RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

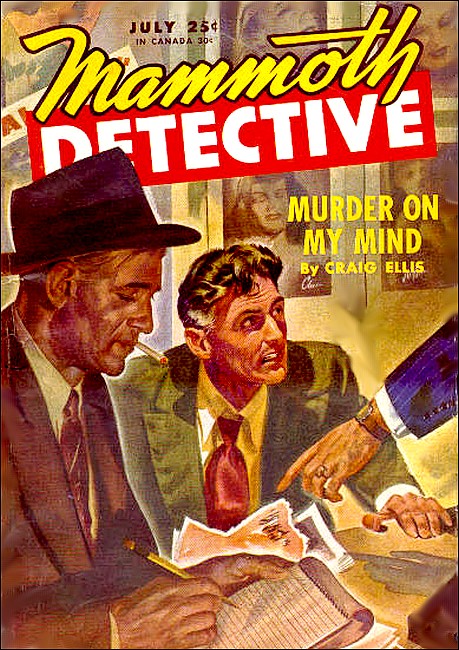

Mammoth Detective, July 1946, with "Till Death Do Us Part"

"No!" she cried. "No, darling! You don't understand...."

Something terrible lurked beneath the surface of

their lives—and each sought to protect the other.

STANDING in the doorway of the darkened shop, he watched the rain slash furiously from blackened skies, and turned his collar to shield his gaunt cheekbones from the dampness.

He was a tall man, thin and hatless. His hair was dark, plastered wetly, now, against his skull. He was dressed well in studiedly careless tweeds, and had it not been for the almost emaciated appearance of his wide, bony frame, he would have been extremely handsome.

When he saw the girl running through the darkness across the shining ebony of the rain-soaked street, faint interest came to his dark somber eyes, and somehow his heart quickened its beat as he realized she was headed for the shelter of his doorway. He was a lonely man, and in the cold vastness of this rain-swept city he was able to find warmth in the thought of proximity to any stranger.

The girl stood in the doorway, a few feet from him, shaking the rain from her slicker, brushing it from the lustrous raven black of her hair. It was several minutes before she realized his presence. He watched her quietly until she turned, saw him, and spoke.

"It's a horrible night, isn't it?"

Her voice, he thought, was lovely. Soft, throaty, with a melancholy undertone that was warmth to his mood.

"I rather think," he said quietly, "that we've missed the last bus. I've been waiting here almost half an hour now."

The girl made a small sound of disappointment. He could see her face more clearly, now. Delicately ovaled, olive-tinted complexion, darkly hypnotic almond eyes, a soft, sad crimson flower of a mouth.

"I've had my eye out for cabs," he added. "Not much luck there, either."

"You look soaked through and through," she said sympathetically. "And cold."

"I am, I suppose," he admitted. He gathered his courage, then, as he glanced at the lighted all-night restaurant across the street at the far end of the block. "You don't look completely comfortable, either. Perhaps we could make a dash for that restaurant over there. Coffee would warm us both, and we could telephone for a cab."

She smiled, and he felt suddenly bewilderedly glad.

"That's a good suggestion," she said.

And that was how they met.....

AT every possible opportunity in the week that followed,

they were together. Each evening he waited outside the dress shop

where she was employed, and they went off to dinner together,

then to the theater, or to her snug, comfortable little two room

apartment. Within a few days they were meeting for lunch, after

which there would be brief, wonderful walks in the park.

In these few days, the cloak of his loneliness fell miraculously from him. For the first time in many years he found himself able to give himself to another. He told of his youth, his days in college. He spoke at length of the several novels he had already had published, and confided in her his plans for those to come.

It was incredible how much they had in common. Their tastes in books, the theater, art and music, food and wines. They laughed little, for he had long ago lost the touch of laughter, and she was seldom given to it. Yet there was complete joy in their nearness to one another.

When he proposed, exactly seven days later, there was a pounding in his heart and a constriction of his throat that almost left him mute. His hand trembled so badly that he dared not touch hers.

She didn't seem surprised. There was no artificial coyness to her. She looked at him steadily with those hypnotic almond eyes, her red petaled mouth soft and tenderly unsmiling.

"You know absolutely nothing about me," she said. "It's been only seven days. I feel as if I'd known you forever. You've told me everything about yourself. And yet, I've told you nothing of myself. It—it isn't fair to you for me to say yes."

Fiercely he brushed this aside, his expression impatient.

"What difference does it make?" he said. "You say I know nothing about you. Why, I know everything about you that matters. You're warm, and sweet, and lovely. I love you more than life itself. That's all that matters."

For answer she smiled one of her rare smiles, and reached across the table to place her small cool hand in his. His heart was almost too achingly ecstatic to beat.

"Tomorrow," he said, "I'll get the license first thing. We can be married at noon. By evening we can be on our way to my little country place. Does that sound all right?"

"That sounds like heaven," she said.....

HE slept badly that night. For the first time in several

weeks, his illness returned and he was shaken by one of its

breathless attacks. He was in the bathroom, getting a glass of

water, when the seizure took place. He felt the familiar dizzying

numbness, the pounding in his temples. The room began to blur,

and he was barely able to grope his way to the bed before he lost

consciousness. When he woke, the sunlight was pouring through the

windows of his room, and the clock on the dresser told him it was

almost nine.

He sat up quickly, panic filling his heart. When had he promised to meet her? Then he realized they would just have time to get the license, the ring, and—

He remembered the seizure, then, for the first time since waking. A sick fear stabbed his heart, and he put his hands to his temples. She had said she knew everything about him. But he had not told her of this. He had meant to, had tried to find the courage half a dozen times. But he had concealed it, subconsciously fearing that such a revelation would forever keep her from him. He had been filled with the fear that she'd never have him if she were aware that he was invalided. And he had, himself, no certain knowledge that it would not grow worse. That he had taken her into a promise which might eventually leave her tied to a helpless, bedridden invalid of a husband, was a suddenly aching fear.

"But she must realize that I'm not completely well," he told himself. And slowly he forced the fear from his mind and buried it again in his subconscious. By the time he was dressed, he knew that he was not going to tell her. Later, perhaps, if the attacks continued to occur—if he grew no better, if the specialists he planned to see could not help him—he would tell her.

She was waiting for him, two hours later, in front of the tiny neighborhood church they had chosen for the ceremony. She was as lovely as a thousand angels.

The minister's words were a melodious, meaningless drone as they stood before him. And they were repeating:

"Until death do us part....."

Walking from the church, with her hand on his arm, he moved lightly over an aisle of cloud.....

THEY had driven most of the afternoon and into the early

evening before the darkening sky was split by the first bolt of

lightning. Moments later raindrops drummed light fingers on the

windshield, and he stopped to put up the top of the

convertible.

"At least we'll be snug and dry," he said, as they resumed their journey.

"I don't mind the rain," she said solemnly. "In fact, I think I love it. It brought us together, you know."

Later, when the storm had reached torrential proportions, he said:

"It's not much farther. A few more miles and we'll come to the village. My place—I mean, our place—is at the edge of the town. I do so hope you'll like it."

They reached the little village abruptly, with no forewarning. It was like an etching of any one of a hundred New England seacoast towns.

"Near midnight in the midst of a storm is hardly a good time to show you the place," he said. "But we'll have all tomorrow to get you acquainted."

When they woke in the morning the sunlight was warm as it flooded through the windows of the bedroom, and outside the birds were caroling tribute to a perfect day.

His happiness was almost boyish at the delight she expressed over the snug, pleasant comfort of their home. Proudly he escorted her through every corner of the house, pointing out this and that item which he'd expressly purchased and forwarded to the place ahead of their arrival.

He took pride in the lovely little garden behind the house, and in exhibiting his comfortable little summer cottage beyond, equipped with a tiny workshop where he carried on his hobby of wood sculpture, and a book-lined den in which he planned to work on his new novel.

They drove the mile and a half into town, then, to purchase groceries and to introduce her to the quiet little village for the first time. Again his happiness was full as she expressed her pleasure over the peaceful little town.

He had peace and contentment and companionship for the first time, now, in longer than he cared to remember.

Returning from town, early in the afternoon, she carried the armloads of groceries and odds and ends into the house, while he took their heavy luggage from the trunk of the car and carried it upstairs to the bedroom.

He could hear her preparing luncheon in the kitchen downstairs, and smilingly decided to surprise her by opening the luggage and putting away most of their clothing.

He had been busy about five minutes at this—hanging her dresses in the closet, placing her shoes on the floor, hats on the shelf—when he opened the small, tan-leather suitcase that contained the gun.

It was a small, pearl handled revolver, incongruously enfolded in a frothy lace chemise.

He stared at it first in bewilderment, then with a strange prickling feeling of uneasiness.

A quick search of the side compartments of the suitcase revealed a small box of shells of the caliber to fit the weapon.

Very carefully, he lifted the gun from the folds of the chemise and held it in his right hand, speculatively. In his left hand he felt the compact weight of the box of cartridges. His heart was beating more rapidly than was good for him, and he knew that the alarm tingling along his spine was silly, senseless.

"I'm being a damned fool," he told himself uncertainly. "For a girl living completely alone in a large city, such a possession surely isn't hard to understand. I—I'm thinking and acting like an ass."

He forced himself to put the gun and the box of cartridges back where he'd found them. Then he closed the bag, deciding, self-consciously, not to unpack it, not to mention having opened it, or having seen the gun.

"Good Lord," he told himself. "I don't want her to think I'm sort of a prying, suspicious fool. She'll tell me about it, of course, when it occurs to her."

But she didn't tell him about the gun. Not, at least, during the wonderfully happy week that followed, the week in which they laughed through sunny days and cool, star-filled nights. There were walks, and picnics, and afternoons under the hot sun on the white sands of the beach, evenings in the cool comfort of the garden. And he might have forgotten about it completely—at least have shrugged it away from any further thought or concern—had it not been for the stark tragedy that struck the little village on the eighth day of their new happiness.

THE day was marked by the first bad turn in the weather in

a week. Sometime in the early morning hours a storm had gathered,

and by dawn a steady, incessant downpour swept over the

countryside from the canopy of gray, ominous clouds that blotted

out the sun.

Their breakfast was later than usual, and without enthusiasm, as if the dampness had smothered the spark of their carefree good spirits.

When the breakfast dishes were done, she suggested that it might be wise for her to drive to town for groceries earlier than she usually did.

"If this rain keeps up, the roads will be badly bogged by later afternoon," she said. "I really ought to start out now."

He agreed, offered to drive to town to save her the trouble. But she brushed aside his offer with a smile, promised that she wouldn't be long, and would take no unnecessary risks.

She had been gone half an hour, and he had finished shaving when he decided to do a little work on his novel in her absence. There were some notes on his planned first draft he had to straighten out, and several aspects of the outline he wanted to give more careful consideration.

The house seemed cold and empty without her, and he decided to work in the summer cottage. There was a small fireplace in the den and he could work comfortably there until she returned.

He threw a topcoat over his shoulders as he left the house to cross the yard to the summer cottage. It was little more than fifty yards beyond the garden, back in a cluster of pines, but the ground was already sloppy underfoot, and the incessant rain was chilling, and his teeth chattered involuntarily as the dampness of the morning closed in around him.

He was halfway across the garden when he felt the first frightening symptoms of his illness. There was a sense of dizzying loss of equilibrium, the numb throbbing of his temples, the breathless constriction near the muscles of his heart.

The rain veiled landscape blurred before his eyes as the seizure shook him with its violent tremors. And then he knew that his knees were buckling, and that the muddy earth was rushing up to meet him, and blackness pressed in upon his consciousness from every side. The last thing he remembered was his effort to call his wife's name, and a muddled realization that she was beyond the sound of his voice.....

WHEN consciousness returned he was aware first of the icy

chill that had saturated to the very marrow of his bones. And

then he realized that he lay face forward in an ooze of frigid

mud.

It was still raining, and his clothes were soaked, and plastered to his long, thin body.

Swaying dizzily from the exertion, aching stiffly in every joint as he did so, he forced himself to rise.

He saw the summer cottage, then, a few yards away. Behind him was the house. He realized that he had been considerably more distant from the cottage when the attack had seized him, and knew, then, that some instinct must have enabled him to walk or crawl toward the sanctuary of the summer house during some period of his unconsciousness.

He wiped the slime from his face and hands with a handkerchief he found in the water-soaked pocket of his topcoat. Then he looked at his watch. It was almost one o'clock. He'd been seized by the attack shortly after ten that morning; more than three hours had elapsed.

Suddenly he realized that she would be returning from the village at any moment. Swift panic seized him. He couldn't let her know what had happened. He had still to tell her of his illness, and was frightened at the thought of having her find him like this, and of having to explain while still suffering the aftermath of the inexplicable malady.

As quickly as he could, he hurried into the house. He had peeled off his soaked and mud-stained clothes and was standing beneath a hot, miraculously restoring shower, when he heard the sound of their car turning into the driveway.

Panic left him with the realization that he was now safe with his secret. He'd be able to invent some plausible explanation for his soaked, muddied clothing, and she'd never know how helplessly he'd been felled by his affliction.

The steaming needles of the shower massaged his aching body, and he was comparatively relaxed when he heard her enter the house and call his name.

His shouted answer was normal, as was her admonishment not to linger too long in the bath, for fear of catching cold in the dampness of the house.

"You didn't build a fire," he heard her call. "The place is as chilly as a cave."

When he joined her downstairs, coffee was percolating on the grill, and the pleasant tang of cheese and bacon sandwiches toasting in the oven filled the kitchen.

She had started a blaze in the living room fireplace, and moments later they lunched there in the comfort of the overstuffed chairs he drew up before it.

During their casual small-talk, he was able to mention, carelessly and with a wry laugh, the nasty spill he'd had when he slipped on a bad stretch of mud crossing the garden. He felt pleased with the neat offhand manner in which he had covered her ultimate discovery of his sodden clothing.

THE rain persisted through the rest of the afternoon, even

growing somewhat more intense as night came. An electrical storm

joined the unpleasant display of the elements, and thunder

cracked guttural snare-drum warnings of increasingly severe storm

gatherings.

He noticed her restlessness shortly after dinner.

They were sitting in the living room, and he was trying unsuccessfully to tune out the static in the small radio on the book case by his chair.

"I wish you'd turn it off and forget about it," she said irritably.

He obliged her instantly, snapping the switch off.

"I'm sorry, darling. Just thought music might be nice. No need to bite my head off."

She tossed the book she'd been reading aside.

"This ceaseless rain drives me frantic," she said. "Doesn't it ever stop?"

"But you said once before that rain didn't bother you," he declared bewilderedly.

"Not a little rain," she said. "Not even a day of it, or a night. But a morning, afternoon, and evening of rain, with never a let-up, is something else again."

He rose, crossed to her chair, and dropped to his knees beside her, stroking the lustrous ebon softness of her hair.

"Now, now. It isn't as bad as all that," he said. He put his hand comfortingly over hers. He was surprised when he realized her hand was trembling.

"Why, darling," he cried. "What on earth's wrong? You're all upset. You're actually trembling!"

She stood up abruptly.

"I—I'm just on edge. I don't feel well. This horribly gloomy weather— it's given my nerves a raw edge, brought on a splitting headache. I'll be all right tomorrow. I'm sorry if I sound nasty, darling. I'll snap out of it. I'm going upstairs now and try to get some sleep."

He started, solicitously, after her.

"Please, I'll be all right. Just let me alone. Don't bother to come up now; sit around and read, why don't you? Please, darling, I'm all right."

He stood there bewilderedly, watching her ascend the stairs to their room.

"Very well," he said, "but if there's anything I can do—"

"Good night, dear. I promise I won't be so churlish in the morning."

He watched her step from view on the landing, then heard the bedroom door close behind her. He sighed, ran a thin hand through his lank black hair, walked over to his armchair.

He lighted a cigarette, turned on the radio, and picked up the half-read novel he'd left beside his chair.

The radio suddenly blared into sharp, startlingly noisy life. With a start, he turned toward it, intending to tune it down as quickly as he could. A news announcer's voice blasted the room in two words that had the effect of freezing his gesture before he could touch the tuning dial.

"Obviously murder!"

And then he heard the announcer's voice continuing:

"Leonard's body was found in a clump of bushes near Harkness Lane and Petersen Road. Two bullets had been pumped into his head, two into his chest. There was no evidence of struggle, which leads police to assume that the mail carrier was ambushed, or slain openly by someone with whom he was well acquainted and from whom he expected no violence."

It was then that he remembered the thunderous blatting of the voice, and he hastily turned the radio to a scarcely audible key. The news announcer's voice was concluding the bulletin.

"Sheriff Wilde has said that every aspect of the brutal killing is under investigation, and that he is co-operating with State Police who have taken over this, the first such crime in the history of the village."

DANCE music came in, then, and he sat there stunned,

trying to comprehend the implications of the news bulletin he'd

just heard. Leonard was the name of the rural mail carrier in the

village. Wilde was the village deputy sheriff. The lonely sector

where Harkness Lane joined Petersen Road was a scant three miles

from this house.

He realized now, that violent murder had entered the little community to which he'd taken his bride. A rural mailman had been shot down brutally less than three miles from their comfortable little house.

As he sat there, filled with the shock of it, he heard a sudden, sharp squeaking on the staircase landing.

His head swiveled sharply in the direction of the sound. He strained his eyes, trying to penetrate the darkness that blanketed the upstairs landing.

"Darling!" he called sharply. "Is that you?"

There was no answer, merely a tense silence in which he fancied he heard someone breathing.

He rose from his chair. The landing creaked again, and he heard the faint noise of a door—the door of their bedroom—being closed stealthily.

He stood there beside his chair uncertainly, his brow furrowed in bewilderment and anxiety. Had he only imagined hearing someone on the landing? Had his battered nerves deluded him into thinking he'd heard the bedroom door close?

He ran a trembling hand across his face. Perspiration beaded his forehead and his fingers shook ever so slightly as he groped in his pocket for his handkerchief.

"It's my damned illness," he muttered." Every attack leaves me more unsettled. It pulls my nerves as taut as piano wires, it makes my imagination play tricks on me, it upsets my balance, my judgment."

He put his handkerchief away, found a cigarette and lighted it shakily.

"I'll not put it off any longer," he told himself. "I've got to see a doctor before my health cracks completely."

He sat down, sighing tremulously. "Tomorrow," he promised himself, "tomorrow I'll have a thorough physical check-up. This damned malady has gone on too long."

He sighed, crushing out his cigarette. He needed rest. He might as well get upstairs and try to capture the luxury of sleep.....

BUT sleep, in the hours that followed, provided little

comfort, scant luxury. He was shaken, several times by hideous

nightmares which woke him, cold with sweat and wide-eyed in

horror. Each time, though the context of those horrible dreams

was lost to him on waking, he found his heart pounding

suffocatingly and his hands trembling badly.

But each time he was able to return to a stupor of coma through the realization of the comforting presence of his wife sleeping soundly, dreamlessly, beside him.

There was something akin to nightmare, however, which occurred during his coma, that was left to him as a half-real, half-figmentary, recollection. At one time it seemed to him, as he half opened his eyes, someone was standing over the bed, staring down at him. This someone was breathing with faint, regular cadence, and was dressed in flowing white. He recalled thinking that it was his wife, and remembered calling out her name questioningly.

But there had been no answer. The person, or thing, stared at him an instant longer, and was suddenly gone from sight.

Morning came in the same gray, rainswept fashion as it had the previous day, and when he woke he found his wife had already risen. He could hear her moving about in the kitchen downstairs. He glanced at his watch, then, unbelievingly, at the clock on the dresser. It was almost noon.

She had let him oversleep. He wondered if she had suspected the fatigue left on him by his attack of the previous day.

He sat up in bed and lighted a cigarette. It tasted bad but he let it hang there loosely in the corner of his mouth, savoring the smell of the tobacco that drifted to his nostrils.

He ran his hands through his lank black hair, trying to drive the cobwebs from his mind. Things began to take shape, and he recalled the scene of the previous evening, his wife's strange mood of irritation and pique. Then he recalled the news broadcast concerning the horrible murder.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, he found his robe, slid his bare feet into slippers—and then did an unaccountable thing. He rose from the edge of the bed, moving swiftly, stealthily, to the closet. There he paused a moment, listening.

Reassured by the sounds continuing downstairs in the kitchen, he opened the closet door gently.

There in the right hand corner of the closet was the suitcase in which he'd discovered the pistol with the pearl handle. The pistol about which she had not yet felt free to tell him.

He pulled the case out of the corner, opened it with swift noiselessness. As far as his swift appraisal could determine, the contents of the case were exactly the same as they'd been when he'd opened it almost a week before. Obviously she hadn't found it necessary to unpack the bag as yet.

The contents were the same. That is—with one exception.

The pearl-handled revolver was not there.

HASTILY, almost clumsily, he rummaged through the case.

But his exploring fingers found no evidence of the gun. He

examined the side compartments of the bag, where the box of

cartridges had been kept, but it, too, was no longer on hand.

Suddenly he straightened up. She had just called his name, sharply, her voice carrying clearly from the kitchen downstairs.

"Finally awake and stirring, darling?" she cried.

He felt a swift rush of guilt and embarrassment. Quickly he snapped the suitcase shut, pushed it back where he'd found it. He stepped out of the closet, called an answer.

"Be down in a few moments, dear."

But as he dressed, he could not wash from his mind the guilty feeling that had flooded his conscience. He felt as if, somehow, his actions had been a flagrant breach of faith, of trust in his wife. What had been the irrational motivating factor that made him act as he had, he could not imagine.

But suddenly, as he stood before the mirror, knotting his tie, the answer came to him with horrifying clarity.

"No!" he whispered. "No! I couldn't have been thinking that. It's, it's ridiculous. It's outrageous!"

But he stood there motionless, staring unseeingly at his reflection in the mirror. Then he shook his head quickly, viciously, as if trying to clear it of loathsome cobwebs.

He found himself trembling so badly he was unable to manage the careful Windsor knot he was tying in his cravat. An unaccountable nausea gripped him, and he realized that his complexion, reflected in the mirror, was ghastly white.

"This illness," he whispered. "This damned illness is warping my mind, giving me hallucinations, driving me mentally blind!"

It was fully five minutes before he was able to regain some semblance of composure, and another ten before he was able to complete dressing.

By the time he started downstairs, however, he was reasonably certain that nothing in his appearance would betray his mental and physical turmoil to his wife.

She was wearing a silly, frilly little apron, and she was smiling at him.

"Everything's ready, sleepyhead. Another five minutes and your toast would be cold."

He smiled wanly in response.

"Guess I stayed up too late. Rather gone this morning."

He saw that she'd set the breakfast table for the two of them, even to placing the rolled morning newspaper by his plate. He sat down with a sigh, reaching for the paper.

His gasp, when he unfolded it, was involuntary, but audible.

"What's wrong?" she demanded instantly.

He was staring at the big black type which screamed forth the headlines.

"The murder," he said tonelessly. "The paper is full of the damned murder."

She was beside him in a second, reading the headlines inaudibly, her lips moving slowly with the words.

He tried to hide his trembling hands in his lap. But she was paying scant attention to him.

"It's, it's horrible!" she gasped. "How on earth, in this peaceful little village, such a thing could happen—"

He looked up at her.

"Didn't you know?"

She seemed startled.

"What do you mean?"

"Didn't you hear it over the radio last night, right after you went upstairs?"

She gave him a look that was unfathomable.

"Why, no. Of course I didn't. How could I? I was upstairs? You mean this came over the radio last night?"

He stared at her bewilderedly.

"Yes. But I thought I heard you. It was very loud. I didn't tune it down for a few moments. I thought I heard you on the landing, listening."

"I? Why, how silly. Of course not."

"I, I called out," he said lamely, "asking if it was you. There was no answer."

"How could there be?" she demanded. "I wasn't on the landing."

HE wanted to drop the matter, now. It seemed dreadfully

urgent that he drop it. It was getting him nowhere. He was

sounding like an idiot, babbling. His head was beginning to ache.

He wanted to get off the subject immediately.

He had only horror, however, at the subject he found himself involuntarily choosing for the change. He couldn't possibly imagine what prompted his lips to utter the question that now popped from them.

"Why didn't you ever mention, darling, that you own a revolver?"

Her expression froze instantly.

"What did you say?" she asked slowly, coldly.

Miserably, in spite of his every desire to say anything else, he found himself repeating the question.

She was staring at him now with a cold, distant fury.

"You've been snooping," she said quietly.

"No, dear, I—I was just unpacking your things and—"

Her voice, like a whiplash, cut him off.

"Spying on me! Sneaking about, peeking into my things!"

He tried to form words of protest, but they tumbled over one another before they reached voice. His temples pounded, and he felt a sickening dizziness obscuring his thought processes.

She had left the kitchen suddenly. And before he could rise, she was back again. Her coat was thrown over her shoulders.

"I'm going for a drive," she snapped. "A long one."

He stood up, her name escaping his lips in a groan of protest.

She paused, the whiteness of her cheeks regaining some color. Suddenly the anger seemed to wilt from her like starch.

"I—I'm sorry dearest. I didn't mean what I said. I—I've an ungovernable temper at times. I suppose it's one of the things you don't know about me. I sometimes fly completely off the handle."

She had stepped forward now, close to him. Her perfume was strong in his nostrils. She stroked his cheek softly with her cool, slim hand.

"I'm sorry, darling," she said humbly. "But I do think I need some fresh air. A drive would do me good. Where are the keys to the car?"

"In the summer house," he said. "In the drawer of my wood sculpture bench. You—you won't be long?"

She shook her head.

"No, I won't be long. I'll hurry back. But I just have to get some air. I have to calm down. I've been so snarled up, so depressed these last few days. I ought to be horsewhipped for treating you as I did. I promise I'll reform, darling."

He watched her leave, wordlessly. The screen door was open and he saw her cross the garden, gingerly picking her way through the mud, toward the summer house.

His lips were trembling. His hands shook so badly he was unable to light the cigarette he found until a half a dozen matches had been wasted.

He turned, went back to the living room. A few moments later he heard the sound of the motor starting in the driveway. He waited, smoking, until the sound was gone in the distance. Then he rose and went into the kitchen.

For several minutes he stared down at the headlines in the paper still spread on the breakfast table.

He felt weak, exhausted, feverish. And then the pounding in his temples returned. The dizziness, the gray-spotted blackness, the lack of equilibrium —all were closing in on him.

He opened his mouth, but his tongue was as cotton and his lips soaked wool.

"She—she didn't explain," he heard a voice croaking thickly. "She—she didn't say what—"

And as the voice trailed off he knew it was his own, forming words for which he had no conscious thoughts. He could see things only as a blur, now. The blackness was worse. His knees were buckling, his heart was seized by a breath-stopping constriction.

He tried to move forward, and realized, dimly, that he was falling headlong into a swirling vortex of thickening and overpowering blackness.....

IT was as gentle, this time, as waking unprompted from a

pleasant sleep. As gentle and as gradual and untroubled. For

fully three minutes he lay there, breathing easily, gathering

consciousness around him like a staff on whose support he was

going to rise. Then he opened his eyes. For an instant, his

reaction was surprise. Then he sat bolt upright, looking around

in bewilderment.

He was in the summer house, on the floor beside his workbench in his hobby shop. His clothes were damp, and it still rained outside. His shoes were muddied, and grass and bits of leaf still clung damply to them.

He rose, surprised at the strength in his limbs.

Aside from a certain almost giddy lightness, he felt normal enough. The hand he stretched to the table was meant to steady himself, rather than support him.

He knew, clearly and without having to unsnarl his thoughts, that he had been in the kitchen when the seizure had come. He could not remember having staggered outside — possibly with an instinctive pursuit of air—but he was perfectly aware that he certainly must have done so after the blackout. Instinct for shelter, no doubt, had carried him on increasingly wobbly legs, to the summer house.

That was the only way it could have been. He must have collapsed inside the summer house once he'd reached its shelter.

He looked at his watch. Almost four hours had elapsed.

He sat down slowly in the chair beside his workbench. Perplexity was written on his face, confusion in his eyes. He was trying to explain to himself the reasons for this totally unexpected and unusual aftermath to the seizure he'd suffered. It had always been definitely the opposite, after one of his attacks. Always, he'd been left sick and shaken.

Now it was decidedly different. He held his right hand, fingers spread, before him. There was no trembling.

He wondered what this meant. Subconsciously, he knew, there was the faint, glimmering hope that perhaps this new reaction to his old malady was an indication for the best. If he were now being left with practically no after effects from his seizure, might it not be possible that he was growing somewhat better?

He pushed this hope back into the corner of his subconscious from which it had risen. He dared not build too much on it, dared not cherish it too strongly. He must wait and see.

Finding a cigarette in his pocket he lighted it, rose from his chair, and left the summer house.

He was crossing the garden when he saw the car parked in the driveway, and realized that she had returned from her drive. He wondered, fleetingly, how long she's been back. He felt slightly hurt to think that—had she been home for a while—she hadn't wondered at his absence and looked for him in the summer house. Then he realized, with relief, how fortunate he'd been that she hadn't gone in search of him. She might have found him stretched on the floor. That would have resulted in her first realization of the spells he suffered. She knew nothing about them, and he did not want her to know—now of all times.

He was at the steps to the back porch when he saw her handkerchief. It was lying in the mud by the first step, slightly hidden beneath it. He picked it up, shaking the mud and water from it instinctively as he did so.

It was then that he realized something was wrong. The handkerchief was sticky—and its dampness was not all from water.

His heart stopped beating for an eternal second as he stared at the wisp of cloth. It was covered with sticky blood.

HIS first reaction was one of frightened alarm. She was

hurt! She had injured herself. Perhaps, at this moment, she was

lying helplessly somewhere in the house, unconscious from a wound

of some sort!

He stuffed the handkerchief into his pocket and dashed up the steps and into the house.

In the kitchen he called her name, loudly.

There was no answer, and he called again as he rushed into the living room. There was still no answer. His heart hammered wildly as he ran upstairs to the second floor.

He saw her the moment he opened the bedroom door. She was lying on the bed, still wearing the sports frock she had on when she had left the house that morning.

One hand was thrown back beside her gorgeous raven curls, and her eyes were closed in sleep. There was a faint, half-smile on her lips. She breathed evenly, naturally.

There was nothing wrong. Nothing at all.

He began to tremble as the wonderful surge of relief shook him. She was safe. There was nothing wrong. She was sleeping as peacefully as a child.

He stepped out into the hallway, closing the bedroom door softly behind him, not wishing to wake her, grateful that his first cries had not roused or alarmed her.

Quietly, he made his way downstairs.

He went into the kitchen, thinking to mix himself a drink.

He saw the paper parcels of groceries she had purchased, then, lying where she left them on the sink.

He began to remove the contents from the paper bags, placing them in icebox and cupboards. He had almost finished this, when a sudden, starkly frightening thought seized him.

The handkerchief!

She was unharmed, sleeping peacefully. She had not, in any way, injured herself.

Then what could explain the blood on the handkerchief?

Quickly, he took the handkerchief from his pocket. It was the same, of course, sticky with blood, muddy, moist from rain. And it was her handkerchief—there was absolutely no doubt of that.

He tore a section of paper dish towel from the roll over the sink, and wrapped the repulsive wisp of linen in it. Then he returned it to his pocket.

He stood there a moment, leaning against the sink, fighting back the wave of nausea and the formless clouds of nameless terror that closed in on him.

With a supreme effort of will, he forced the matter from his mind. Robot-like, he resumed his removal of the groceries from the packages.

At the bottom of the last bag was the package of strychnine.

He started to put it on the cupboard shelf automatically, then he saw the legend: "POISON!" stamped in red across the box.

He paused, holding the box in his hands, staring at it, fascinated by the grim skull and cross bones that accompanied the warning word.

IT was then that she spoke, from the door directly behind

him. He hadn't heard her descending the stairway, hadn't heard

her quiet entrance to the kitchen. The sound of her voice

unnerved him so utterly, that the box dropped from his hand and

crashed to the floor.

"Hello, darling," she had said softly.

And as the box fell from his hands, she'd added, "Goodness, I didn't mean to startle you!"

He wheeled to face her. For a moment, while he stared at her, he could think of nothing to say.

"What on earth is wrong?" she asked.

Then he managed to say, "Nothing. Nothing at all, dear. You startled me terribly. I—I guess my nerves are a little raw."

She came to him, smiling, tenderly, slipping her arms around him, looking up into his face as she said:

"I'm sorry I was such a nasty little beast this morning."

Moments later, he asked:

"What did you get this strychnine for, dear?"

Her eyes were wide in surprise.

"Didn't I tell you? I thought I did. There are mice in the cellar, darling. The grocer said this was just the thing to get rid of them with."

He didn't mention the handkerchief, then or later. He could not bring himself to do so, no matter how desperately he wanted to. In the remainder of the afternoon, while he pretended to read in his chair by the radio, and she curled up, cat-like, on the couch, he fought down the thousand and one doubts and fears that assailed him.

By dinner time, they had almost regained a normalcy in their quiet pattern of existence. She chatted naturally about her trip to town, her visit to the grocers, inquired as to whether or not he'd been able to get in any work on his book; and he was able to answer her questions and supply comments of his own, in a manner that was externally, at least, reasonably natural.

Each of them carefully avoided any topic which might have led to any disturbance of the even keel of their reborn conviviality. And the tenor of their relations might have remained on that key, had it not been for the intrusion of the radio news bulletin several hours later.

WHEN it happened, she was reading, and he was sitting in

his chair by the radio, pencil and writing board before him,

sketching in several difficult character motivations that had

been bogging the plot of his novel.

A "canned" recording program of symphonic music had been on, providing a pleasant background for the evening, when the program was abruptly interrupted.

"Station KJMA interrupts this program to bring you a special news bulletin," an announcer's voice broke in.

Then another voice came excitedly over the air, reading the flash news announcement:

"The little village of Westport was again visited by brutal murder, today, with the discovery, late this afternoon, of the body of Abner Crassons, a watchman employed at the Westport Stone Quarry, Bay Road and Portage Street.

"Crassons, longtime resident of Westport, was found in his watch shack at the quarry, by the night watchman who came to relieve him at four-thirty this afternoon, lying on the floor of the shack, dead as the result of a dozen vicious stab- punctures around his head and chest. The death wounds were inflicted by what is believed to have been a sharp, knife-like instrument closely resembling a file or chisel.

"The discovery of this hideous slaying marks the second mystery murder to occur within twenty-four hours in Westport. The slaying, yesterday, of mailman Levrett Leonard, was the first such singular crime to strike within the precincts of Westport in all the history of this—"

HE was on his feet, by then, staring in horror at the radio as

if it were some living voice which was dragging the gruesome

tragedy into the inviolate sanctum of their living room.

Quickly he reached for the dial, snapping off the radio.

The sudden silence that followed the throttling of the radio was electric in its tension.

"Bay Road and Portage Street," he said huskily. "That's within a mile of here. The first murder occurred less than three miles from here. It's horrible!"

She was sitting up on the couch now, her eyes wide, mirroring the fear that was in his heart.

"Two of them—two within twenty-four hours!" she said. Her voice was tight, oddly containing no fright, however.

She rose, moved over to him, put her arms about his trembling shoulders.

"Now, darling," she said softly, "I know it's dreadful. But don't let it alarm you so."

He looked into her dark eyes then, and realized that what he'd thought to be fear there was not that emotion at all. It was something else, something strangely akin yet vastly separated from fear. An emotion which he found himself helpless to classify.

Something within him gave way at that moment. He found himself suddenly shaken by sobs, and cursed himself for his helplessness before her.

But her voice was liquid, soothing, reassuring, and there was comfort in her arms. He was scarcely aware of it as he babbled forth the confession of his illness, and when at last he had regained control of himself, he concluded:

"And that's what's been driving me desperately crazy, dear. The fear that I may have some dread malady that will fell me suddenly, without warning ˗ an illness that might take me from you forever in the flicker of an eyelash. I've fought against it, feared telling you in the dread that you might think I tied you unfairly to an invalid—but now, thank God, it's off my chest!"

SHE was a pillar of comfort to him, a steadfast emotional

rock behind which he could find shelter for the pain and turmoil

and doubt which assailed him. Her voice was like soothing balm,

and the words she spoke were as gentle and reassuring as the

psalms of a thousand angels.

"You poor, poor dear... don't worry any longer, dearest ... it will be all right... we'll have doctors... there'll be rest... you should have told me sooner ... it would never have made any difference to me...."

And then he felt the symptoms of another seizure closing down on him. There was the increased tempo of his heart which brought the familiar breathless constriction. The spotted gray clouds that whirled in on him were returning, and behind them the black curtains of night billowed ominously.

With every last atom of his being he fought against it, and for a moment that was an eternity, he was dizzyingly suspended between consciousness and submission to the attack.

He fought his way clear in a sudden, snapping, burst of will.

There was a faint dizziness, a ringing in his ears which followed a popping sensation much like a swimmer clearing his ears of water clots.

But he knew he had beaten it. He knew, with a vast, surging sense of triumph, that he had met the attack and thrown it back.

"Darling," he heard his wife saying, "Darling, you're shaking like a leaf!"

He was able to smile, then. Smile and shake his head, as he said:

"Everything is going to be all right; you're not wrong in saying that, dear. I'll beat it; together we'll beat it."

She smiled at him then.

"Certainly we will, darling, together." Then, "I think you ought to get a little rest now, don't you, dear? Just an hour or so. This has really been a strain, weathering all that worry alone."

He nodded. "A little nap, perhaps. Then we might play some gin by the fire, eh dear?"

She patted his shoulder tenderly.

"I'll wake you in time," she promised. "Now, try to get a little rest. You'll wash your worry from your mind, I'm sure, with that nap."

She stepped to the radio, turned it on, dialed in the soft syncopation of dance music.

"We won't think about the outside world, darling," she said. "There'll be just the two of us. We can ignore everything else, and after a little while you'll be well again. I know it."

He kissed her, and left her curled up in his chair by the radio, a book in her lap. He felt tired, and the ringing was still in his ears. But there was a sense of freedom, now, as he moved up the stairs to the bedroom. The weight of worry had been lifted in part from his mind, and the knowledge that she shared his burden was warmth and comfort.

It was only after he had entered the bedroom and closed the door behind him that his new found confidence began to slip slowly from his shoulders.

He had not switched on the light, and he stood there in the darkness the closed door walling him from any tangible evidence of the security her presence in the house had given him.

Cold perspiration broke out on his forehead, and the palms of his hands were suddenly icily damp.

It wasn't as easy as they had pretended it would be. He knew that now with a sickening clarity.

There was something else. Something unspoken. Something that had not been cleared from the ominous gray oppression that had been closing in on him. Something that had been burned unmistakably in the blackened recesses of his subconscious. Something he had ignored—something he had, through fright, deliberately walled off.

His fingers trembled as he stripped himself of his shirt.

HE sat down heavily on the edge of the bed, his head in

his hands. The ringing in his ears was stronger now, but

surprisingly not unpleasant.

He realized that he had not bothered to turn on the light, and knew in the same moment that the blackness welling in on him could not be dispelled by the glare of an electric bulb.

He rose from the bed and walked to the window. The rain outside had stopped. But the sky was still a mottled pattern of black and gray. The wind was high, and shook the trees beside the house with fierce gusts that slapped wet fragments of leaves against the window panes.

The black wave of depression that engulfed him was as sudden and inexplicable as his swift loss of confidence on entering the room.

He turned from the window and walked to the dresser, where he found cigarettes and a packet of matches. It was strange, he thought abstractedly, how well he was able to see in the darkness. Strange, too, how crystal clear his thinking processes had become.

Lighting a cigarette, he blinked momentarily at the flare of the match and was grateful for the return of darkness when the match sputtered out a moment later.

He moved to the bedroom door, opening it softly. Music from the radio came faintly to his ears. He wondered how softly he would be able to move.

He opened the door a little wider, pleased with the noiselessness with which it swung on its hinges.

The music was louder as he stepped from the bedroom and closed the door silently behind him. He waited there a moment, listening, peering down the darkened stairway at the patch of light which formed a square just outside the living room door.

Slowly, with infinite stealth, he moved down the stairs, pausing every several steps to listen for any sound which might indicate her movement in the living room.

But there were no sounds save those of the radio and the dance music, and he was able to complete his descent of the stairs unnoticed and slip unseen into the kitchen.

He was able to slip out the back door into the garden with equally successful stealth a moment later. Then he made his way quickly to the summer house.

Moments later, in the summer house, he was rummaging quickly through the drawer of his wood sculpturing work bench. As his hands moved swiftly over the familiar tools the cold perspiration on his forehead increased.

Finally he stopped, closing the drawer slowly.

The death wounds were inflicted by a sharp, knife-like instrument closely resembling a file or chisel.

The words that the radio news announcer had read came back to him with bell-like clarity.

An instrument such as the wood sculpturing knife that had been in his drawer. The wood sculpturing knife that he was now unable to find in the drawer.

He could hear her voice, asking the question she had put to him that very morning.

"A drive would do me good. Where are the keys to the car?"

And he could hear his own voice, answering her as it had:

"In the summer house. In the drawer of my work bench."

She had gotten the keys. She had rummaged through the drawer to get them. And the sculpturing knife was missing.

His hands trembled now, but not from fright. An almost breathless excitement possessed him, overwhelming the panic of his thoughts.

He left the summer house, but as he crossed the garden he moved slowly, his head bent forward as he scrutinized the ground.

At the back porch stairway he paused before the place where he had found her bloodstained handkerchief. He crouched low, peering at the ground around the porch.

Then he was on his knees, his hands groping along the muddy earth in the radius of the place where the handkerchief had been found.

MOMENTS later, back beneath the steps, almost buried in

the mud, he found the thin, chisel-like sculpturing knife. It had

been but a few yards from the handkerchief, but hidden from

view.

As he held the instrument close, peering at it in the darkness, he could feel a stickiness which he knew was not mud. And when he threw the knife back beneath the steps and looked at his hands, he saw the thin, gray, blood matted hairs that adhered to his fingers.

He rose, standing there in the darkness, fighting off the panic that swelled in his chest. His heart pounded with an intensity that left him breathless.

Calm. He knew that he must be calm. Panic was something he could not afford.

He moved up the steps soundlessly and slipped through the back door into the kitchen.

Music still came from the radio, and he stood there in the darkness of the kitchen holding his breath, listening intently. There was no sound to indicate that she had moved since he'd slipped from the house.

He moved cautiously through the kitchen, pausing in the darkened hallway just off the living room. Through a quarter inch aperture at the corner of the drapes that hung from the archway to the living room, he was able to see her.

She was still curled up in the chair by the radio. Curled up cozily, intent upon the book in her lap.

Cat-like.

The phrase rang in his mind. Cat-like. She looked exactly like that.

He moved away from the archway and to the staircase. He was able to ascend the stairs to the second floor landing as noiselessly as he had descended them scant minutes before.

He felt a weak, trembling wave of relief when he was at last again in the bedroom, the door closed behind him.

Standing there in the darkness he waited until he was able to breathe more normally and to control the trembling in his body. Then he crossed to the bed and sat down.

It was incredible to him that his mind was working with such knife-like keenness. Everything seemed etched with a sharp clarity that was almost frightening in the pattern it produced.

The gun. She had never explained it, even after it disappeared. Her past. What did he know of that? Nothing. She had said as much, but had volunteered nothing further. The handkerchief. The sculpturing knife.

And it suddenly came to him that he had given her a terrible weapon in his confession of his helpless illness.

The thought was enough to start the tremors in his hands again, so uncontrollably that he was forced to grip them between his knees to keep from becoming completely unnerved.

Panic filled him and he fought desperately against it, knowing that he dared not let it best him.

IT was then that he heard the footsteps on the stairs. Her

tread was light, soft, and for a moment he listened like a man

hypnotized, counting the steps.

Suddenly he swung his legs onto the bed, rolled over and buried his head in the softness of a pillow.

She was coming to the bedroom, and he dared not let her realize that he hadn't been sleeping all this time. He tried to force his breathing into a regular pattern. She mustn't become suspicious.

The footsteps stopped outside the door.

For a breathless eternity he waited. Then he heard the knob turn gently, felt, rather than saw, the inward opening of the door.

He could feel her presence there in the doorway, though he did not look up. With every effort of his will he forced himself to maintain the pretense of the deep, regular breathing of one in sleep.

She was standing there in the doorway, looking into the darkened room at him, he knew. Cat-like. How well could she see through the darkness?

Then the door was closing again, gently, and at last he heard her footsteps descending the stairs.

He moved over to the edge of the bed, swinging himself up to a sitting position on the edge of it again.

The trembling in his hands had ceased, and he felt a calm that was as startling as it was sudden. He knew now what he had to do. He had to brazen it through. He had to let her have no inkling of what he suspected—until he confronted her with the truth.

He stood up, found another cigarette on the dresser, lighted it, his mind working swiftly, coolly.

He found himself marvelling at the keenness with which his mind was functioning. The calculating cunning with which he was able to plan his moves was wonderfully reassuring, and gave him a courage that was vitally necessary if he were to carry them through.

There was a telephone extension in the hallway just outside the bedroom, but he realized it would be idiotic of him to think of using it. Later would be time enough to call. Now would mean too much risk. She could listen in from the telephone downstairs.

He found his shirt, donned it carefully.

Then he stepped to the door. He could hear her moving around in the kitchen downstairs, then, and the sound of her movements was louder as he opened the door and stepped out onto the landing.

He had been careful to make a natural amount of noise in leaving the bedroom. And, as he had expected, she heard him.

"Are you up already, dear?" she called.

He answered her briefly, satisfied in the realization that he was playing the role of normalcy perfectly.

"I was fixing a snack for us, darling," she called as he started down the stairs. "I wasn't going to wake you until I had it ready."

He could smell the coffee percolating, and bacon frying.

She was busy at the stove when he entered the kitchen, and turned to smile at him.

"A few sandwiches ought to go well," she said. "Did you get any rest?"

"Plenty," he said. "I think I've got everything straightened out pretty well, now."

"That's grand. If you want to help, you can slice the bread for the sandwiches."

He glanced at the table, where she'd set out cups and saucers and plates.

"Glad to help," he said. He stepped to the cupboard.

And then he saw the strychnine. The same box she'd purchased that afternoon. The same box that he had dropped, then put away. Only it wasn't where he'd put it. It had been moved, and it was opened. The corner of the top was torn.

She was talking, saying something conversationally trivial, but he paid no attention to her. His gaze was frozen to the box.

She must have said something that required an answer, for she had turned from the stove and was staring at him sharply, saying:

"What on earth is wrong?"

HE wet his lips remembering that he had to remain

calm.

"Nothing," he said, forcing a laugh. "That's no place to leave poison. I stuffed it way back into the cupboard this afternoon."

Her answer was easy, almost glib.

"You stuffed it into a corner, and it almost beaned me when I opened the cupboard. It fell out missing me by a fraction. It broke open on the floor."

She laughed easily. "It won't hurt anyone there."

"No," he said slowly. "No. I suppose it won't."

"The bacon's almost ready. You'd better slice the bread."

He nodded. He took the long, sharp bread knife from the drawer, found the loaf on the shelf.

He was rummaging for the breadboard when he said:

"There are several things I'd like to ask you about, if you don't mind."

The expression on her face was almost bland as she said:

"What on earth? What's troubling you, dear?"

He straightened up, forgetting the breadboard, ignoring the loaf, the feeling of the long, sharp knife in his hand giving him confidence.

Now was the time. There was no sense in playing it out any further. It had to be now.

"You never told me anything about yourself," he said quietly. "I never knew where you came from, who you really were, anything about your background."

The expression on her face was no longer bland.

"What do you mean?" she asked quietly.

"You never did tell me why you carried that gun, my dear," he declared. He was watching her eyes, now. Watching her eyes and thinking how very much like the almond eyes of a cat they were.

"You accepted me without an explanation of my past," she said slowly. "Why are you suddenly so curious about it?"

Carefully, speaking each word slowly, he let her know that he knew.

"It has recently become a matter of life and death—and murder," he said.

Her sharp gasp, the sudden freezing of her expression, told him that he had scored. Now she knew that he was on to her. Now was the time for him to play through the rest of his cards quickly, decisively. There could be no faltering now.

"Murder," he repeated. "Murder with a gun, murder with a—"

And then the seizure swept over him. Swiftly, without warning. The stifling constriction that choked off his breath, his words. The dizziness, the trembling, every dreadfully familiar symptom of his malady.

His lips moved, but he knew he wasn't making sounds.

Panic surged through him, pounding sickening fear wildly through his veins, to his temples, to his brain. Now, now when he had played his hand, when he had revealed his knowledge to her— now he was being stricken helpless!

BUT an instant later he knew there was something subtly

different. There was no blackness—this time— pouring

in to blot out consciousness.

Everything about this seizure was the same as the others had been—save for that fact, and the fact that the weakness was swiftly leaving him and that his brain was functioning with incredible clarity. The familiar swimming of objects before his eyes was leaving, and things were coming into focus again.

He felt a strange exhilaration, and the ringing in his ears was an exultant clamor. A door, deep in the darkened recesses of his mind, was slowly opening, and quite suddenly he was able to see beyond the black veil that had shuttered his actions in unconsciousness during all his previous seizures.

Now he was staring at the girl before him, seeing her beyond the shining glitter of the knife he held in his hand. Her eyes were wide with sudden fright, and her moist, lovely lips were half-parted in horror.

"You!" she whispered hoarsely. "You!"

The word writhed and danced around his ears, and he realized that she, too, had glimpsed what was behind that tiny door far back in the darkness of his brain.

"You killed them!" she gasped.

Light flickered and danced from the blade of the knife in his hand. He laughed, and the sound jerked from his lips like a cough. She was clever. How did she know? She was peering through the tiny door, that's what she was doing. But it was clever of her. And she was right. So very right. Why hadn't he realized until now? Of course he had killed them. During that one seizure he had stolen the tiny gun of hers, and the cartridges. He could see it, through the little door. It was so clear, so crystal clear.

He began to move slowly toward her. He didn't want to startle her. She was clever and she might guess at what he had to do.

Her lips were moving, making words. But he couldn't hear them. Through the little door he could see his actions after the last seizure. He had made his way to the summer house, gotten the sculpturing knife. When he had returned from his walk he had hidden the knife under the steps, and found her handkerchief where she'd dropped it. He'd wiped his hands clean with her handkerchief, then dropped it by the steps. He hadn't remembered any of it when he'd regained consciousness in the summer house. But now he remembered. It had been clever of him to use her handkerchief. Just as he had been clever in stealing her gun.

She was backing away from him, now, and her lips were still moving soundlessly.

The knife in his hand was light, so exquisitely balanced. He felt pleased about the knife. It was so clever of him to have it on hand, actually in hand, when he needed it.

As he closed in on her his eyes sought the white contours of her throat. A soft white throat. Lovely.

She was backed against the wall now. She couldn't move any further. It was all so clear, so perfectly clear. And he knew what he had to do. He had to keep that throat from screaming....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.