RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

Edgar Wallace c. 1927.

In October, 1931, I sat with Edgar Wallace in his suite at the Metropole Hotel, Blackpool, which constituency he was fighting in the Liberal interest.

In furtherance of his candidature I was producing a bi-weekly publication, Wallace's Blackpool Banner, and we were discussing the layout.

"By the way," I said, "can you suggest another title for this article? I'm tired of writing 'Edgar Wallace, by Robert Curtis'."

Wallace considered for a second.

"Call it 'Edgar Wallace, by the Man who Knows Him Best'," he said.

And that is my justification, if any be needed, for this volume.

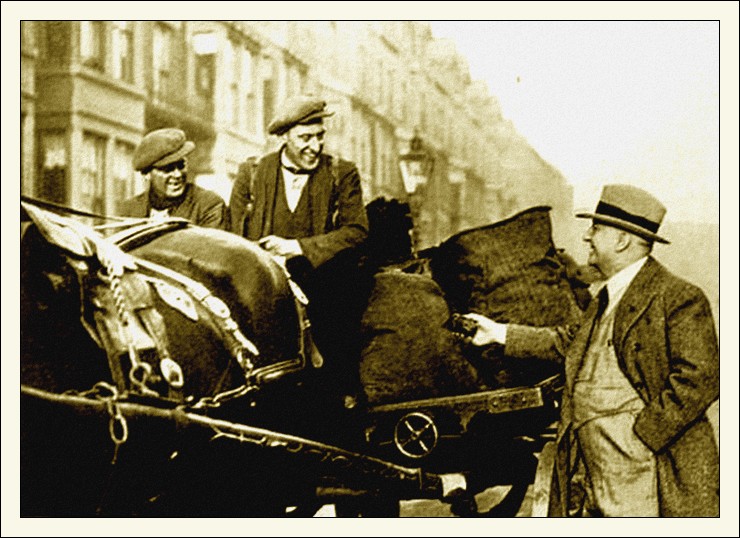

Edgar Wallace and Bob Curtis.

The last photograph taken when leaving for Hollywood.

Edgar Wallace did not write his most thrilling story; he lived it.

From the time when, as a ragged boy, he played truant from school and stood on the kerb outside the Press Club, selling newspapers in an effort to secure financial support for his love of ginger-beer, theatre galleries and "Devona" toffee, up to the time when, as Chairman of the Club, he entertained earls at lunch and drank his champagne from a pint tankard—it was one of the rare occasions when he would drink anything alcoholic—his life was a succession of episodes more thrilling than any serial story that came from his pen. I have often thought that if he had written the true story of his life as a novel, the public would have decided that his imagination had run away with him, and would have refused to swallow it.

"It is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace." They print that across the jackets of some of his novels. It is, no doubt, as regards his stories, one of those permissible exaggerations which a publisher may utter without a qualm. There must exist a small number of people who cannot read Edgar Wallace's stories at all; there are doubtless others who read them and are not thrilled; there are, I know, some who devour them in secret and contemptuously decry them in public.

I once met a man—he was a well-known barrister, who must, I think, have been getting into training for a seat on the Bench—who asked me, with a very promising effort at judicial innocence: "Who is Edgar Wallace?"

I told him, with equal innocence, that he was the owner of the Wallace collection, and I am afraid he disbelieved me. But while I had been awaiting him in his chambers, I had counted seven of Wallace's novels among his law books, and I happened to know that on the first night of Wallace's last play the eminent counsel had been in the stalls—with a complimentary ticket. There are many like him.

But though there may be people who find it possible not to be thrilled by reading Wallace's stories, I do not believe there exists a person so phlegmatic, or so blasé, or so completely insulated against the shocks of this mortal coil as to be in close contact with Wallace, for a few days, as I was for many years, without coming to realise the full meaning of the word "thrill." Life within the orbit of Edgar Wallace was a rapid succession of high-powered thrills. During the years of my association with him I did many things—most things—with Wallace. I worked with him, lazed with him, went racing with him, travelled with him, spent money, lost money, made money with him; was broke with him and racked my brains for a likely means of raising the next five pounds; succeeded, failed, laughed, grieved, even grew stout with him—to our common sorrow. But in all the years of our friendship there was one experience which, though I sometimes sighed for it, never came my way: I was never dull with him.

Life to Wallace was all thrills. He loved living. I have heard him say that he never awoke in the morning without thanking God that he was alive. Everything that was happening in the world was of intense interest to him. He saw drama all around him, revelled in being in the midst of it, and was grateful for the chance which each fresh day gave him of plunging into it anew.

Everything which he did, he did intensely, and had little patience with those who lived at low pressure. "If you can't get a kick out of what you're doing, Bob," he once said to me, "you've already got one foot in the grave."

When I was crossing from America a few days after Wallace's sudden death in Hollywood, one of the ship's officers approached me on the Sunday morning and asked me whether, since Edgar Wallace's body was on board, there was any special hymn which I would like sung at the service.

"Yes," I said, "there is. I should like 'Praise to the Holiest in the Height!'"

The officer looked doubtful.

"It's hardly the sort of hymn—" he began.

"It's the right hymn," I assured him. "I have chosen it because, if Edgar Wallace is anywhere now and doing anything, I know he is thanking God for it."

My first meeting with Wallace was in 1913. I was working in those days for the Dictaphone Company, transcribing on a typewriter the matter dictated on to the cylinders; and from time to time there were delivered to me large batches of cylinders containing literary and journalistic matter from someone who, for some reason or other, never divulged his name. All that I knew of the mysterious author was that his voice had a curiously husky quality, that his mispronunciation of various words made me shudder, and that he was always in a desperate hurry for the typescript.

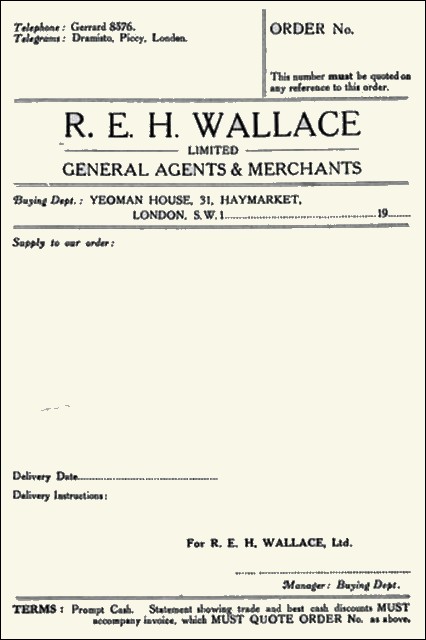

As time went on, I became curious and made inquiries, only to discover that all that was known in the office was that the client in question lived at an address in the Haymarket, and that the manager was as mystified and as curious about his identity as I. It was, I believe, the manager's suggestion that I should personally deliver the next lot of manuscript and see what I could discover. At any rate, I have always given him credit for the suggestion and been duly grateful to him.

A few days later I called at a flat in the Haymarket, and, on the pretext of having various queries to raise in connection with the manuscript, penetrated to the study, where I was received by a short, slim, decidedly good-looking man, with a rather pallid face and a neat upturned moustache.

I told him who I was, but my confidence was not reciprocated; so while we discussed as many points about the manuscript as my ingenuity could invent, my eyes were busy in search of a clue. I noticed that on the bookshelves there was a preponderance of novels by Edgar Wallace, and a number of them lying about the room, and before I left I had a shrewd idea that it was Edgar Wallace to whom I had been talking.

A few days later came the confirmation. Our anonymous client sent in some handwritten manuscript to be copied, and I promptly turned up the Edgar Wallace file in the office, compared the writing of the manuscript with that of several letters which bore his signature, found the handwriting unmistakably the same, and congratulated myself on having solved the mystery in a manner of which even an Edgar Wallace sleuth need not have been ashamed.

Wallace in those days, though he was, of course, well known in Fleet Street, was only just beginning to loom on the horizon of the general public as a writer of fiction, and I was puzzled to see why he should be at such pains to conceal his identity. Later, I discovered that there had been method in his mystery. He had acquired his Dictaphone on the gradual-payment plan, instalments were in arrears, and to reveal himself as the author of the manuscripts would have been to invite a peremptory invitation to pay up—which, since he was in the middle of one of his hard-up patches, he could not do—or return the Dictaphone, which, since he was also in the middle of one of his patches of high-speed writing, was unthinkable. Wallace had found himself in a predicament and had tackled his temporary difficulty in a manner with which I was later to become all too familiar.

The discovery of his identity—I casually addressed him as "Mr. Wallace" at our next meeting, and he only smiled—placed me in a quandary. I had to decide whether, out of loyalty to my firm, I should reveal his identity, or yield to the promptings of the friendship which had already sprung up between us—fostered, I fancy, by our common love of horse-racing, and the fact that we both considered ourselves to be among the cognoscenti of the turf—and allow Wallace to retain the Dictaphone.

Fortunately, I was spared making the decision.

"How much do you earn at your job, Bob?" asked Wallace a few days later.

I told hm.

"You're worth more than that."

I agreed—heartily.

"Have you got a typewriter of your own?"

I rapidly decided that the contraption in my possession might, with a little effort of imagination, be truthfully designated a typewriter, and said that I had.

"Then why don't you work for yourself?" said Wallace. "I've got no money, but I'll guarantee you a quid a week more than you're getting now, and you can do all my typing for me. Is it a bet?"

It was. I acquired a Dictaphone. It was, even when it came into my possession, a very ancient model, as different from the modern electric machine as is the modern aeroplane from the boneshaker. It was worked by clockwork, and the spring was so weak that I was lucky to get through a cylinder with less than three windings. But it served its purpose. With my dilapidated typewriter and my debilitated Dictaphone I transcribed hundreds of thousands of words for Wallace.

I shall never forget my first introduction to what I later came to accept, more or less philosophically, as the genuine Wallace method of writing a story. I had been transcribing his Dictaphone dictation for some little time, and was congratulating myself on the fact that I was earning a pound a week more and doing far less work than previously. But any dreams I had of a calm and leisurely fortune were soon to be shattered. I had occasion to call at Wallace's flat one Friday morning. Wallace, Dictaphone mouthpiece in hand, was seated at his desk.

"Hullo, Bob! Know anything?"

Throughout my long association with him that was invariably his first question when we met each morning. Wallace was always eager for a tip, and I have spent many an hour, while editors fumed for overdue contributions, arguing with him over the merits of our respective fancies for a race. If we agreed on the probable winner, it was backed by Wallace as a matter of course; if we did not agree—and as I have a liking for an occasional win I am glad to say that Wallace's selection was not always mine—he would prove to me conclusively that his horse was bound to finish first, that mine had not a dog's chance; after which he would ring up his bookmaker and back them both.

On this occasion we did not agree, and Wallace was in the middle of a most unconvincing demonstration that his horse could not avoid winning by three lengths, when he suddenly broke off.

"By the way," he said placidly, "I've a serial to do—seventy-five thousand words—and I'm going to turn it in by Monday morning. I'm broke and must have the money."

"Monday morning?" It was already midday on Friday and I had an uneasy feeling that Wallace was not being humorous. "Perhaps—by midday on Monday—if you've a good lot ready for me to get to work on—"

"I'm just going to start," said Wallace calmly. "But we'll do it—easily. You live at Hammersmith, don't you?"

I did. But I could not see that living at Hammersmith appreciably brightened the prospect of getting a 75,000-word serial dictated, typed, delivered and paid for by Monday morning. But Wallace saw.

"I'll start dictating right away," he said. "We'll get a corps of district messengers to carry the cylinders to you at Hammersmith as fast as I can dictate them, and we'll work all day and night. You're on a pony."

I was living in those days in furnished apartments, and I am afraid my landlady had three rather disturbed nights. All night long my typewriter clattered—I was in constant dread that either it or my feeble Dictaphone spring might collapse beneath the strain imposed on them—and the arrival every two hours of a district messenger to hand me a fresh batch of cylinders for transcription and take back the typescript to Wallace, must have sadly interfered with her night's rest. Wallace read the first ten pages of my typescript, and by the next messenger came a note:

Dear Bob,

I don't want to read any more of this. Do the fair copy straight away.

Edgar W.

P.S.—Know anything for to-morrow?

I suppose I did sleep some time and eat now and then between the Friday and the Monday; but the only impression of those seventy-two hours that remains with me is of a dilapidated typewriter ceaselessly clattering and of wrists and arms aching abominably. But the story was finished according to plan, and by midday on Monday the manuscript was in the publisher's hands, the payment for it in Wallace's, and my "pony" in mine. We had both earned it.

In this manner were written many of his subsequent stories, and I soon came to recognise in the early stages the symptoms of an impending spasm of high-speed work. While Wallace had money, he could rarely bring himself to settle down to writing, and at the first signs of financial tightness I came to realise that it would not be long before I heard the inevitable "Bob, I'm broke," and we should be plunging again into a whirl of furious activity.

How familiar that "Bob, I'm broke!" was to become! The calm smile with which Wallace invariably said it revealed the nonchalant temperament of the born gambler. Wallace, in everything that he did, was a gambler. Big risks had an irresistible attraction for him; big money lured him; but it was after the thrill of a big adventure that he hankered more than after the money. Money as such did not really interest him very much. It was just something which came along and was spent, but was not of any real importance. Money could always be made with a little effort, and, that being so, it was absurd to hoard it up. If there was money in the bank, Wallace would spend it, gamble with it, lend it, give it away—anything rather than save it. There was no thrill for Wallace in a money-box.

Most authors, I believe, find it impossible to do good work when they are worried, particularly if the cause of their worry is a financial one. If they sit down to plan a story, the vision of a Final Notice from the Gas Company floats before their eyes, and the prospect of the meter being borne away in a handcart effectually banishes inspiration. Truth is stronger than fiction, at least until some means has been found of preserving the continuance of the gas supply.

Fortunately, Wallace did not suffer from that disability. "Fortunately" because, had overdrafts, bills, threats of summonses and such-like prevented his working, many of his stories would never have been written. It seems that most creative workers are innately lazy and can rarely bring themselves to settle down to work until the bank manager becomes recalcitrant or at any rate shows signs of incipient restiveness. Wallace was no exception; and as he was blessed with a bank manager whose views on the matter of overdrafts coincided—almost—with his own, there were sometimes lengthy periods when no stories were written.

He rarely worked until stern necessity in some unpleasant guise was knocking at the door; and then he worked at tremendous pressure and was not in the least disturbed by the knocking. His incurable optimism always persuaded him that the story would be finished and payment for it received before stern necessity kicked the door down.

Unlike most authors, he did his best work under the stress of financial stringency. When he was in funds, work was postponed to that distant date when money would be short again. Having survived one financial crisis, he always seemed to imagine that the next was only a vague possibility of the distant future, and promptly proceeded to do everything most calculated to expedite its arrival. At such times editors might be screaming for stories, but if the voice of the bank manager was silent or not too reproachful, the siren whisper of Epsom or Newmarket would always drown the editorial clamour, and only a very bad day on the racecourse would persuade him to give a sympathetic ear to the outcry.

I have often felt grateful to the providence which ordained that Wallace should not win the Irish Sweepstake. Whatever the state of his finances, he always contrived somehow to have about £40 worth of tickets, but luck never came his way. Had it done so, I am sure that I should have had no work to do for months. Even Wallace, I imagine, would have needed a month or two to dispose of the first prize in the Irish Sweep.

It is not surprising that Wallace, who honestly believed, as I have often heard him say, that money is one of the things in life which do not matter in the least, was frequently in financial difficulties. His temperament made it inevitable that his life should be punctuated at fairly regular intervals by financial crises of varying acuteness, and a graph of his bank balance during almost any selected period of his life would have been a zigzag affair of sudden ups and downs no less erratic than a meteorological chart of an English summer.

Often in my days with him I watched him carelessly wandering deeper and deeper into a jungle of debt from which I could see no hope that he would ever extricate himself and was convinced that Wallace at last had come to the end of his financial tether and that a crash was inevitable.

But that was before I had got to know Wallace and his methods. He was by nature a fighter, and he fought best when the boats had been burnt behind him and he must go forward or surrender, and I never knew him—not, at least, until the last few years, when he began to show unmistakable signs of overwork and nerviness—get rattled or even seriously worried over money matters. There was always a way out of the most bewildering financial maze, and the ingenuity he displayed in discovering the solution, the coolness with which he carried out the hair-raising expedients to which he was sometimes forced, were qualities which, had he chosen to turn his attention to Throgmorton Street instead of Fleet Street, could hardly have failed to win him a place among the world's financial magnates.

Wallace, I am sure, would not have been content to be less than a magnate.

He was incurably generous. It was one of the most lovable traits in the character of the most lovable man I have ever known. He scattered his benevolence with as lavish a hand as he scattered money on any other object. He was lovably and lamentably sentimental. Almost any story of hard luck and poverty, no matter how blatantly untrue, was enough to send his hand groping for his wallet, and there was no lack of unscrupulous spongers to take advantage of his unselfish generosity. It became a by-word with the indigent parasites who always hovered around him, as well as among those who were in genuine need of help, that Wallace was always "good for a fiver."

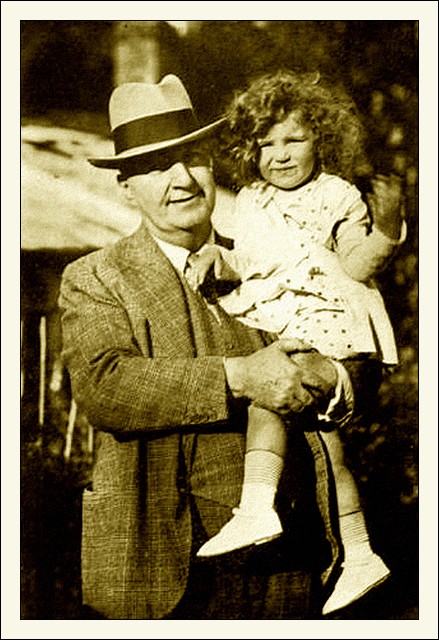

Edgar Wallace with his Wife and Elder Daughter Pat.

I was in his study on one occasion when an old friend of his came in with an all too familiar request.

"Can you lend me a tenner, Edgar?"

Wallace, I knew, was at the moment in sore need of money himself, and I expected a regretful refusal.

"Tenner?" said Wallace. "I really don't know, old man. Wait a minute and I'll see how the Pals Account stands."

The friend left with a cheque for fifteen pounds.

It was only then, though I had been closely associated with Wallace for some time, that I discovered about the Pals Account. It was a special account into which, in his periods of affluence, he paid such money as he could spare for the specific purpose of meeting requests of this kind. His quixotic generosity was charming but ruinous. He would have been a much wealthier man if he could have found it in his heart to say "No" to a request for money. But an Edgar Wallace who could refuse a helping hand to one who asked for it would not have been Edgar Wallace.

I think he was fully aware of this improvident streak in his character. I remember the first occasion on which I asked him for a loan. It was only a fiver that I needed to help me through my financial morass, but I approached him very diffidently. I need not have felt any qualms.

"Sure, Bob," said Wallace promptly. "Never be hard up for a fiver. I used to be, so I know what it's like. I'm hard up nowadays for fifties and hundreds. I suppose one day I'll be hard up for thousands."

He was.

That, I suppose, was the secret of his inexhaustible generosity: he could never forget the days when he had been poor. Throughout his romantic journey from a courtyard in Deptford to a suite of rooms at the Carlton, the poor and unfortunate were always with him. He used to say humorously that it was the literary fare provided for him at Sunday School in his days of childhood that was chiefly responsible for his inability to say "No" to a request for help. It included a story called "Christie's Old Organ," over which he used to ponder and weep. The moral of the story was that one ought to be kind to people less fortunate than oneself, and Wallace reckoned that the complex introduced into his mental system by that Sunday School reading had cost him many thousands of pounds in the course of his life. How thoroughly he had taken the moral to heart!

With the best will in the world it was not always possible to produce the needed cash for charitable purposes, but I never knew Wallace fail to do something for a friend who was in genuine distress. His name was good security for a bank overdraft, if all else failed, and whatever the state of his own account he would lightheartedly put his signature to the guarantee form. After all, signing one's name was a delightfully simple way of getting fifty pounds for one's friend, and one could not let a pal down, anyway. I wonder how many such forms bearing Wallace's signature there were scattered about the country at the time of his death!

I remember once venturing a mild protest when, in the midst of one of his most perplexing financial tangles, he had casually guaranteed an overdraft of £60 for a man who was a regular applicant for his charity, and who, as Wallace had admitted to me, had never been known to repay a loan.

"He's hard up, Bob," was Wallace's excuse.

"So are you," I reminded him.

He shrugged.

"And it's a thousand to one," I added, "that So-and-So will let you down."

Another shrug.

"Being let down doesn't matter."

That was always Wallace's attitude. Anyone might let him down—hundreds did—and it was accepted with a shrug and a smile. It was all part of the great gamble, and the true gambler does not squeal when he loses. I never knew Wallace bitter or resentful at being let down by someone whom he had trusted and helped, and the all too frequent experience never hardened his heart.

When he wanted to lend a helping hand he had a charmingly tactful way of doing it. It was he who, when I had been working for him only a month or two, suggested that, instead of working in my lodgings at Hammersmith, I should take an office in the West End and start a typewriting agency of my own. I agreed that it was an excellent plan, but with the small clientele which I then had, renting an office was a risk which I did not dare to take.

"Take the office, Bob," said Wallace, "and I'll pay half the rent."

Protest was useless. It was to suit his own convenience, he assured me, that he wanted me to do it. Hammersmith was a long way from the Haymarket, and he wanted to have me close at hand, so that a telephone call would bring me to his flat within a few minutes. If I wouldn't agree to his suggestion, he would rent an office himself and let me work there.

I took the office, and Wallace paid half the rent, and I pretended to believe that it was entirely for his own benefit that he did so. But I have never forgotten that it was to his generosity that I owed my first start in a business of my own. I did all Wallace's work, and, with that solid foundation on which to build, the business grew apace.

And then came the war. This parted us. One morning in April, 1915, after worrying over the question for months, I suddenly decided to join up, packed away my typewriter and Dictaphone, and, without telling anyone of my intention, put myself at the service of His Majesty. I think I took it for granted that Wallace expected me to go sooner or later, and I did not mention the matter to him until my enlistment was an accomplished fact. Then, in all the glory of my new khaki kit, I called at his flat, confidently expecting his whole-hearted approval both of what I had done and of my soldierly bearing.

I was sadly disappointed. Whatever he may have thought of me as a specimen of England's fighting forces, Wallace certainly did not approve of what I had done. He was hurt and angry. He took the view that I was basely deserting him when he badly needed me, that I should have consulted him before enlisting, that I had shown an utter lack of consideration for him, and that I should make a rotten soldier anyway. He said he would see what he could do to get me out of the Army again immediately, and we would start to work on his new serial on the following Monday. Our relations, when I left him that morning, were decidedly strained.

A few days later, having been warned that I was sailing for Egypt almost immediately, I called again to bid Edgar good-bye—and found a very different Wallace from the one I had last seen. He was all anxiety to do everything possible to enable me to go with an easy mind. My whole family, he assured me, would be under his wing until I returned, and I was to worry over nothing. He was terribly sorry that I should be missing the best part of the flat-racing season.

I shall always remember his words to me as he shook my hand on parting.

"After all, Bob," he said, "you'll be helping to write history, and I only write popular fiction."

When he had spoken of my helping to write history, Wallace had been nearer the truth than he had suspected. I was invalided home from the East in 1916, and in 1917, on my discharge from hospital, was appointed confidential clerk to Field-Marshal Lord French, who at that time was Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces.

Lord French was engaged in writing his famous book "1914," dealing with the war, and my time was almost entirely occupied in taking down the book in shorthand from his dictation and transcribing on the typewriter. Fate seemed to have predestined me to be associated with the writers of thrilling stories.

Lord French, incidentally, had one characteristic in common with Edgar Wallace; he could very easily be distracted from the work of literary composition. With Wallace it needed only a race meeting to make him abandon desk, Dictaphone, secretary and editors and set off lightheartedly for the course; with Lord French it was usually some detail in the events which he was describing that caused him to interrupt his dictation.

He would suddenly pause, get up from his chair and go to a large-scale map of the Western front which hung on the wall, and indicate a spot with his finger. "You see, Curtis, it was like this," he would say.

"We were here, and the enemy was there, and the problem I had to solve..."

And that would be the end of work for that morning. It was intensely interesting, but I must admit that military strategy and tactics were less intelligible to me than the strategy and tactics of Wallace's crooks.

As soon as I was discharged from hospital I called on Wallace, and found him sitting at his desk, with his usual smile, and his Dictaphone mouthpiece in his hand. He might have been sitting just like that ever since I had left him.

"Hullo, Bob!" was his greeting. "Know anything?"

"All I know," I answered, surveying him critically, "is that while I've been away you've added several inches to your waist measurement."

Wallace said that was the worst communiqué from the front that had so far reached him. He added that during my absence he had had nine different typists, only one of whom could spell, or understood the uses of a comma, and he had just started a new serial which he wanted me to type. I must somehow wangle it to get free of my job with Lord French and return to the Wallace fold.

We agreed on a compromise; there should be no attempt at wangling, but I would do all the work I could for Wallace in my spare time. He felt, I think, that he was treating Lord French very well.

Demobilisation set me free in 1919, and I again started my own typewriting business, doing most of Wallace's work for him as I had done before the war. This continued for several years. But reviving a business which had been dead for a long while was no easy matter. For a time I managed to keep it breathing, but only just. Everything at that time went wrong for me, and at last, when I could carry on no longer, I decided that the only thing to be done was to pocket my pride and tell Wallace just how matters stood. Reluctantly one day I went to see him, counting on his ingenuity to suggest some way out of my difficulties.

But I had counted on the wrong quality. His generosity was greater even than his ingenuity. He did not let me get very far with my story.

"You'd better come and join up with me as my secretary, Bob," he said. "I've got no money, but I'll guarantee you four pounds a week."

Still the great-hearted gambler! Wallace told me later that he had always wanted me in his permanent, whole-time employment, but had never till then dared to commit himself to paying even a small regular salary.

So began a still more intimate association with him which was only broken by his sudden death in Hollywood. They were stirring years, full of interest and packed with thrills; and not the least of the thrills were those afforded by Wallace's financial vagaries.

He was a lavish spender. The habit of counting the cost of anything in advance presupposes a measure of prudence and cautiousness which was not included in his make-up. In his heart I think Wallace had a contempt for prudence and cautiousness as virtues of a negative type which had something rather petty about them. He had scant sympathy really for the man who would first dip his toes in the water, and then, if it were not too cold, wade cautiously out and be careful not to swim beyond his depth. The right way was to take a header from the topmost diving-board and trust to providence that the water was deep enough to prevent your skull being cracked on the bottom.

Optimism and self-confidence were two of Wallace's predominant qualities. If he wanted a thing he would never pause to consider whether he could afford it; he bought it. His optimism persuaded him that he would manage to pay for it somehow; his self-confidence never failed to convince him that he could make money just whenever he wanted to. Economy was a word of which he may possibly have heard, but which never intrigued him sufficiently to make him inquire into its meaning.

His motoring was a fair example. Wallace abominated walking. After the war, before the halcyon days of Portland Place, Bourne End and the Carlton, he was living in a flat in Clarence Gate Gardens, Baker Street, which was approached by a flight of, I believe, twelve or thirteen steps; but he invariably went up and down by the lift.

Tubes, 'buses, or even taxis never seemed to commend themselves to him as methods of transport worthy of his serious consideration, and he formed the comfortable but expensive habit of hiring a large and luxurious limousine car on any and every occasion.

His bills from the hire company were appalling, and on the arrival of one such account I prepared two statements which I hoped would so impress Wallace that he might take steps to bring down his motoring expenditure to a more reasonable figure. One statement showed the sum he had spent on car hire during the preceding twelve months, and the other, which set out the cost of running a car of his own, including chauffeur's wages, garage, running expenses, etc., proved conclusively that by becoming a car owner he could effect a very considerably saving.

I showed the statements to Wallace. I am sure he was impressed, because he remarked that I should make a very good accountant. And that, for some years, was as far as it got. I should have known better than to introduce that word "saving" into the conversation. I am sure it scared him off.

Eventually, of course, he bought a car. It was a handsome car, but I never could bring myself to like it, for it was the cause of my unwittingly letting Edgar down. There arrived at the flat one afternoon his bank manager, a charming and long-suffering man. Wallace, in the midst of an overdue instalment of a serial, had heard the call of the turf and gone off to a race meeting, so I entertained the manager with a cup of tea, and sat and chatted with him in the study. In the course of our conversation I casually mentioned that we had just bought a car, and I wondered why the bank manager sighed and looked so wistful.

I understood a few days later, when there arrived a letter from the bank, couched in gently reproachful terms, regarding the amount of Wallace's overdraft.

Up to that time I had not been fully admitted into Wallace's confidence as regards his financial affairs, or I should certainly have conducted his bank manager along some less hazardous conversational path. Edgar, I fancy, realised the risks to which such reticence exposed him, and thereafter in money matters there were no secrets between us.

From that time the standard of our motoring comfort and elegance rose by leaps and bounds. Once Wallace had started buying cars, it was difficult to stop him, and ultimately we arrived, as I knew we were bound to arrive, at the crowning dignity of a Rolls-Royce.

The Ringer, Edgar's most successful play, had been produced a couple of weeks previously by Sir Gerald du Maurier at Wyndham's Theatre. It had met with instant success, and cheques for such heartening sums in respect of royalties had begun to arrive that I began to fear that, as long as the play was running, squeezing blood from a stone would be a simple matter compared with extracting articles or stories from Wallace. He was making bigger money than he had made for a long time—bigger, perhaps, than he had ever made—and I knew that something was bound to happen.

"Bob," said Wallace one sunny morning, after duly inquiring if I "knew anything" and making a bet with his bookmaker over the telephone which sent a cold shiver down my spine, "Bob, we're doing well."

Spring was in the air, but Wallace did not need that stimulus to be himself. I cautiously agreed that the prospects were less gloomy than they had been recently, but doubted if they were sufficiently dazzling to justify the bet he had just made. There was a look in his grey eyes of which I was afraid I knew the meaning.

Wallace grinned.

"Let's play up the luck and buy a car."

"But you've got a car—" I began.

"A good car," said Wallace, and picked up the receiver of his telephone.

His idea of a good car was on a par with his ideas of most other things; what it lacked in prudence it made up for in bigness of conception. There glided up to our doorstep a few days later a luxurious limousine of the most expensive type obtainable—to be superseded a year or so later by another, still more luxurious and expensive, which, as it stood shining and glistening by the kerb, made even Portland Place look poverty-stricken and in need of a fresh coat of paint.

Everyone who saw it admired it—with one exception. Captain Erskine-Bolst, M.P., who was Wallace's political opponent in Blackpool at the last general election, referred to it in one of his speeches as "that yellow horror." Thus can political prejudices blind us to true beauty. To Wallace that remark was, I fancy, the unkindest cut of all in a campaign by no means notable for its freedom from personalities.

Edgar did everything thoroughly. Having turned his attention to cars, he saw the matter through in his usual free-handed way. Every member of his family, with the exception of his youngest daughter, Penelope, whom, since she was only four years of age, he was reluctantly compelled to pass over, was presented with a car, and a whole fleet of vehicles was garaged in the mews behind the house. Wallace at this time was making a very big income, and he continued to play up his luck. He had a beautiful country house at Bourne End, a flat in Portland Place, a furnished flat in the Haymarket, which was used exclusively as an office and was rarely occupied by anyone but myself and an assistant secretary, and a suite of rooms at the Carlton, with a private telephone line to the Haymarket premises.

I remember receiving an urgent summons one Sunday to go down to Bourne End, and drove there in my car. It was a very old car; it had been middle-aged when I had acquired it; its sole claim to survival was that it went.

Edgar's Rolls, with its long, shining body, stood in the drive, and I stopped my contraption beside it with a screeching protest from the brakes which was more than usually strident. Wallace, not unnaturally, came out to discover what was responsible for breaking his Sabbath peace. He strolled around my car, inspected the licence, rubbed the door panel with the tip of a finger, peered at the spot he had laid bare, and gave a quizzical smile.

"According to the licence, Bob, your car is blue," he said laconically, and led the way into the house.

There was work to be done that afternoon—Wallace did much of his work during the week-ends—and no further reference to my car was made. I did notice, however, that as I started up the engine to leave, Edgar sighed and eyed the bonnet reproachfully.

The next morning he called me into his study.

"Bob," he said, "The Squeaker's just being produced in New York, and if it's a success I'm going to buy you a new car."

But he could no more be patient in his generosity than he could be patient in anything else. Within an hour came another summons to his study.

"I've been thinking," said Wallace. "The Squeaker doesn't come on in New York for a month yet, and your car will never hang together till then. You'd better take a stroll along Great Portland Street and buy yourself one."

I began to thank him, but he would not listen. Once again he was only doing it from purely selfish motives. If people saw his secretary in a ramshackle vehicle such as I drove, they would suspect him of paying me a starvation wage. It was a little thin, and no pretence of believing it.

"It's frightfully kind of you—" I began.

"Besides," interrupted Wallace, "you leave the atrocity outside the house, and as a residential district Portland Place is being ruined."

Within an hour I had added yet another saloon, blue beyond all question, to the ever-growing transport facilities which were at our disposal, and Edgar, with his usual nonchalance, signed the cheque.

In those latter days of prosperity Wallace had a large staff of servants—a valet, two footmen, two chauffeurs, several gardeners, a butler, a groom, and the usual complement of housemaids and parlourmaids and cooks and what-not. I wonder, had he lived to return from Hollywood, how many cars he would eventually have had attached to his establishment!

His recklessness in involving himself in financial difficulties was only equalled by his ingenuity in getting out of them. There was, of course, always the final resort of writing a story—either a short story or a serial, according to the exigencies of the crisis. But writing a story, even given the inclination to do so and a day when there was no racing to lure him from his desk, required a certain amount of time; and in the earlier days of my association with him, when the financial crises were of constant occurrence and pronounced acuteness, time was usually an important factor. As an accessory in many of his financial machinations I went through some of the most nerve-racking ordeals of my life. Wallace, even at the most crucial moments, never turned a hair. I used to wish sometimes that a hair or two had been capable of turning.

He walked into my room one morning with his usual smile and made the all too familiar announcement.

"Bob, I'm broke."

I made no comment. I waited to hear whether a story was to be written at breakneck speed or some new ingenious scheme for raising the wind to be put into operation. I was prepared for almost anything—except for Wallace's next remark.

"Write me a cheque on your account for a couple of hundred, will you?"

I stared at him, dumbfounded. He was as well aware of my financial instability as I was of his, and though he might not know, as I knew, that the balance in my account, if the bank had met the last cheque, was £2 on the debit side, he must know that he was asking me to write a cheque for about ten times the largest sum that ever stood to my credit for more than a couple of days.

"It's all right, Bob," he said easily. "I must have two hundred quid this morning, and I can't think of any other way of raising it. But I won't let you down. You shall have the cash to pay in before the cheque is presented."

I wrote the cheque. It was the first cheque for a three-figure sum that I had ever drawn, and there was only an overdraft of £2 to meet it; but I signed my name with an air of nonchalance which must have satisfied Wallace that he had a promising pupil. I would not have signed that cheque for any other man alive.

It was a tribute, I think, even to Wallace's well-known loyalty to his word—"Thou shalt not let anyone down" was his eleventh commandment—that I thought no more about the matter until, the following afternoon, he thrust a wad of five-pound notes into my hand.

"Thanks, Bob," he said. "You'd better go and pay it in at once."

As I entered the bank I had a sensation that something was amiss. The cashier's welcome, never any too cordial, was noticeably chilly; I noted that the clerks were staring at me over their ledgers with unfriendly eyes, and I do not think it was fancy that the bank messenger sniffed as he passed me. Someone tapped my shoulder.

"The manager would like to see you, Mr. Curtis."

The manager, scowling and frigidly distant, had a question to ask. Why, he demanded, when my account was already overdrawn, had I had the criminal temerity to utter a cheque for two hundred pounds? The cheque, of course, had been dishonoured, and he awaited an explanation.

I did my best to give him one, but he was not in the least interested. I flourished my wad of notes, but it was like a red rag to a bull. By some unexpected mischance the cheque had been presented earlier than it should have been in the normal way—Wallace knew to a nicety all details concerning the clearing of cheques, and none was more skilled than he in the tactical use of an account—the money had not been there to meet it, and here was an infuriated manager demanding to know what I meant by it and refusing to let me answer. Finally he intimated that, as soon as I had repaid my £2 overdraft—plus interest—I might consider my account closed.

"Sorry, Bob," said Wallace when I told him what had happened. "But you can open an account at another bank, and I'll guarantee the overdraft."

My bank manager in those days had never shown me any marked affection, and I am afraid that this incident turned his diffidence into something very like hatred. If time has not mellowed him, it may be some slight balm to his outraged feelings to learn that, all unwittingly, he shared in a scheme which, at any rate for a few hours, helped one of the best of good fellows out of a serious difficulty. Had he known Edgar Wallace as I knew him, he would have done the same for him himself.

But Wallace had more original and ingenious methods than that. He was a great opportunist, and none knew better than he how to turn present circumstances to his own advantage.

At one time, when he was writing the racing column for a well-known journal, he struck a more than usually barren patch. It lasted so long without showing any signs of improvement that I began to wonder whether Wallace had lost his skill or was suffering from an unprecedented dearth of ideas.

"Bob," he said one morning, "why shouldn't I be a tipster?"

I had thoughts of pointing out, as a reason why he should not, that the number of winners among the horses he tipped in his racing column was negligible. But I remembered that no tipster would consider lack of winners among his tips a disqualification for his business, and contented myself with expressing the opinion that, if the tipster's business was intended as a money-making project, writing a story would doubtless prove far more remunerative.

"I've got an idea," said Edgar, his eyes alight with excitement.

"Joe Austin" was not the actual name under which Wallace chose to carry on his tipping venture, but it will serve. Not many days later some thousands of persons who were interested in racing received a circular letter from one Joe Austin, setting out in glowing terms the qualifications which entitled Joe to their confident patronage, and the prospects which were theirs if they had vision enough to follow, and, of course, pay for, his advice.

Joe, it appeared, was in the habit of receiving last-minute information from sources of unimpeachable reliability concerning the winners of certain races. He was to receive one such titbit next week—for a race on the Wednesday, let us say. It would be absolutely last-minute information and he would not himself receive it in all probability until the morning of the race, but he undertook that to every person who forwarded him the sum of one shilling the tip should be communicated before midday on the Wednesday. It was a cleverly written circular with the authentic tipster's touch about it. In the subtle way which such circulars have it somehow persuaded one against one's better judgment that Joe Austin was a man with unequalled means of securing secret information and of irreproachable integrity. I have received hundreds of tipsters' circulars in my life, but I have never seen one better calculated to coax a shilling from a punter's pocket.

Wallace showed me the circular—he had spent a long time on its composition—and asked me what I thought of it; and, though experience had made me a very hardened sceptic, if I had not known that Joe Austin was Edgar Wallace, in whose racing tips I had learned to place only the very feeblest confidence, I should have handed him my shilling, ill as I could afford it, there and then.

I had only one criticism of the circular to make. Wallace, like most authors, was not incapable of making grammatical slips, and part of my duty as his secretary was to stand as a watch-dog between Wallace and the purity of the English language, and put such trifling lapses right. I never troubled to point them out to him. But he was sending the circular straight away to be duplicated without my having an opportunity to edit it, and there were two mistakes so glaring that I felt in duty bound to point them out.

"Anything wrong?" inquired Wallace, noting, I suppose, my pained expression.

I handed him the letter.

"If the subject of a sentence is in the plural," I said, not, I am afraid, without a hint of superior knowledge in my manner, "it is invariably followed by a verb in the plural. See paragraph one. And in the second paragraph 'was' should be 'were'."

Wallace grinned.

"I put those mistakes in purposely," he said.

I suppose I showed my perplexity.

"Because," he explained, "Joe Austin is a genuine racing tipster. Did you ever get a letter from a racing tipster which didn't contain a mistake in grammar?"

I was silenced. Wallace, I realised, was right. With his customary thoroughness he had made Joe Austin true to type down to the very smallest detail.

The circulars despatched, we waited for the result—Wallace with his usual optimism, I with decided misgivings. Joe Austin's ungrammatical letter did the trick; letters containing coin, postal orders or a shilling's worth of stamps came pouring in, and my uneasiness increased. At length I ventured to broach with Wallace the cause of my misgivings.

"All these people are sending you money," I said, "which they probably can't afford. They're banking on your giving them a really good tip—"

The look of reproach in Wallace's eyes made me pause.

"That's all right, Bob," he said. "I'm not going to let them down."

"But if you've no real information to hand on to them—"

"I have," he said. "I've a good 'un for the big race on Wednesday. So-and-So"—naming a famous jockey—"gave me the tip a week ago. It's the biggest certainty there's been this season, and he told me to put my shirt on it."

He waved a hand towards the pile of postal orders on the table.

"I'm giving them good value for their shillings," he said, "and they're providing me with the shirt. That's fair enough, isn't it?"

I might have known it. Wallace was incapable of being anything but fair.

By the Monday morning Joe Austin's letter had brought in over £200 in shillings, and Wallace was delighted. I did not share his delight. I could not for the life of me see how the scheme was even to pay its way, let alone show the handsome profit on which Wallace was counting. Each client had forwarded only one shilling; each telegram to be despatched on the Wednesday morning would require a shilling stamp; the printing and postage of the circulars had to be paid for according to all the established rules of book-keeping the net result on Wednesday must inevitably be a balance on the wrong side. I did just hint at the likelihood of such a contingency, but Wallace only grinned.

On the Monday evening I understood. That night Joe Austin posted to all his clients a second letter. It gave the name of the horse which was the "good thing" for the race on Wednesday, and stated that, as the information from the unassailably reliable source had already come to hand, Joe Austin was passing it on to his clients immediately. The tip was the biggest racing certainty of the season, and some of them might wish to indulge in ante-post betting.

Only about a dozen telegrams had to be sent to clients whose shillings arrived too late for a letter to reach them in time, and the difference between the total sum received in shillings and the total expenditure on 1½d. stamps and the circulars, was roughly £200. Wallace, of course, had had it all mapped out ahead and had never intended sending telegrams.

He himself put his shirt on it. On the Tuesday he put the whole £200 on the horse in question, and when, in the afternoon, I went to his study to tell him that the horse had won at 6-1, he only nodded.

"Did you back it, Bob?"

I admitted to a modest bet of 10s.

"That's all right," said Edgar. "I put ten quid on for you."

That was the end of the tipster's business. Wallace was in funds again, there was no further cause for immediate anxiety, and consequently Joe Austin was consigned to those realms of imagination from which he had originally come.

By some such ingenious expedient we weathered in those early days the frequent financial hurricanes that bent us. Wallace was nothing if not ingenious. As an exhibition of ingenuity combined with nerve, I think that one of his bouts with the unfortunate Inland Revenue official to whom fell the arduous task of extracting income tax from Wallace, would take a good deal of beating.

Wallace, at the time in question, was the owner of a certain two-year-old racehorse. In common with many another which later joined his stable, its chief failing was that it was not a very good racehorse; but it cost him a great deal of money to keep and run, and in the hope, I imagine, of making it pay some slight contribution towards its board and lodging, Wallace conceived the idea of claiming a rebate of income tax on the sum which the animal annually cost him. He explained to the income tax collector that, as a racing journalist whose duty it was to supply the readers of an important daily newspaper with information concerning the merits of racehorses, he found it absolutely essential to the efficient execution of his job to keep and run a two-year-old of his own. Only by this means could he satisfactorily get a line on the form of other two-year-olds and give his hundreds of thousands of readers the reliable information which they expected from him. Running a racehorse of his own was therefore a regrettable but necessary expense incurred solely to enable him to carry on his business as a racing journalist, and the total sum spent each year on the animal should be deducted from his rateable income and exempted from tax.

Wallace, however, though I think he deserved to, did not get away with that. The income tax official, seeing visions, I suppose, of a future stable full of thoroughbreds of varying ages, all of which were regrettable but necessary expenses incurred solely to enable Wallace to carry on his business, shook his head and would have none of it.

It is significant, perhaps, that in recent years the would-be collector of Wallace's income tax had a favourite monosyllabic expletive to which he would always resort on the occasions when most of us would indulge in a hearty "Damn!" The expression most frequently on his lips was "Gloom!" How far the daily disappointments of his occupation were responsible for his morose manner of swearing is an open question. If he had many taxpayers like Edgar Wallace on his books his pessimistic taste in expletives is readily explained.

It was typical of Wallace that he always imagined during a fair spell that the weather had permanently changed for the better and that hurricanes were things of the past, and that, when the next one showed signs of approaching, he remained serene and undisturbed until it was in full blast. Only then would he begin to take counsel with himself as to how shipwreck could best be averted.

His schemes were not always successful, but failure seemed as powerless to depress as was success to elate him unduly. The one was met with a shrug and the other with a smile; but neither, I think, was of supreme importance. It was the fight that appealed to him, and if one scheme turned out disastrously, he usually had another no less ingenious with which to replace it.

Wallace had a wide first-hand experience of crooks and their ways, having mixed with and got to know personally criminals of all types, from the petty larcenist to the murderer.

Quite a number of men with a first-hand knowledge of the inside of one or more of His Majesty's prisons visited him from time to time and were interviewed in his study—ferocious-looking customers, some of them, whose appearance at the front door inspired terror in the housemaid. More than once she came to me in grave anxiety and urged me, while "that man" was in the study, to stand outside the door in readiness to lend assistance if Wallace should be in need of it. But they all seemed very docile fellows, and Wallace, in any case, knew how to handle them.

Some of them, at any rate, I found interesting. With one in particular who had recently served a term of imprisonment for doping racehorses, I spent many a pleasant afternoon in Wallace's flat. Edgar, I believe, was proposing to write the man's confessions for some newspaper, and he came to the flat to supply the necessary copy, but Wallace had usually gone racing, and I was delegated to receive the confessions in his stead.

"Confessions" was hardly an apt word. There was nothing of the penitent about the gentleman in question. He was quite frankly proud of the fact that he was considered the most expert doper of horses in the business, and that if a four-year-old were to be substituted for a three-year-old and run in a three-year-old event—a not uncommon occurrence, he assured me—he was among the few skilled craftsmen who could be relied upon so to fake the substituted horse that it could not be distinguished from the animal actually entered for the race.

As a testimonial to his skill he told me that the Cambridgeshire was once won by a substituted horse which had been honoured with his alterations, and that another of his masterpieces even got past the keen scrutiny of Steve Donoghue, who had many times ridden the real animal.

As a sideline he was a cardsharper. His hands were like shoulders of mutton, but it was amazing what he could do with a pack of cards, and though on several afternoons Wallace and I sat one on each side of him and never took our eyes from his hands, neither of us was once able to see anything amiss.

Wallace, I fancy, had helped him on his release from prison, and the man seemed more than anxious to do something to show his gratitude. He was picking up the threads of his horse-doping connection again, he told me, and would soon be in full swing once more. Whenever he was doping or faking a horse for a race he would give Wallace the tip, and he could put his shirt on it.

He kept his word. For several months after he had left London telegrams arrived from him from time to time giving Wallace the promised tips. Usually the horses won. One of them carried off one of the most important events of the year. But Wallace, with that punctilious honesty which characterised him, would never back them. Racing was very dear to his heart and he hated to see it smirched with crooked dealing.

Incidentally, our horse-doping friend expressed to him an opinion which, coming from a man of his experience of the inner mysteries of racing, deserved serious consideration. He stated most emphatically that anyone who backed a horse, as most punters do, without "knowing something" was a mug—plus an adjective. Wallace, of course, paid no heed to that. I daresay he knew it already. I am sure his bookmaker did.

"Ferocious-looking customers..."

The man, however—Freeman will serve as a name for him, since by those who practise his particular calling publicity is not considered desirable—was useful to Wallace in another way. He was well-known among the racing fraternity, and as Wallace at this time was contemplating a second venture as a racing tipster—the weather was far too fine for serial writing—it struck him that Freeman's name would give a cachet to the firm.

It was, of course, public knowledge that he had been concerned in a case of doping racehorses, and the subtle suggestion, I suppose, which it was intended to convey by using his name for the firm's title was that, whenever one of his faked or doped horses was running, Freeman & Co.'s clients would receive the tip.

Wallace was sufficient of a psychologist to know that, though a man might strongly denounce such malpractices as doping or faking a horse, his robust convictions on the subject would not prevent his backing the horse if he had the tip for it.

Wallace—he was very hard up at the time—accordingly paid Freeman the sum of £250 for the privilege of running the business under his honoured name, and the business was duly started.

It was an altogether more impressive affair than our first venture in the tipping business. The firm of Freeman & Co operated from an office of its own in Regent Street, and had a clerical staff—he called opportunely, I believe, to touch Wallace for 10s., and received the appointment as a bonus—a typewriter and a telephone, and, crowning glory, a tape machine!

Wallace was sure that he had found a gold mine. Story-writing? Bah!

Freeman & Co.'s business career was brief and inglorious. The clerical staff proved unreliable, particularly, I fancy, on the book-keeping side; and if Wallace, who was, of course, responsible for supplying the "good things" for his clients, ever tipped a winner, I feel sure I should have heard the glad tidings.

How far the rapid decline and ultimate decease of Freeman & Co were due to lack of nutritive value in the tips which Edgar supplied, I do not know. At all events, the business faded out, the clerical staff vanished from our ken, and the whole depressing episode was forgotten in a spurt of high-speed serial writing.

It was recalled, however, a few months later by a frantic telephone message from the erstwhile clerical staff. He had been arrested, he said, and fined £2, and he had no money, and if he couldn't pay the fine he would have to go to prison, and what would his wife think then, and would Mr. Wallace pay the fine for him?

I inquired which of his misdemeanours had been discovered and had led to his arrest. He told me, with tears in his voice, that he had stolen a chicken!

I reported to Wallace, who, much to my surprise, said he was hanged if he would pay the fine. The clerical staff had served him a dozen low-down tricks, and he could get out of his trouble as best he might. I wondered if that were the real reason—it was unlike Wallace to be vindictive—or whether it was the pettiness of the theft of a chicken that had stirred him to contempt. I had an idea that if his late employee had only had bigger ideas and purloined a leg of beef or the Crown Jewels, Wallace would have paid the fine without demur.

Later, he came into my room and tossed a couple of one-pound notes on to my desk.

"Go round to the police court, Bob," he said, "and pay that fine for him. I once stole a pair of boots myself."

When I returned from my errand Wallace was deep in thought at his desk.

"They say I'm a criminologist, Bob," he said, "but this beats me. I can't get the man's psychology. Why the devil should he want to steal a chicken?"

I explained that it was a trussed chicken from a poulterer's shop, and that he stole it, so he had said, because he needed food.

Wallace sighed with relief.

"I wish you'd told me that sooner," he said. "I've been wondering all the afternoon why a man should want to keep a live chicken in a two-roomed flat."

Wallace's association with Freeman ended with another disillusionment. He called at the flat one day, got Edgar to cash him a cheque for £15, went off with three fivers in his pocket, and never reappeared.

His cheque did, however—marked "No effects." For years Wallace kept that cheque in one of the drawers of his desk. It was still there when we sailed last year for America. Now and then he would take it out and gaze at it sadly.

For all his self-confidence, Wallace was in reality an extremely sensitive man, and, like most sensitive men, he had his streak of vanity. His dignity—and he could be very dignified when he chose—was all too easily hurt. I do not think that, when big success came to him, he could ever quite manage to forget that he was the famous Edgar Wallace, whose name had become almost a household word, who had been caricatured in Punch as one of the personalities of the day, whose books were read from one remote corner of the world to the other.

Press cuttings concerning him—in recent years we lived in a constant shower of them—gave him immense satisfaction, provided they had something nice to say, and I am not sure that he ever reached the point, which so many authors claim to have reached, where the sight of his name in print gave him no thrill.

He liked to be recognised in public, and Press photographers, reporters and interviewers, though, as part of his rôle as a person of importance, he simulated the conventional dislike of them, can never have found him a very elusive quarry.

He was, though he did his utmost to disguise the fact, super-sensitive as to the opinions others held about him and his work, and it was as easy to hurt him with a perfectly just adverse criticism as it was to flatter him with obviously exaggerated praise. He could absorb flattery in unlimited quantities, and never reach saturation point—a weakness which, during the periods of his prosperity, must have cost him thousands of pounds. It undoubtedly led him into many ventures which, though they benefited the flatterers, brought Wallace nothing but soothing syrup and an overdraft at the bank.

His love of public recognition occasionally produced its humorous incidents. I remember once sitting in the front row of the dress circle on the first night of one of his plays at Wyndham's Theatre, and watching Wallace arrive. He entered his box with that self-complacent smile which I knew so well, and glanced round at the audience as though expecting some sign of recognition. But no one, apparently, had noticed his entrance, and there came neither round of applause nor even buzz of excitement.

The smile vanished from his face, and, knowing how disappointed he was feeling, I was tempted to make myself conspicuous by indulging in a few hearty claps. Wallace sat down—feeling very flat, I am sure—well at the back of the box, where it was almost impossible for anyone to see him, and I was afraid that the lack of a duly demonstrative reception had spoilt his evening for him.

But I should have known better. Inch by inch, as the house filled, Wallace's chair was edged forward; gradually, as he advanced, his smile returned; until at last, with a final movement of the chair, he was right in the front of the box, in full view of the audience. And just as he reached that position came the demonstration for which I knew he was waiting—the buzz of interest, the round of applause, the cheers from the gallery—and Wallace rose, bowed his acknowledgment and sat down again, smiling and satisfied.

I smiled, too, and fervently hoped that Edgar had not noticed, as I had, that not a head had been turned in his direction, and that the applause had not been intended for him at all. The audience had been welcoming Bobby Howes, who just at that moment was taking his seat in the stalls.

It was, I suppose, this streak of vanity in Wallace which led him to rhapsodise on every possible occasion over my perfections as a secretary. I was a very rapid typist—one had to be to cope successfully with Wallace working at full speed—and the fact that I held the typewriting championship of Europe gave him tremendous personal satisfaction. I was the best typist in the country, and I was his secretary. I am afraid his friends must sometimes have grown weary of hearing about "Bob" and his perfections, for Wallace rarely missed a chance of hymning my praises, and I grew resigned to his bringing visitors into my office at any odd moment and asking me to give them an exhibition of my skill on the typewriter. As a rule, on such occasions, I managed more or less to live up to the reputation which I knew he had been giving me, but once...

Wallace at that time was doing the dramatic criticism for the Morning Post, and on the first night of a new play I used to meet him at the theatre as soon as the curtain was down, take down his criticism of the play in shorthand, type it, and deliver it at the Morning Post office so that it could appear in the next morning's issue.

On one such occasion, when I was to meet him at 11 p in at Wyndham's Theatre, I spent the earlier part of the evening at a party. It was a twenty-first birthday affair, and champagne flowed freely; but, remembering my appointment with Wallace, I strictly rationed myself to a couple of glasses. Champagne, I argued, was not a drink which could be relied upon to enhance the speed and accuracy of shorthand and type-writing; it was, moreover, one which I only drank on the rare occasions when a refusal might seem churlish, and its effect on my mental and physical equilibrium was therefore practically an unknown quantity.

I arrived at the theatre, satisfied that its effect had been nil, found Wallace at the back of the stage, produced my fountain pen and prepared to be the perfect secretary.

There was the usual first-night excitement and Wallace was in one of his most genial moods. He introduced me to everybody and insisted that I should have a drink. It was a thing he rarely did. He very infrequently drank either wine, beer or spirits himself, and I never before heard him press anyone to do so. But on this occasion he was most insistent, mixed a whisky and soda for me himself—his ideas of a tot of whisky, as of most other things, were on the grandiose scale—and thrust the glass into my hand.

"Put that down, Bob," he ordered, "and then we'll get to work."

I put it down—and I believe we did get to work. I have a vague recollection of Wallace pouring out words as generously as he had poured out the whisky, and of my making a series of crazy-looking hieroglyphs on the paper as it revolved beneath my pen. Wallace knew nothing about shorthand, however, and I congratulated myself, as I left him, that the results of mixing champagne and whisky had escaped his notice.

I made my way across a surging stage, located a swirling office, seated myself at a swaying typewriter and began to transcribe my shorthand notes.

I had scarcely started when the door opened and Wallace came in; behind him was Sir Gerald du Maurier, and following behind Sir Gerald there came into the room every member of the company playing in the show, who ranged themselves round my table.

"I've just been telling everybody that you're the fastest typist in England, Bob," said Wallace. "Show them what you can do."

My heart sank and I sent an imploring glance to Wallace; but he was smiling his most complacent smile, and evidently had not realised the effects of his heavy-handed way with the tantalus, and there was nothing to be done but make as good a show as possible for the edification of my audience, so I made a tremendous effort to pull myself together and began to type.

My usual working speed on a typewriter is approximately 6,000 words an hour, but to reach that speed it is essential for the machine to be stationary and the number of keys limited.

On this occasion neither of these conditions obtained, and my speed, to say nothing of my accuracy, suffered accordingly. I typed at a rate of which most beginners having their first lesson would have been ashamed, picking out the keys with one finger on each hand, and picking at least once in every three attempts the wrong key. But it was the best I could do, and any attempt to bring more fingers into play and so speed things up a bit only involved me in hopeless chaos.

I do not know how long the ordeal lasted; it seemed an age that I sat there in an oppressive silence, punctuated now and then by the tap of a key. But I came to the end of my notes at last, took the paper from the machine and glanced round nervously at the assembled company. Sir Gerald was watching me with a quizzical smile on his face.

"Wonderful!" was his comment. "How long, Mr. Curtis, did it take you to reach that state?"

The rest of them were quick to take the cue. "Marvellous!"—"Amazing!"—"Incredible!"—"Lucky beggar!" came the chorus, and in the midst of this paean of praise I rose and prepared to go.

There are two distinct versions of my actual exit.

Mine is that I picked up my hat, said "Good night, Mr. Wallace," and went out in a perfectly natural way.

Wallace's version, which he always stuck to tenaciously afterwards, was that I set my hat on my head at a rakish angle, gave him a casual wave of the hand, and with a "Well, good night, Edgar, old cock!" strode out. But that, since I was always most punctilious about calling him "Mr. Wallace" in the presence of others, was, I am convinced, a subsequent effort of his imagination.

Wallace, when I met him the next morning, smiled.

"Find the Morning Post office all right, Bob?"

I assured him that I had.

"Did they grumble that the criticism was too short?"

"Short?"

Wallace nodded.

"There were only six lines of it."

"Is that all?" I sighed. Six lines! I had often typed an 80,000-word novel with less effort.

Thereafter, Wallace, though he never grew weary of boasting of my prowess on the typewriter, was less inclined to ask for an exhibition of my skill. As I have said, he was sensitive to a degree, especially where his work was concerned. Anyone who was prepared to praise his work was assured of a willing and attentive listener; but, like so many other authors, Wallace, even though he might have invited the criticism, really resented it if it were unfavourable.

He was inclined to take it as a personal affront if an adverse opinion were passed on something he had written, and to give the impression, though I am sure that in his own mind he was really far from having any such exaggerated idea, that any story or play from his pen was above criticism.

It was not altogether surprising. There were so many around him who were all too ready to flatter him on the slightest pretext, and to persuade him, not always from disinterested motives, that his play or story was a masterpiece, that it would have been more surprising if, with that vein of vanity running through him, he had not responded to such sympathetic treatment.

Personally, after years of intimate association with him, I was on a privileged footing in this respect. He would frequently invite my criticism of what he had written—latterly it was his invariable rule to do so and he usually listened with a good grace to what I had to say, even if it were unfavourable, and gave it serious consideration.

He never seemed to imagine, as he often did with others, that, because I thought a story had a weak point or two which might advantageously be strengthened, I was casting aspersions on his ability or "knocking" his work for the sole purpose of fault-finding. He told me more than once that I knew whether or no a story was in the true Edgar Wallace vein better than he did. Yet once, persona grata as I was, I, too, came under the shadow of his displeasure for having ventured a candid criticism.

It was in connection with a play called The Mouthpiece. Wallace gave the manuscript to me, and, with the self-satisfied smile which told me that he was confident of having written a winner, asked me to read it and tell him what I thought of it.

I read it and I told him my opinion frankly, but, I think, quite tactfully. I said that to my mind the first act dragged badly and needed speeding up if the audience were not to be bored before the first interval; that the opening lacked clearness and needed revising if the audience were to understand what it was all about; and I pointed out what struck me as a bad anti-climax in the last act. I was convinced that this play, at any rate, was not true Edgar Wallace as it stood.

To my surprise, Wallace, on this occasion, seemed very much hurt by my criticism. He disagreed with me on every point I had raised, and confidently asserted that it was the best play he had ever written and was assured of at least a year's run.

Someone, I guessed, had been administering a dose of flattery, with the result that Wallace's usually keen mind had been doped into believing that the play was what the Americans none too elegantly describe as a "wow." Wallace had already had one recent theatrical failure; I knew that a second might seriously injure his reputation in the theatrical world, and I was desperately anxious that the play should not be produced until he had at least spent some time knocking it into shape. Perhaps my anxiety ran away with my discretion. At any rate, I said that if it ran for a year, then I knew nothing about plays and would henceforth hold my peace. I prophesied a month's run for it at the most.

But Wallace would not listen, and I was undeniably unpopular. For over a week he hardly spoke to me.

The play was produced—more or less as it stood; the unanimous verdict of the Press critics was that it was a bad play, carelessly written, poorly constructed, wrongly cast and inadequately rehearsed. It ran, I believe, for a week.

I said "unanimous," but that is not strictly accurate. There was one exception to the general chorus of disapproval. A journalist on the staff of some obscure provincial newspaper—I cannot now even remember its name—wrote a most flattering notice of the play; so flattering that, when I read his encomium, I instantly suspected that he had not seen the piece at all. It was unbelievable that, had he sat through the wearisome performance, he could really have felt any genuine enthusiasm for it. He even went so far as to say outright that it was the best play Wallace had written.

That was incredible enough, but the sequel to his eulogistic outburst was even more so. I took the cutting to Wallace—his wounded feelings badly needed some balm—and, as he read it, I saw his eyes light up.

"Send this fellow a wire," he said, and proceeded to dictate a long and expensive telegram to the writer of the notice, congratulating him on being the only critic in the whole of England who had a true sense of dramatic values!

Later, when the first disappointment had worn thin, Wallace, I know, came to see that the enthusiastic provincial journalist had been wrong and the rest of the dramatic critics right.

"You were right, Bob, and I was wrong," he admitted frankly one morning soon after the play had been withdrawn. "The Mouthpiece is a bad play. But I'm writing another—I did the first act last night—and it's a sure winner."

I smiled. "I hope it will run for a year," I said.

"It will," said Wallace. "If I turn The Mouthpiece into a novel, Bob, I think I shall dedicate the book to you."

I asked him why.

"I've written a hundred and fifty novels," said Wallace, "twenty or so plays, hundreds of short stories, and thousands of articles, and they can't all be good. There are just three people in the world who have the pluck, or the sense, or both, to criticise my stuff, and you're one of them. By the way, you're coming racing with me this afternoon."

Thus was I received back into grace. Edgar was himself again. As if anxious to reassure me on that point, he backed five losers that afternoon.

Yet at the time he had strongly resented my criticism. He really hated adverse criticism from anyone and usually took it rather badly. To anybody who ventured to suggest an alteration in one of his plays or stories he would write stinging letters or telegrams refusing to make the alterations, would subsequently rewrite them in less truculent vein, and as often as not close the matter by agreeing to make the suggested changes.