RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

The Passing Show, 15 May 1932, with "Cattle Country Trouble"

He moved his fingers up to the pocket of his shirt and dropped

them immediately away, searching the smoky horizon with his glance.

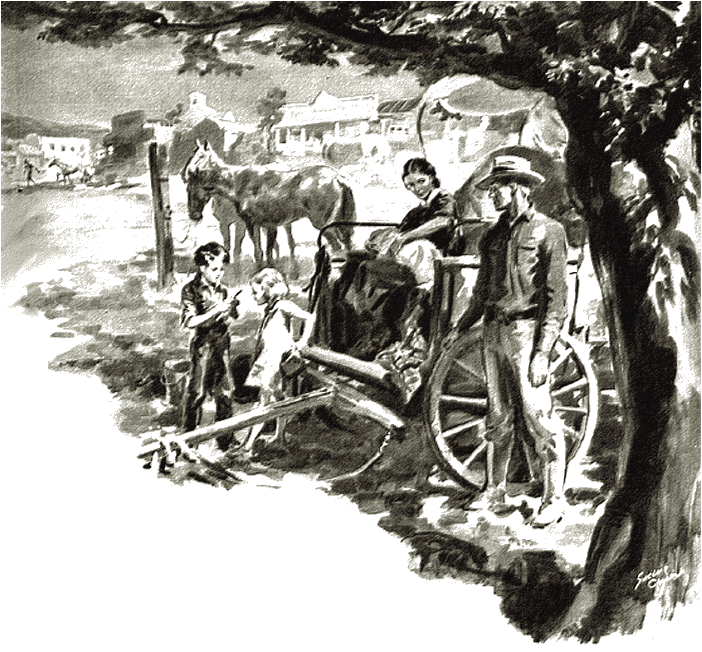

THEY reached Two Dance around ten that morning and turned into the big lot between the courthouse and the Cattle King Hotel. Most of the homesteaders camped here when they came to town, for after a slow ride across the sage flats, underneath so hot and so yellow a sun, the shade of the huge locust tree was a comfort. Joe Blount unhitched and watered the horses and tied them to a pole. He was a long and loose and deliberate man who had worked with his hands too many years to waste motion, and if he dallied more than usual over his chores now it was because he dreaded the thing ahead of him.

His wife sat on the wagon's seat, changing the baby. She had a pin in her mouth and she was talking around it, to young Tom: "Stay away from the horses on the street and don't you go near the railroad tracks. Keep hold of May's hand. She's too little to be alone, you remember. Be sure to come back by noon."

Young Tom was seven and getting pretty thin from growth. The trip to town had him excited. He kept nodding his sun-bleached head, he kept tugging at little May's hand and then both of them ran headlong for the street and turned the corner of the Cattle King, shrilly whooping as they disappeared.

Blount looked up at his wife. She was a composed woman and not one to bother people with talk, and sometimes it was hard for a man to know what was on her mind. But he knew what was there now, for all their problems were less than this one and they had gone over it pretty thoroughly the last two-three months. He moved his fingers up to the pocket of his shirt and dropped them immediately away, searching the smoky horizon with his glance. He didn't expect to see anything over there, but it was better than meeting her eyes at this moment. He said, in his patiently low vioce: "Think we could make it less than three hundred?"

The baby moved its arms, its warm-wet fingers aimlessly brushing Hester Blount's cheeks. She said: "I don't see how. We kept figuring—and it never gets smaller. You know best, Joe."

"No," he murmured, "it never gets smaller. Well, three hundred. That's what I'll ask for." And yet, with the chore before him, he kept his place by the dropped wagon's tongue. He put his hands in his pockets and drew a long breath and looked at the powdered earth below him with a sustained gravity, and was like this when Hester Blount spoke again.

He noticed that she was pretty gentle with her words. "Why, now, Joe, you go on. It isn't like you were shiftless and hadn't tried. He knows you're a hard worker and he knows your word's good. You just go ahead."

"Guess we've both tried," he agreed. "And I guess he knows how it's been. We ain't alone." He went out toward the street, reminding himself of this. They weren't alone. All the people along Christmas Creek were burnt out, so it wasn't like he had failed because he didn't know how to farm. The thought comforted him a good deal, it restored a little of his pride. Crossing the street toward Dunmire's stable he met Chess Roberts, with whom he had once punched cattle on the Hat outfit, and he stopped in great relief and palavered with Chess for a good ten minutes until, looking back, he saw his wife still seated on the wagon. The sight vaguely troubled him and he drawled to Chess, "Well, I'll see you later," and turned quite slowly towards the bank.

There was nothing in the bank's old fashioned room to take a man's attention. Yet, when he came into its hot shaded silence, Joe Blount removed his hat and felt ill at ease as he walked towards Lane McKercher. There was a pine desk here and on the wall a railroad map showing the counties of the Territory in colours. Over at the other side of the room stood the cage where McKercher's son waited on the trade.

McKercher was big and bony and grey and his eyes could cut. They were that penetrating, as everybody agreed. "Been a long time since you came to town. Sit down and have a talk," and his glance saw more about Joe Blount than the homesteader himself could ever tell. "How's Christmas Creek?"

Blount settled in the chair. He said, "Why, just fine," and laid his hands over the held hat. Weather had darkened him and work had thinned him and gravity remained like a stain on his cheeks. He was, McKercher recalled, about thirty years old, had once worked as a puncher on Hat and had married a girl from a small ranch over in the Yellows. Thirty wasn't so old, yet the country was having its way with Joe Blount. When he dropped his head the skin around his neck formed a loose crease and his mouth had that half-severe expression which comes from too much trouble. This was what McKercher saw. This, and the blue army shirt washed and mended until it was as thin as cotton; and the man's long hard hands lying so loose before him.

McKercher said, "A little dry over your way?"

"Oh," said Blount, "a little. Yeah, a little bit dry."

The banker sat back and waited and the silence ran on a long while. Blount moved around in the chair and lifted his hands and reversed the hat on his lap. His eyes touched McKercher and passed quickly on to the ceiling. He stirred again, not comfortable. One hand reached up to the pocket of his shirt, dropping quickly back.

"Something on your mind, Joe?"

"Why," said Blount, "Hester and I have figured it out pretty close. It would take about three hundred dollars until next crop. Don't see how it could be less. There'd be seed and salt for stock and grub to put in and I guess some clothes for the kids. Seems like a lot but we can't seem to figure it any smaller."

"A loan?" said McKercher.

"Why, yes," said Blount, relieved that the explaining was over.

"Now let's see. You've got another year to go before you get title to your place. So that's no security. How was your wheat?"

"Burnt out. No rain over there in April."

"How much stock?"

"Well, not much. Just two cows. I sold off last fall. The graze was pretty skinny." He looked at McKercher and said in the briefest way. "I got nothing to cover this loan. But I'm a pretty good worker."

McKercher turned his eyes toward the desk. There wasn't much to be seen behind the cropped grey whiskers of his face. According to the country this was why he wore them—so that a man could never tell what he figured. But his shoulders rose and dropped and he spoke regretfully. "There's no show for you on that ranch, Joe. Dry farming—it won't do. All you fellows are burnt out. This country never was meant for it. It's cattle land and that's about all."

He let it go like that, and waited for the homesteader to come back with a better argument. Only, there was no argument. Joe Blount's lips changed a little and his hands flattened on the peak of his hat. He said in a slow, mild voice. "Well, I can see it your way all right," and got up. His hand strayed up to the shirt pocket again, and fell away—and McKercher, looking straight into the man's eyes, saw an expression there hard to define. The banker shook his head. Direct refusal was on his tongue and it wasn't like him to postpone it, which he did. "I'll think it over. Come back about two o'clock."

"Sure," said Blount and turned across the room, his long frame swinging loosely, his knees springing as he walked, saving energy. After he had gone out of the place McKercher remembered the way the homesteader's hand had gone toward the shirt pocket. It was a gesture that remained in the banker's mind.

BLOUNT stopped outside the bank. Hester, at this moment

was passing down towards the dry good's store with the

baby in her arms. He waited until she had gone into the

store and then walked on toward the lower end of town, not

wanting her to see him just then. He knew McKercher would

turn him down at two o'clock. It had been in the banker's

tone and he was thinking of all the things he meant to

explain to McKercher. He was telling McKercher that one or

two bad years shouldn't count against a man. That the land

on Christmas Creek would grow the best winter wheat in the

world. That you had to take the dry with the wet. But he

knew he'd never say any of this. The talk wasn't in him,

and never had been. Young Tom and little May were over the

street, standing in front of Swing's restaurant, seeing

something that gripped their interest. Joe Blount looked at

them from beneath the lowered brim of his hat; they were

skinny with age and they needed some clothes. He went on

by, coming against Chess Roberts near the saloon.

Chess said: "Well, we'll have a drink on this."

The smell of the saloon drifted out to Joe Blount, its odour of spilled whiskey and tobacco smoke started the saliva in his jaws, freshening a hunger. But Hester and the kids were on his mind and something told him it was unseemly, the way things were. He said: "Not right now. Chess. I got some chores to tend. What you doing?"

"You ain't heard? I'm riding for Hat again."

Blount said: "Kind of quiet over my way. Any jobs for a man on Hat?"

"Not now," said Chess. "We been layin'off summer help. A little bit tough this year, Joe. You havin' trouble on Christmas Creek?"

"Me? Not a bit. Chess. We get along. It's just that I like to keep workin."

After Chess had gone, Joe Blount laid the point of his shoulder against the saloon wall and watched his two children walk hand in hand past the windows of the general store. Young Tom pointed and swung his sister round; and both of them had their faces against a window, staring in. Blount pulled his eyes away. It took the kids to do things that scraped a mans pride pretty hard, that made him feel his failure. Under the saloon's board awning lay shade, but sweat cracked through his forehead and he thought quickly of what he could do. Maybe Dunmire could use a man to break horses. Maybe he could get on hauling wood for the feed store. This was Saturday and the big ranch owners would be coming down to the Two Dance grade pretty soon. Maybe there was a hole on one of those outfits. It was an hour until noon, and at noon he had to go back to Hester. He turned toward the feed store.

Hester Blount stood at the drygood's counter of Vetten's store. Vetten came over but she said. "I'm just trying to think." It was warm in here, but shadowed, and the smell of all the bolts of cloth and furnishings and fabrics was pleasant to a person who hadn't set foot in a store for six months. She laid the baby on the counter and watched it lift its feet straight in the air and aimlessly try to catch them with its hands; and she was thinking that the family needed a good many things. Underwear all round, and stockings, and overalls.

LITTLE May had to have some material for a dress, and

some ribbon. You couldn't let a girl grow up without a few

pretty things, even out on Christmas Creek. It wasn't good

for the girl. Copper-toed shoes for young Tom, and a pair

for his father; and lighter buttoned ones for May. None of

these would be less than two dollars and a half, and it was

a crime the way it mounted up. And plenty of flannel for

the baby.

She had not thought of herself until she saw the dark grey bolt of silk lying at the end of the counter, and when she saw it, something happened to her heart. She went over and rubbed the silk's heavy surface between her fingers, feeling its luxury. It wasn't good to be so poor that the sight of a piece of silk made you feel this way. She turned from it, ashamed of her thoughts—as though she had been guilty of extravagance. Maybe if she were young again and still pretty, and wanting to catch a man's eyes, it might not be so silly to think of clothes. But she was no longer young or pretty and she had her man. She could take out her love of nice things on little May, who was going to be a very attractive girl. As soon as Joe was sure of the three hundred dollars she'd come back here and get what they all had to have and somehow squeeze out enough for the dress material and the hair ribbon. She stood here thinking of these things, and so many others—a tall and rather comely woman in her early thirties, dark-faced and carrying an even, sweet-lipped gravity while her eyes sought the drygoods shelves and her hand unconsciously patted the baby's round middle.

A woman came bustling into the store and said in a loud, accented voice: "Why, Hester Blount, of all the people I never did expect to see!"

Hester said. "Now isn't this a surprise." and the two took each other's hands and fell into a quick half embrace. Ten years ago they had been girls together over in the Two Dance, Hester and this Lila Evenson who had married a town man. Lila was turning into a heavy woman, and like many heavy women she loved white and wore it now, though it made her look big as a house. Above the tight collar of the dress, her skin was a flushed red and a second chin faintly trembled when she talked. Hester Blount stood motionless, listening to that outpour of words, feeling the quick search of Lila's eyes. Lila, she knew, would be taking everything in—her worn dress, her heavy shoes, and the lines of her face.

"And another liaby!" said Lila and bent over it and made a long gurgling sound. "What a lucky woman. That's three? But ain't it a problem, out there on Christmas Creek? Even in town here I worry so much over my one darling."

"No," said Hester, "we don't worry. How is your husband?"

"So well," said Lila. "You know, he's bought the drugstore from old Kerrin, who is getting old. He has done so well. We are lucky, as we keep telling ourselves. And that reminds me. You must come up to dinner. You really must come this minute."

They had been brought up on adjoining ranches and had ridden to the same school and to the same dances. But that was so long ago, and so much had changed them. And Lila was always a girl to throw her fortune in other people's faces. Hester said, gently, regretfully: "Now isn't it too bad. We brought a big lunch in the wagon, thinking it would be easier. Joe has so many chores to do here."

"I have often wondered about you, away out there." said Lila. "Have you been well? It's been such a hard year for everybody. So many homesteaders going broke."

"We are well," said Hester slowly, a small hard pride in her tone. "Everything's been fine."

"Now that's nice," murmured Lila, her smile remaining fixed; but her eyes, Hester observed, were sharp and busy—and reading too much. Lila said, "Next time you must come and see us," and bobbed her head and went out of the store, her clothes rustling in the quiet. Hester's lips went sharp-shut and quick colour burned on her cheeks. She took up the baby and turned into the street again and saw that Joe hadn't come yet to the wagon. The children were out of sight and there was nothing to do but wait. Hearing the far-off halloo of a train's whistle, she walked on under the board galleries to the depot.

Heat swirled round her and light flashed up from polished spots on the iron rails. The flat valley ran empty and sage-studded into the far away Mauvaise hills and the sky above was the unmarred blue of a robin's egg. Around her lay the full monotony of the desert, so familiar, so wide—and sometimes so hard to bear. Backed against the yellow depot wall she watched the train rush forward, a high plume of white steam rising to the sky as it whistled to warn them. And then it rushed by. engine and cars, in a great smash of sound that stirred the baby in her arms. She saw men standing on the platforms. Women's faces showed in the car windows, serene and idly curious and not a part of Hester's world at all: and afterwards the train was gone, leaving behind the superheated smell of steel and smoke. When the quiet came back it was lonelier than before. She watched that line of cars until it had dwindled to a faint point in the far sage. Then turned back to the wagon.

It was then almost twelve. The children came up, hot and weary and full of excitement. Young Tom said: "The school is right in town. They don't have to walk at all. It's right next to the houses. Why don't they have to walk three miles like us?" And May said. "I saw a china doll with real clothes and painted eyelashes. Can I have a china dol?"

Hester changed the baby on the wagon's seat. She said: "Walking is good for people, Tom. Why should you expect a doll now, May? Christmas is the time. Maybe Christmas we'll remember."

"Well. I'm hungry."

"Wait till your father comes." said Hester.

When he turned in from the street, later, she knew something was wrong. He was always a deliberate man, not much given to smiling. But he walked with his shoulders down and when he came up he only said: "I suppose we ought to eat." He didn't look directly at her. He had his own strong pride and she knew this wasn't like him—to stand by the wagon's wheel, so oddly watching his children. She reached under the seat for the box of sandwiches and the cups and the jug of cold coffee. She said: "What did he say. Joe?"

He had his own strong pride and she knew this wasn't

like him—to stand by the wagon's wheel, so oddly

watching his children. She said: "What did he say. Joe?"

"Why, nothing yet. He said come back at two. He wanted to think about it."

She murmured, "It won't hurt us to wait," and laid out the sandwiches. They sat on the shaded ground and ate, the children with a quick, starved impatience, with an excited and aimless talk. Joe Blount looked at them carefully. "What was it you saw in the restaurant, sonny?"

"It smelled nice." said young May. "The smell came out the door."

Joe Blount cleared his throat. "Don't stop like that in front of the restaurant again."

"Can we go now? Can we go down by the depot?"

"You hold May's hand," said Blount, and watched them leave. He sat crosslegged before his wife, his big hands idle, his expression unstirred. The sandwich, which was salted bacon grease spread on Hester's potato bread, lay before him. "Ain't done enough thus morning to be hungry," he said.

"I know."

They were never much at talking. Sometimes at night, before bedtime, they sat by the kitchen table, and spoke of things to be done and things they might like to do. But they were humble people and the years had made them shy of asking too much. And now there wasn't much to say. She knew that he had been turned down. She knew that at two o'clock he would go and come back, empty handed. Until then she wouldn't speak of it, and neither would he. And she was thinking with a woman's realism of what lay before them. They had nothing except this team and wagon and two cows standing unfed in the barn lot. Going back to Christmas Creek now would be going back only to pack up and leave. For they had delayed asking for this loan until the last sack of flour in the storehouse had been emptied.

He said: "I been thinking. Not much to do on the ranch this fall. I ought to get a little outside work."

"Maybe you should."

"Fact is, I've tried a few places. Kind of quiet. But I can look around some more."

She said: "I'll wait here."

He got up, a rangy, spare man who found it hard to be idle. He looked at her carefully and his voice didn't reveal anything. "If I were you I don't believe I'd order anything at the stores until I come back."

SHE watched the way he looked out into the smoky

horizon, the way he held his shoulders. When he turned

away, not meeting his eyes, her lips made a sweet line

across her dark face, a softly maternal expression showing.

She said, "Joe," and waited until he turned. "Joe, we'll

always get along."

He went away again, around the comer of the Cattle King. She shifted her position on the wagon's seat, her hand gently patting the baby who was a little cross from the heat. One by one she went over the list of necessary things in her mind, and one by one erased them. It was hard to think of little May without a ribbon bow in her hair, without a good dress. Boys could wear old clothes, as long as they were warm; but a girl, a pretty girl, needed the touch of niceness. It was hard to be poor.

COMING out of the bank at noon, Lane McKercher looked

into the corral space and saw the Blounts eating their

lunch under the locust tree. He turned down Arapahoe

street, walking through the comforting shade of the poplars

to the big square house at the end of the lane. A picket

fence ran its neat white line all around the place and a

gilt weather vane on the top of the roof flashed in the

sun, pointing west, whence long ago the last wind had come.

At dinner hour his boy took care of the bank and so he

ate his meal with the housekeeper in a dining-room, whose

shades had been tightly drawn—the heavy midday meal

of a man who had developed his hunger and his physique from

early days on the range. Afterwards he walked to the living

room couch and lay down with a paper over his face for the

customary nap.

A single fly made a racket in the deep quiet, but it was not this that kept him from sleeping. In some obscure manner the shape of Joe Blount came before him—the long, patient and work-stiffened shape of a man whose eyes had been so blue and so calm in face of refusal. Well, there had been something behind those eyes for a moment, and then it had passed away, eluding McKercher's sharp glance.

They were mostly all patient ones and seldom-speaking—these men that came off the deep desert. A hard life had made them that way, as McKercher knew, who had shared that life himself. Blount was no different from the others and many times McKercher had refused these others, without afterthoughts. It was some other thing that kept his mind on Blount. Not knowing why, he lay quietly on the couch, trying to find the reason. The country, he told himself, was cattle country, and those who tried to dry farm it were bound to fail. He had seen them fail, year after year. They took their wagons and their families out toward Christmas Creek, and presently they came back with nothing left. With their wives sitting in the wagons, old from work, with their children long and thin from lack of food.

They had always failed and always would. Blount was a good man, but so were most of the rest. Why should he be thinking of Joe Blount?

HE rose at one o'clock, feeling the heat and feeling his

age; and washed his hands and face with good cold water.

Lighting a cigar he strolled back down Arapahoe and went

into the saloon, though not to drink.

"Nick," he said, "Joe Blount been in for a drink yet?"

The saloon keeper looked up from an empty poker table. "No," he said.

McKercher went out, crossing to Billy Saxton's feed store.

"You know Joe Blount well?"

"Yes, he's all right. Used to ride for Hat. He was in here a while back."

"To buy feed?"

"No, he wanted to haul wood for me."

McKercher went back up the street towards the bank. Jim Benbow was coming down the road from the Two Dance hills, kicking a long streamer of dust behind. Joe Blount came out of the stable and turned over towards the Cattle King, waiting for Benbow.

In the bank, McKercher said to his son: "All right, you go eat," and sat down at his pine desk.

He sat quite still at the desk, stern with himself because he could not recall why he kept thinking of Joe Blount. Men were everything to McKercher who watched them pass along this street year in and year out, studied them with his sharp eyes and made his judgments concerning them. If there were something in a man, it had to come out. And what was it in Joe Blount he couldn't name?

Blount met Jim Benbow on the corner of the Cattle King. He shook Benbow's hand, warmed and pleased by the tall cattleman's smile of recognition.

Benbow said: "Been a long time since I saw you. How's Christmas Creek, Joe?"

"Fine—just fine. You're lookin' good. You don't get old."

"Well, let's go have a little smile on that."

"Why, thanks, no. I was wonderin'. It's pretty quiet on my place right now. Not much to do till spring. You need a man?"

Benbow shook his head. "Not a thing doing, Joe. Sorry."

"Of course—of course," murmured Blount. "I didn't figure there would be."

He stood against the Cattle King's low porch rail after Benbow had gone down the street, his glance lifted and fixed on the smoky light of the desert beyond town. He was quickly thinking of places that might be open for a man, and knew there were none in town and none on the range. This was the slack season of the year. The children were over in front of the grocery store, stopped by its door, hand in hand and their round, dark cheeks lifted and still. Blount swung around, cutting them out of his sight.

SUDDENLY, Ben Drury came out of the courthouse and

passed Blount, removing his cigar and speaking, and

replacing the cigar again. Its smell was like acid biting

at Blount's jaw corners and suddenly he faced the bank with

the odd and terrible despair of a man who had reached the

end of hope; and a strange thought came to him, which was

that the doors of that bank were wide open and money lay on

the counter inside for the taking. He stood very still, his

head down, and after a while he thought: "An unseemly thing

for a man to hold in his head."

IT was two o'clock then and he turned, going towards

the bank with his legs springing as he walked and all his

muscles loose. In the quietness of the room his boots

dragged up odd sound. He stood by Lane McKercher's desk,

waiting without any show of expression; a big, bronzed man

with blue eyes and eyebrows bleached white by strong sun.

He knew what McKercher would say.

McKercher said, slowly and with an odd trace of irritation: "Joe, you're wasting your time on Christmas Creek. And you'd waste the loan."

Blount said, mildly and courteously: "I can understand your view. Don't blame you for not loanin' without security." He looked over McKercher's head, his glance going through the window to the far strip of horizon. "Kind of difficult to give up a thing," he mused. "I figured to get away from ridin' for other folks and ride for myself. Well, that was why we went to Christmas Creek. Maybe a place the kids could have later. Man wants his children to have somethin', better than he had."

"Not on Christmas Creek," said McKercher.

"Maybe, maybe not," said Blount. "Bad luck don't last forever." Then he said: "Well. I shouldn't be talkin'. I thank you for your time." He put on his hat; and his big hand moved up across his shirt, to the pocket there—and dropped away. He turned to the door.

"Hold on," said Lane. "Hold on a minute." He waited till Blount came back to the desk. He opened the desk's drawer and pulled out a can of cigars, holding them up. "Smoke?"

There was a long delay, and it was strange to see the way Joe Blount looked at the cigars, with his lips closely together. He said, his voice dragging on the words, "I guess not, but thanks."

Lane McKercher looked down at the desk, his expression breaking out of its maintained strictness. The things in a man had to come out, and he knew now why Joe Blount had stayed so long in his mind. It made him look up. "I have been considering this. It won't ever be a matter of luck on Christmas Creek. It's a matter of water. When I passed the feed store to-day I noticed a second-hand windmill in the back. It will do. You get hold of Plummer Bodry and find out his price for driving you a well. I never stake a man unless I stake him right. We will figure the three hundred, and whatever it takes to put up a tank and windmill. When you buy your supplies to-day, just say you've got credit here."

"Why, now—" began Joe Blount in his slow, soft voice, "I—"

But Lane McKercher said to his son, just coming back from lunch: "I want you to bring your ledger over here." He kept on talking and Joe Blount, feeling pushed out, turned and left the bank.

McKercher's son came over. "Made that loan after all. Why?"

McKercher said only:"He's a good man. Bob." But he knew the real reason. A man that smoked always carried his tobacco in his shirt pocket. Blount had kept reaching, out of habit, for something that wasn't there. Well, a man like Blount loved this one small comfort and never went without it unless actually destitute. But Blount wouldn't admit it and had been too proud to take a free cigar. Men were everything—and the qualities in them came out sooner or later, as with Blount. A windmill and water was a good risk with a fellow like that.

Hester watched him cross the square and come towards her, walking slowly, with his shoulders squared. She patted the baby's back and gently rocked it and wondered at the change. When he came up, he said, casually: "I'll hitch and drive around to the store so we can load the stuff you buy."

She watched him carefully, so curious to know how it had happened. But she only said:

"We'll get along."

He was smiling then, he who seldom smiled. "I guess you need a few things for yourself. We can spare something for that."

"Only a dress and some ribbon, for May. A girl needs something nice." She paused, and afterwards added, because she knew how real his need was. "Joe, you buy yourself some tobacco."

He let out a long, long breath. "I believe I will," he said. They stood this way, both gently smiling. They needed no talk to explain anything to each other. Hardship and trouble had drawn them so close together that words were unnecessary. So they were silent, remembering so much, and understanding so much, and still smiling. Presently he turned to hitch up.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.