RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

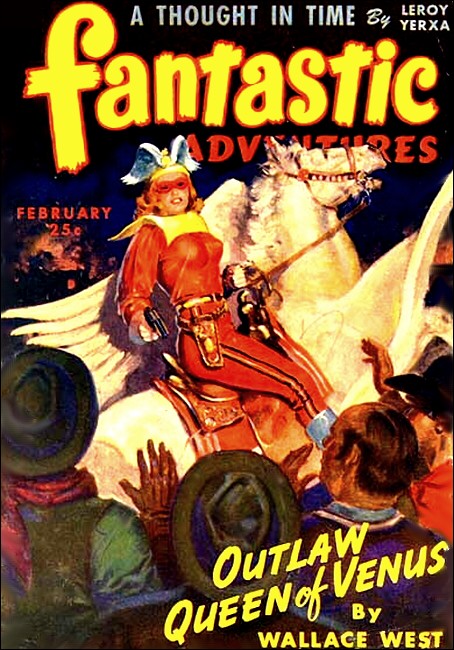

Fantastic Adventures, February 1944, with "The Place Is Familiar"

Kerwin whirled back in time to see a hand holding out a bit of paper.

Ghosts can be a definite asset, Kerwin discovered,

if you can find a way to persuade them to cooperate.

IT was one of those balmy late New England spring days and everything along the country-side was fresh and verdant and pretty wonderful. We had been about four hours on the road from New York—four hours away from the stink of carbon monoxide, the scream of traffic and the hundred million other nerve-shattering nuisances that people call life in the big city.

I filled my lungs with fresh New England air.

"What a couple of fools we were," I told Lynn.

She didn't answer. She was looking somewhat stonily at the crouching chrome nymph atop the hood of our low-slung convertible.

This didn't faze me. Lynn was going to take a lot of selling on this idea, and the battles we had had over it in the past month were unrivalled on any list in the War Atlas.

I turned my attention back to the road.

It had been almost a month to the day when I told Lynn that I was through with the job I'd been holding down in her father's brokerage house—was through with the stupid, smug, money-counting monotony of the life I had been leading.

Naturally she thought I was kidding.

"That's very funny, Tommy," Lynn had smiled, "and I suppose it's prompted by a chance encounter with one of your friends from your Bohemian and collegiate periods."

"I'll ignore that remark," I told her pleasantly enough, "and try to make my point more clear. I'm through, finished, washed-up with this washed-out parody of a life I've been living. When we married two years ago you persuaded me to step into your father's firm just long enough to pile up a nest egg to tide me over for a year working on that book in my system."

A knowing look had come into Lynn's eyes. Her voice suddenly took on a too sweetly humoring tone.

"Now, Tommy," she began, "haven't we gone over this ground before?"

"Yes indeed," I agreed.

"Then it is really very silly, isn't it, to go into the matter again when we've both agreed—"

I cut her off. "We've never agreed on anything concerning this issue, Lynn, and you know it. The last time I brought it up was over six months ago. You pointed out, at the time, that it was ridiculous to consider the matter since we hadn't nearly enough put away to tide us over the year of my big effort."

"And the situation isn't altered a bit since that time, Tommy," Lynn said. "You've still got to face the same cold facts. We're quite able to live comfortably and with a reasonable metropolitan decency on your salary. But it just happens that we can never get a cent put aside in the bank. What do you expect us to live on while you're off in some deep forest for a year banging away at a typewriter?" I smiled.

"I'll ignore the forest remark, since you know damned well that all I had in mind was a place in New England—something with peace and quiet and serenity."

Lynn cut me off.

"Well, forest, farm, or houseboat, we still just wouldn't be able to manage it."

I held up my hand, grinning like a cat picking canary feathers from its front teeth.

"But that, my pet, is precisely where you are in error. We have just enough to take care of the matter comfortably."

Lynn almost lost her lovely white teeth in surprise. And while she was doing a double take, I continued to smirk.

"Wha-what on earth are you talking about?" she spluttered.

"I am merely announcing the fact that I have at present in a private bank account some four thousand dollars, gained within the last three months on modest stock speculations of my own. And that, takes care of that."

It had.

Not as simply as that of course. My announcement had been merely the opening gun in a month-long siege. Lynn used every device known to the wiles of women in an effort to shake me from my purpose. She sulked, she cajoled, she pleaded, she shrilled, and, of course, wept profusely. But I went right along my merry way visiting real estate brokers, renting agents and resort proprietors in my search for a suitable Shang-ri-la.

When, at the end of three weeks, I'd picked the site of my great adventure, I announced the fact to Lynn. That was the signal for her to rush the reserves into the fray—said reserves being her father—also my employer—her mother, and her somewhat neurotic sister, Katherine.

I had expected this. I was all set to trump her ace in the hole. All it took was dogged, solid refusal all around. Old Oliver Jerem, my dear father-in-law, acted about as could be expected. He warned me against my folly from each of his dual roles.

"This is quite preposterous, Thomas," he boomed. "Absolutely unheard of. The thought of Lynn becoming some—some farmhand is absolutely ridiculous. She would be utterly miserable under any such circumstances. She has been raised for something quite a lot better than what you are planning to force her into."

"Undoubtedly you raised her," I agreed amiably enough. "And undoubtedly it must have been some job. But whether or not you raised her, I married her. She is my wife. I think that establishes my viewpoint clearly enough."

Then, of course, the old boy had taken another tack. He brought in, but heavily, his second role—that of my employer.

"Is it that you are dissatisfied with your position in our firm, Thomas? If that's the case, young man, let me assure you that the board of directors and I have been giving considerable attention to your progress of late. We feel that you're just ready for a big step upward. There isn't a young man on Wall Street who wouldn't give a million dollars for a chance such as yours. Any idiocy on your point in your career would be disastrous. I'd never be able to explain it to the board, and this great chance would undoubtedly be lost you forever."

"If you must explain it to the board," I told him, "you might say that I have never enjoyed working with or for them in their marts of money, nor had ever any intention of making a lifetime job of wearing their harness. I am a writer. Or at least I think I am, enough to take a whack at trying to prove it. If it turns out that I'm a dud, well, perhaps I'll slide meekly back into whatever niche they can make for me. But I don't think it's going to turn out that way. Now, do you think that would be sufficient explanation?"

LYNN'S mother tried her hand at that point. "But, Tommy, it is so utterly insane. If you really want to write I am sure Oliver could make some connections with some solid, sensible, financial journals that would be only too glad to have you contribute articles to them now and then."

I didn't have any trouble at all squelching her brief, futile, and somewhat hysterical two-cents worth.

"In which case," I smiled sweetly, "I'd undoubtedly wind up turning out all my copy on an adding machine instead of a typewriter. I'm afraid you didn't get the idea at all. I want to write; not bore a lot of bumble-headed business big-shots into a stupor."

Lynn's neurotic sister, Katherine, had strangely enough kept out of it. And I looked expectantly to her for a few well-chosen words on my future. She didn't have any, but the snide glances she and her tailor's dummy husband, Walter, exchanged, seemed just a little too secretive to suit me.

I looked around the family circle then to Lynn.

"It's been so nice to have had this little talk, and even better still to clear the air. Now I think we'd better be going. There is so much to be done in tying up the loose ends of our past life, that we'll have to do a lot of rushing if we are going to be able to move into the little New England place I have picked out on the day I've arranged for."

That had been the climax—but not entirely the end of the matter. Lynn had with a great deal of martyrdom helped a bit in tying up some of the loose ends. There was our little too-expensive apartment in Manhattan to be gotten rid of, a matter of storage for much of our gilt-edged furnishings, and my solemnly worded resignation from Jerem and Jeffers, Investment Brokers, Inc., and the usual last minute extrania which crop up to plague any such departure.

But at last we were on our way—and this was it.

Lynn still was carrying a shield of martyrdom and a considerable amount of hostility. But she was with me, beside me in fact, and we were now approximately two miles from Chatam, the sleepy, pleasant little New England village beyond which lay our new home.

Waiting for us in Chatham would be a short, thin-featured, nasal-voiced realty dealer named, appropriately enough, Abner Land. He was a representative of the New York firm through which I had located the comfortable, cleverly modernized New England farmhouse in which we would make our stay. Land had the lease ready to be signed, sealed and turned over. In his possession too, were the keys and information concerning the handywoman and cook I had engaged to make Lynn's martyred lot somewhat less vulnerable to squawks.

IT was Friday and scarcely noon.

Lynn and I had managed to get an early start, and I had figured this to be a particularly bright idea inasmuch as it would be better for Lynn's first sight of the place to occur in the bright sunshine of such an ultra-pleasant sunny afternoon.

The place I had rented was really quite a find and, frankly, I was damned well pleased with myself. It was a two-story, eight-roomed affair that had only last summer been done over completely on the specifications of a well-known architect who had taken a fancy to the place, bought it, done the remodeling, and for some zany and temperamental reason stayed there only a couple of weeks. It hadn't been occupied since, but was—thanks to the directions of the New York realty firm—now awaiting us in perfectly ship-shape condition.

I had no delusions that Lynn's first glimpse of the house was going to be all that would be necessary to change her from blackness and rebellion to sweetness and light. But certainly she'd be forced into a grudging sort of liking for the place, and some of the ice at present encrusting her attitude would be thawed. The additional melting—which would of course take a little bit more time—would be up to me. And I was determined to carry through a concerted softening and selling campaign that would eventually have her chirping with a robin-like delight at our new life in our new surroundings.

Lynn suddenly said: "How much farther on is Chatam?"

"A few minutes more, baby," I told her. "You'll really get a kick out of the little village. It's hard to find anything there that's changed since the days of Ichabod Crane. Characters are strictly Yankee, strictly rustic, strictly nice people. It'll take a little time for us to get on really friendly terms with them, since they aren't the sort to accept strangers—particularly big city strangers—with pop-eyed joy."

"I'm sure I'll love it," Lynn said icily. "Perhaps I'll be able to go to tatting circles with the women of the vesper society, and you'll be making speeches in the town hall, in no time at all. I can scarcely wait."

I sighed, turned my attention back to the road. We were coming to the top of a high hill now, and in the little valley below and beyond it lay the village of Chatam. . . .

IT wasn't hard to find the office of Abner Land. It was smack in the center of the village, right on the main street. He was locking the front door of his place as we pulled up in front of it.

"Hello, there!" I yelled.

He turned, saw the roadster, turned back and opened his office door again.

"How'j'do?" he yelled back nasally. "Was jest going out fer some lunch."

"Come on, baby," I told Lynn, climbing out of the car. "I'd like to have you meet Mr. Land."

"I'd rather wait here in the car," Lynn said frigidly.

"Sure," I grinned. "Sop up some sunshine. I'll only be a minute."

"Made good time," Abner Land observed, as I followed him into his musty little office. "Didn't expect you'd be here till a few hours later."

"We got an early start. Lease all ready to sign?"

Abner Land got out the lease.

"Sure is," he said. "Year's payment in advance, special rate of nine hundred and thirty-two dollars, in full."

I handed him the certified check I'd had made out for that amount, signed the necessary papers including the lease, and he turned over the keys to me.

"How about the cook and handywoman?" I asked. "Been able to find one for us?"

"She'll be out there sometime this afternoon," Land said.

"That's fine," I told him. "Then there's nothing else to take care of."

"Good woman, too," said Abner Land. "Her name's Marthy, Marthy Spingler."

"Huh? I mean, oh—yes, I see. You mean the cook and handywoman," I said. "Of course. Martha Spingler. Fine. We'll be expecting her in time to prepare the dinner."

"Place been all cleaned up, shiny new," Abner Land said. "Everything you'll need, excepting fodder, will be on hand."

"That's fine, Mr. Land," I said, taking his skinny hand and pumping it enthusiastically. "I'm sure everything is going to be just dandy."

Abner Land gave me a grin that I didn't remember as being somewhat peculiar until later.

"Might be at that," he conceded.

OUTSIDE, I started up the car again and turned to grin at Lynn. "We're all set, honey," I told her. "Lease and keys are in my pocket and the world is in our arms. The future is bright and shining, and our cook will be out in time to prepare dinner tonight."

Lynn permitted herself to enter the conversation slightly.

"Let me see the lease," she said. "It might be a good thing if it were looked over carefully. After all, if we should decide that we didn't want to stay on, we wouldn't want to be committed to some ghastly bargain. I understand these Yankee traders are sharp."

I decided to pass over her crack about our deciding that we didn't want to stay on. I took the lease out of my pocket and gave it to her.

We drove along in silence, leaving the little village of Chatam and starting westward in the direction of our new place. Lynn maintained the silent status quo, and from the corner of my eye I could see her frowningly trying to make something from the whereofs and whereases in the fine print.

After a little while, Lynn looked up.

"Tom," she said puzzledly, "it says here that, quote, 'the party of the first part is'... Never mind, skip it."

"Sure," I said, grinning inwardly. Lynn knew as much about such matters as a child, but she wasn't going to pass up an opportunity to pretend differently.

I found the turn fork I was looking for, and we went off along a gravel roadway which—if it proved to be the right one—would bring us to our destination in another fifteen minutes.

"Tom!" Lynn said suddenly and very sharply.

I turned. "What now?"

"It says something here that I don't quite understand," she said. "It says something about nine hundred and thirty-two dollars for the year, paid in advance, as per agreement. What does that mean?"

"Exactly what it says," I told her. "I got the place for a song, merely by paying up one year in advance, rather than a month at a time. Isn't that clear?"

The expression on Lynn's face was peculiar.

"But a year," she wailed, "in advance. If we should decide to leave, to go back to New York. I mean—if we should find something wrong and decide to get out."

I stopped the car abruptly and turned to face my wife.

"Now look, Lynn," I said quietly. "You know that I decided on a year's fling at the typewriter. Not six months or eight months or ten, but a year. This is the place I picked out. This is where we've planned to spend that year. You knew all that, so what reason can you possibly have for objecting to my picking up a bargain price by paying a year in advance?"

Lynn didn't answer immediately. She pursed her pretty l ips and frowned darkly. Then she said:

"But a year seems so final, so positive."

"The decision I made is final, is positive," I reminded her. "I'm not embarking on some gay twenty-day lark, baby. I've quit my job with your dad's firm, we've stored our furniture, given up the apartment, and all in all made a clean, definite break."

LYNN didn't answer. She just turned and stared out the window. I put the car into gear and we started off again. Fifteen minutes later, on the other side of a sharp, tree-banked bend in the road, we came upon our new house.

"This, my love, is it," I told Lynn. "Look once and look again. Isn't it a beauty?"

The place did look swell. It had a fresh paint job, and some clever new landscaping, and was bright and spic and welcoming. I felt enormously pleased with myself, and glanced at Lynn to catch her reaction.

She was obviously surprised. Undoubtedly she had expected to be brought out to some gaunt, gray barn in a dismal forest, and this was a million miles in the opposite direction for any such gloomy forebodings.

Yes, indeed, surprise was certainly all over her face. But she was determined not to admit it vocally.

"It looks nice enough," Lynn said without any particular display of cheerleading enthusiasm.

I got a good firm grip on my temper, remembering my plans to soothe and sell her into an adjustment to it all. There was no sense in having our very entrance into the place marred by a wrangling battle.

"That's good," I said as cheerfully as a realty agent. "That's just fine. I'm awfully glad you like it, Lynn. You don't know how hard I tried to pick a place that would appeal to you."

Which was the truth. I knew Lynn's tastes backward and forward, and I had done my level best to find something which would please her eventually, if not immediately.

Lynn got out as we pulled to a stop in the drive in front of the place. I removed the luggage, got back in, and wheeled the convertible around into the garage at the east side of the house.

When I got back from the garage, Lynn was standing beside the luggage on the flagstone walk, staring meditatively at the house. I grabbed up the luggage, and took a deep, gymnasium instructor's breath.

"Ahhhh!" I exhaled. "This is the life—and this is the place to live it! Right, baby?"

Lynn didn't answer that one. She just walked along beside me in silence as we went up the walk....

MOST of our luggage had been unpacked, and clothes placed in order, and the eight rooms of the place inspected one by one inside of the first two hours. Then Lynn and I settled down in the big, roomy cheerfulness of the remodeled parlor, and I tried to get a blaze going in the fireplace.

Lynn was deep in a book she'd started back in town, and didn't look up from it until the first traces of smoke began to seep grayishly back into the living room.

"What on earth are you doing?" she demanded.

I told her that I thought I was making a fire. She told me why didn't I go ahead and make one, then, instead of filling the place with smoke that was enough to choke a person.

I managed to keep my temper, and continued at my fire-making chores, gathering more and more wood from the basket beside the hearth and stuffing loose newspaper pages and innumerable matches into the smoking disorder.

The fumes from my efforts began to get a little worse.

Lynn started to cough. I gave her a quick glance and saw that I was being glared at—but good. The smoke was beginning to fill my eyes and ears and nose, and none of it seemed to want to go up the chimney the way well-trained smoke does.

"Good heavens!" Lynn cried exasperatedly. "Let me fix that thing."

She got up and stamped angrily over beside me. She bent over, leaned forward, and reached up and into the fireplace. There was a sharp noise of something iron being pulled open, and when Lynn sat back on her heels, the smoke was suddenly well-behaved and coursing upward through the chimney.

"You might have had sense enough to open the vent," she told me. "Oddly enough, it's often a great help to a fireplace."

I didn't say anything to that. After all, there wasn't anything that could be said. I left the fireplace and the living room and went back into the kitchen to prowl through the larders and see what would be needed in the way of supplies and foodstuffs.

I had almost completed my list when Lynn came out. She asked me what I was doing and I told her.

"I can drive into town and buy the stuff," I said. "I don't imagine we can expect our cook to bring tonight's dinner along with her."

Lynn nodded abstractedly.

"You might try to pick up a nice-sized turkey, Tom," she said suddenly, "for tomorrow night's dinner."

I nodded happily, glad that she was beginning to pitch in with suggestions.

"How many pounds?"

"I think fifteen would be fine," Lynn said.

"Fifteen? That's a lot of bird for two people, baby."

Lynn's eyebrows raised in innocent—too innocent—surprise.

"Oh, didn't I tell you, Tom? I asked Mother and Father and Katherine and Walter out for sort of a house-warming. They'll arrive late tomorrow and leave early sometime Sunday morning."

Of course she hadn't told me. And of course she had deliberately waited until now to do so. It was suspicious, damned suspicious, and I didn't like the sound of it a bit. But I was trying to smooth Lynn's feathers and there was no reasonable objection I could make against their coming.

So I said: "No, Lynn. You didn't tell me about it. But that's fine. That's just fine. I'd like to have them see the place."

"So," said Lynn ambiguously, "would I."

ON the way into the village for groceries, I did a considerable amount of thinking about the guest deluge that would descend on us the following afternoon. Obviously, it was an inspection trip of sorts, and, just as obviously, there was more behind it than immediately met my eye. My adversaries had not retired in complete confusion, apparently, and the victory I thought I had scored seemed now to have been something less than a rout.

Maybe old Oliver Jerem, Lynn's papa and my ex-boss, was going to bring along a few cards he had forgotten to play in our original argument. Maybe he was going to do something idiotic like refusing to accept my resignation.

It was hard to say what the shrewd-minded old financial bandit had under his handsome white head.

I wondered if the idea for the visit had been Lynn's or her family's, and decided it had probably been the latter's. While she was near them, Lynn's family managed to hoodwink her into anything they wanted. They always did so cleverly, playing on her love for them and their deep affection for her. This fact, of course, had been one of the flies in our marital ointment ever since we'd walked out of the church into a shower of rice.

It had been the clever manipulations of Lynn's family that had forced me into taking that job with her father's firm immediately on our return from our honeymoon. I hadn't intended to do anything of the sort, of course. It had been my plan to use the several thousand I had in the bank at the time to purchase a cabin in the Catskills and get to work on my novel.

But Lynn's family had persuaded her that they were thinking only in terms of our mutual good when they suggested that a nice job awaited me in Jerem and Jeffers brokerage house.

"Just for a bit, dear," they'd told Lynn, "until Tommy has saved enough to carry out his plans handsomely."

I had been trapped into taking the job.

The salary had been good enough, and normal living would have enabled us to save enough in a year—combined with the two grand I had in the bank—to enable me to go through with my delayed plans in super style. But somehow we weren't able to save a damned nickel; and in less than six months, I had gone through the two thousand as well. Lynn's family had been instrumental in this removal of my claws. The merry-go-round of night life and parties and week-ends at swank country clubs on which we rode kept us broke, and was forced upon us by the shrewd Papa Oliver Jerem, et al. They knew, of course, that dough would make me independent, and that with such independence I might do any crazy thing that came into my head—like quitting my much-loathed job and starting my chosen career. So it was seen to that we always had just enough dough to keep up the pace imposed upon us, and never enough to put any away.

It took me almost a year and a half to discover their system, and at the end of that time I started getting a little smart for myself. I watched and waited until a chance came along, and put five hundred bucks on the nose of some stock shares. They came across the line winners, and I had outfoxed the entire Jerem family for good.

A TRUCK, rolling heavily along the highway and holding close to the centerline, made me drop my mental rehashing and concentrate on getting out of its way.

Three minutes later I was in Chatam.

The characters lolling around the local grocery store, which was actually a general store, looked like something out of Floyd Davis illustrations. Yes-siree.

The grocer, or storekeeper, to be more exact, was a lean, long, hawk-nosed New Englander with a Yankee twang that sounded like piano strings breaking.

"Yessiree," he said. "What can I do fer you."

I got out the grocery list and handed it to him.

"I'd like everything you have that's on this list," I said.

He scanned the list and looked up at me interestedly.

"Heap of grub," he said.

I agreed that it was.

"You must be the feller moving in tuh the remodeled place off Kingston Road, eh?"

"That's right," I said. "It's certainly a lovely house."

"Oh, I wun't deny that it's attractive tuh look at," he admitted, turning away to get the first of the stuff on the list. There was something grudging, something odd in the way the storekeeper had said that. He came back with a dozen bars of soap, and I asked him:

"What did you mean when you emphasized the to look at?"

The Yankee looked up, putting a stub of pencil behind his ear.

"Did I emphasize that that way?" he asked innocently.

"That's the way I heard it," I told him.

"Wal, now," he twanged. "Mebbe I was a mite careless in my speech. Ferget it." He turned back to the list, scanned it, and walked off to get more supplies.

I was getting impatient. When he came back again, I asked:

"Listen, is there something wrong with the house I rented? Does it have leaks or landslides or earthquakes or something? After all, if there's something out of the way about it, I ought to find out now. I've paid up a year's rental in advance on it, you know."

The storekeeper looked at me sharply.

"Did Abner Land sign you up tuh a year's lease, rent paid in advance?" he demanded.

"That's right," I said. "I paid him just a few hours ago."

My Yankee friend broke into cackling laughter.

"Wal, I never!" he exclaimed. "That's a hot'un, all right. That's rich." He cackled some more. "He's a sharp'un, that Abner Land. Slick dealing, all right!"

I was getting a little alarmed and a little frantic.

"Listen," I broke in on my store-keeping informer's happy cackling. "Will you tell me why you think my signing a lease on that place and signing for it in advance is so hilarious?"

The Yankee storekeeper stopped laughing.

"Why, stranger," he said "I don't see why not. The place is a plumb white eleefant. It's jinxed, that's what. That there architect feller who remodeled it from an old broken down deserted farmhouse only stayed there ten days afore he left and never come back."

"But what's wrong with it?" I demanded.

The storekeeper went back to my shopping list, taking his stub pencil from behind his ear. He looked up long enough to remark casually:

"Everything."

I was getting sore. I leaned across the counter and tapped him on the chest.

"Look, friend," I said. "You started this. Will you please conclude it coherently? What in the hell is the matter with the place I've rented—specifically?"

THE storekeeper gave me a glance, turned away to grab a paper bag, snap it open, and bend over the egg-case behind the counter. He didn't answer until he'd filled the bag with two dozen eggs. Then he straightened up and said:

"Hants."

I blinked.

"Hants? What do you mean by—oh, I get it. You mean haunts?"

"That's right. Hants. That's what's wrong."

The wave of relief that swept over me was wonderful. I looked at the lean, dour-faced Yankee storekeeper tolerantly. He was considerably more rustic that I had imagined.

"Well, well," I grinned. "So the place is haunted."

"Yup."

"That's very funny," I laughed.

"That all depends," said the Yankee.

"Depends on what?"

"Your sense of humor," he said.

I gave him an amused smile. He shrugged, picked up the grocery list and walked to the back of the store to complete the rest of it. When he finally returned, arms full of packages, he put them on the counter with the rest, and said:

"That'll be eight dollars and twenty-two cents."

I got out my wallet.

"I suppose there's a legend that goes with the so-called haunted house I've rented?" I asked dryly.

He took the ten dollar bill I handed him and went over to an early vintage cash register to ring up the sale. He returned with a dollar and seventy-eight cents.

"Eight twenty-two, eight twenty-five, eight seventy-five, nine dollars, ten dollars," he said putting the change in my hand. "Thank you, mister. You need some help carrying these out tuh yer car?"

I looked at the packages.

"No, thanks," I said. "I think I can manage okay."

He helped by piling the stuff into my arms.

"Careful of them eggs," he said. "They're pretty close tuh the top."

He came around the counter and stepped ahead of me to hold the door open. I took the packages out to the convertible and dumped them in the front seat beside me.

I was starting the car before I realized that my rustic Yankee storekeeper hadn't answered my last question. He hadn't told me if there was a legend to go with the ridiculous local opinion that the house was "hanted."

I put the car in gear, and mentally decided to make a note to check into the quaint superstition on my next trip to town. It would be interesting to hear, even though undoubtedly pretty much standardized according to the usual legends of its sort.

It occurred to me while driving back from the village that the grocery-general store anecdote would be an amusing thing to relate in detail to Lynn, a humorous touch to help unfreeze her icy attitude.

And it occurred to me less than a split second later that it would be the last thing on earth to tell her, for the very thought that there was something off-key about our new home would be all she'd need. Lynn was a modern somewhat intelligent girl, and definitely not given to superstitions. But, of course, she was a woman. Reason is not the prime motivating factor in any action of a member of that sex.

So I decided to forget the incident as far as Lynn was concerned, and I thanked my private gods that she hadn't heard it first.

There was considerably more to think of, anyway. Things such as the matter of the new cook, the settling down, the starting of my novel and, most important at the moment, the week-end visit by Lynn's relatives. I'd have plenty to keep me busy for a bit, without beginning to seep myself in local native folklore.

I TURNED off Kingston Road and onto the gravel roadway leading to our place some fifteen minutes later, and by that time I was deep in the realization that I had forgotten to get in a supply of liquor, and also forgotten to get the turkey Lynn wanted for the following night's meal. Shrugging them off as best I could, I decided to let both problems ride over until the following day.

Lynn met me at the door after I'd parked the car in the garage.

"The cook has come," she announced.

"Fine," I beamed. "That's great. Like her?"

Lynn followed me into the front room.

"She hasn't cooked anything yet. How can I tell?" she said.

I felt properly rebuffed. I encountered the cook when I marched into the kitchen to dump the load of groceries in my arms. She was a big-boned, tall and angular woman, not especially easy on the most unparticular eyes, and she was busy at the moment polishing the sink.

She looked up at me challengingly.

"Hello," she said. Then, indicating the kitchen table with the end of the small scrub-brush in her hand, she said: "Put them there."

I put them there, while the cook's eyes watched the depositing critically. When I had unburdened myself I turned to face her somewhat uneasily.

"I'm Mr. Kelvin," I began. "I'm—"

She cut me off.

"I got eyes," she reminded me. "You sure don't look like no grocery boy."

The sentence might have had some flattering salvation if she hadn't made it sound as though grocery boys were number one on her hit parade.

"And you are Martha Spingler, is that correct?" I asked, wincing at the rebuff.

"Mrs. Spingler," she corrected me. "My first name is Marthy, all right. But people don't use it less'n they know me a spell longer than you have."

"I'm glad to know you Mrs. Spingler," I murmured, backing a hasty retreat from the kitchen. "There are some—uh—groceries. See if you can whip up an evening meal from them. Anything that might be missing on that list—uh—just order on your own hook."

I went back into the living room. Lynn had taken an armchair close to the fireplace and had her nose buried in that book. I didn't feel particularly like an icebreaker at the moment, so I said:

"Did Martha take the bags upstairs, baby?"

Lynn raised one eye from the page.

"I took them up."

"Oh. Oh. That's swell. Thanks, baby. You shouldn't have done it. I—ah—was going to when I got back from the village."

Lynn didn't say anything to that. Her attention went back to the book. I went into the front hallway and removed my coat, hat and gloves.

THEN I decided to go upstairs and unpack the several small suitcases which Lynn had taken up to our room. The bigger part of the luggage had, of course, been moved up there by yours truly on our arrival that afternoon. The stuff Lynn had taken up amounted to four or five bags of overnight size. However, I knew that in her mind she had now firmly established the notion that she'd done all the baggage work unaided.

My week-end grip and overnight case were on the big four-poster bed in our room when I got up there. They lay open, and much of my stuff had been strewn this way and that across the bedcover.

I was a little bit surprised. If Lynn had started to unpack for me there would have been some pattern of order to the scene. You didn't unpack a bag by ransacking it as thoroughly as my bags had been.

"She's getting nice and spiteful, also," I reasoned. "It's a wonder my shirts and ties and stockings haven't been knotted into granite-like lumps."

It struck me at that moment that—had Lynn been spiteful, or trying to be—she would most certainly have done more than muss up the contents of my luggage, and probably would have done some knotting of neckwear and shirt arms.

I frowned, stepped out of the room and walked over to the staircase. I leaned over the bannister and yelled down:

"Lynn, oh Lynn!"

"Yes?" her voice came faintly and in annoyance from the living room.

"Did you open my luggage?"

"Of course I didn't," her voice snapped, considerably more loud this time.

"I just wondered," I muttered. Then: "I just wondered," I yelled.

I went back into the bedroom and stared at the messily opened bags on the bed. Suddenly I thought of Mrs. Spingler, the cook. Her room was down at the end of the hallway.

Stepping out of the bedroom again, I moved somewhat stealthily down to the door at the far end where Mrs. Spingler was to be quartered. In the back of my mind was the idea that suspicion would be pointed at the dour cook if her luggage had already arrived and was in her room—inasmuch as that would point to the fact that she had already been prowling about upstairs with sufficient opportunity to get into our bedroom and mess up my luggage.

I'd soft-shoed less that three yards when I realized what an asinine idea that was.

If Mrs. Spingler were the malicious sort, she wouldn't take spite out on a total stranger. And if she were dishonest, a professional servant-crook, for example, she would work for us a week or more until she had thoroughly cased the place and decided on what she wanted to run off with. I straightened up out of my crouch and walked back into the bedroom, feeling like a foolish Sherlock Holmes.

Back in the bedroom I sat down and stared gloomily at the opened luggage atop the bed.

Lynn had said that she hadn't opened the luggage. I knew I hadn't opened it. And it was silly to suppose the cook, Mrs. Spingler, could have had anything to do with it.

All right. That was fine. That left only one thing to figure out. Who in the hell did do it?

I fished around for a cigarette, found one in my vest pocket, badly crumpled, smoothed it out and lighted it.

I TURNED my attention to the bed again, and in another minute I was overcome once more by a Sherlock complex. I got up and went over to the bed and looked more closely at the disordered mess of shirts, socks, ties, handkerchiefs, and so forth.

If any clues as to the culprit who had put the stuff into that condition were in evidence, I missed them completely. I went over to the window, tested it, found it locked.

Then I thought to look in the closet.

It was disappointingly barren of culprits, fairly well stocked with Lynn's dresses and my suits. I slammed the closet door shut disgustedly and went back to the chair by the window and sat down.

I told myself that I was making a mountain out of a molehill and an unholy ass out of Thomas Kelvin.

"This is ridiculous," I muttered suddenly, getting up. "The locks on both bags undoubtedly snapped open suddenly as Lynn tossed them on the bed. They probably spilled most of my stuff out on the bed as they sprang open. That's the only reasonable explanation—even if they were both locked the last time I saw them."

I was turning away from the window when I saw the small Ford truck coming up the drive. Lettered on its side was:

CHATAM ELECTRICAL COMPANY. URIAH EPPLY.

The truck stopped in front of the walk, and a small, bald-headed, leather-jacketed, roly-poly chap climbed out. He had a coil of electrical wire in one hand and a tool bag in the other.

I watched him start up the walk, stop, turn around and go back to get something else.

I left the window and went downstairs. Lynn was still in the living room, reading in the armchair near the fireplace. She looked up as I entered.

"What were you doing thumping around up in the attic?" she demanded.

I blinked at her.

"Thumping around up in the attic?" I echoed puzzledly.

"Not thumping, perhaps," Lynn said, "but dragging things around up there, anyway." She glanced at the fireplace. "The sound from the attic carries down through the fireplace here. It was very plain."

I opened my mouth to answer, then thought a minute. The bedroom I had just left was in the south end of the house, not near the attic. The living room was in the north end, and above it two guest bedrooms, and above those, the small attic. What Lynn had said was possible. That is, sounds from the attic, through which the chimney ran, might conceivably come down into the living room.

But I hadn't been in the attic.

"What were you doing up there?" Lynn repeated.

I gagged a moment.

"Oh, nothing much," I gulped. "Nothing at all, really."

The front doorbell rang, at that moment, cutting off the next question that undoubtedly would have followed Lynn's sharply puzzled look.

"I'll answer it," I said hastily.

WHEN I opened the door the little bald fat man from the electrical truck stood there grinning amicably. He had his coil of wire still in one hand, and his tool-bag and a small hacksaw in the other.

"Hello," he said. "I'm Uriah Epply, Chatam Electrical Company. Abner Land sent me out here to connect your telephone and all that."

"Oh," I said. "The telephone. I see. Sure. The telephone and all what?"

The little man brushed by me into the hallway.

"And all that," he said.

I followed him through the hallway and into the living room. Lynn looked up again from her reading.

"The man from the electrical company," I explained. "He's going to connect the telephone and—uh—all that."

Lynn went back to her book without comment.

I followed rotund little Uriah Epply through the living room, the dining-room, and into the kitchen. Mrs. Spingler glanced up sharply at our entrance, looked curiously at Epply, and went back to peeling potatoes.

Epply crossed the kitchen to the door at the far end opening down into the cellar. He turned, at the door, and said:

"Main switch down in the cellar."

I nodded, and he opened the door, found a light-switch on the side of the staircase, snapped it on, and started down the stairs. I followed along behind him.

In the cellar proper, Epply found another light-switch and snapped that on, flooding the place with a sudden glaring illumination.

"You seem to know your way around here," I observed. "You put in all the electrical systems?"

He shook his head, laying down his tool bag and wire coil.

"Nope. Connected the system, though, for the architect fella who had this old place remodeled last year. His contractors come out from New York to lay out the system. Guess he didn't trust us local idjits to get it right. We were only good enough for turning it on when the time came."

"Oh," I said. "I see."

Uriah Epply bent over his bag of tools, opened it, and selected several. Then, whistling sourly through a missing front tooth, he marched over to a wall fuse-and-connection box and opened it.

I went over into a corner and took a seat on a dusty barrel.

"What made the architect move out in such a hurry?" I asked. "Didn't he like the place after he changed it to suit him."

Epply turned from his work long enough to grin.

"He liked it fine. That is, at first." He went back to work.

Mentally I cursed the laconic strain in all New Englanders. I phrased my next question with a little thought, hoping to put it so I'd get a little more than the usual eyedropper full of information.

"What do you mean by that? I mean, what happened? I'm interested in hearing what you know about it."

Uriah Epply tinkered for a moment while he considered the question. Then he turned around and thoughtfully jabbed his round chin with a wire snipper.

"Seems like he—this architect fella—didn't realize that this here house was jinxed. Anyways, if he did know it, he seemed to think he could change the jinx by changing the house. Course he couldn't. House looked mighty different when he got through. But underneath, I guess, it was the same old house. Just a different face, if you see what I mean."

"I see what you mean," I said.

URIAH EPPLY tsked reflectively, and turned back to work. Again I did some mental cursing, and again phrased another question that would bring forth another droplet of information.

"What was it all about?" I asked.

Uriah Epply looked up from his work.

"All what about?"

I felt like screaming. Instead I said:

"The jinx on the house. How did it start? I mean, how did the story about it start? What makes people around here think it's haunted or jinxed, or whatever they think? There must be a local legend about it."

Uriah Epply carefully put his tools on the floor, found a pack of cigarettes in his leather jacket pocket, took one out and lighted it. Then he turned to face me.

"You never heard?" he asked.

I wanted to kick him in the mouth and stamp him into insensibility. What in the hell did he suppose I was asking for, if I'd heard?

"No," I said with amazing calm. "No. I've never heard."

"That so?" Uriah Epply marvelled, his round little face wrinkled in mild astonishment. "That's really funny. The architect fella knew. I mean, he knew before he even bought the place and started remodeling it. He called it all a lot of guff and nonsense, though."

Uriah Epply's pause prompted me to ask despairingly:

"He called what a lot of guff and nonsense?"

"The story about the house," said Epply.

"Oh," I said chokingly. "Oh, I see. Well what is the story about the house?"

If my voice rose on the last three words Epply didn't show any sign of noticing it. He took a reflective drag from his cigarette and smiled.

"I guess you never heard of the Baggat boys, eh?" he said.

"No," I told him. "I never heard of the Baggat boys. What do they have to do with the story?"

Pulling teeth was like picking posies compared to the job of getting information out of this New England electrician. He shook his head wonderingly.

"Most folks around these parts know the history of the Baggat boys from Ebenezer to Zekial," he observed wonderingly. "Sure seems funny you don't know it."

"Maybe," I said carefully, "I haven't been around these parts long enough. And maybe you'll oblige by telling me who in the name of blazes the Baggat boys are."

"Was," corrected Uriah Epply mildly.

"All right," I conceded, "who was they—I mean, were?"

"Ever hear of the James boys?" Epply asked by way of an answer.

"Frank and Jesse?" I asked.

"That's right," said Uriah Epply. "They was a little better known, though than the Baggat boys was."

"Oh," I said, considerably less irritated now that we seemed to be making a little sense. "The Baggat boys were notorious bandits around these parts, eh?"

"Wasn't hardly a bank in all New England they didn't knock over," said Uriah Epply with a touch of local pride in his voice.

"I see. How long ago was that era?"

"Same era as when the James boys was gunning up the wild and woolly west," Epply said. "Come to think, could be why the Baggat boys didn't become better known. Come to think, the James boys probably took all the publicity themselves."

"I see," I told him. "Sounds reasonable. Now tell me how the Baggat boys fit into the legend around this remodeled old New England farmhouse."

OF course, Uriah Epply didn't answer my question directly. "There was two of the Baggat boys," he said. "They was blood brothers. One was Bob Baggat; the other was Hiram Baggat. Bob was the smartest of the two, Hi was the quickest with a gun."

Epply paused and half closed his eyes, as though visualizing Bob Baggat being bright and Hiram Baggat being bloodthirsty. He sighed, opened his eyes again, dropped his cigarette to the floor and crushed it out methodically with his foot.

"How," I said thinly, "do the Baggat boys figure into the superstition around this house?"

Uriah Epply gave me a look of mild surprise.

"Superstition, you say?"

I was beginning to show my irritation and impatience.

"Of course," I snapped. "What else?"

Uriah Epply shrugged his shoulders, raised his eyebrows.

"Don't rightly know what else," he said. "Always looked on it as fact, myself. After all, that's what it is—fact."

"What's fact?"

"The story," said Epply imperturbably. "The whole thing is fact. In history books, old newspapers, right in the Chatam Library you can see the newspaper clippings about the Baggat boys, Bob and Hi. Can't call historic fact like that superstition."

"Please," I begged quietly, "tell me the story. Tell me how they fit into the superst—ah—attitude locally taken about this house."

Uriah Epply grinned.

"Glad to," he said. "Didn't know you'd be interested. Funny thing no one else ain't told you by now. Abner Land, of course, now he wouldn't be likely to tell you. Not and being the real estate man who was trying to rent this house ever since the architect last summer took out and run—"

I cut him off.

"The story," I said hoarsely. "Remember?"

"Sure," acknowledged Epply. "These Baggat boys, like I was telling you, or trying to tell you, was desperadoes—just like Frank and Jesse James was. They lived wild and high and handsome and kept the whole darned countryside in these parts terrorized. Night after night they stuck up bank after bank. High-flying, hell-riding devils they was. Trains, too; stuck up many a train and robbed the mail of the U.S. government no less. Oh, my yes. They was plenty poisonous."

I didn't bother to interrupt again in an effort to get him to the point of the story. There was no sense in that. All I could do was let him ramble. I knew that he'd reach it eventually.

"Well, these Baggat boys, brothers, like I told you," Epply continued, "got away with murder and robbery and Lord knows what all for darned near three, four years. And the more they robbed and shot and the likes, the more people around these parts got madder and madder. But trouble was, as the people got madder and madder, the Baggats got more and more cocky, understand? See how it was?"

I said that I could understand how that would be logical.

"Finally the people round these parts has had just too much from them Baggat boys. They appeal to the governor. Yes sir, right to the governor of this fair state himself. They tell him they want the state militia called out and put on the trail of these here Baggat boys."

EPPLY paused to search through his leather jacket for another cigarette. He found one after a minute, put it in his mouth, and lighted it. He had to wait until the end was burning to suit him before he went on.

"Well, the Baggat boys heard that the governor was sending out the state militia against them, and they sent out a bunch of cocksure challenges to all the villages, defying the troops to get 'em. The Baggat boys was like that, you understand, cocky as hell and proud as twin devils. They was up in the hills a few miles from here, right at the foot of the Henner Mountain, in fact, hiding out. And to show the state troops what they thought of them, they planned to stage a bang-bang bank robbery right under their noses. You see, there was a troop of state militia sent to Chatam, first off."

I was less impatient now, and beginning to be actually concerned with the details of the Baggat boy's and their escapades. I nodded eagerly for Epply to get on with his narration.

But now that the rotund little electrician had been winding me around his little finger, he surprisingly enough didn't take advantage of the situation, He got right on with it.

"The entire town of Chatam was up in arms to think that the Baggat boys picked out their little village to insult that way," Uriah Epply said. "And don't think that the state militia on guard in the village wasn't burned up, either."

"The Baggat brothers sent out notice that they were going to pull a hold-up of the village bank in Chatam?" I asked in astonishment.

"Nothing less," Uriah Epply said. "Sent the notice to the mayor of Chatam himself. Happened that the mayor was also president of the little bank and a colonel in the state militia."

"Good lord," I marveled. "What happened then?"

"The mayor and the entire village, as well as the militia, went plumb crazy mad. They sat up night and day in shifts, all carrying guns and vowing to fill the first sign of anybody looking like a Baggat boy with lead. You see, the Baggat brothers even told the mayor that they was gonna rob the bank within a certain two-week period, starting that very day."

I whistled my admiration at the audacity.

"And when did they try it?" I asked. "Or did they?"

"Try it?" Uriah Epply seemed surprised and a little indignant. "Try it? They did it! And they walked off with thirty thousand dollars right out of town."

"But—" I began.

"Course the entire town and all the state militia was right on their heels," Epply said. "Shooting and hollering and chasing the Baggat boys to beat hell. Understand there wasn't more than couple hundred yards between the Baggat boys's horses' heels and the guns of the pursuing citizenry."

"A few hundred yards?" I gasped.

"Well, maybe half a mile, maybe a mile. No more than that," Uriah Epply amended.

"Did they shake loose from their pursuers?" I asked.

"Nope. Couldn't quite. They had to change their plans when Bob Baggat's horse was hit. They had to take to hiding quick, and they picked out this here old farmhouse."

I LOOKED wordlessly around the cellar, thrilling at the thought that the Baggat boys might possibly have held whispered conferences in the very corner in which I sat.

"Did the townspeople and the militia trace them to here?" I asked.

"Course," said Epply. "Trail was easy to follow. The posse after 'em tracked 'em here in less than three hours after they robbed the bank."

"What about the people who were living in the farmhouse here at the time?" I demanded.

"Baggat boys let 'em loose without killing any," Epply said, "when they saw that the posse had caught up with 'em and was surrounding this here house."

"Gallant gesture," I said.

"Maybe. Maybe they didn't want 'em in the way when the shooting started, interfering with their aim."

"Then the Baggat brothers decided to hold the fort and shoot it out with the posse?" I demanded.

"Course. They was proud. The posse was ringed ten men deep all around the farmhouse. Mouse couldn't sneak thorough in the black of night, without brushing a human's shoe. The Baggats knew all this, but they was damned if they'd face the humiliation of getting captured alive."

"Oooff!" I grunted. "What customers they must have been."

Uriah Epply nodded proudly.

"Sure was. When the posse had the place completely encircled, ten deep like I said, the mayor—who was also a militia colonel—snaked forward on his belly into the clearing edge near the house and hollered for them to surrender. Bob Baggat shot his hat clean off his head, by way of answering."

I nodded in pop-eyed wonder.

"Mayor went back to his posse line and told the boys to open fire at will," Epply continued. "My grandpappy—he died when I was just a youngster—used to tell me about it. He was one of the villagers in the posse. Well, when the mayor gave his order, you never heard the like of noise that started. Bang, bang, bang, bang—it was terrible. Most likely three hundred bullets a minute pouring into that farmhouse on the Baggat boys."

"And that did them in very shortly, I suppose," I said.

Uriah Epply looked indignant.

"Did not," he snorted. "Baggat boys killed eleven men in the posse in less'n forty minutes of that one-sided exchange. The posse kept the house just as completely encircled, but had to fall back out of range."

"It's almost incredible," I said.

"'Tis," said Epply, "but you'll find it in the library down to Chatam any time you want to look. State history has it, too."

"Go ahead," I begged him. "How did it wind up?"

Uriah Epply smiled curiously.

"Hard to say that, completely. I'll explain. The siege lasted six days."

"Six days?" I broke in.

"And one night," added Epply. "Yes-siree. That's how long it lasted. Posse tried to rush the farmhouse ten times in all. Lost two dozen men in killed and wounded trying. They knew the Baggat boys was out of food and water and wasn't sleeping scarce a wink, so they just waited them out after the last try at rushing the place. Safer that way."

"How'd they know when the Baggat boys would be broken?" I asked.

"Every so often they'd let loose with a few hundred bullets into the house and the Baggat boys allus answered fire. They figgered that when they finally let loose with a volley and didn't get any answer, the Baggat boys would be half a day away from dead."

"How did the Baggat brothers hold out on ammunition supply?" I asked.

"They'd picked up some they'd had buried away in a cache nearby. Picked it up in running from the bank, before they made this here farmhouse. They had plenty to stand off a siege."

"And so the Baggat boys didn't answer fire on the sixth day, eh?" I asked.

"The afternoon of the sixth day," Epply specified. "The posse was hopeful, then, and volleyed again around nightfall. The Baggat boys still didn't return the fire. Well, then they rushed the farmhouse, the first line of the posse did, that is. The rest, nine deep, then, kept the ring and waited, just in case. They saw to it that it would be impossible for the Baggat boys to get through the ring, even though they might slip through the front ring rushing the house. Mouse couldn't get through without being seen."

"And the posse found the Baggat boys dead of starvation or bullets, eh?"

Uriah Epply paused to take a deep, contemplative drag from his cigarette. He looked at me and grinned strangely.

"You're wrong," he said. "They didn't find the Baggat boys at all. Not a trace of them."

"Is that right?" I began. Then, as the realization of what Epply had said suddenly dawned on me, I blurted:

"What?"

"That's right. They didn't find a trace," said the rotund little narrator. "They found empty food larders, empty water jugs, empty shells, and a house that was in ribbons with bullet holes everywhere. You couldn't put a quarter on the floors or walls or even the ceiling without touching a bullet hole. But the Baggat boys just wasn't present."

"But that's impossible!" I bleated.

Epply nodded agreeably.

"Sure it was impossible. They couldn't have skipped out at any time during the siege. Like I said, an ant would have been noticed if he tried to get through the ten-deep ring around this here farmhouse. Was just impossible, that's all. Impossible."

"Then they must have been here in the farmhouse," I protested. "In the attic, or down here in the cellar."

"Weren't nowhere in the farmhouse. Every place and nook and board and cranny remaining of this here farmhouse was searched up and down and high and wide. One militia trooper even looked under the rugs on the floor. But the Baggat boys just wasn't to be found."

"But where did they go?" I demanded.

"From the facts of the case, real history, mind you, seems like they didn't go anywhere," Uriah Epply said. "They musta stayed right in this here old farmhouse."

"But that's ridiculous," I protested. "If they'd been in this farmhouse, they'd have been found. Or, at any rate, their bodies would have. It's preposterous to suppose otherwise. Undoubtedly they escaped, through some miracle, and took to the hills. That's the only explanation."

"There's another," said Epply, "that's been considered seriously by folks in Chatam ever since."

"And what's that?"

"That they're still here," said Epply, "even now."

"Absurd," I snorted. But in spite of my opinion and the strength with which I held it, a tiny sliver of a chill jabbed into my spine.

"If you can believe they walked right through a wall of human flesh to freedom," Uriah Epply said calmly, "it isn't a great deal more silly to believe that they're still here in this house, and that they was in this house when the posse searched it, only wasn't seen."

My rotund little New Englander turned around then and began tinkering once more with the electric unit box. It was obviously a sign that the discussion, as far as he was concerned, was ended.

I got up from my barrel and walked over to the stairs.

"It's ridiculous," I said.

Uriah Epply didn't bother answering. I clumped disgustedly up the stairs and into the kitchen....

THE dinner served by Mrs. Spingler that evening was a culinary heaven. It was amazing to think that such a sour old witch could be such an incredibly good cook, and I mentally noted this variance in her outward and utilitarian selves for discussion sometime with a psychiatrist.

The dinner was so delicious that it even worked noticeable improvement on Lynn's disposition.

For that feat alone I would have happily trebled Martha Spingler's wages, had I been able to afford to.

Lynn used much of her improved attitude in discussion of the following day's visit from her family. I chimed in as amiably as I could, keeping away from any angles that might become sparks for an argument, and the meal was finished with a remarkable degree of good feeling.

We sat in the living room, smoking and talking and laughing over reminiscences for several hours after dinner, and Lynn went upstairs and came down again with a fifth of Scotch she had tucked away in one of the steamer trunks.

We opened the bottle and had a few drinks, and a couple of hours after that I almost slipped and told Lynn the silly legend around the history of our new home. But I managed to cover up all right, and kept clear of anything that might trip me into it again.

About ten o'clock Mrs. Spingler—who had been busy at some damned self-made chore in the kitchen—came into the living room to announce that she was going upstairs to her room for some sleep, and inquire about the time we wanted our breakfast.

Lynn told her that we'd probably sleep a little late, and to have our morning meal on the griddle about ten thirty or a quarter to eleven. Mrs. Spingler showed obvious disapproval of such a wastrel's breakfast hour, and went upstairs muttering things about city people.

I turned on the radio and got some news, and about fifteen minutes later Lynn yawned and announced that she was all in.

"It's been a long day for both of us," I agreed. "I'll turn in now, too."

Lynn started upstairs and told me to turn out the lights in the living room. I did so, happily, realizing that although our battle was not yet done, nor won, Lynn was at least willing to carry along for a bit in the status of a friendly enough truce.

I heard Lynn's sharp exclamation of alarm when I was halfway up the stairs. She had reached the bedroom a minute ahead of me.

"Tom!" she cried, then. "Tom!"

I ran up the rest of the stairs and burst into the bedroom to find her staring in horror at the bed. My heart was in my mouth, and I didn't dare think of what I was going to see.

"What's wrong, baby? What's the matter?" I gasped.

"Look at the bed, Tom," she gasped strickenly. "The fools forgot to get sheets. It's made up without sheets and we'll have to sleep between blankets!"

The water left my knees and my heart came back to its normal position in my chest.

"Whew!" I gasped. "You had me worrier for a minute, baby."

Lynn looked at me with dismay.

"But this is terrible, Tom," she wailed.

"We'll just have to make the best of it," I told her. "I can drive into the village first thing in the morning and get enough bedsheets to supply, all of India for a thousand years."

Which was all we could do—make the best of it. And Lynn although she admitted as much, was right back into her stony mood of that afternoon. The spell of Mrs. Spingler's cooking, the pleasant evening of chatter we'd had, everything that had been thawing her out, was a thing of the past again. The truce was off.

I WAS awake long after Lynn's even breathing told me she was off in dreamland. Awake and staring at the ceiling, thinking about the big bad Baggat boys and a number of other things.

Of course, I knew that the double-time beat on my imagination was due merely to the darkened room and the wind sighing through the trees in the moonless night outside. But even so, I gave much consideration to the mysterious rummaging that had been done on my suitcases, and the attic noises that Lynn had heard coming down through the chimney and out the fireplace. Noises that she thought had been made by me. Noises that were made in a room which was, or should have been, deserted.

I went to sleep determining to have a look in the attic the following morning, first thing. Went to sleep as the rain started to patter down against the window pane, and the thunder crackled in the distant hills....

LYNN woke me up. I heard the rain beating monotonously against the window-pane and the guttural growlings of thunder as I blinked away the sleep and stared around the gloomy grayness of the room.

"What time is it?" I demanded.

"Nine o'clock," Lynn said.

"Morning or noon?" I gagged quite unfunnily.

"Look at that storm outside," Lynn groaned.

"I can hear it and imagine what it's like by now," I said. "It was starting off about the time I fell asleep last night. Evidently it's been hard at it ever since."

"The driveway to Kingston Road is a swamp if it's all like the stretch outside the house," Lynn said. "What on earth will Father and Mother and Katherine and Walter do?"

"Get a little wet, I suppose," I said, which turned out to be the very thing I shouldn't have said. Lynn glared at me.

"You wouldn't care," she snapped.

"Of course I would," I said soothingly, hastily. "Only there doesn't seem to be anything I could do about it, does there?"

"Wake up Mrs. Spingler," said Lynn by way of answer to that. "And tell her to make us some breakfast. I'm starved."

A jagged bolt of lightning split the sky at that instant, as thunder crashed.

It made me think of Mrs. Spingler's probable reaction toward anyone with gall enough to rouse her.

"No, thanks," I said. "You wake her. I'll munch soda crackers rather than face that old girl."

Lynn gave me a look that was half vicious lion and half angry wife.

"You craven coward!" she said.

She climbed out of bed and struggled into a quilted housecoat.

"I could starve to death in this Godforsaken forest, for all you care."

"It's not a forest," I began.

A brisk rapping on the door interrupted my protestations.

Before I could yell, "Come in," the door was pushed open and the cause for our quarrel stuck her unlovely face into the room.

"I heard your voices," said Mrs. Spingler, "and I wanted to know if you'd like me to fix breakfast now."

Lynn told her to do so by all means, and that we'd be right down to it. Mrs. Spingler took her head out of the door and closed it. Lynn gave a wordless, contemptuous look that told me exactly what she thought of the craven cowardice that had made me flinch at the thought of asking such an obviously willing cook to make breakfast.

I ignored the glance, but I couldn't help ruminating on the fact that Mrs. Spingler had, indeed, seemed considerably less dour this morning than she had last night. In fact, she'd practically had a merry gleam in her rheumy eye when she'd asked if we wanted breakfast.

I decided the only explanation for her cheerfulness was the storm. It was probably all deeply psychological, and prompted by the fact that storms made normal, happy people miserable and therefore brought cheery good will into the hearts of Salem witches and Mrs. Spinglers.

LYNN and I arrived at the breakfast table in gloomy, mutually appreciated silence.

The breakfast was superb, positively royal. If you can imagine a banquet being held for a breakfast rather than dinner, you'll have some idea of the repast Mrs. Spingler set for us.

Lynn ate ravenously, and I didn't exactly ignore the fare myself. Mrs. Spingler, cheery as a lark, buzzed back and forth from kitchen to dining-room like a May Queen dashing around the pole.

What few words Lynn and I exchanged were sadistically savage.

"You'll have to make several trips into town, today," Lynn reminded me. "Through the storm."

"Why several?" I asked innocently enough. "I can pick up everything in one trip."

"There'll probably be something I'll forget," Lynn said. And from the way she said it, I knew that the statement was a promise and a threat.

"I'll wait until you remember what you're planning to forget," I said, trying to ease the strain.

"Bedsheets," said Lynn, "will be necessary for each of the bedrooms. Four pairs of sheets for each. Sleeping beneath those scratchy blankets last night was one of the most loathsome experiences I have ever had."

"Mrs. Spingler's room was also minus sheets," I said. "She doesn't seem to have minded it a bit."

"She'd undoubtedly prefer a good stiff haircloth sleeping bag," Lynn said, "placed on a plank."

Lynn was in a lovely mood. She was hating everybody. I tried to change the topic to someone she couldn't hate.

"The storm might delay your family a few hours," I said. "Particularly if the roads flood over."

"You'd like that, wouldn't you?"

Lynn snapped.

"Now, listen...." I began.

Lynn cut me off, her voice growing more angry with each word.

"Oh, yes you would. You'd relish that; Thomas Kelvin. You'd sit there warm and dry in front of the fire and rub your hands over it. I know you would. I can tell just the way you made that crack!"

"My God!" I protested, forgetting my placating role momentarily. "I didn't make anything like a crack. All I said was—"

"I heard what you said," Lynn cried, rising indignantly from the table. "Don't try to turn the words around to get out of it. And the smirk you had on your face when you made that crack was worse than the crack itself!"

I sighed, and picked at some sausage with my fork.

"It couldn't have been," I told her. "It just couldn't have been worse than my saying that I hoped your entire family was caught in a road flood and drowned like pack rats."

Lynn reached for the left-over pancakes on the platter before I had wind of her intention. They caught me flush on the side of my unshaven chin, and a thin trickle of syrup rolled down my neck as she stamped out of the dining-room and upstairs.

Mrs. Spingler appeared at the door between kitchen and dining-room a split second later. She was beaming.

"It's quite a storm we're having, Mr. Kelvin, isn't it?"

I picked the remains of Lynn's missile from my face and stood up with as much dignity as I could muster.

"Mrs. Spingler," I said with acid politeness, "may I call you Martha?"

LYNN kept to her room for an hour or so, while I panthered around the living room and listened to the storm play hell with the radio reception.

It was almost eleven o'clock when Lynn came downstairs. The expression she wore was the one she'd use on a ticket-taker in a depot—cold, impersonal, and utterly emotionless.

"Isn't it about time you started for the village?" she asked. "I would prefer to have everything in order when my family arrives."

The tone she used implied that she'd like to have everything in order as much as it could possibly be so in such a hole and under such exceedingly trying circumstances.

I sighed inwardly, and pushed a few remarks I'd been rehearsing off my tongue. It was going to be more important to placate Lynn while her family was present than at any other time in the battle. To get her too sore while they were around would just be playing into their hands, and I was determined not to do that.

Swallowing my pride wasn't too hard, when I made a mental check to pay Lynn back later for those pancakes.

"Okay, baby," I said. "I'll run upstairs and shave and get into an un-pressed suit. I'll be into the village and back in plenty of time before they arrive. You got a list of what you want?"

Lynn handed me a list, and I stuffed it into the pocket of my bathrobe, essayed a forgiving we'll-be-friends smile, and started upstairs.

I was in the process of changing clothes when I remembered my resolve of the previous night to have a look in the attic. In the gloomy light of morning it didn't seem nearly so important.

"What the devil," I told myself, "I'll let it go until later in the afternoon. The attic might be a good place to be while Lynn's family is here."

I slipped into a gabardine topcoat and stuck my hand into the pocket wondering if I'd left the keys to the car there. The keys were there, plus a folded sheet of coarse paper.

Examination of the folded paper showed it to be the sort that butchers use, or used to use, to wrap up meats. Brown and, as I said before, thick and coarse.

Thinking it might be a receipt I picked up unthinkingly in Chatam's general store, I unfolded it casually.

It wasn't a receipt. It was a note.

The note was written in a loose, scrawling, childish hand, with a thick, smeary black substance that seemed to be charcoal. It was brief and to the point:

This is noe plase fer a stranger.

This is yewre ferst warning.

Take heed uv it.

It was unsigned.

I reread the note several times, jaw foolishly agape. And then I thought of the messed-up luggage and the noises in the attic and realized I had now another incident to ponder.

I stuffed the note back into my pocket and went downstairs. Lynn wasn't in the living room, and I heard her talking to Mrs. Spingler out in the kitchen.

When I went out there, Mrs. Spingler smiled in what she probably believed to be bright domestic cheeriness and handed me a small piece of paper.

"The missus says she wants turkey at dinner tonight," said the cook. "And I made out a list of some of the things I've planned to have with it."

I took the list and glanced at it with more than idle curiosity. Mrs. Spingler had written it in a fine, precise, school-marmish hand. There was nothing loose or scrawly or illiterate about it, and the amateur Sherlock in me was convinced that she hadn't written the message I'd found in my pocket.

"Don't forget anything," Lynn said.

I promised I wouldn't, and wondered if she had. Then I left by the back way, through the kitchen, and went around to the garage, slogging through mud and merciless rain.

After five minutes spent in cursing the awkward mechanism necessary to endure in order to put the top of the convertible up, I was under way.

THE gravel roadway leading to Kingston Road was heavily flooded, but I managed to get through it without portaging the roadster across the streams on my back.

The Kingston Road proved equally damp but considerably less difficult, and I was able to make Chatam in the somewhat snailish time of forty minutes.

I picked up the stuff on the lists given me by Lynn and Mrs. Spingler without too much difficulty, and, thoroughly soaked, climbed back behind the wheel almost an hour later and started back for the place.

The rain had now settled down to a sloshing monotony minus the previous thunder and lightning, and there didn't seem to be any indication that it would clear up for some time.

There was more water going back than coming, of course, and the driving was even a little tougher than before. It was a matter of forty-five minutes before I finally turned off onto the flooded gravel roadway leading to our place.

I managed to cover several hundred yards before I ran into trouble at the first turn. The trouble was in the form of a washout which had turned the roadway at that point into a three-foot-deep stream.

Maybe I made my mistake in gunning the motor and trying to smash straight through it. At any rate, the points in the motor must have gotten a thorough soaking as I splashed head-on into it, for the motor coughed and stopped right in the middle of the washout.

I sat there motionless, throwing together a dictionary of improper names as I stared through the windshield into the downpour and wondered what in the hell I was going to do.

Futilely, a few moments later, I tried to start the motor again. It wasn't having any, thank you, and didn't even bother to cough apologetically.

I looked through the side windows and ascertained that I was squarely in the middle of a miniature lake. Getting out would be like stepping into a children's wading pool.

Then I thought of the stuff I had piled up in the back. It wasn't so much that I couldn't carry it the additional mile up to the house in one load, but at the same time, it wasn't the sort of stuff, for the most part, that could be safely lugged one mile through a deluge of rain and mud.

I looked at the clock on the dashboard.

It was twenty minutes after one.

"Lynn's family is probably already entrenched in the living room," I muttered, "warming themselves in the snug dry comfort of the fireplace."

I pushed that pleasant probability from my mind, since it served only to make me more dismal than warranted even by my present-plight.

I found a slightly dampened cigarette and lighted it with the third soggy match from a pack in my pocket. I was smoking resignedly and staring dourly at nothing when I suddenly remembered the big tarpaulin in the rumble seat.

That was a solution.

I could get out the tarp, bring it around to the front and pile practically all the packages into it, using it like a huge knapsack. Carrying it that way, like a grotesque Santa with an enormous sack, I could get the stuff up to the house without any of it suffering from the elements.

I was especially pleased with my resourcefulness, even when I opened the door and stepped out of the car into three feet of cold rain water.

THE scheme proved practicable, and inside of another ten minutes I was drenched to the skin, but had managed to collect all the packages into the tarpaulin and sling the load over my shoulder.

I left the car in the center of the washed-out roadway and started for the house. The rain was still pouring buckets, and the footing underneath made me think of swampland and quicksand, but it really didn't matter. I was as soaked as any human being could be before I'd even started.

It took me about fifteen minutes to get to the house, and when Lynn opened the front door to see my bedraggled, bemudded and besoaked condition she almost fainted.

"Tom," she gasped. "What's happened, Tom? Did you have an accident? Have you been hurt?"