RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

For other illustrations, see Appendix III.

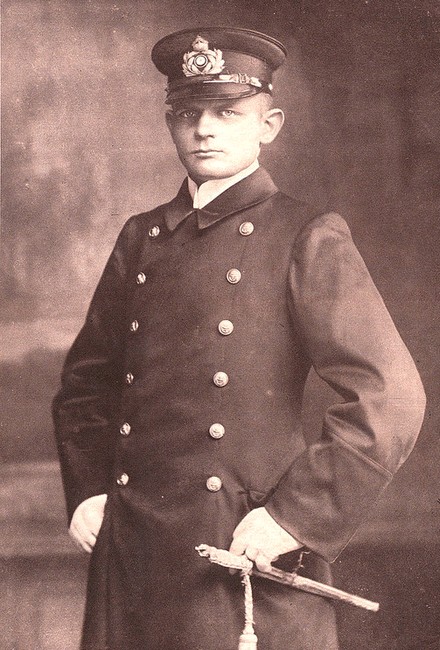

Karl Lody in Naval Uniform.

IN 1918, the Glagow Sunday Post commissioned Edgar Wallace to write, under the house-name "John Anstruther," a series of articles about the exploits of the then notorious German spy Karl Lody in Great Britain. These articles are gathered here for the first time in book form and published as an RGL first edition. Illustations from the Glasgow Sunday Post and other sources have been added.

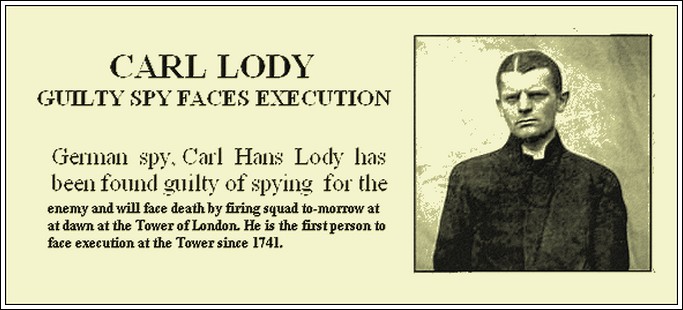

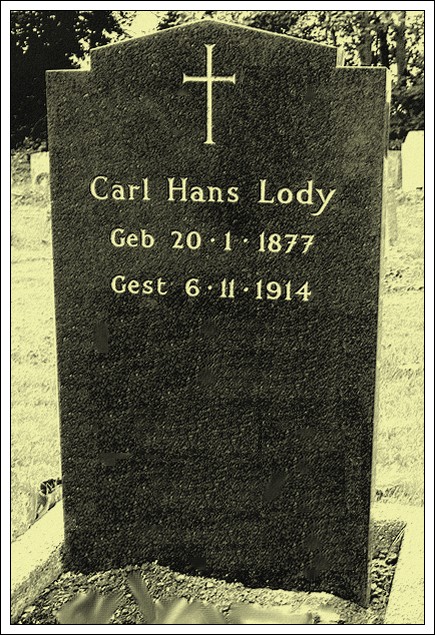

CARL HANS LODY, alias Charles A. Inglis (20 January 1877-6 November 1914; name occasionally given as Karl Hans Lody), was a reserve officer of the Imperial German Navy who spied in the United Kingdom in the first few months of the First World War.

He grew up in Nordhausen in central Germany and was orphaned at an early age. After embarking on a nautical career at the age of 16, he served briefly in the Imperial German Navy at the start of the 20th century. His ill health forced him to abandon a naval career, but he remained in the naval reserve. He joined the Hamburg America Line to work as a tour guide. While escorting a party of tourists, he met and married a German-American woman, but the marriage broke down after only a few months. His wife divorced him and he returned to Berlin.

In May 1914, two months before war broke out, Lody was approached by German naval intelligence officials. He agreed to their proposal to employ him as a peacetime spy in southern France, but the outbreak of the First World War on 28 July 1914 resulted in a change of plans. In late August, he was sent to the United Kingdom with orders to spy on the Royal Navy. He posed as an American—he could speak English fluently, with an American accent—using a genuine U.S. passport purloined from an American citizen in Germany. Over the course of a month, Lody travelled around Edinburgh and the Firth of Forth observing naval movements and coastal defences. By the end of September 1914, he was becoming increasingly worried for his safety as a rising spy panic in Britain led to foreigners coming under suspicion. He travelled to Ireland, where he intended to keep a low profile until he could make his escape from the UK.

Karl Lody's American Passport

Lody had been given no training in espionage before embarking on his mission and within only a few days of arriving he was detected by the British authorities. His un-coded communications were detected by British censors when he sent his first reports to an address in Stockholm that the British knew was a postbox for German agents. The British counter-espionage agency MI5, then known as MO5(g), allowed him to continue his activities in the hope of finding out more information about the German spy network. His first two messages were allowed to reach the Germans but later messages were stopped, as they contained sensitive military information. At the start of October 1914, concern over the increasingly sensitive nature of his messages prompted MO5(g) to order Lody's arrest. He had left a trail of clues that enabled the police to track him to a hotel in Killarney, Ireland, in less than a day.

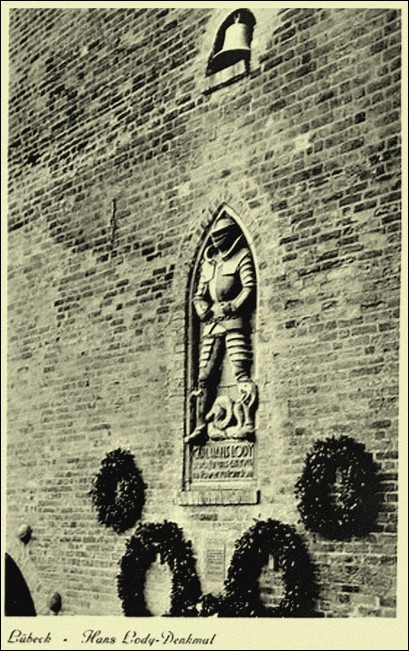

Lody was put on public trial—the only one held for a German spy captured in the UK in either World War—before a military court in London at the end of October. He did not attempt to deny that he was a German spy. His bearing in court was widely praised as forthright and courageous by the British press and even by the police and MO5(g) officers who had tracked him down. He was convicted and sentenced to death after a three-day hearing. Four days later, on 6 November 1914, Lody was shot at dawn by a firing squad at the Tower of London in the first execution there in 167 years. His body was buried in an unmarked grave in East London. When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, it declared him a national hero. Lody became the subject of memorials, namesake for a destroyer ship, eulogies and commemorations in Germany before and during the Second World War. Wikipedia.

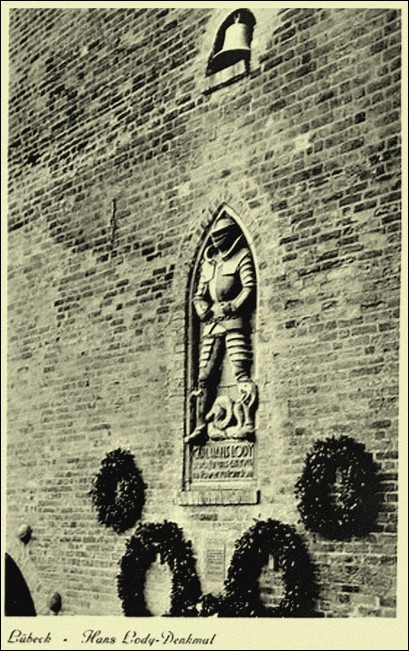

Postcard of Karl Lody memorial erected in Lübeck by Nazis in 1934

THIS edition of Karl Lody—Germany's Great Spy

includes three appendices.

The first contains a synopsis of the case, includings a chronology of Lody's activities in Great Britain and details of his trial and execution.

The second consists of two letters that Lody wrote before his death: one to the Commanding Officer of the guards in charge of his custody, and one to his relatives in Stuttgart.

The contents of these appendices were obtained from the web site British Military & Criminal History 1900-1990, and are used with the permission of the copyright-holder, Stephen Stratford. — R.G., July 2016.

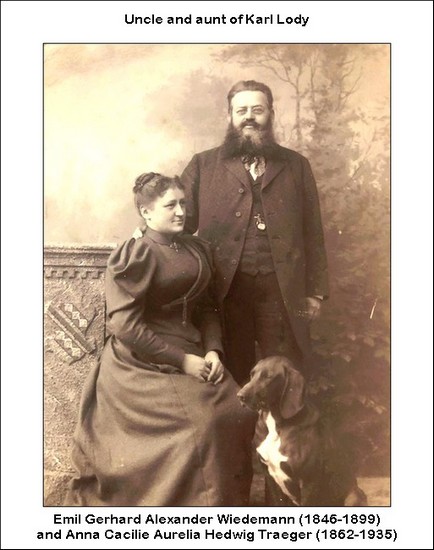

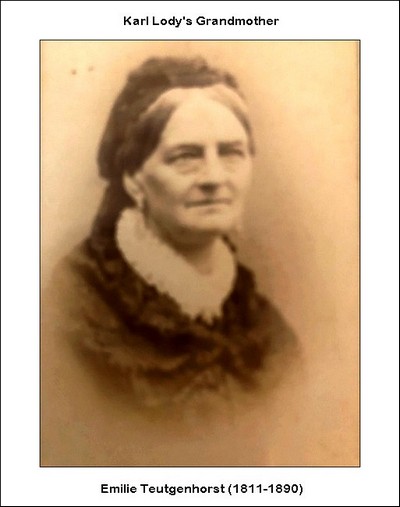

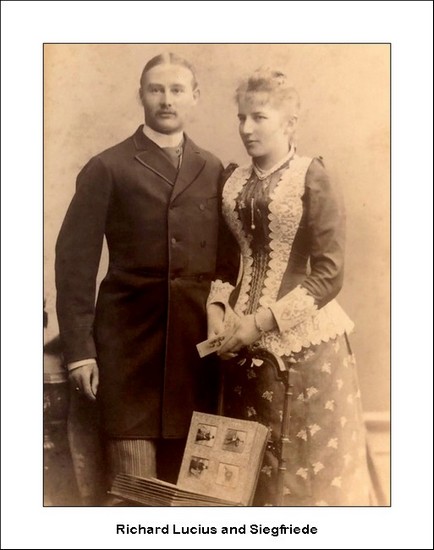

The third appendix offers an outline of Lody's ancestry and contains documentary material, including photographs, donated by Martina Jorden, a descendant of the Lody family.

IN 1912 a group of German burghermeisters came on a love feast to London, and were accommodated at a hotel on the Thames Embankment. They came to carry a message of peace and goodwill to the noble British nation, upon whose indecent gullibility the sun never sets, and they carried their message through the medium of sweet champagne and food which was mostly fried in fat.

It was a great and joyous occasion, and the German flag flew from one of the two flagstaffs of the hotel, and for a few days London was filled with a crowd of men strangely garbed in Alpine hats with little feathers sticking up from the hatbands, and with primly dressed German women. The visit of the burghermeisters passed without notice by the majority of the London public, who require something with a procession in it to interest them. But those whose business is everybody's business, the press and the police, were impressed by the fact that there were more Germans in London than the occasion seemed to warrant.

On bright wormer morning a little queue of men and women undoubtedly of German origin, trailed through the Tower of London, guide-book in hand, behind a young man, who explained clearly and accurately without referring to any guidebook, the various objects of interest on either hand. Traitor's Gate, the White Tower, the Regalia House, the Place of Execution, Beauchamp Tower, all these came under review.

"I remembered when I saw him again," said a sergeant of Beefeaters. "He came half a dozen times to my knowledge, and he was always in charge of a party of German tourists. He used to come to me and say,'Well, are the dungeons open to-day?' We called him the Dungeon German because he always wanted to see them.

"I once took him round the quarters where visitors never go. There was nothing secret about them, and nothing interesting but I remember as well as though it were yesterday his saying, 'What's that place?' I answered, 'That's the miniature rifle range.' 'I'd like to have a look at it,' he said, but I told him that that was only to be seen by permission of the officer commanding the 2d Scots Guards, who were doing duty at the Tower. The next time he came with another party of tourists he asked me, 'What about the rifle range? I'm going to have a look at it one of these days.' And he did. It was in the rifle range that they shot him. I saw him marched there in the dark of a November morning and heard the crack of the rifles."

In this way did Lieutenant Lody alias Inglis pay the penalty for espionage, and with his death went out something more than a human life, namely, a shattered German tradition.

Lody was the best spy that the German Naval Intelligence ever sent to Britain. He had served in the navy, and had achieved the rank of lieutenant-kaptan, but his active naval work was of less consequence than the excellent work he did in the bureaus.

A man of considerable attainments, he had spent some period of his boyhood in England, and spoke our language without a trace of accent. He was a mine of information on the subject of British naval equipment, and was one of the most industrious of that little gang whose headquarters in the days before the war were in the Rue Leopold at Ostend.

There are many facts which must writers on the German espionage system overlook, and not the least of these is this:—The' most successful results of the system were secured, not in the days of war, but in the three years before the war. It was in many ways a perfect system, and certainly it repaid the German Treasury for the vast expenditure of time and money which was made on it.

The second fact, and this is preliminary to a recountal of the amazing events which preceded the war, is that so far as Britain was concerned the whole elaborate scheme of espionage for war purposes which the German Government erected came crashing to the ground just as soon as the war test was applied.

Lody's capture and death struck Von Tirpitz a paralysing blow. The news of his arrest was brought to the German Admiralty in September, anal Tirpitz is said to have remarked, "There is a counter-espionage system in Britain. I did not believe it. All our plans are based on this illusion. If Lody failed, who can succeed?"

So, to understand the story of Lody it is necessary to appreciate fully all that Lody stood for, all that had gone before to prepare his way, and exactly the part he had played in the establishment of the Ostend gang. For it was in Ostend that the most of the devilry of the war was planned; in Ostend that the way was made clear not only for those events which disgraced the name of Germany in her subsequent occupation of Belgium, but for that super-murder of the war, the sinking of the Lusitania, and it can be said in truth that in this tragic folly we see the dead hand of Lody as clearly as any.

We see also the hand of a wretched British sailor, a petty officer of the Royal Navy, who is serving a long sentence in Portland Gaol. Many names have been given as the leader and planner of Germany's secret campaign against Britain. Von Capelle, Von Tirpitz, Captain von Muller, and a host of minor officers of the German Admiralty, but to omit the name of Lody and the man called variously Heffler and Schmidt would be to miss the essential facts.

Lody was trained for secret service work and the greater part of his service was in that branch. With characteristic German "thoroughness" he studied the surface of British politics, mastered not only the language but the idioms of the language. He was later to set the course which candidates for honours in espionage must pass before they were admitted to the probationary stages of the service. Examinations were held at Kiel, and test papers were set to candidates just as they are set for students in our own country. Two of these papers (in type script) were found in the office of Wolff von Igel when his office at 60 Wall Street was raided by Joseph A. Baker, of the American Department of Justice on the morning of April 19, 1916. Some of the questions are curiously reminiscent of Lody's activities in pre-war days, and were obviously set by him.

1. Give the train times between London and (a) Plymouth, (b) Chatham, (c) Edinburgh, (d) Portsmouth, (e) Falmouth, (f) Greenock.

2. Name the stations at which a journey from (a) London to Cardiff can be broken so that the journey can he resumed to Manchester; (b) Edinburgh to London, so that the journey may be resumed to Harwich.

3. Give routes to and from the following towns, avoiding London. Liverpool to Chatham, Carlisle to Dover, Plymouth to Dover, Plymouth to Southampton, Portsmouth to Edinburgh.

4. Mark strategical points on the following routes, taking care to observe where the routes cross rivers. London to Derby, Liverpool, Harwich, Hull, Edinburgh, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Glasgow, Dover, Newhaven.

5. Give a list of 150 common English names.

6. Give particulars of 20 small seaport towns in England, Scotland, or Wales, with the names of Mayor, prominent tradesmen, and shops, the names of their newspapers, the principal streets, and the names of advertisers.

It will be noticed by the curious that all these questions relate to naval affairs. All the places mentioned have some relation to the navy, for, although such cities as Newcastle are not specifically mentioned, they lie on one or the other of the routes specified. There is no mention of Aldershot, or Borden Camp, or Salisbury Plain. And this brings us to one of the reasons why the German espionage system broke down. It was organised to deal exclusively with our navy, and never took into account the fact that Britain might develop into a great military nation. For this reason, throughout the war the German General Staff was completely ignorant of our military preparations. The men Lody trained went nosing about the Firth of Forth (and met their deaths in consequence) and did not see the Tank Corps growing under their eyes.

They busied themselves about our new naval construction entirely, and to the very end Hindenburg had no exact knowledge on military strength as he had of the French, though he knew we had built three cruisers which were utterly worthless, land that the guns on the —— were a failure.

All the German's plans against Britain were naval plans, and eight years before the war started, when Lody was a boy at school, the office in the Rue Leopold was established. Germany at that time was working strongly to a definite end, and curiously enough, she was enlisting British support. The crux of any European war, whether it was naval or military, was Belgium. The Belgian Coast for her ships, the Belgian frontiers for the attack which was to be planned upon France, were vitally necessary or her, and so she set herself the task of putting Belgium in the wrong, particularly with the British people.

As I said before, it is necessary to know what went before to understand the part which Lody played, and I am certainly describing a period in the story of German cunning in which the name of Lody does not occur. It may have escaped the recollection of the people of Scotland that ten or twelve years ago Belgium was a most unpopular country so far as the British were concerned, and its unpopularity was brought about by a systematic agitation against the administration of the Belgian Congo. It was said, and probably with some truth, that Belgian officials in darkest Africa had committed terrible atrocities upon the Congo natives. Harrowing stories were published in Britain, and these were supported by despatches from the British Consul at Boma, whose accounts, if anything, were a trifles more disturbing than those sent in by the missionaries.

I am not going into the truth or the untruth of these statements. In 1906 I myself went to the Congo to investigate these charges, and I confess that I saw very little to substantiate the charge of misgovernment which was being so freely made. That, however, was by the way. The point to remember is—that the man who was the prime mover in this agitation against Belgium was that horrible pervert, Roger Casement, who was hanged in London for acts of treason, and who certainly deserved hanging for the beastliness of his private life. It was Casement, already in the pay of Germany, already working heart and soul for the land of "kultur," who brought about a condition of strain between the two countries, and it is certain that if war had broken out then the British people would never have consented to an army going to the rescue of Belgium or even of declaring war on her behalf.

I regard that agitation as the first and most successful work that the Ostend gang has to its credit, but somehow the agitation hung fire. The British newspaper editor is a pretty difficult man to fool. I admit that I myself was fooled, and went out to Africa full of beautiful thoughts of rescuing the downtrodden native from his Belgian oppressor, but there were people who begun to smell a rat. They saw the hand of Germany already reaching out for a slice of the Congo to be added to their Western African possessions of Togoland and the Cameroons, and "Belgian Atrocity Stock" began to fall. It was about this time that the Ostend office was strengthened by a naval commander, who switched the activities of the gang to a new direction, and when Lody had passed out after his sea service into the Intelligence Department he was sent down to Ostend to organise the British end. He made frequent visits to London—sometimes under his own name, sometimes in the name of Inglis, sometimes in the name of Franks. He stayed at the best hotels in London, Edinburgh. Belfast, Plymouth, and Portsmouth. He got acquainted with a number of naval officers, and was invited to dinner on board several of the ships. It is said that he came to England on one occasion as a member of a naval staff on the visit of a German warship to this country, but that is not true. So far as is known he was never in uniform, nor did he ever stay except on very few occasions in his own name.

He was a man of pleasant address, full of good stories, childlike and bland in his innocence of naval matters except, as we shall see, when he was dealing with the lower deck; and he a as usually accompanied by a novitiate in the art of espionage, to whom he showed the ropes. On some occasions he was accompanied by a beautiful woman, whom he introduced as his sister, but who I have reason to believe was the wife of the London correspondent of a well known German newspaper. He was not always fortunate in his visits. In 1913 one of his friends, whom he had left behind at Portsmouth, was arrested on a charge of sketching naval works and, though he pleaded that he could buy picture postcards of the forts he was sketching for a penny, he was sentenced to a long term of imprisonment, and was still in Winchester gaol when the war broke out.

There are certain aspects of Lody's activities which it is rather painful to write about, the more so as one of his victims has recently been released from prison and is trying to live down his past, but since at least two of his successful exploits are more or less public property they may be described in greater detail than has as yet appeared.

The prize for which all secret services strive is the code books of Government Departments. It would not be inapt to describe any secret service as a system for securing a possible enemy's code books. For wore than half of war is words. Every year hundreds of thousands of pounds are spent in creating or protecting codes, the most common of which is the double or treble code in use in Government offices. This is by far the most elaborate, and consists of groups of five figures which indicate a word, which in turn indicates another word. Men who decode the messages do not understand them. A telegram is received which contains the figures:—01749, 21431, 35914.

The decoder unlocks the first code book, and discovers that "01749" means "Delhi," "21431" means "standard," and "35914" means "personal." He sends the words "Delhi, standard, personal" to another department, and another decoder turns up the words in No. 2 Code Book, and finds they indicate three new a words, "Brown, golden, apple." This second decoding goes to the chief of the department, probably a permanent Under-Secretary of State, who has the final and the most inaccessible of the three code books, and he translates the three meaningless words into:—"Russia has signed-new treaty-with Germany."

To secure the triple code is almost an impossibility. It is much too carefully guarded. Abroad, the Ambassador or the Foreign Secretary practically sleeps with it under their pillows. But there is a naval code which is not so complicated. It is a single code, and if you get one book you get the whole system. On board ship it is kept under lock and key in the captain's cabin, and reposes in a steel box the bottom of which is perforated with holes and weighted with lead. In the event of the ship sinking or being in danger of falling into an enemy's hands the box is thrown overboard and because of its weight and its perforations it immediately sinks to the bottom. To make aura of its sinking the captain of a British warship has before jumped overboard with his precious box in his hand and has gone down with it. Because of its secret nature it very seldom passes into other hands than the chief officer of the ship or the chief yeoman of signals, but on rare occasions it been been possible for unauthorised persons to handle it.

Lody had made a special study of the personnel of the navy. His job was to get into touch with men who were in any way in trouble or who had particular grievances, and this he did in a manner which was characteristically German. At places like Sheerness, Chatham, Portsmouth, and Devonport he opened little loan offices and inserted modest advertisements in the local newspapers. "Special terms for Service men," said the advertisement; "moderate interest and generous treatment." It added the pious warning not to "get into the hands of money-lending sharks."

Now the Service authorities strongly discountenance men mortgaging their pay, and under certain circumstances will always make an advance to a man who is hard up, but few sailors or soldiers care to face the forest of red tape which encompasses a loan, and still less do they like their embarrassments to be known to their officers.

In all naval towns moneylenders flourish. This is more the case in naval than in military centres, because for some reason the moneylending fraternity fight shy of soldiers. And Lody's loan offices got hold of some excellent clients. Lody's name never appeared in any of these transactions, nor is his name to be found in the list of registered moneylenders, which is kept at Somerset House. He had his tools, mainly aliens of dubious antecedents, and was content to set the businesses going and to receive reports from his agents.

In this way he came to know of men who were in difficulties. Men who were being sued for money, men who had been involved in domestic troubles, others who had incurred particular misfortunes which embittered them, their dossiers came to him either in Ostend or in London, and he would sometimes visit a port and interview one or the other of his debtors.

True to the advertisement, his terms were generous—to the right kind of man. The superior type of artificer petty officer could always be obliged with an extra loan, and all the time he wanted to repay it. Lolly posed as an inquiry agent of the Loan Company, and in that capacity would call upon his victim at his house after dark. Some of the men recognised him as the young gentleman they had seen in the company of officers on the quarter-deck and drew their own conclusions, which were not flattering to the solvency of the officers concerned. They found the "visiting inspector" a most agreeable young man, who was not superior to a friendly glass at the nearest bar and, above all, he was mightily sympathetic to the lower deck point of view.

One of his stories was that he had served in the American Navy, and he made this the excuse for his interest in naval affairs. He would discuss over a glass or two the wonderful gunsight which had been recently introduced by the U.S. Naval Board, describing this sight in language which left no doubt in his hearer's mind that he understood all that there was to be known of the technical side. He had no difficulty in getting his audience to talk. In a spirit of emulation the British sailor might in all innocence boast of some improvement which had been introduced into his ship.

But the big task which Lody set himself remained—the securing of the code book. It was not a chance which would occur very often, but it occurred once or twice and he seized it.

The dupe in the case quoted was a petty officer, yeoman of signals. Lody's confederate, Weinthal, got to know the man and advanced him money. No mention was made about the services which the sailor would be expected to render in return, and the acquaintance was of a more convivial nature than was ordinarily the case. Lody himself did not appear in the matter. Although he was in Gravesend when Weinthal and his naval friend were meeting, he himself was not one of the party which used to gather in the private bar of a local public-house. After the friendship had been given time to ripen, it was suggested that the sailor should get into mufti and accompany Weinthal to Ostend on a joy trip. The jaunt came off according to plan and the petty officer had the time of his life in that gay town. The best hotel was not too good for him; wines of the rarest were poured out for his comfort, and the feminine society was, if not select, at least amusing.

It was here that he met Lody for the first time, "a young gentleman in evening dress; I think he was English." The attention and companionship of an educated man was flattering to the petty officer, and Lody began to tell a story about bets. According to this story, Lody had bet a ma £1000 that he could produce a copy of the latent naval code. The bet was apparently in answer to a challenge, according to Lody, and he said laughingly. "I am afraid I have as good as lost my bet, though I wish it had been to somebody else."

The petty officer, full of good wine and bubbling over with good spirits literally and figuratively, was interested, discussed the difficulties of getting the book, and said that he knew how one could be got.

"I tell you what I'll do then," said the young English gentleman. "If you bring me the code I will pay my winnings to you."

They touched on the matter lightly the next evening when they met at the Kursall, and when the sailor left by the night boat, his leave expiring the next morning, he carried away with him a dream of easy money.

It is not for us to judge the man whether he believed or did not believe this story. His account of the affair was not accepted at the subsequent proceedings. There was a week or two of preparation. The book was kept in the captain's cabin, and there were very few opportunities for even entering the cabin, and the captain's servant was always hanging about.

At last the fatal day arrived when the code book could be extracted. The thief knew that the loss of the book would remain undetected for a few days and, communicating with Lloyd's agent, he secured leave and prepared to leave for Ostend on the following morning. Lody's intentions evidently were to make a copy of the book and return it by the petty officer. It was not in his interests that its loss should be discovered, for a variety of reasons, the most important of which was that when a code book is lost a new code is immediately printed and issued. He brought to Ostend a staff of photographers and, in one of the biggest hotels on the Plage, set up his cameras and lights in a special suite which he reserved for the occasion.

The book was to be photographed page by page, returned to the petty officer the same night, and it was intended that the sailor should arrive back on his ship on the following morning, which was Sunday. We know that Lody was at the bottom of this, because it was he who engaged the rooms and made the arrangements for receiving the sailor.

On the Saturday morning at eleven o'clock, ten minutes before the Ostend boat was due to sail, the petty officer came down the quay and passed across the gangway, showing his ticket to an official at the gangway head. Just as he was turning to go up to the promenade deck a hand fell on his shoulder, and he turned to face a stranger.

"What is that parcel you have got in your pocket?" said the police officer.

"A book," said the other.

"What kind of book?"

"What's that to do with you?" asked the sailor.

"I am a police officer from Scotland Yard," said the stranger, "and I shall take you into custody on a charge of stealing a code book from His Majesty's Ship X."

Karl Lody

LODY and his associates and particularly his predecessors, were all rewarded for the easy-going attitude of the British Government in all its relationships with Germany. Until the first Dreadnought was built it was the practice to allow the German Naval Attache almost unrestricted access to our naval dockyards, and even four years before the war when I was discussing with the German Naval Attache a new method of transmitting topographical information by telegraph by a system on which I had spent a great deal of time and money he was able to inform me that the British Admiralty had already tried a plan analogous to my system and that it had proved a failure. Carlton House Terrace knew everything connected with the navy. They had blue prints of every ship we launched up to, but not including, the King Edward VII. It was just about when this ship took the water that the Naval Intelligence at Berlin was organised, and produced such men as Lody.

I described last week the failure of the Department to obtain a copy of the naval code. The man who was arrested on the Ostend boat was brought to trial and sentenced to a long term of penal servitude, but before his trial had begun the German Secret Service had succeeded elsewhere. Lody's net was wide spread. The ramifications of his system were far-reaching.

In the few years immediately preceding the war Lody was a busy man. He was in Portsmouth at the time when the King reviewed the fleet, and was in Boulogne when a French submarine was sunk by the cross-Channel steamer, seeking information regarding the construction of the French boat and the system employed to salvage her. And all the time between his more secret missions he was conducting little parties of tourists through England, Scotland and Ireland.

There are several views taken as to his activities. One is that he was a mere agent of a "master any" (whose identity nobody seem, quite certain about, for several names have been given to me.) There is another view that his work was strictly limited to the camouflage tourist trips, and that he really was a fairly inoffensive person. There are high authorities, not immediately associated with Naval or Military Intelligence, who pooh-pooh any suggestion that he was any more than a very ordinary and commonplace naval officer engaged in espionage work for the sheer love of it. This is not the view which is taken by the Belgian Secret Police, who had perhaps more real hard work in countering the machinations of the Lody gang than any other police force in Europe. It is, curiously enough, largely from the Belgian records that we are able to get Lody into perspective.

In 1911-1912 the German Government, which really consisted of four men—the Kaiser, Bethmann Hollweg, Von Jagow and Von Tirpitz—decided upon war and agreed that it was extremely unlikely that Britain would remain out of it. I am not, of course, suggesting that these four were the only people concerned in the decision—it is a fact that outside of the governing circle there was a strong party, under the leadership of the Crown Prince, which was exercising a very powerful influence upon the direction of affairs; but we can say that the dates given mark the beginning of active preparation. Lody had already become a person of some importance. He was given instant admission to the bureaux of Von Tirpitz and his Chief of Staff. This fact did not pass outside the notice of the trusted agents of the British Government, who by now were taking an unusual interest in all that happened at the Headquarters of the German Naval Staff. But to know that a constant caller was a smart, spruce young naval officer named Lody was one thing and to identify him with the quiet civilian who was known to the attendants on the Dover-London Pullman as "Mr. Inglis" was another. Tirpitz had agreed to the money-lending firms being established, but naturally this innovation did not exhaust the necessities of the case.

Great Britain was to be an immense [illegible words] detected having as its object the securing of information about the British Army. I insist upon this fact because, as I explained last week, the work of the German bureaux is best understood in the light of the knowledge that the Kaiser looked upon the British Army as "contemptible," years before he issued his famous of infamous Order of the Day.

One morning in May, 1912, a young man presented himself at the office of a coal factor in Cardiff and presented a letter of introduction from a Hamburg shipper. He described himself as the son of an English father and German mother, and was supposed to have come from the Bismarck Islands, in the Southern Pacific. The coal factor did a very big shipping business, particularly with Australia and the Pacific Islands, and he welcomed the the advent of the newcomer, who, with his knowledge of local conditions, would be an acquisition to the staff. The man, who gave his name as Muller, was given a position in the export office at a salary of £2 a week. It was the sum offered and accepted without demur. In this particular case, Muller disappeared a week before war was declared, and has not been seen since.

Almost at the same time another coal merchant in Wales received an offer of service from a young Dane, but refused it, as the firm had an important Government contract, and made it a practice not to employ foreigners of any nationality. The "Dane" applied elsewhere and got a job not, curiously enough, with a coal factor, but with a haulage contractor. Throughout Wales about this time there was an epidemic of Germans, Swiss, Swedes, Danes and Dutchmen. They took jobs as engineers, electricians, clerks and even motor lorry drivers, whilst the big hotels and dining-rooms where the better class mining officials were to be found in their leisure moments were, in the language of one who noticed this strange phenomenon, "simply stiff with square heads."

Then there appeared in South Wales a little party of inquiring German railway officials who had been sent over to study the superior coal-transporting system of the British. They pestered local officials for information, studied the problems of haulage, gradients, trucks, loading and unloading and the system of labelling and forwarding coal trucks to their destination. Nobody seems to have recognised the hand of Lody in this business. Yet Lody was undoubtedly in Cardiff when this passion for information was being gratified. He booked rooms with a Mrs Rogers as "Arthur Davis" and made frequent visits to the coal centres. He was, in fact, organising the emigration inquirers.

An official of Cook's Travel Agency who happened to be at Bristol on his holidays was walking up and down the station platform waiting for the arrival of a friend from Weston-super-Mare, when his attention was attracted to a well-dressed man wearing glasses. His face was familiar and, walking up to him, he asked—

"Isn't your name Inglis?"

Lody, for he it was, hesitated then replied, "Yes."

"I thought I recognised you. What are you doing down here? You haven't brought tourists so far west as this?"

Again Lody hesitated.

"No," he said, "I have an aunt living at Cardiff and I have been on a visit to her."

The agency man thought no more about it until a man well known in the coal trade came up and joined Lody, addressing him as "Davis." Cook's man thought he must be mistaken and that the word he had heard was "David," a Christian name, but just before the London train came in Lody walked up to him.

"You heard Mr. X—— call me 'Davis?'" he asked. "Well, I didn't till you before, but down this way I am called by aunt's name. I am giving up the tourist business, and am taking up coal shipping."

The other man took no further notice of this incident, and dismissed it from his mind until a few months later he found Lody calmly conducting a party of tourists through London as though the coal trade had no existence.

What was Lody doing? What was his business in Wales?

We discovered in 1913. The British Secret Service began to hear rumours, and set inquiries afoot. One of Lody's agents was a little tobacconist, and was a man of German antecedents. He was also a very crude sort of fellow, and lacked the finesse which was Lody's strong point. One day he pressed too closely a number of inquiries which hitherto he had pursued with exemplary caution.

The man to whom the inquiries were addressed informed the police that there was somebody who offered to give him a sovereign if he would give him the exact quantity of coal stored at the dockyard (this occurred in a naval port), and the police very promptly arrested the tobacconist and charged him under the Official Secrets Act.

That was really the first warning the authorities received that there was anything "doing" in Wales, and they grew alert. But by this time the operations of the gang were in full swing. Lody in his London office was receiving the very fullest information as to the number of miners employed, the amount of coal which was going to H. M. ships, the quantities of coal which were being stored at our great coaling stations abroad, and particularly at Gibraltar and Malta and, what was more important, he was trying to interfere in the control of the great labour organisations which have shown such power in Wales.

"To paralyse the fleet in the event of War"—these were his instructions and what could so effectively destroy the power of the Navy as the holding up of coal.

It is said that Germany contemplated war in 1913 and that something went wrong with her war-works and brought about the postponement of the outbreak. All the evidence we have supports this view. The feverish activity of German agents in Wales reached its most violent phase in the spring of that year and it was about this time when Lody was concerned in the experiments which were to have so alarming an expression during the war—piloting as he did, in defiance of all the laws which govern the intercourse of nations in peace time, the first Zeppelin airship which ever crossed our shores.

In June 1913, Lody was in London, staying at a boarding-house in Gower Street, a boarding house at which lived a number of girls from a revue company which was playing in London just then. He was a polite and gallant man and one of the girls, who spoke French and German, used to dine with him regularly. She was telling him one evening that she was going to a party "after the show" that night.

"What sort of people do you meet?" he asked.

"All sorts," she replied.

"Do you ever meet naval officers?"

Now in these days neither naval nor military officers were to be met in uniform on leave and except when they were on duty or dining at mess they wore mufti and the girl was surprised by the question.

"I suppose I do, but I never ask them questions," she said. "You cannot tell officers from other types of people."

"Well, why don't you find out and help me?" he said. "I can give you a liberal commission."

He told her he was a traveller in coal and had had a tip that the stocks in the dockyards were low. He wanted to know whether this was so, so that he could offer quantities to the local authorities.

The girl believed the story. It did not sound like spying. If she had been asked to ascertain whether the guns of the ships were short of shells or the forts short of guns she would have known at once that there was something unlawful in the inquiry and would have been suspicious. But coal was so innocent, though if she had given the matter thought she would have known that coal is as important as cordite.

"I'll find out," she promised and, accordingly, when she arrived at the party, she asked her hostess, a young actress who was giving the feast, whether there were any naval officers present. There were two—a lieutenant-commander of a destroyer and a lieutenant from a battleship. She was introduced to them and, leading up to the subject by pleading an artlessness (which was quite justified) in naval affairs, she got on to the important topic, and found that at one naval station there "had been talk" about coal stocks running low owing to a strike in the coalfields.

The man from the battleship was more reticent and less informative. He was vague and unsatisfactory, giving laughing but evasive answers to the questions with which the girl plied him.

However, the news the girl was able to bring to Lody, whom she found sitting up in the boarding house drawing-room awaiting her return, was apparently satisfactory, for he gave her, to her amazement, tens pounds. A week later he asked her whether she was going to another party soon and, being answered in the affirmative, he asked her to discover whether there were large stocks of oil in the country available for the navy. This time she was suspicious. She could not understand that a man could be equally interested in coal and oil, though in this she was, of course, wrong. The two commodities are associated. Anyway, she declined to do his sleuth work and later, when he switched back his interest to coal and nothing but coal, she told him plainly that "it wasn't her line," and that he had better conduct his inquiries himself or get somebody else to make them for him. In that same period Lody was frequently absent from London. He went often to Cardiff and was an occasional visitor to Birmingham. He also went to Oxford with a party of students from Bonn.

Lody all this time was planning a great "hold up" of coal and every German shipping house in the world was in the plot. Vessels were being chartered all over the world to convey cargoes of coal from Wales to the ends of the earth. German shippers were buying not only all the available stocks, but a big syndicate, on the board of which the Hamburg-America Line was represented, actually bought one mine, and opened negotiations for another.

Lody himself was not a rich man, and on his death his property and personal effects is Germany realised leas than £500, but he undoubtedly had the disbursement of large sums. Much of this came through neutral bankers. No account in his name was discovered when the Deutsche Bank came to be wound up. The great sums he handled were usually earmarked for some special purpose, so that even if he had been the sort of man to whom "pickings" came naturally, and we have no reason to suppose that he was anything but honest in his dealings with his Government, he had few opportunities for enriching himself at his country's expense.

He travelled second class, or third class, he stayed at the least expensive hotels and boarding houses, he spent very little money upon himself, except that he was always well dressed, and he had few amusements. The men who "planked down" the money were the representatives of the German merchant princes who came to England, Wales and Scotlaad to carry out what were virtually Lody's orders.

Lody was simply indefatigable. His diary, published in one of the German newspapers, showed that he was at Rosyth, when the new docks were in course of creation, on the afternoon of one day, that he was in Newcastle the same evening, in London the next morning, at Ostend in the afternoon and slept the night in Germany!

Another entry shows him at Cardiff on a Sunday, at Ostend on the Monday morning, and sleeping in London the same night. There can be no doubt at all that, had the German Government kept to its original time-table this Britain of ours would have experienced some unpleasant shocks. It is stated that if war had occurred in 1913 the coaling arrangements for the Home Fleet would have broken down absolutely and that, thanks to the arrangements which Lody made, there would have been sufficient coal on the water—i.e. in specially chartered colliers—to coal the whole of the German fleet if it happened to have been out.

And it was Lody's scheme from beginning to end. His diaries, his letters, and such memoranda as the German Admiralty have released, prove that something more than a commonplace spy was swept out of life when Lody faced a firing party—it was a master mind, and had he been able to make his way back to Germany, and if—and this is the biggest of the "ifs"—the jealousy of the Naval Staff had not kept him down, he might have taken Von Tirpitz's place, and have given this country more trouble than either Tirpitz or Von Capelle or Von Scheer caused us.

It was because the German was the worst psychologist on earth, with a passion for employing square pegs in round holes, that Lody footled away his life on trumpery jobs which the meanest intelligence in the German navy could have accomplished as well as he, and probably better. When the Kaiser weakened on war in 1913, all the good work which Lody had done fell to pieces and he never was able to restore it to its old perfection. Here is his boast, in his own words, uttered in the first days of November, 1914:—

"Espionage is childish. As though it mattered whether any particular ship carried six guns or twenty, if you had not information which would enable you to judge the fighting value of those guns. All the good work was done last year. Our labours this year were futile and valueless. Last year we might have, and would have, paralysed you, but we missed our connections."

If Lody's "connections" had not missed, there would have been a coal famine in the winter of 1913, beyond any we have experienced. The German attack through Belgium had, as its objects, the seizure of the coalfields to the North of France. These would have removed once source of supply. Lody intended to strangle the other. The police worked frantically to get the strength of the organisation. Man after man, as any reader will remember, was arrested for "coal espionage" in the naval ports, but though the best brains in the two Intelligence Departments were working day and night, and were backed by the smartest men at Scotland Yard, the threads remained hidden until they revealed themselves after the war broke out.

Where, now, are the men whom Lody met in the rooms above the little newspaper shop?

Where are those obliging clerks who checked the output of every mine!

Where are the unobtrusive passengers who jotted down from the loaded trucks the station to which they were consigned?

It is said in Germany that no ship sailed out of Cardiff or Avonmouth but was checked out in Lody's private ledger.

And the most remarkable aspect of this enterprise of his is that all the time he was organising and travelling and filling in spare hours with "tourist" work he was preparing and elaborating a plan for the invasion of Britain, a plan which he had first prepared when he was little more than a boy, and which, had the German Government possessed the requisite courage and enterprise, might have succeeded.

The British Guard Fleet in the Firth of Forth.

LODY was a boy when he formed the plan, working out the details with the minutest care, for the invasion of England and Scotland. I add Scotland, because this occasion was the first in the history of the German General Staff when the possibility of landing an army in Scotland was ever considered. It was this scheme of a German schoolboy which brought him to the notice of the General Staff and ensured for him a promotion which would have been much more rapid than it was, in fact, had he not excited the animosity and bad offices of Von Muller, the Chief of the Kaiser's Naval Cabinet.

Two years ago I had a long talk with Captain Von Lutwig, who was interned in a neutral country after the battle of Jutland, in which he lost his destroyer and was rescued by a neutral fishing vessel. He said:—

"Lody was too big a man for the job they gave him. He should have been Chief of the Strategical Board. Muller hated him, because Lody was suspected of saying disparaging things about a female relative of the Kaiser's friend, and he was supposed to have written an article in the Tageblatt to the effect that Von Muller's regime was a menace to German naval efficiency. Lody had many friends at Court, including Prince Henry of Prussia, who met Lody in England a week or so before the war broke out. It is perfectly true that Lody's plan for the invasion of the British Isles was adopted, with certain modifications, as the war plan of the General Staff, the only difference being that Lody intended making the real landing in Scotland and the feint attack at Dover.

"Nothing in the world could have kept the German army out of London if his scheme had been carried out—nothing! Unfortunately our people vacillated. Those who excused the invasion of Belgium and glorified in it declined to make war on Britain without a formal declaration. They were afraid of the opinion of posterity! It is inconceivable—but only inconceivable to those who do not know the German mind."

This grand scheme of his could never have been far away from Lody's mind. We can see that when we trace his movements throughout Britain.

He seemed to hover about the great centres from whence a victorious German army could debouch upon London, as though reluctant to tear himself away from the triumph-dream of which they formed a part. He was a constant visitor to the Clyde and to Edinburgh. He was eventually arrested in that part of Ireland where the German Fleet was to have its base. He visited the cities and towns through which the victorious legions of Germany were to march to their final goal, and it is said that he never spent a Sunday in London but that he rose before dawn and reconnoitred Whitehall. For the Sabbath calm which came over Whitehall had been the key of his scheme.

Before I describe Lody's scheme in detail—the first time, I believe, it has ever been described in print—let me give you a picture of Lody as a friend of mine saw him. "I knew him slightly, for I had been introduced by a German to whom he had acted as cicerone, and when I found myself in the carriage with him going north I reminded him that we had met before. We were travelling first class, and he had a corner seat facing the engine. He had a book on his knee all the journey, and in the book three or four sheets of notepaper, upon which he wrote from time to time. I had just come back from Germany and, thinking it would interest him, I gave him my impressions of the Kaiser manoeuvres, a 'corner' of which I was privileged to see. He was only slightly interested, and asked me if I had seen 'our navy.' I replied that I had seen it at Kiel on my way from Kiel to Copenhagen.

"I spoke to him about our army, and he smiled good-naturedly, and rather annoyed one by describing them as 'the finest mercenaries in the world.' We enlarged on the subject, and he then told me that England was the most difficult country to defend if he attack came from the north.

"'Look at that hill,' he said, pointing to a low range. 'The ridge runs north and south. It could be turned anywhere and does not protect the river crossing at all.'

"Like most Britons, I was profoundly ignorant of the fact that there was a river anywhere near, but with amazing clearness, he traced with his finger the course it took, and showed just where it was narrowest.

"'Most of your hill ranges run that way,' said, 'And all your rivers are spanned by a town, so that an invading force could always find cover to attack the bridgehead. There's another hill over there. It has a marsh—on the wrong side of it. Near the Peak Country you have two broad plains which would enable the invader to pass on either side of your natural defence and mask it. No, England was made before the science of war was fully developed!'

"He spoke pleasantly and cheerfully about Germany, and professed what, I believe, was a genuine admiration for our navy. He kept repeating 'It is your fleet; it is your fleet,' when I ventured to refer to the possibility of Britain being invaded, as though only the fleet mattered."

What bitterness must have been his when his first grand scheme was rejected we can only conjecture. In those days he did not bother his head about our fleet or, rather, he provided for and overcame the obstacle which it represented. His idea was to get past the fleet and if You follow his movements and read such of his letters as have been made public, you cannot fail to detect the note of bitterness against the bureaucracy who did not dare. Even his favourite quotation discovers his helpless resentment against the men who would not put his plan into action because they themselves had not made it. It was a verse from Browning:—

What hand and brain went ever paired?

What

mind alike conceived and dared?

What act proved all its

thought had been?

What will but felt the fleshy

screen?

The scheme for the invasion of Britain was based, as I say, upon the Sunday habits of British officialdom. Perhaps it is better to say the weekend habit of our people. Accompanying this, before the Fisher regime, there was a laxity at Admiralty House which to most people will be incredible. On Friday night all the head officials went away. Some, a very few, and these were not the highest, put in an appearance on the Saturday morning, read their letters, and disappeared. The same practice was followed at the Foreign Office and at the War Office. On Sunday morning Whitehall was a desert.

It was easier to find a needle in a hayrick than a Government official in Whitehall. Most of the Ministers were out of town at their country houses: all the permanent officials were week-ending, generally miles from London. The great offices of State were left to caretakers, patrolling policemen, and office cleaners.

At this time, too, not all of H. M. ships were fitted with wireless telegraphy, a novelty which was generally adopted after Fisher came to the Admiralty.

The British week-end habit, then, was the foundation of the German plot. At weekends officers are on leave, men are out of barracks visiting their relatives, ships come into port to give shore leave, train services are restricted, and fifty per cent. of railway staffs are having a day off. All shops and stores are closed: factories are closed down, 75 per cent. of the postal and telegraph staffs are away from 6 p.m. Saturday to 8 a.m. Monday—and on the Saturday it was the practice of one of the Hamburg-American liners to make a call at Dover to pick up passengers for New York.

On Saturday night or Sunday morning an Atlantic liner used to come up the Clyde to Greenock and disembark passengers. Would it have been remarkable if at the same time a great German liner put into the Firth of Forth or into the mouth of the Tay flying a signal of distress? Imagine her arriving after nightfall off the mouth of the Tay, her lights shining dimly. Imagine the port officer going off to her and not returning. Lody attached the greatest importance to the Scottish landings. With the Forth and Tay Bridges in his hands, with Glasgow in the occupation of German troops, Scotland became a great place of arms, in which he could mobilise at his leisure.

But I am anticipating. Lody's idea was this. From three to six months before his scheme was brought to a culmination, German or neutral merchants in various centres about London, Edinburgh and Glasgow would receive great stocks of preserved meats, grain, rice, flour, and foodstuffs of all description. These would come from America and the Continent and would constitute provisions for 500,000 men for three months. Twelve months before the plan was developed, big orders would be given to the various armament firms for shells, small arms ammunition, explosives, and guns.

Lody's idea was that the very openness of the orders would disarm suspicion or at the worst stimulate the British Government to increase their output, which action was all to the good from the Germans' point of view.

Then would dawn The Day, The Day of which Lody dreamt. Picture the tragedy. It is Saturday evening, the twilight of an autumn day still bathes the earth in ghostly light. All England and Scotland are at play except perhaps the railway officials and a few newspaper staffs. Just as the darkness is growing deeper, the lookout on the Admiralty Pier at Dover reports a liner standing in. She burns her lights, the light of the Hamburg-American mail, and a few passengers, who have arrived from London by special train, stand watching the giant vessel as she comes slowly through the narrow harbour entrance.

"She's coming right in, that's funny," remarks a railway man.

A great upstanding ship, which towers above the quay, she looks as though she will wedge herself between the two pierheads, but very slowly she clears them, and edger even more slowly closer to the quay. There are a few stewards leaning idly over the side, and a knot of civilian passengers. The brilliantly illuminated decks are empty otherwise. Gangways are thrown over, sailors appear like magic and, before the dumbfounded officials on the pier realise what happens, there are twenty broad gangways fixed—and then all the lights on the deck go out. Peering into the darkness the watchers see long files of men crossing the gangway. There is a scamper of feet, the flash of a bayonet, and a groan. The lights go on again. The pier is alive with grey-coated German soldiers, trained to a second. A battalion is in Dover town, mounted Uhlans clatter through the streets and out into the country, cutting the wires as they go, motor batteries speed away to take up strategical positions, the batteries and forts are seized, and before midnight Dover is in the hands of the enemy.

Then come the German warships, more transports, more grey coats, ship after ship draws up to the quays, discharges its passengers in record time and backs out. Where is our fleet? In those days it was exceptional to find warships in Dover Harbour. I myself have crossed to Calais a score of times and never seen a destroyer. They were at Sheerness, and the mouth of the Thames was already barraged with mines and the Chatham and Sheerness squadrons were bottled. Don't you see what would happen?

London would know nothing. The first intimation she could receive would come in the shape of a German occupation. Ever if she had a warning, there was nobody there to take it. There was no official on duty whose business it was to decode wires on Saturday night.

In the meantime, whilst Dover was in the hands of the enemy, great German liners were on the Clyde, on the Tay, in the Firth of Forth. There was no naval station at Rosyth in those days.

You can imagine Glasgow, Dundee, Edinburgh in the hands of the enemy without a shot being fired.

But once in, our fleet would trap them, Lody knew that.

As a boy he remembered Von Moltke'e dictum that "I know of twenty ways into Britain, but no way out."

The British Fleet would blockade the harbours, but this didn't worry the young strategist. He is the author of the "burn by sections" method of reducing an obdurate enemy. He had provisions in the country for two or three months. He had seized the arsenals, isolated Borden and Aldershot, but most important of all he had London in his hands. That was to be the pawn the Germans would offer for the surrender of the British Fleet.

He would burn London district by district unless the British capitulated, and he certainly would have kept his word. All the facts that I have related are as stated without exaggeration. It is perfectly true that until comparatively recently the defences of these shores were more or less mythical, and we depended for immunity from invasion upon the enemy—whoever he might be—declaring war in a gentlemanly way, and giving us plenty of time to complete our arrangements for giving him a warm reception. If the declaration of war had been accompanied by a simultaneous blow struck ruthlessly and fearlessly, then nothing could have saved us from being overrun.

It is rather difficult to understand why the plan was not put into operation. The Kaiser bore us no love. King Edward was on the Throne and him he hated. It was a dislike which Edward returned with interest. The Kaiser was already preaching his "holy war" against the British, and had a few personal scores to wipe off. Here was a chance which might not, and certainly ought not to have occurred again, and the German did not take it.

It is said that Lody supported his statement by an extraordinary volume of data, including statistical tables compiled from the British newspapers showing the average periods every Minister was "out of town," their favourite week-end haunts, the names of the nearest towns and villages and the character of the communications—telephonic and telegraphic—with London.

The scheme was turned down for a year. Then it was suddenly revived. Preparation was made for assembling and training the necessary troops—and then the news came that Jacky Fisher had been newly appointed to the Admiralty. He heard of these secret embarkations and drew his own conclusions.

His first step was to rush the work of filling all warships with wireless. The next step was characteristic of the old man. One Saturday the Hamburg-America liner called at Dover and unexpectedly found some submerged staging damaging her hull so badly that she had to transfer her passengers to another steamer, whereupon the Admiralty politely informed the Hamburg-America Line that it was no longer safe or convenient to pick up or land passengers, and it would be advisable if in the future the illustrious Herrs gave Dover a miss. The work at Rosyth was rushed forward, new patrols were established in the North Sea, and the week-end practices of Government officials underwent a painful revolution.

When Lody joined the German Secret Service one of his first duties was to pay a visit to England and Scotland for the purpose of examining the situation in the light of the new precautions which the British Government had instituted. For some reason or other he did not make this tour for a very considerable time after his appointment. This may have been due to the agitation amongst certain of the permanent officials of the German Foreign Office for a rapprochement with Britain. It may have been due to the fact that at the time he should have gone the Kaiser was in London, or else, as I have already hinted, to the jealousy which was displayed on more than one occasion by members of the Kaiser's personal staff.

I have never heard or met anybody who has heard of the supplementary report which Lody presented, or whether it was presented at all. It is more likely that he rejected the scheme altogether than that he tried to modify it, for the success of the enterprise depended entirely upon the unexpected landing from giant liners which arrived on our shores in the guise of passenger steamers. The original scheme was worked out in perfect detail. The ships were to have left Bremen in the morning and two hours before their departure all cables leading from the Continent to Britain were to have been picked up and cut by German cruisers specially detailed for that purpose.

Lody patrolled the German seas and could see with his own eyes the sentinel British ships which were later to take shape as the North Sea patrol. His scheme was no longer possible, and there was, unfortunately for tie German, no adequate substitute. But I think that in the abandonment of the plan Lody made certain mental reservations. He still believed that the conquest of Britain might be as easily accomplished by an attack from Scotland as from the Kentish Coast and if a Bolshevik Soviet is ever established in Berlin and secret documents are published we shall discover that the final plans of the German General Staff for the invasion of these islands were based upon the occupation of Greenock and Dundee.

If Lody had altogether abandoned all ides of seeing his scheme brought to fruition it is difficult to understand why he spent such a considerable time in Scotland, why he had headquarters at Glasgow and at Perth, or why, in pursuance of the information which he supplied, the Zeppelins made their one attempt upon the Tay Bridge. It was after the trip to Britain which Lody made for the purpose of comparing the possibilities of his scheme with the precautions we had taken, that we saw a development which was to have such alarming results in the course of the war. Lody was instructed to discover an alternative plan if the original scheme was no longer workable.

At that time Zeppelin had perfected his airship. Long flights had been made, a tremendous amount of capital had been subscribed, and the German General Staff had at last lent the light of its countenance to Zeppelin's adventure or, rather, Zeppelin's exploitation of, another man's invention. The test, and the supreme teat, was of course whether the airship had a practical military use, and it was only natural that when this came to be considered by a select aeronautical committee of the Staff that the first question asked and answered was—"What service will this new arm perform against Britain?"

In response to a telegram which reached him through London, Lody, who at the time was at Cardiff, and was there writing his report on invasion, came to London where he was met by a courier from Berlin, who bore specific instructions in regard to a new survey which Lody was asked to carry out. I believe Lody's name is to be found in the visitors' book at Kew Gardens, where he pursued his inquiries into the meteorological conditions in Britain in the previous two or three years, the strength and direction of wind, and particularly did he seek information on the experiments which the Meteorological Society had been carrying out in the upper stratas of the air.

He travelled extensively through Norfolk, and was so very busy that when his presence was required on the coalfields he was not available, and another man was sent from Ostend in his place. The sequel to these investigations was certain happenings which surprised and mystified the English people, particularly the English people of the eastern counties, and was the subject of a very great newspaper controversy which the reader of this paper will remember.

On it certain night a village police constable, patrolling a lane in Norfolk, heard a curious roaring sound in the air. He looked up and saw what he thought at first was a star of exceptional brilliance, but as it was moving he formed the conclusion that a giant airship was overhead. A postman of Norwich and a workman who was out that night confirmed the story, which was printed in several Scottish and English newspapers.

A certain section of the press waxed very humorous over the policeman, but a few days later the mysterious sound was again heard, and the moving light was seen travelling across the sky at a rate which excluded all possibility of it being a star.

The "phantom airship" became a standing joke in Fleet Street, and many were the scribes that were sent forth to grow funny at the expense of eye-witnesses. It was seen in the Midlands, it was seen in Kent and Sussex, it was heard at Cambridge, and was even heard as far west as Somerset.

Now, the truth of the phantom airship is this—that it was a Zeppelin which came from Heligoland. It war piloted by Captain Strasser, under whom was Lieut. Mathy, both men being subsequently killed in the war in the course of air raids on Britain, and in the first or the second visitation—it is not certain which—Lieutenant Lody was the navigating officer.

The new scheme of invasion was by was of Norwich and, though it is certain Lody very stoutly insisted upon the advantages which the Scottish invasion offered, he was converted to the theories of Zeppelin and was certain, even to the day of his death, that the Zeppelin would bring about the destruction of the British fleet.

Lody's work after the war broke out, futile as it was, and as he knew it was, was mainly associated with the new Zeppelin campaign. The trip in the phantom airship was the first step towards the invasion which it was our good fortune never to see carried into effect.

Lody speaking with an official on landing in America.

THE story of Lody and his activities is necessarily a fragmentary one. Those men with whom he worked in Britain are, for the main part, dead, interned, or in Germany. A woman assistant is now serving twenty years penal servitude in gaol. In piecing together the mosaics of his life many fragments are missing, many pieces may creep in which belong to some other story than this, but I do not think that we can exaggerate the importance which the chiefs of the German Secret Service attached to his work, and however far-fetched the idea may seem to many, I can say that it was no accident that the man who tracked him down and brought him to his doom was himself destroyed, together with his daughter, in the last great Zeppelin raid on London. Never was an unimportant residential neighbourhood so thoroughly and so systematically bombed as was that in which Inspector Ward lost his life.

Lody was a big man with big ideas. His theories were subsequently tested and proved, and had the man been alive to direct the operations he schemed there is little doubt that his work would have proved more fruitful than, in fact, it did.

I said last week that Lody put in a considerable time in Scotland. Whether he ever tried his loan office dodge is not known. Probably he did not, for there was no "naval town," strictly speaking, in Scotland until Rosyth came into being. But he certainly found a great deal worth the trouble of inquiring about amongst Scottish fishermen, and he was particularly interested in some of the western lochs. In all Germany's schemes, it must be remembered, Ireland figured very prominently. Upon the fact that there was a disaffected Ireland the German based many of his plans, and the West Coast of Scotland came into German calculations for just this reason, that it lay on the flank of the sea route to the western part of Ireland, which was to form the base of certain operations against the United Kingdom.

It seems incredible, yet it is nevertheless a fact, that Lody, like many of his German friends, regarded Scotland as disloyal in the sense that it was an enemy of England. The intensely strong national feeling of Scotland, the celebration of old battles which it fought against the English, the very pride it had in its flag, all these things conspired to deceive more learned men than Lody.

The truth is, as he was to discover, that never were two nations so knit together, so absolutely dovetailed one into the other and were so much the complement of each other as England and Scotland. He was to learn, too, that the English had a great admiration for this national spirit which the Scots displayed and honoured almost as much as the Scots their national heroes.

When Lody was being brought to London he remarked to one of his escort upon this very fact. Nevertheless, at the period he made his inspection and report he must have had his doubts. He does not seem to have been impressed by the West of Scotland as a base for German destroyers and light cruisers craft, and very early turned his attention from the topographical to the human aspect of his task.

He visited Aberdeen and, I believe, went once to Strathpeffer, but in the main he confined himself to that part of Scotland which lies south of a line drawn from the mouth of the Tay to the mouth of the Clyde. His greatest difficulty was to plant agents in Scotland. Despite its foreign elements, even Glasgow cannot he termed a cosmopolitan city, whilst the presence of dubious foreigners in a place like Rosyth would have been instantly detected.

Lody's inquiries about Rosyth could not have been very complete, and certainly were not satisfactory, for in the early mouths of 1914 he approached a Newcastle journalist and asked him if he would care to write a series of articles for him.

"I am representing an American magazine which is starting in New York in a few months' time," said Lody, "and I have been asked by the editor to collect articles on interesting English and Scottish ports."

It happened that the journalist in question was a free lance and had a great deal of leisure, and he accepted the offer, which was a very generous one. His first article was on the port of Newcastle which, however, did not please Lody.

"Yon only tell me what is in the guide books. What I want is an article on the shipbuilding yards, the number of slipways they have, the capacity for turning out new shipping, warships, and all that sort of thing. You might tell us something about the Tyne defences—all these things are of great interest to the American people, who want to know how a port is defended in time of war."

The unsuspecting journalist set off on his new quest, and naturally found some difficulty, particularly in relation to the defences. At last, in despair of getting the information he wanted he did what I am afraid many of us have done, he "faked;" in other words, from his large experience and his ample imagination he produced a picture of bristling forts, booms, mines and the like, which pleased the "editor's agent" so much that he commissioned the journalist to go into Scotland and write a pleasant little story about the Tay, Firth of Forth, and the Clyde.

It is an act of politeness on my part to pass over the "information" which the journalist supplied. In any case he would not convey the secrets of defence to a foreign newspaper, and I doubt very much if any of the real secrets were ever known to civilians.

Lody seems to have practised the same trick at Liverpool. It was not a bad idea to turn his spying over to a journalist, who could pursue inquiries without arousing any suspicion but, unfortunately for the success of his scheme, he happened upon a man who asked him point blank whether he wasn't a German and whether this information he required was not for the purpose of enlightening the German Intelligence Department.

Thereafter Lody gave up this method. Edinburgh to have been to him as a candle to a moth. He was constantly flitting in and flitting out, sometimes alone, sometimes in company with a woman, once or twice in the society of a man who was afterwards shot at the Tower, and went to his death smoking a cigarette.

An educated man with a knowledge of the English language has no difficulty in making friends, even in a strange country. Britain does not fall into this category so far as Lody was concerned, but he had frequently to visit districts and towns where he had neither friends nor acquaintances. The people one could pick up in a bar were not the kind of people that were of any service to Lody. He preferred men of the Professional class and, of course, he had no difficulty in securing introductions.

Where he wanted a deeper acquaintance into local life it was his practice to send for a doctor to deal with some slight or obscure complaint from which he was "suffering," but before he did this he was very careful to discover the right kind of doctor. He preferred the young men just starting on their professional career, who had plenty of time on their hands, and who were not averse to a little gossip. Failing a doctor, he would consult a solicitor over some imaginary lawsuit. Both the consultation with doctor and solicitor usually ended in an invitation to lunch or dinner, and on one occasion resulted in Lody meeting a prominent politician. This was when he had temporarily put up at an East Coast town where a bye-election was being fought. He had a ready wit, a fund of good anecdotes, and was an acquisition to any dinner party at which he found himself.

His activities were ceaseless, his energy prodigious. He had that passion for detail which is a German characteristic, and it was his practice to translate even the most trivial pieces of information into writing. Scarcely a day passed that he did not forward a long report to Ostend, which was still his headquarters.

I have been asked often whether Lody established any wireless stations in this country. There were two, and possibly three, such stations which were intended for the transmission of news, not to Germany, but To German ships which might be in the North Sea. There were hundreds of amateur wireless enthusiasts, a large number of which were German but it has never beer proved that these people were official agents of the German Government or that Lody knew or was known by them.

What he did try to do was to create a pigeon service between Germany and England, and he put before the German Intelligence Bureau a scheme for long distance racing between Yorkshire and Bremen. The prizes to be given were very handsome and the race would certainly have appealed to pigeon fanciers but for one of those curious errors into which the German is liable to fall. The scheme was put before a pigeon fancier, and he at once pointed out that the prizes were for races which started in England and finished in Germany, and that no prizes were offered for pigeons which were flown in Germany and finished their race in Yorkshire. This meant that only German competitors had any hope of winning, since pigeons were not trained to fly from, but to their homes.

This put Lody in a dilemma, because he knew that the German Intelligence Bureau had no intention of encouraging the training of a pigeon post from Germany to England. The news of the curious conditions leaked out, and came to the ears of our own Intelligence Department, who squashed the scheme, though I doubt very much if it would have come to anything.

Many speculations have been made and theories put forward as to when the German Government decided upon war. My own view, and this is based upon my knowledge of Lody, is that the decision was reached in the winter of 1913-1914.

In January Lody, who was on a visit to Scotland, was recalled, and left hurriedly for Berlin, where he attended a conference held at the Admiralty Building, a conference which lasted for three days, an was strictly confined to various espionage agents who came to Berlin from every part of Europe, from Russia, Roumania, Italy, France and from such extra European territory as Egypt.

At that conference a number of decisions were reached, and it seems that one of them was to practise the collection and despatch of urgent military and naval news by means of codes, ciphers, and other means, and since Lody was the greatest of the stunt experts his advice must have been invaluable. One official view of Lody was that he was not in England at the beginning of 1914, but that I know is inaccurate. He came bask from Berlin, met three or four people who were engaged in the collection of naval information and there began a full-dress rehearsal of the means by which the Germans intended to convey information out of this country to German headquarters.