RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Amazing Stories, September 1941, with

"Ferdinand Finknodle's Perfect Day"

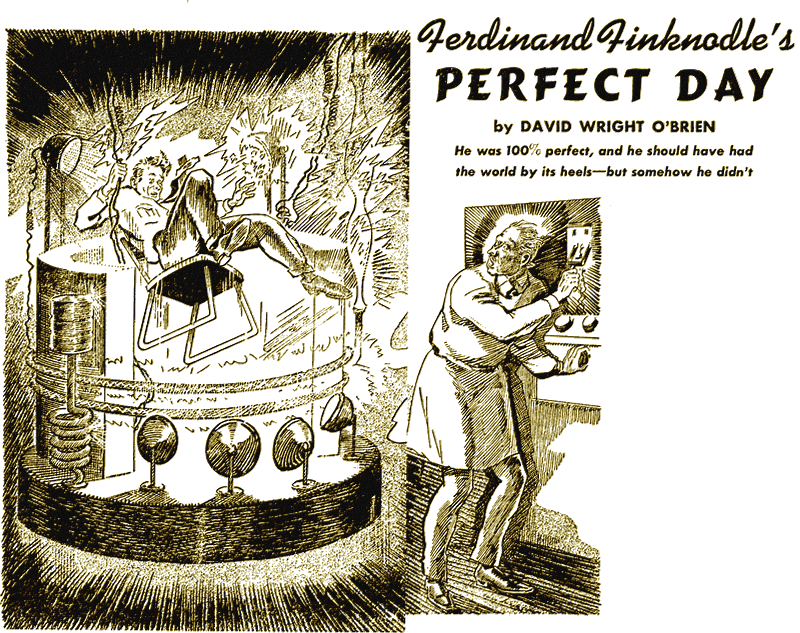

Finknodle touched the wire—and hell broke loose in Gottschalk's basement.

"HAAAAAA!" the exclamation came explosively from old Doctor Gottschalk. "I think it is ready, my machine!"

Ferdinand Finknodle nodded vaguely in reply, his soul jarred from its ramblings in a private Paradise he had invented—a sort of Never-Never-Land, in which there was no Mrs. Finknodle to make his life Hell. He stared around the basement, at the bewildering machine with all its doodads.

"Good," he murmured, "that's fine, Doctor Gottschalk." He was wishing that the hour would pass, so that he could go home. But he knew Mrs. Finknodle's wrath would be terrible if he were to spend anything less than an hour with Doctor Gottschalk, their scientific neighbor.

"It's an opportunity to broaden yourself, having Doctor Gottschalk as a neighbor," Mrs. Finknodle was fond of saying. "So I want you to spend a little time with him at least three nights a week."

Doctor Gottschalk was babbling again, jerking Finknodle back to the bare reality of the basement. The basement with the crackpot machine and its screwloose inventor.

"My Perfection Machine will revolutionize science!" the white haired old man declared. "It will eliminate static charges around an individual, keeping that individual from veering from his proper groove."

Finknodle stopped gnawing his moustache long enough to remark,

"How nice."

"If you will recall, Finknodle," the old scientist went on, "I have compared perfection, absolute perfection, to a groove. A groove running in a straight line."

"Well," Finknodle ejaculated. "Well."

"The only trouble with the groove of perfection," Doctor Gottschalk burst forth again, "is the fact that there are so many static charges in the atmosphere. Static charges which make people veer from their groove. That is why no one, nothing, is perfect," the old man concluded.

"Is that a fact?" Finknodle ventured, wondering what the old man was talking about.

"Yes," Gottschalk nodded, "but my machine will eliminate such static, will make perfection!"

Finknodle wondered if he was expected to applaud.

"Tomorrow," said the old doctor, a wild gleam coming into his eye, "I will start my experiments with guinea-pigs!"

Finknodle glanced hastily at his watch. Glanced hastily and breathed a sigh of relief. His hour was up. He could go home now, and Mrs. Finknodle wouldn't be displeased. He rose swiftly.

"Sure thing, old man. Great things, guinea-pigs. Cute and all that. Well," he had edged to the basement door, had his hand on the knob, ready for flight.

The old scientist wiped his hands on his greasy smock.

"You must leave?" he asked.

"Sorry," said Finknodle, who was not in the least. "Sorry, old boy, but my wife will be expecting me."

"If you would do me a favor before you leave ..." began the old man.

Finknodle looked at him suspiciously.

"What is it?"

"If you would stay just five minutes, I would like to line my machine up."

Finknodle hesitated. He suspected that if he didn't wait five minutes to help, the old blighter would tell Mrs. Finknodle on him, and he would be in for more hell. He shrugged.

"Very well."

THE old doctor beamed, grabbing him by the arm and leading him over to the front of the strange machine. He had grabbed the chair, also, and forced Finknodle down on it.

"It is like a camera," the old man explained, "and I just have to focus it for my guinea-pigs tomorrow. Sit where you are!"

Finknodle sat, obediently, patiently, while the old man did this-and-that to the gadgets on his machine. A bright light broke out from a bulb above him, bathing Finknodle in its white glare. Then another light flashed forth, its beam also centering on Finknodle.

"Right in line," murmured Doctor Gottschalk happily, still fluttering around the apparatus.

Minutes passed, while the old man tinkered and breathed heavily through his thin nose. Finknodle was rapidly becoming bored with the proceedings. It was taking longer than the five minutes agreed upon. Restlessly, he reached forth his hand, running his fingers idly along a set of red buttons on a projection of the machine beside him.

"Don't do that!"

Gottschalk's scream was too late.

There was a deafening explosion, splashing white flashes of light, and a shattering concussion knocked Finknodle off his chair. While the machine hissed and spluttered like a maddened thing, he lay stunned on the cold cement of the basement floor, Gottschalk's weird cries of horror coming faintly to his ears.

Then the machine stopped spluttering, the lights stopped flashing, and all was silent, save for the moans of the anguished old man.

"You have ruined my machine!" the old man screamed. "You have ruined my Perfection Machine! you fool!"

Dazedly, Finknodle managed to climb to his feet, and he stood there, pale and shaking, looking at the old scientist. Purple with rage, Doctor Gottschalk was dancing first on one foot then the other.

Finknodle found his head was clearing, that his vocal cords were regaining force.

"A fine thing," he managed to splutter. "A fine thing. You... you tried to kill me!"

Thoroughly disgusted, still slightly dazed, and with the old man's cries of damage suits ringing in his ears, Ferdinand Finknodle marched out of the basement.

THREE minutes later, Finknodle marched into his own house, and found Mrs. Finknodle waiting for him in the kitchen.

Mrs. Finknodle was small and thin, with a waspish face, a sharp red nose, and eyes that were perpetually fixed in a commanding glare. Finknodle looked at her, standing there angrily with her hands on her flat hips, and wondered what in perdition he had ever seen in her.

"I have been keeping your supper warm," she began menacingly.

Finknodle's hand shot to the frayed fringes of his moustache, and his sly shoulders seemed to sag even further.

"Yes, Dear," he muttered dutifully, walking to the sink to wash his hands.

Splashing water vigorously along his wrists, Finknodle debated over telling his wife what he had done to Gottschalk's machine. By the time he was drying his hands, he had decided not to tell her right away. He'd put it off until tomorrow. Lord knows there'd been enough trouble for one day, without inviting more of it from her.

"You will be late for your bowling," Mrs. Finknodle said, as Ferdinand sat down at the table. Her voice was harsh, accusing, for bowling every Friday night during the bowling season with the Bloatarians was not Ferdinand's idea. Finknodle himself loathed bowling. Loathed it utterly. He also loathed the big, beefy, back-slapping Bloatarians.

But Mrs. Finknodle had decided, some six years ago, that it would be a good thing for her husband to take up bowling and join the Bloatarians. So Finknodle, without further argument, had become a bowling Bloatarian. And for six years, rain or shine, Mrs. Finknodle saw to it that he bowled.

"You'll be late," Mrs. Finknodle snapped, snatching his plate out from under his nose. "You can eat when you come home."

Finknodle opened his mouth to protest, then closed it. He hadn't been born a mouse. He'd just sort of been forced into the role as his years married to Mrs. Finknodle had piled one on the other, gradually breaking his spirit until it ceased to exist.

Finknodle sighed, a deep, long, lingering sigh, and rose from the table. He wasn't overly fond of his wife's cooking anyway. It was getting so that nothing really mattered much anymore, just so long as he was able to keep Mrs. Finknodle's shrill voice to a well-modulated imitation of a fire siren.

In the hall to the Finknodle living room, Ferdinand found his hat. His wife hadn't followed him to the door, a fact for which he was mildly grateful. His eye caught a peg on the wall, and from sheer force of habit, Finknodle sent his hat sailing at it. He never hit the thing. It seemed symbolic of the futility of his existence.

Methodically, Finknodle stepped forward to pick his hat up from the place where it usually fell. But it wasn't on the floor.

Puzzled, he looked up to the wall peg. The hat was resting there, just as if it had been carefully placed. He'd made it!

Finknodle frowned, shook his head bewilderedly, and took the hat off the hook. Then, still shaking his head doubtfully, he put the hat on and stepped out the door.

ARRIVING at the bowling alleys, Finknodle viewed the scene that spread before him with a vague distaste. There was the usual sound of smashing pins and hearty laughter; the usual cards hanging above the alleys, designating the names of the bowling teams; and the usual array of tall, short, fat, and lean Bloatarians standing about.

He hung up his coat, feeling his usual sense of embarrassment at the red garters which Mrs. Finknodle insisted he wear around his shirt sleeves, and moved over to a table where the Bloatarians were being assigned to their alleys for the evening.

A huge, beefy Bloatarian sat at the table picking the teams and announcing the handicaps for the bowlers. Others stood around, seeing who was to bowl with whom.

Finknodle made his way through the loiterers and faced the beefy Bloatarian at the table. He held out his hand in the lodge grip, feeling like several sorts of fool, and forcing himself to say,

"Hello, Brother."

The "Brother" seized his hand in a crushing grip.

"Brother Finknodle," he beamed, "glad to see you!" The fact that this scene had occurred, without the slightest variance, for the past six years, once a week during bowling season, didn't seem to alter the red-faced man's enthusiasm.

"Let's see," said the beefy Bloatarian, "you want to know what alley your team bowls on, don't you?" He studied the chart in front of him.

Finknodle wanted to scream,

"No, you beefy baboon, I want to buy six tickets to Timbucktoo. I've mistaken these alleys for a steamship company!" But instead, he replied, "Yes, Brother."

There was murmuring from those around the table, and as Finknodle stood there nervously twitching his moustache, he realized that the usual weekly problem of why-did-we-take-Finknodle was under consideration. No one wanted him, inasmuch as he was as accurate on the alleys as a blind man trying to hit a fly-on-a-wall with a peashooter.

After what seemed an eternity, the beefy Bloatarian looked up. "The Hepcats are on alley ten tonight," he said.

Ten minutes later, Ferdinand Finknodle was resignedly waiting his turn to bowl. The other members of his team had rolled their first frames, and as the pinboy set them up again, Finknodle, holding his bowling ball like a red hot pumpkin, prepared to send one down the alley.

Awkwardly, scarcely able to bear up under the weight of the ball, Finknodle lurched forward, his thin arm swinging the bowling ball in a crazy half-arc behind him. Closing his eyes, he let it fly, expecting to hear the familiar clatter as it bounced uselessly down the gutter.

He fell flat on his face two inches from the foul line. Fell flat on his face, as an amazing sound reached his ears. He'd hit the pins!

And as he picked himself up, scarcely hearing the wild cries of surprise from his teammates, his jaw dropped open in astonishment. Somehow, in some fashion, Ferdinand Finknodle had knocked down every last pin. He'd made a strike!

Which was the start of a wild, impossible, incredible evening. For, while the confusion mounted higher and higher, and the other teams stopped bowling to stand gawking foolishly around the Hepcats' alley—Ferdinand Finknodle rolled three perfect games!

PEOPLE were pounding Finknodle on the back. Screaming, shouting congratulations, and slapping him until he thought he'd collapse. Bewilderedly, grinning foolishly, he was almost able to feel a comradely warmth for his fellow Bloatarians.

Somehow, against their protests, he was able to force his way out of the smoky torpid atmosphere of the bowling alleys, able to emerge after twenty minutes of wild festivities into the cool night air.

Finknodle wanted to walk, wanted to cool off, wanted to think this thing out. He had skillfully evaded offers of fellow lodge members to see him home, and was now walking slowly along the boulevards alone, oblivious to the sounds of traffic, to the streams of people who passed him.

Finknodle was nobody's fool. He was quite aware that something terribly odd, wonderfully strange, had happened to him. Just what it was, he wasn't certain. But such a staggering reversal of fortune in his drab, uncomfortable existence was indication enough that he was emerging into a new Era. Why, he could even feel it: in the air he breathed; in the new, strangely confident spring to his step.

For the better part of his life, he had been living in the drab gray surroundings that one sees in newsreels in a movie house. And now it was just as if the newsreels had ceased, and he lived in a world of glorious technicolor.

Finknodle knew that a perfect game on a bowling alley had been achieved before. Numerous bowlers had done so, and any fairly good bowler had a slight chance of doing so. But Finknodle had not been a good bowler. He hadn't even been average. Lousy would have been a flattering word to describe his game.

So Finknodle, not being an utter fool, realized that something other than mere chance was responsible for this drastic reversal.

"But what?" Finknodle asked himself, halting there on the boulevard. "What?"

He could find no answer, so bewilderedly, he turned his steps in the direction of his house. After all, he reflected, perhaps he had reached a sudden zenith in existence, had the one peak moment of glory which philosophers declare comes to every person sometime during the span of life.

The thought made Finknodle rather sick. If he had had his Moment Supreme, it would mean that, from now on, his life would be on the downgrade. Finknodle shuddered to think that there could be such a thing as a downgrade to the life he'd been living.

Besides, if there were such a thing as a Supreme Moment, he hated to think that he had wasted it, drained it, on the Bloatarian's bowling alleys. There were many other things he would rather have done with his Supreme Moment.

Things involving Mrs. Finknodle.

For, although Finknodle's life had been an utterly futile thing, he had cherished, like every other mortal, certain wonderful dreams. It was with such thoughts that he at last turned up the walk to his house.

FINKNODLE entered his house, noticing subconsciously that the lights were off, which meant that Mrs. Finknodle was already upstairs and asleep.

He noted, subconsciously too, that his hat once again landed neatly on the hall peg when he sailed it toward the hat rack.

But these were matters of small moment, for Finknodle was still engrossed in those perfect games at the bowling alley, in their possible significance. Slowly, he made his way upstairs, a troubled frown on his brow.

It was a matter of small moment, too, for Finknodle to realize that his ten year old serge suit and his eight year old mauve pajamas had become slightly smaller, as he changed from one to the other.

"Probably shrinking," he mused, "from sheer senility."

Then, padding into his own dingy little room, a cloister which Mrs. Finknodle liked to refer to as his "den," Finknodle stretched out on his hard cot. But his eyes didn't close instantly. As a matter of fact, they remained open for fully three hours. Three hours in which Finknodle grappled furiously and futilely with the strange enigma of the bowling alley and the perfect games.

At last, however, Finknodle slept.

"BRRRRRRRR, brrrrrrrrr, brrrrrrrrr!" Finknodle came out of his slumber with a wild start, his hand darting out to choke off the rattle of his alarm clock. Looking at the clock, he saw that it was morning.

Time to be rising. Time to go to work. Time to—

Finknodle rubbed the sleep from his eyes. Rubbed and stretched. Even as he extended his arms luxuriously, he heard the rending of cheap cotton material, and knew that his mauve pajamas were no longer intact.

"Damn!" he muttered, knowing that here was something else for which Mrs. Finknodle would give him hell. Sleepily, then, he rolled out of bed and shuffled morosely to the bathroom. With every step, he could feel the mauve pajamas rending a bit more.

His mind was still foggy from his interrupted slumber, but he sensed that there was something important on which he had been musing before shaking hands with the sandman. For the life of him, he couldn't recall what it was.

Finknodle was in the bathroom now, and his hand had turned the washbowl faucet. Washbowl—wash, bowl—that was it, Bowl! Excitedly, Finknodle recalled his perfect games of the night before.

The old excitement returned to him. He, Ferdinand Finknodle had rolled three perfect games! He, Finknodle, a mousey little guy with pale eyes, thin shoulders, and a scraggly moustache.

"But I did," Finknodle told himself, "I really did!"

And he switched on the bathroom light for better vision, bending over the washbowl to peer into the mirror.

"Let's have a look at the man who rolled three perfect games," he muttered.

Finknodle blinked into the mirror.

Blinked, from long habit, rather sheepishly. Finknodle blinked and then gurgled. Gurgled in a horribly strangled fashion, while his jaw fell open aghast.

Staring out at Finknodle from the mirror was a stranger!

Wildly, F. Finknodle grabbed the sides of the washbowl for support, closing his eyes in sharp horror. Then he opened them swiftly again for another peek. The stranger was still there!

"Who are you?" he rasped hoarsely, and the figure in the mirror moved its lips in the same words.

Frantically, Finknodle shot one hand to his face. The stranger in the mirror did likewise. Finknodle opened his mouth. The stranger did the same.

"Who are you?" Finknodle whispered hoarsely again. And again the stranger's lips moved in the same words.

It was then, as the incredible Truth began to dawn on him, that Ferdy Finknodle had the courage to look down at his own body. A strong, clean-limbed, muscular, powerful body!

"No!" Finknodle gasped, face gone ashen. "No!"

He glanced again into the mirror. Glanced at the face of the stranger. A face gone ashen.

Finknodle could evade the truth no longer.

"Something has happened," he muttered huskily. "Something impossible, incredible, utterly preposterous. I have changed completely!"

For the skimpy Finknodle chassis existed no longer. The pale, tired, Finknodle features were no more. Instead, Ferdinand Finknodle was now in possession of a physically perfect body, a lithe, powerful physique.

Another glance into the mirror told him that the transition hadn't stopped with his physique. His features, too, were utterly changed. The moustache was still there, true enough, but it was no longer a moth-eaten apologetic thing. It was straight, crisp, and debonair—as any good moustache should be. The rest of his features, from his straight, perfectly moulded nose to his strong, clean jawline—were magnificently handsome!

Finknodle reeled.

THIS was impossible. Overnight, in the space of a few hours, this incredible transition had occurred. He realized now why his clothes had seemed smaller as he was changing for bed, why his pajamas had ripped asunder as he tried to stretch on rising. The transition had been going on even as he went to sleep.

It was not every day in the week that Ferdinand Finknodle whipped about exchanging old bodies for new. Consequently it was a matter of many minutes before he could adjust himself sufficiently to the change to enable himself to move.

Finknodle stepped back from the mirror, surveying himself in growing fascination. The horror of the thing, the shock of the change, was rapidly dissipating before a new sensation, a feeling of joyous, wild, wonderful elation.

"I am physically perfect," he muttered again and again. Never, even in the advertisements for gentlemen's underwear, had Finknodle seen such a magnificent body, such a handsome mug, as the body and mug he now possessed.

He plucked off the remnants of the tattered mauve pajamas. Pajamas which had been good enough to conceal the old Finknodle, but were now utterly insufficient for the new.

His trousers were hanging on a hook over the bathroom door, and he knew, as he looked at them, that they'd never fit. Neither would any other of his clothes. Of necessity, therefore, he grabbed a turkish towel and draped it sarong-like around his body.

"Ferdinand Finknodle!" The voice came piercingly to his ears, and he realized that Mrs. Finknodle had risen, was descending on him.

"What do you mean by letting your alarm clock ring until it woke me up, you whelp?" Mrs. Finknodle's voice demanded, drawing nearer.

"I'm sorry, dear," Finknodle began instinctively. Then he suddenly smiled, remembering his new body. Mrs. Finknodle, he was morally certain, would forget her anger at the sight of the wonderful transition in her mate. He smiled, a shy, proud smile.

"Hurry, Dear," entreated Ferdinand Finknodle. "I can't wait until you see me!"

Finknodle had modesty. Even though clad decently enough in his turkish towel, he didn't believe in dashing out into the hall to meet his wife. So he waited serenely, as Mrs. Finknodle's slippered feet shuffled nearer and nearer.

"What on earth are you talking about? Have you gone stark, rav—" Mrs. Finknodle's head appeared around the edge of the bathroom door, then her slatternly-clad person. She stopped short, her eyes taking in the sight of the superbly handsome masculine figure facing her. A moustached, smiling, splendidly muscled fellow—clad only in a turkish towel.

"Hello, Dear," Ferdinand Finknodle began.

Mrs. Finknodle's scream would have drowned out the blast of the Queen Mary's fog horn. It was a scream that ended in a series of bleating shrieks.

"Ferdinand! Ferdinand! Help! Help! There's a MAAAAAAAN in the bathroom. Ferdinand! Police! Ferdinand! Ferdinaaaaaaaand!" Mrs. Finknodle's feet took her racing away from the vicinity of the bathroom, and Ferdinand Finknodle could hear them pounding helter-skelter down the stairs to the first floor. He heard, too, the sound of the telephone being yanked off the hook, and the sound of his wife's excited voice screeching to the operator on the other end of the wire. Screeching something or other about the police.

"Perhaps," Finknodle mused, "I should have broken it to her a bit more gently." For it came to him that his spouse couldn't have been expected to recognize him, at least without a word or two of quiet explanation.

Finknodle was starting out of the bathroom, with a view to following his wife downstairs, to make the thing clear, when he stopped abruptly, paling. He suddenly realized that it was going to take much more than a mere word or two of explanation.

And Mrs. Finknodle was calling the police!

THE vision of himself in a bath towel, standing in a crowded police court, trying to explain to all and sundry that he had changed bodies, was a dash of cold water in the face of Finknodle's hope.

The thing presented entirely too many complications. And even as he was aware of this, it also dawned on Finknodle that he was going to have a hell of a time trying to get anyone to believe him. He knew that his body had changed, because he was still Ferdinand Finknodle, handsome or scrawny. Nothing could alter that.

But that didn't mean that others would be able to tell.

Momentarily smothered was Finknodle's elation at his new physical perfection. Smothered in the urgency of the dawning realization that flight was definitely necessary.

Finknodle clutched at his pants, still hanging on the hook above the bathroom door, then remembered that they wouldn't begin to fit. None of his other clothes would fit, either. Frantically, Finknodle drew the bath towel closer around his new body.

Flight was one thing. But flight in a bath towel was decidedly another. What to do? Flee pell-mell through the streets in a bath towel, looking like a refugee from a nudists' camp. Or take a chance with the police?

He could hear his wife still screeching hysterically downstairs. And then, in the distance, he heard the sound that ignited the spark of sudden decision. Police sirens. Dozens of them, wailing wildly, and drawing nearer and nearer to the house.

Finknodle acted. He grabbed his wallet from the bathroom shelf and, still hanging frantically on to his towel with the other hand, dashed madly for the rear staircase.

He was down the stairs in an instant; then out into the back yard; out into the murky gray light of early morning. Finknodle dashed through the yard and out of the gate leading into the alley.

Glancing swiftly right and left, he decided to run in the latter direction. Finknodle was in full flight. A hunted thing in a bath towel.

A LESSER mortal than Ferdinand Finknodle would have been somewhat perturbed by the prospect of having to dash willy-nilly along crowded thoroughfares, clad in nothing more than a turkish towel. The Finknodle of twenty-four hours before would definitely have quailed at such a venture. But it was a totally changed Finknodle who raced rabbit-like through the alley in an effort to escape the police summoned by his hysterical spouse. Finknodle was growing aware that he not only had a new body—he was also becoming imbued with a viewpoint totally different from that of the night before, of the years before, too.

To begin with, towel or no towel, Finknodle felt no shame. His flight had been prompted by the necessity of avoiding the police, and now, as he scurried around a turn in a winding alleyway, he realized that the first flush of pride he had felt on the realization that he had a perfect body was becoming an overpowering sense of vast assurance.

Finknodle's fleeing steps slowed to a leisurely walk.

"My," he thought aloud, "this is odd. Quite odd. I feel utterly splendid. I feel perfect." He knew that these sensations shouldn't be so. He was well aware that a sense of vast assurance, utter calm, does not usually assail a man who is sauntering quietly about a city in a bath towel.

Ferdinand's brain told him this much, but his emotions refused to respond to his mind. He still felt calm, assured, perfect. He had a feeling of utter well-being, absolute detachment. Finknodle smiled, a smug, complacent smile.

"Don't know why my mind keeps worrying," he remarked, "everything is dandy. Just dandy.

"I was only trying to show her," he added. "She needn't have been so touchy."

He shook his head sadly.

"After all," he mused, "She should have been pleased with me, inasmuch as I'm perfect." At this reflection, Finknodle stopped abruptly. Perfect? Of course he was perfect! All this time, he had been taking it for granted. This was the first occasion on which he actually gave thought to his state.

Just as it was occurring to Finknodle to wonder about the circumstances and cause of his strange transition, the answer to it all came quite effortlessly to his mind. He knew.

"Gottschalk's machine, of course," he told himself utterly matter-of-factly. "The old goof actually did have a perfection machine in his basement. That accounts for the hat peg incident, the perfect games, my new body," he said aloud.

"I'm quite perfect," he repeated. "I should be surprised about it, greatly concerned. But I guess that, because I am perfect, I can't get very worked up over the oddity of it."

Finknodle sighed.

"It's a bit of a shame. I'm perfect, but because I know I'm perfect, and because I am perfect, I can't get a bang out of it."

Then, again, his sense of hurt at his treatment by Mrs. Finknodle returned to him.

"That was no way for her to act," he brooded aloud. "I was only trying to show her."

Suddenly Finknodle halted. Only trying to please her. Of course he'd only been trying to please her. She was ungrateful. He'd come up on her too suddenly, startled her, hadn't given her time to see that he had been right. But what was one ungrateful wife when there was the entire world waiting to be helped?

"Why, of course," Finknodle gasped. "I have the entire world to help!"

He suddenly felt a vast, all encompassing feeling of pity. Pity that gathered the entire universe, and all its shoddy imperfections, under the kindly wing of Ferdinand Finknodle.

"Poor fools," Finknodle muttered softly. "I must help them. I must see to it that they reap the benefits of my perfection. Why," the idea was instantly thrilling, "I can lead the world to a new era!"

Finknodle looked down at himself.

"But not," he conceded, "in a bath towel. I must go among them as one of them. I must have clothes."

Even as he spoke, he spied a well-muscled fellow in a gray tweed suit closing the doors of his garage, some forty feet down the alley. Finknodle smiled.

"I must have clothes," he repeated, his eyes mentally noticing a decided similarity in size.

FOUR minutes later, rubbing the knuckles of his left hand, Finknodle emerged from the alley onto a boulevard. He was clad in a gray tweed suit, and smiling faintly as he thought of the well-muscled chap lying in the alley, clad in a bath towel.

Tiny thrills of excitement raced up and down Finknodle's spine as he stepped out on the boulevard. Excitement prompted by the thought that he was about to begin the creation of a new order, a vastly different era, an age of perfection. He hadn't any particular plan. As a matter of fact, he wasn't quite certain where he would begin his campaign.

"I'll just start in," he told himself. "I'll just start in, that's all."

He was closer to the business district of the city, now, and the sidewalk on which he found himself was much more crowded than the previous one. The streets, too, were jammed twice as thickly with cars, trucks, and trolleys.

Sensations of acute pity assailed him. Sensations prompted by the incredible army of imperfections which stood out all around him. But an expression of benign tolerance broke out on his face, and he shook his head. Once he got started, once his leadership asserted itself, things would all be different.

"This is going to mean work," he told himself, happily, "but it's certainly going to be worth it."

Finknodle was moving along with the surge of struggling humanity on the sidewalk. Moving along and thinking, looking for some opportunity to get started, some significant keynote on which to start his campaign.

He found an opportunity.

He became aware of it gradually, as the sharp, insistent blasting and tooting of horns—a sound which had been vaguely disturbing to him from the moment he stepped onto the street—became louder and angrier in his ears.

There was the sharp shrill blast of a traffic whistle.

The shrill blast of a traffic whistle, followed by a steadily mounting wave of noise. Noise from trucks, automobiles, and vehicles of every description. The din of tooting horns was mounting to deafening proportions as Finknodle, frowning perplexedly, looked over the heads of the crowded sidewalk.

At an intersection directly in front of him, Finknodle saw the cause for it all. A traffic snarl. A snarl of such proportions that it had the intersection's stream of traffic completely bottled.

Looking swiftly around all corners of the intersection, he saw that cars were jamming along all four streets, in all directions, for as far as he could see. In the center of the intersection, red-faced, angrily bewildered, and freely perspiring, was a beefy traffic cop. He was glaring wildly around between blasts on his whistle, and waving his arms this way and that.

"The futility of them all," Finknodle murmured pityingly. "It's so typical of their entire existence."

He smiled. Here was his chance.

RAPIDLY, Finknodle began to push through the crowds around him, toward the corner. Somehow, he forced his way to the curb. Then he was out into the street, edging around the automobiles stalled uselessly there, heading for the cement safety island in the middle of the intersection. The safety island on which the beefy, red-faced traffic cop was standing.

The blasting of horns was mounting far down all streets leading to the intersections, and Finknodle made his way through all this until at last he reached the safety island.

The traffic cop had seen his approach, was glaring at him as he stepped onto the island. Finknodle smiled at him. Reassuringly.

"It's all right, old chap," Finknodle shouted above the noise and confusion. "I'll untangle this thing for you!"

"Git back where yuh belong!" the traffic cop bellowed at him.

Finknodle was moving over to him, holding up his hand reprovingly.

"Tut, tut," he shouted, "contain yourself, Officer. I've only come to help."

Then, looking swiftly around at the snarl stretching on all four sides of him, Finknodle let the photographic impression of the jam register on his mind for an instant. An instant later, and its solution was crystal clear.

Finknodle turned to the cop, who was descending menacingly down on him.

"Look ..." Ferdinand began.

"Git back where yuh belong, or I'll have yuh in jail!" the representative of law and order shouted hoarsely. His face was streaming sweat, and he waved his arms wildly.

The clamor of horns grew louder.

"Hold on," Finknodle screamed above the noise. "I can help you out of this. If you'll just tell the maroon roadster on the right," he indicated one of the cars in the snarl, "to move forward three feet."

"Sooooo," the cop yelled, "yuh're tryin' to tell me my business are yuh? Up here interfering with law and order and jamming up traffic." Obviously, from the expression that crossed the face of the sweating officer, he had suddenly hit upon the idea of blaming his mess on Finknodle. "I oughta arrest yez," he thundered, grabbing Finknodle by the arm. "Everything was getting along fine until yuh come up here to ball things up!"

The noise from the tooting horns and bellowing motorists grew to bedlam. The grip of the beefy paw on Finknodle's arm tightened.

"I think I will arrest yuh!" screamed the now frantic cop.

Ferdinand tore his arm free from the cop's grasp. Then he waved a hand at the maroon roadster he had indicated before, beckoning it to move toward the island. Motor roaring it started forward.

The cop went berserk, wheeling on his heel frantically, waving his arms in all directions.

"Stop!" he screamed. Then: "Go!"

Finknodle felt a surge of vast impatience. He saw the button for the red and green traffic light system. He pushed it, knowing that his act would unsnarl the jam.

Motors roared, as the stream to which Finknodle had given the "Go" signal moved forward. Other motors roared, as a second stream, acting on the cop's gesture, moved forward also. There was a crash a split second later, as four cars, meeting next to the island, locked fenders.

FROM that instant on, all previous confusion seemed like placid serenity. Motorists were leaping out of cars, the cop was shrilling his whistle between frantic bellows and efforts to grab Finknodle. The horns of cars further back in the jam took up the incessant blare. Four or five of the motorists were approaching the island. They, too, were waving their arms and storming. The expressions on their faces struck Finknodle as being extremely hostile.

"Get that guy!" shouted one of the motorists, a huge, lumbering truck driver.

"Knock his teeth out!" suggested another, wearing a cab driver's cap.

"Egad, gentlemen," screamed a third, a pompously dressed rotund, little man who looked like a cartoon of a business tycoon. "He's probably one of those blasted reds. I'll swear he's a radical!"

The cop was grabbing at Finknodle's arm again, and the look in his eye was exceedingly unpleasant. Finknodle saw all this in a glance. The panorama of confusion, noise, anger, and a growing menace. He saw all this, and decided then and there that it might be the better part of valor to get out of there.

"Get him!" the truck driver thundered. "Jest hold him fer a second, and I'll teach him to muddle t'ings up!"

"Damned red, rotten radical," shrilled the little business tycoon. "He's probably one of those fifth columnists. No, I'll bet he's even a sixth or seventh columnist!"

Finknodle looked wildly around for an avenue of escape. Bitterness and indignation were replacing the feelings of kindly pity he had had less than ten minutes before. Once again he had tried to help, once again he could easily have helped, and once again he was being driven to flight.

Finknodle leaped from the island.

"Get him!" screamed the cop.

"Rotten radical. Why doesn't he go to Union Square to muddle things up? That's where his ilk belong!" the business tycoon screeched indignantly.

Those were the last words Finknodle heard. Zigzagging through the melee of snarled automobiles, he ran for safety.

BREATHLESS and sick at heart, Ferdinand Finknodle moved sorrowfully along a quiet little side street at the edge of the business district a half hour later. He was only faintly aware that he had again outdistanced his pursuers with no trouble. He was only faintly aware of his clever escape, for he was brooding.

"I tried to help," he muttered. "I could have helped. Oh, those fools, those utter fools. They act like they don't want to be helped!"

He saw his rosy dream of a New Era slipping away from him. He saw the picture of Finknodle, The Deliverer growing fainter and fainter until it was a wan shadow.

He could have stood their stupidity, their utter ignorance, for Finknodle realized that they were all, unlike himself, imperfect creatures. But ingratitude and hate had not been what he'd bargained for.

"Union Square," he muttered. "Telling me to go to Union Square, the hangout of crackpots and radicals and wild-men! The nerve of the stupid little fool!"

Finknodle shook his head sorrowfully. Then, abruptly, he paused. Union Square. The hangout of crackpots, loafers, men with nothing to do but sit about arguing over Utopia. A light broke forth on Finknodle's features.

"Why not?" he asked himself. "Why not?"

It was instantly apparent to him that there was no reason in the world why he shouldn't go there. Any cause needs followers. That was what had been wrong with the Finknodle Cause. He had had no followers. He'd been silly enough to try to push it through alone. The men in Union Square might be bums, some of them, dreamers, others, but they would listen. They would listen, and provide the nucleus of a following.

Finknodle smiled.

"Why," he said, "I should have gone there in the first place!"

UNION Square, when Finknodle arrived there some twenty minutes later, was in full session. Around the bandstand in the circular little park were at least four speeches started.

Soapbox orators were holding forth before groups of idle listeners. Finknodle swept in the scene with a beatific gaze. Here was his Mecca.

Approaching one of the soapbox groups, Finknodle heard the orator, a wild-eyed, wild-haired man, declaim,

"And soooo, my distinguished friends, we find that there is nothing right in the world. Down with Capital, down with Labor, down with Aristocracy, down with the Masses!"

There was a sprinkling of applause, a few murmured comments through the crowd. The orator opened his mouth to continue.

"I agree with you," Finknodle shouted, "about nothing being right in the world. Nothing is right, but you can't down everything. It all needs to be changed, that's all."

The wild-eyed orator glared at Finknodle.

"You're all wet," he snarled. "Whatever you said, you're all wet."

Heads were turning to look at Finknodle, and taking advantage of the attention, he elbowed his way through the crowd to the front of the soapbox.

"I'm right," he declared loudly, looking at the orator with scorn. "I'm right and I can prove it!"

"Let him talk," someone shouted.

"Naw," screamed another, "let the new comrade talk!"

There was an instant babble of voices. Some screaming for the orator, others for Finknodle. It seemed like the start of a riot. Finknodle solved it, gently pushing the orator from his soapbox, and ascending it himself. The orator started to protest, but the babble of voices drowned him out.

"Quiet!" Finknodle shouted from his perch on the box, "Quiet!"

The babble subdued somewhat. Subdued enough to permit Finknodle to begin. And at the conclusion of his first few sentences, the noise stopped completely. Finknodle had the floor. Or to be more correct, the soapbox.

It had been instantly apparent to Ferdinand, from the moment that he stepped onto the soapbox, that this was his golden opportunity, his big chance. Inside his mind there burned a fire, a message. Here on this box, before a motley assembly of crackpots, he would deliver his Keynote to Perfection. As certainly as red was crimson, Finknodle had the perfect solution to the ills of the world.

It was so clear, so utterly simple. And as Finknodle talked on, he wondered why no one had ever thought of it before, why the brains and energy of the world had never hit upon it until now. It was vast, tremendous in its scope, and utterly, beautifully simple.

And as Finknodle talked, the crowd grew hushed. Grew hushed, while the groups around the other three orators in the Square joined the gathering around Finknodle.

FINKNODLE talked on, face shining, eyes glowing. He was expounding the innermost secrets of the Universe. Expounding them in terms as simple as childish nursery rhymes. He was so enthralled with his own words, so wrapped up in the message he delivered, that he forgot the crowd around him, forgot everything except the words that came effortlessly from his lips.

He was so enthralled, in fact, that he didn't notice the start of the murmuring after he'd been talking ten minutes. Didn't notice that the silence of the crowd had been a shocked silence, a stupefied silence. But now the murmuring was growing, was continuing to grow.

"Why," breathed a wild-eyed, longhaired little crackpot in the crowd, "the fellow's a radical. A crackpot. I've never heard such blasphemous anarchy, and I'm an anarchist myself!"

Then someone shouted.

"The guy's a nut!" Instantly there were other voices, shrill, wild, protesting, growing in volume.

"Knock him down!" someone yelled. "Knock him down, he's a radical!"

Ferdinand Finknodle was so engrossed that he didn't hear the voices. He talked on—until a brick caught him in the side of the face!

Ferdinand regained awareness as he tumbled backward off the soapbox. Regained awareness like a man jarred out of a dream by a kick in the stomach. All around him was bedlam. Shouting voices, cursing gasps, fists colliding with faces. A riot was in progress.

Foggily, through the dizziness of the blow by the brick, he realized that he was lying on the lawn. Realized, too, that feet were kicking at him, hands ripping at his clothing, that others in the park were clubbing anyone and everyone.

Dazed, bloody, thoroughly shaken, Finknodle crawled forward on his hands and knees. Subconsciously, over his pain and bewilderment, he realized sickly that he had failed again. The bandstand loomed up before him, and Finknodle crawled underneath its protecting shell. Crawled underneath and lay there dazedly, watching the battle going on in the Square. The cut above his eyes made it difficult to see, so he closed them against the pain and hurt and confusion that streamed everywhere around him.

"I've failed, failed utterly," he told himself again and again. "Fools, all of them fools. They don't want to know. They don't give a damn about knowing!"

The physical pain which Finknodle felt was nothing compared to the burning ache in his chest. He was perfect. He was in possession of the knowledge that would lead them all to utter happiness. But the world, he was now certain, wanted nothing of him. Perfection would be tolerated only by perfection.

A strange expression crept over his face. Finknodle knew what he would have to do. He crawled to the far side of the bandstand, just as he heard the sirens of police riot squads drawing up on the park. He knew what would have to be done. And he was going to do it.

EXACTLY two hours later, Finknodle climbed the steps of his tiny bungalow. He looked at the green shutters and the door with the brass knocker, and sighed, thinking of how much had happened since he'd left the place less than ten hours before. He sighed, then his jaw tightened in determination, and he pushed the bell.

The door opened, and the face of Mrs. Finknodle peeked out. Peeked out, then screamed in horror. But Ferdinand Finknodle had stepped in swiftly. Stepped in swiftly and planted his hand across the mouth of his wife.

"Get as excited as you please," he muttered. "It won't do you any good."

"Umghskey!" gurgled Mrs. Finknodle.

Using his handkerchief as a gag, and his belt as a rope, he had his wife quickly trussed up in the next several moments. Then, carrying her in his arms, Finknodle marched through his house, pausing at the bathroom to get a bottle of pills, then out the back door. In another minute he was at the basement door of Doctor Gottschalk, his scientific neighbor.

There was no answer to his knock on the door, so Finknodle stepped back and kicked it in. Then, still carrying his wife, he entered the laboratory of the man who had made him perfect. There in the corner was Gottschalk's machine. A note on the laboratory table said:

"Herr Gottschalk is not in. Signed: Herr Gottschalk."

Finknodle smiled grimly at this.

Depositing his wife on the floor, Finknodle walked over to the machine. The machinations of the thing were perfectly clear to him now, and in an instant he had repaired the damage he'd done to it just the night before. A moment later, and Finknodle had placed his wife in a chair before the machine. Placed her in exactly the same position as Gottschalk had placed him.

Finknodle smiled as Mrs. Finknodle struggled. Then he turned on the juice.

FINKNODLE was back in his own house ten minutes later. Back in his own house, sitting at the telephone.

Mrs. Finknodle lay sleeping on the couch in the living room. Sleeping from the effects of the insomnia pills which Finknodle had forced down her throat after he'd taken her from Gottschalk's basement. He had remembered that sleep had been necessary before he'd become physically, as well as mentally, perfect. Mrs. Finknodle was getting that sleep.

"Perfection and perfection alone can tolerate perfection," mused Finknodle, dialing a number on the telephone. "In a short while I'll have a perfect mate."

Then, with streamlined efficiency, Finknodle went to work on the telephone. He called his bank. He called several investment houses. He called a taxicab company. He called a firm which sold boats, and after a short argument, purchased a small power boat.

"I'll want the boat in an hour," Finknodle demanded. "In the water. Gassed, ready to go." He paused. "And, of course, with supplies."

Hanging up, Finknodle dialed another number. He hummed softly, waiting while the telephone buzzed at the other end of the wire.

"Hello," he said, as a voice answered. "This is Finknodle. Have the messengers been started?" He paused. "Yes, I'll sign all the close-outs on my bonds and deposits. No. It isn't a question of lack of confidence in your bank. I just need money. All I have. I'm leaving town." He hung up again.

Finknodle walked over to his wife, looking fondly at her slumbering form. She was already changing. He smiled. This was splendid. To the devil with all others. Once he had his perfect mate——

The doorbell rang. It was a cabbie.

"Wait outside," Finknodle instructed him. "I'll want you to take my wife and me to Pier 7 in a half hour or so."

After that, the doorbell rang incessantly. Messengers with securities which Finknodle signed for. The bank cashier, with a sheaf of notes. The man from the boat company, to whom Finknodle gave the cash delivered by the bank. All these and many more came and went while Finknodle smiled and signed things.

HIS plan was simple. All his savings, every rotten penny which Mrs. Finknodle had hoarded for them all these years, even the house they lived in, he was turning into cash. Enough cash to buy the boat. A boat which would take him, and his perfect mate, to a tiny island in the Bahamas. An island where they could live untroubled by the imperfections of the world for the rest of their lives. Money wouldn't be necessary there. For everything would be perfect, just as Nature is perfect.

"We'll get away from it all," Finknodle exulted, "and live perfectly amid the perfection of Nature." He grinned. This burning of all bridges was fun. He'd seen to it that there were only enough supplies and gas in the power launch to take them to the island. After that, they could destroy the boat, and all last traces of imperfect civilization.

In half an hour Finknodle had a small pile of bonds and securities stacked neatly on the floor of the living room. All the leftover cash. He smiled wryly, thinking of what poor, dribbling investments these things had been. If he'd known then—

Finknodle looked at his wife. She was still sleeping. But she was no longer the small, thin, waspish, red-nosed shrew. The new Mrs. Finknodle, he saw, was going to be a creature of sheer delight. Quite perfect. Finknodle grinned again, and struck a match.

The pile of securities and bonds in the middle of the floor went up in a puff of flame, as Finknodle put the match beneath them. To Finknodle, it was beautifully symbolic. He bent over, and lifted his wife gently from the couch. Then, with one last glance at the burning pile of papers on the living room floor, he opened the door and stepped out of the house.

"Buddy," said the cab driver, as Finknodle, carrying his wife in his arms, stepped into the cab. "Buddy," repeated the driver, "I don't want to cause you no alarm, but I think your house is on fire."

Finknodle looked back at his home. Black columns of smoke were pouring from the window. He saw, too, that orange flames licking out from the side of the building would soon spread to Doctor Gottschalk's house. He smiled. It was a good idea to have the machine destroyed also. Besides, the place was over-insured, and the old crackpot would be glad to see it burn.

"Let 'er burn!" Finknodle chortled happily. Then: "On to Pier Seven!"

The driver shrugged and threw the cab into gear.

THE sun was warm on Finknodle's face as he leaned beside the wheel of the little power launch. Warm and pleasant. Especially pleasant, as he contemplated the joys of a perfect spouse. Mrs. Finknodle was still asleep from the pills. But she should be waking any moment. Finknodle had placed her tenderly in a bunk in the cabin below.

Finknodle grinned and stretched. Life was at peak. Behind him were the horrors of his previous existence. Past and gone forever. Never again would he hear the shrill voice of Mrs. Finknodle screaming—

"FErrrrrrrrDINaaaaaaaaND!" The cry came from the companionway leading down to the cabin, the cabin where Mrs. Finknodle had been quietly slumbering. "FERRRRRDINAAAAND!"

Something went cold inside Finknodle's chest. He knew that voice. Only too well did he know it. Footsteps were ascending the cabin companionway, and Finknodle's eyes fixed in horrified presentment on the door. He gulped.

The door opened, and Mrs. Finknodle stepped on deck.

"Ferdinand Finknodle," began his better half, "what's the meaning of this?"

Finknodle fought for words. Fought for words and fought for sanity. Something was definitely out of line. Mrs. Finknodle was just as he had expected her to be. A physically perfect, utterly magnificent specimen of a woman. But the look in her eye. And the tone of her voice—those belonged to the old wife, the old Mrs. Finknodle!

"We're both perfect," Finknodle said in a quavering voice. "We're both perfect, dear. I hope."

Mrs. Finknodle put exquisite hands on her breathlessly beautiful hips, and glared at Ferdinand balefully.

"I'm perfect," she amended. "I'm perfect all right. But look at you!"

Finknodle looked at himself. He was still the same magnificent physical masterpiece. He blinked bewilderedly.

"So ... so ... so am I!" he bleated indignantly.

"That," declared his wife, "is what you think!" She shook her beautiful head. "Boy, what a mess. There's plenty to be done with you!"

And then it dawned on Ferdinand Finknodle. Obviously, there was one part of his spouse which hadn't changed—her disposition. Her perfectly rotten disposition!

He opened his mouth to speak, then snapped it shut again, his eyes traveling over the new Mrs. Finknodle. She might still have the disposition of a persecuted boa constrictor, but, boy, what a chassis. What wonderful compensations she possessed!

Finknodle smiled, a slow, complacent smile. A smile touched with a good deal of speculation, and an infinite amount of satisfaction. Let her go to work on him. He was perfectly content. And it was every woman's right—and delight—perfect or not, to remake her husband.