RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

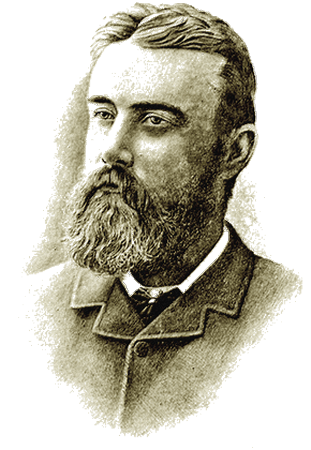

Ernest Favenc (1845-1908)

British-born and educated at Berlin and Oxford, Ernest Favenc (1845-1908; the name is of Huguenot origin) arrived in Australia aged 19, and while working on cattle and sheep stations in Queensland wrote occasional stories for the Queenslander. In 1877 the newspaper sponsored an expedition to discover a viable railway route from Adelaide to Darwin, which was led by Favenc. He later undertook further explorations, and then moved to Sydney.

He wrote some novels and poems and a great many short stories, reputedly 300 or so. Three volumes of his stories were published in his lifetime:

The Last of Six, Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1893

Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1894

My Only Murder and Other Tales, 1899

His short stories range from bush humor to horror, supernatural to strange, and to the privations of late 19th century exploration in Australia's unforgiving inland. His first two short story books (consolidated into one volume, as there is considerable overlap), are available free as an ebook from Project Gutenberg Australia.

—Terry Walker, January 2023

IN this, the seventh and probably last, compilation of prolific author Ernest Favenc's hitherto uncollected short stories, I have included a number of stories that were, in fact, previously collected in the now extremely rare book My Only Murder and Other Tales (George Robertson and Co., Melbourne, 1899).

I had hoped to track down all the stories in that volume to recreate it digitally, but some of them are, so far at least, unobtainable. Those that I have recovered are scattered through this series, with several in this volume.

There are still other stories not yet collected due to shortcomings in the OCR texts of newspapers at TROVE, the digital archive of the Australian National Library, and the sometimes poor condition of the original 120-140-year-old newspapers themselves. There are, almost certainly, a number of other stories as yet unknown to me. Sometimes story headings in these old newspapers were in graphics, rather than typeset; the OCR software at TROVE cannot read them, so they don't find their way into the index.

T. Walker, February 2023

I HAD not heard of or from my old friend Jim for more than a year when to my great surprise, I got a letter from him to say that he was married to the little girl he had met when he was coach-driving. Her husband had drunk himself into his grave, and Jim, following his fate, had espoused the widow. He wrote and asked me to visit him, if ever I was up in that district, and in course of time I did.

I found Jim much more comfortable than the generality of Australian small farmers. As a rule, they are a class whose principal virtue is a capacity for hard, continuous work, but in other respects they have not the faintest notions of decency with regard to everyday life. The better off they are the more they delight in living roughly and coarsely. A shilling spent on comforts is regarded as wicked waste by the generality of them.

Jim, however, had knocked about a good deal, and thought differently, and little Mrs. Parks agreed with him. He had a comfortable house, and he lived in it; didn't pig in the kitchen, as most of his neighbors did. Jim was unfeignedly glad to see me; said he hadn't enjoyed an edifying conversation for months, and implored me to stop a week, at least.

'I'm in trouble, old man,' he said, the second day of my visit.

'Why, you and the wife are as jolly as sandboys; you don't look it anyhow.'

'Ah, that's on the surface; I'm wasting away with worry.'

'Well, out with it, I know that it will do you good to tell it.'

'Yes, I want your advice. Fact is, I am haunted, and I don't know how to act; I, of all men in the world. Haunted by the ghost of that drunken galoot who first married my Tilly.'

'That's very awkward,' I remarked.

'It is so particularly when he is such a lowdown, sneaking kind of ghost. You know I told you, how I pitched him into a creek once? Well, he makes out that that was primarily the cause of his death, which it wasn't; he drank himself to death. However, he holds that I am his murderer, and that he has a right to haunt me, and intends doing so. Now it's worrying Tilly. She put up with enough from him during his life, without having to be tormented now he's dead. I'm going to stop it somehow.'

'How does he appear?' I asked.

'In all sorts of ways. Sometimes by knocking where you don't expect it; sometimes you'll feel something very cold and wet touch you—that's to remind me of the creek business; and sometimes he'll begin cursing and swearing like he used to when he was drunk.'

'Why don't you try your old game of ridiculing him, if he won't listen to reason. I suppose he's got a down on you for marrying his widow?'

'That's just it. Now while you're here I intend to proceed to extreme measures. You will give Tilly more confidence, for it's made her nervous. He hasn't shown up since you've been here. I suppose he's taking your measure before he plays up.'

Jim and I then constructed a plot which was to be carried out immediately the ghost put in an appearance.

We had not long to wait. That evening at tea there came a thundering rap in the middle of the table, that jarred everything standing on it. Mrs. Parks turned pale, and Jim looked at me significantly.

'I thought table-rapping had gone out,' I remarked. 'I understood that the respectable ghosts boycotted all the low brutes who went in for that sort of thing.'

'There are some ghosts too mean for anything,' returned Jim.

Here there were three or four angry raps on the table.

'Go it, old man,' said Jim, 'break the crockery, it's what you used to do when you were alive, and very drunk.'

'Don't irritate him, Jim,' said Mrs. Parks, as several sounding thumps came on the table.

'Is it a Chinaman's ghost?' I asked.

'Yes; it must be, for he's not game to show himself.'

'I am,' said a voice.

'No, don't on any account,' said Mrs. Parks.

'Jim,' I said, 'surely he will not have the bad taste to show himself when Mrs. Parks is present; let him fix a time with us to argue the question, end show him the error of his ways.'

'Yes, but he's such a sneaking brute, he won't.'

I gave a start and a jump at that moment, for something cold and wet touched my hand, but it was only the nose of Jim's dog who seemed interested in the conversation.

'Will you materialise, and meet me to-night? I think I can show you reason in the matter.'

'Very well, I'll see you at 12.'

Jim and I had agreed that he should not appear personally in the matter, for his temper was naturally ruffled at his wife's late husband insisting on making things so disagreeable.

Twelve o'clock found me awaiting the ghost armed with a bottle of whisky. He was a long shambling, unhealthy looking fellow, not at all up to the mark as a ghost, but perhaps his death and burial had not improved his appearance. I inquired if it would incommode him to take a seat. He replied 'no,' and sitting down, cast a greedy eye at the whisky.

'Perhaps in your materialised form you can partake of some refreshment?' I said.

'You bet,' he replied, and helped himself to about half a tumbler, which he tossed off without more than an apology for water.

'Now, what's your little game?' I asked.

'Simply to annoy Jim Parks. 'I'll make his life burden to him.'

'And you won't do yourself any good.'

'Won't I?' he said, reaching out for the whisky bottle again. 'I'll have the pleasure of tormenting him.'

'Well, you are a contemptible kind of ghost,' I said: 'I always thought ghosts were of a better disposition.'

'Disposition! I'll disposition Mr. Jim Parks; he'll chuck me into a waterhole, will he? And marry my wife? Here, what yer hugging that whisky bottle for? Pass it over here.'

It was evidently taking effect upon him, and in a short time he began to talk incoherently, addressing some invisible person in the room, who was seemingly striving to get him to come away. After a few more nips he became unconscious, and went to sleep, breathing stertorously.

Jim came in, and we both regarded the sottish ghost.

'He'll be precious bad when he wakes; let's brand him.' He took the cork of the whisky bottle, burnt it in the candle, and blackened the ghost's face with it.

'I reckon I'll get rid of him for the price of a case of whisky,' he said.

It was a shattered ghost that appeared the next Bight. 'Give me a drink,' he prayed.

'I don't see why I should,' I replied. 'Jim's scarcely likely to keep you in free drinks when you're doing all you can to make his life miserable. However, here's a glass of water for you.'

'Water!' he exclaimed, with scorn; I want whisky. I nearly overslept myself; only just woke up in time to dematerialise before daylight, and haven't been getting slops ever since. They say I have utterly disgraced the profession coming back with my face blackened. That was a shabby trick to play on a poor ghost—an orphan, in a strange land.'

'Good enough for you. 'What do you mean by coming here at all?'

'Don't talk; give me a nip. A recovery is bad enough when you are alive, but it's ten times worse when you are dead.'

'If I give you a good stiff nip will you consent to discuss this question, from both points of view.'

'O glory! yes.' I gave him a stiffener, and sighed deeply, and remained quiet until it worked a little. 'What do you want me to do?'

'Stop coming here.'

'I won't.' As he said it he gave a howl, and jumped in his chair.

'What did you do that for?' he cried.

'What's the matter,' I asked, 'somebody from your side of the world trying to teach you good manners?'

He grabbed the whisky bottle, and tossed off half a tumbler.

'There,' he said, defiantly, addressing the unseen person. 'I defy you. Just you hit me again.'

The next instant he received a blow in the face that knocked him back into his chair, where he sat gaping with his mouth open.

'I say, that's not fair,' he gasped. 'Well, come down to conditions,' I said, 'your friend evidently does not approve of your conduct.'

'What'll you do?' he muttered.

'You can have a right royal spree to last all the rest of the time you are in eternity if you promise to leave off this foolery.'

He spoke in some unknown tongue, and apparently got an answer, for he said, 'I've got to or else I'll be degraded to the seventeenth circle, whence I can't come back to earth.'

'Jolly good job,' I said, 'but how do I know that you will keep your word?'

'I will answer for him,' said a clear voice, full of authority and dignity. I had now got so accustomed to mixing with spirits that I did not even start at hearing this. I bowed towards the direction the voice came from, and expressed my sense of the honor done by his using the influence.

'He will have a week's leave, and I trust to your honor not to let him expose himself to strangers, nor play practical jokes on him when he is unconscious.

You hear,' he went on in a voice of great severity, 'mind you obey, or the seventeenth circle for 600 years.'

The voice ceased, and the wretched spectre remarked, 'He's gone,' and stretched out his hand to the bottle.

I told Jim of my success, and the next morning Mrs. Parks went off on a visit to a friend. What a time that ghost gave us; he used to stop all day, for he was so drunk that he could not dematerialise himself, and used to make frantic efforts, and fail. He'd vanish as far as his waist, and then his power would fail, and we'd look in to see the upper half of a man's body, holding on to his glass, and singing, or trying to sing uproarious songs. He got Jim an awful, bad name, for, as his presence was kept secret, people put down all the racket either to Jim or me.

Never was there such a drunken ghost since the beginning of time. He used to knock himself about fearfully, and was bruised all over. At last, delirium tremens got hold of him, and he used to talk about things that it was not nice to hear. He was so bad that his shaking hand could not hold the glass to his lips, and we were able to control his potations, so that by the end of the week he was shaky and comparatively sober. We were afraid that he would not be able to disappear, but the unseen presence came, and gave him a hand, I think, and he faded gradually upwards, his eyes disappearing last, and they were fixed on one nip left in the bottle. I think he regretted losing that nip more than anything. Jim harnessed up, and went over to fetch his wife back, and I left Jim in a few days, relieved and happy.

SOME time after that I saw an account of mysterious

proceedings in Sydney. A tall, shambling man had made himself

notorious by appearing in hotel bars, demanding a drink, and

immediately he had swallowed it, disappearing, naturally without

paying. His movements created the utmost alarm, but all efforts

to secure him failed. At last he must have made too many calls,

for he fell asleep in one place, and was secured by two trembling

policemen, who, however, managed to convey him to the lockup.

Needless to say, when they went for him he was gone.

He has not appeared since, so I suppose he has been banished to the seventeenth circle.

LARRIMOOR was an important township in New South Wales. That is to say, important in the eyes of the inhabitants, who considered they were justified in regarding it so. It was a very conservative township. Most of the residents in and around it were of long standing, and had risen with the town.

It also possessed an oldest inhabitant, but the people were only partially proud of him. He knew too much. If he had confined his recollections to floods and droughts, etc, it would have been right enough; but he mixed social matters up with other matters in a way that was quite unnecessary. When a man distinctly remembers the arrival of wealthy townspeople with the proverbial half-crown, or nothing, it is inconvenient.

Watkins, for that was his name, was a standing trap for the verdant young reporter. When anything happened out of the usual, and the verdant ones came up to give it world-wide publicity, they invariably struck Watkins, and they all of them thought that they had discovered Watkins, when, in fact he had figured over and over again, as the oldest inhabitant, whose memory was something marvellous.

Watkins was a stubborn democrat, to neither man, woman, nor child would he give the slightest title; he called the local C.M.G. 'Moe,' and so with everybody else. He was feared, was the oldest inhabitant, and he knew it. You might set them up again till further orders; but that would not prevent him from reminding you of the time when you were slushy to the shearers' cook at Mindambin.

Mindambin had been the swell station of the place; far and wide at one time spread its ample acres, but time bad changed all this. Small grazing farms extended throughout its leaseholds, and the bank was about to take possession of the last little spot held by young Dalton, the sole survivor of those who had been on Mindambin for three generations. His grandfather had made the station, his father had lost it, and died, leaving him a hopeless legacy.

One of the wealthiest men about there was one Edkins. He had been a fencer, and got many good contracts on Mindambin. His knowledge of the country stood him in good stead, and he soon had the choicest spots selected. Dalton awoke to the fact, too late, that his best country was being eaten away from him. He borrowed money to select in his turn, and then the ruin commenced. Young Dalton returned to the station to find everything going to the devil, and his father drinking heavily.

Edkins, the ex-fencer, throve mightily. Watkins and he had been former workmen, and the oldest inhabitant hated him cordially. Yet, strange to say, Bell Edkins, the youngest daughter of the family—a pretty girl of 18—was one of the only two beings that the old man entertained any feelings of kindness for. The other was young Frank Dalton. To both he retained his surly, defiant manner; but he would have done anything in his power to serve them. The self-made Edkins and himself never met without snarling. It galled the former bitterly to be addressed as Jim, with an insolent familiarity that sharpened the sting; but he could not help or avoid it. Nothing short of death would have stopped old Watkins; and he seemed tougher the older he grew.

The old man had massed his chance of making much money, but he possessed some allotments which rendered him independent. Poor Frank Dalton had fallen deeply in love with Bell Edkins, and as he was likely to be a pauper in a few weeks, there was not much chance of his suit being successful. It was right enough as far as Bell herself was concerned; but Edkins would not think of such a thing. Although nothing open could be brought against him, he knew in his heart that he had deeply injured his old master, and hated his son accordingly.

WATKINS stood in the main street, looking out for some

amusement. Mary Edkins, the eldest daughter, came riding down

with a man in attendance. She was a most distinguished young

lady, and had spent two seasons in Sydney, where, according to

her own account, she had made many conquests. She was bound for

the store, near where Watkins was standing, and had to pass

him.

'Good morning, Mary,' said the old man, affably.

'Be kind enough to address your betters properly.'

'Oh! This comes of going down to Sydney and mixing with dooks. I suppose you didn't tell them that you used to go barefooted the first ten years of your life?'

Mary muttered something about telling her man to horsewhip him, and escaped into the store, accompanied by the old man's mocking laughter. Bell then put in an appearance, having been delayed behind her sister. Her too the old man greeted by her Christian name, but there was a note of affection in it.

'He's going to Coolgardie,' he said, approaching. 'He'll have just enough to pay his passage, and something in hand when he gets there.'

Bell nodded and blushed. She did not need to be told who 'he' was.

'Keep your heart up, little one. I'll manage that you see him before he goes.'

Bell followed her sister into the store, and the oldest inhabitant chuckled. Soon afterwards he saw Frank Dalton, and had a long conversation with him.

'It's the best thing you can do,' he said. 'New South Wales is played out for a poor man, and you'll have to keep your eyes open for a man named Davis who was land clerk here. I'm not in a position to say for certain, but I'm pretty sure that there was some hanky-panky work about those three valley selections. Davis was Edkin's tool in the matter, and I believe he played up with the books and then got money to resign. I heard that he was seen over in West Australia, but as likely as not he has taken another name. It's only a fluke whether you meet him, but remember, he's a man about your height and build, dark, with a white scar on his left temple, and a bracelet tattooed round his left wrist. Rogues are sure to fall out, and I expect he'll give you all the information you want, as he's safe enough over there.'

That the lovers met and vowed eternal fidelity need not be told, and Frank departed in search of a doubtful fortune, and Bell remained to wait.

FORTUNE did not come near Frank. All sorts of other things did. Fever and hardship and bad luck. Now haunting the very outskirts of the field; now in the centres, he made enough to keep himself from starvation, and through it all he kept his eyes open for ex-land clerk Davis, but he never saw him. Making a small rise, he went up to the northern fields, but only to be dogged by the same misfortune.

Meanwhile things had not gone very happily with Edkins. One daughter had married against his will, Mary had developed into a shrewish old maid, and the two sons were repeatedly bolting off the course. Financially, he was as prosperous as ever, but Bell, who had changed to a very staid and sober maiden, was his only help and consolation. Naturally, the oldest inhabitant had acted as post office, and the lovers had the melancholy satisfaction of exchanging bad news.

At last, after two years, the time came when Frank had to go east or die; repeated attacks of fever had brought him very low. Fortunately, he had made enough money to pay his passage, and he landed in Sydney a broken man, without hope of any sort. He went to a mean and shabby lodging, and wrote to old Watkins, telling of the hopeless state of the case, and bidding Bell farewell.

By return came a letter containing a cheery message from Bell, and an enclosure of £60 from the old man, who urged him to accept it, as he had no use far his savings, and no relations. This somewhat cheered Frank up, and he started on a search for work. He was lying reading one night, when he heard restless groans from the next room.

He got up and went to the door of the room, and receiving no answer entered. A man lay on the bed, evidently suffering from a course of heavy solitary drinking. The eyes were bloodshot, he shook the bed with his trembling, and he seemed unconscious of the stranger's presence. Frank spoke to him, but got no answer; so putting a wet towel round the sufferer's head, he went to the nearest chemist for a strong sleeping draught. Returning, he induced the man, after some trouble, to take it, and watched by him till it took effect.

As he looked at the unconscious man, a strange thought came over him. Was not this the very man whom he had looked for in the outskirts of the desert, in the most remote and outlandish places; here he was, next door to him in a cheap boarding-house. There was the scar on the temple and the tattooed bracelet round the wrist.

He told the people of the house that he was an old friend, and they, nothing loath, let him nurse the drunkard back to life and reason.

'What is your name?' said the sick man to-him, after he had been gazing curiously at him for some time.'

'Dalton.'

'Your father lost everything, then?'

'He did.'

'And I was the cause, or at least was bribed by that fellow Edkins to alter the dates in the book. He paid the first amount he promised me, but I have not been able to get anything from him since. He had me under the whip.'

'I have been looking for you all over West Australia. If you will make a declaration of what you have told me; I think I can assure your safety and bring Mr. Edkins to his knees.'

'Who told you there was anything fishy?'

'Old Watkins

'Ha! he's a sly old dog. Well, it can't do me much harm, for I'm nearly played out, and it will be revenge on Edkins.'

WATKINS undertook the task of settling with Edkins.

'You see here, Jim,' he said, while the man writhed, 'honesty is always the best policy in the long run. Now, we'll deal fairly with you. Bell's a charming little girl, and Frank's one of the right sort. Give the young people a start, and we'll cry quits. There'll be a lot of dirty water stirred up if you don't. Lord, what evidence could not I give.'

Edkins took the advice, and the oldest inhabitant saw his long-cherished project fulfilled.

THE English language does not contain sufficient objectionable adjectives to adequately describe old Monson. He was simply a human blister who made life unbearable, not only for himself but for all those who had the ill fortune to be forced to put up with him. He lived seemingly for one object, to find fault with anything and everything, with anybody and everybody.

The family of this amiable old gentleman consisted of his wife, who took her daily bullying as an unfortunate dispensation of Providence which was not to be evaded, and without which, indeed, she would have felt uncomfortable; a daughter, who, fortunately for herself, was a chip of the old block and held her own valiantly, having, moreover, the advantage over her father of a woman's greater fluency of speech; there was also a son, adrift in the world somewhere, for, after putting up with his irascible parent for many stormy years, Tom Monson had shaken the dust of his childhood's home from off his feet, and that home knew him no more. He had faded away into that vague region known as 'up country,' but whenever a bank was stuck up, or a particularly notorious swindle perpetrated, old Monson always informed his wife that the culprit was their son Tom under a false name. This was a very ingenious mode of torture, for if there was anything in the world the poor woman had left to cling to, it was Tom, or his memory.

Cornelia Monson was by no means a bad-looking girl, although, as before stated, she inherited her father's temper in addition to the share Nature had bestowed on her by right of sex; consequently she did not want for admirers. Tom having been cast into outer darkness, it seemed fairly patent that Cornelia would eventually come in for the old man's money, which was reported to be considerable. So many bold men ignored the obvious fact that the young lady had the makings of a very pretty spitfire in her, and laid siege to the affections of Miss Monson. As the damsel was not in possession of what is popularly supposed to be a heart, it came about that the favoured suitor was an elderly widower of means, a man after her father's own views, a recommendation sufficient to condemn anybody. Her mother's opinion was not asked in the matter.

Everybody who knew Monson predicted that he would depart this life in a fit induced by an outbreak of temper, and for once what everybody said nearly came true. Cornelia had been married nearly six months, when a stranger called one morning at Monson's office and intimated a wish to see that gentleman. He was a sunburnt, keen-eyed man of sinewy' build, who gave his name as Hazel.

'I have the pleasure of knowing your son Tom,' he said, when seated opposite Monson.

'Then, sir, I cannot compliment you on the choice of your acquaintances, retorted the old man, fiercely. 'If he owes you any money you won't get it out of me, I can assure you.'

His visitor was quite unmoved.

'Tom does not owe me any money; on the contrary, I owe him my life, which he once saved at considerable risk to himself. I was led to understand that your opinion of him was a most unjust one, and that you were quite undeserving of such a son; but for all that I have come here to say what I intend to say.'

'Did that disgraceful scamp dare to insinuate that I did not deserve to have a son like him?' bellowed Monson.

'I say so,' returned Hazel, 'but keep quiet; an old man like you should know how to behave himself.'

Monson choked with ire, and stared at the cool intruder with eyes nearly starting from their sockets. The other leaned forward in his chair and shook an audacious forefinger at him.

'Tom is as fine a young fellow as there is in Australia, and I am here to-day without his knowledge, for he is far too proud to approach you himself.'

'Finish what you have to say, quick!' gasped Monson.

'Tom would be on my place now; but I have suffered the fate of many more, and my station has been foreclosed on.'

'I am delighted to hear it,' interrupted his listener.

Hazel went on unheeding. 'We are now off together to try our luck at the new gold-fields in Western Australia, and, as you may suppose, cash is not too plentiful. Considering that your son has never received anything from you but unmerited abuse, I think it is only just that you should open your heart, or your cheque book, which I presume to be the same thing, to the amount of a hundred or two, to give him a start. I undertake to say that if things turn up trumps, he will pay you with interest.'

'You undertake to say! A bankrupt squatter! Now, listen to me; if you have quite finished.'

Hazel intimated, with perfect calmness, that he had.

'Then all I have to answer to your insolent request is, that if Tom were waiting for the rope at the foot of the gallows, and a hundred or two would save him, I would not find it. He was a disobedient, rebellious fool from his boyhood. This is what I will do,' he went on, with somewhat unnatural calmness. He paused, took a shilling from his pocket and laid it on the table, Hazel looking on with a scornful smile. 'Give him this, all he shall ever have from me, unless'—and once more he paused and laughed, harshly and discordantly—'unless be can turn this shilling into a couple of thousand pounds with in twelve months. I will put a clause in my will that, if by the aid of this shilling he can make two thousand pounds within the next twelve months, I will leave him all I die possessed of.'

Hazel picked up the coin.

'I had not intended to tell Tom of my visit, nor what a low brute you have become. Now I will, and give him this'—and he put the shilling in his pocket. 'I have not yet told you that your son is married and has a child—your grandchild. It was to get some ready money to leave with his wife that I made this application.'

He stopped and looked hard at the other; but in the sullen, scowling face of the old man there was no sign of relenting.

'I dare say, went on Hazel, 'that I can fix things up financially without your assistance, although I am only a bankrupt squatter. It is lucky that I am not your son instead of easy-going Tom; for I would take you by the scruff of the neck and shake you until the money jumped out of your breeches' pocket.'

Speechless with fury, Monson lifted his fist, and brought it down with a crash on the little hand-gong.

'Turn this man out!' he roared to the clerk, who came hastily in. The clerk smiled sadly, and, glancing at the stranger, rubbed his hands apologetically, as if he did not quite understand the order in a literal sense.

Hazel laughed. 'Good morning, 'Mr Monson. You'll go off in a fit one of these days if you don't keep your temper under,' he said, as he walked out of the room.

Then Monson let loose the vials of his wrath upon all and sundry of his dependents, and when he had cursed them to a standstill he went but and ate a hearty luncheon.

Next he visited his lawyers, and finally, when he went home in the evening, he had the fit that everybody had long predicted. All through a weary night he fought with death, at intervals vainly trying to say something, to utter words his disobedient tongue refused to form. As nobody could understand the strange language that came bubbling inarticulately from his lips, nor read the unmeaning strokes; and dashes his useless fingers tried to write, his message remained undelivered until the morning, when Death let him off for a time.

A very different Monson got up out of the bed where he had had such a tussle for his life. True, his fits of rage were worse than ever, but that was because he found his memory failing. Sometimes he could not remember from the morning to the afternoon, and at other times he was quite his old self again. Gradually his son-in-law, the man after his own heart, and not very far off his own age, slipped into his place in the office, and by the time the next fit came, and Death was the victor, had pretty well got the reins of power into Iris hands.

Mrs Monson had positively kept a secret from her husband during the last months of his existence, for she had actually seen Tom when he was in Sydney with Hazel, and not alone that, but had made the acquaintance of Tom's wife and taken a great liking to the girl, and never mentioned it to her husband. The secret was also at first jealously guarded from Cornelia, as well as the fact of Mrs Tom's residence in Sydney. For Cornelia was rapidly developing into one of the shrewest of shrews—a feminine reproduction of her father, as her husband, the more than middle-aged Mr Witton, knew, to his cost.

When Monson's will was brought to light the curious clause last inserted relative to Tom caused some discussion. The old man had made a fair provision for his widow, the bulk of his fortune going to Cornelia, provided that absurd last clause was not fulfilled. Witton treated the matter scornfully, as something that could be easily set aside on the plea of unsound mind, but his lawyers were not very hopeful. Nay, they were so unkind as to point out that if Tom heard of the will and his father's death he might find an unscrupulous speculator to advance the necessary two thousand pounds; and this, with a plausible story, might necessitate a compromise at any rate.

This made Witton and his Cornelia very uneasy, and they prayed earnestly that Tom might be located beyond the reach of any news of any sort. Judge, then, of Cornelia's dismay when she found out, by accident, that not only was there a Mrs Tom and son in Sydney, but that the traitress—her own mother—was on terms of close friendship with the enemy. Needless to say their efforts at secrecy had all been thrown away, as Mrs Monson, senior, had told Mrs Monson, junior, everything; and, of course Mrs Monson, junior, had written to her husband all about his father's, death and last will and testament.

Having been told to hold her tongue for thirty years of her life, Mrs Monson, senior, had, on becoming independent, developed hitherto, undreamed of resources of garrulous loquacity. Her loose tongue revealed the existence of Mrs Tom to her daughter, and Cornelia's keen cross-examination did the rest. The Wittons had a very uneasy time of it, and nobody ever more ardently desired Time to hurry up his hour-glass than did this worthy couple.

ONE glorious star blazed in the east, killing with its brilliancy the lesser lights around—the star of Lucifer, the beautiful, radiant forerunner of the morn. Underneath it the horizon was brightening with the first cold, grey light of dawn, soon to change to warmer tints of pink and glowing scarlet.

In the growing light the silhouette of a low range was visible, a square topped range cleft here and there with jagged rifts. This vanished as the sun rose, and when daylight grew strong nothing was to be seen but the hazy line that marked the limit of sight on what appeared to be a boundless plain. An unhealthy-looking plain. A plain which seemed to have been afflicted with the mange, for spinifex grew on it in patches only, leaving naked, pebbly spots uncovered with any growth. Two men who had been riding during the late watches of the night looked weariedly at the desolate outlook before them.

'How far do you reckon that range is we saw just now?' said Tom Monson.

'Between twenty and thirty miles,' returned Hazel.

'It's a bare chance that we may get a rock-hole there, but it's ten chances to one that our horses give in first.'

He looked anxiously around as he spoke. Suddenly his gaze became! fixed on one point, and with, an exclamation he drew his companion's attention to a column of smoke rising, apparently, only a few miles away.

'White smoke by Jove! That means, grass; spinifex always burns black,' said Hazel after regarding it for a few minutes.

'May be only niggers travelling,' suggested Tom.

'Possibly, but there may be a dip in the country which prevents us seeing the timber, if there is any.'

He was right. A short five miles took them over an imperceptible rise, and before them lay some scattered patches of mulga with the filmy white smoke rising from their midst. Here they found a low mound of granite and at its base the remains of what had once been a fine supply of water in a rock hole. So scanty was it now that it barely sufficed to relieve their thirsty horses and fill their water bags. Some blacks had camped there the night before and one of their fires had ignited the short dry mulga grass; fortunately for the two men, who would otherwise not have found the place.

The horses watered and turned out and their meal finished, the two friends discussed the situation.

'If we go on,' said Hazel, 'and get no water at the range we are done for, as there is no more here to help us back.'

'I've brought you awful bad luck, old man,' returned Tom. 'Here we are on our beam ends. We have not made five pounds since we came here, and now this prospecting trip appears likely to put the finish on everything.'

'Don't whip the cat. I don't like turning back, but it is a great fluke to go on.'

'I wonder whether that range we saw is the one the fellows were talking about.'

'What about the fellow coming in with the specimens, and then going out again and never coming back?'

'Yes, he brought in some yarn of a range.'

'Well we must speedily settle the question of going or turning back. Which is it to be?'

'We're dead, broke, so it does not seem much use going back; but, then, our luck is so bad, that we shall probably come to grief if we go on.'

'Let's toss up for it.'

The two looked at each other and burst out laughing.

'We haven't got a coin between us,' said Hazel, as though it were a brilliant joke.

'Stay,' said Tom, gravely, 'I have a coin.'

'What! The shilling!'

'Yes; I have stuck to it.'

'We shan't get much luck out of that; but never mind, up with it. Heads, go on; tails, turn back.'

Tom spun the coin, and it fell jingling on the flat rock.

'Heads it is,' he cried stooping down.

It was a characteristic of the men that as soon as the oracle of chance had decided their movement not another word was said about going back. The horses were soon packed and saddled, the last drop of water scraped out of the hole, and a start made about noon. That night they camped in a scanty patch of scrub, with short commons of water and little feed for their horses; Next morning the low range rose black and forbidding in front of them. Tom seemed depressed by the desolation around, but Hazel was in high spirits.

'I dreamt of your governor last night, Tom. He looked as black as thunder, so I think there's some luck for us ahead,' he said.

By midday they were, at the foot of the range, which was of inconsiderable height, with low scrub growing over most part of it.

'Right or left?' asked Tom, as they sat on their tired-out horses and gazed at the gloomy, lifeless wilderness before them.

'Toss again,' returned Hazel with a reckless laugh.

Tom took out the fateful shilling and clapped it on his thigh.

'Heads, right; tails, left!' cried Hazel.

'Head again,' said Monson, uncovering the coin.

Hazel turned to the right and rode slowly on; skirting the scrub. Tom drove the pack horses after him. On one side a barren desert on the other a stony thicket. So they kept on until the sun sank low, and it was evident that unless they soon came to water their horses would give in.

THE sun was about an hour high when Hazel pulled up and waited

for his companion.

'I am going to see if I can get up the range to look around,' he said; 'but I am afraid the scrub is too thick to see anything.'

He dismounted and went into the scrub. Tom sat down and lit his pipe. He had become pretty well acquainted with adversity, but this seemed about, the tightest fix he had yet been in; and the worst of it was that Hazel was in it too. The man who had, stood by him always.

Suddenly a melancholy, wailing note sounded above his head, and there was the beat of broad wings—wild geese and flying low.

He sprang up, and was just in time to seethe last two or three birds disappear over the scrub. He shouted and called loudly. In about ten minutes Hazel returned.

'Can't get a sight at all,' he said. 'What were you singing out for?'

'A flock of wild geese went overhead; they were flying quite low, in the direction we are going, only a little to the left. I don't believe they were going half-a-mile away; let's go on while it's light.'

'There must be a salt lake about,' returned Hazel, as he mounted and rode on.

Suddenly the scrub rounded away to the left following the range, which, also turned abruptly. Hazel was right, and so were the geese. Before them lay the salt lake, a broad belt of mud with a centre of clear water, which was covered with wild fowl. On one side some desert gums showed where a small creek found its way from the low range to the salt pan, for the lake was little more. In this watercourse they were lucky enough to find a small soakage spring of fresh water, quite sufficient for their wants.

Both men slept the sound sleep of fatigue and relief that night. In the morning Tom, when he returned with the horses, remarked that they were not the first party that had passed the salt pan, as there were old horse tracks about. The range being no distance away, they started for it on foot, so as to make a close examination of it and see if the country was worth 'trying.'

About half a mile from their camp they came to a larger water hole than the one they had struck the night before. Here was also an old, torn tent, still standing, though sadly rent and damaged by the wind. By the look of the tracks, no one had been there for some weeks. The hobbles for two horses were lying on the ground, but neither saddle nor pack horse could be seen. In the tent were a pair of blankets and a good supply of rations; but the surrounding desert held the secret of the mystery of the disappearance. Some unhappy wretch it must have been who, after a long search for fortune, had fallen with the prize within his grasp, for in the tent were several rich specimens of stone.

'Tom,' said Hazel, 'we have got to stop here until we find where these came from. I think it's a good way off, by the look of the country, but it is evident that this is the nearest water.'

'How about the owner of them?'

'It's too late, I'm afraid, to look for him: it must be weeks since he left this camp.'

THREE weeks after that Hazel and Tom were gazing admiringly at

some specimens from what promised to turn out one of the richest

reefs in the district. In another three weeks the place was alive

with men and eager agents of Eastern syndicates were offering

large sums for a share in the famous 'Shilling Reef' as it had

been named, in honour of the coin with which Monson had cut off

his only son.

'Tom,' remarked Hazel, about this time, 'if that stern parent of yours, whom we can afford to laugh at now, really inserted that clause he spoke of, I should imagine that your claim to his property at his death is indisputable.'

Tom, who was slow, looked in enquiry.

'Why, was it not by the aid of that shilling we got here, and dropped on, this reef; and isn't it worth, a good deal more than two thousand; and the twelve months is not nearly up yet?'

Two days afterwards one of the intermittent mails common to new goldfields arrived, and had received letters which put him in possession of the information that his father was dead, and had inserted the clause in his will.

IT is one of those perverse things so characteristic of this uncertain life that after devoting many busy days and sleepless nights to the accomplishment of one object, another man, by a mere fluke, steps in and snatches the coveted prize from within an inch of our grasp. Certainly, that was the feeling of Mr and Mrs Witton when the fame of the 'Shilling Reef'—considerably exaggerated, of course—was duly wired over to the eastern colonies, together with the names of the discoverers.

Neither of them doubted for an instant that Tom would avail himself of the windfall to claim his inheritance. Already a garbled and distorted story of the romantic finding of the reef and the mysterious fate of the first prospector had gone the rounds of the papers, and the public sympathy would probably be in favour of the disinherited son, should the case ever come into the courts. Even if the most favourable view were taken it would mean an interminable lawsuit, which would swallow up the best part of the estate. Under the circumstances, it was evident that a friendly compromise would be the best thing.

Here, however, they had to reckon with Mrs Tom, whom Cornelia, unfortunately, had treated with contempt and neglect. Naturally she resented the sudden attempt at friendship inaugurated on receipt of the astonishing news from the west, and was evidently determined to use her influence to make Tom insist on his rights. Matters were in this state of doubt when Hazel persuaded Tom to take a trip home, leaving him to stay and watch over the development of their property; and Tom, nothing loth to return a rich man, in prospect, to the spot where he had most undeservedly been exiled, consented. His presence was expected with much anxiety by the people interested.

Three months still had to pass 'ere twelve months from the signing of the clause elapsed when Tom stepped ashore at Sydney, and was received with rejoicing by all his relatives and friends, who quite ignored the previous, cold shoulders they had offered him.

Everything went on smoothly and on greased ways, until a thunderbolt suddenly burst in the shape of a telegram that the original prospector of the 'Shilling Reef' had turned up and laid claim to the ground held by Hazel and Monson. His story was that, in making his way to the nearest camp to report the find, he had lost his way, killed his horses, and nearly died, himself. He had been rescued by some natives, and had lived with them until the rain fell, and he was enabled to get back on foot.

The yarn had a new chum flavour about it that rendered it somewhat unworthy of credence. Under the strong circumstances, the deputy-warden referred the matter to headquarters for consideration, and the result was that, as the twelve, months was drawing to a close, the title to the mine was in dispute. Although there was little doubt as to how the affair would end Tom would not be in a position to say. He was in undisputed possession of two thousand pounds unless the case were speedily decided.

Urged on by the infatuation of greed, the Wittons now scorned the idea of a compromise of any sort, and gave Tom to understand that he was nothing more or less than a daylight robber.

Witton was seated in his office, lording it after the style of the deceased Monson, when Tom was announced. As it was now only a matter of days to the end of the year, he naturally jumped at the idea that Tom had come to beg for a settlement of some sort. But he was rather undeceived when young Monson, whose somewhat sluggish nature could be roused on occasions, strode in with his hat on, and, throwing a telegram on the table, said fiercely—

'There, you infernal scoundrel—look at that!'

Witton took it up with shaking hand, for he guessed, that he had been bowled out, and for good.

'It strikes me that there's something like a good sentence of penal servitude hanging to that,' went on Tom, sternly, regarding his trembling enemy.

OUT at the 'Shilling Reef' Camp Hazel was fuming, and

inactively waiting for the expected decision which, of course,

could have been given at once, when he was accosted one day by a

new-comer on the field, one of his old station hands, who had

lately arrived from the East. Jim Blackwell and his mate had been

just as unlucky as his former employer at the start, and was what

is popularly known as 'dead broke.' He had been years with Hazel

in the old days, and naturally the latter at once helped him and

advanced him enough to keep him going until times changed.

A few days afterwards he came hastily into Hazel's tent, and, collapsing on to his stretcher, began to laugh as though he had come across the finest joke out. Hazel concluded that he had made a lucky find, and, accordingly asked the question, at the same time becoming conscious that there was an unusual stir and bustle in the camp.

'They going to hang that fellow who claims the reef,' he admitted at last, for he could hardly speak for laughing.

'Hang him—what for?'

'Dick and I spotted him for the first time, this morning. God bless you, he came over in the Australian same time as we did!'

The noise now increased, and Hazel thought it was about time to go out and take a hand.

'It's all right,' said Jim, as they went towards the crowd. 'They only intend to give him a jolly good fright.'

The man had been fool enough to talk big and flourish a revolver, so he had been a little roughly used and his nose was bleeding, which did not improve his personal appearance, although even an innocent man does not always look innocent under the pressure of circumstances. Hazel, whose genial way and open handedness had naturally made him popular in the camp, was hailed with congratulations on his arrival. The culprit, who was without tact, continued to bluster, and accused Hazel of setting the men on to him.

'Divil a tree is there tall enough about here,' said a big Irishman, who might have 'stood' for Terence Mulvaney.

'Let's put him against a tree and practice at him,' suggested another.

'No, I'm bint on the hanging,' returned the Irishman. 'There's a mulga there will about take his toes off the ground.'

Immediately the crowd started for the tree indicated; a sailor struck up a shanty, and the rolling air was taken up by them all as they marched along, the culprit in their midst.

By the time they had reached the tree, the poor devil's tune had quite changed. The Irishman had fixed up a noose on the end of a rope as they went on, and he threw one end over a branch and put the loop round the neck of the man, who was now begging and praying for mercy, and entreating Hazel to save him. Some of the fellows tailed on to the end of the rope, and the Irishman said, 'Wait till I give the word, boys.'

'Suppose we hear what he has to say first?' suggested Hazel, solemnly.

'That would be more satisfactory,' returned the other. 'Sure there may be some more scoundrels mixed up in it. Now make a full confession,' he said to the trembling wretch.

'I was put up to it in Sydney by a man named Witton. He paid my passage, gave me all the details, and found me in money. I was to get a couple of thousand if I could keep the case stringing on for a certain time, on one excuse or the other, I was hard up, and the times are very bad in Sydney, so I did what a good many others would do, in my shoes.'

This was the gist of what he said.

'Is this a true yarn, think you?' said the Irishman to Hazel.

'Yes, it fits in right enough. If they could have kept this trumpery case going for a certain time my mate Monson would have been cheated out of his father's money. This man Witton is his brother-in-law.'

'Then it strikes me as he is the man as should be hanged. What do you say, boys? If he takes an almighty oath to clear straight back to Sydney and bate the life out of old Witton, shall we give him a run for it?'

There was a general assent, and the Irishman was about to let him go, when Hazel asked if the man had enough money to take him back. He had.

'Then be off, and the sooner you're out of this colony the better, for you'll be known from Dundas Hill to Kimberley before very long.'

Amidst a prolonged howl and much noise, the culprit was allowed to pack up his traps and go; and, as there had been a few showers lately, the road was in good travelling order.

This was the substance of the telegram Tom received the morning he confronted his brother-in-law. Needless to say, Witton, after a very brief show of resistance, collapsed and allowed Tom to dictate his own terms, which were far too generous in the eyes of Mrs Monson, junior.

The 'Shilling Reef,' according to latest accounts, is keeping its record and going down in a most satisfactory manner.

George Pichrel was brought up at the Water Police Court, Sydney, for a violent assault on Mr E.L. Witton. The accused pleaded guilty to a common assault, and paid the fine, although the arresting constable stated that the assault was of the most savage character, and that it was with difficulty that he dragged the accused off his victim. The prosecutor, however, expressed himself satisfied.

The newspaper containing the above account was duly forwarded to Hazel, and read with great glee to a select circle in a far-off mining camp in Western Australia.

BENSON was the undisputed magnate of Berringawatta—he had risen to that dignity by industry, and an eye to Number One. He commenced with the township as a humble saddler, and had grown with it to greatness. Some of his old friends of early days pursued the undignified avocations about the town that men who have come to grief fall back on, but this did not trouble Benson. They should have kept their money when they made it; consequently Benson gave them the cold shoulder, and did not see his way to any small loans for the sake of old times.

In this Benson was wise. He was the owner of many corner allotments, and many men called him master. He was Mayor, and at the coming change in the Electoral Act he intended to put up as member for Berringawatta. But as Benson stood at the door of his own prosperous store looking on the usual objects to be seen in the main street he was a man, sad at heart. The fact was that Benson's social manners had not kept pace with his rise in the world, and he knew it. He had endeavored to rectify it by employing an ex-college man, given to rum and romance, as a tutor, but he had lately begun to entertain, wild suspicions that this man, inspired by the devil, was taking a rise out of him.

Benson began to think of getting married as a better investment, but there, too, he was puzzled. He had his pick of the district certainly, but he doubted if the local beauties knew much more than himself, and if he went abroad in the world he might be taken in. Still, as he was determined to rise out of the little local world he lived in, something had to be done. His cheeks burned when he recalled the fearful blunders he made, in his confusion, at the Premier's visit. How he three times addressed that plebeian-looking individual as 'Your Majesty.'

He sacked the ex-college man that day, for that dazed individual in a pot-valiant state of mind, had told him that it was fashionable in the best society for men to wear diamond earrings. Benson, although ignorant in some matters, was not by any means a fool, and the tutor straightway found himself homeless and liquorless.

'I've suspected you for some time,' said Benson, 'and the first time I catch you tripping I'll log you like a shot.' So the M.A. subsided into nothingness once more, rather the worse off by some debts he had contracted during his short spell of tutorship.

Benson then looked with a worried eye upon the world, as represented by the main street of Berringawatta.

At last a bright and happy thought occurred to him—he would consult Mrs. Gonsalvo. The lady in question resided in Berringawatta, her husband having left her a good deal of property there. She was too old for his motives to be misconstrued, and she had always been a good friend to him, he thought. She was supposed to be very well connected, and spent a portion of each year, regularly, in Sydney. She also had the reputation of being clever.

Benson consulted the old lady, who seemed highly complimented at his applying to her for advice, which, after some delay, she gave him in plain terms.

'I quite agree with you, Mr. Benson, that a smart, capable wife, a lady who knew her way about, would be the very thing, would be the making of you, but though there are hundreds knocking about, the difficulty is in finding one. You scarcely would get what you want by going about with a placard on your breast stating that you were a man of property, wanting a wife; you would be the mark for every adventuress, and they would assuredly take you in, my poor Benson.'

'I believe they would. A man is really no match for some women.'

'My friends are all old fogies like myself, so I cannot help you by any introductions, but I will do something for you. I am going to Sydney as usual next month, and I may hear of somebody who would make you a good wife; if so I will let you know.'

'Yes, Mr. Benson, I'll find you a wife,' said the old woman to herself as he left, 'one that will comb your hair for you; the impudence of your coming to me, as if I cared what sort of thing.'

In point of fact, the old woman was a malevolent old witch who had a special down upon Benson on account of some fancied lack of politeness. Benson had delivered himself into the hands of the enemy without doubt. In course of time the message came, and Benson departed to Sydney, prepared for conquest. He went to call on Mrs Gonsalvo the first thing, and found that lady all smiles.

'The very woman for you, Mr. Benson. She's a widow—' Benson made a wry face, '—and comes of a distinguished Irish family.'

Benson's face grew still more elongated. He didn't quite like widows, but he didn't say so.

'She is stopping at present at a very refined boarding house in M—street, and I should advise you to take a room there, and then you have a fair field and no favor.'

Benson proceeded to the refined boarding house, kept by the usual scraggy lady widow, and secured a room there. At dinner, which was refined down to starvation point, Benson met the widow, Mrs Fitzgerald, and was introduced to her after the fashion of refined boarding houses. She was middle-aged but comely, well-dressed, and excessively reserved in manner. Benson was rather taken.

HE was sauntering about town next morning when he was hailed

by a voice he knew, and young Matson, the owner of one of the

stations about his district, advanced to meet him, accompanied by

a friend.

'Hallo, Benson! You down on a spree; how are you? This is my friend Mr. Willow; Jack, Mr. Benson's too haughty now to do such things; but at one time he could make as good a rough saddle as anybody.'

From anybody else Benson might have resented this, but Matson was a privileged man.

'Where are you staying?' asked the latter.

'At Mount de St. Clair, M—street,' said Benson, proudly.

'God help you,' was the answer. 'I know those places—a box of sardines, cheese, and flowers for lunch, two grass widows and a young man who vamps the piano. Come and have a drink.'

They went, and it struck Benson what a fool he was not to have consulted Matson instead of Mrs. Gonsalvo. Matson knew everybody, good family, careless devil but perfectly honest and straightforward. Was it too late? He might still take him into his confidence. He obtained Matson's address, and promised to call and see him.'

That evening he made great progress with the widow, on the strength of their mutual friend Mrs. Gonsalvo, and began to think very highly of her. In a day or two their relations had become intimate enough for him to propose a visit to the theatre in company with the mistress of the refined boarding-house, which was graciously accepted, and that afternoon, he met Matson.

He felt in a confidential humor, and, in want of guidance, and after swearing Matson to secrecy, he confided to him that he was in search of a wife, and how far he had proceeded.

'Mrs. Gonsalvo? I know the old cat of course, hates me like poison. What on earth made you go to her?'

'She has behaved most kindly, I assure you.'

'Has she? Well, it's the first time I ever knew her do such a thing. My dear Benson, you would be much better standing on your own merits, just as you are, and waiting for the right woman to turn up. I don't believe in widows who live in refined boarding-houses. Better ask me to dinner tonight.'

'Will you come? I will be delighted.'

'All right, I will come.'

Matson came duly, and it was a good-natured act to leave his own good dinner for the refined boarding-house one, but he was good natured. Mrs Fitzgerald was nervous that evening, and once or twice dropped into what sounded like a brogue, but it was not very pronounced.

'I've seen that woman before, somewhere,' said Matson, when up in Benson's room, superintending that man getting into his dress clothes, and cutting him down in the matter of studs and rings. 'But if you want my disinterested opinion, Benson, she drinks.'

'Drinks?' echoed Benson, aghast.

'Yes, she had a drop too much to-night. You lay low, old man, and she'll come out in her true colors.'

Matron departed; and Benson passed an unpleasant evening, although Mrs. Fitzgerald behaved with the most perfect propriety.

'LOOK here, Sarah,' said Mrs. Gonsalvo, in tears in Mrs

Fitzgerald's room the next day, 'It's too bad after buying you

dresses and paying your board here, that you couldn't keep

straight long enough to catch that silly, vulgar fool.'

Mrs. Fitzgerald, lightly and airily attired, arose from her bed.

'It's ould Benson, is it? And what was the good of keeping up the play-acting after that divil Matson had seen me. Shure he knew me when I was barmaid at the Shearers' Arms, but he couldn't place me. No, old Gonsalvo, me husband was an M.A., or he used to say so, and do you think I'd disgrace his memory? There's four bottles of lovely whisky in that cupboard, and I'm going to have a right, royal spree on it, and wreck this old caboose afterwards. Whoop!' and she gave vent to a yell that made Mrs Gonsalvo shudder.

'Besides, I don't know whether me husband is dead or alive, and I'll be surely had for trigometry or something if I be doing your dirty work.'

Mrs. Gonsalvo departed in tears, and Mrs. Fitzgerald arrayed herself in purple and fine linen and sailed out with a very red face.

The first persons she met were Matson and Benson, and she boisterously saluted them.

'You remember me at the Shearers' Arms, don't you?' she said to the former; 'sure its many a time you were there. I married that worthless wretch M'Ginty, M.A. Is he alive or dead?'

'Good God!' said Benson, for M'Ginty, M.A. had been his late instructor in deportment. 'He's alive,' he gasped.

'Well, I'm sorry to hear it; for that old Gonsalvo cat put me on to marry you, and the old thafe would have had me run in for trigometry. I'll tear the fringe off her bald head, I will.'

Benson was too horrified at his narrow escape to say much. He intimated to Mrs. Fitzgerald that if she gave him an address he would send her a cheque out of gratitude, and then they went where, as Matson said, they could have their laugh out.

'Hanged if I could place her,' he said, 'but her guilty conscience gave her away, and the whisky did the rest.'

Mrs. M'Ginty had a great spree, and brought shame and everlasting disgrace on the refined boarding house, and Mrs. Gonsalvo dared not show up again at the township. As for Benson, well, he took Matson's advice, depended on himself, was a much better man for it, and the right woman came round in time.

BEING a paper read by Professor Allinamess on the 1st of January, A.D. 2872, at the opening of the new Social Science Theatre on Central Mount Stuart. Our report is abridged from one of the newspapers of the period:—

ON Thursday, January 1, the new Social Science Theatre, on Central Mount Stuart, was opened with due ceremony. The learned professor, S. M. Allinamess, read a paper on "The Natural History of a Thousand Years Ago." The arrangements were perfect in every respect. A brilliant and fashionable audience, estimated at ten thousand, attended. The improved "sound diffusing machine," placed directly over the professor, worked admirably; though speaking in ordinary conversational tones, the learned savant was distinctly heard by every one present. Our "automaton reporter," though placed in the most remote portion of the building, recorded every word as it was spoken as clearly and rapidly as it would have done had the figure been placed in close proximity to the speaker. Every vibration of the air caused by the voice of the lecturer must have therefore been as distinctly felt by the artificial tympanum of the machine as if the paper had been read close to its ear. The following is the substance of the learned professor's lecture:—

NATURAL HISTORY is a science that the vast strides made in the use of machinery has rendered almost a forgotten and neglected lore. Amongst the many forms of creation once swarming on the earth few have survived, and, with two exceptions, they only survive in a degenerate and useless form. The only animals known to us as living in our day are horses, cattle, dogs, cats, and pigs, and what we term domestic animals, the kangaroo and alligator, and it is upon those lost to us, who but live in tradition, that I would speak.

I will here mention one fact in connection with the horse not generally known. It was formerly used for purposes of locomotion. It was ridden in the same manner as we now ride the kangaroo on land or the alligator in water; and attached to wheeled vehicles it drew heavy loads from place to place. How our ancestors could have preferred a clumsy four legged beast like the horse to the agile kangaroo seems astonishing to us. But when we reflect how little was then known of the laws of propulsion, our wonder ceases.

Those, too, were the days of carriages with four wheels, chairs and tables with four legs; everything depending for support on artificial aid; nothing known of the true principle of gravity.

To my subject:

The wild animals and birds of Australia were, it is well known, the most ferocious and savage of any country. The kangaroo and alligator alone showed any signs of a friendly disposition towards man, and they, by the ignorant settlers, were hunted down as pests.

The Jumbuck.—This, though an animal of most savage disposition, was kept in a partly domestic state by our forefathers. They kept them in large herds guarded by armed men, bribed to this perilous duty by means of high rewards; or by prisoners sentenced to death and allowed the choice of this employment. Its flesh was greatly esteemed. The origin of the name seems to be that the jumbuck was an animal partial to frisking on rocks. In the neighborhood of the Gulf of Carpentaria, where large flocks were depastured, there are few or no rocks. The alligators, knowing the jumbuck's weakness, would approach the shore and elevate its back only out of the mud. The jumbuck would approach, and seeing what it supposed was a rock, would spring on it. Quick as thought the alligator would turn, and receive the quadruped in his jaws. The guards, always on the look out for these imitation rocks, seeing the jumbuck about to spring, would cry, "Jump back, jump back!" and so the jumbucks soon learned to know the warning cry, and thence were called "jump backs," transmitted to us as "jumbucks."

The Emu, or Aymu.—This ferocious bird was of the same species as the "mower bird" of New Zealand, so called from its scythe; shaped beak, with which it could mow down several men at a time. The emu differed from the mower in having a short sharp beak and capacious throat. Even better than human flesh it liked eat, and from the mode in which it secured them derived its name. Knowing the fondness cats have for making love during the midnight hours, the emu approached the dwelling of the settler after dark, and would utter a mew of seductive sweetness. The cats, poor victims to misplaced confidence, would leave the shelter of the roof to join their lovers, as they thought, and be forthwith devoured by their relentless enemy. They were thus called "mews," and, to distinguish the sexes, "he-mews" and "she-mews." As they died out, the male's appellation got applied to both, and thus we have emu.

The Possum.—This was not an indigenous animal, as has long been supposed. It was imported from Ireland by some of the first immigrants, its original name being the O'Possum. It ran wild in course of time, and grew to a great size; in fact, so dire were the onslaughts it made on the more thinly settled districts that the inhabitants had to provide themselves with a kind of defensive armour, known as 'possum rugs' or 'possum cloaks'. They were at last got under by Act of Parliament.'

The Native Companion.—This is a mythical animal; it is now clearly proved never to have had any existence. The tradition originated thus: the black aboriginals had a superstition extant amongst them that on their decease they would arise again with white skins. On the advent of the whites amongst them, the blacks landed they could detect a resemblance to defunct relatives in various individuals, and to them would they attach themselves, and with the devotedness and truth which had rendered the name of the Australian black famous to this day, be their friend and servant throughout life. These were called by the whites their native companions.

The Laughing Jackass.—An animal which combined deep animosity against mankind with the most fiendish form of treachery. The traveller on the lonely roads of the interior would see the smoke of a fire rising out of some shady bushes. He would draw near and be rejoiced to hear the sound of merry laughter proceeding from the thicket, telling of the welcome companionship of his fellow men. Unsuspecting would he plunge into the scrub, only to form food for this monster. The peculiar formation of its legs prevented it proceeding fast along the ground; its only chance, therefore, was to lure its prey into some thickly-timbered spot. Professor Makeitworse holds the opinion that its real name was "the laughing jaguar," and as we find the jaguar mentioned elsewhere as a much-dreaded beast of prey, I consider this to have great weight.

The Morepork—A species of bird identical, it is supposed, with one mentioned in very ancient writings—the "harpey." Like the emu this bird had a favorite description of food—namely, pigs. But instead of using any art to entrap its victims, relying on its enormous size and strength, it used to enter the huts of the inhabitants and utter its awe-inspiring cry, consisting of the two words: "More pork!" A pig would be immediately sacrificed, in order to bribe it to depart. Instances even have been known in which inhuman parents have, in the absence of pork, presented the monster with a young child, in order to secure its departure.

The other domestic animals of the ancients, now extinct, were the lion and tiger, both harmless and inoffensive quadrupeds, noted for their love towards men. The lion was so domesticated that it was commonly used as a pillow, from whence it was called "lie on." The tiger also performed the part of a faithful servant. Its name is supposed to be a corruption of "tried guard," so called on account of the devoted attachment and gentleness of its character.

THE professor concluded his lecture amidst expressions of

universal satisfaction, and, the revolving walls being put in

motion, the immense audience departed without experiencing the

slightest squeezing or annoyance. The central position of the

theatre favored the presence of visitors from all parts of

Australia. Several excursionists from the Great Barrier Reef were

also present.

To-morrow, Professor Wrongend will lecture on "The Discovery of Australia," with some account of "Jackson the cook, the first discoverer," whose tragical end on board the Bounty, at the hands of the mutineer Adam Bligh, formed the subject of the most attractive picture exhibited in the Royal Brisbane Academy last year.

Editor's footnote: "Jumbuck" is obsolete Australian slang for a sheep; the common "possum" is a cat-sized tree-dwelling marsupial, a "native companion" is a brolga, a tall wetland wading bird of the tropics; a "laughing jackass" is a kookaburra; and a "morepork" is an owl.

THERE was great excitement in Askinville, a small but growing township in South Antarctica, when it was known that the Mayor and Council had actually invited the Governor-General of Antarctica to visit the town; and, moreover, that the Minister for the Department of Ice Creams and the Minister for Scrub and Sand, would accompany him, these two being the principal members of the Cabinet.

Askinville had several small grievances and more serious wants, but unfortunately there was a division of opinion on the importance of these wants. One party wanted a gaol, the other parry wanted a hospital. The first party urged that when the gaol was not required, and that would be but seldom, for crime was infrequent in South Antarctica, and offenders were generally let off with a caution, it could be used as a hospital. On the other hand, the hospital party said the same thing about the hospital. The convenience, or inconvenience, of the prisoners on one hand, and the patients on the other, did not enter into the question.

The Mayor remarked with great wisdom: 'Gentlemen, we must get this matter amicably settled before our distinguished visitors arrive, or we certainly shall get neither.'

Both parties agreed most cordially with the Mayor, and further, both agreed that the other side should give way. This left things very much as they were before, and had it not been for woman's wit, the town would hare been divided into anti-gaol and anti-hospital factions when the important visit came off. In fact, Askinville would have been in as bad a state as Dreyfus-torn France if it had not been for the brains of one shrewd little girl.

She was the daughter of the Mayor, the acknowledged belle of Askinville, and just at a sensible age, when the frivolity of girlhood merges into, the sagacity of the woman. What that age is must remain a secret. Anyhow, she had a graceful figure, plump and rounded, features more piquante than classical, and a very pretty wit. She had more admirers than she wanted, but she, no more than anybody else, could decide which was the most favored knight. Possibly she might have had a lurking suspicion, but at any rate nobody, else had.

'Mr. Conlon,' she said to one, 'I wish you'd be very ill; so I'll that the doctor (the doctor was another admirer) 'would say that you must be taken to a hospital.'

'Very kind of you to talk like that, Miss Morley, but what particular disease would you like me to contract?'

'Oh, something terribly deadly and contagious.'

'Very well. As the plague has not yet reached Antarctica, and there's no smallpox scare on at present, I'll choose typhoid; will that suit you?'

'As good as anything; don't come near me after you have got it.'

'Doctor,' said Conlon half an hour or so afterwards,' Miss Morley has instructed me to contract typhoid as soon as possible, so just oblige me by injecting some bacillus into my system, and also finding out what her little game is.'

Dr. Whetsone reached out for the whisky and a couple of glasses, and said: 'This will do for the present. I suppose she has got some idea about settling this foolish dispute going on just now as to which is most required in this town—a gaol or a hospital. Of course, the hospital is the thing, but the hospital will be a case of pound for pound—whereas, the gaol will have to be built by Government.'

'Never mind,' said Dick Conlon; 'it is evident that it is the hospital she wants, and the hospital she shall get if I have to pay most of the pounds.'

'Very well,' said the doctor; 'I'll try to find out what she intends. Meantime, drink your whisky, and consider yourself infected with the typhoid microbe.'

The doctor meditated much over this interview. As formerly stated, the doctor was an admirer of Miss Morley, and knew that Conlon was a rival in the field, and Conlon was a comparatively wealthy squatter. It's as well to say 'comparatively,' as at that time the banks of Antarctica were wonderfully liberal in the matter of overdrafts, and no question of foreclosure was ever mooted amongst them. Consequently the matter of overdraft meant a question of riches, more or less. Conlon was a squatter with assets; Whetsone was only a struggling doctor. The inequality of the combat was apparent.

The doctor consulted the damsel, and, as he expected, learned from her the scheme she had hatched in her active brain.

'I want the hospital,' she said, 'and you are going to be the resident doctor of it. Will you help me?'

Dr. Whetsone's reply need not be recorded, for of course it was in agreement.

'Mr Jackwins,' said Miss Morley to another admirer, also a man of wealth and substance, 'I want you to become a criminal.'

'A criminal?' asked Jackwins. 'What especial kind of crime would you like me to commit. Murder at the least, I suppose?'

'Exactly. Would you mind murdering Mr. Conlon for me?'

'With pleasure. He is a dear friend of mine; but, nevertheless, he is also, I now remember, a dear friend of yours, I will kill him with pleasure.'

Jackwins went away, and the first man he consulted was Dr. Whetsone.

'Miss Morley wants me to kill Conlon,' said Jackwins. 'Have you any objection to doing it for me?'

'I've done it already,' replied the doctor. 'I have just infected his system with typhoid fever, at the request of Miss Morley.'

'Then the matter is settled,' said Jackwins. 'Come and have a drink.'

When the doctor and Miss Morley met there ensued a secret conference, which cannot well be here repeated.

THE then Governor-General of Antarctica was a man who was

supremely bored by everything. He had been for a long time the

Imperial inspector of the Lost Whales of Victoria Land, and the

fatigue of sitting on the edge of an ice floe and waiting for a

lost whale to come up and show his brand, and ask him to whom he

belonged, had caused him to wear a perpetual yawn. But he was a

very good fellow nevertheless.

The Minister for the Department of Ice Creams was a sarcastic with a bad digestion, and the Minister for Scrub and Sand was a sunburned fellow who did not know he had such a thing as a liver.

These were the men who had to determine the burning question then agitating Askinville, and until their visit was paid Miss Morley and the doctor carried their plot on so nicely, that the contending factions were united, and howled, so to speak, in one voice for a Hospital.

THE eventful day arrived; the Mayor was there ready, and so was Miss Morley and with course, a most beautiful bouquet which was to be presented to the Governor-General of Antarctica in the approved and conventional manner current then when governors arrive.