RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

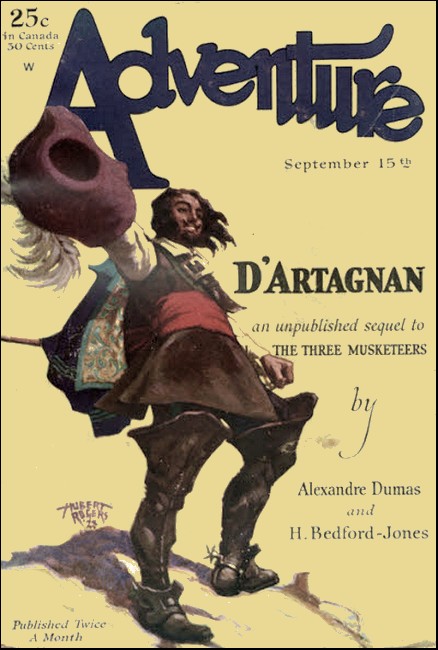

Adventure, 15 September 1928, with "Watch Fires"

THE two officers were lying flat on the ground with the brush parted in front of them, commanding a clear view of the stone house below. They had been in this position—Captain Tench Colvin and his lieutenant, Jennifer Grand—for better than twenty minutes. And still there was no sign of activity from the house and no sign of life in the woods directly behind the house. The captain, hardly more than a youth, stared from beneath the peak of his hat, as immobile as the deadfall beside him. But Grand shifted his legs constantly and complained in bitter tones of the cold.

"Dammee, it comes through my cloak like a knife. I'm paralyzed from the hips down. If you ask my opinion I say there's nobody but the farmer and his wife there. Let's move on with the company."

He was, when compared with the young captain, a man of substantial proportions, big boned rather than fleshy and very deep of chest. His face was of a dark cast with the whiskers giving his lower cheeks a metallic, saturnine expression in no way relieved by eyes which were rather far back in his head. It was a mature and almost crafty countenance, as opposite Captain Colvin's frank and ruddy features as it was possible to be. The latter's gaze never left the house.

"It looks all right," he mused. "But Cornwallis has an advance guard on the Princeton road and it's hardly wise to think they haven't moved beyond Eight Mile Run. A pretty spot for ambush—below us."

"Well, then," cut in Grand, "let's send a few men roundabout to flush the birds, if any. I'm in a devil of a state."

From the deeper thicket to their rear a heavy, groaning voice rose in a singsong version of a camp tune. The young captain struck the cold, sodden earth with his fist and retreated from his Vantage point, rising.

"If I've told that idiot once, I've told him a dozen times about making noise!"

He picked his way carefully back. The lieutenant smiled covertly. A dozen yards brought Colvin to a break in the brush and here, scattered at ease were something like twenty men in the odds and ends of the Continental uniform. All were silent, excepting a short, fat lump of a man with reddish whiskers and a bulbous nose. He sang on until the young captain's words cut him off.

"Stop that noise, Jeffry! You've had your orders."

Jeffry's face turned from saffron to mottled red.

"Man's got to do suthin' t' keep fr'm freezin'."

"Then work your arms or bend your legs," adjured the young captain. '"This is no time to conduct a singing school."

He left the fat one staring vengefully at a grinning circle of companions and rejoined the lieutenant.

"No," said he, taking up Grand's last statement, "I'll not sent out flankers. There's a swamp to the right in those woods. It'd waste another half hour. We've got to get on and make contact. I'm going down myself. If there's trouble I'll signal for support. Meanwhile, you'd better bring the men along the edge of the brush so they cart command it with their fire."

The lieutenant emitted something that passed for assent and rose to his knees. Colvin turned to the right, and still under cover went some distance through the thicket before he broke from it and walked boldly down the hill toward the house.

"I thought I saw a dog there," he mused. "If there were British about the place surely the animal would sound off."

He strode along in seeming carelessness, hat cocked well over one eye and cloak whipped about his lean body by the wind. His blue eyes flashed from the house to the small barn and thence to the dark line of woods. It was a dark, miserable day, even for tempestuous January, and there had been no sun. The undergrowth swayed and the pine trees bent. He approached the house with a hand on the sword and prepared to knock.

IN the brush, Grand still rested on his knees, watching

the young captain. He had made no move to bring the company

up. There was a cheerless, momentary smile on his face as he

muttered:

"Makes a gay figure, the young whippersnapper. Walks across the ground as if it were a ball room. Now when I am captain...."

His smile faded as the ambition nearest his heart arose in his mind. Indeed, there were very few hours during the day Jennifer Grand did not think about that prospective captaincy. When the company had been formed and officers elected he had cherished the hope of becoming its commander until Colvin came upon the scene and with no effort had captured the place. The hurt of that event, though a year old, rankled with all its original bitterness in Grand's mind.

"Oh, I'll admit he makes a fair enough leader," continued the lieutenant, peering between the leaves. "And I'll not deny he's a swordsman of parts. But 'twas my place by rights. I'm an older man. I know tactics as well as he. There'll come a day...."

He pursed his lips shrewdly and a light stirred back in the slaty colored wells. There would come a day when Colvin was promoted, or killed—or captured. Then he would be captain.

His attention was abruptly diverted from Colvin's progress to a point in the woods behind the stone house. A scarlet jacket came suddenly through the brush, preceded by a sword point. Within the space of ten seconds a file of six British scouts followed and deployed behind the house. Colvin, standing at the door could not sec them as they circled the place and advanced with outstretched guns.

The officer, foremost, strode swiftly toward the front. Grand took hold of a twig and squeezed it between his fingers, suppressing the excitement that rose in him. There was yet time for him to sing out a warning to the young captain; time enough to collect the company behind him and charge down the slope. Yet he did neither of these things.

"Now," he muttered, very softly. "Now Captain Colvin, what'll you do?"

Succeeding events moved swiftly. The British officer popped around the corner of the house at the same instant the door opened and the farmer thrust his head out. Colvin, with one foot on the threshold, turned in time to find the Englishman closing in, sword raised. Across the clearing rang a shout. Instantly the farmer flung the door shut in Colvin's face, leaving him with his back to the wall, blade out.

"Ah!" muttered Grand, looking behind.

As yet the members of the company had neither seen nor heard the enemy below them and he turned back to watch the conflict with tight lipped interest.

Colvin had wasted no moment. Surrounded, he plunged directly at the officer and put his sword to work. Grand heard the metal clash, saw the soldiers halt and suspend fire as the duel went on, saw tho English officer give ground under the hard attack. Colvin's body weaved swiftly and the sword point went home. The English officer staggered and fell back into the arms of one of his men.

"Dammee!" muttered Grand, wiping his mouth.

Colvin had turned toward the hill. His shout echoed from one side of the clearing to the other.

"Come on, Pennsylvania!"

There was a sudden confusion of bayonet points and men. Colvin disappeared in the midst of the struggle and Grand, crushing the oak twig in his fingers, swore again. The young captain had leaped clear of the melee and was running across the meadow toward the nearest shelter of trees. Once more his call echoed up the slope.

"Come on, Pennsylvania!"

Grand rose to his feet as the brush crashed behind him. The company swarmed through the underbrush, scattering as they traveled.

"Hold on!" cried Grand, harshly. "Don't leave cover! There's a hundred men concealed behind the house! It's an ambush. Take aim and fire!"

There was a shot below. Colvin seemed to stumble and Grand let out a sharp breath. The next instant the captain had gained the shelter of trees with the British hard in pursuit. The underbrush around Grand shivered with a volley and the smoke curled upward in the gray air. Looking about, he saw himself the focus of inquiring eyes and, drawing his sword, he pushed the brush aside and started down the slope on the run.

"Come on, then! We'll risk it!"

But under his breath he was volubly cursing. Another chance had gone. A treble cry challenged the British detail who, recoiling suddenly from their pursuit of the captain, turned toward the oncoming company.

They tarried for but one round of shots, gave ground and raced for the woods behind the farm house. Colvin came out of the brush on the dead run, brandishing his sword. The Pennsylvanians spread fanwise, swept around the house and charged for the woods, firing as they traveled. Colvin, foremost, threw himself across the path of a retreating Englishman and engaged in a sharp duel. Bayonet and sword rang and clashed. The Englishman lunged forward, missed his mark and struck up with the butt of his weapon. Colvin drove his blade into the man's body and stepped back, a trickle of blood on his face.

"Into the woods!" he shouted. "Spread out and cut them off!"

The Pennsylvanians vanished from the clearing with a great threshing of brush and a scattering of shots. Colvin, breathing hard, swung upon Grand with angry light in his eyes.

"What are you doing here? Go on with your company!"

"Stood by to give you aid," said Grand.

"I need no aid," retorted Colvin. "What made you tarry when I called? We had them neatly caged."

"I thought I saw a large body of troops beyond the trees. I considered it best to wait a moment."

"You had my order, sir!"

Grand's face turned dark.

"Even so, I had to collect the men. We could not come instantly."

"I told you to bring the company up to the clearing's edge. Did you do that?"

"I was on the point of doing it when the scouting party came into view."

The rivulet of blood, coursing down the young captain's cheek made his face seem startlingly white. The blue eyes blazed.

"You had my orders! Do you choose to disobey them?"

"I thought it prudent—" began the lieutenant, more somber than ever.

Colvin spoke coldly. "Let me exercise the prudence for this company. If you are afraid...."

Grand stepped back as if stung; fire gleamed in the slate colored pits.

"Afraid, sir? I shall ask satisfaction for that!"

"You shall have satisfaction," replied the young captain with a singular grimness, "as soon as we reach a peaceful camp. Meanwhile I want my orders obeyed."

He swung on his heel to catch sight of Jeffry limping across the clearing in pursuit of his comrades, almost the only one of the company in sight. Colvin emitted a grunt of displeasure.

"Up to your usual tricks again. Where have you been?"

Jeffry put a wry expression on his ugly face.

"Hurted my foot, Cap'n. Near to broke a toe comin' down the slope."

"You have skulked every engagement this company has been in! If I catch you doing it again I'll lay my sword across your back and send you before a court martial!"

Jeffry spat tobacco and mumbled beneath his breath, straggling off. Lieutenant Grand spoke stiffly.

"He speaks the truth. I saw him stumble and fall."

Jeffry cast an amazed glance over his shoulder and Captain Colvin, sweeping the pair of them at a single glance only nodded and turned away. Grand winked at Jeffry, sheathing his sword.

THE members of the company came out of the woods, singly

and in groups, with here and there a scarlet coated prisoner

walking despondently to the fore. Colvin raised his arm and

sang out.

"Gentlemen, form ranks." Over to the left of the hill, coming from the region of the Trenton-Princeton road a burst of musketry, strong and sustained marked the beginning of a larger engagement of troops. Young Captain Colvin took a stand in front of the forming line with a sudden animation springing to his face. His eyes jumped from man to man.

"A piece of business well done," he commended. "Put those prisoners between the last two files. By the left flank, march!"

They went by the farm house and struck a narrow, overgrown wagon road which wound along the base of the hill they had so recently traveled. It took them across a creek up a steep grade, heavily wooded. The crackle of gun fire became more pronounced and at Colvin's command the column broke into a dog trot. Thus they reached the summit of the slope, threaded their way between stumps and oak clumps and emerged to open country.

Their eminence gave them a good view of the fight as it roiled slowly along the Trenton-Princeton road. Down that road, from the direction of Princeton came a column of British infantry stretching out so formidably that the eye lost the tail of it in a distant copse. Scattered on both sides of the road, taking advantage of every hedge and fence and bush, a body of Americans made a valiant show of stemming the tide. The two sides were not more than three hundred yards apart and the smoke drifted heavily over the ground.

Colvin took his company down the incline, veering somewhat in his course as he saw a mounted officer spurring along a side path to meet him, dodging in and out of protecting groves.

"Must be all of Cornwallis' eight thousand troops behind that advance guard," said the youthful captain, wiping the moisture from his face. He was greatly surprised to find it tinged with red, already having forgotten the musket ball that had grazed his temple. "Coming in an infernal sweat to take Washington. Ah, well! Come on, Pennsylvania!"

The courier wheeled his horse in front of the company.

"Colonel Hand sent me to fetch you from your reconnaissance. He requests you throw your men directly across the Trenton pike and reinforce the rest of your regiment there."

"Done!" cried the captain. "What's the game now?"

"I think," said the courier, ruefully staring at a bullet hole in his coat, "General Washington wants more time to throw up breastworks at Trenton. At any rate, we're to hold Mister Cornwallis back as long as we can. And we've got work cut out for us."

The youthfulness which hitherto had so strongly characterized Captain Colvin vanished in midair. He took the company across the foot of the slope on the dead run, hurdled a fence and skirted the right wing of the American skirmishers. From the corner of his eye he sought to identify the battalions scattered over the ground. Part of Hausegger's German battalion was there, hugging every rock and every tree trunk, firing deliberately. Farther on he met the insignia of Scott's Virginians. Then, coming upon the main pike, he found himself supporting his own regiment—Hand's Pennsylvanians. The singing of the musket balls became more pronounced and as he raced over the ground he saw the British column halt and deploy.

So long had he led this small body of men and so well did they know the business of fighting that a single wave of his arm was enough to send them seemingly helter skelter into the ranks already lying on the ground, behind such cover as they could find. The British were likewise extending their front to make a pitched fight of it. Horses charged down the highway, checked and wheeled. A brass piece swung its mouth on the road; gunners served it. Colvin shouted to the nearest men.

"Take aim at that rammer! Bidwell, drop back with the prisoners!"

The musketry swelled in volume as a prelude to the sudden erupting of the cannon. The ball creamed overhead and buried itself in the earth behind. It was a signal for a concerted advance along the whole of the British front, with bright jackets rising and running onward to the next bit of cover. The very weight of the columns in the rear pressed them irresistibly on and just as irresistibly forced the Americans back. Colvin, looking toward his left, saw a horseman gallop up from the rear, brandishing a sword. Presently a new wave of men sprang out of the earth and came toward the Trenton-Princeton pike to reinforce that weak spot where Colvin had spread his company. They came Indian fashion, dodging, dropping, rising; gaining the line and concentrating their fire on the red jackets across the way.

"Hold 'em, boys!" shouted Colvin. "'Tis the job for us! If they want Trenton, let 'em pay for it!"

The British wave, redoubled, pressed its advantage. Other brass pieces rumbled along the road, swung and belched their warning. Colvin and his men, mingling with the German battalions and the Virginians retreated step by step, contesting the issue with veteran stubbornness. On left and right he saw the line give.

"Eight hundred of us—eight thousand of them," he muttered. "Oh, well. Come on, Pennsylvania!"

The shout was cut short, however, when from the corner of his vision he saw the ungainly Jeffry fire his piece and fall back precipitately, elbowing others aside. The man vanished down the slope of a creek and when Colvin reached the stream he saw Jeffry midway in the ice cold water, fleeing from the field in haste. Colvin drew his pistol and stopped t he fugitive midway in the water.

"Turn back," he commanded.

Jeffry's face went saffron beneath the reddish stubble. There was a quaver of fear in his voice.

"Swear to Gawd, Cap'n, I wa'n't running! My foot, it hurts somethin' turrible an' I wanted to git back a piece an' rest it."

"Come up here," insisted Colvin. "Your foot appears to hurt by spells. You were not limping when you broke from the line." He took the man by the coat and pushed him ahead ungently. "You'll stay by me the rest of this day."

When they surmounted the bank the British tide was sweeping onward with sudden fury. Heavy fire raked the ground and the guns boomed incessantly. Colvin found the whole of Hand's regiment giving way and his own command creeping backward with the rest. So, with an eye alway \ to the craven Jeffry, he marshaled his men. They came again to the creek, forded it and found a temporary halting place. A fresh British regiment marched over the horizon to strengthen the advance guard as it took to the water.

Horses' hoofs pounded on the road behind Colvin's company and the rattling of wheels and the clanking of chains told him of help coming up. Two guns of Forrest's battery swayed drunkenly, careened through ruts and turned their brass muzzles upon the creek. Warning rent the air and a roar smote Colvin's ears. A geyser sprang upward in the creek and in a moment the water ran red. The gunners worked with concentrated fury and all along the line the infantry redoubled their labor. But it could not stem the tide. There were too many British pieces hurrying to the fore. Forrest's guns lost their voice in the sullen mutter that rolled across the valley. As quickly as they came they vanished.

FOR the rest of that gray, cold afternoon and throughout

the five miles that intervened the American skirmishers,

less than eight hundred strong, held the British to a slow

crawl. Colvin, watching his men anxiously, saw one fall here

and another there, each time with sorrow. And always until

the very gates of Trenton were reached he had Jeffry beneath

his eye while the latter puffed and muttered and the sweat

trickled down his ugly face.

"I'll kill the whippersnapper!" he panted, beneath his breath. "No man's a-goin' to stand over me like that! I'll put a bullet in his back, shore as I'm borned!"

The chance, that harsh afternoon, never presented itself. Exhausted and hungry the brigade under Colonel Hand fell into the streets of Trenton town. The early dusk of January descended and the persistent enemy, making a sudden thrust, came to grips. Around Colvin's scanty ranks American guns rattled and groaned; the blue shadows were rent with a momentary cannonade. The red coats came on, making a lane with bayonet points. Curling smoke and night shadows cloaked the scene and men's voices turned savage. Colvin found himself shoulder to shoulder with Jeffry and Grand. Jeffry's throat rattled in fear. There was an explosion in the captain's ear and when he turned he could no longer see the ugly one.

Above the turmoil Colvin heard Hand's command.

"You are being supported, men. Cross the bridge!"

They were at the southern end of the town where Assunpink Creek, spanned by one bridge, intervened between the main body of the American Army and the oncoming British. There was a shot and a clattering of hoofs and a banging of metal. The guns went thundering over first. Colvin, marshalling his men, was caught in the eddy. On the southern bank behind newly made parapets a fresh battery opened against the driving British and fresh muskets took up the challenge. The brigade, utterly spent, stumbled to safety, leaving the battle behind them in other hands. Colvin drew aside to let horsemen by and caught a vague view of his colonel confronting a commanding figure on a sorrel. A serene voice spoke.

"Well done, Colonel Hand. You held them up a day. That was all I asked."

The cannon stormed and a veritable hail of small shot passed the stream. Colvin marching off with his men, heard the attack fail. Repulsed, the British withdrew into the town and calm settled down. Night fell.

JEFFRY, aching in every bone, sat cross-legged before the

camp-fire and dourly listened to his companions idly discuss

their situation.

"I heard a staff officer tell it," asseverated one. "There's five thousand beef eaters acrost that crick, waitin' to tackle us. An' three more regiments at Princeton ready to move."

"Ain't no chance o' them crossin' the creek right in front of our guns," said another. "We got the fords all covered fer three miles up an' down."

"Shore, shore. But who's to stop Cornwallis from turning around our right an' shovin' us plumb into the Delaware? Ain't bright prospects. Wish I knew what old Gineral Washington was aimin' to do. One shore thing, we ain't no match fer the hull British army, considerin' the no-count milisher we got. They never been under fire—an' I reckon it don't take a fortune teller to guess what they'll do when they furst hear a bullet screech." Jeffry shivered, although close to the fire. His body seemed disjointed at the hips, connected only by a steady throbbing in his legs. Added to this misery was a distressing hunger. Less provident than his companions, he had long ago eaten his small rations and now had to watch the more careful bake their potatoes in the embers. He turned on his side, softly cursing. "Hadn't been fer that whippersnapper I'd 'a' got outen this mess. Now I'll be took prisoner, er stuck with one o' them bayonets, like a sucklin' pig. Damn his hide. I'd like t' make him squirm!"

He looked craftily about, hoping that perhaps he might spy a bit of food momentarily unguarded. Failing, he rose to his feet and, groaning aloud, walked away from the fire. He had foraged his supper more than once and felt in the humor to do it again. Down the camp a small distance there was a house and barn. Doubtless their cellar....

His reflections were broken off by a hand reaching out and taking him by the arm. He drew back with a startled grunt. Lieutenant Jennifer Grand's face was within a hand's breadth of his own.

"Out lookin' fer plunder, eh? Better stay close to your own company before our noble captain scorches you again."

Jeffry's temper, never very deeply seated, rose like a rocket.

"Him?" he snarled. "Mebbe he thinks he can lord it over me an' make me mis'able! But I ain't no dog, L'tenant! There's limits an' I fear I'm apt to put a bullet in his back some of these fine days when we git in a fight!"

His thoughts, when spoken, were far too bold and he relapsed to a whine.

"Now, Lieutenant, don't you go carry-in' tales to him. Anyhow, I'm obleeged fer you tellin' him the truth about me stumblin'."

"Truth? Why, you scoundrel, you were skulking."

"Then what'd you side in with me fer?" grumbled Jeffry.

"If you're no friend of his," said Grand softly, "you can be a friend of mine. It's my policy to take care of friends."

Jeffry shifted on one foot, then the other.

"My feet're killin' me," he mumbled.

The lieutenant's statement revolved in his none too nimble mind.

Encouraged, he repeated his threat.

"I'd like to put a bullet in his back some o' these days."

"Tush, man, you're speaking of harsh things. Your courage isn't of that kind."

"No?" grumbled Jeffry, fiercely. "You wait an' see! I ain't a dog!"

Grand's face approached until Jeffry could see the thin line of mouth and the black, unfathomable wells of the eyes. The lieutenant seemed to be seeking something in his pocket and presently Jeffry felt the cold pressure of a coin in his fist.

"There's a half-johanne," said Grand, quietly. "Go back to your fire. If I were captain of the company I'd send you off on a leave of absence and you could stay home as long as you pleased."

He vanished in the dark, leaving Jeffry toiling over the statement. He rubbed the coin with his thumb until at last his body trembled with a mirthless laugh.

"Oh, ain't he clever 'un! If he was cap'n, I c'd go home on leave, huh? Well, there's more'n one way o' makin' him cap'n. Guess I understand him, all right."

Turning, he walked back to his fire, shot a crafty glance around the circle and nursed his hunger....

His guilty conscience startled him again when young Captain Colvin strode into the light with a pair of shoes. But he passed Jeffry without a glance, walking to the one man of the company whose feet were encased in sacking.

"Try these," said he briefly.

"Why, Cap'n," said the man, gratefully, "where'n tarnation d'you find 'em?"

Colvin did not reveal his source of supply. It would have embarrassed him to have said that he had sought them from a farmer's house behind the army and had paid for them out of his own pocket. But, as he walked slowly away, too tired and too disturbed to sleep, he experienced a gust of pride in the duty his company had accomplished that afternoon. Not in any sense a vain man, and often ashamed of his youth, he did not for a moment ascribe any measure of their conduct to his own presence. In fact, the longer he led these men the humbler he felt in being their leader, and the more solicitous was he of their welfare.

A wood detail, dragging fence rails up to the watch fires along the bank of the creek, roused him to a moment's speculation. Across that stream the very finest regiments of the British army commanded by the ablest of English generals slept on their muskets.

It seemed to Colvin that in all the course of desperate circumstances Washington's army had come to the most desperate. It had been maneuvered into a position from which there was, seemingly, no escape save by battle. And though Colvin loved his men and boasted their ability, he knew, with a sinking heart, that there were too few veterans amongst the hodge podge of militia brigades to withstand the redoubtable force in the town.

Wrapping his cloak around him, he swung back to where he had pitched his blankets on the slushy earth. It had turned cold in the last hour and threatened snow.

"Pray God," said ho fervently, "the general finds a way out."

He rolled himself in the blankets and fell into a condition that was not sleep—a kind of weary stupefaction in which he could hear all sounds and feel the increasing coldness as it crept through the blanket.

WHEN he was roused from this misery the blaze beside him

had gone out and, save for the watch fires along the creek,

all was dark. A hand was shaking him and a voice, which

he recognized as that of a staff officer, spoke urgently,

quietly.

"Roll out your men and get them in the column at once. We are moving. Not an unnecessary sound."

Colvin collected his equipment, stumbled over to his company and woke the men. There was a groping, uneasy movement all around them as the various outfits assembled. Everything was confusion. In the road the guns began to move by, wheels wrapped in sacking, horses hoofs muffled. Thus, with a dull thumping and bated epithets they passed through the infantry. The sentries at the creek challenged loudly and the wood details steadily piled fence rails on the watch fires—all as if to mask what took place behind them in the dark. Colvin formed his ranks and ran off the names of his men, one by one.

"Jeffry."

He called twice before a growling response came back. The man, from the sound of his voice, had strayed from the company.

"Stick to the ranks, Jeffry. If you straggle you will be summarily shot by the rear guard. Lieutenant Grand, you will keep the files closed up. No stretching out and absolute silence."

A company trudged past and slopped, not far off. The staff officer came up.

"Ready, Captain Colvin? Follow me."

They marched a hundred yards under the staff officer's guidance and halted in the rear of the column. Presently other troops closed up behind them. A mounted officer rode along the line, speaking anxiously.

"You will conduct yourselves with the utmost silence. It is the command of General Washington. Forward!"

The company moved forward eagerly, brought up against opposition and dropped to a crawl. Gradually the watch fires disappeared and they were engulfed in the woods. Feet slipped on the frozen ground; it had turned ten degrees colder within the hour. Colvin's men grumbled beneath their breath at the slow pace.

"Who's ahead of us?"

"Mercer's brigade."

"Wal, fer Gawd's sake tell 'im to get outen the way an' let summun march!"

Now and then as the column crept around bends of the rutty, forest road they caught sight of a solitary lantern beckoning. Jeffry, limping honestly, barked his shin bones against a stump and let out a stream of vituperation which echoed down the column and brought upon his head sharp reproof. Captain Colvin dropped back.

"Stop that loud talking!"

Jeffry bided his time until Colvin had returned up the column.

"Must think I'm a cussed dog!" he muttered, "Oh, I'll—"

A pressure fell on his arm. Lieutenant Grand's whispered words silenced him.

"Keep your sentiments to yourself, Jeffry."

The column slogged over the road, now striding to close up lost distance, now creeping inch by inch. They halted and suffered the cold in silence; they marched endlessly, seeming lost in the immense pit of darkness. For the most part it was a severely silent column as the night wore on, although here and there was whispered bewilderment which the older men took a delight in mocking.

"Where in God's name are we going? What road is this?"

"What you want to know fer, sonny? Twon't make any diffrence."

"We're crossing a bridge. See, we're swinging again, 'cause I c'n see the lantern."

"Anyhow, we're shore foolin' Mister Cornwallis."

The Army had needed no warning about being quiet the first few miles, so heavy hung the suspense over their heads. Would the British discover their ruse? The longer they traveled the more exultant was the triumph in their weary bodies. Once again they were outmaneuvering England's best.

Jeffry, marching always beside Lieutenant Grand nursed his temper to an incredible state of savagery.

"Oh, Gawd, ain't we goin' to ever stop an' rest? I'm half daid! I'll fix—"

Again there was a pressure on his arm and he retreated to his thoughts. The farther he advanced the more fixed did the determination become to put a bullet in that young whippersnapper if ever the chance presented itself.

Young Captain Colvin, marching beside the front files of the company, fell into a doze. He was conscious always of the steady slip of his feet on the road and of rubbing elbows with the man beside him. But at times his mind was an utter blank and he would be brought back by a sudden collision with the rank in front.

For a time he would remain awake, watching for the lantern ahead, peering at the shadows of the forest as they grew perceptibly grayer. Then the stupor of weariness would again overtake him. In one spell of wakefulness he calculated the time since he last had known six hours of full sleep. It had been better than ten days before.

He was aware that the column began to emerge from its nightlong obscurity. The morning light, filtering through the trees, first revealed the men as indistinct, toiling shapes, humped over, stumbling along the uneven earth. Then, as full light came he saw their faces pinched by cold, drugged by fatigue.

And yet, when the column's pace suddenly increased they found the power to stretch their legs and keep up. Colvin, glancing back, met the sullen, burning eyes of Jeffry. Grand, beside the shirker, had no desire to meet the young captain's face. The man was buried in his own hard thoughts.

THE column left the forest for a breathing spell, crossed

a piece of meadow-land and took up its march in another, less

heavy stand of trees. Colvin saw the brigades stretched out

endlessly to the rear. A splendid figure in buff and blue,

astride a sorrel galloped up the column and stopped at the

head. Presently Mercer's brigade marched on down the road

and vanished in the trees while the rest of the column, now

headed by Hand's brigade, turned to the right and skirted the

trees.

A staff officer rode beside Colvin, commenting on the division:

"We're only two miles from Princeton. Cornwallis left a brigade there under Colonel Mawhood which, if we're fortunate, we'll take. Mercer's going on over to the Princeton-Trenton road and knock down a stone bridge."

"Fair—" began Colvin.

He never finished that sentence. The column came to a halt as a sudden burst of firing echoed through the trees, coming from Mercer's brigade which but a moment before had set out for the Princeton-Trenton road. The rattle of musketry swelled to greater dimensions and a sustained shouting marked the beginning of a good sized fight. The figure in buff and blue whirled on his horse and sent a signal to Colonel Hand, then went speeding through the trees toward the scene of action, cloak flying. Hand galloped back to the column and brandished his sword. Colvin swung his company and led the brigade at a rapid pace into the woods. It was a good hundred yards out into open ground again and upon reaching it the troops paused to view a scene of disaster. Two regiments of British—Mawhood's brigade which had left Princeton that morning to join Cornwallis—were deploying from the road and swarming through an apple orchard, pushing Mercer's brigade in front. The first few volleys had been sanguinary enough, for the ground was littered with the dead and wounded; and as the British bayonets came closer the American troops, most of them green, gave ground and fled. The tide of battle bore them, pell mell hack towards the woods.

Hand launched his troops at the left flank of the British, without a moment's delay. Colvin, deploying his men, saw the splendid figure of Washington riding through Mercer's demoralized ranks, brandishing his sword and calling for them to turn and hold their ground. Midway between his own troops and those of the British he was in the zone of hottest fire with the smoke clouds curling around him. Colvin had a sudden constriction of his throat. Parched voices shouted warning.

There was no prelude to this fight. It came suddenly and waxed to an immediate crescendo. The Pennsylvanians flung themselves on Mawhood's left wing with all the fury at their command. The shock of that encounter rose to the skies and the smoke of musketry swirled like a thick fog, low on the ground. Colvin, racing ahead of his men, met a grenadier with bayonet outstretched. He thrust and parried and lunged until the sweat started from his head and his arm ached.

He beat the gun down and saw the man fall before him while his own saber point turned scarlet. On all sides of him men were at grips, metal banging metal and belated shots bursting here and there. He heard the swift passage of guns not far away and immediately thereafter their sullen booming. The battle seemed to gain strength, to focus around Hand's brigade.

A cry reached Colvin's ear. Turning, he saw Jeffry prone on the ground one hand fending off the menace of a British bayonet. He dashed back with a shout of warning. The English soldier, hearing that cry to his rear, deserted his fallen foe and swung in defense. The scene became the rallying point for both sides. Colvin beat the bayonet aside and stood astride the prostrate Jeffry.

"Come up, man!" he shouted. "Up and try again!"

He had a glimpse of Jeffry's face, dead white beneath the whiskers. A moment later the man had scrambled to his feet, behind the captain. The whirlpool of conflict widened and the Americans, feeling the victory at hand, charged onward. It was the turn of Mawhood's brigade to break ground and flee. Colvin went forward, rallying his men.

Behind, Jeffry was ramming home a charge, sweating profusely and stung to a desperate, defensive courage. His comrades were racing by on all sides and, bringing up his musket, he trailed along, one eye upon Captain Colvin's slim back.

Of a sudden he was aware of some one running beside him and turned to see Grand's face moving with anger.

"Shoot now, you fool!" muttered the lieutenant. "Do it now or I'll see to it you're everlastingly damned!"

With that warning the lieutenant went ahead.

Jeffry was not quick witted and events had moved so swiftly in the last thirty seconds that it left him swimming of mind. But, across all his numb perceptions flashed a streak of gratitude. He looked around him, saw no one free enough to watch him, dropped to his knees, look careful aim and fired. Lieutenant Jennifer Grand, twenty yards in advance, staggered, buckled at the knees and pitched forward, face down. Jeffry managed a dry, panicky gain and stumbled onward to catch up with his comrades. It seemed safer in the van of the battle than alone in the gory background.

AGAIN Washington, "the old fox," had wormed himself out

of danger. The battle of Princeton had been his challenge to

the laggard Cornwallis and, with that blow struck, he moved

swiftly toward the mountainous country of Morris County.

Late that afternoon Tench Colvin, on patrol duty with his

company, saw Cornwallis marching his army in the valley

below—marching back from Trenton toward New York.

He dared not attack Washington's new position and so was

retreating to a safer base.

Calling the roll of his company in his mind, Colvin made note, sadly, that the ranks were thinner by six. Among them were Jennifer Grand and the laggard Jeffry. He turned to one of the survivors.

"Bidwell, did you see anything of Jeffry?"

"Daid," said the man. "I seed him fall jest as the Britishers fired their last volley afore retreatin'."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.