RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

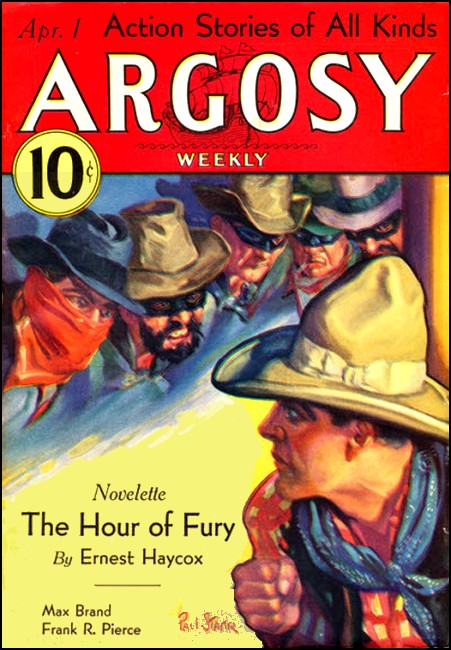

Argosy, 1 April 1933, with "The Hour of Fury"

THE main street of Dug Gulch ran to the very brow of the hill, and the slopes of that pine-swept hill descended gradually a thousand feet to the prairie—to cattle land, running without a flaw into the mists of a tawny and purple-shot horizon.

Coming up the long trail, Dan Smith attained the street and halted there a little while to give his leggy claybank a breather. His glance went back to those distant flats along which he had ridden for five days without a break. The mica glint of dust was refracted from his clothes, and in his eyes, a vivid cobalt against the bronzed breadth of a passive face, lay the weariness of travel and of thought.

It was betrayal, however, for a man to inspect his back trail too closely, and so presently this Dan Smith turned the claybank along the rutted street leading into Dug Gulch. Without appearing to look at all, he saw everything. The town was another mining camp in the pine hills, another double row of raw-wood buildings, flimsily thrown up to seize the profits of those men who were gutting the emerald ravines for gold. He passed assay office, courthouse, store, and saloon, all elbow to elbow. High up on a larger structure ran a vermilion sign: Benezet's Hotel. Out of a blacksmith's shop, anvil echoes sailed with a rending clangor. A row of private houses ran on, butting against the virgin pines, and somewhere in the green cry beyond there arose a halloo and clack of miners working.

Dan Smith cut across the street to a stable and dismounted in the cool half dark. A roustabout rose from a bale of hay.

"Be careful with the water," said Dan Smith, his voice effortlessly gentle. "Hay now and oats later."

He turned out then, carrying his saddlebags, but stopped before the street, and put his broad back to the stable wall. This was strange soil, and the self-protective instincts of a lifetime could not be broken.

Paused there, he made a high, flat shape against the last of the day's sun, a big-boned man possessed by a stolid calm. But his eyes, slightly sad and faintly bitter, raked store and alley and window of this camp in the manner of one who was following an oft-repeated custom.

Crossing the street afterward, he fell into the straggling stream of citizens, drifted as far as the saloon, and there entered. At the bar he asked for his customary drink.

The bartender was a big, blond fellow whose cheeks faintly shone with perspiration. He said nothing as he set up bottle and glass, but his attention remained on Dan Smith for one suspiciously casual moment and slid away. It was a perfect indifference, yet the long-nursed resentment deepened in Dan Smith as he drank and paid for his whiskey. A man's history was like a label to be seen by the world, as permanent as a scar. That was the way of it. The barkeep had judged him, and something would follow that judgment. Once again out in the flow of the crowd, he allowed himself to be carried as far as the hotel.

The game never changes, he mused. Why did I think I could change it?

In the hotel he registered and was told the number of his room. He went up the stairs—slowly, because his weariness was half in his muscles and half in his heart—and followed a dim, musty hall almost to its end. His room was pretty rough, being nothing but four thin walls enclosing a bed and a chair and a bureau. All the sultriness of the day was compressed in it; noise and street dust flowed through the open window. With the hopes of getting some small cross-draught, Dan Smith let the door stand wide, dropped his saddlebags to the chair, and laid himself full length on the bed.

Dug Gulch—two hundred and eight miles from Fort Rock. There was no escaping the past. Five days could not erase it, and now that he had closed his eyes, the image of Fort Rock's street, turned mad and bloody, spread across his inner vision. All motion and all sound returned, more vivid than originally. Ned Canrinus was walking around the corner of the bank. He was saying: "This is the end of it." Then he began firing.

White strips of dust rose out of the hot earth, and another man, rage boiling in his gullet, made a deliberate broad jump through the saloon doors, joining Canrinus. A third gunman opened savagely from behind. Even now, Dan Smith felt the heavy recoil of his own Forty-Four, heard the sound of this gun play crushing against the town walls.

Canrinus fell screaming, and died. The partner beside him became a squalling victim in the deep dust. And that third man, in the rear, quit firing and raced diagonally across Gurdane's vacant lot. Turning, Dan Smith had pinned him mortally to the spot, and afterward the silence was heavier than anything in his memory, broken only by a voice that was his own. He had said: "That's right ... this is the end of it."

An old buffalo gun began to boom at the far end of the street as he walked into the stable. In all Fort Rock, no other soul was visible at the moment. Dan Smith got on his horse and left the town behind. The buffalo gun was the last sound in his ears. Behind it, he knew, was Marshal Drain, furiously fighting three men dead in the silk-yellow dust.

"Was the name Smith?" said a slow, still voice.

Dan Smith opened his eyes. Three men filled his doorway, the foremost nearly broad enough to fill it alone. He was fat and blond and pink of face, and a wicked wisdom of the world flattened the color of his small, unrevealing eyes.

Dan Smith sat up on the edge of the bed. This, he realized, was the aftermath of the barkeep's glance. But Dan only nodded and reached in his pocket for the makings of a cigarette.

"I'm Benezet," said the fat one, and moved on and sat in the chair, releasing his weight to it by cautious degrees.

The other two stood fast by the door.

"Your horse," Benezet went on, in a thready, indifferent tone, "is a beauty. I notice the brand is U Bar, which is Morgan Mountain way. I'm familiar with that territory. Never heard of a Dan Smith being there."

Dan Smith's regard remained inscrutably on the cigarette being formed in his tough fingers. He said, equally indifferent: "My own horse was in bad shape. I came through Morgan Mountain and traded for the claybank."

"What was this other horse's brand?"

"T Y," Dan Smith said gently.

"I know Tom Yount. Never heard of a Dan Smith workin' there."

"Still traveling," Dan Smith murmured. "Another tired horse swapped at the Yount ranch."

Benezet said very softly: "What was the brand of the horse you started with, wherever you started?"

"We won't put that on record, friend."

Benezet looked like some heathen god. All his emotions were hidden behind the sluggish fat. He had a blue handkerchief in his fist, and this he rubbed across his forehead, erasing moisture. "You wear no gun, which lays you wide open to wonder."

"Why wear an overcoat when it doesn't rain?"

"Rain always comes when you got no coat handy." Benezet rolled his head at the door and murmured, "All right, boys."

The two silent men came in, one reaching for Dan Smith's coat lapels and pulling them aside.

"No shoulder holster," said Dan Smith, unresisting.

The second man, searching the saddlebags, turned on Benezet. "A razor and shaving mug, and a box of Forty-Four shells, and a Forty-Four."

"So," Benezet said, merely breathing it. He sat there loosely, legs apart, seeming to suffer from the room's warmth. The fat fist continued to hold the blue handkerchief "I could trace your trail," he said.

"Be sure that you want to," said Dan Smith.

"It might be worth the trouble."

Dan Smith stood up, whereat the two exploring men wheeled alertly. But he remained still, looking down at Benezet's bland, suspicious face. His own blunt features were darker and more turbulent than they had been.

"This game," he said somberly, "never has a different end. I never met you before, but I could lay your story out in ten words. It wouldn't be advisable for you to follow my trail back. What's behind me is over. I closed the door. Don't open it."

Benezet's cheeks never changed, yet the light of his eyes seemed to be of laughter. He pushed himself upright. "Let a man talk," he said. "Always let a man talk. I get you, Smith. More than one sort of man comes up here. It's to my profit to know which is which."

One of the silent henchmen looked a little troubled and spoke. "He might be carrying a star some other place in his clothes."

"Star?" said Dan Smith.

Benezet's little eyes touched his man. He said in a voice as smooth and frigid as ice: "You fool!"

That phrase rapped the sultry silence. It struck the fellow who had been addressed as if it had been a whiplash. All his nerves seemed to recoil.

Benezet rolled his vast shoulders and rocked through the door, blue bandanna dragging from his hand. The others followed. Still in his tracks, Dan Smith listened to the creaking of warped boards, the groaning along the stairway.

"Star?" he said again, and scowled faintly.

The stairs stopped protesting, and then started again. Somebody was advancing slowly, unevenly down the hall, making a great labor out of walking.

Dan Smith turned to the window and pushed the dirt-gray curtains aside on the impulse of a sudden curiosity. Below, Benezet propelled his big bulk saloonward, his two henchmen behind. The blue bandanna hanging from the fat man's fist was ridiculous, but there was nothing ridiculous in the way the flowing stream of miners moved aside to give his gross bulk a right of way.

Dan Smith leaned back from the window and wheeled, feeling more and more irritated. A man wretchedly deformed supported himself by the frame of the doorway, one useless foot hanging six inches from the floor. He was hatless, and his hair, black as jet and coarse as horsehair, matted a heavy skull. Two friendless, cheerless eyes peered sullenly.

"Got anything to give me?" he grunted.

"Why climb the stairs when you could have met me below?" Dan Smith asked.

"A beggar's supposed to do something for what he gets."

Dan Smith found a dollar in his pocket and walked to the cripple. The eyes of the deformed one narrowed on the money, and he took it without comment or thanks. Swaying slightly on his one good foot, he stared at Dan Smith, actual hatred burning in the queer glance. He started away, and then he turned back.

"Next time I ask, throw it on the floor, like the rest do," he said.

"What's your name, friend?"

"A man like me don't need a name." The cripple's brutal lips receded from strong, white teeth. "This camp's busted better men than you, mister. You've been visited by Benezet. It ain't no compliment."

Dan Smith said: "When did the last sheriff or deputy visit this camp?"

The cripple only laughed, a soundless laugh that drew his pitiful cheeks into odd knots. After that he labored down the hall.

Dan Smith drew a deep gust of cigarette smoke into his lungs, expelled it, and for want of something to occupy his strange restlessness, he removed his coat, rolled up his sleeves, and went to the wash basin. There was never any change in the game. It was something timeless, and the end was as fixed as the hours. All long trails led to this.

But the star business is something extra, he thought. What would that he? Alert to the question, he sat on the bed, building a new smoke while his mind cut keenly back and forward. I expect him to consider me an outlaw, he mused. That's the natural thing. But if he thinks I'm an officer—what's he afraid of?

A man ran up the stairs and advanced quickly, pausing and knocking at a door directly across the hall. What Smith saw then was little more than a strained profile and a set of small shoulders on an immaculately dressed body. A woman's voice, eagerly lifting, said: "Wait!"

Directly afterward the door opened, and she stood slim and smiling against the fading daylight from her room. At once pulled out of his thinking, Dan Smith let his attention remain on her. It wasn't often a man saw a woman alive and eager like that, a woman wrapped up as she seemed to be in the dapper figure waiting at the door. There was a gallant tilt to her head, a supple vigor to her body.

"Come in, Clare," she said.

The man's tone was half impatient. "Only a moment. I have a case to try."

There was something more, but the door closed behind them, and their voices began to blend, to interrupt, and to grow more peremptory.

Dan Smith got up, striding the room with a caged restlessness. One phrase from the girl clearly penetrated the panels of the door, somehow desperate.

"But you've got to get yourself out of this mess!"

That was all. The door opened again, and the man closed it strongly behind, and hurried down the hall. What Dan Smith heard next was the one sound to hurt and enrage him beyond all others. The girl was crying, quietly crying.

Damn, thought Dan Smith. Is there nothing but trouble in the world?

He dropped the cigarette and laid his pointed rider's heel on it. He made one more indecisive turn of the room and stopped at his own doorway, the blue of his eyes going dark and deep from the sound of grief. All his quiescent sympathies rose, wiping out weariness, stirring a swift partisan anger. It was like a challenge, that cry. He thought: It's always like this. I never know when to quit.

He took half a dozen paces toward the girl's door. His knuckles fell lightly on the panel, and he heard the crying stop, and her steps come nearer. The door opened. He saw a blaze of hope lighten all the firm, fine features for a moment, and then utterly die. A profound regret went through him. But he stood there, tall and wistfully grave, a young man hungrily whipped to bone and sinew, a quiet sympathy in his look.

"Most of the grief in this world comes from what people do to each other," he said gently. "But it isn't worth tears. Nothing's worth tears."

SHE was watching him, the clear and definite surface of her face terribly sad. But he knew that the cloud of her troubles lay between them, and he spoke again in the same quiet, melody-making voice: "What sort of help do you need?"

The question broke through her preoccupation. He felt the full effect of that taut and grieving glance, and his admiration grew at the sight of her small shoulders so resolutely squared. The light was fast going from the windows of her room, its reflection stealing from the corn-yellow surfaces of her hair, its shadows more somberly pooling across the straight brow.

A small breath disturbed the silence. "What kind of help could you be to me?"

"Anything you need destroyed or broken or torn up," he said, his gentle tone faintly bitter. "What else can a man do? When a woman cries, she may be happy or she may be sad. If it is sadness, something has got beyond her."

She said, curious: "You are the only man ... do you know this town?"

"No.

"Do you know my name, or anything about me?"

"Nothing."

"My name," she said, "is April Surratt. And if you knew this town, you wouldn't offer help. You wouldn't dare."

"You misunderstand men," he said. "Plenty of them will pull away from the pack."

She remained quiet a little while, growing dimmer and dimmer before his eyes.

The stairs began to whine under the pressure of an approaching body. April Surratt retreated into her room.

"The pack?" she asked. "Then you know this town?"

"The game never changes, one town or another."

"It will do you no good to be seen speaking to me." And she shut the door.

Dan Smith returned to his room and lit the lamp. He stood for a moment before the bureau's leprous-spotted mirror. What reflected dimly back only increased the irritation stirring in him like a toxin. That face was old and preoccupied, and all the cheerfulness, all the careless laughter of another day, was gone. At twenty-five, part of him was dead. The reckless desires of life lay flat and thin and starved in their remote places.

Dan Smith turned and circled the cramped room. He laid out on the bureau the few articles from the saddlebags, neatly, as was his habit; and for a moment he held the dull, wooden-butted gun, and felt its solid reassurance. Then, astir with anger, he dropped it.

That's what I'm trying to get away from, isn't it?

Extinguishing the light, he went down the stairs and into a street awash with the shadows flowing like water off the higher hills. The walks were crowded. One by one, the store lights began to shine, through pane and doorway, and to lay golden hurdles across the dust.

Two men passed him rather rapidly, and he heard a sullen, cautious phrase drop. "He'll get free. Benezet will see to it."

At the courthouse a considerable group made loose, semicircular ranks near the entrance. Turning that way, Dan Smith's shrewd thoughts returned to Benezet, and he said inwardly: Why is he afraid of a star?

The sudden odor of burnt coke and singed hoof tissue fell on him, and, as he threw a casual look into the murky depths of the blacksmith shop, a man there—a squat and ugly giant covered by a leather apron—suddenly reared from a water tub and stared back. Surprise spread his jaws apart.

He said: "Dane ...?"

Dan Smith's head shook imperceptibly. He went on.

But the blacksmith, water running from his face into the bare breadth of his chest, abruptly laughed, a suppressed and deeply amused laugh. He said—"Well, now!"—and plunged his face into the tub once more. And the next moment he stood up and stared into the drifting files of men with a sly humor on his burnt cheeks.

Dan Smith went on, faintly scowling. There was something here. All faces were pointing toward the courthouse door, and he felt that the temper of that assembly was like the heat of a covered fire. Curious, he pushed through and on up the steps into a hall guarded by miners, all the way to an open door. Through that door ran the even-pitched and persuasive voice of a man in argument. That voice, Dan Smith thought, was faintly familiar, and he worked his way uncivilly along until he looked across the rows of a seated courtroom audience. There was no jury—only a bald, bullet-headed man sitting behind a high, pine desk, obviously bored. Below him stood the meticulously dressed fellow whom Dan Smith had seen talking with April Surratt, across the hall at the hotel. A lawyer, then, and coming to the end of an argument.

"What kind of evidence is that?" the fellow said. "It has all been circumstantial. No man directly saw Loma Sam's face. No man saw him actually tampering with the sluice box. When surrounded by this party of amateur detectives, he was leaning against a tree, a hundred yards away from the McNeish claim. There is no proof of robbery. I urge you to dismiss the case."

The judge bobbed his head, the flaring wall lamps detailing his white, compressed mouth across a flinty skin. He said: "Stand up."

A man who was extremely thin and slovenly, slowly unfolded himself from a chair.

"You're discharged, Loma," said the judge.

The attorney said carelessly—"Thank you."—and turned to go out.

There was an absolute lack of sound in the courtroom at that moment, a strangely sultry stillness. It was as definite as that to Dan Smith, and it was no less definite, he saw, to the attorney. For that man stopped and pulled back his little shoulders, flashing a swift glance all along the corners of the room, at once calculating and scornful, placing his will against the speechless hostility of the crowd.

Dan Smith's eyes began to narrow, taking in the details of that thin face with its skeptical half smile. He turned on impulse to the nearest watcher. "What is his name?"

The man's answer was throaty. "Clare Durran."

The show was over. The ex-prisoner, Loma Sam, came rapidly out, looking neither to left nor right, and got to the courthouse steps. Deeply interested in this obscure play that was becoming at each step less obscure, Dan Smith followed.

Loma Sam's forward progress ceased at the steps. He stared down at the massed and saturnine faces, and seemed to shrivel. Placed as he was, Dan Smith could observe that crowd's anger. The man, he thought, was acquitted of robbing a sluice box—but he's as good as dead, and he knows it.

Loma Sam moved his thin arms futilely. He threw his heel around, fear bursting in his eyes. And then a curt, unyielding voice said: "Open up and let this man through!"

Dan Smith's alert glance searched the shadows and fell upon a hulking figure, reared against a pillar of the courthouse front—an implacable figure with a great jaw, the pockmarks on his face visible beneath a hat's brim. Loma Sam's nerves grew perceptibly calmer at the sound of that voice. He straightened and walked boldly on into the crowd.

The iron voice at the pillar rose again. "As long as I'm marshal, there will be no lynching. Understand me!"

A heavy, sibilant undertone spread like a runner of wind through the massed miners.

Then another shape came from the courthouse at a rush, passing Dan Smith. The man stopped halfway down the steps, swaying from side to side, the breath gushing in and out of him.

The rustling discontent quickened through the waiting ranks, and a man called up: "McNeish, never mind. Your friends will take care of Loma."

"Who said that?" challenged the figure by the pillar.

McNeish ceased swaying. He was long and mature, a full-bearded man seized by an unsparing anger. He raised a hand into the twilight, shaking it at the pale, premature stars.

"Everybody knows me," he said. "Everybody knows Bob McNeish. I made discovery in this camp. I saw it grow. I saw the houses spring up. I saw the good men come ... and I saw the crooks come. Listen. It's got beyond us! I've been in a lot of camps in my life, and there's always been crooks. But the time always came when the crooks died with the wrath of God on them. I caught Loma Sam flat-footed, with his dirty paws scooping dust out of my sluice. Listen, I'm a patient man, but I tell you, this camp's turned rotten! The leeches have got to go, the hooded scoundrels, the shyster lawyers, and the judge that sits behind the court desk and deals out the orders a certain man in this town gives him." McNeish stopped for a full breath of wind and exploded mightily: "You know that man!"

The man at the pillar said coldly: "This is a little rash, McNeish."

Dan Smith turned his engrossed eyes. An angling beam of light struck out of the courthouse to play on the stiff-jawed fellow with the pitted face who had just spoken. On Clare Durran, too, now standing there, pale yet still clinging tenaciously to his faithless, sardonic smile.

"I'm including crooked marshals, Sullivan!" cried McNeish.

"A little rash," the stiff-jawed man repeated tonelessly.

There was a stirring along the ranks below, and Dan Smith's eyes fell back upon the enormous, seal-fat shape of Benezet. Benezet had come through the crowd, and he paused now in the cleared space at the foot of the steps, unhurried and unmoved, looking up at a McNeish gone dourly silent. One bulky fist, holding a blue bandanna, rose indifferently at McNeish, and the sleepy voice fell flat and very clear.

"Don't be disturbed by little things, Bob."

That was all. McNeish was speechless, beyond words and beyond motion—a thwarted and accusing shape in the swirling dusk. The very presence of Benezet was enough. Something cold emanated from the hulk, to flow into the furnace-hot temper of the crowd, to beat back the virulent anger, to kill talk.

Looking relentlessly on, seeing the edges of the crowd stir and dissolve, Dan Smith silently applauded the stark quality of Benezet's courage. Divorced from the terror and brutality that went with it, such courage was admirable. There was something else in these men—in Benezet and Clare Durran and the pockmarked fellow—as unshakable as the hills. Something bitter and conscienceless and unforgiving.

But the rest of the story was clear now, and, as the crowd broke and milled along the light-streaked street, Dan Smith slowly returned to the hotel, all the details of this last scene deep in his mind, scorched into it by a fire heat. The game never changed!

Two barking explosions rushed out of the adjacent pines, bringing him to a stand.

A man near him whirled and cried: "That's it!" And his face, in the light, was a wicked smear of pleasure.

Dan Smith went on, pulse slow and strong, the reckless flicker of an old feeling in him. That would be Loma Sam, dying out there in the dark, at the hands of Bob McNeish's friends. The game never changed, and it was all clear now. Wherever men dug raw gold, there also gathered the parasites—living on sufferance till their power grew greedy and overwhelming.

This was Benezet's town. Those fat hands grasped it unrelentingly. That covert and unreachable mind schemed over it. Dug Gulch's commoner men tramped through the alternate lanes of brilliance and shadow with the sleepless surveillance of Benezet's desires on them. The game never changed. This was a stage in the life of a crook and in the life of a town.

Another stage will come, he said to himself Why am I here?

Somebody strode rapidly up from behind, came abreast, and fell in step. The stiff jawed marshal's pitted face turned sidewise. He said: "At the next alley, turn into it."

"Power," Dan Smith said gently, "is a light in the far desert, a light leading better men than Benezet to ruin."

"What's that?" the marshal said sharply.

"What's at the other end of the alley?"

"Turn in."

Dan Smith's chuckle was reckless, amused. Never any difference, never a new way. This is just the second step from the barkeep's look.

He turned at the alley, went into the deeper dark, with the marshal close behind. He came to the cluttered back lots of Dug Gulch, to the discarded boxes and littered junk and debris.

The marshal said—"Turn right."—and stumbled into loose wire, and swore. Twenty feet onward, he said: "That door."

A single pencil shaft of light identified the door. Dan Smith found the knob and pressed the door back into a bright, smoky room disturbed by the sounds of a barroom directly beyond a partition.

The marshal came rapidly in, slammed the door. He was surly, displeased.

"Here he is."

Nothing surprised Dan Smith. Benezet sat at a table. The thin- mouthed judge sat there. And Clare Durran, too electric to stay placed, idly paced beside a wall. The two who had guarded Benezet when he came to Dan Smith's room also were here, behind the big man's chair, and at once they were stiffly conscious of Smith's appearance.

Benezet's hands were on the table. He rolled them gently, palms up and palms down. "You've had your look, Smith. Do you get it?"

"It's an old story," Dan Smith said mildly.

"What am I?" Benezet challenged, little eyes very bland.

"What McNeish said you were on the courthouse steps."

"So I run the town?" Benezet said indolently. "I milk it dry? I make the law and support men who rob sluice boxes. ..with the help of just these five gentlemen around me?"

"I said it was an old story," Dan Smith pointed out. "Behind these five men are maybe twenty roughs at your beck, and half a dozen gamblers at your saloon tables. There are the operators of your bawdy houses, as well as the barkeep who looked me over when I hit town."

Clare Durran stopped his pacing and stared, the ironical amusement on that half-handsome, hopeless face dying.

Benezet, however, chuckled, which was merely a rumbling disturbance in his chest. "You're shrewd," he admitted. "I knew it the moment I scanned you. I'm familiar with your type, friend Smith. Give me credit for knowing the different kinds of men. You've got a mind beneath that poker face. You're slow moving, but you're set on springs. You can use a gun, friend Smith. That's your number."

"Now," Dan Smith said, "sell me your bill of goods."

Benezet said: "You're coming in with us. Beginning tomorrow, you're night marshal of the Gulch."

They were all still, all watching keenly. Dan Smith lifted his noncommittal eyes to Clare Durran, and saw something there in the taut, faithless countenance that he had not seen before—a weariness, a heavy care. But under inspection it vanished instantly. Benezet shifted his great body and slowly hauled the blue bandanna out of a coat pocket, rolling it between his damp palms. His mountainous shoulders tipped toward Dan Smith.

"Maybe you're not aware of the end of this old story," Dan Smith drawled. "The wild ones feed well on the fat of the town. They get ambitious for the little profit that escapes them, and they bear down harder. But they're deceived about men, Benezet. The time comes when the McNeishes think a little too long ... and then the wild ones die right where found. There's nothing in this world as wicked as the wrath of a peaceful man gone mad." He shrugged. "I wouldn't care to be night marshal."

The blue bandanna disappeared inside Benezet's tightening fist. "I could go back on your trail, Smith."

"Your first idea was that I might be an officer. That interested me. It set me to wondering. Now you've got me figured for an outlaw, running in front of trouble. Be sure, though, that you want to go back on my trail."

Benezet leaned forward, inscrutable but interested. Talk purred across his pendulous lower lip. "Gunmen are not usually bothered with a conscience. Nor are you the kind to scare easily. Is there something else to the story? It's for me or against me, friend Smith. Think about it."

The sounds of the barroom died unexplainably, but from the street a voice began to call, the message reaching those in the room only indistinctly.

Dan Smith opened the back door and then turned to present a smooth countenance to the men he had just addressed. "Loma Sam is dead, which is a leaf sailing in front of a stronger wind to come. I'll not be changing my mind."

Benezet, obviously, was listening to the disturbance outside. He said almost indifferently: "You may have reason to change it soon."

The others were so many fixed shapes in the saffron lamplight, but, as Dan Smith stepped into the night, he looked again at Clare Durran, and caught again that look of uncertainty and fatigue. He closed the door, stood loose muscled in the blackness, listening to the suddenly full-bodied sounds curving around the building to envelop him. Then he swung back on his original trail and passed through the alley.

Before he reached the street a clear and curt voice said: "McNeish, you're pretty proud."

He came at once to the street, and rose to the hotel porch. Pausing, he turned, so as to command that part of the street running toward the higher hills. It was strange, but in that brief period Dug Gulch's people had faded into doorway and recess and darkness. The silence held. Six men were posted along in the dust of the street, deliberately spaced from walk to walk. In front of them stood Bob McNeish, his mature, half-gaunt frame transfixed by the light beams from saloon and courthouse. He knew, Dan Smith thought grimly. He knew, but there wasn't any fear on his hard, honest cheeks.

"You're pretty proud," the voice repeated, and ceased there.

One man in the center of the line stirred on his heels, and McNeish at once reached for his own gun.

But he was too late. A solitary blast rushed like a heavy gust of wind along the buildings, and McNeish slowly bowed his head.

Dan Smith whirled on his heel, his mind black with fury. Sightlessly, he struck and knocked aside somebody standing in the hotel's door and went up the stairs.

He thought: This is what I'm running away from ... but there's never any use of running.

All patience was out of him, and he was as he had been that bitter afternoon in Fort Rock—a-simmer with a daring, destructive wrath that overwhelmed reason. It had come to this: a man never escaped the judgment of the gods. Whatever he was, he had to be; even if the trail was a thousand miles long, that judgment would overtake him.

My only usefulness, he thought, is to destroy.

He paused abruptly, seeing a thin sheet of light shining beneath his door. Then he reached out and wrenched the door open and came forward.

April Surratt stood in the center of his room, waiting.

AT sight of him she straightened, shocked by the strangeness of that hard face, by the sleety chill of those cobalt eyes. At her door, a few hours before, he had been a calm, gentle-speaking man. Nothing of that man now remained; he stood before her stormy and reckless and keyed to swiftness. Ease and youth were gone, and gone, too, was the shadow of weariness that she had so clearly seen.

"What is it?" she asked.

But he shook his head, and his muscles relaxed. The fighting flash vanished from the bronzed cheeks. "I wasn't sure who was in this room."

She said: "You see? The town is on your nerves. You have only been here since four o'clock, but you feel it. It has caught you."

He said nothing.

She went on, more rapidly: "You are too young to have that look in your eyes. Do you know what you are now? A man ready to kill."

"Why are you here?"

A little color reached her face, brought there by the directness of the question. But she held his glance. "You were very kind to me. I only wish to repay you. Dan Smith, Dug Gulch is nothing but a whispering gallery! You have been here four hours ... and every soul in the camp is wondering about you. Everything in your saddlebags is common knowledge. Every turn of your head and every word you speak is witnessed, and probably it will be known in the saloon, before ten o'clock, that I was here in your room."

"An old story," he murmured.

"Is it?" she queried. "You are too young to have such gray, dismal knowledge. Is it an old story that Benezet means to enlist you on his side? That is what I wanted to tell you." Then, prompted to a more woman-like quality, she added: "Just who are you, Dan Smith?"

"Another rider at the end of a trail that leads nowhere."

"An outlaw, as they say? No. You're not an outlaw. It isn't in you."

"I'm on the run," he said.

She shook her head. "But not from any crime."

"April Surratt," he said gently, admiringly, "there's nothing like courage. It covers all the sins."

He looked down at her from his flat and tough-fibered height until she stirred and moved to the door. She opened it a little, scanning the hall. Then she looked around at him, inward agitation turning her cheeks faintly pale.

"I wanted to tell you this ... if Benezet claims you, you are lost!" And with that, she was gone.

Dan Smith made one moody circle of the room, thinking: She's sunk in trouble, and she won't ask for help. It's this Clare Durran ... and a thousand of his sort ain't worth one of her kind.

Afterward he trimmed the lamp and walked down to a lonely supper.

When he returned to his room, he went directly to bed, to stare sleeplessly at the dark ceiling. A strange quiet had come to Dug Gulch's brawling street; the few voices he heard below were suppressed and curt. It was not difficult to guess why. Loma Sam was dead, and Bob McNeish was dead, and the smell of blood lay on the windless air. The night was tainted, oppressed. The old story was working itself into another familiar stage—that of fury, slowly growing and slowly hardening. The wild ones never know the limits of men, he told himself. This was what he had run from, yet here he was.

After ten o'clock the next morning, Dan Smith led his haltered horse across to the blacksmith shop and said: "Have a look at the off rear shoe."

The blacksmith glanced indifferently at Dan Smith, then at his helper lounging in the doorway.

"Lee," he told the helper, "go over to Spall's and get me ten feet of strap iron."

The far echoes of men at work in the outward ravines reached back to make small echoes on the silent, sun-drenched street, and the departing helper's dragging feet lifted whorls of dust. The blacksmith stared at Dan Smith again, now sharp and knowing, and he backed his squat body against the claybank pony and pulled the claybank's leg between his knees. A burly phrase rose from his bare, furry chest: "I lived too long in the Fort Rock country not to spot a certain well-known man when I see him."

Dan Smith studied the burning brightness of the day, and slid his words over a flat shoulder. "What does this girl want of Clare Durran?"

"It's common talk," said the blacksmith. "That girl's all right. Durran's a lawyer from Morgan Mountain, come here to make his pile from a claim. Him and the girl were engaged back there, so he sent for her. The claim was no good, and Benezet saw some use for him as a lawyer. So that's the end of another good man. Ain't it? You ought to know Benezet. But the girl saw what Durran was into, and wouldn't marry him unless he got out. There we are! But how in hell is Durran ever going to get out? There's some who wonder if he's all crooked, or just in bad luck."

The helper straggled back. "Spall's got no strap iron," he said.

"Then try Cope's," the blacksmith said. And when the helper was gone again, he added: "You see? It's pretty rotten. This camp's tough, but Benezet's tougher. He's got his bunch well scattered along the creeks, and they ain't all known to the miners. So Benezet's ears catch everything on the first bounce. There's a lot of dead men back in the brush. I say so. Try to get a straight deal! Benezet's rich from his saloon, and his hotel, and his women, and his claim jumping. Hell! What one good man with a gun could do!" The blacksmith straightened and bent his arm until the tremendous biceps whitened the sooty skin. "Just one man with courage. I'm glad you're here."

"No," said Dan Smith. "I'm not in on this."

"No?" said the blacksmith, and laid his chasm-black eyes on the other man. He chuckled then. "Listen, I know who you are."

A shadow drifted across the arch, slowly.

The blacksmith let the claybank's leg drop and said: "These shoes will do for another two weeks."

Dan Smith nodded, his glance following the citizen so casually going by. He took the claybank's halter and recrossed to the livery stable. Then he slowly sauntered through the thick heat toward the green promise of the pines.

A broad trail left Dug Gulch, tracing upward into the higher folds of the forest, with smaller paths drifting away at regular intervals. One of these he took, one that led downward into a shovel-scarred ravine, the gravelly entrails of which lay scattered as far as his vision ran.

Brush rustled above him faintly, then ceased to rustle. He was grimly contemptuous. He knew he was being shadowed, but it didn't matter. All this fell into a pattern so old that he knew every black and scarlet thread from memory.

Another thing absorbed his full attention, and he spoke half aloud. "I'll have to see Durran, but I'll have to arrange it."

He turned then from the gulch, and rose by another trail, through thick trees, stopping suddenly in a covert glade occupied by half a dozen silent men staring fixedly at him. One of those was the cripple, supporting himself beside a pine.

"I'm sorry, gentlemen."

One man with a beard so full as to conceal all his features, save for two sultry eyes separated by a strong, high-bridged nose, spoke in a voice reverberating suspicion. "Your name is Smith. There's only two sides to this camp. Come in ... or get out."

"You'll see," said the cripple. "He's another gunslinger. It's all over him. Another killer for Benezet."

"Let it ride," Dan Smith said, and cut around them. Their murmuring reached him through the intervening brush, and one voice, hot and headlong, overtook him even as he fell into the broad trail and came back to the street.

It was noon then, with small parties debouching from the hills and half a crowd observing drink time at the saloon. A stage labored up from the lower levels, raising a high dust. Marshal Sullivan appeared from the courthouse and stood by a pillar, watching that stage. Clare Durran also emerged from the courthouse and walked at his swift stride toward the hotel. Not wanting any dinner, Dan Smith went to the hotel room. Leaving the door open, he stretched out on the bed.

There'll be a little more of this, he thought. A little more thinking and a little more quiet. Then this street will turn red, and here I'll be. Doing what? It's what I ran away from, wasn't it? I have got to see Clare Durran.

Flat on his back, he built himself a cigarette, somberly observing as his tensile fingers curled and crimped the brown paper. It was odd: the good Lord gave a man long fingers and cold nerves to steady them against a gun, and then the world hounded that man into using his dark gift till the killer's trade was so plain across him that even a half-witted cripple could recognize it.

People came up the stairs slowly. The murmur of April Surratt's voice began to run along the hall, troubled and pleading. Dan Smith lighted his cigarette and held the match until the pale flame sank into his fingertips and died. Presently April Surratt's door opened, and April Surratt cried wearily: "Where is the end of this?"

"Later, later," cautioned Clare Durran's voice.

The door closed. Clare Durran's steps started away, but halted, and the flimsy hall flooring squealed. Dan Smith studied the ceiling above him, slack and motionless. Clare Durran was behind him, in the doorway, watching him without being watched.

Dan Smith blew the thin smoke from his mouth. "I wanted to see you," he said. "Come in. Close the door."

Durran obeyed. He walked the length of the room into Dan Smith's vision, and turned. Fatigue was written clearly on his mobile features. Seeing him thus off guard, Dan Smith's half-formed judgment became a certainty. Here was an educated man, a man of quick imagination, but there was no toughness in him, no vitality, no resistance. Behind the set and unbelieving mask of amusement nothing solid lived.

"You're pretty keen, Smith," Durran said. "Benezet fears you. Why should I make any bones about it ... for, if Benezet fears you enough, he'll have you killed. You were right. Behind Benezet are thirty men who will break any law God made, if that man says so. It seems small, compared to the camp? Think about it. Those men can collect, shoulder to shoulder, in five minutes' time. And they can shoot."

"Durran," said Dan Smith, "how did you get into this?"

Clare Durran drew a long breath. "How does a man get into anything?"

"I know," Dan Smith drawled. "Do you want to get out?"

"Be careful there!"

Dan Smith rose in one long, rippling motion. The cigarette smoke curled up across the smoothness of his bronzed cheeks. He looked ruffled and ruggedly aroused.

"You're clever, Durran. Your mind has got a razor's cut. But it's too nimble, and it has done things to you. It's furnished you with excuses for the jackpot you're in. But the excuses are lies, and you know they're lies. Your nerves are shot."

"Careful," Durran droned.

"You fool," Dan Smith said, coldly angry. "How long has that girl got to sit in her room and wait?"

Something in Clare Durran snapped. It didn't show on his face, so long trained to conceal, but the faithless eyes went darker and more barren. He said: "How could I get out? It's impossible! I will never get out ... and neither will you!"

That was all. He drew a rough breath, and the emotion of the moment, too strong for his indifferent frame, poured blood into his sharp features. Quickly, he passed out of the room.

Dan Smith thought: That show of nerve on the courthouse steps wasn't real. It was just contempt, backed up by Benezet's power. The man's empty.

Dan rested there, the arctic blue of his glance cutting through the tobacco haze, all his muscles idle. The courthouse fire bell struck two, three, four. The high heat of the day crowded into the room, insufferable within the four walls.

A considerable party of riders clopped along through the dust outside. Doors opened and closed along the hall. Then it was five, and the brilliance of the light began to dim. The miners, returning from work, disturbed the sluggish quiet.

Dan Smith rose and put on his coat. He lifted the blackened Forty-Four from the bureau top, balancing it in his palm and laying it back.

Some men, he reflected, are born for peace, and some are born for trouble. What is the use of running away from what's written in the book? If I try to support Durran, all the miners of the gulch will he on my trail. If I throw in with the miners, Durran is dead.

His alert ears identified heavy bodies climbing the hotel stairs. In the hall, a man's breathing echoed sibilantly. Dan Smith stared at the idle Forty-Four again, and turned his back to it. He stood thus when Benezet halted at his doorway.

Behind Benezet, ridden by violent suspicions, stood Marshal Sullivan. Benezet's face was streaming. He blotted it with the wadded bandanna in his fist, and his small eyes, unchanged and changeless, met those of Dan Smith.

"I didn't have to go back on your trail, friend Smith," he said. "A man from Fort Rock rode in today. So I was mistaken."

"Nothing," Dan Smith said gentry, "stands still."

"You are not a peace officer," Benezet pondered, "and not an outlaw. You're a man extremely well known for handling a gun. In Fort Rock the other day, you met and killed three riders who had come to find out if you were as good as your reputation. Your real name, friend Smith, is Dane Starr."

The man who had been Dan Smith, and who now, by Benezet's softly issued words, became Dane Starr, stared somberly at the fat, bland face.

Benezet spoke curiously: "Tell me, why did you run? Canrinus was a rustler and Dane Starr could ride high and easy anywhere he wanted. Why did you run?"

Dane Starr said: "The reputation, Benezet. Once a common thief made me draw. It became known then that I was first. I have had no peace since. There is no peace for a man with that reputation. Trouble camps with him, and all the tough ones come to try their luck ... as Canrinus did, as others did before him, as others will do again. Nothing but trouble, Benezet. Good men wanting me to settle their griefs for them, and bad ones wishing to take my measure. Certainly, I'm Dane Starr, a name recognized as far as it is heard. What for? For the ability to kill. But I want no more of it. I've closed the door on my past, Benezet. My name is Dan Smith ... and I don't carry a gun."

"You're through, then," said Benezet. "I won't have you in my camp. You're a hero to the country, and you will be a hero to all those fools picking dust out of the gulches. Not in my camp, Starr!"

"So I ride?"

Benezet said: "The damage is done." He turned about and waddled down the hall, Marshal Sullivan guarding his rear.

Dane Starr remained quiet, feeling none of the room's sulky heat, hearing none of the guttural talk in the street below.

Abruptly it was sundown. The hard light died from the window, and faint purple began to streak the sky. The room turned to shadow.

"So trouble comes again," he said aloud, and stood straight and stolid in his tracks.

A flickering restlessness broke the Indian calm. He turned suddenly and lifted the gun, opening and whirling the cylinder until the blue metal blurred. Then he closed it and placed the weapon inside his waistband.

"The waiting and thinking are over," he said, and paced along the hall, slowly down it.

Somebody came running up the flight of stairs at the rear, and turned at the landing to face him. He stopped, seeing that April Surratt's eyes were bright with fear.

"Dane Starr!" she said. "You are too young to have that reputation! Even in Morgan Mountain men spoke of you. Don't go out on that street!"

"What other way would I go?" he asked gently.

Her shoulders ceased to be straight. She was still. She was watching him. Through the lengthening silence feet tramped and scuffed, and voices sank lower and lower. A man came to the foot of the stairs, lighted the wall lamps, and looked up, curious.

April Surratt whispered: "I know. No other way. It ... it's so cruel! But it's fine to know one man who's unafraid."

She placed a hand on his chest for a moment, trying to smile as she did so. Then she went on up the stairs.

Dane Starr descended to the lobby, brushing past the man who still paused there. Other citizens hurried in from the porch and filled the lobby, shaken with excitement. When they saw him there, a whetted eagerness came to their faces, and they stepped aside to let him pass out.

He turned and dropped down to the walk—and there stopped. On his left was the alley into which Marshal Sullivan, earlier, had ordered him. On his right were the walls of the building opposite, and eyes were watching out of suddenly lightless windows. In front of him, thirty paces onward, was what he had expected—ten or more masked men loosely strung across the dust, all silent, all turned toward him.

One voice said: "Hello, Starr."

Over by the stable's arch, the cripple leaned against the wall, brutally and eagerly looking on. Dane Starr's thoughts remained on that broken-bodied figure, so crowded with hatred, and the precious moments fled by. The dusk deepened, and sounds withdrew from the street. The very air seemed to have been sucked away.

The even voice said again: "You're a pretty proud man, Starr."

DANE STARR said: "I'm a little more ready than McNeish was. Go ahead." He stood on the balls of his feet, watching that shadowed line for the sudden break, feeling the polar cold go through him. It was always like this at the showdown: the fine warmth of a man's muscles disappeared, and solidness and decent reason. He became something without body, without nerves. Time stood still.

His words fell flatly in the crouched, utter stillness, and the scene before him was indelibly clear to its least detail. Thus aloof and indrawn, one faint thread of contempt ran through his brain. His name evidently meant something, for they delayed that moment. They let the precious instant of surprise go by, and he saw then which man in that hooded line would draw first. He had been warned by an imperceptible bending and stiffening of frame. Somewhere a door slammed, its echo tremendously startling.

Somebody in the hooded line—not the crouched man—said: "How fast are you? Let's see."

It was an ancient trick, intended to draw his attention away. The crouched man erupted at the same moment. His arm dropped, rose. But to Dane Starr, ceaselessly watching, it was like the beating of a brass gong. His cocked nerves let go, and the deep and bitter explosion of the gun was his own.

The hooded man never straightened..He tipped silently forward into the dust, and his hat came off and went rolling away.

One fierce yell of approval came from the hotel. Dane Starr took a broad step aside into the alley, and thus shielded by the corner of the abutting building, he fired on the end of the line that was posted across the street. He saw a second man flinch, seize a porch post, and weakly settle.

Two things then followed in rapid succession. The line opened up on him, slugs ripping away the corner of the wall behind which he stood. And then, unexpectedly, a shotgun stirred this bedlam with a deeper ferocity. There were two vast explosions, and the rattling hail of small shot. The effect was instantaneous. The focused firing on Dane Starr ceased, and the hooded line swept across the street. Benezet's men had suddenly melted into the yonder doorways.

Alert and aroused, Dan Starr heard the blacksmith's pleased shout of triumph. Then a voice—Benezet's smooth, indifferent voice launched from unknown shadows—entered the pulsing calm.

"No more firing. Pull up, Starr, pull up."

Dane Starr thought, suspiciously: Why don't they go through with it?

Abruptly the cripple yelled his brutal disappointment, and plunged across the street at a staggering run, bound straight for Dane Starr's shelter. He cried: "Get him ... get him!" His head lay back on his crooked shoulders, and his savage face showed a remorseless bitterness in the intermittent lights.

But he broke the deadlock. Men poured from the hotel lobby, and one of them reached the cripple and struck him angrily down into the dust. There was a half crowd at the alley's mouth, a hard- breathing mass that shielded Dane Starr from guns farther off.

"Get in the lobby," said a wind-clotted voice. "Get in there. Nothing Benezet says is right."

Dane Starr moved from alley to porch, the miners close ranked behind. He walked into the lobby and halted, while all Dug Gulch slowly filed in out of the night and recruited behind him. Deeply puzzled, he stood in the center of a sullen, electric humming. Benezet was no fool, no faint-hearted man. Some shrewd and greedy impulse was behind his holding of the fire, some new thought born out of the volleyed crashing. What new move was the man proposing?

Dane Starr's restless mind cut forward and backward, and got no answer. The blacksmith shoved his way through the assembled miners to Starr, his smoke-black eyes wickedly cheerful. He had a twelve-gauge shotgun in one hand, two empty cartridges in the other palm.

"I had 'em flanked," he said, and laughed at the thought. "Nothing on earth can stand against buckshot at twenty feet. Makes no difference about pride. They give, and they run."

"You're a dead man," a miner said thoughtfully. "You'll be dead by tomorrow night, Guerney."

The blacksmith's smile was close, brilliant. "By tomorrow night, Billy," he said softly, "it won't be me that's dead." He looked up at Dane Starr's bronzed mask of a face, and the light of his eyes flashed more recklessly. "Benezet's had his thumb on us a good while. Why? Because his whip had a handle, and he's the handle. It takes one good man to stand up and say ... 'Let's go, boys!' We never had that man. Listen! I'm from Fort Rock. I know this Dane Starr. I never saw him take a backward step. Here's the handle to our whip. I'll be damned if he isn't!"

The crowd grew. The word was out. The invisible telegraph was alive. They came in until the lobby was full, and tobacco smoke began to layer the room and the reek of fresh dirt and sweat to permeate it. Dane Starr remained silent, witnessing the heady anger working in all those rough faces—the sultry flash of a long-compressed rage. It was like opening the doors of a furnace; the angry heat rushed at him that suddenly.

Guerney, the blacksmith, laughed again and said: "What is it to be, Dane?"

"There never was a better time than now," a nearby miner interrupted, and shook a raw, roan head turbulently. "Never better than now!"

Starr spoke quietly. "We could whip them now." Silence arrived instantly. He had his audience.

The blacksmith grinned and addressed himself. "One good man. What did I say yesterday?"

"We could whip them now," Dane Starr repeated. "But why run into that waiting fire? Who wants twenty dead men scattered on the street? A high price to pay for the cleaning of a town that will be only another ghost camp, two years from now. Benezet stopped this fight. Why did he stop it? Think a minute. The man's no fool. Walk out there ... and walk into the lead he's arranged to have spilled."

"Straight palaver!" said the blacksmith, and openly admired Starr with his eyes.

There was talk in the back ranks. "Benezet and Sullivan and this so-called Judge Haley ... and Clare Durran. They're the ones we want."

"Yes," Dane Starr said noncommittally.

"All right. Let's go get 'em."

"Right into the guns," Dane Starr warned gently. "Wait a little."

"This man," the blacksmith exploded, "has got something up his sleeve. Stand fast and listen."

The cripple knocked a way through the solid mass. He seized a miner's arm, thus supporting himself, and his free hand shook violently in the direction of Starr.

"You're not straight!" he cried. "Listen, boys, don't be fooled ... he ain't straight! Where'd he come from, and what for? It looked like a nice play, out there on the street. But Benezet's men didn't hit him, did they? Benezet stopped it. Why didn't any of those slugs reach him? Why did Benezet stop it? Here he stands, tellin' us to do nothing. I know why! That girl...."

The blacksmith whirled in fury and grasped the cripple by the shoulders and shook him. He turned the cripple, smashed him back through the crowd, and dropped him by the doorway. "You're as batty as hell! Get out of here!"

Dane Starr's eyes followed those two swirling figures, and his bronzed jaws tightened and killed all expression. He said to those staring men: "Wait."

"How long?" somebody called.

"Why say something that will get right back to Benezet? He's got ears in this crowd. Tomorrow's a long day. Do you get it? Never play the other man's game."

"Don't trust him!" the cripple shrieked, and ran out.

That pondering silence had a depth to it, like calm water beneath which a wicked current waits to drag a man down.

Dane Starr shook his head and walked to the stairs. Three steps upward he turned.

"That's right. Don't trust anybody. I'm with you. I'm in on this. Never mind what happens, I'll be here till the last powder's burned. But don't trust me any further than you want. Why should you?"

He went on, the strain dying from his face muscles, once he had reached the darkness of the upper hall. A glowing streak crept beneath April Surratt's room, but he went on to his own, drew down the window shade in the darkness, and lighted a lamp. His first act was to reload his gun and to replace it under his waistband. Afterward he sat on the bed and rolled a cigarette and stared barrenly at the barren walls.

The cripple had the right of it. Somewhere in that half-mad head rested an uncanny perception that was like a drunken man's sharp glimpse of truth. He, Dane Starr, was with the miners. He had announced himself, and so had assumed an obligation that beyond denial would have to go the whole route until Benezet was down, and the stiff-jawed Sullivan, and the judge. Clare Durran, too. Nothing further mattered, for the lesser thieves would fade like all thieves bereft of support.

He drew in a great breath of smoke, crushed the cigarette between his fingers, and rose suddenly. Well, its as old as time, he thought. He who lives by the gun dies the same way. But there's Clare Durran!

The cripple had the right of it, Starr thought again. April Surratt wanted Durran out of this mess alive, and April Surratt would get her wish. So he stood between two fires, having no illusions as to what the miners would do to him for protecting Durran, whose faithless smile and long-shown contempt had been so galling. Durran had dug his own grave.

Dane Starr's eyes widened on a segment of the pattern of the carpet. He was motionless until the thought came to him: That's why Benezet stopped the shooting. He knows the girl has seen me. He knows I'll help Durran because she wants it so. That finishes me with the miners. I'm as dead as if he himself had put the bullet in me.

He raised his head, eyes smoky and turbulent. "Not many men in the world with a mind that quick," he said.

He looked into the mirror, and looked away. I ran away from this—and here we are again. It's a game where you can't change seats, or deck, or deal. So why complain? We play the hand out. Which isn't much of a brag, since there ain't any other hand.

The street was very quiet. Reverberations of the crowd in the lobby came up through the flimsy boards of the hotel. Dane Starr grinned faintly and shut his mind. Then a rough and daring flame rushed diamond bright through his cobalt eyes. He dimmed the lamp. He stared over to the window shade and changed his mind, screwing up the wick again.

Opening his door, he passed into the hall and strode across to April Surratt's door in three cat-footed steps. He had meant to knock, but didn't, for a murmuring came through the panels—the girl's low murmuring instantly followed by a phrase from Clare Durran that was ragged and dissonant.

Dane Starr thought—There's nothing in him.—and pushed the door open.

The room was faintly illuminated by a lamp turned low. The rear window was open. Clare Durran stood in a sheltered corner, away from the light and away from the window. His face came around to Starr, thin and dark and shadowed by a moment's desperation.

April Surratt, bearing her trouble on proud and straight shoulders, was a poised shape in the center of the room. She said in a low, composed voice: "Please shut the door."

The rigidness, the shock, went out of Durran. The insolence returned. "Has knocking gone from style?"

"Your tongue can cut and hurt," said April Surratt. "Don't use it on him, Clare."

"Why not?" Durran challenged. He added bitterly: "Am I under obligation to him?"

She was watching Dane Starr, catching each bold line and each flat surface of that unchanging face. She merely murmured, "I think your fate is entirely in his hands."

"Have I asked for any help?" Durran demanded angrily. "Have you asked help for me, April? If I thought so...."

"She didn't," said Dane Starr. He walked over to the window and looked into the utter blackness of Dug Gulch's unlovely rear. There was a ladder rising to the window. "She didn't need to ask. What has she been staying here for?"

"I don't need any help!"

But Dane Starr pointed at the window. "Think again. Why didn't you use the lobby instead of that ladder?"

"Answer it yourself," Durran said impudently.

"It was all right while it lasted," Starr said. "Benezet kept you going. Benezet's power supported you. Benezet's hand cast a big shadow, and you walked safely in it. You could smile at men in a way to make them want to kill you, and you knew they didn't dare. Well, it's about over. You realize that, or you wouldn't have used the ladder. You're afraid, Durran."

"There is going to be bloodshed here," Durran said angrily. "It will be on your shoulders. Why didn't you stay away?"

"Speaking for the established order?" Starr asked gently.

"Why not?" Durran challenged. "If it wasn't Benezet, it would be some other thief. Did you ever hear of a mining camp on the level? No. And you never will. Let human nature alone, Starr. Benezet's a crook. Certainly. But he was good enough to pull me off a worthless claim and give me a chance to earn a living at my own trade."

Dane Starr framed the questioning word—"Honestly?"—in his throat, and killed it. For April Surratt's eyes were on Durran, heavily shadowed, the fine light gone. All her body was still, intent. She was absorbing every word.

Dane Starr thought: Why does she want him? Then he spoke to Durran. "Do you want to get away?"

"I'll get away."

"Not fifty feet without help. The stable is guarded by now. How far do you suppose you and this girl could travel on foot? It's starvation in the hills. Your way is toward Morgan Mountain ... and they'd sight you on the prairie and ride you down. Horse or nothing."

"Where do you come in?" asked Clare Durran. Physically, he was quiet, but his thin cheeks went suddenly hard and homely. His eyes passed swiftly from April Surratt to the high built rider, and back to April Surratt again.

"Do you want him away?" Dane Starr asked the girl.

She said—"Yes."—soberly, and met his level glance. Her next phrase was in a lower tone, and it seemed to shut Clare Durran out. "I like to finish what I begin."

Clare Durran laughed curtly, maliciously. "Your scruples seem pretty mixed, Starr. You want to reform the camp. But you're helping me ... and double-crossing the men you're leading."

"If that's the way the hand reads," Starr said, "that's the way it's played. We do what we've got to do. Tomorrow, after dark, there'll be some horses in the brush ... two hundred yards straight south of this hotel. Both of you get there when dusk comes, and ride on. You'll hear firing before you travel very far, but it won't be for you. It'll be for those left behind."

"Three horses?" the girl said.

Dane Starr's cheeks were expressionless. "Two will carry you."

"It will soon be known that you helped us. The camp's a whispering gallery. And you will be here without a friend. Three horses, Dane."

He said, after a while: "I'll be a little delayed."

"We'll wait, then," the girl said, and, when he looked directly at her, he saw the queer highlight shining along the straight brow. It was very plain, and very strange.

Beyond his vision, and beyond April Surratt's, Clare Durran spoke with a crackling dryness. "I suppose I should thank you, Starr. Maybe I will, when we're on the trail tomorrow night."

Starr was speaking to the girl. "It was Durran you came to get, wasn't it?"

"We will wait," she repeated.

"Three horses, then," Starr said gravely.

Durran motioned toward the lamp, and Starr reached the light and lowered it to a mere purple glow. Durran went through the window without a sound, and vanished.

Long moments afterward, when Starr had freshened the light again, April Surratt stood with her small, square shoulders in the same motionless attitude, her eyes waiting for him. But he turned abruptly to the door and went through it, saying over his shoulder: "When you reach Morgan Mountain, be sure that you've brought back with you the man you thought you'd find. Be sure of it. And don't go out into the street tomorrow."

Behind him was a sharp, swift sigh and a quiet phrase: "I know already what I've found, Dane."

CLARE DURRAN dropped to the bottom of the ladder and paused there, watching the light flare up again in April Surratt's room. His small hands seized a rung of the ladder. The breath went in and out of him quickly. He whispered, half in rage: "That was plain enough!"

Somewhere in the dark a foot struck sharply against a wooden box, making a brittle noise. A man spoke under his breath. "Tug, go back to the street and watch."

Durran's hand pressed down on the gun in his own pocket. He moved lightly along the opaque shadows, brushing first this rear wall and then that, until he arrived at the rear of the saloon. After a short pause, he let himself in with a rapid whirl of his shoulders, and slammed the door shut.

Benezet sat musing at the table and silently twirling an empty glass, his two ever-present bodyguards speechless behind him, the stiff-jawed Sullivan across from him. Sullivan looked at Durran, and let his eyes fade back across Benezet's face.

Benezet said: "Somebody posted out there?"

"Getting dangerous," Durran answered, absorbed in his own irritated thinking.

"Where were you?"

"At the hotel."

Benezet's small eyes, faintly amused, twitched to Sullivan. Then he said to Durran: "Stay out of there now, Clare. The lower half of the town belongs to the miners. We stick to the saloon."

"How long?"

"Till they get a notion to rush us."

"Is this the best we can do?" Durran said. "Hide behind a wall and admit we're licked? That's not like you, Benezet."

Benezet chuckled. "You don't know what I'm like. I take one thing at a time. Right now it's this. Maybe before curfew...."

Durran reached for Sullivan's empty glass and poured a drink from the bottle standing there. He downed it, moved around the table, aimless and brooding. He was in a far corner, his back to them, when he spoke again. "No, not tonight," he said.

"All right?" said Benezet, a question in the words.

Durran turned toward him. "Starr's holding this fight off till dark tomorrow."

"Yeah?"

"Because he'll be out of here then with the girl. Lay a couple men in the brush two hundred yards straight east of the hotel, at that time, and you'll find three horses waiting for them. That's straight."

"Three horses?" Benezet repeated.

Sullivan stared curiously at Durran.

"Extra one for relief, I suppose," Durran said, without emotion.

"So she dropped you?" said Benezet, deliberately overlooking the more important fact.

"She's been engaged to me for a year, and she met him just twenty-four hours ago," Durran said. "Is it because he's built like a tiger, or because there's something mysterious behind those damned black eyes? What makes a woman change in twenty-four hours, Benezet?"

Benezet rolled his palms on the table. Ironic laughter glimmered beneath the heavy brows.

"I don't know women," he said. "Not that girl's kind. But I know you."

"All right," Durran said, and jerked up his head.

"You're a dapper man, Clare. You got a manner, a damn' bright brain, and a ready tongue. In a settled community you'd shine. You'd be a big man. Up here, in this tough camp, you are only a small man with a day's whiskers on your face. See? it's law and order that makes you swagger. You got no nerve for rough and tumble. This Starr is a man anywhere. Maybe the girl sees it."

"Glad to have your true opinion," Durran said violently.

"I been pretty good to you, kid. May be an end to that ... we'll never know."

"That bad?"

"Maybe. Maybe not." Benezet's frame was mountainously formidable in the hazy light of the room. "I'm a great hand to wait till the last fellow's fired before looking at my luck. Better get a drink," he added.

It was dismissal. Durran showed his irritation. His cheeks were drawn and dark as he went out into the barroom.

Sullivan said to Benezet softly: "Three horses?"

"The girl asked Starr to help Durran, and Starr's that kind of a man. So the three of them have fixed it up for tomorrow night. But Clare saw something there between that girl and Starr. He's selling Starr out."

"Leaves it kind of tangled," Sullivan said.

"No. Clare'll be rustling around for two horses to cache at some other spot. He'll lie to the girl, and take her away. Starr's waiting with the other horses ... and that's where we find him."

"Kind of stinks," said Sullivan.

"I always saw Clare plain and clear. This don't surprise me."

"If he's that tricky...."

Benezet looked at his marshal. One swollen fist rose, and a stub finger pointed mutely from Sullivan to the saloon where Durran was. His palm made a gentle, erasing gesture against the air.

When Durran went out to the bar, he took a drink. Then he turned and hooked his elbows on the bar and stared vaguely around the great room now occupied only by Benezet's followers. His brooding eyes passed over them one by one, touched a particular man, and moved on. In another moment he shrugged his impatient shoulders, swerved out to the street. A mere trickle of citizens stirred along it, and these walked through the far shadows.

Under the porch roof of the saloon four idle Benezet hands remained very still, very watchful. Durran passed them. One said: "Mister Durran ... not too far."

Durran merely nodded. A little farther he heard steps coming after him, and then he swung into an alleyway.

A figure cut the corner and halted.

"Tom? I got you out of some trouble once."

"Just mention it, Mister Durran. Anything you say."

"Two horses saddled to go."

"Not so easy, Mister Durran. But I will."

"Tomorrow, right after dark. Just off the trail that leads north to Placer, where the creek comes down." He ceased talking, and the silence was dull and heavy. Immediately he added: "Two hundred dollars to you when I step into the stirrup."

"That'll help, Mister Durran."

"More substantial than the deep gratitude you feel," said Durran with an irony so deft that the stolid figure in front of him missed it, and muttered: "Thanks!"

This was noon, and another day, and Dug Gulch's life blood seemed to have run out. At eleven the Morgan Mountain stage had stopped at the hotel, bearing two passengers, but the driver never got down. Two men came slowly from the hotel lobby and one of them said: "Water your horses, then turn back, taking your passengers with you."

There was no protest. The driver knew the country and its men.

The street was dead. One figure stood beside the saloon doors, and one figure leaned against the courthouse pillar. But between those two Benezet sentries there stretched an invisible line across which no man had passed since daylight.

The gutted ravines were still, deserted. A high sun poured fresh heat down from a cloudless sky, and on the lower prairie the returning Morgan Mountain stage kicked up a tawny ribbon of dust.

Dane Starr descended stairs to the lobby, and twenty-five men there showed a quickening interest. The blacksmith left a game of seven-up and came over.

He said genially: "There's this many across the street in the store. There's this many belly flat in the pines, all around the camp. If it's waiting, we can wait."

A raw roan head bowed beneath the hotel's door. It belonged to the miner who had spoken the night before. He strolled over.

"The street's safe enough to walk on," he said. "They're waiting. We're waiting. What are we waiting for?"

"You want four men," Starr said evenly. "How would you get them?"

"Go right where they are," said the redhead, his voice snapping.

The seven-up game stopped. A rustle of restlessness scudded around the room. The cripple swayed into the lobby and squatted near it. His burning, onyx eyes sought Dane Starr hungrily and stayed there.

Dane Starr's words hit the redhead like blows, one after another. "If you're in a hurry, walk down to the saloon and find them. The doors are open, and the street's wide enough."

The redhead's eyes glittered, and he pursed his lips and turned pale with anger. Yet he remained in charge of himself.

"Why dig your spurs into me? Whose show is this?" He stopped and scowled. "Now that I think of it, what's happened here? We were ready to go last night. Who's changed the tune here? What's the extra day of debating for?"

"Anybody can die," Dane Starr said.

"I'll take my chances."

"Take them," Starr challenged grimly. "There's the street."

The redhead's outraged pallor increased, and he threw his suddenly fired glance at Starr's stone-blank countenance. Pivoting, he walked back to the street. A tension snapped in the lobby. The seven-up game was resumed.

The blacksmith's admiring chuckle was resonantly hearty. He murmured: "You destroyed him, Dane. You could wrap this crowd around your finger."

"I want to see you for a moment in the shop," Starr said.

Side by side, they moved to the door.

A man in the seven-up game looked up alertly. "It may be a safe street ... but not for you, Starr. Benezet's sharp-shooter is in the courthouse tower."

Starr shook his head. "Benezet is a shrewd man, and he prefers to destroy me another way. It's an old game."

He went out to the porch. Half a dozen miners in the lobby turned instantly to the windows and watched him go idly through the drenching sunshine and swing into the blacksmith shop, Guerney beside him.

"Nerve!" somebody said.

The cripple said bitterly to the room: "He was pretty sure no Benezet man would fire at him. You fools! I know what the extra day's wait is for. Starr's helping the girl get Durran out of town. They'll be gone tonight. How do you know Starr won't be gone, too?"

One of the seven-up players said: "Get the hell out of here!" But in a moment his eyes sought the other players, and doubt was in them.

In the blacksmith shop, Starr stood slightly away from the arch and scanned the upper windows of the courthouse thoughtfully. High up in the bell-tower a mere porthole of glass showed a jagged break, and behind it lay something black and motionless. One of Benezet's hands marched from the courthouse door, touched the sentry on the shoulder, and took up his position. The relieved man went inside.

All this Dane Starr observed solemnly, other thoughts running through his mind.

Guerney moved restlessly back and forth.

Still watching the courthouse, Starr said: "Never mind what this sounds like. I need three horses."

He heard Guerney stop. The silence ran on. Two miners rolled past the arch, looked in, and wheeled back.

Guerney's speech was flat. "All right," he said.

Starr turned. "In the trees behind the hotel, tonight, as soon as dark comes. If the girl's come this far and waited this long for Durran, would you want to break her heart? Never mind what the crowd wants. Benezet's the only man we're after."

"Three horses?" said the blacksmith. He put his felt-black eyes on Starr and then turned his head away, a gray and unpleasantly disheartened expression seizing the broad face.

Dane Starr smiled at him. "She thinks so, Guerney. But I'll be here. I'll be right here."

The blacksmith's cheeks registered enormous relief. He grinned. "The horses will be there, Dane."

"Trust," Starr said, "is a wonderful thing."

Guerney spoke with some apology. "What's the extra day of waiting for? You could've got Durran and the girl off last night."

Starr hunted for his tobacco and sat on the end of an empty nail keg. "We could have taken the camp last night. It's a question of how much the taking is worth. A lot of those miners have families somewhere, Guerney. How would you like to be writing ten families this morning, telling each that a man was dead ... killed in a fight to clean a camp that will be a crumbled relic overgrown with hazel brush twenty months from now?" His sigh expressed sadness. "I have had to do that. It's pretty tough."

"Tonight won't be no easier."