RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

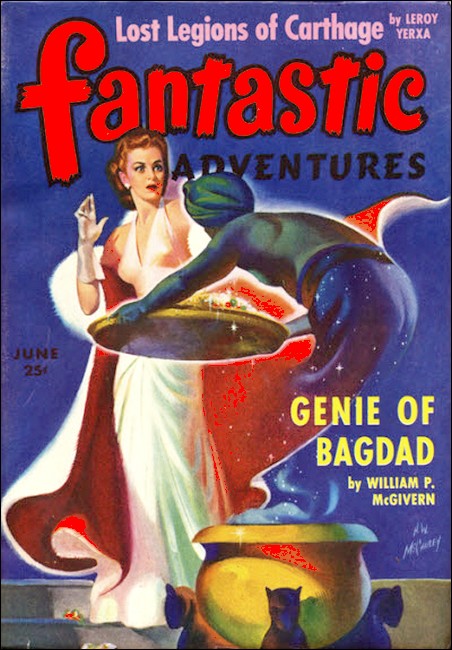

Fantastic Adventures, June 1943, with "Stenton's Shadow"

Stenton trained his gun on the motionless figure.

Stenton carried out the perfect crime. No one could possibly

connect him with it. Then why was he being shadowed?

WHILE the physician was in the bedroom with old Richard Frawley, Stenton paced nervously back and forth along the marble floored corridor just outside.

It seemed to Stenton, during that interminable wait, that every second was in itself an hour of eternity. And yet, when the physician finally stepped out of the bedroom and closed the door softly behind him, Stenton was aware that the examination had lasted little more than half an hour.

Stenton dropped the cigarette he had been smoking to the floor. He crushed it with his foot, looked up, and met the physician's sympathetically understanding smile.

"How—how is he?" Stenton asked. His voice was strained, husky.

The doctor stepped over to Stenton and put his hand on his shoulder in a gesture that was as reassuring as it was kindly.

"I think I can predict quite a few years more for him, Mr. Stenton," the doctor declared. "Rest, a complete abandonment of his business interests, and—when he's strong enough again—a long vacation in a moderate climate, are the things he needs. He has to remember that he isn't as young as he used to be. Heart attacks at his age are to be expected if he follows such strenuous schedules as he has been."

"Thank God!" Stenton blurted fervently. He ran a visibly trembling hand across his brow. "Thank God! I was afraid that—"

The doctor smiled reassuringly once more.

"I understand, Mr. Stenton. I know exactly how you felt. It must have been a terrible shock to think you might lose Mr. Frawley. I realize how much your relationship with him has meant to both of you. But stop worrying. Unless something entirely unforeseen occurs, my prediction is that Mr. Frawley might well reach eighty-five or more."

Stenton's relief was unmistakable and he made no effort to conceal his emotional state from the physician.

"Can—can I see him now?" Stenton asked.

"I'd wait an hour or longer," the doctor advised kindly. "I gave him a slight sedative which produced almost immediate slumber. It would be better if he had a little rest."

"Certainly," Stenton agreed readily. "Certainly. And what about a nurse?"

"I could recommend several," the physician suggested.

"Splendid," Stenton agreed. "And when could you arrange to have one arrive?"

"In three or four hours at the most," the doctor said.

"That will be soon enough?" Stenton asked anxiously.

The physician smiled. "He's in no danger. That passed with the attack. I can see absolutely no chance of another attack. But should anything come up before the arrival of the nurse, please call me at once. I'll be at the hospital."

"Of course," Stenton said ...

WHEN Stenton had shown the doctor to the front door, he went

immediately to the drawing-room where he mixed himself a whisky

and soda at the small table bar there.

Calmly, then, Stenton seated himself in a comfortable armchair, lighted a cigarette, and relaxed. He looked slowly around the big, old-fashioned drawing-room. Its paintings, tapestries, rugs and furnishings were heavy, ponderous, expensive. They had a solidity, a stuffiness, about them which had long seemed oppressive to Stenton.

Years ago this house, the Frawley Mansion, had been one the of the most luxurious homes in this wealthy residential district. It had been built by the present Richard Frawley's father, and handed through the will of the dying multimillionaire, to his son with the request that he always maintain it as his home.

Richard Frawley had done that. Even though he had never married, he had maintained this stuffy, gloomy old mansion as his home even after his father's death. But now, the once-young Richard Frawley lay upstairs in the palatial master bedroom, an old, weary man. A man without a wife, children, even relatives. A man with no one in the world to count on save Stenton.

He had counted on Stenton for many years now. He had started depending on Stenton when he adopted him as a boy from a city orphanage some twenty years before. From that day forward, Frawley had counted on his charge as if he had been in reality his son.

Stenton had been eight years old when the millionaire Frawley took him from the drab existence of the orphanage into the splendor and financial glitter of this now decadent home.

"I have always hoped that I might someday have a son," Frawley told the youthful Stenton. "In you, my hope can be realized. Always think of me as your father, boy. Never doubt or distrust me for a moment, for I shall never doubt or distrust you. From this day on, you are my son."

From that day Stenton had lived as Richard Frawley's son, the son of a millionaire. Richard Frawley had thought it wiser not to change the boy's name to his own, and hence Stenton had kept the name with which he had been christened at the orphanage.

He had attended the most expensive and exclusive prep schools, gained rugged young manhood at the most celebrated of mountain summer resorts and playgrounds, and at last matriculating at a world famous university which his father-by-adoption had attended.

Stenton did not throw away the opportunities, the privileges, granted him by his father-through-adoption. Indeed, he was an excellent student. His grades were brilliant, his ability to sop up knowledge utterly incredible. There was a cold, hard, ruthless efficiency in everything he undertook. His teachers respected young Stenton, but saw in that ruthless purpose of his something beyond their ken. Something as chilling as ice.

As Stenton worked and learned, so did he play. His campus escapades grew to legends. He figured prominently in almost all the notorious collegiate high life scandals. But somehow he managed to save himself from dismissal. And somehow he saw to it that word of these escapades never reached his pseudo-father, Richard Frawley. Perhaps one of the things that saved Stenton from dismissal was the fact that his hard drinking, fast gambling, riotous collegiate existence seemed never to interfere with the excellence of his scholastic grades.

At any rate, his professors added to their data on young Stenton one additionally curious fact. It seemed that, although he figured prominently in collegiate social life, he had not a single friend among his fellows. Perhaps Stenton wanted no friends. Or perhaps his fellow students felt his contemptuous scorn of them, and therefore wanted none of him.

UPON graduation from the university, Stenton was given a world

tour with which Richard Frawley expected him to round out his

education. On that tour, which lasted for over a year, Stenton

picked up a remarkable fluency in seven foreign languages, not to

mention an apparently inexhaustible fund of information

concerning the history, customs, and culture of the peoples of

the countries in which he visited.

Stenton returned from this tour to a place in Richard Frawley's business. Needless to say, Richard Frawley became dependent upon his adopted son in matters pertaining to his own business in little more than two years.

To say that Richard Frawley was proud of the accomplishments of his pseudo-son would be depicting that aging industrial tycoon's emotions mildly.

He was only too pleased to find Stenton fitting into his business so admirably. And, of course, the fact that Stenton was "home" once again, residing with Frawley in the huge old brownstone mansion, was something else that meant even more to the millionaire.

"It's great to have you back here, son," Frawley told Stenton. "And frankly, boy, I'm proud to have you at my side wherever we go. But, however, don't let me try to monopolize your outside time and interests completely. I know I'd like to do just that. But undoubtedly you have friends and associates more your own age with whom you'd like to spend your leisure time. Old fogies like myself and my friends at the club can't be expected to hold much interest for a young blood like you."

Stenton had demurred. He insisted that he much preferred his pseudo-father's company to any other. This, of course, strengthened the affection which the aging Frawley already felt toward Stenton, and made his pride in the young man even greater.

Undoubtedly Richard Frawley never realized that Stenton, although a personable young man, charming as well as brilliant, was quite curiously lacking in friends and even close associates.

NOW, sitting there in the drawing room of the old brownstone

mansion, Stenton allowed all these things to pass through his

mind as he calmly sipped his whisky-soda and smoked his

cigarette. He thought of all these things and their place in the

pattern of years in which he'd been the adopted son of Richard

Frawley, and smiled.

Richard Frawley, old Richard Frawley, now, lay upstairs alone and ill in that great canopied bed. Stenton had expected the heart attack which was the cause of the old man's present condition. He had been expecting it for over a year now.

He had been more or less counting on it.

Stenton finished his whisky-soda and crushed out his cigarette in a bronze ash-tray at his elbow. Glancing down at his watch, he noted that it was almost ten minutes since the doctor had been ushered from the brownstone mansion.

Under the influence of the sedative given him by the doctor, old Richard Frawley was undoubtedly still in peaceful slumber. The physician had said that he'd send a nurse around inside of three or four hours at the most.

Stenton, methodically enough, was taking every last advantage of the time allotted him for his plans.

As he started up the staircase to the second floor, he lighted another cigarette and was suddenly surprised to realize that his hands were trembling ever so slightly in the process.

Stenton frowned at this, mentally berating himself that it could be possible.

Yet, by the time he stood atop the second floor landing, a certain uneasiness—reflected in the moisture of his palms and the acceleration of his heartbeat—became additionally evident to Stenton.

"I'm acting like a fool," he told himself. "A damned fool!"

However, he stood there at the top of the second floor landing, looking down the marble-floored corridor leading to old Frawley's bedroom door. Hesitated there in spite of himself.

"I've waited for this too long," Stenton told himself, "to get squeamish at the last minute."

Stenton took a deep breath, threw back his shoulders, and started down the corridor in the opposite direction to old Frawley's bedroom door. He was going to his own bedroom, several doors away.

It was scarcely two minutes later when Stenton emerged from his own bedroom. And when he did, he carried a small, soft cloth in his hand. A cloth which had been soaked in a solution prepared by Stenton several hours previously.

Now he started resolutely toward old Frawley's bedroom door. There was no hesitation, furtiveness, in his stride. It was Thursday night, and the majority of the servants were out. Charles, the old butler, was asleep in his quarters over the garage in the back of the brownstone mansion. None of the others would be back until midnight or later.

But again Stenton hesitated. Hesitated as he stood with his hand on the knob of old Frawley's bedroom door.

Supposing the old man were awake?

"That won't make any difference!" Frawley snapped irritably to himself. And a hidden voice, deep in his soul, said: Stenton, can you do this thing? Can you do this thing to the man who has done so much for you?

STENTON was ruthless, cold, calculating. This was something he

had been planning for the last four years. This was his chance.

Stenton was no fool. Standing there, he told himself again that

he was no fool. He reminded himself, savagely, that he had

divorced himself long ago from that thing men call a

conscience.

But have you? said the inner voice.

Have you? it asked again.

Stenton steeled himself against those taunting mental voices. Grimly, he summoned the almost indomitable forces of his will—long trained for a moment such as this—to drive from his consciousness all remaining remnants of that inner voice of decency which was his conscience.

The veins stood out in his temples, his brow shone with the perspiration of this superhuman effort to smother that tiny flame which alone stood in the way of his desire.

And for the dynamic, exhausting eternity of a moment, Stenton's conscience was locked in a death grip with his will power.

And then it was over.

As if something had suddenly snapped, severed completely from his spiritual being, Stenton felt the swift, boundless freedom of utter evil flood through his being.

His conscience was gone—driven from his body as if it had been a physical thing, divorced from his soul with the surgical finality of a knife thrust.

The power of his will had triumphed!

Stenton stood there with his hand on the knob of the door, momentarily shaken by the conflict that had been waged in his soul. Something closely akin to fright passed through his eyes and was gone in the next instant.

He smiled then, a cold, curiously inhuman smile, and turned the knob beneath his hand.

Softly, Stenton opened the door. Noiselessly, he stepped into the room. There in the big bedroom, scarcely ten yards from where Stenton paused, was the great, canopied bed in which the sleeping Richard Frawley lay.

A small light burned on a table a few feet from the head of the bed. Across the room, the blinds were drawn.

Stenton saw Frawley's white head against the pillows, then, and started softly toward the bed.

Beside the small table on which the light burned, Stenton paused. He was standing less than three feet from the bed. Old Frawley's eyes were closed, his breathing quiet and regular.

"So you'll live for quite a while longer, eh?" Stenton thought.

Now Stenton stepped up to the bed. From where he stood he could bend forward and touch the old man's forehead.

Stenton glanced down at the solution-soaked cloth in his hand. He leaned forward, holding the cloth away from him, and clamped it swiftly, firmly, down across the old man's nose and mouth.

THERE was a muffled cry, a spasmodic upheaval of the

bedclothes that covered old Frawley, and one of the old man's

arms groped weakly toward the hand holding the suffocating,

solution-soaked cloth.

But it never reached Stenton's hand. It fell back, an instant later. And the brief upheaval of the bedclothes stopped as the frail body beneath them went lifeless.

Stenton held the cloth there for several moments longer. And then he took it away, straightened up, and looked down at the body of the man he had just murdered.

It was done. It was over. Richard Frawley lay dead in the great canopied bed in which his ancestors had breathed their last. And the man he had taken as a son, the man to whom he had given the care and kindness and legal privileges of a son, had slain him!

Stenton smiled softly.

"Good-bye, old fool," he whispered. "Say hello to the worms for me."

Then he turned away from the bed. There were many things to do now. The solution, a devilishly undetectable concoction which Stenton had gone to considerable trouble to obtain, would leave no traces. But the small bottle of it in Stenton's room, and the cloth soaked with it in his hand, were things that he must dispose of immediately.

There would be a telephone call to the doctor. He'd better wait an hour or so longer for that, as he'd planned. Wait an hour or so, then declare that he'd only then stepped into the old man's bedroom, and that he couldn't tell when the old fellow had had this unexpected second attack.

The nurse would arrive after a while. But not before Stenton had called the doctor. And then, of course, there would be all the rest of the details that follow any death.

Still smiling, Stenton moved to the door. There, he paused for an instant and glanced back at the great canopied bed. The light on the small table still burned, and from the doorway you couldn't tell if the old man were sleeping or dead.

Unless, of course, you had just murdered him....

IT was no surprise to Stenton that things went off so very

smoothly in the next three days. He had planned everything much

too thoroughly for it to have been otherwise.

The newspapers, of course, carried the story of Richard Frawley's death in appropriately wide column spreads, carrying, too, the biography of that internationally famous millionaire.

Stenton saw to it that, for his part, the items in the papers were of precisely the tone he desired. It had never been a secret to anyone that Stenton would inherit all the Frawley commercial enterprises upon the old man's death. Nor was it supposed that the bulk of his personal fortune would go to anyone but Stenton.

That people who knew Stenton as well as old Frawley would surmise that the pseudo-son of the millionaire might have long waited for the untold riches and power of his inheritance was ridiculous. All were aware that Stenton, ever since he'd gone into the old man's business, had himself amassed a fortune great enough to enable him to live in luxury the rest of his long life without benefit of the old man's legacy.

Naturally, therefore, the possibility that Stenton might have been instrumental in the death of his benefactor occurred to no one. It would have seemed a preposterous assumption, unless one knew the mind of Stenton.

And Stenton had no friends, no acquaintances, close enough to have the slightest inkling as to the sort of a person he was. There was none who realized that Stenton could never be content with the small fortune he already possessed. There was none to suspect that Stenton wanted riches and more riches, not for the luxury they would afford, but for the power they would place in his ambitious, conscienceless hands.

None knew the soul of Stenton, save Stenton himself.

IN the week that followed old Frawley's funeral, Stenton

completely reorganized the dead millionaire's holdings. The old

man's will had not been read, his final requisitioning of

property, personal and commercial, had not been legally cleared.

But this made no difference. All took it for granted that Richard

Frawley's legacy would leave Stenton with practically everything

the old man had possessed.

Stenton found himself with an untroubled mind to carry out what was really the beginning of his plans for power beyond all ambition. Indeed, it surprised him somewhat that his conscience—from his moment of severing it to go through with the murder of the old man—had never troubled him after that.

This surprised him but, naturally, was a matter of deep elation. Though he had never before possessed a tenth of the conscience of a normal man, even knaves, he realized, had occasional qualms about their crimes. Stenton, before the murder of his benefactor, now and then had had such occasional qualms. But it seemed now as if they were gone forever.

Stenton made arrangements to dispose of the loathsome old brownstone mansion, gave notice to the servants who had been a part of the Frawley household almost since their childhood, dismissed several of Richard Frawley's oldest and closest friends from important positions in the commercial houses controlled by the old man, and, generally, carried out the beginning of his plans with ruthless high-handedness.

On the afternoon before the old man's will was to be read, Stenton called in the board of directors of the Frawley enterprises and told them in no uncertain language of the policies he meant to inaugurate.

Stenton was no fool at this conference. He was clever enough to insult only those board members whom he considered to be dead timber and useless to his plans. When they, as he had expected, came to indignant disagreement with his suggestions, he regretfully requested and received their resignations.

When Stenton had cleared the conference of the dead timber, he went into an elaboration of his replanning schemes to the remaining members. In some of these men Stenton had previously recognized cold, cunning ruthlessness comparable to his own. They fitted perfectly into his pattern. In others of them, those who were not basically the sort that Stenton desired, Stenton had carefully been able to discover, long ago, hidden indiscretions in their lives. Subtly, Stenton made each of these otherwise respectable men aware that he had knowledge of the errors in their pasts. And even more subtly, Stenton made it plain to them that he expected—because of the hold on them his knowledge afforded—their implicit compliance with his every demand. No, Stenton was no fool. The names of these otherwise blameless men would enhance the reputation of his corporations. Stenton could use them in that fashion—until he had no further need of them.

At length, about six o'clock that evening, Stenton closed the conference he had called.

Sitting around the huge, polished table which he headed, were all those men he had selected, for one reason or another, to fit into the new pattern he'd established.

Stenton smiled coldly at them, crushed out his cigarette in the ebony and onyx ash-tray by his elbow, and rose.

"I think this meeting, although it has been rather long, has established my new policies clearly in the mind of each of you gentlemen who comprise my reshuffled board of directors," Stenton announced. "I am also quite certain that the eventual scope of operations under our reorganized corporations is quite clear to all of you. Until today each of you considered himself an important cog in one of the nation's greatest financial and commercial enterprises. The Richard Frawley Corporations were indeed tremendously important. I am not trying to belittle what they have been in the past. However, mark my words, gentlemen—the world is just beginning to comprehend what I and my corporations will do in the future. We shall someday be the greatest industrial and financial house in the world. We shall someday virtually own this world."

Silence greeted Stenton's words as he closed the conference. Silence, and an awed, incredible fear in the eyes of even the most ruthless and ambitious of his listeners.

They were just beginning to have some conception of the mind of the man who planned power that would bring him mastery of the world. They were the first men to have even the slightest glimpse into the cold, conscienceless soul of Stenton....

ON impulse, Stenton decided to forego dining out that evening.

And when he left the large Frawley Building, after the momentous

conference, he sent his limousine and chauffeur ahead, choosing

to walk the not too long distance to the old brownstone

mansion.

It was midwinter, and the early evening was already dark. A light snow had started, and the thin, confetti-white flakes sifted softly down through the warm glow of the street lamps.

Stenton walked briskly, his collar turned up, eyes straight ahead, his thoughts concerned with the official reading of old Frawley's will at ten o'clock the next morning.

It had been the old man's request that the will be read in the library of the old mansion, as previous Frawley wills had always been. All the old family servants would be there, plus a scattering of distant relatives or their lawyers.

Stenton smiled thinly at this thought. The vultures would gather to pick the bones of the sheep the wolf had slain. Or so the vultures thought. Stenton was confident that the bulk of everything would go to him. There would be but slim pickings for the vultures. He, Stenton, the wolf, would have cleaned the carcass too well.

Turning off into a side street, Stenton stopped for a moment at a corner news-stand to purchase a paper. Briefly, he scanned the headlines and the smaller stories on the front page. Swiftly, then, he flipped to the financial pages, studied the final market returns which, in the emergency of the board conference he had forgotten to check, and then carelessly tossed the newspaper into the snowdrifted gutter.

It was then that Stenton noticed for the first time that someone stood across the street in the shelter of a doorway—someone who was looking at him.

The man was tall, about Stenton's physical dimensions, and wore a black coat with the collar turned up as was Stenton's. His black fedora was pulled low over his eyes, so that Stenton was unable to see anything of his features.

There was no evidence whatsoever that the man was staring at Stenton. He might well have been staring at the newsstand and all who paused at it. But there was something, something akin to intuition, that made Stenton feel the fellow's gaze regarding him steadily. This feeling, this intuition, had been so strong, in fact, that Stenton began to wonder if it had not been the cause of his having noticed the watcher in the first place.

For fully half a minute Stenton stared across the street at the figure in the doorway. Stared steadily, curiously, uneasily, as if compelled to do so by some hypnotic force.

And as he stared, the figure in the doorway returned the stare while remaining motionless, hands deep in his overcoat pockets.

Suddenly Stenton cursed irritably. "My God!" he told himself. "I don't know what caused this crazy fit of imagination. The man's just standing there, waiting for someone, perhaps, and staring at the newsstand. What on earth is wrong with me?"

Stenton took his gaze from the man in the doorway and turned away, starting down the lonely little side street at a brisk pace. He was suddenly angered with himself. This had been the first spot of nerves he'd had since he'd killed old Frawley.

"What a juvenile, imaginative rash!" Stenton told himself wrathfully. Then he determined to push the incident from his mind so that it wouldn't disturb him further.

WHEN he had walked a block, however, Stenton, in spite of

himself, turned swiftly and faced in the direction from which he

had come. Squinting through the snowflakes, he peered across the

street to see if the man in the doorway was still standing

there.

The man was no longer in the doorway. He now stood on the sidewalk in the middle of the block, on the other side of the street. Stood motionless, as if he had paused the instant Stenton wheeled about. As if—and Stenton raged at himself for the thought—he had started to follow Stenton.

For a moment Stenton stared at the black-clad figure. And again his intuition told him that the stranger was staring at him.

Stenton cursed and turned away suddenly. Swiftly, he determined to take another side-street route to the brownstone mansion. An even more deserted side-street route. Then he would be able to determine if this ridiculous imagining held any grain of reality.

Quickly, Stenton turned right. Now he walked even more briskly, his long strides eating up the distance. And at the end of the next block he stopped suddenly as before and wheeled to face in the direction from which he'd come.

Again the dark overcoated figure stood half a block from him on the opposite side of the street. And again Stenton felt that the man had stopped the instant Stenton had wheeled about.

Stenton's breath came fast and his heart pounded in sudden excitement. He had been correct. It hadn't been his nerves. He was being followed!

For fully a minute Stenton stood there staring at the motionless figure. And during that minute, the other man halfway back across the street seemed not to move a muscle.

Stenton was not a coward. He had never known fear. Not physical fear. Quickly, coolly, his mind sorted the possible meanings that might be attached to the purpose of the stranger's shadowing.

Police?

The thought was ridiculous. The police could not suspect anything. The autopsy had not revealed anything but the death of old Frawley by heart attack. The rest of the evidence had been thoroughly, painstakingly, destroyed. No—Frawley was buried, safely out of the way. He had died, officially, of a heart attack. It was impossible to think that the police might have unearthed anything to point to any other conclusion. And if they had done so, it would be ridiculous to assume they would have him trailed. If they had stumbled over any evidence pointing to the truth they would have apprehended Stenton immediately. No, that man back there across the street was not from the police.

But he might be a thug, a gunman, a bandit planning to force Stenton at gun-point into some alley as soon as the neighborhood became deserted enough.

That seemed to be more likely.

ON sudden impulse, Stenton crossed the street to the side on

which his follower stood. Then he started walking toward him. And

suddenly the other turned away and began to walk rapidly in the

opposite direction.

Stenton increased his own pace until it was almost a run. The other did the same, keeping the distance the same between them.

Stenton stopped abruptly.

The stranger stopped also. Stopped as immediately as if he had been facing Stenton and able to see that he'd paused. Now the stranger turned to face Stenton again.

For a moment they were staring at one another once more. Then Stenton laughed, a dry, brittle laugh. His second conclusion must have been correct. The man following must be a bandit, although a timid bandit.

Stenton smirked contemptuously. An amateur bandit, a bumbling knave. Stenton had no respect for a knave who lacked courage. And yet, why did the fellow still stand there? Why hadn't he continued to flee when Stenton had started after him?

It was silly, damned silly. Utterly ridiculous. And yet, it was not right. There was something strange about it. Something eerily, ominously—although ridiculously—strange about it.

Stenton's amused contempt vanished in the face of a renewed surge of irritation and impatience. He cursed and turned away, starting back to the corner from which he'd started his pursuit of the fellow.

And then he saw the taxi.

It was unoccupied, and had just turned the corner toward which Stenton was walking. He shouted at it.

The driver heard Stenton's shout, made a U-turn in the street and pulled up to the curb where Stenton waited.

Stenton climbed into the cab, gave the driver his address, and settled back. But as the cab pulled away in a clash of gears, Stenton could not resist one last glimpse of the stranger through the rear window of the vehicle.

The dark-coated stranger still stood there, as Stenton had left him. He was, of course, watching the swift departure of the cab.

ON the way to the brownstone mansion, Stenton thought

irritably about telephoning the police when he arrived home. He

could give them what little description he had of the man who'd

followed him, and hope that perhaps they'd nab the fellow.

But after he had lighted a cigarette, Stenton decided against that. It would sound too ridiculous, and besides, there was no sense in bringing the police into anything concerning his private life.

During the rest of the ride home, Stenton was unable to put the incident from his mind. There were other things to which he wanted to put his attention. Considerably more important things than a ridiculous encounter with a timid bandit.

And yet, as Stenton paid the cab driver in front of the mansion, he still chaffed mentally over the incident, unable to drive it from his mind.

As the cab pulled away from the front of the house, Stenton saw the man again.

For an instant he wasn't certain it was the stranger. And for another instant he knew it couldn't be the stranger.

But it was, and he stood across the street at the far end of the block, directly under a street-lamp, gazing toward the brownstone mansion.

Stenton blinked unbelievingly, his jaw falling agape.

The stranger, as before, stood utterly unmoving, hands in his overcoat pocket, black fedora pulled low over his eyes, collar turned up high beneath his chin.

Stenton's wrath suddenly broke its dam. He stepped down from the curb and started to cross the street.

And then the stranger turned and started in the opposite direction, moving with a long, swift unhurried stride which was obviously designed to keep the same distance between them as before.

Stenton stopped, halfway across the street, and at that instant the stranger stopped also.

Stenton opened his mouth to shout. Then he clamped his jaws shut, angrily clenching and unclenching his fists. A wave of maddening exasperation flooded him, and he fought for self-control.

Suddenly he turned and without looking back over his shoulder, walked back to the sidewalk and through the big iron gates opening into the steps of the brownstone mansion.

Not once did Stenton turn as he climbed the steps. At the top, he punched the bell angrily, feeling the stranger's eyes on his back as he did so.

STENTON waited several minutes before Charles, the old butler,

finally opened the door.

The old servant was startled by the expression on Stetson's usually poker-cold face.

"G-good evening, sir," he stammered. "Is—is there something wrong, sir?"

Stenton merely glared at the old servant, and strode angrily past him into the big marble hallway. The butler closed the door and hurried after him in a futile effort to assist Stenton with his coat.

"We—we didn't expect you so early, sir," the butler apologized. "We thought that you would be dining out. There is nothing prepared. Cook will have to—"

"I understand all that," Stenton snapped irritably. "Get something prepared as quickly as you can."

With that Stenton strode wrathfully into the drawing room. He went immediately to the liquor stock, and noticed, as he prepared himself a strong drink, that his hands were shaking.

Stenton downed four fingers of whisky without benefit of soda. Then he looked speculatively at the bottle for a moment, and repeated the process.

He lighted a cigarette and saw that much of the tremor in his hands had been steadied by the liquor.

Now Stenton poured himself two fingers of whisky, and this time added soda to it. Then glass in hand, cigarette hanging from his lips, he walked quickly to the wide drawing-room window. It faced out on the street from which Stenton had just come. It presented an unimpeded view of the corner on which he had last seen the stranger.

But the stranger, Stenton saw, no longer stood on that corner. He had advanced to a position on the other side of the street directly across from the old brownstone mansion. And he was gazing stolidly up at the window in which Stenton stood!

Stenton's curse was hoarse, involuntary. He reached for the cord controlling the blinds and savagely drew them shut.

Walking back to the liquor cabinet, Stenton placed his drink on the top of it. Then he ran a trembling hand across his eyes.

"God," he whispered. "What in the name of all unholy is this? Who is he? What is he? Am I losing my mind?"

Stenton wheeled and started for the cradle telephone in the corner of the drawing room. He was reaching for it when he stopped abruptly, straightened up.

Something, some instinct, had told him that the action he'd contemplated would be useless. Calling the police would not help. He knew it would not help. Why he knew so, Stenton had no idea.

Stenton strode back to the liquor cabinet, and ignoring his moderate whisky and soda, took a clean glass and the bottle. He poured a tremendous hooker of whisky into the glass, lifted it and drained it in a gulp.

Then he turned away, starting, in spite of himself, back to the window. There Stenton drew the blinds back with one hand enough to peer through them out into the street.

The stranger still stood there, directly across from the brownstone house. As far as Stenton could see, he hadn't changed his watching position by so much as the movement of a muscle.

STENTON let the blinds fall back into place. Shakily, he moved

to an armchair and sank down in it. Leaning forward, he put his

head in his hands, closing his eyes and fighting against the

nameless fear that was beginning to possess him.

This was insane, ridiculously insane. He should go at once to the telephone and call the police. He should describe the loiterer outside his house, he should explain to them that the fellow had followed him. He should—

But he couldn't. Stenton knew he couldn't.

He didn't dare. Supposing the fellow were someone who, somehow, knew.

That was preposterous!

No one knew. No one save Stenton—and old Frawley. There couldn't have been any slip-up. If his crime had been discovered by the police it would have meant his apprehension by now. And if it had been discovered by anyone else, servant or housebreaker, the blackmail wouldn't begin in this fashion.

No. It was not that. It couldn't be that.

Stenton rose from the armchair, walked to the liquor cabinet, and poured himself another stiff drink.

The whisky was steadying him, but not enough. Although by now he'd consumed a considerable amount of it, he found his mind not even a trifle fogged. He was as completely sober now as he had been when he'd entered the drawing room.

Stenton stepped around the liquor cabinet and tugged at the tassled bell-cord which would summon old Charles, the butler.

He lighted another cigarette as he stood there waiting, and in another minute Charles appeared breathlessly at the drawing room door.

"You rang, sir?"

Stenton looked wordlessly at the old servant for a moment. Then he cleared his throat, gathering himself together by that commonplace action.

"Must Cook take all night to serve my dinner?" Stenton said, and he found his voice was rasping, ragged.

"It—it is almost ready, sir," the old man stammered. Then, his face wreathed in concern, he asked anxiously: "Is something the matter, sir? Are you ill? Do you wish me to telephone for a doctor?"

"Ill? Ill?" Stenton laughed harshly, unconvincingly. "What makes you think I'm ill?"

The old butler looked both concerned and embarrassed.

"Your complexion, sir, is positively ashen."

Instinctively Stenton's hand went to his cheek. Then he jerked it away and glared balefully at the old man.

"Get out of here!" he rasped.

When the old butler had retreated bewilderedly, Stenton went again to the wide window of the drawing room. Again he peered out through the corner of the drawn blinds.

The stranger still stood where Stenton had last seen him. His eyes were fixed unwaveringly, it seemed, on the window of the drawing room....

IT was almost eight o'clock when Stenton pushed the last of

the scarcely touched plates away from him and rose from the

table.

He had been served by old Charles; and the butler, frightened and alarmed at Stenton's manner, had made a poor job of concealing the emotional disturbance under which he labored.

Stenton was aware that the old man had been on the verge of again suggesting that he call a doctor. But the fear of Stenton's possible reaction had forced him to hold his tongue.

Stenton had tasted but a few mouthfuls from each plate, almost immediately pushing them away after each course. And when the uneaten meal was over, old Charles timidly asked: "Is there anything more, sir?"

"No," Stenton snapped. "You can get the hell back to your room. I won't need you for the rest of the night. Now, clear out!"

Stenton had left the dining-room, then, drawn irresistibly back to the drawing-room. There, after several more drinks, he had at last stepped over to the window and peered through the blinds out into the street.

The stranger still stood where he had been before. Stood in exactly the same position as before. He had apparently been as motionless as a statue.

Stenton couldn't see his eyes, of course. The light of the street lamp and the distance itself made that impossible. But Stenton knew those eyes were still unwinkingly staring at the drawing room window.

For an instant after he had again let the blinds fall back into place, Stenton considered going out there into the street in an effort to catch the fellow once more.

But he discarded his idea immediately. It would be impossible, as it had been before, he told himself. But in spite of his rationalization, Stenton now doubted whether he wasn't afraid that he might be able to catch the fellow.

Stenton left the drawing room, then, and went upstairs to his bedroom. As he reached the top of the marble staircase he saw the doorway of the bedroom that had been old Frawley's. For an instant Stenton found his gaze hypnotically glued to it, and then he was able to tear his eyes away.

In his own bedroom, Stenton changed to a dressing gown and slippers, found some papers he had intended to work on, picked them up and started for the door. Then, motivated by an unexplainable instinct he stepped to the drawer of his dresser, opened it, and took out the small, compact automatic pistol he kept there.

Stenton slipped the weapon into the pocket of his dressing-gown, and with his papers once more in hand, left his bedroom and went back downstairs.

Something caused him to pause when he reached the hallway. He had the sensation that the front door had been but recently opened to admit someone from the street. There was a chill in the air, as if the hallway still carried some of the wintery air from outside.

STENTON set his jaw. That was too preposterous. Had anyone

come into the house while he'd been upstairs he would have heard

him quite plainly. Fighting off any further suppositions of that

nature, Stenton went on toward the drawing-room.

He was just before the threshold of that room when he paused again, as if frozen by the sudden, numbing chill of premonition that swept up his spine.

Something deeper than instinct told him that someone was waiting for him in that drawing-room. Some chilling sixth sense that was like an icy breath on the nape of his neck.

Stenton's hand went to the gun in the pocket of his dressing gown, and his other hand tightened convulsively on the sheaf of papers. Steeling himself with superhuman will, Stenton stepped into the drawing room.

The stranger was there.

He stood beside the small desk in the right corner of the room. He still wore the black overcoat, collar up, and the black fedora, brim low over his eyes.

Stenton's heart was pounding frantically from something deeper, more primitive than physical fear. Instinctively, he whipped the automatic from the pocket of his dressing-gown and trained it rigidly on the intruder.

"Now I'll find out," Stenton heard his voice rasping. "Just who in the hell are you!"

The stranger was still motionless, even though he spoke.

"Don't you know who I am?" he asked. His voice was low, soft, almost a whisper.

"Damn you," Stenton grated, "put those arms above your head, and don't try anything! Who are you? Why have you been following me?"

"Don't you know?" the stranger asked softly.

It was then that Stenton began to sense it. Began to sense it in spite of the fact that the stranger's face was almost completely shadowed and that he still wore coat and hat. There was something excruciatingly, tantalizingly familiar about that figure.

"You'd better explain quickly," Stenton rasped warningly.

"Look hard, Stenton," said the stranger quietly.

Stenton's finger tightened on the trigger of the gun in his hand. He wet dry lips with a tongue that seemed swollen. His eyes bulged from his sockets as he stared at this intruder. Then, suddenly, his gun hand wavered and he stepped back.

"No!" Stenton grated.

"Yes," said the stranger. "I look exactly like you, don't I, Stenton? In fact, were you wearing these clothes it would be impossible to tell the difference between us. I look so much like you, Stenton, that I am, in part, actually you!"

Stenton was unable to speak. Again he ran his swollen tongue over his dried lips. His eyes were growing fever-bright, his entire body beginning to tremble.

The stranger suddenly took his hands from his pockets. In his right hand was a paper on which something had been written.

"This tells it all," the stranger said, holding forth the paper. "I signed it, since our signatures would be identical. It's your full confession, Stenton. It will clear up old Frawley's murder, won't it, Stenton?"

Stenton at last found voice.

"Damn you," he grated. "You'll never force me to do that. I'll—"

The stranger cut him off. "You can't escape me, Stenton. You tried, just before you killed him. You thought you got rid of me, but you hadn't. I'm back, Stenton, and now you must reckon with me."

Stenton's strangled, sobbing curse was lost in the smashing report of the gun in his hand. He fired once, straight at the skull of the stranger, and the room shook with the ringing of the report.

But the stranger didn't fall. Even through the shot must have smashed into the side of his skull, even though the bullet must have torn through his brain, the stranger didn't fall.

Stenton fell instead, the smoking gun clattering from his hand to the polished floor. Stenton fell, with half the side of his head blown away by the bullet's smashing force.

The stranger watched Stenton fall. Then he stepped over to the body and placed the paper beside it....

THE newspapers were full of it.

Stenton's suicide was front page news in itself. But the signed confession found beside his body, the confession to the murder of Richard Frawley, made it more than sensational.

The explanation of his action made it clear just why, when he'd never have been suspected, Stenton had taken that way out. The explanation was found in the last line of his confession, just above his signature.

"My conscience," Stenton had stated in that last line, "would never let me rest."

No one, of course, ever imagined that that last line was anything more than a figure of speech.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.