RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old magic-lantern slide (ca. 1890)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old magic-lantern slide (ca. 1890)

The English Illustrated Magazine, 1906

with "The Death-Cry in the Forest"

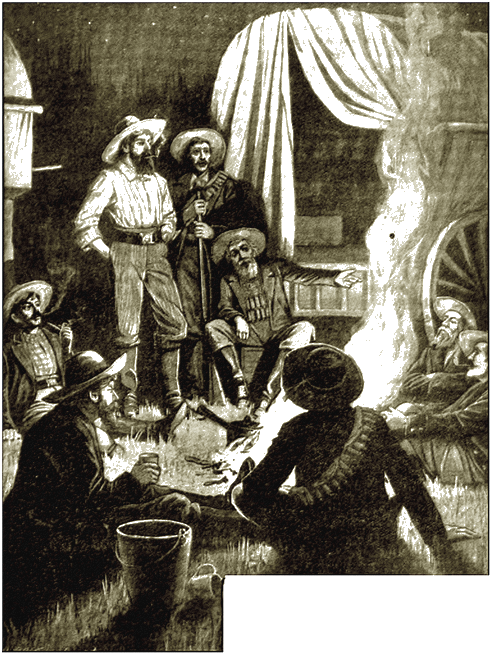

THE following weird and remarkable story was told beside the campfire in one of the wildest parts of the "veldt" in the interior of South Africa, by an old hunter who had joined our party. We were trekking east, away from the Boer settlements, upon a hunting expedition, and had out-spanned that evening at a place indicated by him as suitable for a camp, for he had been over the ground before. He was a hard-visaged, grizzled, and somewhat rough, but not unkindly veteran of the forest and plain, with some forty or fifty years' experience of wild life in all its ever-changing phases. His name was Max Fuller.

While he was telling his strange tale, the deep roars of lions, mingled with the cries of hyenas and wolves, were to be heard every few minutes, and its interest was augmented by the fact that, as he informed us at starting, we were then at the very spot where the occurrences he narrated took place. I cannot now pretend to recall his picturesque phraseology, but I give his narrative as nearly in his own words as I can remember. It was as follows:—

"It is now ten years since the affair took place, but I shall never forget the impression it made upon me. It occurred moreover here where we are now out-spanned, for most parties make this a halting place for the sake of water.

"I was, at the time, with a large party of emigrants—chiefly Boers and their families—who were trekking to take up new ground, and we out-spanned here a few days, to wait for another and smaller party to come up with us. Amongst our numbers were two Englishmen, brothers named Martin and Charles Stirling, going to seek their fortunes and take their chances in a new settlement, and in particular in company with a family named Schomburgk. Old Schomburgk had his wife and two daughters with him, the latter named Margaret and Zoe, and it was easy enough to see that the two girls formed the attraction that was drawing these two Englishmen away from civilisation to rough it in the wilds of the interior. But for this very self-evident fact, one would have wondered why two such young men should think of taking up such a life, particularly as regards the younger, who was of somewhat weakly constitution. The elder, Martin, was more robust, and he seemed to exercise a sort of watchful and anxious protection over the other. As regards the young daughters of the old Boer, they were two as pretty damsels as it has ever been my fortune to set eyes upon, and it was therefore no matter of surprise that they should exercise such an attraction over the two young men. It was clear that Charley Stirling was over head and ears in love with the dark-eyed Zoe; while Martin, though less demonstrative, was equally devoted to the blue-eyed Margaret. Both brothers were general favourites, but 'Charley,' as everyone called him, was perhaps liked even better than his brother; the latter being more reserved, and therefore not quite so well known to many of us.

"I have said that the Stirlings were general favourites; still I should make a reservation. They were certainly liked by all the leading members of our party, but there were two or three rough ones amongst us, doubtful characters in some shape or another, as to whom this remark would not, perhaps, apply. Certainly it did not in the case of one of these named Meyer, and some of those with whom he associated. Meyer had been acquainted with the Schomburgks, and had been one of the pretty Zoe's suitors before the Stirlings had appeared on the scene, and in some morbid, obstinate way of his own had quite persuaded himself that he had a sort of prior right to her affections, and that 'Charley' had unfairly and unjustifiably ousted him from the place he would have otherwise occupied in her regard. He was a morose, cross-grained fellow, with a temper and disposition that was constantly involving him in disputes, so that, with the exception of two or three of the company, he had scarcely a friend amongst the whole party. He kept mostly to himself, riding and walking alone, occupying himself in watching Zoe and his rival, and scowling at them from a distance. More than once I saw heads shaken gloomily by some of the elders among the emigrants, and overheard anxiously expressed hopes that no mischief would be the outcome of this state of things.

"Such was the position at the time we arrived here and out-spanned at this camping ground.

"Such was the position at the time we arrived

here and out-spanned at this camping ground.

As we were to remain several days, it was arranged that each day a certain number of us should go out and hunt for game for the general benefit; but I was suffering from an attack of fever—not serious, but sufficient to make a rest advisable—and consequently I remained in camp all day and did not go with the hunting parties. I used to occupy myself pegging out and dressing the skins of animals brought in by the hunters; there were many mouths to be fed, for we numbered nearly seventy persons, all told; and those we were waiting for would bring the number up to a hundred or more.

"We had appointed a leader, an old Boer named Niemann. He had his lieutenants, of whom I was accounted one, and he exercised a strict discipline throughout the camp as well as on the march.

"Several days passed without any incident of note. The Stirlings went out with two or three others in a small party of their own; and Charley would often leave them early and return alone, bringing on some of the game killed, with which he loaded his horse, and Zoe would be on the look out for him in the afternoon, and go to meet him a little way out from the camp when she saw him in the distance.

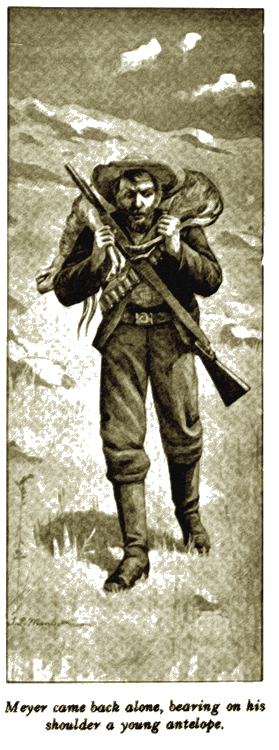

"One day he not only failed to appear during the afternoon, but his brother returned without him and was greatly surprised to find him still absent, saying that Charley left them some two hours before to come on in advance as usual; thereupon there was great consternation, as first one party, and then another, came in, and declared they had seen nothing of him. Meyer came back alone, bearing on his shoulder a young antelope, which he silently threw down by the side of the general 'bag.' The blood from the antelope seemed to have trickled over him as he carried it, for he was bloodstained in several places, as we all, then present, could but notice, and he was scratched as though by pushing through thorns, while his clothes were here and there torn.

"When our leader, Niemann, questioned him as to whether he had seen anything of the missing man, he answered in a surly tone that he neither knew nor cared what had become of him, and went off to his waggon, amid suppressed murmurs from the bystanders. Search parties, headed by Martin Stirling, then started off to look for Charley, and after they had gone I went over to the Schomburgk's waggon to carry such poor comfort as I could to those who I knew would be in sorrowing anxiety there. Naturally, Zoe was in a state of great distress, as time went on and no tidings came. Presently it grew dark, and occasional shots were fired to guide the searchers back to camp, it being not only useless but dangerous to continue the search in the dark. After a while they all returned unsuccessful, Martin Stirling being the last, and when Zoe saw him coming in alone, she gave a great cry, saying, 'He is dead, he is dead, I knew it—I knew it! I knew it! I have known it all day! Oh Charley, my darling, my poor darling!' and fell down in a swoon, and was carried by her father and mother into the waggon.

"We were a mournful community that night, for I don't think that anyone of us doubted that poor Charley Stirling was dead. Of course, it might have been that he had merely lost his way, and would return in the morning, or be found by some of us, with no worse experience than that of having had to pass the night in a tree. Yet, though this was possible enough, still, somehow, we feared the worst, and that for reasons that each one knew, yet durst not avow to one another. What the general feeling was, however, was manifest from the furtive glances cast in the direction of the waggon which Meyer shared with two of his 'pals.'

"Martin Stirling refused to go to rest in his waggon, and sat outside it in moody silence, hardly stirring, and scarcely, I thought as I sat watching him, seeming to breathe. But when the firelight caught his face, I could see that he was wide awake, and that he never removed his eyes from the waggon in which Meyer was. Divining his thoughts, I went over and whispered to him, 'Get some sleep, my friend, or you will be good for little to-morrow. As I have only been lazing about the camp for the last few days, and am now nearly well again, I can sit up better than you, and I promise you I'll keep a sharp eye yonder, and our friend there won't give us the slip while I'm on the watch.' He turned a grateful look on me and pressed my hand, but made no reply, and presently fell into a troubled doze, from which he started up now and again, but finding me always awake, he finally went off into a sound sleep that lasted till near daylight.

'Get some sleep, my friend, or you will be good for little to-morrow.'

"Two days passed, but no trace could be found of Charley Stirling. The native trackers were all at fault, the dry state of the ground at the time baffling their usually astute and unfailing cunning, and sadly we gave up all hope. Zoe remained all the time in a state of pitiable prostration and suffering; while Meyer stayed in the camp, busying himself in cleaning his arms and pegging out skins brought in by his 'pals.' An intimation had been conveyed to him from old Niemann to the effect that, for the present, he must not attempt to leave the camp, and to me, as I stayed there all day, was entrusted the duty of watching that he did not do so. Of course, as there was no sort of evidence against him, we had no excuse for making him a prisoner, and therefore, so long as he obeyed the injunction to remain in the camp, no one had reasonable cause for further interference with him.

"At the end of the second day, a runner came in with the tidings that the party we were waiting for would reach us the next day, and the following morning at daylight, Martin Stirling came to me, and asked me to come with him a short distance on his way. I followed him to the outskirts of the camp, where I found he had his horse awaiting, already saddled and loaded with a number of things as though for a journey, and taking the bridle from the post it was fastened to, he walked on in gloomy silence till we had got some distance away. Then he turned and spoke.

"'Fuller,' he said, looking me straight in the face with feverish, but keen eyes, 'I know that Niemann will do no more in search of Charley, and the camp will be moved on from here to-day or to-morrow. The other people are sure to be here to-day— perhaps in an hour or two—and will want to push on, and it would be useless to ask them to delay longer. I, however, cannot give up the search, and if you all go on I shall remain here alone till I—I—find him.' The poor fellow could hardly jerk these last words out. 'Now,' he went on, 'I want you to do something for me—two things—and I know I can rely upon you, if you promise. One is that you will do what you can to help old Schomburgk; and the other is that you will keep your eye on that murdering devil, Meyer, and—keep him for me. That's all. Will you do this for me, old man, supposing, say, you do not see anything of me for a week, or longer?'

"'Stirling,' I answered, taking his hand in mine and laying the other on his shoulder, 'I promise solemnly to do all you ask, and will carry it out to the letter—but—on one condition.'

"'What is that?' he asked moodily.

"'It is,' I replied, 'that you make me a promise in return. That you will promise me that whatever the result of your search may be, even if you get, or fancy you have found, evidence of foul play against Meyer, you will do nothing against him yourself. Think, my friend, think,' I urged, as I saw him give an impatient shrug, 'think of Margaret. I would not see you turn murderer because Meyer was one.'

"He reflected silently for some time, and at last, as I waited patiently for his answer, he looked up with decision clearly expressed in his face.

"'You are right, Fuller,' he exclaimed, 'I know you wish me well, and I should be wrong not to be guided by so kind a friend—I promise. In such a case I will leave him to you all to do as you think right and just.' And with that he mounted his horse and rode slowly away.

"Two or three hours later the people we were expecting arrived, and the camp was all bustle and excitement. Friends met, and the newcomers were soon put in possession of all that had occurred, and were talking it over one with the other. To escape joining in the general chatter I walked out a little way and sat under some trees, looking out over the veldt to see if any of the search parties were coming back, when I saw a speck in the distance that caused me to go back and fetch my field-glass, and I soon made it out to be Martin Stirling making his way slowly back. Guessing that something must have occurred to bring him back so soon, I returned and sought out old Niemann to explain the matter to him and my surmise. 'Yes,' said the old man, 'I guess you're right. Somethin's up. We'll go and meet him quietly. Bring three or four of the boys, and slip out separately so as not to be noticed.' This I did, and presently a small party of us had assembled with our horses beyond the outskirts of the encampment and were soon on our way to meet Stirling, who was still coming slowly towards us.

"I was the first to get near to him, but not till I called out did he look up. I noticed, as I got near, that he was scratched and bleeding, and that his clothes were, in places, torn into shreds, but his face was the worst part. For, as he turned towards me and looked up, I saw the most haggard, ghastly countenance I have ever looked upon in a living man; and that look has haunted me many a day since, and has mingled with my dreams. To my hurried questionings he made no reply, till the others came up, and then, as Niemann said, 'You have discovered something?' he replied, 'I have. Fetch Meyer and bring him with you to a place I will lead you to.' But not another word would he say; he seemingly sat staring straight before him and vouchsafed no further explanation. Presently Niemann turned to two of the others, and said, 'Go back; leave your horses outside, and go on foot into the camp, and tell Meyer to follow you out on his horse, and then come after us. Stand no nonsense, but say he must come, or we will return and compel him; and see that he does not give you the slip. We will ride slowly on.' This was accomplished, and before long, on looking back, we saw the three coming after us.

"We walked our horses in silence, and when the others had come up, and Stirling had convinced himself by a sharp look around, that Meyer was really there, he motioned to me, which said as plainly as words could have done, 'See that Meyer does not give us the slip'; he then started off at a canter, and we all followed. Stirling led us on till we came to the borders of the forest over yonder, where he struck into an open glade, and then began to proceed slowly again. I had dropped behind Meyer, and was watching him closely; I noticed that he became visibly more and more discomposed as he saw the route we were taking, and at length, as we entered this glade, and went more slowly, he turned white, and began to look about him. Presently, Stirling stopped and got off his horse, and as Meyer noticed this I saw him bite his lips savagely, and mutter something that was clearly not intended for a blessing.

"Turning to Niemann, Stirling then said, 'Here we must get down and hitch up the horses, and see to that man there,' pointing to Meyer. 'Do you think,' he went on, 'he looks like an innocent man? And do you think it safe to leave him in possession of the pistol he has, no doubt, got in his pocket?' As he said this, Meyer made a movement, but we were too quick for him, and his arms were seized just as he had drawn out his revolver. It was taken from him and he was made to get down, his horse was led away, and he was left standing, livid with rage and fear, in the midst of us.

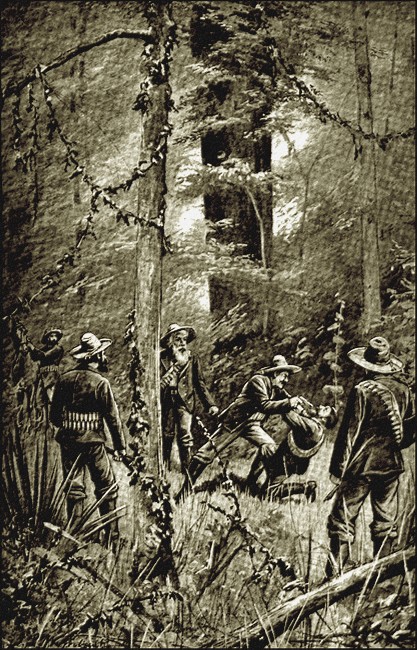

"At this juncture Stirling behaved very strangely. We all thought, of course, that he had found the body of his brother, and was going to lead us to it. Instead of that he simply stood still, leaning against his horse, and remained silent. Presently Niemann asked him what we were to do next, but Stirling only held up his hand and said 'Wait; wait and listen.' We waited, but heard nothing of note. A few cries of birds were heard, but otherwise the place was quiet and deserted. Round about, as I observed looking on the ground, a lot of loose stones were lying here and there, and I noticed in places holes as though some had been pulled up and taken away, but otherwise there was nothing to show that the spot had been recently visited by anyone. As we waited on and Stirling made no further sign, Niemann began to show signs of impatience, and upon this, Meyer managed to pluck up a little courage. Then he said, 'What's all this tom-foolery about? Can't you see the man's mad? The loss of his brother has turned his brain. He—' But just then a terrible blood- curdling cry rang out and echoed through the forest; it was followed by another, and we distinctly heard these words: 'Martin! Martin! Ah—' Then, after a moment or two of silence, 'Zoe! Zoe! My poor Zoe!' Next what seemed to be sobbing groans that died away in a choking gasp, and all was still. We looked from one to another in dismay and astonishment, when the cries rang out again, and were repeated exactly as before. One or two started forward to rush in the direction they seemed to come from, but Stirling, who had not moved, held up his hand and pointed at Meyer, who, as we turned and looked at him, was shaking and trembling all over. Stirling drew out his revolver, strode up to the tottering man, and seized his collar and shook him. 'Tell me'—he seemed to hiss the words out—'tell me what you have done with him, or I will shoot you where you stand.' Meyer fell on his knees, and pointing to a slight opening in the bushes, 'In there,' he gasped out, 'a little way inside—under—a—tree where you'll see some—loose— stones,' and as Stirling let him go and strode off to the place he had indicated, the man fell to the ground in a swoon. Stirling pushed his way in, regardless of the thorns, and two or three followed, while I and another stayed to take charge of Meyer. Presently they returned bearing the body of poor Charley Stirling! I need not tell you the state of the corpse, but Charley it was, plain enough; and putting him tenderly on one of the horses, we left the place and made our way slowly back to camp.

'Tell me what you have done with him, or I will shoot you'

"That night a sort of court was formed and Meyer was adjudged guilty of the murder, and at dawn next morning was taken out of camp and hanged; for there was no civil authority to hand him over to, and we were our own law-makers, and carried them out ourselves."

AS the old hunter finished his strange tale we who were

present and had been listening to it, gazed enquiringly at one

another, not knowing what to make of it, when after a few minutes

silence he spoke again. "During the morning," he said, "after

Meyer had been hanged, a large party went out, urged by

curiosity, and visited the place where we had found the body, and

we heard the same cries, and there we discovered what caused

them."

"What on earth could it be?" one of us burst out.

"It was a mocking-bird," Fuller answered quietly. And, turning to me he went on, "The mocking bird out here, as you will find out yourself later on, can and often does catch up what it hears, and will repeat it after only once hearing it. Therein it is different altogether from a parrot. I have wondered to myself how long afterwards that bird may have continued to wake the echoes of that wood with its startling cries when none were there to hear. If any of you care to ride out there in the morning I will show you the very place."

And next morning we made up a party, and went out with him. He showed us the spot as he had promised, and the tree under which they had found the body of the murdered man, but though we stayed long and patiently we heard nothing more of that terrible death-cry in the forest, that had been so strangely caught up, and had led to the punishment of the murderer.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.