RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

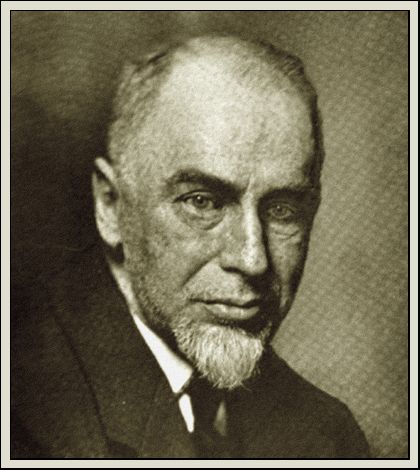

Edward Page Mitchell.

EDWARD PAGE MITCHELL (1852–1927), who worked as an editor and story writer for the New York daily The Sun, is recognized as a major figure in the early development of the science fiction genre.

His works include stories about a time machine ("The Clock that Went Backward," 1881) and an invisible man ("The Crystal Man," 1881), both of which pre-date H.G. Wells' novels on these subjects (1895 and 1897).

Other works include stories about faster-than-light travel ("The Tachypomp," 1874), a cyborg ("The Ablest Man in the World," 1879), teleportation ("The Man without a Body", 1877), and mind-transfer ("Exchanging Their Souls," 1877).

Besides works of science fiction, Mitchell wrote stories in the fantasy and horror genres. RGL offers special compilations of tales in all three categories.

—Roy Glashan, 22 January 2023

Scribner's Monthly with "The Tachypomp"

THERE was nothing mysterious about Professor Surd's dislike for me. I was the only poor mathematician in an exceptionally mathematical class. The old gentleman sought the lecture-room every morning with eagerness, and left it reluctantly. For was it not a thing of joy to find seventy young men who, individually and collectively, preferred x to XX; who had rather differentiate than dissipate; and for whom the limbs of the heavenly bodies had more attractions than those of earthly stars upon the spectacular stage?

So affairs went on swimmingly between the Professor of Mathematics and the junior Class at Polyp University. In every man of the seventy, the sage saw the logarithm of a possible La Place, of a Sturm, or of a Newton. It was a delightful task for him to lead them through the pleasant valleys of conic sections, and beside the still waters of the integral calculus. Figuratively speaking, his problem was not a hard one. He had only to manipulate, and eliminate, and to raise to a higher power, and the triumphant result of examination day was assured.

But I was a disturbing element, a perplexing unknown quantity, which had somehow crept into the work, and which seriously threatened to impair the accuracy of his calculations. It was a touching sight to behold the venerable mathematician as he pleaded with me not so utterly to disregard precedent in the use of cotangents; or as he urged, with eyes almost tearful, that ordinates were dangerous things to trifle with. All in vain. More theorems went on to my cuff than into my head. Never did chalk do so much work to so little purpose. And, therefore, it came that Furnace Second was reduced to zero in Professor Surd's estimation. He looked upon me with all the horror which an unalgebraic nature could inspire. I have seen the professor walk around an entire square rather than meet the man who had no mathematics in his soul.

For Furnace Second there were no invitations to Professor Surd's house. Seventy of the class supped in delegations around the periphery of the professor's tea-table. The seventy-first knew nothing of the charms of that perfect ellipse, with its twin bunches of fuchsias and geraniums in gorgeous precision at the two foci.

This, unfortunately enough, was no trifling deprivation. Not that I longed especially for segments of Mrs. Surd's justly celebrated lemon pies; not that the spheroidal damsons of her excellent preserving had any marked allurements; not even that I yearned to hear the professor's jocose table talk about binomials, and chatty illustrations of abstruse paradoxes. The explanation is far different. Professor Surd had a daughter. Twenty years before, he made a proposition of marriage to the present Mrs. S. He added a little corollary to his proposition not long after. The corollary was a girl.

Abscissa Surd was as perfectly symmetrical as Giotto's circle, and as pure, withal, as the mathematics her father taught. It was just when spring was coming to extract the roots of frozen-up vegetation that I fell in love with the corollary. That she herself was not indifferent I soon had reason to regard as a self-evident truth.

The sagacious reader will already recognize nearly all the elements necessary to a well-ordered plot. We have introduced a heroine, inferred a hero, and constructed a hostile parent after the most approved model. A movement for the story, a Deus ex machina, is alone lacking. With considerable satisfaction I can promise a perfect novelty in this line, a Deus ex machina never before offered to the public.

It would be discounting ordinary intelligence to say that I sought with unwearying assiduity to figure my way into the stern father's good-will; that never did dullard apply himself to mathematics more patiently than I; that never did faithfulness achieve such meager reward. Then I engaged a private tutor. His instructions met with no better success.

My tutor's name was Jean Marie Rivarol. He was a unique Alsatian—though Gallic in name, thoroughly Teuton in nature; by birth a Frenchman, by education a German. His age was thirty; his profession, omniscience; the wolf at his door, poverty; the skeleton in his closet, a consuming but unrequited passion. The most recondite principles of practical science were his toys; the deepest intricacies of abstract science his diversions. Problems which were foreordained mysteries to me were to him as clear as Tahoe water. Perhaps this very fact will explain our lack of success in the relation of tutor and pupil; perhaps the failure is alone due to my own unmitigated stupidity. Rivarol had hung about the skirts of the University for several years; supplying his few wants by writing for scientific journals, or by giving assistance to students who, like myself, were characterized by a plethora of purse and a paucity of ideas; cooking, studying and sleeping in his attic lodgings; and prosecuting queer experiments all by himself.

We were not long discovering that even this eccentric genius could not transplant brains into my deficient skull. I gave over the struggle in despair. An unhappy year dragged its slow length around. A gloomy year it was, brightened only by occasional interviews with Abscissa, the Abbie of my thoughts and dreams.

Commencement day was coming on apace. I was soon to go forth, with the rest of my class, to astonish and delight a waiting world. The professor seemed to avoid me more than ever. Nothing but the conventionalities, I think kept him from shaping his treatment of me on the basis of unconcealed disgust.

At last, in the very recklessness of despair, I resolved to see him, plead with him, threaten him if need be, and risk all my fortunes on one desperate chance. I wrote him a somewhat defiant letter, stating my aspirations, and, as I flattered myself, shrewdly giving him a week to get over the first shock of horrified surprise. Then I was to call and learn my fate.

During the week of suspense I nearly worried myself into a fever. It was first crazy hope, and then saner despair. On Friday evening, when I presented myself at the professor's door, I was such a haggard, sleepy, dragged-out spectre, that even Miss Jocasta, the harsh-favored maiden sister of the Surd's, admitted me with commiserate regard, and suggested pennyroyal tea.

Professor Surd was at a faculty meeting. Would I wait?

Yes, till all was blue, if need be. Miss Abbie?

Abscissa had gone to Wheelborough to visit a school friend. The aged maiden hoped I would make myself comfortable, and departed to the unknown haunts which knew Jocasta's daily walk.

Comfortable! But I settled myself in a great uneasy chair and waited, with the contradictory spirit common to such junctures, dreading every step lest it should herald the man whom, of all men, I wished to see.

I had been there at least an hour, and was growing right drowsy.

At length Professor Surd came in. He sat down in the dusk opposite me, and I thought his eyes glinted with malignant pleasure as he said, abruptly:

"So, young man, you think you are a fit husband for my girl?"

I stammered some inanity about making up in affection what I lacked in merit; about my expectations, family and the like. He quickly interrupted me.

"You misapprehend me, sir. Your nature is destitute of those mathematical perceptions and acquirements which are the only sure foundations of character. You have no mathematics in you.

"You are fit for treason, stratagems, and spoils.—Shakespeare. Your narrow intellect cannot understand and appreciate a generous mind. There is all the difference between you and a Surd, if I may say it, which intervenes between an infinitesimal and an infinite. Why, I will even venture to say that you do not comprehend the Problem of the Couriers!"

I admitted that the Problem of the Couriers should be classed rather without my list of accomplishments than within it. I regretted this fault very deeply, and suggested amendment. I faintly hoped that my fortune would be such—

"Money!" he impatiently exclaimed. "Do you seek to bribe a Roman senator with a penny whistle? Why, boy, do you parade your paltry wealth, which, expressed in mills, will not cover ten decimal places, before the eyes of a man who measures the planets in their orbits, and close crowds infinity itself?"

I hastily disclaimed any intention of obtruding my foolish dollars, and he went on:

"Your letter surprised me not a little. I thought you would be the last person in the world to presume to an alliance here. But having a regard for you personally"—and again I saw malice twinkle in his small eyes—"an still more regard for Abscissa's happiness, I have decided that you shall have her—upon conditions. Upon conditions," he repeated, with a half-smothered sneer.

"What are they?" cried I, eagerly enough. "Only name them."

"Well, sir," he continued, and the deliberation of his speech seemed the very refinement of cruelty, "you have only to prove yourself worthy an alliance with a mathematical family. You have only to accomplish a task which I shall presently give you. Your eyes ask me what it is. I will tell you. Distinguish yourself in that noble branch of abstract science in which, you cannot but acknowledge, you are at present sadly deficient. I will place Abscissa's hand in yours whenever you shall come before me and square the circle to my satisfaction. No! That is too easy a condition. I should cheat myself. Say perpetual motion. How do you like that? Do you think it lies within the range of your mental capabilities? You don't smile. Perhaps your talents don't run in the way of perpetual motion. Several people have found that theirs didn't. I'll give you another chance. We were speaking of the Problem of the Couriers, and I think you expressed a desire to know more of that ingenious question. You shall have the opportunity. Sit down someday, when you have nothing else to do, and discover the principle of infinite speed. I mean the law of motion which shall accomplish an infinitely great distance in an infinitely short time. You may mix in a little practical mechanics, if you choose. Invent some method of taking the tardy Courier over his road at the rate of sixty miles a minute. Demonstrate me this discovery (when you have made it!) mathematically, and approximate it practically, and Abscissa is yours. Until you can, I will thank you to trouble neither myself nor her."

I could stand his mocking no longer. I stumbled mechanically out of the room, and out of the house. I even forgot my hat and gloves. For an hour I walked in the moonlight. Gradually I succeeded to a more hopeful frame of mind. This was due to my ignorance of mathematics. Had I understood the real meaning of what he asked, I should have been utterly despondent.

Perhaps this problem of sixty miles a minute was not so impossible after all. At any rate I could attempt, though I might not succeed. And Rivarol came to my mind. I would ask him. I would enlist his knowledge to accompany my own devoted perseverance. I sought his lodgings at once.

The man of science lived in the fourth story, back. I had never been in his room before. When I entered, he was in the act of filling a beer mug from a carboy labeled aqua fortis.

"Seat you," he said. "No, not in that chair. That is my Petty Cash Adjuster." But he was a second too late. I had carelessly thrown myself into a chair of seductive appearance. To my utter amazement it reached out two skeleton arms and clutched me with a grasp against which I struggled in vain. Then a skull stretched itself over my shoulder and grinned with ghastly familiarity close to my face.

Rivarol came to my aid with many apologies. He touched a spring somewhere and the Petty Cash Adjuster relaxed its horrid hold. I placed myself gingerly in a plain cane-bottomed rocking-chair, which Rivarol assured me was a safe location.

"That seat," he said, "is an arrangement upon which I much felicitate myself. I made it at Heidelberg. It has saved me a vast deal of small annoyance. I consign to its embraces the friends who bore, and the visitors who exasperate, me. But it is never so useful as when terrifying some tradesman with an insignificant account. Hence the pet name which I have facetiously given it. They are invariably too glad to purchase release at the price of a bill receipted. Do you well apprehend the idea?"

While the Alsation diluted his glass of aqua fortis, shook into it an infusion of bitters, and tossed off the bumper with apparent relish, I had time to look around the strange apartment.

The four corners of the room were occupied respectively by a turning lathe, a Rhumkorff Coil, a small steam engine and an orrery in stately motion. Tables, shelves, chairs and floor supported an odd aggregation of tools, retorts, chemicals, gas receivers, philosophical instruments, boots, flasks, paper-collar boxes, books diminutive and books of preposterous size. There were plaster busts of Aristotle, Archimedes, and Comte, while a great drowsy owl was blinking away, perched on the benign brow of Martin Farquhar Tupper. "He always roosts there when he proposes to slumber," explained my tutor. "You are a bird of no ordinary mind. Schlafen Sie wohl."

Through a closet door, half open, I could see a human-like form covered with a sheet. Rivarol caught my glance.

"That," said he, "will be my masterpiece. It is a Microcosm, an Android, as yet only partially complete. And why not? Albertus Magnus constructed an image perfect to talk metaphysics and confute the schools. So did Sylvester II; so did Robertus Greathead. Roger Bacon made a brazen head that held discourses. But the first named of these came to destruction. Thomas Aquinas got wrathful at some of its syllogisms and smashed its head. The idea is reasonable enough. Mental action will yet be reduced to laws as definite as those which govern the physical. Why should not I accomplish a manikin which shall preach as original discourses as the Reverend Dr. Allchin, or talk poetry as mechanically as Paul Anapest? My android can already work problems in vulgar fractions and compose sonnets. I hope to teach it the Positive Philosophy."

Out of the bewildering confusion of his effects Rivarol produced two pipes and filled them. He handed one to me.

"And here," he said, "I live and am tolerably comfortable. When my coat wears out at the elbows I seek the tailor and am measured for another. When I am hungry I promenade myself to the butcher's and bring home a pound or so of steak, which I cook very nicely in three seconds by this oxy-hydrogen flame. Thirsty, perhaps, I send for a carboy of aqua fortis. But I have it charged, all charged. My spirit is above any small pecuniary transaction. I loathe your dirty greenbacks, and never handle what they call scrip."

"But are you never pestered with bills?" I asked. "Don't the creditors worry your life out?"

"Creditors!" gasped Rivarol. "I have learned no such word in your very admirable language. He who will allow his soul to be vexed by creditors is a relic of an imperfect civilization. Of what use is science if it cannot avail a man who has accounts current? Listen. The moment you or anyone else enters the outside door this little electric bell sounds me warning. Every successive step on Mrs. Grimler's staircase is a spy and informer vigilant for my benefit. The first step is trod upon. That trusty first step immediately telegraphs your weight. Nothing could be simpler. It is exactly like any platform scale. The weight is registered up here upon this dial. The second step records the size of my visitor's feet. The third his height, the fourth his complexion, and so on. By the time he reaches the top of the first flight I have a pretty accurate description of him right here at my elbow, and quite a margin of time for deliberation and action. Do you follow me? It is plain enough. Only the ABC of my science."

"I see all that," I said, "but I don't see how it helps you any. The knowledge that a creditor is coming won't pay his bill. You can't escape unless you jump out of the window."

Rivarol laughed softly. "I will tell you. You shall see what becomes of any poor devil who goes to demand money of me—of a man of science. Ha! ha! It pleases me. I was seven weeks perfecting my Dun Suppressor. Did you know"—he whispered exultingly—"did you know that there is a hole through the earth's center? Physicists have long suspected it; I was the first to find it. You have read how Rhuyghens, the Dutch navigator, discovered in Kerguellen's Land an abysmal pit which fourteen hundred fathoms of plumb-line failed to sound. Herr Tom, that hole has no bottom! It runs from one surface of the earth to the antipodal surface. It is diametric. But where is the antipodal spot? You stand upon it. I learned this by the merest chance. I was deep-digging in Mrs. Grimler's cellar, to bury a poor cat I had sacrificed in a galvanic experiment, when the earth under my spade crumbled, caved in, and wonder-stricken I stood upon the brink of a yawning shaft. I dropped a coal-hod in. It went down, down, down, bounding and rebounding. In two hours and a quarter that coal-hod came up again. I caught it and restored it to the angry Grimler. Just think a minute. The coal-hod went down, faster and faster, till it reached the center of the earth. There it would stop, were it not for acquired momentum. Beyond the center its journey was relatively upward, toward the opposite surface of the globe. So, losing velocity, it went slower and slower till it reached that surface. Here it came to rest for a second and then fell back again, eight thousand odd miles, into my hands. Had I not interfered with it, it would have repeated its journey, time after time, each trip of shorter extent, like the diminishing oscillations of a pendulum, till it finally came to eternal rest at the center of the sphere. I am not slow to give a practical application to any such grand discovery. My Dun Suppressor was born of it. A trap, just outside my chamber door: a spring in here: a creditor on the trap: need I say more?"

"But isn't it a trifle inhuman?" I mildly suggested. "Plunging an unhappy being into a perpetual journey to and from Kerguellen's Land, without a moment's warning."

"I give them a chance. When they come up the first time I wait at the mouth of the shaft with a rope in hand. If they are reasonable and will come to terms, I fling them the line. If they perish, 'tis their own fault. Only," he added, with a melancholy smile, "the center is getting so plugged up with creditors that I am afraid there soon will be no choice whatever for 'em."

By this time I had conceived a high opinion of my tutor's ability. If anybody could send me waltzing through space at an infinite speed, Rivarol could do it. I filled my pipe and told him the story. He heard with grave and patient attention. Then, for full half an hour, he whiffed away in silence. Finally he spoke.

"The ancient cipher has overreached himself. He has given you a choice of two problems, both of which he deems insoluble. Neither of them is insoluble. The only gleam of intelligence Old Cotangent showed was when he said that squaring the circle was too easy. He was right. It would have given you your Liebchen in five minutes. I squared the circle before I discarded pantalets. I will show you the work—but it would be a digression, and you are in no mood for digressions. Our first chance, therefore, lies in perpetual motion. Now, my good friend, I will frankly tell you that, although I have compassed this interesting problem, I do not choose to use it in your behalf. I too, Herr Tom, have a heart. The loveliest of her sex frowns upon me. Her somewhat mature charms are not for Jean Marie Rivarol. She has cruelly said that her years demand of me filial rather than connubial regard. Is love a matter of years or of eternity? This question did I put to the cold, yet lovely Jocasta."

"Jocasta Surd!" I remarked in surprise, "Abscissa's aunt!"

"The same," he said, sadly. "I will not attempt to conceal that upon the maiden Jocasta my maiden heart has been bestowed. Give me your hand, my nephew in affliction as in affection!"

Rivarol dashed away a not discreditable tear, and resumed:

"My only hope lies in this discovery of perpetual motion. It will give me the fame, the wealth. Can Jocasta refuse these? If she can, there is only the trapdoor and—Kerguellen's Land!"

I bashfully asked to see the perpetual-motion machine. My uncle in affliction shook his head.

"At another time," he said. "Suffice it at present to say, that it is something upon the principle of a woman's tongue. But you see now why we must turn in your case to the alternative condition—infinite speed. There are several ways in which this may be accomplished, theoretically. By the lever, for instance. Imagine a lever with a very long and a very short arm. Apply power to the shorter arm which will move it with great velocity. The end of the long arm will move much faster. Now keep shortening the short arm and lengthening the long one, and as you approach infinity in their difference of length, you approach infinity in the speed of the long arm. It would be difficult to demonstrate this practically to the professor. We must seek another solution. Jean Marie will meditate. Come to me in a fortnight. Good-night. But stop! Have you the money—das Geld?"

"Much more than I need."

"Good! Let us strike hands. Gold and Knowledge; Science and Love. What may not such a partnership achieve? We go to conquer thee, Abscissa. Vorwärts!"

When, at the end of a fortnight; I sought Rivarol's chamber, I passed with some little trepidation over the terminus of the Air Line to Kerguellen's Land, and evaded the extended arms of the Petty Cash Adjuster. Rivarol drew a mug of ale for me, and filled himself a retort of his own peculiar beverage.

"Come," he said at length. "Let us drink success to the Tachypomp."

"The Tachypomp?"

"Yes. Why not? Tachu, quickly, and pempo, pepompa, to send. May it send you quickly to your wedding-day. Abscissa is yours. It is done. When shall we start for the prairies?"

"Where is it?" I asked, looking in vain around the room for any contrivance which might seem calculated to advance matrimonial prospects.

"It is here," and he gave his forehead a significant tap. Then he held forth didactically.

"There is force enough in existence to yield us a speed of sixty miles a minute, or even more. All we need is the knowledge how to combine and apply it. The wise man will not attempt to make some great force yield some great speed. He will keep adding the little force to the little force, making each little force yield its little speed, until an aggregate of little forces shall be a great force, yielding an aggregate of little speeds, a great speed. The difficulty is not in aggregating the forces; it lies in the corresponding aggregation of the speeds. One musket ball will go, say a mile. It is not hard to increase the force of muskets to a thousand, yet the thousand musket balls will go no farther, and no faster, than the one. You see, then, where our trouble lies. We cannot readily add speed to speed, as we add force to force. My discovery is simply the utilization of a principle which extorts an increment of speed from each increment of power. But this is the metaphysics of physics. Let us be practical or nothing.

"When you have walked forward, on a moving train, from the rear car, toward the engine, did you ever think what you were really doing?"

"Why, yes, I have generally been going to the smoking car to have a cigar."

"Tut, tut—not that! I mean, did it ever occur to you on such an occasion, that absolutely you were moving faster than the train? The train passes the telegraph poles at the rate of thirty miles an hour, say. You walk toward the smoking car at the rate of four miles an hour. Then you pass the telegraph poles at the rate of thirty-four miles. Your absolute speed is the speed of the engine, plus the speed of your own locomotion. Do you follow me?"

I began to get an inkling of his meaning, and told him so.

"Very well. Let us advance a step. Your addition to the speed of the engine is trivial, and the space in which you can exercise it, limited. Now suppose two stations, A and B, two miles distant by the track. Imagine a train of platform cars, the last car resting at station A. The train is a mile long, say. The engine is therefore within a mile of station B. Say the train can move a mile in ten minutes. The last car, having two miles to go, would reach B in twenty minutes, but the engine, a mile ahead, would get there in ten. You jump on the last car, at A, in a prodigious hurry to reach Abscissa, who is at B. If you stay on the last car it will be twenty long minutes before you see her. But the engine reaches B and the fair lady in ten. You will be a stupid reasoner, and an indifferent lover, if you don't put for the engine over those platform cars, as fast as your legs will carry you. You can run a mile, the length of the train, in ten minutes. Therefore, you reach Abscissa when the engine does, or in ten minutes—ten minutes sooner than if you had lazily sat down upon the rear car and talked politics with the brakeman. You have diminished the time by one half. You have added your speed to that of the locomotive to some purpose. Nicht wahr?"

I saw it perfectly; much plainer, perhaps, for his putting in the clause about Abscissa.

He continued, "This illustration, though a slow one, leads up to a principle which may be carried to any extent. Our first anxiety will be to spare your legs and wind. Let us suppose that the two miles of track are perfectly straight, and make our train one platform car, a mile long, with parallel rails laid upon its top. Put a little dummy engine on these rails, and let it run to and fro along the platform car, while the platform car is pulled along the ground track. Catch the idea? The dummy takes your place. But it can run its mile much faster. Fancy that our locomotive is strong enough to pull the platform car over the two miles in two minutes. The dummy can attain the same speed. When the engine reaches B in one minute, the dummy, having gone a mile a-top the platform car, reaches B also. We have so combined the speeds of those two engines as to accomplish two miles in one minute. Is this all we can do? Prepare to exercise your imagination."

I lit my pipe.

"Still two miles of straight track, between A and B. On the track a long platform car, reaching from A to within a quarter of a mile of B. We will now discard ordinary locomotives and adopt as our motive power a series of compact magnetic engines, distributed underneath the platform car, all along its length."

"I don't understand those magnetic engines."

"Well, each of them consists of a great iron horseshoe, rendered alternately a magnet and not a magnet by an intermittent current of electricity from a battery, this current in its turn regulated by clockwork. When the horseshoe is in the circuit, it is a magnet, and it pulls its clapper toward it with enormous power. When it is out of the circuit, the next second, it is not a magnet, and it lets the clapper go. The clapper, oscillating to and fro, imparts a rotatory motion to a fly wheel, which transmits it to the drivers on the rails. Such are our motors. They are no novelty, for trial has proved them practicable.

"With a magnetic engine for every truck of wheels, we can reasonably expect to move our immense car, and to drive it along at a speed, say, of a mile a minute.

"The forward end, having but a quarter of a mile to go, will reach B in fifteen seconds. We will call this platform car number 1. On top of number 1 are laid rails on which another platform car, number 2, a quarter of a mile shorter than number 1, is moved in precisely the same way. Number 2, in its turn, is surmounted by number 3, moving independently of the tiers beneath, and a quarter of a mile shorter than number 2. Number 2 is a mile and a half long; number 3 a mile and a quarter. Above, on successive levels, are number 4, a mile long; number 5, three quarters of a mile; number 6, half a mile; number 7, a quarter of a mile, and number 8, a short passenger car, on top of all.

"Each car moves upon the car beneath it, independently of all the others, at the rate of a mile a minute. Each car has its own magnetic engines. Well, the train being drawn up with the latter end of each car resting against a lofty bumping-post at A, Tom Furnace, the gentlemanly conductor, and Jean Marie Rivarol, engineer, mount by a long ladder to the exalted number 8. The complicated mechanism is set in motion. What happens?

"Number 8 runs a quarter of a mile in fifteen seconds and reaches the end of number 7. Meanwhile number 7 has run a quarter of a mile in the same time and reached the end of number 6; number 6, a quarter of a mile in fifteen seconds, and reached the end of number 5; number 5, the end of number 4; number 4, of number 3; number 3, of number 2; number 2, of number 1. And number 1, in fifteen seconds, has gone its quarter of a mile along the ground track, and has reached station B. All this has been done in fifteen seconds. Wherefore, numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 come to rest against the bumping-post at B, at precisely the same second. We, in number 8, reach B just when number 1 reaches it. In other words, we accomplish two miles in fifteen seconds. Each of the eight cars, moving at the rate of a mile a minute, has contributed a quarter of a mile to our journey, and has done its work in fifteen seconds. All the eight did their work at once, during the same fifteen seconds. Consequently we have been whizzed through the air at the somewhat startling speed of seven and a half seconds to the mile. This is the Tachypomp. Does it justify the name?"

Although a little bewildered by the complexity of cars, I apprehended the general principle of the machine. I made a diagram, and understood it much better. "You have merely improved on the idea of my moving faster than the train when I was going to the smoking car?"

"Precisely. So far we have kept within the bounds of the practicable. To satisfy the professor, you can theorize in something after this fashion: If we double the number of cars, thus decreasing by one half the distance which each has to go, we shall attain twice the speed. Each of the sixteen cars will have but one eighth of a mile to go. At the uniform rate we have adopted, the two miles can be done in seven and a half instead of fifteen seconds. With thirty-two cars, and a sixteenth of a mile, or twenty rods difference in their length, we arrive at the speed of a mile in less than two seconds; with sixty-four cars, each traveling but ten rods, a mile under the second. More than sixty miles a minute! If this isn't rapid enough for the professor, tell him to go on, increasing the number of his cars and diminishing the distance each one has to run. If sixty-four cars yield a speed of a mile inside the second, let him fancy a Tachypomp of six hundred and forty cars, and amuse himself calculating the rate of car number 640. Just whisper to him that when he has an infinite number of cars with an infinitesimal difference in their lengths, he will have obtained that infinite speed for which he seems to yearn. Then demand Abscissa."

I wrung my friend's hand in silent and grateful admiration. I could say nothing.

"You have listened to the man of theory," he said proudly. "You shall now behold the practical engineer. We will go to the west of the Mississippi and find some suitably level locality. We will erect thereon a model Tachypomp. We will summon thereunto the professor, his daughter, and why not his fair sister Jocasta, as well? We will take them a journey which shall much astonish the venerable Surd. He shall place Abscissa's digits in yours and bless you both with an algebraic formula. Jocasta shall contemplate with wonder the genius of Rivarol. But we have much to do. We must ship to St. Joseph the vast amount of material to be employed in the construction of the Tachypomp. We must engage a small army of workmen to effect that construction, for we are to annihilate time and space. Perhaps you had better see your bankers."

I rushed impetuously to the door. There should be no delay.

"Stop! stop! Um Gottes Willen, stop!" shrieked Rivarol. "I launched my butcher this morning and I haven't bolted the—"

But it was too late. I was upon the trap. It swung open with a crash, and I was plunged down, down, down! I felt as if I were falling through illimitable space. I remember wondering, as I rushed through the darkness, whether I should reach Kerguellen's Land or stop at the center. It seemed an eternity. Then my course was suddenly and painfully arrested.

I opened my eyes. Around me were the walls of Professor Surd's study. Under me was a hard, unyielding plane which I knew too well was Professor Surd's study floor. Behind me was the black, slippery, haircloth chair which had belched me forth, much as the whale served Jonah. In front of me stood Professor Surd himself, looking down with a not unpleasant smile.

"Good evening, Mr. Furnace. Let me help you up. You look tired, sir. No wonder you fell asleep when I kept you so long waiting. Shall I get you a glass of wine? No? By the way, since receiving your letter I find that you are a son of my old friend, Judge Furnace. I have made inquiries, and see no reason why you should not make Abscissa a good husband."

Still, I can see no reason why the Tachypomp should not have succeeded. Can you?

BOSTON, December 13— Professor Dummkopf, a German gentleman of education and ingenuity, at present residing in this city, is engaged on experiments which, if successful, will work a great change both in metaphysical science and in the practical relationships of life.

The professor is firm in the conviction that modern science has narrowed down to almost nothing the border territory between the material and the immaterial. It may be some time, he admits, before any man shall be able to point his finger and say with authority, "Here mind begins; here matter ends." It may be found that the boundary line between mind and matter is as purely imaginary as the equator that divides the northern from the southern hemisphere. It may be found that mind is essentially objective as is matter, or that matter is as entirely Subjective as is mind. It may be that there is no matter except as conditioned in mind. It may be that there is no mind except as conditioned in matter. Professor Dummkopf's views upon this broad topic are interesting, although somewhat bewildering. I can cordially recommend the great work in nine volumes, Körperliche Geisteswissenschaft, to any reader who may be inclined to follow up the subject. The work can undoubtedly be obtained in the original Leipzig edition through any responsible importer of foreign books.

Great as is the problem suggested above, Professor Dummkopf has no doubt whatever that it will be solved, and at no distant day. He himself has taken a masterly stride toward a solution by the brilliant series of experiments I am about to describe. He not only believes with Tyndall that matter contains the promise and potency of all life, but he believes that every force, physical, intellectual, and moral, may be resolved into matter, formulated in terms of matter, and analyzed into its constituent forms of matter; that motion is matter, mind is matter, law is matter, and even that abstract relations of mathematical abstractions are purely material.

IN accordance with an invitation extended to me at the last meeting of the Radical Club—an organization, by the way, which is doing a noble work in extending our knowledge of the Unknowable—I dallied yesterday at Professor Dummkopf's rooms in Joy Street, at the West End. I found the professor in his apartment on the upper floor, busily engaged in an attempt to photograph smell.

"You see," he said, as he stirred up a beaker from which strongly marked fumes of sulphureted hydrogen were arising and filling the room, "you see that, having demonstrated the objectiveness of sensation, it has now become my privilege and easy task to show that the phenomena of sensation are equally material. Hence I am attempting to photograph smell."

The professor then darted behind a camera which was leveled upon the vessel in which the suffocating fumes were generated and busied himself awhile with the plate.

A disappointed look stole over his face as he brought the negative to the light and examined it anxiously. "Not yet, not yet!" he said sadly, "but patience and improved appliances will finally bring it. The trouble is in my tools, you see, and not in my theory. I did fancy the other day that I obtained a distinctly marked negative from the odor of a hot onion stew, and the thought has cheered me ever since. But it's bound to come. I tell you, my worthy friend, the actinic ray wasn't made for nothing. Could you accommodate me with a dollar and a quarter to buy some more collodion?"

I EXPRESSED my cheerful readiness to be banker to genius.

"Thanks," said the professor, pocketing the scrip and resuming his position at the camera. "When I have pictorially captured smell, the most palpable of the senses, the next thing will be to imprison sound—vulgarly speaking, to bottle it. Just think a moment. Force is as imperishable as matter; indeed, as I have been somewhat successful in showing, it is matter. Now, when a sound wave is once started, it is only lost through an indefinite extension of its circumference. Catch that sound wave, sir! Catch it in a bottle, then its circumference cannot extend. You may keep the sound wave forever if you will only keep it corked up tight. The only difficulty is in bottling it in the first place. I shall attend to the details of that operation just as soon as I have managed to photograph the confounded rotten-egg smell of sulphydric acid."

The professor stirred up the offensive mixture with a glass rod, and continued:

"While my object in bottling sound is mainly scientific, I must confess that I see in success in that direction a prospect of considerable pecuniary profit. I shall be prepared at no distant day to put operas in quart bottles, labeled and assorted, and contemplate a series of light and popular airs in ounce vials at prices to suit the times. You know very well that it costs a ten-dollar bill now to take a lady to hear Martha or Mignon, rendered in first-class style. By the bottle system, the same notes may be heard in one's own parlor at a comparatively trifling expense. I could put the operas into the market at from eighty cents to a dollar a bottle. For oratorios and symphonies I should use demijohns, and the cost would of course be greater. I don't think that ordinary bottles would hold Wagner's music. It might be necessary to employ carboys. Sir, if I were of the sanguine habit of you Americans, I should say that there were millions in it. Being a phlegmatic Teuton, accustomed to the precision and moderation of scientific language, I will merely say that in the success of my experiments with sound I see a comfortable income, as well as great renown."

BY this time the professor had another negative, but an eager examination of it yielded nothing more satisfactory than before. He sighed and continued:

"Having photographed smell and bottled sound, I shall proceed to a project as much higher than this as the reflective faculties are higher than the perceptive, as the brain is more exalted than the ear or nose.

"I am perfectly satisfied that elements of mind are just as susceptible of detection and analysis as elements of matter. Why, mind is matter.

"The soul spectroscope, or, as it will better be known, Dummkopf's duplex self-registering soul spectroscope, is based on the broad fact that whatever is material may be analyzed and determined by the position of the Frauenhofer lines upon the spectrum. If soul is matter, soul may thus be analyzed and determined. Place a subject under the light, and the minute exhalations or emanations proceeding from his soul—and these exhalations or emanations are, of course, matter— will be represented by their appropriate symbols upon the face of a properly arranged spectroscope.

"This, in short, is my discovery. How I shall arrange the spectroscope, and how I shall locate the subject with reference to the light is of course my secret. I have applied for a patent. I shall exploit the instrument and its practical workings at the Centennial. Till then I must decline to enter into any more explicit description of the invention."

"WHAT will be the bearing of your great discovery in its practical workings?"

"I can go so far as to give you some idea of what those practical workings are. The effect of the soul spectroscope upon everyday affairs will be prodigious, simply prodigious. All lying, deceit, double dealing, hypocrisy, will be abrogated under its operation. It will bring about a millennium of truth and sincerity.

"A few practical illustrations. No more bell punches on the horse railroad. The superintendent, with a smattering of scientific knowledge and one of my soul spectroscopes in his office, will examine with the eye of infallible science every applicant for the position of conductor and will determine by the markings on his spectrum whether there is dishonesty in his soul, and this as readily as the chemist decides whether there is iron in a meteorolite or hydrogen in Saturn's ring.

"No more courts, judges, or juries. Hereafter justice will be represented with both eyes wide open and with one of my duplex self-registering soul spectroscopes in her right hand. The inmost nature of the accused will be read at a glance and he will be acquitted, imprisoned for thirty days, or hung, just as the Frauenhofer lines which lay bare his soul may determine.

"No more official corruption or politicians' lies. The important element in every campaign will be one of my soul spectroscopes, and it will effect the most radical, and, at the same time, the most practicable of civil service reforms.

"No more young stool pigeons in tall towers. No man will subscribe for a daily newspaper until a personal inspection of its editor's soul by means of one of my spectroscopes has convinced him that he is paying for truth, honest conviction, and uncompromising independence, rather than for the false utterances of a hired conscience and a bought judgment.

"No more unhappy marriages. The maiden will bring her glibly promising lover to me before she accepts or rejects his proposal, and I shall tell her whether his spectrum exhibits the markings of pure love, constancy, and tenderness, or of sordid avarice, vacillating affections, and post-nuptial cruelty. I shall be the angel with shining sword (or rather spectroscope) who shall attend Hymen and guard the entrance to his paradise.

"No more shame. If anything be wanting in the character of a mean, no amount of brazen pretension on his part can place the missing line in his spectrum. If anything is lacking in him, it will be lacking there. I found by a long series of experiments upon the imperfectly constituted minds of the patients in the lunatic asylum at Taunton—"

"Then you have been at Taunton?"

"Yes. For two years I pursued my studies among the unfortunate inmates of that institution. Not exactly as a patient myself, you understand, but as a student of the phenomena of morbid intellectual developments. But I see I am wearying you, and I must resume my photography before this stuff stops smelling. Come again."

Having bid the professor farewell and wished him abundant success in his very interesting experiments, I went home and read again for the thirty-ninth time Professor Tyndall's address at Belfast.

ON a shelf in the old Arsenal Museum, in the Central Park, in the midst of stuffed hummingbirds, ermines, silver foxes, and bright-colored parakeets, there is a ghastly row of human heads. I pass by the mummified Peruvian, the Maori chief, and the Flathead Indian to speak of a Caucasian head which has had a fascinating interest to me ever since it was added to the grim collection a little more than a year ago.

I was struck with the Head when I first saw it. The pensive intelligence of the features won me. The face is remarkable, although the nose is gone, and the nasal fossae are somewhat the worse for wear. The eyes are likewise wanting, but the empty orbs have an expression of their own. The parchmenty skin is so shriveled that the teeth show to their roots in the jaws. The mouth has been much affected by the ravages of decay, but what mouth there is displays character. It seems to say: "Barring certain deficiencies in my anatomy, you behold a man of parts!" The features of the Head are of the Teutonic cast, and the skull is the skull of a philosopher. What particularly attracted my attention, however, was the vague resemblance which this dilapidated countenance bore to some face which had at some time been familiar to me—some face which lingered in my memory, but which I could not place.

After all, I was not greatly surprised, when I had known the Head for nearly a year, to see it acknowledge our acquaintance and express its appreciation of friendly interest on my part by deliberately winking at me as I stood before its glass case.

This was on a Trustees' Day, and I was the only visitor in the hall. The faithful attendant had gone to enjoy a can of beer with his friend, the superintendent of the monkeys.

The Head winked a second time, and even more cordially than before. I gazed upon its efforts with the critical delight of an anatomist. I saw the masseter muscle flex beneath the leathery skin. I saw the play of the glutinators, and the beautiful lateral movement of the internal platsyma. I knew the Head was trying to speak to me. I noted the convulsive twitchings of the risorius and the zygomaticus major, and knew that it was endeavoring to smile.

"Here," I thought, "is either a case of vitality long after decapitation, or, an instance of reflex action where there is no diastaltic or excitor-motory system. In either case the phenomenon is unprecedented, and should be carefully observed. Besides, the Head is evidently well disposed toward me." I found a key on my bunch which opened the glass door.

"Thanks," said the Head. "A breath of fresh air is quite a treat."

"How do you feel?" I asked politely. "How does it seem without a body?"

The Head shook itself sadly and sighed. "I would give," it said, speaking through its ruined nose, and for obvious reasons using chest tones sparingly, "I would give both ears for a single leg. My ambition is principally ambulatory, and yet I cannot walk. I cannot even hop or waddle. I would fain travel, roam, promenade, circulate in the busy paths of men, but I am chained to this accursed shelf. I am no better off than these barbarian heads—I, a man of science! I am compelled to sit here on my neck and see sandpipers and storks all around me, with legs and to spare. Look at that infernal little Oedieneninus longpipes over there. Look at that miserable gray-headed porphyric. They have no brains, no ambition, no yearnings. Yet they have legs, legs, legs, in profusion." He cast an envious glance across the alcove at the tantalizing limbs of the birds in question and added gloomily, "There isn't even enough of me to make a hero for one of Wilkie Collins's novels."

I did not exactly know how to console him in so delicate a manner, but ventured to hint that perhaps his condition had its compensations in immunity from corns and the gout.

"And as to arms," he went on, "there's another misfortune for you! I am unable to brush away the flies that get in here— Lord knows how—in the summertime. I cannot reach over and cuff that confounded Chinook mummy that sits there grinning at me like a jack-in-the-box. I cannot scratch my head or even blow my nose (his nose!) decently when I get cold in this thundering draft. As to eating and drinking, I don't care. My soul is wrapped up in science. Science is my bride, my divinity. I worship her footsteps in the past and hail the prophecy of her future progress. I—"

I had heard these sentiments before. In a flash I had accounted for the familiar look which had haunted me ever since I first saw the Head. "Pardon me," I said, "you are the celebrated Professor Dummkopf?"

"That is, or was, my name," he replied, with dignity.

"And you formerly lived in Boston, where you carried on scientific experiments of startling originality. It was you who first discovered how to photograph smell, how to bottle music, how to freeze the Aurora Borealis. It was you who first applied spectral analysis to mind."

"Those were some of my minor achievements," said the Head, sadly nodding itself—"small when compared with my final invention, the grand discovery which was at the same time my greatest triumph and my ruin. I lost my Body in an experiment."

"How was that?" I asked. "I had not heard."

"No," said the Head. "I being alone and friendless, my disappearance was hardly noticed. I will tell you."

There was a sound upon the stairway. "Hush!" cried the Head. "Here comes somebody. We must not be discovered. You must dissemble."

I hastily closed the door of the glass case, locking it just in time to evade the vigilance of the returning keeper, and dissembled by pretending to examine, with great interest, a nearby exhibit.

On the next Trustees' Day I revisited the museum and gave the keeper of the Head a dollar on the pretense of purchasing information in regard to the curiosities in his charge. He made the circuit of the hall with me, talking volubly all the while.

"That there," he said, as we stood before the Head, "is a relic of morality presented to the museum fifteen months ago. The head of a notorious murderer guillotined at Paris in the last century, sir."

I fancied that I saw a slight twitching about the corners of Professor Dummkopf's mouth and an almost imperceptible depression of what was once his left eyelid, but he kept his face remarkably well under the circumstances. I dismissed my guide with many thanks for his intelligent services, and, as I had anticipated, he departed forthwith to invest his easily earned dollar in beer, leaving me to pursue my conversation with the Head.

"Think of putting a wooden-headed idiot like that," said the professor, after I had opened his glass prison, "in charge of a portion, however small, of a man of science—of the inventor of the Telepomp! Paris! Murderer! Last century, indeed!" and the Head shook with laughter until I feared that it would tumble off the shelf.

"You spoke of your invention, the Telepomp," I suggested.

"Ah, yes," said the Head, simultaneously recovering its gravity and its center of gravity; "I promised to tell you how I happen to be a Man without a Body. You see that some three or four years ago I discovered the principle of the transmission of sound by electricity. My telephone, as I called it, would have been an invention of great practical utility if I had been spared to introduce it to the public. But, alas—"

"Excuse the interruption," I said, "but I must inform you that somebody else has recently accomplished the same thing. The telephone is a realized fact."

"Have they gone any further?" he eagerly asked. "Have they discovered the great secret of the transmission of atoms? In other words, have they accomplished the Telepomp?"

"I have heard nothing of the kind," I hastened to assure him, "but what do you mean?"

"Listen," he said. "In the course of my experiments with the telephone I became convinced that the same principle was capable of indefinite expansion. Matter is made up of molecules, and molecules, in their turn, are made up of atoms. The atom, you know, is the unit of being. The molecules differ according to the number and the arrangement of their constituent atoms. Chemical changes are effected by the dissolution of the atoms in the molecules and their rearrangements into molecules of another kind. This dissolution may be accomplished by chemical affinity or by a sufficiently strong electric current. Do you follow me?"

"Perfectly."

"Well, then, following out this line of thought, I conceived a great idea. There was no reason why matter could not be telegraphed, or, to be etymologically accurate, 'telepomped.' It was only necessary to effect at one end of the line the disintegration of the molecules into atoms and to convey the vibrations of the chemical dissolution by electricity to the other pole, where a corresponding reconstruction could be effected from other atoms. As all atoms are alike, their arrangement into molecules of the same order, and the arrangement of those molecules into an organization similar to the original organization, would be practically a reproduction of the original. It would be a materialization—not in the sense of the spiritualists' cant, but in all the truth and logic of stern science. Do you still follow me?"

"It is a little misty," I said, "but I think I get the point. You would telegraph the Idea of the matter, to use the word Idea in Plato's sense."

"Precisely. A candle flame is the same candle flame although the burning gas is continually changing. A wave on the surface of water is the same wave, although the water composing it is shifting as it moves. A man is the same man although there is not an atom in his body which was there five years before. It is the form, the shape, the Idea, that is essential. The vibrations that give individuality to matter may be transmitted to a distance by wire just as readily as the vibrations that give individuality to sound. So I constructed an instrument by which I could pull down matter, so to speak, at the anode and build it up again on the same plan at the cathode. This was my Telepomp."

"But in practice—how did the Telepomp work?"

"To perfection! In my rooms on joy Street, in Boston, I had about five miles of wire. I had no difficulty in sending simple compounds, such as quartz, starch, and water, from one room to another over this five-mile coil. I shall never forget the joy with which I disintegrated a three-cent postage stamp in one room and found it immediately reproduced at the receiving instrument in another. This success with inorganic matter emboldened me to attempt the same thing with a living organism. I caught a cat—a black and yellow cat—and I submitted him to a terrible current from my two-hundred-cup battery. The cat disappeared in a twinkling. I hastened to the next room and, to my immense satisfaction, found Thomas there, alive and purring, although somewhat astonished. It worked like a charm."

"This is certainly very remarkable."

"Isn't it? After my experiment with the cat, a gigantic idea took possession of me. If I could send a feline being, why not send a human being? If I could transmit a cat five miles by wire in an instant by electricity, why not transmit a man to London by Atlantic cable and with equal dispatch? I resolved to strengthen my already powerful battery and try the experiment. Like a thorough votary of science, I resolved to try the experiment on myself.

"I do not like to dwell upon this chapter of my experience," continued the Head, winking at a tear which had trickled down on to his cheek and which I gently wiped away for him with my own pocket handkerchief. "Suffice it that I trebled the cups in my battery, stretched my wire over housetops to my lodgings in Phillips Street, made everything ready, and with a solemn calmness born of my confidence in the theory, placed myself in the receiving instrument of the Telepomp at my Joy Street office. I was as sure that when I made the connection with the battery I would find myself in my rooms in Phillips Street as I was sure of my existence. Then I touched the key that let on the electricity. Alas!"

For some moments my friend was unable to speak. At last, with an effort, he resumed his narrative.

"I began to disintegrate at my feet and slowly disappeared under my own eyes. My legs melted away, and then my trunk and arms. That something was wrong, I knew from the exceeding slowness of my dissolution, but I was helpless. Then my head went and I lost all consciousness. According to my theory, my head, having been the last to disappear, should have been the first to materialize at the other end of the wire. The theory was confirmed in fact. I recovered consciousness. I opened my eyes in my Phillips Street apartments. My chin was materializing, and with great satisfaction I saw my neck slowly taking shape. Suddenly, and about at the third cervical vertebra, the process stopped. In a flash I knew the reason. I had forgotten to replenish the cups of my battery with fresh sulphuric acid, and there was not electricity enough to materialize the rest of me. I was a Head, but my body was Lord knows where."

I did not attempt to offer consolation. Words would have been mockery in the presence of Professor Dummkopf's grief.

"What matters it about the rest?" he sadly continued. "The house in Phillips Street was full of medical students. I suppose that some of them found my head, and knowing nothing of me or of the Telepomp, appropriated it for purposes of anatomical study. I suppose that they attempted to preserve it by means of some arsenical preparation. How badly the work was done is shown by my defective nose. I suppose that I drifted from medical student to medical student and from anatomical cabinet to anatomical cabinet until some would-be humorist presented me to this collection as a French murderer of the last century. For some months I knew nothing, and when I recovered consciousness I found myself here.

"Such," added the Head, with a dry, harsh laugh, "is the irony of fate!"

"Is there nothing I can do for you?" I asked, after a pause.

"Thank you," the Head replied; "I am tolerably cheerful and resigned. I have lost pretty much all interest in experimental science. I sit here day after day and watch the objects of zoological, ichthyological, ethnological, and conchological interest with which this admirable museum abounds. I don't know of anything you can do for me.

"Stay," he added, as his gaze fell once more upon the exasperating legs of the Oedienenius longpipes opposite him. "If there is anything I do feel the need of, it is outdoor exercise. Couldn't you manage in some way to take me out for a walk?"

I confess that I was somewhat staggered by this request, but promised to do what I could. After some deliberation, I formed a plan, which was carried out in the following manner:

I returned to the museum that afternoon just before the closing hour, and hid myself behind the mammoth sea cow, or Manatus Americanus. The attendant, after a cursory glance through the hall, locked up the building and departed. Then I came boldly forth and removed my friend from his shelf. With a piece of stout twine, I lashed his one or two vertebrae to the headless vertebrae of a skeleton moa. This gigantic and extinct bird of New Zealand is heavy-legged, full-breasted, tall as a man, and has huge, sprawling feet. My friend, thus provided with legs and arms, manifested extraordinary glee. He walked about, stamped his big feet, swung his wings, and occasionally broke forth into a hilarious shuffle. I was obliged to remind him that he must support the dignity of the venerable bird whose skeleton he had borrowed. I despoiled the African lion of his glass eyes, and inserted them in the empty orbits of the Head. I gave Professor Dummkopf a Fiji war lance for a walking stick, covered him with a Sioux blanket, and then we issued forth from the old arsenal into the fresh night air and the moonlight, and wandered arm in arm along the shores of the quiet lake and through the mazy paths of the Ramble.

IT may or may not be remembered that in 1878 General Ignatieff spent several weeks of July at the Badischer Hof in Baden. The public journals gave out that he visited the watering-place for the benefit of his health, said to be much broken by protracted anxiety and responsibility in the service of the Czar. But everybody knew that Ignatieff was just then out of favor at St. Petersburg, and that his absence from the centers of active statecraft at a time when the peace of Europe fluttered like a shuttlecock in the air, between Salisbury and Shouvaloff, was nothing more or less than politely disguised exile.

I am indebted for the following facts to my friend Fisher, of New York, who arrived at Baden on the day after Ignatieff, and was duly announced in the official list of strangers as "Herr Doctor Professor Fischer, mit Frau Gattin und Bed. Nordamerika."

The scarcity of titles among the traveling aristocracy of North America is a standing grievance with the ingenious person who compiles the official list. Professional pride and the instincts of hospitality alike impel him to supply the lack whenever he can. He distributes governor, major-general, and doctor professor with tolerable impartiality, according as the arriving Americans wear a distinguished, a martial, or a studious air. Fisher owed his title to his spectacles.

It was still early in the season. The theater had not yet opened. The hotels were hardly half full, the concerts in the kiosk at the Conversationshaus were heard by scattering audiences, and the shopkeepers of the bazaar had no better business than to spend their time in bewailing the degeneracy of Baden Baden since an end was put to the play. Few excursionists disturbed the meditations of the shriveled old custodian of the tower on the Mercuriusberg. Fisher found the place very stupid—as stupid as Saratoga in June or Long Branch in September. He was impatient to get to Switzerland, but his wife had contracted a table d'hôte intimacy with a Polish countess, and she positively refused to take any step that would sever so advantageous a connection.

One afternoon Fisher was standing on one of the little bridges that span the gutter-wide Oosbach, idly gazing into the water and wondering whether a good sized Rangely trout could swim the stream without personal inconvenience, when the porter of the Badischer Hof came to him on the run.

"Herr Doctor Professor!" cried the porter, touching his cap. "I pray your pardon, but the highborn the Baron Savitch out of Moscow, of the General Ignatieff's suite, suffers himself in a terrible fit, and appears to die."

In vain Fisher assured the porter that it was a mistake to consider him a medical expert; that he professed no science save that of draw poker; that if a false impression prevailed in the hotel it was through a blunder for which he was in no way responsible; and that, much as he regretted the unfortunate condition of the highborn the baron out of Moscow, he did not feel that his presence in the chamber of sickness would be of the slightest benefit. It was impossible to eradicate the idea that possessed the porter's mind. Finding himself fairly dragged toward the hotel, Fisher at length concluded to make a virtue of necessity and to render his explanations to the baron's friends.

The Russian's apartments were upon the second floor, not far from those occupied by Fisher. A French valet, almost beside himself with terror, came hurrying out of the room to meet the porter and the doctor professor. Fisher again attempted to explain, but to no purpose. The valet also had explanations to make, and the superior fluency of his French enabled him to monopolize the conversation. No, there was nobody there—nobody but himself, the faithful Auguste of the baron. His Excellency, the General Ignatieff, His Highness, the Prince Koloff, Dr. Rapperschwyll, all the suite, all the world, had driven out that morning to Gernsbach. The baron, meanwhile, had been seized by an effraying malady, and he, Auguste, was desolate with apprehension. He entreated Monsieur to lose no time in parley, but to hasten to the bedside of the baron, who was already in the agonies of dissolution.

Fisher followed Auguste into the inner room. The Baron, in his boots, lay upon the bed, his body bent almost double by the unrelenting gripe of a distressful pain. His teeth were tightly clenched, and the rigid muscles around the mouth distorted the natural expression of his face. Every few seconds a prolonged groan escaped him. His fine eyes rolled piteously. Anon, he would press both hands upon his abdomen and shiver in every limb in the intensity of his suffering.

Fisher forgot his explanations. Had he been a doctor professor in fact, he could not have watched the symptoms of the baron's malady with greater interest.

"Can Monsieur preserve him?" whispered the terrified Auguste.

"Perhaps," said Monsieur, dryly.

Fisher scribbled a note to his wife on the back of a card and dispatched it in the care of the hotel porter. That functionary returned with great promptness, bringing a black bottle and a glass. The bottle had come in Fisher's trunk to Baden all the way from Liverpool, had crossed the sea to Liverpool from New York, and had journeyed to New York direct from Bourbon County, Kentucky. Fisher seized it eagerly but reverently, and held it up against the light. There were still three inches or three inches and a half in the bottom. He uttered a grunt of pleasure.

"There is some hope of saving the Baron," he remarked to Auguste.

Fully one half of the precious liquid was poured into the glass and administered without delay to the groaning, writhing patient. In a few minutes Fisher had the satisfaction of seeing the baron sit up in bed. The muscles around his mouth relaxed, and the agonized expression was superseded by a look of placid contentment.

Fisher now had an opportunity to observe the personal characteristics of the Russian baron. He was a young man of about thirty-five, with exceedingly handsome and clear-cut features, but a peculiar head. The peculiarity of his head was that it seemed to be perfectly round on top—that is, its diameter from ear to ear appeared quite equal to its anterior and posterior diameter. The curious effect of this unusual conformation was rendered more striking by the absence of all hair. There was nothing on the baron's head but a tightly fitting skullcap of black silk. A very deceptive wig hung upon one of the bed posts.

Being sufficiently recovered to recognize the presence of a stranger, Savitch made a courteous bow.

"How do you find yourself now?" inquired Fisher, in bad French.

"Very much better, thanks to Monsieur," replied the baron, in excellent English, spoken in a charming voice. "Very much better, though I feel a certain dizziness here." And he pressed his hand to his forehead.

The valet withdrew at a sign from his master, and was followed by the porter. Fisher advanced to the bedside and took the baron's wrist. Even his unpracticed touch told him that the pulse was alarmingly high. He was much puzzled, and not a little uneasy at the turn which the affair had taken. "Have I got myself and the Russian into an infernal scrape?" he thought. "But no—he's well out of his teens, and half a tumbler of such whiskey as that ought not to go to a baby's head."

Nevertheless, the new symptoms developed themselves with a rapidity and poignancy that made Fisher feel uncommonly anxious. Savitch's face became as white as marble—its paleness rendered startling by the sharp contrast of the black skull cap. His form reeled as he sat on the bed, and he clasped his head convulsively with both hands, as if in terror lest it burst.

"I had better call your valet," said Fisher, nervously.

"No, no!" gasped the baron. "You are a medical man, and I shall have to trust you. There is something—wrong—here." With a spasmodic gesture he vaguely indicated the top of his head.

"But I am not—" stammered Fisher.

"No words!" exclaimed the Russian, imperiously. "Act at once—there must be no delay. Unscrew the top of my head!"

Savitch tore off his skullcap and flung it aside. Fisher has no words to describe the bewilderment with which he beheld the actual fabric of the baron's cranium. The skullcap had concealed the fact that the entire top of Savitch's head was a dome of polished silver.

"Unscrew it!" said Savitch again.

Fisher reluctantly placed both hands upon the silver skull and exerted a gentle pressure toward the left. The top yielded, turning easily and truly in its threads.

"Faster!" said the baron, faintly. "I tell you no time must be lost." Then he swooned.

At this instant there was a sound of voices in the outer room, and the door leading into the baron's bedchamber was violently flung open and as violently closed. The newcomer was a short, spare man, of middle age, with a keen visage and piercing, deepset little gray eyes. He stood for a few seconds scrutinizing Fisher with a sharp, almost fiercely jealous regard.

The baron recovered his consciousness and opened his eyes.

"Dr. Rapperschwyll!" he exclaimed.

Dr. Rapperschwyll, with a few rapid strides, approached the bed and confronted Fisher and Fisher's patient. "What is all this?" he angrily demanded.

Without waiting for a reply he laid his hand rudely upon Fisher's arm and pulled him away from the baron. Fisher, more and more astonished, made no resistance, but suffered himself to be led, or pushed, toward the door. Dr. Rapperschwyll opened the door wide enough to give the American exit, and then closed it with a vicious slam. A quick click informed Fisher that the key had been turned in the lock.

THE next morning Fisher met Savitch coming from the Trinkhalle. The baron bowed with cold politeness and passed on. Later in the day a valet de place handed to Fisher a small parcel, with the message: "Dr. Rapperschwyll supposes that this will be sufficient." The parcel contained two gold pieces of twenty marks.

Fisher gritted his teeth. "He shall have back his forty marks," he muttered to himself, "but I will have his confounded secret in return."

Then Fisher discovered that even a Polish countess has her uses in the social economy.

Mrs. Fisher's table d'hôte friend was amiability itself, when approached by Fisher (through Fisher's wife) on the subject of the Baron Savitch of Moscow. Know anything about the Baron Savitch? Of course she did, and about everybody else worth knowing in Europe. Would she kindly communicate her knowledge? Of course she would, and be enchanted to gratify in the slightest degree the charming curiosity of her Americaine. It was quite refreshing for a blasé old woman, who had long since ceased to feel much interest in contemporary men, women, things and events, to encounter one so recently from the boundless prairies of the new world as to cherish a piquant inquisitiveness about the affairs of the grand monde. Ah! yes, she would very willingly communicate the history of the Baron Savitch of Moscow, if that would amuse her dear Americaine.

The Polish countess abundantly redeemed her promise, throwing in for good measure many choice bits of gossip and scandalous anecdotes about the Russian nobility, which are not relevant to the present narrative. Her story, as summarized by Fisher, was this:

The Baron Savitch was not of an old creation. There was a mystery about his origin that had never been satisfactorily solved in St. Petersburg or in Moscow. It was said by some that he was a foundling from the Vospitatelny Dom. Others believed him to be the unacknowledged son of a certain illustrious personage nearly related to the House of Romanoff. The latter theory was the more probable, since it accounted in a measure for the unexampled success of his career from the day that he was graduated at the University of Dorpat.

Rapid and brilliant beyond precedent this career had been. He entered the diplomatic service of the Czar, and for several years was attached to the legations at Vienna, London, and Paris. Created a Baron before his twenty-fifth birthday for the wonderful ability displayed in the conduct of negotiations of supreme importance and delicacy with the House of Hapsburg, he became a pet of Gortchakoff's, and was given every opportunity for the exercise of his genius in diplomacy. It was even said in well-informed circles at St. Petersburg that the guiding mind which directed Russia's course throughout the entire Eastern complication, which planned the campaign on the Danube, effected the combinations that gave victory to the Czar's soldiers, and which meanwhile held Austria aloof, neutralized the immense power of Germany, and exasperated England only to the point where wrath expends itself in harmless threats, was the brain of the young Baron Savitch. It was certain that he had been with Ignatieff at Constantinople when the trouble was first fomented, with Shouvaloff in England at the time of the secret conference agreement, with the Grand Duke Nicholas at Adrianople when the protocol of an armistice was signed, and would soon be in Berlin behind the scenes of the Congress, where it was expected that he would outwit the statesmen of all Europe, and play with Bismarck and Disraeli as a strong man plays with two kicking babies.

But the countess had concerned herself very little with this handsome young man's achievements in politics. She had been more particularly interested in his social career. His success in that field had been not less remarkable. Although no one knew with positive certainty his father's name, he had conquered an absolute supremacy in the most exclusive circles surrounding the imperial court. His influence with the Czar himself was supposed to be unbounded. Birth apart, he was considered the best parti in Russia. From poverty and by the sheer force of intellect he had won for himself a colossal fortune. Report gave him forty million roubles, and doubtless report did not exceed the fact. Every speculative enterprise which he undertook, and they were many and various, was carried to sure success by the same qualities of cool, unerring judgment, far-reaching sagacity, and apparently superhuman power of organizing, combining, and controlling, which had made him in politics the phenomenon of the age.

About Dr. Rapperschwyll? Yes, the countess knew him by reputation and by sight. He was the medical man in constant attendance upon the Baron Savitch, whose high-strung mental organization rendered him susceptible to sudden and alarming attacks of illness. Dr. Rapperschwyll was a Swiss—had originally been a watchmaker or artisan of some kind, she had heard. For the rest, he was a commonplace little old man, devoted to his profession and to the baron, and evidently devoid of ambition, since he wholly neglected to turn the opportunities of his position and connections to the advancement of his personal fortunes.

Fortified with this information, Fisher felt better prepared to grapple with Rapperschwyll for the possession of the secret. For five days he lay in wait for the Swiss physician. On the sixth day the desired opportunity unexpectedly presented itself.

Half way up the Mercuriusberg, late in the afternoon, he encountered the custodian of the ruined tower, coming down. "No, the tower was not closed. A gentleman was up there, making observations of the country, and he, the custodian, would be back in an hour or two." So Fisher kept on his way.

The upper part of this tower is in a dilapidated condition. The lack of a stairway to the summit is supplied by a temporary wooden ladder. Fisher's head and shoulders were hardly through the trap that opens to the platform, before he discovered that the man already there was the man whom he sought. Dr. Rapperschwyll was studying the topography of the Black Forest through a pair of field glasses.

Fisher announced his arrival by an opportune stumble and a noisy effort to recover himself, at the same instant aiming a stealthy kick at the topmost round of the ladder, and scrambling ostentatiously over the edge of the trap. The ladder went down thirty or forty feet with a racket, clattering and banging against the walls of the tower.

Dr. Rapperschwyll at once appreciated the situation. He turned sharply around, and remarked with a sneer, "Monsieur is unaccountably awkward." Then he scowled and showed his teeth, for he recognized Fisher.

"It is rather unfortunate," said the New Yorker, with imperturbable coolness. "We shall be imprisoned here a couple of hours at the shortest. Let us congratulate ourselves that we each have intelligent company, besides a charming landscape to contemplate."

The Swiss coldly bowed, and resumed his topographical studies. Fisher lighted a cigar.

"I also desire," continued Fisher, puffing clouds of smoke in the direction of the Teufelsmühle, "to avail myself of this opportunity to return forty marks of yours, which reached me, I presume, by a mistake."

"If Monsieur the American physician was not satisfied with his fee," rejoined Rapperschwyll, venomously, "he can without doubt have the affair adjusted by applying to the baron's valet."

Fisher paid no attention to this thrust, but calmly laid the gold pieces upon the parapet, directly under the nose of the Swiss.

"I could not think of accepting any fee," he said, with deliberate emphasis. "I was abundantly rewarded for my trifling services by the novelty and interest of the case."

The Swiss scanned the American's countenance long and steadily with his sharp little gray eyes. At length he said, carelessly:

"Monsieur is a man of science?"

"Yes," replied Fisher, with a mental reservation in favor of all sciences save that which illuminates and dignifies our national game.