RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

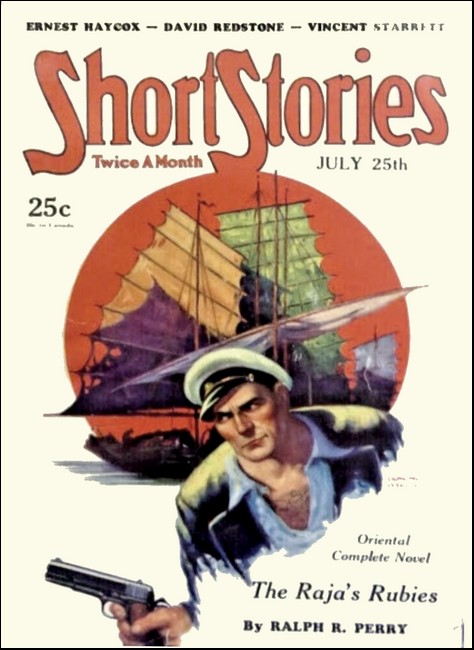

Short Stories, January 1934, with "Smoke Talk"

As this U.S. marshal put it, no western town

is able to be as black as it is painted, and he

never judged one on its published reputation.

IT was at a time of day when shadows ran well behind any sun-bound traveler that the man with the soldierly carriage and drill-straight eyes rode into the ill-famed town of Santa Rosa and put up at the stable. He had come far, this much the alert citizens of the town immediately saw. Desert dust lay like gray gunpowder on his clothes and the horse was badly jaded, as well it might be after crossing the interminable reaches of treeless, waterless land that sweltered under a copper sky. When the stranger dismounted there was a perceptible stiffness to his step.

Yet other than that, the man showed no fatigue. He lifted the saddle bags, removed the gear and led the animal out to a sparing drink. To the hostler he issued a request in a level, softly courteous voice.

"Be pleased to have you water him to his belly's full in another half hour, and give him an extra half measure of oats."

Picking up the saddle bags, he walked along the sultry street to the hotel, with a full dozen pairs of eyes watching him from odd coverts of the town. If he was aware of the scrutiny, and if he was aware of Santa Rosa's reputation for sucking a man dry before spewing him back upon the desert, he gave no sign. He walked with a straight spine and square shoulders, his gait neither hurried nor slow, a certain quiet confidence and dignity about him. He was distinctly a man at ease in a man's world. A broad, pearl-colored Stetson sat down upon a fine head; ruddy and weather-swept features were fixed to the front, seemingly interested in nothing to either side.

Yet as he turned through the hotel door, the street with its flimsy and parched buildings and its narrow alleys was indelibly printed in his mind. Crossing a gaunt lobby, he dropped his saddle bags on the counter and confronted Santa Rosa's official host—the fleshless, laconic Lafayette Lane.

Lafayette Lane had seen them come and go for twenty years. He knew men, as hotel keepers have a way of knowing men, and out of his knowledge he had built up a rough and ready classification. If his guests were dignitaries, great ranch owners, grave elders with vanity, or men he wished to flatter, he bestowed upon them the title of "colonel." Those of lesser degree, Easterners or gentlemen upon whom he liked to press his hospitality, became under his roof "majors." But when a traveler arrested Lafayette Lane's attention and instant respect, which was not often, he drew forth the prefix of "Captain." To Lane a captain meant a man of action, of tough hide and sound nerves, and above all of courage.

He weighed this new stranger with a casual glance, noting the fine suit of black, the white shirt and tie, the heavy watch-chain; noting also the even pressure of the stranger's lips and the peculiar light blue of the eyes which, he guessed, might easily hold threats under the pressure of emotion. Having caught these things in the space of a finger's snap, he swung the register and offered the pen.

"Pleased to have you under my roof, Captain."

The stranger bowed slightly and wrote "William Yount" in steady, bold strokes. Lane blotted the signature and left the counter, Yount following with his saddle bags.

Up a flight of squealing stairs and down the length of a shaded hall, the hotel man threw open a door and stepped aside, murmuring, "You'll find it the coolest room in my establishm'nt, Captain Yount. Supper's in the dinin' room at six. Trust you will refresh yo'self!"

"Obliged," said Yount and dropped his saddlebags on the bed. Lafayette Lane retreated to the lobby, each step marked by the faint protest of warping boards. Closing the door half way, Yount took off his coat, shook out the dust and hung it carefully on the back of a chair. The action exposed a shoulder-harness and gun, which he removed and also hung on the chair. Then he proceeded to pour himself a bowl of water and to wash with all the relish of a travel-stained man. At the same time, he kept one ear cocked on the hall; and when presently he caught the echo of footfalls in the lobby below he stood up, sharply attentive. Somebody spoke a quick, insistent phrase that was not answered, but save for an uneasy scuffing of boots and the scrape of a chair, there was nothing else. Yount toweled himself, replaced the shoulder holster, and slid into his coat. Lighting a stogie, he unstrapped the saddle bags and spilled a part of their contents out upon the bed. Among the articles was a letter that he took to a chair, and after settling comfortably down, began to read. He knew the message by heart, but being a man of infinite patience with details, he studied it again:

Will:

Try to get a thousand head of twos, threes and some knotty fours on the trail by the end of the month. We got to stock up this range or let good grass wither. Make certain you come close to the Colorado line for Kansas is talkin quarantine pritty strong and the damn nesters are stringing bob wire hell for breakfast.

Now legal beef is plumb good beef, Will, but rustled beef is considerable cheaper—especially such as comes wet acrost the Rio Grande. I ain't askin you to go over personal and steal Mexican cattle, which would be downright dishonest. But in case you run into any local talent which has experience thataway and could deliver you wet stock on the hoof, no questions asked—just use your judgment. You recollect the Lord says he will take care of them as shuffles for themselves.

Ned Burd.

William Yount's level eyes glimmered with a trace of humor; he chuckled as he folded the letter back into its envelope. But the chuckle and the humor alike vanished when he drew from one pocket a smaller piece of paper with the following penciled notation:

About six feet, hundred and seventy-five pounds. Black as a greaser and palavers that language good as English. Thin face, bad knife slash along left side of neck. Treacherous, scary and can't be drawn into a trap. Said to be quickest draw on the Border. Has a known record of eleven notches. Santa Rosa is the town where he hangs out. Called the Lizard. None other known.

The cigar had ceased to draw. Lighting the second notice, he used it as a torch to get his smoke drawing well, and watched the paper slowly char.

For perhaps twenty minutes he sat thus and smoked, staring at the blank wall with a remote, speculative absorption in the blue eyes. One of his hands closed with a curious gesture of finality, and he rose and crossed to the bed, replacing the letter inside a saddle-bag.

Then he did a curious thing. With a pencil he made extremely light marks on the bedspread, where the corners of the saddle bags rested, arranged the straps on the buckles carefully and stepped back to study the effect. It seemed to satisfy him, for he put on his hat and went downstairs, crossing the lobby without appearing to see the wasp-like figure of a man sitting very still in a far corner of the room.

But he was no sooner beyond the hotel porch before this man sprang out of his chair and started for the stairs. Upon his shrunken face, which was marked and pocked with the full stamp of evil, was a nervous half-grin that drew up the corners of his pale lips and put a beady malevolence in his yellow eyes. Poised on the bottom step, he turned to sweep the door by way of reassurance and then threw an impudent grunt at the silent Lafayette Lane.

"You watch fer him," he said. Then he was out of sight

Lafayette Lane sat on a stool behind the counter, with his hands folded across his stomach, and scowled into space. If he disliked this sort of prying into the affairs of his guests he kept his peace.

The barren lobby droned with the clustered flies and already the patch of harsh sunlight coming through the door and begun to shorten and slide away. The little man who had gone upstairs worked swiftly, and in five minutes hurried down.

"Clean socks, clean shirt, razor, a Bible and some extry cartridges. Some other junk—and a letter." The thin and weasel-faced snooper pursed his lips in a way that gave him an air of shrewdness. "Either he's cute, or he's simple to leave it layin' around. It tells on him. He's a cattle buyer. Or so it makes out."

Lafayette Lane broke his taciturn silence. "Some day, Wink, yo're a-goin' to get that ferret-face burned offen you."

"Yeah? Don't you like it? A-cause if yuh don't—" and he sized the hotel man up and down belligerently—"go tell Jake about it and see what fur!" He hitched up his pants and swaggered across the lobby; yet his nerves were not of the steadiest, and behind him the silence of Lafayette seemed threatening. Wink's pace accelerated. He jumped across the door sill, stared swiftly behind, and hurried off the porch.

Lafayette relapsed to a gloomy perusal of the register. "Yes sir," he soliloquized, "Wink'll get the hell burnt outa him someday. And I dunno's I'd send any flowers, either.—Yount—that's a good name. Plumb too good for Santa Rosa!"

YOUNT passed casually along the street, with the westering

sun burning against his face. Santa Rosa had not yet stirred

from its afternoon siesta, but Yount knew that the emptiness

of the walks and the dull, lethargic silence was only a

mask—like the sleepy countenance of a poker player.

Crossing the mouth of this alley and that door, he felt the

glances of hidden men; from a dozen dark angles they were

watching him. Being a bone-and-blood Westerner, he knew the

habit of cattle towns. Most of them were reserved and suspicious

of strangers. But there was more than reserve in this sweltering

row of buildings; more than aver—age hostility, too.

When he turned in at the door of a huddled brick structure labeled "Santa Rosa State Bank" he had the feeling that this inspection stalked him to the very threshold and then dropped reluctantly away as he stepped inside. Bullet marks high on the wall of the bank's single room arrested his attention. Below them and behind a stretch of grille work stood a lean old fellow in a seersucker suit who lifted a taut, measuring glance that somehow seemed to contain the anxious expectancy of disaster and the hope that it might not come. Pity swept Yount as he reached into his pocket.

"Good day," said the banker, quickly.

"Good day," was Yount's courteously soft reply. "I have here a draft for ten thousand dollars on Austin. I propose to do some business in this section, if conditions are favorable, and I'd duly appreciate your establishin' my account."

The banker accepted the draft and scanned it line by line, letter by letter. Presently he murmured, "Agreeable."

"Thank you kindly. How long will it take for the account to be open?"

"Three days."

Yount nodded, turned and thought of something else. "I suggest that you ask for considerable gold. It's my habit to pay in specie."

His attention shifted to the small table in the center of the room, upon which sat a small iron savings bank fashioned to resemble a donkey. Thrift in the shape of a child's toy.

Something loosened inside Yount; he chuckled and hefted the donkey. "I reckon," he called back, "a dollar would get one of these things?"

"That's what they're for," agreed the banker in a tired voice. "But when folks get a dollar around here, which is seldom, they bury it under the kitchen floor!"

Yount chuckled again and sauntered out. "Teachin' youngsters thrift is a sound idea," he mused. Then the blue of his remarkably level eyes was filled with a sober pensiveness. "But who is to teach the thrift of time to an old fool like me? Days come and go, and I ride on alone, siftin' into this town and out of that one. When I die, out on the desert with a bullet in my back, or maybe peacefully in a hotel bed, who will be the sadder for it? The lone trail was never meant for man. Even the animals know better."

He looked at his watch, finding the time to be past four o'clock. Habit made him turn abruptly into the saloon for his before supper drink, and when he pushed the doors aside and faced the stale, semi-darkness of the place he at last saw the brand of men who were responsible for Santa Rosa's far flung reputation of evil. The little fellow with the weasel face sat teetering in a chair over by the wall, his eyes averted and he seemed to be trying to hunch himself out of sight, like a rabbit. There were perhaps a dozen men scattered through the long room, lounging idly in the corners or seated at the tables, and upon the cheeks of every last one of them was a covert expression, as though they were waiting for some event to happen. Three or four Mexicans lay full length on the floor, their skins glistening even in this unrelieved atmosphere. Only one man, an oafish creature with a derby hat and a hang-dog air, ventured a direct glance at Yount. His vacant giggle sounded queerly through the silence. At a table a well-dressed man with slim fingers kept piling and unpiling a stack of chips. All this Yount observed as he swung to the bar, then his quick gaze was suddenly diverted by the individual who stood behind it. An apron shielded a great paunch, chubby fists lay awkwardly on the mahogany bar top, and a grotesque, beer-red visage hovered behind a screen of heavy cigar smoke. A pair of little red eyes, pale-centered and completely lacking in any appearance of kindliness, dropped upon Yount and remained there.

"Kentucky—straight," said Yount.

The bottle and glass came to him. He poured, drank and paid, feeling about him this uneasy, hostile silence. The bartender's paw swept in the piece of silver, and with a gesture that might have been habit or deliberate purpose, sent it ringing against the wood. Then he pushed it back. "On the house," said he in an abrupt, husky voice. "On Jake Wallen—which is me. You will find, Santa Rosa a peculiar town, friend."

"So I've been informed," replied Yount, quietly. "But I never judge a town on its published reputation."

"Got to see fer yo'self, uh?" muttered Jake Wallen.

"A habit of mine that I learned long ago."

"And whut." grunted the bartender in the same asthmatic rumble, "do yuh expect to find here?"

Yount turned his cigar thoughtfully. The gambler had ceased clacking his chips, the half-wit no longer giggled. Absolute silence held the place as the crowd waited for an answer. Yount's glance, as direct as a bullet, struck Jake Wallen with a cold, impersonal levelness. "Some towns are worse than their reputation, but not often. Usually I find that no town is able to be as black as it is painted."

"Depends some, I'd judge, on whether a man minded his own business or not," stated Wallen. pushing the words out beside the clenched cigar.

"I make it a habit of minding mine," drawled William Yount, and wheeled from the place. On the street he added an unspoken phrase, "I mind my own business, not statin' what that business might be." Then he swung into a barber shop and settled down to the luxury of a "boughten" shave.

He left behind him a suddenly roused saloon. Talk—swift, suppressed and calculating—crossed the smoky gloom. Wink, the snooper, had sprung out of his chair and hung his elbows over the bar.

"What you think. Jake?" he whispered.

Jake Wallen looked down on the small man with an unmoved silence, but Wink did not mind. He was too long accustomed to being bullied, kicked aside and cursed at. He muttered on. "The letter showed him as a cattle buyer."

"Mebbe—mebbe not."

Another man slid into the saloon and came straight for the counter. "He left a ten-thousand-dollar draft on Austin at the bank. Means to open an account here. What fer if not to buy beef?"

"Mebbe," grunted Jake Wallen, and his doubt seemed to soften.

"Where's he kerry his gun?" Wink wanted to know. "In his hip pocket?"

The gambler's fingers ceased playing with the chips and he broke in quickly. "Left shoulder."

"What fer a shoulder holster?" insisted Wink. "It don't sound straight."

Wallen's finger beckoned. A pair of loungers rose immediately and walked forward. "You." said the saloonkeeper, pointing to one, "never leave yore eyes offen him while he's here. Get the room next to him in the hotel. They's a nail-hole run through the center of a flower in the wall paper. See what he does tonight. If he writes anything. I want to know what it is. If he talks to himself I want to know that. See if he oils his gun and spins the cylinder like he might have need of it. Git out now.—And you," swinging on the other, "hustle over to the stable and look at his hawss and gear. I want to know where that saddle was made."

"Want me to ride to the Lizard?" queried Wink.

"That can wait." was Wallen s grunted answer. "Mebbe he buys beef—mebbe."

THE barber was a small man, stooped of chest and in need of

one of his own haircuts. He wore glasses and peered over the top

of them, giving out the air of having to stand on his toes to do

so. He was mild, talkative, professionally agreeable; but Yount,

always a hand to study people, occasionally caught him looking

out of the window with a look of infinite weariness.

"A mite of hot weather," suggested the barber, pulling the chair upright. "Come fur?!"

"A distance," assented Yount.

"Fambly man, mebbe?"

"The privilege has not been mine so far, I regret to say," answered the man in the chair.

"We-ell," reflected the barber, "some say marriage is a state o' blessedness, and some hold that it's Adam's affliction. It's all accordin' to how a feller looks at it. A married man loses some things and he gains some. But, shucks, that's the way it is with anything he does, he loses and he gains."

He put away his razor, and struck with the felicity of his own phrase, repeated it again. "Yep, he loses and he gains—which is the way o' the world."

"A man must expect his losses," gravely mused Yount. "If he gains anything at all, he should consider himself lucky."

"A downright cute way o' puttin' it," said the barber. "My first wife died young. My second was considerable high sperrited and left fer greener grass. I hold nothin' agin her, and I hope she found what she was lookin' fer. My present wife—" the barber cleared his throat and went gruffly on—"has stood a lot o' tough luck with me. That picture on the shelf—mebbe you have noticed it?"

Yount eyed the tintype and nodded. "Well," went on the barber, "you won't mebbe believe it, lookin' at a cuss like me, but that's my boy!" The phrase rolled out, round and robust and for a short interval the man's mild countenance glowed with unsuspected strength. "He's two years old. Say, the things he can spiel off with his chatterin' tongue—and the grip he's got with his hands! He's a-goin' to be a full-sized man. He's goin' to be a moose, not no runt like his dad. I shore waited a long time for that younker, but he's worth it!"

"Yo're proud of him I guess," applauded Yount.

"Me?" exclaimed the barber, and sighed vastly. "Why, say—"

Yount stood up and put on his coat. "That boy's your gain, my friend, and nothin' in the world can take it away from you."

He paid the man, strolled out, and started for the hotel. An impulse stopped him, turned him, and sent him quickly back to the bank, with a gleam of open pleasure in the direct eyes.

"That donkey is mine," said he to the banker, sliding a dollar under the grille work. "Open an account for the barber's tike."

Taking the toy bank from the table he went back to the barber shop, chuckling softly.

"My compliments to your son," said Yount, and slipped the donkey into the barber's unsuspecting palm. "And tell him a lone-travelin' old codger hopes he'll like this toy and hopes that someday he'll stand head and shoulders above a crooked, sorrowful old world."

Something happened to the barber's face. "Why—now—"he stammered. But Yount was out of the door and striding toward = the hotel, the light of pleasure already subsiding from his face.

"A long trail and a lonely one," he muttered. "And nobody the sadder when I come to the end of it."

The barber was still holding the toy, all trace of weariness gone from his cheeks, when one of Jake Wallen's henchmen walked suddenly through the door. The barber started and gripped the donkey with both hands. Fear sprang into his eyes.

"Whut'd he have to say?" growled the henchman.

"Him? Nothin' much. Said he'd come a passable distance, was a single man, and liked kids. Mighty close-mouthed, that fellow. But mighty fine—mighty fine."

"What you got there?" challenged the henchman. "Let me see that thing."

"Now hold on," protested the barber. "He give it to me for the kid. Jest a toy bank."

"Lemme see it! That gent don't make no moves around here Without Jake Wallen wantin' to know why. Pass it over."

"I tell yuh, it's for the kid!" said the barber sharply, knuckles turning white as they pressed harder around the toy. He shifted abruptly to pleading. "Now you wouldn't want to take away that little fun from my tike, would yuh? Hell, he ain't had nothin' like this—"

The henchman's arm swept around, knocked the barber back and seized the bank. "No talk outen you! Shut up! If they's anything atween you two buzzards—"

"You got no right to take that!" shouted the barber desperately. "By God, yuh ain't! Gimme it back!" But the other man, grinning sourly, had departed for the saloon.

For a time the barber's clenched fists struck spasmodically against space, and rebellion flared in his faded, ordinary features. Then it died away, leaving him sagged and weary and beaten. He passed a hand across his eyes and looked out over the housetops to the free sky.

"The boy shore would of liked that trinket," he muttered dully. "First store toy he ever woulda had. He'll never git it now though. They'll bust it up and throw it away."

Which was exactly what happened. Wallen smashed the donkey with one blow from a bungstarter, and found nothing inside. Turning the pieces over and over in his hands he shook his head at the assembled group. "Don't figger he meant anything by that. Soft hearted, I reckon. To hear that dam' barber brag yuh might think he had the only kid in the world." The wreck of the toy donkey went sailing across the room and scattered in the sawdust. "What did yuh find about the hawss?"

"Cheyenne saddle," reported the messenger who had been despatched to the stable. "Cheyenne maker's name tooled in the skirt."

Jake Wallen's swollen cheeks twitched. "Looks like he might be a cattle buyer, all right. Money in the bank, good clothes, northern rig, and a letter indicatin' he's after beef. Looks straight enough."

"How old you figger he is?" asked one of the loiterers.

"Not a day over thirty," put in the gambler whose dead eyes had studied a thousand men. "He looks older, but he isn't. Also, my judgment is that he's fast. Got to be to carry that shoulder outfit."

"Want I should ride to the Lizard?" Wink asked the saloon keeper.

"I'll tell you when I want yuh to ride! Now shut up!" snapped Wallen brutally. "Mebbe he's a cattle buyer. It looks reasonable. And by God, he'd better be! If I find anything to prove he ain't, I'll riddle him right here in the street. Did Flash put up that reward notice on the hotel wall like I told him?"

"Ahuh."

"Good enough. I want to know if Yount reads it, and how he looks at it."

WILLIAM YOUNT was at that particular moment reading the

notice. Coming up the hotel porch he had observed it tacked

right beside the door. It hadn't been there a half hour

previously, so much he was certain of, and as he tarried before

it he was also certain that it had some hidden meaning for

him—a meaning in some manner linked up with the slouching

citizen who at this moment walked slowly down the far side of

the street with an aimlessness that was only too apparent.

Yount's mind raced swiftly along the situation. To read the

notice meant to display interest; not to read it might display a

deliberate and unnatural lack of interest. So he came closer and

scanned the flaring type:

$1000 REWARD

(Paid by the Cattlemen's Association) For the capture alive or the witnessed proof of the killing of "The Lizard," known rustler, leader of an organized and desperate ring of thieves and cut-throats, and also indicted by five coroners' juries as a killer.

About six feet tall, and a hundred and seventy-five pounds. Black as a greaser and talks Mex fluently. Thin face, bad scar on neck. Treacherous, fast on draw.

Warning: This reward is not meant to induce inexperienced men to go on his trail. All parties are notified that he will kill on suspicion, offering no quarter, and that he seldom allows a fair draw. He is heavily protected in the Santa Rosa district by powerful influences. Take care.

Yount's features were gravely noncommittal. The ambling pedestrian had crossed the street and now stood on a corner of the porch, deliberately watching Yount.

A girl in a crisp gingham apron stepped out and struck a triangle vigorously, the clanging echoes beating flat and definite into the oven-like heat. Yount turned, to find her black head and her frank, clear face turned toward him with open curiosity. She was an alert, vital girl who pounded on that triangle as if she took a perverse pleasure in rousing the somnolent citizenry. Her red lips were pursed with energy as she struck a last time, but she smiled on Yount in a manner that brought the dimples to each corner of her mouth.

"Supper's ready and I hope you're hungry," she said briskly.

Yount smiled in return, attracted by this first vigorous and honest impulse he had seen in the town. But the girl's attention had shifted away toward a rider just reining in by the porch—dusty, brick-red young chap with a lean body and a fighter's face.

"H'lo Bill," said the girl, and tipped her chin. "Hurry and scrub up, and I'll have your meal waitin'." Then she retreated across the lobby and into the dining room, Yount following behind.

He took a seat midway down a long table, and helped himself from the filled platters and dishes strung along its length. Apparently this Bill had something special in the line of supper, for the girl brought out an extra dish as he hauled his long body across the room and sat down a few places away from Yount.

"They're fresh," said the girl, nodding at the plate, "and I knew you'd like them."

"Thinkin' about me now and then?" drawled the young fellow and looked up. That flashing exchange of glances told Yount all he needed to know about them. Man and woman—the old story of primitive hunger working its way with these two.

"How do you like riding for Crosskeys?"

"As good as any," muttered Bill, "and as poor as most." He said something else to her, half under his breath, and there was a short parrying of phrases that heightened the color of her face.

"Well," said she with a quick intake of breath, "at least its honest work."

"Yeah. And what's honesty worth around these parts, Helena? Thirty dollars a month."

"Still, it's honest," she repeated. "What else matters? We can wait."

"While others drag their loops and live high," he answered with a rising bitterness. Both of them seemed oblivious of Yount's being in the room. "It hurts," went on Bill, "it hurts like the devil. You and me—waitin'. A long time we been waitin'. At thirty a month, it looks like we'll wait forever. It ain't right. When I stop to figger how some of these ranch owners got their start—"

"You're tired and discouraged," said she, and her arm fell with a gentle grace on his shoulder. "The day's been hot. You don't mean that."

"How about you, swelterin' in that kitchen all day long?" retorted Bill. "Don't you suppose I think of that and—"

Once again their voices dropped to a murmuring.

"You don't mean it," said she more vigorously. "Don't say that, Bill. You're not that kind. You're honest."

"I wish I was sure of it," he grunted and shook his head.

She started to say something more, but checked herself and turned away. Jake Wallen came swinging into the dining room, with six or seven others trailing behind. The saloon keeper's wary eyes flitted across Yount and passed on. He stood beside Bill and dropped a heavy arm about the boy, speaking with a heavy friendliness.

"Long time no see, Bill. Where yuh been the last few days?" he questioned.

"A man's got to labor to make money, Jake," replied Bill.

"Mebbe—mebbe not," said the saloon man, and settled cautiously into a chair. He tucked a napkin into his collar so that it draped the broad chest like an apron, then he readied stolidly for food. "How yuh like workin' for Crosskeys?"

"Plenty to do."

"I judge," grunted Wallen. "Plenty to do, plenty of sweat, plenty of dust. Never cared much for that m'self."

Then he fell to eating with a silent voraciousness. The great jaws bulged and a greater flush spread over the beef-red checks. Other men dropped in, saying nothing, reaching for the platters without ceremony; a meal was something to be attacked and gotten over with quickly in Santa Rosa. Five minutes sufficed for some, ten minutes was as long as any of them took. Yount, dallying soberly with his food, watched them come and go until the room was almost empty. Wallen washed the coffee around his cup and downed it like a slug of whisky, stripped the napkin away and rose.

Once again that immense paw fell on Bill's shoulder. "Come around and pay my place a visit. Man's got to have a mite o' pleasure in this world." And he passed out, not appearing to notice Yount.

Yount had finished. Lighting a cigar he left the table as the girl came in from the kitchen, and he heard her talking to Bill with a strange tenseness in her voice. "Not that, Bill. Nothing's worth it. Once you get in with Wallen and—" The rest of it was indistinct to Yount as he passed out to the lobby, but he caught the name of the Lizard, whispered with perceptible dread.

Lafayette Lane was sitting on the porch, solemnly watching beyond the housetops, and Yount took the adjoining chair. The sun was down now, marked by a long, burning flare on the western horizon. Faint shadows flowed down Santa Rosa's street; a breath of air came off the desert.

"A long day and a warm one," mused Yount. "There ain't many pleasures to be had in this world, but one of the best is to sit and watch the cool of the evenin' come."

"I've passed most of my life watchin' said evenin's come." was Lafayette Lane's laconic response. "Come and go. Soon gone—and another day jest like all the rest."

"Just so," agreed Yount, and lapsed into complete silence. Twilight arrived, deepened. A light broke through the foggy panes of the saloon windows, soon followed by others. But for the most part, Santa Rosa's street lay obscure and mysterious in the thickening pools of night. Water guttered softly somewhere, and soft speech rose from doorways. A guitar's pleasant chords announced the beginning of the evening's pleasure at Jake Wallen's.

"The boys seem to be driftin' yonder for a little fun," observed Yount casually.

"They'll pay for it," muttered Lane, hardly above his breath; and then, as if regretting the remark, he rose and went inside.

As he did so Bill came out, turned uncertainly on the porch and walked toward the saloon. Yount had a moment's view of the young fellow's face, tight and bitter and puzzled. He had just disappeared inside of Wallen's when the girl hurried across the lobby, almost running, and stared toward the saloon after him. Her white hands moved up toward her throat and a sharp catch of breath, almost like a cry, escaped her. Yount thought for a moment that she meant to follow the man; but instead she went back, walking very slowly.

YOUNT inspected the glowing tip of his cigar, his mouth

pressed tight. This Bill was a fine chap, born straight, and a

fighter. But he was being pinched between the jaws of fortune as

many another good man had been pinched.

"Ordinarily," reflected Yount to himself, "he'd stick to his convictions and play an honest hand. But there's his girl. He wants to marry her, wants to take her away from that kitchen. It hurts him to see her there. Bein' crooked looks like an easy way of fixin' everything up. And there's Wallen, dangling bait right in front of the lad's nose. Easy money, no harm done except to a few rich ranchers or to the Mexicans who don't count—that's what Wallen's tellin' him."

He rose on impulse and went for the saloon, feeling himself flanked on the far side by a watcher.

"It's simple business to be honest when there ain't any reason to be otherwise," he added, grimly, "but the boy's got a hard problem. He's hurt, he's desperate; and Wallen's bait looks good. Damn that man!"

The saloon was filling, the poker games were in full tilt, and over by a roulette table a man called out a number. Bill was standing there, watching the racing ball and Yount closed idly in. Perhaps it was impulse again, perhaps not, that caused Yount to buy a stack of chips; but he had seen a faint glance of wistfulness on the face of the hard-pressed youth, and as Yount placed a nibbling bet here and there on the board, he debated over an idea that came into his head.

"I sure feel in the humor to bust that contraption tonight," drawled Bill to the group in general. "I got a hunch it's my meat."

"Try it," boomed Wallen, who had come up from the bar.

"No," said Bill with sudden stubbornness. "I need my money for other things."

Yount had lost three bets in a row. Suddenly he shoved the whole of his stack in front of Bill. "I can't catch that ball tonight," he said affably, "but I believe in backin' a man with a hunch. Here's your grubstake. Play it."

Young Bill turned a straight and sober glance toward Yount. "That's kindly," he observed, "but I may be talkin' through my hat and lose your pile."

"When I gamble I always expect to lose," replied Yount, grinning. "You got the fever, so hop to."

"Here goes," grunted Bill and took the stack. Yount rolled his cigar around and turned to the bar for a drink.

Jake Wallen was beside him, the pale-centered eyes boring in. "Santy Claus, ain't you?" he said.

"I do things that please me," observed Yount and drank his slug. "Any objections to that?"

"None—so far." Wallen lifted a finger to the barman. A box of cigars came across. "Fill yore pocket," he invited Yount. "On the house—on Jake Wallen, which is me."

"Thanks, kindly."

"Santa Rosa," opined Wallen, "is a peculiar town, friend. Santa Rosa likes to stew in its own juice. Santa Rosa tends to its own affairs and tolerates no outside interference. Mebbe," and the saloon man's gross cheeks stiffened, "it will interest yuh to know there ain't ever been a law officer inside Santa Rosa for five years."

"I would say," mused Yount, "the law officers was discreet."

"Some have tried to get in," droned Wallen. "Them fellows never repeated the same fatal mistake. Santa Rosa takes care of itself."

"Santa Rosa—which is Jake Wallen," said Yount.

"I see you are a man o' judgment. Have another drink."

Yount bowed and tossed down the liquor. Very gravely he wiped his lips and turned for the door. "Believe I'll turn in." And then, as an apparent and casual afterthought, he added, "I expect to ride out and see the country tomorrow."

He went back to his room and settled down in a chair. From his pocket he drew a pair of steel-rimmed glasses; out of the saddlebags he took a Bible scarred with travel and usage. And for a half hour this quiet man with the carriage of a cavalry officer bowed his head over the fine print. Then he went to bed.

Five minutes later, Wallen's henchman left the adjoining room and hurried back to the saloon to make his report. "He didn't talk to himself, didn't write and didn't make but one funny play," said the man to Wallen.

"What was that?" demanded Wallen.

"He read a Bible fer half an hour."

Wallen chewed at the end of his cigar a long while. "He's a mite soft thataway. He staked Bill at roulette an' he give the barber a toy donkey fer his kid. I reckon he buys beef. Tomorrow he aims to ride out and have a look. He give me notice, which means he's nobody's fool, and that he knows dam' well who can put him in touch with said beef. Wink!"

The snooper hurried over.

"Ride to the Lizard," grunted Wallen. "Say a man'll be along the road tomorra."

IT was after breakfast, and Yount was in the stable saddling when young Bill walked through the wide driveway with a small and cheerful grin on his lean cheeks. He punched back the brim of his hat and brought a roll of bills from his pocket.

"I was lookin' for you," he drawled. "I busted that outfit last night. Won a hundred dollars. Here's your stake and the extra fifty. I'm han'somely obliged, and if there's anything I can ever do for you. Bill Bent's my name; and I'll be around Santa Rosa durin' the next few days."

Yount accepted the money. "Bein' flush, you figger Crosskeys don't need your services any more, uh?"

"No-o," reflected Bill, "I guess I'll tag along with the outfit for a spell. Leastwise, until I find a place where money grows on bushes."

Yount swung to the saddle. "There may be more profit left for you in that roulette rig," he suggested.

"Not for me," stated Bill bluntly. "I ain't foolish and I'm hangin' on to every doggone nickel. Say, I'd cut a man's throat for a dollar! But I'm under obligation to you, friend."

"None whatsoever," said Yount. "I always like to back a good man." And with that he rode out of Santa Rosa, eastward into the fresh glare of the morning's sun.

The town was dead, and excepting young Bill, who strolled toward the hotel, nobody appeared on the street. But Yount knew that his departure was observed and he also knew, before he had gone far, that Wallen still kept him covered. Yonder to the left a mile or more, a horseman cut out of an arroyo and jogged parallel to the trail. In time this individual veered away, and presently he dipped from sight. Yount's blue eyes narrowed.

"Crookedness," he murmured. "Deception, evil, lust and violence. Wallen's been teachin' 'em that for ten years. Warpin' everybody to his own uses. Them that don't warp either die or depart. And now, needin' fresh hands, he works on this Bill Bent, caterin' to him, danglin' bait, lettin' him win a hundred dollars from a crooked rig just to make the lad feel good. It's like a plague on the land."

Off to the southwest lay a puff of dust against the horizon, low and travelling. Yount studied it for a half hour and nodded slowly.

"Two can dangle bait. I dangled mine in front of Wallen and over there comes an answer. My bet is that it's the Lizard. Another cat's paw. Maybe this Lizard thinks he's the big noise around Santa Rosa, maybe he thinks he runs the district. But he don't. Wallen does. It's Wallen we've got to buck before the sun goes down this night."

Momentarily, the rider off to the left popped up to view, cantered a few hundred yards and again vanished. Yount rode straight along the trail, waiting for his patient plans to mature. Santa Rosa was a dim outline behind, huddling miserably beneath the fury of a brazen, pitiless sun. Ahead of him many miles stretched a barrier of low hills, promising a shelter that didn't exist in their barren slopes; and to the right the dust ball gathered and grew. It passed rapidly from south to east and then was directly to Yount's front, completely subsiding. Three men, standing across the trail and waiting for him. In time he was near enough to see that the center figure rose considerably above the others and over the narrowing interval he had his first sight of the Lizard.

HE knew the man immediately from the broadcast description.

A floppy hat, held by a chin-strap, shaded features that were

almost olive; and the first detail Yount picked up was the

jagged angry scar that cut a half circle around the base of

the man's throat. He was an impatient creature, this Lizard,

moving continually in the saddle, and the horse fiddling beneath

him. There was a cruel cast to lip and flaring nostril, and

when Yount reined in a few yards distant he saw dull and muddy

eyes lowering at him. The Lizard was a purely animal type,

without imagination and without the capacity to feel remorse.

Undoubtedly a terror, a vicious, unbridled killer. But only

that. The Lizard possessed but a fragment of Jake Wallen's

brain.

"Good day," said Yount, forgetting the two others after one glance.

"I hear you got business in the country," grunted the Lizard, too impatient to dally.

"Some," admitted Yount.

"Beef's what you want?" pressed the Lizard.

"That's my business."

"No questions asked. Beef on the hoof. Delivered any place within twenty miles o' Santa Rosa. Cash paid over Wallen's bar, right after yore riders take the stuff."

"No questions asked," assented Yount, "providin' it's beef from across the river. Any animal from the American side has got to have a vent brand and a bill of sale. I'm not takin' rustled Texas cattle. Don't want any trouble from the authorities. Square deal. Immaterial to me how you get it. If it's rustled from Mexico, all right. If it comes from this side it's got to be legal."

"I'll take care o' that," was the Lizard's surly retort. "What price?"

"Depends on the stuff you bring me. When I see it, I'll dicker."

"Fair enough. Three nights from now, three miles north of this exact spot."

"Four nights," qualified Yount. "I've got to collect a trail crew. And not around here. I'll take over your stuff twenty miles north of the point where this trail hits the base of those mountains yonder."

"By God, yo're particular!" exclaimed the Lizard.

"You bet I am. This mess of cattle goes on a long drive, and I don't propose to start too close to the border line. Mexicans have a habit of strikin' back, you know."

"I agree to it," said the Lizard, and seemed to consider the interview finished.

His grip on the reins tightened, and he was about to swing off, when Yount suddenly stopped him.

"Wait a minute, friend. I don't know you."

"The hell yuh don't!" growled the Lizard. "Yuh know exactly who I am. Everybody knows who I am!"

"Oh, I've heard about you, and I've read a general description of you; but I don't propose to go off half-cocked on this deal. There's tricks to all trades. You may be only the livin' image of the Lizard for all I know. Maybe framin' me for a fine trap."

"So? Now what you want, my birth certificate? I'd flash that for yuh if I knowed where I was born an' who my paw was—which I don't. I'm gettin' some aggravated with this palaver."

"Nevertheless," Yount insisted, "I'm a cautious man. I know Wallen, but I don't know you. Wallen's word is ample with me. If he says you're the man I'm lookin' for, well and good."

He felt the flare and impact of the outlaw's eyes. This moment held danger. Suspicion raced across the man's face, and his thin lips pressed to a mere line. The animal was cropping out in him, the predatory instinct to draw away and strike without asking further questions. Yount held himself absolutely still, hands folded across the pommel, meeting the Lizard's half-lidded stare evenly. Of a sudden, the outlaw shrugged his shoulders.

"All right. I'll tend to that. Be in Santa Rosa sometime this afternoon." And grunting at the other two, he whirled and galloped back to the southeast.

Yount reined around and walked his pony homeward, drawing a great sigh.

"So far, so good. Cards are fallin' right. All a man can do in a case like this is use the best of his judgment. Right up to the showdown. And when the showdown comes and the time for judgment is done with, there's nothing left but luck and the help of God. Which I will need before shadows fall tonight!"

Between his position and the distant Santa Rosa, there was the abrupt appearance of a moving object. Yount looked at his watch, fine lines of thought springing up at the corners of his eyes.

"That's the eleven o'clock stage, which I figured on," he said to himself. "It'll be in Irique at one—just time enough. And now, if things fall right—"

He threw away the half smoked portion of his cigar and took another. When the stage had become visible he pulled from his pocket an inch-long section of white chalk and adjusted it between thumb and forefinger of his right hand. A flash of excitement crossed the steady cheeks. "If there's passengers, this is going to be difficult—" Then he drew slightly off the road, waited until the rapidly-travelling team was well down upon him, and lifted an arm in signal. The driver, sitting alone on the seat, hauled back and stepped on the brake-block, and the light carry-all skewed across the shifting sand.

"What the hell?" challenged the driver, reaching for his plug tobacco.

"Never like to stop a stage," apologized Yount affably. He drew beside the outfit and rested his right hand against the seat panel, in the manner of a man wishing to ease his weight. "A gent's motives might get misjudged and start the lead a-flyin'. But I ain't got a match to my name, and it's a long ride without a smoke."

"Uhuh," grunted the driver and searched himself. "Yeah, here's a couple. Hardly need a match on a day sech as this be. Could scorch asbestos up here where I'm a-sittin'."

Yount accepted the matches politely, and started to say something else; but the driver had gathered up the ribbons and kicked off the brake. "Got no time to palaver," said he. "I'm due at Irique in one hour and thirty minutes."

The stage careened away, bearing upon one seat panel the lightly written "Y" that Yount had inscribed while his hand rested there. He tossed the chalk behind a clump of sage and proceeded at the same idle gait.

"That's done, and there ain't much left now but to wait—which is the hardest of all."

DINNER was over when he reached Santa Rosa and put up his

horse. The hotel man, breaking a rule, offered to put something

on the table for him, but Yount declined.

"A man's got to work to eat, and I'm a little too heated for provender. What I need is somethin' cold out of a bottle."

"Ridin' in the full o' the sun would natcherlly incline a man to heat," murmured Lafayette Lane. "Folks around here most usually do their ridin' at night."

"Might be a wise idea," drawled Yount.

"That's according," was the hotel man's cryptic answer, and then he busied himself at the key rack, once more giving the impression that he thought he had spoken too freely.

Yount went up to wash, and then headed for the saloon. There, Jack Wallen, playing solitaire at a table, rose and circled the bar.

"Inclined to be warm," he suggested.

"May turn out that way."

"Have a drink on the house—on old Jake Wallen." And the saloon man's meaty face bent forward while Yount took his portion and downed it.

"For a mature man," reflected Wallen, "you drink like a sparrow. Have another."

"Thanks, no. Fatal for a Northern fellow to drink heavy down here in the south."

All at once Wallen was aflame with renewed suspicion. "Northern, huh? Since when has northern folks took to drawlin' their words like you do?"

"The North," said Yount calmly, "was settled by gentlemen from the South. I was born in Louisiana, myself. But when we fellers from the south winter five-six seasons up there, we call ourselves Northerners. I'm proud to know my drawl remains. I'd hate to lose it."

Wallen poured himself a jot and grimly drank. "By God, man, you had me ready to call the dogs jest then! I'm a man that believes nothin'. Not even if it's so. I mistrust you, and I have ever since yuh set foot in this town. And I'll continue to do same after yo're gone. But I'll play yore game—until I change my mind."

"I don't blame you," reflected Yount, lighting another cigar. The blue eyes fixed themselves critically on the fingers holding the match, as if watching for a sign of unsteadiness. "Not at all. I'm a hard fellow to satisfy, myself. For instance—I met a gentleman on the trail this mornin'."

"Thought you might," rumbled Wallen. "It was wise of yuh to mention yore little pasear to me."

"I know who runs this district," agreed Yount.

"You bet. Me—old Jake Wallen. But that fella you was speaking of?"

"He asked some questions concernin' beef," drawled Yount. "Seemed interested. But maybe he's a gent known as the Lizard, and maybe he ain't. I am taking no chances."

"What about it?" demanded Wallen, openly puzzled.

"We made a dicker, as far as beef's concerned," proceeded Yount idly. "But I'm not dealin' with him until you point him out to me and personally name him. It's not my habit to throw money on strangers. I have cut my eye teeth on skin games."

"Meanin' I got to introduce you to the Lizard?"

"Just so," approved Yount "And I believe I will go seat myself somewhere and wait for a breath of air."

He turned, deliberately presenting his back to the saloon man, and strolled over the room. Passing through the doors, he had a moment's side glance of Wallen's face set toward him, still a little puzzled; for all the creature's fleshiness he was strangely cat-like, forever waiting and ready to spring.

In the street, Yount found sweat beading up on his forehead, not from heat but from the highly keyed situation he had just passed through. On the hotel porch he took to a chair, tilting it against the wall and sighing vastly.

"And that's done," he told himself. "Had to stir his suspicions again, which was bad but couldn't be helped. Let him try to think it out. He can't find a flimsy point where he might poke his pryin' finger through and nail me. He wants the money I can throw him for that beef, and it'll sway his ordinary judgment, which would be to stop debatin' and let the hounds loose. He'll play my game, the Lord willin', until sundown. After that—"

Sundown. To this calm, grave man who sat so quietly on the porch it seemed an eternity removed. Waiting was always the hardest. The heat streamed through Santa Rosa in thickening waves; there was a shimmering cushion of it along the tops of the buildings, and occasionally some board or joint of the hotel cracked like a whip. One hour, and then another, the bake-oven temperature intensifying as the porous earth was at last saturated with the bombarding rays of sun and began sending them back. Two o'clock. Three; and then four. After that time seemed to halt, and all things were held in a droning suspense. It appeared to Yount that even the town's sullen vigilance had been smothered. Nobody moved in the open.

He rose and went in to draw himself a drink of flat and tepid water from the lobby jar. Lafayette Lane was stretched full length on a bench, in a comatose state that was neither sleeping nor waking. Going on back into the dining room, he found the girl sitting at the long table, head pillowed forward on her arms. She lifted it swiftly and Yount saw that she had been recently crying, a fact that both embarrassed and saddened him.

"I wonder, ma'm, if you can get me a lemon so I can strip it into that water out front?"

"I'll make you a lemonade in the kitchen. Sit down."

"Now don't bother about that—"

"No bother," said she cheerfully, and disappeared.

Yount took a seat. If anything, it was a degree cooler in here, and for that he was grateful.

"But it's hard work for her," he told himself. "All day long, workin' like a beaver. Can't blame this Bill for bein' upset. It's easy to talk about honesty—sometimes it's hard to practise it."

The girl returned with his lemonade and watched him drink.

"Bill told me about your grubstaking him last night," said she, presently. "I want to thank you—for being kind. People around here are not always kind."

"Hope he uses the money profitably."

"He—he gave it to me to save," she murmured.

"Level head on him, that boy," applauded Yount.

"Yes." There was a sharp intake of breath. "When they leave him alone!"

She said something else, but suddenly Yount's ears were tuned to a sound on the street. He sat as still as carved marble, hearing men pass into town. That would be the Lizard and his followers arriving. Very carefully, he deposited the glass on the table.

"I wish we were in any other town in the world but this one!" she was saying. "I know what—what they are trying to get Bill to do. He wouldn't listen to them if it wasn't for thinking of me."

"Folks have got to fight it out," mused Yount, and a grave, fatherly tone came into his words. "The world is full of fightin' and sorrow. We can't help that.—But don't you worry. This will wash out. What's right is right and will prevail, though it takes a thousand years. Don't you worry."

"A thousand years won't help Bill, Mr. Yount!"

He had risen and turned to the lobby. "Maybe sooner," was his soft murmur.

Instead of going to the porch, he sat in the lobby, a dry cigar clenched between his teeth. Through a side window he saw three horses nosed against the saloon hitching rack, and three men at that moment going into the place. A perceptible line of worry creased Yount's brow.

"Where's the rest of his bunch?" he asked himself. "Waitin' outside o' town, or left behind?"

If the others were waiting somewhere beyond the end of the straggling street, he knew his chances were desperately slim. In any event, the showdown was not far off; and at the thought of it the pressure of his jaws settled more harshly against the cigar and there was a flare of deeper blue in the drill-straight eyes. Showdown, and the swirling smash and violence of guns aflame! He saw Wink, the snooper, pop out of the saloon and come rapidly toward the hotel. Presently the man stood in the doorway and puckered his face significantly.

"Yuh will find somethin' o' interest at Wallen's," he muttered and veered away. Lafayette Lane rose up from the bench.

"What the hell was that?" he grunted.

"Messenger from the powers that be," drawled Yount.

Lane walked to the water jar, drank, and went behind the counter. When Yount finally rose and aimed for the street, Lane's curiously metallic reply followed him.

"Don't take no wooden money!"

WHEN Yount arrived at the saloon, a sort of sluggish liveliness animated the stale atmosphere. Wallen was behind the bar, draped against it. The Lizard and his two followers were drinking as though possessed with an unquenchable thirst. The same slack and sullen characters sat at the tables, doing nothing, saying nothing. It was as though they had never moved from their places since Yount had ridden into town. He walked forward.

"This the man?" asked Wallen, stabbing a thumb at the Lizard.

"That's him."

"Then he's the fellow you want," stated Wallen heavily.

"Damnation," growled the Lizard. "Here I makes the blisterin' trip acrost country jest for this piece of foolishness. Who in the hell did you think I was? I'm the Lizard!"

"Then it's settled," drawled Yount. "My mind's satisfied. Sorry for the extra trip, but there's considerable money in it for all of us."

"Make your arrangements now," ordered Wallen.

"Already made," broke in the Lizard. "The boys are headed south this minute. I sent 'em ahead, and I'll catch up in the cool of the evenin'."

"Better get on the trail," said Wallen, scowling.

"I'm eatin' a hotel meal tonight. I'm tired of beans and canned tomatoes. It ain't you, Wallen, that has to go out and eat dust. Let me do this my own way. I—"

There was a sudden clatter out in the street.

"What's that?" snapped Wallen, and threw his big body around the end of the bar with an astonishing speed. His move roused the whole place to an electric tensity. Men followed him through the doors, Yount idling after, as grave as a priest at prayer. A flat bed wagon with a platform built upon it, came rattling through the street, two men in it. The driver was young and sad-faced, and worthy of no particular notice. But the other, draped head and foot in a flowing linen dust coat, made a striking figure. He wore a thirty dollar hat edged with snake-skin, and diamonds flashed on his fingers. Beneath the shade of the hat were features thin and haughty, a Buffalo Bill goatee, and raking, glittering eyes. The stamp of his profession was all over him, and if it had not been, the lettering along the wagon box would have soon established it:

YELLOWSTONE JACK—WORLD'S GREATEST NATURAL HEALER

AND BANJO ARTIST. ORIGINAL DISCOVERER OF THE INDIAN

SAGA HERB, RESTORER OF THE HUMAN RACE, BOON TO

SUFFERING MANKIND, INFALLIBLE CURE FOR EVERY ORGANIC

AILMENT KNOWN. HERE TONIGHT—TONIGHT—TONIGHT!!!

The wagon veered in until it stood before the saloon; the driver halted with a slash of his whip, looking neither to right nor left. Yellowstone Jack rose in his seat and bowed with a wide sweep of his hat.

"Gentlemen, I bid you good day," he said in a loud voice. "I have come to entertain your town, to heal it and to leave it rejoicing. Tonight, the gallant little city of Santa Rosa shall be given a full and continuous program, educational, entertaining, diverting and valuable. Tonight—at seven, at seven, at seven!"

Then, having finished his lecture, he turned to the driver. "Get those horses into the stable and be careful about watering them. Don't sit there and dream."

The driver obeyed meekly. Yellowstone Jack dropped from the seat, and went around to the back end of the wagon where two doors, padlocked, let into the compartment between wagon bed and platform top. Evidently it was the medicine man's supply chest and catch-all, for after unlocking it he drew out a banjo, a valise, a torch stand and a box of cigars. Snapping the padlock again, he laid all these things down upon the platform and turned to the group.

"By gad, I never toured this circuit in such hot weather before! Gentlemen, join me in a drink."

Wallen had not moved an inch from his position against the outer saloon wall. His pale, probing eyes kept striking at Yellowstone Jack, at the driver, at the wagon and its details; and he had his head canted as if better to catch some betraying sound in the medicine man's extravagant speech. Yount, apparently interested in the new arrival, saw how the saloonman's great body stiffened and his repulsive jaws ground together. Yount felt that morosely suspicious inspection turned on him and as he felt it, he chuckled and spoke to the Lizard.

"It's been some time since I last saw the old low pitch game. Guess it is one way of makin' a living, but this sun's pretty hot to be standin' under. Believe I'll hunt shade."

Yellowstone Jack entered the saloon, drawing the crowd with him. Wallen ducked his head at Wink, saying, "You git behind the bar and serve up. I'm goin' for a shave."

YOUNT'S ever tightening nerves relaxed a trifle as he saw the

saloon man swing into the barber shop. The game was being played

out, the cards falling in due turn. It would only be a few

minutes now, but the weight of the world seemed to press down

upon them. He strolled toward the hotel again, catching sight

of Wallen sinking into the barber's chair as he passed by. On

the porch he hesitated, seeming to debate with himself. The sun

had tipped well to the west, and according to his watch it was

five-thirty.

Lafayette Lane appeared on the porch to look at the medicine man's wagon, and be suddenly grew rigid at sight of Yount's expression. The grave stranger was staring at him, jowls like iron and a deep blue flame burning out of his eyes. The hotel man had seen that expression before in his long life and he knew what it meant. It was the mark and signal of death—it warned of an instinct to kill, rising up like a storm, beating back every doubt, every cautious hope for life, every weakness. Whatever Lafayette Lane's original ideas had been concerning his guest, he comprehended the truth now. It could not be mistaken; and so, being wise, he let his hands stay beside him and half in a whisper declared himself.

"I'm out o' this, captain. Neither fer yuh nor against yuh. Consider this door empty and consider that nobody will shoot yuh from this direction. God be with yuh, but I'm afraid yo're lost!"

Yount nodded and slowly pivoted on his heels, all muscles like woven wire and a cold stream pouring down his spine, blocking his nerves. The street stretched in front of him. Alley mouth, door and window all met his questing eyes. Santa Rosa was before him and nothing but the hotel and the open desert behind. That way he was safe, unless some unsuspected henchman of Wallen's lay hidden in the vacant house across the street. But he was as safe as he ever would be, as safe as any man could be who in another swing of the pendulum would be looking at death. All action would be along the narrow strip bounded by the stores, the stable, the saloon, the bank.

A man on a horse turned around the bank at the far end of the street, for an instant upsetting all Yount's fixed ideas. Young Bill Bent's lean face looked down the interval, then horse and man cut diagonally across to the stable and disappeared inside.

"Keep out of this, you young fool!" thought Yount, and then took two steps forward on the porch.

The driver of the medicine wagon came from the stable and stopped to roll a cigarette. Yount's arm rose a trifle and the palm of his hand made a slight pushing gesture. The driver casually turned until he had his back to the stable wall and commanded the distant angle of the street.

He licked his cigarette thoughtfully, head bobbing. The hotel keeper, still posted in the doorway, breathed with difficulty.

Light steps tapped across the lobby, and the girl's voice rose, to be cut gruffly short by Lane's muttered, "Stay back! Hell's goin' to open up!"

Then Yount had gone down the porch steps and was standing there; the Lizard was coming from the saloon alone, coming in the direction of the hotel.

Yellowstone Jack stepped out directly after and strode to his wagon. He paused by the rear of the vehicle, removing the linen duster and rolling it into a bundle. The goatee lifted, and in that single instant he stared directly at Yount. Something passed between. Yellowstone Jack unlocked the doors of the wagon compartment and held them half open, still dallying. He seemed to be waiting for something; and the driver by the stable tossed away his cigarette with a short, nervous gesture.

The Lizard had paused to look into the barber shop, and Lafayette Lane gripped the sill of the hotel door and groaned, "Good God!"

Yount wheeled deliberately, like a soldier on the parade ground, and left the board walk, placing himself nearer the center of the dusty thoroughfare. The Lizard started on, and then, seeing Yount in the full of the sun, stopped again with a sudden jerk of his black cheeks.

At that moment Yount's level tones cut across the arid drone of Santa Rosa; laconic, without emotion.

"In the name of Texas, I want you!"

In the long hours of reflection by trail fire and lamp light, Yount had pictured this scene as it now came to pass. There was no doubt in his mind as to what answer either Santa Rosa or the Lizard would make to him. Compromise or surrender—never. Yet even now, with no hope of peace, he was poised motionless, both palms gripping the coat lapels and pulling them away from his chest. By the saloon front Yellowstone Jack flung open the little doors of the wagon's end and whirled aside, sweeping a gun from his pocket at the very moment a pair of men slid from the wagon compartment, ranged beside him, and lifted their weapons against the entrance to Wallen's place.

The Lizard felt, rather than saw, what happened behind. His swart face shifted grotesquely, the mark of the beast was upon him; he swayed, cursed with all the pent up and accumulated savagery of an unbridled career, and he sent his arm streaking for the gun at his hip. Yount, standing like a statue in the shifting sand, slid his palm across his chest and down to his left armpit. The blast of bullets shuddered through Santa Rosa; the Lizard rocked on his boot-heels, his muddy orbs opening wide in that devastating fright which comes to a man who suddenly realizes that his life is pulsing away. He looked down at the gun, desperately trying to lift the sagging muzzle, trying to force the numbing fingers to move again; and thus for an interval he remained stupidly quiescent. The high scream of a woman came knife-like out of the hotel; and in instant response, it seemed, young Bill Bent threw himself from the mouth of the stable, to be stopped in his tracks by the sad-eyed driver of the medicine wagon. Then the Lizard, trembling at every joint, fell to the sidewalk. He turned his head to obey a last primitive instinct; and so, staring at Yount, he died there in the sullen heat.

THE saloon was a-riot with trampling men. Yellowstone Jack

and his partners opened up, the triple roar rocketing madly into

the oppressive afternoon, slugs crackling through the tinder dry

boards, shattering the windows, ripping along the saloon floor.

Inside the saloon a man shrilled his agony; doors slammed at the

back, and Yount, watching and listening for every shift of this

mad tide, pivoted again and faced an alley at exactly the moment

when a Wallen partisan came into it, headlong and awkward. The

fellow saw Yount, clawed at his waist, and stumbled to a stop,

never even lifting his revolver.

Yount's bullet sent him down squirming. Others behind him flinched away from the alley; one man crossed its rear mouth in a single hurdle and gained the protection of the hotel. Immediately, Yount retreated to protect his back, at the same time sending a sharp command over to the sad-eyed driver by the stable.

"Dewey, never mind that boy! He's all right! Watch the far end of the street—by the bank! They're comin' around." Swinging, he waited for the fellow who had gone behind the hotel. A question kept drumming on his mind: what had happened to Wallen—what was going on in the barbershop just now? Wallen was the heart and brains and soul of this evil town, a shifty enemy, a man of unexpected action.

Yount threw himself forward and raked the corner of the hotel, ran on and came upon Wink, the snooper, whose frame sagged against the side wall of the building, blood filling one sleeve.

"Done—done," gasped Wink. "I done shot my bolt. Lemme alone!"

Yount seized the fellow's gun and galloped back to the center of the street.

"What's happened to Wallen?" he muttered. But he checked the impulse to close in and find out. This was his proper place for a few more heavy moments—his point of observation. The outlaw crew was splitting into fragments, and he dared not leave this flank unprotected while his three partners blocked the saloon.

Dewey, the sad-eyed driver, sprang into rapid action, shaving the bank corners with a fast fire. Just behind and above him a second story window pane shattered and a rifle barrel bore down.

Yount cried, "Watch out!" and lifted his revolver, but at this juncture young Bill Bent ran behind Dewey and poured the window full of lead. The rifle fell on through the sash and struck the ground. Bill Bent emitted a high rebel yell and ran straight for the bank, Dewey breaking into a pumping stride and following. The focus of this hot battle had abruptly shifted to the far end of town. Yount, feeling the encounter slacken, jumped forward and motioned to Yellowstone Jack.

"Come with me!" he yelled. "You two boys stay planted."

He threw his body into the saloon's riddled doors, spending the last shot out of his original revolver as he did so. But Wallen's was the tenement of only two people now, one silent figure under a poker table and a cowering Mexican whose arms stretched above him. Yellowstone Jack ran over to search the Mexican, while Yount bent down and retrieved a fallen gun. He snapped the cylinder open, found four cartridges left in it, and hurried straight on to an open back door. Yellowstone Jack warned him crisply.

"Watch out there, Bill! Yo're takin' too damn many chances! Wait for me!"

Yount made a broad jump through the door. To the left was nothing. To the right—in the direction of the bank—a group huddled against a wall and fired spasmodically through an alley, replying to the fire of young Bill Bent and Dewey the ex-driver. Evidently these henchmen of Wallen's had figured to cut around the bank and enfilade the street, but the raking lead from beyond had halted their advance.

"Now we've got them!" said Yount very softly. "I'll offer them a chance." And he lifted a sharp, chilling command. "Pitch up—hands high! You're boxed! Flatten out right where you stand, or we'll riddle you! Pitch up!"

Bill Bent's rebel yell sailed over the bank exultantly. The Santa Rosa adherent started to swing back, but there was confusion among them. The will to fight had peen pinched out by the swiftness and competence of Yount's attack. Hands rose tentatively, and then the cool, tuneless voice of Wallen's gambler, carried down to Yount.

"You win, friend. We're layin' down bur cards."

"Drop all guns where you stand," ordered Yount, together with Yellowstone Jack, closing in upon them. "Good enough. Crooked face, don't get married to that weapon—drop it! Now file through the alley to the street and meet those boys that want to see you so bad. Dewey—hold your shots, they're comin!"

He pushed the party into the street, and swung them on until they reached the front of the saloon. There, under the survey of all Yount's men, Wallen's motley band stood morosely.

"There's more of you some place," challenged Yount. "I don't propose to go look for 'em, and I don't propose to be potted from any windows. I want a roundup. You there, card player, sing out and call 'em in! Where's Wallen?"

The barber's voice issued thinly from his shop. "Come here and git him! I'm about to cut his dam' throat."

Yount ran over and ducked into the place, to find a scene such as Santa Rosa had never before witnessed and probably never would again. Wallen was stretched full length in the barber's chair, his face half lathered and half shaven. His eyes were closed, and the meaty cheeks drained of ordinary color. The barber stood over him, with the edge of his razor resting like a feather against Wallen's throat.

"Take him offen me," whispered Wallen, not daring to move a muscle.

The barber's nerves were about ready to jangle on him. He had made his great effort, had summoned all the doubtful courage in him to do this one chore. And now, shaking like a leaf, he pulled the razor away and let Yount marshal Wallen out of the chair. The barber tried to close the razor but he came so near cutting himself with it that he dropped it to the floor and steadied his body against the chair.

"When I heard you challenge the Lizard," he murmured weakly, "I knowed then what was up. I figgered yuh didn't have a Chinaman's chance, and I said to myself, 'he's a dead man unless he gets help.' So I jest dropped the edge o' my blade on Wallen's neck and kept him out of the play."

"I draw the line on steel," said Wallen, rubbing his Adam's apple. "Yuh dam' near sliced my head off. This is one bad day for you! I'll hunt you down like a rabbit!"

"I had oughta done it," said the barber as though talking to himself. "I had oughta cut him, after he took that toy bank away from me. That was fer my kid."

Yount motioned for Wallen to turn. He slipped the saloon keeper's gun free and threw it on the floor.

"Go out and join the prayer circle," he ordered. In the street again, he found the crowd increased. Lining them all against the saloon front, he called for young Bill Bent to help him. "I am taking Wallen and all men associated with Wallen back to Irique with me. There's warrants for most of 'em waiting there. You pick the sheep from the goats—and if there's anybody that ought to be here that you don't see, tell me and I'll rip this town apart with a crowbar."

"You're leavin' it to me to pass judgment?" asked young Bill doubtfully.

"I am. You took a hand, now play it."

"All right," agreed Bill and pointed his fingers along the line. "You—and you—get back to your chores. You—"

YOUNT went down to the bank. The gentleman of the seersucker

suit stood behind his grille with a sawed-off shotgun pointed on

the door and a haggard look on his gray face.

"Put it aside," said Yount, and saw the sweep of relief come over the man's countenance. "About that ten-thousand-dollar draft on Austin. Forget it. It was a part of my plan to convince Wallen that I was a cattle buyer."

"You forged the draft?" challenged the banker.

"No," drawled Yount. "The Cattlemen's Association furnished that money to the Austin bank for my purpose; but the draft, now that the shootin's over, won't be honored. So forget it. And here's another dollar. I want a new toy bank. Here's a twenty-dollar bill, too. Give me four five-dollar gold pieces."

The banker consummated the transactions and watched Yount slip the gold pieces one by one into the iron donkey. "Must think a lot of the barber's kid," he remarked.

"The barber's younker," mused Yount, "made a man out of the barber."

"Well, you sure put the skids under Santa Rosa."

"Better to say," reflected Yount, "that I removed some of the skids which were sendin' Santa Rosa down the greased chute to hell. I will bid you good-by!"

He went back to the crowd. The sun was dipping over the western rim, and a kind of desolate solitude invaded Santa Rosa. Bill Bent had cut out the members of the wild bunch and herded them apart where they huddled, jaded and somber, around the massive figure of Jake Wallen.

"Get your horses," said Yount. "We ride."

And then he walked over to where the barber stood. "This may or may not be a safe place for you from now on, my friend. You have done me a service, and I won't leave you behind if it's in your mind to pull stakes. Tell me what you want to do."

"I'm stayin'," muttered the barber. "I ain't afraid of anything that comes along—now. But there's one favor I'd like to ask."

"Name it."

The barber shifted, a little embarrassed. "I'd like to have Wallen's gun to hang up in my shop. You see, when my kid grows up, I sorta want him to know that his dad did somethin' he could be proud of. My kid's goin' to be a great man."

Yount's blue eyes gleamed with strange emotion. "Take it and God bless you!" he murmured. "And here's a present for that boy of yours. Here's another bank. And when I get to Irique I shall take all my men and walk into the saloon there and lift a glass—to your boy. May he stand head and shoulders to this crooked weary world, my friend!"

He pivoted sharply, not wishing to see the barber's face just then. The horses were out and men swinging up. Yellowstone Jack was tying the reins of the prisoners and running a lariat through each stirrup.

"When that stage got to Irique I had my eyes peeled," he said to Yount. "For a minute I couldn't tell whether that chalk-mark was a Y or an N. I judged it to mean 'yes' and so I started. The boys in that compartment dam' near died of suffocation. And I'll be mighty pleased to shave off these whiskers and have my hair trimmed after four months. My wife don't like whiskers. Well, we're ready. How about the dead ones?"

"Santa Rosa," replied Yount, repeating an old, grim phrase, "buries its own dead. We'll let it stand like that. Well, catch up, and lead off. It's a long way to go."

The column moved sluggishly eastward down the street. But Yount tarried a moment longer, lost in his own thoughts. Young Bill Bent was by the hotel porch with the girl, and she had one white hand gripped around his arm and was looking up with a hungry pride. He led his horse over and stopped.

"Shooting's done, Bill, and the job's over. But what made you horn in when you didn't have to?"

"We-ell, I was sorta under an obligation to you," muttered Bill.

"Not that much of an obligation."

"Maybe not." Young Bill drew a great breath. "I had to take some sort of a stand, didn't I? When the shootin' started I couldn't stay on the sidelines. It was one side or another. Maybe I have been a blamed fool, but somethin' sort of snapped when the bullets began to plow your way. Maybe I'm crazy, but I just pitched in. Didn't exactly make any decision—just started shootin'."

"Good boy," mused Yount. "If a man is straight, he can't go crooked. Now what?"

"We're going to get married and go out to the Crosskeys," said the girl. "There's an extra house we can use."

Suddenly she ran off the walk and came up to Yount. Her sturdy little arms swept around his neck and she kissed him, the hint of a sob in her throat.

"Thank you—thank you! There will never be a day when we won't think of you!" she whispered.

Yount turned his head and stared long at the golden blaze on the western line. When he looked back, the blue of his eyes had deepened and there were lines around his mouth.

"Right will prevail, though it takes a thousand years," he muttered. "You are a pair of lucky young kids. Remember that. Remember as well, that for many of us the trail is long and lonely. But I've got my reward. I can travel in peace now, knowin' you have won through. God bless you!"

Mounting then, he rode off.

The hotel man, still posted in the lobby door, lifted a broad palm and said, "So-long, Captain! You have mined my business; but come again! Come again and the place is yours."

Yount nodded.