RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

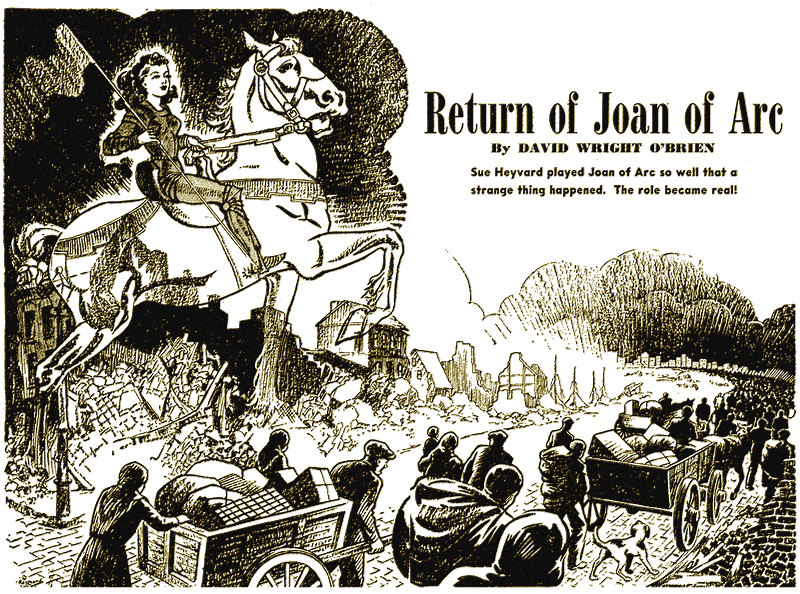

Fantastic Adventures, May 1942, with "Return of Joan of Arc"

Somewhere over there Joan of Arc rides again!

ON the frosted glass door of my office there is a sign.

TAD BARROW—THEATRICAL PRODUCER.

It has been there for twenty-five years, and like myself it holds its age very well considering everything. The paint is a trifle scarred, of course, but I've never bothered to have the lettering done over. Noel Coward has looked at that lettering. So have Bea Lillie, Will Rogers, Eddie Wynn, John Barrymore, Gene O'Neil, Ben Hecht, De Wolfe Hopper—just to give you an idea. The scarred black letters are good enough for the punks of today.

I've seen them all, big and little, ham and genius, and people in bars and at parties are always getting me off into a corner to ask me who, in my opinion, is the greatest actress ever to stand behind the footlights.

Sometimes, when my stomach is acting up and I feel surly, I ask them how in the hell should I know? After all, I have seen the very greatest, and it would be impossible to pick one in particular from such a staggering array of talent past and present.

But other times, when the Martinis are taking a nice effect, and I find myself imbued with a lush and rosy glow, I lean over and whisper, with complete truthfulness:

"Susan Heyvard."

"Susan Heyvard?" is the general reply. "I, ah, don't think I remember her clearly. What did she last appear in?"

And then I remind them that her one starring appearance was in the lead of one of my productions about a year and a half ago, and that until that time she had played only secondary roles.

"Oh, yes," I am then told doubtfully. "I think I do recall Susan Heyvard. She got rather nice reviews in that production of yours, didn't she? What happened to her after that? Didn't she get married or something?"

I feel, sometimes, like reminding my questioner that Sue Heyvard's reviews in my last show were nothing short of terrific. But she only had one lead, and that's the way the public memory is. If she'd stayed on—

But she didn't stay on, and even though the public will recall her name with difficulty, I am one person who will never forget Susan Heyvard. Or the day she first stepped through the frosted glass door bearing my name in scarred black point...

IT WAS in the summer of 1937. The day was dusty and

sweltering. I had just finished casting on a new show I was going

to produce for Toby Evans. Melvin Gardner had written the script,

and it was a corker. Of course you remember it. House of

Chaos, was the title.

Maybe I felt irritable. Maybe it was the heat. Broadway in mid-July is hell. Or maybe it was my stomach. At any rate, when Sue Heyvard stepped timidly through the door and stood there desolately in my deserted outer office, peeking in at me where I sat, I was annoyed.

"Well?" I snapped. "What is it?"

Sue Heyvard was wearing a frayed black serge suit—in the middle of July, mind you—and a worn black felt hat. Her nose was red and her face shone with perspiration. She had long black hair that fell stringily to her shoulders, framing a pinched, pale, most pathetically eager face.

She had brown eyes. The brownest, widest, most incredibly alive eyes I have ever seen. They were filled with fright, and utter weariness, and the damnedest determination you've ever seen.

"You... you are Mr. Barrow?" she stammered faintly.

"I am Tad Barrow," I admitted sourly. "And if you've a piece to speak, I'm sure both of us would be saved a lot of shouting if you'd step into my inner office here."

She came into my office, still wearing that curious mixture of timidity and determination. Standing in the outer office she'd looked like hell. Now, less than three feet from me, she looked worse than that.

"Well?" I demanded.

"I heard you are casting for a new production," she said. I noticed for the first time that her voice, in spite of its fright, was low, cool, surprisingly close to being beautiful.

I sighed.

"I have completed casting," I said.

"But, I—" she began.

"I sent out notices," I said, "giving the time and date of my casting. If you didn't get them straight and consequently walked in here after it was all over, you can't expect me to do anything about that."

Sue was twisting worn white gloves miserably in her thin hands. Those hands were very red, as if from a lot of dishwater, restaurant variety, and when she saw my eyes fixed on them she quickly put them behind her back.

"I'm sorry," I said a little bit more kindly.

She half opened her mouth, as if to say something, then shut it tight. I found out from her later that she'd been late because of her inability to get away from the restaurant where she was soaping dishes for the first square meals she'd had in weeks.

"That's all right," she said, forcing a tight little smile. Her wide brown eyes were suddenly watery, and naked discouragement shone behind their mist.

"What experience have you had?" I asked, then added quickly, "I might as well know for future reference." Sometimes just a few words like that gave them encouragement enough to try again.

But she sensed that I was merely giving her a straw for courage, and the discouragement didn't leave.

"None," she said softly. "I haven't had any real experience."

HOW often have I heard that phrase from poor kids like

her? I sighed, and tried to think of some way to tell her to go

back to wherever she came from.

"I know what you're thinking," she said wearily. "But I can act, I know it!"

I shook my head.

"Not even community theater work, or school plays?" I asked. Most of them had at least those standard pegs on which to hang their convictions about their ability.

"No," she said. "But I know I can act!"

I looked at her carefully, at the clothes, and the gloves, and the cheap little hat and the dishwater hands, and I knew this was the same old story. A burning conviction, based on nothing but wild dreams. Scrimping and saving to come to Broadway to have a try. Bitter disillusionment, scant funds evaporating, finally a search for any kind of work to keep food in the stomach, hope in the heart.

I sighed again.

She interpreted that sigh correctly and turned to leave. My telephone rang at that moment. Marty Silvers, the agent, was on the other end.

"Tad, the kid you signed to play the maid this afternoon wants a release. She's gotten a chance to take a lead in a summer stock troupe. Will you release her?"

"Sure, can you get me another, Marty?"

I looked up from the telephone for an instant. Sue Heyvard was in the outer office, walking to the door. Something happened to my usually cold judgment.

"Wait a minute, Marty," I said.

"Hey," I called after her, "Hey you, come back!"

Sue Heyvard, startled, knees a-tremble, turned and came back. She seemed to be holding her breath and her eyes were half closed.

"Never mind, Marty," I said. "I've got a kid now who'll fit the part."

I hung up and looked at her.

"Think you can handle a walk-on bit with about twelve lines as a maid, a servant, in my new show?" I growled.

"Oh, Mr. Barrow," she said. "Oh, Mr. Barrow. Oh, Mr. Barrow!" And then the tears, which never would have been shed in defeat, came forth unchecked to greet her first triumph....

HOUSE OF CHAOS opened in August and was a smash

hit. Sue Heyvard was drawing down twenty dollars a week as the

maid. I don't believe any actress ever concentrated more on

twelve lines than she did. The play was so generously received

that Hollywood was on the wire long distance the morning after

the opening, wanting to buy it and to have Toby Evans play the

lead in the picture whenever our run was finished.

One critic said: "Every person in the cast, including the pinch-featured little gamin who plays the maid, is unbelievably real."

It was the first review Sue Heyvard got. It thrilled her to the bottom of her shoes, even though her name wasn't mentioned, and the description of her was not exactly flattering.

"You know, Tad," Toby Evans, who had the lead, said once, "that thin-faced little Heyvard girl believes the entire play is real, and that she actually is the maid. Honestly, when I see her offstage, I sometimes forget myself to the extent of asking her to fix up a tray of cocktails!"

Which was the truth. Sue seemed almost in a trance during the entire run. Even offstage she acted like the maid she was supposed to be in the show. She was literally living her tiny role, polishing it day after day, as if it were tremendously important, vitally essential, that she be the maid.

House of Chaos, after the holiday run ended in January, went on the road. I was getting a new production ready in the meantime. And for some reason I kept Sue Heyvard behind in New York to take a fairly minor role in it.

Sue got the part of a snobbish sister of a debutante in the new production. The play, which had but a minor success, was, The Money Mummies. I don't blame you if you don't recall it. With many more than a dozen lines, this time, and drawing down the huge sum of thirty-five bucks a week for her efforts, Sue walked away with the majority of plaudits in the first night reviews of, The Money Mummies.

"Sue Heyvard, in the relatively unimportant role of Glenda, snobbish sister of the heroine," wrote Burns Mantle, "is so convincingly irritating you want to wait at the stage door when the play is over to slap her snooty map. Her work is the high point in a run-of-the-mill production."

The show lasted a two months run before it closed. And it was just as well for Sue that it closed so soon. The entire cast would have cheerfully broken her neck by the end of that time. For she insisted on living her unpleasant character assignment off the stage as well as on. In short, for two months, Sue Heyvard was actually the damnedest snob I have ever encountered.

"Really, Tad," Sue replied when I hinted she wasn't endearing herself to the cast at the end of a month, "they're such a stupid, boring lot of cattle!"

I had almost exploded. Then I'd noticed the almost glazed expression in her eyes, and got my first inkling as to what a hell of a great actress Sue Heyvard was turning into. So I kept my mouth shut until the show closed. And sure enough, Sue was herself again after the last curtain on The Money Mummies.

THAT was at the start of the summer of 1938. One year

later. So you can see how far Sue had traveled in that mere year,

when I tell you that I was willing to take a chance on her

ability to carry a strong supporting part in my next production,

a thing called, This Thy Morning, which was a terrific

script around the struggle of the southern poor whites against

labor enslavement.

We opened on Broadway in September. Maybe it was the fact that hell broke loose in Europe that month and year, or maybe it was because plays with a social message too often are ignored. At any rate, we closed three months later, lucky to break even and meet expenses on the play.

Sue Heyvard, at seventy-five dollars a week, had the role of a young school teacher who fights against tremendous odds to better the miserable working conditions of the people in her dirt-poor community. As I said, it was a supporting part, but it was strong. So strong that Sue, with the magnificent portrayal she turned in, made every critic in New York sit up and take notice. There were no reviews of her work that didn't drool plaudits for her performance.

But I don't think Sue paid particular attention to the applause this time. For once again she was utterly wrapped up in her role. That's right, offstage as well as on.

When newspapermen spotted her in a picket line before a garment factory in Jersey, the wise birds screamed that it was a none-too-original publicity stunt to draw attention to the show.

But I was in charge of the publicity, and it was no idea of mine. And when I talked to Sue about it, she had that glazed, in-another-world expression on her face, and she couldn't seem to comprehend what I was driving at.

I knew it hadn't been her idea to get some newsprint for herself. She just wasn't the sort.

Her social fervor, so help me, was nothing but the result of her utter transformation into the character she was portraying before the footlights every evening.

By the time This Thy Morning, had closed, Sue had received four offers to take Hollywood screen tests. As incredible as it seemed to me, people were saying that her pinched, eager little face with that long straight black hair and those wonderfully wide and vital brown eyes gave her striking beauty!

People were saying it so often I was beginning to realize they were right. It didn't strike you until you'd seen her a while. Taken separately, all Sue's facial characteristics were odd and unattractive; but together they combined to give her a rich, warm, vital, human beauty that was undeniable.

OF course, when This Thy Morning closed, Sue was

once again herself. On my advice, she held off on the screen test

offers, and turned down bids to go into several other productions

which I didn't figure would advance her any.

"You're set for star billing in your next show, Sue," I told her. "And the minute I hear of a vehicle that suits you, it's yours, at three hundred a week."

Her wide brown eyes went even wider at this, and she smiled in that peculiar, heart-warming, unaffected way she had.

"Gosh, Tad, that sounds really wonderful. Of course, I won't do anything you'd advise me against," she said.

"Swell," I said, and added jokingly, "because I'd hate to think of your taking the role of a murderess, for example, with the way you hurl yourself into a characterization. Why, I bet you'd bump off half the population of New York before the play's run was over."

Sue smiled, and then her expression became serious.

"You know, Tad," she declared earnestly, "I imagine a lot of people think I affect a dreadfully 'ham' pose during a run. But honestly, I don't quite know what does happen to me when I take a new role. Perhaps I go a little overboard mentally, but I seem to feel almost as if someone else, the character I'm trying to be, takes complete control of me. I don't know if I could do anything about it if I tried."

From any other actress in the world, I wouldn't have accepted that explanation as anything but temperamental guff, the sort of stuff you read in the frowziest press releases in the screen mags. But I had seen Sue, and I knew her. It was strictly on the level. The kid wasn't suggesting publicity releases....

FOR the rest of the winter season I searched for possible

plays in which to feature Sue. But I was being very particular,

wanting to give the kid the benefit of a smash script in her

first starring role, and nothing seemed quite good enough.

But in March, Melvin Gardner—who, ironically enough, had authored the first show in which Sue had the bit part of a maid—sent in a play he'd finished on his Maryland farm after three months' intensive work.

It was a spine-thrilling historical piece. It had a third act that some day will be preserved to be compared with the best that Shakespeare ever did. And it was tailor-made to Sue Heyvard.

I called in Sue immediately.

"Can you speak French?" I kidded her.

"Why, no, of course not, Tad" she said puzzled.

Then I dropped the kidding.

"You don't have to," I laughed, "so don't look so worried. But I've found the script for you. And you are going to play a French girl."

"A French girl?"

"A very celebrated French girl," I said. I pulled the manuscript of the play from my desk. "A damsel history refers to as Joan of Arc. You are to be Joan. The play is based around the most dramatic peak of her life. Here, read me Joan's part in the last scene of the third act."

Sue found the scene and started, hesitantly, to read her lines. She caught the swing, the rhythmic drama, inside of a few sentences.

We were in a paper-littered theatrical office. It was a bright spring New York afternoon. But I forgot everything, absolutely everything, while I listened to that girl read. I got a lump in my throat and there were tears in my eyes, while my spine was goose-flesh. God, how she filled that role!

And three months later, in the Fall of '39, I stood in the wings of the packed Broadway opening night of Joan For Freedom, listening to the thunderous applause roll deafeningly across the footlights as the audience called again, and again, and again for Sue Heyvard, as Joan of Arc, to take curtain bows. Even the stage hands and electricians had choked throats and watery eyes, and none of them ashamed of it.

Joan For Freedom was sold out six months in advance at the box office. You had to see your Senator to get a ticket. And night after night, Sue, as Joan of Arc, knelt before a hushed and tensed audience and delivered her heart-tearing plea for France. It was acting that occurs once in a hundred years of theater, occurring every night.

The lines were terrific, there was no doubt of that. They'd have been splendid delivered by practically any actress. But what Sue added to them was incredible.

AND as the first few months went by, it became alarmingly

apparent that the role was taking as much from Sue as she was

putting into it. For she was Joan, offstage as well as on. And

the deep, burning intensity of her portrayal was so genuine it

was frightening.

I was worried. I didn't want the kid torn into a nervous breakdown. I tried to talk to her, tried to break through the wall she'd built around her. The wall that was the very heart and soul of Joan of Paris.

It was little use, however, for she had never been more deeply buried in a role. The best I could do was to see that she was kept under careful supervision while she was offstage, and make certain that her health was watched carefully. This scheme seemed to work satisfactorily for the first nine months of the run.

But it was shortly after that my fears became facts. My warning came in the form of a telephone call from Sue's maid. I had told her to get in touch with me the instant anything out of the way happened in regard to her mistress.

"Miss Heyvard left her apartment half an hour ago in a more than usually strange emotional state," the maid said almost weepingly. "I told the chauffeur to call me the moment he took her where she wanted to go, Mr. Barrow," the excited servant declared. "He just called to say he dropped her off at a tiny French church. He's waiting outside for her, but he says she seems in a trance and spoke to him in what he believes is French!"

Hastily, I got the address from the bewildered woman and was in a cab a few minutes later, speeding to that church. Over and over in my mind was running the fact that Sue, according to this, had been speaking to her chauffeur in a language about which she knew absolutely nothing. It was impossible. Perhaps the chauffeur had let his imagination run wild on him. Undoubtedly the kid had cracked, and had more than likely been delirious.

I was frantic when I climbed out of the cab in front of the tiny French church. Sue's limousine was parked just ahead of me, and the chauffeur stood at the curb, nervously smoking a cigarette.

"She's inside, Mr. Barrow," he said excitedly.

I went up the steps of the church at a most irreverent pace. At the door I stopped. The tiny little place of worship was deserted save for Sue.

She knelt in a pew near the back. Her face was more intensely beautiful than I had ever seen it. Tears rolled down her cheeks. Her lips were moving slowly.

I went up quietly beside her, but she seemed not to notice me. Her voice was coming in a half whisper. The words she spoke were in French.

"Sue," I said gently, touching her arm.

Her lips continued to move. She seemed oblivious of my presence. My knowledge of French is extremely sketchy. But I was aware of one thing about the words she spoke instantly. They were the lines of the dramatic final scene from the play, spoken in the tongue of the original Joan of Paris!

"Sue," I said. This time I put my hand on her arm. Unprotesting, she rose. In the look she gave me there was no recognition. I helped her from the church. Outside, I gave her chauffeur the address of the best hospital in New York....

"A BREAKDOWN, of course," the doctors told me two hours later.

"Miss Heyvard will need rest, lots of it. But we would advise you

to leave her under our observation for the next several

days."

When I was finally assured that I could be of no further help, I left, cursing myself for a stupid slave-driving swine. I should have kept Sue under more careful scrutiny. I might have prevented this.

I'LL never forget the frantic afternoon I spent readying

Sue's understudy for the role of Joan. The show had to go on,

even without its great actress.

That was not only a staggering day for me, but also a tragic day for the world itself. History will remember it as the day that France fell beneath the crushing boots of Germany. I remember that I was vaguely aware of the headlines screaming this as I finally started back across town to the hospital where Sue was.

But by the time I arrived at the hospital, Sue was gone!

I shall never forget the horror and sickening self-accusation I suffered. Or the astonished, frantic protestations of the doctors that they had put her under hypodermics and that it wouldn't have been possible for her to slip from her bed and from the hospital.

But she was gone, and there was no doubt of that. And her clothes were gone from the closet of her room.

Frantically, haggardly, I spent the next hours, the next days, the next weeks in search for Sue Heyvard. I kept the story of her disappearance from the papers, even though I was forced to release the admission that she'd suffered a nervous breakdown.

The police could find no trace. I put the best private detective agency in town on the case. They, too, were helpless. There was only one shred of evidence gathered that pointed even vaguely to her trail. And that was presented by a longshoreman who'd been one of a crew unloading a tramp steamer flying a French flag at the cargo docks the afternoon of Sue's disappearance.

"Yes," said the longshoreman, after being shown nine or ten photographs of Sue Heyvard, "I think that might be the girl I seen go aboard the French ship late in the afternoon, shortly before it sailed."

"You didn't see her leave the ship?" he was asked.

"I was around the rest of the day. I didn't see her come off the ship once she went aboard."

Shipping authorities knew a little about that French cargo ship, but not as much as you might expect. Yes, it was a French ship. It's captain undoubtedly decided, on hearing what had happened to his government that day, to leave New York before his craft could be seized to be held for the duration.

No, the French ship carried no wireless. It's destination was suggested as a port in what was soon to become Occupied France.

Those who knew of Sue's tragic disappearance said I was mad to think that she was aboard that vessel. But I had checked her bank, and she'd taken a large amount of cash from it late in the afternoon of her appearance. A cargo captain could be persuaded to close his eyes to an extra passenger without a passport, for enough cash.

Of course you know Sue was never found. I called off the search shortly after that, knowing deep inside me that I'd seen her for the last time in, well, in a long, long time to come....

THERE was only one person to whom I told this story. He

gave it more than sympathetic attention. He was Doctor Stephan

Zeider, the eminent Dutch psychologist. He made me repeat the

story of Sue Heyvard again and again, as if he were committing

every last detail to memory.

Then he closed his eyes, made a profound steeple of his fingers and confirmed my growing conviction.

"Of course," he declared, "there is no doubt but that she is Joan of Arc. The human mind is capable of many mysterious things, friend Barrow. Its powers have never been fully explored. The girl spoke French in that tiny church, and yet she knew not a word of it, actually. But it was the tongue of Joan, and she was Joan, crying for the people of France, vowing vengeance for her beloved people, just as Joan did centuries before her."

AT my elbow as I write this, I have a late copy of a national

weekly magazine. Its dateline shows that it came from the press

some sixteen to eighteen months after Sue Heyvard disappeared.

Featured as the lead story of this magazine is an article dealing

with the growing and tremendous forces of revolt and unrest in

the countries of Occupied Europe. A small part of the article has

come to my attention. I'll pass it on to you as I have passed on

the rest of the evidence.

"And though the governments of these conquered nations have been carefully weeded of dangerous leaders, in the ranks of the underground revolt, new leaders have arisen. Among these new leaders none is so romantically appealing as the pinch-faced, yet beautiful Parisian girl they call Joan d'Arc.

"It is this mysterious Joan who has organized the terrifying system of revenge and harassment of the Nazi forces of occupation. None know her origin, none care. She appeared in the darkest hour of France, like another Joan, centuries before her. They say the price placed on her head by the Gestapo is the highest in France. We are inclined to believe it."

AND so it is that I know the chances of my ever seeing

Sue again are slim. But I think often about those wide brown

incredibly vital eyes belonging to Sue Heyvard, the girl who is

Joan. And sometimes I pray that the curtain will finally fall on

her greatest role.

And then Sue Heyvard will return, and perhaps Broadway will again applaud the most incredibly real actress I have ever seen behind the footlights.

For, to repeat, I've seen them all.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.