RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

RGL offers this book to its readers courtesy of Gary Meller, Florida, who donated scans of the work from his personal copy of Two Thrillers: The Under-Dog; Blackman's Wood, Daily Express Fiction Library, London, 1936. —RG

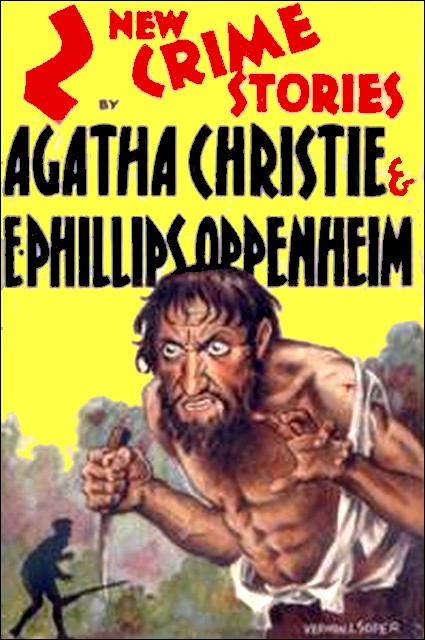

"Two New Crime Stories," The Readers Library Publishing Co., London, 1929

FASHION in fiction changes from time to time in order to accommodate itself to the whims and fancies of the novel-reading public, but the fascination of the detective mystery story remains constant; and of all the various grades of novel-readers the devotees of the detective story are the most catholic—they include almost every possible type of reader. This form of fiction seems to appeal as strongly to the simple-minded citizen as to those possessed of the most brilliant brains—Judges, Philosophers, Scientists, Statesmen—in fact all sorts and conditions of deep thinkers seem to find relaxation in the "thriller."

These two crime stories, each with its tangled skein of mystery to unravel, are among the best that come from the pens of these two famous authors. And M. Poirot himself has now become a famous detective of fiction whose name will rank with that of Sherlock Holmes.

Agatha Christie's rise to fame was almost meteoric in its rapidity. In 1921 her first novel created a tremendous sensation, and was followed almost immediately by a series of striking successes. Then came the popular play Alibi, founded on her book, which was produced at the Haymarket Theatre, London, about eight years ago. Since then Mrs. Christie has gone from success to success, and to-day stands in the foremost rank of our novelists. Being interested in archeology, she has spent much time in the Middle East, and her excellent new novel, "Murder in Mesopotamia," in which Poirot appears once again, is the result of her sojourn in that part of the world.

Mr. E. Phillips Oppenheim, born in 1866, was educated at Wyggeston Grammar School, Leicester. He wrote his first story at the age of twenty, and since that time has averaged an output of two novels a year. He was the first writer to draw attention to the danger to peace in the arming of Germany in the years before 1914. and wrote no less than nine novels on this subject. He was of course, in consequence, put on the German black list. He is a story-teller pure and simple in contradistinction to the psychological novelist who is so prevalent to-day. Many of his stories have a delightful streak of humour running through them which adds enormously to their popularity, and his sales are enormous.

He is a keen sportsman, a confirmed golfer and a first-rate shot. He spends his time between England and the south of France at Cagnes-sur-Mer, where the late W. J. Locke was his near neighbour.

The Editor.

IT was when they reached the end of the wood, which should provide the best sport of the day, that Heggs first showed signs of a curious, unbucolic disquietude. He still answered his master's remarks respectfully, but his eyes kept wandering to a long, sinister-looking belt of wood lying about a quarter of a mile away eastward. It was Ella Cartnell who first appreciated the half-mystic, half-terrified stare of those uneasy blue eyes.

"Why do you keep looking across at Blackman's Wood, Heggs?" she asked him.

He touched his hat mechanically. He was a short, cheery-faced man, in a worn velveteen coat, breeches and leggings—a man whom you would have hailed as a gamekeeper if you had met him on another planet. Sniffing restlessly about him were two good-looking Labradors. A rough-coated retriever sat by his side, wagging his tail persistently. The man was typical of his class in build, feature and speech. Yet the mystery of his eyes was the mystery of fear.

"Begging your pardon, my lady," he said, "I was just hoping that we'd keep the pheasants from flying that way. If I might make so bold, sir," he went on, turning to his master, who was standing by with half a dozen labelled sticks under his arm, "I'd like an extra gun here."

Richard Cartnell, a good-looking, large-framed young man, nodded.

"Perhaps you're right, Heggs," he acquiesced. "There's never any shooting the other side to speak of. I'll let Mr. Samson, who's walking on the left, keep well ahead and come into the ride. Then Sir John can move further down, and Mr. Johnson can come out on the meadow."

"If you'd take the corner yourself, sir," Heggs begged eagerly, "and have Mr. Morden between you and Sir John, I think that ought to stop 'em, sir, provided there ain't much wind blowing."

Cartnell handed over the sticks.

"You can place these yourself then, Heggs," he said. "Of course, I know why you want to keep the pheasants out of Blackman's Wood, but remember this can't go on for ever. We left it alone last year because it was poor old Middleton's beat, and we haven't been in this season, but if pheasants go there, have 'em out we must. There are always woodcock round the lower end, as you know."

Again there was that curious glint in the man's eyes.

"I'll never get the beaters in there, sir," he declared.

Cartnell frowned.

"What do you mean—not get them in?" he demanded. "They're the regular lot, aren't they—mostly our own men? Surely they'll go where they're told?"

"They'll go where they're told anywhere else, sir," Heggs assented. "For beaters they're as good a lot as ever I handled. But Blackman's Wood! There's a-many as wouldn't go within a half a mile of that, day-time or night-time."

They were all three at the corner of the ride and they turned and looked at the wood below. Even in the clear, frosty light of the December afternoon, there was something grim, almost repellent, in its broken outline. Every description of tree seemed to have been planted there—tall firs, standing out stark and stiff in the middle, a medley of larches, dwarfed oaks, spruces and hollies towards the further end. Even from where they stood they could realize that the undergrowth was almost like a jungle. In a small field, at the furthest extremity, was a cottage, with a row of pheasant coops stretching away from it, and a little fenced-in garden.

"What's the idea with these fellows?" Cartnell asked moodily.

Heggs took command of himself, but there was a shiver in his voice as he spoke.

"They do say, sir," he confided, "that after Barney Middleton had strangled his wife, he made his way into the wood and hanged himself. There's some in the village who do hold by that story—old man Fouldes for one, who'd been after a few sticks, and he do swear to this moment that he saw Barney's body dangling down from a tree."

"What damned rubbish!" Cartnell exclaimed. "Everyone knows Middleton got clear away from the place. The police tracked him to Southampton."

"So us have heard, sir," Heggs acknowledged; "and though a hot-tempered man he was, for sure, I've never believed that Barney Middleton was one who would lay hands on himself. Still, there's old man Fouldes as swears he's seen his body, and many others declare they've seen his ghost. I'm not one as believes in these things myself, sir," the gamekeeper went on, "but I'd rather forfeit a week's wages than take the beaters through Blackman's Wood, even if they was willing to go."

"What do you think about it, Ella?" Cartnell asked his wife.

She turned and looked at him, without a smile on her face. She was a blond, handsome woman, tall, and with a splendid figure. There was something inscrutable about her expression as she answered her husband's question.

"What do you think about it yourself, Dick?" she rejoined.

"I don't happen to be superstitious," he answered shortly. "I was down at the cottage this morning, and if I'd had gaiters on I think I should have tried for a woodcock in the lower end. Wherever I could see it looked terribly thick, though."

"You don't want any trouble with the beaters," Ella said. "I should try and keep the pheasants from breaking that way, if I were you."

"Very well," Cartnell decided. "I'll do the best I can for you, Heggs. I'll come down this end myself with Mr. Morden and Mr. Johnson. I suppose we should be considered the three best shots, and I should think we ought to be able to stop them. On the other hand, if we make a mess of it, to Blackman's Wood we shall have to go. I'll talk to the beaters if you like, Heggs."

"Don't 'e say a word to them, sir, please," the man implored. "If they've any sort of a belief that they'll be asked to go through Blackman's Wood, there isn't one of them will turn up to-morrow. Don't 'e say nothing beforehand, sir, whatever 'e do."

"All right, I won't," Cartnell promised. "Anyhow, if we can keep the pheasants out, I'll forget about the woodcock and leave the wood alone this season."

Heggs touched his hat gratefully.

"It's for the sake of all concerned, sir," he said.

They strolled up the meadow to where Cartnell's two-seater car was waiting in the lane.

"It's all clear about to-morrow now, I think, Heggs," his master summarised. "We start with two partridge drives. You send your men out early, over Barrow's land, and bring in those two outlying fields of roots, and Josiah Brown's low meadows. Bring everything you can in to the rough grasses, and plan to have it done by ten o'clock. Then, unless there's a change in the wind, we'll bring them over towards Swallow Farm, and line the bottom hedge,"

"There's a rare lot of birds if I can get hold of them, sir," Heggs observed.

"The second drive you know all about, but of course we must see which way the birds break."

They paused for a minute at the gate to look back. Again there was something of that curious expression in Heggs's eyes. With his ash stick he pointed downwards to the pleasant little stretch of country which they had left.

"D'you mark that, my lady?" he asked, turning to Ella. "There's pigeons coming in over Salter's Wood, and in the home spinneys yonder, and Gregory's cover, and never a one anywhere near Blackman's Wood. Just you look, sir," he went on, with a note almost of excitement in his tone. "Pigeons everywhere, and not a single one over Blackman's, though there's many of the trees there they do reckon to be fond of. Them birds knows something, they does. Sometimes they knows more than human beings."

Cartnell climbed into the car, where his wife had already seated herself.

"You go home and have a good night's rest, Heggs," he advised; "and put Blackman's Wood out of your mind."

During the whole of the drive home, Ella Cartnell sat speechless, her eyes

fixed on the country ahead. As they turned in at the avenue, her husband took

his pipe from his mouth and broke the silence.

"You're not tired, Ella?"

"Not in the least," she answered.

"Feeling all right?"

"Perfectly."

He looked at her in rather helpless fashion. Something had come down between them, which for months he had battled against unsuccessfully. It was there now, visible in her air of detachment, her cold aloofness, as though she were unaware even of his presence.

"What were you thinking of?" he inquired.

She turned and looked at him.

"I was wondering," she confessed, "whether we should ever know who poor Betty Middleton's lover was—the man whom Barney Middleton found her with that afternoon?"

Cartnell almost grazed a white post, as he swung into the avenue.

"Why do you want to know?" he asked.

"It would ease my mind," she replied.

The remainder of the guests for the morrow's shoot had arrived during the

absence of their host and hostess, and were being served with tea by Sybil

Cartnell, Richard's young sister. Hugh Morden, a long, lean man, with the

typical clean-shaven barrister's face, rather full lips, and eyes of a

curious grey-green shade, was standing with his back to the fire, a cup of

tea in his hand, listening to Cunningham's description of a public dinner on

the night before.

Sir John Cunningham, as a brief-giving lawyer, was entitled to his attention, which was certainly all that he did receive, for Morden was evidently distrait. At the entrance of his host and hostess, however, his whole expression changed. He greeted Cartnell in the perfunctory manner of old friends who were constantly meeting, but his eyes glowed as he took Ella's hand and, bending down, whispered something in her ear. She turned away, with a little laugh.

"So sorry to be late, you people," she apologized. "I hope Sybil's been looking after you. We've been out marking the stands for to-morrow's shoot."

"Up against a superstitious gamekeeper, too," Cartnell observed. "You and I, Morden, and Johnson, too, have got to shoot our best to-morrow. Heggs tells me that if we can't keep the pheasants from going into Blackman's Wood, there'll be a riot amongst the beaters."

Freddie Samson, a pink-and-white athletic-looking young stockbroker, who had been whispering in Sybil's ear, glanced up.

"What's the trouble with Blackman's Wood?" he inquired.

"Haunted," Cartnell explained. "One old man in the village declares that he has seen Barney Middleton's body hanging there, and there are twenty or thirty who swear that they've seen his ghost on moonlight nights."

"I thought that sort of thing had died out, even in these remote districts," Morden remarked, a little satirically. "You're not going to humour the louts, I hope, Cartnell."

The latter shrugged his shoulders.

"I can't drive them in if they won't go," he pointed out. "As a matter of fact, though, unless we lose our pheasants from the big wood, and they find their way there, it won't be worth going through."

Conversation drifted into other channels. In the background of the little circle, Richard Cartnell, with a cup of tea in his hand, lounged against the corner of a table, apparently listening to a discussion upon a recent election, but in reality watching his wife and Morden. He was by nature an unsuspicious man. In their twelve years of married life, Ella had never once given him cause for serious uneasiness.

Her undoubted attraction had always brought her a train of admirers, with whom she had amused herself light-heartedly but discreetly. Morden, however, from the first, although silent in manner and secretive in his methods, had betrayed an infatuation which half surprised and half provoked his host. He watched them now gloomily. There was something about their confidential whispers, their reserves, the slightly forced smile with which Ella answered the remarks addressed to her by any of the others, which puzzled him.

They were all intimates. Jack Mason, an old friend of Ella's, a clubman who seemed to spend half his time in country houses, Sinclair Johnson, M.P. for the Division, and Jack Halloway, a nephew of the house, were all talking away of their mutual friends, and exchanging gossip as to their doings.

More and more, Ella and Morden remained outside the little circle. What the devil could the fellow be saying, Cartnell wondered, as he watched him lean closer and closer towards her. Finally, in a fit of restlessness he strolled off, with his hands in his pockets to the gun-room. He took down one of his Purdeys, to be sure that it was properly oiled, removed the lid from a fresh case of cartridges, tried to occupy himself in any way in order to regain a normal attitude of mind. When he returned to the lounge, Ella and Morden had disappeared.

"Where's Morden?" he inquired.

"Gone with Ella to the billiard-room," Sybil replied, bending forward to light a cigarette. "I say, Dick, what's the matter with Ella? She seems up in the clouds half the time. Is she having a flirtation with Hugh Morden?"

"Not that I'm aware of," her brother answered. "Perhaps," he added, with gloomy sarcasm, "even if they were, I might be just the one person whom they wouldn't take into their confidence."

"That's all very well," Sybil complained, "but I'd marked Hugh Morden down for my own. He never leaves Ella's side if he can help it. See to it, Dick, there's a dear! Separate them, and hint that there's another of the same family without a hulking husband in the way."

"Talking about Blackman's Wood," young Samson observed, throwing down an evening paper and joining them, "that gamekeeper of yours was never caught, was he, Cartnell? What was it all about, anyhow?"

"A simple, but alas! a common story," Cunningham recounted. "Middleton was supposed to have gone home towards the end of a day's shooting earlier than he was expected, and found his wife a little too pleasantly engaged with a caller. He adopted primitive measures, and strangled her."

"How sweet of him!" Sybil exclaimed. "So unlike the modern husband!"

Some impulse prompted Cartnell to turn his head. Morden and Ella had apparently been crossing the hall, and were standing now, as though transfixed, upon the edge of the circle. To Cartnell there was something terrifying about the strained look in his wife's face, an expression almost of horror in the eyes that met his. By her side Morden stood, grave and expressionless, save that there was a faintly cynical turn at the corners of his lips. .

"Please don't depress us any more by talking about that horrible affair," she insisted angrily. "You've all had a longish journey—why don't we change early and have more time for cocktails? Perhaps by then you'll all think of something more cheerful to talk about. This isn't a palace, as you know, and you've only two bathrooms to scramble for."

Everyone acquiesced, and there was a prompt exodus from the hall. Cartnell, after a few minutes' reflection, went sombrely to his room, knocked at the door of his wife's apartment, and entered.

"What is it?" she asked, startled.

"Need it be anything particular?" he rejoined quietly. "I just strolled in."

"Why—of course not," she answered. "Do you want the bathroom?"

"Presently."

He sank into an easy-chair, and pondered for a moment or two.

"Ella," he said, "I have never interfered with any of your harmless flirtations—in fact, I have sometimes encouraged them—but I cannot absolutely ignore the fact that this change in your manner, which I ventured to hint at the other afternoon, all dates from this summer, when Morden stayed down with us. Are you falling in love with him?"

She swung round, relentlessly beautiful notwithstanding the trouble which lurked in her eyes.

"If I am," she demanded, "do you complain?"

"Most vehemently," he replied, "if it is in any way the cause of your altered demeanour towards me. Furthermore, I don't mind telling you that I would rather you had chosen any other friend I have to amuse yourself with."

"And why?"

"Because," Cartnell answered deliberately, "Morden, who is a good fellow with us men, and whom we all like and admire because he is fiendishly clever, is not to be trusted with a woman."

"You say that!" she murmured.

"I do," he assented. "A good many men with attractive wives have found it out before, and have had to have him on the carpet. I am wondering whether that will happen to me."

She rose to her feet and moved slowly towards him. She was almost as tall as he was.

"Dick," she said, "I never believed that you were mean enough to say these things about a man who is a guest in your house. Why do you ask him to shoot? Why do you have him here at all?"

"Because, my dear," he replied, "I have always believed in the old saying—that there is honour amongst thieves. I know very well that Morden can't be trusted with a woman, but that isn't my business until it becomes my business. If ever it should," he added, rising to his feet, "I should know how to deal with him."

He passed back to his room. His wife, looked after him until the door was closed. Then she returned to her seat before the-looking-glass.

Late that night, Heggs, after he had knocked out his pipe and prepared for

bed, slipped out from his cottage door, glanced up into the tops of the

trees, listened, moistened his finger, and held it up in seafaring

fashion.

"What are you after, John?" his wife called from the open door. "Be you thinking there's poachers about to-night?"

John Heggs shook his head.

"No fear of that," he answered. "The Sergeant's sending a couple of men round to give me a night's rest. It was just the wind."

It was a somewhat listlessly spent evening at Cawston Farms, as Cartnell's

country house was called. For some reason or other, everyone was sleepy and

anxious to go to bed early in view of the shoot on the following day. There

was difficulty, even, in making up a rubber of bridge for Cunningham. Morden

flatly refused to play, Ella also excused herself; so, eventually, Cartnell,

an indifferent performer who loathed the game, was forced to cut in.

They played in the lounge, and Cartnell committed every sin known to the card tyro. He revoked, he neglected to attempt the simplest finesse, he led to no trumps as though it were a trump suit, he reduced his respective partners to tears and blasphemy. After the game was over, Cunningham walked to the sideboard and mixed himself a whisky-and-soda. For a Portland Club authority, he had kept his temper admirably.

"Dick," he advised, "get away to bed and have a long rest. No man could make such an utter idiot of himself with the cards if he hadn't something on his mind. Go and sleep it off before to-morrow."

Cartnell accepted the rebuke humbly,

"I'll just round the others up first," he observed. "I think everyone's for turning in early."

In the smoking-room he found only Jack Mason and Samson yarning, and Johnson fast asleep. He passed on to the billiard-room, opened the door, and stood for a moment upon the threshold. Morden and Ella were leaning over the billiard-table, Morden talking earnestly, his hand resting upon hers. With a swiftness which bespoke long practice, he drew his fingers away at the opening of the door. He was careful, however, not to change his position.

"Got a hiding, as I knew I should, Dick," he remarked. "No one can give Ella fifty."

Cartnell advanced further into the room. His wife turned and faced him. She was a little nervous, but his expression told her nothing.

"I think you had better go and look after your other guests, Ella," he suggested. "They are all thinking of going to bed."

He held the door open for her, and she passed out silently.

"Bed's not a bad idea. I think I'll be off, too," Morden announced with a yawn.

Cartnell, however, closed the door and stood with his back to it.

"Just one word with you, Hugh," he said. "You spoke just now of Ella having given you a hiding at billiards. Aren't you rather asking for one yourself?"

"Am I?" was the cool rejoinder. "I don't think so."

"A man's private life," Cartnell went on, "is usually disregarded by other men. I won't allude to yours, Hugh, except so far as to say that you will be a welcome guest here in the future only if you change your attitude towards my wife."

"My dear fellow!" Morden expostulated. "You don't imagine for a moment—"

"Of course I don't," Cartnell interrupted, "but that is all because I trust my wife, not you. However, wait one moment; that isn't all I have to say."

"With a man of your physique blocking the way," Morden drawled, "I hesitate to confess that I am dying for a whisky-and-soda."

"Someone," his host went on deliberately, "seems, ever since last summer, to have been poisoning my wife's mind against me. I don't know what I am supposed to have done—I can only make the vaguest guess—but I want you to understand this, Hugh. If I discover that anyone at any time has been lying to her about a particular incident concerning which I am free to admit that I have rather stifled inquiries, for certain reasons, it will not be a matter of a hiding. I shall take that man by the throat, and I shall let him go when his lips are black—you know what that means."

Hugh Morden, for a moment, had lost his equanimity.

"What incident?" he demanded. "What are you talking about?"

Cartnell opened the door.

"You know very well, Hugh," he concluded, "that I am referring to the incident of Barney Middleton's wife. Go and get your whisky-and-soda."

No more successful partridge drives had ever been organized on the Cawston

shooting than the two which, on the following morning, formed the prelude to

the serious business of the day. The wind had completely dropped, and, wild

though a great many of the birds were, the intervening cover was so scanty

that, although the drive was a long one, covey after covey dropped down in

the great field of rough grass according to plan.

The seven guns lining the hedge saw the silent, flag-bearing procession of men and boys move down the hillside and slowly close in towards the boundaries of the field. There was a brief silence—then Heggs's whistle, followed by Cartnell's reply, and the beaters made their way through the hedges. A little thrill ran down the line. There was no uncertainty about this. Even the loaders—an impassive race of men as a rule—showed genuine interest in what was happening, and Cunningham, who shot but rarely, practised changing guns with his man. Then came the first warning whistle as a covey rose from just under the feet of one of the beaters, flew straight for the hedge, broke beautifully round some trees, and came over high and scattered.

The next twenty minutes was almost an epic in the history of the shoot. For once, birds, when they did swerve, left it too late, and flew high and fast down the line of the guns. Scarcely a covey went back, and just as the sport was thinning down, odd Frenchmen kept getting up one by one, flying like bullets to their melancholy but glorious end.

"Very nearly the best drive I ever had in my life," Freddie Samson declared, as he lit a cigarette and handed his gun over to his loader. "Very few runners, either. Dick, I never thought this little crowd could shoot so well. What do you think we got?"

"No idea," Cartnell replied. "I got twelve brace, and Morden was shooting beautifully. He must have got more. What did you do?"

"Ten brace and a half, and a couple of runners," Samson announced.

"Heggs has picked up one of the runners already, sir," his loader put in.

"What a day for driving!" Mason exclaimed, as he strolled up. "Never had such a ten minutes that I can remember. Not a breath of wind, and they came marvellously, I never saw the crowd shoot better, either. That was a peach of a right-and-left you got out of the second covey, Dick."

They all strolled away together across the stubble, everyone a little exhilarated. Only the host and Hugh Morden remained somewhat silent. The latter's long-drawn face seemed more than usually set. He smoked countless cigarettes, and kept on a line of his own, a few yards away from the others. His unsociability, however, gave rise to no comment, for everyone knew that he talked but seldom when shooting. As soon as the game had been collected and the cart loaded, Heggs hurried up to his master.

"I've sent half the beaters round to bring in Richards's stubbles, sir," he announced, "and I thought if so be you were willing to wait a bit, I'd sweep the left-hand beaters right round to the Orford boundary, fall in with the others, and all come on together from the Lone Farm. You'll line the thirty-acre meadow hedge, but I think you'll have to take it a little wide, sir."

"Quite sound, Heggs," Cartnell approved. "We shan't be able to see you until you're actually in the roots, so don't forget to whistle."

The man suddenly turned his head and sniffed.

"What's the matter?" his master asked.

"Nothing, sir. I just thought—I fancied there was a breeze coming up."

Cartnell glanced at the sky.

"Might get one later on—not much sign of it at present. . . . Guns this way! We've half a mile to walk. Anyone like a lift in the game-cart? There's John with the whiskies-and-sodas and cocktails somewhere about, too."

"It's exactly an hour too early," Cunningham declared, looking at his watch. "Only one hour, mind you. We'll keep John in sight!"

The next drive, though not quite so productive, was almost as exciting as the first. Then there were three spinneys to knock out—one of which produced an unexpected show of woodcock. When they sat down to lunch on the lawn in front of Heggs's cottage, everyone was a little exultant, and good-tempered. Cunningham, who was a man of figures, produced his note-book.

"We're ahead of last year on this beat, by seventeen and a half brace of partridges, thirty-one pheasants and seven woodcock. Hares—we only got twenty-seven, did we? We're three hares short. What a morning! Ella, you and I must have a cocktail together, and, if you don't mind, Dick, I'd like to take a double one to Heggs. With only one other man who knew anything at all about the job, he brought those birds to-day as cleverly as anything I've ever seen."

Heggs accepted congratulations with a modest grin, and drained the contents of the glass offered him. They lunched at a long table set out on trestles, after Sybil, from a hastily improvised bar, had served everyone with cocktails. Hugh Morden, as usual, found a place by Ella's side. Cartnell, at the other end of the table, was as far removed as possible. To all appearance, he never glanced either towards his wife or Morden. Nevertheless, both were at times uneasily conscious of his presence. No one else appeared to notice that there was a cloud upon what was otherwise certainly a wonderful party.

After lunch came the pièce de resistance—the shooting of the

wood. From the moment when the places were taken for the first

drive—usually an unimportant one—a change came over Heggs. The

effect of the extra glass of beer he had drunk at luncheon time, with a view

to drowning his apprehensions, had passed. He kept looking at the sky.

Already the tops of the trees in the wood were rustling. He turned to his

master almost despairingly.

"There's a west wind coming up for sure, sir," he groaned. "It will carry them pheasants right away to Blackman's Wood."

Cartnell, moody and depressed himself, was unsympathetic.

"Let 'em go there, then, if they can get past Mr. Morden and me," he said. "The woodcock are worth one beat, anyway."

For a moment Heggs stood quite motionless. Again that rare expression of mysterious terror brought out the lines in his weather-beaten face. It lurked there in his eyes as he glanced furtively down towards the hated spot.

"Come along, Heggs," his master enjoined sharply. "These two first beats aren't up to much, but we'd better get them over."

The shooting began—a trifle erratic after a somewhat gay luncheon party, but soon settling down. As was always the case, the result of the first two beats was simply to drive the birds into the lower end of the wood, where the undergrowth was much thicker. The twenty or thirty that came out were satisfactorily disposed of, and certainly not half a dozen reached the dreaded shelter of Blackman's Wood. For the final beat, Heggs himself came forward to superintend the placing of the guns. He brought Sinclair Johnson down to the extreme end of the ride, almost in the meadow, in line with Cartnell and Morden. The wind had freshened by now, and a couple of cocks, disturbed before their time, simply vol-planed down to Blackman's Wood. Heggs watched them with a groan.

"They'll come out this side, sir, whatever we do," he muttered, as he passed his master on the way back.

"Don't be a fool, Heggs," Cartnell enjoined irritably. "Keep your right well forward, and have the hedge knocked from outside."

Heggs's reply was respectful but gloomy.

"I'll do all that man can to keep they birds straight, sir," he promised.

He rejoined the beaters and blew his whistle. The familiar sound of the tapping of trees recommenced, and almost at once the pheasants began to come over. Ella had been in the ride with Mason and Samson, but as soon as the shooting started she came out into the meadow, and deliberately planted her stick a few paces behind Morden's loader. One or two pheasants broke early over Cartnell, and a woodcock, all of which he disposed of. Then, without the slightest warning, the tragedy of the day loomed up. The whistle blew continually, pheasants seemed to be rising from all parts of the wood, and practically the whole of them streamed over Morden's head, or between him and Johnson. That Morden should have missed the first one with both barrels, and have done no better with his second gun, was unusual, but comprehensible, because he had had very little shooting since luncheon, but what followed was simply amazing. Difficult or easy, high or low, overhead, to his left or to his right, Morden, the crack shot of the party, missed every bird he aimed at.

Everyone in sight looked at him in astonishment. Heggs came staggering out of the wood to see what had happened, and stood transfixed, as he watched the long line of pheasants streaming away to Blackman's Wood. Cartnell, abandoning all etiquette, moved up ten paces, and a little backwards, and continually shot the birds which sailed over Morden unscathed. Johnson, in response to a gesture from his host, did the same, but the situation was already lost. Nothing that they could do could atone altogether for the fact that Morden, in the one commanding position, seemed completely paralysed. Every vestige of colour had gone from his cheeks, and there was a savage gleam in his eyes. As one huge cock passed smoothly over his head untouched, he threw down upon the ground the gun which he had just discharged, and almost forgot to take the second which his loader was handing him.

"Anything wrong with you, Morden; are you ill?" Cartnell called out.

Morden just turned his head, and his expression was ghastly.

"I don't know," he muttered. "Change places with me, quickly."

Cartnell obeyed, bringing down a right-and-left of cock pheasants even as he took up Morden's vacated place. And then a stranger thing than ever happened. The pheasants which, with one accord, seemed to have made for Morden, made for him still, and the tragedy was once more repeated. Cartnell and Johnson missed nothing, but an odd bird now and then was all they got. Towards the end Morden suddenly threw down his gun again and held his head with both hands. Cartnell moved back behind him, and waved Johnson to come out into the field, but the mischief was done. There were a couple of hundred pheasants in Blackman's Wood, and Morden, with his hands still clasping the sides of his head, was swaying as though about to collapse. Ella leaned forward and touched him on the shoulder.

"Are you ill?" she whispered.

"I don't know," he gasped. "I don't know what's come over me. I think I'll go home—come with me."

Cartnell strolled up to him, and the two men looked one another in the eyes. Morden still seemed on the point of collapse.

"You can't go home, Hugh," Cartnell said brutally. "You put 'em into Blackman's wood, you let 'em go there—God knows why. You must shoot 'em when we fetch them out."

Morden made no reply. The refreshment cart, which Ella had sent for, came lumbering up. He stumbled towards it and helped himself to a strong brandy-and-soda. The effect was instantaneous. There was a more natural colour in his cheeks, and he regained some measure of his self-possession.

"All right," he agreed; "I'll do my best. I don't know what came over me—a liver attack, perhaps. I'm damnably sorry."

Very slowly, and like a man bent on a portentous errand, Heggs approached his master. The beaters were standing about in little groups, talking.

"Sorry Heggs, but we'll have to have those birds out of Blackman's Wood," Cartnell told him firmly. "Get it at the bottom end, and bring them this way. I'll send a couple of guns with you for the outsides. I'll place the others. We'll leave this side open. They aren't likely to come out against the wind. If they do, they'll be going home."

Heggs touched his hat. In his tone there was a note of desperation.

"I'm sorry, sir," he announced. "Them beaters, they won't go in Blackman's Wood."

"You mean that they refuse to obey orders?"

"Most on 'em, sir, and the rest ain't willing."

"And why not?" Cartnell demanded.

"It's no good beating about the bush, sir," Heggs replied, his coarse hands with the broken nails trembling as he leaned forward on his gnarled stick, "There's a dozen at least amongst 'em as can swear that they've seen Barney Middleton's ghost hanging round at the back end, just outside his cottage. They say he drownded heself somewhere, and keeps coming back to see the spot where he strangled his wife. I can't get 'em in no-how, sir."

"I'll talk to them myself," Cartnell announced.

He walked across and confronted them—a motley group, boys, youths and elderly men, in every variety of costume, but all of them wearing the leggings which had been Ella's Christmas gift.

"Look here, my men," Cartnell began, "what's this nonsense about not wanting to go into Blackman's Wood? You've seen for yourselves that the pheasants are there, and we know there are woodcock."

No one was willing to be spokesman. They shifted their feet and moved about nervously.

"Gosling, now—what about you?"

Gosling took off his hat and scratched his head.

"Mr. Cartnell, sir," he said, "I be a serious man as you know, and a man as has found religion. I don't hold with these stories of ghosts, but when there's half the village swears they've seen Barney Middleton's spirit wandering round in that there wood and round about the cottage, well, it does make one think, so to speak; and for the sake of the eight bob and beer we get for a day's beating, I'd just as soon keep out of trouble, sir. I never met a spirit yet, and I ain't anxious."

There was a little murmur of assent. One or two of the younger ones, however, laughed.

"I don't mind," a nephew of Middleton declared. "The old man wouldn't do me no harm."

"Same here," another lad joined in. "It ain't like as though it were night."

"Look here, then," Cartnell announced, "I'll give an extra five shillings to every beater who will come through Blackman's Wood. Now then, who's for the back of it?"

One by one, like sheep, they followed young Middleton. There were only five who refused, and they stood in a little group by themselves outside the wood. Heggs came up to his master with laggard footsteps. He seemed suddenly to be many years older.

"Is it your will, then, sir," he asked in a low tone,"that we go through the wood? "

"Of course it is, Heggs. Take your men along. Mr. Mason and Mr. Halloway will walk up with you. Knock the place out as well as you can, and don't forget the holly bushes."

They straggled off in a long, irregular line, and Cartnell busied himself in arranging the stands. Morden, after another brandy-and-soda, seemed to have recovered himself. He sat on his shooting-stick, his gun balanced across his knees, and his eyes fixed upon the forbidding little wood in front. The edge of it was bordered by a quantity of small black firs, but behind was a curious medley of trees of every description, and an undergrowth of bracken and rank grass, which appeared not to have been touched for years. A cock pheasant came flying out at a great height, almost before the beaters were in, and Morden brought it down with his first barrel, a crumpled mass of feathers, shot through the head.

"You're all right again now," Ella whispered. "Splendid!"

The whistle sounded continually, and pheasants began to come over. Everyone shot well, and Morden especially. The sound of the tapping of the trees grew nearer and nearer. Suddenly there was a silence. The whole line of beaters seemed to have stopped. The silence continued. Cartnell walked forward a yard or two.

"What's wrong, Heggs?" he called out.

Almost before the words were out of his mouth, there arose a chorus of wild yells, blasphemous, panic-stricken shrieks of unrestrained terror. Out from the wood, on both sides, tumbling through the hedges, running in frantic haste, came the beaters. Even when they were clear of the borders and in the meadow, they ran like madmen. Middleton's nephew, who had led the way in, fell head over heels and picked himself up, sobbing, to tear after the others.

"What the devil's the matter!" Cartnell shouted. "Heggs!"

A choked voice from somewhere in the wood:

"For the love of God stand clear, sir. Get the lady away! He's coming!"

"What's got the fellows?" Cartnell cried. "Have they all gone mad? Can anyone see anything?"

Almost at that moment the horror arrived. Crashing down the middle of the wood came some undistinguishable shape, too big for a fox, too big for a stray deer even—it was something which seemed to come in bounds, like a huge dog plunging straight ahead.

"Are you loaded, Hugh?" Cartnell asked him swiftly.

Morden made no answer. He was standing as though petrified, looking at something clear now of the trees, leaping through the bracken. It came over the low hedge and rails in its stride, and for that first moment there was not a person who saw it who was not paralysed with fear. It came like an orang-outang, six feet high, sometimes on all fours, then upright, a creature who had once been a man, with some fragments of filthy clothing and sacking still left, a great ragged beard, hair almost down his back, gaunt, deep-set horrible eyes, fingers black, patches of his body bleeding. Not for one instant did it hesitate. Clear of the wood, it went straight, like a savage animal who has marked its prey, towards Morden. It had come out on all fours, but as it approached it reared itself, and with a terrifying yell—a yell which no one ever forgot who heard it—and with great lopping springs, drew near to its cowering victim.

"Shoot!" Cartnell cried. "Shoot it, Hugh!"

Morden's gun, irresolutely lifted, wobbled in his hand. Suddenly his loader leaned past him, raised the second gun to his shoulder, and fired. For a single second the brute faltered. Then it came on again, its black, talon-like hands stretched out towards Morden, who stood there too terrified for flight, his gun, which had slipped through his nerveless fingers, lying upon the ground. At the last moment he turned and ran, ran blindly away, with a shriek of fear. His start was too late, however. He stumbled, and over he went, with his pursuer on the top of him. Cartnell had a horrible moment's view of those fingers clutching Morden's white throat, grinding their way into his windpipe, whilst Ella's shrieks filled the air.

Cartnell, who had sprung forward hurled himself upon the attacking beast. The loader seized him from behind, but their united strength was absolutely useless. They might as well have tried to move a mountain, until the last breath of life had sobbed itself away from Morden's lips. Then, and not till then, that grip relaxed, and the beast rolled over, the blood streaming from a wound in his chest where the loader had shot him.

"My God!" Cartnell faltered, "it's a man—it's Middleton!"

It was not until a fortnight after the inquest and funeral that Ella

Cartnell, stretched upon a steamer-chair in mid-ocean on her way to Kenya,

broke the silence which seemed to have been established by mutual consent

upon a certain subject. She looked away from the sea, and turned her head

towards her husband.

"Dick," she asked, "did you know that it was Hugh Morden who had been the lover of Barney Middleton's wife?"

"I guessed it," he acknowledged. "That's why I rather went out of my way to have the matter hushed up. He was always making some excuse to stroll down there, and the day the thing happened, I knew that the telephone call back to the house was faked."

"And yet you said nothing to me?"

"What could I say?"

"You must have guessed what he was trying to make me believe."

"Not until the day before the shooting party," Cartnell assured her. "You see, he'd been a kind of a pal once. I couldn't believe he'd do such a dirty trick. Before that day, until then, I simply thought—I feared that you'd taken a fancy to him.''

"Yet you wouldn't tell me?"

"Don't see how I could exactly."

She shivered a little. Her left hand stole underneath the rug, her fingers felt for his and clutched them convulsively,

"Men are different," she murmured.