RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

with "The Other Abner Small"

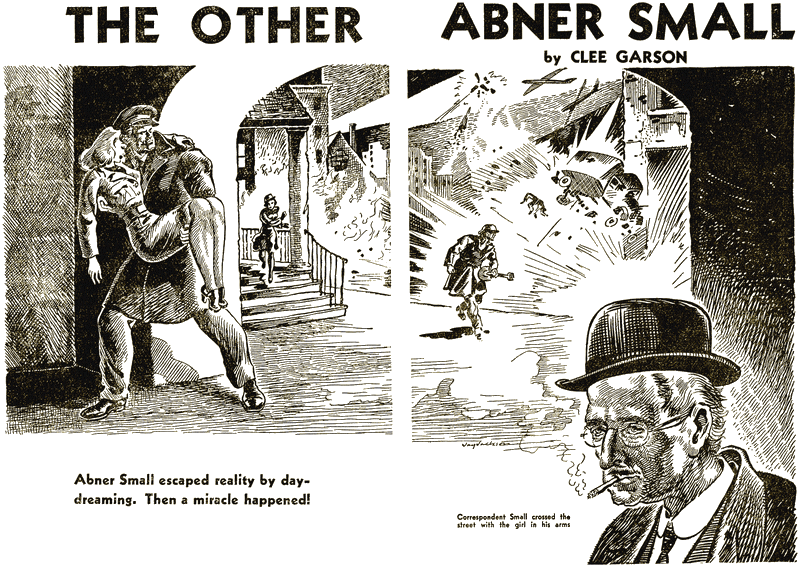

Correspondent Small crossed the street with the girl in his arms.

Abner Small escaped reality by daydreaming. Then a miracle happened!

COLONEL Abner J. Small, ace of the United States Army's Military

Intelligence Corps, waited calmly in the darkness of the deserted

warehouse, one hand deep in the pocket of his trenchcoat and

firmly grasping the butt of the service automatic that lay there,

while the other hand nonchalantly raised the glowing cigarette to

his sardonic mouth for a last draught of the warming smoke.

From the far end of the wharf on which the warehouse stood. Colonel Small heard the sound of the footsteps he'd been awaiting so patiently.

"That will be Yokomura, no doubt," Small thought coolly.

He smiled sardonically, and flipped his cigarette over the wharf edge with thumb and forefinger. It described a flaming arc in the blackness, disappeared over the pilings, then zzzzisssed out in the softly lapping waters of the harbor.

The footsteps on the wharf halted abruptly. A voice hissed forth, carrying to the colonel's ears.

"Is that you, Krauss?"

Colonel Small didn't move. He smiled as he hissed a reply.

"Ja, Yokomura, mein Herr," said the colonel. "It isss me, Krauss."

There was an audible sigh of relief from the Japanese spy. Then the footsteps started toward Small again.

Colonel Small stepped back ever so slightly into the even deeper darkness of the warehouse door. He almost touched the dead body of the Nazi blackguard, Krauss, whom he'd slain less than ten minutes before.

The colonel's hand tightened on the butt of the service automatic in his pocket. His lips went flat in a merciless smile, and with his free hand he pulled his dark civilian Fedora a little lower over his eyes.

The Jap spy, Yokomura, was only a few feet away, now. Ten, eight, six, four feet.

"Krauss, I have the plans for—" Yokomura began, now standing before Colonel Small.

The Jap Agent's hiss of shocked surprise was followed by Colonel Small's calmly contemptuous voice.

"Draw, you little yellowed weasel!" the colonel said.

The Jap's face was twisted with fear and treachery.

"Small!" he gasped. "The ace of U.S. G-2!"

"Did you expect," asked Colonel Small in a cold, mirthless chuckle, "to see Santa Claus?"

And then the Jap spy's hand flew swiftly to his pocket, and with the speed of a striking snake, the enemy agent held a gun trained on Colonel Small's forehead.

"Raise your hands, Colonel Small, you American dog!" Yokomura hissed.

Small smiled. "I should judge now," he said evenly, "that you have every advantage."

The colonel's lightning-like draw of the service automatic in his trenchcoat pocket was swifter, more miraculous than the speed of a fast shot camera.

He fired three times, and the Jap spy slid forward on the wharf planking before the colonel's feet. Yokomura's head, what was left of it, clearly revealed that all three shots had buried themselves, one on the other, in the center of the oriental's skull.

Colonel Small looked down at the slain enemy agent. His mouth was twisted sardonically, mirthlessly, again. He turned and looked back at the dead Nazi agent lying behind him.

"You were a little more trouble," he acknowledged, touching the chest wound the Nazi had inflicted on him before being killed.

BACK at the office of G-2, some thirty minutes later, Colonel

Small's entrance created a sensation. Smilingly, he passed

through the outer bull-pens and into the sanctum of the

general.

Five men were clustered around the general's desk. They were shirt-sleeved, haggard, obviously worried. Their attention, at the moment of Colonel Small's entrance, was centered on a disorderly melee of papers lying on the desk.

The general looked up.

"Colonel," he gasped. "You, you—"

"I turned over the bodies to the FBI, sir. I think that cleans out their nest."

Every eye in the room was on Small now. And every eye was filled with incredulous awe, ungrudging admiration.

"What's up?" Small asked, nodding at the papers.

The worry came back to all faces. The general answered.

"The intercepted code message, Colonel," he said. "We've been trying to break it for twenty-four hours straight. Damn it, sir, but I'm afraid we're licked."

Casually, Colonel Small stepped to the desk, reached for the intercepted message. He looked at it a moment, frowning.

"Mind my having a go at it, General?" Small asked.

"But good lord, Colonel, our best men in the deciphering department, the greatest brains in—" the general began.

But Small was speaking already.

"The Sentheby Breakdown formula, combined with the Idion- Greeby Frequency Count Reduction should do it," he said confidently.

The head of the deciphering department looked at him in shocked wonder.

"By God, Colonel, you hit on it! Why didn't we think of that?"

Colonel Small tossed the paper carelessly back on the desk. He smiled sympathetically at the overworked deciphering head.

"That's all right, old man, you can't be expected to think of everything."

It was then that the general rose from behind his desk, staring wide-eyed at the crimson splotch on the chest of the colonel's trenchcoat.

"Good God, man," the General cried. "You've been wounded!"

Colonel Small smiled sardonically.

"Have I, General?" he said.

Weak from loss of blood, Colonel Abner Small caught at the desk, then started to slump to the floor....

"MR. SMALL, Mr. Small!"

Little Abner Small looked up startledly at the sound of the voice, shaken from his daydream.

It was the sergeant behind the desk, and he beckoned with a pencil. A tall, erect young second lieutenant stood behind the seated sergeant.

Abner Small rose quickly from his seat along the wooden bench.

He walked over to the reception desk.

The sergeant smiled amiably. "The lieutenant will talk to you," he said.

The young second lieutenant moved over a little to one side, beckoning Abner to follow him. In a corner, they paused.

"I, I didn't hear the sergeant," Abner Small began apologetically. "I, I—" He was about to say that he had been wool-gathering, then he suddenly realized what a terrible impression such a confession would make on the lieutenant. After all, prospective G-2 applicants didn't wool-gather, or shouldn't.

"I, I didn't hear the sergeant," little Abner Small repeated foolishly.

"That's quite all right, Mr. Small," said the tall young second lieutenant. He had an amazingly friendly smile, and for an instant it warmed the hopes that beat so frantically in the small chest of Abner Small.

"I want to thank you for the War Department, Mr. Small," the second lieutenant said. "We appreciate your patriotism in offering your, ah, services to Military Intelligence, especially in view of the fact that you are beyond military age. However, we haven't any need at present for the background you offer. But please rest assured that we'll keep your name on file, and should we ever—"

The rest of the smiling young second lieutenant's voice was lost in a drone to little Abner Small. A sick, aching disappointment had closed its fist tightly around his heart and was squeezing for all it was worth. The squeezing was bringing a dampness to Mr. Small's eyes, and he didn't want to remove his horn-rimmed glasses and dry them there in front of the young lieutenant.

Dejectedly, little Mr. Small muttered something about thanks, and turned quickly away from the railing.

Once outside the doors of the Military Intelligence Office, Mr. Small peered beatenly around until he located the darkened corner in which he'd hidden his rubbers before entering the sacred precincts.

He found them, put them on, picked up his umbrella from the other corner in which he'd left it, and turned down the corridor to the elevators. Anyway, they hadn't sniggered at the rubbers and umbrella the way that young snipe at the FBI place the week before.

But that was small consolation to the sensitive soul of little Abner J. Small. Nor could he find anything pleasurable in the realization that this was perhaps the fifteenth time he had been turned away from innumerable such offices.

He had been to his draft board eight times, until they had finally forbade him to return unless, to quote the chairman, "this country is invaded."

An invasion! Mr. Small shuddered at the thought that the war would ever go so badly as that for his beloved nation. The elevator stopped and Mr. Small got on. Still, if there were an invasion ...

THE newspapers, those printed on the U.S. side of the lines,

this side of the Rockies, were full of the horrible news. Wave

upon wave of enemy ships and planes had made beachheads. And from

those beachheads enemy tanks and troops had crashed relentlessly

past the crumbling but gallant walls that had been our first

defense lines.

The names of the cities swept by the ravening hordes of the Axis were ghastly and familiar to even the youngest school children. Fighting, cursing, dying, grim-jawed U. S. troops were finding their numbers too small to stay the tidal wave of the crushing enemy invasion.

The situation was bad—and growing steadily worse.

"It's mad, sir. I know it's mad," the staff general said to the commander in chief. "But can we lose anything by it? After all, he has a long record of citations for bravery and tactical brilliance under fire. He'd be far more than a lowly private now, if he hadn't refused, time after time, the promotions offered him."

The commander in chief nodded gravely, albeit wearily. He sighed.

"You say the entire General Tactical Staff is behind the plans submitted by him?" The commander in chief asked slowly.

"To the last man, sir," said the staff general. "And to the point where we are determined to force him to take complete charge of his plans, as general."

"Then send him in," said the Commander in Chief.

The door opened then, and Private Abner Small of the United States Army, marched crisply into the room, clicked his heels, and saluted the commander in chief, and staff general.

"Private Small reporting, sirs," he said quietly.

"At ease, Private Small," said the commander in chief. "Have a cigarette." He extended a box of expensive cigarettes to the begrimed, ragged, helmeted figure.

"Thanks, sir," Private Small demurred. "I roll my own."

The staff general and commander in chief watched while Private Small drew forth a pouch of Bull Durham and a cigarette paper, marveled at the swift dexterity with which he rolled a cigarette.

After an instant, when the staff general had lighted Private Small's cigarette, the commander in chief spoke.

"I've heard much of your heroism under fire, Private Small," he said. "And of your modesty in refusing promotion."

"Have you, sir?" Private Small asked noncommittally.

"And now these plans of yours, Private Small," said the commander in chief, "have been called to my attention and to the attention of the General Tactical Staff. They think they are brilliantly conceived."

"They are direct," said Private Small, modestly.

"What is your opinion of the entire situation, Private Small?" the commander in chief asked, leaning forward. "Do you think we can fight on much longer?"

Private Small took a slow, thoughtful draught from his cigarette. He smiled sardonically, expelling the smoke as his words rang out crisply.

"If my plans are put into effect, sir," he said, "I will guarantee that we will have trapped and completely annihilated the enemy forces to a man within two weeks. In three weeks, sir, we will have their unconditional surrender!"

Both the staff general and the commander in chief gasped, eyes wide.

"But Private Small," the staff general said. "'Even with such a brilliant maneuver as you have outlined—"

Private Small cut him off quietly.

"You know my record, sir?"

The staff general nodded. "Of course. Everyone in Amer—"

Private Small cut him off again.

"Have I ever let the United States of America down?"

It was the commander in chief who sprang up, fire and admiration in his eyes, jaw hard.

"By God, Private Small," the commander in chief said fiercely, "I believe in you, sir, to the hilt. Your plans will be carried out—with you in the saddle!" ....

LITTLE Abner Small was jarred from his reverie by the sharp

voice of the uniformed female elevator operator.

"Thirty-second floor!" she snapped. "This is the top. We don't go any higher. Do you want to get off, or don't you?"

Mr. Small looked up like a frightened gazelle, saw that the elevator was deserted, and that the operator was glaring at him.

Mr. Small flushed miserably from the brim of his old-fashioned derby to the edge of his celluloid collar.

"I, ah. I'm sorry. I guess I must have gotten on the wrong elevator. I wanted to go down, not up."

"Why didn't you notice the light above the door on the floor I picked you up from?" the operator demanded. "It would have told you that this elevator was going up."

"I, ah. I guess I didn't notice," said Mr. Small. "I'm very sorry." He started to step out of the elevator.

"Might as well stay on," snapped the operator. "This will be the first elevator down."

Abner Small stepped miserably back into the elevator, realizing redly that but moments before he'd been Private Abner Small, U.S.A., whose keen analysis of every tactical situation was about to save the world.

When Mr. Small emerged into the crowded downtown streets some three minutes later, he saw by the clock on the Board of Trade Building that it was getting very close to six o'clock.

Allowing himself the necessary forty minutes it would take to get home, he realized that he would again be more than half an hour late to dinner, and that again his spouse, Velma, would be angered to the point of homicide.

Abner Small shuddered at this thought, and his weary little shoulders slumped even more. There would be no explaining to Velma the cause for his tardy arrival. There never was. And if she knew that he'd left his office—where he'd worked as bookkeeper for a nickel-squeezing firm of lawyers more than twenty years—half an hour early in order to be certain of an interview with Military Intelligence officers, she would berate him even more thoroughly.

Somehow, Velma had learned of her husband's attempts to enlist at his draft board—and the explosive verbal thunder that smote Abner's eardrums ever since was endless and agonizing to the little man.

And now, if she suspected that he was still trying—

Abner Small let the thought dangle, and squirmed more deeply into the crowds along the sidewalk, as if seeking physically to lose the mental wraith of his wife's anger behind him.

VELMA, plump, wrathful and sloppy, met little Abner Small at

the door of their humble dwelling one hour later. Somewhere along

the route, Abner had daydreamed again and gone six blocks past

his stop—hence the twenty minutes beyond his original

calculations.

She stood there with her hands on her large, unvenus-like hips, her round, unkempt bleached head cocked belligerently to one side while her angry eyes sparked forth the state of her mind.

"Hello, Velma," Abner said uncomfortably.

Velma watched him as he kicked off his rubbers and placed them beside the umbrella rack in the hallway. She opened up as he was slipping out of his coat.

"You bum!" she shrilled. "You ungrateful, shiftless, loafing bum!"

Inwardly, Abner Small sighed. Outwardly, he betrayed no expression. He started into the living room, his wife at his heels.

"I slave all day over a good dinner and you come home here almost an hour late!" Velma declared in the strident tone of one talking long distance without the aid of a telephone.

"What," inquired Abner mildly and automatically, "do we have to eat tonight?"

It was significant that Abner never voiced this query with any trace of hopefulness in his tone.

"Potato salad," Velma snorted indignantly, "and nice cold meats."

Abner was aware that Velma had again been to the delicatessen for their evening fare, but he didn't comment on this fact. On the table next to the sofa was a large box of gooey chocolates, or what had been a large box of the same. A glance showed Abner that his wife had made an overwhelming frontal assault on the box and consumed its contents almost entirely.

Thrown carelessly, back up, on the floor next to the couch, Abner saw the heliotrope cover of a love novel luridly titled: Playgirl of Passion.

"Well," Velma's voice came harshly to his ears, "what're yuh staring at?"

"Nothing," Abner answered, feeling utterly truthful in his reply. "Absolutely nothing at all."

He sighed and sat wearily down on the couch.

"Well!" Velma barked. "Are you gonna get yourself a nap, or are you gonna get out an eat your dinner before it gets cold?"

Abner rose. "Have you eaten?" he asked.

Velma nodded emphatically. "You bet your life I have. I'm not gonna starve myself because my bum of a husband suits himself about the time he comes home."

Feeling grateful for this small break, Abner went out to the kitchen where, on a table covered by last week's newspapers, Velma had set out his repast on plates that were scarcely clean.

Velma didn't follow Abner into the kitchen. She remained in the living room, a fact attested to by the sudden deafening blare of the radio announcing the presentation of the hundred-and- eighth in a series of slushy programs entitled: "Dear Reginald: How I Love You."

Velma never missed "Dear Reginald: How I Love You." It came over the airwaves at this time three sessions weekly, for one-half hour per session. It was Velma's favorite program, inasmuch as it stank far more putridly than innumerable similar programs aired daily through the kindness of soup and laxative peddlers.

Abner sat picking at his cold potato salad, thinking to himself that there was certainly reason behind the radio trade expression of "airing" a show. Most of them needed airing very badly.

After a few desultory swallows of the cold, canned mess of soup at his elbow, Abner put his spoon quietly on the table and began his nightly contemplation of fate versus Abner Small.

He began, as he always did in such remorseful relivings, with his marriage to Velma. Everything, paradoxically enough, seemed to start and end with that event.

How many years ago had that been? Abner found it hard to remember exactly. Too long, anyway.

Abner tried to remember what sort of a person he'd been back then. It was hard, very hard, to draw any accurate picture of what he was once like. He'd been a little gray mouse far too long now to enable him to associate any other type of character with himself. Abner had no delusions about himself as he now was. No delusions save those utterly glorious day-dreamings in which he escaped completely from reality. Without those daydreams, Abner knew, life wouldn't hold anything worth having.

When had he first started those blessed escapes through daydreaming? Abner tried to think back. He'd entertained daydreams, of course, for as long as he could remember.

EVERY man, every human being, Abner realized, had daydreams of

some sort. It was part of the stuff of human nature. But yet, his

own daydreams were far more sharp, far closer to an actual

escape from a sordid reality to a glamorous never land, than the

average. Of this Abner felt certain.

But that, he reasoned bitterly, was merely because he had far more reason to need complete escape than the average man. Sickly enough, Abner was aware that his present life was considerably less than that of the average person. And, even more sickly, Abner knew that it was scarcely anything less than his own fault.

Somewhere back along the drab scratch in the dust of humanity representing the line of his life, Abner Small had sold his birthright. When it had happened, or how it had come about, Abner wasn't quite aware. But it had happened. There was no doubt of it. And from that mark in his life he had started the all-too- easy slide that had ended with his present status.

Velma, Abner realized, was not entirely to blame. Velma was but a contributing factor. Had he had guts and intelligence and a sense of his own destiny, Abner would have thrown Velma out of his life long ago. She would have been the same sort of wife for whatever man she married, Abner knew. But how many men would have put up with a Velma past the point where her actual character began to show? Not many. But Abner had.

He had put up with Velma just as he had uncomplainingly put up with so many things in the hope that they would "iron themselves out in time." He had put up with the unfeeling treatment and slave wages of his employers in exactly the same fashion, hoping that time would remedy wrongs. And he had mentally and physically become one of life's walking doormats. A human floor on whom people thought no more of walking than they did on any floor.

Emotionally, however, Abner had never completely died. At least not yet. The emotional factors in any human being are harder to kill than his mental or physical factors. And so it had been with Abner. His emotions had stayed on after his mental and physical self-respect walked out in disgust at him.

Which didn't make things any easier for Abner. For with his emotions he could still feel pain, he could still rage futilely at his lot and sense the state into which he had fallen. His instinct and pure emotional balance made him all too keenly aware that he was no longer captain of his fate and master of his soul.

And yet, his emotions and instinct for things lost, permitted those wonderful dreams. And the dreams permitted him a hope that was all too agonizing because of their utter futility.

Abner pushed aside his plate.

From the living room came the affected accents of the heroine of Velma's favorite program.

"Richard, deah, deah Richard," said the voice of the radio actress, "if one must go forward as Reginald has, to do one's best against the storm of this great conflict, I would rather that you were a gallant birdman, my love!"

The young radio actor, who, Abner felt sure, was marcelled and perfumed, possessed a voice that was so utterly affected it must have driven his contemporaries mad with envy.

"I knew you would feel that way, Madeline, my sweet," the young radio actor lushed. "I must fly to battle—even though it means—"

Abner closed his eyes in sick disgust, blotting out the obnoxious voice. If that chap were ever to do any actual flying, Abner felt certain it would be out the nearest window and straight to a beauty parlor.

Abner put his head in his hands, and with his elbows on the table, slumped dejectedly, beatenly forward. His eyes were closed already, and now fatigue and weary monotony lulled him into a coma-like version of sleep ...

IT seemed hours later—though it was more a matter of

minutes—when some alien sensation snapped Abner back into

wakefulness. Quickly, bewilderedly, he looked around.

He still sat before the kitchen table. But something else was changed. He looked up at the clock on the wall. Almost forty minutes had passed during his nap. And then he realized what had seemed to be the alien circumstance. The radio wasn't blatting loudly forth as it inevitably was.

Abner rose from the table, pushing the sleep from his eyes with his knuckles.

Curiously, and not a little surprised, Abner walked to the living room. Velma wasn't there.

Abner turned and walked back to the bedroom, thinking perhaps his spouse was napping. She wasn't there. A quick, three minute search of the rest of the house showed that Velma wasn't anywhere around the place.

"Maybe she's gone to a movie," Abner thought. "Or over to a neighbor's for gossip."

He shrugged, feeling a blessed sense of relief. Velma did most of her running around to movies and to neighbors and to bridge parties in the daytime. Only infrequently did she venture forth at night, and then never without an announcement of her plans to Abner.

Abner went back into the living room and sat down in the comfortable depths of the couch.

He reached into his pockets for one of the five cigarettes his slender budget permitted him to consume daily, found a match, and lighted up with a luxurious sensation of enjoying forbidden fruit. Ages ago Velma had established a set of house rules which included a taboo against smoking anywhere on the premises other than in the basement.

Then Abner picked up a wrinkled page of the evening newspaper containing the night's radio programs. Scanning it quickly, he saw that his favorite commentator, news analyst, and war correspondent was due on the air in less than two minutes.

It had been fully three months since the last occasion on which Abner had been permitted to hear that commentator. Three months ago when Velma had gone out to a bridge party, had been the last time he'd tuned in on his idol. Otherwise—when Velma was at home—the radio was tuned in only to the stations of her selection.

Eagerly, Abner snapped on the radio, flicked the dial around to the station he wanted, and set the volume to his liking. Then he sat back almost happily, taking a deep draught from his cigarette and lifting his feet up to a comfortable position on the couch.

For a minute Abner waited while a dance band finished its quarter hour broadcast from a remote suburban night club of wide reputation. Then the station identification came through, followed by the time and a spot commercial inquiring gravely into the state of the listener's liver.

Abner listened impatiently to this, and then at last was rewarded by a network announcer's voice breaking in.

"F.B.S. is now pleased to present George Holden Grentree, ace war correspondent, author, and military analyst, speaking to you over a shortwave broadcast arranged especially by this network—directly from London!"

There was a brief spluttering of static, then the announcer's voice, saying: "Come in, London!"

Abner Small was thrilling to the marrow in his spine. The very phrase was enough to send icy tingles of vicariously captured adventures shivering through his scalp.

He took a quick, deep, furious draught on his cigarette. In just an instant, he'd be transported across the roaring seas into the heart of Europe's most romantic wartime capitol.

"Come in, London," the announcer's voice repeated.

The static persisted, and in it Abner felt he could hear the very smashing of the waves against each other as the electric finger of his radio spanned the watery darkness that lay between two continents at war.

Again, the announcer's call sounded.

"Hello, London. Come in!"

Abner waited, tensed, for the first sound of the deep, magic voice of that ace war correspondent, George Holden Grentree. And then, quite unexpectedly, the static stopped and the sound of a piano playing something by Debussy came in.

Abner Small was startled at first, then seized by a sudden sick premonition of impending disappointment. The premonition was fulfilled an instant later by the fade-off of the piano, and the voice of the announcer coming back again.

"We are sorry to announce that, due to unforeseen difficulties, the program scheduled over shortwave from London at this time will not be broadcast."

The words rang sickeningly in Abner Small's ears. No broadcast! No chance to hear his idol's cool deep military accents vividly painting the thrilling canvas of the titanic world struggle. It couldn't be. There was probably only some small, minor delay in communication arrangements. Undoubtedly, the announcer would be back in a few minutes to state that the program was now ready to go ahead as scheduled.

But the piano interlude had picked up again, and there was no announcer's break in the program during the ensuing fifteen minutes other than to state each selection before it was played by the pianist.

Abner Small sat there numbly, unbelievingly, through the fifteen minute substitute program. And not until it had reached its conclusion was he ready to believe that he was actually going to be deprived of his favorite program.

"No," he muttered almost sobbingly. "It isn't fair. The first chance I get to hear George Holden Grentree in three full months—and then this happens!"

And at that instant a thoroughly unselfish concern came to Abner Small.

"Good heavens," he thought. "I wonder what prevented the broadcast?"

For a minute he deliberated. "Bombing?" he wondered aloud. "Could it be that the Boche are over London again?" And then, an even more dire thought struck him. "Has anything happened to George Holden Grentree, that ace of war correspondents?"

Abner Small began to wonder, first about Grentree, then about the bombing by the Boche, then about London and war correspondents and....

THE raid alarm was shrill in the night, and the beams from a

thousand anti-aircraft batteries were lancing the sky like

ghostly fingers of death seeking the destruction of the horror-

laden enemy hawks above.

The interceptors were already climbing up there, the first of them mixing it in death combat with the Jerries. Off in the suburbs the first dull thumps of the bombing was starting. Boche pilots already frightened into unloading away from vital destination.

Leaning back against the scant shelter of the building, ace War Correspondent Abner Small, glanced wryly at the luminous dials of his watch and smiled faintly.

"That calls off my broadcast to America tonight," he murmured. "However," he shrugged, letting the word trail off.

An Air Raid Warden hustled up to him.

"Better take shelter there, Johnny," said the Warden.

Correspondent Abner Small squared his shoulders under his trench coat and pushed back his famous battered war scribe's uniform cap. The Air Raid Warden suddenly grinned in recognition.

"Oh, sir," he said. "Didn't realize right off—" he began.

"S'all right." War Correspondent Abner Small assured him casually. "They're making a bit of mince meat out of Jerry tonight, what?"

There was a sudden, rocking explosion a few blocks off, cutting the Warden's reply off.

Correspondent Abner Small made a wry, half-humorous grimace.

"That one was close, what?"

The Warden nodded seriously, made a half salute, and hurried away. Correspondent Small wondered briefly about that last bomb, then, grim-lipped, decided to light out toward the place it had landed in spite of the fact that he had no helmet and hot flak was falling all around.

He'd made a block when he saw a girl lying there in a corner of the street. Unhesitatingly, Small turned swiftly and dashed to her side.

She was lying face downward, and when he turned her over he saw that she was young, twenty-two or thereabouts, and extremely beautiful. Her hair, long, soft and golden, framed a lovely oval face and delicately chiseled features.

She was unconscious.

In a swift motion, ace war correspondent Small lifted the girl in his arms. There was small shelter of a sort just across the street. It was the nearest and the most logical sort.

Moving quickly, Abner Small crossed the street with the girl in his arms. Gently, then, he placed her in the sheltered section he'd discovered. No chance to get her to a regular raid shelter or aid station until this bombing ended.

Briskly, holding her lovely hand in both of his, Correspondent Small chaffed the girl's wrist.

Her eyes opened after scarcely half a minute of this. Blue eyes, which regarded the war correspondent quizzically. And then understanding came into them, and she smiled wryly.

"Must have been knocked out by a flying fragment of rock, eh?" she asked.

Correspondent Small looked at the small discoloration on her forehead, smiled his relief, and nodded.

"You hit it on the head," he said, "or vice versa. That's what did it. Have a handkerchief?"

THE girl nodded, and handed Small a tiny white handkerchief.

He touched it gently to the bruised discoloration on her

forehead, making certain there was no other wound.

"How does it look?" the girl inquired. "It really doesn't hurt me a bit, you know."

"I think it's going to result in nothing more than a slight headache a little later," Small smiled.

The girl rose to her feet, standing close to Small in the shelter, smiling gratefully up at him.

"Thanks awfully," she said. "I might have gotten a bad one, lying there helpless, if you hadn't come along."

"It was an opportunity for which I should be grateful," Small said gallantly. The girl was even lovelier than he had first imagined.

"I must be on," she said suddenly, and for an instant their eyes met, while in that glance a world was born between them.

"But you can't," Small began.

She touched his hand. "We'll meet again, really we will," she assured him. "And when we do, I'll be glad."

And before Small had time to stop her, she was gone, dashing down the street in the direction from which he had come.

He didn't try to follow. He merely stood there a moment, looking at her and smiling softly to himself.

"But I don't know her name," he suddenly exclaimed.

He looked down at the small white handkerchief still in his hand. She had forgotten it. He touched it to his lips, catching the faintly taunting scent of exquisite perfume. And then he saw the tiny monogram in the corner.

"E.S." were the letters there.

"You were perfectly right, E.S.," Correspondent Small murmured quietly, "we will meet again, for I've something, at least, to start my search on tomorrow."

And then, lowering his head against the falling flak, ace war correspondent Abner Small, set out for that section a block away that had caught a bit of the bombing. Earnestly, he prayed that all the poor devils in the sector had been in shelter at the time it hit. Otherwise there'd be some grim ...

"ARE you always asleep with your eyes open, fathead?" a voice

demanded in shrill anger, breaking through Abner Small's wool-

gathering. "Eh?" Abner looked up startledly. Velma, wearing her

fur coat over a housedress, stood in front of him glaring

irately. She repeated her question in the same tone.

"I, ah, was thinking," Abner Small muttered.

"Thinking, eh?" Velma laughed harshly. "That's really rich. If you've ever had a thought in your head that wasn't woolly, I'd—"

"Good God!"

The startled exclamation came from the lips of Abner Small, and with it, he succeeded, for once, in cutting off his wife. Startled, Velma glared down at him.

Abner Small was holding a tiny white handkerchief in his hand—a woman's handkerchief, obviously!

Velma saw that her spouse was staring at it in open-mouthed astonishment.

"Where did that come from?" she demanded in sudden harsh suspicion. "And if this is some sort of an act, what's it all about?"

But Abner didn't answer. He continued to stare at the dainty handkerchief. He raised it slightly, and caught the taunting scent of exquisite perfume.

And it was then that he saw the initials, "E.S." in the corner!

Velma's voice came shrilly to him again.

"Where did you get that?" she demanded. "It's a woman's handkerchief and it isn't mine!"

It was then that little Mr. Small looked up at his wife and smiled in a most curious manner.

"No," he agreed quietly. "It isn't yours. You wouldn't have a handkerchief like this, ever. It belongs to someone else."

The dark clouds of suspicion in Velma's expression changed to sudden harsh scorn.

"Hah!" she rasped. "Another woman's handkerchief, is it? And if it is, where did you find it? It's a cinch no other woman is ever gonna relieve me of you. I wouldn't be that lucky!"

Abner Small stood up, the exceedingly curious smile still on his lips. He seemed scarcely to notice his wife. He fished absently into his pocket and found a cigarette. Then he lighted it, expelling the smoke thoughtfully at the ceiling.

"I'd like to tell you about all this," he said softly. "But you're far too stupid ever to understand. It's really quite incredible, most unbelievably wonderful."

The scorn slid from Velma's face, and dark suspicion and a faint tinge of fear replaced it. She stared wordlessly at her husband, warily.

"I don't understand it really, myself," Abner Small was saying, that strange smile still at the corners of his mouth. "It's all so utterly impossible, and paradoxically real." He looked down at the handkerchief in his hand again, shaking his head unbelievingly. "I'm sure of it, and that's all I can say."

Determinedly, Abner Small started toward the hallway.

Velma watched him brush past her wordlessly. Her expression was now distinctly that of distrust and even stronger fear.

Calmly, Abner Small was slipping into his coat.

"Where are you going?" Velma demanded harshly.

He continued to put on his coat, answering as he did so.

"I really don't know, and that's the truth. But it will be the sort of a place I've always wanted to be in."

"What are you talking about?"

Abner Small buttoned his coat, took his black little derby from the rack. He disregarded his rubbers and umbrella.

"I'm not certain that I know myself," he declared. "But I'm going to find out very shortly. Goodbye, Velma."

Abner Small had his hand on the doorknob. He turned briefly to smile at his wife. It was the same curious smile. A smile that was to haunt and irritate Velma to her grave.

"Goodbye," he repeated without malice.

ON that night, the night which was forever to be known to the

neighbors in his block as, "the night Abner Small disappeared,"

little Mr. Small did considerable walking.

It was, after all, a selection, a choice at which one could not be expected to arrive at lightly. Especially an Abner Small. And so it was that his long, leisurely, thoughtful stroll through the night went on for a number of hours before he at last reached his decision.

By what reasoning Mr. Small arrived at that decision, no one will ever know. Certainly, he could have selected a pattern which might well have been more magnificent than the one he chose. A pattern which, for a fact, could undoubtedly have permitted his dead to live eternally in history.

But such was not the mind of Mr. Abner Small. The course he at last selected proved, perhaps, that the glory of the thing had never really been the motivating factor in those pathetic daydreams. Proved, in fact, that the principle of the thing was all that had ever mattered to him.

And when at last he did make his decision, he knew without having to be told that it would be successful. He knew that the opening chain of a daydream about that role he chose to enact would be all that was necessary. He began that daydream ...

THE blaze of the stricken oil tanker must have been visible

for miles across the blackness of the night and the gently

swelling sea. But visible or not, there was no chance that rescue

would arrive in time to gain revenge on the gaunt black

silhouette of the Nazi submarine lying safely off from its

burning prey.

Perhaps the surfaced sub was waiting to make certain that the flames would be enough to send the blazing tanker to the bottom of the ocean. Or perhaps the machine gunners on its deck had begged their ruthless commander to allow them time to perforate the few poor devils who'd escaped in a half handful of lifeboats.

At any rate the sub was lingering, standing off from the blazing pyre that had once been an oil carrier, unconscious of the fact that it was impossible for any mortal on earth to still be alive on the smoke-blackened tanker's inferno-razed decks.

The tanker had had a gun for defense. But its crew was dead now, killed in the first explosion from the hold. Which was too bad, for that gun was loaded and trained rather accurately on the side of the surfaced Nazi sub.

Yet, incredibly, a scorched, blistered, oil-smeared creature crawled stubbornly toward the side of the tanker's single gun! He was a little man, and his name was Abner Small. But no one was ever going to know that. Yes, he was a tattered, blackened, spectre of a man. A half-burned piece of humanity who dragged himself erect behind the sights of that remaining gun.

He laughed like hell through blistered lips when he saw how nicely those sights were trained. Laughed like hell to think the agonizing and perhaps impossible task of loading that gun was spared him by the fact that the dead crew had already inserted a shell and closed the breech.

There was plenty of time to fire that gun, and hero Abner Small utilized it to the last second. And when the shell banged forth it made a hit such as no submarine in the world could survive.

Nothing was left of the shark-like hull of the black Nazi sub but oil and twisted plate fragments. And little else was left of the oil tanker in the deafening explosion that split it asunder just a minute after the sub was hit. Nothing was left intact on either craft.

Not even a recognizable scrap of little Mr. Abner Small. For his had been a daydream from which even such a thunderous explosion could not jar him. And it is more than reasonably certain that little Mr. Small would have cursed roundly any soul who'd tried to rouse him from his final bit of woolgathering.