RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

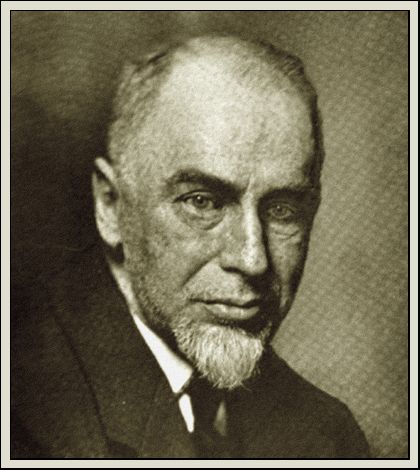

Edward Page Mitchell.

EDWARD PAGE MITCHELL (1852-1927), who worked as an editor and story writer for the New York daily The Sun, is recognized as a major figure in the early development of the science fiction genre.

His works include stories about a time machine ("The Clock that Went Backward," 1881) and an invisible man ("The Crystal Man," 1881), both of which pre-date H.G. Wells' novels on these subjects (1895 and 1897).

Other works include stories about faster-than-light travel ("The Tachypomp," 1874), a cyborg ("The Ablest Man in the World," 1879), teleportation ("The Man without a Body", 1877), and mind-transfer ("Exchanging Their Souls," 1877).

Besides works of science fiction, Mitchell wrote stories in the fantasy and horror genres. RGL offers special compilations of tales in all three categories.

—Roy Glashan, 22 January 2023

YOU know that when a man lives in a deserted castle on the top of a great mountain by the side of the river Rhine, he is liable to misrepresentation. Half the good people of the village of Schwinkenschwank, including the burgomaster and the burgomaster's nephew, believed that I was a fugitive from American justice. The other half were just as firmly convinced that I was crazy, and this theory had the support of the notary's profound knowledge of human character and acute logic. The two parties to the interesting controversy were so equally matched that they spent all their time in confronting each other's arguments, and I was left pretty much to myself.

As everybody with the slightest pretension to cosmopolitan knowledge is already aware, the old Schloss Schwinkenschwank is haunted by the ghosts of twenty-nine medieval barons and baronesses. The behavior of these ancient spectres was very considerate. They annoyed me, on the whole, far less than the rats, which swarmed in great numbers in every part of the castle. When I first took possession of my quarters, I was obliged to keep a lantern burning all night, and continually to beat about me with a wooden club in order to escape the fate of Bishop Hatto. Afterward I sent to Frankfort and had made for me a wire cage in which I was able to sleep with comfort and safety as soon as I became accustomed to the sharp gritting of the rats' teeth as they gnawed the iron in their impotent attempts to get in and eat me.

Barring the spectres and the rats, and now and then a transient bat or owl, I was the first tenant of the Schloss Schwinkenschwank for three or four centuries. After leaving Bonn, where I had greatly profited by the learned and ingenious lectures of the famous Calcarius, Herr Professor of Metaphysical Science in that admirable university, I had selected this ruin as the best possible place for the trial of a certain experiment in psychology. The hereditary Landgraf Von Toplitz, who owned Schloss Schwinkenschwank, showed no signs of surprise when I went to him and offered six thalers a month for the privilege of lodging in his ramshackle castle. The clerk of a Broadway hotel could not have taken my application more coolly or my money in a more businesslike spirit.

"It will be necessary to pay the first month's rent in advance," said he.

"That I am fortunately prepared to do, my well-born hereditary Landgraf," I replied, counting out six dollars. He pocketed them and gave me a receipt for the same. I wonder whether he ever tried to collect rent from his ghosts.

The most inhabitable room in the castle was that in the northwest tower, but it was already occupied by the Lady Adelaide Maria, eldest daughter of the Baron von Schotten, and starved to death in the thirteenth century by her affectionate papa for refusing to wed a one-legged freebooter from over the river. As I could not think of intruding upon a lady, I took up my quarters at the head of the south turret stairway, where there was nobody in possession except a sentimental monk, who was out a good deal nights and gave me no trouble at any time.

In such calm seclusion as I enjoyed in the Schloss it is possible to reduce physical and mental activity to the lowest degree consistent with life. St. Pedro of Alcantara, who passed forty years in a convent cell, schooled himself to sleep only an hour and a half a day, and to take food but once in three days. While diminishing the functions of his body to such an extent he must also, I firmly believe, have reduced his soul almost to the negative character of an unconscious infant's. It is exercise, thought, friction, activity, that bring out the individuality of a man's nature. Professor Calcarius' pregnant words remained burned into my memory:

"What is the mysterious link that binds soul to the living body? Why am I Calcarius, or rather why does the soul called Calcarius inhabit this particular organism? (Here the learned professor slapped his enormous thigh with his pudgy hand.) Might not I as well be another, and might not another be I? Loosen the individualized ego from the fleshy surroundings to which it coheres by force of habit and by reason of long contact, and who shall say that it may not be expelled by an act of volition, leaving the living body receptive, to be occupied by some non-individualized ego, worthier and better than the old?"

This profound suggestion made a lasting impression upon my mind. While perfectly satisfied with my body, which is sound, healthy, and reasonably beautiful, I had long been discontented with my soul, and constant contemplation of its weakness, its grossness, its inadequacy, had intensified discontentment to disgust. Could I, indeed, escape myself, could I tear this paste diamond from its fine casket and replace it with a genuine jewel, what sacrifices would I not consent to, and how fervently would I bless Calcarius and the hour that took me to Bonn!

It was to try this untried experiment that I shut myself up in the Schloss Schwinkenschwank.

Excepting little Hans, the innkeeper's son, who climbed the mountain three times a week from the village to bring me bread and cheese and white wine, and afterward Hans's sister, my only visitor during the period of my retirement was Professor Calcarius. He came over from Bonn twice to cheer and encourage me.

On the occasion of his first visit night fell while we were still talking of Pythagoras and metempsychosis. The profound metaphysicist was a corpulent man and very short-sighted.

"I can never get down the hill alive," he cried, wringing his hands anxiously. "I should stumble, and, Gott im Himmel, precipitate myself peradventure upon some jagged rock."

"You must stay all night, Professor," said I, "and sleep with me in my wire cage. I should like you to meet my roommate, the monk."

"Subjective entirely, my dear young friend," he said. "Your apparition is a creature of the optic nerve and I shall contemplate it without alarm, as becomes a philosopher."

I put my Herr Professor to bed in the wire cage and with extreme difficulty crowded myself in by his side. At his especial request I left the lantern burning. "Not that I have any apprehension of your subjective spectres," he explained. "Mere figments of the brain they are. But in the dark I might roll over and crush you."

"How progresses the self-suppression," he asked at length, "the subordination of the individual soul? Eh! What was that?"

"A rat, trying to get in at us," I replied. "Be calm: you are in no peril. My experiment proceeds satisfactorily. I have quite eliminated all interest in the outside world. Love, gratitude, friendship, care for my own welfare and the welfare of my friends have nearly disappeared. Soon, I hope, memory will also fade away, and with my memory my individual past."

"You are doing splendidly!" he exclaimed with enthusiasm, "and rendering to psychologic science an inestimable service. Soon your psychic nature will be a blank, a vacuum, ready to receive—God preserve me! What was that?"

"Only the screech of an owl," said I, reassuringly, as the great gray bird with which I had become familiar fluttered noisily down through an aperture in the roof and lit upon the top of our wire cage.

Calcarius regarded the owl with interest, and the owl blinked gravely at Calcarius.

"Who knows," said the Herr Professor, "but what that owl is animated by the soul of some great dead philosopher? Perhaps Pythagoras, perhaps Plotinus, perhaps the spirit of Socrates himself abides temporarily beneath those feathers."

I confessed that some such idea had already occurred to me.

"And in that case," continued the professor, "you have only to negative your own nature, to nullify your own individuality, in order to receive into your body this great soul, which, as my intuitions tell me, is that of Socrates, and is hovering around your physical organization, hoping to effect an entrance. Persist, my worthy young student, in your most laudable experiment, and metaphysical science—Merciful heaven! Is that the Devil?"

It was the huge gray rat, my nightly visitor. This hideous creature had grown in his life, perhaps of a century, to the size of a small terrier. His whiskers were perfectly white and very thick. His immense tushes had become so long that they curved over till the points almost impaled his skull. His eyes were big and blood red. The corners of his upper lip were so shriveled and drawn up that his countenance wore an expression of diabolical malignity, rarely seen except in some human faces. He was too old and knowing to gnaw at the wires; but he sat outside on his haunches, and gazed in at us with an indescribable look of hatred. My companion shivered. After a while the rat turned away, rattled his callous tail across the wire netting, and disappeared in the darkness. Professor Calcarius breathed a deep sigh of relief, and soon was snoring so profoundly that neither owls, rats, nor spectres ventured near us till morning.

I had so far succeeded in merging my intellectual and moral qualities in the routine of mere animal existence that when it was time for Calcarius to come again, as he had promised, I felt little interest in his approaching visit. Hansel, who constituted my commissariat, had been taken sick of the measles, and I was dependent for my food and wine upon the coming of his pretty sister Emma, a flaxen-haired maiden of eighteen, who climbed the steep path with the grace and agility of a gazelle. She was an artless little thing, and told me of her own accord the story of her simple love. Fritz was a soldier in the Emperor Wilhelm's army. He was now in garrison at Cologne. They hoped that he would soon get a lieutenancy, for he was brave and faithful, and then he would come home and marry her. She had saved up her dairy money till it amounted to quite a little purse, which she had sent him that it might help purchase his commission. Had I ever seen Fritz? No? He was handsome and good, and she loved him more than she could tell.

I listened to this prattle with the same amount of romantic interest that a proposition in Euclid would excite and congratulated myself that my old soul had so nearly disappeared. Every night the gray owl perched above me. I knew that Socrates was waiting to take possession of my body, and I yearned to open my bosom and receive that grand soul. Every night the detestable rat came and peered through the wires. His cool, contemptuous malice exasperated me strangely. I longed to reach out from beneath my cage and seize and throttle him, but I was afraid of the venom of his bite.

My own soul had by this time nearly wasted away, so to speak, through disciplined disuse. The owl looked down lovingly at me with his great placid eyes. A noble spirit seemed to shine through them and to say, "I will come when you are ready." And I would look back into their lustrous depths and exclaim with infinite yearning, "Come soon, oh Socrates, for I am almost ready!" Then I would turn and meet the devilish gaze of the monstrous rat, whose sneering malevolence dragged me back to earth and to earth's hatreds.

My detestation of the abominable beast was the sole lingering trace of the old nature. When he was not by, my soul seemed to hover around and above my body, ready to take wing and leave it free forever. At his appearance, an unconquerable disgust and loathing undid in a second all that had been accomplished, and I was still myself. To succeed in my experiment I felt that the hateful creature whose presence barred out the grand old philosopher's soul must be dispatched at any cost of sacrifice or danger.

"I will kill you, you loathsome animal!" I shouted to the rat; "and then to my emancipated body will come the soul of Socrates which awaits me yonder."

The rat turned on me his leering eyes and grinned more sardonically than ever. His scorn was more than I could bear. I threw up the side of the wire cage and clutched desperately at my enemy. I caught him by the tail. I drew him close to me. I crunched the bones of his slimy legs, felt blindly for his head, and when I got both hands to his neck, fastened upon his life with a terrible grip. With all the strength at my command, and with all the recklessness of a desperate purpose, I tore and twisted the flesh of my loathsome victim. He gasped, uttered a horrible cry of wild pain, and at last lay limp and quiet in my clutch. Hate was satisfied, my last passion was at an end, and I was free to welcome Socrates.

When I awoke from a long and dreamless sleep, the events of the night before and, indeed, of my whole previous life were as the dimly remembered incidents in a story read years ago.

The owl was gone but the mangled carcass of the rat lay by my side. Even in death his face wore its horrible grin. It now looked like a Satanic smile of triumph.

I arose and shook off my drowsiness. A new life seemed to tingle in my veins. I was no longer indifferent and negative. I took a lively interest in my surroundings and wanted to be out in the world among men, to plunge into affairs and exult in action.

Pretty Emma came up the bill bringing her basket. "I am going to leave you," said I. "I shall seek better quarters than the Schloss Schwinkenschwank."

"And shall you go to Cologne," she eagerly asked, "to the garrison where the Emperor's soldiers are?"

"Perhaps so—on my way to the world."

"And will you go for me to Fritz?" she continued, blushing. "I have good news to send him. His uncle, the mean old notary, died last night. Fritz now has a small fortune and he must come home to me at once."

"The notary," said I slowly, "died last night?"

"Yes, sir; and they say he is black in the face this morning. But it is good news for Fritz and me."

"Perhaps—" continued I, still more slowly "—perhaps Fritz would not believe me. I am a stranger, and men who know the world, like your young soldier, are given to suspicion."

"Carry this ring," she quickly replied, taking from her finger a worthless trinket. "Fritz gave it to me and he will know by it that I trust you."

My next visitor was the learned Calcarius. He was quite out of breath when he reached the apartment I was preparing to leave.

"How goes our metempsychosis, my worthy pupil?" he asked. "I arrived last evening from Bonn, but rather than spend another night with your horrible rodents, I submitted my purse to the extortion of the village innkeeper. The rogue swindled me," he continued, taking out his purse and counting over a small treasure of silver. "He charged me forty Groschen for a bed and breakfast."

The sight of the silver, and the sweet clink of the pieces as they came in contact in Professor Calcarius' palm, thrilled my new soul with an emotion it had not yet experienced. Silver seemed the brightest thing in the world to me at that moment, and the acquisition of silver, by whatever means, the noblest exercise of human energy. With a sudden impulse that I was unable to resist, I sprang upon my friend and instructor and wrenched the purse from his hands. He uttered a cry of surprise and dismay.

"Cry away!" I shouted; "it will do no good. Your miserly screams will be heard only by rats and owls and ghosts. The money is mine."

"What's this?" he exclaimed. "You rob your guest, your friend, your guide and mentor in the sublime walks of metaphysical science? What perfidy has taken possession of your soul?"

I seized the Herr Professor by the legs and threw him violently to the floor. He struggled as the gray rat had struggled. I tore pieces of wire from my cage, and bound him hand and foot so tightly that the wire cut deep into his fat flesh.

"Ho! Ho!" said I, standing over him; "what a feast for the rats your corpulent carcass will make," and I turned to go.

"Good Gott!" he cried. "You do not intend to leave me: No one ever comes here."

"All the better," I replied, gritting my teeth and shaking my fist in his face; "the rats will have uninterrupted opportunity to relieve you of your superfluous flesh. Oh, they are very hungry, I assure you, Herr Metaphysician, and they will speedily help you to sever the mysterious link that binds soul to living body. They well know how to loosen the individualized ego from the fleshly surroundings. I congratulate you on the prospect of a rare experiment."

The cries of Professor Calcarius grew fainter and fainter as I made my way down the hill. Once out of hearing I stopped to count my gains. Over and over again, with extraordinary joy, I told the thalers in his purse, and always with the same result. There were just thirty pieces of silver.

My way into the world of barter and profit led me through Cologne. At the barracks I sought out Fritz Schneider of Schwinkenschwank.

"My friend," said I, putting my hand upon his shoulder, "I am going to do you the greatest service which one man may do another. You love little Emma, the innkeeper's daughter?"

"I do indeed," he said. "You bring news of her?"

"I have just now torn myself away from her too ardent embrace."

"It is a lie!" he shouted. "The little girl is as true as gold."

"She is as false as the metal in this trinket," said I with composure, tossing him Emma's ring. "She gave it to me yesterday when we parted."

He looked at the ring and then put both hands to his forehead. "It is true," he groaned. "Our betrothal ring!" I watched his anguish with philosophical interest.

"See here," he continued, taking a neatly knitten purse from his bosom. "Here is the money she sent to help me buy promotion. Perhaps that belongs to you?"

"Quite likely," I replied, very coolly. "The pieces have a familiar look."

Without another word the soldier flung the purse at my feet and turned away. I heard him sobbing, and the sound was music. Then I picked up the purse and hastened to the nearest café to count the silver. There were just thirty pieces again.

To acquire silver, that is the chief joy possible to my new nature. It is a glorious pleasure, is it not? How fortunate that the soul, which took possession of my body in the Schloss, was not Socrates', which would have made me, at best, a dismal ruminator like Calcarius; but the soul that had dwelt in the gray rat till I strangled him. At one time I thought that my new soul came to me from the dead notary in the village. I know, now, that I inherited it from the rat, and I believe it to be the soul that once animated Judas Iscariot, that prince of men of action.

The Strange Confession Of A New York Physician—a Case

That

Has Puzzled The Medical Fraternity For Many Years Past

DR. JAMES HARWOOD, who died last week, stood for more than twenty years very near the head of the medical profession. His fame extended also to the other side of the water, and when traveling in Europe other celebrated physicians availed themselves of the opportunity of consulting him. On one of his Continental tours, Dr. James Harwood effected a most marvelous cure which soon made the rounds of the papers and helped materially in establishing his world-wide reputation. He succeeded in curing the Russian Prince Michalskovich of an almost hopeless form of monomania. What made the case of such interest to the medical profession was the extraordinary and strange means which the doctor had employed to effect the cure. Dr. James Harwood maintained, verbally and in print, that he had restored the prince to a sound mind by means of mesmerizing him. This occurred about twenty or thirty years ago, and mesmerism was then all the rage, and there were many intelligent persons who fully believed in all the wonderful things told of its power. Naturally, the case formed for a long time a fertile subject for discussion in medical circles and periodicals, and after a while, in view of the high respectability of the practitioner and the testimony corroborating it, the prince's strange case of insanity and Dr. James Harwood's wonderful cure was entered as a fact into the various medical annals and finally found also a place in the textbooks used in our medical schools and colleges.

But scientific men are always somewhat skeptical, and to this day some members of the medical profession continue to look with suspicion upon the doctor's account of the cure.

Six or seven years ago the prince himself paid a visit to this city. He had scarcely looked at his new quarters in the hotel when he was told that two celebrated New York physicians, father and son, begged the favor of an interview. When admitted, the older explained that he was a professor of medicine, and now engaged on an elaborate work on physiology, and that he would feel obliged if the prince would give him a detailed account of his own famous case, to be incorporated in the chapter on insanity. The prince graciously complied and, entering upon every particular connected with his cure, he ascribed it again to the effects of mesmerism. The aged professor thereupon ventured on letting an incredulous smile flit across his face. But the moment the prince had seen and interpreted this treacherous smile, the medical gentleman became aware of having been seized by the coat collar and deposited on the soft carpet of the corridor outside of the prince's door, where his son soon came rushing after him, followed by his hat and cane. There is a rumor in medical circles that this is the reason why the prince's curious case is not mentioned in a recently published great American work on physiology.

The original account of the marvelous cure of the insane prince as Dr. James Harwood first gave it reads as follows:

I was called to St. Petersburg to examine the case of Prince Michalskovich, who was suffering from a very curious mental affection. I found him raving in a language wholly unknown, at least to the attending physicians and several linguists who had been invited to his bedside. After having succeeded in allaying his brain fever, I was in hopes of hearing him resume the use of Russian, French, or English, in which he was in the habit of conversing, but he persisted in using his unintelligible gibberish. Otherwise he was quiet and inoffensive. His deportment toward his numerous serfs and servants was, in fact, wondrously gentle and courteous while, when sane, he exhibited always to them the most irascible temper, and treated them habitually brutally and cruelly. He began to show also an extraordinary preference for coarse clothing and frugal meats. One day he showed a desire to leave the palace. I instructed his attendants to give him as much liberty as possible, and to follow him only at a distance. In the evening these men reported that the prince had been at work all day in the shop of a carriage maker. He had gone into the shop and, without saying a word, had taken hammer and hatchet and assisted the workmen in making a carriage. The wheelwright said that he had let the prince have his way because he saw at once that he was a very skilled laborer. Early in the morning, the prince was at work again in the wheelwright's shop, and continued there until evening. In a week or two it became perfectly plain that the prince had the monomania of being nothing but a simple carriage maker. I tried at first to prevent him from going to the shop, but seeing that it distracted his mind only more, I consented to let him go on, trusting that something would occur which would lead his mind back into its proper channels.

I was very near fixing a day for my return to New York, and about to decide that the prince was an incurable lunatic, when my eyes fell on a paragraph in a medical journal speaking of the case of an insane journeyman in Tiflis, who imagined himself to be a powerful and wealthy prince. I read the account through a second time, feeling peculiarly impressed by the singular coincidences that this poor fellow was a carriage maker by trade, and that, while he had never been heard to speak anything but an obscure Georgian dialect of Mingrolia, and had always been known as a low and ignorant peasant, he was now heard in his ravings to make a fluent and cultured use of Russian, German, French, and English. It was this unexpected talking in foreign languages which had caused this journeyman's case to make the rounds of the papers. I could not help observing that it was exactly the same case as that of Prince Michalskovich, only inverted. The prince wanted to be a wheelwright; the wheelwright wanted to be a prince. The one had given up talking in civilized languages, and talked gibberish; the other had given up his gibberish, and talked Russian, English, and other tongues.

Naturally enough I took at once the necessary steps to have the man removed from the Tiflis to the St. Petersburg insane asylum. I claimed him there and found that the correspondence between his case and that of the prince was most surprising. After consulting the family of Prince Michalskovich, I had the fellow taken to the palace with all the pomp and ceremony that was due a prince, just out of sheer curiosity to see what the development would be. He confounded everybody. He took possession of the prince's private apartments as if he had occupied them all of his life. He greeted the parents, relatives, and friends of the prince by name, used the wardrobe, and ordered the servants, as if he were really the prince himself. The grace of his manners and the elegance with which he expressed himself in various languages were most astonishing, and withal he had the build, the hands, and features of a rough artisan. I put him to another test. I confronted him with the veritable prince in the carriage factory. He spoke to the prince patronizingly, even somewhat familiarly, but still preserving always a certain distance and showing at times unmistakable haughtiness. He did not seem to notice the fact that the prince gave him no answer in return to anything he said.

Thus another week or two passed by, and I had made no progress in the case of the prince, except that instead of one insane man I had now two on my hands. I was again on the point of abandoning the prince when one day a seedy-looking individual paid me a visit and offered to cure the prince instantly if I guaranteed that he should be paid well for his services. A thousand rubles was his price. I made the bargain with him, but put in the condition that I was to be present at every step of the operation.

At the appointed time I had the prince and the artisan in the palace. The mysterious stranger made me order them to sit side by side as closely as possible. Then he passed his hands over their faces, moving them continually to and fro as if mesmerizing the two men, who soon fell into a state of the most complete unconsciousness which I have ever witnessed. Thereupon he stripped them of every garment on their bodies, continuing all the time his mesmerizing manipulations. Suddenly the prince and the artisan felt simultaneously a heavy shock, after which their bodies lay as rigid as in death.

"I have caused their spirits to depart from them," said the stranger, in an explanatory tone. "Now I shall order the spirit of this one to enter the body of the other, and shall make the spirit of the other come into this body."

He stretched out his hands and commanded, "Now!"

The very instant he uttered the word the two bodies shook and trembled.

The stranger then came up to me and said, "Have you the money ready for me? Take it out, if you please, and hold it in your hand. The moment I order the bodies to move, and you hear the prince talk Russian and see him act like a prince, while the journeyman looks around bewildered and abashed as a peasant would, you will know that I have performed the cure, and you must slip the thousand rubles into my hand. I have not the time to wait another moment. Are you ready? All right, then. Now!"

Instantly the prince jumped up in full possession of his mind, called in Russian for his servants, and stepped up to me and demanded an explanation of the strange condition in which he had been placed—he was still naked. The Tiflis artisan looked as stupid and terrified as he could. To make the matter short, the stranger had indeed effected a perfect cure; both men were again of a sound mind.

I turned to the stranger and handed him his thousand rubles, adding that I should like to see him at my hotel and converse with him about the strange methods of his cure. But he shook his head and stole quietly out of the room.

Mesmerism or no mesmerism, said Dr. James Harwood, in conclusion, this is the way Prince Michalskovich was cured, and this is all that I have to state in regard to it.

SUCH was the great sensation of about twenty years ago. The papers were full of it, everybody was full of it, and nobody knew what to make of it. Spiritualists and mesmerizers, of course, were proud of it, and felt triumphant. There was, in fact, no possibility of denying the case. Prince Michalskovich was a well-known character, and his prolonged sickness and final monomania of believing himself a simple carriage maker were well-authenticated facts. Also the Tiflis artisan's sudden and wonderful gift of tongues was attested to by several eminent physicians who had examined and treated him in the early stages of his insanity.

Several years ago, when the doctor was still residing in this city, he was urged by a colleague to come forward with the real facts of the case, and thereby save the honor of the profession as well as his own. The doctor acceded in so far to the demand that he deposited with a friend a full account of the case, taking a solemn promise that the same should not be published before the prince and he himself were dead and buried. This confession is now laid before the world, and though rather strange and unexpected, yet it cannot be said of the doctor that the course he pursued was entirely unjustifiable. He says:

The medical world will not be very much surprised when they read that I acknowledge the stranger's cure of the prince and the artisan to have been a deception, and that I knew it at the time to have been such, because the whole scene was of my own devising. From the first I have always felt confident that the better class of physicians would not fail to perceive that my making use of a magician to cure an insane man was one of those tricks to which a physician has sometimes to resort in the treatment of the insane, especially of those who are laboring under a great self-deception. But the great credulity of the masses took me by surprise. In a fortnight all the papers had copied the nonsensical account of the prince's cure, and I was at once besieged with thousands of letters from medical men and associations, and everybody I met wanted me to tell him the story over again. I could not do otherwise than give the same version of the case to all inquirers, for in cures of insanity effected by deception it is of the utmost importance that the patient does never discover that his physician only deceived him. Here is a case in point: A merchant once imagined that he had a watch in his head, and that the never-ceasing ticking prevented him from thinking and sleeping. When placed in an asylum, he was told that he had to submit to the very dangerous operation of having the watch got out of his head. He was chloroformed, a deep cut was made into a safe spot, and when he awoke a small blood-stained mechanism was shown and given him with the assurance that it had been taken out of his head. He believed it, and was cured. He resumed his commercial pursuits and made a great fortune.

But now comes the terrible sequel. One day, after ten or twenty years, he met in the street the physician who had cured him of his insanity. The doctor, attempting to joke with him about the former monomania, said laughingly, "What a funny fancy that was of yours to think that you carried a watch in your brain. Don't you now sometimes laugh at yourself when you recollect it?"

The merchant looked at him in surprise. "Then you did not cut it out of my head! I thought so. I always thought so. I never believed it. I heard it tick all the time just the same. Now put your ear right here. How it ticks! Don't you hear it tick? Tick, tick, tick!"

The man was insane again. Nothing could cure him now, for nobody could deceive him again.

I determined to manage my own case better. I resolved to tell my secret to nobody in order to be sure that nobody would tell it again. If a single word of it had at any time crept out, it would have reached the prince by some means or other, sooner or later. Luckily, the mystery was deepened by the strange coincidence of the Tiflis carriage maker, and whenever I could, I drew the attention of medical men away from my trick with the magician to the real and well-authenticated fact of the wonderful similarity and simultaneousness of the insanity of the artisan and the prince. It cannot be denied that the case is one of the most wonderful occurrences in medical practice, and I shall proceed to present it, shorn of everything but what actually happened.

Prince Michalskovich's nurse was a beautiful Georgian woman whose own child was made his playfellow, and shared his tuition until he was about fourteen years of age. Then the prince went on his travels, and his foster brother returned with his mother to the district of Mingrolia, in Russian Georgia, where he learned the trade of a carriage maker. The prince loved the nurse and his foster brother dearly, and he spent many a season in the Transcaucasian mountains in order to be near them. He was a very active youth, fond of hunting and fishing, and taking delight in mechanical employments, he spent many a day in the wheelwright's shop working at the side of his foster brother.

Unfortunately the prince fell in love with the same young peasant woman whom his foster brother was about to marry. When the young artisan discovered the unfaithfulness of his betrothed he had a violent scene with the prince and the very day, as misfortune would have it, the young woman died, suddenly and unexpectedly. Her two lovers were then equally wretched. Both left Mingrolia. The wheelwright went to Tiflis and worked there under an assumed name to prevent the prince from finding him again. The prince returned to St. Petersburg and it was soon discovered that he was subject to abnormal fits of melancholia. His yearning for his foster brother, coupled with the unfortunate termination of his love affair, finally developed the peculiar form of insanity already described.

The young artisan continued at work in Tiflis. He spoke to no one of his past history and formed no friendships among his fellow workmen. The day's work done, he returned at night to his hovel where he spent the remainder of the day in strict seclusion. He became insane, too, imagining on a sudden to be his own foster brother, Prince Michalskovich. This considering one's self to be some great and powerful person is quite a common form of monomania, and hence the artisan's case would hardly have attracted attention if it had not been coupled with his surprising use of foreign languages. He had never been known to speak anything but his peasant dialect, and nobody suspected to think that he was a man of education and refinement. The physician who attended him at once pronounced his case the great marvel of the age. The story of the sudden gift of tongues traveled over the world, and at last reached me also. You know how I sent for the young man and finally took him into the palace. He was instantly recognized as the foster brother of the prince. One day he startled me by inquiring for his brother Paul. I perceived at once that his reason was dawning again, and by careful treatment I succeeded in restoring him to his senses.

When I told him of the prince's mental malady and of the wonderful coincidence of his own, the young man's affection for the prince revived and he was full of ardor to assist me to set up the situation by which I hoped to bring about a cure. In the course of a conversation he told me one day some anecdotes illustrative of the gross superstition of the prince. He mentioned, among other things, the prince's strong faith in the transmigration of souls, and his firm belief in the pretensions of persons like Cagliostro or Joseph Balsamo. I saw at once an opportunity for another experiment, and I quickly concocted the scene with the magician which I described. When the prince came to his senses again, he listened to my account of his wonderful cure by the mysterious stranger in perfect good faith, and when he saw his foster brother and heard him say that he had also been cured that very moment, he was perfectly satisfied, and acted again the sane man.

The notoriety which the prince attained through the widespread accounts of his wonderful cure flattered him very much, and if anybody had insinuated to him that he had been duped, he would have regarded it as a great insult. It is rumored that some New York physician was made to feel his wrath when he called on the prince and wished him to understand that he believed that I had only deceived him. Of course, if somebody had told the prince that he had heard me say that his cure was effected simply by a medical trick, the consequences would have been of a very serious nature.

Such is Dr. James Harwood's confession. Does it justify him?

"MY notions about soul's influence on soul," said Dr. Richards of Saturday Cove to me one day last September, "are a little peculiar. I don't make a practice of giving 'em away to the folks around here. The cove people hold that when a doctor gets beyond jalap and rhubarb he's trespassing on the parson's property. Now it's a long road from jalap to soul, but I don't see why one man mightn't travel as well as another. Will you oblige me with a clam?"

I obliged him with a clam. We were sitting together on the rocks, fishing for tomcod. Saturday Cove is a small watering place a few miles below Belfast, on the west shore of Penobscot bay. It apparently derives its name from a belief, generally entertained by the covers, that this spot was the final and crowning achievement of the Creator before resting on the seventh day. The cove village consists of a hotel, two churches, several stores, and a graveyard containing former generations of Saturdarians. It is a favorite gibe among outsiders, who envy the placid quiet of the place, that if the population of the graveyard should be dug up and distributed through the village, and the present inhabitants laid away beneath the sod, there would be no perceptible diminution in the liveliness of the settlement. The cove proper abounds with tomcod, which may be caught with clams.

"Yes," continued Dr. Richards, as he forced the barb of his jig hook into the tender organism of the clam, "my theory is that a strong soul may crowd a weak soul out of the body which belongs to the weak soul and operate through that body, even though miles away and involuntarily. I believe, moreover, that a man may have two souls, one his own by right and the other an intruder. In fact I know that this is so and it being so what becomes of your moral responsibility? What, I ask, becomes of your moral responsibility?"

I replied that I could not imagine.

"Your doctrine of moral responsibility," said the doctor sternly, as if it were my doctrine and I were responsible for moral responsibility, "isn't worth this tomcod." And he took a small fish off his hook and contemptuously tossed it back into the cove. "Did you ever hear of the case of the Dow twins?"

I had never heard of the case of the Dow twins.

"Well," resumed the doctor, "they were born into the family of Hiram Dow, thirty years or more ago, in the red farmhouse just over the hill back of us. My predecessor, old Dr. Gookin, superintended their birth, and has often told me the circumstances. The Dow twins came into the world bound back to back by a fleshy ligature which extended half the length of the spinal processes. They would probably have traveled through life in an intimate juxtaposition had the matter depended on your great city surgeons—your surgeons who were afraid to disconnect Chang and Eng, and who discussed the operation till the poor fellows died without parting company. Old Dr. Gookin, however, who hadn't attempted anything for years in the surgical line, more than to pull a tooth or to cut out an occasional wen, calmly went to work and sharpened up his rusty old operating knife and slashed and gashed the twins apart before they had been three hours breathing. This promptitude of Gookin's saved the Dow twins a good deal of inconvenience."

"I should think so."

"And yet," added the doctor, reflectively, "perhaps it might have been better for 'em both if they hadn't been separated. Better for Jehiel, especially, since he wouldn't have been put in a false position. Then, on the other hand, my theory would have lacked the confirmation of an illustrative example. Do you want the story?"

"By all means."

WELL, Jacob and Jehiel grew up healthy, strapping boys, like as two peas physically, but not mentally and morally. Jehiel was all Dow—slow, slow-witted, melancholy inclined, and disposed to respect the Ten Commandments. Jake, he had his mother's git-up-and-git—she was a Fox of Fox Island—and was into mischief from the time he was tall enough to poke burdock burrs down his grandmother's back. Dr. Gookin watched the development of the twins with great interest. He used to say that there was an invisible nerve telegraph between Jake and Jehiel. Jehiel seemed to sense whenever Jacob was up to any of his pranks. One night, for instance, when Jake was off robbing a hen roost, Jehiel sat up in bed in his sleep and crowed like a frightened cock until the whole family was aroused.

I came here and opened my office about ten years ago. At that time Jehiel had grown into a steady, tolerably industrious young man, prominent in the Congregational Church, and so sober and decorous that the village people had trusted him with the driving of the town hearse. When I first knew him he was courting a young woman by the name of Giles, who lived about seven miles out in the country. Jehiel was a tin knocker by trade, and a more pious, respectable, reliable tin knocker you never saw.

Jake had turned out very differently. By the time he was twenty-one he had made Saturday Cove too hot to hold him, and everybody, including his twin Jehiel, was glad when he enlisted in a Maine regiment. I never saw Jake in my life, for I came here after he had departed, but I had a pretty good notion of what a reckless, loud-mouthed, harum-scarum reprobate he must have been. After the war he drifted into the western country, and we heard of him occasionally, first as a steamboat runner at St. Louis, then in jail at Jefferson for swindling a blind Dutchman, then as a gambler and rough in Cheyenne, and finally as a debt beat in Frisco. You could tell pretty well when Jake was in deviltry by watching the actions of Jehiel. At such times, Jehiel was restless. Knocked tin with an uneasy impatience that wasn't natural with him, was as solemn and glum as an undertaker.

He was impatient and short to the people of Saturday Cove, and evidently had to struggle hard to be good. It seemed as if Dr. Gookin's knife had severed the physical bond but not the mental one.

The strangest thing of all was in regard to Jehiel's attentions to the young woman named Giles. She was a sober, demure, church-going person, whom Jacob had never been able to interest, but who, as everybody said, would make an excellent helpmate for Jehiel. He seemed to care a good deal for her in his steady, slow way and made a point twice a week of driving over to bring her to prayer-meeting at the cove. But when one of his odd spells was on him he forsook her altogether, and weeks would go by, to her great distress, without his appearing at the Giles gate. As Jake went from bad to worse these periods of indifference became more frequent and prolonged, and occasioned the young woman named Giles much misery and a good many tears.

One fine afternoon in the summer of 1871, Jacob Dow, as we afterward learned, was shot through the heart by a Mexican in a drunken row at San Diego. He sprang high into the air and fell upon his face, and when they laid him away a good Catholic priest said mass for the repose of his soul.

That same afternoon, as it happened, old Dr. Gookin was to have been buried in the graveyard yonder. He had died a day or two before, at an extreme age, but in the full possession of his faculties, and one of the last remarks he made was to express regret that he would be unable to follow the career of the Dow twins any further.

It became Jehiel's melancholy duty to harness up his hearse on account of old Dr. Gookin's funeral, and as he dusted the plumes and polished the ebony panels of the vehicle, his thoughts naturally recurred to the great service which that excellent physician had rendered him in early youth. Then he thought of his twin brother Jacob, and wondered where he was and how he prospered. Then his eyes wandered over the hearse, and he felt a dull pride in its creditable appearance. It looked so bright and shiny in the sun that he resolved, as it still wanted a couple of hours of the time appointed for the funeral, to drive it over to the Giles farm and fetch his sweetheart to the village on the box with him. The young woman named Giles had frequently ridden with Jehiel on the hearse, her demure features and sober apparel detracting nothing from the respectable solemnity of the equipage.

Jehiel drew up in state to the door of his betrothed, and she, not at all reluctant to enjoy the mild excitement of a funeral, mounted to the box and settled herself comfortably beside him. Then they started for Saturday Cove, and jogged along on the hearse, discoursing affectionately as they went.

Miss Giles affirms that it was at the third apple tree next the stone wall of Hosea Getchell's orchard, just opposite the bars leading to Mr. Lord's private road, that a sudden and most extraordinary change came over Jehiel. He jumped, she says, high into the air and landed sprawling in the sandy road alongside the hearse, yelling so hideously that it was with difficulty that she held the frightened horses. Picking himself up and uttering a round oath ( something that had never before passed the virtuous lips of Jehiel), he turned his attention to the horses, kicking and beating them until they stood quiet. He next proceeded to cut and trim a willow switch at the roadside, and putting his decent silk hat down over one eye, and darting from the other a surly glance at the astonished Miss Giles, he climbed to his seat on the hearse.

"Dow!" said she, "what does this mean?"

"It means," he replied, giving the horses a vicious cut with his switch, "that I have been goin' slow these thirty year, and now I'm goin'to put a little ginger in my gait. Ge'long!"

The hearse horses jumped under the unaccustomed lash and broke into a gallop. Jehiel applied the switch again and again, and the dismal vehicle was soon bumping over the road at a tremendous pace, Jehiel shouting all the time like a circus rider, and Miss Giles clinging to his side in an agony of terror. The people in the farmhouses along the way rushed to doors and windows and gazed in amazement at the unprecedented spectacle. Jehiel had a word for each—a shout of derision for one, a blast of blasphemy for another, and an invitation to ride for a third—but he reined in for nobody, and in a twinkling the five miles between Hosea Cetchell's farm at Duck Trap at the village at Saturday Cove had been accomplished. I think I am safe in saying that never before did hearse rattle over five miles of hard road so rapidly.

"Oh, Jehiel, Jehiel," said Miss Giles, as the hearse entered the village, "are you took crazy of a sudden?"

"No," said Jehiel curtly, "but my eyes are open now. Ge'long, you beasts! You get out here; I'm going to Belfast."

"But, Jehiel, dear," she protested, with many sobs, "remember Dr. Gookin."

"Dang Gookin!" said Jehiel.

"And for my sake," she continued. "Dear Jehiel, for my sake."

"Dang you, too!" said Jehiel.

Drawing up his team in magnificent style before the village hotel, he compelled the weeping Miss Giles to alight, and then, with an admirable imitation of the war whoop of a Sioux brave, started his melancholy vehicle for Belfast, and was gone in a flash, leaving the entire population of Saturday Cove in a state of bewilderment that approached coma.

The remains of the worthy Dr. Gookin were borne to the graveyard that afternoon upon the shoulders of half a dozen of the stoutest farmers in the neighborhood. Jehiel came home long after midnight, uproariously intoxicated. The revolution in his character had been as complete as it was sudden. From the moment of Jacob's death, he was a dissipated, dishonest scoundrel, the scandal of Saturday Cove, and the terror of quiet respectable folks for miles around. After that day he never could be persuaded to speak to or even to recognize the young woman named Giles. She, to her credit, remained faithful to the memory of the lost Jehiel. His downward course was rapid. He gambled, drank, quarreled, and stole; and he is now in state prison at Thomaston, serving out a sentence for an attempt to rob the Northport Bank. Miss Giles goes down every year in the hopes that he will see her, but he always refuses. He is in for ten years.

"AND he, does he feel no remorse for what he did?" I asked.

"See here," said Dr. Richards, turning suddenly and looking me square in the face. "Do you think of what you are saying? Now I hold that he is as innocent as you or I. I believe that the souls of the twins were bound by a bond which Dr. Gookin's knife could not dissect. When Jacob died, his soul, with all its depravity, returned to its twin soul in Jehiel's body. Being stronger than the Jehiel soul, it mastered and overwhelmed it. Poor Jehiel is not responsible; he is suffering the penalty of a crime that was clearly Jake's."

My friend spoke with a good deal of earnestness and some heat, and concluding that Jehiel's personality was submerged. I did not press the discussion. That evening, in conversation with the village clergyman, I remarked:

"Strange case, that of the Dow twins."

"Ah," said the parson, "you have heard the story. Which way did the doctor end it?"

"Why, with Jehiel in jail, of course. What do you mean?"

"Nothing," replied the parson with a faint smile. "Sometimes when he feels well disposed toward humanity, the doctor lets Jehiel's soul take possession of Jacob and reform him into a pious, respectable Christian. In his pessimistic moods, the story is just as you heard it. So this is one of his Jacob days. He should take a little vacation."

PROFESSOR Daniel Dean Moody of Edinburgh, a gentleman equally well known as a profound psychologist and as an honest and keen-eyed investigator of the phenomena sometimes called spiritualistic, visited this country not many months ago and was entertained in Boston by Dr. Thomas Fullerton at his delightful home on Mount Vernon Street. One evening when there were present in Dr. Fullerton's parlors, besides himself and his Scotch guest, Dr. Curtis of the medical school of the Boston University, the Reverend Dr. Amos Cutler of the Lynde Street Church, Mr. Magnus of West Newton, three ladies, and the writer, the conversation turned to subjects of an occult character.

"There once lived in Aberdeen," said Professor Moody, "a medium named Jenny McGraw, of slender intellectuality, but of remarkable psychic strength. Two hundred years ago you good people of Boston would have hanged Jenny for a witch. I have seen in her cottage materialization for which I could not and cannot account by any hypothesis of deception or of hallucination. I have seen forms come forth, not from any cabinet or trick closet, but extruded before my eyes from the person of Jenny herself, hanging nebulous in the air for a moment and then slowly taking corporate shape. That there was no vulgar trick about this I am willing to stake my scientific reputation. One night Plato himself, or an eidolon claiming to be Plato, emerged from Jenny McGraw's bosom and conversed with me for full fifteen minutes upon the duality of the idea, the medium, in the meanwhile, remaining entranced."

Dr. Fullerton exchanged a significant glance with his wife. Their guest intercepted it and said:

"You don't believe me? No wonder."

"Not that," rejoined Dr. Fullerton. "Your testimony as a scientific observer is worthy of all possible respect. But what became of Jenny McGraw?"

"She was a dull, unsympathetic young woman, hardly to be classed as a rational being. So far from becoming interested in these wonderful manifestations exhibited through her organization, she was excessively annoyed by them, and I believe she finally left Scotland to escape the troublesome spirits and the still more troublesome mortals who flocked to her cottage and sadly interfered with her washing, ironing, and baking."

"A Yankee girl," said Mr. Magnus, "would have turned such powers to account and have made her fortune."

"Jenny McGraw," replied Professor Moody, "whom I believe to be the only medium in the world capable of producing materializations in the broad light and independently of her surroundings, was thrifty enough, like all Scotchwomen, but she hadn't the intelligence to recognize the opportunity. She was frequently advised to go before the public. Advice is wasted on the Scotch. I don't know where she is at present."

Dr. Fullerton again glanced at his wife. Mrs. Fullerton arose and touched a bell.

The door soon opened, and there appeared a lumpy, red-haired domestic, who curtsied awkwardly as she entered the room.

"Did ye rang, ma'am?" she asked.

"Jenny," said Mrs. Fullerton, "here is an old friend of yours from Scotland."

The girl showed no sign of surprise. Scarcely a shade of recognition passed over her stupid countenance as she walked sullenly up to the professor and sullenly took his extended hand.

"I didna ken ye was cam to America, Maister Moody," she said, and looked around as if she would be glad to escape the learned company.

"Now, with your permission, Mrs. Fullerton," said the professor, looking over Jenny McGraw's shoulder toward his hostess, "we will ask the young woman if she will kindly assist us in an investigation which we purpose to make."

Jenny looked up suspiciously and turned her small, dull eyes from her master to her mistress, and from her mistress to the door.

"I'm na ower fond of sic investigatin'," she stolidly remarked, "an' it gies me a pain in the breast to brang oot the auld ghaists, as ye na doot remember wull, Maister Moody."

For a long time the girl stubbornly refused to renew her relations with the mysterious yonder. I have forgotten what argument or plea it was that at last won her to a reluctant consent. I have not forgotten what followed.

The room was as light as the full blaze of five gas jets could make it. Under this blaze, and surrounded by the partly amused, partly skeptical company, jenny was seated in a Turkish easy chair. She did not form an attractive picture, short, squat, sandy, freckled, and peevish-eyed as she was. "Good Lord!" I whispered to a neighbor. "Do glorified spirits choose such a channel as that when they wish to come back to us?"

"Hush!" said Professor Moody. "The girl is passing into a trance."

The swinish eyes opened and closed. A sluggish convulsion fluttered across the flabby cheeks. A sigh or two, a nervous twitching of her chair, breathing heavily.

"Ineffectively simulated coma," whispered Dr. Curtis to me, "and not the work of an artist. This is a farce."

For fifteen or twenty minutes we sat in patience, the stillness broken only by the rough respiration of the girl. Then one or two of the party began to yawn, and the hostess, fearing that the experiment was becoming a bore, moved as if to break up the circle. But Professor Moody raised his hand in protest. Before he dropped it he made a rapid gesture which directed all our eyes toward Jenny McGraw.

Her head and bust seemed to be enveloped in a dim, thin film of opalescent vapor, which floated free about her, yet was fixed at one point, as a wreath of blue smoke hangs at the end of a good cigar. The point of attachment appeared to be in the neighborhood of Jenny's heart. She had stopped breathing loudly, and was as pale as the dead; but her face was no whiter than that of Dr. Curtis. I felt his hand groping for mine. He found it and clutched it till it was numb.

While we watched, the vapor that proceeded from Jenny's bosom grew in volume and became opaque. It was like a dark, well-defined cloud, floating before our eyes, here gathering itself in and extending itself there, till at last the shape was perfect.

You have seen a dim, meaningless object under a lens gradually define itself as it was brought into focus, and suddenly stand out clear and sharp. Or, better, you have seen at a shadow pantomime a vague, amorphous cloudiness intensify and take shape as the person approached the screen, until it became a perfect silhouette. Now, imagine the silhouette stepping forth into your presence a solidified fact, and you get some idea of the marvelous transition by which this shadow from a world we know not of stepped forth into the midst of our little company.

I looked across the room at the Reverend Dr. Cutler. He was clasping his forehead with both hands. I have never seen a more striking picture of mingled horror, terror, and perplexity.

The newcomer was a man of twenty-eight or thirty, of fine features and dignified bearing. He made a courteous bow to the assemblage, but when he saw that Professor Moody was about to speak put his finger to his lips and glanced back uneasily at the medium. I fancied that an expression of disgust stole over his handsome countenance when he perceived how unlovely was the gateway through which he had returned to earth. Nevertheless, he kept his eyes fixed upon Jenny McGraw's pallid face and folded his arms as if waiting.

We were now thoroughly under the spell of this mysterious happening. With eager expectation, but without surprise, we saw again the phenomena of the cloud, the shadow, the concentration, and the presence.

Slowly out of the white mist and nebulous shadow there took form the most beautiful woman that mortal eyes ever beheld. It was a woman—a living, breathing woman, her magnificent lips slightly parted, her bosom rising and falling beneath a garment of wonderfully woven texture, her glorious black eyes shining upon us till our heads swam and our thoughts reeled. It would be easier to fathom the secret of her being than to describe the unearthly beauty that startled and awed us.

The first corner unfolded his arms, and with the tenderness of a lover and the deference due a queen, took the shapely white hand of the marvelous lady and led her forth to the middle of the room. She said no word, but suffered herself to be guided by his hand, and stood like an empress scanning our faces and habiliments with a puzzled curiosity in which it was possible to detect the slightest trace of disdain. He spoke at last in a low voice.

"Friends," he slowly said, "a great love carried one who was lately a mortal into the presence of a goddess. A greater good fortune befell him than his small sacrifices had earned. I cannot speak more plainly. Hear our entreaty and grant it without questioning. There is here a servant of the church, duly qualified to pronounce the only words that can crown a love like mine. That love reached back over centuries to meet its object, and was sealed by a willing death. We come from another world to ask to be joined in wedlock according to the forms of this world."

Strange as it may seem, the preceding events had so attuned our consciousness to the spirit of the surroundings that we heard this extraordinary speech without amazement. And when Mr. Magnus of West Newton, who would preserve his cool, matter-of-fact manner in the company of archangels, audibly whispered, "Eloped, by Jove, from the spirit land!" His words jarred harshly in our ears.

The Reverend Dr. Amos Cutler displayed most strikingly the effect of the glamor that had been thrown over our nineteenth-century common sense. That pious man rose from his chair with a dazed and helpless look in his face, and, like one walking in his sleep, advanced toward the couple.

Raising his hand to command silence, he solemnly and deliberately asked the questions that by usage of the church are preliminary to the marriage rite. The man responded in a clear, triumphant tone. The bride answered only by a slight inclination of her beautiful head.

"Then," continued Dr. Cutler, "in the presence of these witnesses, I pronounce you man and wife. And God forgive me," he added, "for lending myself to the Devil's works by the sacrilege of this act."

One by one we passed up to take the bridegroom's hand and salute the bride. His hand was like the hand of a marble statue, but a radiant smile brightened his face. At a whispered suggestion from him, she bent her regal head, and allowed each one of us to kiss her cheek. It was soft and blood-warm.

When Dr. Cutler saluted her she smiled for the first time and, with a rapid, graceful movement detached from her black hair a great pearl and put it in his hand. He gazed at it a moment and, then on a sudden impulse, flung it into the open grate. In the hot blaze, Dr. Cutler's wedding fee whitened, calcined, crumbled, and disappeared.

Then the bridegroom led his wife back to the chair where the medium still sat entranced. He clasped her close in his arms. Their melting forms interblended in shadowy vapor, and, fading slowly away, this newly married couple found their nuptial pillow in the bosom of Jenny McGraw.

ONE day after Professor Moody had left Boston, I went to the Athaeneum Library in search of certain facts and dates regarding the Franco-Prussian war. While turning over the leaves of a bound file of the London Daily News for 1871 my eyes happened to fall upon the following paragraph:

The Vienna Freie Presse says that at four o'clock in the afternoon of July 12 a young man of good appearance shot himself through the heart in the east corridor of the Imperial Gallery. It was at the hour of closing the gallery, and the young man had been warned by an attendant that he must depart. He was standing motionless before Herr Hans Makart's fine picture of "Cleopatra's Barge," and paid no heed to the admonition. When it was repeated more emphatically he pointed in an absent manner to the painting, and having remarked, "Is not that a woman worth dying for!" drew a pistol and fired with fatal effect.

There is no clue to the suicide's individuality except that afforded at the Golden Lamb Hotel, where he was registered simply as "Cotton." He had been in Vienna several weeks, had spent money freely, and had frequently been observed at the Imperial Gallery, always before this picture of Cleopatra. The unfortunate youth is believed to have been insane.

I made a careful copy of this brief story, and sent it, without comment, to the Reverend Dr. Cutler. A day or two later he returned it with a note.

"The events of that night at Dr. Fullerton's," he wrote, "are to me as the events of a dimly remembered dream. Pardon me if I say that it will be a kindness to let me forget them altogether."

Practical Working of Materialization in Maine. A Strange Story from Pocock Island—A Materialized Spirit that Will not Go back. The First Glimpse of what May yet Cause very Extensive Trouble in this World.

WE are permitted to make extracts from a private letter which bears the signature of a gentleman well known in business circles, and whose veracity we have never heard called in question. His statements are startling and well-nigh incredible, but if true, they are susceptible of easy verification. Yet the thoughtful mind will hesitate about accepting them without the fullest proof, for they spring upon the world a social problem of stupendous importance. The dangers apprehended by Mr. Malthus and his followers become remote and commonplace by the side of this new and terrible issue.

The letter is dated at Pocock Island, a small township in Washington County, Maine, about seventeen miles from the mainland and nearly midway between Mt. Desert and the Grand Menan. The last state census accords to Pocock Island a population of 311, mostly engaged in the porgy fisheries. At the Presidential election of 1872 the island gave Grant a majority of three. These two facts are all that we are able to learn of the locality from sources outside of the letter already referred to.

The letter, omitting certain passages which refer solely to private matters, reads as follows:

But enough of the disagreeable business that brought me here to this bleak island in the month of November. I have a singular story to tell you. After our experience together at Chittenden I know you will not reject statements because they are startling.

My friend, there is upon Pocock Island a materialized spirit which (or who) refuses to be dematerialized. At this moment and within a quarter of a mile from me as I write, a man who died and was buried four years ago, and who has exploited the mysteries beyond the grave, walks, talks, and holds interviews with the inhabitants of the island, and is, to all appearances, determined to remain permanently upon this side of the river. I will relate the circumstances as briefly as I can.

John Newbegin

IN April, 1870, John Newbegin died and was buried in the little cemetery on the landward side of the island. Newbegin was a man of about forty-eight, without family or near connections, and eccentric to a degree that sometimes inspired questions as to his sanity. What money he had earned by many seasons' fishing upon the banks was invested in quarters of two small mackerel schooners, the remainder of which belonged to John Hodgeson, the richest man on Pocock, who was estimated by good authorities to be worth thirteen or fourteen thousand dollars.

Newbegin was not without a certain kind of culture. He had read a good deal of the odds and ends of literature and, as a simple-minded islander expressed it in my hearing, knew more bookfuls than anybody on the island. He was naturally an intelligent man; and he might have attained influence in the community had it not been for his utter aimlessness of character, his indifference to fortune, and his consuming thirst for rum.

Many yachtsmen who have had occasion to stop at Pocock for water or for harbor shelter during eastern cruises, will remember a long, listless figure, astonishingly attired in blue army pants, rubber boots, loose toga made of some bright chintz material, and very bad hat, staggering through the little settlement, followed by a rabble of jeering brats, and pausing to strike uncertain blows at those within reach of the dead sculpin [a species of fish] which he usually carried round by the tail. This was John Newbegin.

AS I have already remarked, he died four years ago last April. The Mary Emmeline, one of the little schooners in which he owned, had returned from the eastward, and had smuggled, or "run in" a quantity of St. John brandy. Newbegin had a solitary and protracted debauch. He was missed from his accustomed walks for several days, and when the islanders broke into the hovel where he lived, close down to the seaweed and almost within reach of the incoming tide, they found him dead on the floor, with an emptied demijohn hard by his head.

After the primitive custom of the island, they interred John Newbegin's remains without coroner's inquest, burial certificate, or funeral services, and in the excitement of a large catch of porgies that summer, soon forgot him and his friendless life. His interest in the Mary Emmeline and the Prettyboat recurred to John Hodgeson; and as nobody came forward to demand an administration of the estate, it was never administered. The forms of law are but loosely followed in some of these marginal localities.

WELL, my dear ———, four years and four months had brought their quota of varying seasons to Pocock Island when John Newbegin reappeared under the following circumstances:

In the latter part of last August, as you may remember, there was a heavy gale all along our Atlantic coast. During this storm the squadron of the Naugatuck Yacht Club, which was returning from a summer cruise as far as Campobello, was forced to take shelter in the harbor to the leeward of Pocock Island. The gentlemen of the club spent three days at the little settlement ashore. Among the party was Mr. R——— E———, by which name you will recognize a medium of celebrity, and one who has been particularly successful in materializations. At the desire of his companions, and to relieve the tedium of their detention, Mr. E——— improvised a cabinet in the little schoolhouse at Pocock, and gave a séance, to the delight of his fellow yachtsmen and the utter bewilderment of such natives as were permitted to witness the manifestations.

The conditions appeared unusually favorable to spirit appearances and the séance was upon the whole perhaps the most remarkable that Mr. E———ever held. It was all the more remarkable because the surroundings were such that the most prejudiced skeptic could discover no possibility of trickery.

The first form to issue from the wood closet which constituted the cabinet, when Mr. E———had been tied therein by a committee of old sailors from the yachts, was that of an Indian chief who announced himself as Hock-a-mock, and who retired after dancing a "Harvest Moon" pas seul, and declaring himself in very emphatic terms, as opposed to the present Indian policy of the Administration. Hock-a-mock was succeeded by the aunt of one of the yachtsmen, who identified herself beyond question by allusion to family matters and by displaying the scar of a burn upon her left arm, received while making tomato catsup upon earth. Then came successively a child whom none present recognized, a French Canadian who could not talk English, and a portly gentleman who introduced himself as William King, first Governor of Maine. These in turn re-entered the cabinet and were seen no more.

It was some time before another spirit manifested itself, and Mr. E———gave directions that the lights be turned down still further. Then the door of the wood closet was slowly opened and a singular figure in rubber boots and a species of Dolly Varden garment emerged, bringing a dead fish in his right hand.

THE city men who were present, I am told, thought that the medium was masquerading in grotesque habiliments for the more complete astonishment of the islanders, but these latter rose from their seats and exclaimed with one consent: "It is John Newbegin!" And then, in not unnatural terror of the apparition they turned and fled from the schoolroom, uttering dismal cries.

John Newbegin came calmly forward and turned up the solitary kerosene lamp that shed uncertain light over the proceedings. He then sat down in the teacher's chair, folded his arms, and looked complacently about him.

"You might as well untie the medium," he finally remarked. "I propose to remain in the materialized condition."

And he did remain. When the party left the schoolhouse among them walked John Newbegin, as truly a being of flesh and blood as any man of them. From that day to this, he has been a living inhabitant of Pocock Island, eating, drinking, (water only) and sleeping after the manner of men. The yachtsmen who made sail for Bar Harbor the very next morning, probably believe that he was a fraud hired for the occasion by Mr. E———. But the people of Pocock, who laid him out, dug his grave, and put him into it four years ago, know that John Newbegin has come back to them from a land they know not of.

THE idea, of having a ghost—somewhat more condensed it is true than the traditional ghost—as a member was not at first overpleasing to the 311 inhabitants of Pocock Island. To this day, they are a little sensitive upon the subject, feeling evidently that if the matter got abroad, it might injure the sale of the really excellent porgy oil which is the product of their sole manufacturing interest. This reluctance to advertise the skeleton in their closet, superadded to the slowness of these obtuse, fishy, matter-of-fact people to recognize the transcendent importance of the case, must be accepted as explanation of the fact that John Newbegin's spirit has been on earth between three and four months, and yet the singular circumstance is not known to the whole country.

But the Pocockians have at last come to see that a spirit is not necessarily a malevolent spirit, and accepting his presence as a fact in their stolid, unreasoning way, they are quite neighborly and sociable with Mr. Newbegin.

I know that your first question will be: "Is there sufficient proof of his ever having been dead?" To this I answer unhesitatingly, "Yes." He was too well-known a character and too many people saw the corpse to admit of any mistake on this point. I may add here that it was at one time proposed to disinter the original remains, but that project was abandoned in deference to the wishes of Mr. Newbegin, who feels a natural delicacy about having his first set of bones disturbed from motives of mere curiosity.

YOU will readily believe that I took occasion to see and converse with John Newbegin. I found him affable and even communicative. He is perfectly aware of his doubtful status as a being, but is in hopes that at some future time there may be legislation that shall correctly define his position and the position of any spirit who may follow him into the material world. The only point upon which he is reticent is his experience during the four years that elapsed between his death and his reappearance at Pocock. It is to be presumed that the memory is not a pleasant one: at least he never speaks of this period. He candidly admits, however, that he is glad to get back to earth and that he embraced the very first opportunity to be materialized.

Mr. Newbegin says that he is consumed with remorse for the wasted years of his previous existence. Indeed, his conduct during the past three months would show that this regret is genuine. He has discarded his eccentric costume, and dresses like a reasonable spirit. He has not touched liquor since his reappearance. He has embarked in the porgy oil business, and his operations already rival that of Hodgeson, his old partner in the Mary Emmeline and the Prettyboat. By the way, Newbegin threatens to sue Hodgeson for his undivided quarter in each of these vessels, and this interesting case therefore bids fair to be thoroughly investigated in the courts.

As a business man, he is generally esteemed on the Island, although there is a noticeable reluctance to discount his paper at long dates. In short, Mr. John Newbegin is a most respectable citizen (if a dead man can be a citizen) and has announced his intention of running for the next Legislature!

AND now, my dear ———, I have told you the substance of all I know respecting this strange, strange case. Yet, after all, why so strange? We accepted materialization at Chittenden. Is this any more than the logical issue of that admission? If the spirit may return to earth, clothed in flesh and blood and all the physical attributes of humanity, why may it not remain on earth as long as it sees fit?

Thinking of it from whatever standpoint, I cannot but regard John Newbegin as the pioneer of a possibly large immigration from the spirit world. The bars once down, a whole flock will come trooping back to earth. Death will lose its significance altogether. And when I think of the disturbance which will result in our social relations, of the overthrow of all accepted institutions, and of the nullification of all principles of political economy, law, and religion, I am lost in perplexity and apprehension.

"SHE formerly showed the name Flying Sprite on her starn moldin'," said Captain Trumbull Cram, "but I had thet gouged out and planed off, and Judas Iscariot in gilt sot thar instid."

"That was an extraordinary name," said I.

"'Strornary craft," replied the captain, as he absorbed another inch and a half of niggerhead. "I'm neither a profane man or an irreverend; but sink my jig if I don't believe the sperrit of Judas possessed thet schooner. Hey, Ammi?"

The young man addressed as Ammi was seated upon a mackerel barrel. He deliberately removed from his lips a black brierwood and shook his head with great gravity.

"The cap'n," said Ammi, "is neither a profane or an irreverend. What he says he mostly knows; but when he sinks his jig he's allers to be depended on."

Fortified with this neighborly estimate of character, Captain Cram proceeded. "You larf at the idea of a schooner's soul? Perhaps you hey sailed 'em forty-odd year up and down this here coast, an' 'quainted yourself with their dispositions an' habits of mind. Hey, Ammi?"

"The cap'n," explained the gentleman on the mackerel keg, "hez coasted an' hez fished for forty-six year. He's lumbered and he's iced. When the cap'n sees fit for to talk about schooners he understands the subjeck."

"My friend," said the captain, "a schooner has a soul like a human being, but considerably broader of beam, whether for good or for evil. I ain't a goin' to deny thet I prayed for the Judas in Tuesday 'n' Thursday evenin' meetin', week arter week an' month arter month. I ain't a goin' to deny thet I interested Deacon Plympton in the 'rastle for her redemption. It was no use, my friend; even the deacon's powerful p'titions were clear waste."