known to him—partly to make some "investigations," and partly in the hope that something might "turn up."

Accident favoured him, for, late in the afternoon, he chanced to be passing a pond where some children were sliding, just as the ice gave way and some of them fell in. Most of them were in shallow water, and got out again easily enough with only wet feet; but one, a little girl, fell into, what was to her, deep water, and she would have fared badly if Mr. Stone had not been there to fish her out. As it was, she was nearly dead with cold and fright, and he carried her to her home, a labourer's cottage, near at hand, where her mother took her and put her to bed; and the rescuer was gratefully thanked by both father and mother. The latter, whose name was Young, happened to be at home, he said, because he had been thrown out of work by the frost.

Meanwhile, both Mrs. Darefield and her daughter were in entire ignorance of what everybody in the neighbourhood was talking about. It was not, indeed, until they returned home from their visit that they learned what had really happened. They had been away when Mr Jack had received the news that had so angered him; and when, the next morning, it was found at the Hall that he had not been home all night, no particular importance was attached to it. He now and again stayed at the "George" Hotel in Milton, if the fancy took him; more often, however, he had stayed so late at night watching Dr. Venner at his experiments that he had preferred to lie down on the doctor's couch to troubling to go home. Thus, the butler, Mullins, had not at first troubled much about the matter. It was only when the day drew on, and no news coming of his missing master, and he had made inquiries in two or three directions, that he began to wonder, and then he grew alarmed. Even then, however, he only wrote a brief note to Mrs. Darefield, saying that Mr. Jack had not returned. Later on he called at the police station, when, after hearing what he had to say, the inspector took the matter up at once.

Thus, as already stated, it came about that Mrs. and Miss Darefield returned home in entire ignorance of the commotion that had by that time arisen in connection with Mr. Jack Darefield's strange disappearance and unaccountable continued absence; and their consternation and distress, when the true state of the case was suddenly made known to them, can well be imagined.

"And Dr. Venner—what does he think of it, Mullins?" Mrs Darefield anxiously asked of the butler.

To their great surprise they then learned that the doctor had not been to the Hall.

"I haven't seen him; so I can't tell what his opinion may be, ma'am," Mullins declared. "I sent George, the groom, over to him, to ask if he had seen anything of Mr. Jack, but he said he hadn't; and that's all. Maybe, ma'am, he is busying himself helpin' the police to look for Mr. Jack."

"Yes, yes, it must be that, mamma," Lilian exclaimed. "And of course he knew we were away."

All the same, it seemed strange he did not come up to the Hall now they were back; and it seemed stranger still when the next day passed, and still he came not. Only a brief message arrived from him, expressing his regret at the "strange absence of her brother," and a hope that he would soon return safe and sound. That was all; and in her bewilderment at such unexpected treatment Lilian was filled at first with astonished indignation, and then with a vague undefined fear. What could such unexpected behaviour on his part mean? Was he ill? Had something untoward happened in connection with that strange "uncanny" affair he had told her of—and was he averse to coming to see them lest he should seem to be adding trouble of his own to theirs?

All sorts of thoughts and ideas crossed her mind; some reasonable, some wild and almost impossible. Finally, she wrote him a note, telling him the wonder and distress his silence and his failure to come and see them in their trouble were causing her mother and herself, and begging him to tell her the cause. In reply, the messenger brought back only a verbal message to the effect that Dr. Venner was very unwell, and unable for the present to go out, but that he hoped to be able to come over in a day or two. And that was all! Thus was now added to her former load of distress alarm and anxiety at the inexplicable behaviour of the one upon whom she had ever thought she could most confidently rely in a time of trouble, such as the present.

IT is necessary here to describe Dr. Venner's laboratory, and to explain how it came about that he had a bed there, in which he had allowed his mysterious visitor to sleep for two nights and a day without the knowledge even of his, the doctor's, own servants.

Dr. Venner's residence was a large, rambling, old-fashioned place, known as "Moorfield House," standing, as the house-agents say, "in its own grounds." The front looked out on to a large, irregular expanse that might, perhaps, be described as the village green, only that the residents of Milton-on-the-Moor considered their assemblage of houses and cottages a "town," and not a village.

The laboratory was built away from the house and the stables at the furthest end of the back garden. Thus it stood quite alone, in a corner, abutting on a lane which ran along at the back of the adjacent gardens and orchards. There were no other buildings anywhere near it, or in sight of it; the house and stables and all the nearest dwellings or sheds being hidden by trees and thickets.

The laboratory building consisted of four rooms, two on the ground floor, and two above; but the two on each floor were unequally divided. Above were the laboratory proper—a large, long room—and a small anteroom fitted as a tiny bedroom, and containing a camp-bedstead; while downstairs were a large sitting-room or "surgery" and a small dispensary, where was the usual stock of bottles, drugs, etc., of a country doctor. As, however. Dr Venner had no patients in particular, and never sought any, the various compounds contained in his dispensary were very seldom called for. The chemicals and apparatus most in use were those upstairs in the laboratory; and here Dr. Venner was accustomed to spend day after day, and very frequently night after night, absorbed in abstruse experiments, and "kicking up," as Mr. Samuel Pateman, the draper, was wont to phrase it, "vile, foul smells." However, since the laboratory stood so far away from other buildings, these "foul smells," affected nobody but himself; and no one else, in fact, troubled themselves much about them.

The larger downstairs room had two doors, one opening into the lane and the other into the garden, with the high garden wall between the two. The place had been originally built by Dr. Venner's grandfather, who had "experimented" there year after year, nearly blowing himself up now and again; and much the same thing might be stated of his successor. The present Dr. Venner had modernised the place a great deal, and had made it a comfortable little dwelling to reside in when he chose. Often he would live there for days together, having his meals brought down to him, and always making his own bed. For he never allowed servants upstairs, lest they should, actuated by curiosity, go into the laboratory and interfere with his precious apparatus there. To render himself still more independent of his own servants, he had gas and water everywhere laid on, and had gas fires below and a gas stove and furnaces above. Thus he never required coals, candles or lamp oil. What dusting and cleaning he deemed requisite upstairs he cheerfully executed himself. Lastly, he had had a telephone connected with the house, by which means he was informed when visitors called, and was able to intimate whether he would come up to see them, or wished them to come down the garden to his "surgery," or, finally, as often happened, desired the servant to say he was too busy to see anybody at all.

During the days that followed Mr. Jack Darefield's unaccountable disappearance, Dr. Venner remained constantly in this laboratory. He slept there, he stayed there nearly all day, and had his meals brought down to him—such as they were—for he complained of feeling very unwell, said he could not eat, and ordered only the simplest fare; and even of this he appeared to take next to nothing. He had kept his word to Barnes, his coachman, and had discharged him—much to that individual's surprise and disgust—the day after the visit to the "Halfway" Inn. And, in order to save the trouble of getting another man in his place just then, had himself taken the mare over to the "George" Hotel stables, and had left her there, snugly ensconced in a loose box, at livery. It was Barnes who had chiefly been used to wait on the doctor at the laboratory, and to do such dusting and cleaning as might be required downstairs there; and now that he had gone, it would appear that Dr. Venner must be doing this for himself. At any rate, he never troubled the maidservant, who came with his meals, about it. Once or twice during the day he would lock the place up and go across to the police-station or elsewhere, make a few inquiries as to whether anything had been heard of Mr. Jack Darefield, and then return and shut himself up again. He never stayed out long, and never went as far as the Hall, and, naturally, conduct that was so strange under the circumstances soon began to excite comment. In particular, it speedily brought upon the doctor the special attentions of Mr. David Stone, who paid him two or three (evidently unwelcome) visits.

Then Mr. Stone made his report to the inspector. And this is what he had to communicate:—

"There is a man about here," he began, "whom you no doubt know to be an occasional poacher, one Bill Bradley, or Black Bill, as they call him."

The inspector nodded assent. "He has been convicted and imprisoned three or four times for poaching; twice on charges brought by Mr Darefield," he said.

"Exactly; and therefore there has been no love lost between those two. Now, it seems that the man Young, whose little girl I picked up out of the pond the other day, is a sort of crony of Black Bill, and knows a good deal about his movements. Between ourselves, I suspect they do a little bit of poaching together on occasion, though Young did not say so; and I do not wish to do him any ill-turn by exciting your suspicions, for his information has been of the greatest use to me."

The inspector nodded again. "All right, drive ahead," he put in. "I will remember it in his favour should occasion arise."

"Good. Well, then there is another man—a drunken fellow—named James Barnes, till lately a coachman to Dr. Venner, and discharged by him the other day."

"I know him. Go on."

"I have found out from this Barnes a very curious circumstance which appears to have escaped your notice. On the 12th inst.—just ten days ago—an old man—a very old man—so old and strange-looking as to be certain to be remembered if once seen—called at the 'Halfway' Inn, and inquired for Dr Venner. It was the night of the first fall of snow, if you recollect. He had come by train, he said, specially to see Dr. Venner. He seemed to have money; and it so happened that he dropped a curious old large gold coin, which he declared was—and which I believe to be, for I have seen it—very valuable. It rolled down into a crack between the boards, and could not be recovered without taking the board up. The old man would not wait for this to be done, but started off on foot through the snow, saying he would call in for the coin on his way back from Dr. Venner's to the station next day or so. Shortly afterwards, Dr. Venner himself stopped at the inn to have a loose shoe fastened, heard of the old man's visit, and finally, on his road home, comes across the stranger lying in the snow. He takes him home with him—this I learnt from Barnes—to his 'surgery' or laboratory, or whatever it is, and there takes him inside and mixes him up some medicine and gives him some supper. This, as I have said, I learned from the man Barnes, who waited on them and brought the supper down from the house."

Mr. Stone paused, and the inspector raised his eyebrows inquiringly.

"Well?" he said. "I don't see much in all that."

"You will, directly. What has become of that old man? Can you tell me? Where has he gone to, and who saw him go? He has never been seen since that night, and he has never gone back for that valuable old gold coin. Brown, at the 'Halfway' Inn, has it now waiting for him!"

Inspector Huntly sat bolt upright, and showed by his looks that he was now, at any rate, surprised and interested.

"Ah!" Mr. Stone remarked sententiously, "I thought that would surprise you. But it's nothing to what is coming!"

He paused for a few moments, as though to emphasise the more what he was about to add.

"What will you say, I wonder, when I tell you I have ascertained, beyond any reasonable doubt, that Mr. Jack Darefield likewise went into Dr. Venner's one night—in fact, straight from his row with Mr. Kershaw? And you know that he has never been seen again either!"

Inspector Huntly sprang up.

"Nonsense!" he exclaimed. "Impossible! Who has been gammoning you with all this?"

The detective laughed—a low, self-satisfied sort of a laugh.

"The man doesn't live—certainly not hereabouts," he observed, quietly, "who can 'gammon' David Stone. However, I'll tell you how I got at it, then you'll understand better. To go back to Young and his poaching friend—Black Bill. As I gather, Black Bill has been in the habit of watching Mr. Darefield into Mr. Venner's of a night; then he would climb up on the wall and peep in at the window of the laboratory, through a crack in the blind, which gave him a full view of the room and all that went on there. Sometimes, too—especially if the window was a little open—he could hear much that was said. Thus he could judge whether Mr. Darefield was likely to stay or not. Often, it seems, the Squire stayed there all night."

"I know," said the inspector, impatiently. "Go on."

"It further appears that Mr. Darefield was given to frequently acting as his own gamekeeper, and he would often roam quietly and alone, and at all times of the night, through his coverts and over the fields in search of possible poachers. Now, if Master Bradley got to know that he was booked for the night with Dr. Venner, he knew, of course, that the ground was clear, and he could then go off on his little expeditions with a lighter heart. Do you follow me?"

"Of course! Still—I don't see—"

"You will, directly. Sometimes, Bradley having 'located' Mr Darefield at the doctor's—as the Yankees would put it—would simply leave his chum Young on the watch, and then go off himself. If Mr. Darefield did not remain at the laboratory, Young, who knew the direction in which Bradley had gone, would then manage to warn him.

"Now, on the night referred to, Young, who was out, saw Mr. Darefield coming along, and, as he put it, talking loudly to himself and swearing and going on generally. Young wonders what's up, and slips into the shadow of some trees to observe him. Then, just as the Squire had passed, Black Bill comes slinking along, evidently following him. Knowing the bad feeling that existed between the two, and surprised to hear the Squire swearing and threatening in such unusual fashion, Young gets hold of the idea that he had had a row with Bradley, and feels alarmed at seeing the latter so stealthily following him. So he, Young, in turn follows the two, and he sees Mr. Darefield go into Dr. Venner's. Thereupon he goes up to Black Bill, and after some talk, agrees to remain on the watch while the other goes off about his 'business.' He volunteered this, he declares to me, because he was genuinely frightened, and mistrusted Bradley. And he stayed on the watch till Mr. Darefield went to bed in the doctor's little room. This he knew by peeping through the blind. Then, and not till then, Young went home himself. I have seen Bradley, and he separately confirms this statement."

Young, in turn followed the two.

"H'm! But why, then, have these two men kept silent all this time? They know of the hue-and-cry that has been raised, that Miss Darefield has offered a reward for even a little information and—"

"Don't you see that Bradley disliked Mr. Darefield so much that he does not care a button what may have become of him. Besides, he could not well tell what he knew without confessing too much of his own little goings on. 'I likes the doctor, an' I don't like the Squire,' the rascal said, brutally, to me. 'Why should I tell on the doctor for the sake of a chap I don't like?' And Young kept silent because the other told him to."

"It's all very strange, and, if true, very serious," commented the inspector, thoughtfully. "Upon my word, I'm really sorry to hear this. Even now I can scarcely bring myself to believe that suspicion rests upon Dr. Venner. No one in the place would believe it—certainly not on the unsupported testimony of a couple of poaching rascals like Young and Bradley."

"N-no," Mr. Stone admitted, slowly. "Seems a little thin when you put it like that, doesn't it? But then, there's the other man—where is he? Here you have it stated—by different people, mind, that two men have gone into Dr. Venner's lonely little place late at night and have never been seen to come out again!"

"Ah! That certainly does seem odd."

"Then," Stone continued, "Dr. Venner's behaviour is in itself suspicious. He shuts himself up there continuously, just as though he had some secret to guard, and were afraid to leave the place. He does not even go to the Hall to see—to try to comfort—his friends there—the young lady he is supposed to be engaged to! How does that look?"

"As you say, it certainly does all seem suspicious when you look at it that way."

"Finally—I am sorry to say it, but it is true—Dr. Venner's manner is suspicious, too. I have interviewed him two or three times, and can get no straightforward answers from him at all. I feel convinced he is hiding something."

"To come to the point, however—have you any plan to suggest?" Huntly asked.

"Yes; it is this. To-morrow evening—it is too late to-night—send for him over here on some pretext, and manage to keep him for half an hour. I have keys ready with which I can get into his place; then I will have a sharp look round, and we must be guided afterwards by what turns up."

The inspector ruminated, but at last consented.

"I don't like it," he said, "and if nothing turns up, and he discovers what we have done, I shall catch it finely. However, it seems the only way to set the doubt at rest, so let it be done."

And it was done. It was carried out the following evening. It was a Saturday night, and there happened to be a brawl at an alehouse that took the inspector out and kept him engaged till rather late. Then he sent a hasty message across to Dr. Venner, begging him to come over and see one of the brawlers who had been stunned by a fall while fighting.

Scarcely had the doctor started out, when Mr. David Stone, who was on the watch, slipped in. He did not remain ten minutes, then he came out, locked the place up again as he had found it, and hastened back to the inspector's private house. He quickly made his presence privately known to that officer, who then left Dr. Venner free to go home, and hurried in to the detective.

"Have you discovered anything—but I see by your face you have," he said quickly. "You look as though you had seen a ghost!"

"I have seen worse!" returned Stone. His face was pale, and his voice shook a little.

"What have you seen?" the other demanded, eagerly.

"I have seen," Stone answered, with grave, almost solemn emphasis, "I have seen Mr Jack Darefield lying dead upon Dr. Venner's bed in the little upstairs room next to the laboratory!"

TO say that Mr. Inspector Huntly was thunderstruck at the detective's revelation would convey but a very inadequate idea of the effect the news produced. For some minutes he almost refused to credit the statement, and regarded his confrère with a look that almost suggested that that worthy gentleman had been drinking. Mr. Stone himself almost confirmed the idea, his manner was so unlike himself. He wiped the perspiration from his brow as though he had been out in the summer sun instead of the bitter north wind with snow and thick ice around; and he seemed—now that he had made his astonishing statement—to have lost the power of speech.

"I don't wonder that you should stare at me like that, Huntly," he presently said, "I can scarce believe it myself. I've had a shock—a terrible shock! And I'm sorry, too, sorry for both of 'em; for him and for her—Miss Darefield. She looked so white and sad, and yet so sweet, when I saw her and talked with her. I've seen her twice, poor thing, and she was trying to bear up so bravely! How will it be with the poor child now? But there—the question is, what is to be done next?"

The inspector was a man of action, and he promptly took his decision.

"I must go to the nearest magistrate, Mr. Dalton," he said, "and swear an information and get a warrant. Do you watch unremittingly outside the doctor's place the while, and on no account go away till I come—even if you have to watch all night. Mr. Dalton lives some miles from here, and he may not be at home—in fact, I heard to-day he had been called away on some urgent business—illness of a relative or something—but was expected back to-night. So if he is not in I shall wait for him, if I wait all night. Do you understand?"

"Perfectly," the detective returned, and the two separated.

MR. DAVID STONE'S watch outside Dr. Venner's laboratory was

cold, silent, and lonely, and even to the seasoned detective the

duty was anything but pleasant or congenial. The hours slowly

passed, and still the light in the laboratory was never put out

or lowered. Two or three times, as the night wore on, the

detective, wondering greatly, crept softly up to the wall and

peered in at the window through the space in the blind as the

poacher had done. But each time he saw only the same

thing—a man with a hard, set, white face, sitting, writing,

writing, and still writing, while the hours dragged

by—writing as though fearful he would not get his task done

before the dawn. And as David Stone walked noiselessly to and fro

in the soft snow that face seemed to haunt him. For it was such a

face as a man might bear who was resolutely determined on

self-destruction; and he wrote on as a man might write who is

penning his last farewell to the world, and yet has so much to

say that he cannot get through it fast enough to satisfy his own

feverish impatience.

And then into the detective's mind another white face would come—the face of sweet, tender-hearted Lilian Darefield; and yet again her face as he knew he should see it to-morrow when she came to know the terrible, fatal truth!

"God help the poor child!" said David Stone to himself, with a sigh. "I never had a job I relish so little as this one. Will Huntly never come? Is he going to be all night? If so, he'll be too late to make his capture—of that I feel pretty certain. With the dawn—or before—the doctor will have finished his writing, drained his draught, and said 'Good-bye' to us all. That it will be so I feel assured. Well, Heaven knows, but perhaps it may be for the best so. I am not so sure I would wish to interfere to stop him, even if I had the legal power."

The night passed, the dawn came, the gaslight faded out of the doctor's window, and then at last Huntly arrived. At first he questioned Stone more by signs than words—he feared, where they then were, to risk even a whisper. But soon he drew him a little way off, and under cover of the wall, told him be had to wait for the warrant because Mr. Dalton had been kept out nearly all night by the illness of his relative.

"But now," he said, "all is clear. Let us go in."

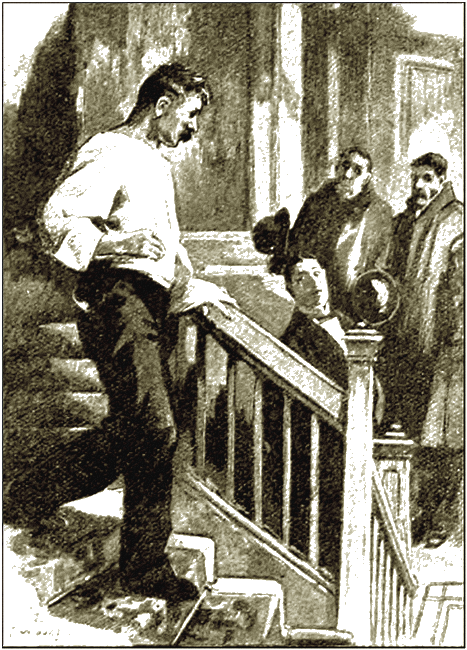

They knocked at the door, and almost immediately the window above opened and a man's head appeared. Stone looked up and recognised—not without a slight start of surprise—Dr. Venner. He disappeared, however, as quickly; and they plainly heard him descend the stairs and unfasten the door. A moment later they were inside, and Dr. Venner had turned up the gas, for the blinds were down and the room still dark. He was pale, but apparently quite collected, and he asked, with some show of surprise and impatience, what their business with him was at so early an hour on a Sunday morning.

"If," he said, with marked coldness, "you have any call upon my professional services again this morning, why that of course is one thing. But if you have only called upon your own professional business, really I must tell you I am very much engaged just now. I should not otherwise, indeed, be about so early on a Sunday morning."

This cool and most unexpected speech nettled the inspector as much as it surprised him. It had the effect, however, of nerving him to go straight to the point at once.

"We have come, Dr. Venner," he said, "upon a most unpleasant duty. I have here a warrant for your arrest for murder."

"My arrest—for murder!" Dr. Venner exclaimed. "Surely you are joking! For whose murder, pray?"

"For the murder, Dr. Venner, of your intimate friend, Mr. Jack Darefield."

Dr. Venner looked first at the inspector and then at Stone.

"The murder of my friend, Mr. Jack Darefield?" he repeated, as though incredulous. "Surely you are mad! Have you two, h'm! I don't wish to say anything offensive—but— really—have you two been out all night, and partaken of refreshment, 'not wisely but too well?'"

He looked so genuinely surprised, it was impossible to make out whether he was acting or not. But Inspector Huntly got out of temper.

"Dr. Venner," he said sternly, "let us have no more of this fooling. It is not seemly, sir; it is a most serious business, as you very well know. I must now proceed to do my duty; and it will be your own fault if—"

"One moment, Inspector Huntly," said Dr. Venner, holding up his hand, and speaking with equal sternness. "One moment, sir. Come with me as far as the bottom of the stairs, will you? You need not be afraid," he added, contemptuously, as the other hung back. "I am not going to hurt you."

He went quietly, deliberately, to the bottom of the stairs, the inspector following. And there the doctor called out:

"Jack!"

"Hullo!" answered a voice from above. "What's up?"

"All right; will be with you in a trice," came the reply.

Steps were then beard descending the stairs, and a moment or so later there appeared, in a state of costume which may be described as very much "undress," no less a person than Mr. Jack Darefield himself!

A moment later there appeared Mr. Jack Darefield himself.

The two visitors stared, looked at each other, then at the imperturbable doctor, and then again at Mr. Jack Darefield; and stared at him harder than ever.

"Well?" said Mr. Jack, looking at the doctor. "You called me, did you not? What is it? Good morning, inspector. Good morning, Mr. Stone. You see I remember you; was it you who wished to see me?"

But the astounded inspector could not find his tongue. Meanwhile Dr. Venner spoke, and in the same cool tone:

"The fact is, Jack," he explained, "these two good gentlemen have discovered a very considerable mare's nest. They have come here with a warrant to arrest me for your murder! I told you you would get me into trouble over this escapade of yours. Now see what you have done, and the unnecessary trouble you have put these two gentlemen to!"

Then Mr. Jack laughed, and, going over to the inspector, said:

"I don't quite understand why this should be; but if any needless trouble has been caused, it is all my fault, and no fault at all of Dr. Venner. I am very sorry; and I offer you my apologies. Pray accept them and go away now; later on, if you will come and see me and have a cigar and glass of wine with me, I will explain more fully. At present I only say it is all my fault."

"Very well, sir," returned the mystified inspector; and there being nothing left to stay for, he and Mr. Stone bowed themselves out.

They walked off together, but had not got far when Mr. Jack, calling to Huntly, beckoned him to come back to him.

"Huntly," he said to him in a confidential tone, "I want you to do something for me. I know you are not a bad-hearted fellow, and will do it with tact. Go up at once to the Hall and break the news of my return to my mother and sister. Do it gently and carefully—and then tell them to get some breakfast for me and for Dr. Venner, and for yourselves too. We will follow you up there very shortly. And here is a sovereign each for yourself and your friend yonder—and more to come, by-and-by, if you keep my counsel for me over this business."

Then the inspector and Mr. David Stone both lost their glum looks of a minute before, and started for the Hall. There they performed their mission with such tact and success that very soon Mrs. Darefield and poor white-faced Lilian were smiling and beaming through tears of joy. Ere long, almost everybody about the place was laughing and shaking hands, now with the inspector, now with Mr. Stone, and anon with one another. Having done which, some would fly off in an excited fashion up and down stairs, and along passages, or across the yard to the stables, and thence on to the farm-bailiff's house and the labourers' cottages around, to tell the good news to all who had not yet heard it. And that was a happy Sunday morning for all at Ferndale Hall, and the folk who lived around it.

LATER in the day Dr. Venner told the strange tale of what he

had passed through, privately, to Lilian and Mrs. Darefield, and

an abridged version of it to the inspector and Mr. Stone. The

latter, however, never heard the whole story; only so much of it

as was deemed necessary and reasonable; sufficient, that is, to

satisfy them from a legal point of view, as it were. But since

they were well rewarded for the trouble they had taken, they went

away quite content, and spread about the account Mr. Darefield

desired put forward, which was, that the whole affair had been a

misunderstanding; he had been called away on important business,

and a telegram had miscarried, and so on. What assisted, in no

small degree, to commend this simple explanation to the world of

Milton-on-the-Moor, was the curious fact that Mr. Jack Darefield

looked so much the better for the "change" he was supposed to

have had, that everybody wondered where he could have gone

to.

"Must have been to the seaside," said one. "If it wasn't for the time of year I should have said he'd been on a rattling yachting cruise," remarked another. "I should like uncommonly to know where he'd been; I'd go for a week myself," declared a third. All were, in fact, agreed upon one point, however they might try to account for it, and that was that Mr. Jack appeared wonderfully refreshed by the "change of air" he had enjoyed. "He looks fully ten years younger," Mr. Pateman, the draper, said; and that was, in fine, the general opinion. On the other hand, it was just as generally agreed that Dr. Venner looked fully ten years older; and when, a few weeks later, his hair turned gradually grey, it was agreed that he looked nearly twenty years older. Then folk wondered, and sagely wagged their heads and invented all sorts of stories to account for the phenomenon. But the real cause of it was never revealed to them; for none but Lilian and her mother and brother ever heard the true story of the terrible experience he had undergone; of the suffering that had indeed turned him suddenly from a young man into an old one.

Here are the actual facts of the case:

When Mr. Jack Darefield left Mr. Kershaw at the end of his stormy interview with that gentleman, he went, as Mr. Stone discovered, to Dr. Venner, to whom he proposed to give an account of the whole matter, with a view to asking his advice. He found the doctor intent on some particular experiments he had in hand, and evidently too much absorbed in his work to pay much attention to Mr. Jack's long and tempestuous denunciations of the unspeakable "cheek" and impudence of his ill-behaved neighbour. Dr. Venner was himself, however, in a state of high good humour—or rather, one might even say, elation. His strange visitor had gone, leaving behind him, however, a bottle of the wonderful "elixir"; and the doctor was busy manufacturing some more. Presently, partly to pacify Mr. Jack's anger by turning his thoughts into another channel, and partly to relieve his own over-wrought feelings, he proceeded to tell him the whole affair, very much as he had already told it to Lilian. Very soon Mr. Jack's boiling indignation was totally forgotten, and he was sitting listening, literally open-mouthed, to the doctor's astonishing narrative. At the end of it he plied the latter with all sorts of questions, then took up the marvellous mixture and examined it, and tasted it by putting a little on his tongue with his finger, and so on.

"And you mean solemnly to tell me, Venner," he said, "that your mysterious visitor, after taking a dose of this queer-tasting stuff, and sleeping for thirty or forty hours, went away a younger, a different looking man!"

"It is true!" Dr. Venner gravely affirmed. "So great was the change that—as he himself laughingly said—he could not go back to the 'Halfway' Inn to recover the old coin he dropped there. 'They would never believe I was the same man,' he said, 'and would threaten me with the police for trying to steal the coin, or something. I must be content to lose it, I suppose. But if you care to have it you might claim it for me—they knew I was coming to seek you—and you can keep it as a curiosity and a memento of my visit.' So you see he has not gone there to claim it because old Brown and his wife would never believe he is the same man."

"What are you going to do with this stuff?" asked Mr. Jack, thoughtfully.

"Put it away," said Venner, with decision. "At any rate for the present, while I consider what I shall do. You see—as my visitor put it—I shall not require a dose of it myself for years to come."

"Just so, just so," Mr. Jack agreed. And then he seemed to fall into a deep train of thought, and became silent.

And what he was thinking was something like this:—It was all very well for Dr. Venner to say that he (the doctor) would not require any of the "elixir" for many years to come—but that was not his, Mr. Jack's, case. He himself was, as he knew, "getting on," and what was more, he "showed it," as they say. Now, why should not he try a dose of this wonderful mixture, and wake up in a few hours ten or twenty years younger? Yet he shrank from suggesting this to Venner; it seemed childish, foppish, foolish. He longed to make the experiment, yet could not make up his mind to propose it to his friend. Suddenly an idea occurred to him; he could take the draught secretly and go off home at once. Venner need not know till afterwards.