RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

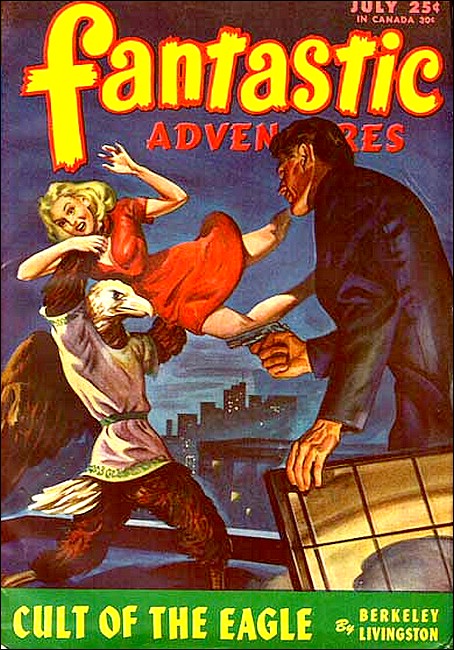

Fantastic Adventures, July 1946, with "The Softly Silken Wallet"

... thrust the banknote over his shoulder.

The wallet was soft and silky, but there was

something very horrible about it, like death....

THE thin, sharp-featured little man standing at the rear of the Elevated platform in the swirling snow that chilling March afternoon, was pleased. His pleasure was evident in the smirk on his thin lips and the glitter in his gimlet eyes as they moved restlessly, appraisingly over the crowds that jammed the station.

Marty Merkin was thinking that, despite the cold and the snow and the crushing jam of passengers waiting on the platform for trains, this was a hell of a good day for business.

On a day like this, he reflected, people were conscious only of their own weariness, discomfort and the immediate problem of forcing their ways through the Elevated doors to find seats for the homeward trip.

On days like this, consequently, sharp-eyed pickpockets like little Marty Merkin were in clover.

An Evanston Special rolled up to a stop, and Marty grinned as he watched the people on the platform surge forward, fighting each other to be first inside the opening doors.

But he didn't move forward to mingle with them and press closely against them. Instead he stood there watching and smiling and taking his time. There was plenty of time, just like there was plenty of fish, he told himself. It was just a matter of standing back and casing the crowd until a really ripe customer happened along.

That big fat guy, Merkin observed, arms full of bundles, was well-dressed and obviously in the chips. Yet Marty's long practiced analysis told him unfailingly that the fat guy wouldn't be the sort to carry his dough around in big wads. There'd be maybe ten, maybe fifteen, in the fat guy's wallet. Not enough to bother with on a day like this.

"Day like this," Marty told himself, "I don't settle fer no small stuff."

So he continued to watch the crowd, smirking happily at the prospects he knew to be ahead, taking his time and watching for the right one.

The right one came along less than ten minutes later. He was a tall guy and thin as a beanpole. Marty watched him come out onto the platform, noting that he had musician-length gray hair that came almost to the collar of his thin gabardine topcoat. This right one was middle-aged, Marty saw, with a long, lean, horse-like face and deep, sunken gray eyes.

He was carrying a large instrument-case, which Marty judged to contain a cello or some stringed instrument similar in size and shape. That was, of course, the absolute confirmation of Marty's judgment that the guy was a musician.

The thin, beanpole-ish guy stood there on the platform, the wind and swirling snow flapping his topcoat grotesquely against his thin shanks and gaunt frame.

Marty couldn't restrain a grin, as a gust of wind caught the man from the rear and outlined, momentarily, the bulky block of a wallet in his right hip pocket.

That was double confirmation for Marty. Confirmation that these musician guys were the type to carry most of their wad with them, and to be very careless about it. He wet his thin lips in anticipation, and moved forward until he was less than four feet behind the musician.

A RAVENSWOOD Express rolled into the station at that moment, and the tall, gaunt, horse-faced musician began to move forward to push with the crowds toward the door.

Marty stepped up directly behind the fellow, pressing hard against him, as if he too were trying to push for a seat on the Ravenswood Express. Several other passengers pushed in behind Marty, which increased the surging pressure and pleased Marty additionally.

The beanpole-ish musician was having a time of it with his big cello case. He had to hang onto it with both hands, and turn it from side to side to keep the crowds from damaging it. This was an additional boon to Marty, though he scarcely needed it.

It was really almost too simple to take. Marty felt what almost amounted to a twinge of guilt as he flipped open the razor sharp blade of his pocket knife.

In the half dozen steps remaining to the door of the elevated train, Marty expertly slit through the topcoat, slipped his hand inside the rent, and removed the fat wallet from the musician's hip pocket.

In half a minute more, Marty had eased out through the crowds until he was on the back of the platform. He slipped the wallet into his own pocket and hid the knife in his sleeve in these brief seconds. And now he turned to glance at the train door, where the big scarecrow with the cello case was just moving through the door.

He was the last one on the car as the doors slid shut. And Marty saw the sudden, startled expression on the gaunt guy's face as he turned to face the window. The scarecrow had taken one hand from his cello, and was groping with the other at the rent in the back of his topcoat.

Marty saw all this in a glance, and smirked as the train began to roll.

The last glimpse he had of the musician guy was his expression of surprise and stricken dismay as he became aware of his loss.

Marty moved nimbly through the crowd to the regular exit, lost himself in the comforting numbers, and was down on Wabash Avenue a few moments later.

He walked briskly along for several blocks, moving south toward the section of cheap bars and restaurants, flophouses and salvation missions that comprised the district on that border of the Loop.

After three blocks he stopped casually before the large plate window of an antique shop. He looked easily to his left, the direction from which any possible pursuit might come. He knew he had cleared himself neatly, but habit made him careful. As he had figured, there was no pursuit.

He snapped the razor-keen pocket knife shut, dropped it from his sleeve into his pocket. Then, putting his other hand into the pocket of his overcoat, he felt the fat, promising bulk of the smooth leather wallet.

He had to laugh. It had been a breeze.

MARTY moved on, then turned a corner after several blocks more and abruptly entered a small, beer-reeking tavern with dirty windows and dirtier customers inside.

He nodded casually to several of his acquaintances as he moved along the bar. Then he found an untenanted booth in the rear, and sat down to see what his profits were.

He made no secretive pretense about examining the wallet after he had placed it on the table before him. Such hypocrisy was quite unnecessary in this particular den of thieves.

A barkeep came up to the table, just as Marty was opening the wallet.

"What'll it be, kid?" he demanded, his oily eyes flashing to the wallet in Marty's hands.

"Wait'll I see," Marty smirked. He glanced inside the wallet. He whistled appreciatively. "Make it Scotch. The real. Double. I drink like a gent after this kinda haul," he said.

The barkeep grinned, exposing yellowed crags of broken enamel. His oily eyes flicked again to the wallet, and then he moved off without any further comment.

Before the barkeep returned with the drink, Marty tabulated the results of the day's work. Two hundred bucks. In tens and twenties. Plus, of course, some chicken feed of three wrinkled singles. The other bills, being fresh and crisp, Marty suspected of having come recently from a pay envelope.

Marty removed the cards and identification from the wallet, not bothering to read any of them. It was a matter of complete indifference to him who or what his victims happened to be.

He tore the cards across several times, dropped them into the spittoon. He was about to look about for a disposal place for the billfold when he suddenly changed his mind.

It was a damned nice wallet, smooth and slick to the touch. Marty was an expert on wallets. He'd seen plenty of them, and knew that this one was considerably better than run-of-the-mill. He shrugged, glanced again at it, and put it in his pocket.

Hell, maybe he could sell it to some stiff at a bar.

The barkeep came back with the Scotch.

"Stand 'em up for the house, once't," Marty said expansively. "This is gonna be my night fer a little celebrating."

The barkeep grinned.

"Even better than yuh thought, huh, Marty?"

Marty shrugged his shoulders non-committally, but his leer was proudly boastful.

"Oh, I dunno," he said....

WHEN Marty Merkin woke, the following morning, the elevated trains jarring past the window of his dingy room almost tore his head off with their racket.

He was conscious of an extremely thick tongue, a faint nausea in the pit of his stomach, and the fact that he had a grandfather of hangovers.

He sat up in bed, his skinny fingers digging deep into his balding scalp as he tried to massage himself into complete wakefulness.

It was then that he noticed the hairpin on the pillow beside his own—and the faint reek of cheap perfume that hung heavily in the room.

He looked quickly around, saw that he was alone, cursed, and climbed shivering from his bed. The lipstick wounds on the tips of the crushed cigarettes in the dresser atop the ash-tray were further evidence that he had not been alone earlier that morning.

He squinted, trying to remember where he'd been, what he'd done. But it was tough sledding. There were plenty of parts in the evening, particularly the latter ones, that he drew blanks on. He could recall buying drinks for the house in a number of joints, of singing and boasting, and ordering more, and of laughing, red-mouthed girls who clung to his neck.

Suddenly he thought of the wallet, his own wallet, in which he had carried the profits of his day.

He cursed and lurched for the dresser. It was not there.

He found his pants, still cursing, turned them upside down and shook them. Some change, matches, a key fell from them. But no wallet. His coat proved to be equally barren.

"Damn her, that little—" Marty cursed his anonymous visitor.

He felt suddenly considerably more sick than he had on rising. The thought that everything but a few pennies had gone, was hard to bear.

And then, in a corner of the room, he saw the slick, expensive wallet which he had heisted the afternoon before. The sight of it was not pleasant. It reminded Marty that he had had two hundred bucks less than twenty-four hours ago. Two hundred bucks which he didn't have now.

"The dirty little so-and-so," Marty snarled. "The cheap little—"

HIS sentence died abruptly. There was something about the wallet lying in the corner of the room that was peculiar. Something plump and sleek and inviting.

Instinct prompted Marty to go over to the wallet and pick it up. Instinct told him, the moment he touched it, that something was screwy as hell-but wonderfully screwy.

He flipped it open quickly, gasping involuntarily as the contents were revealed. Bills, a number of them! Bills of big denominations!

Marty's hands shook as he held the wallet and flip-counted the money inside it.

There was almost three hundred bucks there!

He stared hard at the money, gimlet eyes almost popping. It was all old dough, greasy and wrinkled and well-used. Obviously unlike the crisp two hundred he'd had a little while back. But, just as obviously, real dough.

He was suddenly shaken by laughter, wild, relieved laughter that choked him finally and started him coughing hackingly.

He went back to his bed and sat down on the edge, coughing and laughing and holding the plump, money-stuffed wallet in his hands.

This was a scream, this was a riot. It was funny as hell. As drunk as he'd been, as cockeyed, roaring tight, he'd carried on his business with his pleasure and managed to filch another billfold, netting a haul even greater than the one from the musician.

It occurred to Marty that he'd been a smart operator indeed to place the take from this unremembered heist in the wallet he had filched from the musician guy. When the dame had gone through his own wallet, she'd probably taken every cent and been too dumb to look for this second wallet.

Marty frowned. He must have tossed away the wallet in which he'd swiped this last haul. Probably it hadn't compared to this sleek, expensive job that had been the musician's. As drunk as he'd been, he'd probably remembered that he had the fine wallet and put the money into it, rather than into his own, when he tossed the other wallet away.

He touched the wallet fondly. It was lucky. That's what it was. Lucky. The musician guy had not only given Marty a wad big enough for an evening's entertainment, he'd also given him a wallet that was good to hang onto.

Much of Marty's hangover was disappearing with his new, fine spirits. He found a bottle in the bathroom that had a couple of drinks left over in it, and he downed these quickly, splashed some cold water over his face, rubbed the moss from his teeth with a Turkish towel, and began to dress.

Marty breakfasted at a fairly ornate and expensive restaurant. He had the works, paid for it with a flourish, and decided to take in a show. There was a war picture playing at one of the edge of the Loop theaters, and Marty decided to drop in and have a look at it. He was just in time for the first matinee, which was rather discouraging, because customers at a first afternoon show were never as well heeled as those at the evening performances.

However, Marty was able to push professional thoughts aside and to concentrate on the screen performance instead of business. After all, he was exceedingly well-heeled and he wouldn't have to work again for another two or three weeks if he didn't feel like it.

Marty walked out on the war picture in the middle of the first reel. He couldn't stomach all that guff about the suckers running out to get their heads shot off. They was just saps, plain saps, and the lingo they sprouted about liberty and justice and all like that was just straight cornoroo. He knew.

AT a billiard parlor, half an hour later, Marty found a few chums to play a little balk-line with. Marty was very good at billiards, and very proud of his ability. His eye was sure, his hands nimble and unerring. His cue-work was of the best.

But he lost twenty dollars to a sharper he'd never seen before, and walked out knowing he'd been taken. He knew he'd been built up to his loss, and that he'd played sucker, but he'd lost on the square and there wasn't any kick he could make about that.

He casually took a paper from a newsstand while the newsboy's back was turned, strolled into a drugstore, ordered a coke, and sat there pondering the race results. After a bit, he ordered a complete luncheon, which he topped off with several extra pieces of pie.

On his way out of the drugstore, past the cashier, Marty paid the nickel check he received for his coke, pocketed the eighty-cent check he'd gotten for the luncheon. This small profit pleased him.

Marty stopped at Gibby's Cigar and Magazine Store to place a few racing bets and pass the time of day. There he encountered Leo The Louse, a swarthy, heavy-set operator whose specialty was fleecing visiting school-marms on blackmail charges.

"How's business, kid?" Leo asked.

Marty told him business was good. He asked how Leo fared.

"I dunno, kid. Seen the papers today?"

Marty was puzzled. "Yeah, I seen them."

"Read the front page?"

Marty was pained. "You know I don't read that pap. I read the jokes and the races, that's all."

Leo took the paper out from under Marty's arm. He flipped it open so that the front page was visible.

"Looka that," he said.

Marty blinked at the headline.

POLICE SWEAR DEATH DUEL ON UNDER-WORLD.

"Heat's on, huh?" Marty deduced.

"You said it."

"Why?" Marty demanded indignantly.

"You dope, don't you read no further than your nose?" Leo demanded disgustedly. He opened the paper again, pointed a stubby finger at the smaller heads on the front page.

Marty stared.

SLAYINGS HAVE OFFICIALS AROUSED.

Another:

DRAGNET FOR ALL CRIMINALS SEEN AS POLICE

SEEK SOLUTION OF FOURTH RIPPER MURDER IN WEEK.

"Well, I'm damned," Marty confessed. "The net, huh?"

"That means they might be bothering us," Leo said. "That means that maybe we'd be smart to lay low for a while and knock off work until it all blows over."

"Ahhhhh," said Marty, "g'wan. That don't mean nothing."

Leo shook his head. "Maybe you think it don't. Maybe I think it does. Anyway, I'm taking it easy. That's always the way, this so-called Jack the Ripper who's committed them four murders this last week, he's an amatoor if I ever seen one. Them nut killers is all amatoors. But what happens, we professional heist operators has gotta suffer on accounta an amatoor's blunders."

Marty picked up the contagion of Leo's indignation.

"Yeah," he said. "The rat!"

MARTY placed his bets, bid the time of day to Leo, and left the cigar store. His recent conversation, however, left him no peace of mind as he strolled slowly down State Street in the direction of his favorite tavern.

That dragnet business was no good. Even if they didn't nab you for what they wanted, they always found something else. Marty had been the victim of general dragnets several times before. They weren't pleasant. Maybe Leo had something. Maybe it would be smart to stop operating for a few days, maybe a week, until this thing blew over. Hell, he had enough dough. Almost three hundred bucks—well, about two-fifty anyway. That was enough to see him through a couple of weeks, provided that he didn't go on any benders.

Marty stroked his weasel chin. "Yeah," he muttered. "Maybe Leo ain't so dumb. Maybe it's smart I should take myself a vacation of a coupla weeks."

It was a source of annoyance to Marty that he felt ill at ease passing the uniformed copper on the corner a moment later. Hell, his nerves were getting bad, he told himself.

"A little layoff," he decided, "don't hurt nobody."

Marty hurried onward, suddenly anxious to get to his hotel room. The nervousness the sight of the copper had brought on was now increasing.

He stopped at a liquor store several blocks from his hotel, and ten minutes later was safely closeted with a bottle in his room.

After a snort or two, Marty pulled forth his lucky wallet and examined once again its smooth, fine leather texture. It was almost as soft as satin, almost as smooth as human skin.

He moved from his pleasurable examination to the even more satisfying examination of the billfold's contents.

Flick-counting the bills with his thumb, Marty stopped short, stared popeyed at the roll, then counted again, carefully and slowly.

His voice was hoarse as he spoke aloud.

"Geeeeze, four hundred and twenty smackers!"

There should, of course, have been something less than two hundred and fifty dollars. There should not, under any circumstances, have been such an appreciable increase.

Marty counted the money again, this time swiftly. There was no doubt about it. Absolutely no doubt. Somewhere, somehow, the contents of his wallet had increased.

Marty tore the bills from the billfold, spread them out on his bed, counted them feverishly. He licked his lips, swallowed uncertainly. He felt a feverishly greedy elation at his discovery but was somehow uncertain in his joy.

"But how?" he muttered. "How did I pick up this extra moola?"

It occurred to him that he might have miscounted earlier in the day when he had first discovered the billfold. But he knew that such an error would have been in direct contradiction to his habits of a double dozen years. No, that could not possibly serve as an explanation.

Marty put the money carefully back into the sleek wallet, put the wallet in his shirt pocket, and had a drink on his discovery. Then he had another. The succession that followed was inevitable.

IN THE room adjoining his own, someone had turned on his radio more loudly than necessary. A newscast was in progress, and Marty found himself unwillingly listening to the announcer's voice.

"Police Commissioner Eaker has promised that the general criminal dragnet he forecast earlier today will be started without further delay," the announcer was saying. "This declaration comes as a result of two more 'Jack The Ripper' killings which were discovered today. The badly mutilated body of an unidentified man, discovered early this morning in an alley in the Ravenswood district, and the similarly mutilated body found late this afternoon on a South Side beach, brings the number of such murders to six, all perpetrated within the last ten days."

Marty had no way of shutting off his neighbor's radio. But he was able to walk into his bathroom and turn both washbowl spigots on full. Their noise drowned out the announcer's voice.

His hand was not too steady as he poured himself a long hooker a moment later. The announcer had reminded him all too forcefully of the dragnet he feared, and had added positive prediction to his fear by stating that the dragnet was no longer in the planned stages, but was starting immediately.

"Hell," Marty said, disgusted with himself. "Supposing they pinch me. I kin get sprang inna hour. Besides, I got this dough. I ain't no vag. I kin stand my own bail."

He had succeeded only in half reassuring himself, however. In the back of his mind was the memory of more than one occasion when—picked up in a dragnet—he had been unable to spring himself with any such ease. On those occasions, however, he told himself, it had been different. He had not had the money he now possessed. Nor had he had the cockiness his present affluence gave him.

He had another drink, while considering this. He was now reaching a condition of bolstered ego. A devil-may-care sort of recklessness was taking hold of him, pushing aside the inborn caution of criminal experience.

He took the wallet from his pocket again, opened it, removed the money, rifled it speculatively, put it back in the wallet.

"Hell," he muttered a trifle thickly, "they ain't got nothing on me."

He put the wallet back in his pocket, looked about for his coat, donned it, struggled into his topcoat, found his hat and started for the door.

Once outside his hotel, Marty hesitated a moment, then decided to find a saloon which was not so likely to be subject to a police raid.

A taxi was passing, and Marty hailed it. He gave the driver the address of a downtown bistro which, to Marty's mind, was a most respectable place.

Hell, he thought, settling back against the cushions, if he was going to have a time of it, he might as well enjoy himself among the élite, and in surroundings which were the best.

Marty magnanimously told the driver to keep the change when he paid him off with a dollar bill in front of the semi-swank bar he'd selected.

Marty was already going through the doors of the place when the driver, staring at the bill, called out:

"Hey! What the—"

The driver's jaws suddenly clamped shut, he folded the bill neatly, put it in his pocket, stared hard at the door through which Marty had vanished, then, grim-faced, threw the cab into gear and roared away from the curb.

INSIDE the plush surroundings of the bistro, Marty found a place at the bar, ordered a double Scotch and soda, and sat back on his stool to drink in the higher-priced atmosphere which was the hallmark of the place.

This wasn't the sort of joint to be raided. He'd be perfectly safe here from any dragnet stuff. It occurred to him that he might even be smart to register at the hotel of which this bar was a part. He'd be safer in its confines than he would in his own cheap dollar-a-day hideout.

The bartender returned with Marty's double Scotch. Marty found the sleek-soft wallet, removed a twenty-dollar bill from it casually and flipped it across the bar.

The bartender picked it up, to Marty's disgust, without a second glance or any indication that he was impressed by the bulging wallet from which it came.

Marty watched him carry it to the cash register, ring up the sale and begin to shove it in the drawer of the till. The bartender's back was to Marty, so he didn't see the sudden whitening of the man's face, the swift horrified alarm that came into his eyes.

But Marty did see the man swing around toward him, twenty-dollar bill in his hand, and fix him with a shocked stare.

The bartender's reaction was not at all what the little pickpocket had expected. It caught Marty quite by surprise and nettled him considerably.

Suddenly the bartender had returned to where Marty sat, the bill still in his hand, and was standing there before him, white-faced and distraught.

"Say, mister—" the barkeep began.

Marty cut him off.

"Whatsa matta? What's eating you?"

"This," the bartender said, shoving the bill toward him. "How did you come by this bill?"

Marty stared down at the bill, bewildered.

"Whatsa matter with it?" he demanded.

"Good God, man, didn't you notice?"

Marty squinted at the bill through eyes clouded by alcohol. And then he saw the inch-wide smudge in the corner of the twenty. It was a red smudge, a sticky smudge. A red, sticky smudge to which a strand of unmistakably human hair was stuck.

Marty almost broke his glass in the sudden horrified impulse that made his fists squeeze together hard. He felt suddenly out of breath, panic-stricken. His gimlet eyes bugged.

"Blood and hair," the bartender whispered huskily. "How do you explain it, mister?"

Marty's mental gears were grinding furiously in an effort to set his nimble wits into motion. They took hold, but his effort to keep a straight face didn't match the quick alibi that popped from his lips.

"I—I hadda accident," Marty heard himself saying. "Cut myself a little while back onna window."

Marty glanced at the mirror behind the bar, then, and his reflection told him all too clearly that his effort to keep a poker face to match the alibi had failed. And, from the expression on the bartender's face, so had the alibi itself.

"Where," he demanded suspiciously, "did you cut yourself?"

"Gimme the bill if you don't want it," Marty croaked hoarsely. He pulled out his wallet, dug desperately in it until he found a dollar bill. He shoved this across the counter, grabbed for the twenty.

"Just a minute!" the bartender exclaimed, grabbing the twenty just as Marty's fingers touched it.

They both pulled at the bill simultaneously. It ripped apart.

MARTY was badly frightened now, He looked around, saw that the scene was being watched by the other customers in the place. His panic increased. He could think only of flight.

He pushed himself back from the stool. It tipped sideways, crashing to the floor. He turned, bolted for the door.

"Hey!" the bartender shouted. "Stop that—"

The rest of the cry was lost to Marty's ears. He was in the street, running, moving south along Wabash Avenue as though pursued by a million demons.

His breath was coming hard now, searing his lungs, and the blurred vision he had of pedestrians' faces as he passed them on the run told him that he was drawing too much attention to himself. He turned down the first alley he came to, slowed to a gasping walk. He had to walk, his legs could run no further.

Wildly, Marty looked back over his shoulder. He could see no signs of pursuit. His gasping sob was one of relief. He stopped, leaning against the rusty lower braces of a fire-escape foundation.

Though it was cold, perspiration ran in rivulets down Marty's forehead, soaked his shirt to his back. The ache was leaving his lungs, strength was returning to his legs, and his dazed brain was trying to comprehend what had happened.

THAT bill... bloody money. What the hell? How? Why? Marty found the wallet, opened it with trembling fingers. It was fatter than it had been before, considerably fatter.

He forced himself to count it. Five, twenty, a hundred, a hundred and fifty, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred, four-fifty, sixty, five hundred dollars! More had been added!

It was while he counted them dazedly the second time that he realized that many of the bills were sticky, bloodstained. Marty's sob was terrified. It was not the money, not the bloodstains, that made him sickly frightened. It was the implication, overwhelmingly, horribly insinuating, that filled his soul with terror.

Suddenly he became aware of the soft, silken texture of the wallet in his hand. Not as he had been aware of it before, however, not with the pleasure of knowing that it was fine and expensive. This new awareness was different, frightening. There was some thing hideously familiar in the softness of the leather, something he could not bring himself to name, something that stuck in the passages of his mind and sent all other thoughts tumbling one upon the other in a jumble of panic.

He became once more aware of where he was, of the sounds of traffic, the noise of the Loop everywhere about him. It crashed in on his ears thunderously as if the gates of his hearing had suddenly been opened to its flood.

In a daze that was half-terror, half-drunkenness, he crouched there, shrinking up against the side of the building, staring down in horror at the wallet in his hands.

He shrieked, trying to throw the thing from him. But it seemed adhesively a part of his hands. He shook his hands wildly, wringing them together hysterically in an effort to wash the wallet from them. He could not rid himself of it.

ACROSS the alley there was a door.

It was the fear of pursuit that moved him toward it, made him hurl himself against it. The door was unlocked, and Marty tumbled through it as it gave before his slight weight.

He landed on his shoulder and side, jarringly. And as he climbed wildly to his feet, he saw that he was in some kind of a storage room, musty and dimly lighted by a single bulb hanging from a cobwebbed cord above a pile of packing-cases in a corner.

The door through which he'd hurled himself had closed as it rebounded from his impact.

He stood there, staring wildly at the emptiness of the room, his body shaking in convulsions of terror. He didn't dare look down at his hands. The wallet was still in them, his fingers closed tightly around the silken smooth leather, powerless to release their grasp on it.

And it was then that he realized there was someone else in the room. Even though he could neither see nor hear the other person, Marty knew he was not alone. He could feel the presence of the other, and he knew, without having to look, that his companion in the room lurked behind those packing cases in the corner.

He found himself moving toward that corner of the room in spite of the screaming fear that told him not to. His face was bathed in sweat, his balding hair plastered flat against his rat-like skull. His steps were slow, deliberate, like the mechanical motions of a powerless puppet.

They drew him irresistibly toward the corner of the room.

Saliva drooled from the corners of the pickpocket's mouth, his stare was idiotic, his mechanical steps grew shuffling.

And then the other person stepped out from behind the packing cases.

Marty had known instinctively who that other person was. But his appearance brought a dull moan from Marty's sweat-caked lips.

He was tall, cadaverously thin. His face was long, horse-like, and his eyes were dark, sunken sockets from which a pair of yellow-gray sparks flickered mockingly. His hair was long, its bristly gray strands coming to his collar. He wore a gabardine coat which hung shroud-like over his bony frame.

It was the musician from whom Marty had stolen the wallet on the elevated platform.

"No," Marty gurgled. "No. Damn you—" His throat constricted and he could say nothing more.

The tall, cadaverous, sunken-eyed man in the flapping gabardine coat spoke expressionlessly.

"You have brought it back to me."

His eyes didn't move from Marty's face, but the pickpocket knew what he meant.

The sunken-eyed man stepped back as Marty shuffled forward. He matched his steps to the pickpocket's, retreating as Marty advanced, until they were behind the packing cases.

Then the cadaverous fellow spoke again.

"Hand it to me," he said tonelessly.

He had stopped, his back against the packing cases, his thin, claw-like right hand extended toward the pickpocket. But Marty didn't notice the outstretched hand. He was staring in awful fascination at the open cello case which lay beside the other's feet. The inside edges of the case were stained a brownish red, a freshly sticky red.

And the contents of the case sent Marty reeling backward as screaming insanity shred the remaining fibers of his reason.

The gaunt, gray-coated figure grinned ghoulishly.

"Yes, human skin. I will make a wallet even softer than the one you have brought back to me."

Something burst inside Marty Merkin's brain then, and he began to giggle. Then his laughter rose shrilly to a higher, louder pitch. He screamed harshly, insanely, and laughed again, saliva sliding down the corners of his mouth, tears pouring from his eyes. He was screaming and laughing and sobbing all at once, and the wallet was clutched in his hands ... the soft, satin-like wallet ... the wallet as smooth as silk ... smooth as human skin, which it was....

THEY found Marty Merkin beside the ghastly cello case some hours later. The wallet was still in his hands, and he was crumpled inertly over it, laughing and sobbing and gibbering idiotically.

There was no one in that storage room, of course, save the utterly insane little pickpocket, the gruesome evidence in the bloodstained case, and the horribly damning wallet of human flesh.

Perhaps the judgment of the court might have been more fair had Marty been committed to a mad house, as the attorney for his defense pleaded. But public indignation toward the ripper-killer—and the evidence that he was the killer was undeniable—insisted on the supreme penalty.

He was babbling idiotically about the man in the gabardine coat even to the moment they turned on the current of the electric chair. Which was ridiculous, of course. For had there been a man such as the one he droolingly insisted existed, the ripper-killings would not have ceased with Marty Merkin's death.

Yet they did cease then. At least around that section of the world. There might have been others. Somewhere else....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.