RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

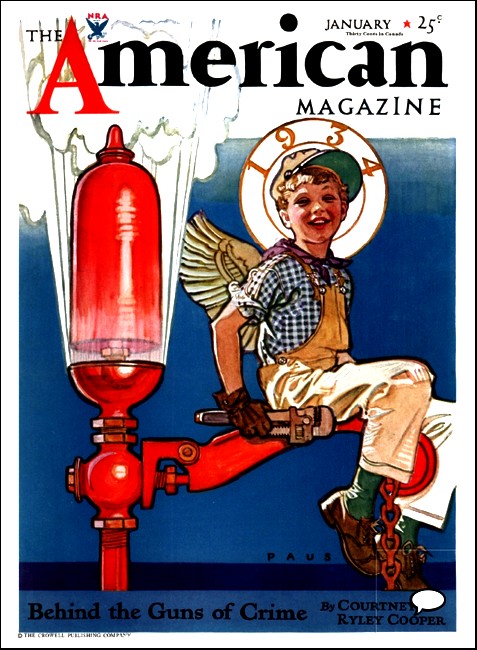

The American Magazine, January 1934,

with "Motives of an Overlord"

This is the story of a sagebrush baron. He disliked men who

rustled cattle and girls who threw stones when they got mad.

NADINE CURTIN entered the intersection with a wholly unlawful recklessness, and a car's brakes snarled at her bare ankles while the last brilliant sunlight of the day made a fluid outline of her slim, striding body.

She was, Bourke Rembeau admitted, watching her, a real Juno of the prairie country and as unquenchably modern as the platinum bracelet on her wrist.

The bustling town of Pendleton was bathed in a stifling heat that rolled cloudlike off the vast hinterland of wheatfield and cattle range, but Nadine skipped briskly up the curb and laid a peremptory hand against Bourke Rembeau's chest. "So it takes a court trial to drag the big beef baron of Ukiah into town. Six o'clock at the Curtin table, mister."

A grin licked across the sun-darkened steadiness of Bourke Rembeau's face. He said amiably, "A party?"

"Purely informal gathering of Pendleton's best unmarried people. Bourke, your eyes are turning hazel and I detect a faint touch of the austere sagebrush autocrat. Too much solitude. Presently you'll have shaggy eyebrows, an ingrown temper, and a tendency to kick stray children out of your path, and I shan't love you any more. At six, my cabbage."

LIKE that—and away; a blithe girl swaggering through the

five-o'clock crowd.

The manners of his own generation were beginning to be a little strange to him, and at twenty-six he felt somewhat like an outlander in this brisk county town he seldom visited. Isolation, that was it. The town kept abreast of the world; it was, in miniature, a network of all the puzzling threads of this complicated century. But the long, bare flats and dun slopes of the yonder range didn't change at all, and he had been so immersed in it the last few seasons that his own outside education now seemed like a faint dust cloud in the far distance.

He thought about it a moment, features indolently taciturn beneath the wide hat-brim, and then dismissed the notion. Little Simon Lent, Bourke's top hand, shuffled out of the crowd and paused on the curb, a rider with shrewd, agate eyes and a dry and silent face that was very misleading. His glance touched some remote object, his talk was thready and indifferent:

"The Cockerline boys been at Kelly's card-room most all day. There ain't much more left of the trial except your testimony."

BOURKE knew what his answer was to be, but he allowed the

silence to run on. It was a habit the ranch had taught him; when

you had a great many men expecting exact judgment, you spoke

slowly and you made your words seem final. He said, at last:

"Keep them in sight, Simon, till the verdict comes in."

Simon took a step backward, was absorbed by the crowd. Bourke Rembeau grinned faintly as he crossed the street. Simon Lent had the instincts of a Pinkerton, and this surreptitious stuff was his meat. Two blocks on, Bourke Rembeau entered the courthouse, turned through a particular door, and ran into the deputy sheriff.

"Like to see Ray Fawl, Tip."

The deputy merely waved his arm. Bourke Rembeau went down a cool corridor bounded by iron gratings and the faces of men looking out at him. He stopped at the end cell, spoke to a man lying belly-down on a bunk. He said, "Hello, Ray."

Ray Fawl rose unhurriedly, and his manner changed when he saw Bourke Rembeau; it at once became reserved and civil. There was, Rembeau thought, a hint of wildness creeping out of the lad's very black eyes, a sign of stubbornness along the straight mouth. But the rather sharp face was proud and clean-shaven, and nothing of the habitual lawbreaker's slovenliness was there. What he saw now was just another young fellow on the borderline, normally honest but too quick-tempered to stand the punishment of hard circumstance. And circumstance had pushed him over the cliff.

"Ray," he said, rather gently, "I didn't pull you into this."

"No, sir," said Ray Fawl; "I know you didn't. A deputy happened to be on the road that night when I came by with the critters in my truck. It's the district attorney that's mad. You been pretty white, Mister Rembeau."

"Don't get me wrong," stated Rembeau. "I'm not Santy Claus, and I don't like my beef rustled."

"That's all right. I got this coming to me."

Bourke Rembeau said, very blunt, "Things were pretty quiet and you couldn't find a job riding. You needed some money bad. So you went for this gag. I know why you wanted the money, Ray."

RAY FAWL put both hands around the bars and stared at Rembeau

with a drawn expression. "Let's leave Lily out of this. Mister

Rembeau."

"The district attorney isn't shooting at you, Ray. Why don't you open up?"

Fawl said, "I don't get that," guardedly, and his face lost expression.

Rembeau shrugged his wide shoulders. "You're a deuce in the deck. The boys who drew you into this mess will get the money and you'll get the sentence. Don't you know they always let the other fellow do the dirty work? In court tomorrow, lay it out plain, You don't belong to that gang. You got pulled into it."

"No," said Ray Fawl in a soft, dogged voice; "that won't do. I don't yell."

"If you're turned free, then what?"

For the first time—and Bourke Rembeau was watching for it—the youngster's eyes showed desperation. He said, "I'm in kind of deep. They got me over a barrel—you know who I mean. But I won't get free." He stared at Rembeau. "Listen—I wish you'd see Lily. Tell her the fire died out."

"I'll see her."

"I always thought mighty highly of you, Mister Rembeau."

"So you took my beef?"

"You know how it goes," said Fawl quietly.

Rembeau nodded and left the corridor. The deputy at the door said, "Nothin' to it—the judge'Il throw the book at him."

"That please you, Tip?"

The deputy stared. "I hate to shoot at big game and get a rabbit. Those other boys are clever, Bourke."

VERY clever, Rembeau thought, as he left the courthouse and

struck out for the hotel. Loyalty was a thing that bound men's

hands and tongues oddly; and there in the cell Ray Fawl nursed

his own personal tragedy and would not speak, while the

Cockerlines, behind all this, played pool at Kelly's. "They have

nibbled at me a long while," he told himself, "and they think I

won't protest." Anger streaked through him, and his lower lip

folded slow across the upper, and he was at that moment a burly

shape sightlessly tramping down the street.

In the hotel lobby he paused a moment at the dining-room entrance, until one of the waitresses there saw him, halted instantly, and showed a slow fright; then he went on up to his room, shaved and scrubbed, and brushed his suit.

He was smoking a cigarette when the knock came. The waitress entered, her features bitterly and clearly framed against the starched Dutch collar of her uniform. She was, Rembeau thought, very pretty, but her eyes were dark and without any hope at all.

He said, "Lily, what did Ray want money for?"

Lily Dreck closed the door and supported herself against it....

EVERYBODY talked at once, and the conversation simply went

over hill and dale until some scent drew the whole pack to a

common topic in a flurry of sharp, unsentimental comment. Sixteen

people sat around Nadine Curtin's table and seldom bothered to be

serious; and all this made Bourke Rembeau feel a little strange

and stiff at the joints, and he sat mostly silent while the

repartee crackled over his rugged red head.

Conscious of a girl's slim hands lying gracefully motionless at the other side of the table, he thought that he had somehow drifted from this crowd, of which he had been a part only two years before. It was very gay, but for him the old ease was gone, and in its place was the smell and sight of the range and a ruthless present in the shape of the Cockerline boys playing pool at Kelly's.

He lifted his eyes from the opposite girl's hands to her face; and then it was like being shocked out of a long sleep. He was aroused and astonished, and he said in a rather odd voice, "Hello, Elsa."

Nadine Curtin's voice cut arrestingly through the chatter: "It took him just twenty-one minutes to discover her."

There was enormous and inordinate laughter along the table, and Elsa Ballard's very definite face slowly, gently colored. Something had happened to this girl he had known since childhood. All the contours of her features were fair and serene and still, and her return glance was straighter, more deliberate than he remembered. Poise. A distant serenity.

Bourke Rembeau laid his elbows on the table and brushed aside the surrounding crockery. Something had happened. "What have you done to your hair?"

"Didn't you know, Bourke?" interposed Nadine, still ironic. "She's been in Portland for two years."

"Yes," said Rembeau, "yes; I knew." The passive bronze features stirred; recklessness rose and showed itself. "I could always make you lose your temper, Elsa."

Her smile was a faint glow in her eyes; the rest of her face was untouched, reflective. "You always wanted your own way, Bourke. You still do."

"This will be good," said Nadine Curtin. "Go after her, Bourke. Do you remember in high school, when Haley Wyatt took her to the dance and you—"

"You don't need to pour oil on a good fire," said Elsa Ballard gently. "Bourke and I always supplied our own fuel." She watched him, and her lips formed a looser, more thoughtful curve. "It started in the eighth grade. He wanted to be the gallant cavalier sweeping off the prairie. He never liked opposition. And so here he is now, the overlord of Box R range, a sagebrush baron, the court of first and last resort for fifty men and such surrounding territory as he can claim through feudal assumption."

THE quiet deepened. Nadine said, "This is very familiar. It is

practically spontaneous combustion."

"When she got mad," said Rembeau, "she always threw rocks at the boys. She still does. But there's something else."

He stopped, demanding her attention and keeping it. In his more arrogant youth he had liked to rouse the stormy brilliance across that level line of brow so that he might see the sad and forlorn afterglow. But he could not break this present calm. She was a still, poised woman with a mass of black hair shining against satin skin; a woman turned serene and remote, judging from a great distance. He continued, spuriously calm:

"You went to Portland and changed the style of your hair and tried to become Judge Ballard's refined daughter. You think you've run away from the tree-climbing and one-old-cat stage. It won't work, Elsa. You always loved a fight. You never could stay out of one. You can't be a fine lady."

The man beside Elsa Ballard—Bourke Rembeau didn't know him—spoke with perceptible wonder: "Will somebody lend me the diagram?"

"Don't be disturbed," said Nadine Curtin. "They're washing out the linen. It goes back a good many years. It's it's just another Pendleton tradition."

Bourke Rembeau studied this man, and Nadine, uncanny in her perceptions, spoke again: "You probably didn't catch on when I introduced you, Bourke. That's Harris Steele, from Portland. Harris and Elsa have not yet announced their engagement."

"She's a spitfire, Steele," said Bourke Rembeau in a purring tone. Then he looked suddenly at Elsa Bullard again, and caught her off guard; there was, behind the deep calm, a streak of uncertainty. He said instantly. "Lend me this girl for the evening, Steele?"

"You see?" murmured Elsa. "The cavalier sweeps off the prairie, all gallant and dusty, and makes his demands at the point of a gun."

"Fear," taunted Bourke Rembeau, "is something new in you."

"Lend me to the gentleman, Harris," murmured Lisa in a silken voice.

"Lent," said Harris Steele agreeably.

There was an accented silence all along the table. "Harris," observed Nadine Curtin with latent pity, "remember to think of this when you return to Portland. You are among barbarians, and generosity means nothing to them. We're all going down to the station to see that pickled whale on exhibition in the tank car."

NOTHING had changed, Bourke Rembeau thought, as he waited at

the doorway. After the two-year intermission they took up scorn

and malice where these weapons had been laid aside; and it was

tooth and claw, as always. He watched Elsa come across the room,

her slender body weaving through the crowd and her shoulders

square beneath the short wrap. He clapped on his broad hat, and

her hand accepted his crooked elbow almost weightlessly, and for

the moment there was the illusion of agreement. All the couples

fell gayly behind, and they sauntered down the hill into

Pendleton's main street.

He said, "What kept you two years in Portland, Irish?"

Elsa Ballard's profile had the luminous clarity and composure of an ivory medallion. "Working for my living, in an office.... Bourke, If you don't mind, no more 'Irish.'"

"Give me a decent reason."

"Because nicknames belong to a period—and the period is past."

"So you're Judge Ballard's daughter and you've changed your hair and you must be a lady. Well—"

But he said no more. The street lights were just coming on; and in front of Kelly's card-room, directly ahead, he saw the two Cockerline boys idly speaking with a few other men. The fragrance of the night dissolved, and the momentarily recaptured irresponsibility fell away and became as strange as the pleasant talk of the people behind. IT was plain enough. This girl's swift, sometimes cruelly clear mind never erred. A period was past.

"Cover the old ground," said Elsa Ballard, "if your heart is in it. Tonight is all you have. I'll not be lent again."

THE Cockerline boys had seen him; they had turned his way. And

now, face to face with the pair, he stopped, and his tall, flat

frame overshadowed both these svelte, olive-colored men.

Nadine Curtin's crowd drifted in and halted, and a wary,

understanding silence touched them all. Elsa Ballard swiftly

lifted her eyes to Bourke; they were, he thought, stirred by the

old fire. But he could not be sure. Lon and Kerby Cockerline were

very grave and very courteous, and his own talk was suavely

changeless. "Good-evening, boys."

"Hello. Bourke. Trial bring you in?"

"I suppose I'll be called on."

"Tough on Ray Fawl," suggested Kerby Cockerline.

"I regret that." said Rembeau.

"I noticed a part of your fence busted the other day by Spiller Creek." said Lon, with the same general politeness. "Thought you might want to know."

"Thanks," said Bourke, and bowed and went on.

Nadine Curtin's crowd ambled behind, silent still; but Elsa Ballard suddenly and bluntly spoke:

"The formula never varies. The master of a Box R range meets two common thieves, and the exchange of civility is exquisite. The overlord must never exhibit the weakness of anger in public. And his justice must be swift and personal, out in the sagebrush. You have perfectly absorbed the code, Bourke."

"In two years' absence how would you know about the Cockerline boys?"

"I am kept well informed."

Nadine's voice ran forward, energetically angry: "It Is outrageous. The jail will never hold those two scoundrels. But at least we have caught one of the gang. Ray Fawl will go to the penitentiary."

Bourke Rembeau spoke to Elsa, in a low and ragged and tired voice: "You're a working girl in Portland. Why don't you forget Pendleton, then?"

She looked up quickly, surprise brightening her glance. After a while she said, "Why don't I?"

THE street ran across the tracks, and three great floodlights

transfixed a tank car standing there with a platform built beside

it. Bourke Rembeau paid for the crowd and hoisted Elsa up the

steep steps; and they looked down at the dark leviathan preserved

in the rankly odorous brine. It was interesting enough, but

Bourke Rembeau's mind returned to the front of Kelly's card-room

and anger burned in his stomach.

The stench had turned Elsa Ballard a little pale. Bourke led her silently from the platform into the station. He said to the ticket agent, "Two separate lowers to Portland," and, when he got them, he steered her out along the dark runway. They strolled through the street again, leaving Nadine Curtin's crowd behind.

"Why?" asked Elsa, quietly curious.

He was a little bitter, faintly morose. "Obscure motives of an overlord."

"You always were shrewd. I never knew you to ever do a purposeless thing. When you talked to the Cockerline boys I saw your eyes tear them apart. Very cold and cruel behind those smooth words."

"You've forgotten the range."

"Perhaps. I have not forgotten you."

He said, more to himself than to her, "The end of a period."

The Curtin porch, when they reached it, was full of soft shadow, and all the noises of the town lay muted below. Elsa Ballard turned. "Are you coming in?" But Bourke Rembeau only shook his head and remained at the foot of the steps.

"So the loan is being returned, without thanks?" she asked.

"I recall," he reflected, "that we always fought. Why did we bother to do it, Irish? Why didn't we just keep out of each other's way?"

She said, "The responsibility of your ancestral acres has improved you. Bourke. You aren't just plain wild any more. The rest is the same. You've become exactly what I knew you would—the feudal chief exacting obedience and loyalty. You protect your subjects, even against the law. The grand manner. The same now as when you came out of the desert with your lunch bucket and eighth-grade geography tied to the cantle. But the manner is more plausible now—and more romantic to the unsuspecting. And more dangerous."

He said, suddenly aware, "We're too much alike, Irish. We can't stand surrender."

"Bourke!"

HE went quickly into the street, and in heavy reflection

returned to his room, to find Simon Lent waiting there.

"Still at Kelly's," the top hand said.

Rembeau looked down at this little man, affected by the unswerving loyalty so ever-present there.

"The court can't touch 'em, can it, Simon?"

"No," said Simon Lent in a dusty voice. "It never has."

"Ray's looking ten years in the face," mused Bourke Rembeau. "But if he does get free he'll go back to the Cockerlines. What have they got on him, Simon?"

"Threats," murmured Simon Lent. "They're here to see he doesn't squeal. If he beats this charge they'll take him back to the brush. By force."

"Simon," said Bourke Rembeau, "are those front doors at the card-room built so they can be closed in h hurry?"

Simon Lent looked up at his boss: and the agate-green eyes flared behind narrowing lids. He asked no questions; he showed no surprise. He merely remained silent and pondering, and presently rose and shuffled to the door. "I'll find out."

Bourke Rembeau sat on the edge of the bed, darkly obsessed by the problem. The court had never touched the Cockerline boys, never would. The aegis of the law theoretically covered yonder hills and valleys, but it was still, as in the past, a country full of white spaces. The Cockerline boys knew it, and walked the streets of Pendleton freely. The old-timers of the range knew it, and looked silently on, remembering the ancient remedy.

"Overlord!" Bourke said to himself dismally. "The time of personal slaughter on the range is over. But the court will never touch them There's another medicine needed here."...

HE was on the courthouse steps when a young assistant to the

prosecuting attorney came out and said, "Ready for you, Mister

Rembeau," and he followed the lad in. The courtroom was quite

crowded. In the rows he saw Nadine Curtin and her crowd, and Elsa

Ballard sat in an aisle chair and caught his eye, and made him

pause. She said, an acid irony coating the barb of that phrase,

"A dramatic entrance. You do it so well."

"Mr. Rembeau." called the district attorney, "take the stand."

He was sworn In. The district attorney paced slowly forward. At the further desk young Ray Fawl's features slowly unlocked from apathy. The district attorney said:

"Bourke, for the record, what is your occupation?"

Rembeau grinned at the district attorney. It was a very old formula. "I run a ranch out in the Ukiah," he said, "which operates certain recorded cattle brands."

"Is Box R one of your branch?"

"Yes,"

"Any cow, steer, or calf bearing that brand belongs to you?"

"Yes, unless vented or sold by bill of sale."

THE district attorney paused, and in the interval Bourke

Rembeau studied the jury. They were nearly all Pendleton people.

But there wan a man in the back row dressed in the shabby

clothes of a rider; a weatherworn, shackle-figured man who

belonged outside the court and outside the town. The rest were

indifferent, but the one solemn character looked at Rembeau very

gently, and Rembeau knew he was listening, as a cattle hand would

listen, for all the inflections below the registered words, for

the shadow of things not spoken.

The district attorney said, suddenly, "That's all. I only wanted to establish the ownership of the two cows found In Ray Pawl's truck."

Rembeau met that one juror's eyes and spoke smoothly into the silence: "I regret they found my beef on Ray's truck, if they did. Ray used to work for me, and I always considered him a good hand."

"Your Honor," said the district attorney sharply, "I ask that the last statement be struck from the record."

"Strike it from the record," said Judge Ballard.

A murmur washed through the room, and the judge tapped his desk lightly with the gavel. It was taken from the record, Rembeau agreed, but not from the sagebrush juror's mind; the man leaned back and folded his thin hands across a flat belly, and a sudden satisfaction smoothed out the weather wrinkles of his face.

Going slowly down the aisle, Rembeau got the raking survey of the court crowd. A man ducked rapidly ahead of him, through the doorway, and Elsa Ballard's face was minutely scornful. On the courthouse steps Nadine Curtin overtook him.

"You," she said frankly, "are a deep and devious devil. What was that for?"

"Wasn't it plain?"

"You talk like my grandfather Murre, who went through the sheep wars and ever afterwards spoke in parables. Well, we're all having lunch on top of the hill at Judith Graham's."

"Nadine, don't hope for any more fight from me. The old argument's played out."

She only winked and retreated. Bourke Rembeau strolled thoughtfully to the hotel. He tarried in the lobby a moment until little Simon Lent shuttled off the street and stood aimlessly beside him.

"I'll be at the Graham house," said Rembeau quietly. "The jury will have this case pretty soon."

HE went on up and scrubbed, and brushed his clothes. He laid

the envelope containing the two tickets on the bureau and

smoothed it gently with his fingers. He folded a hundred-dollar

bill in with the tickets and sealed the envelope and punched the

room bell. To the arriving boy, he said:

"Give this letter to Lily Dreck."

He quickly left the room. Some things were pretty personal and he didn't want to see Lily Dreck's eyes again. Climbing the hill to the Graham house he found Nadine Curtin's crowd, before him, eating a picnic lunch on the felted grass.

Nadine's voice was crisp and inquisitive; she was a little ruthless when puzzled: "You said so very little, Bourke. But you damned the case against Ray Pawl without lifting your voice. Why? He's a thief, and what are courts for?"

The men were dark, solid figures along the grass. But the women made vivid plaques in the sunlight, the bright patterns of their summer dresses lying careless against supple, indolent bodies, Elsa Ballard's broad hat deepened the inscrutability of a still and dreaming face.

"He never does a purposeless thing," she mused. "He has his own plans. Your entrance was splendid, Bourke. You spoke from the throne, in the grand manner, softly but very surely, and you walked out with the eyes of the crowd following."

Nadine Curtin's glance skewered Elsa Ballard—and moved on to Bourke Rembeau's unmoved countenance.

Harris Steele said, "What plan would you have which makes it necessary to defend a crook? I'm merely curious."

"Never ask the direct question," murmured Elsa Ballard. "It is tradition again. Silence for the overlord. Silence and fidelity to the code which only has to be whispered, as in court today, to make courts ridiculous and judges foolish. You see, Harris, this Ray Fawl once worked for Bourke. Noblesse oblige. The overlord takes care of his kind, even when they steal from him."

The rest of the crowd became mere shadows. It was Elsa and himself, rancorously fighting. Her body was relaxed against the lawn, but her eyes glowed; the girlhood blaze was there again.

He said, "Bitterness in you is also something new. You used to throw rocks for the pure pleasure of battle. Why the added venom?"

"Perhaps I nourished a faint hope."

"Of what?" he asked bluntly.

Nadine Curtin broke the brittle pause: "Harris, I told you last night generosity was no good. You will live to regret it."

"No," said Elsa Ballard. "Never, Nadine. It isn't romantic. It never was."

There was something here, but Bourke Rembeau didn't get it. The crowd had gone silent; there was, actually, nothing more to say.

Little Simon Lent was climbing the street steps, and he stopped a little way off and stood diffidently there, plainly bearing important news. Bourke Rembeau rose and put on his hat.

"We seem to grow up," he said. "Metamorphosis of one of the gang into a sagebrush tyrant. I suppose that is very true. My house has twelve bedrooms and three fireplaces and a creek to swim in. Come down some time and I'll set up the venison haunches for all of you; and maybe even find a court minstrel."

He turned, but he lingered a moment more looking down at Elsa Ballard. He said, "When you're back in Portland, Irish, think no more about it. Memories are hard to live with. Really, Steele, I congratulate you. This woman has her faults, but she's alive. If you can make her angry, she'll love you."

He went on then, joining Simon Lent.

Simon said confidentially, "Jury disagreed and the judge turned Ray loose. The Cockerline boys are still at Kelly's."

They went down the slope. At the foot of the hill they swung Into the main street. Kelly's was ahead, and Lon Cockerline came across the intersection, arm in arm with young Ray Fawl, who seemed heavily troubled. They disappeared inside Kelly's, and Simon Lent merely whispered, "It's a little brazen. Force, sure. The kid knows he can't buck 'em."

KELLY'S had two sections, the cigar-stand in front and the

pool-room behind. Swinging through, Bourke Rembeau paused by the

sliding doors separating the two sections. It was effective

enough, this entrance. Both Cockerlines looked at him across the

row of pool tables, and half a dozen men stopped playing and laid

down their cues. Ray Fawl suddenly showed outrage and struck away

Cockerline's detaining hand and stood straight on his legs; gone

grave, gone pale.

"Outside, if you please, gentlemen," said Bourke to the extra people there "You, too, Ray."

The Cockerlines remained very still while all this shifting went on. Men stood attentively in the cigar-store, beyond the doors. Bourke Rembeau said, over his shoulders to little Simon Lent:

"Did you find out if those doors closed quickly?"

"What is it?" challenged Lon Cockerline, and watched Simon Lent draw the doors together.

"Either of you boys carry guns?" murmured Bourke Rembeau.

Lon Cockerline was grinning. "Would we be that kind of fools in Pendleton?"

Bourke said, "You're a clever pair and the courts won't hold you, and you figured this was the wrong year for gunplay out in the brush. That's quite right. But there's one more way left. This is strictly personal, boys."

Lon Cockerline said, in a breathing voice, "Very good, Bourke."

"When we're through here," murmured Bourke Rembeau, "your days in this particular country are done."

The pool-room doors squealed from the applied pressure of men beyond them. Lon Cockerline drew his heavy shoulders together. Kerby Cockerline seized a billiard cue, broke it across the edge of a table, and grabbed the heavy end in his fist, without expression or comment. Bourke Rembeau sucked in a long breath and laughed at them, and swung forward....

IT was close to dusk, with the light at the hotel windows

growing more and more smoky. Bourke Rembeau stood in the middle

of the room. There was one raw welt across his cheek where Kerby

Cockerline's pool butt had landed, the knuckles of his fists were

scarred red. Little Simon Lent remained very still and looked at

Bourke Rembeau with an expression purely beatific.

"Kerby," he said gently, "fainted on the hospital steps, and Lon's there waiting. They ain't very pretty."

"They forgot something. You can't be a first-rate bad man after you've been used to scrub up a pool-room floor. A reputation for toughness depends on bein' lucky. They weren't lucky today. They're through, Simon."

"Think they'll go?"

"A bad man can't stand bein' laughed at. They'll go."

Simon Lent's tone was like dry leaves rustling: "I been afraid some time you wouldn't call that pair, Bourke."

Bourke Rembeau's smile was thin; not bitter, but not cheerful. "Survival, of course. Everybody on the range understands it. But there'll be a lot of people in Pendleton who won't. They will say another cattleman came to town and got arrogant, and kicked a couple of men out of his way just for fun." He hauled his body around, his back to Lent. "She's very sharp—always was. And she's right. It is the end of a period. But it ended a long lime ago. I should have known it. Simon, memories are hard things to live with."

"What?" said Simon Lent.

"Bring the car around. We're going back home."

Simon Lent departed. Bourke Rembeau filled a pipe, and smoke smoldered furiously out of the bowl. "Gallant cavalier comes off the prairie, and goes back again with nothing for his ride but the dust." There was a knock at his door.

"What are you so darned polite for, Simon? Come in."

ELSA BALLARD came in and closed the door behind her and put

her back to it; and looked across to him. Bourke Rembeau

concealed an utter astonishment behind motionless features. He

said, faintly ironical. "The judge's daughter steps out of her

part and visits a man's room. Irish, haven't you had enough of

this?"

"I ought to have remembered you never did a purposeless thing, Bourke. I should have remembered it at the trial. Lily Dreck and Ray Fawl left an hour ago for Portland, on your two tickets, to be married. You wanted to protect them. It was the Cockerline boys you wanted to destroy—and did."

"How would you know?"

She was instantly impatient.

"Do you suppose I could lei it stand, as it stood this noon at the Grahams', without a better answer? You know I hate mystery. I've got to have reasons. So I went out this afternoon and found them."

He came on until he might have touched her small, erect shoulders. The fragrance of perfume rose from her dark head.

"I can't keep this up, Irish. I've lost my taste for fighting."

She said, "Do I detect a break in the overlord's unconquerable manner?"

"Give me credit for growing up, Elsa. I know when I lose."

"What have you lost, Bourke?"

"Why did you come here?" he said.

"I could tell you now why we always fought. It was because I could never find any satisfactory place in your self-sufficient life. What else could I do but quarrel? Perhaps I've also had a bad two years."

"What of it?" he said angrily.

Her talk remained on a low, lucid tone: "Does it seem entirely accidental I should visit Pendleton the exact time a trial brought you to town? Perhaps I should like to be the overlord's wife."

"Supposing I don't want that?"

There was a little pause. He could not see the stirring shift of emotion ill her eyes.

She said then, coolly, "You lie. You never could deceive me. We both know better, Bourke. We know better—now."

"Elsa," he said, rash and headlong, "this has been hell!"

"Well, Bourke"—and that phrase went upward, gay and quick—"why am I here?"

Little Simon Lent, opening the door, found that something stopped its free swing. He put his head through, and he saw them, there in the heavier shadows, desperately holding to each other. It was very Still; it was very odd. Little Simon withdrew his head and closed the door with a labored noiselessness that was unnecessary. And he squatted on his heels in the hall and built himself a smoke—agate eyes profoundly pleased.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.