RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

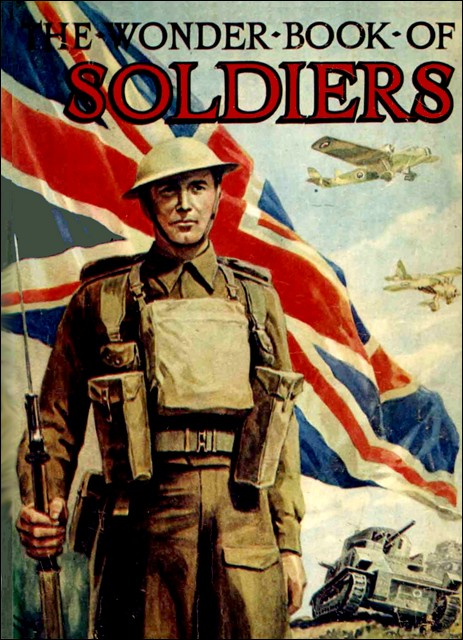

The three short stories in this e-book appeared in two lavishly-illustrated collections of patriotic tales and articles for children published by Ward Lock & Co., London, in 1914: The Wonder Book of Soldiers for Boys and Girls and Our Soldiers and Sailors in War and Peace. The former was revised and republished several times. The dust jacket of the 9th edition and last edition, which appeared in 1940, is shown below.

At least one of the stories — "Sentry No. 1" — was syndicated for publication in various magazines and newspapers. The illustrated version of the story offered here was reproduced from the children's section of The Philadelphia Inquirer for Sunday, November 9, 1924. The two other stories were prepared from donated texts.

The Wonder Book of Soldiers, Ward Lock & Co., 9th edition, 1940

WHEN Ferdie van Wyk was arrested for being found in the barracks of the Larkshire Regiment under suspicious circumstances, he very naturally objected to being marched through the one little street of Simon's Town by a military escort.

Ferdie was neither black nor white, being of that complexion which is described politely as "colored." He had been thrown out of Cronje's army for drunkenness and theft, and he had tasted the dread "sjambok"—that pliant length of rhinoceros hide which the backveldt Boer wields with such skill. He left, vowing vengeance upon his onetime friends, and came to the British Army at Modder River with a cock-and-bull story which secured him a post, first as transport rider, then as guide to the force. Here he was detected in the act of cruelly and unnecessarily flogging a native boy. The boy was a Fingo lad engaged as "voertrekker"—that is to say he walked ahead of an ox-team. leading them, since, as you may know, oxen are not guided by reins, and move so slowly that the "voertrekker" finds no difficulty in keeping ahead of them. For his cruelty, Van Wyk was kicked out of the British Army and carried himself to Commandant Viljoen, who was operating in the Free State. In his malice he volunteered to lead the Boers to an unprotected British post on the railway line between the Orange and the Modder Rivers.

He was so plausible with his stories of rich stores guarded only by a handful of soldiers that the commandant took his command to the attack, only to be repulsed with considerable loss. Van Wyk escaped with his life and wandered about the country, robbing isolated farmhouses and terrifying the women who had been left behind till he found himself at De Aar, in the Cape Colony, where he was suspected of having wrecked a troop train, but escaped again by smuggling himself on a southward-bound mail train.

Van Wyk wandered about the country, robbing isolated farmhouses

He drifted to Simon's Town, filled with hatred for mankind and especially soldier-kind. It mattered little to him whether the soldier were Briton or Boer, whether he wore khaki or the cartridge belt which constituted the sole uniform of the burgher army.

A tall broad-shouldered man with a dark yellow complexion, flat nose and seamed cheeks, his sullen eyes surveyed the pretty little town hatefully. Like many other men who by their own wicked acts have brought punishment upon their heads, he blamed everybody but himself, and he blamed nobody so much as the deputy chief magistrate of Simon's Town, who, eight years before, had sentenced him to a term of imprisonment for atrocious cruelty to a dog.

It was unfortunate for Van Wyk (that was the name he adopted) that his thieving propensities should get the better of him. Thinking that the detachment of soldiers stationed in Simon's Town was engaged in manoeuvring on the hills, he made a furtive visit to the barrack-rooms, and was captured whilst he was pilfering a soldier's kit-bag.

Van Wyk scowled as he was led into the courthouse, for sitting on the bench was the same young magistrate who had sentenced him eight years before.

Mr. Gerald was not so young, but he bad scarcely altered, indeed he looked younger.

"I know your face," he said, when the evidence had been given; "aren't you Ferdie Van Wyk?"

"No," lied the prisoner, sullenly.

"I am satisfied that you are," insisted the magistrate.

"That's right, your worship," said a gaoler.

Van Wyk scowled at the official, and if a look could have killed, assuredly the gaoler would have died on the spot.

"I shall send you to Cape Town for trial," said the magistrate, and there the matter ended.

Outside the courthouse Van Wyk waited under the care of two armed guards, planning methods of escape. He saw a native nurse wheeling a baby up and down in the shade of the magistrate's garden.

"Whose child is that?" he asked in Dutch.

"The magistrate's little girl," was the reply. A malevolent gleam lit the halfbreed's eye as they marched him away to the cells.

He found himself locked up with two choice spirits, men of his own color, also awaiting trial, and both of them apparently foredoomed to long sentences.

"I wish I could take a match and blow this town off the face of the earth," said one bitterly.

"If we could set fire to the magazine," said the other.

Van Wyk, his heart filled with black hate, said nothing, but he thought of the magistrate and he thought of the gaoler.

"I have a plan, brothers," he said after a while. "At what hour does the gaoler come in the evening?"

"At seven."

"Alone?"

"Sometimes," said one of the men, "but he never enters the cell—he puts the food through, this trap," and he indicated a small wicket in the aoor.

"Where does he carry his keys?" asked Van Wyk

"On his belt."

Van Wyk thought. He was a man of tremendous strength, and his long arms, reaching almost to his knees, were more like a monkey's than a man's. He measured his arm against the door and nodded, satisfied.

At night came Crumps, the gaoler, with the evening meal. He came alone, but he felt safe enough with a door of thick oak between himself and his prisoners. He passed the bread and soup which formed the evening meal through the wicket, then as he was on the point of closing the little steel grating Van Wyk called him.

"What do you want?" asked the gaoler testily.

Van Wyk's arm shot through the wicket, and his long sinewy fingers caught the gaoler's throat. The man struggled, but was drawn to the grating, and another hand grasped him and drew him tighter to the door. He struggled madly, tore at the encircling fingers, but the assault was too sudden. He went limp and unconscious.

Van Wyk held him thus, then, gripping him by the collar with one hand, thrust his long arm through the wicket and found the keys hanging by a chain. With a wrench he tore the chain from the belt and let the inanimate figure fall to the ground.

He chose a key and reached bis arm through to its fullest extent... A minute or two later three prisoners tiptoed down the stone corridor to freedom and vengeance.

IT wanted a quarter to one when the sentrv on No. 1 post began his weary perambulation of the beat which extended almost from the seashore to the iittle waterfall in the kloof. Behind the square, squat magazine the hill rose steeply. Above, the sentry heard the whine and the bark of baboons at their play. It was not a cheery post, even in the broad light of the African day, when Simon's Bay, alive with grey-hulled men-of-war brought a sense of companionship: at night No. 1 was the saddest of all posts in the world. So thought Terrence Cane as he shifted his rifle from one shoulder to the other for comfort, and stepped briskly toward the town end of his beat.

There was a level width of road cut out of the hillside. On his left now the ground sloped away steeply, leading down to a brook and a score of disreputable houses which were huddled about the insalubrious streamlet.

He was half-way across the road when he stopped suddenly.

Somewhere close at hand he had heard the whimper of a baby. It came from the left, and he peered down the slope. He saw a movement, ever so slight, on the hillside and brought his loaded rifle down to his hip with a smack. "Halt! who comes here?" he challenged quickly, but there was no reply. He listened. Only the barking on the hill and the musical tinkle of the fall broke the silence of the night.

Then again came the fretful cry and again he saw a movement.

He stepped carefully down the rough slope, his bayonet glittering blue in the moonlight, then with an exclamation stooped and picked up a little bundle that lay at his feet.

It was a little baby apparently only a few months old.

He climbed back to his post, carrying rifle in one hand and the baby in the other.

"Why, you little beggar!" exclaimed Private Cane reproachfully. "What do you mean by being out so late at night?"

It was a white child, beautifully and delicately dressed in night-clothes of the finest texture. How had it come there?

Ten minutes before he had thought he heard voices coming from the direction of the brook, but that was not an ununsual circumstance. One always heard voices on No. 1 post, and before now the guard had marched to the relief of a sentry who had broken down into a nervous wreck from the strain of two hours spent on the magazine guard.

Cane walked slowly back to the magazine sentry-box. It was a warm night, but his overcoat hung there in case of rain, and he carefully wrapped the little one in its folds. She was sleeping as calmly as though she were in her beribboned cradle.

He was bending over the child when he heard a noise behind him. He turned quickly, but not quickly enough.

A billet of wood came down on his defenseless head, and he went down like a log.

"Better kill him and finish it," said Van Wyk

"What's the good," whispered the ruffian with him; "if we blow up the magazine he'll die without trouble—you were mad to leave the child on the hill."

Van Wyk turned with an oath.

"What else could we do?" he asked fiercely. "I didn't know he went so far in his walk—I didn't want to alarm him, and I can't carry a kid in mv arms whilst I'm scaling a magazine wall."

He looked at the senseless soldier at his feet, and the third man spoke.

"Let us take his rifle," he said.

"Time for that later," said Van Wyk gruffly. "Give me the matches and the shavings and help me over the wall."

But first they dragged poor Cane to a sitting position, bound him tightly with a length of cord, and forced a stick gag into his mouth. Whilst they were doing this the baby raised a fretful cry.

"Hurry up!" said Van Wyk; "if the magistrate discovers the kid has gone he'll raise the town—and besides, the sentries are relieved in half ah hour."

The three men made for the wall as the dockyard clock struck one.

"No. 2.—All-l-l's well!"

Van Wyk heard the distant cry from the barrack sentry.

"No. 3. —All-l-l's well!"

Fainter came the answer from the store guard.

He knew that the men in the guard room would be waiting for No. 1 to respond, and if he did not answer a file of the guard would come at the double to discover why.

"Hurry!" he growled.

A small baby girl who wakes from a pleasant nap in the middle of the night and finds herself in the unaccustomed surroundings of a sentry-box swathed in a soldier's great-coat may choose between yelling her indignation or investigating.

Baby Gerald investigated. She crawled from her bed and flopped alarmingly in the road. She saw a huddled man apparently asleep, and since she had seen people asleep before she was not alarmed. More to the point, she saw a very pretty object glittering on the roadway. It was a long rifle with a bayonet at its end, and she started to crawl its length, cooing cheerfully the while.

She started at the butt end and had not gone far when she stopped to investigate some highly-complicated mechanism. She did not know how complicated it was—all she realized was that it was inviting. She grasped at the polished bolt and she touched the magazine, and then her inquiring, saucy eyes saw a little projection of steel beneath tne rifle. She tugged at this, but it wouldn't come away. She turned again.

"Bang!"

Baby Gerald went backward with a terrified yell, and Van Wyk, astride of the wall, dropped quickly to the ground and ran for his life—straight into the arms of the hurrying picket.

He swung aside and darted down the slope, but the corporal of the guard was a crack shot, and Ferdie Van Wyk finished his earthly career on the slopes of Simon's Bay.

Baby Gerald is now a grown young lady, but they call her "Sentry No. 1" to this day.

THERE are regiments in the Army which are proud, and justly so, of certain regimental pets. One corps possesses a ram, another a deer, one a wolf-hound, and one at least claimed a bear that waddled ahead of the regiment. It is somebody's joy to lead the regimental pet with a white leather lead ahead of the band, and it happens in most regiments that that somebody is a drummer.

Now the Wigshire Regiment—its real name I will not give for obvious reasons—had no pet. They wore on their collars the Sphinx of' Egypt: but since no man had ever tamed a Sphinx to walk before a band, and since it must be a Sphinx or nothing with the Wigs—as they were called—the regiment treated the question of animated coats-of-arms with lofty contempt as something too childish to engage its attention.

It was lamentable that the Wigshires found themselves on four consecutive occasions with regiments favoured with divers representatives of the menagerie—lamentable for the reason that there began to grow up in the battalion a most pronounced feeling of dissatisfaction—and in no company was the discontent more strongly expressed than in the 'drums.'

Boy Steevens, a diminutive lad with a freckled face and a snub nose, was unusually bitter.

"There ain't no regiments in the Army, " he said, did this outrageous Boy Steevens, "that ain't got a dog or a goat or a performin' animal walking in front of the band—except us." There was a chorus of gloomy approval.

"You can't have a sp'inx, " protested Boy Carter, his mind running to logic, " 'cos there ain't no sp'inx—at least not a live one, an' the other regiments only have the animals that are on their collar badges."

This was apparently true, but did not help the drums to discover a solution to the difficulty.

"What's the nearest thing to a sp'inx?" demanded Boy Steevens suddenly.

This was a question which none present felt qualified to answer. A sphinx was unlike any representative of the animal world as could be imagined. A terrible problem indeed, and the Wigshires appeared to be doomed to oblivion if they depended for fame on a regimental pet which bore the slightest resemblance to the famed symbol of Egyptian oracle.

Suddenly there was a yell.

Boy Steevens, his eyes blazing with the splendour of his inspiration, had sprung up from the bed-cot upon which he sat. "I know," he cried, "I've got it."

The drums glared at him inquiringly.

"What?" demanded a dozen voices.

"A rabbit!" said Boy Steevens, trembling with excitement, "haven't you ever seen a rabbit—the same shape, the same funny look about its face, and his ears hangin' round his neck like the sp'inx. An' his two paws stuck out just like a sp'inx, an' waggin' his nose up an' down just like, I'll bet, a sp'inx did when he was alive!"

The drums were impressed. Even the most sceptical and cynical had to confess that there was some likeness.

"I'll bet, " said Boy Steevens rapidly, "that a sp'inx is only a skinned rabbit—we'll have a pet, an' I'll lead him."

But the voice of Boy Carter poured cold water on the proposition. "Rabbit ain't anything, " he said, "an' you can't train rabbits to walk in front of a band, because they don't walk—they just lop-lop this way an' that except when they're frightened. I know, " he added, "because I've kept rabbits."

But the drums had seized the idea and had adopted it as their very own with enthusiasm. A small baby rabbit was purchased secretly.

The drums undertook to train the rabbit in the way it should go. And when it was trained so that it should not stray from the straight path: when it had been taught—as Boy Steevens stoutly insisted it could be taught—to stand up on its hind legs and salute when 'God Save the King' was played, then that trained rabbit should be solemnly presented to the Colonel in full view of the regiment.

The training of the rabbit was a tremendous business. They trained him with bugles and they trained him with cabbage leaves, on the whole the cabbage leaves were the more successful. They marched in line (in the seclusion of a field two miles from barracks) blowing their bugles and the rabbit marched in front. He marched in front because they marched behind him. He did not go exactly in the way they wanted him to go, but they went the way he went, and when he stopped to munch grass they stopped too and pretended they intended stopping. They trained him lifting him by the ears, and they trained him by prodding him with a stick, and on the whole he went better when they carried him than when they prodded him.

But there came a day when Horace (for so they called him) really gave the impression that he had of a sudden realised his awful responsibilities; when he walked with stately lope before the frantic bugle march and—wonder of wonders—when it seemed that he understood that 'right turn' and 'left wheel' had some special significance for a marching rabbit.

It was time indeed for the secret to be revealed and for the presentation to be made.

There was a Commanding Officer's Parade due for the Wednesday, for the General commanding the district was coming to make his half-yearly inspection.

"Wednesday's the day," said Boy Steevens, a perspiring little figure as he sat on his cot polishing the brasses of his snowy belt. "Wednesday, chaps—or never."

He was inclined to be melodramatic, this Boy Steevens, and was given to the collection of cigarette pictures—sufficient evidence of a romantic soul.

Wednesday morning came, bright and spring-like, and no more gallant sight has ever been seen that the old barrack square presented with its great elms vivid with tender green, and the scarlet and white of uniforms upon the golden gravel of the square.

The regiment was drawn up in column, eight strong companies at intervals, and before them the drums in their white ribbon-lace and their epaulettes.

A shrill bugle call, and with a crash the rifles of the battalion came to the slope as the General in his cocked hat rode on to the square, followed by his staff. A sharp order and the rifles came to the 'present,' the bugles and the drums sounded the 'general salute.' One drum did not sound.

With a quick motion Boy Steevens raised the head of his drum and lifted out a struggling rabbit.

"Horace, do your duty.'" he hissed, and the sphinx of the Wigshires loped slowly forward till he crouched by the side of the drum-major. That officer was quite unprepared for the apparition . With a nervous little squeak he jumped sideways.

The obedient Horace, not unused to such gyrations, followed with two quick lopes.

The drum-major looked around helplessly. Very gingerly he prodded Horace with the end of his gorgeous staff.

"Get away, bunny", he cajoled, but at that moment came the Colonel's voice—"Battalion will advance in column. By the left—Qui-ck march!"

Crash, crash, crash went the drums of the Wigshires; the drum-major's staff spun round and the whole battalion stepped forward, their heads erect: their shoulders square. Horace leapt away at the first rattle of the drums, dashed madly a dozen paces, looked over his shoulder to see what had happened, and dashed as madly back again and fell in by the side of the purple-faced drum-major, loping steadily forward to the music.

"What the dickens is that strange beast, Colonel," asked the General as the troops swung past.

Colonel Umfreyville fixed his eyeglass. "Looks to me like a rabbit, sir," he said.

A smile broke the stern lines of the General's face—he was a notorious joker. "Do you know," he said drily,"I thought for one moment it was your sphinx.'"

Which shows that there is much in common between drummer-boys and Generals.

"Yes sir," said the tearful Boy Steevens when the parade was dismissed and he faced the laughing officers, "he's mine. I—I thought I'd train him for a regimental pet."

"You had better train him for your dinner-table," suggested the Colonel.

"No, no.'" said the General, who stood by, "that would be too bad; after all, I agree—he is not unlike the sphinx."

"Except that the Egyptian sphinx hasn't a ridiculous woolly tail, sir, said the Colonel, his lips twitching.

"Beg pardon, sir," interrupted Boy Steevens eagerly, "perhaps there's an English sphinx."

"I never thought of that," said the General gravely.

And thus the Wigshires adopted a regimental pet.

FROM out of the mists ahead came three horsemen galloping quickly. They rose over the crest of a distant hill and disappeared into a hollow. A long interval, and then they appeared again, riding in line, erect as though on parade, seemingly oblivious of the fact that somewhere behind them an unseen enemy was 'sniping' them at his leisure.

Some of the bullets fell short and sent little fountains of earth spurting up from the ground. Some went overhead with a shrill whistle. One at least struck Birchington. Fortunately it was a ricochet that had lost much of its force. Yet it struck the steel stirrup with sufficient vehemence to twist his foot round.

He laughed quietly and did not draw rein. Birchington, a trumpeter of Birchington's Horse, was the youngest soldier in the field that day—was, indeed, the youngest soldier in the army serving in South Africa. Had he been a regular soldier he would have been left behind with the other boys at the base camp, for nowadays drummer boys do not go into the firing line, nor trumpeters of cavalry either, for the matter of that.

But young Birchington, though only fifteen years of age, was a favoured individual. His father, Colonel Birchington, had raised a corps which bore his name, a corps composed of young Colonials, with a sprinkling of English gentlemen who had come to South Africa on the outbreak of war on the off-chance of finding employment with the Army in the field. Colonel Birchington knew the country well. After he had resigned his commission in the British Army he had settled down to ostrich farming in South Africa with his young wife. She had died soon after Frank was born, and since that day the two had been inseparable—the hard fighting Colonel and his baby boy.

The authorities had accepted Colonel Birchington's offer to raise his corps, but had demurred when he suggested that his boy should accompany him in the field.

"He is very young, Colonel," said the Governor.

"That I admit, your Excellency, " said the Colonel firmly, "but the enemy have many boys of even a more tender age in the fighting line—a British boy can take the risk if they can."

The Governor smiled a little sadly.

"You must have your boy, " he said; "after all, you know how to take care of him."

So Frank Birchington, to his joy, became colonel's trumpeter to Birchington's Horse. There was no need for him to learn the calls. From his childhood he had possessed a little trumpet, and his father's servant taught him every call from Reveille to Lights out.

It was a proud boy who rode away from his father's farm to join the column. With his well-fitting khaki uniform, his long glittering sword at his side, a revolver strapped at his waist, and a polished brass trumpet at his back, he made a picture of which any father would be proud. From the toes of his brown top-boots to the crown of his broad-brimmed sombrero hat he was a soldier's son.

Now as he came galloping back to headquarters, a scout to the left and right of him, and the monotonous klick-klock of the Mauser rifles behind him, it seemed years since he had left the farm: it seemed another life that he had led before the call to war had come.

"Get over to the left, Frank," said one of his companions a little anxiously as a bullet fell between them; "we shall have the kopje as a background and our khaki will not offer such a good target."

Obediently the boy turned his horse. He had learnt that bravery is one quality, and foolhardiness another, though they are often confused. There was nothing to be gained by taking unnecessary risks. His father had impressed this fact upon him in their first engagement.

Frank had stood up in a perfect hail of bullets.

"Lie down, Frank," his father called sharply. He himself was crouching behind a convenient ant-hill.

"I am not afraid, father," said Frank, exalted by the sense of danger.

"Am I?" asked his father quietly, and with a blush of shame the boy realised the arrogance of his courage, and sank flat to the ground.

"You've got to remember, my son," said the Colonel that night, when they sat together at their evening meal, "that you are only useful to your country so long as you are alive. In my old days we had a saying that 'dead heroes cannot peel potatoes.'

They took their meals together, for the Colonel was no spartan father who demanded that the difference in ranks should separate them.

Frank and his two comrades gained the lower slopes of the kopje and began to skirt it, and in half an hour they had reached the camp.

The Colonel rode out to meet them. "Well, my boy," he said with a smile, "you have had your first lesson in scouting, what do you think of It?"

"It was fine."' cried the boy; "that is the work I should like to do. It's awfully uninteresting here, dad—we've had two little skirmishes in ten days and neither lasted an hour.'"

The Colonel eyed him thoughtfully.

"I think we shall have all the fighting we want very soon," he said, but would say no more.

Birchington's Horse, with a battalion of infantry and three guns, moved

out the next evening for a destination which was known only to the Colonel.

He did not share his confidence with Frank, because boys are boys after all,

and an indiscretion on Frank's part might have jeopardized the column's

safety.

The country abounded in spies; every farmhouse was a secret meeting place from whence news regarding the movements of troops was distributed to interested quarters.

It was against one of these farmhouses that Birchington's column was moving. In spite of Frank's disgust at the inactivity of the column Colonel Birchington had made himself extremely unpopular amongst the marauding commandoes. He moved swiftly and by the nearest way. He never lost his column amid the innumerable spruits and river-beds which abound in the country.

News had been received that a laager had been formed near Van Robeck's farm. A laager meant an armed camp, and it was believed that it formed part of the force of none other than the redoubtable De Wet.

Frank rode by his father's side in the darkness—they had not left the camp until the sun had sunk behind the big mountains to the westward.

They rode in silence for a while, the Colonel busy with his thoughts, and Frank too excited at the prospect of the coming fight to talk coherently He was an important factor in a night engagement. Infantry and guns moving out of sight in the gathering darkness would advance or wheel or retire at the sound of the brazen notes he blew—other forms of command were impracticable.

"Frank," said the Colonel suddenly, "you understand that to-night of all nights you take orders from nobody but myself."

"Yes, father," said the wondering boy.

"A night attack is a hazardous undertaking," the elder man said, "and it can only be carried out by one man. My orders to you are not to be countermanded. If I am wounded—yes, yes," he stretched out his hand and clasped the boy's knee affectionately, "these things happen—you are to take my last order and carry it out."

"I will, father," said Frank, blinking back the tears that rose to his eyes.

No more was said, for at that moment Major Galley-Bolder, second in command, rode up. The Major was one of those short, fussy men, irritable and apprehensive.

So far he had not shone in action; indeed, there were people who suggested that he had behaved with a caution bordering upon cowardice. He did not like Frank, and the dislike was reciprocated. He reined his horse alongside the Colonel's with an awkward tug of his reins, for he was not a good horseman.

"What is the idea of this march, Colonel?" he asked, endeavouring to disguise the irritation in his voice.

In a few words the Colonel enlightened him, dropping his voice so that the men who rode immediately behind could not overhear.

"I think a night attack is perfectly unjustifiable," said the Major hotly "It is endangering life which would not be endangered if the engagement were fought in daylight; hang it..."

"I do not think we need discuss that aspect of the matter," said the Colonel quietly; "the farm lies on the other side of Volkston Gap and the road leads through the Gap itself. If we can get through without opposition I shall put the guns on the hill to cover the farm and attempt to surround it."

"It's suicidal,"stormed the other; "why there may be a thousand burghers there..."

"And there may be a hundred," said the Colonel; "anyway, that is my plan."

The Gap was the key of the situation. As silent as ghosts the column approached it just as the dawn came east.

The gunnery officer had received his orders; with half a battalion of infantry he moved across the veldt to the right to take up a position on the hills, and the column halted to give him a chance of establishing himself. A mounted orderly brought news he had successfully reached the foot of the hill before the Colonel passed the word to advance.

It is said that in that period of waiting somebody (contrary to the strictest orders) struck a match to light a cigarette, and that that somebody was Major Galley-Bolder. Whatever happened, the enemy was warned.

As the head of the column deployed into the little valley a heavy fire broke forth from the left.

The Colonel breathed a sigh of relief. There was no sign from the right, the enemy had not divided his forces, and there would be opposition to the guns.

Frank's trumpet sent out a shrill order on the morning air and the column dismounted. Another call—and they were taking cover and replying steadily to the fire above.

The enemy's fusilade increased in vigour; they held a good position, and were, as the Colonel had feared, stronger than had been reported. Worse, they were moving stealthily along to flank his party. He moved ahead—there was no safer way, keeping a steady fire on the hill.

The guns should be in a favourable position by now and waiting orders.

Then as if by magic the firing on the hill ceased, and with a wild yell men broke from cover and came charging down the hill-side.

"Fix bayonets!" cried Colonel Birchington, and Frank at his side repeated the order. The onrush ceased. The men above had never intended charging—they desired only to take a more effective position, and this they had done.

The Colonel, with a sudden sinking of heart, saw his danger.

"Guns to open fire," he said sharply.

Frank's trumpet was half-way to his lips when he saw his father sway and fall. He was by his side in an instant.

"Father! Father!" he cried, but Colonel Birchington was dead, a bullet had pierced his heart.

Frank staggered back, white of face. Then he remembered his father's instructions and raised his trumpet.

A. hand grasped the instrument rudely.

"What are you doing?"

He turned to meet the livid face of the Major.

"Sound artillery retire, d'ye hear!" almost screamed the officer. "We're trapped. There is no way out of this!"

He wrung his hands in frantic despar.

"Sound it—we may get out—if they start shelling from the hill, they'll hit us.'"

Frank wrenched his arm free.

"I've had my orders, sir," he said, and his voice was broken and hard. He raised his trumpet and the clear thrill of the notes echoed from hill to hill.

"Stop!" cried the second in comnand. "I am in charge now, you young fool— what did you sound?"

"Commence firing," said Frank, and as he spoke three quivering pencils of flame leapt from the hill-side, and the crash of the artillery came like a thunder-clap.

The enemy wavered, the fire slackened instantly, and ere the guns spoke again the foe was in full retreat.

Yet the major had been prophetic, for although the fight was won, the first shell had fallen short, and father and son lay together in death, and near by was the stricken figure of the second in command.