RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

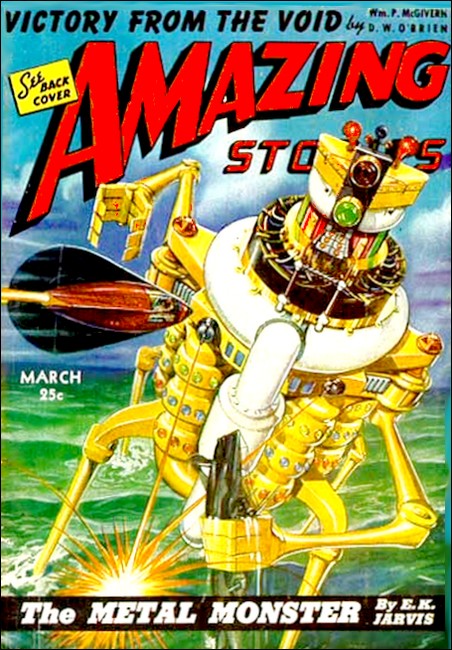

Amazing Stories, March 1943, with "Bring Back My Body"

"And here we have a young man," said the announcer, "who seems anxious to speak."

Young Devlin's body had a mind of its own. One day when his

psyche was absent, it took a run-out powder, went on a spree!

I WAS sitting in my office cleaning my fingernails with a pen-knife, just like private detectives are supposed to do in all the stories written about them. Cleaning my nails with my feet on my desk—also according to the best authorities on what a private gumshoe does between shooting crooks in alleys and getting drunk—and wondering when in the hell I was going to have a case.

It was all just like the opening of a Dashiel Hammett mystery novel, you see, and should have resulted in at least a beautiful blonde staggering through the door with a knife in her lovely breast.

But being a bit of a realist, I wasn't counting my blondes before they were stabbed. Nor was I even expecting a mysterious note telling me to get out of town. Incidentally, I'd have welcomed such a note if it had carfare enclosed with it.

Actually, my razor-keen mind was dreading the entrance of the office building manager to tell me he couldn't let that back rent go any longer. I was dreading that, and wondering if I'd find my hotel room locked by the management when I returned.

Now and then I'd glance at the telephone at my elbow. Somehow I'd been able to keep the bills paid on that, being smart enough to realize that without it I'd be completely sunk—if I wasn't already.

Every time I'd glance at the phone, of course I'd hope that it would ring. Not real hope, you understand. I was beyond that. Just the sort of hope a person has now and then when he wishes an unknown uncle would die and leave him about fifty thousand smackers.

There was damned little chance it would ring. After all, the name "Kendrick Secret Service" in small type in the telephone book was scarcely a tempting bit of commercial copy designed to lure in customers by the dozens. Especially with the full page telephone book ads all the really big gumshoe agencies carried.

Who'd bother with Mike Kendrick and his jerk, one-man agency when he could get Hargrave, or Pinkerton's, or any of the big detective outfits to smooth out his troubles?

So I sat there, paring my nails because I had nothing better to do, occasionally taking a side glance at the phone on the edge of my desk.

And then the damned thing rang!

So help me—brrrrrrring, brrrrrring, just like I'd almost forgotten how they ring!

For a minute I just stared at the thing.

Then my heart was down in my stomach doing flip-flops, and my hands were moist and I felt as if I was losing my voice.

I grabbed for it. No fooling around. No being coy. I grabbed for it, bracing myself for the phrase, "We're just testing your wire, sir."

"Hello," I bleated. "Kendrick's Secret Service. Michael Kendrick speaking." My voice ran up and down the scale with stage fright.

There was an instant of silence. An awful instant of silence. Then a voice came into my ear. A frightened voice.

"Do you," asked the voice, "find things?"

I got control of my vocal chords. No bleating this time.

"Find things?" I boomed in hearty reassurance. "Mister, Kendrick's Agency can find anything from a shirt stud to the Lost Book of the Bible. Sure we can find things. What've you lost?"

"My body," said the voice. "I've lost my body."

"Well, rest assured, sir," I began. And then his words sank in. "What?" I yelled.

"My body," said the voice. "I've lost it. I really think it ran away on purpose."

I SHOULD have hung up then and there. But I was too sick, too

thoroughly disgusted, to think.

"And who in the hell are you?" I shouted.

"My name is Devlin, Arthur G. Devlin," said the voice eagerly.

I got even more incensed. Arthur G. Devlin, eh? Why didn't the joker pick Franklin D. Roosevelt while he was at it. Arthur G. Devlin, the town's richest, screwiest young man-with-father's- fortune. Arthur G. Devlin, who had all the money anyone needed and who drank goat's milk and walked around his fifty room mansion in a bedsheet, while he pondered how he could best dispose of the accursed fortune he'd fallen heir to.

"So," I said sweetly off my nut in rage, "you're Arthur G. Devlin, eh? You're the city's millionaire Mahatma, eh?"

"Yes," said the voice, "and I've lost my body."

"That's fine," I snarled. "That's just too ducky. Come up and see me some time and we'll talk about it."

I slammed the receiver back into the hook so hard I almost broke the thing. Then, still steaming, I grabbed for my hat, got up and stormed for the door.

I was muttering to myself as I waited for the elevator. Muttering and wondering who in the hell the practical joker could be. I had a hunch it was someone in the cigar store crowd downstairs. The call had probably been made right from the booth down there.

Stepping out of the elevator and into the lobby, I had a wild impulse to tear into the cigar store, demand to know who the joker was, and wring him dead with my hands around his neck. But I knew that wouldn't help, and I knew that the hoots and laughter of the crowd in there would be all I'd need to work myself into a seat at the Laughing Academy.

I was mad, sick and disgusted, and brimming over with self woe. There was only one solution to my problems. A drink. I left the office building and went around the corner to the closest bar.

Inside, I was all set to give my order to the barkeep when I remembered to count the change in my pocket. It was all the money I had in the world.

I had sixty-seven cents. Enough for a package of cigarettes and a scotch and soda. Or enough for the cigarettes and five beers. This didn't buck me up a bit. Hell, even in the corniest of private detective novels the gumshoe always has enough dough to buy a bottle of twenty year old stuff when he feels low.

"Gimme a beer and a package of cigarettes," I said.

Try lifting your spirits on beer sometime after you've been used to the heavier stuff. Just try it. All told, I had three beers, two cigarettes, and a blah-feeling in my mouth when I walked out of the place.

And twenty cents.

I was beginning to understand why people tried to rob banks, and beginning to speculate as to how you'd go about it.

FOR maybe half an hour I wandered around looking in store

windows and finally wound up in front of my office building. I

was tired. I wanted to sit down. I still owned a desk and chair

upstairs, so up I went.

Opening my office door, I took my usual glance under the mail slot, and got the usual bang out of seeing nothing there. I took off my hat and threw it on the couch. And then, from nowhere, a voice said:

"I hope you didn't mind my waiting for you."

I wheeled around, unconsciously blurting: "Huh?"

"You said to come and see you. You said we'd talk it over," the unseen voice said tremulously. Then it added, as an afterthought, "I'm the man who lost his body."

"What is this?" I bellowed, "another gag?"

I stepped quickly to the wash-closet and swung open the door. There was no one inside. I wheeled again, glaring around the office. I was the only one in the office.

There wasn't anyone else present. My eyes told me that. My common sense told me that. Everything told me that—except the voice.

"Naturally, you're startled," it said. "Naturally," I began. Then: "What in the name of all that is NOT funny, is this?" I screeched.

"I," said the voice with tired patience, "am the man who called. I am Arthur G. Devlin. I have lost my body."

"Where are you?" I demanded.

"Over here. Sitting at the end of the couch."

I looked at the end of the couch from which the voice seemed to come. Then I looked at the other end of the couch. There wasn't a soul on any part of the couch. There still wasn't a visible thing in the office.

"Of course you can't see me," said the tired, patient voice. "That's because I have lost my body."

I found a chair and sat down weakly.

"Look," I muttered hoarsely, "this has to be a joke. It's not a funny one as far as I am concerned. But I'll laugh. I'll promise you I'll laugh my fuzzy little ears off if you'll only, only admit it's a gag and tell me how you did it. I don't want to lose my sanity."

"Mr. Kendrick," said the voice, "why does it have to be a joke? Do you consider yourself to be an intelligent man?"

"Sure I do," I answered. "Intelligent enough to know—"

"Everything about everything?" the voice cut in.

"No," I said. "No. Of course not. I didn't say that. But—"

"Do you know of anyone in history or alive today who knows everything about everything?" the voice demanded, cutting in again.

In spite of the state of my emotions, I found myself arguing with the damned voice.

"No, of course not," I said. "No one knows everything about everything."

"Would you say that in this world there is a tremendous amount of knowledge as yet untapped?" the voice asked.

"Sure," I said. "I'll admit that."

"Does anyone know enough to say I couldn't lose my body?" asked the voice.

"No."

"And you are talking to me right now, and I don't seem to have what we humans call a body, do I?"

"That's right," I muttered desperately.

"Then you are not admitting insanity by admitting that I could have lost my body, and am talking to you right now?" the voice persisted.

I nodded my head in a very weak affirmative.

"Good, then," said the voice. "I beg of you, accept this fact. Through a process of reasoning, your sanity will now allow you to do so, won't it?"

I stood up. "I guess it will," I admitted. "But do you mind if I have a smoke and think this thing over?"

"Take all the time you need," said the voice patiently.

NONE too steadily, I managed to light a cigarette. I took the

first drag when a thought popped into my head. I turned to where

the bodiless psyche was supposed to be sitting.

"Listen," I said, "didn't you tell me that you are Arthur G. Devlin?"

"I am," said the voice.

"Then," I declared, "if I am going to believe you are a disembodied psyche walking around loose—and it looks like I'll have to believe that—I certainly can't get any deeper into this thing by believing that you're Arthur G. Devlin."

"Thank you," said the voice. "I realize that identification is somewhat difficult under the circumstances, but in due time I shall prove to you that I am who I say I am."

I crushed out my cigarette and started pacing. Sure I realized I had just resolved to take all this seriously. Of course I knew that it was more than a little psychologically dangerous to go walking back and forth in your office talking to a voice that didn't have a body. But it was better than admitting I was going nuts. And besides, if this thing was actually happening, not some loony's nightmare, and this guy, or voice, was Devlin—

"Mr. Devlin," I said, taking a deep breath as I dived in for good, "I'm willing to help you. You can see from now on in I shall not doubt, or question, what has happened or will happen. I'm all for you, and the immediate reconciliation between you and your body. I have accepted you as a client, and I'll see you through this terrible mess." I took another deep breath. "It is my first duty, to work best for your own good, to ask you for a retainer."

There was a moment's hesitation, then the voice said: "Naturally, Mr. Kendrick. However, I could bring no money, of course, being but a psyche. But if you could give me a pen, and a blank check."

I got the pen and the blanks check in less than a minute. I put them somewhat gingerly on the desk.

"Think you can manage?" I asked. "I mean, without a body and all?"

"Oh yes," the voice said. "Quite nicely, thank you. Don't be alarmed, however, at the sight of a pen apparently moving without a hand or body to guide it."

In spite of myself, the next scene was alarming. The pen rose through sheer air of its own accord, shook for ink, then dipped down to scratch a sum and signature on the check. Then the pen settled down quietly on the desk again.

"There," said the voice. "My bank is still open. You should be able to cash this. Will the amount be sufficient?"

I moved over to the desk and looked at the check. Shades of Perry Mason—it was made out for one thousand bucks!

"Yeah, sure," I said as casually as I could. "It'll do as a starter. However, if—I mean—I get your body back for you, I'll expect—"

The voice cut me off. "Shall we say another four thousand?"

I caught hold of the edge of the desk to steady myself.

"Yeah," I mumbled. "Yeah, fine."

Glancing down at the signature, I saw that it was that of Arthur G. Devlin, all right. If I were going crazy, it was fun.

"Now," said the voice, business-like, "I expect I'd better begin at the beginning and tell you how this thing happened, hadn't I?"

I folded the check carefully, put it in my utterly vacant wallet, placed the wallet next to my heart, and took a seat.

"Go ahead," I told him, "shoot."

"IF You know anything of my personal past, Mr. Kendrick," said

the voice of Arthur G. Devlin, "you will understand that the

press and other unkind and unthinking members of this city have

called me an eccentric, a—a screwchain, I think they

called me."

"Screwball," I corrected him.

"That's right," the voice agreed. "Nevertheless, ever since my father died and left me his quite considerable fortune and the large mansion that goes with it, I have come much more severely under the attention of the press and consequently the public. It has therefore been very difficult for me to have any private life, and equally hard to avoid the mockery of an ignorant world."

"Uh-huh," I contributed.

"You see," young Devlin's voice went on, "I was always scholastically, academically inclined. I had a fervid wish for as much knowledge as any man can obtain. My readings, studies, experiments and whatnot at school, and when I came back here after my father's death, were all unusually directed. I experimented, in my search for Truth, with Yogiism, the teachings of the great Confucius, and many others." His voice became recollective. "At one time I even delved into devil worship to see what it was about."

"Just for the hell of it, eh?" I punned. The voice went on. "My last experiment has been with the truths and teachings of Buddha. From the Great Teacher, I learned to live according to several precepts that brought additional scorn upon my brow from the press and public."

"You mean the goat's milk and bedsheet routine?" I asked.

"Yes," the voice acknowledged a little coldly. "I mean the simple life, the life of contemplation." The voice paused. "I will get more quickly to the point, however. You see, one of the truths expounded by the Great Teacher, is the value of the contemplation of infinity."

"Uh-huh," I broke in, just to give him part of his thousand bucks worth.

"In contemplation of the infinity, an art that is practiced daily by millions of Buddhists over the world, incidentally, one sits on the bare floor, legs crossed beneath him, head bent, and his entire being brought into concentration on one object."

"Like the navel?" I broke in.

The voice of young Devlin was reproving. "Z chose to give my being over into all encompassing contemplation of a wart on my chest," it declared. "However, that is neither here nor there. The fact is, that I began to practice this rite of concentration."

"Often?" I asked, for no reason other than curiosity.

"Every day," said Devlin's voice. "Four hours a day."

"I see," I said, and tried to sound knowing. "And how did it work out?"

"Fine," said the voice, "at first. For the first week of it I got along splendidly."

"Concentrating on the wart every time?" I asked, as if making a mental note of that.

"Every time," the voice assured me. "But on the seventh day of the week, I surpassed myself, and perhaps surpassed anyone who'd ever attempted infinite contemplation before. I got off into the infinite so utterly, so completely, that I got away from my finite being entirely. I divorced my soul, my psyche, through contemplation of the wart, absolutely from the mere flesh that is my body."

I NODDED, grunting noncommittally, but nevertheless

fascinated.

"When my four hour period was ended, I emerged from my contemplation to find that my body had walked out on me while I was off in infinity," the voice said, suddenly sick and frightened again. "It had left deliberately, I know, for it left a note for me!"

I almost fell out of my chair at that one.

"It left you a note?" I gagged. "You mean your body not only walked out on you, but it left a note, just like an angry wife?"

I could sense the voice nodding with sad solemnity. "Yes, Mr. Kendrick. Exactly that," it said.

I had a burning flash of inspiration, or common sense.

"Then the note must have said why it walked out on you, eh?" I asked.

"Precisely," said the voice. "Of course I do not have the note with me, but I memorized it verbatim. I shall quote it to you, exactly as I read it."

I leaned forward, not even thinking to light a cigarette.

"Go ahead," I begged. "Go right ahead."

"Understand," said the voice, and I detected a bit of embarrassment in it, "I am quoting. Any opinions stated by my body are not necessarily my own, you understand."

"Of course," I agreed, mentally tagging a new one for the books.

"The note said," the voice went on, "precisely this. 'Dear Sap: I am sick and tired of standing for the jackass life you lead. You and your mind—bah! Doesn't it ever occur to you that I'm a young, not-too-bad-looking body with a lot of life and a love of fun? Don't you think I'd like a drink once in a while, like other bodies? Don't you think I get tired of goat's milk? Don't you think I feel damned silly traipsing around in a bedsheet when all the other bodies I know are dressed up fit to kill? Don't you think I'd like to snuggle with a blonde in a taxi? Don't you think I'd like a cigarette, or a swim, or a big, juicy steak dinner? Don't you think I rate as much attention as that damned mind of yours? Don't you think I got feelings?'" The voice faltered on this, then picked up to the conclusion. "'Don't you think I'm coming back, either. I wouldn't have you for an owner if you were the last person on earth. So long, dope. Your Body'." The voice stopped abruptly.

"And that was the note?" I demanded.

"Exactly as it was written," young Devlin's voice said.

Now I lighted a cigarette. I needed it. I took a deep drag and tried to look pontifical.

"That sounds like your body was distinctly fed up with the kicking around you've been giving it," I said.

"But the Great Teacher," the voice began plaintively.

"Nuts to the Great Teacher for a few minutes," I said. "Is your body important enough to you for you to want it back?"

"Oh, my yes!" exclaimed the voice.

"Then the best thing to do is to forget the Great Teacher and physical subjugation or divorcement and all that sort of stuff," I said. "It obviously can't bring back your body, and undeniably was the original cause and final effect which lost you your body."

"I—I never thought of it quite like that," the voice said.

"Well you've got to think of it that way now," I said. "Anyway, if you want to get your body back you have to."

"Do you really think, Mr. Kendrick, that you can get my bo—" the voice began with pathetic eagerness.

I PUT on my best Perry Mason look.

"I can promise nothing definite, Mr. Devlin, except that I'll see my clients through to the end. We will see what we will see. Any idea where your body is now?"

Verbally, the voice shook its head. "No. I haven't. Not the slightest."

"That's not much trouble," I assured him. "I'll find your body, never fear, because I've a hunch it'll be conspicuously out for the fun you've denied it. In the meantime, you go home and lie down, or whatever you do in your present condition, and stay put until I call you. Understand?"

"Yes," said the voice meekly. "Yes, Mr. Kendrick. I will." It paused hesitantly, then added: "When will you call?"

"Just as soon as I locate your body," I said.

"Oh yes, sir," said the voice gratefully.

"And in the meantime," I added, "concentrate on forgetting that mumbo-jumbo you've been filling your noodle with. Throw it in the garbage can!"

"What?"

"Get rid of those ideas you had," I amplified. "You've got to have a complete change of heart, and honest one, in regard to your body, if we're going to get anywhere with getting it back for you."

"Oh, yes, sir," said the voice.

"So long then," I said.

"Goodbye," said the voice.

I looked expectantly at the door for a minute. Nothing happened.

"Are you gone?" I asked aloud.

There wasn't any answer. I got a brief chill. The damned disembodied psyche had probably walked right through the door. I took out my wallet and looked inside for the check. It was still there, and the ink hadn't evaporated. I felt better, much better, and looked for my hat. I didn't want to get to the bank too late. ...

THE check was as good as gold. It was, in fact, even better

than that. It was good for ten crisp one hundred dollar bills.

More dough than I'd made in eight months with my jerk agency.

I didn't go back to the office. I went right to my hotel. I have a hunch my room had been locked and I'd been spotted for the heave-ho, for the leer on the face of the desk clerk as I sauntered up to get my key was cold poison.

"Got my bill handy?" I asked. Nonchalant. Jaunty. Nick Charles, that was me.

The poisonous leer slid from the clerk's face, and an obsequious smirk took its place. I peeled off a hundred dollar bill from my wad while his eyes bulged, paid up the back rent and enough to cover the end of the week.

"I'm leaving this rat trap then," I told him. "Moving to the Astor, where I can get some service."

Up in my room, I sat down by the telephone, fixed a drink from the bottle, glasses, ice and seltzer I'd ordered sent up, lighted a smoke, and settled back to do business over Mr. Bell's baby.

I called three gumshoes who were employed part time by some of the big agencies. None of them was busy for the evening. It took a little fast talk to convince them I really had the green stuff to pay off, but I hired them for the next eight hours to comb the town for Arthur G. Devlin's body. I didn't say body, of course, I just said A. G. Devlin. At ten bucks a crack that made thirty smackers expenditures. I marked it down on a little tab, thought a minute, added the bottle and seltzer, and wrote underneath, "Initial expenses to be paid by client."

Then I dialed another number. Gloria Allen's. Gloria is a sweet looking blonde hussy who's a free-lance female operative for some pretty big outfits. We'd been friends since we worked in the same Miami gumshoe office away back.

"Look, baby," I told her. "Will you stand by for a job tomorrow for me?"

"Sure, Mike," Gloria agreed. "Just so long as it isn't a divorce mess. I don't do those, you know."

I was slightly indignant to think she figured a divorce plant case was the level I'd hit. But I calmed down because she was a slick little operative, and pal enough not to have questioned my ability to pay.

"I'm not sure if I'll need you, baby," I said. "But stand by, and I'll pay you for the day anyway, even if I don't."

"You don't have to do that, Mike," Gloria protested.

"Skip it, kid," I told her magnanimously. "Your uncle Mike has struck it rich. I'm cooking with gas, and I do mean helium."

When I'd hung up, I called Room Service and ordered Lobster à la Newburg, champagne, and a few other dietary necessities. Hell, after three months of cheeseburgers and soup, wouldn't you?

Then I prepared to settle down for some luxurious relaxing. I'd told my three operatives to call me in my room the minute they found the body, and I had nothing to do but sit back and wait for action...

THE telephone rang at ten o'clock. It was Farrell, one of the

gumshoes I'd assigned to the near north side of town. He'd found

the body, draped around a bar between two blondes in a clip joint

on Rush Street. It was buying drinks for the house, and the

management was tabbing up the bill by multiplying the actual

numbers of customer there.

I got on the phone the minute Farrell rang off. I called Arthur G. Devlin's home. A butler answered.

"I don't know if the master is in, sir," he said. "I haven't seen him in many hours."

"Ring his private study, or whatever he uses for his aloneness," I advised. "Maybe you'll find him there."

There was a pause, a buzzing, a click, and the voice came on.

"Hello?"

"This Devlin?" I asked.

"Yes. Mr. Kendrick?"

"We've found your body," I said, "at a north side bistro. It's having a fine time and definitely not wishing you were there."

"Oh!" the voice was elated. Then, as my words sank in. "Oh, my!"

"This is the address," I said, giving it to him. "Can you manage to get over there inside of twenty minutes?"

"Yes. Yes, I think so," the voice said. "I mean, I'll have to, won't I?"

"You bet you will," I answered. "I'll meet you out in front."

Then I hung up and looked around for my hat. I felt very fine. Very fine indeed. I was within a few short hours of another four grand. I thought....

I MUST say that the disembodied psyche of Arthur G. Devlin

made good time in getting to the bistro on Rush Street. I had

scarcely stepped from a cab in front of the joint, when his voice

whispered in my ear.

"Don't be startled, Mr. Kendrick," the voice hissed, "but I'm here."

"Okay, okay," I muttered, so the doorman wouldn't think I was happy-headed, "just follow me along, and don't speak until I tell you to."

I could feel Devlin's psyche fall in a little behind and beside me as I walked into the night club. Then I saw Farrell.

The gumshoe was sitting at the end of the bar, morosely sipping a beer. He saw me, clambered from the stool, and came over.

"Where is he?" I asked.

Farrell jerked his thumb to the right. "In the men's powder-room," he said.

"Those are the dames he picked up." He pointed to a pair of painted blonde cuties giggling near the center of the bar.

I saw that there were booths which a person had to pass on leaving the men's washroom. Several were vacant.

"Okay, chum," I thanked Farrell. "Drop into my office tomorrow with your expense sheet and I'll pay off."

Farrell nodded, and obviously relieved, left.

I made my way to one of those booths on the aisle near the washroom. I could still sense the presence of the disembodied Devlin tagging behind.

A waiter came up when I'd settled in the booth. I ordered a couple of scotches, double, and he went away to that never-never land where all waiters kill time when you're waiting for drinks.

"Okay," I said aloud. "Are you still here?"

The voice answered right beside me, and I jumped.

"Yes, I'm here. Are you sure this is the place? I don't see my body anywhere," it said.

"Never mind," I said. "It's here. Wait a minute."

We didn't even have to wait that long. I heard the door of the men's washroom open and a loud, slightly fogged voice singing.

"Hang on," I said. "Here comes your body."

I leaned out of the booth and peered down the hall to the washroom. Sure enough, there came the body of Arthur G. Devlin, weaving ever so slightly and grinning with vague happiness from ear to ear.

I jumped out of the booth and stood squarely in the path of Devlin's approaching body. It was a surprisingly well-knit body, more than the newspaper pictures I'd seen of it had indicated. And not bad looking, either. Tall, wide-shouldered, black hair and regular features, plus a flashing smile that had probably never been used before.

The body blinked at me when it got within a few feet, started to step around me.

"Hey there, Dev," I said. "Don't you recognize me?"

A STALL, of course, but I was counting on the body being

plenty oiled by now.

Devlin's body blinked uncertainly, while an amiable grin crossed its pan.

"Can't say I do," it said.

"We were supposed to have this drink together," I said. "The waiter's bringing it now." I took said body by the arm and steered it boisterously to a seat in my booth. Then I sat down across from it.

"Who're you?" Devlin's body asked amiably.

"A friend of a very good friend of yours with whom you've had a grave misunderstanding," I said, digging right in.

"Whosh that?" the body demanded.

"The mind and personality psyche of your lawful owner, Arthur G. Devlin," I said quickly. "I'm here to act for him. He's sorry he did what he did. He's changing his life completely. From now on he'll think with more consideration about you, old man. In his new resolve, you'll be just as important to him as his mind."

The expression on Devlin's body's face changed completely. The amiable grin was gone. Truculence took its place. Slightly woozy, but definitely stated belligerence.

"Zat so?" the body demanded. "Zat so? Well tell that sap I meant what I said in the note. I wouldn't have him as an owner if he was the last guy on earth!"

"Now look," I said pleadingly. "Think this over. You can't get along forever without him. After all, he's got the mind and all the intangibles. You'll need them sooner or later. Besides, he's reforming!"

"Why?" asked Devlin's body with a belligerent eyebrow arch. "Why should I need him? Getting along fine now, aren't I? Enjoying myself, aren't I? Having fun, aren't I?"

"Yeah, but—" I began.

"Nuts!" glared the body. "Tell him he can never get back in me unless I want him to. An I don't want him to. To hell wish him!"

The body started to rise from the booth in angry departure.

Then the voice sounded shrilly supplicating.

"Please! Listen to reason! I'm sorry for what I did. I'll treat you much, much better, so help me!"

The body paused in mid-rising, glaring wildly around the booth.

"Hah! So the little sneak was here alla long, eh? A trap, eh? To hell wish you both. Remember what I said. He can't get me back unless I wan'im, and I don't wan'im to, see?"

And with that, the body of Arthur G. Devlin took its indignant departure. The small, pathetic moan beside me showed exactly what my client's emotions of the moment were.

"To hell with the drinks," I said dispiritedly. "Let's get out of here. We've definitely lost the first round."

I got up, and followed by the spiritual psyche, or whatever you want to call it, of my client, made for the fresh clean air. Outside, I had the doorman call a taxi. I'd almost forgotten my client until the cab started off. Then the voice spoke from somewhere beside me.

"What on earth can we do next, Mr. Kendrick?" it asked plaintively.

I TRIED to think of an answer that was worth part of the grand

I'd already gotten. I rubbed my chin reflectively, like a good

gumshoe does in the cinema.

"We've only hit your body with what it doesn't take to," I said. "We obviously approached it from the wrong angle. The memory of bedsheets and goat's milk is apparently still too strong to lick. Our next step should be from the angle of something your truant body really goes for."

"Such as what, for example?" asked the voice eagerly.

"Blondes," I said, thinking of Gloria Allen, and what a million times cuter she was than the two wenches Devlin's body had picked up in that night club. "Lovely blondes."

"Oh," said the voice. "Oh, my!"

There was a silence. Then something occurred to me.

"Say," I said, "would it be a help to you if I had this cab stop at your address?"

"Oh, yes," said the voice. "A very great help. It's not too easy getting around like this, you know."

I leaned forward, tapped on the glass, and gave the driver the address of Devlin's mansion. He frowned, but changed directions at the next corner. I settled back again. Then the voice piped up.

"You know, Mr. Kendrick," said the disembodied psyche, "what you said in there to my body strikes me as being happily true."

"Huh?" I asked. "What was that? What did I say?"

"You said my body couldn't get along without me and my brain—I mean, my mind. That's perfectly true."

"I don't want to crush your spirits," I declared, "but you've no idea how many million human beings are running around this earth without a brain cell working."

"Oh," said the disembodied psyche. It then subsided into gloomy silence.

It was another five minutes to the Devlin mansion. The cab pulled to a stop.

"Stay at home again tomorrow until I call," I instructed. "Good-night, Devlin."

"I will," the voice answered. "Good-night and thank you, Mr. Kendrick. I shall keep courage. I have faith in you."

Then I felt that the disembodied psyche of Our Town's screwiest young citizen was gone. I leaned forward and tapped on the glass. The cabbie turned around.

"Drive on to the first address I gave you, chum," I shouted.

He gaped at me as if I were nuts, and I settled back on the cushions, by this time almost ready to agree with him ...

BEFORE climbing between the sheets back at my hotel, I called

Gloria Allen, told her to hop over to the place where the body of

Arthur G. Devlin was carousing, and snare it away from the two

blondes who had it in tow.

"It won't be hard for you, baby," I told her. "He's wild about women, and you're aces over the hay-bags he's with now. All I want you to do is make a date with him tomorrow before he heads to wherever he calls home. Make the date for luncheon, if you can, then call me in the morning."

"You flatter me all to pieces, chum," Gloria said. "However, I'll do my best."

Then I was able to drop off to sleep certain in the knowledge that Gloria was on the job, and that come heaven or high water, she'd have a date with the truant physical self of Arthur G. Devlin for tomorrow noon.

That was something, anyway, I told myself. And after half an hour of counting disembodied psyches chasing bodies over a fence, I fell asleep.

MY telephone rang at exactly eight o'clock the following

morning, waking me up.

I bundled out of bed and grabbed for the telephone, wondering who in the name of all unholy could be calling me at this hour.

The voice that came to my ear belonged to no one other than Arthur G. Devlin, or at least the disembodied psyche of same.

"Mr. Kendrick?" the voice asked.

"Speaking," I said. "What's on your mind, Devlin? Something come up? Your body wander home tight?"

"No, no nothing like that," said the voice dispiritedly. "It didn't come home at all. I presume it is living at a hotel now, anyway."

"Then what's wrong?" I demanded. "Why the early morning siren?"

"I have been thinking," the voice began tragically.

"I told you not to!" I cut in. "You've done too much of that already. It's responsible for the mess you're in now."

"I have been thinking," the voice repeated with firm but beaten weariness, "about the entire tragic affair. I was unable to sleep at all last night, through thinking about it, and I have resolved not to trouble you nor anyone else with my problem any longer."

"What?" I demanded. I had a horrible vision. The vision of four thousand bananas vanishing into thin air.

"I have decided to go away, far away. I have decided to give up this futile struggle to recapture my body. It wants none of me, and I feel I shall never again own it. I have decided not to struggle any longer, Mr. Kendrick. I shall let my body go on as it pleases, while I take myself off to unknown lands."

"Now listen," I said frantically, "don't talk that way. That's nothing more than sheer defeatism!"

"Perhaps so," said the disembodied psyche of Arthur G. Devlin, "but didn't the Great Teacher, Buddha, say that in defeat and resignation to one's destiny lies the only true—"

"Hey!" I broke in. "Tie a can to that stuff! Forget the Great Teacher, can't you? Didn't you promise to get the right mental angle on all this?"

"I did," said the voice wearily, "only to be spurned by my own body. It will never believe me. So why should I strugg—"

"Look," I cut in again frenziedly, "give it a little more consideration than that, won't you? After all, you've only given me one crack at the problem."

THERE was a moment of reflection on this. Then the voice came

through again.

"I had made up my mind to leave this morning, Mr. Kendrick, to go away forever. But I will make one small concession to your arguments, even though I 'feel I am right in thinking we cannot succeed. I shall not leave until six o'clock this evening. But if we still have not succeeded, I will follow the logic of the Great Teacher and vanish, leaving the triumph to my body."

"But listen," I almost shouted, "just until six tonight isn't any time at all. Be reasonable!"

The voice sighed. "That is as reasonable as I can be. I shall stay here waiting for a call from you throughout the day. But if by six, we are still unsuccessful, I shall leave forever."

"Now, Devlin—" I began.

A click told me that my disembodied client had hung up.

I felt sick. Terribly sick. Four thousand berries—poof, like that! I sat down on the edge of the bed, hating Buddha as he has never been hated before.

Then the telephone rang again.

I picked up the cradle phone, and Gloria Allen's voice came to my ears.

"Good morning, Sunshine!" she sang.

"What's good about it?" I demanded.

"Everything is good about it if you ask that young Arthur G. Devlin rogue you sicked me onto," she answered.

"Huh?" I demanded.

"I snared him from those other blondes last night," Gloria said, "and got stuck with him from night club to night club until two. Then I shook him, hinting coyly at a luncheon date for today."

"Did he nibble?" I demanded.

"Nibble?" Gloria giggled. "He insisted that it be both breakfast and luncheon. He just called from the lobby of my hotel downstairs to remind me he's waiting for toast and coffee in the main dining-room. He also says not to forget the luncheon. I don't think he went to bed. Sounds as if he's still half tight. I'm getting ready to go down and meet him now."

"Well," I said. "Well. I must say you work well, baby. What do you think of him?"

"Kinda cute," said Gloria. "Not at all like the stuff you read about him in the papers."

"I could explain the reason for that," I told her, "but it would take too long."

"I wouldn't believe you anyway," she laughed.

"Baby," I said, "you aren't kidding."

"Well, after breakfast, what'll I do with him?" Gloria asked.

I thought a minute. "Keep him at breakfast for an hour or so if you can," I told her. "Then take him for a walk and bring him back to your hotel bar along about ten o'clock or so. Hang onto him there until I give you a ring."

"Sure thing, chum," Gloria said.

I HUNG up and beat my palm against my brow frenziedly. There

being no sleep now, with four grand hanging in the balance and no

solution in my mind other than feathers, I began to get dressed.

As I did so I turned over every single angle of the mess I could

think of. I jabbed at each angle from every side.

At the end of the frantic brain scraping, I was left with just the same two obvious conclusions I'd had at the start.

The body didn't want the psyche, under any circumstances that I could figure.

And unless the body wanted to admit Devlin's psyche back into it, there was no soap.

Problem: To get the damned body to want to have the damned psyche and mind back in it. Extra grief: To do so before six p.m. today.

Solution: ?

I went downstairs, ate a half-hearted breakfast, grabbed a cab and went over to my office, under the delusion that I might think more clearly there. Two hours pacing back and forth in the narrow confines of my toil cell turned up exactly nothing in the way of bright ideas.

It was almost noon when I stamped out of my office. I stopped downstairs, when it suddenly occurred to me, and telephoned the bar at Gloria's hotel.

"How're you doing, baby?" I asked.

"Fine," she said. "Just fine. He's sobering up a little, believe it or not. I think he's getting a crush on me, chum."

"Let him do both if he wants to," I said. "Only please, for gawdsake, keep him there a little longer, will you?"

"Okay, chum," Gloria said. "Incidentally, he has a tremendous wad of cash on him. I have to make him stop throwing it around in spit balls every half hour or so."

"That's to be expected," I said. "But keep him in hand, and there, will you?"

I hung up then, and went out into the street. Again I was back in the ring wrestling the python-like problems of Arthur G. Devlin and his disembodied psyche. My head was beginning to ache, and I turned into the nearest tavern.

SCARCELY two minutes after I'd ordered my drink, Jerry Stavers

came in and took the bar-stool next to mine. Jerry was WHAL's

star on-the-spot announcer. I'd known him for two or three years,

hadn't seen him in months.

It was old-chum-where-yuh-been stuff. You know the routine. I bought him a drink, and he bought me one. Then I bought one, and he parried my thrust with another round.

We weren't getting tight, you understand. Just four drinks, with Jerry blabbing away, and me trying to juice up my weary brain cells by thinking about something other than truant bodies and wandering psyches for a little while.

And then Jerry looked at his watch.

"Damn," he said. "It's one-thirty. I have to beat it, Mike. I have to announce a spot show at two."

I nodded, my mind back with Arthur G. Devlin and his troubles, and Mike Kendrick and his troubles, at the mention of the time element.

"What kinda show," I asked automatically, "and where is it to be from?"

Jerry was putting on his hat and starting for the door when he casually answered both my questions. For a split second I just stared at him. And then everything clicked. Clicked like it had never clicked before.

"Jerry!" I yelled, jumping from my bar-stool and grabbing his arm. "Listen, chum, and listen fast. You gotta do me a favor on that show of yours. A tremendous favor!"

And then I told him, repeating it a second time, slowly, emphatically, and finally making it positive with a third repetition.

Jerry was puzzled, and scratched his head over my wild insistence, but agreed to come through willingly enough. And the minute he left, I turned and dashed into the nearest telephone booth.

I got Gloria on the wire again, from her hotel bar. Frantically, I gave her double barrels of instructions. Making her repeat them to me twice after I'd spieled them.

"This is the most important part of the entire job as far as you go, baby," I said. "You've gotta put it over perfectly!"

"I'll do my damnedest, Mike," she promised.

My dear disembodied client, the psyche of Arthur G. Devlin, was the recipient of my next call. As I poured forth my instructions he was properly bewildered, but promised to do exactly as I told him. I gave him the name of Gloria's hotel, telling him to meet me in the lobby, which he solemnly pledged to do without fail.

Then, utterly exhausted, I slumped against the side of the telephone booth and said my prayers. I left the booth, stepped to the bar, and had a quick double bourbon. With four grand hanging higher than the proverbial goose, brother, I needed it ...

IT was exactly ten minutes to two when I walked into the lobby

of Gloria Allen's hotel. The lobby was fairly well crowded, even

for its enormous size, inasmuch as the hotel was directly in the

middle of the city's business district.

I loitered by the cigar stand, where I'd told the disembodied psyche of Arthur G. Devlin to meet me. Loitered casually, while I was an eleven alarm fire of excitement and sick suspense inside.

From where I stood I could see the bar entrance which led out into the lobby. Gloria and the body of Devlin would emerge through there, unless she crossed her wires.

The big clock on the lobby wall said precisely five minutes to two when a voice at my ear said:

"Here I am, Mr. Kendrick. Just as I promised."

It was the voice of the disembodied psyche of Arthur G. Devlin, of course. I didn't have to turn to see that.

"Good," I told him. "No, just stay put and keep cool. Remember this—. your body has to want you and your mind back before you can take over again. In the split second when it wants that, you have to act quickly, very quickly. Get me?"

"Yes. I understand. I hope it will work," said the voice tiredly.

"You aren't the only one," I muttered.

Bellhops were clearing a space in one corner of the lobby, and men with electrical equipment and cases and wires were moving things into the space provided.

The clock on the wall said two minutes to two.

It was then that Gloria steered the body of Arthur G. Devlin out the bar door leading to the lobby. She looked around casually, gave me a covert high sign, and moved with the truant body over toward the corner of the lobby where the equipment was being set up.

I saw Jerry Stavers enter the lobby then. He didn't seem to notice me, but went over to the cleared spot where the microphone was now being set up. He looked long and hard at Gloria and the truant body of Arthur G. Devlin as he passed them.

I spoke out of the corner of my mouth to my client.

"Come on, pal. This is it. We'd better mosey over to that crowd around the microphone in the lobby."

"Very well," the voice said.

And so, trailed by my disembodied client, I crossed the lobby until I stood on the fringe of the increasingly large crowd pressing in around the radio sound engineers, the microphone, and smiling announcer-pal Jerry Stavers.

I looked up at the clock on the wall.

Two on the dot!

Then the crowd was hushed by a signal from Jerry, and his locally well-known voice boomed out:

"WHAL presents 'Questions To the Crowd,' your city's own citizens' information please, in which your announcer, Jerry Stavers, tests the wits and good humor of folks everywhere around our town. We're broadcasting today from the lobby of the—"

And as Jerry went on, then into his commercial, I took a quick glance over to the left of the crowd around the microphone. There was Gloria, edging Devlin's truant body closer to the mike, while she was obviously saying something similar to:

"Go ahead. It will be fun. I'll bet you're smart. I couldn't stand a man who isn't!"

I grinned, and out of the corner of my mouth, said to my disembodied client, "Now get up next to the microphone and stand by all ready to dive in!"

"All right," said the voice, eagerly now, and I knew my client was wisping through the crowd to the microphone.

WHEN Jerry had finished his commercial, and was into his

opening glib chatter. I could see him eyeing Gloria covertly as

she worked her victim close enough for Jerry suddenly to reach

into the crowd, and grab the coat lapels of Devlin's startled

body.

"And here we have a young man," Jerry was saying swiftly, drawing Devlin's body closer to the mike, "who seems particularly anxious to answer today's first question to the crowd."

Devlin's body stood there looking trapped, eyes flickering uncomfortably toward the smiling Gloria on the fringe of the crowd.

"What is the most heavily populated country in the world?" Jerry asked Devlin's body.

I could sense Gloria's "I couldn't stand a man who isn't smart," running wildly through the body's recollection. It turned its eyes mutely toward the crowd, then back to smiling Jerry Stavers.

"Uh, would you repeat that question?" the body hedged.

"What is the most populated country in the world?" Jerry repeatedly blandly.

Devlin's body shifted from one foot to the other, glancing in covert shame at the lovely Gloria who stood a little away and was beginning to frown.

And then it happened. The look came into the truant body's eyes. That brief, desperate, frantically appealing look which said one sentence as clearly as if it had been written in them.

"Damnit! I wish I had that mind for just a minute!"

AND in that second, something made Devlin's body shudder from

head to toe for an instant. A long, deep, convulsive shudder. The

disembodied psyche had dived right in on the heels of that

wordless invitation in his body's eyes!

Suddenly, then, as suddenly as it had started, the shudder through the body of Arthur G. Devlin was finished, and Arthur G. Devlin, completely reunited with himself, psyche back in control of body, was answering Jerry Stavers' question with amused pity.

"Why, China of course, old man. Next is India, then Russia. Was that really supposed to be a quiz test?"

The crowd roared its approval, and smiling, Arthur Devlin moved away from the microphone and back into the crowd. Gloria took his arm, and he looked down at her curiously.

I hurried over to the two of them.

"It worked!" I yelped. "It worked! You're back in place again, old boy!" I reached out, took Devlin's hand and pumped it. He smiled and fished into his pocket, bringing out his wallet.

Opening the wallet, the once disembodied Devlin pulled out four thousand dollar bills as casually as an ordinary man might handle cigarette papers.

"You surely fixed it, Kendrick," he said, handing me the bills. "I'll be in to thank you in greater detail tomorrow or the next day."

I was gaping at the bills in my palm.

"Say," Gloria's voice demanded bewilderedly, "what on earth is this all about?"

I started to say something, but Devlin cut me off. He took Gloria by the arm.

"You know, I have a feeling I really don't know you well enough," he said, "even though I've supposedly spent a bit of time with you last night and today."

Gloria's laughter tinkled musically. "You say the darnedest things, Mr. Devlin," she said.

Devlin grinned. Not a bad looking young guy, Devlin.

"I've a feeling I'm way behind myself, however," he said. "I've got some time to make up for."

He slipped his arm around Gloria's waist, and the two of them headed for the bar. Very luscious blonde, Gloria.

I just stood there, almost surprised enough to have forgotten the four thousand bucks in my fingers. It was obvious that I was witnessing the exit of one of the sweetest, smartest female operatives in the business. But my professional regret was distinctly soothed by the fat fee I held in my hand.

For even to that big operator, Perry Mason, four thousand cash moola ain't hay!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.