RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

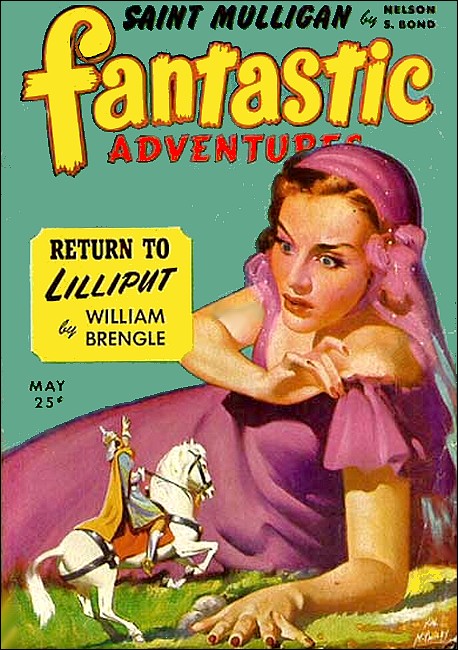

Fantastic Adventures, May 1943, with "The Curious Coat"

Louie the grifter slipped this guy a mickey so he could steal

his coat. How could he know he was an agent from heaven?

WHEN Louie the grifter entered the Plaza bar that evening, his primary motivation was to have a drink, his secondary purpose was to case the joint—just in case there might be some business to pick up.

"Casing" a place, in the jargon of Louie's trade, meant something roughly similar to sizing it up, surveying the lay of the land, or searching for some small, quick, easy and dishonest cash.

So, on this particular night, Louie just happened to be passing by the Plaza bar when he decided to step in and have a look around. The Plaza bar was a fairly respectable bistro, catering to a somewhat monied middle class trade, but not quite snooty enough to enjoy the privilege of barring people of Louie the grifter's caliber so long as they seemed to have enough to pay for their drinks.

Louie was a small, thin, nervous little man with a face closely resembling a little-known species of the weasel family. His attire, although it was late autumn and growing definitely chilly, consisted of a too sharply cut, pale gray sharkskin suit and a small-brimmed, somewhat soiled fedora of matching color. His tie, a violent red and purple, matched the color of the tiny, drink-broken veins that marked his small, sharp nose. His shoes were yellow, and the toes of them as needle-pointed as his nose.

Louie wore no topcoat—which fact, as you will soon enough perceive, was the start of all the trouble.

Having ignored the disdainful and simultaneously suspicious stare of the doorman presiding at the entrance to the Plaza bar, Louie strolled casually into its soft-lighted, deep-carpeted cocktail lounge and found a stool at the far end of the bar.

In Louie's pockets jingled innumerable nickels which he had just collected from the pay telephone booths of some dozen public places. These nickels, often as many as sixty of them, constituted Louie's daily grub stake in his grifting, and were obtained by the more or less simple process of removing a small plug of paper from the upper passage of the return coin slots in the various telephones he visited each day. Of course these telephones were worked exclusively by Louie, and were each at definite locations known to him. True also was the fact that Louie himself was the sinful person who stuffed the small paper wads up into the upper passages of the telephone return coin slots each day. It would have been difficult to estimate the number of indignant telephone users who, on getting a busy signal or no answer from the number called, lost the nickels which should have been returned to them, thanks to Louie's ingenious paper catch wads.

NOW, as Louie sat at the bar, he contemplatively jingled the nickels in his pocket, while his small, beady black eyes darted back and forth along the bar in shrewd estimate of his chances to pick up a dollar or two in the place.

The bartender came over to Louie, then, and asked, with no noticeable friendliness:

"What'll you have?"

Louie grinned in what he considered to be his most engaging manner. Grinned and revealed small, pointed yellowed teeth which were lavishly interspersed with silver fillings turning black.

"Gimme a beer, pal," Louie said.

The glance the bartender gave Louie showed only too plainly that he had expected anything but a lavish order from the little grifter. He glared at Louie and went away.

The bars tools to the right of Louie, three in number, were vacant. Beyond these a small party of middle-aged business men and their wives took up another six stools. Still further on there were several solitary drinkers, a laughing young couple, and a white haired, dinner-jacketed old man.

Louie had noted all this even before he'd taken a seat at the bar. He had noted, too, that the three seats to the right of him were only temporarily vacant, and that their momentarily absent occupants had left cigarettes, small change, and half finished drinks to indicate that they would be back.

Casually, his darting eyes making certain that no one was watching him, Louie took one of the most nearly filled packages of cigarettes and slipped it unconcernedly into his pocket. Then he waited patiently until the bartender returned with his glass of beer.

"Here y'are, Doc," Louie grinned, shoving two nickels across the bar in exchange for the foam-crested beverage.

"Another nickel," the bartender snapped.

Louie looked hurt, then grinned once more, shrugged expansively, and tossed another nickel after the first two. The bartender picked up the three coins in a manner to suggest he suspected they were contaminated, then walked away.

Louie sipped his beer reflectively. Who in the hell did they think they were in this joint? Fifteen cents for beer! But it was good beer, and Louie eased the pangs of his economic prudence by a swift, stealthy gesture which swept up a quarter from the change lying on the bar to his right.

Pulling forth his purloined package of cigarettes, Louie extracted one from the pack and pushed it into the corner of his mouth. Then, using the matches in the ash tray on the bar, he lighted it with casual nonchalance.

He sat there that way for the next five minutes, puffing reflectively on his cigarette and taking an occasional sip from his beer, while mentally wondering just what the three people who'd deserted the stools to his right were like, and when they'd return.

IT was about this time that the cherubic little man came into the place.

Louie was able to see him enter, from where he sat. And even in his first, sharp, appraising glance, Louie couldn't mistake the little man for what he had obviously been born to be—a sucker.

The little man had a round, apple-ruddy face. His body, dressed unobtrusively in a suit of expensive tailoring and dark tweed, was as proportionately pudgy as his face. He wore a soft, brown fedora, and carried a handsome camel's hair topcoat on his arm.

Louie decided instantly, from the very timidity of the little man's searching glance toward the bar, that cocktail joints were not his ordinary habitat.

It was when the little man's eyes lighted on the three vacant stools to Louie's right, that Louie lifted his hand casually, indicating the one closest to him, and beckoned, with casual barroom camaraderie, to him.

The little man saw Louie's gesture, blinked at the vacant stools, then nodded brightly and smiled. He came over to the bar.

"Siddown, buddy," Louie invited. "The people who's supposed to be attached to these stools has been away too long. They don't hold no leases on them. Take a seat."

The little man looked uncertainly at Louie.

"Oh, are people sitting here?"

"You are, pal," said Louie, pulling out the barstool closest to him.

"I, ah, really don't think I should," the little man stammered apologetically. "I mean, if people are sitting here."

"Don't give it another thought," Louie said. "When they come back they'll hafta find another stool, that's all."

"I don't want to cause anyone any trouble," the little man protested feebly. "I am rather nearsighted, and when you waved to me to indicate these vacant seats, I had no idea that someone might have deserted them temporarily."

Louie put his hand on the little man's arm, practically forcing him to the stool.

"S'awright. Ferget it," he said. The little man, obviously against his better judgment, timidly took the stool beside Louie.

There was a moment of silence, and then the little man cleared his throat nervously.

"You were very kind," he said.

"Think nothing of it," Louie said grandly. "Say, you better put that coat on the hanger over there. Here, lemme take it for you."

The little man, at that moment, had been holding his very rich camel's hair coat on his lap. He seemed startled by Louie's suggestion.

"Ah, I, uh—no. That is, no, thank you. I'd rather not," the little man protested.

"You'll suffacate yerself with that on your lap," Louie declared, grabbing for the coat. "Don't be silly. I'll hang it up for you. The coat rack's right over there, where we can see it and keep an eye on it. You don't hafta worry about its getting stole in this joint."

"It, uh, isn't that so much," the little man protested. "It, uh, is just that this coat means a l—"

LOUIE cut him off, grabbing the coat completely from the little man's grasp. He grinned and slapped the little man on the back.

"Don't worry about nothing," he said cheerfully. "I'll hang this up right now." He got off his barstool, the other's coat in his hands. "And say, while I'm hanging this coat up for you, you can order us a couple drinks on me, huh?"

"Really, sir," the little man said bewilderedly, "I can't permit you to purchase my drink. You've been too kind already. I insist that I treat."

"G'wan," said Louie with great goodheartedness and a resounding slap on the little man's back. "You struck me right off as being a stranger here in town, and I always wanta show strangers how first rate this burg of ours is." He paused, then added, sharply, "You are a stranger here in town, ain't you?"

The little man now looked additionally bewildered.

"Why, ah, yes. Yes I am. Yes, you might very well call me a stranger here in town," he spluttered.

"Fine!" Louie the grifter exclaimed enthusiastically. "That's just fine!"

Louie was feeling considerably pleased with the prospects for this evening when he walked over to hang the little man's topcoat on the coat rack in the corner. This looked like more than a little bit of an easy roll.

After carefully hanging the little man's topcoat so that it was out of sight of their places at the bar, Louie returned to his unwitting victim.

He found the little man talking to the bartender.

"Ah, there, palsie," Louie beamed, "how about that drink on me?"

The look which the bartender flashed at Louie was most definitely hostile and suspicious. But Louie ignored him.

"What're you drinking, palsie?" he asked the little man.

"I had thought that a glass of beer—" began the little fellow.

"A beer for the gent," said the grifter, cutting him off. "And you might make that a shot of the twenty year old Scotch for me."

The bartender's suspicion was now pronounced. He looked from Louie to the little man, started to say something, closed his mouth and went off for the drinks.

The little man picked up the thread of a previous theme. Pleadingly, he addressed Louie the grifter.

"I wish, sir, that you would let me stand treat on this drink that is coming. It is only fair. You have been so kind that—"

Louie cut him off with an expansive wave of his hand and an elaborate shrug of his shoulders.

"Okay, palsie," Louie said resignedly. "If you insist, the treat'll be on you."

The little man beamed his thanks with his eyes, and at that instant the bartender appeared with the drinks—beer for the little man and a bottle of twenty-year-old Scotch and a shot glass for the grifter.

"My friend," smiled the little man, "has consented to permit me to treat for this drink."

"If you think that comes as a surprise," said the bartender coldly, "you're wrong."

LOUIE raised his eyebrows in lofty disdain at that remark, ceremoniously pouring himself a shot of the twenty-year-old Scotch. He raised his glass to the little man.

"Regahds," said Louie.

The little man had been fumbling for his wallet. Now he put it hastily on the bar and lifted his glass of beer.

"To your good health, sir," he answered.

In silence, the grifter downed the shot and the little man sipped his beer. Then, putting his glass on the bar and picking up his wallet again, the little man began a probe for a bill. Louie, while appearing utterly disinterested, furtively cased the wallet. To his trained eye it seemed as though there wasn't much more than twenty dollars in the wallet.

Louie felt a sharp twinge of disappointment. He'd expected to find the little sucker packing a big wad. But twenty bucks was twenty bucks, and such easy money didn't hang around under a grifter's nose every day.

Quickly, as the little guy shoved a five dollar bill across the bar, Louie sorted through his mind for an excuse to get his sucker out of the Plaza bar and to some disreputable bar where he could slip a powder in the foam of his beer.

It was as the bartender walked away to make the change for the five dollar bill that Louie brought forth his suggestion.

"Say," he said with impulsive gaiety, "this place stinks."

The little man looked properly stunned. He sniffed several times bewilderedly.

"I—I am afraid that I do not quite understand you, sir," he confessed.

Louie elaborated.

"This joint has no life," he said. "A guy could curl up onna bar and doze off, it's so dead."

The little man looked around. "I hadn't noticed," he admitted. "I thought it seemed rather festive."

"Hah!" Louie came in with his clinching sales talk. "That's just because you're a stranger in this town, palsie. This town has joints that make this place seem like a rest ward inna sanitarium. Whatcha say we blow this place and I'll show you some of them places?"

The little man looked properly regretful. He shook his head sadly but firmly.

"I appreciate your efforts to be kind, sir," he said. "But I cannot—indeed, dare not—imbibe more than this glass of beer tonight. I confess, I sort of sneaked in here for just one glass of beer when I really should have been about my business. No, I'm afraid I must regretfully refuse your very kind invitation."

Louie hadn't expected this. The sucker had given the wrong answer. But he had still an ace up his sleeve. He leaned forward and whispered in the little man's ear.

The little man crimsoned to the roots of his hair. He seemed suddenly painfully embarrassed. Louie sniggered and nudged him in the ribs with his thumb.

"How does that sound to you, palsie?" Louie leered.

"I, uh, Dr, that is—" the little man floundered.

"Knockout lookers, they are," Louie cut in.

The little man had finally gained enough composure to answer.

"I am very sorry," he said a trifle stiffly, "but such pursuits of sinful pleasure would not interest me."

LOUIE'S jaw fell agape. Momentarily, he was left without a comeback. This little guy was all of a sudden giving out with nothing but wrong answers. Louie forced a mechanical, good-natured grin to his weasel-like face.

"I didn't mean no offense, chum," Louie began swiftly. "It's every man to his own likes, I allus say."

But the little man was getting down from the barstool even as Louie spoke.

"Hey," Louie exclaimed. "You ain't leaving?"

The little man shook his head. "Not until I have finished my beer," he said, pointing to the almost full glass still on the bar. "It is just that I find it suddenly expedient to—" and he leaned forward and whispered in Louie's ear.

"Oh," Louie was relieved. "You'll find it straight ahead and around the first corner to the right."

The little man nodded gratefully. "Thank you, sir," he said. He moved off rapidly on the course Louie had charted for him.

It was then that the bartender, seeing the temporary leave-taking of the little man, came quickly over to where Louie sat.

"Okay, pal," said the bartender. "You ain't fooling anybody. Shove off."

Louie's jaw fell agape indignantly. "Huh?"

"You heard me," said the bartender. "You're a mooch and a cheap grifter. We don't want guys like you cluttering up this place. Skate outta here before I call the bounce man."

Louie stared angrily at the bartender for a moment. Mechanically, he picked up the change left on the bar from the little man's bill. As he did so, he held the bartender's glance with his own, so that the adroit maneuver passed utterly unnoticed.

"If you're taking that attitoot," said Louie loftily, "I shall take my business elsewhere." He pocketed the little man's change, three bills and some silver.

"Don't dally, bum," said the bartender.

Slowly, to indicate that he wasn't going to rush for anyone, Louie climbed off his barstool. From the corner of his mouth there slipped an entirely indecent rejoinder.

Then, as the bartender purpled in rage, Louie walked slowly, with insulting leisure, toward the exit, carefully picking his way past tables and booths so that the coatrack on which he had hung the little man's topcoat was easily accessible.

It was a simple matter to reach out with one hand and sweep the obviously expensive camel's hair coat from the rack and curl it under one arm while he passed by. And Louie knew that, from where the wrathful bartender watched, the theft could not be seen. Nor did it cause any attention from the tables and booths of guests near the coat rack. After all, hadn't they seen Louie hang the coat up in the first place?

ONCE outside the Plaza bar, Louie started rapidly along the street until he had put several blocks between himself and the scene of his operations. Only then did the grifter slow down to take stock.

In the fifteen or twenty minutes Louie had spent in the Plaza bar he had accumulated one package of free smokes, two-bits change left by temporarily absent guests, one shot of twenty-year-old Scotch, three dollars and ninety-five cents change left from the five dollar bill of the little man, and one obviously valuable topcoat which had been the property of the little man. Against this profit he mentally wrote off the fifteen cents operating expenses of the beer he'd had to buy.

On the whole, Louie felt more than satisfied. Of course, he'd counted at first on getting the little guy out of there and taking him to a dive where he could slip him a Mickey, then to an alley where he could roll him for his wallet. But still, the grift he had accomplished was pretty fair compensation for the alteration the sharp-eyed bartender had put in his plans.

"Not so bad," Louie mused. "Not so bad at all."

Louie now began a careful inspection of the purloined topcoat. He did this leisurely, and with practiced skill. Though he found no label on the inside of the coat to indicate where it had been purchased, Louie was still aware that it was a valuable garment. He estimated that it must have set the little guy back several hundred bucks when he purchased it, which couldn't have been long ago.

Mentally, Louie went through percentage arithmetic, arriving at the figure that Arthur, the fence for stolen goods, would pay him the following day for the garment. Twenty dollars, anyway, twenty-five, if Louie held back.

The tallying of this neat profit to his operations in the Plaza bar gave Louie a warm, happy feeling. Even if he'd rolled the little guy as he had planned, he couldn't have cleared more than sixteen, eighteen bucks on it. But of course, had he given the little guy a Mickey and rolled him, he could have taken the coat too.

Louie shrugged this off, however, with a philosophical observation.

"What the hell?" he told himself. "It don't pay to be too greedy."

Continuing his inspection of the topcoat, Louie discovered nothing more save a small, neatly printed card which contained merely one name.

"Mr. J. Joy," was the name on the card.

Louie looked the card over carefully a minute, memorized the name, then tore it into tiny fragments and let them flutter to the sidewalk.

"J. Joy, eh?" Louie mused contemplatively. "Probably the little guy's name. What a monicker! Wonder how he came by such a handle?"

Louie sighed and gave up trying to figure out how anyone could come by such a handle. He turned his attention back to thoughts of business, and a craftsman-like enthusiasm flooded him. This looked like the start of a big night, a very big night. When Louie had especially good nights, they generally started off right, like this one.

FOR a moment Louie debated on a choice of his next stopping place. There were more bars similar to the Plaza in this neck of the woods, but his instinct told him that it might be wise to lay off such bistros for a bit and concentrate on the sucker trade in the cheap, frowsy clip-joint belt just three blocks east of this neighborhood. There, in the precincts of innumerable small-fry "night spots," reeking, firetrap saloons boasting dollar minimum charges and entertainment loosely labeled "floor shows," Louie could vie with the proprietors of these establishments in clipping customers who thought themselves slumming.

Louie had long had a fondness for such places. Suckers with dough who patronized them were generally in a psychological spot when they were clipped, no matter how brutally, inasmuch as any protest on their part might result in nasty police-to-newspaper messes which would reveal to their friends and neighbors that they'd descended to the depths of such dives for entertainment.

One sucker who didn't dare squawk, in Louie's book of trade homilies, was worth a hundred who turned into cop-hollerers.

It occurred to Louie, as he started off toward this cheap night life district, that he could even afford the well earned luxury of relaxing for a half hour or so in one of those places before getting back to business. What the hell, he thought virtuously, I've worked hard and deserve a breather. Besides, the night was starting off three lengths ahead of the field....

THUS it was that Louie the grifter found himself in one of his favorite clip-belt "night spots" some ten minutes later, seated at a corner table with a bottle of beer in front of him while he watched the unclad writhings of a hennaed, hoarse-voiced damsel strutting and stripping back and forth across the postage-stamp clearance before an elevated bandstand.

Louie's spindle legs were thrust forward from his chair in an attitude of delicious relaxation, and his beady eyes followed the contortions of the dumpy danseuse appreciatively, while his left hand drummed rhythmic accompaniment to the hideous cacophony emitted by an off-key but enthusiastic four-piece orchestra.

This, to Louie, was the spice of life. It could be said truthfully of him that, were he to inherit a million dollars within the next ten minutes, he would use it merely to further his prestige in circles such as this. In his enjoyment of the finer vices, Louie was pathetically limited by his imagination.

Nevertheless, so long as it didn't seem that he stood any chance of inheriting a million dollars, Louie's conscience would allow for only just so much of this wasteful relaxation. He'd been in the cheap night spot little longer than twenty minutes when his conscience began needling him at his idleness, and his darting, beady little eyes went back to work.

There was a party of slummers at a table some ten feet away from Louie's. Two boisterously drunk, middle-aged business men, and two bleached damsels who looked neither like their secretaries nor their wives.

There was a gaiety and hilarity and friendliness in the attitude of the two middle-aged businessmen that suggested possibilities to Louie. And too, they purchased drinks for their table with lavish indifference to the outrageous prices which had undoubtedly been especially established for their benefit by the clip-conscious management.

Louie sat there a while, indexing through his mind to find a grift which would be suitable to the occasion.

He thought of the "Pardon me, pal, but ain't you from Kansas City?" opening, and discarded it, inasmuch as the two prospective victims didn't seem to be strangers to the town.

He gave careful thought to numerous other approaches, discarding each for one reason or another. The briefly entertained idea of buying them a round of drinks with his compliments, he shudderingly eliminated at the realization that the management was probably doubling the check on the suckers, and that they were all drinking hard liquor.

At length, however, he selected his opening and, satisfied that it was the best, rose from his table and went to the washroom. There he killed a few moments, permitted himself to have his shoes and clothes brushed by the attendant, and, with exceptional largesse, tipped the chap a nickel.

On coming from the washroom, of course, Louie had to pass the table of his prospective victims to get to his own. And in passing that table he managed to stumble into the back of the chair in which one of the middle-aged businessmen sat.

Profuse in his apologies, Louie clapped that gentleman heartily on the back as a gesture of fraternal acknowledgement that there would be no hard feelings on either side, and started again toward his table.

THEN, two strides away from their table, he stopped sharply, and with an exclamation, turned back to the gentleman whose chair he had jarred and whose back he had slapped.

"Say," Louie exclaimed in excited discovery, "ain't you George Spelvin?"

The gentleman at whom Louie had pointed his finger looked surprised. Then he shook his head and admitted that he was not George Spelvin.

Louie peered long and hard at him, as if searching his memory, then shook his head sadly.

"No," Louie said, "I guess you ain't. Awful sorry, pal, but you certainly are a ringer for George Spelvin. Why, say, you could easy be his twin, you look that much like him. He was big, a powerful guy, and distinguished looking like you," Louie added, with an obvious vanity bait.

"Ish zat so?" said the businessman, enormously pleased. He looked proudly at the bleached blonde beside him. "Hear that, baby? Thish fella saysh I look lie a guy he ushta know."

The other businessman broke in, then, cordially effusive.

"Have a drink wish ush, fella? Gotta have a drink on sush a conishdunce! Pulluppa chair."

"Shure thing," said the first by way of seconding an excellent spur-of-the-moment comradeship. "Pulluppa chair!"

Louie exposed his unlovely dental work in a delighted grin. He reached for a chair at a vacant table to his right. It was then that one of the bleached damsels entered the conversation. She was closest of the four to Louie, and she spoke in a voice clear enough to carry to the little grifter's ears without being heard by the others.

"Ixnay, umbay," she hissed through a red smile. "You poach on our territory and I'll scratch bloody holes in the place your eye sockets usta be!"

Louie suddenly paled. He hadn't foreseen this. He wondered how his intentions had been so crystal clear to the blonde, then realized that grifting—though of a slightly different sort—was her line also.

He smiled a sick, mechanical smile, while his darting eyes flicked to the other blonde and perceived that she unquestionably shared her sister-in-clip's sentiments on the matter of poaching.

"Heh-heh," Louie grunted weakly, "I'd like to, fellas, but I gotta be finishing my beer back at my table, then getting on. Thanks just the same."

He went quickly back to his own table, then, the protests of the two businessmen dying in the sudden bright chatter of their blonde companions.

Sullenly, Louie sat down before his half-finished bottle of beer and mentally wrote off a total loss of a nickel spent in the washroom on the strength of that mismanaged deal.

He was thus moodily embittered when he saw the little guy walk into the place.

The same little guy, the one named J. Joy, whose topcoat was at the moment hanging on a hook above Louie's wall table.

INSTINCTIVELY, Louie started to rise from his chair, eyes searching for the nearest exit, one hand ready to grab the topcoat for his flight.

And then Louie perceived that little Mr. J. Joy was quite alone. The big, blue uniformed figure which Louie had confidently expected to see in the wake of little Mr. Joy was not there. Louie was flooded with sudden relief at the thought that the little guy had not hollered copper.

Little Mr. Joy stood blinking nearsightedly beside the bar near the front door, peering at the customers who lined it, and then at the tables around the dance floor in the rear.

Louie hesitated uncertainly, suspiciously. How had the little guy figured he'd be here? And what in the name of hell did the little guy figure it would get him to go searching for Louie alone and without the help of a copper?

Louie's little pig eyes flashed again to the wake of little Mr. Joy, but there was no copper present. Not even a guy who looked like a flattie from the plainclothes detail.

Now little Mr. Joy was moving slowly in his direction. Louie saw a waiter advance to him and ask him a question. The little man shook his head embarrassedly and gave an answer that must have had something in it about looking for someone.

The waiter stepped back to let little Mr. Joy pass, but kept an eagle eye on him as the little man advanced timidly nearer to the section where Louie waited watchfully.

The fact of the little man's aloneness, and therefore helplessness, had now been accepted by Louie, and the thought amused him considerably. He made a sudden decision, and resumed his seat, eyes still on the advancing Mr. Joy.

Then the little man spied him, and an expression more of ecstatic relief than of anger crossed his pudgy, cherubic features. He hurried over toward Louie's table, breathlessly excited.

Calmly, Louie regarded the little man's approach until at last Mr. Joy stood directly before him, puffing heavily as he sought for words.

"What you want?" Louie asked belligerently.

Little Mr. Joy caught his breath at last.

"Oh my, you don't know how relieved I am to have found you, sir. I have looked in almost every drinking place in a radius of five blocks from the Plaza bar."

So that was how the little guy had found him? It had just been a matter of luck. Louie felt even more belligerently confident.

"Okay," he said harshly. "So now you caught up with me. What you want, huh?"

"My topcoat," said the little man. "I must ask you to give back my topcoat. When I'd found that it was missing from the coat rack where you'd placed it, some people at a table nearby told me that a person of your description had walked out with it. I am sure you made a mistake, sir, and intended to take your own coat, but took mine instead. If you will return to the Plaza bar you will undoubtedly find your own hanging there."

LOUIE stared at the little man incredulously. Was it possible that it had never entered the little mugg's noodle that someone would heist his topcoat? Louie found it hard to believe. And yet, there was an expression of utter guilelessness in the little man's eyes that belied the possibility of any other explanation. Then, too, such naivete fitted perfectly into the explanation of the little guy's appearance without a copper.

Lighting a cigarette to hide the grin he couldn't repress, Louie made a quick decision as to how he would handle this little jerk. He waved to a chair on the other side of the table.

"Siddown, palsie," he invited.

Little Mr. Joy started to sit down, then midway in the process, paused to ask excitedly:

"Then you do have my coat? You were the one who took it by mistake?"

Louie jerked his thumb upward to indicate the coat hanging on the wall peg above their table.

"There it is, palsie," he said.

The little man dropped into the chair with a sigh of relief at the sight of his topcoat.

"Thank goodness," he gasped. "Oh, thank goodness!" The grateful glance he bestowed on Louie the grifter was brimming with joyous tears.

"Does the benny mean that much to you?" Louie asked.

"What?" the little man blinked.

"The body-wrap, the topcoat, does it mean that much to you?" Louie amplified.

"Oh, my!" the little man exclaimed. "Oh, my, you have no idea how much it means to me, sir. If I were to tell you, I—" and quite suddenly little Mr. Joy clapped his hand over his mouth, cutting off the rest of his sentence. He gave Louie a look of dismay.

"Whatsa matter?" the grifter demanded.

"I'm sorry, sir," said little Mr. Joy. "I almost disclosed information which would be most indiscreet to reveal."

Louie frowned suspiciously at this.

"Information such as what?" he asked sharply.

"About the topcoat," blurted Mr. Joy, and then, again, clamped his pudgy little hand across his mouth in a gesture of dismay. "Oh, my," he gasped. "In my excitement I have quite lost control of my tongue, I'm afraid."

Louie felt a sudden surge of irritation toward the little man's secretiveness. Something was rotten about that topcoat somehow, that much he now sensed. But what? What could the little jerk be blabbing about?

Suddenly the frown left Louie's brow and a Cheshire smirk twisted the corners of his small, thin-lipped mouth. He had a pretty good idea of what was up. He had a damned good hunch about that topcoat, now. A hunch that told him maybe there was some dough, heavy sugar, sewed up in the lining of the garment. Louie had known people to hide their money that way before. Once he'd heisted the coat of an old scrubwoman in a restaurant and found three hundred bucks that must have been her life's savings sewed in the lining.

And now that Louie felt pretty certain of his knowledge, he sat back and eyed little Mr. Joy with the appraisal of a feline toward a mouse.

THIS was perfect. This was the realization of his hunch that this would be a banner night for Louie the grifter. Little Mr. Joy didn't look like the kind of a squirrel who'd hide peanuts in the lining of that coat. If there were dough in there, and Louie now felt certain there was, it would be in big bills. Nice chunks of folding money. Maybe as much as a grand, or better.

Louie beckoned to a waiter, who hurried over to the table.

"A bottle of beer for this gent," he ordered, "and a double slug of Scotch for me."

Mr. Joy, as the waiter left, opened his mouth as if to protest, but Louie cut him off.

"You can have a drink on me, palsie," he said, "before you take your coat and leave. I feel I've putcha to a lotta trouble, and I wanta make up for it, see?"

Mr. Joy smiled apologetically. "Your attitude has been consistently kind and gentlemanly, sir. I don't know how I can ever repay you."

"Skip it," said Louie modestly. "But if you wanta do me a favor you can explain why you is so attached to that benny, I mean topcoat, of yours. You didn't look like no guy who lost an ordinary topcoat when you come busting into here."

The little man looked indecisive. He bit his underlip worriedly. There was fully a minute of silence. Louie waited, cat-like, to see what phony yarn the little guy would cook up to explain the extra value of the coat.

In the interval, the waiter came to the table with a bottle of beer for Mr. Joy and a double Scotch for Louie. He set the glasses before them and left.

"Well?" Louie demanded. "Doncha wanta tell me?"

Little Mr. Joy took a deep breath, then exhaled it in an explosive burst of confidence.

"It is against all the rules, sir. But under the circumstances, I think I can disregard instructions this once. I shall tell you, sir. Yes, I shall."

Louie hid a smirk behind a clawlike hand, his beady eyes cynically mirroring the deceit he was confident was coming. Then he stretched the smirk into a between-the-two-of-us grin which he displayed to Mr. Joy.

"Shoot, palsie," said Louie.

Little Mr. Joy, after one last moment of indecision, began. He talked quickly, earnestly, in a low, conspiratorial tone.

"Remember, sir," said little Mr. Joy, "when you remarked that I seemed to be a stranger here in town?" He didn't wait for the answer to this question but continued rapidly. "Remember, too, my saying that I was rather a stranger? Well, sir, your remark was far more significant than you suspected. I am not only a stranger to this town, sir, but I am also what you might call a stranger to this world." He paused dramatically, eyes searching Louie's face eagerly to see if the proper implications of that statement had registered on his auditor.

Louie the grifter met Mr. Joy's gaze with a hard, impassive stare. Though the little man did not perceive it in Louie's face, the grifter was doing an excellent job of concealing a two-fold reaction to Mr. Joy's incredible statement. Louie's first thought had been: "Is this little jerk nuts?" and his second: "Or is he sap enough to think I'm nuts?"

"Did you clearly understand the implications of my statement, sir?" Mr. Joy asked anxiously.

LOUIE had by this time come to the conclusion that he had been somewhat correct in both of his first reactions. The little jerk was probably a trifle off his trolley, and probably nuts enough to imagine Louie was nuts also.

"Sure," said Louie impassively. "I got the drift. Go right ahead. Tell me more." Louie had by now decided that if the little guy was batty it made it even more certain that there was a wad of dough sewed up in his topcoat's lining. Screwy-blooies hid their money that way.

"Good," said Mr. Joy. "I was afraid you might be skeptical. There are few humans who aren't." He took another deep breath and went on. "You see, sir, I do not belong to this world. I am an insignificant member of the world beyond this world. I am, in fact, a Heavenly Employee."

"Is that right?" Louie said tonelessly.

Little Mr. Joy nodded eagerly. "Precisely, sir. I am a Heavenly Employee, one of an incredible number of Heavenly Employees who carry out innumerable jobs There and on earth, here."

"That's very interesting," observed Louie the grifter.

Again little Mr. Joy nodded eagerly, face aglow. "Yes, indeed, it certainly is. As a Heavenly Employee, furthermore, I am one of a number of Special Agents assigned to various territories in this world of yours. My territory includes this state and four adjacent states."

Louie the grifter was still managing to keep a poker face.

"It must keep you pretty busy, huh?" he asked.

"Oh, yes, it does," agreed the little man. "You see my job as Special Agent in this territory, as my name indicates, is the spreading of joy where there is unhappiness and tears."

"Well, well," said Louie, "ain't that a nice job, though!"

Little Mr. Joy beamed. "Oh, my yes. It surely is. There are many other Special Agents in other territories who do the same work as I do, and none of us would trade jobs with agents on other assignments for a minute. Well, to continue, you now understand where I am from and what my job consists of, you can no doubt understand also why it was necessary for me and other Special Heavenly Agents working in this world to assume human form."

"Sure," said Louie solemnly. "Sure. So you could look just like the rest of us humans, huh?"

"That's it!" exclaimed little Mr. Joy delightedly. "Otherwise our appearances would be much too conspicuous to be practical for our work. We would, I am sure, cause far too much alarm to enable us to do our work quietly and efficiently. Do you follow me so far?"

"Sure," Louie assured him. "I'm way ahead of you. You don't seem no different from any other human beans on account of you don't want to seem different. But what about the ben—, I mean, topcoat?"

"I was just coming to that," said the little man eagerly. "You see, we work an eight hour day when we're here on earth. There are two other agents in this territory who do the same work as I do. Each takes one of the other two shifts so that there is always an agent on duty, every hour of the day and night."

"That's good," said Louie. "I was worried there for a minute."

"Oh, yes," said Mr. Joy. "One of us is always on the job. But there's the catch."

Louie blinked. "The catch?"

"Yes, don't you see? When we are on the job our work is of such a nature that we cannot afford, under any circumstances to be seen by the humans among whom we move. The human bodies we wear of necessity during the sixteen hours when we are not working, are flesh and blood, and therefore visible. Being visible during our working hours just wouldn't do," the little man declared emphatically.

"Yeah," said Louie impatiently, "I can see you gotta tough problem there. But where does the topcoat come in?"

"The topcoat," exclaimed Mr. Joy happily, "is our solution to the problem. Each of us was issued a special topcoat, such as mine there hanging on the wall. During our working hours, when it is necessary to be invisible, we merely don the topcoat over our necessary human bodies and, presto—no one can see us!"

LOUIE the grifter stared contemptuously a full minute at the eager little man. This clinched it. This was final proof that the little jerk was nuttier than a package of pecans.

"Well, well," Louie remarked at last. "Ain't that somepin!"

"Yes, isn't it clever?" little Mr. Joy said proudly. "Then, when our working shift is through, we merely remove the coat and become visible again."

"So that's why you was so anxious to find your topcoat, eh?" concluded Louie with thinly disguised contempt.

"Exactly, sir," said the little man. "Now you can understand my anxiety. You see, I might have borrowed a coat from one of the agents on the two other shifts in this territory, except that it would have been a poor fit. You see, they were given bodies of a size different from mine."

Now that the little man had thoroughly presented the proof of his insanity, Louie was impatient to get rid of him and get at the lining of that coat. Louie was certain even more than before that the nitwit had at least a couple of grand in a private booby bank beneath the lining. The thought made his fingers itch.

"That was plenty interesting, palsie," Louie said suddenly. "And you can be sure I won't blab a word about it to nobody else. I'll keep every word of it on the confidential."

"I hope you will, sir," said the little man. "Except for the unusual circumstances I would never have told you. If you were to spread what I have disclosed, it would do untold harm to our work. We can't have that happen."

"No," said Louie, reaching for Mr. Joy's glass and unpoured bottle of beer, "you can't have nothing like that happen to ruin your racket. Here, you ain't even tasted your drink. I'll pour it for you, and we'll have a drink together on the lucky fact you found your topcoat again."

As Louie the grifter poured Mr. Joy's beer from the bottle into the glass, he dexterously emptied the knockout powder from the small paper he'd concealed in his palm. The powder rested easily and unnoticeably in the collar of foam at the top of the glass.

Louie handed the glass to little Mr. Joy.

"Here y'are, palsie," he said, raising his Scotch in a toast. "Here's to the good luck we both got tonight, huh?" Louie fought back a smirk at what he considered to be an exquisitely ironic salutation.

"Yes indeed, sir," said little Mr. Joy, raising his glass aloft. "Here's to your health!"

Louie held his glass half an inch from his mouth, looking steadily at the little man as he took a short, quick draught from his glass of beer.

A WRY expression of distaste came to Mr. Joy's cherubic features, and he seemed momentarily about to gag on the liquid he swallowed. He planked his glass down on the table quickly, coughing, his face growing green, then ashen.

Strickenly, Mr. Joy looked up into the smirking face of Louie the grifter.

"Whatsa matter, palsie? Don't you feel good?" Louie said mockingly.

Mr. Joy's eyes were suddenly heavy lidded. There was a white ring around his mouth, and he groaned feebly.

Louie the grifter laughed harshly. And then Mr. Joy put his head in his arms and his arms on the table. His faint groans came muffledly to the grifter.

Pushing back his chair from the table, Louie rose and went around to where the little man sat. Before trying to lift Mr. Joy's head from his arms, Louie located the little man's wallet. He pocketed this, then, and grabbed the little man by the hair, jerking his head up so that he could see his face.

Mr. Joy was still conscious, though very foggily so, and quite desperately in the throes of nausea. His complexion was a soupy, pea green.

Louie laughed, turned and waved to a passing waiter. The waiter hurried over to the table.

"Whatsa trouble?" he demanded suspiciously, glaring down at little Mr. Joy.

"This guy," said Louie, "musta had too much to drink even before he came in here. One beer done this to him."

The waiter took another look at Mr. Joy, then at Louie the grifter. But if he had any doubts as to how Mr. Joy had arrived at such a condition, he kept them to himself. He nodded agreement.

"He's gonna be pretty damn sick in another minute," said the waiter, "and I don't wanta hafta clean up the mess."

"Then toss him out in the alley," Louie suggested with utter indifference. "He's no friend of mine. I never seen him before until I asked him to have a drink. Such people you got coming into this place!"

"Whatta bout the check?" the waiter demanded.

"Gimme it," said Louie, extracting little Mr. Joy's wallet from his pocket.

The waiter presented the bill, Louie glanced at it, took two dollar bills from Mr. Joy's fund of fifteen remaining dollars, and handed them carelessly to the waiter.

"Keep the change," Louie said nonchalantly.

The waiter looked at him scornfully. "All fifteen cents of it?" he asked bitterly.

"Sure," said Louie, reaching up to remove Mr. Joy's topcoat from the wall peg. He turned then, with the coat draped over one arm, and sauntered toward the door.

Behind him, he heard the waiter's flood of obscenity as he began the process of carrying an inert Mr. Joy to a rear entrance as a preliminary necessity to dumping the little man into the alley.

Louie grinned yellowly to himself, nodded to the shabbily uniformed doorman and bouncer of the tawdry bistro, and stepped out into the street.

NOW the itching excitement to get immediately to some secluded place where he could rip loose the lining of the coat and plunder the little man's booby bank became almost unbearable to the grifter.

He looked up and down the street in search of a deserted doorway or a convenient alley, then wondered if it might not be wiser to control his impatience and wait until he returned to his dingy hotel room before starting the search.

For perhaps half a minute Louie the grifter stood there on the sidewalk in front of the cheap night spot he'd just left, debating a course of action as his always darting eyes moved restlessly up and down the street.

It was then he saw the copper. The copper was just an ordinary beat patrolman, casually sauntering up the street to the rhythmic swing of his nightstick, but the sight of him was enough to bring a nervous flutter to Louie's stomach.

Louie watched the copper moving leisurely in his direction and realized that his unprecedented nervousness at the sight of the uniform was due only to the fact that he was on the verge of the biggest clean-up in all his experience as a small time grifter. Louie realized this, but was nevertheless unable to quiet the flutter. Supposing the cop got suspicious of something, or just didn't happen to like Louie's face?

Louie tried to look unconcerned. He steeled himself against a wild impulse to run. With hands that trembled, he fumbled for a cigarette and clumsily managed to light it.

The cop was now less than half a block away. Louie didn't dare move, for fear of doing something that would betray his alarm to the eyes of the copper.

And at that instant Louie realized how additionally conspicuous he must look standing there in the late autumn chill with a topcoat under his arm instead of on his back.

Cursing under his breath, Louie took the coat from under his arm and started to put it on. Fortunately, aside from weight, he and the little guy had been approximately the same size.

In his first effort to shrug into the coat, it slipped from Louie's unsteady fingers and fell to the sidewalk. Now utterly shaken, Louie grabbed it up wildly and managed, in his second effort, to don the garment.

Jerkily, Louie half turned to see if the copper had noticed. There was no question about it. The copper had noticed all right, and he was less than sixty feet away, coming directly toward the trembling little grifter, his cold, blue eyes fixed on Louie!

WITH a cursing sob, Louie looked wildly left and right for possible avenues of flight or refuge. He turned back toward the copper once more, just long enough to meet the scowling, frightening glare of the officer's stern appraisal.

Wildly, Louie took to his heels and ran, his breath ragged and burning in his thin, terror-filled chest. The pounding of his own feet on the sidewalk drowned out every other sound from his hysteria-deafened eardrums.

He was barely conscious of reaching the corner, scarcely aware that he rounded it at breakneck speed, utterly oblivious to the fact that an alleyway entrance was less than fifty feet away.

It was at the alleyway entrance that Louie slipped on a small patch of oil smear left by some recently drained truck crankcase. His legs shot out from under him, and there was a horrible moment in which his arms flailed nothingness. And then he landed jarringly, sickeningly on the solid cobblestones of the alley, his head cracking sharply against them.

In a daze of pain and terror, Louie tried to sit up. His head was swimming, his skull aching.

The huge headlights blinded him a moment later. The headlights of a mammoth freight truck moving slowly out of the alley and directly toward Louie.

Louie tried to rise. Tried to get out of the way of that truck bearing down on him with such hideous, inexorable might. He tried to rise, but the paralysis of fear had frozen him. He shouted, then. Shouted desperately. But the breath had left his lungs and his shout was a choking, inaudible wheeze.

Wildly, in the glare of those huge headlights, Louie waved his arms. Surely they'd see him! They had to! They had to! There was plenty of time for them to jam on the brakes as soon as they saw him!

Louie's scrawny frame scarcely jarred the giant truck as it rolled ponderously over him, pulping bones and flesh into the cobblestones of the alley.

The driver of the truck and his assistant were but faintly aware of the soft bump they went over. They mentioned it most briefly.

"S'funny," the driver remarked, "I didn't see no bump in them cobblestones."

His assistant yawned. "Neither did I," he said. "I was watching close, on accounta possible crates with nails. I didn't see nothing at all."

As far as they were concerned, that closed the incident. It closed the incident, too, that might have been labeled "The Life and Times of Louie the Grifter."

It can be presumed, of course, that a sadly disillusioned little gentleman named Mr. Joy was eventually successful in putting a request through the Heavenly Supply Room for another coat....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.