RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

Fantastic Adventures, January 1943,

with "Saunders' Strange Second Sight"

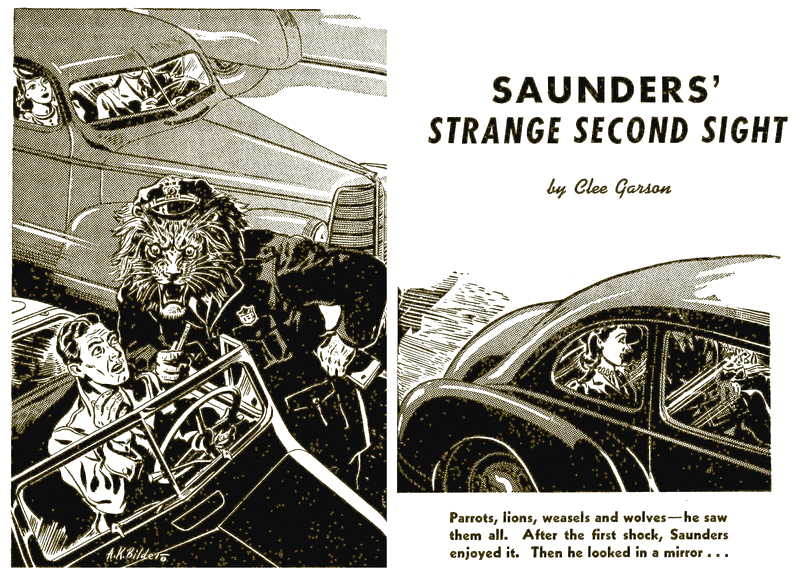

"Whatsamatter?" the cop said. "See a ghost or somethin'?"

Parrots, lions, weasels and wolves—he saw them all.

After the

first shock, Saunders enjoyed it. Then he looked into the mirror.

THERE are pretty close to four million people in Chicago, and lots more—I am told by people who seem to know—in the United States proper.

That's why the whole thing seemed particularly strange coming as it did. Out of umpty million people in the United States and close to the previously mentioned four million inhabiting Chicago, it seems utterly inconceivable that Richard Saunders was the person Fate—or whatever occult force it was—chose to have it happen to.

Richard Saunders just isn't the sort you'd expect to find visited by psychic phenomena of any kind. He's not dark; he's blond. He's not sinister; he's stupid. He isn't a seventh son; he's an only child. And he's not descended from gypsies or anything of the sort, his father being one of the wealthiest, most solid manufacturers in all Chicago. He just doesn't ring the bell on any of the standard props you'd expect to find in the background of one coming into possession of powers strictly occult in nature.

Maybe the mysterious other world forces which gave him the weirdly psychic power were tired that day and got their addresses mixed. Or maybe they just did it as a lark. At any rate, the power wasn't left with young Richard Saunders for long. It was snatched away as swiftly and as inexplicably as it was granted.

I have a hunch I'm the only one, aside from Saunders himself, who knows about it. He told me it all perhaps two months after it happened. Told it to me in utter, straight faced solemnity, after first making me promise that I wouldn't think him crazy. When he'd finished he begged for some sort of an explanation that might set his mind at ease. I wasn't able to think of any then, and I still can't.

It just happened, that's all....

IT was a fine, balmy morning in May, and young Saunders, his

soft, thin, elegantly tended young hide attired in a blue pin-striped suit, two-toned shirt and chalk blue Fedora, was piloting

his long, blue streamlined roadster through the stream of

Michigan Boulevard traffic on his way to work.

He had breakfasted leisurely in the sprawling twenty-two room Lake Forest shack that he called home, mentally thanking fortune for the fact that his father was out of town at some convention, and that, as a consequence, he could take his time arriving for work at the old boy's office.

It was almost ten o'clock, therefore, when young Saunders turned his roadster into the underpass off Wacker Drive and sought for someplace where he could illegally park his car.

After several minutes of snail-paced driving, Saunders spied an area which was unoccupied, by virtue of a very large No Parking sign painted prominently upon its surface.

Triumphantly, Saunders wheeled his machine into this heaven-sent parking place, completely obscuring the sign by virtue of the fact that his roadster now covered it completely.

Chuckling at what struck him as being a remarkably shrewd maneuver, Saunders leaned forward, switched off the ignition, and put his keys in his pocket.

He was just starting to climb from the car, when the voice, hoarse and definitely angry, arrested him.

"And whatta yez think ye're doing, eh?"

Young Saunders froze. He didn't have to look up to identify that voice. Even to his limited intelligence it was a voice and phrase which could come only from the lips of—a policeman!

In that brief instant, while struggling to force a smile to his lips before turning to confront the law, Richard Saunders went through hell. A hell concerned primarily with his father's reactions if said father learned, through a police summons, that his son Richard was driving to work against strict paternal orders. Old man Saunders, being strictly of the no-pampering-come-up-the-hard-way school, often stated that the suburban morning train, if good enough for him, should most certainly be good enough for young Richard.

"I don't ever want to catch you slopping down to work in my office in that four-wheeled palace of yours!" the elder Saunders had often thundered at his son.

Sickly, now, young Saunders recalled each reverberating roll of that phrase. And the fact that his father was out of town on a convention—which was the reason for his having dared to violate the edict—was scant consolation. If he got a ticket now, the old boy would discover it all through the summons. For the machine, though technically Richard's, was registered in his father's name.

Young Saunders realized, too, that any investigation into the parking charge would reveal, also, the damning fact of his having arrived so late for work.

"You'll start at nine and quit at five like the rest of 'em!" was another one of the senior Saunders' favorite admonishments. And here it was almost ten!

Richard Saunders finally managed a sickly, feeble smile, and summoned enough courage to turn to face the policeman who owned that mercilessly accusing voice.

And then it happened!

YOUNG Saunders turned, the pseudo-smile valiantly working the

corners of his weak young mouth into something resembling a very

silly leer. He turned—and confronted the huge, shaggy,

angry head of a lion!

For a split second, while his own face was still less than two feet from the face of the lion, Richard Saunders goggled in gaping terror.

Then a shrill scream started in his throat. A shrill scream which emerged only as a high-pitched, bubbling wheeze.

He wanted to run. He wanted, with a terrifying desperation, to get the hell away from there as quickly as his long skinny legs could carry him.

But he couldn't move. Not an inch. And, even worse, his knees, which were so helplessly incapable of motion, seemed quite on the verge of completely refusing to support him.

"Well?" snarled the lion. "Whatcha got tuh say fer yerself, wise guy?"

And then, even through his terror, Saunders was able to see that this lion was an incredibly strange one. For it wasn't all lion. It was, in fact, just a lion's head atop the body of a policeman!

Saunders' lips moved automatically in reply.

"Wuhwuhwuhwuhwuhwuh, buhbuh-buhbuh, zuzuzuzu!" he gurgled.

"What's eatin' yez?" demanded the lion-policeman truculently. "Get this buggy outta here pronto!"

Saunders' reply was still impossibly incoherent, consisting again of a series of sounds. He slumped weakly down behind the wheel of the car, as if compelled by a hypnotizing force quite beyond him. With hands that shook wildly, he managed, somehow, to put the key in the ignition; managed to get the motor started.

He was in such a frenzy of fear that he was scarcely conscious of doing any of this. The policeman with the head of a lion—or the lion with the body of a policeman, if you prefer—stood back a pace, hands on hips, glaring balefully as the young man backed the machine out of the space.

"Git along to a parkin' lot wit yez!" bellowed the lion headed policeman savagely, "And don't let me catch yez sneakin' inta here agin!"

Saunders got.

He got just as quickly as the thunderously powerful motor of his streamlined roadster would carry him. Eyes glazed in wild terror, he rocketed blindly through the lower level, missing pillars and opposite bound vehicles merely through the grace of God.

And as some of the terror ebbed a trifle, some reason returned to him. Quite suddenly he was aware for the first time that he was behind the wheel of his roadster and travelling through a dangerous web of sub-street roads at breakneck speed.

Even Richard Saunders had brains enough to realize that another mile or so of this sort of driving, or of any driving, would be suicidal in his present state of terror.

HE jammed on the brakes just as a parking lot appeared to his

right. Saunders had always avoided parking lots in this vicinity

because innumerable business friends of his father's kept their

machines in them. But he wasn't thinking of his father now. He

wasn't thinking of anything save the terrifying phenomenon of the

lion-copper and the fact that he badly needed a drink.

Saunders tooted the horn, and he saw a parking-jockey, a small wiry youngster clad in puttees and a greasy uniform cap, pick up a ticket from the cashier's cash and trot out toward the roadster.

"Here's y'ticket, mister," the parking-jockey called. "I'll bring it infer-yuh!"

Gratefully, young Saunders reached out for the ticket, sliding out from behind the wheel as he did so. And it was only then, with the ticket in his hand, and the parking-jockey stepping past him to slide in behind the wheel, that Saunders saw the fellow's face.

The parking-jockey, beneath his greasy uniform cap, displayed not a human head, but the head of a beaver!

Richard Saunders emitted a shout of pure terror.

The parking-jockey with the beaver head turned to look at young Saunders astonishedly.

"What's wrong, Mister?" he asked. "N-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-nothing!" Saunders bleated. He turned then, clutching the ticket, and dashed madly away. His legs were able to move this time, and their long, wild strides ate up the ground beneath him. He found himself at the steps which led from the lower level up to the boulevard. He took the steps three at a time, emerging on the boulevard in weak and breathlessly terror.

He leaned against the railing of the Michigan Boulevard Bridge, pantingly seeking to refurbish his strength.

And then he looked around. Looked around to see the usual stream of boulevard pedestrians moving hurriedly along past him. They were all quite thoroughly human. None of them had animal heads.

Saunders told me later that he wanted to run up to any and all of these completely normal fellow human beings and shake their hands or kiss them on the cheeks. He was so grateful, tears welled in his vaguely gray eyes.

It took him fully another five minutes to gain the strength to head for the nearest bar. And when, three minutes after this, he crossed its threshold, he had already started rationalizing—to the best of his limited ability—over the incredibly terrifying phenomenon he'd been subjected to.

He was rationalizing so furiously, as a matter of fact, that when he sat down at a stool before the bar, he didn't get a glimpse of the barkeep until that gentleman approached and asked:

"What'll it be, sir?"

"Rye, double portion," Saunders answered automatically. He looked up vaguely at the barkeep. Looked up and saw a weasel's head atop the scrawny, white aproned body of a bartender!

The bartender-weasel combination grinned, said, "Sure thing," and turned away to mix the drink.

RICHARD SAUNDERS clung to the bar until the knuckles of his

pale, well tended hands stood out like white marbles. He opened

and closed his mouth. He shut his eyes, then opened them. He

shook his head drunkenly. But for some reason or

another—possibly because this sort of thing was becoming

monotonous, or possibly because his strictly limited imagination

had spent itself—Saunders' only emotion was one of concern

for his own sanity. This time, he wasn't actually afraid. He was

merely stunned.

The bartender returned, planking the drink before him, and grinning with that weasel's head.

Automatically, Saunders found change for the drink, still staring pop-eyed at the unhappy blend of beast and barkeep.

"Something wrong?" asked the weasel head, expression changing.

Saunders shook his head.

"No," he muttered. "No. Nothing at all." He managed to tear his eyes away from the barkeep-weasel until that person had turned away to ring up the sale.

While he finished his drink, Saunders covertly studied the combination weasel-barkeep over the rim of his glass. And it was just about the time he'd finished the drink, that another customer entered the place.

This new customer was a portly, middle-aged chap—without any identifying peculiarities such as an animal's head. Thoroughly normal. He sat down, the weasel-bartender moved over to ask what he'd have, and the gentleman declared in favor of scotch.

Saunders watched the scene in fascination. The normal, middle-aged gent displayed no reactions such as one might expect from a person whose order has just been taken by a man with the head of a weasel.

Draining the last of his drink, Saunders debated for an instant on the advisability of approaching the gentleman to ask him if he didn't think it strange that the bartender had the head of a weasel. Then he decided—for obvious reasons—that such questioning would be inadvisable inasmuch as the portly gentleman didn't seem to know that he was being served by an unnatural phenomenon.

Saunders took a deep breath, rose from his stool, and left the bar.

Out on the boulevard again, he once more became part of a stream of utterly normal humanity hustling north and south about its business. But by now the double rye was setting up a warm fortification against any recurrences of hysteria or fear which his resumed rationalizations might bring on.

Saunders, with his one-cylinder mind, was doing a terrific job of selling himself an explanation of all this madness, even though he wasn't quite sure himself what the explanation was.

It never occurred to him, after his first brief wavering on the subject, to doubt his sanity. His ego, quite naturally, wouldn't tolerate that sort of reasoning for long. So beginning on the basis that he was sane and in no state of mental disorder whatsoever, he began to run the gamut of the scant possibilities left in his mind.

Sun spots got quite a kicking around. He'd read an article in a newspaper almost a week previously about sun spots, and remembered vaguely that they were responsible for all sorts of things. He tried to recall if there'd been anything in the article about such perplexing phenomena as human beings with the heads of animals, and finally had to admit despairingly that he couldn't recall any such material in the piece. So he regretfully discarded sun spots.

Nimbly, then, he ticked off in his mind the three or four most recent plays and the half dozen most recent movies he'd viewed. None of these gave him anything to sink his teeth into, so he had to pass them on also.

He thought for a while of pinning an explanation of some sort on his eyesight, but realized after a futile five minutes of this, that he couldn't work anything plausible out of that theory.

IT is quite possible that he never would have hit on the

theory that he did if he hadn't passed the huge boulevard book

store windows at that moment. Passed, only to be abruptly halted

by the phrase from a display poster in one of the windows which

had caught his eye.

"The Animal Kingdom," the poster proclaimed, "Is Strikingly Similar To Our Own!"

And then the poster went on to announce that this fact would be instantly evident to anyone who purchased a copy of "The Man and The Beast" for two dollars and a half. This book, written by that eminent zoologist, Professor P. Prawl, the poster went on to explain, drew striking socially satirical resemblances between animals and human beings. It quoted, briefly, a paragraph from the book concerning certain striking resemblances between one A. Hitler and almost any rodent.

Saunders stood before the window goggle-eyed, his heart hammering in sudden elated excitement. Here, as if handed to him on a platter by the proverbial hand of fate, was an explanation for it all!

The angry, bellowing lion head on the policeman was—to steal a phrase from the poster—nothing more than a strikingly realistic transformation of said copper into the animal kingdom.

The hard-working, always-running parking-jockey, too, was another symbolically expressed transformation.

What better could he be than a beaver?

The weasel-barkeep, pinch faced and sly, also fitted nicely into this theory.

And it came to young Saunders, then, that he alone among his fellow men had, through some tremendous power of insight, the ability to see other human beings as they actually were in relation to the animal kingdom from which they were not so many centuries removed!

That was it. There was no doubt of it. He was able to see people as they would be if they reverted to origin tomorrow. Not all people, apparently. Perhaps only the people with whom he came into immediate personal contact.

Typically enough, this sudden encounter with an even remotely plausible theory was all Richard Saunders needed. His anxiety and emotional rollercoasting vanished completely to be replaced with the elated enthusiasm of a none-too-bright child with a new toy.

It never occurred to him then that he still hadn't hit upon an explanation for it all. The theory was all that he needed. And now that he had it well in hand, his eagerness to use his strange new insight became an ungovernable itch.

He looked at his watch. It was just ten-thirty. For the first time in his life he felt an urgent desire to hustle to his father's office. There, among numerous people with whom he'd been thrown into almost daily contact for over a year, he'd have a field day with this exciting new perspective....

THE elevator operator in the building where his father's

office was located provided Saunders with his first brief, animal

analogy.

Saunders stepped into the cage, scarcely conscious of the operator's presence, engrossed in contemplation of the visual picnic he was due to have.

The operator's, "Good morning, Mr. Saunders," brought him out of the fog. "The weather's fine, no rain, eh?" the operator added.

Saunders glanced at the operator, and found himself staring at a parrot's head atop a uniformed human figure.

"Yes, the weather's swell," Saunders replied automatically.

"Nice day, swell weather, yes sir," the operator-parrot combination chanted.

"Sure is," Saunders declared.

"Sure is," echoed the weird combination.

Saunders got off at twelve. He stepped into the reception room of Saunders & Company an instant later. He heard the voice of Doris, the neat little number who operated the switchboard, chanting from her cubicle.

"No sir. He's not in. Saunders and Company. Mr. Welk? Just one moment. No sir. Saunders and Company. Just one moment."

Grinning, Saunders sauntered over to the board.

"Good morning, Doris," he called out cheerfully.

A trim pair of silken underpinnings flashed, an arm appeared around the board. Doris looked out.

"Good morning, Mr. Saunders!" a honeyed voice declared.

In spite of the fact that he expected nothing human, Saunders gasped. Instead of the pertly alluring features of Doris, he saw what was undoubtedly the head of but one animal—a minx!

Saunders flushed a deep crimson. He groped for the door leading to the inner offices.

"Good God, I mean, good morning!" he choked.

Saunders opened the door and stepped into the general office. The ringing of telephones and the clacking of typewriters suddenly came bedlam-like to his ears.

He took a swift glance around the several dozen employees at their desks throughout the general bullpen. They all looked normal enough, busy as usual. He started through the bullpen on the way to his own small office.

"Good morning, Mr. Saunders."

Young Saunders turned at the sound of the voice. Turned to see the meek, cardboard sleeved little figure of Cossett, the old bookkeeper, who'd turned slightly on his high stool to make his small voice heard.

Cossett presented the head of an incredibly timid gray mouse. A gray mouse with a pencil behind its ear.

"Good morning, Cossett," Saunders grinned. He continued on. Mouse-headed Cossett bent back over his work again.

A figure stepped up to Saunders. A short, stocky, barrel chested figure in shirt-sleeves, completely blocking his way.

"Look, Mr. Saunders," the voice belonged to Harlan, shipping room boss, "I've had those invoices on your desk an hour. The stuff can't get through until you sign 'em. Speed it up, will you?"

Harlan's head was perfectly in order—the dogged, angry, joweled features of a bulldog. A bulldog looking very much on the verge of biting.

"Sure, sure," Saunders said swiftly, stepping around the shipping boss. "Have 'em right in." He mopped his brow as Harlan moved on. Just a little unnerved, Saunders almost bumped into the extended nether quarters of the sleek, well dressed Mr. Owens, office manager. Owens had been bending intently over the shoulder of a small, dark-haired girl who was apparently the new steno Saunders had heard they were hiring.

"Sorry, Owens," Saunders said, starting to step around.

Owens straightened up, turned startledly, saw Saunders and smiled.

"Good morning, Mr. Saunders. Just breaking in the new girl," he grinned.

On the dapper body of Owens there was a head that was unquestionably that of a wolf.

SAUNDERS' jaw went slightly slack.

He nodded wordlessly, hurrying on past his office manager. He almost reached the door of his own office, but didn't quite succeed. A friendly slap on the back and a big hand on his arm arrested him.

"I heard a good one today, Dick!" a voice chortled. "It'll knock your teeth out."

Benson, the account salesman, one of the few men in the place farsighted enough to play up to young Saunders. Saunders beamed, turning to face the minor executive.

Atop Benson's stout, Falstaffian body, there was the head of a hyena. Saunders stared at it in fascination, scarcely hearing the joke Benson boomed forth. The joke ended, Benson nudged him in the ribs. Hyena-like laughter broke loose from the quite hyena-like head. Benson walked off, fat body shaking with mirth.

Saunders managed to reach his office. Inside, he sat down uneasily behind his desk, running his hand across the surface of the desk nervously.

He was beginning to wonder whether or not he cared for this sort of thing. It was, he sought for a phrase, too damned starkly revealing in cases.

He hesitated when he reached for the buzzer on his desk. He didn't know whether or not he'd care to see Margaret, the spinster his father assigned to him as a secretary, under the additionally trying circumstances of her popping in with the head of a loon, or a penguin. He didn't know why penguin occurred to him. It just sort of seemed to fit. He took his hand away from the temptation of the buzzer.

Nervously, he rose. He walked to the wash cabinet, pulling his comb absentmindedly from his pocket.

In front of the cabinet mirror, Saunders raised the comb to his blond hair. An unconscious routine. One done countlessly in his own office. His eyes met his mirrored reflection.

He let out a swift, sharp, indignant yelp, leaping back in sudden astonishment, unwittingly entangling his feet in the telephone cord by his desk. He couldn't stop himself from toppling over backwards, anymore than he could have prevented his head hitting the leg of his desk....

THEY brought Saunders around in less than five minutes. Which

was pretty good, considering the fact that he'd been out quite

completely. He had nothing worse than a lump on his head and an

ache in his skull. And strangely enough, the power was gone just

as suddenly as it had been given him. Everyone was normally

reflected in his vision. No more animal kingdom. No more psychic

insight.

Saunders was just as glad.

But he's still troubled about an explanation. He's beginning now to talk himself into believing it was all some tragic hallucination. But that explanation won't hold water with me. From all he's told me, everything fitted too well for it to be a product of his none too nimble imagination. Especially his last insight to the animal kingdom.

That last insight he couldn't have made up. For the startling phenomenon which stared back at him from his mirror, the animal head reposing quite serenely on his own shoulders, was the foolish, vacant, elongated head of a jackass!