RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

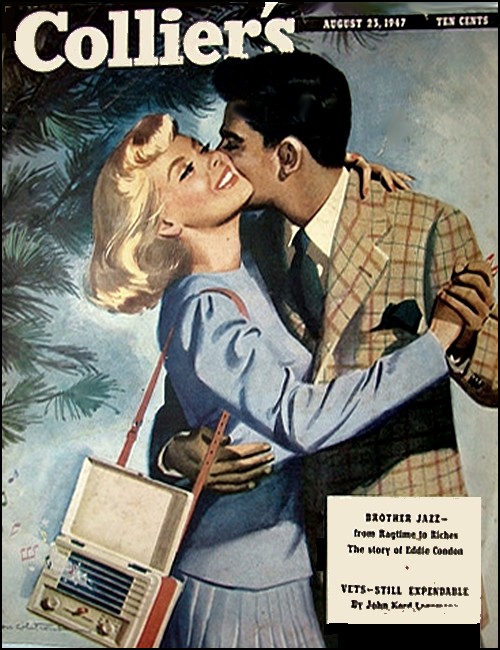

Collier's, 12 August 1947, with "Affair's End"

AROUND quitting time of this very hot day the five executives of Traung Company, each in his narrow office behind the glass partition at the end of the big room, began to remind Margaret of five shop-window models slowly losing shape in the heat. Jim Daniels lay deep in his chair, with his feet on the desk, and his face, with its expression of ruffled wonder, turned toward the ceiling; he had not stirred for at least five minutes. Gordon McVeigh, in the adjoining office, was talking over the phone, but his glance came across the big room to her with its private "You-know-what-I'm-thinking" expression. She'd have to tell him he could never hope to be secretive in an office filled with women; they were like ants with supersensitive antennae ceaselessly waving across the air to detect the slightest emotional change.

She lifted her copy from the typewriter, rolled in a new sheet and saw Jim Daniels rise impatiently from his chair and walk out to the water cooler. He put his back to the room while he drank and he stood at the window to look across the rooftops of town toward the hills. His neck was brown—layer upon layer of brown—and the backs of his hands were the shade of an old saddle. He wore a coat almost too tight for his shoulders, an old and favorite coat he no doubt hated to give up, and he stood with his hands in his pockets and seemed once more lost in his thinking. He was the sales manager, returned after a three-year absence, and it was clear to her that he was having difficulty locking himself back into this particular prison.

He was single and thirty. Margaret wondered if he understood how important those two facts were to the women of this office, how they secretly searched him, and weighed his casual words and gestures, and matched themselves with him, and matched him with others, and tried to detect in him some preference for one of them, until all this was a mass of cobweb cords around him. Probably he didn't, though men had many techniques, one of which was to pretend they knew utterly nothing about women. He liked to play the punchboards in the lobby, he smoked something called Old Nestor, and one of the girls of the office had seen him coming out of a shop with an outboard motor in his hands; he had been dressed in a sweat shirt and faded overalls.

She thought these things while she typed. She felt damp and fretful and unbecoming; a small ache in the center of her back made her lift her shoulders and she discovered that Jim Daniels had turned from the window and was watching her. She gave him her automatic courtesy smile and put her eyes on her copy. It was a curious thing; she typed for the better part of ten seconds and began to feel the sensation running over her, the delayed shock, the growing strangeness, the rough sudden piling up of something that was like fear or excitement. She ignored him but she had his image in the corner of her vision and when he left the water cooler and walked toward her the sensation gathered in her again.

He stopped at the corner of her desk, his hands still in his pockets. She noticed the flakes of hazel in his otherwise brown eyes, the soberness on his face, the small pressures around his mouth. Impulse hadn't brought him here, she thought; he had been thinking about her.

"This," he said, "is one hell of a day."

"What's wrong?"

"That office was built for an Indian sweat bath."

"It's just summer," she said.

"It's just a lot of things."

"You'll get back into the swing of it again. It takes a little time."

"There's not that much time, Margaret."

He watched her with his quiet insistence; his intention was a message coming out of him to her, and when she identified it she felt the plain sensation of fear. He must have noticed it on her face, for he checked something he quite clearly had intended to say and walked back to his office.

A small guilt went through her and it was a hard thing not to look toward Gordon McVeigh's office. He had seen this. Everybody had seen it. It was nothing, of course, nothing at all. She finished her letters, closed her book, and, at five o'clock left the building, walking the twelve blocks to her apartment. She put a potato in the oven to bake while she took her shower.

GORDON came at about eight to take her for a ride. He looked relaxed, in good humor; he took good care of himself and it was a matter of pride with him to maintain an even disposition, to accept both good and bad luck with something of a sportsman's indifference. They drove out to the Butte, followed the looping road to the summit, and parked with the auto faced outward toward the town six hundred feet below. Long dotted lines of lights marked the crisscross streets; the over-town area was a solid glow, with a searchlight idly swinging back and forth to scan the starred sky. A small wind came through the windows. She kicked off her shoes and rested back on the seat. Gordon bent over and kissed her and withdrew, letting well enough alone on a night such as this. He had nice judgment.

"Hot in your cubbyhole today?" she asked.

"I sweated off two pounds."

"You don't need to lose weight," she told him.

They were comfortable with each other, never under the strain of making talk. He took her hand and held it with the gentle way of a man wanting to savor the pleasantness of her nearness and yet not wanting to force it. She sat quite still and the strange vague thing which was not quite terror jumped unexplainably through her. She was thinking of Jim Daniels, not of Gordon.

She said, "Jim seems to be having a hard time."

"He's changed since he's been away," Gordon said. That was a brevity she understood, for Gordon's kind of man was smooth and casual and never out of key. He didn't like Daniels, who could be rough and blunt, and cared nothing for finesse. Yet he would make no comment; during all their engagement he never had become possessive. She closed her eyes and, with the touch of Gordon's hand on her hand, she tried unsuccessfully to put Jim Daniels out of her mind. It was as though she stood in a wide field and watched a black cloud rolling toward her so swiftly that she could not run; it came against her, and its raw, windy blackness surrounded her and she cringed and yet felt strong.

Gordon said, "You're tired tonight."

"Yes."

He switched on the engine and turned home. When he brought the car to the front of the apartment he bent toward her and waited for her face to come around. She delayed that turning for the briefest of moments, which was a thing she had never done before. She was sorry for it and knew he had sensed it as he bent to kiss her; the kiss was one of those perfunctory things which had no magic in it and when she got out of the car she had the depressing thought that there never would be magic any more for them. He said, "See you tomorrow."

The air within the apartment was a stagnant pool of unpleasant odors. She undressed, pulled a sheet over her, snapped out the reading light and stared into the darkness. She had been so pleased with the sort of life she'd arranged for herself. How could it be that she, never wanting more than she had, and never knowing there could be more, now felt the keenest regret for an excitement she now understood she had missed? She knew nothing about Jim Daniels, nevertheless he had touched her with his discontent, tearing her own illusion of contentment apart.

She was motionless and uncomfortable and seemed to run a temperature. She had lost her security, she had lost her way and was confused. There was a feeling in her—such a strange, chaotic and eager feeling—that some great thing was to happen; yet her mind, always practical, warned her that this was only an illusion. People got tired, even of security and pleasant routines; they rebelled and dreamed of a world full of wonders. But they always came back to what they had. She told herself this, but couldn't make herself believe it. Her thoughts were restless and vivid; heated images flashed through her mind. Her body felt heavy and strange. She was afraid of herself.

SHE woke with excitement, she sang a little in her shower, she brought a gay mood to the office. It was as if she were living on her toes, looking forward; she was happier than she remembered being in a long while, and now, to keep her eyes on Jim, she found herself going through those little evasions and subterfuges that other women used on other men. He was restless throughout the morning, he made his frequent trips to the water cooler and she sensed—because she wanted to sense it—that he was actually aware of her. But he ignored her, and as the afternoon wore on, her feeling of some good thing about to happen wore away and she grew irritable at him and at herself. Indecision rocked her back and forth; she thought herself foolish and inconstant and she decided she had misjudged him entirely yesterday; he wasn't interested ia her....

Shortly before five he came to the water cooler again and paused there for his drink, and again looked through the window with his abstracted manner; and then with a brusque swing he left the window and came directly to her desk. She drew a deep breath, every short-tempered impulse fading before the return of a sweet and keen excitement. She had visualized this scene and had detided how it ought to go. She would be casual, she would go on with her typing for a moment, she would look up to him with her courtesy smile. It didn't go that way. She lifted her head immediately and dropped her hands to her lap, so obviously waiting for him. The smile didn't come; she couldn't bring it to her face.

He tried to keep his voice down, but she noticed the unsteadiness in it: "Would you have dinner with me?"

"Yes."

"Tonight? I could pick you up about six thirty. I know where you live."

"Yes," she said and, knowing the office would be watching this scene, she looked at her copy work with a simulated impatience, hoping he was subtle enough to understand it. He gave her a casual nod and turned away. She bent forward to read what she had typed and for a moment she couldn't bring her attention to it; she had to use her will-power not to look across to Gordon's office. At five she got out ahead of the crowd; she didn't want to meet Gordon.

She had only a half hour in which to bathe, dress, put a comb through her hair and to take care of her nails and face. She worked swiftly, with the coolest of purposes to arouse this man. He was a challenge to her, he put her on guard, he summoned up in her the most powerful desires to please him, to match him, to be equal to whatever danger or goodness he might offer her. It was another hot day, yet she felt no weariness and when the buzzer sounded she went quickly to the door and opened it.

There he stood.

"Would that restaurant out by the river be all right?"

She said, "I'll get my hat," and left him in the doorway while she went into her bedroom. She started to put on the hat before her mirror, then changed her mind and carried it back to the living room and stood in front of him while she adjusted it. She said, "Is it on straight?"

He nodded and watched her with a straight-on inquisitive interest, and she got the strongest feeling then that he was a far quicker man than he seemed—that his mind caught the subtleties. She knew she attracted him and she knew he liked what he saw. He showed it. He took her arm and turned her out of the room and closed the door behind her. "How do you manage to look so well, after such a day?"

"It can be arranged, if it seems desirable."

"That encourages me."

"I have the idea you don't need encouragement."

They got into his car and drove through the town's condensed heat and its heavy, ill-tempered traffic. They turned down to the river road and idled along it, with the cool breeze from the water coming upon them. He said, "The office is a gossip mill. I was afraid I might embarrass you when I stopped at your desk. Did I?"

"No. But if you were bothered about it you could have called me on the phone at home."

He said nothing for a short time. She turned to look at him and noticed he had his attention fixed on the road, that his expression seemed again to take him a long distance away. She had never thought him a handsome man; he was of the rough and direct sort, she guessed, who valued the deed more than the reason and who probably had too much impatience to care for long thoughts. Yet in profile he revealed a trace of uncertainty; he seemed to be both aggressive and doubtful.

"No," he said, "I wanted to do it openly. There's Gordon."

The shock came back and little streamers of fear traced out her nerves; the keen excitement had returned. He had thought about her, and wanted her to know how much he had thought. She looked down at her folded hands and wondered if she were ready for any of this. She sat quite still with her wonder, with her own gentle scheming.

He turned in at the tavern built at the edge of the river and found a table on a porch overlooking the water. The sun had fallen over the hills, the early shadows of the river were changing from a misty lavender to an opal gray along the willows. They ordered, they had wine, they ate.

"This is comfortable, Jim."

"I tried to think of a place you might like," he said. "It's all been carefully planned. I worked, it out at the water cooler."

"Oh," she said. "Then I'll have to ask the usual question. Why me?"

He made a small gesture with his hands, shaping up a thought. He had been quiet, with no great amount of expression on his face. It was, in repose, a hard face to read. Now he relaxed and she saw the beginning of a smile, and the flash of deviltry in his eyes. She said quickly, "No, never mind."

"I don't think there's any answer to this man-and-woman thing," he said. "I turn around, I look at the office, I see you—and then there's nobody else. I've seen many women's hands. They mean nothing. I see yours and everything I've ever thought about women seems to be there, in your hands. What shines out of you and makes me want to cut in on Gordon? What comes across the space between us? Nobody knows, Margaret—but there it is. I feeJ it. I hope you feel it."

"If you hadn't seen me," she said, "there would be another woman somewhere—and you'd see in her everything you wanted to see. You'd just transfer all this to her. There's no such thing as just two people meant for each other, world without end."

"Then you don't feel you and Gordon are the only two people?"

She looked down. She was angry at herself and she avoided the question. "It could be something else, too, Jim. We've nothing to go on. We don't know each other. This—this sort of thing—is much too fast."

THEY said very little else during the meal, but her lifted spirits carried her wonderfully on—the well-being, the impact upon her whetted senses of all the flavors and sounds about her, the healthy thickness of emotion. She was alive, she was hungry, she was gay—knowing nothing of the end of this, and not at this moment caring. They went back to the car and drove idly along the dark roads winding through the hills. They talked in shortest phrases, and long pauses ran on and none of the talk seemed to come from anything that had been said before. They reached a high clear meadow overlooking the city and drove to the edge of it. He said, "Is this all right?"

"Yes."

He snapped off the ignition and headlights and settled back. He got out his cigarettes and offered them to her.

She shook her head, and he put the pack away, forgetting that he had wanted to smoke.

He said, "I'd like to kiss you."

She had looked forward to this, too. She had thought she would sit long still, facing the problem and arguing over it; but there was neither argument nor delay. She turned and met him as he came along the seat; she fitted herself into his arms and raised her mouth and took the stinging shock of the kiss and felt it surge along the receiving channels of her body, and in the single detached place of her mind she heard her inner voice saying: I hope—I hope so much.

She wanted it to go so well—she wanted to think good of this, she wanted him to think good of it. She hung to him, her tissues soaking up the moment; somewhere a solitary warning made its faintest sound in her bead. She tried to ignore it, but the sound kept on and finally she drew away from him.

She touched her hat; she reached for her purse. She murmured, "This gets pretty fundamental."

"Yes."

"I think I'm afraid."

JIM started the car at once and backed around the meadow to come upon the road. She laid her hands in her lap and the glory faded before a doubt, and her thoughts, struggling back to their cool place, gave rise to a quick self-hatred. She was shallow, she was cheap. On their first meeting she had waited to be kissed, knowing nothing of what was in his mind, knowing nothing of her own lasting desires. She had been greedy and had let it sweep her away; she who had scorned the casual affairs other women sometimes talked about now found her own standards falling apart. She was angry at him for the easy way he had asked for his kiss, and at her own readiness to give it. She was shocked by her eagerness, and by the discontented wanting he left within her.

She had these thoughts all the way home; she was locked silently within herself. When he stopped the car before the apartment she opened the door.

He said, "You know, of course, I'm trying to break it up between you and Gordon."

"You're doing all right," she said. "But what do you think about? Only this sort of a thing? I mean—who does the work, who worries over the world, who believes in the things in the copybooks? Is this all—just you and I trying to fill ourselves with something for one night, trying to pretend nothing else matters ever, and that this is all rtght because it's us?—And that it will go on forever—one sensation after another, one delight after another, until we're dead?"

He said, "There's time later for all the tears you and I are going to shed."

"You said there wasn't time enough for anything."

"Tonight's been short, hasn't it? Any happiness is short. We're afraid of it. We think there's something wrong with it."

"Is this happiness? There must be more to it than this."

"Why do we always ask questions when it comes? Why can't we take it as it is and believe in it?"

She said, "Your mouth—there's lipstick on it," and left the car.

She brewed herself a cup of coffee and got ready for bed, and sat on the edge of her bed and drank her coffee. The phone rang. She let it ring, knowing it would be Gordon; she didn't want to hear his voice now. She put aside the coffee cup, rolled into bed and turned out the light. She tried to bring Gordon close to her. She summoned all his good qualities and she searched him for those things which had meant much to her—so much that she had been willing to marry him. But he didn't march out of the growing mist; he was unreal, he was fading, he lost force to her and became only another man. Quite unexpectedly she found her eyes wet; she had to tell him, she had to hurt him.

But what was to be said? She lay on the bed with tremendous things unlocked and ungovernable within her, feeling her hopes and her loyalties swinging toward a man of whom she knew so little. He had promised her nothing and she hadn't asked for anything. Lying with these strange new anarchies in her head and these new pains running through her— pains that frightened her because she waited for them and was proud of them —she wondered at herself and didn't know herself.

Gordon came to her desk somewhat before twelve. "Lunch?"

"Where?"

"I'll meet you at the Dorchester in twenty minutes."

He was in the lobby waiting for her with his smile and his nice courtesy, but there was difference enough in him to be noticeable to her. She knew he felt something was wrong. They found a table in the middle of the large and crowded, noisy dining room. She noticed how neat and how precise he was in his dress, and found this a less admirable trait than it had seemed before. His mouth was smaller than Jim's, his whole face was gentler and more considerate, but when she looked at the lines around his eyes and lips, she thought she saw a dryness of sentiment, which caused her to wonder if her old loyalty to him had made her blind, or if her new loyalty to Jim made her unkind.

He said, "You look nice. What are we eating?"

They ordered and they went on with small, fencing talk. He had something to say but he waited for her to create the opportunity for him to say it. He liked smoothness, he hated to press, he had a deep feeling against immoderate display. But when he saw no easy opening, he asked his question direct:

"Is it Daniels?"

"I don't know. But it's us anyhow. I mean, for us nothing's possible now."

The food came and the waiter hovered over them a moment and went away. Gordon said, "Would you like some of this sauce on that salad?"

"No."

He said, "When did it happen?"

"Last night."

"You were out with him last night, I suppose. Could I say something, Margaret? Your conscience isn't hurting you for anything that happened, is it? If that's all it is, I don't mind. Well, I mind, but people make mistakes."

"I don't think I have a conscience."

"You've got a very good conscience," he said, with a degree of sharpness.

"I don't know a thing about him," she said, "yet if I never saw him again you and I would still be wrong for each other."

"You're entirely certain?"

"Yes. You know I'm not impulsive."

He said, "This isn't a good meal—not at all a good meal." He caught the waiter's eye and got the check and paid it. He looked over at her, much too proud to wear his feelings openly. "I'm sorry. Nobody knows about those things, do they? Is there anything I could do about it?"

"I'm so terribly sorry."

"No," he said, "I don't think you are. This thing fills you up so much you've really got no room in you to be actually sorry for me." He was tired and restless and he gave her a critical glance, trying to understand her. "Everything seemed fine," he said. "It just went on as far as I could see. It would have been wonderful." He made several small lines on the tablecloth with his thumbnail and stared at them. "How do you know you love him?"

"I don't know."

"Then what have you got?"

"I don't know that either—but it's something we didn't have."

"You're sure it's good?"

"No," she said. "I'm sure of nothing."

He rose and drew back her chair. Walking to the lobby with him she knew he would never again quite feel the full trust he once had had in her. She had meant certain nice things to him, but this raw change had come upon her and he disliked it and drew back from it. She thought: I wish it would come to him—then he'd know. She stopped in the lobby and quite unexpectedly she got an impression from him that gave her self-confidence and took away from her the feeling of being adrift. It was such a brief thing, but in that flickering of a moment she saw on his face a preview of what he would be when old—that smiling, courteous expression of a man looking upon a world he didn't understand, feeling no heat, remote from passions he never had experienced. She turned from him quickly.

She walked up the stairs to the mezzanine and along it toward the powder room. Women sat on the mezzanine lounge chairs, alone or in pairs, and as she went by them she looked at them with her deep-stirred curiosity. For whom were they waiting and what did they want—and were they strong, or weak, and what price did they put on themselves, and how lonely were tbey, and did they dream, or simply sit as unlighted candles, and were they afraid, of what they were, or did they wait in open rebellion for the first man's appreciative eye?

There were two girls in the powder room, and one of them had taken too many cocktails. She was a pretty girl with a milky skin and a soft face that would soon be fat. She stood by the long mirror, slightly swaying, and she stared at herself and cried in small whimpering gusts. The other girl was politely exasperated. "My God, Betty, put a cold towel on your face. I can't take you home this way."

Margaret got out her compact and lipstick; she watched the crying girl with her deepest interest.

The crying girl said, "I don't care if I don't go home."

"Yes, you do," the other girl retorted. "George will say I got you into this and he'll give me hell."

"The apartment's stinkin' hot," said the crying girl, "and there's nothing to do and all I've got to look forward to is cook dinner, and he'll come home tired and if I want to go out he'll crab at me, and we'll go to bed and lie there and hate each other. Don't do it—don't ever do it."

"Put a cold towel on your face."

"I mean it. A girl traps herself. I'll be old and sloppy in a couple years. I thought it would be wonderful. Well, it's not. You'll get fooled too. Love at first sight—you know there's no such thing. You know what fools you, don't you? Don't let it—don't ever let it."

"You're a tramp. Get yourself together. I wish I'd never brought you."

"I'm not a tramp."

"You're a tramp. Put a cold towel on your face."

Margaret left the room. It was such a silly scene, this girl and her crying jag. But it wasn't really silly. Actually it was a tragedy.

SHE was back in the office promptly at one and worked steadily at her desk through the afternoon and had no impulse to look toward Gordon's office; she whose thoughts had been so loyal to him, who had waited for his glance, who had thought of him possessively and had wanted to be thought of by him possessively, no longer cared. That allegiance was broken. She found herself wanting to look toward Jim's office window, the impulse angered her and she was glad to go home at five o'clock.

IN her apartment, cooking supper, she wondered if a woman were a magnet swinging toward the strongest iron. That was a hard thing to believe, for it meant that no woman would ever be fixed but would always be swinging. She ate her meal, both legs folded beneath her on the alcove seat; she was loose and sloppy in her house-coat and she felt free. Well, it was more than freedom from a bond; it was more like a freedom to choose, to be herself. It was strange what self-respect came out of this break. She didn't need Gordon and maybe—and she thought of it with a livelier interest—she didn't need Jim Daniels. The little crying girl could be right. It could be a trap that a woman walked into because she dreamed that passion would bring every other necessary thing with it.

She washed and put away the dishes. She walked idly around the apartment, picking up things and putting them away. She looked at her clothes in the closet, she washed out a pair of stockings, she found a magazine and settled herself into the stuffed chair. She tried to interest herself in the magazine but presently she became aware of the street noises rising to the window and of the loudness of the electric clock's ticking. She laid aside the magazine and looked about the room and suddenly fear went through her with its painful sharpness. She wasn't free. She couldn't be free. She was tense, she was waiting for the phone to ring.

It was the house buzzer that rang. She walked to the wall and lifted the receiver and heard Jim's voice come over the line with its fuzzy unnaturalness. "I took a chance," he said. "Come for a ride?"

She said, "Wait ten minutes and come up."

She was excited again and the same rapid scheming came to her; she dressed, she touched up her hair and her lips. She stood before the mirror and stared closely at herself as she made her small last changes. She walked to the middle of the room and stood there with so many puzzled, candid thoughts running back and forth through her head. I'm confused, she thought. I've lost my way. How can I know what it is I'm going through? Does anybody ever know?

She opened the door for him when he knocked. He stood in the hall and seemed something like a stranger who doubted he was at the right address. He gave her a close glance, and for a moment he reminded her of herself—the same need in him, the same rebellion, the same wonder. He passed her and stopped in the room and looked around. His voice was entirely matter-of-fact. "It's a nice place."

"Sit down."

"I thought," he said, "we might take a ride. It will be cool."

"We had a ride last night."

"Have we got a rule against two rides?" he asked.

"Look," she said, "I don't know you. You make me a terrible woman. You touch me and I break up with another man overnight. I can't help it, but what are we to call that sort of thing? I don't even know what you're after—I don't know if you're honest, if you want me for one day or forever. I don't know, yet I threw over a good man. I don't like myself, Jim, and I don't like you. What can we be proud of? We're just hungry people kicked around by something bigger than we are and it's making fools of us. If you can do this to me now, maybe another man can do it a year from now, and I'll ditch you as I did Gordon. I ought to send you away."

HE watched her with his intent steadiness. An expression moved over his face and lighted his eyes for a moment and he turned and went to the window; he took hold of the cord on the Venetian blind and idly switched the shutters up and down. His back was very broad and he recently had been to a barber, the new edge of his scalp white against the otherwise brownness of his neck. "What are you afraid of?"

"It's too much, too strong. It came too suddenly, it knocked me over. Where are all the nice little things—where's the security—where's the faith we ought to have in each other?"

"You want it proper and right," he said. "You want the copybook rules you asked me about last night."

"Everybody does. Even the wildest people wish they had the copybook rules. We've got to break it up, Jim. You've got to keep away from me. I won't be pulled down into something."

He still had his back to her. He spoke in the slowest and gentlest way: "I want the same things, Margaret. I want them right. Everybody walks along in the dark. It's like a black night. We bump into one another and slide by. Nobody sees anybody. Then I touch you and something warns me to reach out and I lose you." He turned around. "How many trips do you think I took to the water cooler before I had will enough to come to your desk?"

She looked at him with full surprise rushing through her. "You're—afraid, too?"

"I was," he said. "It came along too fast for me—just as it did for you. We're so skeptical nowadays, so damned educated and smart that we don't believe love comes like that. We think it must be something else and we suspect the worst. We put a funny name to it and we make it look bad."

The answer was so simple, the awareness of it so instant and so complete. She was in his hands and at his mercy; but so was he in her hands and at her mercy. She smiled, she believed in him, she believed in herself. She touched him and was sweetly insolent with her confidence. He was nice—he was decent. She said, "Do you suppose everybody goes through this? Is it the way it always happens?"

"You ought to know. You had Gordon."

"Oh, no," she said. "It wasn't like this—never. It was like a warm quiet day. This—this is pretty rough."

"I know," he said. Then he smiled and he said something that went through her and left its warm glow and bound her to him completely. He said it with the same softness, almost with a reluctance. "It's real. That's what makes us afraid it isn't so. It's the way people dream it ought to be, a way they don't dare believe it will happen for them." He moved toward her and looked down. "Is this all right now, Margaret?"

"Yes." she said. She was impatient to be kissed, to go tumbling along that violent stream again. Everything got so complicated when people tried to tear simple things apart—things as natural as the tide rolling in. He hesitated, so anxious not to be misunderstood; he knew he had shaken her in a way no other man had done; the knowledge of it was so clear in his eyes. He was proud of it, and proud of her, but he was placing a discipline upon himself because of it.

She said, "We can talk about it later, Jim," and made a small motion with her shoulders, restless at his delay, and making it clear that she was waiting. When he put his arms on her she had a swift and passing thought: How wonderful it was to walk through storm, and to come out safely.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.