RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Ernest Favenc (1845-1908)

British-born and educated at Berlin and Oxford, Ernest Favenc (1845-1908; the name is of Huguenot origin) arrived in Australia aged 19, and while working on cattle and sheep stations in Queensland wrote occasional stories for the Queenslander. In 1877 the newspaper sponsored an expedition to discover a viable railway route from Adelaide to Darwin, which was led by Favenc. He later undertook further explorations, and then moved to Sydney.

He wrote some novels and poems and a great many short stories, reputedly 300 or so. Three volumes of his stories were published in his lifetime:

The Last of Six, Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1893

Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1894

My Only Murder and Other Tales, 1899

His short stories range from bush humor to horror, supernatural to strange, and to the privations of late 19th century exploration in Australia's unforgiving inland. His first two short story books (consolidated into one volume, as there is considerable overlap), are available free as an ebook from Project Gutenberg Australia.

—Terry Walker, January 2023

I KNEW that Shenwick had been studying the occult for a long time, but being a hardened sceptic, I was not prepared to accept the wonderful progress and results that, he said, had so far rewarded him. All the experiments he essayed for my conversion had turned out failures. Therefore, when he came to me and stated that he had discovered how to resuscitate the dead, provided they were not too long deceased, I frankly told him that I did not believe him.

He was used to my blunt way of speaking, and did not resent it, but proceeded to explain how, after death, the soul hovered about the body for some time, and if you could induce the soul to re-enter the body, the late departed would be given a fresh lease of life.

Several difficulties suggested themselves to me, which Shenwick would not listen to. What, for instance, I said, if a man were blown into fragments by a dynamite explosion, how will you find and unite the pieces? If he were hanged, and his neck dislocated, how would you fix his spine up again? If he had his head chopped off—

Here Shenwick interrupted me to state that he meant only cases of natural death, the decay of the vital forces, not mangling and mutilation. He explained that the emancipation of the spirit for a short period inspired it with fresh vigor, and it came back rejuvenated and strong.

"How are you going to try your experiment?" I asked. "Corpses are not knocking about everywhere."

"I admit that is a stumbling block," he said, "but it may be got over. Would you object to putting a temporary end to your existence in the cause of science?"

I told him in language more forcible than polite that I would put an end, final, not temporary, to his existence first.

He accepted this seriously, and informed me that that would not avail, as I would not be competent to conduct the experiments.

We parted for the time, and I believe he spent most of his time searching for a fresh corpse. I know he applied at the hospital, and was ejected with scorn and derision. He also visited the morgue, but as most of the bodies that came there were "demn'd damp, moist, unpleasant bodies," they were no use to him.

"I've got him," he said, one day, stealing into my room on tiptoe as though he thought that the corpse upon whom he had designs would hear him.

"Got whom?" I asked, "the corpse you have been looking for?"

"No, he's not a corpse yet; I'm not going to make him one. Don't stare like that. He's dying, and I have agreed to keep him in comfort till he dies. He's got a churchyard cough, and drinks colonial beer by the gallon. Will you come and see him this evening?"

I said I would, and went on with my work, as he closed the door, softly and mysteriously, for what reason I know not. I went to Shenwick's that evening. He occupied three residential chambers in a large building, and found that he had given up his bedroom to the subject, who was established in comfort and luxury. As a subject, the man was probably as good as any other, but he was by no means prepossessing, and the language he used to Shenwick was painful to listen to.

"It's unfortunate, you know," said my poor deluded friend, "but since he has been taken care of and doctored, I am afraid he's getting better. Now, he would have been dead by this time if he had been left in the Domain. There was a drenching rain last night that would have finished him off out of hand."

A voice was heard from the next room, demanding beer, adjective beer, in a husky whisper.

"This is my only hope," said Shenwick, as he filled a pint pot from a keg. "The doctor says he is not to have it, but I take the liberty of differing from the doctor."

He took the beer in to his subject, and got cursed for his pains.

"He was quite resigned to death when I picked him up," said Shenwick sadly, when he came back; "but since he has been made comfortable he wants to live."

"Small wonder," I returned, laughing.

"It's no joke; by my agreement for his body I am bound to keep him as long as he lives."

"Well, we must try to upset that, if he does live. I have not seen your agreement; but, speaking as a lawyer, I should say it was not legal."

About three weeks after this Shenwick opened my office door, put his head inside, uttered the mysterious words, "Be prepared for a message this evening," and disappeared. I concluded that the subject had caved in after all, and was on the brink of the grave.

The message duly arrived before I left my office, and after dinner I went to see Shenwick. True enough the subject had departed this life, and his mortal, and very ugly, frame was in the possession of my friend, together with a doctor's certificate. He was now at liberty to conduct his experiments and prove the truth of his theory. He asked me to remain, and witness the result, to which I consented, and as he informed me that the small hours of the morning were most favourable, I took the opportunity of having a sleep on a sofa in the outer room, while Shenwick watched his beloved subject.

Shenwick woke me at about two o'clock. I got up stiff and cross, as a man generally is after sleeping in his clothes on a sofa.

"Hush!" he said, in that mysterious whisper he had affected of late. "I am now sure of success. I tried some passes just now, and I am confident that a spark of animation followed."

I muttered a tired swear word, and followed him into the bedroom. Shenwick lowered the light, and commenced his mesmeric or hypnotic hocus pocus over the dead subject. In the dim light it was a most uncanny exhibition, and the more excited Shenwick grew the more antics he cut with his hands, waving and passing and muttering.

Now what happened is almost incredible, had I not seen it myself; but that grim and ghastly corpse on the bed rose up in a sitting position, gasped and choked once or twice, and then broke out into the vigorous cry of a healthy, lusty infant. For an instant the most cowardly terror assailed me, and I confess that I had it in my mind to cut and run for it, when I noticed Shenwick, after swaying to and from, pitched headlong on the floor in a dead faint. That restored me to my proper senses, and I went and picked him up and tried to restore him.

Meanwhile the hideous thing on the bed still kept blubbering and crying. If you shut your eyes you would swear that here was a baby of forty-lung power in the room.

Shenwick at last recovered. "It was a success," he gasped.

"If you call that row a success, it was," I answered.

He listened intently, and a pained look came into his face. He was evidently greatly puzzled. "Let me go into him by myself," he said at last. I cordially agreed, and he went into the bedroom, and I solaced my nerves with a good strong nip of whiskey. Gradually the crying stopped, and Shenwick came tiptoeing out and told me that the subject had fallen into a nice, quiet sleep.

"It's awkward, very," he said; "but at any rate the experiment succeeded."

"What's awkward?" I asked.

"I left it too long. I told you that the spirit rejuvenated, grow young, after its release from the body. This spirit has grown too young—it's gone back to infancy."

"Then you'll have to rear it as an infant; but you won't find anyone to look after it in its present state."

"I'm afraid not; I'll have to bring it up by hand myself. It's hungry now, poor thing. Isn't there a chemist who keeps open all night?" I directed him to one, and he asked me if I would mind looking after it while he went out and bought a feeding-bottle and some food. "If it cries, try and amuse it," he said, as he left the room; and I heard his footsteps go down the stairs, rousing strange echoes in the great empty building. I called myself all the fools I could think of for having anything to do with Shenwick and his confounded experiments, and settled down to my dreary watch.

Sure enough, the horrid thing woke up, and commenced to cry again. Not being a family man, I had not the remotest idea how infants were to be soothed and beguiled to rest and silence. I had an inane notion that you said, "Goo, goo," or "Cluck, cluck," to them, and snapped your fingers and made faces at them. I tried all these in succession, but the more I goo goo-ed and cluck cluck-ed and made faces, each one more hideous than the last, the more that thing cried and sobbed.

At last, when daylight came, there was a loud knocking at the outer door. I went and opened it, and there stood the caretaker and his wife, the last much excited.

"Where's Mr. Shenrock?" she demanded. "What's he doing of with a baby in the room, and ill-treating it, too?"

"There's no baby," I said; "it's a sick man."

"No baby, when I can hear it crying its dear little heart out! You've been smacking and beating of it." She pushed past me and went to the bedroom, saying, "Hush now, my pet; mother will be here directly."

She got as far as the door; then, at the sight of the black-muzzled ruffian sitting up in bed bellowing, she fell down in kicking hysterics. Her husband went to her assistance, but he, too, was struck speechless, with his mouth wide open. In the midst of it, Shenwick came back with a feeding-bottle, patent food, and some milk, having been lucky enough to stick up an early milk-cart. We recovered the woman and Shenwick told her that the patient had just had brain fever, and now imagine himself a baby, and the doctor said he was to be humoured. The woman was only too glad to get away. She had had what she termed a turn, and was not desirous of stopping any longer near this unnatural infant.

It was horribly grotesque to see the man-baby seize hold of the nozzle of the feeding bottle and suck its contents down. When it was satisfied, peace reigned, and the thing slept.

"Shenwick," I said, "you see what comes of interfering with Nature's laws. You will now have to adopt and rear that object in the next room. You were thinking of getting married, I know; but will your wife consent to your bringing home a baby 50 years old! No, she will not—you can consider that settled."

Shenwick groaned, "You needn't rub it in so," he answered.

"Perhaps not, for that little innocent darling asleep in the next room will be a constant reminder."

"Can't you give me some advice on the subject? Although you cannot deny the success of the experiment; yet between ourselves it is of no avail for any purpose. I thought and hoped that the spirit would come back charged with knowledge of the great hereafter. As it has unfortunately turned out, a baby has come back who will grow up with as little knowledge of the past as any other baby does." A long hungry wail came from the other room, emphasizing his statement, and proclaiming that the infant desired further nourishment. Shenwick went and filled the bottle up again.

"There's one chance you have," I said, when he came back. "This aged baby will, most likely, have to go through all the many ills that babies have to endure. I should take care that he died of croup, or scarlet fever, or whooping cough or something or other of that sort."

"What do you mean by 'taking care?'" said Shenwick, looking aghast.

"Nothing at all but what anyone but a fool would understand. I mean, take care of him if he is ill. Now, goodbye, I'm tired." I went home for a bath and breakfast, fully determined to have no more to do with Shenwick, and his dark experiments.

A fortnight afterwards, he came to the office. "I have got rid of him," he said, dropping on to the chair, as though wearied out.

"Buried him?" I asked.

"Oh, no! I called to the doctor who certified his death, and I told him that he had revived, but had come imbecile, imagining that he was an infant. So, after studying the case for some days, he called in another doctor, and he has been removed to an asylum."

"Do you pay for him?"

"Yes, a small sum weekly."

"Well, he will be a pensioner on you all your life, for, according to you, he has another span of years to live. Have you told Miss Colthrope about it?"

"Heavens! no; what would be the good?"

"Best to be open in these matters, however, I won't tell anyone; provided you swear never to have anything to do with this foolery any more."

"That I'll readily do," he said, and he did.

Shenwick married, and years passed, and he had a growing family, when he received a communication from the asylum, stating that the patient had improved so much that they thought he ought to be removed. The fact being that he had grown up into a boy and became more sensible.

Shenwick came to me in despair. "Just fancy, he has the soul of a boy, reared amongst lunatics in an asylum. Of course, he has not been taught anything; what on earth shall I do with him? Will you come out with me and see him? His appearance may suggest something."

I went out with him; ten years had passed since the fatal night of the experiment, and the body containing the boy's soul was that of an old man of sixty-six, looking older on account of the exposure and hardships the body had suffered. It was a regular puzzle. It was evident that he could not take the patient home. And it was pitiful, too. The soul, or spirit, whatever you like to call it, was full of life and vigor, which the palsied, doddering old body could not second. I could think of nothing but a benevolent asylum, and Shenwick agreed to it. The subject never reached it, however. There was a railway accident, and he was badly injured. We went to see him at the hospital. He was unconscious at the time, but death was very near, and he came to his senses just before we left. He recognised Shenwick, and growled out in the husky voice of old, "Hang you, are you never going to fetch that adjective beer?" Then he expired.

Shenwick told me that the last words he uttered at the period of his first death was an order to him, in flowery language, to go and get some beer.

"LET'S go on to the next water," said Dick impatiently.

"Why, it's seven miles and one of our horses is quite lame. No, this place is good enough for me," I returned.

Dick grumbled; but as there was reason on my side he had to give in, and we were soon unsaddled. Usually a very even-tempered fellow my companion seemed strangely put out about something. I did not take much notice—men often get "cranky" in the bush. He smoked long after our blankets were down, and then I dropped off to sleep and left him staring moodily into the fire.

"I was only a boy!"

I awoke with the words ringing in my ears. The moon had risen, but it was a late moon, and seemed only to make the dark shadows darker, and add to the general loneliness around us.

Dick was standing near the dead fire with his hand stretched out as though keeping something at bay. The sickly light of the dying moon did not reveal his face, but his whole attitude expressed supreme horror.

"What on earth is it?" I asked, getting up with a thumping heart.

He laughed strangely and said, "Listen! Can't you hear them?"

I listened. Some curlews were wailing dismally, and that was all; as I told him, curlews always begin to ring out when the moon rises.

"No, no!" he said, "not that; listen again." I did so. Now, whether it was mere fancy stimulated by my companion's strange manner and my sudden waking, I don't know, but it seemed that I distinctly heard a deep-toned bullock-bell toll slowly and monotonously, as when a belled bullock licks himself.

"Pah!" I said, "it's a lost worker."

"Is it?" he answered with a repetition of his queer laugh. "Go to sleep again, old man, it's nothing to do with you."

The bell, if it was a bell, had ceased, and as I still felt drowsy, I drew my blankets over my shoulders and soon dozed off. When I awoke again it was broad daylight.

Dick was very silent all that day (we were on our way back to the station after delivering some fat cattle at L——).

"Do you believe in warnings?" he asked, when we were camped again that night.

"Presentiments?"

"Yes, that's it. Because I've got one, I shan't see this trip out."

"O, bosh," I naturally replied.

"It was at that last camp I killed my young brother."

I thought Dick had gone mad, for he was one of the best natured of men, but he proceeded, as if he had to tell his story:

"I was only sixteen, and he was a little chap of twelve, but quite different from the rest of us. Very willing and sweet-tempered, but shy, and read every book he could get hold of. Well, at that time dad was doing a bit of carrying, and as he was laid up with rheumatism he sent me on a trip with the team, for I was a dandy bull-puncher even then. He told me to take Ben along and try and make a man of him. You know what cruel brutes boys are. I soon found out that Ben was frightened of going away from the camp in the dark and made up my mind to cure him, and so bullied and chivvied him that the poor little beggar became as nervous as a girl.

"Now, there's a yarn hanging to that place where we camped last night—something as to murder done by the blacks in the old times. Ben knew every story there was about the country and could tell them well, too. Of course, he had heard this tale. Now the place was haunted by the ghost of a woman who was always searching for her child who had been killed by the natives.

"I made up my mind to cure Ben once and for all. In the middle of the night I woke him and told him that we wanted to start early, so he must go and bring the bullocks up close to the camp. 'There they are,' I said, 'you can hear the bell.'

"The poor little cove looked at me with great big eyes and shivered, for the bullock just then began to lick himself and his bell tolled out like a clock—one, two, three, up to twelve, and stopped. He begged and prayed me to wait until daylight, but I hunted him off with the bullock-whip and followed him up for a bit to make sure he went.

"It was all quiet for a while, but just about the time he would have reached them I heard that bell again toll out solemnly. Then came such a shriek! I heard it distinctly, though he must have been some way off. I tell you I did feel sorry and ran as hard as I could shouting to him. Half-way I met the bullocks coming up to the camp like mad, but the bell was not amongst them. I had great trouble in finding Ben, for he was on the grass in a dead faint, and the moonlight was not strong. I carried him up to camp and he was an awful sight. His arm was stretched out quite stiff, as if to keep something off, and the poor boy's face was all drawn up with fright and his eyes wide open and staring.

"It was a long time before I brought him round, and when I did he was quite silly, and he never got right again, but died soon afterwards."

Dick was silent and so was I.

"Did you find the bullock-bell?" I asked at last.

"No, and I should like to know who rang that bell—and who rang it last night?" he asked.

"You heard it, too! The yarn about the niggers goes," he went on after another pause, "that they sneaked up to the hut ringing a bullock-bell that they had found so that if the people heard any noise they would fancy it was some stray workers."

DICK did not see the end of that trip. We stopped next night

at a wayside pub, and he drowned his remorse in rum. Worse still,

he fell in maudlin love with a girl there, and Peter, the

bush-missionary, turning up—he got married.

She is a perfect devil, and when last I saw Dick he was thin as a rake. Better for him had the presentiment been fulfilled in the orthodox way.

PONTINIAK, at the mouth of the Kapoeas River, is not a place much visited by Europeans, but one can obtain an exceptional experience there.

Pontianak is the headquarters of the Dutch in Borneo, and the Resident-General has a small joke of his own, which he plays off on the unsuspecting new-chum. As is customary in those torrid settlements, business is generally transacted during the comparatively cool hours immediately succeeding daylight. As you discuss it with the courteous old Resident, he inveigles you into a stroll up and down the verandah, and after a little of this exercise, he informs you that the equatorial line passes right through the centre of his bungalow, and that during the morning walk you have crossed and re-crossed the equator several times.

I have other cause to remember Pontianak. It was my starting-point on an expedition destined to be a very memorable one. I had long contemplated a trip into the interior of Borneo, allured partly by the reports of the half-worked diamond mines, and partly by natural curiosity to see a place so little known. I had accidentally met with a young travelling Englishman, an enthusiastic sportsman, who eagerly jumped at the notion, and the result was that we soon found ourselves at Pontianak, where, after the necessary official permission had been obtained, we made our arrangements for departure.

Travelling there is far more luxurious than in the Australian backblocks. Our destination was the Sintang district, and our highway the river Kapoeas. A large roofed-in native boat, known as a gobang, a native crew under a mandor, or headman, and a good outfit of stores were obtained, and we started for the land of the Dyaks.

For days our journey was most auspicious. The dense jungle on either hand afforded a good supply of game for my sporting companion, and the native tribes we met were friendly and interesting.

As time went on we found ourselves amongst Dyaks, permission to pass through whose country cost some diplomacy, but patience and a friendly demeanour overcame all objections, and we soon got well into the mountainous districts on the upper reaches of the river. As yet I had not met the object of my search—the abandoned diamond mines, legends of which were often repeated by the coastal Malays. Once or twice I was shown places where gold-mining on a most primitive fashion had undoubtedly been pursued in some long-forgotten age. Circular holes had been sunk in three places in the form of a triangle, and drives had then been made from one to another, but by whom it had been done the Dyaks could not tell. Certainly not by their forefathers. Some told me that it was the work of slaves long ago, when the sultans from India had swept down on the archipelago and enthroned themselves in Java and Sumatra, thence enforcing tribute over Borneo, Celebes, and the smaller islands.

No ruins or inscriptions were to be found indicating that the country had ever been permanently settled by the men of that time. Sometimes I heard mysterious reports of a wild race whose descent was more ancient than that of the Dyaks: they were known as the Orangpooenan, or forest men, and were marked with a white spot in the middle of the forehead, an indication, at any rate, of their Hindu origin.

One afternoon about four o'clock the mandor came to me and pointed to a rope of twisted rattan stretched across the river—a sign that we were to go no further. Some Dyaks were assembled on the bank, and we went ashore to parley with them.

They were apparently as friendly as usual, and accepted small presents of tobacco, but declined to give us any reason for refusing the required permission to proceed. We visited the village and partook of fruit there, and after dark returned to our boat. Morton was very hurt at our sudden detention, and wished to go on in spite of the natives. I pointed out to him the folly of such a course, and he consented to take things quietly and wait for a day or two. During those two days I made every effort to conciliate our neighbours, and with perfect success excepting in the one direction. We were not to go up the river. I could obtain no reason for this refusal, and concluded that we must perforce return.

My enquiries as to the ancient gold and diamond mines seemed to amuse the old men mightily. One of them told me that I had seen the Kambing-Mas. This is a golden sheep which appears to certain doomed men. So infatuated does the victim become at sight of it, that he follows it on through jungles and mountains day after day until he dies of fatigue.

Of legends and traditions I got my fill, but permission to go ahead was not to be had. My old friend who told me of the Kambing-Mas asked me if I desired to try for the great diamond which was supposed to be in a lake at the head of a river. This star-like gem, described as of enormous size and unspeakable lustre, can be plainly seen at the bottom, but woe to the rash man who dives down after it! The infuriated spirit-guardians seize and strangle him, and his dead body floats on the surface as a warning to others.

"Perhaps," went on my loquacious host, "you would go to the land of the Mashantoo, the spirit-gold?" This district, rich in the precious metal, was cursed by a sultan of old, on account of the death of his son, and although you may go there and fill your pockets with gold-dust and nuggets, they all turn to sand and pebbles when you cross the boundary on your return.

Meanwhile Morton chafed greatly at our delay, and I had to exercise much tact to pacify him. The third evening I saw him in close talk with the mandor; he then left the boat and went to the village, returning about dark with the information that we now had permission to proceed.

It seemed strange to me that I had heard nothing about it, but at the time I had no suspicions. It was a bright moonlight night. Taking the mandor's kris, Morton went ashore and severed the rattan rope where it was tied round the butt of a tree. The men took their places and the boat was once more under way.

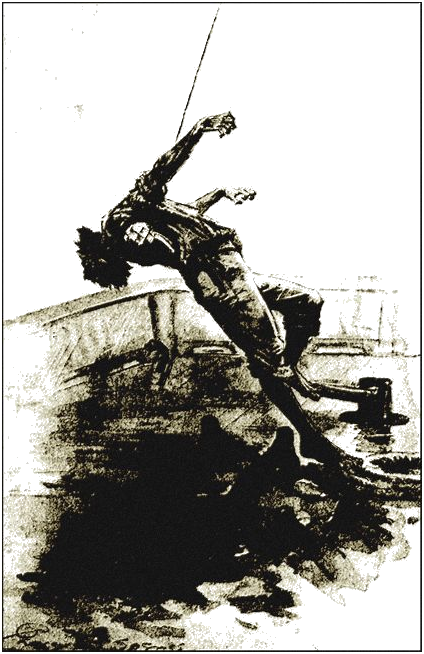

I dropped off to sleep about ten o'clock. I awoke amidst the crash of boughs and branches, bringing ruin and destruction on us and our craft. Although half-stunned, I managed to struggle from beneath the crushed-in roof, and, as the boat sank, struck out feebly for the shore, which I had no sooner reached than I fainted.

What had happened to us was the result of Morton's rashness. Poor fellow, he paid for it with his life. The villagers had not given him permission to go on, but he had bribed the mandor to do so nevertheless. Along the bank of the river the Dyaks had selected certain leaning trees under which we would pass. These had been cut through to breaking point, and temporarily secured from falling outright by twisted rattans. As we passed, these guys were cut, and we were swamped by the falling trees. Morton was killed instantly, but I strangely escaped, and most of the crew were more or less hurt. All this I learned afterwards.

When I came to my senses I was lying by a fire in a small clearing in the jungle, with two or three Dyaks sleeping around. One man was awake, apparently watching. When he saw me looking about he came over to me and brought me a drink. He was very light-coloured, dressed in the ordinary chawat or apron with a jacket, called a "bagu," on his body. He smiled pleasantly, and, addressing me in the native dialect, said, "Saki (a name they had given me at the village), you were ill advised to seek the Tampat-Mas (gold-mine) here. Why did you not watch the flight of the fish-hawk first?" I asked after Morton, and he told me of his death.

I was well treated, and the fate of Morton, whom they knew to be guilty of the offence, had apparently atoned for our trespass.

On the second day I was much recovered, and Abiasi, the Dyak who had just spoken to me, was sitting by my side showing me how to use the blow-pipe, when a strange old man came from the jungle and advanced in the clearing.

He was tall, white-haired and white-bearded, and on his forehead was a round mark made with a white pigment of some sort. Abiasi rose and said something to him of which I could only catch the word "Saghie," another name for the forest men. Presently the old man, who had only a ragged chawat on, came over and regarded me earnestly, then he and Abiasi renewed their conversation.

"Saki," said the latter at last, addressing me directly, "if you still wish to see the Tampat-Mas where the Mas-Hantoo is, this old saghie will take you there." He then further told me that the old saghie, or Orangpooenan, lived in the mountains where there were many old mines, but it was all spirit-gold, that turned into sand and gravel after it was taken away. The saghie thought that the presence of a white man might break the charm. I eagerly agreed to go, and Abiasi gave me many instructions as to my return, lent me a parang, or heavy knife, and bade me farewell.

It was evening when we started, and the old man led me through the jungle by a well-beaten path. Although the moon was bright, the shadows were dense where it did not penetrate, and I confess to having felt very nervous as we pushed on in silence, starting at intervals some sleeping bird or a troop of monkeys.

Presently we came to a small opening and halted in front of a low-thatched hut. In answer to his call a young woman, evidently just aroused from sleep, came out; she brought some living embers and made a fire. Like the old man, she was very fair in colour, good-looking, with well-shaped limbs, which, as her only attire was the chawat, or apron, were fully displayed. After eating some rice and fruit, I lay down by the fire and slept for the remainder of the night.

I was not sorry to see a fine large fish cooking on the coals for breakfast, as my returning health brought with it a good appetite. When we had finished the meal the old man and the girl, whom I guessed to be his granddaughter, took a large rush-woven basket between them and started along a narrow path leading through the forest, motioning me to follow.

In about two miles we reached an open space, and before us rose the rugged side of a hill. We followed the base of this round for some time until the face of the hill grew steep and precipitous, and I noticed we were amongst some ancient workings.

At the mouth of what seemed a drive in the cliff the old saghie stopped, and they set down the basket. He then spoke rapidly to the girl, whom he called Suara, and she collected dry wood and built a fire, the old man lighting some tinder with a flint and steel. Suara then broke down the branches of a resinous kind of pine common to the hilly country, and with the assistance of my parang dressed them into rude torches. I now understood what these preparations meant, and when we had lit the torches the two picked up the basket and led the way into the tunnel or drive.

As seen by the dim, flaring light, it presented far more finished work than any of the ancient workings I had yet seen. We must have gone at least a hundred yards before the old man stopped, and I then saw that somebody had recently been at work, for there was loose dirt lying about, and some native tools.

The old saghie put down the basket, and motioned to me to come and fill it with the shovel. I did so, and naturally took the opportunity of examining the dirt. I sifted some in my hands, and blew part of the finer dirt away, and am satisfied, even now, that there was a large quantity of coarse gold through it and several specimens, as they are generally called by diggers. Of this I am quite sure, despite what afterwards occurred.

The old saghie was peering over my shoulder while I blew the dust away, and grinned hideously as he saw the gold exposed here and there. I remember wondering at the time what possible ambition could be his for the yellow dross. Perhaps he thought the same of me.

Anyhow, we were both satisfied with our inspection, and I went on filling up the bag until it could hold no more. The old man and the girl picked it up and carried it out of the tunnel. Instead of taking the homeward track as I anticipated, they turned down another one, and in a short time we were beside a small stream which descended from the range. Here there were rude appliances for washing, and I selected, as the most convenient, a shallow baked-clay dish, and commenced washing out a prospect.

Not a speck, not a trace of gold was there. I did not look at my two companions, for it struck me that possibly the dirt at the top of the basket was different from what I had examined in the tunnel. I therefore took another prospect from the very bottom and proceeded to wash it.

It was a strange scene. The narrow path leading down to the small stream, just cutting a thin gap in the dense forest. The shrill chattering and screaming of parrots overhead, and the noises made by the troops of monkeys, which swung from bough to bough, and from one long hanging vine to another. Behind me, as I squatted by the water's edge, the two yellow, semi-nude figures of the old man and the girl, bending over my shoulders in rapt attention.

The dirt was rapidly reduced as I swirled the water round in the dish, and when I tilted it to and fro, there, at either end of the grit and gravel, appeared the yellow sheen of gold. I heard the two behind me heave a sigh of satisfaction as this sight appeared. Surely the spell of the Mashantoo was broken at last?

Suddenly, without a sound of warning, a glistening, flashing object dropped from overhead and struck me and the girl into the water. Blinded and frightened, I staggered to my feet, for the stream was but shallow, and in an instant saw what had happened. A huge boa had dropped from one of the trees above, where it is their custom to hang, watching the paths by which the deer go to water, and snatched its victim from our midst. The old man was crushed against the trunk by three or four folds of the creature, whose tail was still in the branches above, and he was already in the pangs of death.

Suara, who, like myself, had been knocked forward by a blow from a coil of the reptile as it dropped on its prey, was standing near me gazing with horror-stricken eyes on the death-scene. The crunching of the unhappy man's bones was quite audible, but his collapsed body showed that life was over.

The dish had floated on the surface, and was held from going down the stream by a tussock of reeds. Suara picked it up and handed it to me with a look of despair. Instinctively, despite the near presence of the monster, now gloating over its meal. I finished washing the prospect. The spell of the Mas-Hantoo held good. Nothing but gravel and sand was in the earthen dish, which I dashed to pieces on a rock.

Together, Suara and I left the spot and made our way to the hut, which we reached that evening and there rested for the night. Next morning she conducted me through jungle paths to within sight of the village where Abiasi lived.

Here she stopped and pointed in another direction, nor would she accompany me a step towards the village; and so, neither able to say farewell to the other in language both could understand, we parted. Abiasi told me afterwards that more of her people lived in the direction in which she had pointed.

Most of our goods had been recovered, and the crew were now nearly all well. A fresh gobang was provided, and I parted from the Dyak villagers with strangely mixed feelings, although it was with some sense of satisfaction that I saw mile after mile increase the distance between me and the mines of the Mas-Hantoo.

From the mid-1890s to 1902 an appalling drought affected the entire eastern half of Australia. That is the background of this novelette.

THE man was singing blithely as he came slowly along the lonely bridle-track. To look at him, one would have thought that he had not much cause for cheerfulness. He was walking, and leading his horse.

Such a horse! The poor wretch, a mere frame of prominent bones, shambled along after its master with downcast head and drooping ears. As regarded flesh, the man was not much better off than the beast The latter carried an old riding saddle, now used to pack the owner's dilapidated 'swag,' a roll of a weather-worn tent and two ancient blankets. The stirrup leathers had been taken out of the spring bars and passed underneath the flaps, and buckled round the swag.

All around the country was bare, burnt, and dusty—a scene of desolation; but the traveller, old and thin, as he looked, hobbled, stoutly on, singing a love-sick ditty about his lost Nellie, occasionally moistening his throat with a mouthful of water from the canvas bag he carried in one hand. As the sun sank behind the upper boughs of the monotonous forest he was travelling through, more tracks began to join in with the one he was following, and man and horse soon emerged on to the open space surrounding a waterhole, about half full of muddy water.

The ground, around was totally destitute of grass of any description, and the ashes of fires and stumps of trees told that it was an old and well-used camping-place, and not far away the white trail of the road was visible, while deeply indented wheel-tracks led to and fro. Without unstrapping his swag from the saddle, the traveller simply undid the girth and lifted the whole lot—it was light enough—from the back of the old horse.

Selecting a spot at the brink of the water which seemed fairly sound, he led his steed there, and let him drink his fill. Then, with a small billycan that had been strapped on the swag, he carefully washed the old fellow nearly all over. This equine toilet completed, he re-ascended the bank with his tin can full of water, set it down, and tied the old horse to a tree.

'We must go out back directly and hunt up a patch of grass, old man,' he said, affectionately patting the sorry animal on the shoulder; as he did so the crack of a whip and the creaking of wagon wheels gave notice of the approach of a couple of teams.

The solitary traveller just glanced in the direction, then busied himself in making a fire and putting his small tin billy on to boil. The two teams drew up at one of the old camping sites, and the busy work of unharnessing commenced.

One after the other the strong, lusty draught horses were relieved of their trappings, and, after a preliminary roll in the dust and a vigorous shake, they ran down to the water and slaked their thirst. Then they assembled on the bank, and a little gamesome kicking and squealing ensued—veritable horse-play—the while the nosebags were being prepared with their rations of chaff and corn, the more favored ones getting an empty candle-box.

The old horse looked round longingly, as though he recognised the proceedings, and only wished that he would be invited to join in them. His master put a tiny pinch of tea in the now boiling water, and, taking a piece of dry damper out of his swag, he divided it in half. Breaking one portion into small pieces he gave it to the old horse in the hollow of his hand, who gratefully whinnied in return.

Presently one of the teamsters, refreshed with a wash, came striding over. He was a splendid specimen of the first generation of bush-born Australians, a class now almost as extinct as the Dodo.

'Pretty dry, old fellow,' he remarked cheerfully. He was a burly giant, with a hearty smile, rife with good temper. 'Did you come along the road?'

'No,' was the reply; 'I came by the bridle-track from Fairview Vale.'

'Then you can't tell us how the water is in Cameron's Creek?'

The traveller shook his head. The carrier glanced at the old horse.

'Your prad looks as though he wanted his ribs stretched' a bit,' he said, in a good-humored tone, devoid of all offence.

'Yes, he does so. There's been no grass in the paddocks at the Vale for months, nor at the Crater either.'

'Been at work at the sheds? Have they cut out yet?'

The traveller replied in the affirmative to both questions. The carrier picked up a blazing stick from the old man's fire, and proceeded in a slow and deliberate manner to light his pipe. When he had got it in good going order, he remarked, with a scarcely perceptible glance at the meagre fare.

'You'd better come over and tucker with as to-night, and have a pitch?'

The traveller accepted the frank invitation as frankly as it was offered.

'Billy!' roared the teamster, 'bring over one of them there spare nose-bags, and a jolly good feed in it.'

A long, sunburnt lath of a boy, just then employed in cutting up a piece of pumpkin, soon came over, bringing the desired article. Taking it from his hand, the burly teamster himself slipped the bridle over the ancient's head, and suspended the bag in its place. The old boy greeted the change with a rapturous and well-satisfied whinny.

'Many's the good feed you've had in your time,' said the carrier, and he fell back a step, and gazed with pitying admiration, at the wreck of a well-ribbed horse. 'Been a rare good 'un in his day,' he said.

The traveller nodded an eager assent; the ample act of manly kindness to his dumb friend had warmed his heart to the doer of it.

'Game as a bulldog ant still, I'll bet,' went on the other, and he gave the ancient a playful smack and pinch in the flank, which made that noble animal lay back his ears and a fan an ineffectual cow-kick at the world in general.

'Better stroll back with me to our camp, said the friendly giant. 'Billy, here, will be taking the horses out to a patch of dry grass directly, and the old moke can go out with them.'

In those days the hospitality of the bush carrier was proverbial and unbounded; moreover, it was a point of honor with him always to have a plentiful spread. The traveller was soon seated on an empty box enjoying his share of a meal, which, if not quite so fastidiously cooked as a French dinner, was more satisfactory to a hungry man.

Eating over, Big Harry and his mate, a tall, taciturn man from the Hawkesbury, known in contradistinction to Big Harry as Long Tom Bevor, lay back and lazily smoked the boy, had slipped away after his return from taking the horses out to the patch of dry grass, and wailing and discordant sounds began to arise from the hindmost wagon.

'There's that young imp at it again,' grumbled Big Harry. 'Ever since he bought that there concertina at the last township, it's been like a crowd of niggers round the camp, mixed up with a flock of curlews and a pack of dingoes.'

'Is it a new one?' asked the guest.

'Well, Billy has been a grinding at it for the last week, but I suppose he hasn't damaged its bellows yet.'

'I'll give you a tune, if you like,' said the old, man.

'Here,' Billy!' roared Harry in a voice that would have dominated a gale, 'just bring that 'constant screamer' over here; here's a man as understands it.'

Billy came over and handed the instrument of torture to the traveler, who touched a note, and suddenly burst into song.

They were old-fashioned songs, old plantation ditties, once popular, but his voice was still strong and vigorous, and he manipulated what Harry, in his clumsy bush humor, called, the 'constant screamer' with the hand of a master. The two teamsters and the boy listened entranced, and the camp by the bare, muddy waterhole became a haunt of memories to them in the future. When the stranger ceased Big Harry knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and remarked:

'Look here, old man, if you're on the hunt for a job, just come with us as off-sider, and well make it worth your while.'

The traveller laughed, and shook his head. 'Many thanks; but I have a job waiting for me ahead.' He touched a note, and started a well-known marching song, with a rollicking chorus that they all joined in, Big Harry's voice making the tree tops quiver. Soon afterwards the camp was silent, save for the distant rhythmical pulsations of the heavy horse-bells.

THE old traveller plodded along contentedly enough the next morning, though the road was dustier and more disagreeable than the bush track he had been travelling on before. His heart was lighter for the kindly companionship of the night before, and, though the old horse's burden was some pounds heavier, that gallant animal did not murmur at it, for he had two unexpected and satisfactory feeds to work upon.

With characteristic open handedness the carriers had insisted upon the old man replenishing his ration bags before leaving. There was no pretence at charity in this, no humiliation in accepting it; it was just the 'give and take' of the bush of those days, when unions had not stirred up the strife of classes, and the lazy, blatant, loud-voiced political agitator, who lived on the game, was unknown. The youth of the country took to bush life of their own accord, and did not, as now, prefer the scanty earnings and cheap pleasures of an overcrowded city to a running fire of stockwhips and a fiery run of hoofs.

Along the dusty road, through the grassless country, the old man and old horse kept sturdily and steadily on their way for many weary days. Then the country through which their steps led showed signs of closer settlement, and the road was fenced on both sides, and the ancient picked up a precarious living on township commons and travelling stock reserves.

At length a day came when man and beast seemed to carry themselves in a jauntier fashion. Early in the morning they left the main road, and took a smaller and little used one leading through a gate towards a range about six or seven miles distant. Once more taking a bridle track that branched from this road, they followed it through another gate, until it crossed a little running creek coming down from the range.

Biped and quadruped had a grateful drink, the latter giving a satisfied sigh, as if to say, 'Ah! this is the right tap at last.'

On the bank of the creek was a good, substantial three-railed fence, enclosing a little patch of grazing land, and beyond could be seen the foliage of fruit trees, surrounding a dwelling. Either this little spot had been favored with later rain or the drainage from the range at the back kept the ground moister, for the effects of the long-continued drought were not nearly so apparent as on the country left behind.

Opening the gate, the man took the path leading to the house, the pair walking briskly on, as though the late arduous journey had been a joke. The 'ancient,' indeed, put on all the swagger of a landowner sauntering over his own property. As they neared the homestead a bright-eyed girl of 16 came dancing down the track to meet them. She hugged the old man round the neck, addressing him as 'Dad,' in endearing tones of welcome. Then she turned her attention to patting and fondling the ancient one, who appeared highly gratified.

As the three approached the house, the girl with her arm passed through her father's, it was seen to be a neatly kept little cottage, with a ruder, rougher building at the back of it; a well-furnished garden surrounded the whole, and the little permanent mountain rivulet could be heard gurgling past. Two or three cows and calves and a few sheep were grazing in the small paddock they had passed through.

A hard, but kindly-featured woman of more than middle-age greeted him respectfully as 'Mr. Grainger,' and a tough, wiry-looking old fellow, who was just finishing his mid-day meal, rose up and did the same. Then he went out to look after the horse, but the girl had anticipated him; she had already unpacked and unsaddled the ancient one, and was leading him off to the stable, and laughingly told the man to go back.

'Everything all well?' asked Grainger, sitting down on a bench.

'All well thank the Lord!' replied the woman; 'but I hear they're suffering terribly for the want of rain hereabouts. Rotta-rotta has lost ten thousand sheep already, so Jock says.'

'Ay,' said Jock, who just then entered. 'Ten thousand, and more to follow. They were dying in the shed,' he added, with a sort of chuckle, as though, for some reason, the intelligence was of a satisfactory nature.

'You ought to take shame of yourself, Jock,' said the woman, 'to rejoice over the misfortunes of others.'

Jock only rubbed his hands.

'How's Carlingford getting on?' asked Grainger.

'There's a lad with sense,' cried Jock. 'Sold a lot of store sheep and cattle, sent away all the fats he could and moved a big lot of sheep to some country he's taken up out west. He'll get through right enough; but the others, with their greed, overstocked their paddocks, so that before the drought had fairly commenced, you could have flogged a flea through them.'

'Well, you change your things, Mr. Grainger,' asked the woman, who did not appear to relish her husband's rejoicing over a fallen enemy. 'The missy has put them out for you, and Jock will take a tub of water in the room.'

'Now, Dad,' said the girl, flourishing a comb and a large pair of scissors, 'come round to the back and be trimmed first.'

Grainger rose, and went round to the back of the ramshackle old building, and the cutting and clipping was finished amid much chatter and gossip. When it was over he retired to a room, and after some time reappeared, looking about fifteen years younger. He wore town clothes of good fit and make, his linen was exquisitely got up, and his boots and hat matched the rest of his things. With his beard trimmed to a point and his hair cut short, he looked the picture of a thorough gentleman, well born and educated.

Big Harry and his mate would have thought they were dreaming dreams or seeing visions had they seen him. The transformation, however, was not noticed by the others, to whom it was seemingly a matter of course.

The girl had changed the common dress she had been wearing and removed her sun bonnet. With her father she crossed to the cottage, and together they stepped onto the verandah and entered a passage which divided the cottage in half. The girl opened one of the doors, and they went into a room comfortably, almost luxuriously furnished.

A woman was reclining on a lounge, an invalid evidently, and something more. The eyes she turned towards her husband wore a vacant expression, and as the door opened she could have been heard talking softly to herself. Grainger advanced, embraced her kindly, and sat down by her.

'Have you had a pleasant holiday, Norman?'

'Oh, extremely so,' he said. 'Will you be able to come out to lunch? We will chat about it then.'

'I think I will try. Was Miss Raymond down there? Her girls must be quite young women, now.'

Grainger answered gravely that he had seen them, and that they were quite grown up, which, as they were the daughters of a girlhood friend of Mrs. Grainger, and three middle-age old maids by this time, he could say with safety. After many more questions in the same strain, the girl, who had been listening with a perfectly serious face to this farce, left the room, and presently returned to tell them that luncheon was ready.

Mrs. Grainger arose, and, with her husband's assistance, went into the next room, where her daughter had a chair prepared for her. The meal was good, and well laid cut with glass, linen, and flowers. The conversation still continued in the strain adapted to the hallucination the poor woman labored under. After she had retired, and resumed her old position on the couch in her own room, Grainger followed by his daughter, went into another room, barely furnished with an old table and two ancient chairs.

'Well, Dad, what luck?' asked the girl.

Grainger smiled. 'I got work at three sheds altogether, but I had to go out back a long, long way, and the country is in a terrible state.'

'So I should think, Dad, by the appearance of you and Chevalier.'

Grainger produced three cheques of extremely modest dimensions, but the girl did not look disappointed at the amounts.

'That will carry us on nicely,' she said.

A knock at the door brought in Jock, and the girl perched herself on the table, and helped, in the conversation that followed on the doings on the little selection dining the owner's absence.

Grainger had been a wealthy man. He had once owned the principal share in the large station of Rotta-rotta. Bad season after bad season brought him down, mortgage followed, a swindling, absconding partner completed the ruin, and then the firm who held the mortgage stepped in and took everything. During the season of prosperity he had, on the passing of the Act, selected the small area of ground on which he now lived, and settled it on his wife, in whose name he had taken it up; and built the cottage, planted the fruit trees, fenced and otherwise improved it.

This was all he had left, and this did not hold out much hope of a livelihood to a man well past the prime of life. But he had worse to put up with. His wife was stricken down with paralysis. She recovered partly, but her intellect was clouded. She still imagined that she was Mrs. Grainger, of Rotta-rotta station, and the doctor assured Grainger that if her changed circumstances were forced upon her, an attack of acute mania, might take the place of the harmless hallucination she labored under. How was it to be kept from her? The selection had originally been taken up as a sort of summer retreat; it was an exceptionally fertile little spot, with a perennial spring running through it and had been christened the Oasis. The mortgagees had allowed him much of his private property, including some furniture, etc., and his favorite horse, Chevalier. The furniture sufficed to furnish two rooms of the cottage in a manner Mrs. Grainger had been used to, and there she lived in ignorance of their fallen fortunes.

Jock and his wife, two old servants, insisted on sharing their master's adversity, and Jock looked after the little property, Grainger's absence in search of work being ascribed to visits of business and pleasure.

For this was the masquerade of the good clothes kept up; for this was all the money gained by toilsome journeys, by the severest economy, and by every shift and contrivance used; and amongst such surroundings had Winifred Grainger grown up to the verge of womanhood. Her father, a highly-educated man, had taught her whenever he was at home, and from Mrs. Jock she had learned practical housewifery; perhaps, after all, it was not bad training for the girl to grow up in such an atmosphere of unselfishness and self-denial.

POOR Grainger, he did everything for a living. It was not possible for him, on account of his wife, to accept some subordinate situation either in town or country, so he roamed the land for work. He had walked his painful way to the outside stations at shearing time; he had tuned pianos, and played on them for township balls, for he was an excellent amateur musician. He had even joined a strolling company of Ethiopian serenaders, and rattled the bones as corner man; and by one means and another kept the Oasis afloat, so to say.

But even this was envied him. The firm, who had foreclosed sold the station to a self-made man of shady antecedents. This individual coveted the Oasis after the Scriptural fashion, and when Grainger refused all offers to sell it, became the fly in his honey pot.

A series petty persecutions were commenced. Blacklock, the new man, denied Grainger right of way through one of his paddocks to the main road, knowing well that, although, he was quite in the wrong, Grainger could not afford to follow him through the courts in appeal after appeal.

Blacklock, however, roused up a friend of much influence on behalf of Grainger. Tom Rossiter of Carlingford, who had succeeded to the station on the untimely death of his father, had from boyhood always, as he expressed it, 'liked old Grainger,' and he played a trump card on his behalf, and also one which promised to be a paying one in time. He selected land on either side of the Oasis, and insisted on the right of way to and from his selections, which would accord it also to Grainger. When Blacklock found that, instead of having a broken old man to oppose him, he had a young and very energetic one, with a big balance at the bank, and a determination to fight him tooth and nail to the very door of the Privy Council if necessary, he cried craven, and the matter dropped.

Rossiter was Winnie's especial favorite and hero. Had he not given her a pony when she was a little girl, and when that diminutive steed met with an accident which unfortunately necessitated his being shot, had not another one mysteriously taken its place in the paddock; one night? Moreover, were not Rossiter's mother and two sisters always glad for her to come over to Carlingford and stay with them?

About two days after Grainger's return Rossiter, who had heard of it, came over to see him. He was, of course, well acquainted with all the surrounding circumstances of Grainger's ruin, and, like the good-natured fellow that he was, visited Mrs. Grainger, presented his mother's and sisters' compliments and best wishes, and humored the good lady to the top of her bent; then he adjourned with Grainger to the den of an office.

'I've got something to tell you,' said Rossiter. 'It came to me through a man who, if he gets drunk, will retail the information everywhere, and that is what I want to avoid. For a time, at any rate. You know Jim Dee, the fencer who has taken the contract for fencing that selection I took?'

Grainger nodded.

'He is am old miner, you know; has been knocking about all over the world. In sinking a post hole on the south boundary, only a few panels from where it joins yours, he came upon this,' and Rossiter unfolded a paper parcel, and put some dark, rugged lumps of stone on the table. Grainger examined it curiously.

'Silver ore,' he said at last.

'Exactly,' returned Rossiter. 'The lode runs through the corner of my selection, and, by its direction, goes right across the middle of yours, and into my western selection. Now, I am going to send this down for assay, and apply for a mineral lease to the south. Meantime the difficulty is in keeping Dee's mouth shut; since he starts drinking it's all over the place.'

'Does he know that it is silver?'

'No; I think not. He may be foxing, but he pretends that he thinks that it may be some sort of mineral.'

'Of course, we'll give him a show if it turns but all right?'

'Of course we will, and it could be worked at a small cost. We have a permanent water supply, here, and the range is covered with firewood. If the assay turns out well we must select all we can of the range.'

Grainger looked with admiration at his young companion, and admired his business foresight; but Rossiter was still thinking.

'Anyhow, we must secure the source of the spring,' he went on, 'and secure ourselves from that being diverted. I wonder Blacklock has not done that before to annoy you. Anyway, I'll make sure of it by putting in an application to-morrow. By Jove, I'll put it in Winn's name. How old is she?'

'Seventeen in about three months.'

'That's good enough then. We'll make a rich woman of her.'

Grainger smiled somewhat sadly. He had not the sanguine feelings of his young friend.

'What do you say to going out this afternoon, and getting the lay of the place? Can you give me a shakedown, and I'll go on to the township tomorrow.'

'Of course, we can. As soon as I have written a couple of letters, we'll go.'

In about half an hour the two men, with, of course, the attendant Winnifred, were strolling up the gully, along the bed of which the little stream rippled. Even now, during the excessive dry weather, the gully was cool and shady; the moisture oozing mostly from one spot about a mile from the boundary fence of the selections; above, all was much drier, and it was evident that they had reached the source. The three stood there silent for some time.

What did they think of? Grainger, the man of the past, may have seen the picture of a quiet old age amongst congenial pursuits, free from the harassing toil that was killing him. Rossiter, the man of the present, heard the busy whirr of machinery, and saw the poppet heads of the shafts, and the rising and descending cages. And Winnie, on the threshold of girldom, what did she see, but the glorious dreams of the unknown world beyond the quiet bounds of the Oasis.

Rossiter first broke the silence.

'We'll run the boundaries while we are here. You stop here, old man. Winn, you come and put in corner pegs, and I'll pace it.

Rossiter started with a measured stride, and Winn followed dutifully behind. Their forms were soon hid in the forest slope, and Grainger lit his pipe for a quiet smoke.

The tread of a horse aroused him from a pleasant daydream.

'Good day, Mr. Grainger,' said a voice, as the rider approached and pulled up alongside of him. Grainger looked up, and saw his enemy, Blacklock. A rubicund man, nearly of his own age, with a fringe of white whisker like a baboon's ruff.

Grainger nodded.

Looking over your little property, eh?' went on the other, in a satirical, manner.

'I scarcely know whether that is any business of yours or not,' returned Grainger. 'I imagined that we were no longer on speaking terms, but you seem to have forgotten the fact.'

Blacklock flushed, and tapped his boot with the crop which, in his role as squatter, he now carried.

'I didn't come here to bandy words,' he said. 'To-morrow I'm going to mark out a selection here, and I just wanted, to tell you to keep off of here an future.'

'Indeed! Extremely kind,' returned Grainger, keeping his temper. 'It is Crown land at any rate at present, so I shall finish my pipe at my leisure.'

At this minute there were hasty footsteps, and Winnie, appeared on the scene, and stood by her father's side. Winnie had obediently followed Rossiter to the first corner, and remained there at his bidding, while he marched onward, at right angles, counting his strides as he went. He soon disappeared in a dump of thicker timber, and Winn turned round and looked towards the place where they had left her father standing. She saw the horse and rider, and with the instinct of a bush-bred girl, recognised them, and, without a thought but that of a true woman's in standing by the side of those she loved, hastened back to take after place with her father.

Blacklock looked at the girl and ironically lifted his hat a little; and said, 'Good evening, miss Grainger. I was just warning your father against trespassing on this land in future, and I am afraid that I have to give you the same caution.'

'I was not aware that you knew my daughter,' fired up Grainger. 'Excepting, perhaps, by sight. Kindly don't presume on that slight knowledge, or it will be the worse for you.'

Blacklock glared in astonishment at him. Winnie tapped her foot impatiently. For the first time in her life she was cross with Rossiter. Why had he not come back? He must have missed her, and could see where she was. In truth, Rossiter had done both, and was then quietly approaching from an unexpected angle, and none of the group saw him.

'Do you know who you are speaking to?' exclaimed Blacklock, in sudden anger. 'Don't you know I could buy and sell you over and over again?'

'So far as ill-gotten money is concerned, you might,' returned Grainger; 'But, old as I am, I'll teach you a lesson, if you like to teach you a lesson, if you'll get off that horse.'

'The devil, you will! You think that because that young fool Rossiter—'

'Here he is,' said a voice, the owner of which was almost close beside him. 'What have you got to say about him?'

Mr. Blacklock, who had been sitting half-turned in his saddle, started round. Winnie gave a slight hysterical laugh.

'Oh! It's you, Rossiter, is it?' said Blacklock.

'Mr. Rossiter, if you please. We are not quite on terms of familiarity, specially after just calling me a young fool.'

'Look here, sir,' said Blacklock, mustering up a bluster, 'I wish my sons were here to hear you.'

'I wish they were,' retorted Rossiter hotly. 'I'd make a football of one of them up and down this gully.'

'You might find that they could play football better than you,' said Blacklock savagely.

'They haven't got that reputation, at any rate. When Melbourne or Sydney is too hot for them they come up here and masquerade as bushmen. Bushmen, indeed!'

'That'll do, Mr. Rossiter. You will repent those words as long as you live,' and Blacklock, who was intensely, proud of the two cubs he called sons, rode away fuming.

Rossiter laughed.

'What's he been talking about?' he asked.

'A good joke,' returned Grainger. 'He is about to select this place, and warned Winn and myself against trespassing here for the future.'

'The pompous old fool! He has clean given himself away. But Dee is at the bottom of this, I'll be bound. He must have been talking.'

Rossiter thought for a moment, then he went on. 'I'll go in to the township to-night and have the application in the Lands Office the minute it opens. If Blacklock is only going to run the boundaries to-morrow, why, we shall be at least twelve hours ahead of him. What an ass the fellow must be. Come on, Winnie, we'll finish our survey.'

ROSSITER rode in to the township that night, and the next morning the application was duly lodged, and the time recorded. He was riding homeward that afternoon along the dusty road, bounded by the parched and barren paddocks, when he saw two horsemen approaching. He was not long in recognising the Blacklock brothers.

'Too late, too late,' chuckled Rossiter, who guessed that they were on their way to the lands office. They piffled up surlily when they met, the eldest, a pasty-faced young man of three-and-twenty, being nearest to him.

'Morning, Rossiter. What's all this about making footballs of us, eh?'

'Depends upon your behavior, or misbehavior, rather. Your father politely referred to me as a young fool, and expressed a wish that you were present—to take his part. I presume.'

'Well, you began it,' grumbled young Blacklock. 'We might have been all good friends but for your taking old blackamoor Grainger's part.'

'Speak civilly,' said Rossiter, angrily.

'Why, what's in that? Nearly everyone knows that he once blacked his face and sang with some nigger minstrels. I took care to spread the yarn.'

Rossiter's eyes blazed. A touch of the near spur, and his horse shouldered up against the other one. He caught the young whelp by the collar, and shook him soundly.

'Here! Hi! stop it! Pull him off, Reggie,' cried the assaulted one, but Reggie showed no desire to interfere. 'He has worked hard, like an honest, honorable man,' said Rossiter, letting him go; 'and that's something you'll never be.'

'Confound you!' grumbled the other, as he fumbled at his loosened collar. 'You've lost my diamond stud.'

'Ah! oh!' laughed Rossiter. 'A bushman who wears diamond studs!' and he rode off, remarking as he did so, 'Tell your respected parent from me that, if I am a young fool, there's a proverb that he'll learn to know the truth of: 'that there's no fool like an old fool,' and he rode off, leaving the brothers wrangling.

Their mutual recriminations grew so rancorous that when they reached the headquarters of settlement in that district they selected different hotels whereat to pass the night.

Reggie, who had declined to come to his elder brother's assistance, was by far the better of the two. The other had inherited all his father's defects, with a few original vices of his own thrown in. The mother kept herself in the background; she had never risen with the family rise, and report said that her reading and writing were after the traditional manner of Shakespeare's knowledge of Latin and Greek. There were no daughters, and the poor woman lived a solitary, friendless life, regretting the old days of struggling and striving.

Reggie had a budding passion for Bella Rossiter, the younger of the two Rossiter girls, and he thought it politic to keep clear, if possible, of any complications with her brother, whose strong, masterful character he somewhat admired. He was not a bad young fellow at heart, and it was possible that, freed from the influence of his elder brother and away from his unwholesome surroundings, he yet might develop into something worthwhile.

Bella was some eighteen months older than Winnifred, and the girls were great companions. Winnie, indeed, had to thank Mrs. Rossiter and her daughter for all the social training she had received. When her father was away she had necessarily to remain tied to the Oasis and her mother's side; but when her father was at home she was enabled to spend many long, happy days at Carlingford.

Soon after the meeting between Rossiter and the Blacklocks the two girls were roaming over the range on their active ponies. They were both fond of such rambles, Bella especially having an adventurous strain in her blood; as the daughter of on old pioneer should have. The range, in spite of being called by such an imposing name, was of no great height, but it was lonely, rugged, and had the repute of having been once the haunt of a bushranger; in all probability a vulgar horse-stealer whose exploits had grown with the years that had passed since his legendary existence.

Bella's great ambition was to discover the cave said to have been the retreat of this worthy, and the recesses of which popular fancy had credited with concealing much stolen plunder! Bella was in great hopes of discovering this spot. She had found an old, almost worn-out track which apparently led somewhere, but had an awkward knack of running out, and leaving the investigator stranded. She had vainly tried to induce her brother to offer his services in the quest, but Rossiter had, in the first place, doubted the existence of the bushranger; and, in the next, asserted that if ever there had been a bushranger he would not have been such a fool as to use the same track until it was so plainly defined that it would lead anyone to his retreat.

Bella, however, firmly believed in the bushranger, the cave, and the hidden plunder, and was moreover persuaded that the faint pad she had discovered would eventually lead her to success. On this day she was following it with the patience and determination of a black tracker. She had, indeed, got on further than at any other time; walking ahead with her pony's bridle over her arm, Winnie following until they were at last brought up by a flat expanse of rock. Following the direction of the trail she advanced resolutely, Winnie, who had also dismounted, close behind, while the hoof strokes of the ponies rang out metallically.

Bella stopped in the middle and looked around.

'I am quite, quite sure,' said, the confident young leader, 'that I am right. Look, Winn, what a splendid view you have all over the country.'

True, there was a complete panorama spread before them. They stood on the cap of a projecting knob of one of the main spurs, and, as Bella said, it was a perfect look-out from which any body of horsemen coining across the lower country could have been seen approaching from nearly three cardinal points of the compass.

The girls stood and enjoyed the wide view, picking out particular places they knew, when suddenly Winnie's sharp ears caught sounds like advancing footsteps.

'Oh, Bell, there's someone coming —perhaps it's the bushranger!'

'I hope he's nice if it is,' answered the undaunted Bella. 'I'm just dying to meet a bushranger; I've read such a lot about them in English novels.'

The girls listened. Heavy, clumsy footsteps were undoubtedly coming down the slope that abutted on the flat rock behind them. Bell glanced round them, then led the way to a good-sized boulder.

'Boot and saddle,' she said, and stepped on to the stone, and seated herself on her sturdy little steed. Winn was soon mounted, too, and, confident in their game little animals and their own horsewomanship, they waited for the advance of the enemy man.

It was not a formidable figure who finally approached them. A shambling old fellow, roughly dressed in the usual bush rig-out. Truth to tell, he looked somewhat disappointed when he came in full view of them. He came on, however, and made a clumsy salute.

'Good day, young ladies. I thought I heard voices, and being short of tobacco, I thought as there was somebody here as might have some.'

'Do you live here, then?' asked Bell, gazing curiously at this Rip Van Winkle of the range.

'I'm staying up here now on a kind of holiday, having a spell like. There's a good spring back here, and I've pitched, my tent there for a bit. May I ask if you young ladies belong about here?'

'Belonged here all my life,' laughed Bell. 'Ah! Then your name might be—?'

'Rossiter.'

'Surely now. You must be little Bell; she was the freckled one.'

The two girls laughed merrily. Bell was not touchy on the subject of her sun-kisses, nor had she need to be.

'Many's the year's work I did for your father in the old time. Surely you must remember: I am the Hatter?'

'Of course, I've often heard of you, but don't remember you personally. What brings you up here, Dan?'

'Just what I said—a spell. When fences came in, I gave the monkeys best, and went up north to the new diggings. I made a bit of a rise up there, and thought I'd like to have a look at the old place, but there—I couldn't stand the township, so I came up here, where it's quiet and homelike. Always a hatter, you see, Miss Bell.'

'Well, Dan,' said Bell, who, on the strength of former acquaintanceship, although forgotten by her, had at once established herself on terms of intimacy with the old fellow, 'is your camp far from here? We should like to see it.'

'Surely, Miss Bell. But who is the other young lady? She's not a Rossiter?'

'This is my friend, Miss Grainger.'

'Of Rotta-rotta. Must have seen you when you were a baby, I expect; but you've grown since then. Sorry to hear your father lost the old place.'

Winnie bent down, and shook hands with the old hatter, then he led the way across the rock in a different direction to the way he had come.

THE old fellow's camp was on the head of the next gully; there was the tiny spring he had mentioned, which he had cleared out. An old sheep dog was chained to the tent pole, and he rose up and barked indignantly at them—evidently, he, too, was a hatter. Bell slid down from her horse, and went up fearlessly and patted his head, and he fawned upon her in return.

Everything about the place was neat, and methodically tidy. Dam invited his guests to have some tea, and, on their assenting, made the fire up and put the billy on to boil.

'Dan,' said Bella, 'do you remember the story about the bushranger who used to live up here?'

'I remember a yam of some sort about

'And about his cave?'

'Aye! and his cave, where the folks said he had planted a lot of watches and things.'

'Yes, yes,' cried Bell, eagerly. 'Winnie and I have been looking days and days for that cave. I've found an old track that I believe leads to it, Now, I'll tell you what we'll do. I'll show you the track; and while you're up here you can puzzle it out, and when you find it—which, of course, you will—we'll go halves in the plunder.'

Dan laughed. 'Of course, I will help, Miss Bella. On one condition.'

'What's that?'

'That you let me have first pick out of the watches. Specially if there's any ladies' watches among 'em. There's a young woman. I know as I should like to make a present to.'

'Certainly you shall, Dam; although I'm quite shocked at an old hatter like you knowing a young woman.'

The girls had a merry tea, drinking it out of the cleanly-polished pannikins which Dan produced. Then they prepared to return.

'Now, Dan, as my share towards finding the cave,' said Bell, 'I'm going to provision this camp. Tomorrow I'll get my brother Dick to come up with me. You remember my brother Dick?'

The old fellow went off into a hoarse chuckle.

'Remember him! Don't I call to mind one day when I was in at the station, and he mounted a colt, a bit of an outlaw, and the colt shucked him clean over the cap of the stock-yard and he fell right on top of his head. Lord! Your father said when he picked him up, "that boy's head and neck must be made of wrought iron!"'

And Dan laughed again, as though at an exquisite joke.

'Well, Dick will come with me tomorrow. But mind, he's not to know a word of this. He always laughs at me for believing in the bushranger. You come a bit of the way with us, and I'll show you where the track runs out.'

Followed by Dan, the two girls retraced their steps to the other side of the flat rock, then, with a very unconventional handshake they parted, and the two rode home talking gaily over their adventure.

Next morning, Bella and Winnie, followed by Rossiter leading a pack-horse—as he called it, 'doing blackboy'—climbed the range and arrived at the hatter's camp. There was a cordial greeting between him and his father's old servant, whom, of course, he had been old enough to remember well.

The stores were unpacked, and stored away, then Dan beckoned Bell mysteriously on one side.

'I poked about after you'd gone,' he said, 'and again this morning. And I found the continuation of that track. T'aint a wallaby pad, either. Will you come and see it?'