RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

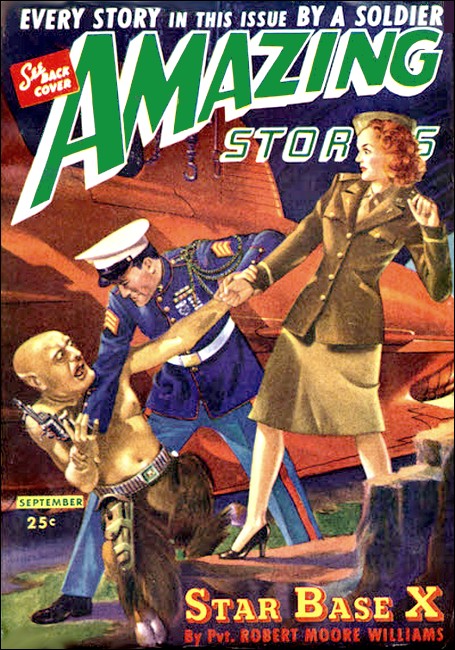

Amazing Stories, September 1944, with "Private Prune Speaking"

Private Prune pressed palsied palms against the arm rests—and waited.

They pulled the wrong switch and transformed

Private Prune into an

oracular sounding board. It made trouble for everyone—including the Axis!

PERCIVAL PRUNE was never quite certain how he had wound up in the Army. This fuzzy retrospect, however, did not make Prune unique among his comrades in the service. Many of them were just as puzzled about that as he.

What did make Prune's case somewhat distinctive was the fact that on twenty-three occasions previous to his being drafted into service, Private Percival Prune had tried—quite unsuccessfully—to volunteer his services to the Army, the Coast Guard, the Marines, the Navy, and once, by typical mistake, to the Women's Auxiliary. Each of these units had turned down Prune cold, had told him to return only in case there was fighting in the streets of Boston.

What had gone awry with the usual smooth machinations of the draft board in Percival Prune's district, no one would ever know. But it may be presumed that some official, suffering the after-effects of a bad night, had dipped into the wrong file one dismal morning to pull forth Prune's card. The rest had been mere routine.

A small, watery-eyed, frightened, horse-faced Percival Prune had reported to Camp Carroll one bleak December morn for induction, scarcely twenty days after the first mistake had been made. That much is known as to the "how" of Prune's entrance into the United States Army.

At Camp Carroll, consequently, the Army career of Private Prune began. And at Camp Carroll, faced with his first interview, Prune bared the drab details of his scarcely adequate background.

"What was your occupation?" the interviewer asked pleasantly.

"I—ah—I tuned harps," said Prune.

The classifier had solemnly entered this on Prune's Form 20. He then learned Prune's weekly wages—a modest sum, modestly stated—the fact that he was unmarried, entirely without relations, to his knowledge, and that he was thirty-six years old, did not snore, wet his bed, or suffer fits.

"What do you like best?" asked the classifier in an at-your-ease tone.

Prune, going through the agonies of hell at the fear that he might be rejected, answered, "Olives."

The interviewer hadn't delved further into this. He merely added it to the Form 20. Prune, who hadn't realized that he'd spoken the first foolish word that entered his head, let it pass.

The classifier was human, and he was tired. His job wasn't, at best, an exciting one. Here he had what might, under the most favorable of circumstances, be termed an inductee who tuned harps, liked olives, and looked like a refugee from a red corpuscle. What in the hell was he supposed to do with a guy like this?

The interviewer looked at Prune's Army IQ grade, hoping to find some solace there. It was disappointingly average. He sighed, and stared for a moment into the eager, pleading eyes of Percival Prune.

It was then that the classifier got his idea for his mad prank. He smiled thinly, began busily scratching a number of statements and dates onto Prune's record card. He looked up during the proceedings, once to ask:

"You want action, honest-to-God combat?"

Prune had nodded, too thrilled to speak.

And the classifier had continued to make his mysterious code markings on Prune's Form 20, his face now bathed in a grin of sheer, malicious deviltry.

When he finished, he looked up and said, "Go back to your barracks, Private Prune. You can count on shipment from this camp in less than a week. You're in the Air Corps."

What he didn't tell Prune was merely that he had classified him as "611," aerial gunner, had altered dates and records on Prune's form card to make it appear as though he had been through a gunnery school and won his wings as a marksman of the sky.

But the magic words that Percival Prune had heard, "You're in the Air Corps," were enough to make him oblivious to anything but the fact that he had achieved the most incredibly wild, ecstatically wonderful, of all his dream wishes.

Private Percival Prune was a member of the Army Air Forces!

THE classification wag had predicted the day of Private

Prune's departure from Camp Carroll almost to the hour. And in

less than a week after his entrance into the Army, Prune found

himself heading for the never quiet acres of Penning Field, where

trained the 300th Bombardment Group. Obviously, the shipping

department had been surprised to find that a certain Private

Prune, an aerial gunner, no less, had somehow mistakenly been

sent to Camp Carroll and barracked with a group of raw recruits.

And just as obviously, they had taken hasty pains to rectify this

mistake by shipping him off to an Air Corps bombardment unit

where he belonged. They were hardly to blame for his error. They

had only Prune's doctored Form 20 to go by.

"So your name is Prune, eh?" said First Sergeant Rice of the 300th Bombardment Group's Squadron C, several days later.

"Y-y-yessir," said Prune.

First Sergeant Rice blinked at this. He was about to snarl an objection at the use of "sir" in addressing him, then changed his mind. Getting such a tag from an aerial gunner—one of the most cocky and highly arrogant species of life known to man, on Rice's book—was so incomprehensible as to be treated with awe. Incoming aerial gunners usually wore a to-hell-with-you look when being welcomed by First Sergeant Rice. They almost invariably looked and acted as if they wanted to tell him how they preferred to have the squadron run during their stay there. It came to the sergeant, quite suddenly, that he might be having his leg pulled in some subtle fashion. He glowered, just to keep in practice.

"Are you being funny?"

Private Prune gulped, his Adam's apple riding visibly up and down his scrawny throat.

"N-n-n-no sir," he said.

The repetition of that last word was enough to convince Sergeant Rice that his worst suspicions had foundations. Here was a subtle gagster. A smart operator. A cocky gunner who was trying, in a silkily smooth way, to make an ass of him by innuendo. First Sergeant Rice bristled.

"Okay, bright boy. I see you're here as a replacement gunner. As soon as you can get your bags over to Barracks Ninety, you can replace a man on K.P. You'll find the mess hall half a block to the east of the barracks. Don't think you can stay wise around here and get along."

A dazed and bewildered Percival Prune found a bed for himself in the upper bay of Barracks Ninety, left his barracks bags there as a claim, and hurried to the mess hall. On his arrival there, he found that First Sergeant Rice had telephoned, and that the mess was expecting Private Prune.

"Okay, you," said the mess supervisor. "Get over there on the China Clipper."

Prune's heart leaped. China Clipper! Then he looked about, baffled. But this was a mess hall; there was no visible evidence of a huge, ocean-spanning airplane—

"Hey, you," said the mess sergeant. "Get movin'."

Prune continued to look bewildered.

"Ain't you never been on K.P. before?" the mess sergeant demanded incredulously. Private Prune shook his head. The mess sergeant shook his head—in sheer wonder. Then a delighted grin came to his face.

"Well, I'm damned. Here's a gunner who's never had no K.P. How long you been in this army, bud?"

"A week," answered Prune truthfully.

"Don't get wise with me, bud," said the mess sergeant. "This ain't no place for jokes. This ain't no vaudeville stage. C'mere. I'll show you the China Clipper."

He took Private Prune ungently by the arm, led him around a corner to a small room which seemed utterly enshrouded by steam. There were hoarse cries from within the room, staunch curses and the clatter of much dishware.

"There's your Clipper, bud," said the mess sergeant.

Private Prune was now able to discern a huge, frightening machine through the steam vapors. It gobbled up trays and cups and bowls like an ogre, sucking them into its secret stomach, then spewing them forth red-hot, steamy and sterilized.

"You—you mean it's a dishwashing machine?" bleated Prune.

"Now you're on the beam," said the mess sergeant. "Hey, Kletzki," he yelled. A big-shouldered Slav emerged, perspiring from the steam. "Put this guy to work, and see that he don't try to lie down on yuh."

"Yah," said Kletzki, and pulled Private Prune into the room....

IT was early afternoon when Percival Prune returned,

weary-footed, to his barracks. It should have been early evening,

for the mess hall was still going and there was still another

meal to serve before closing. But the irate mess sergeant had

sent Prune packing after seventy-five cups, forty-three bowls,

and eighteen pitchers had been broken. There had also been a

matter of fifty-two mangled metal trays. The big gears of the

China Clipper still contained shreds of the sleeve of Private

Prune which had been caught there.

"If I keep you around another minute you'll blow up the joint," the mess sergeant had thundered. Then he had made Prune sign an extensive statement of charges, and had evicted him.

In his barracks, Prune sat down on the edge of his bunk and wondered what had gone wrong. He had been frantically willing, the very essence of eagerness. He had worked like mad, obeying every inflection of every command of Pusher Kletzki's voice. But everything had seemed to go awry. Private Prune was sad. He had messed up his first assigned duties at his new post. He wondered if it would do any good to see the first sergeant, to apologize, to try to explain, to beg for another chance. Then he decided that it might not be prudent. First Sergeant Rice had seemed to be a man of explosive temperament. He might, if pressed too much, throw Private Prune right out of the Army. He shuddered at that thought, then slowly began to unpack his things and arrange them the way he'd been taught at Camp Carroll.

He was rummaging through his barracks bags when the lieutenant came in. He wasn't aware of the young officer's presence until he heard a voice behind him asking, "New here, soldier?"

Prune turned, saw the young lieutenant, and his knees almost gave out from under him. This was the first officer to address him personally since he had been in the army.

"Y-y-yes sir," said Prune.

"Gunner?" asked the lieutenant.

Prune remembered having been called a gunner. He supposed that he was.

"Y-y-yes sir."

"I'm Lieutenant Ford, junior executive officer for Squadron C," said the officer. "I think you'll find our outfit pretty regular, soldier, just as long as you keep your nose clean and stay on the beam."

Private Prune almost went limp with gratitude. He smiled timidly, eyes watery.

"Better polish your brass," the lieutenant said. "Those shoes could do with a better shine. Your blouse is hung incorrectly, and you're minus patches on three shirts." His voice had suddenly become cold, full of authority. He glanced at Prune's barracks bags.

"That all the gear you have?" he asked.

Prune gulped, nodded.

"No B-4 bag, no flight pack?"

"N-n-no sir," said Prune.

"Never issued them?" The lieutenant seemed surprised.

"N-no sir," said Prune.

"Where was your last station? They should have attended to that at your last station."

"Camp Carroll, sir." Prune managed a reply without faltering.

"But that's not an Air Base. That's a replacement center for inductees, recruits."

"Yes, sir," gulped Prune. "I've only been in the Army six days."

This knocked the lieutenant back on his heels.

"But you told me you were a gunner!" he said indignantly.

"I only told you what they told me, sir," said Prune.

"They told you? Who's they?"

"The first sergeant, sir," Prune answered. "And the interviewer who put me in the Air Corps."

Young Lieutenant Ford's face was grave, his lips tight. Here, plainly, was a mess of some sort. He tried to recall how they had told him to handle messes of this sort back in Officer Candidate School. He couldn't recall anything beyond "misclassifications." It would be best to bring the matter before his senior officer.

"You come with me," he told Prune sternly. "There's something screwy here. We're going to see Captain Talbot."

Percival Prune swallowed hard. Tears came to his eyes. A deep, sickening dread filled his soul. He was trapped! He had been discovered! Now they were going to throw him out of the Army! His lips trembled as he tried to phrase a never spoken plea for clemency.

"Come along," said Lieutenant Ford. "We're going to get to the bottom of all this."

Private Prune, like a gallery painting of an early Christian martyr, followed docilely after the lieutenant....

CAPTAIN EUSTACE TALBOT, Senior Executive Officer of Squadron C, 300th Bombardment Group, was a short, broad-shouldered, aggressive man in his middle forties. His hair was graying faintly at the temples, and his elegant, clipped moustache had just the proper tinge, of gray in it to make a perfect contrast with his deeply tanned, glowing complexion.

Captain Talbot had been a washing-machine salesman before entering the Air Corps as an administrative officer, but you would never know it now. He looked, spoke, and acted with the terse, clipped drive of a man who is "Old Army." He sometimes regretted that he wasn't in the cavalry, so that he could slap a swagger stick against gleaming knee-high riding boots.

Captain Talbot was, at the moment, engaged in a highly important conference. In his office was gathered a collection of military and civilian authority that would have floored the average officer.

Colonel Priddy, lean, sharp-featured, weather-beaten, acid-tongued commanding officer of Penning Field was there. So was a Major Branscome, a Lieutenant Colonel Fisher, a Colonel Hammer, and a pair of serious-miened civilians whose names were neon-lighted in the streets of scientific achievement.

"All our laboratory tests have been perfect," one of the civilian scientists was saying. "We need, now, only to put our discovery into operational flying practice. If everything goes as we expect it to, gentleman, our discovery will make radar seem like something concocted by a child."

"You will find Captain Talbot and the men of his squadron highly cooperative," rasped Colonel Priddy.

Captain Talbot cleared his throat modestly. "I am honored that our squadron was chosen to aid in these—"

Colonel Priddy cut him off. "It is ridiculous to remind you gentlemen that these experiments will be matters of the utmost secrecy. Never forget that fact."

"Our device," said one of the scientists, "must, of course, be first attuned to the climate and altitude of this locality. Of course, we will need a man to serve as a—ah—guinea pig, in this adjustment. One of your enlisted men will do. It's nothing of consequence. Just a routine alteration. After that, we'll be able to install the equipment in a dozen planes of your squadron, and carry on from there."

Captain Talbot, eager to show himself one hundred percent on the ball, stepped quickly to the door of his office, opened it, stuck his handsome head out into the orderly-room.

"Sergeant Rice," boomed Talbot. And then he saw Lieutenant Ford waiting in the corner, and realized that the lieutenant had in tow with him a small, frightened, trembling soldier.

"Yes, sir," said Sergeant Rice, from the other corner.

"Never mind, Sergeant," said Captain Talbot. He fixed a gleaming eye on Lieutenant Ford.

"Lieutenant," the Captain said, "please tell the soldier sitting beside your desk to come in here at once."

Lieutenant Ford looked surprised, then somewhat shocked. He opened his mouth to say something by way of explaining Private Prune's presence, and then recalled that his was not to question why. He turned to Private Percival Prune.

"Soldier, go into Captain Talbot's office, on the double."

PRUNE'S jaw went slack. Again his knees felt as insecure as

wet noodles. His heart hammered wildly. This was worse than he

had feared. The captain, with one swift, shrewd glance, had

detected his presence as alien to military surroundings, and had

demanded that he be brought before him instantly. Private Prune

closed his eyes. He had awful visions of being taken out on a

parade ground, snipped of his brass buttons while the drums

rolled ominously. Perhaps he'd be shot, as an afterthought.

Lieutenant Ford's voice brought Prune out of his nightmare of speculation.

"Well, hurry up!"

Percival Prune lurched to his feet. He started for the captain's office, remembered that the lieutenant had said on the double, tried to move more quickly, and began a long, sickening stumble that ended only when he collided with the door of the captain's office. It was standing slightly ajar.

Prune's scant weight was enough to give the door inward momentum. And the door's betrayal by refusing to support him resulted in Prune's being pitched headlong into the office of Captain Talbot.

"Well, I must say!" someone snorted.

From his position on the floor of Captain Talbot's office, Private Prune looked sickly upward. Gazing down at him, a circle of mingled emotions, were Captain Talbot, a colonel, a lieutenant colonel, a major, and two very eminent-looking civilians.

Prune scrambled wildly to his feet and began saluting like a windmill.

"Private Prune reporting as ordered. Private Prune, reporting as ordered. Private Prune, reporting as ordered," he squeaked hysterically.

"Turn off that phonograph," said Colonel Priddy coldly to Captain Talbot. "And make him stop waving his right arm in what he imagines to be a salute."

Captain Talbot didn't have to tell Prune. The acidly spoken remark of the colonel had been enough. Prune stopped squeaking his formulized entrance line, brought his waving right hand to his side, and assumed a rigid, ridiculous posture of attention.

There was little that Captain Talbot could say, save, "Here is a man you gentleman can use for your adjustments." He glared hard at Prune, for that little soldier had utterly ruined the entire swift, military pattern of the picture.

"Here is a man," Colonel Priddy said acidly, "who can obviously use a few adjustments."

The civilians laughed. Captain Talbot crimsoned, and Major Hammer, anxious to be on the good side of his senior officer and C.O., came in with a hearty, poorly-timed chuckle.

"We might as well get started, then," said one of the civilian scientists. He looked at Prune curiously, then turned to his companion.

"Yes," he said, "we might as well."

"Go along with them, soldier," Captain Talbot said to Prune. "You are to help them out on some adjustments."

Private Prune, deep in his own crimson hell, looked up bleakly, piteously.

"Y-y-y-yessir," he said....

THE building to which Percival Prune was taken by the two

eminent civilians, was a large, modern structure just inside an

area marked "Restricted" by numerous sign posts and patrolled by

two armed guards.

The civilians showed their passes to the guards, and Prune showed the pass which had been given him. When they entered the building Prune's mental state bordered on coma, for his mind was filled only by the hideous blunders he had made in entering the captain's office, the confusion he had momentarily caused, and the gloomy certainty that this was now surely enough to result in his getting fired from the Army.

They took Prune to a large room containing a myriad of electrical equipment. All sorts of strange gadgets filled the place, but Prune, sickly worried, utterly disconsolate, paid no attention to his surroundings. They told him to sit down. He sat down. They told him to make himself comfortable while they got ready. He did his best to look like a man who has made himself comfortable.

After an interval which might have been five minutes or might have been thirty-five, they bade Prune to rise and take the seat they had prepared for him.

Prune moved from the straight-backed chair in which he had been sitting to the chair they indicated. He was barely conscious of the fact that it was a highly unusual chair—a chair containing wires, and coils, and lights, and looking like something in which people were electrocuted. Prune was too deeply engrossed in his own morbid fancies to pay more than fleeting attention to any of this.

They attached a lead plate to Prune's wrist, after first wrapping the wrist with rubber bandaging. Then they wound more rubber bandaging over the plate. They repeated this process on his other wrist, then on both his ankles.

Each lead plate had a wire running from it to a machine on the right of the chair. The machine was a lacework of switches and small, flickering light bulbs.

Both gentlemen appraised the wiring job they had done on Prune. They seemed satisfied.

"Might as well throw the switch," said one.

The other nodded and moved over to the complicated switch panel.

"Ready?" he asked his contemporary.

"Now," said the other scientist.

The switch closed with a brisk snap; the board began to crackle; sparks flew; a humming filled the room.

Percival Prune came out of his daze. He screeched wildly, tried to rise from the chair, as if it had suddenly become filled with very sharp tacks.

"Turn it off," the man farthest from the switchboard yelled. "You've thrown the wrong switch!"

THE switch was turned off promptly.

The sparks stopped, the humming whined off into silence. Both scientists turned slowly, fearfully, to the subject in the wired chair.

Private Percival Prune was out cold. His head was slumped forward on his chest, his body sagged limply in the chair.

"My God!" one of them gasped.

"Have we——?"

The other had stepped swiftly to the chair, was leaning forward, his ear against Prune's frail chest.

"No," he announced with considerable relief. "No. We haven't killed the poor man. His heart is still beating strongly, though with shock flutter. But we certainly knocked him out cold."

"Too bad," said his companion vaguely. "We'll have to get another man. Don't make that mistake again."

"I didn't look when I reached for the switch panel. We'd better call for an ambulance, don't you think?"

It was at that moment that Prune sat up groggily.

"It's a great honor, my squadron being selected for these experimental tests," he said.

Both scientists whirled to face him.

"You all right, man?" they demanded.

Prune looked at them dazedly, and nodded.

"Y-y-yes," he managed. "I'm just fine. Can I go now?"

The scientists exchanged puzzled glances.

"That's odd," one said.

"Did you notice it, too?" asked the other.

"Notice what?" quavered Prune.

"Your voice," said the first scientist. "Repeat what you said when you regained consciousness a moment ago."

"I'm fine. Can I go now?" Prune repeated obediently.

"But that isn't what you said. Repeat what you said about these experimental tests being a great honor for your squadron."

Prune looked dismayed.

"But, please, I don't recall having said anything like that," he faltered.

The scientists exchanged frowns. "Of course you did," said the first. "Of course he did," said the second.

Prune was seized by a sudden panic. He had done something wrong again, or said something wrong.

"I—I don't understand you. Can I go now?"

"I'd swear it sounded like Talbot," said the first scientist. "The captain's voice is very distinctive. I couldn't mistake it."

"I agree with you," said the second. "That's what startled me. I'd have sworn Captain Talbot was here, when the soldier said that."

"Please," said Percival Prune, "can I go now?"

They both looked at him a moment.

"It isn't important," one shrugged. "We'd better get on with this adjustment. We'll need another man."

"Please," wailed Private Prune, "can I go now?"

"Oh, yes. Yes. Certainly, my good man. You may leave. I'll call Captain Talbot for another man."

Panic again gnawed sharply at Percival Prune.

"Wasn't I satisfactory?"

Both scientists smiled. One said. "Oh, eminently. We need another man, however. You've had enough for today."

They unwound Private Prune, helped him from the chair, escorted him to the door, thanked him profusely.

"Damnedest thing," said one, when Prune had gone. "I'd swear that he sounded exactly like his captain when he came out of his shock."

"So would I," the other agreed. "Odd, isn't it?"

They sighed, and went back to their work....

PRIVATE PRUNE did not want to return to his squadron orderly-room, for he felt certain that Lieutenant Ford would be there, impatient to get on with the business of ousting Prune from the Army. There, too, would be glowering First Sergeant Rice, and Captain Talbot, whom Percival had disgraced in front of so many important senior officers.

Private Prune did not want to do so, but there was little else he could do without getting deeper into trouble.

On the steps of the squadron orderly-room, Prune paused to gather courage, and to rehearse his opening line, "Private Prune returning from detail," with which he intended to greet Lieutenant Ford.

Mentally, he repeated this phrase, then started to whisper it to himself.

"I'll have no more of that slam-bang inefficiency around here," an acid, rasping voice said very loudly.

Private Prune went rigid with fear. The voice was that of Colonel Priddy, Commander of Penning Field!

Slowly, Prune looked over his shoulder, to see if the colonel was coming up the steps. But there was no sign of that dignitary in view. Then he was probably in the orderly room. Prune quailed. He hadn't counted on having to face the commander of the post as well as Lieutenant Ford and Captain Talbot.

He squared his shoulders, took a deep breath, and stepped into the orderly-room.

"Attention!" bellowed the voice of First Sergeant Rice.

Prune looked around the orderly-room in dismay. Everyone there had popped to rigid attention, and all eyes were on the door through which Prune had just entered.

Prune popped frightenedly to attention, not daring to look behind him.

The room was stonily silent in that touching military tableau for fully half a minute.

Then Sergeant Rice broke the silence with a puzzled, "At ease!"

Everyone relaxed and went on with what he had been doing before Rice had called attention. Private Prune relaxed cautiously, fearfully. He looked at the door behind him. There was no one there.

First Sergeant Rice fixed Prune with an accusing glare.

"I thought I heard the colonel's voice out there, and when the door opened, I thought you were the colonel coming in. That's why I called attention," he snapped. "Did the Old Man walk on past the orderly-room, here?"

"I—I didn't see him," said Prune.

"That's funny," said Rice. Then, "What in the hell do you want?"

Stumblingly, Prune explained his presence.

"Lieutenant Ford had to go over to Ordnance. He won't be back until late tonight," said First Sergeant Rice. "He left word that you are to report to him here in the orderly room first thing tomorrow morning. I don't know what it's all about, but, brother, you're in hot water."

"R-r-really?" Prune gasped sickly.

"Ssssssssssss," said Rice, making a noise like steam. "But hot!"

The sick, frightened alarm on Prune's face made Rice feel much better. He grinned happily.

"Now get the hell outta here and go back to your barracks, Prune," he said, almost amiably.

Prune nodded miserably. Started to whisper his exit line. His lips moved.

"Sergeant Rice, come here at once!"

Captain Talbot's voice rang through the room.

The sergeant wheeled.

"Yes, sir," he said. Then he did a double take. Captain Talbot was nowhere to be seen. The door to his office was open, and that office was obviously empty. Nor was the squadron captain anywhere in the orderly-room office.

Private Percival Prune, his expression one of acute dismay, was backing slowly away in the direction of the door. First Sergeant Rice wheeled to face him again.

"Just a minute, Prune. Just a minute!"

PRUNE stood transfixed, frozen save for a pair of badly

knocking knees. "Did you say that?" Rice demanded.

"S-s-s-say what?" Prune croaked.

"Tell me to 'come here,' in Captain Talbot's voice, no less?" said Rice menacingly. "Did you?"

Prune was too badly frightened to speak. He shook his head in a wild negative.

Sergeant Rice frowned. He scratched his almost bald head. He glared doubtfully at Prune.

"Don't tell me I'm hearing voices," he snarled. "First the colonel's, then the captain's."

"May I go now?" begged Private Prune.

First Sergeant Rice gave Prune one last suspicious, searching glance. Then he nodded vaguely.

"Yeah, take off. But be in here first thing tomorrow morning."

Private Prune moved strickenly to the door. He was on the steps, taking deep breaths of fresh air, when Colonel Priddy came around the corner of the orderly-room.

Prune snapped rigidly to attention.

The colonel was coming up the steps on which Prune was standing. With him was the major who'd been at his side when Prune had stumbled in on Captain Talbot's conference an hour or so ago.

Private Prune tried to squeeze himself into nothingness as the colonel and the major stamped up the steps on which he stood. But he needn't have bothered. Neither paid the slightest attention to him. They moved indifferently past him to the door.

It was then that Prune heard Colonel Priddy exclaim:

"I'll have no more of this slam-bang inefficiency around here!"

Private Prune gulped, closed his eyes. Then the pair was past him, in the orderly-room, and the door was closed behind them. Percival Prune relaxed from his ram-rod pose of attention, grabbed the hand rail of the stairs for support.

Inside, he heard the startled voice of First Sergeant Rice calling attention.

Private Prune stood there, too weak to move, taking deep, fish-like gulps of air. He was very badly shaken. And it was at that instant that Captain Talbot appeared around the corner, face wrathful, and started for the steps where Prune stood.

Again Percival Prune hurled himself into a pose of rigid attention and tried to make himself invisible. Captain Talbot was alone. He brushed by Prune unseeingly, stormed into the orderly-room, leaving the door open.

Prune heard the captain's voice say:

"Sergeant Rice, come here at once!"

This was too much for Percival Prune. It filled his soul with a deep and sickening dread. He began to tremble like a man in the last stage of a tropical fever. Weakly, he made his way down the steps. He had to pause twice for rest on the way back to his barracks.

Percival Prune's heart, soul and mind were in a state of terrible turmoil. For there was in each of those parts of him, the small, positive, terrifying certainty that his vocal organs, his own tongue, had actually, on the occasions that misled Sergeant Rice, spoken in perfect imitation of Colonel Priddy and Captain Talbot.

And, what was somehow even more terrifying, the words that had come uncontrollably to his lips, in their voices, were repeated by the colonel and the captain themselves, to the letter and the most minute shading of inflection, less than five minutes later!

Private Prune was more than shaken. He was engulfed in a tidal wave of fear and eerie misery. Something was wrong. Something was radically wrong. Something inexplicable. Something over which he had no control.

He tried to whisper a reassurance to himself.

But he had no sooner made the effort to form words, than the voice of Colonel Priddy, rasping and acid, came from his lips.

"I'll damn soon get to the bottom of this," said Colonel Priddy's voice.

PRIVATE PRUNE clamped his jaws shut the moment those last

words left his lips.

For they had left his lips. They had been spoken by him—by Private Prune—by no one else. Spoken by him, even though the voice, inflection, and ringing anger of the words had all been unmistakably the property of Colonel Priddy.

And now Prune was certain of one dread fact.

The terrible something that had him in its power was, basically, a sort of mocking-bird-itis which made him a perfect, though unwitting, vocal mimic of others.

And it was something more than that, too. It was something quite beyond a mere inexplicable mimicry that permitted him to sound like people other than himself. It was something that enabled him to say their words in advance of their actual utterance!

The strange malady that beset Private Prune reached out, so to speak, like some advance-wave radio. It picked up the voices and words of others—voices saying words destined to be spoken minutes later—and broadcast them through the helpless vocal chords of Percival Prune.

What else could it be?

Percival Prune had volunteered for the Army more times than he could recall. But he wasn't completely stupid. He was smart enough, at least, as he stood there with the horror of his situation gradually dawning on him, to realize that he had somehow, some way, become a sort of combination of sounding board and ouija board. A sort of human Grand Canyon that produced echoes of sounds before the sounds were uttered.

All of which, Prune knew, was ridiculous. Impossible. Utterly beyond belief. But true.

So Prune stood there, trembling, not daring to think any further into the insidious complications that his dilemma might bring on.

His brow was beaded with sweat. He discovered this when he touched his hand to his forehead to find out if he had a fever. All the physical manifestations of his malady indicated that he was seriously ill.

Prune decided that he did not want to return to his barracks immediately. The barracks might be crowded. There might be other soldiers there. His affliction might reveal itself again—or, worse, his bodily tremors might be so obvious as to cause his comrades to send him off to the hospital.

He did not want to go to the hospital. In the hospital, if they couldn't cure him, they might throw him out of the Army.

Prune decided to go to the post exchange. He might be able to find a quiet corner there. He would be able to have a glass of milk and a ham sandwich and wrestle with his dread dilemma.

The orderly-room was between the PX and Prune's barracks. The window of Captain Talbot's office was open, and Prune passed beneath it on his way to the exchange.

It was then that he heard Colonel Priddy's voice coming from that office.

"I'll damn soon get to the bottom of this," Prune heard Priddy storm.

He shuddered, for the sentence had a grim familiarity. It was the same sentence spoken by Prune himself, in Priddy's voice, a few moments before....

SINCE most of the men on the base were at the moment on duty,

Percival Prune found the post exchange restaurant comparatively

deserted. And, realizing this as he gazed timidly around the

place, Prune felt sorry he hadn't gone to the barracks. It

wouldn't have been crowded after all. He might have been able to

climb into his bunk and cover himself with a blanket, cloistered

with his troubles and free from outside interference.

Nevertheless, the smell of food and the comfortable warmth of the place were factors strong enough to persuade Prune to stay at the PX long enough to have the sandwich and milk he had planned on.

He gave the restaurant counter another nervous glance, saw a completely deserted section at the far end, and moved down there for a seat.

The waitress who came up to take his order a moment later was blonde, red-lipped, and bored. She gave Prune the most casual of glances.

"What'll it be?"

Private Prune opened his mouth to give his order.

"Blat-At-Tat-Tat-Tat-Tat-Tat-Tat!"

The noise was sudden, deafening, and—to all in the PX—utterly terrifying. And it came from Prune's mouth.

It was the unmistakable, ear-splitting banging of a caliber .50 machine gun!

A sergeant, who'd been sitting peacefully in front of a cup of coffee on the other side of the counter a moment before, hurled himself to the floor with frantic urgency.

Several soldiers and three officers at the magazine counter in the far corner of the exchange duplicated the sergeant's instant reaction, madly crawling behind the shelter of a counter.

Only the waitresses and salesgirls—and Private Prune—remained above floor level. And even they—particularly Prune—were frozen in shocked horror.

The noise that rattled so terrifyingly from Prune's throat had stopped after its short burst, and now the silence was ringing.

Private Prune gulped miserably. In all his life he had never heard the din of a caliber .50 machine gun, save in the movies. And though this had been much louder and considerably more frightening, he had realized instinctively what the sound had been.

By now the sergeant across the counter had climbed cautiously to one knee, and was peeking over the spilled remains of his coffee. His eyes were wide with fear, amazement, and a bewildered suspicion.

It was the waitress who spoke first.

"What was the idea of that?"

Private Prune met her hostile, accusing stare for only an instant, then he turned his head away, crimsoning.

"I—I was just clearing my throat," Prune mumbled.

The sergeant, braced by the waitress' calm, had climbed to his feet. He leaned over the counter, glaring redly at Prune, and pointed a trembling finger.

"Y-you done that?" he demanded irately. "You made them machine gun sounds? It sure sounded that way."

Percival Prune slipped sideways on his stool, his eyes searching frantically for the nearest exit. He could see the others of his comrades-in-arms, who had dropped to the floor at the gunfire sounds, rising to their feet, coming out from behind the shelter of counters, brushing themselves off, and looking unanimously displeased about it all.

Prune shook his head in a jerky negative, got to his feet, and started for the nearest door.

"Hey there, you!" someone shouted. "Just a minute, soldier," another voice cried.

BUT Private Prune didn't tarry. He broke into a scrambling

run, made the doorway, and leaped down the steps two at a time.

He ran until his lungs were bursting, two blocks, three, four.

Exhaustion finally forced him to stop, and he found himself

staggering gaspingly along a deserted squadron street which he

recognized as being in the vicinity of his own barracks.

As far as Prune could ascertain from harried glances over his shoulder, no one had pursued him from the Post Exchange. He relaxed somewhat.

Prune paused and put his head in his hands. His body was seized by a sudden trembling which, with his prolonged and arduous gasping, shook him from head to foot.

Private Prune felt ill, and utterly frightened.

Something—to quote an advertising slogan—new had been added. To his hideous repertoire of unwilling voice broadcasts was now added sounds. Any kind of sounds, apparently; for machine-gun sounds were certainly an indication of the versatility his curse was taking on.

Private Prune felt reasonably certain that his unwitting machine-gun sound reproduction was caused by no other fact than that machine guns, somewhere out on the planes on the flight line, were probably going to be tested a few minutes after Prune forecast their racket. The fact that he hadn't seen the guns, and that the distance from the PX to the flight line was greater than any previous distances over which he had picked up sounds-to-be-heard, indicated—if anything—that his dread plague was growing stronger.

Private Prune, suddenly conscious of the fact that the position he had assumed in the squadron street was one to attract attention, took his head from his hands and tried, earnestly, to stop trembling.

This effort produce little in the way of results. He was able to control the tremors in his quaking knees well enough to walk, but that was about all. He still trembled violently, and his teeth chattered like castanets in a high wind.

It was the chattering of his teeth that Prune minded most. For while they chattered he was unable to keep his mouth shut—naturally enough. And the constant fear that his open mouth would produce further pre-broadcasts of voices and sounds was acute.

Prune had gone half a block when his fear of further demonstration of the plague was realized. All, of course, because of his chattering teeth and open mouth.

It was music that came from his voice box this time—band music!

It was highly audible, very vigorous, and quite stirring martial music. But it didn't, of course, please poor Percival Prune.

Miserably, he halted, frozen where he stood. The martial air came from his chattering jaw majestically and with awful loudness.

Someone in a barracks just across the street from where Prune stood rooted in terror, opened a window and thrust forth his head. No doubt a curious G.I. who wanted to see the military band he thought was passing by in the squadron street.

Prune was jolted into motion by the sound of the opening window and the appearance of the head.

Over the din his larynx was making, Prune heard the soldier shout:

"Hey, fella, where in the hell's that music coming from?"

Prune gave the questioner a glassy stare and started to run. Then he changed his mind, slowed his abrupt flight, and started to march off in the other direction—in perfect step to the martial air that was blaring from his mouth.

AT the corner, Prune could hold his masquerade no longer. He

turned down it and started a mad sprint. In less than three

frantic strides, the music within him ceased as abruptly as it

had started. In something like two dozen strides more, Private

Prune realized that he was no longer giving out with "The Stars

and Stripes Forever," and he came to an abrupt and sickly

relieved halt.

Private Prune felt cold and sick and limp. But the trembling, like the music, had also ceased. He was able to clamp his jaws firmly together and hold them that way—much to his tearful joy.

He looked around, trying to find the direction to his barracks. The barracks just across the street from him had a sign below its number. The sign read "Air Base Band H.Q."

Prune was staring at it when "The Stars and Stripes Forever" roared forth once more.

For a moment Prune almost collapsed. He'd been certain that the music was again coming from his mouth—even though his jaws were clamped to prevent such a recurrence. But to his vast relief, such was not the case.

The tune was coming from Band Headquarters just across from him. Obviously the members of the band were there rehearsing, a fact that suddenly made it clear to Prune how he had picked up the pre-broadcast of the same number they were now playing. The waves, or whatever it was that caused his awful plight, had been close and strong. They had blared out in broadcast from his mouth because they had been due to blare forth in a few moments, and Prune had been nearby to send them forth in advance.

Prune shut his eyes against the horror of his deductions. Now he could add music to his terrible repertoire. Voices, noises, music. Anything and everything could—and did—emerge from his helpless larynx.

Unconsciously, Prune fell in step with the marching rhythm of the tune the band across the street was playing. He moved along almost robot-like in this manner for half a block, trying to shut off the spigot of his terror by stopping his mind against it.

But it wasn't much use. At the corner, Prune came into view of his own barracks, and he regained his bearings for the first time. He sighed, then remembered that such luxuries as sighs might result in further pre-broadcasting. He clamped his jaws tight once more, and set out across the street toward his barracks.

Desperately Prune was hoping that, in the seclusion of his quarters, he might find sleep and some respite from his plague. Sleep, too, he reasoned not too convincingly, might provide a miraculous cure for his mysterious malady. He might wake up to find himself normal once again.

But in spite of his wistful wishful thinking, Percival Prune could feel the symptoms of his strange sickness returning. The chills were coming back, and the uncontrollable shivering that was a part of them.

WHEN Percival Prune returned to his barracks, he crawled

immediately into bed, drew his blankets over his head, and lay

there shivering. He closed his eyes trying to blot out the horror

that seemed to engulf him, but it helped little. Nothing helped.

He could only lie there trembling, biting his lip, and wondering

what had come over him.

The trembling that had been fear, was now something more than that, something apparently prompted by an actual physical chill. It seemed to Prune that he was being seized by waves of electrical impulses which lifted him dizzyingly into crest upon crest of current shocks. His lips were dry, and his tongue seemed caked. And when he timidly touched his forehead, he found it hot, dry, almost feverishly burning.

He tried to tell himself that he was all right, but made the mistake of trying to do so vocally. The result was terrifying, for when Prune tried to form the words his vocal cords were again seized by a power greater than his will, and an utterly alien voice came forth instead of his own. It was a voice he had never heard before, saying words over which he had no control.

"Good. There is nobody here. We can talk in safety. Let's get to the point. There is no time to waste."

The voice was low, urgent. It's enunciation was clear, but with the faintest suggestion of a lisp.

Prune opened his mouth again to groan his dismay, and found himself answering that voice in another voice. Another unfamiliar voice.

"You have it all?" this other voice said, as Prune's lips moved to form the words. "Good. We can proceed."

This second voice was also urgent. But it was low, almost guttural.

Percival Prune clamped his jaws shut tight. He wanted no more evidence of his plight. He buried his head deeper under his blankets. The vast electrical waves began to sweep over him again. His teeth chattered. He felt his tongue moving in his mouth. He couldn't keep his jaws shut.

"Good God, sir," he heard himself saying in Captain Talbot's voice. "If this is true, it will ruin me!"

"And what in hell do you think it will do to me?" an acidly rasping voice, that of Colonel Priddy, answered from Prune's lips.

Private Prune clamped his jaws hard over a section of his blanket which he stuffed into his mouth. His teeth stopped chattering, his tongue, jammed as it was, formed no more words in voices alien to it.

It was then that Prune heard the steps coming up the barracks stairs to the upper bay where he lay shivering beneath his blankets.

Prune tried, through sheer physical resistance, to control his trembling, to lie quietly. He succeeded to some extent.

The footsteps paused at the top of the stairs. There had been two pairs of them. Now there was a moment of silence, while the owners of those footsteps looked around the upper bay.

Then one of them spoke.

"Good. There is nobody here. We can talk in safety. Let's get to the point. There is no time to waste."

It was all Percival Prune could do to keep from screaming, as that voice came to his ears. The same voice which he had heard issuing from his own lips just a few minutes before—saying words phrased exactly as they had been when they came from Prune's uncontrollable larynx.

Private Prune's fingers bit deep into his mattress cover as he tried to control himself.

WHEN the second voice spoke. And it was the voice in which

Prune had answered the first, scant minutes ago. Low, urgent,

almost guttural, saying familiar words. Words that it had used on

Prune's own tongue.

"You have it all?"

"Of course," said the first voice.

"Good, we can proceed," said the guttural voice.

"It's up here," said the first voice, "carelessly tucked away in my stationery box on the shelf. I knew they'd never look in the obvious place."

There was a moment's silence, a grunt of satisfaction, then the second voice said:

"Ahhhh, fine. Very excellent work. With these papers our Fatherland will be saved much time and research. Let Yankee brains work it out. We perfect it!"

"We'd better hurry," the first voice said. "Fritz and the others will be waiting by the road just off the south runway fence. It is important to lose no time. They don't want to spread an alarm until they are positive the papers are missing. We've only that long. They are almost sure now."

"Let's get going!"

It was then that the tidal waves tossed Private Prune sky-high on their electrical crests. His jaws came unclamped from the blanket as the spasms shook him.

And it was then that he heard himself say, in the guttural accent of the second speaker:

"Ach, Schweinehund! There is someone here!"

There was a sharp intake of breath from the corner of the bay where the two men had been talking. Then an instant of ominous silence. Private Prune had betrayed his presence.

Then the guttural voice exclaimed:

"Ach, Schweinehund! There is someone here!"

Private Prune groaned dismally, threw his blankets back, and swayed to a sitting position on the bunk. He blinked in the semi-darkness of the bay, his body going through convolutions of trembling.

Two men were coming swiftly toward his bunk. They both wore the uniforms of U.S. soldiers. They looked extremely irate at having had an audience to their conversation.

One was tall, lean, blondly handsome. The other was short, barrel-chested, swarthy, with a scared face. The second had a .45 caliber automatic, Army make, in his hand. He had just taken it from the pocket of his G.I. overcoat. Now he was pointing it at Private Prune.

Percival Prune rose to his feet, staring pop-eyed at the obviously hostile approach. He was so frightened that his trembling had ceased.

"It is too bad that you happened to be around," said the short, swarthy, guttural-voiced man.

"There is no time for speech-making, Ernst," said the tall, blond chap, "Put him out of the way and let us get going."

"A little closer, Paul," said Ernst. "One shot makes noise enough. Two would be too many. Close and careful aim, one shot."

It was suddenly crystal clear to Private Percival Prune that these two soldiers intended to shoot him. It had taken a surprising number of seconds for this fact to register, but then Private Prune was not in a normal state of mind or body.

The two were less than five feet away, and the swarthy one, called Ernst, was smiling unpleasantly in anticipation of the task at hand.

IT was then that Percival Prune opened his mouth in a frantic

attempt to plead for mercy.

And it was then that Prune once more heard a voice other than his own issuing from his lips. This time it was the voice of First Sergeant Rice, and it came forth in a husky, startled bellow.

"Well, I'll be damned! What in the hell is going on around here?"

The effect was instantaneous.

"It's Rice!" snarled the blond man.

Both Paul and Ernst wheeled away from Prune, staring wide-eyed at the entrance to the bay just off the staircase, their eyes searching for the presence of First Sergeant Rice, whose voice they were certain they'd heard.

At that opportune moment, when both had their backs turned to him, Private Percival Prune made a frantic dash for safety.

It was unfortunate that the aisle between the beds in the bay was narrow, and it was also unfortunate that Prune was still clutching a blanket in his hands when the two had started for him. For now Prune bolted down the narrow middle aisle, prompted by sheer panic, blanket still in his hands, and ran headlong into the backs of his two antagonists.

It was the frantic strength of his effort, rather than his negligible weight, which resulted in Prune's knocking Paul and Ernst off their feet. It was sheer gravity that carried Private Prune and the G.I. blanket down atop the two in a tangle of arms and legs.

The blanket had somehow gotten wrapped around Paul and Ernst, and Percival Prune had somehow kept his frantic clutch on the blanket. The result was simple. Ernst and Paul, wound up in the blanket and flat on their backs, threshed madly at each other, each thinking the other to be Prune, and inflicting a sizeable amount of damage through this misapprehension. Prune, tangled in the mess to the point where he seemed likely at any instant to be thrown to the ceiling like a rider from a bucking horse, clung frantically to the edges of his blanket to preserve his skull.

The accompanying din was incredible.

So incredible that it drowned out the clatter of feet coming up the staircase.

The threshing party heaved and tossed and cursed and banged back and forth in the narrow aisle until, inevitably, Prune and the pair beneath the blanket, came in contact with a two-story bed, tipping it down on them with a resounding crash.

It was at this point that Ernst's pistol went off and here that the iron double-high bedstead knocked Prune cold in its descent.

And it was but a split second later when Sergeant Rice burst into the upper bay of the barracks, with a panting colonel and a winded captain hard on his heels.

First Sergeant Rice roared thunderously:

"Well, I'll be damned! What in the hell is going on around here?"

But he wasn't damned for long. Colonel Priddy spied the official manila envelope, bulging with the papers on the super-radar experimental data, lying on the floor where Ernst had dropped it in the melee.

Captain Talbot saw the army automatic that had skittered from under the blanket when Ernst had accidentally discharged it. First Sergeant Rice saw only a fight, which was contrary to discipline, and which he could legally enjoy in the process of quelling.

All three men hurled themselves on the groggy Ernst and Paul as one, tearing the beaten, punch-drunk pair of conspirators out from under Prune, the bedstead, and the blanket.

Colonel Priddy grabbed the envelope with the precious secret data. Captain Talbot thoughtfully secured the .45. First Sergeant Rice grabbed the two culprits, knocking their heads together in his enthusiasm.

"They was fighting, against regulations," joyfully boomed Rice, smashing their heads together again, just to keep in practice.

"Considerably more than that. They were armed," said Captain Talbot, displaying the weapon.

"All that is posh," elaborated Colonel Priddy. "They were the blank-blank-sons-of-blank spies who stole the super-radar data. Look. Here it is."

It was a moment later when they noticed Private Percival Prune, lying quite unconscious under the overturned double-deck bed.

First Sergeant Rice whistled audibly, his eyes mirroring the stark admiration and envy he felt.

"And look at who it was that discovered 'em, and stopped 'em," he said almost reverently....

WHEN they came to Private Percival Prune with the decoration,

two days later, he was still in bed in the Station Hospital. The

gash on his head had almost healed, but his temperature

had—for a full thirty hours—been high enough to

warrant their holding him for observation.

But Private Prune hadn't minded being held. They had assured him that he wouldn't be dismissed from the service because of a high temperature. And—what was vastly more important—his malady had completely disappeared. Prune, too excitedly delighted about this to dare hope that it was true, attributed it vaguely to his having been cracked on the head by the bed. That was the only reasonable explanation he could think of.

The nurses had been kind and most attentive. They had called him a hero on several occasions, but Prune had been too embarrassed to ask them what they were talking about. Colonel Priddy's visit, therefore, came as an overwhelming surprise to Prune.

The colonel stamped into Prune's ward late on the afternoon of that second day in the hospital. He came directly over to Prune's bed. Prune was far too shocked to perceive that Colonel Priddy was accompanied by Captain Talbot.

To the colonel, sentimental posh was obviously embarrassing. In his acidulous voice he inquired of Prune's health, gave him no time for a reply, and went into an obviously rehearsed speech.

The substance of it was that Penning Field was proud of Prune, that the colonel would find some kind of a place—on the ground—for Prune in his Bombardment Group, and that everyone was very, very grateful that Prune had been a hero. Paul and Ernst had been dangerous spies, the colonel declared—all the more dangerous because they had been working from within the ranks of the Army itself for over a year. Prune's utter disregard of personal safety in bringing these spies to capture had been an inspiration to all. Because of this, the colonel concluded somewhat briefly—eager to be done with this posh—he was pleased to award Private Prune with this medal.

As the colonel extended the medal, leaning forward to pin it upon Prune's pajamas, Percival Prune—utterly overwhelmed and with tears in his eyes—tried to find words to express his thanks.

His throat was a lump of emotion as he opened his mouth.

His eyes were wide with horror at the strange words that tumbled from his lips. Words spoken in a voice other than his own!

"Take that damned thing away! I don't want it! I won't have it! Clear out of here!"

WHAT followed was a scene that was mercifully blurred to

Prune through his own distressed confusion. It was a brief,

violent scene, in which Colonel Priddy, followed by Captain

Talbot, made a highly indignant exit. It was a scene in which

Prune's nurse burst into tears.

But when Prune took his head out from beneath the covers of his bed, he found himself alone with the terrible, thoroughly frightening realization that his malady had not been cured. Not completely, at least.

Tears welled into his sad gray eyes, and he wondered, hopelessly, whose voice he had pre-broadcast this time.

He couldn't, of course, see or hear the scene that was taking place at that moment in a ward some fifteen doors down the corridor from his own. There a gentleman, whose voice and words Prune had fore-spoken—an irate G.I. patient—was using just those words to tell his nurse what to do with the glass of castor oil she wanted him to drink.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.