RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

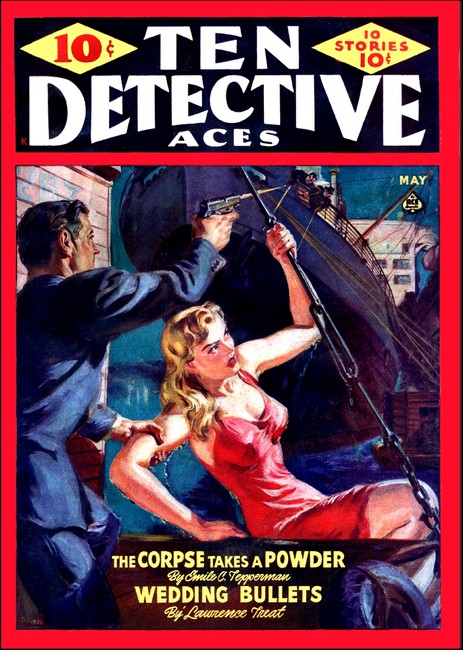

Ten Detective Aces, May 1942, with "The Corpse Takes a Powder"

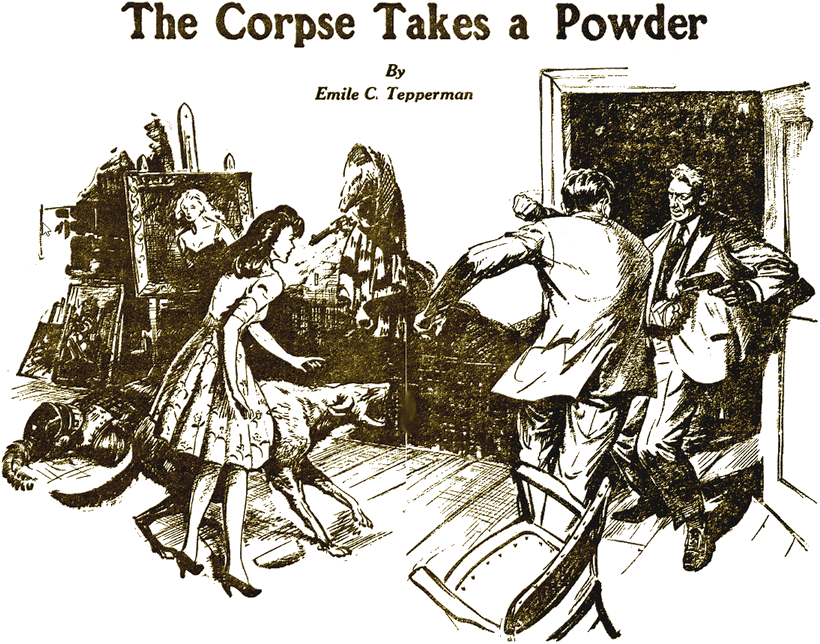

Marty threw himself forward as the gun swung up.

Photographs of a sinister killer's crimes gave Marty Quade

a homicide print to develop—for the morgue's

gallery.

IT WAS significant that on the night Nick Devons was stabbed in the back, in his own office, he didn't call the police. He called Marty Quade.

Marty got there in five minutes.

The only thing he had been able to get out of Nick's incoherent mumbling over the phone, was the impression that Nick was dying. He found the bookmaker slumped over his desk, with the knife still sticking out between his shoulder-blades, and a stream of blood soaking into his shirt.

From the nature of the wound, Marty knew that Devons should have been dead. But he was still alive, hanging on to that tenuous thread of existence by a sheer effort of will.

Marty didn't dare to move him, for fear of starting an internal hemorrhage which would kill him instantly.

He said, "Nick, you should have called the doctor, not me. I'll phone for Doc Parsons—"

Devons' eyes were closed, as if the weight of his lids were too much for him to lift. But the fingers of his right hand twitched spasmodically, and he managed a feeble croak. "No—doctor. No—use—Listen to me, Marty—I only have—a few minutes. Must talk—"

"Go ahead, Nick," Marty said grimly. "I'm listening." He bent his ear close to Nick Devons' lips, while the bookmaker forced words up through the blood which bubbled at his mouth.

"All my life—I've been working for my kid—Beatrice. She's in—Miss Hargreaves School. They don't know her old man is a—bookmaker. I was saving the Capistrano jewels—for her. They killed me—for the jewels—"

A horrible smile flickered at Nick Devons' bloody lips. "But I—fooled 'em. Gave half to Taylor Bennet, and half to Roy Gaston—to hold. Get the jewels from them—sell 'em—and give the money—to Bitsy—"

"All right, Nick, don't worry. I'll do it. But who killed you—"

Marty stopped. It was no use asking questions. Nick Devons was dead.

MARTY QUADE straightened up. Bleakly, he looked around the

office. The place had been ransacked with merciless thoroughness.

The drawers were all yanked out of the two desks, the rug pulled

up, the filing-cabinet gutted. The floor was strewn with papers

from the safe, which yawned wide open.

The autographed pictures of famous jockeys, which had hung on the walls, were lying about among the littered papers. They had evidently been removed in a search for hidden compartments. Among those pictures was one which was not of a jockey. It was a picture of an exotically beautiful woman, with coal-black hair piled high on her head, and long black eyelashes which veiled her eyes.

The picture was autographed:

With best regards to Nick Devons—

Countess Eve Capistrano.

Marty had met her several times, at the rack track. It was her

jewels which Nick Devons had spoken about with blood on his lips.

She had played high, and lost frequently, and had finally given

Nick the Capistrano jewels as security. That had been a month

ago, and she had continued to lose consistently since then, too.

Marty had seen her at the track in the company of Taylor Bennet,

the artist, and of Roy Gaston, the theatrical producer. Marty had

had dealings with Gaston, but he didn't know Bennet very

well.

He stood there, next to the desk, thinking for a moment. Then he reached over Nick's body, and picked up the phone. He dialed Roy Gaston's number, and waited. The phone rang a long time. He was about to hang up, when it was answered.

He recognized Gaston's voice.

"Hello," he said. "This is Quade."

"Marty!" exclaimed Roy Gaston. His voice was actually quivering. "I'm in a terrible jam. Nick Devons has been murdered!"

Marty's hand tightened on the phone. "How do you know?"

"Somebody just slipped a picture under my door. It's a photograph of Nick Devons, lying on his desk, with a knife in his back. The print is still wet!"

"Now listen, Roy," Marty said hotly, "don't try to hand me anything like that. If you killed Nick, by hell, I'll see that you burn for it!"

"Marty, you've got to believe me. I didn't kill Nick, but they're going to think I did. I was in his office less than a half hour ago, with Taylor Bennet. They'll say we both killed him. I'm going into hiding, and so is Bennet."

"You're crazy," Marty told him. "If you do that, you'll convict yourself. If you're innocent, why don't you face it?"

"You don't understand, Marty. It's not the law I'm afraid of. It's murder."

"Murder?"

"Yes. The ones who killed Nick will kill Bennet and me—if they can find us."

"Have you got anything that belongs to Nick?"

"Yes. And so has Bennet. What made you ask?"

"Never mind. I want it. It belongs to Nick's daughter. Stay there—I'm coming up—"

"No, no, Marty. I'm all packed. I'm getting out now. I daren't stay here another minute. It's true, about that photograph being slipped under my door. Marty, there's someone at my door now. I'm getting out the back way. Listen, you eat at Ronson's Restaurant every night this week, and I'll manage to call you there. I'll let you know where I'm hiding out. Good-by!" And he hung up.

Marty said, "Damn!" under his breath.

He clicked down the button of the French phone, and stood that way, with his finger on the button. His eyes were on the bloody streak which despoiled Nick Devons' fifteen-dollar shirt.

Nick must have lain here while the search was going on, while the killer ransacked the office—not daring to show a sign of life, lest the killer finish him off for good. He must have lain there, waiting, bleeding to death, while the killer took a flash-bulb picture, and then left—granting that what Roy Gaston said was true. Then, Nick had used his last feeble spark of life to call Marty Quade.

Marty said, "Damn!" once more. He glanced at the torn picture of the Countess Capistrano on the floor, then lifted his finger from the button, and dialed headquarters.

"This is Quade," he said. "Tell Hansen to come up here with his ghouls. Nick Devons' office. And notify the M.E.'s office. It's murder, all right!"

EDDIE, the waiter, brought in a plate of sizzling frog's legs,

fried in butter. "If that don't make your mouth water, Marty," he

said, "you ain't human. The chef saved 'em for you. They're the

pick of the day's delivery. Nice tender white meat—and done

just brown enough!"

He placed the dish reverently on the table in front of Marty Quade, and rubbed his hands. "There's one thing we don't have to start rationing," he said with satisfaction.

"Um," said Marty. He went to work on the frog's legs.

Eddie said, "Don't look now, Marty, but here come a couple friends of yours."

Marty glanced up, and groaned. Inspector Hansen had just come in, flanked by two of his men, Sergeant Boyle and Sergeant Glickstein. They looked around the restaurant, and then headed straight for Marty's table.

Eddie faded away as Hansen came up to the table, with Boyle on one side of him, and Glickstein on the other.

"Hello, Quade," said Hansen.

"Hello, Quade," said Boyle.

"Hello, Quade," said Glickstein.

Marty grunted, and took another bite of the frog's legs.

Hansen said jovially, "Hope you're enjoying your dinner, Quade."

Marty glared at him. "If you really want me to enjoy this meal—"

"Ha, ha," Hansen interrupted. "I know you—always joking. I bet you were going to say—if I want you to enjoy the meal, we should sit down—"

"Like hell."

Hansen motioned to his two satellites, and they all pulled out chairs and slipped in at the table.

"Go away," said Marty. "I haven't committed any crimes today. I'm a law-abiding citizen, eating frog's legs. Leave me alone. Go inflict yourselves on Hitler and the Mikado—"

"Ha, ha!" said Hansen. "Always joking."

"You just said that," Marty told him. He looked suspiciously at the inspector. "What have you got on your mind, Hansen? I never knew you to be so good-natured with me. What are you up to?"

"Why, Marty!" Hansen sounded hurt. "You know I think a lot of you."

"But you couldn't print it!" Marty told him. He sighed. "All right, what is it?"

Hansen chuckled. "Go ahead and eat, Quade. Don't let me spoil your dinner. I just want to ask you a couple of questions about what happened the night before last."

"I didn't do it," said Marty.

"Ha, ha!" Hansen poked Sergeant Boyle in the ribs. "He's a great kidder, this Quade. Isn't he?"

"Yeah," said Boyle. "A great kidder." He gave Marty a beseeching look, as if to say, "I'm not responsible for this. Don't blame me."

HANSEN suddenly became serious. He leaned forward over the

table. "Devons was a high-class bookmaker. He booked for a lot of

big shots."

Marty raised his eyebrows. "You don't say! Who would have thought it of Devons—"

"Lay off," Hansen snapped. "You were one of his customers, Quade. We found records in his office. We found a list of his customers, and we've checked back on them. Do you know what we found?"

"Is it a riddle?" Marty asked. "I give up."

"We found that two of Devons' customers have disappeared. Evaporated. Not only that, they disappeared on the very night that he was murdered!"

"How interesting," said Marty. He kept on eating his frog's legs, but he had become very tense.

"Now I'm coming to the part that interests you, Quade. The names of those two customers. Would you care to have me tell you—or do you know them already?"

"Why should I know the names of the two customers of Nick's who disappeared on the night he was murdered?"

"Because one of them is a very good friend of yours. In fact, he's used you on more than one occasion."

Marty put down his knife and fork. He looked straight across the table at Hansen, and met the inspector's gaze coldly.

"If you're talking about Roy Gaston—yes, I know that he's not in town. If you're hinting that Roy Gaston killed Nick Devons, you're crazier than I gave you credit for!"

Hansen was ordinarily a tough man, and as short-tempered as Marty Quade. Marty knew just what things to say to get Hansen fighting mad, and Hansen could do the same to Marty at will. Consequently, there were always sparks when the two met. Marty expected the blowup now. He actually saw the inspector's face become a dull red, and he saw Boyle and Glickstein edging nervously in their chairs, waiting for the explosion.

But nothing happened. Hansen appeared to hold himself in check by an immense effort of self-control. Slowly, the mottled color disappeared from his face.

"Another man disappeared at the same time," he went on deliberately. "Taylor Bennet, the artist. Bennet was the man who painted all the sets for Roy Gaston's musical revues. They both played the horses heavily, with Devons, and they both lost heavily."

"They didn't owe him any money, did they?"

"No," Hansen admitted. "We looked through Devons' books. They had paid their losses regularly. Pretty big amounts. And they picked nags that didn't have a chance. It almost looked as if they had wanted to lose."

"So?"

"So. I think Devons was blackmailing them. I think they kept on paying till it hurt, and then they knocked him off. How about it, Quade?"

"Sounds good," said Marty. "Why don't you write the scenario? You might sell it to Drivel Pictures, Inc."

Hansen smirked. He took an envelope out of his pocket. From the envelope he extracted a photograph. He carefully put the photograph down on the table, turning it around so that Marty could see it right side up.

"Take a good look, Quade!"

MARTY looked at the picture. It was a photograph of the body

of Nick Devons, just as Marty had found him the night before

last.

Marty raised his eyebrows. "Why show this to me?"

Hansen's eyes were glittering. "Do you know what this is?"

"I would say it's one of the photographs your boys took, of the murder scene."

"Ha!" said Hansen. "But that is exactly what it is not!" He tapped the photograph with his forefinger. "This is not an official picture. It was taken by some private person. It was taken before the police arrived on the scene, because any photographs taken by the press would show the desk cleared of all objects for finger-printing. And it would show the chalk-marks made by the boys!"

"Um," said Marty. "So this picture was taken maybe by the murderer himself, eh?"

"Either by the murderer, or by some one who knew Devons was dead before the police were informed."

"What has it got to do with Roy Gaston?" Marty asked.

And the minute he asked it, he wanted to bite his tongue off, because he saw he had stepped right into a beautiful trap which Hansen had baited for him.

The inspector's mouth quirked just a little bit, and he said slowly, "We found this photograph in Roy Gaston's waste-paper basket when we searched his apartments."

Marty had lost all interest in his frog's legs. Besides, they were cold and greasy by this time. He raised his eyes to Hansen's.

"So you think that Roy Gaston and Taylor Bennet killed Devons, took a photograph of their crime, and then left the photograph handy in the waste-paper basket, for you to find?"

The inspector shrugged. "I only want to ask Gaston and Bennet a few questions. In view of this evidence, don't you think I'm justified in wanting them?"

Marty couldn't deny the justice of that observation. He was silent.

"And so," Hansen said softly, "I am asking you, Quade, to tell me where Gaston is hiding out."

"What makes you think I know?"

"You're the man Gaston uses."

"I've worked for him on cases, yes. But they were never any of his own matters. He called me in whenever any of his actors got in a jam. But I never had a case of his own."

"Nevertheless, in a jam like this, you'd be the man he'd call."

"And what if I tell you I don't know where he is?"

For a long moment, Hansen looked at Marty Quade. Then he said, "I've got to give the devil his due, Quade. Your word is good. If you tell me that you don't know where Roy Gaston and Taylor Bennet are hiding out, I'll have to believe you."

"All right," said Marty, looking him straight in the eye. "I tell you this, Hansen, and I give you my solemn assurance that it is true. I haven't the faintest idea where Roy Gaston is at this time. The same goes for Taylor Bennet."

Hansen sighed. "I'll accept that statement, Quade, in good faith. And I hope, for your sake, that it's the absolute gospel truth, without reservations. I have two witnesses here, to what you've told me. I hope it doesn't turn out later, that there was something you held back."

Just then, Eddie, the waiter came over, carrying a plug-in phone. He plugged it into the outlet behind the table, and brought the phone over to Marty.

"Call for you," he said. "I think it's important."

"Excuse me," said Marty, to the three homicide men. He took the instrument, put the receiver to his ear, and spoke into it. "Quade talking."

"Hello, Marty," said a cautious voice at the other end. "Do you know who this is?"

Marty suddenly felt as if an ice-cube were melting, and dripping down his spine.

It was the voice of Roy Gaston.

MARTY threw a swift glance across the table. Boyle and Glickstein were just waiting, without any special interest, until he should finish his call. But Hansen was watching him like a hawk, with a thin little smile at the corners of his mouth.

Marty said into the phone, "Just a minute, Mrs. Jones." Then he covered the mouthpiece and said to Hansen and the other two, "Well, so long, boys."

"It's all right," Hansen said. "Don't worry about us. We'll wait till you're through."

Marty groaned inwardly. He took his hand off the mouthpiece. "Hello, Mrs. Jones—"

"Listen, Marty," the voice of Roy Gaston came tensely over the wire. "I'm taking an awful chance calling you. Can you talk to me?"

"Oh, no, Mrs. Jones," Marty said, looking at Hansen. "I certainly can't."

"You're not alone?"

"No. Perhaps it would be better if you called back."

"I can't call back," Roy Gaston said. "I didn't dare to use the phone in the apartment where I'm holed up, for fear it would be traced. I had to come out to the stationery store across the street."

"Why, that's fine, Mrs. Jones," said Marty. "I'll be glad to come for dinner some evening."

"Don't lose a minute. Come right away, Marty. I'm in real trouble. I didn't kill Devons. But it's not only the law I've got to worry about. The people who killed Devons have killed Taylor Bennet too, and I'm next!"

Marty wondered if his face showed any of the tenseness he was feeling. He saw that the queer smile was still lingering on Hansen's face. The inspector leaned over and whispered something in Glickstein's ear, and Glickstein got up reluctantly and hurried out. Marty knew that the sergeant had been instructed to put a tracer on the call.

Desperately, Marty spoke into the mouthpiece. "I have a couple of men here, at my table. An Inspector Hansen of Homicide, and Sergeant Boyle. I'm sure they'd both be glad to meet you, Mrs. Jones. Maybe I'll bring them out some evening, for dinner."

"All right, Marty," said Roy Gaston. "I'll make it snappy. I'm at Beasley Street, down in the Village. It's the ground floor, and the flat is rented in the name of Eve Negley. By hell, I'm so scared, I'm going to get a couple of bottles. If I stay sober, I'll surely crack up. So long, Marty, and don't fail me!"

There was a click as Gaston hung up. Marty made a wry face, and forked his receiver. He looked at Hansen and grinned.

"Mrs. Jones didn't seem to care for the idea of meeting you, inspector. But I bet if she saw you, she'd like you a lot."

Hansen grunted. "Where does this Mrs. Jones live?"

Marty waggled a finger at him. "Come now, inspector. You don't want to go chasing widows at your age!"

Glickstein came back to the table, stooped, and whispered something in Hansen's ear.

"Ah!" said the inspector. He got to his feet.

Marty glared at him. "Tracing my calls, eh?"

"Why not? It might have been from Roy Gaston. You might not have known where he was—before you got that phone call. But I'll lay you a dollar to a dime that you know now!" He smiled tightly. "We couldn't get the number, because it was a dial phone. But give us time. We can do anything if you give us time."

"So long, Hansen," said Marty. "I'm mighty sorry to see you go."

The inspector turned and headed out of the restaurant. Boyle and Glickstein went with him.

Marty followed them with a sultry glance. He could see them outside, getting into a police car. Hansen and Glickstein got in, then Marty saw Hansen speak to Boyle. The car pulled away, leaving Boyle behind.

THE sergeant moved away slowly, casually. Marty watched him

through the plate glass window until he went out of sight. But

Marty knew that Boyle hadn't gone far. Boyle would be on his tail for the rest of the night, unless Marty shook him. And the

sergeant was an old timer—a hard man to shake.

Eddie came over, looking lugubriously at the plate of unfinished frog's legs.

"I think it's a damned shame, Marty—those guys spoiling your meal. Did I do wrong to bring you the phone?"

"No," said Marty. "You couldn't help it. And I'd have had to take that call anyway. Only I would have liked to take it out of their hearing."

"I'll bring you another dish of frog's legs."

"Skip it," said Marty. "I've got to scram. Here—" he put a bill down on the table—"keep the change."

Eddie brought him his hat and coat, and helped him on with his coat, clucking sympathetically all the while.

Just then, two men who had entered the restaurant came up to Marty's table. Marty took one look at them, and his eyes got hard.

Eddie saw them, and said under his breath, "Ugh! Mace and Vallon. I'd rather sit down next to a black widow spider and a poison cobra, than next to those two!"

Red Mace was a tall man, thin and viperish. Henry Vallon was round, almost roly-poly. Anyone would have passed him off as harmless, except for the quick, sharp way his eyes moved around, as if he were ready to pounce on something at any minute. And for all his roly-poly appearance, he moved with a fluid effortlessness that fairly oozed immense strength.

Red Mace was known around town as a handicapper, while Vallon had the reputation of being a man with ready money to back anything that would return a hundred percent profit—and never mind the ethics. Mace didn't say anything as they stood by Marty's table. It was Vallon who did the talking.

"You at liberty to take a case, Marty?" he asked. "I have a nice piece of business for you."

"Sorry, Vallon," said Marty. "I'm busy. Try O'Dwyer's Agency. He's a good man."

Vallon didn't look flustered. He just stood there, seeming round and harmless beside the tall and wiry Red Mace. Only his eyes were lively and shrewd.

"There'd be a couple grand in this for you, Marty."

"No," said Marty. He put on his hat, snapped the brim down in front, and started pulling on his gloves.

"You wouldn't have to do any work for this couple grand," Vallon went on tonelessly. "You'd just have to give me a bit of information."

Marty stopped putting on his gloves. He stood very still, not looking at Vallon.

"What kind of information?"

"Just an address."

"Whose address?"

"The address of the place where Roy Gaston is hiding out!"

MARTY finished putting on his gloves. He was very meticulous

about getting them on perfectly, so that there were no creases,

and so that his fingers bent freely. Then he looked at

Vallon.

"If I know Roy Gaston's address right now," he said softly, "that means that I'm working for Gaston, doesn't it?"

"That's right."

"And if I'm working for Gaston, what kind of a heel do you think it would make me to tip anyone off to his address?"

Vallon smiled and shrugged. "Money talks, Quade. Two grand is dough, in any man's language. You can salve your conscience with the greenbacks. Tell you what—I'll make it thirty-five hundred. That's more than Gaston can possibly be paying you. You can collect from him, and from me too."

Little pinpoints of fire flashed in Marty Quade's eyes. He started to come around the table toward Vallon.

Vallon got one glimpse of the look in Marty's eyes, and started to back away hastily. And now, for the first time, big Red Mace injected himself into the picture. He stepped in front of Vallon, blocking Marty's path. He put a big hand out, against Marty's chest.

"Don't get tough, Quade," he said. "We can be tougher. Vallon wants that address. He's willing to pay for it. You take his dough and give him what he wants, or you'll give it to him without dough."

Marty had a constitutional aversion to being pawed. But he held himself in check, listening to Mace, until the big fellow got that far. Then he had heard enough. He brought his two hands up, seized Red Mace's wrist, and gave it a twist. Then he pivoted on one heel, turning all the way around, so that his back was to the big fellow. But he still kept his grip on the wrist. He yanked it over his right shoulder, and heaved.

Mace uttered a cry, and went sailing over Marty's shoulder. He landed against the adjoining table, which was unoccupied, and brought it crashing to the floor with him. He lay, there for a second, all tangled up in the tablecloth, the salt and pepper shakers, the catsup bottle, and a couple of chairs. He shook his head, rested on one elbow, and glared up at Marty, who was half a dozen paces away.

"Get up," said Marty. "I want to hear the rest of that lecture."

Mace twisted around, started to get to his knees. Then suddenly he thrust his right hand into his coat pocket, and brought it out with a small twenty-two caliber pistol.

Marty sprang forward, one long step with his left foot, then a long, loping kick with his right foot. The point of his shoe smacked wickedly against Mace's hand. The gun went spinning into the air. Mace's features became contorted with pain. His hand hung limply, broken at the wrist.

THE short fight had caused a near panic in the restaurant. Men

and women had jumped up from their tables. Some sought cover,

fearing gunplay, while others shouted for the police.

Marty Quade swung around, expecting that perhaps Vallon might try something, but he grinned when he saw that the roly-poly man had disappeared. Vallon had apparently left his companion holding the bag. Marty caught Eddie's eye. The waiter winked, and shouted over the tumult and the noise:

"Nice work, Marty. Vallon scrammed the back way—through the kitchen!"

The calls for police had brought Sergeant Boyle, who must have been loitering just a few doors down. He came swinging into the restaurant as Marty was bending over the moaning Mace, and hauling him to his feet by the back of his coat collar.

Boyle took one look at Mace, and started to grin.

"Well, well!" he exclaimed. "It looks like Tough Red has been on the receiving end this time! Who gave it to you, Mace—a small army, or just Quade?"

Mace had a cut across his left cheek, where he had struck the table in his flight through the air, and he had a lump on his forehead, where he must have struck something else when he landed. His wrist hung limp and awkward, and he was moaning softly.

Marty said modestly, "I cannot tell a lie, sergeant. I did it with my own little ax!"

"H'm," said Boyle. "Assault and battery—provided Mace wants to make a charge."

"No charge," Mace whined. "It—it was all a mistake. We—we were fooling around—"

Boyle glanced at the wreckage. "Fooling around, eh? Who's going to pay for the damage?"

Nielsen, the manager of the restaurant, had come over, and was standing quietly in the background.

He spoke up. "Thanks for bringing the subject up, sergeant. I was just wondering about that little thing."

Still moaning, Mace put his good hand into his pocket, drew out a roll of bills, and flipped off a twenty with his thumb. He thrust it at Nielsen. "I'll pay for the damage. And I'm making no charge. Forget about it."

He started to stumble out toward the door.

Boyle glanced inquiringly at Marty, then at Nielsen. "If either of you guys wants to make a charge, I'll be glad to take the mug in."

"Let it drop," said Marty.

"That's the way I feel about it too," said Nielsen.

They let Red Mace get out of the place. He didn't even stop to pick up his pistol. Boyle got it, and put it in his pocket.

"He has a license for this. I checked him on it once, myself. But I'll just take it downtown and give it to ballistics. They might turn something up."

Marty said, "Well, I might as well be going."

Boyle looked at him queerly. "Listen, Marty, guess you know I've been assigned to tag you. I've got to obey orders."

"Sure," said Marty. "And I'm going to try my damnedest to lose you, Mike. Fair enough?"

"Fair enough!" said Boyle.

Marty went out with the sergeant. Behind them, the waiters began to clean up the mess, and the patrons resumed their seats.

In the street, Marty flagged a cab. He grinned at Boyle.

"Under the circumstances, you won't mind if I don't offer you a lift?"

"Not at all," said Boyle, flagging another cab. "I'll be right behind you!"

MARTY was in no mood to waste time. Roy Gaston had given him two pieces of information which made it imperative that he get down to 15½ Beasley Street as fast as possible. The first was that Taylor Bennet had been murdered, and that Gaston expected to be next. Hansen had said that the police were equally at a loss as to the whereabouts of Bennet and of Gaston, but somebody else had found Bennet. Which meant that they knew where Roy Gaston was, too. The second piece of information was that Gaston was going to buy a couple of bottles of liquor. Marty knew well enough that Gaston was one of those men who can't hold it. Two drinks, and he'd be out cold. So Marty had to get to him quick.

Once inside the cab, he peered behind, and waved to Sergeant Boyle, in the other cab. Then he faced forward and said to his own driver:

"See that guy I just waved to?"

"Yeah."

"I made a bet with him. He claims he can follow me wherever I go, within the city limits, and I'm betting that I can lose him inside of fifteen minutes. It's only a twenty dollar bet, mostly for the sake of the satisfaction. So if you can help me win it, you can have the twenty."

The driver turned around and grinned knowingly.

"Sez you!" he smirked.

"What do you mean?" Marty demanded.

"What I mean is, I been around Broadway a long time. I know who's who, and what's what. The guy in the cab behind is Mike Boyle, homicide sergeant, and you're Marty Quade, the private dick. You might have twenty bucks to make whacky bets—but not Boyle. He's got a wife and three kids."

"H'm," said Marty. "I'm still paying twenty to lose him."

The driver shook his head. "Boyle is wise. It'll be tough. It's worth more."

Marty sighed. He looked at the clock. The flag had not been put down yet. He took out a quarter and offered it to the driver.

"In that case, pal, I'll get me another cab, with a driver who isn't such a wise guy."

"Now wait, Mr. Quade. Don't get sore. I'm just a guy trying to make a living. Isn't it worth fifty?"

"Twenty," Marty said firmly.

"Okay," said the driver.

Marty smiled. He took out a twenty dollar bill and handed it over.

"In advance," he said.

"Could you give me a ten and two fives?"

Marty shrugged. He took out his roll, selected the bills, and exchanged them for the twenty. The driver took them, put away fifteen dollars, and kept out one of the fives. All this time the driver of the cab behind had been stalling, waiting for Marty's driver to get started.

Marty's man got out of the cab, went to the cab behind, and leaned his head in at the window, talking to the other driver. Looking behind, Marty saw something change hands, then his own driver came back grinning, and got behind the wheel again.

"Watch!" he said.

He started the cab, swung down Broadway, then turned right on Forty-ninth.

"THAT'S a pal of mine in the other cab," the driver said over

his shoulder, as they traveled crosstown. "He can use the five

bucks I gave him. Boyle was a little suspicious, but I told him I

wanted my friend to give my wife a message, because you had hired

me to drive up to New Haven. Boyle said, 'Hell, is he going that

far?' And I said. 'Yeah.' In the meantime I slipped my friend the

fiver, and wised him up."

"Smart," said Marty. "Here's another sawbuck for yourself. You deserve it."

"Thanks, Mr. Quade!" said the driver. "You're a square guy!"

He turned left on Eighth Avenue, and suddenly accelerated to sixty on the stretch south. Marty looked behind. It would have been easy for the other cab to keep up with them, for there was little traffic on Eighth Avenue just now. But for some unaccountable reason, Boyle's cab was falling far behind. They made it to Thirty-fifth Street on the one light, and when they turned left again, Boyle's cab was nowhere in sight.

Marty's driver chuckled. "My pal is just explaining to Boyle that he must be out of gas. Will the sergeant be sore, or won't he?"

"He will," said Marty. "But he's a good guy. He'll get over it."

He got out of the cab, waited till another came along, and flagged it.

Twenty minutes later, and without the benefit of police surveillance, he was in the vestibule of Beasley Street, looking at the names over the bells.

He saw the name of Eve Negley. It was the one Gaston had given him over the phone. It was just like Roy Gaston, he thought, to pick a girl's apartment to hide out in. He wondered which one of Roy's chorines this one was.

In a minute he found out that it wasn't any chorine at all. Because when the buzzer answered his finger on the bell, he pushed into the foyer and saw the door of apartment 1A was being opened on a chain. Through the six-inch opening, he got a glimpse of a woman with coal-black hair and eyes, and long black eyelashes.

"I'll be damned!" he said. "Countess Eve Capistrano!"

"Come in, Mr. Quade," she said hurriedly. "Quick!"

Marty went in, and she closed the door behind him, double-locking it and slipping the chain on again.

In the little foyer, Marty looked her over appraisingly. There was nothing foreign about her except her name. The Count Luigi Capistrano had been her third husband. He had gone back to Italy six months previous, and she had secured a divorce. But she had held on to the Capistrano jewels.

She had come out of each of her three marriages with a substantial profit, and had immediately proceeded to lose the profits on the ponies. But she had the face and the figure to continue business at the old stand for a long time to come. And Marty was sure she'd find herself another husband with plenty of money—provided she didn't die a sudden death.

Sudden death was on her mind right now, as Marty could plainly see by the scared look in those dark eyes of hers. But in spite of that, she wasn't missing any tricks. She swayed toward Marty as if she were going to faint, but when Marty didn't put his arms out to catch her she stayed on her feet. She opened her eyes up wide and said:

"What a relief it is to have you here, Mr. Quade! Now I'm not afraid any more!"

Marty grunted. "What are you afraid of? I thought it was Roy Gaston—"

"They're going to kill me, too, Mr. Quade," she said dramatically. "They have marked me for death!"

"Why?"

THE countess lowered her eyes. "Because I am a friend of

Roy's. Because I am standing by him in his hour of need."

Marty gave her a disgusted look! "Have you practiced those lines long? You do them fine!"

She assumed a hurt look, but Marty didn't wait for a reply. "Where's Gaston?" he asked, and not waiting for her answer, he went into the living room. It was a one-room apartment, with a day-bed along one wall, and a recessed kitchenette along the opposite one.

"I thought you lived at the Hotel Traymont," he said.

"I do. But I—er—I've been keeping this apartment under an assumed name."

"I see." Marty said drily, looking at the figure of Roy Gaston, who was seated in the armchair, and manifestly in an advanced state of intoxication.

Roy was a foppish-looking man of about forty, with a carefully-trimmed mustache, a nicely-selected maroon necktie, and well-manicured fingernails. He was trying very hard to look sober. He peered up at Marty and said thickly:

"Hi, Quade. Damned good man. Any time in trouble—call Quade. You'll fix it. Don't let 'em kill me an' Eve—the way they killed Nick Devons and Taylor Bennet."

Marty squinted at the bottle of rock and rye on the end table at Gaston's side. There were only about three drinks gone out of the bottle, but the dirty work had been accomplished. Gaston was drunk.

Marty looked around the room, went past Gaston and peered into the kitchenette, but couldn't see the body of Taylor Bennet.

"What are you looking for?" Eve asked him. "If you want a glass, you'll find one in the closet."

"I'm not looking for a glass," Marty told her. "All I'm trying to find is the body." He went and stood in front of Gaston. "You told me that Taylor Bennet was murdered, didn't you? Well, where's the corpse?"

Roy Gaston, with his eyes almost entirely closed, began to chuckle drunkenly. "It's a good question. A damned good question. Told you Quade was a smart man. He spotted it right away. No corpse—"

The Countess Eve had come alongside Marty. Her face was pale. "Taylor Bennet wasn't living here. He's been renting a small studio two blocks away, at Twenty-nine Trent Street. He used a fictitious name—George Hervey. We—we thought it best for Roy and Taylor to separate. It would attract less attention than if two men lived together. Taylor carted some of his painting material over there one night. He was doing some painting to keep his mind occupied while he was in hiding. I posed for him."

Marty gave her a queer look. "Living here, and posing there, eh?"

She drew herself up. "It's nothing like that. I'm just letting Mr. Gaston sleep here—" she gestured toward the easy-chair—"because his life is in danger. I'd do as much for anybody."

ROY GASTON stirred in the chair, and opened his eyes again.

"Sure, sure. She'd do as much for anybody. An' her life's

in danger too. Tha's why I called you, Marty. Save her.

They'll kill her, too. Don't bother about me. I'm no damned good.

But she's beautiful. Make a good tableau for my next show. Can't

let her be killed before show opens—"

He fumbled a wallet out of his breast pocket, and thrust it uncertainly forward. "Help y'self, Marty. Take it all. Couple grand. Don't let 'em kill Eve."

He let the wallet fall to the floor, and hiccupped terrifically.

Marty scowled. He didn't pick the wallet up. Instead, he bent and shook Gaston. "Who's going to kill her?" he demanded. "How the devil can I stop them, if you don't tell me who they are?"

But Gaston was slumped in his chair, and sound asleep. Marty swung away from him angrily. He glared at the girl.

"All right, baby. You talk."

"What—what do you want to know?"

"Everything that you know. What about Taylor Bennet?"

"He's dead," she said. "Stabbed in the back."

"You saw him? You were at the studio?"

"I was at the studio this morning. I posed for two hours, and then came back here. Taylor was alive when I left him."

"So how do you know he's dead now?"

She looked at him queerly. "I'll show you—"

She went over to the table and picked up a manila envelope, about five inches by seven. From the envelope she extracted a photograph. It was still wet.

"This was slipped under the door just before Roy went out to call you."

Marty took the print. His fingers stuck to the damp matte surface. "H'm," he said. It was an enlargement of part of a photograph. The rest of the picture had been cropped out, leaving only the reproduction of a man lying sprawled on the floor in front of an easel.

The picture had been taken at such an angle as to show the dead man's face clearly, as well as the partly-finished oil painting on the easel. The whole figure on the canvas had been blocked out, showing the outlines of a woman. Only the face was finished, however. It was the face of Eve Capistrano.

As to the man on the floor, there was a knife in his back, driven in between the shoulder-blades, just like the other picture which Marty had seen in Hansen's possession—the picture of Nick Devons.

Eve was pressing close against Marty, as if for protection, while he studied the picture.

"That's in Taylor's studio," she said huskily. "I posed for the outline this morning. When I left him at noon, he—he was alive!"

Marty gave her a shrewd side glance. "Did you or Roy go there to see if Bennet's body is really there?"

She shuddered. "I should say not!"

"THAT'S fine," said Marty. "I suppose you know that you're the

one who put the finger on Bennet and Gaston?"

"Me?"

"Sure. You must have been seen in the street, and followed to Bennet's studio, then followed back here. In that way, the killer found out where both of them were staying."

There was panic in her eyes. "You won't let them kill me, will you?"

"Let who kill you?"

"Vallon and Mace, of course. It was they who killed Devons and Bennet. It's they who sent this picture. It's they who are going to murder Roy and me."

"Mace and Vallon, eh?" said Marty. "You sure?"

"Positive."

"Why? Why do they want to kill you?"

She dropped her eyes before his.

"I don't know. I swear I don't know. It—it's horrible."

She put both hands to her cheeks, and her eyes took on a fearful, hunted look. "I don't want to die, Mr. Quade. I don't want to end up with a knife between my shoulder-blades."

She moved closer to him, almost forcing herself into his arms. "Don't let them kill me, Marty. Save me. I'm afraid!"

Marty grimaced. He took her by both shoulders and held her away from him, at arm's length.

"There's a time and place for everything, baby," he said. "Right now is the time for true confessions. You better open up. You know a lot more than you're telling me."

She shook herself free of his hands, with an angry twist of her shoulders. "I don't know what you're talking about!"

"I'm talking about this and that, baby. More particularly, about the Capistrano jewels. Where are they?"

"I—I gave them to Nick Devons. He must have had them when he was killed."

"He didn't have them when he was killed. And you know it."

"Why—why should I know?"

"Skip it," said Marty. "If you won't talk, skip it."

She bit her lip. "Please—don't be so cruel to me. I don't know any more than I've told you. They're going to kill me, to stab me in the back. You must protect me. I can't turn to the police without betraying Roy's whereabouts. So it's up to you—to save me. Roy is paying you well. All you have to do is stay here with us."

Marty turned away from her, stooped and picked up Roy Gaston's wallet. There was twenty-three hundred dollars in it, mostly in hundreds and fifties. Marty took two thousand.

"That'll do for an advance fee," he told her. "I'll send him a bill for the balance—later."

Her face lighted up. "Then you'll stay—"

Marty bent over Gaston, and went through all his pockets. He was looking for the Capistrano jewels. But they weren't on him.

Marty started a methodical search of the apartment. He didn't leave a stick unturned. The Countess Eve watched him, saying nothing. Her dark eyes were fixed constantly on his back.

At last, after he had turned the entire room inside out, he gave up. He knew that the Capistrano jewels weren't in the place.

The Countess Eve said, "Perhaps if you'd tell me what you're looking for—"

Marty's eyes glinted. He crooked a finger at her.

"Come here, baby!"

"Oh, Marty!" she said. But she came over, with a sort of triumphant air about her.

WHEN she got within reach, Marty grabbed her, swung her wrists behind her. He held her that way with one hand, while he used the other to make sure she wasn't hiding any jewels on her person.

When she realized his purpose, she flushed hotly. But she didn't resist. He found a small pistol, stuck in the garter of her right stocking, but nothing else. He kept the pistol, and let go of her wrists. She slapped his face, hard. Marty grinned.

"Give me back that gun!" she flared. "I need it. I need to protect myself."

"Don't worry," he said. "I'll protect you." He picked up his hat and put it on. "Where did you say Bennet's studio was—Twenty-nine Trent?"

"But you can't go there now. You can't leave me."

"You'll be safe," Marty told her grimly.

"But Roy is drunk. I'll be all alone here. Suppose you go away—and when you come back you find me with a knife in my back. That money Roy gave you—he told you it was to protect me."

"Don't worry about the money," Marty told her. "If you get killed. I'll return the money to Roy."

"A lot of good that will do me!"

Marty grinned again. He stepped up close to her, got hold of her wrists once more, took out his handcuffs. Before she knew what he intended, he had her securely cuffed to the handle of the electric stove in the kitchenette.

"What—what are you doing?"

"Just making sure you're safe," he told her.

He patted her on the shoulder, and crossed the room. On the way he passed the chair where Roy Gaston was sleeping it off. He picked up the bottle of rock and rye, and slipped it into his overcoat pocket.

"Roy won't need this any more," he said. "I better take care of it for him." He went toward the door.

She shouted after him, "Come back, you heel!"

He unchained the door, waved to her, and went out. He slammed the door shut, and hurried into the street.

Marty crossed to the opposite side, and went into a small candy store, about fifty feet down. He used the telephone in there to call the Makin Detective Agency.

"Have you got two good men to spare right away, Lou?" he demanded of Lou Makin, whom he sometimes used when he needed assistance.

"For you, Marty? Any time!" Makin said heartily. "Provided the pay is right!"

"I'll give you twenty dollars for an hour's work."

"Twenty dollars apiece?" Makin asked cagily.

"Okay," said Marty.

"Ha!" Makin grumbled. "This is probably a case where you're grabbing off a five hundred buck fee—and you hand me forty bucks."

"You don't know a quarter of it!" Marty said.

"You mean you're getting two grand?"

"Look, Lou," Marty said impatiently. "What I'm getting is none of your damned business. I'm offering you forty bucks. If you don't want it, there are two dozen other outfits I can call—"

"It's okay, Marty!" Lou Makin interrupted hastily. "I was only kidding. You know me."

"Yeah. I certainly do. Now listen, Lou. You send those two men over to 15½ Beasley Street. Apartment 1A is occupied by a dame named Eve Negley. She has a visitor there, a man, who is a bit tight. She is under the delusion that someone intends to insert a knife between her shoulder blades, to the detriment of her good health."

"Haw!" said Lou Makin. "I'll say that would be detrimental!"

"Put one of your men in the hall in front of her door. Put the other man in the alley. There's only one other window to her apartment, and it faces on that alley. Nobody's to go in there till I get back, and nobody's to leave. Get it?"

"I get it. I'll send Schultz and Gilligan. They're in here now."

"Okay," said Marty. "I'll stay here till they come, but they're not to talk to me. They're not to let on that they know me. And listen, Lou—I'm paying you to see that nothing happens while I'm away. If I find a knife in that dame's back when I return, you don't get the forty bucks. Understand?"

"It's a deal, Marty. Schultz and Gilligan are on the way. And listen—how about making that fifty instead of forty, huh? I got my rent due tomorrow, and I haven't collected a fee for a week."

"All right," said Marty. "Fifty it is—if everybody stays alive!"

He went out and lit a cigarette and kept his eyes on Number 15½, standing where he could see both the front entrance and the alley. He didn't have long to wait, before a cab pulled up at the corner, and he saw Schultz and Gilligan getting out. They were both old-timers in the business. They separated at once, Gilligan hurrying ahead as if he had an important engagement, and Schultz loitering after him.

Gilligan glanced across the street at Quade, but did not nod. He went straight into Number 15½, and Marty could see him through the glass panel of the front, fumbling at the lock of the vestibule door. Gilligan had his skeleton keys and would get in there all right. In a moment. Gilligan's broad back disappeared from the vestibule.

In the meantime, Schultz had crossed over in a leisurely fashion. He passed by Marty, walking slowly and looking at the ground as if in deep thought.

Marty didn't look in his direction, but he said out of the corner of his mouth, "How's tricks, Max?"

"Lousy." said Schultz. "Lou hasn't paid us any salary for two weeks. He won't give us anything out of what you're paying him, either, because his rent is due."

"I know," said Marty. "That's why I held him down. This job is worth more to me. I'll give you and Gilligan each an extra twenty-five on the side—for yourselves."

"Thanks, Marty." said Schultz. "You're a regular guy!"

He turned and crossed the street, and in a moment he disappeared into the alley.

Now that he had his watchers placed, Marty turned and hurried away toward the corner, and turned into Trent Street. Number Twenty-nine was a converted studio building in the middle of the block.

LIKE many another antiquated houses in the Village, its old

brownstone front had been shaved, and then it had been given a

new facial, consisting of a limestone front and white

window-boxes. It was a three-story house and there were three

bells on the outside. The lowest bell had the name of Brasiloff,

the second had none at all, and the third had the name of George

Hervey.

Marty didn't ring the bell. If Taylor Bennet were dead, he manifestly wouldn't be able to answer the bell. Marty put his hand on the knob and turned. The door was open.

But just then there was a rush of feet behind him. A hard, unyielding object was pressed against his spine.

"Keep going, Quade!" said the soft voice of the roly-poly Ned Vallon.

Marty had no illusions about Vallon's readiness to shoot. The street was deserted, and he could easily get away. At the same time Marty knew that Vallon must want something from him. He made no effort to turn around, neither did he start to go in.

"Hello, Vallon," he said over his shoulder. "You do get around, don't you? Too bad you didn't stay for the fun at Ronson's Restaurant."

"Let's not talk out here," Vallon said suavely, pushing just a little harder with the revolver at Marty's spine. "I suggest we go upstairs."

"All right," said Marty. "Since you put it so politely."

He pushed the door open, and stepped into the hall. The gun remained touching his back. Vallon was keeping step for step with him.

"Now look, Quade," Vallon said reasonably. "I know just how fast you are with a gun. I know you have one in your shoulder holster, and that you're just wacky enough to try to pull it. Please don't. I ask you as a favor, please don't."

"I'll think it over," said Marty.

"All right. Let's go upstairs. Do I have to tell you I'll shoot the minute I think you're starting something?"

"No," said Marty. "You don't have to tell me. But I'm surprised you're using a gun. I thought a knife was more in your line."

"I don't know what you're talking about," Vallon said, his voice suddenly becoming dangerously smooth.

"Skip it till later, then," Marty said. He started up the stairs.

The door of the top floor studio was wide open. From the landing Marty had a view of the interior. The easel with the oil painting of the Countess Eve was in full view, in the center of the skylighted room, just as it appeared in the photograph which she had shown him. But there was no body in front of the easel.

Everything seemed to be in perfect order as Marty stepped inside, with Vallon close behind him. There was an oriental throw rug on the floor directly in front of the easel, but there was not a drop of blood upon it.

Two indirect-lighting fixtures were burning brightly, as if the occupant had just stepped out for a moment. The place was a litter of odds and ends, an assortment of queer props which an artist might be apt to use. Taylor Bennet must have rented the place furnished, from some artist who did covers for horror and adventure magazines. There were several oil canvases hanging on the wall, apparently rejected covers.

A TEN-GALLON hat hung on a peg, with an old-time Colt .45

alongside it, while on a row of hooks in a makeshift closet

without doors there were costumes of various kinds for models to

use. The other walls were decorated with old carbines, sabers, a

spear and a mace. In one corner there stood a full suit of armor,

with a spear and a shield upon which appeared the white cross of

a knight of Malta.

But there was no corpse. Marty felt the hard muzzle of the gun in his spine, and Vallon said smoothly, "Now, Quade, let's talk business."

"Sure," said Marty, without turning around. "The last time we talked, you asked me for Taylor Bennet's address. All right, I'm glad to oblige. The address is Twenty-nine Trent Street."

"Let's not get funny, Quade," Vallon murmured. "I don't need Bennet's address any more, or Gaston's, either."

"As a matter of fact, Vallon, isn't it true that you never needed them? You knew all along where they were hiding out."

Vallon laughed softly. "Would I have approached you in the restaurant if I had known?"

"You did that for effect, Vallon. Purely for effect."

"Effect? On whom?"

"You did it for effect on Red Mace. Mace was working with you, but you were double-crossing him. You wanted him to believe that you didn't know where to find Gaston or Bennet. In fact, you didn't try very hard to get the addresses from me. If you had wanted me to talk, you wouldn't have tried to bribe me. You knew I'd get sore at you. You wanted it to turn out just the way it did—so you could be free to operate without Mace at your elbow for a couple of hours."

"You're pretty keen, aren't you, Quade? Maybe you know what I want now?"

"Sure. You want the Capistrano jewels."

Vallon's voice was suddenly hoarse. "Where are they?"

Marty chuckled. "I should tell you, eh—so you can knock me right off?"

"Look, Quade," Vallon said impatiently. "I've done a lot to get my hands on the Capistrano jewels. They're worth a quarter of a million dollars. Just twenty-seven stones, but they're perfectly matched. Mace and I were Nick Devons' silent partners. We had as much interest in the Capistrano jewels as he had. But what does he do? He earmarks them for his kid!"

"So you killed him!"

"Never mind who killed him. I want the jewels. I've got a buyer waiting for them, with cash. Figure it out for yourself. Will I stop at anything now?"

"The worst you can do is kill me," said Marty.

"I think you're wrong there, Quade. This house is unoccupied. That name in the downstairs bell is a phony. I have that apartment. Nobody comes here."

"But they'll come," Marty told him over his shoulder. "They'll come when the Capistrano dame squeals to the police—"

"Never think it!" Vallon interrupted. "That Capistrano dame, and Roy Gaston, will stay holed up in the apartment on Beasley Street till the cows come home. They're scared of their shadows. So I'll have a long, long time to work on you. You're a strong man, and you can stand a lot of pain."

"But I don't like to, if I can avoid it," said Marty.

"Ah! So you're ready to talk sense!"

"Sure," said Marty. "Sure. I'm always ready to talk sense."

MARTY twisted around swiftly, swinging his right arm behind

him in a vicious, driving jab. He had nothing to lose, because he

knew that in Vallon's plan, there was no place for Marty

Quade—alive. The worst that could happen to him this way

was a bullet in the back.

But Vallon hadn't been expecting anything like that. Marty's driving elbow caught his gun wrist, sweeping it away from Marty's back. Vallon's exclamation of dismay was drowned by the sharp report of the weapon. The bullet cut a furrow in Marty's coat, and buried itself in the opposite wall. But Marty was already completing his turn, pivoting on his right foot. He brought his left around, putting everything he had into it, and his bunched fist cracked nastily against the side of Vallon's jaw.

Vallon was staggered sideways by the blow, and something seemed to be the matter with his jaw. But the spiteful anger in his eyes lanced out at Marty as he reeled away, raising the revolver for another shot.

Marty stepped in swiftly, and brought the edge of his open hand down sharply on the other's wrist. The gun went flying out of Vallon's hand, and fell to the oriental rug.

That reeling attempt to shoot had been Vallon's last conscious effort. His jaw was broken, all right. He stood there for a moment, teetering on his feet, then he seemed to deflate. He fell over, landing on his side. He rolled onto his face, and lay quietly, sunk in deep sleep.

Marty rubbed his knuckles. He didn't wonder that Vallon's jaw was broken, from the way his hand felt. He heard a patter of footsteps, light and fragile, running up the stairs. And then a slip of a girl appeared in the doorway, breathless and flushed.

Taking a quick look at her, Marty wouldn't have given her a day over sixteen. She was wearing a knee-length corduroy skirt, and a yellow sweater under a short beaver coat. She was a pretty little thing, with auburn hair and light blue eyes, and a small quivering mouth.

A huge police dog loomed beside her, spare and powerful. It came almost to the girl's shoulders. The dog, on a leash, kept close to the girl's side, as if to protect her from anything and everything. Its small, ugly eyes were fixed upon Marty with an intent and vindictive stare.

The girl's bosom was heaving beneath the sweater as she tried to catch her breath. Her gaze went to the quiet figure of Vallon, adorning the oriental rug. She uttered a little ejaculation of dismay. Then she raised her glance to Marty, and gave him a look which flashed fire.

"You beast!" she cried. "You've killed poor Mr. Vallon!"

She didn't wait for Marty's answer. She stooped swiftly and unhooked the police dog's leash. Then she pointed at Marty.

"At him, Berengaria!" she ordered sharply.

THE dog growled deep down in its throat. Its eyes were flecked slightly with red as it started to move toward Marty. It stopped, less than three feet from him, and bent its hind legs, preparing to spring at him.

Marty shouted to the girl, "Call that animal off!" He drew his automatic from its shoulder-holster. "Call that dog off, or I'll have to kill it!"

The girl in the doorway paid no attention to his plea.

"Go on, Berengaria!" she urged. "Go get him. He hurt Henry!"

The dog growled again.

Marty swung his automatic down, so that the muzzle pointed at Berengaria's mouth. "I hate to shoot an animal like that—"

He broke off abruptly, staring at the dog. The animal had suddenly begun to act in a strange and puzzling manner. It started to sniff all around the edges of the oriental rug, avoiding the lax figure of Henry, and uttering queer whining noises as it sniffed.

In a fraction of a second, it had forgotten all about Marty, all about its mistress' command. It turned its head and looked at the girl, sniffed once more at the rug, then sat up on its haunches and began to howl most dismally. Marty stared at the creature, lowering the gun. The girl in the doorway came slowly into the room.

"Berengaria!" she demanded sharply. "What's the matter?"

The dog continued to howl. Marty looked at the girl. He saw that her face had suddenly become white.

"I never heard a dog howl," he told her, "except for one reason."

Her eyes, wide and frightened, swung away from the dog.

"Yes," she whispered. "Yes, I know. They howl for the dead!"

The dog was running around in circles now, whining and howling by turns. It stopped abruptly before the suit of armor in the corner. Springing up, the dog seized the lower end of the lance in its teeth, and dragged at it. The suit of armor began to topple forward. The dog sprang out of the way, just in time to avoid being hit by the crashing metal.

The armor struck the floor and split open. Shield, breastplate, lance, helmet, jangled in all directions. And there, lying under what was left of the armor, was the body of Taylor Bennet. The knife was still there, between his shoulder blades, just as Marty had seen it in the photograph.

The dog backed away from the dead body, all the way over to the window. It lay down flat on its stomach, with forepaws extended, howled once more, and became silent. The girl in the yellow sweater stared at the corpse. Then she pointed an accusing finger at Marty.

"You killed him!" she exclaimed.

Marty holstered his gun. "Listen, sister," he said impatiently. "You're just a kid. Where do you fit into this picture?"

"I'm Bitsy Devons!" she said defiantly.

"Ah!" said Marty. "Nick Devons' kid! I'm Marty Quade."

Her eyes widened. "Then—then you couldn't have killed Bennet—and—and Mr. Vallon here."

"Don't worry about Vallon," Marty said dryly. "He's not dead. He just has a busted jaw. What I want to know is, how come you're here? You're supposed to be at that swanky Hargreaves School."

"I received a note from Mr. Bennet yesterday," the girl explained. "He told me about dad's murder. Nobody knew about me, so I wasn't even notified when dad—when dad was killed. But Mr. Bennet told me in the note that he and Mr. Gaston had some jewels that dad had given them to hold for me. He said that he was in fear of his life, and he wanted me to come here tonight and get the jewels. He said he'd tell me where to go to get the other half."

"H'm," said Marty. "And you came?"

She nodded. "Miss Hargreaves refused me permission to leave, but I climbed out the window, and got Berengaria, who is the school mascot. I took the bus and got here an hour ago, and Mr. Vallon met me downstairs. He told me that a man was coming here who was very dangerous, and who intended to kill Mr. Bennet.

"He said that Mr. Bennet had left, fearing to wait for that dangerous man." She pointed her finger at Marty. "He meant you. Vallon said that I was to hide with Berengaria on the lower floor, and after he had got rid of the man, he would take me to Mr. Bennet."

Marty laughed harshly. "Vallon had already killed Bennet. I bet he has Bennet's half of the Capistrano jewels."

He knelt swiftly beside the unconscious man, and went through his pockets. It was in the inside breast pocket that he found the little pouch. It was of chamois, and when Marty poured the contents out on the palm of his hand, Bitsy Devons gasped. Fourteen pearls gleamed, like rare hothouse plants. Their beauty was so delicate and fragile that he dared not pick one up between his fingers, lest it dissolve.

"They—they're marvelous!" Beatrice whispered.

"I'll say so," Marty told her. "Together with the thirteen, stones Gaston is supposed to have, they're worth a quarter of a million dollars. Two men have died for them, that I know of—and only the Lord knows how many others have died in the past."

Suddenly a voice spoke from the doorway. "Looks like there's more deaths coming up, Quade!"

Marty jerked his head up.

Big Red Mace was standing in the doorway, looking uglier than ever, with his face plastered where he had been cut in the restaurant brawl with Marty, and with his right wrist in a splint. But in his left hand he held a burnished automatic, and on his face there was a nasty leer.

"I told you I'd catch up with you, Quade!" he said. He kept the gun pointing at Marty, and glanced at Beatrice Devons.

"I'd just as lief shoot you as Quade," he warned. "So don't make a move I might not like!"

Marty gave him a crooked smile. "Vallon almost double-crossed you out of these stones, didn't he, Mace?"

Mace's eyes were narrow, vindictive. "I'm gonna kill you, Quade. And the girl, too. I'm taking those pearls. I know where to get the rest of them, too. Think about that for a minute, before I put a bullet in you. I'll be spending the dough for those pearls, while you push up stink-weed!"

Marty saw the tight, tense look in Mace's eyes.

"Let the girl go, Red," he said. "She never hurt you."

"Can't," said Mace. "She could talk. When I finish with this, there won't be anyone to talk—except Vallon, and they won't believe him, because they'll have him cold for all these murders. So here goes—"

Marty was all set to fling the pearls in Mace's face, and to jump him, when there was suddenly a low growl from over near the window. Mace jerked his eyes in that direction and saw the dog.

"What the hell—"

He was interrupted by Bitsy's high-pitched voice: "Go get him, Berengaria!"

The dog came leaping out of its corner, its long back arcing gracefully in the air, its fangs bared.

Red Mace cried out a choked curse, and swung his gun at the leaping dog. His finger was on the trigger, and the muzzle was lined up with the faithful beast's head. In another instant, Berengaria would have been dead in mid-air.

MARTY threw himself at Mace, sending his hundred and eighty

pounds crashing into the gunman's side. He threw Mace off

balance. The automatic exploded, but the bullet was deflected,

and crashed through the window pane. But now, Berengaria reached

her goal. Her teeth sank into Mace's outstretched arm, and the

man screamed as the powerful fangs ripped skin and flesh, down to

the bone. He dropped to the floor, squirming and shrieking, with

the dog tenaciously worrying at him.

Marty got an arm lock on the dog's head. With his own revolver muzzle Marty pried open Berengaria's teeth, dragging them out of the wound.

Bitsy was helping him, with her hand twisted in the dog's mane, talking to it, and dragging it off the kill. Finally, between them, Marty and Bitsy got the dog off Mace. The gunman sank back on the floor, almost alongside his partner, Vallon, and kept on moaning.

A police whistle had sounded while the struggle had been going on, and heavy feet pounded on the stairs. In a moment. Inspector Hansen burst into the room, followed by Sergeant Glickstein, Sergeant Boyle, and two uniformed men. Hansen stood with his hands on his hips, surveying the room.

"What the hell goes on here?" he demanded.

Marty was sitting on the floor, pulling pieces of the broken rock and rye bottle out of his pocket. He said ruefully:

"This is what I get for indulging in violent exercise. The bottle broke!"

He looked up, and winked at Hansen. Then he saw Roy Gaston and the Countess Eve coming into the room behind Hansen, together with Schultz and Gilligan, both of whom looked sheepish.

Marty got to his feet, pulling bits of glass and lemon and orange peel out of his pocket. He swished off his hand, which was wet and sticky with sweet rye whisky.

"How did you get on to Gaston's hideout, inspector?" he demanded.

Hansen smiled sourly. "Your friend, Lou Makin, tipped me off. It seems he got to thinking things over, and wasn't satisfied with the deal you gave him. He figured he was entitled to more than fifty dollars, when you were collecting two thousand. Then he heard about the hunt for Gaston and Bennet, and put two and two together. So he called me up and tipped me that you were interested in 15½ Beasley Street. Naturally, I didn't lose any time."

"Naturally," said Marty.

"And now," Hansen said portentously, "maybe you can square yourself. What have you to offer?"

Marty waved a hand around the room. "First, meet Miss Beatrice Devons, Nick's daughter. And that is Berengaria, who damned near saved our lives just now. On the floor here you have one corpse, representing Mr. Taylor Bennet, and one near-corpse, known as Henry Vallon. This other thing alongside of Vallon is Red Mace. You can arrest them for the murder of Nick Devons and Taylor Bennet."

"H'm," said Hansen.

Marty looked at Eve Capistrano, and saw that she was handcuffed to one of the detectives. He raised his eyebrows.

"Confessed, eh?"

Hansen said, "She talked when I got tough with her. She was working with Vallon and Mace to get the Capistrano jewels back. But she intended to double-cross them both. She alone knew where Gaston and Bennet were hiding out, and she planned to let Vallon and Mace take the rap for Nick Devons' murder, and scram with the jewels. She was only sticking with Gaston till she could find where he had hidden his half. Vallon had learned that she planned to cross him, and that's why she was afraid of getting a knife stuck in her."

"I figured it that way," Marty said, "which is why I handcuffed her to the stove."

"All right, all right," Hansen said. "But where the devil is Gaston's half of the jewels? I see Bennet's half—scattered here on the floor. But I searched the whole apartment and can't find the ones Gaston hid. He can't remember, either. He was so drunk, he has no recollection of where he put them!"

Marty Quade smiled. He looked at Roy Gaston, who shuddered. His lips twisted wryly.

"I hope to heaven I didn't throw them down a sewer or something," Roy Gaston said. "I'd have to make up their value out of my own pocket."

"Don't worry," said Marty. "I got them."

The Countess Eve exclaimed, "You didn't get them. I was watching you like a hawk while you were in the apartment. You didn't get them—"

"When I finished searching," Marty went on imperturbably, "I realized that there was only one place Gaston could have hidden the pearls. I didn't have time to look, so I took the whole bottle along. And now it's busted."

Out of his pocket, wet and soggy, he began pulling pearls, one after the other, until he had thirteen of them in his hand.

"Well, I'll be damned!" said Roy Gaston. "Was I smart enough to put them in there?"

Marty chuckled. "It's a good thing you didn't take another drink out of that bottle. We'd have had to open you like an oyster!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.